It is over seventy years since the issue of systematized sexual abuse in the Asia-Pacific War came to light in interrogations leading up to the post-Second World War Military Tribunals. There was also widespread vernacular knowledge of the system in the early postwar period in Japan and its former occupied territories. The movement for redress for the survivors of this system gained momentum in East and Southeast Asia in the 1970s. By the 1990s this had become a global movement, making connections with other international movements and political campaigns on the issue of militarized sexual violence. These movements have culminated in advances in international law, where militarized sexual violence has been addressed in ad hoc Military Tribunals on the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda and is explicitly addressed in the Rome Statute which established the International Criminal Court.1 Cultural politics and the politics of commemoration have also been an important element of the movements for redress. Here, we survey some of the physical sites of commemoration of this issue. We survey sites in Australia, South Korea, Japan, the US, China, and Taiwan. The elderly women, who have been demonstrating and campaigning for decades are respectfully referred to as the ‘Grandmothers’. We argue that these sites commemorate not only suffering, but also the activism of the survivors and their supporters. These twin themes can be introduced through a discussion of the Australian War Memorial’s depiction of Dutch-Australian survivor Jan Ruff O-Herne.

The Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial was established at the end of the First World War as a ‘shrine, a world-class museum, and an extensive archive’.2 Its mission is to ‘assist Australians to remember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society’.3 The holdings include ‘relics, official and private records, art, photographs, film, and sound’. The physical archive is augmented by an extensive on-line archive of digitized materials.4 From the end of the First World War to the present, the Memorial has been the official repository for the documentation of Australia’s involvement in military conflicts and peacekeeping operations. It has employed historians, archivists, journalists, film-makers, photographers, and artists.

The Australian War Memorial is devoted to documenting the Australian experience of war. As has been argued elsewhere, the presence or absence of individuals in this archive reflects hierarchies of nationality, ethnicity, racialized positioning, gender, class, and status as soldier or civilian, enemy or ally. The closer an individual is to the military institution, the higher their rank, and the more closely they are connected with Australia, the more likely they are to be mentioned.5

As far as we know, the museum section of the Australian War Memorial has only one permanent exhibit which focuses on the association of military institutions with brothels, prostitution, and sexual violence, an exhibit which we will discuss below.6 Nevertheless, a temporary exhibition in 2016 included Australian art which depicted relations between Australian women and US soldiers stationed in Australia.7

In the archives, though, there are trails which can be followed, particularly now that so many records have been digitized.8 We can find interrogation reports which mention incidents of sexual violence and the enslavement of women by Japanese troops in South East Asia.9

One on-line exhibition of the Australian War Memorial includes discussion of the experiences of Jan Ruff O’Herne, who suffered sexual abuse at the hands of the Japanese military in the occupied Netherlands East Indies in 1944.

Jan O’Herne was born in 1923 at [Bandung], in central Java. After the Japanese invasion of the [Netherlands East Indies], she, her mother, and her two sisters were interned, along with thousands of other Dutch women and children, in a disused and condemned army barracks at Ambarawa.

In February 1944 a truck arrived at the camp, and all the girls 17 years and above were made to line-up in the compound. The ten most attractive, including Jan O’Herne, were selected by Japanese officers and told to pack a bag quickly. Seven of the girls (including O’Herne) were taken to an old Dutch colonial house at [Semarang], some 47 kilometres from their camp. This house, which became known to the Japanese as ‘The House of the Seven Seas’, was used as a military brothel, and its inmates were to become ‘comfort women’.

On their first morning at the house, photographs of the girls were taken, and displayed on the front verandah which served as a reception area. Visiting Japanese personnel would then select from these photographs. Over the following four months, the girls, all virgins, were repeatedly raped and beaten, day and night. Those who became pregnant were forced to have miscarriages.

After four harrowing months, the girls were moved to a camp at Bogor, in West Java, where they were reunited with their families. This camp was exclusively for women who had been put into military brothels, and the Japanese warned the inmates that if anyone told what had happened to them, they and their family members would be killed. Several months later the O’Hernes were transferred to a camp at Batavia, which was liberated on 15 August 1945.

In 1946, O’Herne married British soldier Tom Ruff, whose unit had protected the camp from Indonesian freedom fighters after its liberation. The two emigrated to Australia from Britain in 1960.10

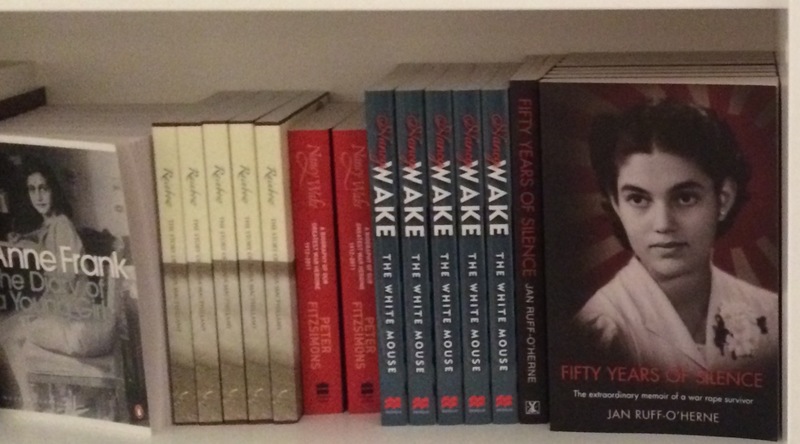

The on-line narrative of Ruff O’Herne’s experiences is supplemented by three items of material culture. The first is a photograph of O’Herne at age nineteen, just before the Japanese invasion. This photograph has become iconic, and graces the cover of her autobiography, Fifty Years of Silence.11

|

Figure 4.1: Jan Ruff O’Herne’s memoir, Fifty Years of Silence, on display in the Australian War Memorial Bookshop, July 2016; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

The second is a handkerchief embroidered with the autographs of the interned Dutch women who were enslaved in the ‘House of the Seven Seas’ with Ruff O’Herne.12 The third is an apron embroidered with the names of the women interned at Kamp 1A Ambarawa Internment Camp.13 Ruff O’Herne’s handkerchief is currently displayed in the Australian War Memorial, alongside other material artefacts from internment camps and prisoner of war camps of the Second World War.

The caption to the display acknowledges not only her wartime sufferings but also her post-Second World War activism.

Handkerchief of a ‘comfort woman’

…She survived the brutal assaults but, traumatised, could not speak about her experiences. She married, had children, and with her family migrated to Australia, always living with the memory of her terrible ordeal. In 1992, in Tokyo, with other former ‘comfort women’, O’Herne courageously spoke out about Japanese wartime atrocities. In her book, Fifty Years of Silence, she describes how the Japanese military used tens of thousands of women, mainly from Korea and Japan’s Asian territories, as sex slaves.14

In the caption to the Australian War Memorial display, Ruff O’Herne’s handkerchief is described as the ‘handkerchief of a “comfort woman”’. The quotation marks around ‘comfort woman’ suggest that the War Memorial’s curators were aware of problems with this terminology, but chose to use the most commonly understood term for the enforced military prostitution/military sexual slavery system perpetrated by the Japanese military in the Asia-Pacific War. In the text below the caption, however, the term ‘sex slave’ is used.

Ruff O’Herne has commented on the term ‘comfort woman’.

The euphemism ‘comfort women’ is an insult, and I felt it was a pity that the media were also continually using these words. We were never ‘comfort women’. Comfort means something warm and soft, safe and friendly. It means tenderness. We were war-rape victims, enslaved and conscripted by the Japanese imperial forces.15

Ruff O’Herne is not only a survivor of this oppressive system, but has also been a vocal activist since the 1990s, participating in a transnational movement for redress.

Towards a transnational movement for redress

While commentators often refer to decades of ‘silence’, there was in fact widespread knowledge of this systematic military abuse in Japan and in the territories occupied by Japan during wartime. The encounters in the military brothels lived on in the memories of the military personnel and the enslaved women, not to mention all of the officers, doctors, bureaucrats, entrepreneurs, and pimps who managed the system. There are various casual references to the women in English-language texts of the early postwar years, often using the phrase ‘comfort girl’.16 Early postwar memoirs and literary works in Japanese mention the system and several Japanese-language books on the issue appeared in the 1970s.17 The issue was also discussed in feminist circles in Japan in the 1970s.18

Until the 1990s very few individual survivors had testified publicly. A Japanese woman, Mihara Yoshie (1921–1993), published an autobiography under the pseudonym ‘Shirota Suzuko’ in 1971 and she was interviewed on a radio program in Japan in 1986. In 1979, film-maker Yamatani Tetsuo made a documentary and published a book about a Korean survivor, Pae Pong-gi (1915–1991), who lived out the post-Second World War years in Okinawa. Yamatani’s book was entitled Okinawa no Harumoni (Halmoni [Grandmother] in Okinawa).19

On 14 August 1991, a Korean survivor, Kim Hak Sun (1924–1997), held a press conference to tell of her wartime experiences. This was the day before the anniversary of the end of the Asia-Pacific War on 15 August. She was soon joined by survivors from South Korea and other places. Dutch-Australian Jan Ruff O’Herne came forward in 1992 and published her abovementioned autobiography in 1994. Maria Rosa Henson (1927–1997) from the Philippines also came forward in 1992 and published her autobiography in 1996. In 1992, Taiwanese survivor, Liu Huang A-tao told her story.20 These were the beginnings of a transnational movement for redress which built on existing feminist networks in the region.21

In January 1992, then Japanese Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi (1919–2007) made an official visit to South Korea. On Wednesday 8 January1992, Kim Hak Sun, other survivors, and their supporters gathered in front of the Japanese Embassy in downtown Seoul. They demanded that the Japanese government make an official apology and provide compensation, chanting ‘Apologize!’ ‘Punish!’ ‘Compensate!’. There has been a Wednesday demonstration almost every week for over twenty five years. Survivors and their supporters hold placards in Japanese, Korean, or English. The elderly survivors sit on portable stools, facing the Japanese Embassy, surrounded by their younger supporters. They are often joined by international supporters visiting Seoul.22 Demonstrations have been carried out in other places, too, such as outside the Japanese Embassy in Manila. Taiwanese survivors and their supporters have demonstrated outside the Japanese representative office, the ‘Interchange Association’ in Taipei.23

Through their embodied presence in public space, the survivors assert their citizenship in the modern South Korean nation-state. Their first assertion of citizenship was in coming out publicly to tell their stories of wartime abuse, and to charge both the South Korean government and the Japanese government to do something about their situation. Their press conferences and testimonies brought their stories into public discourse. In their weekly attendance at the Wednesday demonstrations they make their demands visible in a public space on a Seoul street. Their placards in Korean, Japanese, and English show that they are addressing multiple audiences: the South Korean government and the South Korean public, the Japanese government and the Japanese public, and an international community which often communicates in the English language.

Activists have supported the survivors in various ways: recording, publishing, and translating collections of testimonies, supporting law suits, holding a people’s tribunal, fundraising, and volunteering to look after the everyday needs of the survivors. As recently as August 2017, 90-year old survivor Gil Won-Ok released an album of songs for fundraising purposes.24

The House of Sharing

From 1992, a group of elderly survivors shared a rented house in Seoul, known as the ‘House of Sharing’ (the Korean name ‘Nanum-ui Jip’ literally means ‘our house’). The House of Sharing moved to the outer suburbs of Seoul in 1995. Every Wednesday the survivors travel into downtown Seoul to take part in the weekly demonstration.25

The suburban complex combines a residence, a Buddhist temple, a museum, a gallery, and a memorial.26 The museum, established in 1998, has several rooms, described as the ‘Experience Room’, the ‘Indictment Room’, the ‘Cherish Room’, the ‘Record Room’, and the ‘Testimonial Room’. There is also a replica of a room from a wartime military brothel. Some of the possessions of Pae Pong-gi, the subject of Yamatani Tetsuo’s abovementioned documentary film and book, are displayed in a glass case. One wall has a series of terracotta tiles with the women’s handprints embedded in them. In the garden, there are tombstones and statues commemorating former residents who have passed away.

The House of Sharing website provides a history of the so-called ‘comfort women’ system, profiles of the survivors who share the House, information about the House, a collection of historical photographs, and a gallery of the women’s paintings.27 The paintings were completed by the survivors as a form of therapy and a form of testimony.28 Several of the paintings depict their younger selves, innocent young women wearing Korean ethnic dress (chima jeogori). Flowers often appear in the paintings, denoting nature and innocence. The House of Sharing was perhaps the first museum devoted to documenting the issue of militarized sexual violence. Several more have opened in recent years, as we shall see below.

The Women’s Tribunal

Once Kim Hak Sun and others came out with their stories of militarized sexual violence in the early 1990s, a transnational movement for redress developed.29 In each country historians and activists worked on documenting the women’s wartime experiences. These testimonies were collected, published, and translated into several languages. This collaboration between women in Japan, China, North and South Korea, and other countries culminated in the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery, held in Tokyo on 8–12 December 2000. This people’s tribunal had no legal force, although it followed international legal protocols. The judges had experience in the International Military Tribunals; professional lawyers prosecuted the case, and amici curiae (‘friends of the court’) presented defences on behalf of the Japanese government, which did not send any representatives to the hearing.30 Sixty four survivors attended – from South Korea, North Korea, the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, the Philippines, the Netherlands, Indonesia, East Timor, and Japan. Twenty survivors testified – some by video. Expert witnesses and former military personnel also testified.31 The Tribunal indicted the Emperor of Japan, ten high military officials, and the Japanese government for crimes against humanity.

The Women’s Tribunal drew on the documents of the International Military Tribunal of the Far East (the Tokyo Tribunal, 1946–1948) and other research carried out by historians, lawyers, and activists in several countries. The judgment, handed down one year later in December 2001, found that the Japanese Emperor, the Japanese government, and the other accused individuals were liable for criminal responsibility for crimes against humanity committed through the system of sexual slavery.32

Nicola Henry has argued that ‘the structure and practice of law is not only a site of memory preservation but also a medium for contested memory’.33 The Women’s Tribunal provided a forum for survivors to present their testimonies and contribute to a reworking of the historical memory which had been encoded in the original Tokyo Tribunal. In many ways the Women’s Tribunal could be seen as a massive transnational historical research project, with the aim of achieving historical justice for the survivors.34

When the Tribunal judgment was handed down one year later in December 2001, a small group of women of several nationalities staged a demonstration outside the hall in Tokyo where the judgment was announced. They were dressed in black clothes and covered their heads and faces with black veils, standing in silent vigil. No signs or placards announced the purpose of their vigil. Their demonstration adopted the format of an international group called ‘Women in Black’. The first such demonstrations were carried out by Israeli, Palestinian, and American women in 1988. Since then, such demonstrations have been carried out around the world, including protests against the war in the former Yugoslavia and vigils associated with the terrorist attacks in the USA in September 2001 and the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. By staging a vigil as ‘women in black’ these women were performing a visual affirmation of their links with women’s groups around the world and staking a claim to their use of public space.35

The ‘Women in Black’ vigil and the Wednesday demonstrations also have resonances with the demonstrations of the mothers and grandmothers of the ‘disappeared’ in Argentina. In April 1977, women in Buenos Aires occupied a central city square to draw attention to their sons and daughters who had been ‘disappeared’ by the military regime. This developed into a regular ritual of pacing around the Píramido de Mayo monument in the Plaza de Mayo square, carrying photographs of their ‘disappeared’ children and grandchildren (desaparecidos). It is estimated that the number of disappeared was around 30,000; the majority were young, between sixteen and thirty-five; around 30 per cent were women and around 3 per cent were pregnant. Two of the protesting mothers themselves were ‘disappeared’ after the protests started. After the democratization of Argentina in 1983, details of the systematic kidnapping, torture, and execution were revealed. Over thirty years later, the women still carry out their procession every Thursday at 3:00 p.m.36 As with the Wednesday demonstrations in Seoul, supporters come from around the world to witness their activism.

The Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace in Tokyo

One of the leaders of the movement in Japan for redress for survivors of militarized sexual abuse was journalist Matsui Yayori (1934–2002), longtime editorial staff member of the Asahi newspaper and a champion of the Women’s Tribunal. After Matsui’s death in 2002, her supporters worked to establish the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace (WAM), which opened in 2005. WAM is in the Waseda Hōshien complex in Tokyo, which houses several Christian civil society organizations. The Museum and the Asia-Japan Women’s Resource Centre build on the work of Matsui and the Asian Women’s Association which she co-founded.37

WAM has mounted a series of temporary exhibitions which have focused on the ‘Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal’, ‘The Tenth Anniversary of the Tribunal’, ‘Matsui Yayori’s Life and Work’, ‘The Comfort Women Issue A to Z’, ‘Korean Survivors in Japan’, ‘Testimonies from Former Soldiers’, ‘The Sexual Service Industry and Sexual Violence in Okinawa’, an exhibit directed at high school students, and reports on the issue from East Timor, China, Taiwan, Indonesia, and the Philippines.38 Until mid-2016, the exhibition was ‘Under the Glorious Guise of “Asian Liberation”: Indonesia and Sexual Violence under Japanese Military Occupation’. This partly drew on Comfort Women/Troost Meisjes, a collaboration between Dutch photographer Jan Banning and anthropologist Hilde Janssen, who travelled around Indonesia interviewing elderly survivors and photographing them.39 Banning’s photographs also featured in the Japanese photojournalism magazine, Days Japan in 2014.40 From mid-2016 to mid-2017 the exhibition was ‘Battlefield from Hell: Japanese Comfort Stations in Burma’.41 From mid-2017, the exhibition focused on ‘The Silence of the Japanese “Comfort Women”: Sexuality Managed by the State’.42

In each of the different museums in Seoul and Tokyo (and others to be discussed below), the implied viewer is different. In WAM in Tokyo, a group of activists are encouraging a largely Japanese audience to reflect on the contested history of their own country in wartime. The main language of the museum displays is Japanese, but with some English captions. The history of the Asia-Pacific War has been hotly contested in ‘history wars’ among historians within Japan, and there is also intense debate between historians in Japan, other parts of East Asia, North America, and Australia.43

One Thousand Wednesdays

To mark the 1,000th Wednesday demonstration on 14 December 2011 a commemorative statue was erected on the site of the demonstrations. Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung’s statue depicts a young woman seated on a chair, facing the Embassy, with an empty chair beside her. The plaque has inscriptions in Korean, Japanese, and English. The English inscription reads:

December 14, 2011 marks the 1000th Wednesday demonstration for the solution of Japanese military sexual slavery issue after its first rally on January 8, 1992 in front of the Japanese Embassy. This peace monument stands to commemorate the spirit and the deep history of the Wednesday demonstration.

|

Figure 4.2: The Peace Memorial, Seoul, February 2013; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

The figure depicted in the bronze statue wears Korean ethnic dress (chima jeogori); her hair is bobbed, suggesting that she is a young unmarried woman; and her fists are clenched on her lap. Her bare feet suggest vulnerability, or someone fleeing from danger. She stares steadfastly ahead, unsmiling. A small bird is perched on one shoulder. Behind her, at pavement level, is a mosaic, depicting the shadow of an old woman. The statue and its ‘shadow’ suggest the different stages of life of the survivor – the young woman before her ordeal, and the old woman who refuses to forget. The mosaic also includes a butterfly. The bird is an icon of peace and of escape, while the butterfly has spiritual connotations.44

The empty seat suggests those who are missing, but also provides a site for performative participation in the installation – demonstrators or visitors can have their photographs taken seated beside the statue of the young woman. Statues are often monumental, larger than life-size, standing on a tall pedestal, looking down on passers-by.45 The Seoul statue is at street level and is life-sized. Because the figure is seated, she seems approachable. There is, however, another reason why she is sitting. The fragile elderly women who have been demonstrating in front of the Japanese Embassy every week for over twenty five years generally sit there on portable stools rather than standing.

The statue does more than commemorate the suffering of the thousands and thousands of women who suffered from militarized sexual violence. It also commemorates the determination of those demonstrators and supporters who keep the issue alive. Placed at the very site where these demonstrations have now occurred for over twenty five years, the statue is a form of petition to the Japanese government and its diplomatic representatives. At times other than Wednesday lunchtimes, it is an avatar for the elderly demonstrators.

At one of the demontrations in February 2013, it had been snowing in the few days before the Wednesday demonstration and there was still some snow on the ground. Supporters had dressed the statue in a warm winter coat, woollen hat with ear muffs, a scarf, a long red, embroidered winter skirt, and socks. On the seat next to the statue were cute stuffed toys; behind her was a row of colourful potted plants. By dressing the statue in protection against the cold, the supporters symbolically expressed their concern for the halmoni (‘grandmothers’) who have survived and their care for the spirits of the countless women who did not survive.

By the time the demonstration started on this day, two busloads of police were in the street, the number of police roughly matching the number of demonstrators. The demonstrators were a mixture of young and old, male and female. Journalists, photographers, and media representatives joined the crowd. Behind the site of the Wednesday demonstration, there was a series of panels, commenting on other contentious issues such as the Dokdo/Takeshima islands which are under dispute between Japan and South Korea. The statue has been replicated in the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum.

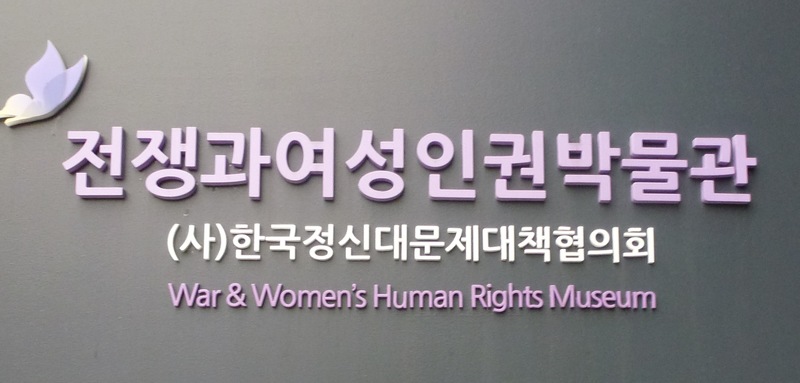

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum in Seoul

The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum was opened in May 2012, designed by Wise Architecture, and founded and maintained by the Korean Council for Women Drafted into Military Sexual Slavery.46 It is hidden away in a cul-de-sac in a residential neighborhood west of the city centre, surrounded by houses, schools, churches, and shops. Its location is much more accessible than the House of Sharing in the outer suburbs of Seoul. The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum is in a house which has been renovated and extended, and is therefore in proportion to the surrounding streetscape. The building is clad in charcoal-coloured bricks. Signs in Korean and English, decorated with a butterfly logo, indicate that this is The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum.47

|

Figure 4.3: The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum, February 2013; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

Visitors enter from a small door at street level. After purchasing tickets and picking up an audio guide, the tour starts downstairs. A small dark room recreates the feeling of the prison-like conditions the women were subjected to in the wartime brothels. Testimonies are replayed and visuals are projected onto the walls of the room. Visitors then walk upstairs. The walls of the staircase are lined with photographs and messages from the survivors. There is a balcony with an outside wall made of the same charcoal bricks as the external walls of the museum. The names and photographs of women who have passed away are affixed to the bricks. The spaces in the lattice make it possible to place a candle or a flower. The open lattice of the brickwork allows visitors to look out at the surrounding residential area, reconnecting the museum with the city.48

|

Figure 4.4: The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum Balcony, February 2013; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

In the exhibition space wall panels explain the history of the enforced military prostitution/military sexual slavery system. Here, there is a replica of the bronze statue that sits across from the Japanese Embassy in central Seoul. The statue itself is identical to the one in central Seoul, but without the plaque or the mosaic of the older woman’s shadow. This statue, too, has an empty seat beside it. It faces a video screen running footage of the Wednesday demonstrations, a virtual suggestion of the location and context of the original statue. Rather than a plaque, the museum as a whole provides historical context on the wartime enforced military prostitution/military sexual slavery system, the campaigns for redress, and the Wednesday demonstrations.

|

Figure 4.5: The Peace Monument in the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum, February 2013; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

Because the Peace Monument is cast in bronze, it can be reproduced. The War and Women’s Human Rights Museum sells replicas of various sizes, and various communities have made plans to install replicas.49

|

Figure 4.6: Small Replica of the Peace Statue, December 2016; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

Glendale, California

Another replica of the peace monument has been installed in Glendale, California.50 The statue, chair, and platform are identical to the original. Its plaque bears the caption, ‘I was a sex slave of the Japanese military’, and provides an explanation of the meanings of the shadow of the old woman, the bird, and the butterfly.

Peace Monument

In memory of more than 200,000 Asian and Dutch women who were removed from their homes to Korea, China, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, East Timor and Indonesia to be coerced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Armed Forces of Japan between 1932 and 1945.

And in celebration of ‘Comfort Women Day’ by the City of Glendale on July 30, 2012, and of passing the House Resolution 121 by the United States Congress on July 30, 2007, urging the Japanese government to accept historical responsibility for these crimes.

It is our sincere hope that these unconscionable violations of human rights shall never recur.

July 30, 2013

While the plaque of the original Seoul statue has text in Japanese, Korean, and English, the Glendale plaque is in English only. The original statue commemorates the activism of those who participate in the Wednesday demonstration, while the Glendale statue commemorates the ‘more than 200,000 Asian and Dutch women who were removed from their homes to Korea, China, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, East Timor and Indonesia to be coerced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Armed Forces of Japan between 1932 and 1945’. The Dutch women are identified by nationality, while ‘Asian’ seems to refer to an ethnic category which transcends any one national identification. Nevertheless, this is an acknowledgement that it was not only Korean women who were abused under this system. Indeed, because of the shifting geopolitics in the region after the end of the Second World War and successive waves of decolonization, identifying the nationality of any individual can be complicated, depending on whether one is referring to colonial regimes before and after 1945, the period of Japanese occupation, or the postcolonial nation-states.51

The plaque refers to the local situation in Glendale, where Asian American and Asian diasporic communities led the campaign for an acknowledgment of the issue, leading to the announcement of ‘Comfort Women Day’ by the City of Glendale on 30 July 2012. The plaque also acknowledges House Resolution 121 of the United States Congress on 30 July 2007, which called on the Japanese government to apologize and provide compensation.52 There was a similar campaign in Australia, with a few local councils passing resolutions, but none at the state or national government level.53 In each of these places, diasporic communities played an important role.

|

Figure 4.7: The Peace Memorial, Glendale, May 2014; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

The Glendale statue is in a park in front of the local community centre and public library, facing a busy main road. On a sunny spring day in May 2014, the features of the statue were cast into relief by the bright sunlight. As in Seoul, supporters had offered colourful potted plants, but there was no need for the affective touches of scarves and warm clothing seen on the Seoul statue on a cold winter’s day.

In Glendale, the addressee of the statue’s petition is less clear than in Seoul. She is no longer clearly addressing the Japanese government through her accusatory gaze at the Japanese Embassy. She is perhaps addressing the local Glendale community, the wider US public, or an international Anglophone community.

The Glendale statue has stimulated controversy, with Japanese historical denialists putting pressure on the local government for the removal of the statue. The US District Court decided that the statue could stay.54 A similar controversy has been seen in Strathfield, in the Western suburbs of Sydney. Members of the Korean-Australian community were initially successful in convincing Strathfield Council to approve a memorial. After pressure from conservative denialists from Japan, however, Strathfield decided not to go ahead.55 Currently a replica of the Seoul statue is housed in a community centre in a church in Ashfield, an inner Western suburb of Sydney.56 In Germany, there was a controversy when the city of Freiburg planned to erect a statue, a gift from Suwon, their sister city in South Korea. After pressure from Matsuyama, their sister city in Japan, they decided not to proceed.57 Eventually the town of Wiesunt hosted a replica, the first one in Europe.58 These controversies demonstrate that it is not only the survivors and their supporters who have forged transnational links. The conservative denialists also operate across national borders. Historians who write about issues related to the Asia-Pacific War in East Asia regularly receive unsolicited denialist propaganda in the mail and on e-mail.

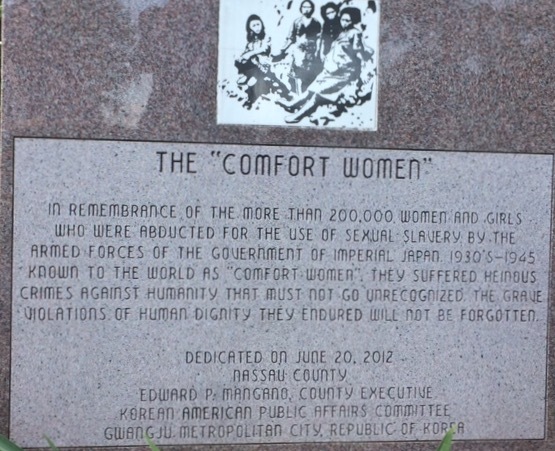

Other Asian American communities have installed commemorative plaques, often outside local community centres, and others are planned. The memorial plaque in Eisenhower Park, Long Island reproduces a well-known photograph of some survivors found at the end of the Second World War in China.59

|

Figure 4.8: Memorial plaque in the Veterans Memorial in Eisenhower Park, Long Island, New York, May 2017, photograph by Katharine McGregor, reproduced with permission. |

Replicas of the Seoul Peace Monument have been installed in other North American cities. There is a commemorative plaque in Manila and one memorial in Chiba, outside Tokyo.60 In August 2017 it was reported that there were dozens of such statues in South Korea, the US, Canada, Australia, and China. Five Seoul city buses carried similar statues in commemoration of the anniversary of the end of the Second World War in August 2017. The seated posture of the statue made it easy to install it on a bus seat, sitting in silent vigil alongside the commuters. August 15 is the date when Japan surrendered to the Allies, but Korea commemorates this date as the liberation of the country from colonization by the Japanese.61 In 2012 at an Asian Solidarity Conference in Taipei it was suggested that the day before this – 14 August – should be named ‘International Memorial Day for Comfort Women’. This is also the anniversary of Kim Hak Sun’s press conference in 1991 which had been one impetus for the movement for redress.62 Since 2012, civil society organisations have marked the day.

The Geopolitics of Commemoration

Another iteration of the Peace Memorial in Seoul is in a park some remove from the city centre. In this version, the statue of a young woman in Korean ethnic dress is joined by the statue of a young woman in Chinese ethnic dress, sculpted by a Chinese artist, Pan Yiqun, and supported by a Chinese American film-maker, Leo Shi Young.63 There is another chair set aside for future visitors and the potential for future statues to be added. This perhaps suggests that the original statue was being read as referring specifically to the Korean women, rather than a more universal figure of a young woman. This instability is apparent in the different descriptions attached to the statues in different locations, as noted above.

The juxtaposition of the Chinese and Korean statues can perhaps be read as a demonstration of transnational solidarity at the level of civil society, staged at a strategic moment just before Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s official visit with South Korean President Park Geun-hye in October 2015. It could also be argued, however, that the two statues were ‘re-nationalised’ as Korean and Chinese, united in opposition to Japan.64 While civil society forged links between Korean and Chinese activists and artists, there was a different dynamic at the official level.

In December 2015, two months after Abe’s meeting with Park, the South Korean and Japanese governments issued a joint communiqué. The Japanese Foreign Minister, Kishida Fumio, stated that the Prime Minister, Abe Shinzō, ‘expresses anew his most sincere apologies and remorse to all the women who underwent immeasurable and painful experiences and suffered incurable physical and psychological wounds as comfort women’. Kishida stated that the Japanese government would provide the South Korean government with funds for the establishment of a fund for the care of the survivors and that ‘this issue is resolved finally and irreversibly’. The statement was met with hostility by the South Korean survivors, who felt they should have been consulted before any government-to-government agreement was reached, a basic principle of restorative justice. Then South Korean Foreign Minister, Yun Byung Se, confirmed that the issue was ‘resolved finally and irreversibly’ and that the Republic of Korea and Japan would ‘refrain from accusing or criticizing each other regarding this issue in the international community’. The statue was not mentioned in the Japanese statement at this stage, but the South Korean statement included an acknowledgment that ‘the Government of Japan is concerned about the statue built in front of the Embassy of Japan in Seoul’ and that the South Korean government would ‘strive to solve this issue in an agreeable manner through taking measures such as consulting with related organizations about possible ways of addressing this issue’.65 The agreement also returned the issue to a bilateral one between Japan and South Korea. Survivors from other countries demanded similar recognition. It was clear, however, that the Japan-ROK joint communiqué was a matter of geopolitics, an attempt to forge a closer alliance between the governments of the US, Japan, and South Korea against China.66

In December 2016 a community group in the Southern port city of Busan placed a statue in front of the local Japanese Consulate, hoping to make it a permanent installation. It was one year on from the unpopular bilateral agreement between the ROK and Japan. Prime Minister Abe called for the statue’s removal and recalled the Ambassador from Seoul and the Consul from Busan.67

In December 2016, Park Geun-hye – who had engineered the agreement with Abe Shinzō –was impeached on corruption charges, and in March 2017 the Constitutional Court voted unanimously to remove her from the Presidency. A new President, Moon Jae-in, took office on 10 May 2017. Moon has brought the 2015 Japan-ROK agreement into question. He has stated that he will institute a national day of commemoration, establish an institute to research the issue and build a museum, activities to be spearheaded by the Ministry of Gender and Equality.68 The statues continue to be attributed geopolitical significance in the region.

Commemoration in China

In Shanghai, two professors at Shanghai Normal University, Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei, maintain the Chinese ‘Comfort Women’ Research Centre. In Shanghai there is an extant building which once housed a so-called ‘comfort station’. It is currently a residential building but many, like Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei, would like to see it transformed into a memorial.69

In December 2015, a memorial to the so-called ‘comfort women’ opened in Nanjing.70 The building has been identified as the site of a former military ‘brothel’. In front of the museum is a statue which recreates in three-dimensional form the scene of the abovementioned well-known photograph of the survivors at the end of the Asia-Pacific War.71

|

Figure 4.9: Nanjing Liji Lane Former Comfort Station Exhibition Hall, June 2017, photograph by Antonia Finnane, reproduced with permission. |

An exterior wall is covered with huge black and white photographs of some of the elderly survivors. Inside there are wall panels explaining the history of the system, historical photographs, and more recent photographs of the survivors. Explanations are in Chinese and English.

The name of the memorial is the Nanjing Liji Lane Former Comfort Station Exhibition Hall. Memorials and museums in other countries avoid using terms like ‘comfort women’ or ‘comfort station’ in their names, preferring to refer to ‘Women in War and Peace’, ‘War and Women’s Human Rights’ or, as we shall see below, ‘Grandmothers’. China’s Xinhua news agency, in its English-language reports on the issue, unapologetically uses the term ‘comfort women’.72

The location of the memorial in Nanjing takes on further resonance as this city was the site of the Nanjing Massacre in 1937 (also known as the ‘Rape of Nanjing’). Nanjing houses a massive memorial to the Massacre and various other historical sites. Statues at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial commemorate the victims of massacre, torture, and sexual violence. There is also a statue of controversial Chinese-American author Iris Chang (1968–2004), who campaigned to keep the history of the Nanjing Massacre in the public eye.73

|

Figure 4.10: Statue of Iris Chang, Nanjing, August 2015; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

On the Xinhuanet news agency website, the article about the opening of the Nanjing Liji Lane memorial is grouped with a series of articles commemorating the 70th anniversary of the end of hostilities in 1945. In the US, Europe, and Anglophone countries, it is usual to refer to the ‘Second World War’ (from 1939 to 1945). Historians working on East Asia, however, often refer to the ‘Asia-Pacific War’, recognizing that all-out war between Japan and China commenced in 1937. Historians in Japan often refer to the ‘Fifteen Years War’, counting fifteen years from the Manchurian Incident of 1931 to the end of the war in 1945. In China, much of 2015 was taken up with commemoration of what they call ‘The 70th Anniversary of Victory of Chinese People’s Resistance against Japanese Agression and World Anti-Fascist War’.74 A special section of the Xinhuanet website is devoted to what they call the ‘comfort women album’.75 In 2015, the Chinese media was full of stories about the war: dramatizations of important events, documentaries, and news stories about elderly survivors. The commemorations culminated in a huge military parade in Beijing on 3 September 2015. These commemorations are inseparable from ongoing geopolitical tensions between Japan and its neighbouring countries in East Asia.

The Grandmothers’ Museum in Taipei

In December 2016 a new museum was opened in Taipei, under the auspices of the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation. This organization provides support for the survivors and has been planning the museum for the last decade.76 A commemorative plaque was unveiled on the site on International Women’s Day 2016 and the museum opened on 10 December 2016 (Human Rights Day, the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948).77 It is called the ‘Ama Museum’ or ‘Grandmothers’ Museum’. In Taiwan, too, the survivors are referred to respectfully as ‘grandmothers’.

|

Figure 4.11: The Ama Museum, Taipei, December 2016; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

The Ama Museum is in a bustling shopping street called Dihua Street in a renovated building. The buildings in this area generally date to the mid-nineteenth century or the Japanese colonial period (1895–1945). The ground floor is a trendy café which is open to the public. On entering the museum, one walks along a corridor which has a gallery of photographs of the ‘grandmothers’ at different stages of their lives.

|

Figure 4.12: Gallery of Portraits of Ama, December 2016; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

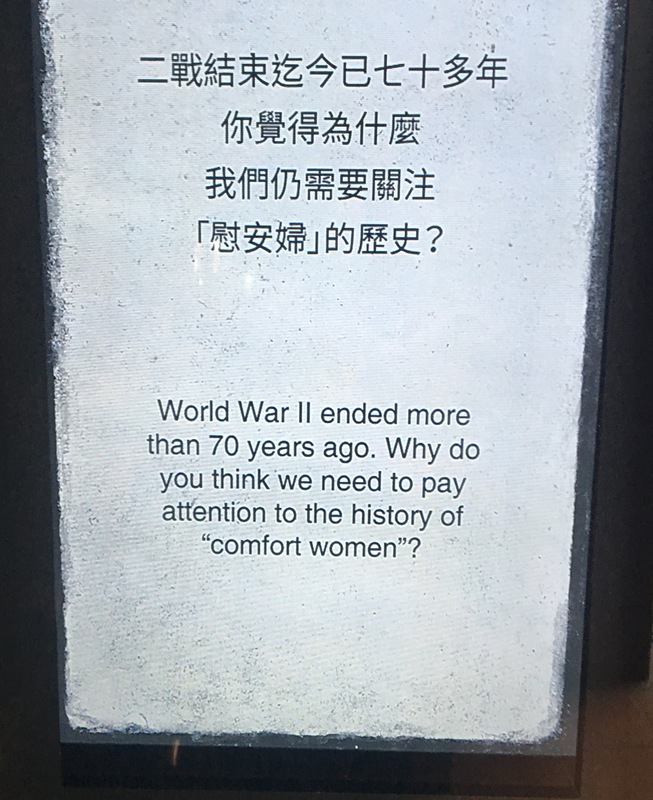

The Museum has a combination of historical documentation, profiles of survivors, artistic responses, and interactive installations. As one moves from the gallery of portraits to the museum proper, a series of questions invite reflection on the part of the museum visitor.

World War II ended more than 70 years ago. Why do you think we need to pay attention to the ‘comfort women’ issue?

If you were a loyal soldier and discovered your country had established a system of sexual slavery for the national military, what action would you take?

After the war, ‘comfort women’ survivors returned to Taiwan and found themselves the targets of discrimination and prejudice. If you were their family member, what would be your attitude toward this mistreatment?

The ‘comfort women’ system during World War II left the victims with both physical and mental scars. What do you think the Japanese government should do to face up to the historical mistake they made?

Issues regarding ‘comfort women’ often become reduced to the question of whether a person is ‘anti-Japanese’ or ‘pro-Japanese’. Do you believe that protesting against the Japanese government regarding the ‘comfort women’ system makes a person anti-Japanese?

While these questions are presented in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and English, captions in other parts of the museum are generally in Chinese and English. As of December 2016, brochures were available in Chinese, Japanese, and English. Japanese-language texts address the perpetrator nation; Chinese texts address Taiwanese and Chinese audiences; while English texts address an international audience.

|

Figure 4.13: Questions addressed to museum visitors, Ama Museum, December 2016; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

Inside the museum, historical background is provided in informative historical panels, video testimonials, and artefacts of the movement for redress, such as a poster for the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery, where some Taiwanese survivors testified. Each of three panels celebrates the life of one of the survivors and several exhibits celebrate the therapeutic arts projects which were deployed as a way to heal the survivors’ psyches (as was also the case in South Korea). Memory baskets hold meaningful objects from each individual’s life. In front of each panel is a life story book of her life. In other interactive installations, visitors are invited to write postcards to the survivors or to the Japanese government.

|

Figure 4.14: Postcards from the Ama Museum, December 2016; photograph by Vera Mackie. |

In addition to the informative sections, there are several artistic interventions. A major motif of the museum is the reed, signifying resilience. The ‘Song of the Reed’ commemorates the resilience of the survivors.78 A corridor leading from one gallery to another is called the ‘Song of the Reed Walk’, described as ‘a memorial corridor dedicated to survivors’. Transparent cylinders and metal cylinders, evoking the shape of the reed, are suspended from the ceiling. Fifty-nine of the metal cylinders take the form of little flashlights. Each projects the name of a survivor on to the floor, or on to the visitor’s hand if placed under the lamp. In another part of the museum, survivors’ names are carved into a black metal screen. The museum invites contemplation through its provocative question panels, active participation through its interactive displays, and emotional engagement through the artistic displays and installations.

The issue of militarized sexual violence emerged as an international feminist issue in the 1970s although there had been widespread knowledge of various forms of militarized sexual abuse well before then. By the 1990s, when the movement for redress had become a global one, demonstrators had transformed themselves from figures of suffering to political actors. They claimed public space in order to petition for their cause. In the 1990s, Cynthia Enloe reflected on the absences from most war museums of any reflection on sexual behaviour in wartime.79 While this is still to some extent true in mainstream war museums and memorials, recent decades have seen museums and memorials dedicated to the issue of wartime sexual violence. These museums do not simply document suffering. They also document the citizenship and activism of the ‘grandmothers’ who have fought for justice. A feature of these recent museums and memorials is that they also engage in an affective politics, mobilizing the emotions of the viewer in order to stimulate further activism.

***

This is an edited and abridged extract of Sharon Crozier-De Rosa and Vera Mackie, Remembering Women’s Activism (Oxford: Routledge, 2019), pp. 161–199; reproduced with permission from Routledge. Also available here.

***

Related articles in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus:

Thomas J. Ward, The Comfort Women Controversy – Lessons from Taiwan

Alexis Dudden, Korean Americans Enter the Historical Memory Wars on Behalf of the Comfort Women

Hiro Saito, The History Problem: The Politics of War Commemoration in East Asia

Katharine McGregor, Transnational and Japanese Activism on Behalf of Indonesian and Dutch Victims of Enforced Military Prostitution During World War II

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, You Don’t Want to Know About the Girls? The ‘Comfort Women’, the Japanese Military and Allied Forces in the Asia-Pacific War

Wada Haruki, The Comfort Women, the Asian Women’s Fund and the Digital Museum

***

Notes

Vera Mackie, ‘Militarized Sexual Violence and Campaigns for Redress’, in The Routledge History of Human Rights, eds Jean Quatert and Lora Wildenthal (Oxford: Routledge, in press).

The building which houses the memorial and archive was completed in 1941. Before the completion of the permanent building, the ‘Australian War Museum’ exhibited in Melbourne’s Exhibition Building from 1922 to 1925, and in Sydney from 1925 to 1935. Australian War Memorial, ‘Origins of the Australian War Memorial’, undated (Last accessed 30 May 2014).

Australian War Memorial, ‘About the Australian War Memorial’, undated (Last accessed 30 May 2014).

On the establishment of the Australian War Memorial, see: Australian War Memorial, ‘Origins of the Australian War Memorial’.

Vera Mackie, ‘Gender, Geopolitics and Gaps in the Records: Women Glimpsed in the Military Archives’, in Sources and Methods in Histories of Colonialism: Approaching the Imperial Archive, eds Kirsty Reid and Fiona Paisley (Oxford: Routledge, 2017), pp. 129–153; Vera Mackie, ‘Remembering Bellona: Gendered Allegories in the Australian War Memorial’, Vida (November 2016) (Last accessed 23 January 2016).

In the 1970s, the Australian War Memorial was one focus for demonstrations commemorating ‘Women Raped in War. Such campaigns were a feature of the women’s liberation movements in Anglophone countries in the 1970s. See detailed discussion in Sharon Crozier-De Rosa and Vera Mackie, Remembering Women’s Activism (Oxford: Routledge, 2019), pp. 162–165.

The exhibition ‘Reality in Flames: Modern Australian Art and the Second World War’ at the Australian War Memorial in 2016 included a painting from Albert Tucker’s ‘Images of Modern Evil’ series, which unfavorably depicted Australian women who had liaisons with US soldiers stationed in Melbourne.

Australian War Memorial Exhibition, Allies in Adversity: Australia and the Dutch in the Pacific War (Last accessed 10 April 2016).

Portrait of Jan O’Herne, taken at [Bandung], Java, shortly before the Japanese invasion in March 1942. Australian War Memorial, P02652.001. This photograph is also displayed in the Changi museum in Singapore in a display on women and war, even though O’Herne had no direct connection with Singapore or Changi.

Handkerchief embroidered with signatures of Dutch ‘Comfort Women’ at the ‘House of the Seven Seas’, Semarang, Java. Australian War Memorial, REL26396. (last accessed 30 March 2018).

Embroidered signature apron: Jan O’Herne and Dutch women at Kamp 1A Ambarawa Internment Camp, Java. Australian War Memorial. REL26397.

Ralph E. Lapp, The Voyage of the Lucky Dragon: The True Story of the Japanese Fishermen who were the First Victims of the H-Bomb (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1957), p. 80 and p. 85; Anthony H. Johns, ‘Towards a Modern Indonesian Literature’, Meanjin (December 1960), p. 385; John Ashmead, The Mountain and the Feather (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961), p. 166, p. 205, and p. 293

As Heinz-Erik Ropers has noted, these were not obscure titles; many were mass market paperback books. Heinz-Erik Ropers, ‘Mutable History: Japanese Language Historiographies of Wartime Korean Enforced Labor and Enforced Military Prostitution, 1965–2008’, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Melbourne, 2011, p. 150; Tomita Kunihiko, ed. Senjō Ianfu [Battlefield Comfort Women] (Tokyo: Fuji Shobō, 1953); Shirota Suzuko, Mariya no Sanka [Maria’s Hymn] (Tokyo: Nihon Kirisuto Kyō Shuppankyoku, 1971); Senda Kakō, Jūgun Ianfu: ‘Koe naki onna’ Hachiman nin no kokuhatsu [Military Comfort Women: The Grievances of 80,000 ‘Voiceless Women’] (Tokyo: Futabasha, 1973); Hirota Kazuko. Shōgen kiroku jūgun ianfu, kangofu: Senjō ni ikita onna no dōkoku [Testimonies and Records of Military Comfort Women and Nurses: Lamentations of Women Who Went to the Battlefront] (Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha, 1975); Kim, Il-Myon, Tennō no Guntai to Chōsenjin Ianfu [The Emperor’s Army and Korean Comfort Women] (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1976); Yamatani Tetsuo, Okinawa no Harumoni: Dai Nihon Baishun Shi [An Old Woman in Okinawa: A History of Prostitution in Greater Japan] (Tokyo: Banseisha, 1979). On early post-Second World War knowledge of the system, see Kanō Mikiyo, ‘The Problem with the “Comfort Women Problem”’, Ampo: Japan–Asia Quarterly Review, Vol. 24, No 2 (1993), p. 42; Eleanor Kerkham, ‘Pleading for the Body: Tamura Taijirō’s 1947 Korean Comfort Woman Story, Biography of a Prostitute’, in War,Occupation, and Creativity: Japan and East Asia, 1920–1960, eds. Marlene J. Mayo, Thomas J. Rimer, and H. Eleanor Kerkham (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2001).

Tanaka Mitsu, ‘Josei kaihō e no kojinteki shiten’ [An Individualistic Point of View on Women’s Liberation] (August 1970) in Shiryō Nihon Ūman Ribu-shi [Historical Records of Japanese Women’s Liberation History] eds Mizoguchi Akiyo, Saeki Yōko, and Miki Sōko (Kyoto: Shōkadō, 1992), Vol. 1, pp. 196–200.

Shirota, Mariya no Sanka; Soh, The Comfort Women, p. 198; Yamatani, Okinawa no Harumoni; Ropers, ‘Mutable History’, p. 194.

Yang, ‘Revisiting the Issue of Korean “Military Comfort Women”, p. 68, note 2; Maria Rosa Henson, Comfort Woman: Slave of Destiny (Manila: Philippine Centre for Investigative Journalism, 1996); Ruff O’Herne, Fifty Years of Silence; Graceia Lai, Wu Hui-ling and Yu, Ju-fen, Silent Scars: History of Sexual Slavery by the Japanese Military (Taipei, Shang Zhou Chuban, 2005), translated by Sheng-mei Ma; Floyd Whaley, ‘In Philippines, World War II’s Lesser-Known Sex Slaves Speak Out’, The New York Times (29 January 2016) (Last accessed 31 January 2016).

On the emergence of the movement, see: Vera Mackie, ‘Sexual Violence, Silence, and Human Rights Discourse: The Emergence of the Military Prostitution Issue’, in Human Rights and Gender Politics: Asia-Pacific Perspectives, eds Anne Marie Hilsdon et al. (London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 37–59; Vera Mackie, ‘The Language of Transnationality, Globalisation and Feminism’, International Feminist Journal of Politics Vol. 3, No. 2 (2001), pp. 180–206;Vera Mackie, ‘Shifting the Axis: Feminism and the Transnational Imaginary’, in State/Nation/Transnation, eds Brenda Yeoh et al. (London: Routledge, 2004); Vera Mackie, ‘In Search of Innocence: Feminist Historians Debate the Legacy of Wartime Japan’, Australian Feminist Studies, Vol. 20, No. 47 (2005), pp. 207–217; Mackie, ‘Militarized Sexual Violence and Campaigns for Redress’.

Soh, ‘The Korean “Comfort Women” Movement for Redress’, p. 1235; Kim Tae-ick, ‘Former “Comfort Women” hold 1,000th Protest at Japanese Embassy’, Chosun Ilbo [Chosun Daily] (14 December 2011) (Last accessed 9 November 2015). Kim reports that they skipped a protest only once, during the Kobe earthquake of 1995, and that they marked the Fukushima disaster of March 2011 by holding their protest in silence. On the Wednesday demonstration, see Vera Mackie, ‘One Thousand Wednesdays: Transnational Activism from Seoul to Glendale’, in Women’s Activism and ‘Second Wave’ Feminism: Transnational Histories, eds Barbara Molony and Jennifer Nelson (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), pp. 249–271.

Ronron Calunsod, ‘Former “Comfort Women”, Lefists Protest Growing Philippines–Japan Military Ties’, Japan Times (30 June 2015) (Last accessed 30 November 2015); ‘Former Sex Slaves Protest in Manila during Emperor Visit’, CCTV America (Last accessed 31 January 2016); Lai, et al. Silent Scars, p. 100.

Keith Howard ed. True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women (London: Cassell, 1995), translated by Young Joo Lee; Dai Sil Kim–Gibson, Silence Broken: Korean Comfort Women (Parkersburg, Iowa: Mid–Prairie Books, 1999); Sangmie Choi Schellstede ed. Comfort Women Speak: Testimony by Sex Slaves of the Japanese Military (New York and London: Holmes and Meier, 2000); Lai et al., Silent Scars; Chyung Eun-ju and Park Si-Soo, ‘Ex-Comfort Woman Becomes Singer at 90’, The Korea Times (10 August 2017) (Last accessed 13 August 2017).

Similar support activities are carried out for survivors in other countries, although there are no doubt countless others who have not come forward with their stories of wartime abuse. Survivors in the Philippines are supported by Lilas Pilipinas (League of Filipino Grandmothers) and Friends of Lolas; see ‘Friends of Lolas’ (Last accessed 30 November 2015); ‘Lolas’ House’. IMDiversity. 20 October 2012 (Last accessed 30 November 2015). Survivors in Taiwan are supported by the Taiwan Women’s Rescue Foundation; see Laurie Underwood. ‘Painful Memories’, Taiwan Today (1 October 1995) (Last accessed 6 December 2015). For activities in support of the Indonesian survivors, see McGregor, ‘Emotions and Activism’; for support of Chinese survivors, see Hornby, ‘China’s “Comfort Women”’.

The survivors were taught by artist Lee Gyeung-shin. Kim, ‘Filming the Queerness of Comfort Women’, p. 28; Hyunji Kwon, ‘The Paintings of Korean Comfort Woman Duk-kyung Kang: Postcolonial and Declonial Aesthetics for Colonized Bodies’ Feminist Studies, Vol. 43, No 3 (2017): pp. 571–609.

Several of the judges had been associated with the International War Crimes Tribunals in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda, where the issue of sexual violence in wartime was explicitly raised. Rumi Sakamoto, ‘The Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery: A Legal and Feminist Approach to the “Comfort Women” Issue’, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 3, No 1 (June 2001), p. 55.

Kim, ‘Global Civil Society Remakes History’, p. 612. A one-day public hearing was also held at the Women’s Caucus for Gender Justice in New York on 11 December, where fifteen survivors of militarized sexual violence from around the world testified.

Gabrielle Kirk McDonald et al, ‘The Judgement of the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal for the Trial of Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery’, Case No PT-2000-1-T, The Hague, 4 December 2001 (corrected 31 January 2002) (Last accessed 7 June 2014).

Nicola Henry, ‘Memory of an Injustice: The “Comfort Women” and the Legacy of the Tokyo Trial’, Asian Studies Review, Vol. 37, No. 3 (2013), p. 363.

Vera Mackie, ‘Gender and Modernity in Japan’s Long Twentieth Century’, Journal of Women’s History, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Fall 2013), p. 79; Vera Mackie, ‘Whispering, Writing and Working across Borders: Practising Transnational History in East Asia’, in Rethinking Japanese Studies: Eurocentrism and the Asia-Pacific Region, eds Kaori Okano and Yoshio Sugimoto (Oxford: Routledge, 2018), pp. 152–166.

Rita Arditti, ‘The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Struggle against Impunity in Argentina’, Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2002), p. 20.

On the Asian Women’s Association and its journal, Asian Women’s Liberation, see Vera Mackie, Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 202–203. Ajia No Onnatachi no Kai (Asian Women’s Association) is now called the Ajia Josei Shiryō Sentā (Asia-Japan Women’s Resource Centre) and their journal has changed its name from Ajia to Josei Kaihō (Asian Women’s Liberation) to Onnatachi no Nijūisseiki (Women’s Asia 21).

Jan Banning and Hilde Janssen, Comfort Women/Troost Meisjes (Utrecht: Ipso Facto, 2010). On Banning and Janssen’s project, see Katharine McGregor and Vera Mackie, ‘Transcultural Memory and the Troostmeisjes/Comfort Women Photographic Project’, History & Memory. Vol. 30, No 1 (Spring/Summer 2018), pp 116-150.

Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace (2013–2017), ‘Exhibition: Battlefield from Hell: Japanese Comfort Stations in Burma’ (Last accessed 3 January 2017).

Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace (2017), ‘Exhibition: The Silence of the Japanese “Comfort Women”: Sexuality Managed by the State’ (Last accessed 25 September 2017).

On the connotations of the butterfly in Korean culture, see Choi Goun, ‘”Flowers and Butterflies – In Perfect Harmony” Exhibition: Enduring Symbols of Korea’s Traditional Culture’, Korea Foundation Newsletter, Vol. 19, No 9 (September 2010) (Last accessed 26 December 2017).

Compare this with the statue of Qiu Jin, Figure 2.13 in Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie, Remembering Women’s Activism, p. 111.

The project team at Wise Architecture included Sook Hee Chun, Young Chul Jang, Bokki Lee, Jiyoung Park, Kuhyeon Kwon and Aram Yun, ‘Seoul House Becomes Museum Highlighting the Plight of Second World War “Comfort Women”’, dezeen magazine (20 March 2015) (Last accessed 31 January 2016); Hee-Jung Serenity Joo, ‘Comfort Women in Human Rights Discourse: Fetishized Testimonies, Small Museums, and the Politics of Thin Description’, Review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies, Vol. 37, Nos. 2–3 (2015), p. 172. The Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery (Chongsindae munje taech’aek hyopuhoe) was founded in November 1990 as an umbrella group for several feminist organizations in South Korea. It was also allied with feminist groups in Japan, Taiwan, Burma, the Philippines, and North Korea. The Council has been at the forefront of research on the issue and in campaigns for redress for Korean survivors. In Japan, the Asian Women’s Association and the Violence Against Women in War Network (VAWW-Net-Japan) have been important. Yang, Hyunah, ‘Revisiting the Issue of Korean “Military Comfort Women”: The Question of Truth and Positionality’, positions: east asia cultures critique, Vol. 5, No 1 (Spring 1997), pp. 51–71.

The butterfly is regularly used as a logo for political campaigns on this issue. See the ‘Butterfly Fund’, established by the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum in support of victims of sexual violence (Last accessed 31 January 2016).

Hee-Jung Joo argues that the gaps between the bricks signify the gaps in knowledge about the vast numbers of women who suffered under the system. Joo, ‘Comfort Women in Human Rights Discourse’, p. 182, note 7.

On one of the smaller replicas, see Vera Mackie, ‘The Grandmother and the Girl’, Vida (December 2016) (Last accessed 12 August 2017).

The Glendale monument was donated by the Korean American Forum of California. Rafu Shimpo, ‘Fullerton Council Approves “Comfort Women” Resolution’ (24 August 2014) (Last accessed 24 October 2015).

These shifting regimes before and after 1945 are another reason why it has been so difficult to document the enforced military prostitution system. Some Dutch war trial records, for example, are still closed. In what are present-day Indonesia and Timor-Leste, administration has shifted between the Dutch East Indies, Portuguese Timor, the Japanese Occupation, the Australian-administered period of surrender, reversion to Dutch and Portuguese control, the independent nation-state of Indonesia (including West Timor), Indonesian-Occupied East Timor, and the independent nation-state of Timor-Leste. For the difficulties of tracing the fates of individual women through these different administrative regimes, see Mackie, ‘Gender, Geopolitics and Gaps in the Records’, passim.

House Resolution 121, as amended, ‘[e]xpresses the sense of the House of Representatives that the government of Japan should: (1) formally acknowledge, apologize, and accept historical responsibility for its Imperial Armed Force’s coercion of young women into sexual slavery (comfort women) during its colonial and wartime occupation of Asia and the Pacific Islands from the 1930s through the duration of World War II; (2) have this official and public apology presented by the Prime Minister of Japan; (3) refute any claims that the sexual enslavement and trafficking of the comfort women never occurred; and (4) educate current and future generations about this crime while following the international community’s recommendations with respect to the comfort women’.

Soh, The Comfort Women, pp: 66–68; Anna Song, ‘The Task of an Activist: “Imagined Communities” and the “Comfort Women” Campaigns in Australia’, Asian Studies Review, Vol. 37, No 3 (2013), pp. 381–395.

Brittany Levine, ‘Federal Judge Upholds “Comfort Women” Statue in Glendale Park’, Los Angeles Times, 11 August 2014 (Last accessed 15 July 2016).

‘Extraordinary Council Meeting – Comfort Women Statue’, August 2015 (Last accessed 1 December 2015); ‘Strathfield Council knocks back plan to build a Comfort Women statue proposed by Korean Community’, Daily Telegraph (14 August 2015) (Last accessed 8 November 2015); Lisa Visentin, ‘WWII Peace Statue in Canterbury-Bankstown Divides Community Groups’, Sydney Morning Herald (1 August 2016) (Last accessed 16 September 2016).

Antoinette Latouf, ‘Comfort Women Statue Unveiled in Sydney Despite Ongoing Tensions’, ABC News (6 August 2016) (Last accessed 12 August 2017); Ben Hills, ‘A Fight to Remember’, SBS, 31 March 2017, (Last accessed 30 September 2017).

‘German City Drops Plan to Install First “Comfort Women” Statue in Europe’, Japan Times (22 September 2016) (Last accessed 7 January 2017).

‘First “Comfort Women” Statue in Europe is Unveiled in Germany’ South China Morning Post (9 March 2017) (Last accessed 30 November 2017).

Soh, The Comfort Women, pp. 197–201. Svetlana Shkolnikova, ‘Fort Lee to Revisit “Comfort Women” Memorial’, North Jersey.com, 21 August 2017 (Last accessed 30 September 2017). For a survey of plaques, statues, and memorials, see here (Last accessed 15 July 2016). ‘Korean-Chinese coalition plans SF comfort women memorial’, The Korea Times (6 November 2015) (Last accessed 8 November 2015). ‘Strathfield Council knocks back plan to build a Comfort Women statue proposed by Korean Community’, Daily Telegraph. 14 August 2015 (last accessed 8 November 2015).

‘Seoul Buses to Carry Sex Slave Statues in Memory of Victims’, Korea Herald (10 August 2017) (Last accessed 13 August 2017).

‘First International Memorial Day for “Comfort Women”’, Seoul Village,14 August 2013 (Last accessed 1 October 2017); ‘International Memorial Day for the “Comfort Women”’, World Council of Churches, 14 August 2014 (Last accessed 1 October 2017); ‘Expressions of Solidarity on International Memorial Day for “Comfort Women”’, National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 14 August 2016 (Last accessed 1 October 2017); Lee He-Jun, ‘More and More Comfort Women Statues Springing up, in and out of South Korea’, Hankyoreh, 24 August 2016 (Last accessed 1 October 2017); Roshni Kapur, ‘Women Rights Group Demands Japan for an Apology on International “Comfort Women” Day’, The Independent [Singapore], 25 August 2016 (Last accessed 1 October 2017); ‘Int’l Memorial Day for “Comfort Women” Marked in San Francisco’, China Daily, 15 August 2017 (Last accessed 1 October 2017; ‘From 32 to 22: “Comfort Women” Remembered in China and the World’, People’s Daily Online, 14 August 2017 (Last accessed 1 October 2017).

A replica of this version of the statue has now been erected at Shanghai Normal University. ‘Comfort Women Statues Unveiled at Shanghai University’, Japan Times (22 October 2016) (Last accessed 10 January 2017). In July 2017 fibreglass replicas of the statues of Korean and Chinese girls were placed in front of the Japanese Embassy in Hong Kong, as demonstrators marked eighty years since the commencement of the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. ‘Old War Wounds Opened up by Hong Kong Statues of Comfort Women’, South China Morning Post (Last accessed 30 September 2017); Ilaria Maria Sala, ‘Why is the Plight of “Comfort Women” Still so Controversial?’, New York Times, 14 August 2017, (Last accessed 30 September 2017. A further development is the statue recently unveiled in San Francisco. It consists of a likeness of the late Kim Hak Sun, whose testimony in 1991 was so important to the movement for redress. Her figure overlooks three young women, in Korean, Chinese, and Philippine dress, thus bringing together many of the themes of previous memorials. Conway Jones, ‘SF’s “Comfort Women” Statue Honors Victims of Japanese Sex Trafficking’, Oakland Post, 29 September 2017 (Last accessed 1 October 2017).

WSJ Staff. ‘Full Text: Japan–South Korea Statement on “Comfort Women”’, Wall Street Journal (28 December 2015) (Last accessed 31 January 2016).

Park Geun-hye attended the commemorative parade for the seventieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Beijing on 3 September 2015. In earlier times it might have been expected that it would have been the North Korean leader who attended. The attempt to settle the historical issue of wartime militarized sexual abuse was an attempt to forge closer links between the US, Japan and South Korea.

‘Abe urges South Korea to Remove ‘Comfort Women’ Statue at Busan, 2015 agreement at stake’, Japan Times (8 January 2017) (Last accessed 10 January 2017); ‘Japan Recalls Ambassador over “Comfort Women” Statue’, Japan Times (9 January 2017) (Last accessed 10 January 2017).

James Griffiths, ‘South Korea’s New President Questions Japan “Comfort Women” Deal’, CNN, 5 June 2017 (Last accessed 1 October 2017); ‘S. Korea to Create Memorial Day for Wartime Sex Crime Victims’, Yonhap News Agency, 19 July 2017 (Date last accessed 1 October 2017); ‘South Korea’s Moon Speaks out on Wartime Forced Laborers’ Right to Seek Redress from Japanese Firms’, Japan Times, 17 August 2017 (Last accessed 1 October 2017).

‘Memorial for “Comfort Women” opens in Nanjing’. Xinhuanet. 2 December 2015 (Date last accessed 15 July 2016).

A widely reproduced photograph from the end of the Asia-Pacific war shows four survivors of the system, one visibly pregnant. It is held by the US National Archives and Records Administration.

Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War (New York: Basic Books, 1997). On critiques of Chang’s work, see Erik Ropers, ‘Debating History and Memory: Examining the Controversy surrounding Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking’, Humanity, Vol. 8, No 1 (2017), pp. 77–99.

‘Commemoration of 70th Anniversary of Victory of Chinese People’s Resistance against Japanese Agression and World Anti-Fascist War’, Xinhuanet (Last accessed 15 July 2016).

Muta Kazue, ‘Taipei Fujo Enjo Kikin Hōmon Repōto: Taiwan Ianfu to Josei no Kinken Hakubutsukan Ōpun o mae ni’ [Report on Visit to Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation: Before the Opening of the Museum], Women’s Action Network (Last accessed 6 December 2015).

A documentary, The Song of the Reed, directed by Wu Hsiu-ching and produced by the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, was released in August 2015 in commemoration of the seventieth anniversary of the end of the Asia-Pacific War. ‘Documentary on Comfort Women Reaches Theaters’, Taipei Times, 13 August 2015 (Last accessed 1 October 2015).

Cynthia Enloe, ‘It Takes Two’, in Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the US Military In Asia, eds Saundra Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus (New York: New Press, 1992), pp. 22–27; Cynthia Enloe, The Curious Feminist: Searching for Women in a New Age of Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004) pp. 196–197.