Since the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, and the tsunami and meltdowns that followed in its wake, there have been many moving stories about how the disaster impacted, and continues to impact, especially Japanese living in Fukushima and the Sanriku Coast. Meanwhile, in Tokyo, life returned to normal for the vast majority of the population within a few years. March 2011 and its aftermath seem like distant memories, something that happened a long time ago in a region far, far away.

But did it really? In what ways are the aftershocks and fallout of 3.11 palpable in the Tokyo area today? That is the question the exhibition “Kanto Loam Stories” aimed to address. Organized by me and my students from the University of Tokyo in the winter of 2018-19 and displayed at Not So Bad, an art space in Myogadani in Tokyo, between January 14-25, 2019, “Kanto Loam Stories” comprised six photo-essays looking at the way people, businesses, universities, and government agencies in and around Tokyo continue to be influenced by the aftereffects of the earthquake, tsunami, and meltdowns, and by the private and public initiatives aimed at rehabilitating the disaster zones and the greater Tohoku region. While offering research-based snapshots of these developments, the show also provided an opportunity to reflect on how post-disaster responses look to people (specifically young Japanese and international students in Tokyo) not impacted by them directly, either because they moved to Japan only recently or because they never chose to get personally involved.

Over the past year, I taught a master’s level graduate course titled “Short-Form Art Writing” in the Cultural Resources Department at the University of Tokyo. During the Fall/Winter semester, the theme of the class was “Art and Disaster,” focusing on March 2011 and its aftermath. As few of the students were art-related majors, and even fewer were Japanese nationals, the course became as much a tutorial about the 2011 disaster and how artists have responded to it, as it was about the practice of crafting tight, informed, and critical responses to artwork and exhibitions.

|

|

|

After surveying related art through the lens of reviews in magazines like Artforum International, Art in America, and Bijutsu Techō, and art critic Kurabayashi Yasushi’s overview in Shinsai to aato: Ano toki, geijutsu ni naniga dekitanoka (Art and the Disaster: What Did Art Accomplish? 2013), we dug into a handful of case studies. Two young, rising artists were kind enough to visit our class and talk about their work. Katō Tsubasa, who first went to Iwaki in southern Fukushima in April 2011 to help with recovery efforts, spoke about his collaborative performances with people from around the world, and specifically about his iconic “The Lighthouses: 11.3 PROJECT” (November 2011), in which some 500 people from coastal Iwaki were brought together to raise with ropes a large wooden model of the destroyed Shioyazaki Lighthouse. Seo Natsumi spoke about her multi-faceted engagement with loss and memory following the traumatic annihilation and equally dramatic reconstruction of Rikuzentakata in Iwate, where she lived full-time between 2012 and 2017, as well as about her activities as a writer, artist, and curator since settling in Sendai. Unfortunately, bound to Tokyo, we could only consider the post-tsunami display at Rias Ark Museum in Kesennuma and art group Chim↑Pom’s “Don’t Follow the Wind” project in Fukushima exclusion zone second-hand through images and text. But we did have the opportunity to visit the large “Catastrophe and the Power of Art” exhibition at the Mori Art Museum (October 2018-January 2019), which attempted to reframe the 3.11 disasters in relationship to a sprawling range of artistic response to wars, massacres, industrial accidents, and other natural and man-made catastrophes. To gain historical perspective, we also visited the Great Kanto Earthquake Memorial Museum and Itō Chūta’s Memorial Hall at Yokoami-chō Park near Ryōgoku, dedicated to those who died in the 1923 earthquake and the Tokyo Air Raids of 1945.

Approximately every other week, students were asked to respond to class sessions in the form of Instagram posts (2200 characters max), where they reflected on life and death, disaster and reconstruction, as well as the politics and social value of art. While not all of their Instagram accounts are public, most of the course’s output, as well as my assignment guidelines, can be found under the hashtag #tantanpen, which literally means “short-short-form,” but is a portmanteau of the Japanese for “short-form writing” (tanpen) and the spicy Sichuanese noodles known in Japan as tantanmen.

After three months spent appreciating and assessing other peoples’ curatorial and artistic endeavours, I thought it was only fair that they be asked to create something themselves for their final project. The result is the photo-essays in the present exhibition. Moreover, as most of what we looked at in class was made prior to 2016 (the fifth anniversary of the disaster), I thought it imperative that we learn about what is happening now. Inspired by curator Yamauchi Hiroyasu’s unique narrative presentation at the Rias Ark Museum, which mixes factual description with imagined oral recollections, and the storytelling projects carried out by Seo Natsumi, NOOK, and the Sendai Mediatheque, I asked my students to create short photo-essays (three photographs and three Instagam-length texts) addressing the simple but broad question: How can one read the legacy of 2011 in Tokyo today? Having them focus on the Tokyo region was of course motivated by convenience, since travelling to Tohoku requires time and money. But I also wanted to challenge the usual impulse of decrying Tokyo-centrism and heading north to see how the disaster zones are managing.

To my surprise, they unearthed relevant stories fairly quickly. This is instructive in itself. What their projects demonstrate, at a basic level, is that, whether one is looking at sporting events, new energy initiatives, what to eat, where to travel, the city skyline, or simply how people navigate their neighborhood or think about their furniture, the aftereffects of 2011 are part of the very fabric of work, leisure, and daily life in present-day Tokyo. Their projects also show that 2011 is hardly a cipher of memory alone. It is a living and evolving event.

Below you will find the texts and photos of their projects. I am sure you will learn about things you didn’t know about, or think about things you do know about from a different angle. I certainly did and do. Keep in mind that the project was initiated and completed within one month’s time, and that none of the participants, all of whom were master’s students, had previously researched 3.11, though each of them effectively brought their specializations (whether that be engineering, architecture, communications, or cultural studies) to bear upon the issue. The point of the project, at its most basic level, was simply to force students to get their hands dirty, because I believe that it is only once one has a stake in an issue, even if that stake is no greater than exposing your opinions to a public audience in the form of an exhibition (and now a post-exhibition online publication), that the learning process really begins in a responsible and sustained manner.

As for the title of the show, “Kanto Loam Stories,” this came from Yumi Song, artist and writer, and also Director of Not So Bad, who spearheaded the design and installation of the exhibition. “Though Kanto Loam may not be very well known outside of Japan, every schoolchild in the country learns about it at an early age,” she explains. “It refers to the layer of volcanic ash that has accumulated across the Kanto Plain due to the eruptions of Mount Fuji and other volcanoes. We who live in this region have effectively built our lives upon a substrate created by natural catastrophic disruptions of the deep past. It is present in our memories like the historical events and happenings that inform living folktales. Kanto Loam Stories investigates how the geographically and temporally (seemingly) distant events of 2011 are selectively becoming part of this seismic folklore.”

Both Song’s statement and mine above were initially written as introductory wall text for the exhibition, and have been edited and expanded here for the new format and a wider audience. Photographs from the exhibition and the opening night, when students explained their projects, can be found accompanying this essay and under #tantanpen@Instagram. I would like to thank Yumi Song for hosting and helping shape the show, Matsuo Ujin for the nice photographs of the original installation, and of course my students Max Berthet, Joelle Chaftari, Fujimoto Takako, Hidaka Mari, Noemie Lobry, and Vanessa Yue Yang for their hard and insightful work.

|

My Friend Chizuko

Joelle Chaftari

|

1.

I met Chizuko, a Japanese woman in her seventies, upon my arrival in Japan in April 2017. We were introduced by a common Lebanese friend, someone who had attended the American University of Beirut with her in 1967, when her father was the Ambassador of Japan in Lebanon. Since then, we have been close friends. We meet every now and then at a restaurant that serves seemingly Lebanese cuisine.

When we were first told about our final project, I felt I wanted to make it through an individual lens rather than on the scale of the city. Being in a “secretive” country where many things are left unsaid, I thought it would be a unique chance to explore traces of the March 2011 triple disaster through the personal stories of my friend Chizuko. This is how we came to meet at a café in Mitaka in western Tokyo, where she lives. This chic woman arrived dressed in a long coat and white cashmere hat, with her bōsai (survival kit bag) hung on her shoulder.

As soon as we sat with our coffees, she put on her glasses and took a handful of pamphlets out of her handbag. Some were distributed by Mitaka city, while others were from the company where her husband used to be employed. She insisted that we go through each of the brochures, and the precautionary measures to take in the event of an earthquake or flooding. When she pointed at the illustration of a person hiding under a desk, she recalled how she hid under hers during the 2011 earthquake. She tried to act out the scene using the brochures, holding an A4-sized sheet of paper above her head while waving under the paper with her other hand.

“It was moving, like this,” she said, explaining how her garden had shaken.

Usually during our encounters, Chizuko offers me little things from her house to get rid of the burden of the ‘superflu’ of unnecessary things that have been sitting around for too long. “Please, take these pamphlets home,” she insisted, “I am sure they will be useful.” A weight off her mind, she put her bōsai on the table and emptied its contents: an empty bottle of water which she fills every now and then, a thick plastic bag for water refill, a rope and a candle. As she unloaded the bag, her face showed worry. She took out a pair of cotton gloves and quickly put them on. She explained to me that she always uses them for gardening. “They are very convenient and useful.” Enjoying their touch, she added, “They are also very cheap. You can buy them from any konbini.”

Chizuko admitted her bōsai lacked a lot of items. She made a hand-written list for me: biscuits, chocolate, cash, bandages, helmets, torch, clothes, knife, bank book, essential medicines, cotton gloves (since she uses them for gardening), and a radio with batteries to listen for official announcements. She says she is old and doesn’t feel the need to keep her bag ready. It is incomplete partly because of laziness and partly because Mitaka is said to be safe due to its hard soil. “Danger depends on one’s geological situation,” was her philosophy.

|

2.

“Chizuko, can you tell me more about your own personal experience of the 3.11 disaster?”

“Oh, my experience is boring,” as if it needed to be fun. “I was under my desk. I can take you to my house to show you.”

We leave the café for her house. On our way, we stop at a shop so she can show me “navy biscuits.” She explains to me how kanpan (hardtack) were also used during the war. As we walk through her neighborhood, she recalled stories from family and friends about how stone fences around houses collapsed in places in Tokyo like Suginami-ku. Soon after the earthquake, she had a memorial mass for her mother-in-law at the family grave. She noticed that five out of nine big stone lanterns belonging to her family had toppled over, all in different directions. Stone lantern repairers became very busy fixing lanterns around Japan, including one at her brother’s house. She hadn’t imagined that something so serious could happen. Though after typhoons, she had seen uprooted trees.

On her daily route to the train station, there is an abandoned house. As we pass by, she explains to me how the big retaining wall around the house had collapsed. Since the owner lives somewhere else, her husband alerted Mitaka city, but so far they haven’t done much besides add a rickety steel structure, which is clearly insufficient to support the wall’s weight. Wary, now she walks on the other side of the road on her way to the station.

When we reached her house, Chizuko went in first, removed her shoes in a hurry, and went straight into her dining room. “Please ignore the mess. Papers are everywhere. It’s my husband. I always ask him to clean them up but he won’t. Please ignore the mess.” She ran to the cupboard behind her desk, saying that it stayed closed during the quake, unlike her sister’s, which opened so that the plates and glass fell out and broke. She entered her kitchen. “This is our gas. The gas company changed the system so that it turns off automatically when movement is detected.”

|

3.

At the time of the earthquake, she hid under a big table. “I was under here and the garden was shaking, like this. The garden was moving and I held the table’s big elephant foot, like this.”

Fortunately, the lantern in the garden, built of piled stones, did not fall. Things were “under control.” “It’s 70,000 yen to repair one lantern!”

“What about Taro, Chizuko?”

“Cats don’t panic.”

With no further reaction, I feel that she is somehow hesitant to talk about the topic. She’d rather tell me about a Brazilian woman she saw on TV who had to leave her dog behind when she was evacuated by helicopter. Animals, she explained, are not allowed in evacuation centers such as schools.

“One family in Fukushima left water and a big open bag of food for their four cats. When they were finally allowed to visit their house to retrieve their belongings, one cat had died, three survived.” Yet they had to leave them behind once again.

As she looks thoughtfully out at her garden, I reflect on the impact of the March 2011 earthquake. A disaster can be cataclysmic on a big scale, and very different on an individual scale. The impact not only depends on geography or a person’s age. It is also related to personal experiences, and the very specific conditions of one’s house, personal objects and furniture, personal psychology, conflicts, experience, or trauma. While 3.11 was certainly a catastrophe with large-scale loss and damages, on a much smaller scale, preparedness within one’s personal space may be limited to minor gestures, like making sure you have navy biscuits on hand, or walking on the other side of the street on your way to the station.

After spending a moment standing in front of her garden, Chizuko sat down and suddenly said to me, hesitantly, “I think I was mistaken. It was not my garden swaying, but the house itself.”

Sport-Based Recovery in Tohoku, with Tokyo Behind the Scenes

Max Berthet

|

1. Local and Capital

“Hope lights our way.” With the 2020 Olympics around the corner, Japan is renewing its efforts to be at one with areas hit hardest by the 2011 disaster. Not only for good global PR, but as an opportunity to give a push to recovery in Tohoku, articulated around Olympic solidarity. Amongst the hope-lighting “ways” referred to in the slogan of the Tokyo Olympic torch relay above is a series of running events taking place in the build-up to 2020.

The Tohoku Food Marathon (TFM) intrigued me most. Takekawa Takashi, founder of the annual event, encourages participants “to enjoy the race, but also all the food and sake” served by volunteers around the track. Dishes include hatto-jiru soup from Minami Sanriku, a coastal town almost completely levelled by the tsunami. A word of caution, however, should you overindulge a mid-race pit stop: “No intoxicated persons are allowed to run the race.”

This isn’t simply a running event. Expect organised excursions to breweries and ongoing reconstruction projects along the Miyagi coast. The two-day festivities aim to raise awareness of the situation in post-3.11 Tohoku and revitalise local tourism, through interaction between “runners, children, volunteers, tourists and residents.” The host city, Tome, is located in one of the areas hardest hit by the tsunami, and acted as a base for coastal disaster response teams in 2011. It seems fitting that the city is now playing a central role in cultural and economic recovery. Last year, over 7000 runners from all over Japan converged on Tome for the TFM. The event drew around 50,000 spectators, an impressive feat for a town of only 81,000.

Organisers of the fun-run are locally-based, though financing relies on behind-the-scenes support from Tokyo. This is welcomed by local authorities, who can conserve scarce municipal resources for ongoing reconstruction projects. In the photo, dried peaches produced in Fukushima, a variety of which is served in the race, are shown against the headquarters of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Minato-ku, one of the event’s main sponsors. Local authenticity and central financial backing have to strike an appropriate balance.

According to organisers, the marathon has already brought ¥280 million to the local economy. Consumption of Tohoku produce, such as pickled peaches, is also reported to be on the rise in Tokyo. Yet Miyagi, Fukushima, and Iwate prefectures still receive fewer than 1% of foreign visitors to Japan. Takekawa urges patience: “Maybe 20 years from now, Hong Kong runners will be able to buy Tohoku sake in Hong Kong.” Entries for 2019 are open until February.

|

2. Voices from Tokyo and Tohoku

In my view, the Tohoku Food Marathon (TFM) meets its aim of promoting recovery in Tohoku. But what do others think? And what are the most important ingredients for an effective reconstruction-support event? I was curious to find answers from a varied mix of people. I interviewed two locals and two students from Tokyo. I also used online testimonies from prior participants and organisers.

Runners from outside Tohoku appear to focus on two things: the land “stricken by the disaster,” which they interact with through their feet, and “thoughts for recovery.” Reconstruction seems to benefit both runners and the local area. Runners provide support through their physical presence and entry fee, and in return gain a source of motivation to deliver a solid athletic performance. According to the Tohoku Revival Calendar, a runner from Taiwan confessed to have “fallen in love with this place.”

I interviewed a student from Fukushima, and another from Chiba who has volunteered in the disaster area. In the photo, she is holding a pamphlet from Midette, the Fukushima goods store near Nihonbashi in Tokyo. For both students, the real impact of the TFM is to foster dialogue with local people. “Just listening to both the good and bad points” is enough to dispel “harmful rumours,” and to “know that Tohoku is a good place.” “If people don’t know something intimately, they don’t think about it at all.” Sharing food and laughter with locals is a way to increase one’s feeling of personal responsibility towards local recovery. A lab-mate from Tokyo admitted, “For those who live in Kanto, Tohoku is far away.”

These comments show that those who have been to Tohoku not only have greater awareness of the local situation, but are more likely to support the area once they return home. For example, my friend from Chiba explained that after her volunteering experience, she shared a first-hand account of recovery in Tohoku with her university classmates, providing a counterpoint to persistent false stories on the area. In addition, local people seem to understand best how to organise recovery events, emphasising personal and cultural interaction to produce a lasting impact on participants.

Even so, Tokyo may have two important roles to play. One challenge facing organisers of the TFM is to broaden its international outreach. Only 3% of participants in 2018 were from overseas. Tokyo is Japan’s most visited city by foreign tourists, so it makes sense to raise awareness of TFM in the capital. Takekawa could also ask for more help from TFM’s sister event in France, the Marathon du Médoc. Another, perhaps more important, aspect is bolstering national outreach. This may be important to secure further funding and support. TFM advertisements have popped up on the Tokyo Metro Oedo Line in recent weeks, in a gesture of support from the capital, where they are likely to bring new Japanese recruits.

|

3. 2020 Tohoku Olympics?

In addition to running, Tokyo is also supporting recovery in Tohoku through baseball and softball. Symbolically, the revival of these sports as Olympic disciplines (for the first time since 2008) will take place at Fukushima Azuma Stadium, and for none other than the very first sporting event of the Games. Bathing in the batting spotlight will hopefully highlight local recovery, and promote local pride in co-hosting one of the most popular sports in Japan.

Baseball was pitched to Tokyo from the United States in 1872 and popularized by poet Masaoka Shiki. Back then, baseball’s appeal stemmed from motivation to out-do the American teachers who introduced it. Next year, perhaps baseball will take on a new meaning of resilience in the face of disaster and adversity, symbolised in the photo by the Olympic flyer showing Azuma Stadium in the foreground, against the backdrop of the Shiki memorial pitch in Ueno Park in Tokyo.

Though not all Tohoku prefectures will host Olympic events, the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Committee seems determined to infuse locals with the 2020 spirit. Since 2011, over 100,000 children and adults have taken part in its Sports Smile Classroom and Olympic Day Festa initiatives. Hundreds of Olympic athletes have met with school pupils and parents from across the disaster area. Sports workshops demonstrate to children that they have not been forgotten. Lessons from Olympians’ athletic and mental hardships are being passed on, in the hope they will help surmount hurdles that remain in the protracted process of recovery.

Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures are also competing to provide training facilities for athletes. J-Village, a football training complex 20 km down the coast from the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, was reopened in July as the base of the Japanese national team. Director Masato Yamauchi hopes J-Village will reenergise the local community and encourage evacuees to return. Some point to political motivations, but the decision was not made on a whim. The head of Green Action, a Kyoto-based antinuclear organisation, claims it “is just wrong” to say that Olympic athletes training near the exclusion zone makes the area safe to return to. Of course, the question of safety is primordial. But it seems to me that the point is not to justify nuclear power, but to revive the local morale and economy.

If anything, the Olympic Committee’s contribution to recovery in Tohoku through sport appears bold and ambitious. Not quite the Tohoku Olympics, as most events will be concentrated in the Kanto region, but a strong push for recovery.

Thank you Liu Yan, Shinozuka Hanako, Sato Itsuki, and Egami Haruka for participating in this project.

Going to Tohoku

Hidaka Mari

|

1. Home Sweet Home?

After the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011, many people went to the disaster areas to work as volunteers, especially in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures. According to a survey conducted by the Japan National Council of Social Welfare, the number of volunteers was more than 95 million in 2011, but had decreased to about 28,000 by 2017.

Tohoku tourism, on the other hand, is on the rise. According to a survey published by Tohoku District Transport Bureau on March 22, 2018, the number of tourists in Tohoku region (Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Akita, Yamagata, and Fukushima) was 78 million in 2011, down from 94 million the previous year. By 2015, that number was back up to 84 million, 89% of the 2010 total. Human mobility to Tohoku has certainly changed since 2011. How can we read the effects of 3.11 in the movement of people from Tokyo to Tohoku today?

It is December 30th, 2018. Ueno station is full of people waiting to take the bullet train north. Departures are delayed due to vehicle inspection. Station attendants loudly announce the status of the various lines. People seemed tired of the crowds and the long waiting time.

According to a 2016 survey by LCL, Inc., a company tracking transportation statistics, half of the people returning to their homes in Tohoku over long vacations use bullet trains, most of which stop at stations in the inland areas of Fukushima, Miyagi, and Iwate. The bullet train network was also damaged during the 2011 earthquake, but because of its importance to national transportation, and thanks to lessons learnt from the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995, normal operation resumed on the whole system after just fifty days.

However, restoration of public transportation alone does not make it easy for people to visit Tohoku. Especially for those who were originally from the disaster areas and were forced or voluntarily decided to move away, the simple activity of returning home, which is customary during the New Year, can be a complicated matter. Some Tohoku natives feel shame, especially before family members and old acquaintances, for having abandoned their home, while others feel a sense of guilt for being unable to contribute to the recovery. Even for those who had left Tohoku before 3.11, websites and blogs testify to their inability to fully comprehend or sympathize with the sufferings of those who remained. Emotional distance can be an even bigger hurdle than physical distance for Tohoku natives who wish to return home.

|

2. Would you like to live in Tohoku?

While some residents are leaving Tohoku, there are also people who move there to start new lives. To long-term residents of the Tokyo area, rural areas can look attractive. They stimulate curiosity and have a nostalgic atmosphere. Local governments have made efforts to attract new residents from urban areas, in order to counteract the population decline caused by aging and outmigration. Though Fukushima prefecture has suffered such problems since the late 1990s, the rate of decline accelerated after the accident at the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, so that now the prefecture has only two million residents. To improve this situation, in the fiscal year 2018, Fukushima spent no less than 900 million yen to encourage immigration from outside the prefecture.

In Tokyo, one can find information about moving to Fukushima at Midette, a store selling local Fukushima products near Nihonbashi station in Tokyo. Once a month, the store hosts a free information session, partially funded by the prefecture, for after-work visitors who might be interested in living in Fukushima. In one of the store’s corners, there is a booth with fliers about financial aid for housing and assistance for finding jobs in Fukushima. There are also many fliers about cheap short trips, designed to teach people more about the region. On the day I visited the shop, in a small cafeteria near where the fliers are displayed, people enjoyed local products such as ramen, shimiten (fried rice cakes with filling), and sake. “We hope that people who consult this information can better imagine what life in Fukushima would be like by experiencing its culinary delights in this cafeteria,” said a clerk in charge of the information sessions.

But is encouraging immigration really an effective way to revitalize the area? According to the same clerk, in the first three years following 3.11, there were many people who temporarily moved or permanently settled in the disaster areas, including Fukushima, to support the recovery in some way. As time passes, fewer and fewer are motivated to relocate in this way. In addition, the disaster areas have to compete with the many other prefectures that are attempting to attract new residents through similar appeals. It may be the time to think about the recovery and revitalization of Tohoku from a different perspective.

|

3. Go for! Be Happy!

While I am unable to provide a concrete solution to this problem, few people would disagree that revitalization is an issue across provincial and suburban Japan, and that the centralization of population and industry in the Tokyo Metropolitan area is a major contributing factor. Tokyo thus has a responsibility to help deal with the problem — but what can the city do?

One example is a campaign by East Japan Railway (JR) called “Ikuze, Tohoku,” officially translated as “Off to Tohoku.” After the 2011 earthquake, tourism to Tohoku declined significantly and has yet to return to its former levels. As the Disaster Recovery Policy Division of the Miyagi prefectural government pointed out, to bring tourists back, and especially to attract foreign tourists, Tohoku’s image has to be changed in response to harmful rumors and prejudices about radioactive contamination. “Off to Tohoku” was proposed by Dof Inc, an advertising company based in Tokyo, soon after the disaster. Since it began in 2012, the campaign has tried to improve the situation in Tohoku by spreading positive images of the area as an attractive tourist destination for young women. Campaign posters are prominently displayed in many stations in Tokyo. This winter, they featured such things as hot springs, skiing, and feasts of piping hot foods.

The verb in the campaign’s slogan, “Ikuze” (“I’m gonna go” or “Let’s go”) expresses an almost daredevil willingness to travel to the region. Photos of young women enjoying local food and culture make Tohoku look fashionable. Through the posters, Tohoku is presented as an attractive and trendy sightseeing option for young people.

In discussions about Tohoku’s recovery, the area is typically treated as devastated and miserable, and mass media, local governments, and various experts have clamored about the importance of humanitarian support. However, at this juncture, the best hope for Tohoku’s economy, at least as far as appeals to Tokyo residents are concerned, might be for the region to improve its market value. As “Off to Tohoku” suggests, the consumer society and advertising industry centered in Tokyo might be of help to Tohoku yet.

Fukushima Femme

Vanessa Yue Yang

|

1.

All Fukushima Festa, held at the Tokyo International Forum in Yurakuchō on December 9th, 2018, was diverse and inclusive. Exhibits ranged from local agriculture and designer fashions, to immigration campaigns and government-sponsored reconstruction. What particularly caught my eye among the various themes were the widely used feminine elements.

Fukushima Agriculture Girls Network was one of a handful of women-led and women-oriented groups participating in the fair. They were selling vegetables, rice, bottles of jams, and other agricultural products. According to a study conducted by Mitsubishi Research Institute in 2017, citizens from Tokyo still have significant concerns about the safety of foods from Fukushima. Although people are frequently exposed to news that food produced in Fukushima is not significantly different or more dangerous than that from other places, only around 15% of people reported that they would eat food from Fukushima. When it comes to recommending Fukushima products to families, friends, or foreigners, the number drops to around 10%.

Fukushima Agriculture Girls Network is one response to this challenge. Considering this branding strategy, one will notice that women are associated with images of being careful, considerate, and caring. Through such images, promoters subtly suggest that the products cannot possibly be polluted or dangerous. Furthermore, the group projects the message that not only men but also women are exerting efforts to help revive local land and livelihood. Looking at these images, how could anyone be indifferent to these lovely ladies and their products? This interpretation may sound biased, but consider the fact that there was no “agricultural men’s network” at the fair, nor did any exhibitors use masculinity as a selling point.

This prompts me to further consider the function of gender in Japanese society. In this country of housewives, men assume the major responsibilities of work. When it comes to marketing, however, femininity and female images are frequently used. Therefore, even though men are actively engaged in Fukushima’s revival, the branding process has to suppress images of masculinity and borrow “power” and “charm” from femininity.

|

2.

Excited visitors are queuing to take photos with kawaii character mascots from Fukushima. Close to the mascots, there is a display promoting a “Fukushima Fan Club.” What?! Isn’t a fan club a group of people with a strong passion towards a celebrity or an idol? Oh, maybe “Fukushima” can be understood as a Japanese idol group.

A group called the Fukushima Fan Club assembles its idols upon the display’s backdrop: a sexy peach, colorful flowers, a train traveling in a romantic snowy day, and a cute red akabeko cow, a folk toy from the Aizu area of western Fukushima. These idols/items are used to signify the distinct charms of Fukushima. Similar to posters promoting teenage idol groups in Japan, the theme color of this backdrop is overwhelmingly pink, which indicates warmth, youth, and innocence. Some people may argue that using pink to brand the revival of Fukushima stems from Japan’s national passion for kawaii objects. But from the perspective of psychology, color influences people’s perceptions and feelings profoundly, and pink is thought to be a calming color with specific connotations.

Below the desk, we can see the words “membership recruitment” written on the top of a heart shaped by two interlocked hands. Visitors are invited to fill out membership forms on the desk and enjoy “fan fun” with the club. What kind of fun exactly? To the right of the flag, a campaign leaflet encourages people to post pictures of Fukushima on Instagram in order to win a free trip to the prefecture or produce like beef and cakes. This again resonates with the promotion of idol groups or the pleasures an idol group offers. Visiting a place in person is like having the chance to shake an idol’s hands and feeling the temperature of their body. Getting free food to fill your stomach is like getting a signed poster to satisfy your eyes and sweet songs on a CD to delight your ears.

Sadly, such flashy branding strategy depends on the stagnation of the public’s memory. The Mitsubishi Research Institute study cited earlier also investigated the currency of people’s knowledge about Fukushima. Nearly 50% of people claimed that the latest information that they had acquired about Fukushima dated to 2013 or earlier, while only around 30% of people said that they had kept up-to-date to the time of the survey (2017). In other words, most people’s knowledge of Fukushima is stuck at the immediate post-disaster stage. It is thus hard to imagine that many people would like to join the Fukushima club and enjoy the fan fun.

|

3.

“Let’s Go See Hardworking Miyagi.” Even though, at first sight, this brochure seems to promote Miyagi prefecture alone, upon opening it one finds that it actually covers multiple disaster areas, including Fukushima.

Top center, to the right of two young women raising their arms in “ganbaru” gestures, the large black text reads “a healthy journey to support the recovery” with two pink exclamation marks. To make the cover more kawaii, the designer has replaced two dots inside both the kanji 応and the hiragana び with blue stars. Complementing the ocean-themed, sticker-like icons embellishing the cover, in the center of the brochure, the two women are seen shopping in a seafood market with satisfied faces. Even though there are great concerns about the safety of seafood from the disaster areas, this image implies that it precisely what young women, who are delicate and careful regarding the quality of food, want to eat. The photo on the bottom right similarly shows vegetable being purchased eagerly.

Like other promotional campaigns in Japan, images of young women are used prominently in this brochure. Why are young women preferable? Setting aside the ubiquitous male gaze in society, one can consider these women as travellers. Who will travel for the sake of witnessing or supporting a place’s revival? People who are kind, supportive, and free to do so. Overworked salarymen are thereby excluded. Images of children are not appropriate because their parents may not accept claims of safety so easily. Teenagers are probably not interested in places that lack adventure or extraordinary landscape. Senior citizens are likely very keen on supportive travelling, but unfortunately images of them are not popular. Hence, young women are the best choice.

Not only are young women used to promote tourism, they seem to be the main targets of such campaigns. In addition to the “special” strawberry pizza on the brochure’s cover, inside one finds other food products and dining situations that are typically considered to be attractive to women, such as exquisite cakes and afternoon tea in a photogenic setting.

Are you now motivated to travel to go see the hardworking post-disaster area?

Energy’s New Landscape

Fujimoto Takako

|

1.

Everyone in Japan was shocked by the 3.11 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster that followed. Many Tokyo residents woke up to the fact that urban infrastructure is dependent on the countryside, and that stopping nuclear power plants would require nothing less than urban residents changing the way they live. Some people immediately acted in response to the situation. Three young men who were colleagues in the same company specializing in wind power provide a good and encouraging example.

Surprisingly soon after the disaster, in June 2011, they established their own company, named Shizen Energy Inc. (Shizen denryoku). Isono Ken, one of the founders, says that he and his colleagues were concerned about who would take responsibility for the future after the disaster, and wanted to do what they could to increase renewable energy. He also says they were not interested in just blaming other people. They wanted to do something positive. For the first year and a half, Shizen Energy generated no income. But after completing their first mega photovoltaic power facility in December 2012, their business started moving ahead. The beginning of feed-in tariffs (FIT) for a variety of renewable energy sources in July 2012 also gave them a boost.

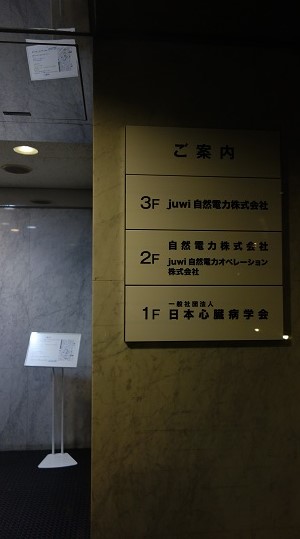

Initially, the company did not have its own generating facilities. They operated instead through a business model known as “asset-light,” which was new in the Japanese energy industry. Shizen Energy learned about this business model from foreign companies like juwi AG, a German company with which they set up a joint venture. Now Shizen Energy supports the building and operating of generating facilities and sells electricity. Their service encompasses not only photovoltaic power but also wind and small hydroelectric plants. They now run three companies with two hundred employees. As their style is unique and new in Japan, the age and nationality of their employees is accordingly diverse: 20-30% are over 60-years-old, and 20-30% are foreigners. Their slogan, “Change society with energy,” is steadily being achieved. Change is never easy. But after 2011, not only did change become more urgent, it also became more possible.

|

2.

While Shizen Energy Inc. has its headquarters in Fukuoka and offices in Tokyo (site of their headquarters until 2014), the power plants they support are all located in the countryside. What kind of activities regarding natural energy exist in Tokyo?

In Setagaya City, where I live, the local government initiated a Global Warming Countermeasures Promotion Program in 2011. In order to reduce CO2 emissions, their goal was for more than 6000 residences in Setagaya City (5% of households) to adopt solar panels.

There have been many non-governmental initiatives since 3.11. NPO Setagaya Energy for All is a group whose goal is to realize a life based on sustainable energy through the use of wind, water, and sunlight alone. In June 2013, the group built a community-funded solar power facility in the neighborhood of Shimokitazawa. According to their website, they instruct citizens on how to renovate their homes for the adoption of renewable energy, advise them on how to network with the Setagaya government and other non-governmental groups, conduct research and provide education about environmental conservation.

Related to these endeavors is Tokyo Shimin Solar, a limited liability company established to build and manage solar power stations in Tokyo in collaboration with local non-governmental groups. They operate eight stations, mainly in Setagaya, which collectively produced 190,000 kwh in 2017.

Alongside the Global Warming Countermeasures Promotion Program, in 2013 Setagaya City has started leasing the roofs of public facilities for the installation of solar panels. Tokyo Shimin Solar has built three stations through this agreement. The photo shows the site of one of these stations, on the roof of Setagaya Electronic Data Processing System Center (though the solar panels are only visible from the air). This station is designed to produce 19.5 kw of energy, enough for five standard-size homes, cutting 8,690 kg of CO2 per year.

Even if we are unable establish a business or change our lifestyles drastically, we can at least join such grassroots activities or chose to be consumers of renewable energy.

|

3.

Of course, new trends bring new problems, and photovoltaic generation is no exception.

Photovoltaic power has been growing steadily in Japan since the enactment of the feed-in tariff (FIT) for home systems in 2009. As the lifespan of solar panels is about 25-30 years, a large amount of solar panel waste is expected around 2040. Photovoltaic generation is relatively easy to start, so many companies entered the market without preparing for this future problem. Some panels contain harmful substances like lead or cadmium. Because of a lack of awareness about these materials, there is a high risk that they will not be properly disposed of. By one estimate, solar panels will account for as much as 6% of all industrial waste in the future.

FIT contracts for photovoltaic generation are ten years. The contracts of approximately 500,000 households will thus expire in 2019. While some people will certainly lose money as a result, this also opens new business opportunities in the use of surplus electricity. Panasonic Corporation is developing new solar energy accumulators. Mitsubishi Electric Corporation has already begun production of a new power conditioner that circulates electricity between solar panels, electric vehicles, and households. Photovoltaic energy is entering a new era.

In December 2018, Hitachi announced that the New Wylfa Nuclear Power Plant in Wales was unlikely to go forward due to lack of investors. In 2011, Japanese companies had similar plans with five other countries, but not a single one has succeeded. With heightened awareness of the risks of nuclear energy, this is the time for advancing renewable energy. In the name of the future, we are now at a crossroads with regard to how we live and how businesses and industries operate. Fukushima may be far away geographically, but the meltdown is directly connected to our daily lives.

The Past is the Future

Noémie Lobry

|

1. Past

Tokyo is a city with no age.

While you can find some old places where signs of the past are still visible, Tokyo’s neighborhoods – in the most disruptive contrast – are full of new buildings showing the latest architectural and structural trends, as if time had no effect on this crazy race toward newness.

Memories of the past are blurred, subjective, altered by one’s gaze, coloured by strange mental hues that are generated by the emotions of moments past. Through the prism of Tokyo, a city altered and transformed by time and events, how can one grasp the process of preparedness that was born after the 3.11 earthquake and subsequent events?

Wandering through Tokyo is a way to revisit the city’s historical relationship to earthquakes. Let’s try to understand issues of preparedness by analysing the evolution of technologies and engineering solutions that have been devised to protect against natural threats.

As I said, everything starts with history. Tokyo has had to face major catastrophes in the past: The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923; World War II and the bombing of Tokyo in 1945, during which the pagoda adjacent to Sensōji Temple in Asakusa was destroyed (the photo here shows its postwar reconstruction); and the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake.

It is interesting that, to date, no five-story pagoda in Japan has ever fallen because of an earthquake. This miracle is ascribed to the “shinbashira” (the central “heart column”) that serves as the pagoda’s core. It has also served as the starting point for engineers searching for concrete, technical solutions in the building of earthquake-resistant structures.

|

2. Present

The present, with its sense of instantaneity, is the hardest part of the timeline to grasp because we don’t have any distance from it. So we try to do the best we can in the moment, with the help of all the things we know and learn. The verticality of things is killing me. The monotone voice of the guy speaking at the moment I’m writing these words is also killing me. This is the present.

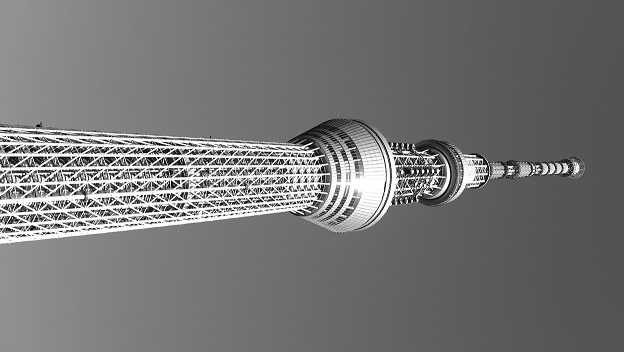

The goal today is to ensure the highest rate of safety in a city where verticality became an increasingly important issue as the population grew. Shibuya, Shinjuku, Akihabara, Ginza – I don’t know which one has the tallest buildings, but I’m sure that every single one of them is superbly designed and equipped against earthquakes. A good example of the use of advanced structural design technology is the Tokyo Sky Tree. Occupying the rank of world’s tallest tower (634m), this tower designed by Nikken Sekkei presents the paradox of modern construction techniques partly inspired by traditional tower architecture.

A cylindrical pillar made of reinforced concrete is installed at the core of the tower. This pillar is structurally separated from the steel framework body of the tower at the periphery, and the upper section of the central pillar serves as a ‘’weight’’ to control vibrational impact. In tribute to traditional five-story pagodas, this is known as the “shinbashira seishin” (central pillar vibration control) system. The tower – a monolithic composition of structural beams – is anchored solidly to the ground, presenting an outline of steel tower framings with a vibration-controlling structure: everything is designed to counteract wind and earthquake-related effects.

Thus, if we are to look for the visible aftereffects of 3.11 in Tokyo today, we should look up, into the sky, at the innovative structure of skyscrapers – or underground, inside the basement of buildings, where, as we will see next, solutions about base isolation are developed out of sight from daily life.

|

3. (the)Future: (is)Research

The Coordinating Committee for Earthquake Prediction is busy. There is no doubt that an earthquake with a magnitude larger than 7.0 will occur again in Japan, perhaps in the near future. This means one thing: national preparedness must be increased before the next big one arrives. Thanks to national research projects, preparedness is being advanced and perfected.

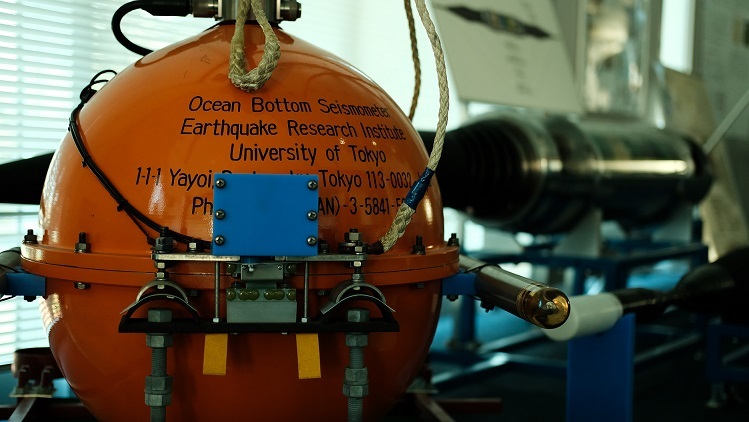

This photo was taken at the Earthquake Research Institute (ERI) at the University of Tokyo. It shows an Ocean Bottom Seismometer, a device whose basic function is to collect information about underwater seismic activity and transmit it to ships and control centers on land. Many technologies of this type are developed in this lab.

Information about ERI’s research activities can be found on the lab’s website. Muography, one such frontier, is an imaging technique that produces a projectional image of a target volume by recording elementary particles called muons. The technique is similar to radiography but capable of surveying much larger objects. It was used, for example, to locate melted nuclear fuel inside the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after the facility was damaged by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Explanation about base isolation – laminated rubber and steel plates – can also be found displayed in the building. The purpose is to prevent kinetic energy from earthquakes from being transferred into elastic energy in buildings. Metal roller bearings, for example, are used in housing complexes in Tokyo to prevent them from collapsing if any earthquakes occur.

Developing new technologies and finding innovative architectural solutions for earthquake-resistant structures remains an important issue in Japan. Research is the best path to find such solutions and secure a safer future.