Recovering the history of in-service dissent during the war in Vietnam is of utmost importance. Recognition of that dissent is essential to our documentation of the war and anti-war movement. The inclusion of those voices in our accounts honors them and establishes their roles models for later generations.

It is also important to understand why, 50 years after the war, we must work at recovering essential elements of the story that are missing in public memory and many academic accounts. While we fill-in the gaps, we need also to talk about why the gaps were left, or even created, as memories of the war years took shape: the way suppression of dissent, its cooptation and buyout, ostracism, discrediting, pathologizing, and displacement were all enlisted to silence the voices of conscience.

Recovering the Story of GI and Veteran Dissent

Suppression of Dissent—and the News About It.

Silencing occurred most directly through the suppression of dissidence at the time and place of its origin. We know from David Cortright’s 1975 book Soldiers in Revolt and David Zeiger’s 2006 film Sir! No Sir! that in-service resistance was rife from the war’s earliest years.1 That resistance was expressed through claims to conscientious objection, refusals to deploy, collaboration with civilian peace activists at off-base coffee houses, and efforts to organize opposition through the GI Press, a network of antiwar newspapers. In Vietnam, war resisters displayed anti-war symbols on clothing, sabotaged equipment, went AWOL and deserted, refused to carryout orders, and carried out acts of violence against superiors known as fragging.2

|

David Zeiger’s 2006 film Sir! No Sir! |

Anti-war sentiment arose, as well, within the walls of Hao Lo prison in Hanoi, North Viet Nam (aka the “Hanoi Hilton”) where captured U.S. military personnel were held. According on one source, 30 to 50 percent of the prisoners were “disillusioned” or “cynical” about the war by 1971, a striking figure given that most of the POWs were seasoned Navy and Force pilots noted for their patriotism and loyalty to U.S. military mission in Southeast Asia. Many expressed dissenting views through broadcasts make over Radio Hanoi and interviews given Western journalists and peace activists. And yet, that dissent is all but missing from American memory of the war years, and even from the historical accounts of opposition to the war.3

Authorities within and outside the military sought to prevent, disrupt and punish acts of dissent. Coffee houses were declared off-limits and raided by local police, radical newspapers were confiscated, peace symbols were banned and their wearing punished as Article 15 violations, and courts-marshal charges brought against the most serious offenders. Predictably, though, attempts to suppress bred more disruption and by the last years of the war the low level of troop discipline threatened military operations.

News about resistance in the war zone was slow to come out. The military long denied that it had a problem. The investigative reports it commissioned in 1970 and 1971 were not made available until after the war. Journalists were dispatched to Vietnam to find and report war stories, not anti-war stories; until veterans themselves returned with eyewitness accounts of breakdowns in unit discipline that might be affecting operations, news organizations either remained oblivious to the emerging rebellion or suppressed it.4

But the news did come out. Washington’s promise that there was “light at the end of the tunnel” for the U.S. military mission in Vietnam was dashed when communist forces mounted the Tet Offensive in early 1968, inflicting heavy losses on U.S. troops, alerting the press to prospects of a long-term stalemate, and pushing public support for the war to new lows. Newly deployed troops arrived in Vietnam with critical mindsets honed by news about antiwar protests and attitudes toward authority influence by the counterculture. By spring of 1969, many veterans of the war were ready to lend their voices to the cause of ending it.

In early May 1969 the news service UPI carried a lengthy report on the GI Movement that included photographs of coffee-house scenes and stories from underground GI newspapers. On May 23, Life Magazine featured a story about what it called “a widespread new phenomenon in the ranks of the military: public dissent (emphasis in the original). In August, the New York Daily News reported the refusal of an infantry unit in Vietnam to continue fighting. On November 9, the New York Times ran a full-page advertisement that was signed by 1,365 GIs opposing the war and included the rank and station of each signer.5

That the American people became aware of this as it happened, underscores the questions: What happened between then and now? What happened to the awareness and memory of such widespread resistance to the war within the military?

The answers lie in what happened in the closing years of the war as establishment leaders began to worry about the legacy left by a generation of warriors who turned against their war. In short, the Nixon administration, news organizations, and leading cultural institutions—Hollywood filmmakers in particular—began to redraw the image of uniformed dissenters, casting shade on their legitimacy and authenticity.

Cooptation and Buy-out.

The Vietnamese Tet Offensive of January and February 1968 revealed that the then-current U.S. strategy was not leading to victory. The U.S commitment to the war had begun with small numbers of troops sent as advisors to the South Vietnamese military; the number took a quantum leap to 184,000 in 1965 when combat units were dispatched to defend U.S. airbases. By Tet of 1968, there were 485,000, insufficient to the task thought William Westmoreland, Commander of U.S. forces. Westmoreland requested a troop increase that raised the number to 554,000, the highest it would reach.

Westmoreland’s demand for more troops could only be satisfied by drafting larger numbers of recruits, including some who had earlier been deferred for college studies or occupations in math and science deemed valuable to national defense.

Older and better educated, with more exposure to the anti-war and counterculture movements sweeping the country than was typical of earlier draftees, the “Westmoreland Cohort” arrived in Vietnam late in 1968 with debilitating consequences for military readiness. Most draftees went into the Army where applications for conscientious objection tripled between 1967 and 1969, desertion rates doubled from 21.4 to 42.4 per thousand, and AWOL rates increased by 30% from 78.0 to 112.3 per thousand. The problems for the Army were amplified by the communication skills that the cohort brought with it and the social and political contacts back home to which it could report its experiences—their skill with typewriters and mimeograph machines made them a greater threat to command control than a few hours on the rifle range made them to the enemy Vietnamese.

The impact of disaffected troops was amped still higher when they returned from Vietnam. As portrayed in Sir! No Sir!, anti-war veterans sought out men destined for Vietnam to educate them on what the war was about. The countermove by the Brass was to keep these populations apart: isolate the veteran-voices of conscience from willing listeners. By 1969, draftees had a 24-month commitment to service; the Army tour in Vietnam was 12 months. With time for training and leave time before going abroad, many were returning from Vietnam with six to seven months left on their 12 months in the service—six to seven months with little else to do but mix with and influence those awaiting departure for the combat zone. By discharging draftees returning with less than six months remaining on their 24-month hitch, their isolation from those preparing to leave for Viet Nam was assured. And by allowing them to extend in Vietnam just the number of days required to put them over the six-month bar, many were home from Vietnam and out of the Army 19 months from the date of their induction.6

The closing years of the war also raised suspicions that awards for service medals were being handed out generously in order to placate disgruntled troops. Officers in particular seemed be departing Vietnam with questionable decorations. Navy SEAL Bob Kerrey, later a Nebraska Governor and Senator and President of The New School in New York City was awarded the Medal of Honor for leadership in a February 1969 operation. In a later interview, he recalled having considered declining the award, feeling at the time that its purpose was to lure him away from participation in the antiwar movement.7

Ostracizing the Veteran Voice.

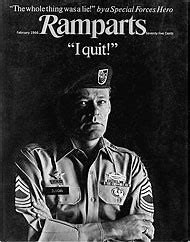

Going forward, it was the voices of anti-war veterans testifying to what they had done and seen would play an important role in shaping public memory of the war. Donald Duncan a Green Beret Sergeant decorated for gallantry, left the Army and came out against the war with an article “I Quit” in the February 1966 edition of Ramparts magazine; in it, he declared the war to be a “lie.” The April 15, 1967 mobilization against the war (known as “Spring Mobe”) brought together six veterans to form Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). The presence of anti-war veterans at the October 1967 March on the Pentagon and in the 1968 campaign of anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy established them as a powerful voice for peace in Vietnam.8

|

Donald Duncan, Ramparts Magazine, February 1966. |

No longer subject to the censorship of military authority, and with access to the civilian press, dissident veterans posed a challenge to the pro-war establishment. Unable to directly suppress and punish dissenting views, the Nixon White House sought, instead, to drive a wedge between the radical veterans and the liberal majority in the antiwar movement.9

Early efforts to do that took the form of ostracism, defaming protesting veterans as traitors and even communists. When VVAW members marched from Morristown, NJ to Valley Forge, PA to protest the war in September 1970, older veterans of previous wars belittled them for their long hair and shouted for them to “go back to [the enemy capital] Hanoi”. 10

In April 1971 VVAW staged an encampment on the capital mall in Washington to accompany its lobbying effort to end the war. John Kerry, representing VVAW, gave a passionate antiwar speech before a congressional committee for which he was later accused of betraying the security of the troops still in Vietnam. A year later, efforts to criminalize VVAW peaked when charges were brought against the Gainesville FL chapter for planning an armed attack on the 1972 Republican Party national convention in Miami Beach.11

Discredit Their Authenticity.

The widespread distrust of information flowing from Washington about the war meant that the voices from the ground level view of returned veterans were especially welcomed by the American public—and especially threatening to political and military elites. If those voices could not be suppressed or isolated, they would have to be discredited, their identity disputed, their authenticity impugned. Beyond the crude suggestion that VVAW members might be agents of a hostile government and criminalized as seditious, critics suggested that protesting veterans were not “authentic,” their numbers inflated by radicals posing as veterans. Speaking before a military audience in May of 1971, Vice President Spiro Agnew said he didn’t know how to describe the VVAW members encamped on the mall but “heard one of them say to the other: `If you’re captured . . . give only your name, age, and the phone number of your hairdresser.”12

|

Marching Against the War: Vietnam Veterans Against the War |

In the same speech, Agnew said the antiwar vets “didn’t resemble” the veterans “you and I have known,” a statement, when combined with having gay-baited them, was a effort to draw an “us and them” distinction, a discourse that anthropologists would characterize as “otherizng.” Thusly drawn, the line invited more pronounced differentiations between “real men” and those who now refused to fight.

Stigmatize as Pathology.

Ostracizing and otherizing are forms of stigmatizing, the denigration of an individual or group’s identity. In his 1964 book Stigma sociologist Erving Goffman wrote that the attribution of stigma can disqualify those “others” from full social acceptance. In modern society, assignment of mental illness to targeted parties has become a powerful and pervasive form of stigmatizing.13

The first unlawful break-ins leading to the Watergate scandal of 1973 were those done by President Richard Nixon’s “plumbers” on the psychiatrist’s office of Daniel Ellsberg. Ellsberg, a Marine Corps veteran and employee of the Rand Corporation doing contract work for the government, had copied secret documents showing that political and military leaders had been misleading the public on the conduct of the war for years; those documents were later known as “The Pentagon Papers”. Ellsberg had released the papers to the press in 1971 incurring the wrath of the President. Wanting to discredit Ellsberg prior to the 1972 elections, Nixon assembled a team of former FBI and CIA agents to burglarize the doctor’s office for files that would “destroy [Ellsberg’s] public image.”14

Simultaneous with the plumbers’ raid on the psychiatrist’s office, press reports were hanging the same mental health markers on VVAW actions. When VVAW gathered in Miami Beach to protest the Republican Party’s nomination of Richard Nixon as its presidential candidate in 1972, the New York Times featured a front-page story on the mental problems of Vietnam veterans. Beneath a headline reading “Postwar Shock Besets Ex-GIs,” the text was peppered with words and phrases like “psychiatric casualty,” “mental health disaster,” “emotional illness,” and “mental breakdown.” The story acknowledged that there was little hard research on which to base those characterizations. Indeed, if the reporter had done his homework he probably would have found Peter Bourne’s 1970 book Men, Stress, and Vietnam in which Bourne, an Army psychiatrist in Vietnam reported American personnel having suffered the lowest psychiatric casualty rate in modern warfare.15

After the 1972 Times story, the press tapped-out a steady beat of stories about soldiers home from Vietnam with psychological derangements—and journalism was in step with the direction popular culture was headed with its representations of the war and the people who fought it. Hollywood had begun portraying Vietnam veterans as damaged goods since the mid-1960s and, consequentially, writing political veterans out of their stories. Films like Blood of Ghastly Horror (1965) and Motor Psycho (1965) anticipated the symptomology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder before health care professionals coined the phrase. Controversies over the validity of war-trauma nomenclature riled professional organizations throughout the late 1970s, and when PTSD was finally confirmed as a diagnostic category by inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association in 1980, one of the authors of the terminology, Chaim Shatan, credited the New York Times’s opinion piece with having been the difference-maker in professionals’ deliberations of its merit.

|

Shoulder Patch Capturing the Paranoia about “Hidden” War-wounds. |

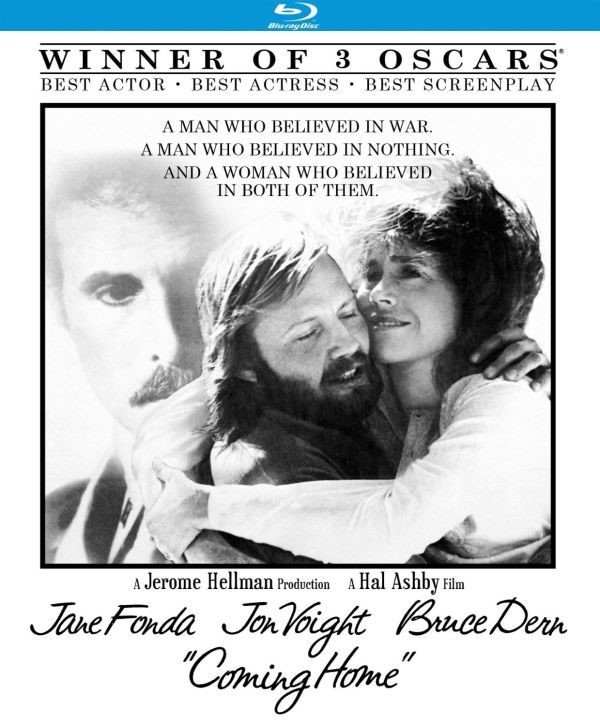

The shift from the political discourse that had dominated the veterans’ homecoming story in the late 1960s and early 1970s to the mental-health discourse that became dominant in the 1980s is evinced in Hollywood film. In the 1978 film Coming Home Luke (Jon Voigt) is politicized by his experience in Vietnam and shoddy treatment at a military hospital; he comes out publicly against the war. Four years later we’re given Rambo (Sylvester Stallone) who suffers flashbacks to his combat experience in the opening scene of First Blood, and then goes on a murderous rampage. Although political veterans like Luke were never prominent in feature films, the die was cast with Rambo—from then on, American film-goers got a regular diet of warriors home with hurts.

|

Jacket Cover for the 1978 film Coming Home. |

Displacement.

I began teaching courses on the memory and legacy of the war in Vietnam in the 1990s. Introducing the course, I would ask students if they had ever heard of Vietnam veterans with PTSD—all (or most) students would raise their hands. When I asked if they had heard of VVAW, no (or few) hands went up.

The silencing of the anti-war veteran voice was a matter of the public forgetting that many Vietnam veterans spoke out against and resisted participation in the war. But forgetting is not just a lapse in memory, not a passive failure to remember. Forgetting is not about the memory that did not happen. Rather, we forget something because something else overrides, or supplants and takes the place of what we had known from experience or first-hand evidence. Forgetting is about something else displacing what we had known.

The rebel GIs and veterans that appeared on front pages and television news coverage in the early 1970s would be “forgotten,” pushed out of memory by images of “good” veterans befitting the GI Joe figures loyal to their mission and nation born out of World War II lore.16 The existence of “good” veterans was largely conjured out of the myth that “bad” anti-war activists had been hostile to Vietnam returnees, even spitting on them; the good-bad binary of that myth suggested that the existential badness of spitters implied the goodness of their targets.17 Further, the alleged trauma of the homecoming experience for “good” veterans was the stimulus for the victim-veteran narrative that underwrote the diagnostic nomenclature of PTSD. The conflation of normative “goodness” and mental-emotional pathology thereby completed the construction of a more comfortable idiom for remembrance of Vietnam veterans than that of VVAW.18

|

A Street Person Presenting Himself as a Down-and-Out Veteran |

The Forgotten POW Dissenters

If there was a segment of the Vietnam veteran population destined for canonization as good veterans, it was surely those who had been captured and imprisoned during the war. And yet, as it turned out, the POW story is as complicated and conflicted as is that of the rest of the Vietnam generation of veterans.

The peace agreement that ended the war on January 27, 1973 stipulated the arrangements for the release of U.S. POWs, most of them held in prisons in and around Hanoi. The releases began on February 12 and continued in three increments into March. Carried aboard Air Force C-141 aircraft, they landed first at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines for debriefing and medical assessment. From Clark, they were flown to stateside basis and on to their hometowns.

News coverage of the POW’s arrival at Clark anticipated stories of dissent behind the bars that were yet to come. “Freed P.O.W. Asserts He Upheld U.S. Policy” read a February 15 New York Times headline before reporting that the pilot had made statements opposing the war while being held. A February 23 headline, “P.O.W.s maintained Discipline but had Some Quarrels and were Split on the War” promised still more.

Intriging as they seem, those headlines may have been less so for readers in 1973. Peace activists and journalists had been journeying to Hanoi for years where they met with POWs and heard a range of views about the war. George Smith, captured in the South and released in 1965, had written a book, P.O.W., about his two years in captivity that was critical of the war. Far more interesting in retrospect is how, what was widespread knowledge about POW dissenters in 1973, has been forgotten. As with the lost history of GI and veteran dissent recounted above, the story of POW dissent is less about forgetting than the reconstruction of memory. 19

“Muzzled POWs . . . “

Not a screech from an ACLU broadside, “muzzled POWs,” replete with the ellipting periods, headed a New York Times editorial—not an op-ed—on February 24, 1973. It followed a set of stories carried on its own pages about attempts to suppress news coverage of POWs’ dissent since their release twelve days earlier. News about the suppression of POW news led the news: “P.O.W. conduct barred as Topic” read a February 5 headline a week before the first releases; “Managing the P.O.W.s: Military Public Relations Men Filter Prisoner Story” on February told of 80 public relations specialists assembled to “hide possible warts and stand as a filtering screen between the press and the story.”

Even before anti-war veterans hurled their medals onto the Capitol steps in April, 1971, a group of anti-war POWs was taking form as the “Peace Committee” in the Hanoi lockups. News magazines like Time, and Newsweek had been made available to the POWs by the prison administration, so news about the unpopularity of the war at home was always within earshot of the prisoners.20 The loudspeaker PA systems in the prison facilities regularly broadcast news about the US antiwar movement that included “draft card burnings” and “defectors” which presumably referred to in-service rebels and VVAW.21

For that matter, the POWs captured after October 1967 when 50,000 protesters marched on the Pentagon, which was most them, would have known that resistance to the war was spreading through the military ranks and that hundreds of returnees from Vietnam were in the streets as veterans against the war. Most profoundly, it was widespread knowledge that fellow POWs George Smith and Claude McClure had come out against the war after their release—Smith’s book P.O.W.: Two Years with the Viet Cong was made available to the Hanoi captives by prison authorities.22

April 1, 1971 is also when twelve POWs taken in South Vietnam and known as the “Kushner Camp” arrived in Hanoi. Some, including the group’s Senior Ranking Officer (SRO), Captain Floyd Kushner, had been in captivity since 1967 and been exposed to unimaginable harshness in jungle living with inadequate nutrition, primitive sanitation and health care, confinement in tiger cages, and forced marches. Along the way, the group witnessed the execution of recalcitrant comrades and the deaths of others due to neglected wounds and untreated disease. Their survival instincts and disgust for the war honed by their experience, the Kushners were receptive to the voices of conscience rising within the Hanoi prison system and ready to join the chorus.

Whatever its genesis, dissent was growing inside the walls of Hao Lo by 1971 and, not unlike their counterparts in leadership across the U.S. military system, the Senior Ranking Officers (SROs) in the Hanoi prison system came down hard on the Peace Committee (PC) and its fellow travelers. Efforts to suppress their protests included threats of courts-martial when they were released and returned to the states.

When outright suppression didn’t work they warned others to stay away from the radicals, trying thereby to isolate the bad apples. The prison administrators and guards controlled the movement and communications among the prisoners, of course, but the SROs contrived their own Kangaroo command hierarchy into which they tried, first, to coopt the highest-ranking dissidents, Navy Capt. Walter Eugene Wilber and Marine Col. Edison Miller, and, failing that, “relieved [them] of military authority” –“excommunicated” them, as historian Craig Howes put it. From then on, wrote Howes, “most men avoided them like the devil.”23

POW mate calls McCain ‘liar’ over ‘turncoat’ charge

|

Edison Miller, POW Charged with Collaboration, Denies the Allegation. |

The demonizing of the dissidents through “excommunication” is a recognizable form of stigmatizing, the same tactic as that implemented against the GI and veterans’ movements in the States. By exiling the leaders, the SROs had set them up for victim-blaming: their isolation would be construed by their peers (and later the American public) as self-exacted, a kind of asked-for segregation, for which they were responsible. Putatively, the irrationality of their behavior stemmed from personal traits: they were loners, losers, alienated, and maladjusted, a cluster of shortcomings bespeaking weak character.24

The “weakness” notion was a kind of slander but it gained currency through its application to the Kushner group, many of whom were younger enlisted men who were less educated than the high-ranking pilots who preceded them into the Hanoi lockups; the group, moreover, was disproportionately Black.25 The ascription to personal failings of the Kushners’ anti-war leanings and resistance to the SRO’s chain-of-command was a way to discredit the political authenticity of their opposition. Notwithstanding the condescension of rooting those “weaknesses” in the rebels’ social backgrounds, the weakness language was also a form of character assassination; it was a dog whistle for moral weakness, the failure to witness to faith by willingness to suffer worldly deprivation. With a twist, it riffed on the mental health discourse already forming the narrative of GI and veteran dissent into which the voices of conscience home from Hanoi would be fitted.

The disrespect shown for the anti-war POWs followed them into their release and return home. From their first landing at Clark Airforce Base in the Philippines through the White House welcoming staged for the POWs, their representation in the press, and further on to the stack of books that would be written about the “POW experience,” they were the deviants whose behavior needed to be accounted for and explained.

From Muzzled, to Criminal, to Medical: The Transforming Narrative of POW Dissent

Forgetting is insidious because it entails its own obscurity as a process even as it takes place. In the case of the POW dissidents, the news about their censoring was short-lived, replaced first by stories about legal charges brought against them, and their defense against those charges. It was a kind of reversing-the-verdict maneuver whereby the stories about muzzled POWs that had had the government on the defensive for the violation of freedom of speech were now reversed, putting the dissidents on the defensive for their conduct as prisoners.

Most news stories in March carried headlines like Seymour Hersh’s for The New York Times on March 16, 1973, “Eight may face Courts-Martial for Anti-war roles as P.O.W.s.” It was not as though the P.O.W.s were silenced by that spin so much as that they were being compelled by the discourse itself to speak as defendants in interviews with news reporters that were framed by legalese rather than their own voices of conscience. The conflict between those modes of discourse was on display in Mike Wallace’s interview with Eugene Wilber for the April 2, Sixty Minutes on CBS. Confronted with Wallace’s insinuation that he must have caved to the fear of torture—the “weakness” narrative that was building in the press—Wilber stuck with his claim to “conscience and morality.” Wilber’s stand effectively turned the tables, putting the prosecutorial parties on the defense for suppressing conscience.26 Wilber’s adherence to principle, however, was a grain of sand in the celebratory tide raising the stature of the “good” POWs reputed to have pridefully endured the torture handed out by their communist captors.

The POW news in May was dominated by President Richard Nixon’s White House reception for them and their families. Press coverage of the reception totally erased the anti-war POWs from the story, and worse, did not cover the intimidation and threats inflicted on them and their families behind the scenes.27

When they returned to the news, the dominant narrative had turned again—the rebels weren’t criminal so much as emotionally and psychologically hurt, sick, damaged goods just as were their brothers who had been in the streets as protesters against the war since 1967. A June 2 Times story headlined “Ex-P.O.W.s to get Health Counseling for 5-year Period” sprinkled in references to “high violent death rates,” “depression,” “fright,” and “euphoria” (sic), with no references to sources for the claims. “Some Wounds are Inside: Health of P.O.W.s”, headlined a June 10 health column, raising mental health as the specter that would stigmatize dissent as a symptom. A July 15 Times story “Antiwar P.O.W.s: A Different Mold Seared by the Combat Experience” locked-in the mental health discourse despite there being virtually nothing in the content of the story to support the use of “seared” in the headline.28

The psychologizing of the dissenting views within the POW population was a way to dismiss their authenticity as political and moral expressions of conscience.

Eugene Wilber, Edison Miller, and the Peace Committee were integral to the first history of the POW affair written by John Hubble in 1976. But Hubble used the dissidents as negative referents against which to define the “good” POWs, the ones who not only fought with courage before capture but continued the mission as “prisoners at war” in counter distinction to “prisoners of war”. The “prisoner at war” is the protagonist, à la John Smith in the American captivity narrative, the centerpiece of the Nation’s founding mythology; the “war” in that story being as much about the struggle within the individual and collective Self as it was between captives and captors. The strength to resist the attraction of the Other—as the temptation of Pocahontas is portrayed in the John Smith legend—and refuse favorable treatment, entailed the repression of desire, the deferment of worldly comfort out of a commitment to principle and religious faith. The memoirs of the Vietnam War POWs record the Christian intonations of their resistance to the temptations proffered by the guards, and even an embrace of torture to validate their virtue—the strength of their virtue confirmed by the bad POWs who succumbed to temptation.29

The rebel POWs had no place in the Smithian narrative. And with the loss of the war having marginalized the otherwise honorable tradition of American dissent—the Thomas Paines, Jane Adams, and Martin Luther Kings—there were no associations with which to associate the POW dissidents. What, exactly, was to be remembered? The GI and veterans’ movements had begun at a time when the anti-war movement was peaking in the late 1960s; they were embraced as allies in the general and larger movement and written into its historical accounts. By contrast, the story of anti-war POWs unfolded after the war was over and the anti-war movement was dissolving.

Antiwar Warriors: A Place in the American Story?

Service members, POWs, and veterans who spoke against the war remain contested figures in Vietnam war remembrances. Easily scapegoated for the loss of the war—their words were said to have demoralized their comrades still in the fight and lent aid and comfort to the enemy, according to their detractors. The efforts to discredit their dissent as psychological disorder nevertheless had a sympathetic tonality that bent some critics toward understanding if not forgiveness. Viewed as tragic figures caught in the fog of war, on the other hand, their courageous stances blended into an ill-focused victim-veteran figure destined to fade from social memory.

Their displacement from memory was abetted by broader anxieties left by the war. Public upset that war had been mismanaged by Washington and hampered by people-of-conscience naively misled by leftwing propaganda was a recipe for McCarthyite conspiracism. Stirred by Hollywood film and the revanchist Reagan-Bush presidencies in the 1980s, the conspiracy theorists fantasied a sellout of the military mission by an intelligentsia highly placed in media and governmental circles, aka the “Washington insiders.”30

The storyline of an enemy inside the gates rendered the history of in-service dissent a mere footnote in a larger narrative of national degeneration as cause for the defeat in Vietnam. It wasn’t just that returning veterans were said to have been spat on by protestors—they were neglected and forgotten by an ungrateful American public as well, and POWs, the good ones, were “left behind,” abandoned in Southeast Asia by a government hastening to forget the ignominy of a lost and unpopular war.

The memory of the Vietnam veterans who lent the credibility of their uniforms to the cause of peace has largely been displaced by that of veterans victimized by the war as successive administrations have waged new wars from Iraq and Afghanistan to Libya and Syria. That displacement has diminished their appeal as role models for a new generation of would-be resisters and deterred the out-reach of civilian peace activists for allies within the military.

When the Iraq Veterans Against the War base-tour bus stopped at the Navy base in New London, CT in 2006, I asked Tom Barton, one of the organizers about the response they were receiving from the local groups hosting them. “Everywhere we go,” he complained, “all people want to talk about is PTSD. Do these guys look fucked-up to you?” he asked, waving his arm toward the IVAW members. No, I answered, before beginning a conversation about the way anti-war Vietnam veterans’ voices had been silenced and the legacy of their missing voices in our political culture.31

A full accounting of the whys and wherefores of the war in Vietnam, and the legacy of GI resistance for the country today, is an ongoing project. The story of the silencing of dissenting voices of service members and POWs is one of the biggest gaps in the historical record, one that is only beginning to be filled.

Notes

The 13-episode The War in Vietnam produced for public television in 2017 by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick touch on themes of in-service dissent but in ambiguous ways. I reviewed the film for Public Books here.

The history of the coffee houses is written by David L. Parsons in Dangerous Grounds: Antiwar Coffeehouses and Military Dissent (UNC Press, 2017). For GI Press history, see James Lewes’s Protest and Survive: Underground GI Newspapers During the Vietnam War (Praeger Press, 2007).

The military constraints on civilian reporters were tighter than sometimes believed today. It was not easy for reporters to get out of major cities and military installations. When they did, they were sometimes “given a story” by a field unit’s “public affairs liaison” and put on a plane back to Saigon. See Cortright (p. 269) for references to the Army’s inquiries into dissent.

The major news breakthroughs came in 1969 due, in part, to growing public pessimism about the war after the Tet Offensive of 1968 and the presence in the military of an older and better-educated cohort of draftees that came in with the post-Tet callup. See my “Contradictions of 1969: Drafted for War, The Westmoreland Cohort Opted for Peace” in The American Historian, May 2018.

A month after the action for which he was decorated, Kerrey led a raid on Thanh Phong village in which his men knifed to death its inhabitants. Later critics called the deaths murder, charges that dogged Kerrey in the latter years of his career. See here.

Just after the October 15, 1969 Moratorium Day against the war, H.R. Haldeman, an aide to President Richard Nixon, said, “The trick here is to try to find a way to drive the black sheep from the white sheep within the group that participated in the Moratorium . . .”

The University of Northern Colorado chapter of VVAW, of which I was a member, was banned from a Veterans Day parade in the early 1970s. Working around the ban, we followed behind the parade stepping to a solemn “death march” cadence.

For an analysis of Kerry’s speech and responses to it, see David Thorne and George Butler, The New Soldier: Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

John R. Coyne The Impudent Snobs: Agnew vs. The Intellectual Establishment (Arlington House Press, 1972).

Erving Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Identity (Penguin, 1964); Liz Szabo, “Cost of Not Caring: Stigma Set in Stone—Mentally Ill Suffer in Sick Health System.” USA Today, 2014.

The Times article was Jon Nordheimer’s, “”Postwar Shock Besets Ex-GIs” August 21, 1971. See Peter G. Bourne, Men, Stress, and Vietnam (Little, Brown 1971).

As “lore,” the origins of ideal American veteran are obscure and largely figments of imagination. The GI Joe figurine was created in the early 1960s, too late for it to have been more than a cultural expression during the 1960s and 1970s. More likely, Americans expected their soldiers to look and act like John Wayne playing Marine Sergeant John Stryker in The Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) or Audie Murphy (said to be the most decorated veterans of WWII, playing himself in To Hell and Back (1955).

A 1971 survey by the Harris Poll conducted for the U.S. Senate reported 99% of Vietnam veterans polled saying they were welcomed home by friends and family, and 94% of the veterans polled saying their reception from their age-group peers was friendly. Only 1% of veterans in that poll described their homecoming as “not at all friendly.”

The binary nature of the spat-upon veteran is developed more fully in my The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam, Pp. 5, 53-55, 104, 124.

The blackout of news about shot down U.S. pilots may never have been as great as some Americans believe today. In John Hubble’s book P.O.W.: A Definitive History of The American Prisoner-of-War Experience in Vietnam, 1964-1973, which is regarded as the “official story,” he records (pp. 51-52) pilot Larry Guarino’s arrival in Hao Lo Prison in June of 1965 and his telling Bob Peel, who had been captured earlier, that he had “read about” his capture and that “your name has been officially released as definitely captured.”

In “Antiwar P.O.W.s: A Different Mold Seared by Their Combat Experience” The New York Times Steven V. Roberts on July 15, 1973 reported, “All members of the peace committee—the men say that they never organized a formal group or gave themselves a name. . . .”

The quoted words are Nick Rowe’s in Stuart Rochester and Frederick Kiley’s Honor Bound: American Prisoners of War in Southeast Asia, 1961-1973. Rochester and Riley write (p. 193) that POWs got news of Quaker Norman Morrison’s self-immolation in November 1965, the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal, and (p. 412) the 1968 Democratic National convention.

When jungle prisoners Smith and McClure were released in late November/early December 1965, the American news media and superiors in Washington characterized them as either “turncoats” or victims of “brainwashing,” according to Rochester and Kiley (p. 249). The notion of brainwashing was popularized in the accounts of Korean War POWs who choose to stay in North Korea after the war. Brainwashing, however, never gained the same credibility in the case of Vietnam POWs.

Craig Howes’s Voices of the Vietnam POWs (pp. 110-111) is a reliable source for the struggle between SROs and PCs. The quoted “excommunicated” is his. The SRO’s attempt to control their own imprisoned peers was based on their reading of the military Code of Conduct. Post-war legal proceedings judged the Code to be a nonbinding guide to the behavior of captives, not an inviolable set of orders which the PCs were legally obligated to follow. The SROs also played the “buyout” card, offering Wilber and Miller the chance for “reinstatement” as commanding officers in the chain of command they had configured. See Rochester and Kiley, p. 553.

The “weakness” theory had its predecessor in official accounts of Korean War POWs: some had turned against the war and even elected to stay in North Korea when released. See Albert D. Biderman’s 1963 book March to Calumny: The Story of American POWs in the Korean War (Pp. 166-167) for the weakness thesis.

Hubble (p. 109) attributes the Kushners’ motivations to “naivete, weakness, and mental illness.” Rochester and Kiley (p. 565) add “lacked strength and intelligence and discipline” to the list.

The New York Times, May 23 “Ex-P.O.W.s Cheer Nixon” made no mention of the dissidents, nor did its June 2 story “400 Ex-P.O.W.s are Given $400,000 Dallas Reception.” Tom Wilber, Eugene’s son, is a source of information on the behind the scenes shenanigans against the family.

Like for other antiwar veterans, the diagnostic framing of their views functioned politically and culturally more than medically. Press reports at the time portrayed POWs as healthy and later medical reports confirmed that. POW memoirs written as late as the mid-1980s make no mention of PTSD or trauma.

Pauline Turner Strong, Captive Selves, Captivating Others: The Politics and Poetics of Colonial Captivity Narratives.