Translation into Ukrainian by Kate Belevets of OhMyEssay.com.

Resume

This is a slightly expanded version of the talk delivered by the author upon the occasion of the launch of his The State of the Japanese State at Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan (FCCJ), Tokyo, on 17 October 2018.1 It traces the evolution of Japan, especially under Abe Shinzo, as a “client state” (defined by Wikipedia as “a state that is economically, politically, or militarily subordinate to another, more powerful state”) of the United States. It considers what I now refer to as Mark One and Mark Two versions of that “client state” in the post-Cold War era, and discusses the persistent challenge to the clientelist frame arising from the Okinawan refusal to submit to it. It raises finally the possibility of either a Mark Three or of Japan’s future sloughing off client state status altogether. Taking off from the book, it goes beyond it.

|

The Dependent State

It is more than 10 years since I began using the term “client state” (zokkoku) to refer to post-war and contemporary Japan, particularly the early 21st century Japanese state of Abe Shinzo,2 adopting the generic term “clientelism” to refer to the patron-client character of the US-Japan relationship. I borrowed the term not from any radical critic but from the arch-conservative and former Deputy Prime Minister Gotoda Masaharu, who used it with the implication of absent or lost sovereignty. I use it to mean a state that spontaneously chooses servitude, insisting on the “alliance” with the US as its charter (with de facto priority over the constitution), on the absolute privilege of the US military presence in Japan, especially in Okinawa, and on either constitutional revision or revision of its interpretation (so as to allow “collective security” and “normal” military power (i.e. war).

I returned to the question of the Client State, considering especially its comparative dimension, in 2013,3 in discussions with John Dower in 2014,4 and most recently, in my June 2018 The State of the Japanese State. Others employ a similar framework. In 2016, Shirai Satoshi and Uchida Tatsuru entitled their book “Zokkoku minshushugi” (Client State Democracy),5 and in 2018 Shirai published an important study entitled “Kokutairon – Kiku to seijoki” (National Polity Theory – The Chrysanthemum and The Stars and Stripes) comparing the emperor-centred polity of pre-1945 Japan with the servile-to-America post-1945 70-odd years, suggesting that both polities over time became exhausted, plunging Japan into existential crisis. 6 It became a non-fiction best-seller.

The servile or zokkoku line was rooted in the defeat in war and seven-year long occupation of Japan by the United States. The foundations of the state – the constitution of 1946 and the San Francisco Treaty of 1951 – laid then, have remained more or less unaltered. Though a measure of sovereignty was returned to Japan in 1952, through the four post-1952 decades of the Cold War the client state relationship persisted, sank deep roots, and was relatively stable. The focus of the present essay is the quarter-century post-Cold War era, during which the relationship has occasionally been contested but the client (Japan) has insisted that the patron (the United States) continue its patron role, occupying bases and determining key policies.

As the foundations of long-term dependence were laid, the Japanese emperor, Hirohito, till war’s end Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army and high-ranking war crime suspect, became a favoured instrument of US purpose and architect of the post-war state. It was at his suggestion that Okinawa was severed from Japan under the San Francisco Treaty settlement, that the country’s security was made to depend on “initiatives taken by the United States, representing the Anglo-Saxons,”7 and (with his enthusiastic support) that Japan gave a positive answer to John Foster Dulles’ question: “Do we get the right to station as many troops in Japan as we want where we want and for as long as we want? That is the principle question.”8 Japan is unique in today’s world in that its state structure was essentially designed and built to the interests of a foreign occupying power.

From Hirohito in the 1940s to today’s Abe, the clientelist path of submission to the global super-power made sense on the understanding that US global dominance and benevolence would continue. Today both assumptions seem at best shaky. The geo-political and economic underpinnings of the clientelist assumption have been rudely shaken. The US, now 16% of global GDP, is expected to decline to 12% by 2050 while China already 18%, is expected to rise to 27% during the 2030s.9 As for the Japan-China relationship, China’s GDP, one-quarter of that of Japan as of 1991, surpassed it in 2001,10 and, if the CIA World Factbook 2017 is to be believed, it is already more than 4-times that of Japan ($21.27 trillion to $4.92 trillion). That shift in relative weight disturbs and challenges. The worry begins to spread that the two centuries of “Anglo-Saxon” hegemony, launched by the gunboats of the 19th century and maintained by overwhelming military might into the 21st, might be coming to an end.

The awareness has been slowly growing over the quarter-century since the end of the Cold War, among politicians, both “conservative” and “progressive,” and much of Japanese civil society, that it is inappropriate for Japan, now a great economic power, to remain locked in servility to its erstwhile conqueror and occupier, that it is time to move from subservience to autonomy. But how would such a posture be articulated? Would the US tolerate it? Broadly speaking, the most influential responses have been on the right from Abe Shinzo and his colleagues in organs such as Nihon Kaigi, and on the left from relatively liberal figures such as Hosokawa Morihiro (Prime Minister, 1993-4) and, a decade later, Hatoyama Yukio of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ).

Clientelism, Mark One, 1993-2010

Abe Shinzo, first seated in the Diet in 1993, called for an end to the “post-war regime” and for fundamental revision of the US-imposed post-war system. He wanted to substitute for the post-war state’s liberal democratic model a blend of neo-nationalism, historical revisionism, and neo-Shinto, rooted in the kokutai or national polity of pre-war and wartime Japan and with the Yasukuni cult a core element in the national psyche. The Abe of that Mark One era became actively involved in:

The Liberal View of History movement, launched 1995,

The Committee to Produce New History Texts (Tsukurukai) in 1997,

The Dietmembers Association “for the passing on of correct history” in 1995,

Nihon Kaigi [Japan Conference] (established 1997),

The Shinto Politics League (founded 1969 but prominent from the late 1990s).

He imagined Japan, beneath the emperor, as a unique, superior, “beautiful country” as he put it in his 2006 book,11 or, as then Prime Minister Mori put it in 2000, “a land of the gods centred on the emperor.”

During Abe’s first term, 2006-7, he appears to have believed it possible to “cast off” post-war strictures and become a “normal” state (with a fresh constitution and unshackled armed forces) while yet somehow continuing Japan’s “client state” relationship to the United States. But how was he simultaneously to affirm and negate nationalism, to be at once assertive and yet dependent? What did Abe mean when he spoke of “taking Japan back” (Nihon o torimodosu)? From whom would he take it “back”? Where would he take it to? What did it signify that he denied or equivocated about war responsibility, Comfort Women and Nanjing, and insisted on rewriting Japanese history to make people proud? Whether or not he was conscious of the contradiction, Abe’s Mark One agenda was at odds with that of Washington’s “Japan handlers” (as they came to be known). During that first term, he kept away from Yasukuni and made only tentative steps towards constitutional revision, but his antipathy for the US-imposed institutions and his fundamentalist ideology nevertheless worried Washington. Mission incomplete, he resigned in September 2007.

If Abe’s early post-Cold War project to equivocate the Client State was plainly a reordering from the right, there were also significant challenges to it from the left. Both the liberal Hosokawa Morihiro government of 1993-94, and the Democratic Party of Japan’s government of 2009-10 envisaged a Japan-US relationship based on equality and a shift in the country’s axis from US-centred uni-polarism towards multi-polarism. The “autonomists” (as some would call them) attempted to formulate an independent foreign policy tied to the United Nations and to disarmament, equidistant from China and the US, reducing or eliminating US military bases, interpreting the constitution’s Article 9 strictly and favouring positive engagement in the construction of an Asian or East Asian community. But the contest was hopelessly unequal.

The Hosokawa government was relatively short-lived and never seriously pursued a “beyond clientelism” agenda although it did produce one major paper offering tantalizing outlines for such a policy. 12 A second “autonomous” line project evolved between 2005 and 2012 under the Democratic Party of Japan, reaching a climax with the government of Hatoyama Yukio in 2009-2010. In its 2005 Manifesto the DPJ declared a commitment to “…do away with the dependent relationship in which Japan ultimately has no alternative but to act in accordance with US wishes, replacing it with a mature alliance based on independence and equality.” Even before it took office, its most effective leader, Ozawa Ichiro, famously suggested that US bases, notably those in Okinawa, were no longer necessary and that the 7th Fleet should suffice for US needs.

Washington’s response to the Hosokawa and the Hatoyama challenges was unequivocally negative. Instead it spelled out the principles appropriate to a Japanese client state in a 1995 report, commonly known after its primary author (Joseph Nye) as the “Nye Report.” Any diminution of US military hegemony was unthinkable since East Asian security depended on the “oxygen” of US military presence and therefore on preservation of the bases and retaining 100,000 soldiers based in Japan and Korea. It meant denying full sovereignty to both East Asian countries. The US would continue to exercise the right to dictate policy.13

Nye, together with Richard Armitage and the East Asian scholar-bureaucrats who made up the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), followed that 1995 report by others in 2000, 2007, 2012, and again in 2018, on the US-Japan relationship and the stance required of Japan.14 These policy papers spelled out the legal and institutional reforms to reinforce the Alliance and consolidate Japan’s servility.

The Nye/CSIS frame of thinking was/is predicated on distrust of Japan and belief in the need for US military occupation to continue indefinitely. It reflects not just bitter memories of the war experience but also the paternalism of General MacArthur to whom the Japanese (in 1951) were a juvenile and immature people aged just twelve years old compared to the 45-years old Anglo-Saxons and Germans,15 and the view of Henry Kissinger (a senior adviser and counsellor to CSIS) – as he put it in conversation with Zhou Enlai in 1971 – of the Japanese people as erratic and dangerous, needing to be restrained. It was the military dominance of the United States, according to Kissinger, that “keeps Japan from pursuing aggressive policies.”16 The Marine Corps’ Major General Henry Stackpole referred to the same concept in 1990, as the “cap in the bottle,” as if the US forces were occupying bases in Japan in order to protect Asia from Japan.17

For threatening to dissolve the mechanism of clientelism, the DPJ government of Hatoyama Yukio (September 2009 to May 2010) was subject to a relentless barrage of warnings, threats and insults, of a kind that only a superior state could possibly issue to its subordinate or client. No other major ally had ever been subjected to anything like it. Lying, deception, secret deals, cover-up and manipulation characterized the alliance.18

The attempt to formulate a post-Clientelist, “autonomous” line national direction failed both in 1993-5 and in 2009-10.

Clientelism, Mark Two, 2012-2017

During those years between his first and second government (2007-2012) Abe appears to have concluded that he would have to strip off his “nationalist” garb and concentrate on performing the tasks expected of a subordinate state, steering the country into a new and deeper phase of Clientelism, Clientelism Mark Two it might be called.

Just months before his return to office, CSIS issued its third Report, cautioning Japan to think carefully as to whether or not it wanted to remain a “tier-one” nation.19 By that it meant was Japan ready to do what was required of it by the US, to “stand shoulder-to-shoulder,” send naval groups to the Persian Gulf and the South China Sea, relax its restrictions on arms exports, increase its defence budget and military personnel numbers, maintain its annual subsidy to the Pentagon ($7 to $8 billion per year by way of “host nation” or “omoiyari” (sympathy) budget,20 press ahead with construction of new base facilities in Okinawa, Guam, and the Mariana Islands, and revise either its constitution or the way it is interpreted so as to facilitate “collective self defence,” i.e. merging its forces with those of the US for dispatch to regional and global battlefields. If Japan balked at any of this, Washington intimated, it would simply slide into “tier-two” status, and that, clearly, would be beneath contempt.

Just months after his December 2012 electoral triumph, Abe hastened to Washington. Though his reception at the White House was cold, across town at CSIS his Japan handler peers listened appreciatively as he responded to the Armitage challenge:

“Secretary Armitage, here is my answer to you.

Japan is not, and will never be, a Tier-two country.”21

He meant: We will do as we are told.

|

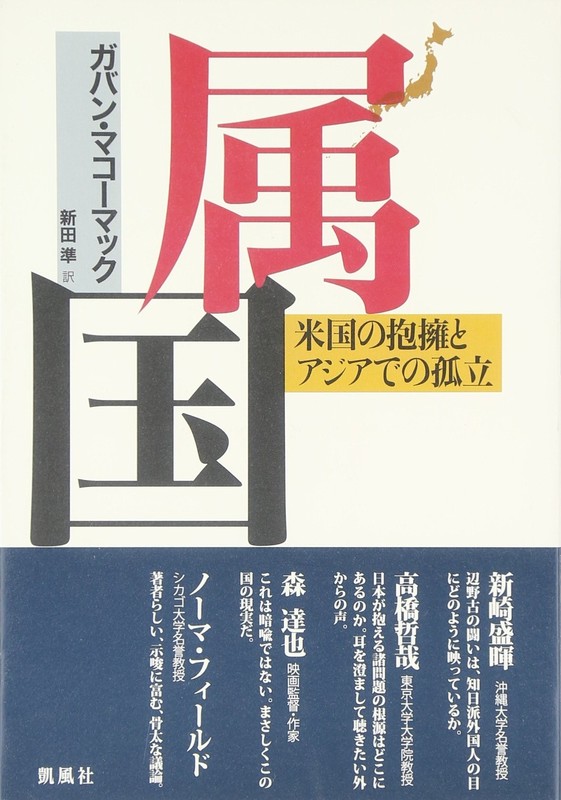

Zokkoku – Beikoku no hoyo to Ajia de no koritsu, Tokyo, Gaifusha, 2008 (Japanese edition of Client State, Japan in the American Embrace, 2007) |

The CSIS demands thereby were adopted as Japanese government policy. The long-established interpretation of the constitution was changed in 2014 – and fleshed out with a security legislation package adopted in 2015 – to allow Japanese forces under certain conditions to be dispatched abroad on missions of Collective Self-Defence (i.e. to behave as a real “Tier One” country). But if he thought that his general compliance on strategic and military matters would persuade Washington to withdraw its objections to his neo-nationalist ideology and his commitment to Yasukuni, he was wrong. When he went ahead, in December 2013, to make a formal Yasukuni visit the Clinton administration issued a stinging rebuke – publicly expressing “disappointment.” Challenged, he stepped back. Henceforth, and to this day, however painful it must be to him, he has kept away from Yasukuni. 22 Instead, he re-focussed his message. “Positive pacifism,” which he adopted as an alternative watchword, was music to Washington’s ears because it meant cooperation in US military and strategic agendas. However bizarre the notion, for Abe the United States was the epitome of “positive pacifism.”

Thus Abe during the years of his second government (from December 2012) abandoned his radical constitutional agenda and neo-nationalist principles to perform a purer form of clientelism, with no more talk of “taking Japan back” or of “going beyond the post-war system.” In April 2015, he was therefore (at last) honoured with a state visit to Washington, an address to a joint sitting of the two Houses of Congress, and a press conference with the president. The bilateral relationship was acclaimed as an “alliance of hope” and declared (by Joseph Nye) to be in “the best condition in decades.”23

By 2017, the priorities of his government were very different from those he had professed when first assuming office twelve years earlier. In this Clientelism Mark Two, the sometime nationalist fire-brand intent on remaking the state in accord with a grand post-Cold War, post-servile programme morphed into a faithful servant of the US cause, a conventional LDP leader,24 prioritizing the alliance even if it meant sacrificing his own domestic support base, as indeed he did, watering down his constitutional revision program to a feeble, contradictory minimum,25 and bowing to American pressure to adopt, in December 2015, a “final and irrevocable” solution to the Comfort Women issue by agreement with the government of South Korea, angering his supporters.

Following Donald Trump’s advent to the presidency in 2017, Abe paid especial care to nurture the bilateral relationship. With no other world leader did Trump so relish rounds of golf or consult so often, whether directly or by telephone. As the personal relationship seemed to flower, Abe committed Japan to a new level of incorporation in the projection of US hegemony over global land, sea, space, and cyber-space. In an impromptu, but revealing, exchange in November 2017, Trump had this to say,

“So one of the things, I think, that’s very important is that the Prime Minister of Japan is going to be purchasing massive amounts of military equipment, as he should. And we make the best military equipment, by far. He’ll be purchasing it from the United States. Whether it’s the F-35 fighter, which is the greatest in the world — total stealth — or whether it’s missiles of many different kinds, it’s a lot of jobs for us and a lot of safety for Japan and other countries.”26

Put on the spot, Abe responded saying, “we will be buying more from the United States. That is what I’m thinking.” After their meeting, Abe was true to his word, having cabinet confirm the Japanese purchases of several dozen F-35 fighters, two Aegis Ashore missile defense systems, and one, or more likely two, aircraft carriers. Already by the end of the fifth year of his second term, he had increased by 4.5 times (compared to the five preceding years) the amount spent by Japan on weapons and weapon systems, almost all of US make. And in 2018, the LDP (Abe’s party) called on government to double defence expenditure to reach the NATO (nominal) level of 2 per cent of GDP.27

Okinawa – The Client State’s (Reluctant) Client State

The price of Japan’s post-San Francisco Treaty “peace state” was Okinawa’s “war state.”28 Even after its nominal “reversion to Japan from US military control in 1972, it still constituted the base of the pyramid of military-firstism, Japanese subordination to American military power. The political history of Okinawa in the subsequent 46 years has been one of resistance to the assigned status of Client State of the United States’ Client State of Japan.

The two governments (US and Japan) made various agreements, in 1996, 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, and again in 2017, to construct on a reclaimed site offshore from Henoko on Oura Bay in Okinawa’s north a “replacement facility” for the Futenma Marine Corps base currently located in the middle of Ginowan township adjacent to the prefectural capital, Naha. The project was rejected by Okinawa from the start, first by a Nago City plebiscite in 1997, and since then by numerous resolutions of the Okinawan parliament and successive statements by representative public figures. However, in December 2013 then Governor Nakaima Hirokazu bowed to immense pressure from the Japanese government and consented, despite the pledge to the contrary upon which he had been elected, to grant permission for reclamation of a site at Henoko on Oura Bay in the north of the island for the Futenma replacement base. The prefecture was outraged. Nakaima was dismissed from office in a subsequent gubernatorial election, defeated by a massive 100,000 votes by Onaga Takeshi, who stood on a platform of opposition to any such construction.

Despite the clear expression of prefectural sentiment against it, preliminary site works were undertaken in 2015. They were delayed or blocked by various legal and administrative steps on the part of Governor Onaga, and completely halted through much of 2016. In December 2016, however, the Supreme Court ruled against Okinawa. Survey and construction works resumed in the following April and continued through mid-2018. Convoys of trucks, sometimes 300 or more in a single day, plied the Okinawan highways while ships laden with materials circled the island. Sea-walls snaked out across the Bay. The project steadily moved forward.

For Okinawa, in other words, Japan’s clientelist national polity called for transformation of one of nature’s greatest natural treasure-houses into a fortress from which the United States could continue indefinitely projecting its power over East Asia in accord with the San Francisco formula. It was, as I have noted,

“counter to the moves towards regional peace, cooperation and community, counter to the principle of regional self-government spelled out in the constitution, counter to the principles of democracy and counter to the imperative of environmental conservation.”29

In June 2018, the government made known its intention to commence the actual reclamation from 17 August. That prompted Governor Onaga to declare, on 27 July, that he was initiating formal steps for rescission of the reclamation license. However, with the strain of constant pressure and confrontation with the government of the country a likely contributory factor, Onaga fell ill, underwent surgery for removal of a cancerous pancreatic tumour in April and after a further brief spell in hospital died on 8 August. The prefectural revocation process nevertheless continued, and from 31 August works were again suspended.30

Again, however, the state moved quickly to strike down the prefecture’s protest. The government’s Okinawan Defence Bureau called on Ishii Kei-ichi, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, and Transportation, to review the revocation under the Administrative Appeal Act and to issue an order cancelling its effect. There could be little doubt of the outcome as one section of government was called upon to review and pronounce on the legitimacy of the acts of another. As the Ryukyu shimpo put it (unusually posting its own editorial on the web in English),

“To begin with, the Administrative Appeal Act was passed with the purpose of supporting citizens’ rights and interests when a government agency acts illegally or inappropriately. Therefore, the government itself cannot use the same law in this way … For the government to abuse the system made for a regular citizen by insisting that the ODB [Okinawa Defence Bureau, the Okinawan section of the Department of Defence] is a ‘private entity’ is tantamount to fraud. The government is once again taking unthinkably tyrannical measures …”31

A statement issued over the signatures of 110 administrative law specialists from throughout Japan declared the government to be acting “illegally … lacking in impartiality or fairness,” and that it “failed to qualify as a state ruled by law.”32 Fraudulent or not, on 30 October Minster Ishii did as was required of him, finding the rescission “unreasonable” and “likely to undermine relations of trust with Japan’s security ally, the United States.”33 He suspended the effect of the prefectural revocation order, whereupon, brushing aside outraged Okinawan protests, the Okinawa Defense Bureau (for the government) ordered works at Oura Bay resumed. After a two-month suspension, they resumed on 3 November.

In the interim, Tamaki Denny – widely seen as Onaga’s political heir, inheriting his commitment to stop Henoko works – was elected Governor. The election result, despite an unprecedented level of national government intervention to try to secure the election of a more amenable candidate, made clear the prefecture’s continuing refusal to be cowed. It was undoubtedly a bitter blow to Abe that the people of Okinawa should have overwhelmingly rejected his candidate for Governorship of Okinawa immediately after has own triumph in being elected re-head of his party and de facto head of government for three more years.

|

Tamaki Denny, elected Governor of Okinawa, 30 September 2018 |

The struggle between nation state and prefecture thus goes on. Despite the bitterness of that confrontation, it is the Okinawans, ironically, who take Abe (the Abe of Clientelism Mark One) literally in seeking to go “beyond the post-war system” and to “take back” Japan. For them, of course, it is Okinawa that is to be taken back. All attempts over decades by the two governments (including especially intense efforts by Prime Minister Abe through the seven years of his second term) to persuade, buy off, or intimidate the people of Okinawa into submission to the clientelist, military-first prescription have failed. The dispute will return to the courts in the near future, at which point the government can confidently expect to be victorious. However, even with the state’s more-or-less assured judicial victory, without Governor Tamaki’s consent, resumption of works at Henoko/Oura Bay seems improbable, for reasons now as much technical as political or ecological. Specialist engineers doubt that the massive concrete and steel structure planned, in its present design, could be stably imposed on the site. They insist (as did the prefecture in its formal statement of revocation of the Nakaima license,34 that for the project to proceed the original design would have to be fundamentally redrawn to take into account factors only recently come to light, such as the soft, “mayonnaise-like” floor of Oura Bay and the active fault line that bisects it.35

Whether Governor Tamaki will have the fortitude to withhold his consent as the government struggles to drastically revise its reclamation and construction plan remains to be seen. If the prefecture chooses to refuse cooperation at every step, court proceedings following court proceedings, the project will be indefinitely postponed and the US government may come to doubt its wisdom and viability. Such doubts may indeed already be spreading, as the editorial board of the New York Times’ unusually harsh denunciation of the base construction project as “an unfair, unwanted and often dangerous burden on Japan’s poorest citizens” suggested.36

However, a qualification has to be entered. Tamaki takes a narrow view of the Okinawan “base problem,” essentially confining his objections to the Henoko project. He takes no position on the helipad works in the Yambaru forest of the north or on the Abe government’s rapidly advancing plans for the extension of military (i.e., Japanese Self-Defence Force) facilities through the Southwest islands adjacent to Okinawa island itself, notably Miyako, Ishigaki, and Yonaguni. Moreover, he inherits from Onaga support for the “return” of Naha Military Port, promised by agreement between the two countries in 1974, an astonishing 44-years ago. Such “reversion,” like that of Futenma, was made dependent on construction of an alternative, for which the adjacent Urasoe City, like Nago in the case of Henoko, was designated. As “reversion” of Futenma Marine Air Station was predicated on construction of the much expanded and upgraded Henoko facility, likewise that of Naha Military Port was to mean major new base construction at Urasoe. On current estimates, that transfer might occur in 2028.37

Furthermore, Governor Tamaki was no sooner elected than he indicated a readiness to consider one of the key “Japan handler” demands for the Japanese client state: the transformation of military bases in Okinawa from single (US or Japan) management and use to “joint” facilities.38 The publication of his interview clarifying this stance appeared in the right-wing national newspaper, Sankei Shimbun, almost simultaneously with the report of the CSIS paper making precisely that demand as part of a design to reinforce the US-Japan alliance. By signalling readiness to consider the base-sharing and close cooperation of Japanese and US forces long favoured by alliance managers in Washington, Tamaki was consenting to a key part of the clientelist agenda.39 He confirmed this pro-Security Treaty, pro-base stance in speeches in Tokyo and New York in November 2018.40

Clientelism, Mark Three? 2018 –

Late in 2018, the question is this: is it possible, as Abe Shinzo contemplates the agenda for his third term as Prime Minister, that he might begin to formulate a Mark Three version of the Abe state, establishing a measure of independence of his erratic and overbearing trans-Pacific partner without antagonizing it, and seeking a new, substantially autonomous role as member of an East Asian or Northeast Asian community?41 Can he square the circle?

While struggling to maintain his posture of loyal follower, crucial support of the US-led alliance system directed against Russia, China, and North Korea, from 2017 Abe began to show interest in alternative, even opposite schemes, notably the Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin designs for a post-San Francisco Treaty order.42 It meant paying attention to the Russian and Chinese-led BRICS, the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the (Russian) Eastern Economic Forum.

Meeting at Vladivostok in September 2017, China, Russia, North and South Korea, and Japan (Abe himself), in the absence of the United States, discussed plans for opening multiple lines of cooperation and communication across the region, extending Siberian oil and gas pipelines to the two Koreas and Japan and opening railways and ports linking Japan and Korea across Siberia to China, Russia, and beyond. South Korea’s President Moon also elaborated on what he called “Northeast Asia-plus,” extending and consolidating those vast, China- and Russia-centred geo-political and economic groupings through promotion of “nine bridges of cooperation” (gas, railroads, ports, electricity, a northern sea route, shipbuilding, jobs, agriculture, and fisheries).43

Even before the Vladivostok meetings, Japan and Russia had defined a set of “priority projects” for cooperation, ranging across the development of Eastern Siberia and Northern Russia, especially resources (oil and gas), but also infrastructural, at their most ambitious including a railway crossing by tunnel under the Soya [La Perouse] Strait between Hokkaido and Sakhalin and a bridge across the Mamiya [Tartar] Strait between Sakhalin and Siberia (just 7.3 kilometres at its narrowest point), establishing a through rail link from Japan via the Trans-Siberian and BAM railway systems to China, Russia, the Indian sub-continent, the Middle East and Europe,44 including a “through Korea” (i.e. across North Korea) rail link.

Under the Vladivostok formula, the Beijing Six Party Talks formula of 2003–2008 would become “Five Plus One,” with the United States reduced to non-participant “observer.” Unstated, but plainly crucial, North Korea would accept the security guarantee of the five (Japan included), refrain from any further nuclear or missile testing, shelve (“freeze”) its existing programs and gain its longed for “normalization” in the form of incorporation in regional groupings, the lifting of sanctions and normalized relations with its neighbour states.

For Japan, the various grand designs emanating from Beijing, Moscow, or Seoul held the potential for it to open a path to re-negotiate its relationship with the US beyond clientelism and towards an equal bilateral relationship, with bases liquidated, leading in due course to diplomatic recognition of North Korea and the resumption of the Japan-North Korea reconciliation process that was begun but then suspended under Prime Minister Koizumi (in 2002). In such a scenario, North and South Korea would become points of Japanese engagement in the process of Northeast Asian and Siberian cooperation and community building, towards the ultimate goal of a post-San Francisco regional peace and cooperation community replacing the “hub and spokes” US-hegemonic, San Francisco Treaty system. The Vladivostok conferences (of 2017 and 2018) showed that grand schemes, hitherto little more than pipe dreams, were on drawing boards in Moscow and Tokyo as well as Beijing, Seoul, and Pyongyang.

China contacts notably warmed in 2018. The two countries are said to have agreed at Vladivostok in September 2018 to coordinate their response to US trade war pressures. Weeks later, Abe undertook the first visit by a Japanese leader to China since 2011, heading a Japanese delegation comprising not only Foreign and Trade Ministers but a large contingent of Japanese business leaders. Abe and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang spoke of transformation of the bilateral relationship “from competition to collaboration,” and discussed possible projects for collaboration, including “about fifty” infrastructural projects in third countries around the world.45 They also agreed to open negotiations on East China Sea cooperative development, implying a readiness to set aside the conflicting claims to the Senkaku/Daioyu islands that for seven years had proved an insuperable obstacle to negotiations.

|

Prime Minister Abe with President Xi Jinping, Beijing, October 2018 (Photo by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tokyo) |

For Abe to proceed with such plans would be to relativize and downgrade the Ampo security relationship, something which he has repeatedly insisted he will not do.

The delegation of Japanese executives to Beijing that Abe led in 2018, at 500-strong – was even larger than the Hatoyama-Ozawa mission of 2009 that stirred virtual apoplexy on the part of the US government and a reversal that swept Hatoyama’s government from office less than a year later. Then, Hatoyama was suspected of a scheme to recast the region’s diplomatic and security frame by construction of a Northeast Asian community. Now, Japan handlers in Washington must wonder, as they contemplate the Abe celebrations in Beijing, whether they are facing a re-run of Hatoyama.

The newly warmed and cooperative Japan-China relationship does not sit easily with the steadily chilling US China one. The Abe mission occurred just weeks after a major speech by US Vice-President Mike Pence that has been widely seen as marking a new US-China Cold War.46 Pence denounced China’s “whole-of-government approach” apparently designed to “push the United States of America from the Western Pacific,” and declared intent to maintain and if necessary intensify punitive sanctions against it. Japan’s commitment to a new East Asian collaborative system certainly struck a different note. It remains to be seen how Abe, evidently chafing at the clientelist bit, will deal with US pressure for all countries wishing to maintain close ties with the United States to drastically cut their trade and investment links to China.47

Conclusion

Abe’s initial attempt (Clientelism, Mark One) to liquidate the post-war, American-granted regime and construct in its stead a state that blended military, diplomatic and economic servility to the United States with a Shintoist, “beautiful” and “new” Japan, and a comprehensively revised constitution. It was plainly unacceptable to Washington. Clientelism, Mark Two, of 100 per cent support for the US, reached a peak at the time of “America First” in 2017, and it seemed for a time that however erratic, violent or damaging (to Japan) the policies required, Abe would cling to it. Although vacillating on the question of state posture, Clientelism Mark One and Mark Two versions shared much common agenda, setting aside the democratic, citizen-based, anti-militarist Japan, widening state prerogatives, circumscribing citizen rights, reinforcing national security. However, as he began his third and final term, there were signs that Abe might be close to the limits of his tolerance.

CSIS’s 2018 report made elliptical reference to “cracks” that were “starting to show in the alliance.” One wonders, what cracks? Japan is known to have been unhappy with the US over the Trump withdrawal from TPP and later from the Iran nuclear agreement and the moves in the direction of trade war with China, as well as Trump’s apparently casual comment to a Congressman in September 2018 that the current “good relations with the Japanese leadership” might end “as soon as I tell them how much they have to pay,”48 which must have shocked, and perhaps angered Abe. Likewise there have been doubts in Tokyo as to whether the US and Japan were really on the same page when it came to North Korea policy, perhaps especially once Trump began to speak of his “love” for the North Korean leader. Such doubts may have led to the “secret” (i.e. without American consent) meetings between Japan and North Korea in Vietnam in July 2018.49 If such developments are what CSIS refers to as “cracks,” they appear to be highly consequential ones, with the potential of widening onto a fissure that could threaten the San Francisco treaty system.

Prime Minister Abe declares repeatedly that Japan is a country of universal values, democratic, recognizing basic human rights and the rule of law, while virtually all members of his government belong to an organization, Nihon Kaigi, whose rightist, blend of neo-conservatism, neo-nationalism, and historical revisionism would in any other contemporary democratic state be seen as extremist or ultra-nationalist and therefore beyond the pale. To be able to advance universalist democratic principles, and to play the global role of which it ought be capable in the struggle for the cause of humanity in an epoch of climate change, global warming, and species loss, for the outlawing of nuclear weapons, the substitution of renewables for nuclear and fossil fuel energy systems, and for regional and global peace, will depend on Japan first accomplishing national sovereignty, a path beyond clientelism. How to get a government that will do this is the problem the Japanese people face.

The series of high-level international conferences in 2018 addressing Korean issues show how suddenly war preparation can give way to peace cooperation and long-frozen diplomatic logjams break-up. If a peace treaty to end the Korean War can suddenly – even shockingly as was the case in 2018 – be put onto the bargaining table, so can the closure and return of the American bases in Okinawa, and the liquidation of the dominance of Japan and Korea by the United States that Hirohito in 1947 and Joseph Nye in 1995 insisted was indispensable. Clientelism need not be forever.

Notes

The State of the Japanese State: Contested Identity, Direction and Role Folkestone, Kent: Renaissance Books, 2018.

Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, New York, Verso, 2007 (in Japanese from Gaifusha, Korean from Changbi, and Chinese from Social Science Academic Press of China, all 2008). See especially the discussion in the Japanese edition.

For my analysis of the British and Australian cases, and brief reference to Korea, Israel, and Latin America, see my “Zokkokuron,” in Kimura Akira and Magosaki Ukeru, Owaranai ‘Senryo’ (The Unending Occupation), Kyoto, Horitsu Bunkasha, 2013, pp. 18-38. (English version at “Japan’s Client State (Zokkoku) Problem,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, June 24, 2013).

See our Tenkanki no nihon e – Pakkusu Amerikana ka, Pakkusu Ajia ka, Tokyo, NHK Shuppan shinsho No 423, Tokyo, January 2014.

Shirai Satoshi, Kokutai-ron – Kiku to seijoki, Tokyo, Shueisha shinsho, 2018. And for a short statement of his thesis, “Okinawa to kokutai,” Days Japan, vol. 15, No. 10, October 2018, pp. 4-11.

Terashima Jitsuro, “Noryoku no ressun,” No 192, “Chugoku no kyodaika kyokenka wo seishi suru, Nihon no kakugo,” Sekai, April 2018, pp. 42-47 at p. 42. See also IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2018.

Boei mondai kondankai, “Nihon no anzen hosho to boeiryoku no arikata – 21 seiki e mukete no tenbo (The Modality of the Security and Defence Capability of Japan – The Outlook for the 21st Century), Higuchi ripoto, 12 August 1994.

Gavan McCormack and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands – Okinawa versus Japan and the United States [Rowman and Littlefield, 2012, second, expanded edition, 2018], p. 64.

Richard L. Armitage and Joseph S. Nye, eds, “More Important than Ever: Renewing the US-Japan Alliance for the 21st Century,” Washington, CSIS, October 2018.

MacArthur told a US Senate Committee on 5 May 1951, “If the Anglo-Saxon was say 45 years of age in his development, in the sciences, the arts, divinity, culture, the Germans were quite as mature. The Japanese, however, in spite of their antiquity measured by time, were in a very tuitionary condition. Measured by the standards of modern civilization, they would be like a boy of twelve as compared with our development of 45 years.” (John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War ll, New York, W.W. Norton, 1999, p. 550). MacArthur’s view matched that of Hirohito, who referred disparagingly to the Japanese people as “lacking in education,” marked by “a willingness to be led,” and prone to “sway from one extreme to the other.” (most likely between April and July 1946, see Dower, “A message from the Showa emperor,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 31, 4, 1999, pp. 19-24.)

“Memorandum of conversation,” 9 July 1971, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, vol. 17, China, 1969-1972.

Richard Armitage and Joseph S. Nye, “The US-Japan Alliance: Anchoring Stability in Asia,” CSIS (Centre for Strategic and International Studies), August 2012. This report, published months before the 2012 presidential election, laid out the position expected to be the kernel of East Asian policy for the incoming administration.

Gavan McCormack and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa confronts Japan and the United States, pp. 193-6.

While abandoning Yasukuni, he compensated by performing comparable, emperor-centred rituals at Ise Shrine.

See discussion in Kaji Yasuo, “”Abe ‘kaiken’ an no meiso ga shisa suru mono,” Sekai, April 2018, pp. 178-190.

Retaining Article 9’s two current paragraphs but adding a third, declaring the legitimacy of the Self-Defence Forces as a National Defence Army (kokubogun). The adoption of such a third clause implied that the SDF until the moment of revision had not been constitutionally legitimate. (At time of writing the formal constitutional revision package was yet to be announced, but this author assumes it will be minimalist and in line with the pattern suggested here, designed to establish the principle of revision while postponing the “real” agenda to a more propitious time.

“Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Abe of Japan in Joint Press Conference,” Tokyo, Japan,” The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, November 06, 2017.

“Boeihi ‘tai-GDP 2%’ meiki, jimin boei taiko teigen no zenyo hanmei,” Sankei shimbun, 25 May 2018.

For details see my “The Abe state and Okinawan protest – High Noon 2018,” The Asia-Pacific Journal- Japan Focus, 7 August 2018.

“The Japanese government suing to allow land filling is a reckless trampling of democracy,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 18 October 2018 (in English).

“Henoko shin kichi, gyoseiho kenkyusha 110 nin no seimeibun zenbun,” Okinawa taimusu, 31 October 2018.

Kyodo, “Okinawa governor meets top gov’t official over US base transfer,” The Mainichi, 6 November 2018,

See, for example, the letter from Governor Onaga to Nakashima Koichiro, head of the ODB, “Futenma hikojo daitai shisetsu kensetsu jigyo ni kansuru sokuji koji teishi yokyu nado ni tsuite, ” Prefectural press release, 17 July, 2018

The Editorial Board, “Toward a smaller American footprint on Okinawa,” New York Times, 1 October 2018.

“Tamaki Deni-shi, Jieitai to Beigun no kichi kyodo shiyo kyogi mo, intabyu de hyomei, okinawa ken chijisen,” Sankei shimbun, 2 October 2018.

To the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan on 9 November and to New York University on 11 November. See discussion in Kihara Satoru, “Okinawa, Bei sentoki FA18 no suiraku wa nani o shimesu ka,” Ari no hitokoto, 15 November 2018.

The following discussion of the Vladivostok meetings follows that in my The State of the Japanese State, pp. 145-149.

“Moon daitoryo,” op. cit.; James O’Neill, “North Korea and the UN sanctions merry go round,” New Eastern Outlook, 18 September 2017.

At 43 kilometres long and up to 70 meters deep, the Soya Strait would be an expensive project but probably no more technically difficult than the existing Japanese Seikan tunnel under the Tsugaru Strait between Honshu and Hokkaido (53 kilometres long and 140 meters deep). Kiriyama Yuichi, “Shiberia tetsudo no Hokkaido enshin, Roshia ga keizai kyoryoku de yobo,” Shukan ekonomisuto, 15 November 2016, p. 22.

Yohei Muramatsu, “Sino-US trade war casts shadow over economic forum in Beijing,” Nikkei Asian Review, October 27, 2018. Steven Lee Myers and Motoko Rich, “Shinzo Abe says Japan is Chna’s ‘partner’ and no longer its aid donor,” New York Times, 26 October 2018. See also David Hurst, “Abe wants ‘new era’ in China-Japan relations,” The Diplomat, 26 October 2018.

Hudson Institute, “Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy toward China,” Foreign Policy, 4 October 2018.

It seems likely that Japan will soon be put to the test on this if the US insists, as expected, on inclusion in the bilateral US-Japan trade deal about to be negotiated of a clause such as in the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) adopted on 1 October 2018 blocking any agreement with China not endorsed by the US. (Lee Jeong-ho, Keegan Elmer, and Zhou Xin, “China ‘threatened with isolation’ by veto written into US-Mexico-Canada trade deal,” South China Morning Post, 3 September 2018.)

Tyler Duirden, “USDJPY tumbles after Trump hints at Japan trade war next,” Zerohedge, 6 September 2018.

Danielle Demetriou, “Japan and North Korea held secret meeting as Shinzo Abe ‘loses trust’ in Donald Trump,” Telegraph News Online, 29 August 2018.