I. Why study “dark tourism”?

A sidebar controversy to the intense debate of 2015 on how Japan’s leaders would mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II sparked my interest in the phenomenon of “dark tourism,” defined in brief as touristic interest in sites associated with death, disaster and atrocity. The practice of dark tourism, with focus mainly on the creation of dark tourist sites and the messages they convey (or fail to convey), is the concern of the three papers to follow.

The main controversy in and around Japan that year was not dark tourism, but rather, the stance the Japanese government — Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, in particular — would take in a public statement expected to be issued on the August 2015 anniversary of Japan’s surrender. Abe’s base in the Diet and beyond, and most notably in the organization known as the Japan Conference (Nippon Kaigi), was well-known for denying both the atrocities in Nanjing and the wartime government’s responsibility for recruiting, transporting and confining Korean and other women in the so-called “comfort stations.1 In line with this stance, in the run-up to the 70th anniversary, Prime Minister Abe made no secret of his desire to break with the 50th and 60th anniversary statements, notable for relatively forthright apologies for wartime aggression and the colonization of Japan’s neighbors. From late 2014 through the summer of 2015, a fraught context of anticipation and criticism from the South Korean and Chinese governments, as well as from activists and scholars in Asia and the West, put a chill on Japan’s relations with its neighbors.

In the 2015 statement Abe issued on behalf of the government on the anniversary of Japan’s surrender, his pragmatism narrowly outweighed his nationalism. He effectively finessed the apology question. By including the four key words of his predecessors’ statements of 1995 and 2005—“heartfelt apology,” “deep remorse,” “colonial rule” and “aggression”—he limited the ongoing recriminations from abroad. At the same time, his grammar offered a subtle gesture toward his nationalist base. He affirmed the apology of predecessors without apologizing in his own voice. He stressed Japan’s peaceful global posture since 1945, and sought to exempt his successors from further apology: “We must not let our children, grandchildren, and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with that war, be predestined to apologize.” He concluded that “even so, we Japanese, across generations, must squarely face the history of the past.”2

That same summer, a related controversy surrounded Japan’s petition to UNESCO to recognize a number of shipyards, iron mills, and coal mines as “World Heritage Sites,” notable as the locales for the first non-Western industrial revolution. This suggested Abe’s government was hardly facing history squarely. The South Korean government threatened to veto Japan’s application because it focused only on the Meiji era, with no mention of the brutal treatment of drafted wartime laborers transported against their will from the Asian continent to work in Japan. Eventually, the two sides agreed that coercion was part of the story. For a time, they argued over the precise wording to describe it. Would it be kyōsei rōdō (“forced labor”) or the slightly softer kyōsei sareta rōdō (“labor that was forced”)? In the end, the Japanese government acknowledged that Chinese and Korean labor “was forced” to work at these sites during the war, and the UNESCO committee voted to designate these facilities as World Heritage Sites.

|

Figure 1: Memorial for Korean laborers at the Ashio copper mine. |

The framing of this issue in terms of a Japanese-told story of “a good Meiji” versus a Korean or colonized story of a “bad empire” was almost inevitable in the context of the contested politics of history and memory in Japan, as well as around the world, that played out on the main stage in 2015. Even so, it struck me as very odd. Odd, although not surprising, firstly because the Japanese government application to UNESCO made no mention whatsoever of the difficult conditions experienced by the many thousands of Japanese men and women, including prison laborers, who had worked in these same mines and shipyards from the time of their founding. Odd, secondly, because few of those who jumped into the debate did so by questioning the “good Meiji” narrative.

Alternative ways to view the history of Japan’s industrial revolution were, after all, well known, and easily accessible. I had written at length about sites of Japan’s industrial revolution in my doctoral dissertation and first book. I had learned from earlier generations of historians in Japan of the dangerous conditions, frequent accidents, and harsh supervision endured by workers in mines in particular, but also in steel mills and shipyards. For years, I had been showing students in my courses an excerpt from a program on Meiji-era Japan, itself an hour-long segment in an eight-part documentary produced by Seattle Public Television in 1985, titled The Pacific Century. That several-minute excerpt described the dark side of Japan’s Meiji era modernization. The narrator and the camera zoom in on Hashima (or Gunkanjima: “Battleship Island”), probably the best-known of the locations proposed for World Heritage Status. The narrator calls it “a ghostly relic of the costs of Japan’s modernization.” The eminent economic historian Sumiya Mikio then elaborates:

“It was hell. This kind of mine work was true hell…Many people tried to escape but they couldn’t because it was an island. Records show that when people were caught trying to leave, they met a horrible end. Around 1890, there were newspaper accounts of miners who were murdered by their bosses when they were caught trying to escape from Battleship Island.”

Although I have no quarrel with the program’s general depiction of labor conditions in this or other mines of the time, I have not been able to find a newspaper account that matches Sumiya’s story exactly. Rather, I discovered a more complex and telling newspaper report of a murder on Battleship Island. The top story on the front page of the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun on April 17, 1897 ran the headline “Miners’ Strike and Murder.” It reported that striking miners murdered one Nakamura Jūhei, a labor boss at the mine. A subsequent article describes the context of the strike as concern for safety after a gas explosion, and a call for higher wages.3

Clearly, then, this island offers opportunities to examine histories not only of economic development and technological achievement, but also of labor exploitation and resistance by the miners. I was disappointed (if hardly astonished) that Japan’s application to UNESCO focused exclusively on achievements in technology and management, with nary a whisper about the dark side of these places during the Meiji period itself. But knowing of the Pacific Century video, I was more disappointed and more surprised that almost none of the media coverage of this 2015 controversy, and so few of the responses of scholars—two notable exceptions being the fine pieces in this journal by Takashi Miyamoto and Hiromi Mizuno in 2017—placed the undeniably atrocious conditions imposed on wartime laborers from Asia (and some Allied POWs) in a longer context of coerced labor (prison labor) or harshly exploited “free” labor in these same locations. This history reached back to the very period the government hoped to celebrate.4

These concerns most immediately led me, on the one hand, to look further into the history of labor at these UNESCO sites, and on the other hand, to examine the way these locations are being presented to the public in the years since they have been given “World Heritage” designation. But they also drew me into a broader inquiry into the global phenomenon of “dark tourism” and the academic literature that has defined the field, as well as into the varied ways in Japan that a wide array of “dark tourism” sites have been presented to the public and understood by visitors.

As a step in this inquiry, in the winter-spring semester of 2018, I taught a graduate seminar on dark tourism and public history in Japan. We began by reading some of the foundational works on these topics in English and Japanese. We then examined the 2015 controversy over the UNESCO designation of factories, shipyards, and mines founded in the Meiji era as “World Heritage Sites.” Finally, each participant chose a site of public history/memory and “dark tourism” for sustained analysis. The three articles that follow are revised versions of those seminar papers.

II. Themes in the Study of Dark Tourism and Public History5

If tourism is associated with enjoyment, “dark tourism” is on first encounter an oxymoron, linking a typically pleasurable activity to extremely unpleasant events of the past. But the practice has a long history, with imprecise origins reaching at least as far back as the beginning of modern times. Touristic visits to the Waterloo battlefield began even before the fighting had ended.6 From the 19th century to the present, leisure-time travel to sites of death and disaster has been quite common. And if one more capaciously understands dark tourism (or thanatourism) to include religious pilgrimage to sites associated with death, it has even deeper roots. It reaches back to medieval Europe and places such as Canterbury Cathedral—the site of Thomas Beckett’s assassination and the destination of the pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales—and to premodern Japan, as Sara Kang’s essay reveals.7

In contrast to touristic practice, the academic study of “dark tourism” has a precise time and place of origin: a 1996 special issue of the International Journal of Heritage Studies edited by John Lennon and Malcolm Foley. They argued in their opening editorial that “common threads could be drawn between sites and events of the last hundred years, which had either been the locations of death and disaster, or sites of interpretation of such events for visitors.” They chose the term “dark tourism” provisionally as a capacious one “encompassing the visitation to any site of this kind for remembrance, education or entertainment.” They expressed some surprise that their coinage seemed to have entered common usage.8

Over the following two decades, it has been scholars in the field of tourism and heritage studies, rather than historians, who have produced the most significant body of Anglophone scholarship on this topic. Lennon and Foley themselves followed up their edited journal issue in 2000 with a book on Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disasters.9 It ranged from an examination of Hitler’s death camps and memorial sites for the two World Wars, to a look at three locations connected to the assassination of American president John F. Kennedy, to a study of the island of Cyprus, where Turkish and Greek interpretations of the touristic value of the place differed dramatically. The chapter on Cyprus was unusual for its attention to international conflict in the interpretation of heritage sites, an aspect not foregrounded in the other cases Lennon and Foley examined.

These early studies of “dark tourism” directed attention variously to the supply and demand sides of the activity. Some primarily addressed questions of who designated “dark” places as tourist sites and why; others looked more at who visited these places and why. But they tended toward a relatively uniform understanding of these locations as unrelievedly dark places. Before long, however, scholars more usefully began to examine the complex hues of darkness, or the mixture of dark and light, that are in fact defining features of almost all the sites of dark tourism, including those in Japan and Asia. In 2003, Strange and Kempa, for example, looked at two former prisons, Alcatraz in the United States and Robben Island in South Africa, in a suggestive study of what they euphonically call “the sad and the bad and their touristic representations.” They identify an important emphasis at both places not only on the suffering of prisoners, or the magnitude of their crimes, but on admirable struggles for justice or democracy: the struggle against apartheid at Robben Island, and the 1969-1972 Native American occupation at Alcatraz.10 We will see in the essay by Jesús Solís in this special issue that Japan’s Abashiri Prison is also the site of a multi-hued history, in which emphasis on one or another shade has changed over time. In 2006, Philip Stone surveyed a wide range of works to construct what he called a “dark tourism” spectrum from light to dark, although the issue for him was less the mix in the history itself, than the mix of invitations to sober reflections versus entertainment or titillation in the way various sites were presented.11

It will not surprise readers of The Asia-Pacific Journal to learn that not only Lennon and Foley’s original work, but also the Anglophone scholarship on dark tourism was, for some time thereafter, quite Euro-America centered (the study of Robben Island in South Africa was one partial exception; this was a non-European site, but the issue was that of the legacies of European colonial rule). More recently, a fair number of studies of Asian tourist sites have appeared. Two notable works published in 2012 were an article on a North Korean resort, asking if it functions as a site of thanatourism or of peace education, and an article from the same year comparing tourism involving Hiroshima and Struthof (a German-run concentration camp in France).12 Most recently, the question of dark tourism at sites of Japan’s 2011 compound disasters—both those devastated by the tsunami itself or those connected to the nuclear meltdown—has gathered considerable attention among journalists and a small number of social scientists.13

In Japan, in addition to a spate of relatively shallow and celebratory publications on Hashima/Gunkanjima, some important work has been published in the past decade on the topic of dark tourism, in some cases using the term itself rendered in katakana as daaku tsūrizumu [ダークツーリズム.].14 Particularly rich and relevant for this set of papers is a book by Kimura Shisei, whose title can be translated as Representation and Memory of Industrial Heritage: The Politics of “Battleship Island.” Noting that media attention to industrial heritage sites has demonstrably surged in the 2010s, he thoughtfully explored the meaning of this phenomenon. His scope is both global and specific to Japan. He described the rise of movements in Europe from the late 18th century to preserve “cultural heritage,” and then examined two specific early efforts to turn coal mines in Germany and Britain into heritage sites. He cast a critical eye on the appropriation of local efforts to memorialize mines and miners in the service of national narratives of the nation state. He argued that such appropriation effaced local complexity and hid from view the negative elements of these histories. Turning to Japan, he examined the case of the Miike mine before turning to that of Hashima/Battleship Island. Of particular value and importance is his attention to what he calls “rescaling,” by which he means the way local endeavors are raised to a national scale, in this case because of the entry of an international validating body (UNESCO).

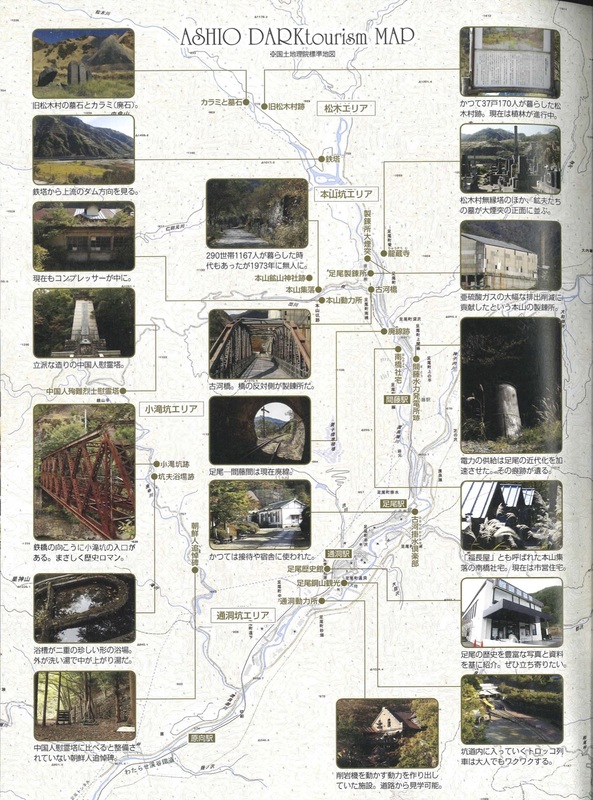

The most prolific contributor in Japanese to the study of dark tourism is Ide Akira, a scholar in the field of tourism studies at Kanazawa University. In 2016, he edited an issue of the occasionally published magazine Dark Tourism Japan (ダークツーリズム・ジャパン). It focused on “the light and shadow of industrial heritage,” including both Hashima/Battleship Island and famous sites of industrial pollution. The latter ranged from a large museum in Yokkaichi, where air pollution from oil refineries caused a huge spike in cases of asthma, to a large number of sites in the vicinity of the Ashio copper mine. Most of these focus attention on the disastrous pollution resulting from the toxic run-off from the mine, but with some effort, one can also visit memorials to conscripted wartime laborers from Korea and China. In 2018, Ide published two books on the topic. One focuses on dark tourist sites in Japan, while the other looks at tourist sites ranging from Asia to Europe to the United States, most of which have some connection to Japanese history through the history of emigration or imperialism and war.15

|

Figure 2: Dark tourism map for sites in the vicinity of the Ashio copper mine. |

Ide’s approach is that of the travel guide. He examines both the supply and demand sides of the story. His writings richly annotate a tourist itinerary with information about the various dark histories that one can experience or understand. They also offer accounts of the process by which those histories have come to be presented to visitors. Perhaps the most important conclusion to be drawn from this work is that one finds in Japan—as elsewhere—a rich variety of perspectives and strategies for marking and promoting sites of difficult history. These include thoughtful and frank presentations of histories of suffering and sacrifice, of victimization, as well of victims. This conclusion, affirmed in the papers below, is an important counterpoint to the easily made criticism of the celebratory framing of most historical sites by the national government, which evades confronting the darker sides of Japan’s past. That criticism is justified, but it is only part of the story of dark tourism in Japan.

The vigorous scholarship on dark tourism both in the Anglophone world and in Japanese writing is part of a wider upsurge of academic interest in the field of public history. This field is sufficiently well developed that Oxford University Press has published one of its characteristically broad-ranging handbooks on the topic, the 550-page Oxford Handbook of Public History.16 By my count, as many as 13 of the 28 essays touch in some measure on dark tourism, if we include multi-hued articles such as that on “Arts and Heritage in the Aftermath of Deindustrialization.” Part VI of the Handbook most directly addresses dark tourism, here termed “Difficult Public History,” with chapters on topics such as German wartime memory, slavery tourism in Ghana, and monuments in Indonesia celebrating the 1965 massacre of communists and lamenting terrorism in Bali in 2001.

The global range of the Oxford Handbook makes it clear that the study of both public history and dark tourism is evolving dynamically all around the world. As this work continues, historians and scholars of tourism need to focus more attention on at least two dimensions of these practices. First, we must examine further the way shifting global or regional contexts shape national and local understandings of “dark” events and locations. Second, we need to attend even more closely to the interplay of multiple hues, or shades of gray, in the practice of public history and the histories of publicly commemorated places. Plantation homes or slave markets invite consideration of dark histories of inhumane treatment, as well as inspiring histories of resistance or struggles for dignity and freedom. Coal mines or steel mills open windows to dark pasts of coercion and exploitation, and may also shed light on struggles for improved treatment and for the rights of working people.

III. Some themes in the study of dark tourism in Japan

The papers to follow address both these dimensions, offering considerable insight into the variety and complexity of dark tourism and public history in Japan. All three papers suggest that the curation of a site of dark tourism is inevitably contentious, generally offers multiple shades of dark and light, and very often engages global, as well as local and national, contexts. It is never possible to simply obscure a difficult history by presenting a prideful national narrative, although that is done with varying degrees of success in different places and cases. The lines of contention also vary from place to place. Certainly local, national, and international interests and contexts can be at odds with each other. But these levels can themselves be home to division and tensions. They must be examined with care in each case.

The Abashiri Prison and Museum, in Jesús Solís’ telling, offers a fine example of a local challenge by historians and citizens to a dominant narrative of the center and the state, where a relatively unified local position seems to have emerged in the 1970s. It is also a multi-hued story that has been told differently over time, with prisoners earlier having been stigmatized, but more recently recast in a sympathetic, at times heroic, light. The two memorials to Japanese settlers in Manchuria examined by Bohao Wu, one in Nagano Prefecture in Japan, the other in Heilongjiang Province in the PRC, were in some measure similar to the Abashiri case, in that one finds local interests and perspectives at odds with national ones. But the creation of both memorials also placed local actors in sharp conflict with each other, in Nagano notably over whether the term “pioneer” (kaitaku) was an appropriate one, given that its positive connotations obscured the history of the expropriation of land from Chinese farmers. The controversy over “ownership” of the Shikoku pilgrimage route is, at first glance, a story pitting local residents against each other, although there were national interests framing the issue as well. One must always, then, unpack the “local.” It is tempting to cast local perspectives in positive terms as more authentic and honest than national ones, but that oversimplifies these stories.

Global and national actors and influences enter these three histories in diverse fashion. The contemporary debate over who “owns” the Shikoku pilgrimage route (henro) offers the clearest case of a direct impact—as with the industrial heritage sights—from UNESCO. Sara Kang shows that the entry of UNESCO as a global arbiter of historical value does more than drive the narrative toward a simplified story of national pride. It leads religious devotion to be recast as a more universalized “cultural” activity, in some measure stripped of its meaning. It also pressures localities to spend scarce resources to restore an artificial “authenticity” to the pilgrimage route. The cases of the Abashiri Prison Museum or the memorials in Japan and China to emigrants to Manchuria differ from that of the Shikoku pilgrimage in that one finds no formal role played by an international body. Even so, it is clear that local and national actors are aware of a wider audience beyond the bounds of the nation.

All three cases highlight an aspect of dark tourism at the forefront of the field of tourism studies, which historians must also examine: the economic calculus, in particular the desire of local actors to create exhibits to draw visitors and generate revenue. This aspect of dark tourism might seem so obvious as to go without saying. But it plays out in interesting and different ways across these and other cases. The Abashiri Prison seems, at least in economic terms, to be the most straightforward. The prison museum is intended to bring domestic tourists to a region that could benefit greatly from their visits. The memorial in Heilongjiang may be the most complex. The context for its creation is not only the desire to sustain the economic benefits from Japanese visitors (who are not simply tourists, but often the descendants of the immigrants). It also includes the connections created by a significant flow of Chinese residents who work in Japan. The story of the Shikoku pilgrimage controversies presents another aspect: a tension between those who see themselves as guardians of a pure religious experience, and those who stress the commercial importance of the pilgrimage tour.

These papers also broaden the temporal and topical scope of histories of dark tourism and public history. The focus on wartime forced labor in the UNESCO controversy over designating shipyards, steel mills, and coal mines as World Heritage Sites, and the tensions around memorializing Japanese emigrants to Manchuria in both Nagano and Heilongjiang make it clear that issues of empire, war and its aftermath lie at the heart of the darkness of many locations of dark tourism. But closer attention to the industrial heritage sites, as well as the Abashiri Prison Museum and the Shikoku pilgrimage route, broadens the study of dark tourism to a longer modern history. The dark history of Abashiri centers squarely on treatment of prison laborers in the Meiji era (mainly the 1870s through 1890s), and the earliest efforts to mark that history came hardly a decade after deaths of the prisoners building the infamous Central Road. Controversy visited the Shikoku pilgrimage route in the Meiji period in the form of state suppression of Buddhism, and again in the interwar era in tensions setting secular and commercial interests against more purely religious understandings of the route, themselves anchored in practices reaching back centuries into the pre-modern past. In their seminal work on the topic, Lennon and Foley identify “dark tourism” as “an intimation of post-modernity.” By this, they mean that global communication technologies play key roles in creating touristic interest, that the sites of dark tourism reflect or induce anxiety over the rationality of modern progress, and that “educative elements…are accompanied by elements of commodification and a commercial ethic.”17 The controversies over the marking of dark or difficult history examined in these papers suggest instead that such post-modern elements—anxiety over the modern project, tensions between education or faith and commercialization, and the impact of a succession of new technologies—have been ever-present in the modernizing project, and remain so in our post-modern times.

Notes

The Japan Conference claims about 40,000 members nationwide, including roughly 60 percent of the members in the House of Representatives (mainly from the LDP). Its agenda includes constitutional revision and aversion to apology for Japanese colonial rule or conduct of World War II. For more on this organization, see Tawara Yoshifumi “What is the Aim of Nippon Kaigi, the Ultra-Right Organization that Supports Japan’s Abe Administration?” Translated by Asia Policy Point, Senior Fellow William Brooks and Senior Research Assistant Lu Pengqiao. Introduction by Tomomi Yamaguchi. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Volume 15, Issue 21. Number. November 01, 2017.

“Kōfu no dōmei hikō to satsugai” Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, April 17, 1897, morning edition, p. 1. “Hashima tankō no fuon,” Tokyo Asahi Shinbun, April 20, 1897, morning edition, p. 2.

Mizuno Hiromi, “Rasa Island: What Industrialization to Remember and Forget,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2 (2017. Miyamoto Takashi, “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (2017). Several other fine accounts of the 2015 controversy have appeared in The Asia-Pacific Journal with particular attention to the most famous mine, Hashima (or Gunkanjima, “Battleship Island”). William Underwood and Mark Siemons, “Island of Horror: Gunkanjima and Japan’s Quest for UNESCO World Heritage Status,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2015). Takazane Yasunori, “Should “Gunkanjima Be a World Heritage Site? The forgotten scars of Korean Forced Labor,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 13, issue 28, No. 1, July 13, 2015. David Palmer, “Gunkanjima / Battleship Island, Nagasaki: World Heritage Historical Site or Urban Ruins Tourist Attraction?” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 16, issue 1, No. 4, January 1, 2018. Understandably these articles generally focus on the responsibility for the curators of these sites to come clean on the wartime history. They do not discuss in any detail the fact of, or the relevance of, a longer dark history of labor (and an arguably “bright” history of resistance) at these places.

In preparing the summary of existing scholarship in this section, I benefited greatly from research assistance of Hirokazu Yoshie, now an Assistant Professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto.

A.V. Seaton, “War and Thanatourism: Waterloo 1815-1915,” Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1999) pp. 130-158.

A.V. Seaton, “Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism,” International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 2, No. 4 (1996) pp. 234-244.

John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, “JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with assassination,” International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 2, No. 4 (1996) pp. 198-211.

John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster (Hampshire, UK: Cengage Learning, 2010).

Carolyn Strange and Michael Kempa, “Shades of Dark Tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island,” Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2003) pp. 386-405.

Philip Stone, “A Dark Tourism Spectrum: Towards a Typology of Death and Macabre related Tourists Sites, Attractions, and Exhibitions,” Tourism, Vol. 54, No. 2 (2006) pp. 145-160.

Noureddine Selmi, et al., “To What Extent May Sites of Death be Tourism Destinations? The Cases of Hiroshima in Japan and Struthof in France,” Asian Business & Management (2012). C. K. Lee, et al., “Thanatourism or Peace Tourism: Perceived Value at a North Korean Resort from an Indigenous Perspective,” International Journal of Tourism Research (2012). See also, for examples, Lindsey Freeman, “Theme Parks and Station Plaques: Memory, Tourism and Forgetting in Post-Aum Japan,” in Death Tourism: Disaster Sites as Recreational Landscape (2014) and Eun-Jung Kang, et al., “Benefits of Visiting a ‘Dark Tourism’ Site: the Case of the Jeju April 3rd Peace Park, Korea,” Tourism Management (2012).

木村至聖、産業遺産の記憶と表象−「軍艦島」をめぐるポリティックス、京都大学学術出版(2014) 。 鈴木淳、編] 史跡で読む日本の歴史 : 近代の史跡、Vol 10, 吉川弘文館 (2010)。 井出明、編「ダークツーリズム・ジャパン」。

井出明、編、「ダークツーリズム・ジャパン」Vol. 2 (2016). 井出明、「ダークツーリズム:悲しみの記憶を巡る旅(東京:幻冬舎、2018)。井出明「ダークツーリズム拡張―近代の再構築」(東京:美術出版社、2018)。

James B. Gardner and Paula Hamilton, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Public History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).