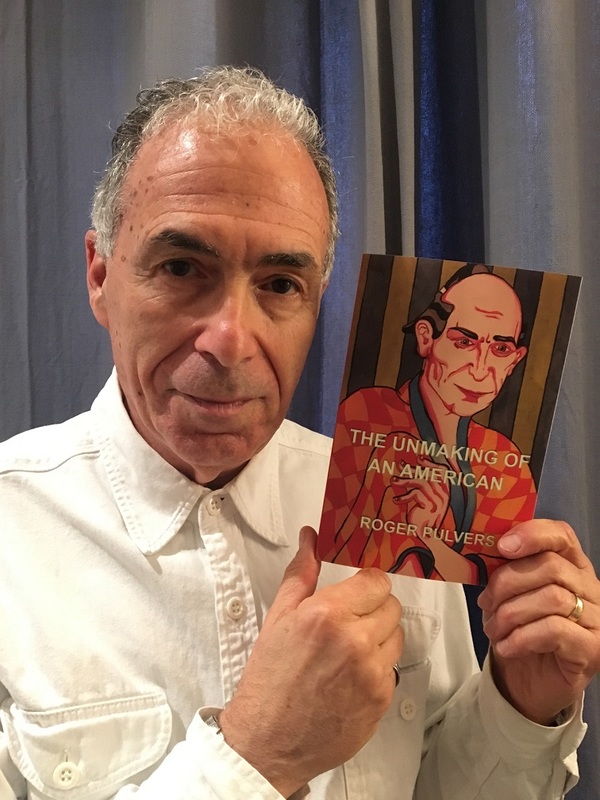

On 15 March, Balestier Press brings out Roger Pulvers’ autobiography, “The Unmaking of an American.”

This book is an exploration of the nature of memory and how it links us with people from different places and distant times. It ranges from Roger’s upbringing in a Jewish household in Los Angeles to his first trip abroad, in 1964, to the Soviet Union; from his days at Harvard Graduate School studying Russian to his stay in Warsaw, a stay that was truncated by a spy scandal that rocked the United States; from his arrival in Kyoto in 1967 to his years in Australia, where, in 1976, he gave up his American citizenship for an Australian one.

|

“The Unmaking of an American” is a cross-cultural memoir spanning decades of dramatic history on four continents. The excerpts from the book below present a wide-ranging introduction to the range of Japanese contemporary cosmopolitan culture and moral issues confronting Japan and the United States at war from the Asia-Pacific War to the Vietnam War, from war crimes tribunals of Japanese generals to the firebombing and atomic bombing of Japan, to the Vietnam War. They include introducing the author’s interactions with leading Japanese filmmakers, playwrights and authors, among others: Oshima Nagisa (Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) and Shinoda Masahiro (Spy Sorge on Comintern espionage in China), playwright Kinoshita Junji (author of a play on the Sorge affair), and Koizumi Takashi (Best Wishes for Tomorrow). It reveals the author in some of his multiple roles as director and director’s assistant, scriptwriter, actor, novelist, playwright and translator.

Besides the experience of being Oshima Nagisa’s assistant on “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” I have had other encounters with the Japanese film industry.

|

In the mid-1990s, when the economy was still stagnating and the Japanese were looking for a light at the end of a tunnel of unknowable length, veteran film producer Araki Seiya, who I had known then for over a decade, approached me with a proposal. He was preparing to produce a full-length animated film version of The Diary of Anne Frank and would I write the script together with him. I was of course thrilled. Being the only Jewish playwright who wrote in Japanese I guess I had the market cornered on scriptwriters for a Japanese film version of The Diary of Anne Frank.

The producer and I set out on a location hunting trip to Amsterdam in 1994. I had been to Holland in March 1967 but had not visited the secret annex where Anne Frank had taken refuge during the war with her sister, parents, the Van Pels family and a dentist named Pfeffer.

The people who managed the Anne Frank Museum where the secret annex is located were very courteous and helpful, though apparently nonplussed as to why “the Japanese” would be making this film. I told them that The Diary of Anne Frank was arguably the most popular book among young Japanese girls and that in all probability a greater percentage of people in Japan had read it than people in the West. To the managers of the museum it seemed that Japan was seen only as an ally of Germany in the war. While it is true that many Japanese readers of the book might not grasp the significance of historical elements of anti-Semitism in Europe of the time, they could identify with the story of Anne as one of an isolated girl in puberty coming to terms with the agonies of familial pressure and first love.

Once the film was finished and ready for release Araki Seiya hired out the Budokan, the indoor arena in Tokyo’s Kitanomaru Park near Kudanshita Station, for a preview. Upwards of ten thousand people, most of them young women and girls, filled the hall for the screening. British composer Michael Nyman, who wrote the film’s score, came for the screening and played the two theme songs on a grand piano. I had written the lyrics for these two songs, “If” and “Why.” It was a thrill just to listen to Michael play them, as it was to hear the amazing Welsh contralto Hilary Summers sing them at the Edinburgh Festival in August 1997 when my wife Susan, the children and I fortunately happened to be driving around Scotland on a holiday.

The film, however, was not a commercial success, though it was beautifully animated and voice-acted. I had not seen eye-to-eye with my co-scriptwriter, who had insisted on following the book scene by scene. I had begged him to emphasize the budding love between Anne and Peter van Pels. Anne was thirteen and feeling the pangs of puberty, which she discusses with amazing candidness in the diary. Peter was sixteen. The kiss in the attic of the secret annex was fleeting in the film; and Anne’s intense longing for a relationship, played down. I could not get my co-scriptwriter to go along with giving the kiss scene and Anne’s feelings for Peter more screen time. He was, after all, also the producer, and a most insistent, to put it mildly, partner in the creation of the script. But even if that young love had been developed in the script, the film itself might not have become a hit. While Japanese audiences of all ages do love animated feature films, most of the ones that strike a chord with them are fantastical and full of bizarre happenings, or based on strictly Japanese themes. I suppose the young women and girls of Japan that we considered our potential core audience had derived everything they desired from the story out of the reading the diary itself and felt there was nothing to add to their experience of it in a full-length animated feature film.

I Finally am in the Company of a Real-life Spy

In March 2002 a letter came to me from an old agent friend in Tokyo, Takahashi Junichi. Shinoda Masahiro, film director of the same generation as Oshima Nagisa and Yamada Yoji, had contacted Takahashi to get in touch with me about a role in his upcoming film, “Spy Sorge.”

Susan and I had taken the children to Sydney in early 2001. It was heartrending to leave Kyoto. We had felt utterly at home there. The house we rented in Kyoto’s north, built in the 1920s, was admittedly old-fashioned (which is why Japanese people did not want to rent it), with a sprawling floor plan of tatami-mat and polished wooden floorboard rooms surrounding a nakaniwa, or inner quadrangle garden, with a Japanese maple tree and a large stone lantern in it. It was wonderful for the children to be able to experience life in such a traditional Kyoto home. Our son, the eldest of our children, was about to enter university, and the three girls were in need of English-language education. The four children were speaking Japanese – and Kyoto dialect, at that – among themselves.

The letter from Tokyo had come at a good time. I was about to return to my teaching job at Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan’s leading science university and, founded in 1881, the second oldest national university, after the University of Tokyo, in Japan. (I commuted between home in Sydney and work in Tokyo about ten times a year, from 2002 until 2012.)

I arrived back in Tokyo on April 1, 2002 and moved into the old home of my dear friend, the brilliant translator and author Shibata Motoyuki, in Nakarokugo, not far from Kamata Station in the southwest of the city. The Shibatas had moved out and were drawing up plans to demolish the old house and put up a new one. They were kind enough to let me stay at that home while it still stood. Three days later I flew to the port town of Moji in northern Kyushu for the “Spy Sorge” shoot. Moji-ku, now a district in the large city of Kitakyushu, boasts beautiful stone and brick buildings erected in the Meiji era and suitable for film locations.

Born in Baku in 1895 to a German father and Russian mother, Richard Sorge had spent his early years in Berlin. He fought on the German side in World War I, was wounded and awarded an Iron Cross. His subsequent studies of political science – he received a PhD in the subject in 1920 from the University of Hamburg – and a growing despair over the inability of capitalism to alleviate postwar Europe’s gaping inequities led him to embrace communism. He joined the Communist Party and made his first trip to Moscow in 1924 where he was promptly recruited and trained to be an agent for the Comintern. In 1930 he was put directly under Red Army intelligence supervision and ordered to base himself in Shanghai. It was in Shanghai that he first met Agnes Smedley, the famous American journalist sympathetic to the Marxist cause; and Smedley in turn introduced him to Asahi Shimbun reporter Ozaki Hotsumi.

Ozaki proved to be an invaluable source of information for Sorge, providing him with a slew of contacts in Shanghai’s radical underground. When the Japanese invaded Shanghai in January 1932 Sorge’s meticulous accounts of the battles were the most accurate information that Moscow was to get on the events.

Sorge returned briefly to Berlin in 1933, bolstering his cover by joining the Nazi Party. Shortly after that he made his way to Japan, again to act as a Comintern agent. Excellent journalist armed with impeccable credentials and devastatingly handsome, he soon earned the confidence of Germany’s ambassador, Eugen Ott, as well as the favors of the ambassador’s love-stricken wife, Helma. The doubly unsuspecting Ott went so far as to elicit Sorge’s help in composing his reports to Berlin, reports that Sorge also secretly sent to Moscow.

Sorge and Ozaki were arrested in Tokyo in October 1941 and held in Sugamo Prison, where they were tortured, interrogated and, in November 1944, hanged. His Japanese executioners chose November 7 for Richard Sorge’s hanging because it marked the anniversary of the Russian revolution.

“Spy Sorge” charts the flamboyant and clandestine movements of the man that Ian Fleming called “the most formidable spy in history” right up to his end on the prison gallows. As for me, I played the American journalist who introduced Sorge to Ozaki, a part so vital to the story that I knew, no matter how bad my acting, would not be cut. I was thrilled. Back in the late 1960s, when I had been framed by the CIA and the reporters who were in their sway (if not their pay), I had missed the chance to knowingly have an encounter with a real spy. Now in “Spy Sorge” I had one.

I had another brush with Ozaki in 2008 when the New National Theater staged Kinoshita Junji’s play about him, “A Japanese Named Otto.” Otto was Ozaki’s code name during the years of his espionage activities. I was asked by my good friend, director Uyama Hitoshi, who had also directed many of Inoue Hisashi’s plays, to provide English-language dialogue for the play, as a good portion of it is purportedly spoken in English by Ozaki and the various foreign spies, though written by Kinoshita in Japanese.

“A Japanese Named Otto” was first performed in 1962, and this is critical to understanding its context. Kinoshita had been a sympathizer with leftist causes ever since his prewar days at the University of Tokyo (then called Tokyo Imperial University). But it was the anti-American riots of 1960, motivated by popular opposition to the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the U.S., that catalyzed Kinoshita’s ire toward Japanese official acquiescence over the gradual remilitarization of his country at the behest of the United States, a pattern that has continued since the 1960s and was accelerated by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo in the middle of the second decade of this century. Kinoshita shows deep sympathy for Ozaki, a man who allegedly betrayed his country in the belief that true patriotism may require one to do just that.

It was a shame that Shinoda’s film about Richard Sorge failed miserably at the box office. After all, James Bond has nothing on Sorge: consummate spy, dyed-in-the-wool womanizer, gambler, drunkard, motorcycle geek. When I was first shown the script at the beginning of April 2002, however, I was worried. Written by the director, it strove to be a document of Japan’s historical leadup to war rather than an intimate portrait of this amazing man, his exploits and inner torments. Sorge resisted returning to Moscow in the late 1930s. He knew that he would come under the suspicion of a paranoid Stalin and be liquidated, yet he tirelessly dedicated himself to his ideal of a communist revolution. This conflict of the heart and the intellect alone makes him a superb character for a drama in such brutal times. The themes for both the real Richard Sorge and the real Ozaki Hotsumi revolve around national guilt and personal betrayal. How the two men maintained their faith in their beliefs and in each other is a heroic saga of tragic proportions.

The 200-odd letters that Ozaki wrote to his wife and daughter from prison were collected and published posthumously under the title Aijo wa furu hoshi no gotoku (Devotion is like a shower of stars). These moving letters comprise, to my mind, the most remarkable personal documents to emerge from the war years in Japan. By all rights, Ozaki Hotsumi should be considered a hero to present-day Japanese as a man who loved his country too deeply to permit it to victimize millions of people in Asia and the Pacific.

“Best Wishes for Tomorrow”

The war continued to provide the vehicle that took me, after working with Oshima and Shinoda, to yet another Japanese film.

“Ashita e no Yuigon,” to which I gave the English title “Best Wishes for Tomorrow,” was directed in the late spring and early summer of 2007 by Koizumi Takashi, a man who had been Kurosawa Akira’s first assistant director on some of his later films and who had become, after the great master’s death, a director in his own right. “Best Wishes for Tomorrow” was Koizumi’s fourth film. This time I was asked to co-script the film with the director himself. But it also gave me the opportunity to be on the set and on location every day for nearly a month. Since the set was at the Toho Studios near Seijo Gakuenmae Station, the daily trip there on the Odakyu Line was like going home. (We had also lived at two different homes in Seijo, one of Tokyo’s most beautiful suburbs, once in the mid-1980s and again in the mid-‘90s.)

“Best Wishes for Tomorrow” takes up the real-life story of Maj. Gen. Okada Tasuku of the Tokai Army that was given the task of defending central Honshu. Several weeks before World War II ended on August 15, 1945 Okada ordered the execution of captured American fliers. He and his men considered the Americans to be war criminals for the indiscriminate bombing of Japan that took the lives hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians.

After the war Okada and nineteen of his subordinates were brought before an American military tribunal. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death. Those tribunal proceedings were part of the Yokohama War Crimes Trials that ended in 1948.

Okada was one of the very few Japanese military leaders who took full responsibility for his actions — and perhaps even welcomed the verdict as one that allowed him to assuage his guilt. There is sufficient evidence in the historical record to believe that Okada saw his own death as the beginning of a new era of friendship between Japan and the United States. (I had pored over more than 1,000 pages of trial transcripts in preparation for working on the script.) He hoped there would someday be a world in which the mentality that led to his extreme actions and those of the American bomber crews would cease to exist. Hence, best wishes for tomorrow….

Much of our film was taken up by the trial of Okada, played brilliantly by veteran actor Fujita Makoto, known in Japan primarily for his detective roles. (Sadly Fujita passed away from esophageal cancer not long after the release of the film.) His wife, Haruko, played by Fuji Sumiko, sits in the courtroom during the trial. The two are not allowed to speak to each other. The silent bond between them, as Okada faces a sentence of death by hanging, is strong and poignantly expressed in looks, smiles and nods. (By coincidence, I directed Fuji Sumiko’s daughter, Terajima Shinobu, in my own film, “Star Sand,” ten years later.)

The real hero of “Best Wishes for Tomorrow” is the trial itself. That an American military tribunal could be utterly fair, even going to the extent of trying to get the general to give his testimony in a way that would exonerate him from the death penalty, constitutes a milestone of American military justice. I was confident when we were shooting the film that American audiences would respond to its messages. In the end, however, we could not get an American distributor to take it up.

The Okada trial marked, to my knowledge, the only occasion when testimony stating clearly that the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki constituted a war crime was admitted as evidence in an American court. Perhaps this evidence remaining in the dialogue, however faithful to the trial’s transcript, proved to be an obstacle to an American distributor accepting the film for distribution in the United States.

Any film of a trial can get bogged down in tedium. The tension in the drama must be maintained through the onscreen expression of the characters’ inner motivations. Why did Okada execute the Americans? What were his feelings when assuming responsibility for his actions? What was going on inside the mind of the American defense attorney, wonderfully portrayed by actor Robert Lesser, as he accused his own people of having been war criminals?

This is where the use of three cameras came in to good effect. A luxury in filmmaking, it meant that all the actors in the courtroom had to be present at all times, since virtually all angles were visibly covered during a take. Hence, when Camera A was filming the prosecutor grilling Okada, what were the fears and hopes of his wife and son, who are sitting in the courtroom? Camera B picked this up. Meanwhile, Camera C might be focused on the nineteen subordinates on trial with Okada. Are they going to be given the death sentence for following orders? These portraits can be intercut during the questioning, giving insight into what torments Okada’s loved ones and his former subordinates were experiencing.

One of my roles during the shoot was to make sure the English dialogue was spoken properly and to liaise between the foreign actors and the director. The other role was as an actor playing the head of Sugamo Prison, which during the Allied Occupation housed suspected and convicted war criminals. As prison head I wore, for the first time in my life, a U.S. Army uniform, just a costume of course, and stood beside the Stars and Stripes in front of photographs of Pres. Harry S. Truman and Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Were my parents still alive they would finally have been able to say, “My son, the Captain!”

“Best Wishes for Tomorrow,” which was based on the book Nagai Tabi (The Long Journey) by one of the postwar era’s greatest literary figures, Ooka Shohei, presents the life of a man who believed that those at the top of the chain of command must take responsibility for their decisions. If this theme had resonated with people around the world today and we could have recalled it subsequently in bringing to justice leaders on all sides who commit war crimes, then Okada’s wish for a better future might not have been made in vain.

In the film, as in the real trial, Okada praised the fairness of the proceedings, telling the military commission that tried him between March 8 and May 19, 1948:

“This trial has been very generous in its proceedings. I firmly believe that my feelings of gratitude will be the basis of a spiritual bond between the elder brother, America, and the younger brother, Japan, uniting our two countries in the future.”

The Yamashita Precedent

The theme of war crimes was not a new one to me. In 1970 I had written a play titled “Yamashita” while living in my tiny rented house by Midorogaike, the Deep Muddy Pond, in the north of Kyoto. The title referred to Gen. Yamashita Tomoyuki (who was also called Tomobumi). Referred to as the “Tiger of Malaya,” Yamashita was the general who led troops down the Malay Peninsula, some of them on bicycle, to capture Singapore on February 15, 1942. Later in the war the general was in Manila when that city fell to the Allied Forces.

After the war Gen. Yamashita was arraigned for failing “to control the operations of the members of his command,” tried before an American military tribunal in Manila, found guilty of war crimes and hanged a few minutes after three a.m. on February 23, 1946, despite the fact that he had specifically issued orders to his troops not to exceed the bounds of accepted engagement and was unable, given the desperation of the Japanese situation and the breakdown of communications, to prevent the committing of atrocities by his men. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, refused to commute Gen. Yamashita’s death sentence, issuing a short statement in which he condemned the convicted general for, among other things, “transgressions (that are) a stain upon civilization and constitute a memory of shame and dishonor that can never be forgotten.”

The Yamashita case surfaced in the U.S. media many years later in the context of alleged crimes committed by American troops in Vietnam. The case had created a precedent: that a general in charge of soldiers may be held accountable for the actions of those soldiers even if he had issued orders to prevent them. U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, Telford Taylor, writing in late 1970, made the stark comparison: “… If you were to apply to (General Westmoreland and other U.S. generals) the same standards that were applied to General Yamashita, there would be a very strong possibility that they would come to the same end as he did.”

I wrote “Yamashita” in 1970 before becoming aware of the case’s relevance to American war crimes in Vietnam. It was a trip to Nagasaki in December 1968 that started me thinking about the theme of war crimes. I visited the Peace Museum that month. Among the awful remnants of destruction caused by the dropping of the atom bomb on August 9, 1945 there was a single photograph that had transfixed me. It pictured a small group of America fliers standing beside a Boeing B-29 Superfortress. They had their arms over each other’s shoulders and were grinning. Behind them, painted on the side of the bomber, was the image of a cute little choo-choo train car with the wings of an angel attached. On one side of the train was the word “Nagasaki,” painted in the bamboo-like letters that you often see in Western depictions of Oriental writing; on the other side, “Salt Lake.” Below this logo symbolizing nuclear catastrophe was one word in rounded bold lettering: Bockscar (named after the plane’s usual pilot Frederick C. Bock).

All of this must have been painted on the plane after the plane’s return from its mission, for the original target was the city of Kokura in northern Kyushu. An overcast sky saved that city and doomed Nagasaki some 150 kilometers away. A little sign by the photograph in the Nagasaki Peace Museum stated that this airplane that had dropped a bomb causing up to 80,000 deaths by the end of 1945 was on display at the U.S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio. It is still on display to this day beside a replica of “Fat Man,” the bomb itself.

That photograph was the most horrible and upsetting thing I saw that day in Nagasaki in 1968. It spoke of my country’s arrogance of triumph and giddy delight, punning crudely on the word “scar,” over what comprised, together with the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima, the greatest single acts of mass murder in the history of the world. Hiroshima and Nagasaki are Japan’s Holocaust, though the world, Japan included, seems reluctant to accept that fact. That photograph became the initial impulse behind the writing of “Yamashita.”

The play is only laterally concerned with the Japanese general’s trial. In fact it takes place not in Manila in 1946 but in Hawaii in 1959, when a teacher of Japanese, a Chinese-American named Chow, finds himself alone in a classroom with a student named Yamashita. The name triggers memories of his being tortured by Japanese during the war. An old janitor comes into the room thinking that the lesson is over. In a transformation of place and time, the classroom turns into a courtroom and the janitor, the black curtains over the window serving as judicial robes, a judge. The re-enacted “trial” ends with a recreation on stage of the dropping of the atom bombs. The judge reverts to his former role of janitor and walks out, leaving the student named Yamashita in the hands of the former POW teacher.

“Yamashita,” published in Australia in 1981 by Currency Press, has had a number of productions, including one that I directed myself in Canberra as my farewell production before leaving for Melbourne in January 1980.

Writes composer/musician Sakamoto Ryuichi of The Unmaking of an American: “Roger has fearlessly thrown himself into the whirlpool of cross-culturalism. His life reads like an adventure story.”