2018 was the 20th anniversary of Reformasi, the people-power movement that toppled authoritarian leader Suharto, after 32 years in power, and ushered in Indonesia’s democratic transition. The world’s largest Muslim-majority nation has since made significant reforms to its political system to become the world’s third biggest democracy. The military has been removed from parliament and serving officers are banned from politics so that the military no longer has a formal role in the political process. Wide-ranging decentralizing measures were also introduced as an antidote to the stifling centralisation of Suharto’s New Order regime, and the country’s first direct presidential elections were held in 2004.

Nonetheless, the first four post-Suharto Presidents have been, to a lesser or greater degree, members of the political establishment. B.J Habibie (1998-99) was a Suharto protégé and as Vice President succeeded Suharto when his mentor stepped down. Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001) was not a member of Suharto’s inner circle but had succeeded his father as leader of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest non-governmental Islamic organisation in the world. Megawati Sukarnoputri (2001-04) is the daughter of Sukarno, Indonesia’s first President who was ousted by Suharto. Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014), the first directly elected President, was a retired general who rose through the ranks under Suharto and served as a military representative in parliament where he participated in Suharto’s election to a seventh term as President in March 1998. Wahid was the only one of the four who did not serve in cabinet before ascending to the highest office, although Megawati’s cabinet experience came as Vice President under Wahid.

Consequently, the 2014 election of Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, appeared to change Indonesia’s political landscape since he became the first post-Suharto President not to come from the existing political elite. Prior to standing for the presidency, he had been a popular governor of Jakarta, known for his informal style and transparent leadership, and had been widely predicted to win in the presidency in a landslide. However, his final victory over oligarch and Suharto son-in-law Prabowo Subianto was much closer than expected and highlighted the extent to which the shadow of the Suharto era, and the power of the oligarchs, still loomed over Indonesia even as a reformist candidate assumed the highest office. The 2019 presidential elections appear set to become a reprise of 2014 with the same two contenders contesting it again.

Upon assuming office Jokowi faced high expectations due to his extraordinary rise. This paper will consider the strength of democratic consolidation in Indonesia, with particular reference to the last general election of 2014. Thereafter, it will present a brief assessment of the intervening four years of Jokowi’s first term exploring the political landscape ahead of the forthcoming elections. Since the 2014 election campaign Jokowi’s message has consistently been one of economic growth, transparent government and moderate Islam, centred around improved infrastructure and social welfare. This paper finds cause for cautious optimism thanks to ambitious reforms in healthcare and education, infrastructure development and sensible fiscal management. However, challenges remain, notably an increasingly assertive political Islam and somewhat disappointing levels of economic growth.

Democracy Consolidated?

The outcome of the 2014 elections suggested the possibility that democratic stability in Indonesia had been consolidated. After the fall of the Suharto regime (1966-98) free and fair elections were successfully conducted in 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014, as Indonesia became the most free country in Southeast Asia.1 Indeed, Indonesia was the only state in Southeast Asia to be ranked ‘free’ in terms of both political rights and civil liberties by independent watchdog Freedom House in its country rankings for 2011, 2012 and 2013. However, in 2014 it regressed to ‘partly free’ status due to new restrictions on mass organisations and continuing harassment of minorities. Despite Jokowi’s reforms, in the 2019 rankings Indonesia remains only ‘partly free’, with East Timor considered the only ‘free’ country in Southeast Asia.

Post-Suharto improvements in both political freedom and civil liberties mean that Indonesia is now also one of the most-free Muslim-majority states, behind only Senegal and Tunisia in Freedom House’s country rankings for 2019.2 Since the 1950s Indonesia has aspired to play a leadership role both among developing countries, as one of the founders of the Non-Aligned Movement, and in ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), as the region’s biggest country and economy. Key elements of the post-Suharto transition to democracy have been the removal of the military from politics, a greater role for civil society in framing policy, a largely free media and the expansion of political parties. Although challenges remain, in particular the protection of minority rights, democratic reinforcement in Indonesia is especially symbolic regionally given ongoing military rule in Thailand, an authoritarian revival in the Philippines and Myanmar’s still uncertain political transition. With these challenges in mind, the Economist Intelligence Unit classifies Indonesia as a ‘flawed democracy’, ranking it 65 out of 167 states, based on 60 indicators measuring civil liberties, political participation, electoral process, functioning of government and political culture.3 Other observers have characterised it as an illiberal democracy, citing the administration’s mainstreaming of a conservative and intolerant form of Islam along with its use of the security apparatus to silence dissent.4

Indonesia’s first two direct presidential elections, in 2004 and 2009, seemed to indicate that democracy was indeed becoming consolidated in the wake of the Suharto dictatorship. Both were won by Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (hereafter SBY), who had earned a reputation as a military reformist before retiring from the armed forces and entering cabinet for the first time in 1999 under Wahid. SBY won two presidential elections standing for clean government and political reform, with a particular emphasis on getting tough on the country’s endemic corruption. He promised to personally direct the campaign against corruption, which set him apart from his predecessors Habibie, Wahid and Megawati. During SBY’s first term, a succession of high-profile corruption prosecutions demonstrated that his presidency was taking a different course from any previous administration. This paid off with an increased mandate gained in the 2009 parliamentary and presidential elections.

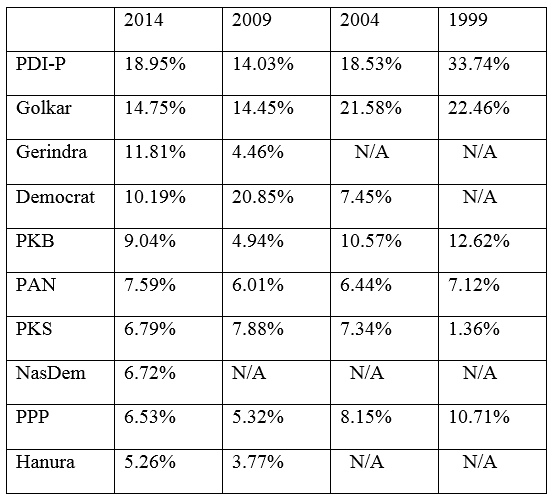

Riding the wave of a global commodities boom, SBY was also able to preside over consistent economic growth of almost 6% annually during his decade in office. In this period Indonesia replaced Malaysia as world’s largest exporter of of palm oil and increased its exports of other resources such as coal, rubber, copper and gold.5 Largely driven by high demand from China, elevated prices for these and other resources enabled SBY to deliver much-needed political stability to Indonesia. The global resources boom cemented support for both the President personally and Indonesia’s transition to democracy. Post-Suharto electoral reforms limit the President to a maximum of two five-year terms in office, and thus SBY was unable to stand for re-election in 2014.

Compared with his first term, however, SBY’s second term in office disappointed many of his supporters as political reform stalled and party allies became embroiled in corruption scandals. Most notably, Democrat party treasurer Muhammad Nazaruddin was convicted of receiving bribes in relation to bids for the 2011 Southeast Asian games, hosted that year by Indonesia. Nazaruddin exercised control over the funding of public works, and was subsequently ensnared in further corruption scandals during SBY’s second term. The President’s increasingly hands off approach saw his popularity plummet as his public approval ratings gradually spiralled down from 75% in November 2009, to 57% by January 2011 and 30% in May 2013.6 Although corruption prosecutions did rise somewhat in 2013, a general lack of progress ensured that in 2013 Indonesia was still ranked 114 of 177 countries by Transparency International in its annual report on corruption perceptions.7 Thus, the elections of 2014 were to be something of a litmus test for Indonesia’s democratic transition.

The 2014 Elections

Indonesia is the world’s third largest democracy, and voter turnout was 78% and 86% in the first two direct presidential elections of 2004 and 2009 respectively. However, turnout fell to just under 70%, from a total of 194 million eligible voters, in the presidential elections of 2014. Even though population growth means the total number of eligible voters keeps increasing, falling voter turnout suggests that a degree of voter apathy is setting in as elections become normalised. Election rules state that only parties or coalitions that gained a minimum of 25% of the votes in the parliamentary elections, or that control 20% of seats in the People’s Representative Assembly (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR), are able to nominate a presidential candidate and running mate for the presidential elections. These rules virtually guarantee that even the largest political parties have to forge coalition partnerships with smaller parties in order to field presidential candidates.

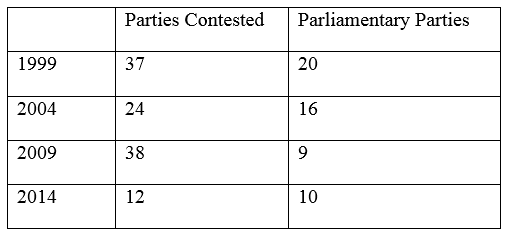

For most of the Suharto period only three political parties were allowed to contest elections, which were heavily manipulated to ensure victory for the President’s Golkar party vehicle. The removal of such restrictions after Suharto’s fall resulted in a rapid mushrooming of new parties (see table below). However, the 2014 parliamentary elections indicated that Indonesian politics is becoming increasingly consolidated among the established parties, especially compared with 2009, when 38 parties contested the national elections but only nine secured enough votes to be represented in parliament. In 2014 only two parties out of 12 did not meet the 2014 threshold of 2.5% of the national legislative vote. Under election rules, these two parties also forfeit the right to contest the next parliamentary elections scheduled for April 17, 2019.

In essence, the 10 parties represented in parliament can be classified as either secular or religious parties with relatively small differences between them in policies. There have been no parties of the left since the violent eradication of the Indonesian communist party in 1965-66. A distinctive feature of post-Suharto parliamentary politics has been the existence of large ruling coalitions, which has been enabled by the relative lack of ideological differences between the parties. The current grand coalition is the largest of all the post-1998 coalitions and consists of the PDI-P, Golkar, NasDem, Hanura, PPP and PKB bringing together both secular and religious parties. Indeed, building and maintaining this large coalition has been one of Jokowi’s most notable political achievements.

The biggest parties PDI-P, Golkar, Gerindra and Democrat are all secular, while the smaller parties of PKB, PAN, PKS and PPP are all Islamic parties. NasDem and Hanura are also secular in outlook but like Gerindra and Democrat they were established solely as vehicles for their leaders to contest presidential elections. The ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, PDI-P) is the most secular party with Gerindra being the least so of the nominally secular parties.8 The PDI-P was formed in 1973 when Suharto forced five non-Islamic political parties to merge into one, and originally consisted of three nationalist entities and two Christian parties. Since then its core constituency has been voters who want Indonesia to remain a secular pluralist state, in contrast to neighbouring Malaysia whose national constitution specifies Islam as the sole state religion, albeit with sharia laws used mostly for Muslim family matters. During the last decade of the Suharto period the PDI-P also began appealing to lower-income voters alienated by rising inequality, and the party has maintained this support base in the Reformasi era.9 The other long-standing secular party Golkar was established by Suharto as a vehicle to provide him with electoral legitimacy in the 1971 legislative elections, the first since Suharto’s seizure of power in 1966. Golkar was the ruling party from 1971 until the first post-Suharto elections in 1999. Golkar under Suharto was not actually formulated as a political party but as a non-ideological corporatist grouping that focused solely on economic development and political stability rather than any specific political agenda. As such, its identity was closely bound to that of the Suharto regime and all government employees were strongly encouraged to vote for it as a sign of loyalty. Despite having to rebrand itself in the competitive electoral politics of the Reformasi era, its party platform still emphasises a central role for the state in social and economic development and it maintains its large party political network across the sprawling archipelago.

Unlike Golkar, Gerindra has remained outside of Jokowi’s grand coalition since the 2014 elections. Instead, Gerindra has formed a close alliance with Islamic parties PKS and PAN as the core opposition to Jokowi. In terms of ideological differences, Islamic parties are less tolerant of pluralism than the secular parties. In particular, one issue that the Gerindra and the Islamic parties in opposition have coalesced around is the question of Muslim economic deprivation in a country where Chinese Indonesians, around 90% of whom identify as Christian or Buddhist, are perceived to control the economy and a disproportionate amount of the national wealth.10 Chinese Indonesians account for only 1.2% of the population but they own many of the country’s largest conglomerates, and this has long made them a target for Islamists and nationalists. Foreign investment, especially from Japan and China, has also been perceived by critics to benefit Chinese Indonesian businesses at the expense of indigenous Indonesians. Regarding Muslim economic deprivation, most lawmakers from Gerindra, PPP, PKS and PAN believe it exists in Indonesia, whereas most MPs from Jokowi’s ruling coalition do not believe it exists.11 Opposition MPs look to neighbouring Malaysia as a prime example of positive discrimination for indigenous Muslims. Since 1971 Malaysia, also with a wealthy ethnic Chinese minority and many similarities to Indonesia, has implemented wide-ranging affirmative action policies designed to increase indigenous Malay participation in the upper and middle class. In the 2010 census 87.2% of Indonesia’s population identified as Muslim compared to 61.3% in Malaysia’s 2010 census.

The question of Muslim economic deprivation in Indonesia also highlights some of the differences among the Islamic parties. For example, most lawmakers from the PKB agree with their secular coalition colleagues that such deprivation is not an issue, in contrast to the other Islamic parties.12 PKB (Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa, National Awakening Party) and PAN (Partai Amanat Nasional, National Mandate Party) both stand for moderate Islam and both were founded in 1998 as political space opened up after Suharto’s resignation. Although moderate they are rivals since they represent Indonesia’s two largest Islamic organisations, the NU and the Muhammadiyah respectively (see below). PPP (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan, United Development Party) and PKS (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, Prosperous Justice Party) are generally less moderate, both having previously supported the implementation of sharia law at a national level in Indonesia. The PPP was established in 1973 when Suharto forced several Islamic parties to merge and it now stands for economic nationalism with a major role for state-owned firms. The PKS was formed in 1998 and is ideologically located farthest to the right of the Muslim parties despite having dropped the implementation of sharia law from its party platform. For example, the party is known for its tough stance on pornography and narcotics, and insists Indonesian Muslims should follow Islamic law (see below).

|

People’s Representative Assembly (DPR) election parties |

|

People’s Representative Assembly (DPR) election results13 |

Alongside this political consolidation among parties, political trends in Indonesia since 2004 have gradually shifted away from established parties towards a greater emphasis on individual candidates. SBY exemplified this trend as the party vehicle constructed around him, the Democrat Party (Partai Demokrat, PD), was only founded in 2001 in order for him to contest the 2004 Presidential elections. It was founded as a secular centrist party, with an emphasis on economic liberalisation and a core constituency in the urban middle class. In the 2009 parliamentary elections it secured the most votes of any party (almost 21%) but by 2014 had fallen to only fourth (10.2%), closely reflecting perceptions of SBY personally. This shift away from loyalty to a particular party is also demonstrated by public opinion polls. The proportion of voters who said they identified with a particular party declined from 50% in 2004 to only 15% in March 2014.14 SBY’s success subsequently prompted two of his former New Order military superiors to establish their own political vehicles to carry their own presidential ambitions. These are the Hanura Partai (People’s Conscience Party) of former Armed Forces Commander Wiranto, formed in 2006, and Gerindra of former Special Forces Commander Prabowo, established in 2008. With the retreat of the military from parliamentary politics under Reformasi, Suharto-era military leaders such as SBY, Prabowo and Wiranto have had to form their own parties to contest elections since generals are no longer guaranteed power and influence in Golkar, Suharto’s former party, still less are they guaranteed election.

The weakening of party loyalties has also reduced barriers to entry into national politics for popular individuals such as Jokowi, who began to attract wider media coverage only after his 2010 landslide re-election as mayor of his hometown Solo in Central Java province. His subsequent election as governor of Jakarta in 2012 propelled him to national attention, and his achievements in office added to his lustre. These included introducing smartcards to provide free access to education and health care for the poor, and establishing a programme to distribute school uniforms, shoes, books and bags to families most in need. He also kickstarted the long-delayed, and much-needed, construction of Jakarta’s Mass Rapid Transit network, and shook up the recruitment process for management positions in city government. This was in marked contrast to his predecessors as Jakarta governor who achieved relatively little.

When he stood for election as mayor of Solo and later as governor of Jakarta, Jokowi represented Megawati’s PDI-P party. His meteoric rise prompted fierce speculation that he would not serve out his gubernatorial term to 2017 but would instead seek the presidency in 2014. Elements within the PDI-P were opposed to his candidacy as an outsider and newcomer, most notably Megawati’s husband Taufik Kiemas and daughter Puan Maharani, who sought to lead the party herself. There was also much speculation that party matriarch Megawati would like one last run at the presidency. However, by mid-2013 Jokowi had secured strong support from the party’s youth wing and, crucially, most party branches who viewed him as the best chance for local PDI-P politicians to win seats in the 2014 parliamentary elections.15 Jokowi was finally declared the PDI-P presidential candidate on 14 March, just before the onset of official campaigning for the legislative elections between 16 March and 5 April. Megawati and her family had reluctantly embraced Jokowi’s presidential candidacy but had no intention of surrendering control of the party to an ‘outsider’.16 Megawati has remained party chairperson.

Prior to the campaign period, Jokowi had enjoyed a comfortable lead in opinion polls over the other frontrunners, Prabowo and Golkar candidate Aburizal Bakrie. Thanks to Jokowi’s personal popularity, it appeared that the PDI-P might even repeat its high water mark performance of 1999 when it secured almost 34% of the vote. However, a lacklustre and disjointed campaign by the party resulted in a much closer election (see table above). One reason for this is the fact that Jokowi hardly appeared in the PDI-P’s campaign TV commercials which mostly featured Megawati and daughter Puan Maharani. Jokowi only began to appear regularly in the ads during the last two days of official campaigning. Voters could be forgiven for thinking that Jokowi was not standing on the PDI-P ticket, and this undoubtedly cost the party votes. By contrast, Prabowo and his billionaire brother Hashim Djojohadikusumo spent large sums on political advertising and TV air-time. Other leaders and parties used their own media outlets to promote their candidacy. Golkar chairman Aburizal Bakrie owned two TV stations, TV One and ANTV, while Hanura vice presidential candidate Hary Tanoesoedibjo owned the Media Nusantara Citra (MNC) Group, one of Southeast Asia’s largest media networks which ran 4 of Indonesia’s 11 free-to-air TV stations in addition to magazines and national and regional newspapers. Once campaigning was underway these media outlets halted their positive coverage of Jokowi and published stories portraying him in a negative light as Jokowi was now a political rival of their owners.17

After finishing a distant second in 2009 to SBY’s Democrats, in 2014 the PDI-P won a parliamentary election for the first time since 1999 and its next challenge was to get its candidate into the highest office for the first time since 2004 (see table above). However, their complacent campaign resulted in the PDI-P securing only 19% of the parliamentary vote, below the threshold of 25% of the parliamentary vote or 20% of parliamentary seats, forcing Jokowi and the PDI-P to secure coalition partners in order to contest the presidential election. In the end, the PDI-P coalition comprised the PKB; the new NasDem Party of media tycoon Surya Paloh; and Wiranto’s Hanura.

Unlike in the first two direct presidential elections of 2004 and 2009, contested by five and three candidate pairs respectively, in 2014 there were only two candidates. Opposing Jokowi was the controversial oligarch Prabowo. Even though his own election vehicle Gerindra had secured only 11.81% of the parliamentary vote, Prabowo successfully constructed a coalition of Suharto’s former Golkar Party backed up by three Islamic parties: PAN – whose leader Hatta Rajasa became Prabowo’s running mate – PKS and PPP. SBY’s Democrat Party also threw its weight behind Prabowo as the election neared. As Mietzner (2014) notes, contributing to the wide-ranging support that Prabowo secured was Jokowi’s announcement that he would break from tradition and not guarantee ministerial positions to his coalition partners.18 With the support of the Muslim parties Prabowo was able to attack Jokowi’s religious credentials, accusing him of being an ethnic Chinese communist and forcing Jokowi to make a last ditch pilgrimage to Mecca. This smear campaign made the final vote tally much closer than originally anticipated.19 With voter turnout at 70.2% Jokowi secured 53.15 % of the vote, and Prabowo 46.85%. Just six months earlier, opinion polls had indicated that Jokowi had a substantial lead over Prabowo.

In complete contrast to Jokowi, the British and Swiss educated Prabowo comes from the Indonesian establishment and has a murky past. His father Sumitro was an influential economist who held cabinet posts under both Sukarno and Suharto, and Prabowo himself was a controversial figure during the late Suharto period. His rapid rise up the military hierarchy was seen as closely linked to his marriage to Suharto’s daughter. Having held command posts in both East Timor and West Papua, Prabowo was implicated in several cases of human rights abuse, and also played an incendiary role in the riots and demonstrations that accompanied the fall of his father-in-law in 1998. Prabowo was widely believed to be agitating to become Suharto’s successor, first by capturing the post of Armed Forces Commander held by Wiranto. Troops under Prabowo’s command acted as agent provocateurs in kidnapping student activists and stoking the 1998 riots that precipitated Suharto’s fall, apparently in order to portray Wiranto as weak for not dealing more forcefully with the protests. However, Suharto’s successor B.J. Habibie faced down Prabowo’s demand to be appointed Armed Forces Commander and Wiranto kept his post. Since then Prabowo spent a period of exile in Jordan, was refused a US visa in 2000 over his human rights record and returned to Indonesia to join the family business, before starting his political career.

|

Jokowi (left) meets Prabowo (right) in December 2016 |

The Economy

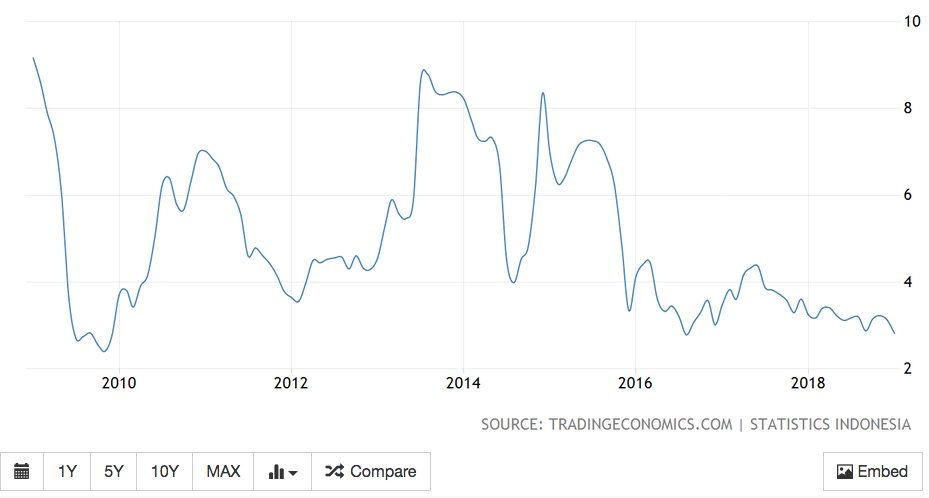

Jokowi won the presidency by pledging to deliver a large infrastructure program that would create jobs, raise people’s income and provide annual economic growth of 7%. During the two decades preceding the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 Indonesia’s annual economic growth averaged just over 7%, and returning to 7% growth was a key target of Jokowi’s presidency. However, it has only averaged around 5% since his inauguration, compared with just over 5.5% during the 2004–14 presidency of his predecessor SBY. Therefore, instead of attacking Jokowi’s religious credentials, as in 2014, Prabowo is focusing on his opponent’s economic track record, and is quietly confident that slower growth will help him win this time. Nonetheless, Jokowi’s team has not performed so badly considering that SBY benefitted from high commodities prices whilst his successor has faced falling global prices. Indonesia’s Central Bureau of Statistics (Badan Pusat Statistik, BPS) recently reported 5.17% GDP growth for 2018.

|

GDP growth in Indonesia since 2000. Source: Trading Economics |

Another 2014 campaign promise was to increase foreign investment in Indonesia, which has lagged compared to the Suharto-era. In particular, Jokowi has targeted greater investment in manufacturing and other value added industries to reduce the economy’s dependence on natural resource exports and attendant price volatility. BPS data from August 2018 shows that manufacturing employs 14.72% of the workforce, compared to 28.79% in agriculture, the biggest sector by labor force. One of the biggest hurdles to doing business in Indonesia has long been red tape and the lack of coordination between the bureaucratic agencies. In order to promote investment, the Jokowi administration has relaxed some rules on investment regarding foreign capital ownership levels and opened up more business fields to foreign entry. However, the dominant ideology in Indonesia remains economic nationalism which Jokowi has also practiced when dealing with multinational resource firms. In December 2018 the President announced that the state had become the biggest shareholder in PT Freeport Indonesia, which operates the huge Grasberg gold and copper mine in West Papua, after increasing its stake from 9.36% to 51.23% in a US$3.85 billion deal. The government had previously announced that state firm Pertamina will take over operations at Indonesia’s biggest oil block from Chevron in 2021. In 2018 Pertamina took control of the country’s largest gas block from France’s Total and Japan’s Inpex. The capacity of Indonesian firms to operate such large assets has been questioned, and such moves could deter future foreign investment, especially since Prabowo has also attacked foreign ownership of natural resource assets in both of his presidential campaigns.

Despite lower than anticipated levels of investment, unemployment is at its lowest level for almost two decades (see below). Indeed, 10.3 million new jobs were created between 2015 and 2018, exceeding a 2014 campaign promise to create 2 million new jobs annually. Moreover, low inflation has been kept under 5%, resulting in more disposable income and household spending. The poverty rate also fell to 9.82%, the first time since independence in 1949 it has dipped into single figures, with the total number of poor decreasing by around 2 million to 25.7 million since 2014, according to BPS data from September 2018. Much-needed infrastructure upgrades are improving physical and digital connections to previously inaccessible areas, and these factors have all combined to boost Indonesia’s sovereign credit rating over the last four years to ‘stable’.20

|

Unemployment in Indonesia. Source: Bloomberg |

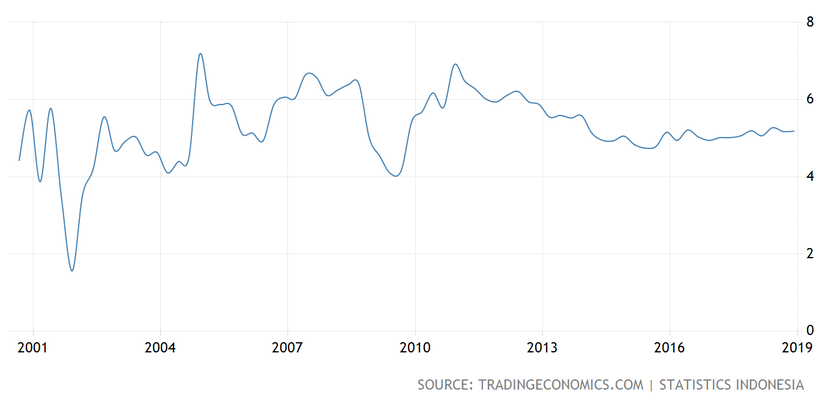

During 2018 Jokowi would have been concerned about the continuing slide of the rupiah, which has lost around 11% of its value to the dollar in 2018 and dipped to a low of Rp15,242 in October, its lowest value since it hit Rp16,800 in January 1998. It continued to fall for most of 2018 despite central bank injections of around US$12 billion to stabilise the currency. A weak rupiah is particularly worrying as the amount of debt being accumulated by state-owned enterprises to pay for infrastructure upgrades since these loans are mostly denominated in dollars, while revenues are received in local currency. A falling rupiah makes dollar-denominated debt more expensive to service. Whilst the rate of decline was nowhere near as sudden and precipitous as in 1997-98, when the rupiah nosedived from a pre-crisis rate of Rp2500 to the US dollar to Rp16,800 in just four months, such instability undermines investor confidence. Bank Indonesia has responded by increasing interest rates five times in recent months in order to dissuade capital flight and, in order to contain the rupiah’s fall, higher tariffs have been imposed on some consumer goods. The central bank’s efforts seem to have paid off as the rupiah appreciated in January 2019 to reached its highest level since the end of June 2018. Higher tariffs also target Indonesia’s trade balance, which had been swinging between surplus and deficit with a reported US$944 million deficit in August becoming a US$230 million surplus in September, and then a US$1.82 billion trade deficit the following month. The October figures prompted Prabowo, in the heat of the election campaign, to claim that he would stop all food and energy imports. By the end of 2018 Indonesia had recorded a trade deficit of US$8.6 billion, the largest annual deficit for 44 years.

|

US dollar to Indonesian Rupiah exchange rates between 3 March 2009 and 28 February 2019. Source. |

In reality, Indonesia’s public finances remain in reasonable shape, thanks to low government debt, legally restricted to 3% of GDP in a fiscal year, and over US$100 billion in foreign currency reserves. In his August 2018 state-of-the-nation address to the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), Jokowi lauded his economic achievements and drew particular attention to his government’s progress in funding welfare and public infrastructure. Regarding the former he cited the Indonesia Smart Card (Kartu Indonesia Pintar, KIP), which by 2017 had been received by 20 million children to enable them greater access to education, and National Health Insurance (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, JKN) which was launched in 2014 to provide universal coverage to the whole country by 2019. KIPs provide Rp1 Million (US$70), Rp750,000 (US$55), and Rp450,000 (US$30) annually for students at senior high, junior high and elementary schools respectively to buy uniforms, bags and stationary. JKN aims to integrate various existing national and district-level health insurance schemes to provide all citizens with access to public health services, as well as from private organisations that have joined the scheme. However, due to soaring costs some medical treatments are no longer being provided for free under the JKN scheme. Nonetheless, Jokowi noted in his address that, “The government has gradually increased the number of (JKN) beneficiaries from 86.4 million in 2014 to 92.4 million in May 2018”, and that Indonesia’s “Human Development Index has increased from 68.90 in 2014 to 70.81 in 2017.” 21

|

The various education and health cards introduced by Jokowi. The family head gets the KKS, school children get the KIP, and all family members get the KIS. Source. |

In order to fund these expanded social welfare programmes in health and education, as well as infrastructure upgrades, one of Jokowi’s first big moves as president was the politically risky cut in the country’s fuel subsidy, a decision long avoided by his predecessors. France’s recent experience with Yellow Vests movement, which began in November with protests against rising fuel prices, illustrate the risk Jokowi was taking. However, the subsidy consumed up to a fifth of the national budget at times. Jokowi reduced it from approximately Rp276 trillion to Rp65 trillion, allowing him to divert these funds to his infrastructure and social welfare programmes.

The 2019 Elections

In policy terms, both Jokowi and Prabowo are standing on a similar platform of clean government and the need to enhance legal certainty in order to promote investment. Jokowi is hoping his ambitious social welfare policies and reforms will carry him to a second term, emphasising his record on job creation and poverty reduction. In order to further appeal to lower income voters, Jokowi has also been touting the expansion of a card scheme that provides free food to the poor and needy. Prabowo too has been campaigning on a populist platform of lower food and fuel prices that will likely revive fuel subsidies and threaten Jokowi’s social welfare and infrastructure programs. The opposition has pledged to cut business and individual income taxes, increase the salaries of civil servants, doctors and police officers, and reduce agricultural imports to protect Indonesian farmers. Prabowo has also attacked the government’s economic management by highlighting the falling rupiah, soaring public debt and widening trade deficit, which Prabowo has promised to reverse by boosting self-sufficiency in energy and food.

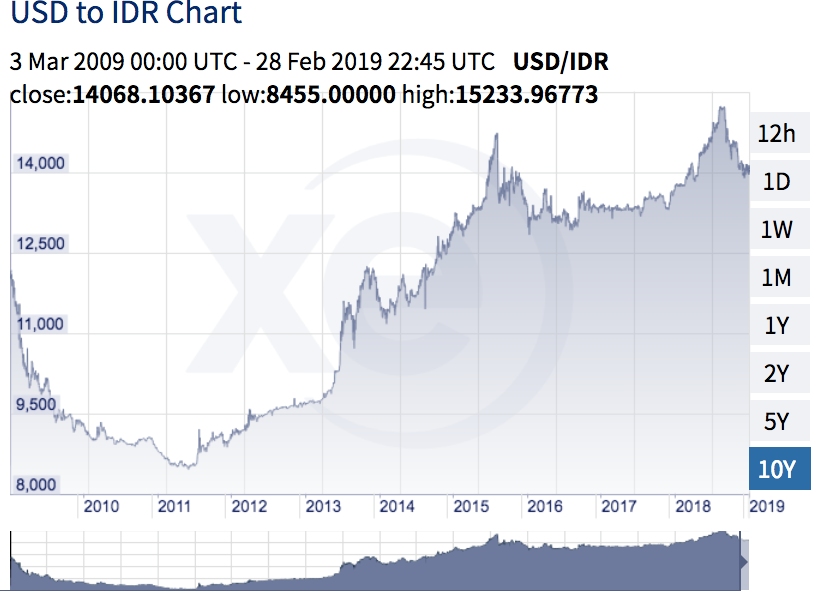

In response, Jokowi has postponed further planned cuts to fuel subsidies. On October 11 he signed off on an average 7% price increase for diesel fuel only to cancel it just an hour later after considering its effect on low-income earners and his own prospects for re-election.22 Introducing price freezes for electricity and fuel prices until the end of 2019 were among a set of policies aimed at curbing inflation as he seeks re-election and to sidestep attacks by the Prabowo camp on his economic track record. This is despite the fact that inflation is running at historically low levels by recent Indonesian standards (see graph below).

|

Inflation in Indonesia from February 2009 to February 2019. Source: Trading Economics |

Campaigning for the 2019 elections officially began on 22 September across all of Indonesia’s 34 provinces. Prior to that local elections were held on 27 June with more than half of the electorate of 152 million registered voters tasked with choosing new leaders for 17 provinces, 115 regencies and 39 cities. With more than half of Indonesia’s population, the island of Java is viewed as the key election battleground and results there were encouraging for the President and his PDI-P party. In particular, West Java and Central Java are key provinces for the 2019 presidential election, controlling nearly 40% of eligible votes and considered barometers of public opinion. The results in West Java were most closely watched given that it is a conservative area of 47 million and Indonesia’s most populous province. As West Java also has the country’s second highest employment rate after neighbouring Banten, and the highest total number of unemployed, the result there is seen as a judgment on Jokowi’s economic stewardship, especially since Prabowo won 59.78 % of the province’s vote in the 2014 presidential election. Since that stinging defeat Jokowi has made considerable efforts to woo West Java, especially since the province is a major business center. These efforts include significant investment in new infrastructure for the province and making impromptu visits to Islamic boarding schools in much the same way he used local markets to rally support in his successful campaigns for the presidency and the Jakarta governorship. West Java’s adjacency to Jakarta has also made it easy for Jokowi to make more visits to the province than any other since his election, more even than to his home province of Central Java.

Jokowi’s camp scored an encouraging victory in West Java when Ridwan Kamil, a University of California Berkeley-educated architect won the provincial governorship despite opposition from Islamists who tried to smear him. Kamil, the former mayor of Bandung, gained a reputation for progressive governance while transforming Indonesia’s third-largest city with more green spaces, better public transport and bureaucratic transparency. His gubernatorial candidacy was supported by four parties in the ruling coalition, namely NasDem, PKB, PPP and Hanura, on a platform of replicating his reforms in Bandung by transforming West Java into a ‘smart province’. The outcomes in the next three most populated provinces of East Java, Central Java and North Sumatra, are regarded as other major indicators of presidential election outcomes. In Central Java PDI-P candidate Ganjar Pranowo secured a healthy victory and another Jokowi ally, Khofifah Indar Parawansa won East Java. However, in North Sumatra Jokowi’s PDI-P candidate Djarot Saiful Hidayat, a former governor of Jakarta, lost to local man Edy Rahmayadi who was born in neighbouring Aceh province. Despite their defeat, opposition candidates also fared far better than expected in both Central and West Java, helped by the close coordination between Prabowo’s Gerindra and the PKS, its parliamentary coalition partner, in their selection of gubernatorial candidates. The 2018 local election results could be significant insofar as recently elected governors can help mobilise support for presidential candidates. For example, the governors of West Java, West Sumatra and West Nusa Tenggara, were thought to be instrumental in winning those provinces for Prabowo during the 2014 presidential election.23

Meanwhile, Jokowi’s predecessor SBY has endorsed Prabowo for 2019, and since leaving office has had a somewhat turbulent relationship with the Jokowi government. SBY has accused it of tapping his phone while Jokowi’s PDI-P party responded by implicating SBY in the July 1996 attack on its headquarters in Jakarta. Jokowi ruled out Agus Harimurti, SBY’s eldest son, as his running mate earlier this year, and SBY responded by trying to get Prabowo to select Agus as his running mate instead. However, that failed too, with the selection of Sandiaga Uno, the deputy governor of Jakarta, who was apparently Prabowo’s fifth choice. Nevertheless, SBY has continued to verbally back his former military colleague. However, without his son on the ticket it is clear that SBY’s Democrats would focus on the concurrent parliamentary elections, prompting the Gerindra secretary general to accuse the former president of not campaigning for Prabowo. Moreover, while in 2014 Prabowo could draw on significant financial resources for his campaign, rumours persist that he no longer has the same funding in place this time. Hence, Sandiaga Uno was able to secure his selection as running mate by making a large campaign donation. Meanwhile, during his time in office Jokowi has worked hard to construct and maintain a powerful coalition of large political parties, enhancing his chances of winning a second term.

|

Prabowo (left) and running mate Sandiaga Uno during the first presidential debate. |

Nonetheless, a coalition of Gerindra and the Democrats, the third and fourth biggest parties in parliament respectively, should certainly bolster Prabowo’s challenge for the presidency. The Muslim PKS also has a well-developed nationwide network, which helped organise the mass rallies against the Jakarta governor of late 2016 (see below), and which has now been tasked with mobilising support for Prabowo’s presidential campaign. Jokowi continues to enjoy high approval ratings and a lead over Prabowo. As in 2014, Jokowi has maintained a consistent lead in opinion polls, and approval ratings of between 60% and 70%. However, his predecessor SBY was averaging around 80% in approval ratings prior to the 2009 elections in which SBY won a landslide, so a Jokowi victory cannot be taken for granted. This is especially so since Prabowo has built a reputation as a strong campaigner who will probably cut into Jokowi’s lead in opinion polls. A January survey gave Jokowi a lead of 53.2% to 34.1% for Prabowo, with 12.7% still undecided. Support for the President is strongest among 18 to 24 year olds, the largest demographic of eligible voters, although the 2014 elections were characterised by a relatively low turnout among young voters.24

The Islamist Influence

The 2104 elections were marred by religious tensions and political smears, and identity-based campaigning is once again taking centre stage, to an even greater extent than previously. The increasing role of Islam in Indonesian politics was highlighted by the ouster and imprisonment of Jokowi’s friend and former deputy governor of Jakarta, governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, popularly known as Ahok, a Christian of Chinese descent. After becoming governor in 2014 when Jokowi was elected president, Ahok was seeking re-election in his own right when extreme Islamist groups accused him of blaspheming Islam during a campaign appearance in September 2016. This accusation culminated in mass rallies against him and tenuous criminal charges. He was sentenced to two years in prison for blasphemy in May 2017.

Since Jokowi himself stands for moderate Islam and a pluralist Indonesia, the same hardline Islamic leaders who brought down Ahok have also publicly demanded the president’s resignation. To deflect such opposition Jokowi chose conservative Muslim cleric Ma’ruf Amin, the long-serving chairman of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) and president of the NU, as his vice presidential candidate for the 2019 campaign. This surprising decision indicates the extent to which the administration fears the Islamist influence for Ma’ruf has been central to the recent erosion of religious freedoms in Indonesia. Under his stewardship, the MUI has denounced minority groups and Ma’ruf also played a key role in convicting Ahok after declaring that Ahok had blasphemed Islam.25 Indeed, Ma’ruf was not Jokowi’s first choice but was apparently chosen to placate Golkar, PPP and PKB, who threatened to leave the ruling coalition if other candidates were selected. At the same time, Jokowi wanted to avoid choosing a party political figure from the six coalition parties lest it provoke charges of favouring a particular party.26

|

Jokowi (left) and running mate Ma’ruf Amin during the first presidential debate. |

Thanks to his nomination of its leader as his running mate, Jokowi has won the support of many of NU’s claimed 40 million members, the world’s largest non-governmental Islamic organisation. Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s second largest Islamic organisation with a claimed 29 million members, largely supports Prabowo. The major difference between the NU and Muhammadiyah relates to their attitude towards the syncretic elements of traditional beliefs. NU promotes an interpretation of Islam that combines other cultural and religious traditions that predated the arrival of Islam in Indonesia, whereas Muhammadiyah represents a brand of Islam much closer to that of the Arabian Peninsula. In general, the NU heartland is rural Java where many forms of syncretism still exist while Muhammadiyah members tend to belong to the urban middle class. The NU and Muhammadiyah have had a long-standing rivalry, and both Islamic organisations have affiliated political parties. In the case of NU it is the PKB, a member of the ruling coalition since 2014, and for Muhammadiyah it is PAN, likewise a member of Prabowo’s coalition since 2014. Indeed, Muhammadiyah’s former leader, and Reformasi icon, Amien Rais has been a prominent critic of Jokowi from even before the 2014 presidential election campaign.

Jokowi’s decision to choose a high-profile Muslim cleric as his running mate has altered the campaign of the rival Prabowo camp. Instead of attacking Jokowi’s religious credentials, as in 2014, the opposition is instead focusing on Jokowi’s economic track record. Despite Ma’ruf’s nomination, Jokowi still represents a more moderate Islam than Prabowo although the President has disappointed many of his supporters who expected him to stand up for greater religious tolerance and pluralism during his first term. Indeed, pandering to conservative Islam is a risky strategy by Jokowi that may further consolidate Islam within the political mainstream while alienating liberal voters. Prabowo’s candidacy is supported by hardline Islamic interests who support the introduction of Islamic law in Indonesia. Prabowo won just five of Indonesia’s 34 provinces in the 2014 elections. However, West Java, Banten, West Sumatra, West Nusa Tenggara and Gorantalo are among the most conservatively Muslim and the first two, are also among the most populous. Indeed, the aforementioned victory in North Sumatra was among several successes for conservative Muslim interests in last June’s regional elections. Jokowi’s candidate Djarot Saiful Hidayat, a former Jakarta deputy governor to Ahok, was defeated in the race for the North Sumatra governorship by a smear campaign similar to that which brought down his former boss.

The Indonesian Constitution provides for religious freedom but only six religions are formally allowed to exist – Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism – all of which have long standing communities of adherents within the archipelago. However, a public opinion poll conducted by the Indonesian Survey Circle (LSI) across all 34 provinces between 28 June and 5 July 2018 revealed that 13.2% of Muslims supported converting Indonesia into an Islamic state, up from 4.6% in 2005.27 None of the mainstream Islamic organisations and political parties currently agitate for this change, although the PKS did previously stand for converting Indonesia into an Islamic state and has vocally supported the implementation of local sharia by-laws on a piecemeal basis.

Indeed, Buehler and Muhtada (2016) found that from 1998 to 2013 some 422 by-laws and regulations based on sharia had been promulgated across Indonesia, with an increase after 2005.28 These by-laws were enacted by politicians at provincial, regency and municipal levels, and it appears that their support for such by-laws was driven more by political expedience than religious zeal. Government heads from both secular and Islamic parties adopted these regulations, with 68% being implemented during their first term in office. As local government heads are limited to only two terms in office, this suggests that many local politicians lose interest in sharia by-laws when they no longer have to compete for re-election.29 In this way the introduction of competitive local elections in Indonesia has led to new openings for Islamic activists to wield influence as local politicians look for new ways to mobilise support. Aside from Aceh, the only province allowed to implement Islamic law provincewide due to its peace agreement with the central government, most sharia by-laws have been issued in the predominantly Muslim provinces of West Sumatra, West Java, East Java, South Kalimantan and South Sulawesi.

Local sharia by-laws usually only apply to Muslims, and often prohibit them from gambling and consuming alcohol.30 Many sharia by-laws also relate to Ramadan, particularly those prohibiting the sale of food and drink during the day when Muslims are supposed to fast between dawn and dusk for one month. Some of these by-laws also require Muslim women to wear headscarves when receiving local government services, and others dictate that reading the Quran in Arabic is necessary for Muslim politicians, civil servants, couples registering their marriage and students seeking entrance to university.

The traditionally liberal NU, still Indonesia’s largest Muslim organisation, admits that it has lost a lot of ground to hardline Islamists since its former leader Wahid was President (1999-2001).31 In particular, the party has been slow to react to the rise of social media, which has been expertly mobilised by smaller and more nimble radical Islamists. In addition, Saudi Arabia has invested billions of dollars in building mosques in Indonesia, and elsewhere in the region, to spread its own brand of Islam, adding to the perception that tolerant and liberal Islam is under retreat.

Conclusion

2018 was the 20th anniversary of Reformasi, the people-power movement that overthrew the Suharto dictatorship and transformed Indonesia into the world’s third largest democracy. The country has since made considerable progress in democratic consolidation, most notably in the removal of the military from politics, a blossoming of civil society, an opening up of media space and the expansion of political parties. Freedom House ranks Indonesia as the freest country in ASEAN, although it is still only considered ‘party free’ due to the lack of protections for minorities and an opaque legal system that even brought down the popular governor of Jakarta. Although such issues continue to cast doubt on the quality of Indonesia’s democracy, a relatively high voter turnout, a plethora of political parties and direct presidential elections are all cause for cautious optimism. Under direct Presidential elections first held in 2004 voting trends have gradually shifted away from dominance by established parties towards a greater emphasis on individual candidates. The incumbent President is the first to come from outside of Indonesia’s political elite. Jokowi’s meteoric rise owes much to his reputation as a task-focused, practical leader who overcame humble beginnings.

However, Indonesia is also the world’s most populous Muslim country and in the 2014 elections the conservative Islamic vote largely sided with his opponent Prabowo, who is again seeking the highest office in 2019. With campaigning already underway prior to the April presidential and parliamentary elections Jokowi has been targeting a greater share of the Islamic vote by touring the conservative Islamic strongholds he lost to Prabowo in 2014. Jokowi has also chosen conservative cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate, in order to appeal to an increasingly assertive Islamist constituency. Ma’ruf is also widely seen as a clean candidate who will not sully Jokowi’s unblemished reputation. Nevertheless, Jokowi has taken a calculated risk by cozying up to conservative Islamic elements that could potentially alienate his support base of progressive voters. Even though the post of Vice President in Indonesia is not a particularly powerful one in itself, there is always the possibility that the deputy could assume the presidency, as happened in 2001 when Vice President Megawati replaced Abdurrahman Wahid.

Since the 2014 election campaign Jokowi’s message has consistently been one of economic growth, transparent government and moderate Islam, centred around improved infrastructure and social welfare. He has delivered some ambitious reforms in expanding access to education and moving towards universal health coverage by slashing fuel subsidies, a cut long avoided by his predecessors as too politically risky. However, by re-introducing price controls for electricity and fuels, the President seems determined to prevent Prabowo attacking his record on the economy. While Jokowi has reduced poverty and unemployment, kept inflation down and given the poor greater access to healthcare and education, he has failed to deliver on his promise of 7% annual GDP growth. As such, he feels vulnerable to attacks by the opposition and is taking defensive measures to burnish his Islamic credentials, solidify his ruling coalition and delay measures that could increase the cost of living.

For his part, Prabowo has so far run a relatively subdued campaign compared to 2014 when he used smear tactics to dramatically close the gap to Jokowi in the final run up to the presidential election. Rather than focus on Jokowi’s religious credentials this time he has attacked his rival’s economic track record. Nonetheless, Prabowo has built a reputation as a strong campaigner so it is expected he will cut into Jokowi’s lead in opinion polls. Indeed, while Jokowi still enjoys a healthy advantage, some recent polls indicate Prabowo may be narrowing the gap. Like Donald Trump in the United States, Prabowo is standing as an economic nationalist and strong man, and is quietly confident that slower economic growth under Jokowi will help him win this time.

Related Issues

David Adam Stott, Indonesia’s Elections of 2014: Democratic Consolidation or Reversal?

Notes

Freedom House publishes an annual Freedom in the World report, which assesses the level of political freedoms and civil liberties in each country and assigns them a score out of 100. For 2019 Indonesia scored 62, ahead of the Philippines at 61 and Malaysia at 52 but behind East Timor which scored 70. Only Norway, Sweden and Finland scored a perfect 100.

Vedi R. Hadiz (2017), “Indonesia’s year of democratic setbacks: towards a new phase of deepening illiberalism?” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 53(3): 261-278

Marcus Mietzner (2012), “Ideology, Money and Dynastic Leadership: The Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, 1998–2012”. South East Asia Research 20(4): 511–531.

Figures from the 2010 census. Indonesian law requires that all citizens hold an identity card that identifies the holder as an adherent of one of six officially recognised religions – Islam, Protestant Christianity, Catholic Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

Marcus Mietzner (2016), “The Sukarno dynasty in Indonesia: Between institutionalisation, ideological continuity and crises of succession”. South East Asia Research 24(3): 355–368

He was accused of being a Christian of Chinese descent, rather than a Javanese Muslim, and was said to have links to Indonesia’s banned Communist Party.

Indonesia-Investments, “S&P Affirms Indonesia’s Sovereign Credit Rating at BBB-/Stable”, 5 June 2018

Antara News, “Indonesia Enters High Human Development Category: President”, Tempo.co, 16 August 2018

A similar 7% price increase for high-octane fuels used by higher income car-owners, announced at the same time, was not cancelled, however.

Saskia Schäfer (2017), “Ahmadis or Indonesians? The polarization of post-reform public debates on Islam and orthodoxy”. Critical Asian Studies 50 (1):1-21

Michael Buehler & Dani Muhtada (2016), “Democratization and the Diffusion of Shari’a Law: Comparative Insights from Indonesia.” South East Asia Research, 24(2): 261-282

In 2014, authorities in Aceh province began fully enforcing sharia on everyone, including non-Muslims.

Krithika Varagur, “Indonesia’s Moderate Islam is Slowly Crumbling”, Foreign Policy, 14 February 2017