By Tanaka Kimiko 田中喜美子 with Miriam Wattles (translator and collaborator)1

|

Tanaka Kimiko in front of the gate of Ushiku Detention Center in 2012. Photography is not allowed on the premises without special permission. |

Abstract

This long, collaboratively written article interweaves several narratives: the 25 year-long history of an activist group concerned with Ushiku Detention Center against the broader history of detention centers in Japan; description of the detention center system in Japan against an account of daily life at the Ushiku Center and visitations; and sketches from the lives of three detainees, including one man’s satirical cartoons.

Keywords: Japanese Detention Centers, Migration-Refugee Issues, Deportation Policy, History of Detention Centers in Japan

Ushiku no Kai2 celebrates twenty-five years of activism. We are a group that advocates for the human rights of the many foreign migrant detainees who, slated for deportation and filing a refusal, are sent to the East Japan Immigration Center (Ushiku Detention Center), a facility located in Ushiku, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan to await further action. Our solidarity with those detained at Ushiku began on December 24, 1993, the day the Center opened. Our small grassroots organization—established primarily to undertake visitations, to listen, and then to let the detainees’ grievances be heard—was the first to attend to the grim contradiction in the situation of detainees there. Over the years, other activist groups, lawyers, and religious ministries have joined in the struggle.3 Thanks to a growing symbiosis, the media has of late begun to draw attention to human rights abuses taking place there. These occur most egregiously in the form of regular forced deportations. All too common are cases of failing physical health from lack of proper medical care. And, increasingly lengthy detentions ensure worsening mental health.

Detainees at Ushiku are all migrant would-be permanent residents of Japan who are in custody because of their refusal to repatriate. The three reasons for detention are: 1) seeking refugee status (many detained directly from the airport upon arrival in Japan) 2) violation of residency laws (i.e. those undocumented, known as “overstayers”) 3) having served a sentence (however short) for a crime committed in Japan. As will be detailed below, none of these reasons for being detained at Ushiku bode well for the detainees’ eventual recognition or reinstatement of legal residency in Japan.

Recent developments at the Ushiku Detention Center are part of a much longer national history. Unceasing exploitation of workers from outside Japan is intertwined with the way detention centers were set up to deport foreign workers in order to prevent their permanent settlement and path to citizenship in Japan.

|

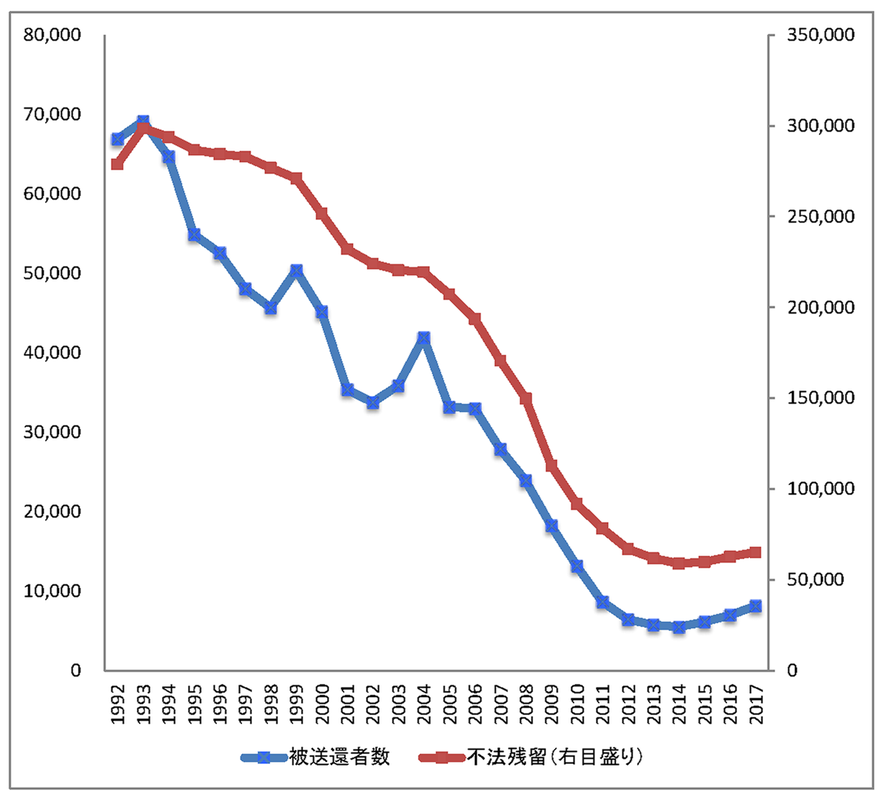

Graph of undocumented migrants (red line with numbers on right) and deportations (blue line with numbers on left) in Japan from 1992 to 2017; constructed from Ministry of Justice Statistics by Oh Tae-sung. |

When the Ushiku Detention Center was completed in 1993, Japan had reached a peak number of 298,646 undocumented foreigners; of these 70,404 were deported. Recent numbers are not nearly as high as this (in 2017 there were 66,498 undocumented foreigners, with 13,686 deported). However, the numbers are slowly creeping upwards (see graph).4 In recent years, the numbers concurrently held at Ushiku Detention Center ranged between 320 and 350 detainees. The detainee population slowly changes with arrivals of new detainees and departures from either voluntary or forced deportation, or from releases of those paroled with a “karihōmen” or “provisional release.” The latter is the best of the unfortunate possibilities allowed.

Ushiku is just one of a network of detention facilities spread across Japan, yet it is significant for containing the central office of the Immigration Bureau of the Justice Ministry. In recent years, the number of detainees held concurrently in custody in detention centers in all of Japan hovers around 1,400.5 Yet, worryingly, since some facilities are presently not in use, the total capacity is almost 2.5 times larger.

The fatality rate at Ushiku is indicative of the dire reality of detention: in 2010 there were two suicides; in 2014 two deaths from illness; and in 2017, another death from illness. This past year, on April 13, 2018, a man from India committed suicide the day after his request for “provisional release” was denied.6 Afterwards, there were a number of suicide attempts and incidents of self-harm that center administrators claimed “bore no relation” to the suicide. In response, detainees started a major hunger strike and other forms of resistance. Yet even these stark facts only hint at the weight of the daily pressures and overall anxiety that cause every detainee to fear for the worst—although individual expressions of their apprehension differ.

|

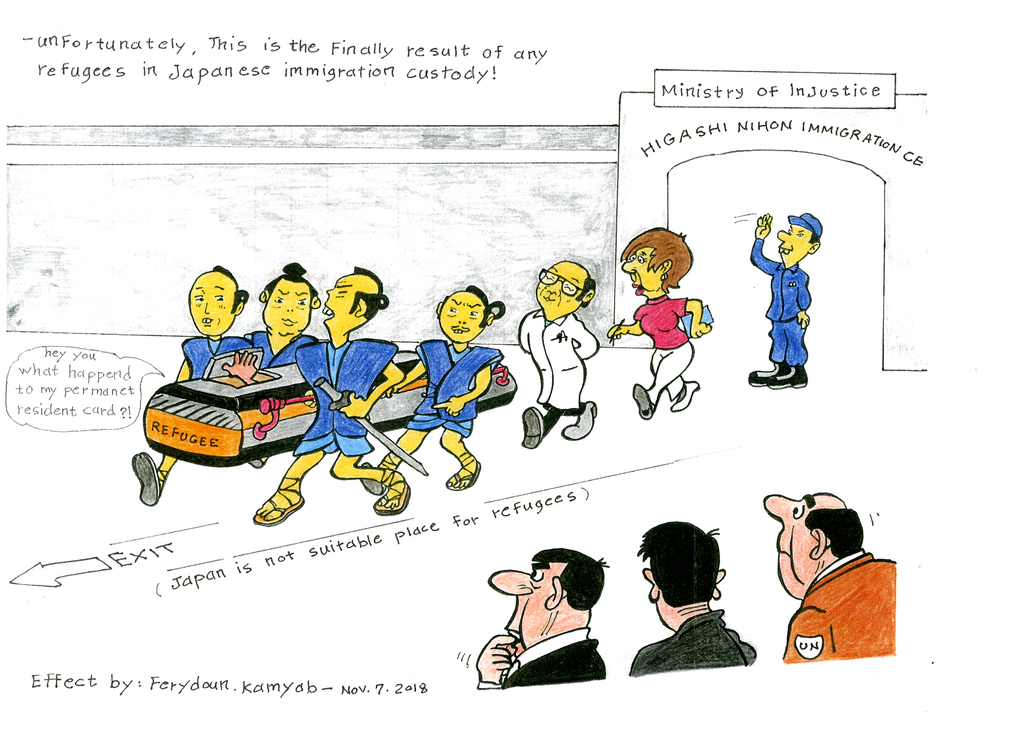

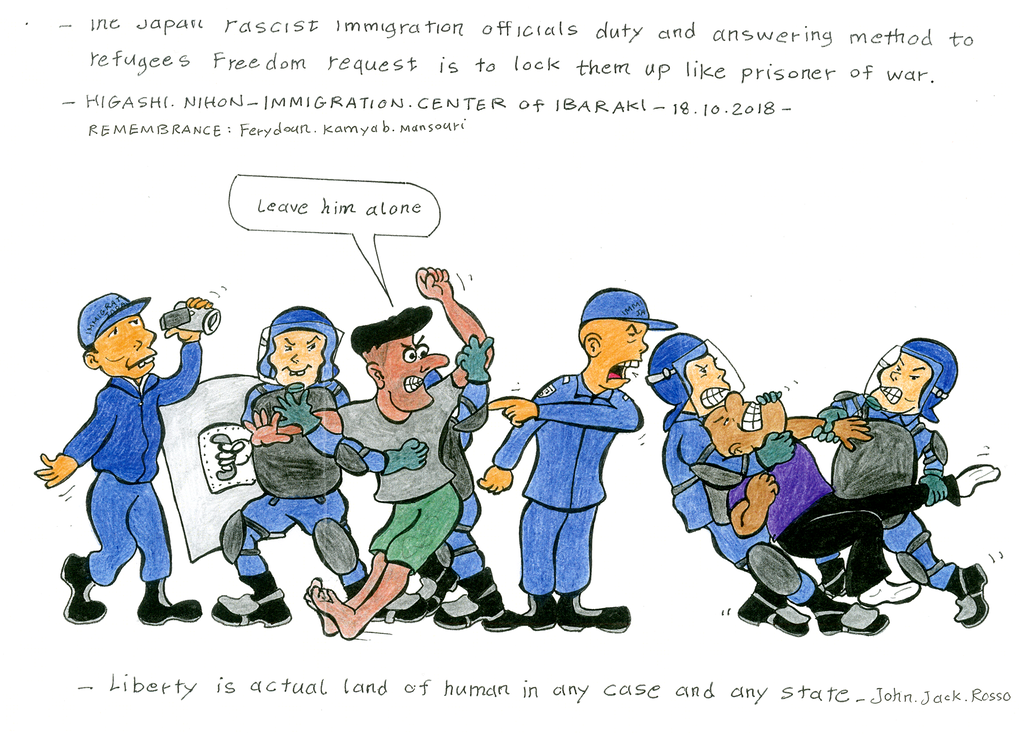

The artist of this dark, satirically humorous cartoon, FKM, was detained at the time he drew it, and knew the man who had committed suicide seven months earlier. Inadequate medication for FKM’s severe diabetic condition had led to several hospitalizations and confinement to a wheelchair. His rancor at the immigration authorities is expressed through the racial stereotype of yellow-skinned and samurai (= feudal) Japanese. |

As indicated, all those detained at Ushiku—whether undocumented, seeking refugee status, or past offenders of Japanese law—face a dilemma. They are in the crosshairs of recent policy and practice. Those who are seeking refugee status confront the fact that Japan’s rate of refugee acceptance is among the lowest in the developed world (.1% in 2017). Undocumented or “overstayers” face the lack of a path to long-term residence. Going against those who have already served their prison sentence for a criminal offense, however minor, is increasing reluctance on the part of the Justice Ministry to be lenient. Namely, the “special resident status,” which used to allow clemency due to personal circumstances is ever more elusive.7 (In the recent past, if an offender’s family was Japanese or resided in Japan, this “special resident status” was more easily attained and retained.)8

The unsettled state of mind of the detainees—underpinned by the harsh reality of not being welcome—is severely compounded by a capriciousness of process hard to comprehend. In a way, it is a double curse. First and foremost is the arbitrary nature of the immigration decision process, often expressed by the phrase “case by case.” Fairness depends too much on the leniency of the current regime or the bureaucrat reviewing one’s case. When the sought-for karihōmen is denied, the reason on the form that comes back is inevitably “no reason” (“riyū nashi”). If the detainee does not voluntarily repatriate (or is not forcefully deported), seemingly endless reapplications must be made.9 Detainees most often say that the worst thing about being held at Ushiku is this complete lack of transparency on top of the impossibility of knowing how long they are to be detained. This arbitrariness fuels their acrimony.

The second part of the curse (at least in present practice) is disguised as the reward of karihōmen, the “provisional release.” Many seeking refugee status as well as “overstayers” do get provisional release eventually. Yet what should be provisional, a temporary state that can be improved with good behavior, has turned into a permanent purgatory where there is no redemption. Under its conditions, freedoms that most of us take for granted are impossible. Karihōmen can be renewed; indeed, it is not unusual for some to have renewed it for fifteen years or more, requiring a visit to the immigration center every two months for renewal.

The real snag lies in the near impossibility of complying with the conditions of the provisional release. By its terms, one is left without a legitimate identity. One cannot get a phone, open a bank (or post office) account, rent a house, rent videos or do many things most of us take for granted in daily life. Most seriously, one is not allowed to work—and how can one live without supporting oneself? Nor is one allowed to leave one’s prefecture or city of residence without specific permission. Because of the near impossibility of compliance with these conditions, many are periodically picked up for infringements, and forced to live their lives rotating in and out of the detention centers. One person living in permanent karihōmen called it a “prison without bars.”10 Moreover, the fact that officials often look the other way from the widespread shady companies (“yami kigyō”) that hire illegal immigrants makes it all the more unfair to those who are caught.

It might be argued that Japan is only maintaining longstanding barriers to the long-term settlement of immigrants.11 However, the case might be made that Japan’s present detention and deportation policy follows other nations in the global north that have increasingly criminalized refugees and undocumented persons since the 1980s.12 Any lip service on the part of the Immigration Bureau that boasts of Japan’s recognition of refugees, not to mention the implementation of new foreign trainee programs under the Abe regime, should be treated with skepticism.13

Our genesis

Our group originated in opposition to the construction of the Ushiku Detention Center. We emerged out of other initiatives that began in 1992 to defend the rights of the many foreigners living in Japan who had been arrested for overstaying their visas. I was part of a group in the relatively nearby Tsuchiura area of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, named “In Solidarity with the Asian Day Laborers.” Our members included third generation ethnic Korean students at Tsukuba University; we held study workshops to look into such issues as “Detention Centers in Japanese History,” and focused in particular on the Ōmura Detention Center in Nagasaki where numerous abuses had occurred in the past. Groups with like mind joined forces to oppose the construction of this new detention facility at nearby Ushiku, which was designed for the forced deportation of foreigners. We passed out flyers and held demonstrations opposing the planned facility.

Regrettably, local resistance proved insufficient. This could have been because officials had learned to not build on expropriated land as they had in the case of Narita Airport—the government owned this land; it was originally the proving ground of the Ibaraki Agricultural Academy, an oblique name for one of the Juvenile Correction Centers run by the Ministry of Justice. Despite our efforts, the Center opened as planned on Christmas Eve of 1993.

|

Aerial photo of Ushiku Detention Center (from Google maps). The Center is located 80-100 km. from Shinagawa (Tokyo), depending on the route. |

The center’s location in Kuno-cho of Ushiku city in Ibaraki Prefecture, at least two hours from Tokyo, could hardly have been less accessible. At the time of its opening, there was only one bus from Ushiku Station a day, in the morning. The cost of a taxi from the station was prohibitive, about 2,700 yen one-way. Because of this, the original seed that grew into Ushiku no Kai was my providing transportation to a long-term supporter of detainees coming all the way from Tokyo to continue his visitation work at Ushiku. In order to ease his financial burden, on my day off from work, I drove 45 minutes from my home in Tsukuba to taxi him to and from the Ushiku Detention Center. When, after just a few months, he could not continue due to illness, I took over the reins of his mission.

A few other local activists immediately joined me, some of whom I had known from previous activist groups. Within a few months, we were visiting the detainees at Ushiku weekly, and holding meetings monthly.

No Longer Welcome

When I first began visiting detainees, in the early 1990s, those sent there to be deported were mainly Iranian and Filipino. In the 1980s, the economic bubble years of Japan, those populations were two among those of other nations of the Global South that had undergone political and economic turmoil, resulting in many people leaving their country as migrant refugees.14 Japan’s economic success was a draw, having in the 1960s and 1970s reached the prosperity of other highly developed countries. In 1995, I was astonished to hear from an Iranian that through the TV program “Oshin” (shown in Iran as well as SE Asia), he thought that all Japanese women were like Oshin. Ironically, her path from rags to riches was blocked to him as a migrant refugee. After a time, Japan no longer recognized the continued need of such migrants for work, so many lost their legal status of residence and overstayed their visas.

The political and economic unrest following the Iranian Revolution of February 1979, and the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88, sent refugees fleeing out of Iran. Many made Japan their destination since at the time Iranians could come without a visa and were allowed to work. When diplomatic relations between the countries changed, and visas became necessary from April 1991, many were rounded up for deportation. Well publicized swoops picked up the Iranians who regularly gathered in Yoyogi Park or Ueno Park in Tokyo, following complaints that they were selling things illicitly.15 Likewise, many thousands of Filipinos migrated to Japan because of political repression and economic hardship. There were many tragic cases of Filipinas who came on entertainment visas, got swept into the flesh trade, and ended up in prostitution rings that involved human trafficking. These women were also subject to deportation.

From a cold economic perspective, the mass deportation of these migrants suddenly deemed illegal was a readjustment following the burst of Japan’s economic bubble. Yet in essence, it was a continuation of past prohibitions that disallowed the settlement of foreign workers. This callous disregard of those trying to put down roots has continued. Some of the migrants who during this time married Japanese—one of the few loopholes that formerly ensured legal residency—are now detained at Ushiku for what many from other nations would consider minor infringements of the law (such as traffic accidents).16

At first “Temporary”

When Ushiku Detention Center opened in 1993, the facility was temporary. According to an official brochure of the time, “East Japan Immigration Center is a temporary facility set up for official immigration implementation, to forcibly deport foreigners who have gone against immigration law in matters of labor, or those unlawful in matters concerning their residence in Japan. This is a temporary facility to be used until those foreigners needing to return to their countries are repatriated.”17 Yet, a pamphlet produced in 2004 states, “East Japan Detention Center is a facility designed to detain foreigners until they are returned to their country.” Thus eleven years later, after a new wing had more than doubled their capacity, the “temporary” provision that was in the original pamphlet was omitted This simple omission marks a complete disregard for the suffering of detainees detained indefinitely for refusing to return to their homeland – whether in order to maintain family connections to Japan, for fear of their lives if they return or otherwise.

This shift in stated purpose is reflective of the constant shifting of usage among Japan’s large network of detention facilities, comprised now of two main detention centers and fifteen regional bureaus. The East Japan Immigration Center in Ushiku was established in 1993 as one of three main detention centers (and the administrative unit of the Immigration Bureau was then transferred there). Ōmura Detention Center, which opened early in the postwar period, remains another main detention center. In 2015, the third main center, West Japan Immigration Center (located in Osaka) closed to leave just two main centers. The operations of the branch facilities are not insignificant, although easily overlooked since they are rarely officially mentioned. In 1999, the Narita bureau was opened as part of the Denial of Landing Facility with a capacity of 449 detainees (now its capacity as a differently configured facility is 128). Of the fourteen other immigration branch facilities, many see little or no use.18 However, recent numbers of detainees held at the three regional bureaus of Nagoya (215), Yokohama (140) and Osaka (75) are considerable. While the number held at the Ōmura Center (98) is creeping up, those held in custody at the new high rise facility at the Tokyo Regional Bureau, located near Shinagawa (525) greatly exceed the number held at Ushiku (340).19 In 2015, the female deportees who until then had been detained at Ushiku were sent to Shinagawa.

Postwar Japanese Immigration Policy

The long, complicated history of detention centers in Japan is closely tied to the question of who is allowed residence and Japanese citizenship. Behind the euphemistic historical labels, we see the bitter legacy that arose from the aftermath of coerced labor under Japanese imperialism. From the time of the 1875 Treaty of Taipei through to the end of the war, Japan oppressed other nations in Asia through colonization—by means of such things as the forced changing of names, forced conscription, forced labor, and forced sexual services for Japanese soldiers (the “comfort women”).20 Upon Japan’s defeat on August 15th, 1945, 2,100,000 people from Korea and Taiwan were living in Japan.21 Although the vast majority repatriated, some 700,000 remained in Japan.22

Japan as the suzerain state needed to determine the status of these former colonial subjects, who had been citizens, albeit second-class, of Japan. On May 2, 1947, the day before the present constitution took effect, one of the last imperial decrees of the emperor involved the registration of foreigners.23 Consequently, on April 28, 1952, with the San Francisco Accord, all remaining resident Koreans, Taiwanese, and Chinese were stripped of their Japanese citizenship, to become known as “Zainichi.” This disenfranchisement weakened the political force of the Zainichi workers who had been a strong faction in the fierce labor union struggles of the early occupation years. Strong echoes can be found in the continuing struggles of unskilled migrant workers.24 More generally, policies towards Zainichi (the word used mainly for resident Koreans) might be thought to have set an uneasy precedent that all but disallowed easy integration and naturalization of foreigners.25

Tough postwar Japanese detention and deportation policies were influenced by a coordinated American presence in both occupied South Korea (1945-48) and occupied Japan (1945-52) while being impacted by the existence of such international organizations as the Red Cross.26 Yet within this matrix of forces, the resistance of detainees and supporters in the newly constituted Ōmura Detention Center near the city of Nagasaki played a strong part.

Ōmura Detention Center during and after the Korean War

Starting November 1, 1951, the Immigration Authority began to detain Korean deportees at Ōmura Detention Center, taking over this function from nearby Hario (that had been run by SCAP).27 The administrative predecessor of Ushiku Center, the Yokohama Detention Center, had already opened on April 1, 1951, but it was “set up to intern other (mostly European and Chinese) detainees.”28 That year coincided with a significant change in border controls in the way authority was cast. When it moved to its Yokohama center on August 1, 1952, immigration control shifted from being under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to being a centralized “Immigration Bureau” under the Ministry of Justice. Since the Ministry of Justice controls all of the police forces in Japan, it has emphasized the punitive.29

This was in the midst of the Korean War that lasted from June 25, 1950 until July 27, 1953. For the Japanese economy this international conflict spurred the postwar recovery under the “emergency demand” procurement of munitions and materials that Japanese producers could supply. Korea suffered chaos, destruction, and tremendous loss of life as one in five Koreans died during the war. Afterwards, many in the ROK (South Korea) faced severe political persecution under anti-communist dictator Syngman Rhee. Consequently many of those who had repatriated to South Korea after Japan’s defeat sought to return to Japan.30 They were not welcomed. Japan cracked down on these undocumented “secret boat people” or “stowaways.”31 Many were arrested to be sent back. At their moment of forced repatriation, deportees who had been incarcerated at the Ōmura Detention Center protested with “No to Repatriation!” (Sōkan hantai!). They held sit-ins and hunger strikes. When this escalated to a breakout and riot in November, 1952, 2,000 armed guards were sent in. Seven lives were lost in this violent suppression.32

|

Crowded conditions at Omura in the mid 1950s. Women and children were separated from men. Source |

As warfare in Korea was succeeded by the onset of the Cold War, detainees increasingly become political pawns between Japan and the two Koreas— ROK (Republic of Korea, South Korea) and DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or North Korea). From June of 1954 to April of 1956 (when deportations were halted because the Rhee regime refused to accept them), detainees had to survive under appalling conditions; 1,500 to 1,800 detainees were crowded into a facility that had a capacity of just 1,000. Inside was a microcosm of the identity politics of Zainichi in Japan. Ōmura leaders of associations of Zainichi Koreans oscillated the thinking of detainees towards the North or the South.33 Outside support allowed detainees to contribute to journals and even create their own internal publication.34 In November of 1955, 47 signed their name in blood demanding to decide their own destination and be repatriated to DPRK; in 1958, 70 went on a hunger strike for the same reason. With this pressure from inside Ōmura as a trigger, an unlikely alliance between the DPRK and their Zainichi allies, the Kishi regime, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) devised a covert plan that resulted in 80,000 of the poorest (and most politically involved) “voluntarily” repatriated to the DPRK from Niigata Port from the end of 1959 to the early 60s.35 Meanwhile, a Hamamatsu facility that had been set up in 1954 to take the overflow of Zainichi and also intern Chinese as well was the site of a riot triggered by three Chinese who refused to be repatriated.36

From the 1960s until about 2000, as Niigata took on the burden of Korean repatriation, the Ōmura Center became almost completely dormant, holding little more than 20 to 30 at a time, despite a capacity of 800. However, following the West Japan Immigration Center’s closure in 2015, the use of Ōmura Detention Center is again rising, holding many nationalities. Cases of inhumane treatment and violations of human rights have been reported there, along with similar grievances at Ushiku and branch facilities.

Japan’s Reticence to Recognize Refugees

Japan has the lowest rate of acceptance of refugees among developed nations: in 2017, out of 19,629 people applying for asylum, only 20 were approved. According to the Global Trends of UNHCR 2017, the other countries that have “low protection rates” (under 10%) include Gabon, Israel, Pakistan, and Republic of Korea, but Japan “stands out as having a particularly low TPA [Total Protection Rate]… of under 1%.”37 With the worsening of political crises, civil unrest, wars, and the widening gap between the very wealthy and poor in many nations in the world, the number of those who are displaced from their homelands is increasing exponentially, such that one person gets displaced every 2 seconds, coming to 1 in 110 people in the world. The displaced population in the world now approximates the population of France.38

It wasn’t until 1981 that Japan finally ratified the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees Act. By the next year, it was put into force. Many refugees, displaced during the Vietnam and Cambodian wars, were arriving in Japan as boat people. At first refusing to accept them, Japan then responded to severe criticism from abroad and initiated the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Law. The result was an uneasy merger of immigration and asylum policies followed by increasing control over every action and every movement of foreigners in Japan.

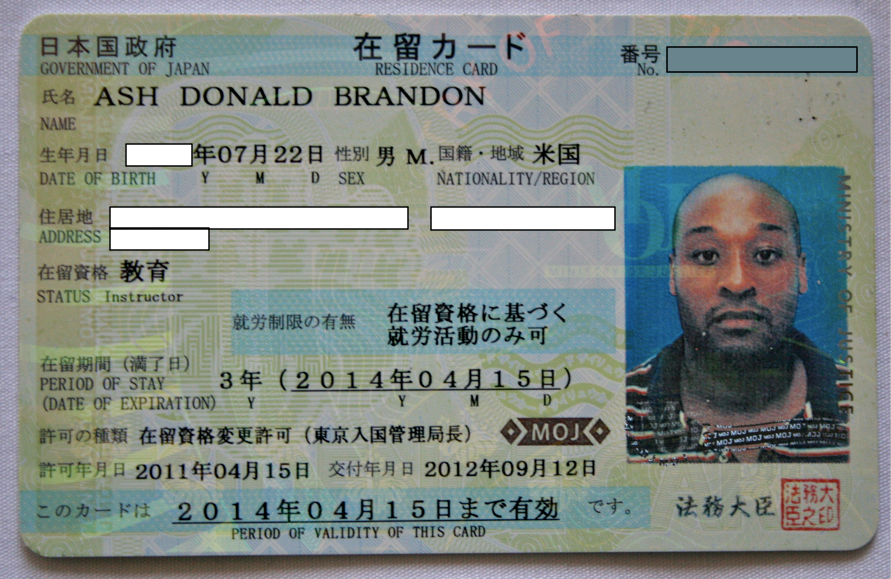

On July 15, 2009, Japan abolished the alien registration law, and in July 2012, the resident card system was put into practice. As is true in many other nations, the Ministry of Justice now exercises integrated management of data on each foreign resident with medium and long-term visas. (This is aside from the special permanent resident on temporary release and those overstaying their visas.)

|

Residence Card required since 2012. Soruce |

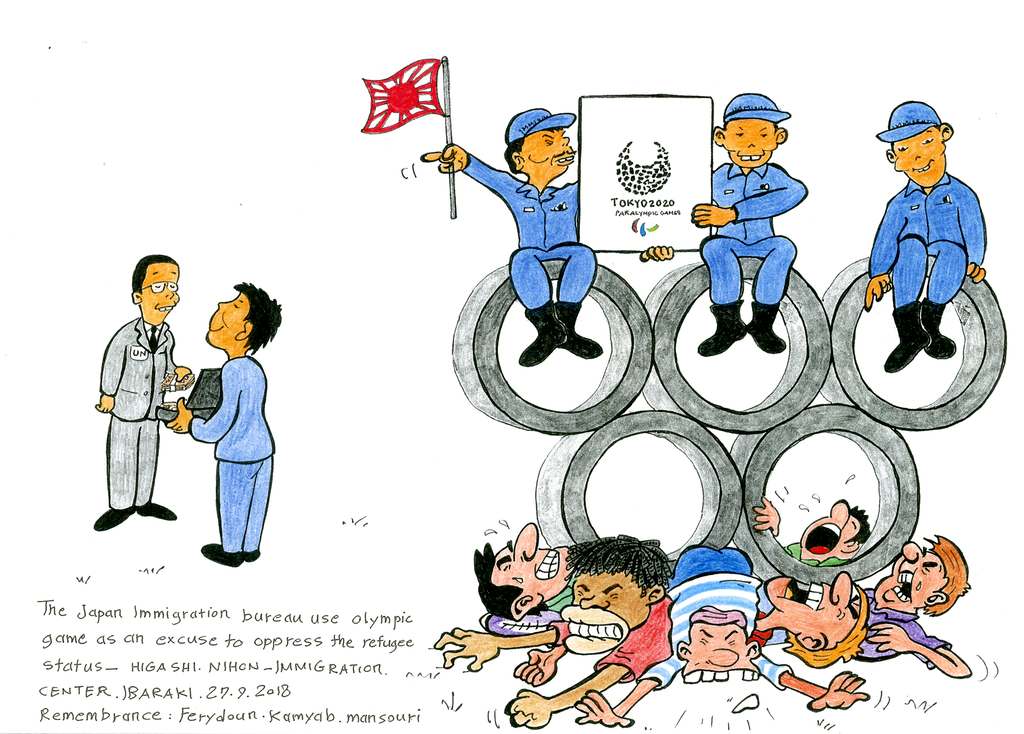

Rapidly rising numbers of those seeking asylum from around the world in recent years have led to much stricter controls. In 2017 more than 17,000 applied for refugee status leading to an almost complete shutdown of the asylum provision by January 2018.39 Subsequently there has been a massive tightening of controls prior to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics is related. Some speculate that the present toughness is meant to get the word out to dissuade would-be migrants from coming when the Olympics inevitably opens the floodgates to visitors. What is clear is that there is no sign of any loosening of border controls in the near future.

|

Fery has done several variations of this cartoon, portraying how the Japanese Immigration Bureau is using the 2020 Olympics as “an excuse to oppress the refugees” (as this one states). |

The 2017 Immigration Control pamphlet points out that between 2010 and 2017, 123 people from Myanmar received refugee status. Yet none of the Kurds, a persecuted minority left without a country who have been living in Japan for some years, have been granted refugee status and so most must constantly renew their karihōmen and risk being arrested for working.40 For these and other persecuted populations, repatriation is not an option. As one Iranian detainee put it, a mere signature of an immigration official has the power to forcefully deport someone and put one in danger of losing one’s life.41 As anyone reading news in other parts of the world is aware, forced deportations and harsh refugee policies are certainly not unique to Japan, but to those with their lives in limbo, Japan becomes their only target of blame.42

After repeated failures to attain residence status and left at best with a “temporary release” in Japan, many would-be refugees yearn for asylum in a third country. Up until about four years ago, it seemed possible for that rare miracle to happen: a handful of lucky individuals that I know about were sponsored by support groups and family and succeeded in attaining refugee status in such countries as Canada and New Zealand. This, I heard from a reliable source, was related to the “Mandate Refugee” system determined by the UNHCR.43 But, allegedly, after complaints from the countries concerned—who made the claim that since the GDP of Japan is higher than their own, Japan should do its part in accepting refugees—this possibility seems to have vanished. Some attribute the lack of UN pressure to the fact that Japan is among the largest donors to the UNHCR to help the situation in other countries (as in the cartoon above).

Ushiku no Kai

Over the years, our organization has grown to a membership of about 80. We are a coalition of individuals whose unifying principle is support for deportees in detention. Unlike many other groups, we do not adhere to any one political or religious agenda. The basis of our practice is carrying out visitations with detainees. Key to being allowed to visit is familiarity with the current list of detainees (including name, country, and block). Our group holds an updated detainee list, and we are glad to share names with any party interested in providing support. After being introduced to detainees, a member naturally develops his or her own list of detainees to support, depending on his or her individual interests, experience, and language skills.

Each member undertakes visitations when and as often as their schedule allows—although we encourage people to come on Wednesdays when we meet and exchange news. Some come more often to see many, others come irregularly to support a few. Unlike most other groups, we have no rules on how to support the detainees or proscriptions concerning material gifts for the detainees. As well as facilitating visitations of interested parties, we share detainees’ names with university support groups. We have a branch group that visits detainees at the Shinagawa branch office on Fridays.

|

The demonstration outside Ushiku Center on Refugee Day, May 20, 2018 can be viewed on YouTube |

|

Summer Barbecue 2018 |

Although technically a Non Governmental Organization, we belie the typical image of a large NGO and proudly manage without paid staff, office, or administration. Every month I write and send out a newsletter with news about changes in the detainees’ conditions. We began our website in 2007. Our regular monthly meetings are held in the free municipal facilities of Tsukuba city.

|

Visitors are welcome at our monthly meetings at the Tsukuba civic center on the fourth Saturday of each month from 14:30. |

Our yearly fee of 2,000 yen for individuals goes entirely for the postage and supplies of the monthly newsletter. We demonstrate outside the facility each year on Refugee Day and hold a summer barbeque to which ex-detainees come. At the end of each year we hold an Annual Meeting to inform less regular members, the public, and the press about our activities. Lately, our efforts grew to extend the support of Kurds resident in Japan with educational activities and other services. In recent years, Kurdish children have performed at our end of year meeting.

Having taken on the role of communicating the grievances of the detainees, I now serve as the spokesperson for the detainees and regularly visit the offices on the second floor of the East Japan Detention Center to talk to Immigration Bureau Officials, relaying the detainees’ petitions and demands. I also post detainees’ letters and petitions on our website.

Over the years, our networking with lawyers and the press has become robust. Gradually, more lawyers have come to provide pro bono services.44 The Tokyo Bar Association awarded us the Human Rights Prize in 2011. My service as a liaison for the press has also borne fruit. I have twice held press conferences at the Ibaraki Press Club (in Mito) to receive coverage from the local news (in which I am often quoted). This has sometimes led to national headlines. I have shown Yomiuri, Mainichi, and Asahi newspaper and Kyōdo News Wire Service reporters around, answering their questions. BBC has done a documentary. OurPlanet TV covers Ushiku regularly and (as of December 2018) Nihon TV is seeking permission to shoot.

Sketch of a Wednesday visit

At 8:30 a.m., the window in the waiting room opens and you can take a numbered ticket. Arriving by this time ensures you first entry into the visitation (menkai) cubicle. The procedure involves first submitting one form to the official at the window for each detainee you are requesting to visit. As well as writing your name, address (visa information if not Japanese), you must also include the detainee’s full name, nationality, and block number. You can see two detainees at a time, but only if they are from the same block. Called to the window, you must submit your photo ID (passport or residence card if not Japanese). Always officious, the staff is on the whole solicitous and patient, only rarely showing irritation at a visitor who is not following the rules.

At 9 a.m., the visitations begin. On the way to the visiting cubicle, the visitor must stow away recording devices, cell phones, and cameras in lockers on one side of the room. You pass through the metal surveillance device that was installed in May 2018. There are seven visitor chambers in a row down a long hall, two of them are reserved for lawyers (they may be used if there are no lawyers present). Each is just large enough to fit three visitors. Inside, a plexiglass divide separates visitors from detainees. A narrow surface at the bottom of the divide makes it just possible to write. Some of the booths have graffiti.

|

A generic view of the menkai (visitation) room provided by the Immigration Bureau. Source. |

A visit is limited to thirty minutes; I usually see two people at one time. Only after returning to the waiting room can you request the next meeting. During the morning, with luck (fewer people requesting visits) it is possible to have three visitations, seeing up to six people. After lunch break that lasts from noon to 1 pm, the visitations begin again. During the afternoon, it is possible to have two to four more rounds, depending on how crowded it is. The time to request visitations ends at 4 pm.

In between visitations, during the often long waiting times in the waiting room, we generally occupy our time with preparations, reading, talking to members of other support groups or among ourselves. If a family is visiting, sometimes there are little children, who play with the stuffed animals provided on a shelf in the corner where yellow and green squares fit together to form a foam mat. There is an automatic drink machine outside in the hallway.

Until recently, there was a cafeteria where visitors could join the staff to enjoy lunch together inexpensively. (Usually rather empty, during training season for new Justice Ministry employees, it was packed.) The cooks used to work hard to create delicious food. But at the beginning of December, 2018 it was closed suddenly, inexplicably, with no word about whether it is to reopen. We now bring food to eat in the waiting room.

In my case, I see detainees from early morning to the end of the day. I mainly see Iranians and the Kurds who have Turkish citizenship. (Of course, I see people of other nationalities, but it is impossible to see and support a large number.) The main language of the visitation for those in our group is Japanese. (A few in our group use English and Spanish as well.) Many of the detainees can converse easily in Japanese. This goes without saying for those who have lived in Japan for more than half of their lives as some have; but even those picked up straight from Narita airport and transported to Ushiku for detention can usually speak broken Japanese after three months, and some become fluent after six months.

What do we talk about? “Any changes?” “How are things?” From questions about health, we go on to discuss all kinds of topics. News is our main currency. There are reports to exchange: who has just gotten temporary release (or, more often, been denied) and information from what the lawyers have told me, such as a recent amount of bond for karihōmen. Sometimes, detainees report some unfortunate situation that has left them shaken: an injury that has not been attended to quickly, a notice of someone’s imminent deportation, the sorry sight of another forced deportation. As I take mental notes of what needs to be checked or communicated further, thirty minutes passes quickly.

Life in Ushiku Detention Center

Incarceration is a sure way to destroy the human spirit. At present, the holding cells are locked up for eighteen hours and ten minutes a day—from 4:30 pm to 9:20 am and 11:40 to 1 pm. Detainees must eat their cold bentō in their holding cells. TV is allowed from 7 am to 10 pm. They have just forty minutes a day to be under the sky during exercise time (if it is not raining). Cells vary in size and type, but are typically ten tatami mats for five people. Guards pass by the windows to the hallway; in most rooms it is impossible to see through to the outside.

|

In the old wing, 4-5 detainees are confined for much of the day within a tatami-style cells such as this, whereas in the newer wing detainees are held in cells with bunks. |

Sharing the cell are people of different nationalities, ethnicities, religions, languages, and customs, everyone with a different reason for being locked up. Although inevitably some bonding occurs between cellmates, the fact that almost all take sleeping pills to get through the night and the prevalence of stomach ailments attest to the incredible tension that builds up. When they are injured or sick, after not being attended to very quickly, they have to go to an outside hospital in handcuffs. (Why are those who are seeking refugee status handcuffed in a hospital? I never want to have to accompany anyone to the hospital again!)

More than anything, through visitations, our group, along with other volunteer groups and ministries, provides a desperately needed window of contact with the outside world. Although the plexiglass barrier in the visiting cubicle prohibits easy conversation (the sound travelling through a perforated metal bar at its bottom), it is face to face and in real time. Inside the Center, neither cell phones nor internet access are allowed. Unless given newspapers, books, or magazines, the TVs in each cell provide the detainees’ only news and entertainment. There are payphones to make calls out, but they require inordinately expensive phone cards. Other than visitations, the most certain means of communication is a letter through the post.45 Not easily reached by public transportation or even by car, to be cut off in these ways means that many of the detainees who have refused deportation because they have family in Japan eventually lose all interaction with their wives, children and other family members.

Dreams Crushed

In what circumstances are individuals sent to Ushiku? For example, one Kurd married to a Japanese woman was put into Shinagawa just a week after registering his marriage in 2015. Before marrying, he had been living together with her and he considered her seven-year-old child from a previous relationship his own. He brought a letter he had gotten from her to the visitation cubicle to show me. He came to Japan in 2011 at 16 because his aunt and cousins live here. But within five minutes of the time he applied for refugee status at Narita airport, they served him deportation papers. When he refused to be deported, they gave him a temporary release. Afterwards, he lived in Saitama. Six months later he was scheduled for an interview that could give him a chance of receiving asylum, but with only two months to go until his interview he did not get an extension of his temporary release. So, from August of 2015 to May of 2016, he was held in Shinagawa, before being granted karihōmen again. Again, however, he could not get an extension of his temporary release, so he was put in Shinagawa again, and soon transferred to Ushiku. He was then held for one year and five months. All in all, from age 20 to 23 he passed his birthday three times while detained.

He related to me what he told his daughter who came to visit for her birthday, “I really want to spend your next birthday with you at home. I wonder if I can…” His daughter replied, “So as to not forget you, I always watch the video where we went to the pool and bath together.”

Many of this young man’s dreams were broken, over and over, because of his detention. He told me that while in Turkey he thought Japan was “a really great place” from watching movies and TV programs. Yet, he prefers the Ushiku penal environment to even the thought of returning to the perilous environment in his homeland. About three months ago, as a consequence of the incredible strain he is under, this young man attempted suicide by swallowing shampoo. When I saw him two days later, he looked like a different person, but by now he has returned to himself and smiles again.

Increasingly Bad

In 2015, the Justice Ministry circulated a notice calling for “caution in our policy for implementing provisional release,” and in January 2018, they issued a notice, “Rethinking the policies for proper recognition of refugee status.” Many are suffering as a result of this “rethinking.”

Just as the chances of getting temporary release for those refusing to be deported grow slim, the length of detentions is growing longer. It is not unusual for someone to be held for two or three years before they gaining provisional release, agree to repatriate, or are forcibly deported. Recently someone was in custody for eight years before he was deported. Aside from the necessity of making multiple applications for provisional release, the time taken to decide whether or not to grant it is growing. While it used to take about 80 days before the decision was made, I hear that now it can be up to 100 days. And after any reapplication, it takes more than three months. Many have had to reapply many times over the years.

As I was writing this, I got a call from Ushiku, “Tanaka-san, I was denied karihōmen for the thirteenth time. It’s been three years and a month. Today I’m dizzy and can’t think at all, and need support. Please come to see me next week during your visitation!” This was a man from Iran.

Unfortunately, it is those who do not ask for help who are really in trouble. The man who was detained for eight years, from what I understand, did not accept any requests for visitations, thus has no direct contact with people outside Ushiku.

Getting the Stories Out

Media attention does elicit response. This, despite tactics by the authorities to prevent the word getting out and around —by limiting visitations to members of the same block, circumscribing communication between blocks, and moving “troublemakers” to different blocks. News of the last big hunger strike was the impetus for starting a new twitter activist group #FREE USHIKU that has initiated a number of flash protests such as one on November, 2018 outside Shinagawa Detention Center, demanding the recognition of the detainees’ human rights.46

When one block had surveillance cameras placed in its shower room during the summer of 2018, reports about this invasion of privacy came out first in local, then national news. Soon afterwards the recently appointed Minister of Justice made a tour of Ushiku. Following his visit, the cameras were removed.

|

Picture depicting the mid-October crackdown by padded and helmeted guards after one block’s non-violent refusal to return to lockdown says at top: “The Japan Fascist Immigration officials duty and answering method to refugees Freedom request is to lock them up like prisoners of war.” Jean Jacques Rousseau’s sentiments are referenced from memory at the bottom: “Liberty is actual land of human in any case and any state.” |

During 2018, the satirical cartoons that illustrate this article were executed from inside Ushiku, some of them already shown on our website and exhibited at our 2018 Annual Meeting. They were done by the Iranian artist, FKM (Fery). He had drawn from the time he was a child, and had worked as a cartoonist at a newspaper as a young man. Arriving in Japan in 1992 when he was 27, he went back after a few years, but then returned to Japan because of severe religious persecution (having converted to Christianity during his time in Japan). He was picked up for overstaying. With plenty of time to refresh his drawing skills while in custody, Fery’s power with his pen afforded him a wide range of expression.

Aside from satire, his pen also took on the ability to document, and he drew a scene that no detainee could record by camera (although a guard could). The above cartoon communicates the fierce crackdown of the guards after members of Fery’s block refused to return to lockdown, in a non-violent protest of their long detentions due to continual denials of karihōmen “for no tangible reason.” After this action, the protesters were placed in solitary confinement as punishment.

|

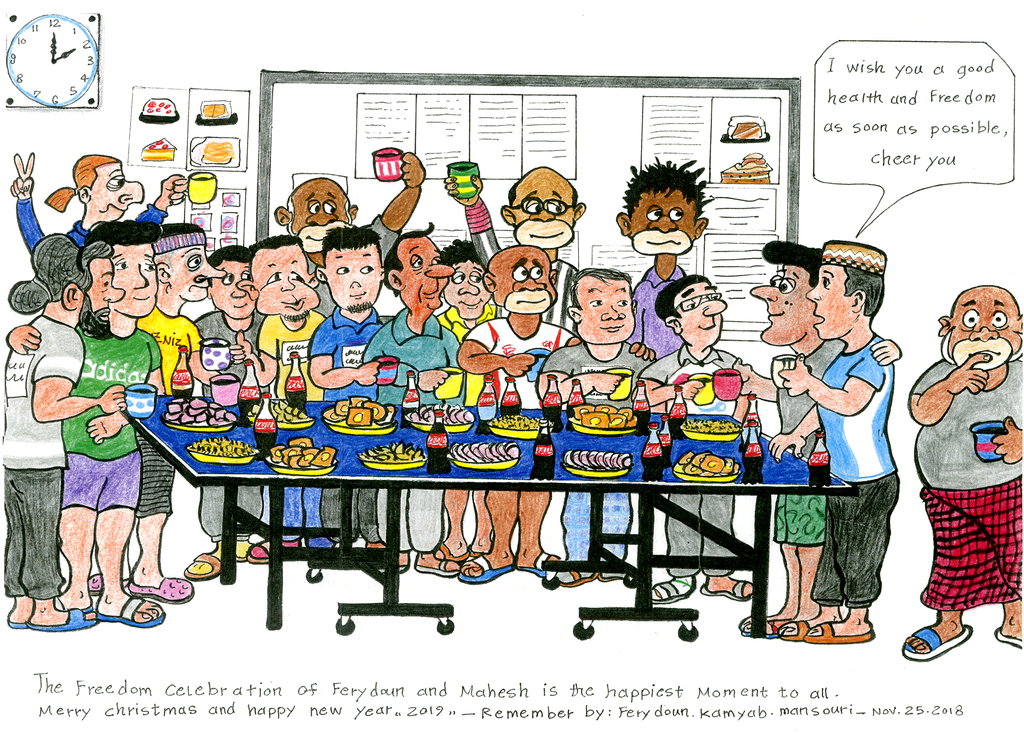

“The Freedom Celebration” when the cartoonist and his friend got a long-awaited “provisional release.” |

Fery’s cartoons have also helped develop a sense of affection and camaraderie among the detainees. The “remembrance” above records the farewell “freedom celebration” of Fery and his friend M who were finally granted karihōmen that allowed their release on parole at the beginning of December 2018. Through his depictions, those of us on the outside are afforded a glimpse of some of the humans of Ushiku, people simply unlucky for having chosen to migrate to Japan. Fery now hopes to accomplish a miracle, and get funding, legal support, and sponsorship to enable him to seek asylum in the UK, where his sister has been living.

Remove Border Controls that Penalize Workers!

As I write in December, 2018, the Abe regime is bulldozing through a bill to accept up to 345,000 new foreign blue-collar workers in an expanded trainee program to be implemented in April 2019. The human rights abuses in the existing trainee program (TITP) that saw 69 deaths between 2015-17 have been increasingly reported. Opposition leader Shiori Yamao claims “this program has used foreigners as cheap and disposable labor to fill the labor shortage…”47 Many complain that the new plan is far too vague and inadequately thought out. Yet with the ruling party in the majority, it passed. And by April, in a new organizational reshuffling and renaming, the Immigration Bureau will be upgraded to become the Foreign Residence Management Agency. This new agency will support strengthened foreigner migrant control policy and address security issues.

With this change in policy under discussion on the TV news, when I see detainees, many ask me, “Is there anything in it for us?” My answer is “Zannen (too bad)! The trainee program for foreigners that Japan is initiating does not include those who are in custody, those on karihōmen, or overstayers. The response toward those already in Japan will get tougher and tougher. We have to fight harder than ever to reverse these awful policies of Immigration Control!”48

With adequate pressure from those of us both inside and outside of Japan, the authorities in charge will surely be forced to stop these violations of human rights at detention centers. Similarly, with greater awareness, we can change the inhumanity of Japan’s almost total non-acceptance of refugees, as well as remove prejudice so as to allow foreign workers to permanently integrate into Japanese society.

APPENDIX: Support Organizations for Detainees at Ushiku

FEATURED ORGANIZATION

牛久の会

Official name: Ushiku Nyūkan Shūyōjo Mondai wo Kangaeru kai

牛久入管収容所問題を考える会 (Association Concerned with Issues at Ushiku Migrant Detention Center)

Leader: Tanaka Kimiko 田中貴美子

Address: 〒300-2642 茨城県つくば市高野 1159−4 田中貴美子 方

c/o Tanaka Kimiko, Takano 1159-4, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 300-2642 JAPAN

Email: [email protected]

ACTIVE RELIGIOUS MINISTRIES

牛久の友の会

Toride Catholic Church, Rev Michael Coleman working with Tsuchiura Catholic Church, Kato Kenji

- 20 years providing many needed items monthly, including phone cards

Tokyo Baptist Church Detention Ministry

- Known as the “Angel” of Ushiku, Alex Easley their member has been visiting Ushiku weekly for a decade, providing needed items and cheer.

See article here

CTIC (Catholic Tokyo International Center)

- Other religious ministries include: Jehovah’s Witnesses, Open House (a Catholic organization based in Saitama), Madina Masjid (Toda Mosque), Pentecostal Assembly of Jesus Christ

SOCIAL MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS

#FREE USHIKU

- A twitter group that called for demonstrations and direct action

@SYI_pinkydragon 難民とともに歩む収容者友人有志一

with blog

- See also: #RefugeesWelcome #WithRefugees #AsylumSeekers

STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS

- Student club from Tsukuba University that regularly visits Ushiku

WELGEE (Welcome to Refugees)

OTHER ORGANIZATIONS PROVIDING SUPPORT

ABIC Action for a Better International Community

国際社会貢献センター

APFS Asian Peoples Friendship Society

社会福祉法人 日本国際社会事業団

- For refugee support, once released

JAR Japan Association for Refugees

- For refugee support, once released

PRAJ (Provisional Release Association of Japan) 仮放免者の会

- Helps provide bond and other practical service to facilitate provisional release

RHQ Refugee Assistance Headquarters

- For refugee support, once released

Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan

UNHRC (United Nations High Refugee Commission)

For Further Research

Selected and annotated by Miriam Wattles

Aas, Katya Franko and Mary Bosworth (2013) The Borders of Punishment, Oxford University Press (multi-authored volume)

That this volume covering many regional locations in the world only contains a few lines on Japan is telling of the dearth of English-language material that considers Japan within the current global dynamic.

Bosworth, Mary (2014) Inside Immigration, Oxford University Press (book)

A revealing ethnography of several “removal centres” of the UK mainly from the perspective of detainees that reveals libraries and other services not available at Ushiku. Contains a useful overview of the history of detention in Britain.

Gloch, Alice and Giorgia Donà (2019) Forced Migration: Current Issues and Debates, Routledge (multi-authored volume)

A section on deportation being forced migration points to the human rights contradictions.

Chung, Erin Aeran (2010) Immigration & Citizenship in Japan, Cambridge University Press (book)

Focusing on the modern conundrum that Japan doesn’t allow even fourth generation immigrants who do not intermarry with Japanese to become citizens. Discussion of voting rights is already outdated.

Douglass, Mike and Glenda S. Roberts, eds. (2000) Japan and Global Migration: Foreign Workers and the Advent of a Multicultural Society, University of Hawaii (multi-authored volume)

A pioneer volume of collected essays on issues of multiculturalism in Japan, it raises some of the basic questions around migration from the standpoint of around 2000. Its succinct historical overview (ch. 2), and cultural analyses of the cultural formation of the Other in Kon Satoshi’s World Apartment Horror (ch 7) are still useful.

Fiske, Lucy (2016) Human Rights, Refugee Protest and Immigration Detention, Palgrave, Macmillan (book)

Answers a need for counter narration from detainee protesters, feared when depicted as having agency. Mainly focused on Australia, but its last chapter enters helpful global comparisons.

Graburn, Nelson HH et al, eds (2008) Multiculturalism in the New Japan: Crossing the Boundaries Within, Berghahn Books (multi-authored volume)

Another relatively recently published volume with essays treating “multiculturalism:” from the foreign executive, to international marriage, to blackness in Japan, to transnational activism from below.

Goodnow, Katherine, with Jack Lohman and Philip Marfleet (2008) Museums, the Media and Refugees: Stories of Crisis, Control and Compassion, Berghahn Books (multi-authored volume)

Hall, Alexandra (2012) Border Watch: Cultures of Immigration, Detention and Control, Pluto Press (book)

A most theorized examination of the everyday culture of the officers and others within “Locksdon” in the UK. Analyzes the Othering done by the “do-gooders” and at a Festival of the Faiths.

Hamlin, Rebecca (2014) Let me be a Refugee: Administrative Justice and the Politics of Asylum in the United States, Canada, and Australia, Oxford University Press (book)

Comparing the different “regimes” of American, Australian, and British RSD (Refugee Status Determination).

Hyun Mooam 玄武岩(2013) コレアンネットワークメディア・移動の歴史と空間 [Korean Networks: The History and Space of the Diaspora] Hokkaido University Press (book)

This highly theoretical study containing, among other points of focus, an excellent analysis of Omura Detention Center in its very complicated early years of existence.

Immigration Bureau, Ministry of Justice, (2017) Immigration Control: Understanding Japanese Immigration Control Administration (printed pamphlet)

_________________, 2017 Immigration Control, (November 1)

More for the general reader, the first listed pamphlet from Immigration Control was picked up at the Shinagawa Detention Center, while Immigration Control 2017 can be accessed online.

Jansen, Yolande and Roin Clikates and Joost de Bloois, eds (2015) The Irregularization of Migration in Contemporary Europe: Detention, Deportation, Drowning, Rowman & Littlefield (multi-authored volume)

Essays discuss the situation in Europe. Part III: Practices of Resistance is especially relevant to Ushiku.

Komai Hiroshi (1999, translation 2001) Foreign Migrants in Contemporary Japan, translated by Jens Wilkenson, Trans Pacific Press (book)

Although dated, this thorough account of migrant and migrant labor in Japan is helpful for seeing the recent history of our present trajectory.

Lee, Changsoo and George De Vos, eds. (1981) Koreans in Japan: Ethnic Conflict and Accommodation, UC Press (multi-authored volume)

Good on struggles around ethnicity, education and identity in Japan. Chapter on “Ethnic Education and National Politics”

Lie, John (2008) Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): Diasporic Nationalism and Postcolonial Identity, UC Press (book)

An analysis of Zainichi using literature and cinema as source.

Lim, Timothy (2009) “Who is Korean? Migration, Immigration, and the Challenge of Multiculturalism in Homogenous Societies” APJ 7:30, no. 1, July 27 (article)

An excellent comparative study focusing on identity of Koreans in Korea and on Korean identity in Australia.

Liu-Farrer, Gracia (2010) “Debt, Networks and Reciprocity: Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan” APJ 8:26, no. 1, June 28 (article)

Fujian as a case study of the types of networks that bring migrant workers to Japan. Broadly similar to other populations that migrate to Japan (e.g. Iran, Afghanistan).

Oh Tae-sung 呉 泰成(2018) 難民認定制度の当事者経験 ー 日本の難民認定申請者への聞き取りから Ajia Taiheiyo kennkyū sentaa nenpō (article)

_____ (2017) 収容と仮放免が映し出す入管政策問題 ー 牛久収容所を事例に Ajia Taiheiyo kennkyū sentaa nenpō Asia Pacific Research Institute, Osaka University (article)

Oh Tae-sung’s work is the most directly relevant to issues related to Ushiku Detention Center and includes helpful references (in Japanese), relevant statistics, and graphs.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2015) “Beyond Racism: Semi-Citizenship and Marginality in Modern Japan,” Japanese Studies, 35:1, 67-84 (article)

_______. (2010) Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era, Cambridge University Press. (book)

_______. (2008) “Migrants, Subjects, Citizens: Comparative Perspectives on Nationality in the Prewar Japanese Empire” APJ 6:8, Aug. 1 (article)

_______. (2006) “Invisible Immigrants: Undocumented Migration and Border Controls in Postwar Japan” The Journal of Japanese Studies, Volume 32, Number 1, Winter, pp. 119-153 (article)

Morris-Suzuki is the best single author in English on the modern history of migration control and their ties to issues around citizenship. The best coverage of Omura Detention Center in English is found in Chapter 6 of Borderline Japan.

Parikh, Neal S (2010) “Migrant Health in Japan: Safety-Net Policies and Advocates’ Policy Solutions,” APJ, 12-3-10, March 22. (article)

Good on the extensive health issues that face migrant workers and what advocacy groups are doing and suggesting.

Park, Sarah (2016) “’Who are you?’ The Making of Korean ‘Illegal Migrants’ in Occupied Japan 1945-52” International Journal of Japanese Sociology, no 25, 150-163 (article)

Repeta, Lawrence with an introduction by Glenda S. Roberts. (2010) “Immigrants or Temporary Workers? A Visionary Call for a “Japanese-style Immigration Nation” APJ 8:48 no 3. (article)

A summary of Sakanaka Hidenori’s progressive proposal. Sources cited in the introduction hint at the way it has gone instead.

Shipper, Apichai W. (2008) Fighting for Foreigners: Immigration and Its Impact on Japanese Democracy, Cornell University Press (book)

Begins from the basis of the difficulties of integration of workers; a chapter arguing that Japanese policies emphasize control, rather than the incorporation of foreigners; a chapter on the difficulties in the formation of temporary immigrant foreigner activist groups, another on Japanese immigrant rights activist groups, and another on media attention to these issues. An appendix lists groups in Tokyo and Kanagawa.

Tsuda, Takeyuki, ed. (2007) Local Citizenship in Recent Countries of Immigration, Lexington Books. (book)

A collection of essays that on the whole express optimism about local efforts to locally integrate migrant workers and other immigrants in Japan, and in Italy, Spain, and S Korea. (The key phrase is “local citizenship.”) An interesting essay by Tsuda on “the limits” of grassroots efforts concludes the volume.

Weiner, Myron and Tadashi Hanami, eds. (1998) Temporary Workers or Future Citizens? Japanese and U.S. Migration Policies, Palgrave (multi-authored volume)

The titular question remains most cogent. Although in need of updating, these essays address salient issues and give us a sense of recent origins of the present situation.

Wilsher, Daniel (2012) Immigration Detention: Law, History, Politics, Cambridge University Press (book)

A level headed analysis of the humanitarian contradictions in the practice of detention and ways it became a bureaucratic system. Contains a very useful history of US and UK practices (which conveniently omits WWII).

Yamamura Shunpei 山村純平 (2015) 難民から学ぶ:世界と日本 [Learning from Refugees: Japan and the World] Kaihō shuppan (book)

Yamamura Shunpei, et al eds. (2007) 壁の涙―法務省「外国人収容所」の実態 [The tearful wall: The true conditions in the Ministry of Justice’s “Migrant Detention Centers”] Gendai kikaku shitsu (multi-authored volume)

Yamamura has been one of the most important advocates for refugee rights in Japan since his return from refugee work in Afghanistan. The earlier book is an important collection of essays describing conditions in 2007, with one by past staff of Amnesty International Japan.

Yoshinari Katsuo 吉成勝男, Mizukami Tetsuo 水上徹男, eds. (2018)「移民政策と多文化コミュニティへの道のり」; [Immigration Policy and the Road to a Multicultural Community] (multi-authored volume)

Related articles

- Lawrence Repeta and Glenda S. Roberts, Immigrants or Temporary Workers? A Visionary Call for a “Japanese-Style Immigration Nation”

- Gracia Liu-Farrer, Debt Networks and Reciprocity: Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan

- Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Migrants, Subjects, Citizens: Comparative Perspectives on Nationality in the Prewar Japanese Empire

- Ryoko Yamamoto, Migrant-support NGOs and the Challenge to the Discourse on Foreign Criminality in Japan

- Sakanaka Hidenori, The Future of Japan’s Immigration Policy: a battle diary

Notes

Translator/collaborator’s note: The basis of this article is a translation of the essay (with the current title) by Tanaka Kimiko, that appeared in序局 108 (Sept, 2018). While interviews, research, and fieldwork (from August through December, 2018) allowed me to augment this article with further data, pictures, description, and historical contextualization, I sought to retain the first-person voice and main argument of Tanaka in the main text. All footnote citations are mine, as is the annotated bibliography For Further Research, and the Appendix. Inasmuch as this is co-authored, the members of the Ushiku no Kai as a whole should be credited, in particular Oh Tae-sung, who graciously provided data and pointed me to most of my cited sources. Appreciation also is due to Ellen Hammond, Tom Blackwood, Kirk Wattles and especially to Mark Selden for editorial suggestions. FYK and all the other anonymous Ushiku detainees who shared their stories, and more, have my deepest gratitude.

Ushiku no Kai (Ushiku Group) is short for the official name, Ushiku Nyūkan Shūyōjo Mondai wo Kangaeru kai (牛久入管収容所問題を考える会) that translates to Association Concerned with Issues at Ushiku Migrant Detention Center. See Appendix for more contact information.

See Appendix for a list of the organizations and churches that provide support to Ushiku Detention Center.

This is the total held on any one day. The total number of different persons who were detained in a center at some point in 2017 was 13,400. Unless otherwise noted, the data was provided to Ushiku no Kai by the Ministry of Justice. The data in included within Ushiku no Kai’s annual reports for 2017 and 2018 (資料集: 年間活動報告会&交流の集い)

See Asahi shinbun, “Jiyū seiyaku sare shōrai wo hikan” Sep 23, 2018 for a full account. The briefing that Tanaka gave to the press conference can be found on the Ushiku no Kai website.

See Oh Tae-sung (2017) 収容と仮放免が映し出す入管政策問題 ー 牛久収容所を事例に for statistics and comments on this. See also the APFS report on “Special Permission for Residence” which points out how many fewer permissions were given out after the 2003 policy of halving the number of illegal foreigners.

This type of clemency fluctuates over the years. See Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan, 176, and chapter 7, on this from the perspective of a decade ago, when it had gotten easier to attain.

Ohashi Takeshi, of the JLNR 全国難民弁護団, at his keynote address to the Annual Meeting of Ushiku no Kai on Dec. 16, 2018, made the point that in 20 years, he had not seen it so dire.

「檻なしの刑務所」Quoted in Oh Tae-sang (2017). Garnered from a survey, this article includes many other salient quotes about the way provisional release can destroy lives. More international comparisons of parole systems are warranted.

See Chung (2010) for a discussion of the difficulties of naturalization in Japan, especially the multi-generational conundrum.

Wilsher (2012) sees a shift since the 1980s towards increased detention while Hamlin (2014) sees a turn from the end of the Cold War in 1989 towards increased forced deportations. It is beyond the scope of this article to go into questions of where Japan stands relative to other nations. In the hopes of forthcoming work of this nature, “For Further Research,” annotates studies discussing immigration control and detention outside of Japan.

Ministry of Justice, Immigration Control 2017, can be read against the grain for its double-tiered emphasis on ease of entry for high-level professionals, on the one hand, and constrictions on entry for guest workers, on the other.

There is no easy distinction between refugees and migrants See, for example, The Guardian, “Five Myths About the Refugee Crisis” (June 5, 2018) Morris-Suzuki also makes this fundamental point in Borderline Japan, 150-51.

The 1994 Prying Open the Door: Foreign Workers in Japan, Carnegie Endowment Publication, Contemporary Issues Paper no. 2, 52 and passim, is an excellent overview of the “vexatious” problems as they existed about 25 years ago.

Foreigners with any visa status, even those with family visa status or permanent residence, can have their status revoked. This is related to the dramatic slow-down in giving out the “special permit of residence” (see above).

On Oct. 31, 2018: Fukuoka (7) and Hiroshima (1) Takamatsu (1) while six other facilities had none.

Statistics from Ministry of Justice for October 31, 2018. Comparable numbers from October 23, 2017: Nagoya (208), Yokohama (87) Osaka (110), Ōmura (87) Tokyo (549) and Ushiku (324)

See Morris-Suzuki, (2008) “Migrants, Subjects, Citizens: Comparative Perspectives on Nationality in the Prewar Japanese Empire” APJ 6:8, Aug. 1.

See Morris-Suzuki, (2015) “Beyond Racism: Semi-Citizenship and Marginality in Modern Japan,” Japanese Studies, 35:1, 67-84

These numbers are necessarily rough and contested. Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan, 53, notes that 1.3 million of the 2 million Koreans in Japan left for Korea between the surrender and the end of 1945.

For an analysis that incorporates the effect of The Imperial Ordinance of Alien Registration, see Sarah Park (2016) “’Who are you?’ The Making of Korean ‘Illegal Migrants’ in Occupied Japan 1945-52” International Journal of Japanese Sociology no 25, 150-163.

Tanaka, in her original article upon which this is based, made an argument about the participation of Zainichi in the thwarted Feb 1, 1947 General Strike and the following May 1, 1952 strike, which I elide here.

See, for example, Hicks and Lie. See also Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan, 111-115, on the significance of the crucial separation between immigration and naturalization policies in Japan.

To augment Tanaka’s original argument, I relied on Morris-Suzuki, Borderline Japan, and, in Japanese Hyun Mooam 玄武岩(2013) コレアンネットワークメディア・移動の歴史と空間 Hokkaido University Press. Both cite helpful primary sources.

Sometimes referred to as “Hario Concentration Camp” in SCAP documents. See Morris-Suzuki, Borderline, 78, and passim.

Morris-Suzuki, Borderline, 100-111, discusses the American Cold War influence on this reorganization and stresses how at this time it was first centralized into one agency. I note thats “Japanese Schlindler,” Sugihara Chiune, could only save 6,000 Jews with exit visas for transit through Japan from Lithuania because he was in the Foreign Ministry.

Tanaka, in her original article, emphasized the massacre of thousands on the island of Jeju, survivors of which made up a majority of those who returned to Japan.

密航者 This crackdown was a continuation of earlier operations run by the occupying forces. See Chapter 3 in Morris-Suzuki, Borderline.

Morris-Suzuki, Borderline, 154, states the number at 7,000 (including fire brigade members) citing Hōmusho Nyūkosha Shūyojo, Ōmura Nyūkosha Shūyojo.

The story is complicated, but the two groups were known as Mindan and Chōren then Sōren (the former associated with South Korea and the latter with North Korea). See Morris-Suzuki, Borderline, 100-101, 160-161, and passim.

See, for example, USA for UNHCR: The UN Refugee Agency: Refugee Facts (accessed 2/14/19). The number of displaced people at the end of 2017 was 68.5 million and it has continued to rise. This is the highest recorded level. The estimated displaced of people in 1945 was 40 million, with a smaller world population.

According the Japan Times March 14, 2018, “JLNR and UNHCR data shows that just 36 out of 6025 resident Kurds have been granted “special residency status.”

Given that there is no dearth of examples of other nations with harsh immigration controls (in the media as in scholarship), further consideration of Japan within the current global state of affairs is merited.

This “Mandate Refugee” system is cited, for example, in the documentary. (Thanks to Tom Blackwood for this reference.)

Bosworth (2014) reveals how much easier detainee communication to the outside world is in British deportation centers. I am also struck by how the cartoonist who goes by the pseudonym Eaten Fish and the writer Behrouz Boochani garnered international attention and acclaim by means of web and cell phone while detained by Australia, something impossible to achieve in Japan.

The phrase 使い捨て労働力was repeated in the Asahi newspaper. Quoted in The Washington Post, Nov 21, 2018 “Japan wakes up to the exploitation of foreign workers as an immigration debate rages.”