Poetry can help build nations. It is doing so today in Timor-Leste (East Timor), where themes of resistance to foreign rule, Indigenous re-assertion, language and the shape of the new nation intertwine. One of the country’s leading poets, Abé Barreto Soares, embodies the way these themes come together.

|

Abé Barreto Soares. Image via Facebook. |

Although it declared its independence from Portugal in 1975, Timor-Leste (East Timor) only regained that independence in 2002, following a brutal Indonesian invasion, 24 years of military occupation, a referendum that opted for self-rule, and a three-year United Nations interim administration.

Barreto Soares’ personal history mirrors that of his country: a young boy when Indonesia invaded, his family suffered deaths and other losses. He was educated in the Indonesian school system and at an Indonesian university, writing his first poems in Indonesian before coming to Canada as an exchange student. There he obtained refugee status and spent most of the 1990s as a Canada-based campaigner for Timorese independence, all the while continuing to write poems in Indonesian, Portuguese, English, and increasingly in Timor-Leste’s national language, Tetum. He returned to Timor-Leste in 2000 and worked as a translator for the United Nations, interpreting between English and other languages for internationals, then became official interpreter to a president. Through all this, he never ceased writing. He is a leader in Timorese poetry and music, which are helping to write and sing a new nation into being.

“My contribution since the resistance era is something that I look back on that was worthwhile in the sense of using poetry and music as a tool for the freedom of Timor–Leste,” Barreto Soares says in an interview. “That spirit remains alive within me and that spirit is what keeps me going.”1

Barreto Soares exemplifies Edward Said’s notion of reinscription, a post-colonial desire among writers for “the rediscovery and repatriation of what has been suppressed … by the process of imperialism.”2 The Indonesian occupation of Timor-Leste (1975-1999) saw the deaths of as many as 200,000 people, over a quarter of the population. It was accompanied by an attempt to eliminate or “museumize” indigenous Timorese traditions, assimilating Timor-Leste into Indonesia culturally as well as physically. Timorese writers such as Abé Barreto Soares strove during the occupation to preserve the idea and the Indigenous traditions of Timor-Leste in words and song.3 Since the restoration of independence, they have tried to connect the nation being built to a longstanding Timorese poetic tradition, to reinscribe and revive what colonial occupation tried to destroy.

This essay examines the work of Abé Barreto Soares through the poet’s own words, under three headings: his years in exile, where he developed a poetic voice evoking love for the far-off Timorese homeland and a determination to maintain its identity even under conditions of near-genocide; the post-2002 development of a literary and cultural identity in independent Timor-Leste; and the current role of poetry in language and national identity.

Exile years

Barreto Soares was one of three Timorese university students who in the early 1990s came to Canada on student exchange programs and then defected. Other young Timorese were sent to other countries. All three Canada-bound students had passed through screening and were considered to be the fulfillment of the Indonesian government’s hopes to win the “hearts and minds” of the younger generation of Timorese. Indonesian authorities did not have high hopes of winning support from the “1975 generation” of Timorese who had led the country’s struggle for freedom from Portugal and subsequently from Indonesia. But they did hope to win support among younger Timorese.4

This strategy drew on colonial models. Indonesia’s colonial ruler, the Netherlands, attempted an “ethical policy” based on educating young Indonesians in the hopes that they would be absorbed into Dutch culture and become loyal Dutch subjects. A new educated Indonesian elite, colonial planners hoped, would be “associated” with the colonial power and thus help to maintain colonial rule. The policy did not succeed: Indonesian university students, like their counterparts across Asia and Africa, became the vanguard of a new wave of anti-colonial nationalism in the early twentieth century. Among them were Sukarno, the country’s first president, and Mohammad Hatta, its first vice-president, who honed his nationalism while a university student in the Netherlands. Indonesian nationalist exiles followed the lead of earlier nationalists like José Rizal of the Philippines in creating literature that proclaimed the existence of a Philippine nation through prose, poetry and music long before the formal proclamation of Indonesian independence in 1945.5

Indonesian strategy in Timor-Leste started off as straightforward military repression but in the early 1980s began to stress education of young Timorese in the hopes of promoting cultural assimilation with Indonesia. Just as the Dutch “ethical policy” ended up creating a new generation of Indonesian nationalism, the new Indonesian assimilation effort helped to create what Timorese activists would come to call “a new generation of resistance,” a “clandestine front” of younger Timorese, educated in Indonesian schools in the Indonesian language but fighting for Timorese independence. They did so even in universities in Java, where the brightest Timorese youths were sent for higher education. There, some of them formed Renetil, the National Resistance of Timorese Students.6

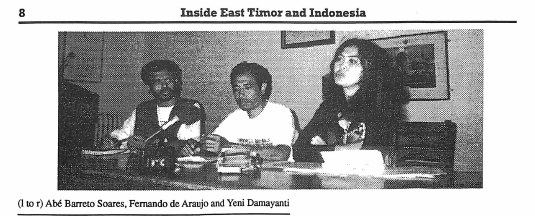

|

Barreto Soares with Renetil founder Fernando “Lasama” de Araújo and Indonesian human rights activist Rosa Yeni Damayanti, at an event in 1998 in Toronto. From Canadian Action for Indonesia and East Timor (CAFIET) papers. |

Barreto Soares was among this group of Timorese studying in Indonesia. He was also acceptable to the Indonesian authorities as sufficiently reliable to be approved for a term of study abroad organized through Canadian Crossroads International. In this, he was supported by the Indonesian-appointed governor of the East Timor “province,” Mario Carrascalão, who played a complex role as loyal backer of Indonesian rule and advocate for greater Timorese autonomy within Indonesia, while also fostering education and acting as patron and sponsor for several young Timorese – regardless of their political stripe.

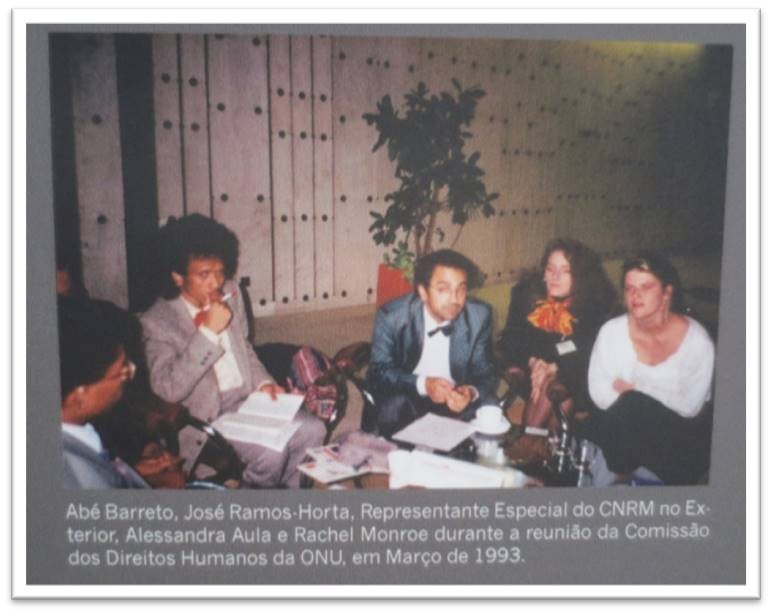

After the infamous Santa Cruz massacre of 12 November 1991, where Indonesian soldiers shot and killed some 250 pro-independence protesters, Barreto Soares was able to obtain refugee status in Canada. In December 1991, at an Indian restaurant in Toronto’s Bloor and Bathurst neighbourhood, he met exiled Timorese diplomatic leader José Ramos Horta, who recruited him as the Canadian representative for the National Council of Maubere Resistance,7 the pro-independence coalition formed by guerrilla leader Xanana Gusmão inside Timor-Leste. He would remain in this role until 1998, when he left Canada for Portugal and Macau. Barreto Soares was one of the first to publicly spell out the Timorese strategy of fighting against Indonesian colonial rule on “three fronts” – guerilla resistance inside the country, a “diplomatic front” outside, and a clandestine front of young Timorese working underground and connecting the other two fronts.8 He toured North America and Europe on behalf of CNRM, testifying among other places at the UN Commission on Human Rights in Geneva.

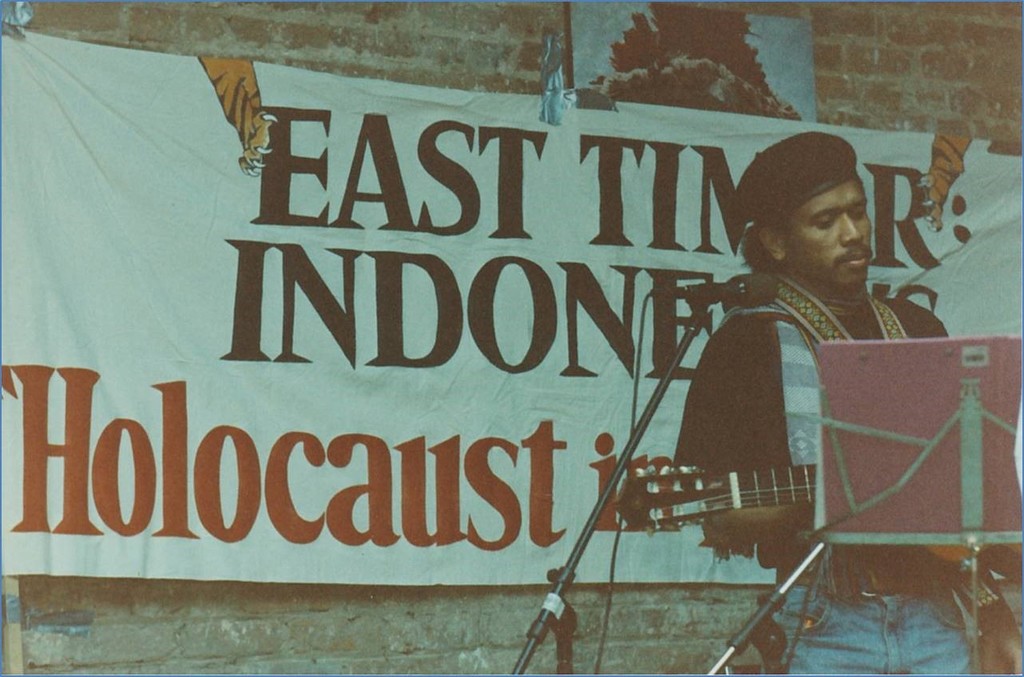

Exile was not easy. There were no funds for supporting Timorese refugees, and their devotion of time to the struggle left them little chance to earn money. The role of exile was far from luxurious. Meals were often few and far between. “It was a very hard time that I went through but it was really worthwhile to be in the struggle,” Barreto Soares recalls. He and fellow refugee Bella Galhos were not able to continue as university students in Canada, instead becoming full-time activists.9 Where Galhos concentrated on public mobilization, Barreto Soares worked more quietly and continued to stress cultural themes. In particular, he corresponded with other young Timorese exiles; formed the musical duo Abé ho Aloz with a Canadian musician, the late Aloz MacDonald; and wrote poetry for English and Portuguese language publications. He published two books of poetry: Menari Menggelilingi Planet Bumi (“Dancing around the Planet Earth”) in the Netherlands in 1995 and Come With Me Singing in a Choir, published by the Australia-based East Timor Relief Association in 1996.

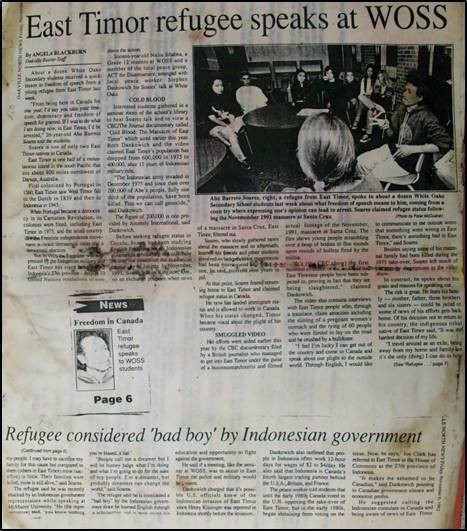

|

Newspaper clipping from Oakville North News (Ontario, Canada) about a talk by Barreto Soares in a local high school. Image from East Timor Alert Network. |

|

Barreto Soares with José Ramos Horta and solidarity activists at the 1993 United Nations Commission on Human Rights meeting, Geneva. Image from public exhibit at the Archives and Museum of the Timorese Resistance (AMRT), Dili, Timor-Leste. |

|

Barreto Soares in performance in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 1990s. Image from East Timor Alert Network files. |

Like other activists in the diaspora, Barreto Soares worked closely with a growing network of solidarity groups campaigning in support of the Timorese independence movement. He formed especially close ties with members of Canada’s East Timor Alert Network, founded in 1987 by photojournalist Elaine Briere. For many Timorese, warm memories of these ties endure. The words of former president Taur Matan Ruak are one example: “Many friends of Timor-Leste organized and led networks of support to the Resistance within their countries’ civil societies. They helped collect financial and other types of material support, and mobilized the international public opinion against the occupation of Timor.”10 Barreto Soares echoes that sentiment: “From the bottom of my heart I would like to thank all friends who have shown their great solidarity from the early years up to independence,” he says. “We don’t forget these friends. I would like these Canadian friends to come back to Timor-Leste as tourists. I would do my best to be a good host for them.”

Writing, he says, was the key to surviving exile: “My poetry saved my life from being lonely. Writing was a therapy for me. And that struggle was also the source of inspiration.” The poet’s yearning for the Timorese homeland and the continued survival of its indigenous cultures is evident in one poem he wrote while living in Toronto, “I saw my own reflection,” which evokes the sacred Timorese mountain Ramelau.

I saw my own reflection (1991)11

Ramelau

I came over to your

transparent pond

At its shore

I saw my own reflection

naked

welcoming me

then told me

the winding story

of the roots

of my seed

Other poems spoke of resistance and of suffering. Several of them portrayed Timor as a woman who suffered but remained, in the words of one poem, “steadfast” in the fight for survival. Timorese activists who fought on despite some of the longest odds imaginable would eventually win the freedom of that land – of the mountains and valleys that Barreto Soares wrote and sang about.

Timorese culture after the restoration of independence

In 1998, Barreto Soares left Canada for other places of exile, Portugal and the former Portuguese island colony of Macau. The same year saw the fall of longtime Indonesian dictator Suharto, toppled by Indonesian student protesters and defections from the governing elite of Suharto’s “New Order” government. The new Indonesian president, B.J. Habibie, agreed to allow the United Nations to sponsor a referendum that met the longstanding Timorese demand for a choice between Indonesian rule and independence. On a massive turnout of 98% of the population, 78.5% opted for independence. The Indonesian army created and armed militia groups that tried to derail the vote by intimidating people, killing some, injuring others, and deporting many to Indonesian West Timor. Militias also burned down much of the country’s infrastructure. But international pressure forced Habibie to invite a UN-authorized peacekeeping force, and the UN formed a Temporary Executive Authority (UNTAET) that governed Timor-Leste from 1999 to 2002.12

Barreto Soares soon returned to Timor-Leste and was reunited with his family and his people. Working a day job for UNTAET and the UN missions that stayed on in an advisory capacity until 2012, he was the most sought-after translator in the UN’s “Obrigado Barracks” compound (a play on language evoking the Portuguese/Tetum words “Obrigado Barak,” or many thanks). He went on to become the official interpreter for Taur Matan Ruak, president of Timor-Leste from 2012 to 2017, where former colleague Bella Galhos also worked as an advisor. Barreto Soares praised Galhos for her role as founder of the Leublora Green School in Maubisse, a town in the mountainous interior country to the south of Dili.13 “I am really keen on seeing her promote environmental awareness,” he says.

|

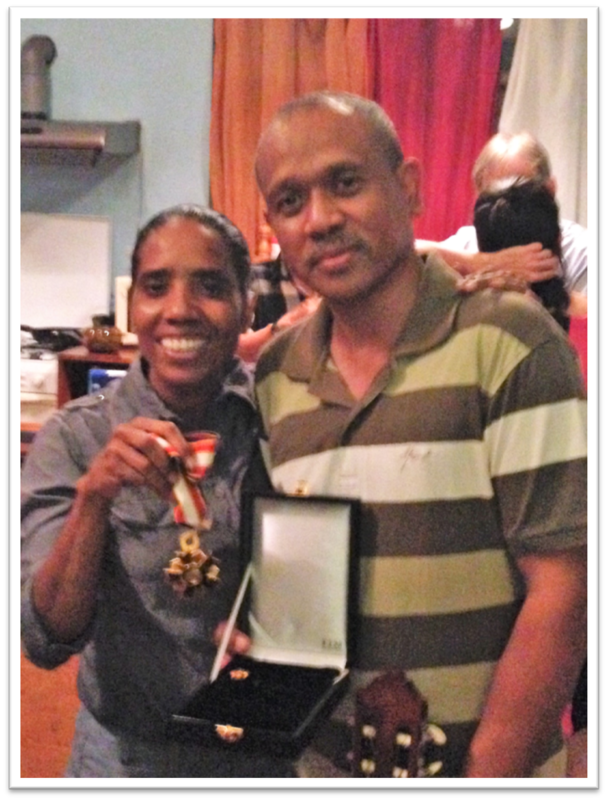

Barreto Soares and Bella Galhos with the Order of Timor-Leste medal, awarded to the East Timor Alert Network/Canada, 2015. Photo: David Webster. |

Timorese independence had been painted as a “lost cause” throughout the Indonesian occupation. Now, the impossible dream had come true. Amidst celebration, Barreto Soares and others also dreamed of building a new literary culture that combined Timorese oral traditions with international written and musical influences. They had worked to maintain Timorese cultural identity in exile while it was often restricted in Indonesian-ruled Timor. Some, playfully, dubbed this the “frente creativa.”

After independence in 2002, these poets, musicians and storytellers continued to dream. “In the era of independence this spirit continues to be alive within me, keeps on burning, and I find that I continue with that spirit,” Barreto Soares says. He evoked the feeling and his new poetic project in “The Dreams of Crazy Poets,” a short poem that nodded to both Indigenous traditions (the bidu and tebe dances) and a global spirit of poets joining hands around the planet.

The Dreams of Crazy Poets (Feb. 2009)14

The dreams of poets are carried on, and they extend their hands to each other

The dreams of poets bidu15 and tebe16 circling around Planet Earth with joy

The dreams of poets wake me up

As well as the crowd who are still soundly sleeping

Global influences on Barreto Soares’s poetry abound, from the 1989 film Dead Poets Society to Lebanese writer Kahlil Gibran to Pablo Neruda and Eduardo Galeano.17 Of Dead Poets Society, which he saw before coming to Canada, he says “I dreamed of setting up the same kind of group, so that some time when Timor was free I would establish a club like that.”

In 2008, he fulfilled that dream by establishing a cultural study club. The final impetus to create the MSB club (from the first letters of the words mind, soul, and body) came after his performance at Indonesia’s well-known Ubud writers’ festival in 2007. The club drew on students in the English department at the National University of Timor Lorosa’e (UNTL). A music club followed soon afterwards. He published poems and encouraged younger writers, and performed remixed versions of Tetum-language songs first written in Canada.

|

Barreto Soares and band perform in Dili in front of an image of Timorese poet Fernando Sylvan. Image via Facebook. |

“This was a good chance to set up a small club promoting Timorese culture using English, Portuguese, Tetum and other Indigenous languages to promote the future of Timor-Leste, to promote a new fighting for freedom after independence,” he says. “So music continues to be with me after my long journey as a poet, as a musician, and as a translator.” He went on to have a poetry show on radio RTL for ten years, which he recently resumed on Radio Liberdade Dili, based in the Timorese capital. The poetry broadcast is in his words “vibrant, alive because it is spoken,” drawing on Timorese oral traditions and able to reach a wide audience due to its orality. “Being aware of the oral tradition of Timor-Leste is needed to make yourself heard. Radio is crucial. Radio plays a very important role…. It gives me hope that poetry will continue to flourish, that the flame of poetry will continue to burn.”

Poetry, Barreto Soares believes, needs to be taught in schools. “When you talk about human development, the early age is the age when poetry plays an important role in building character,” he says. Still, “poetry will flourish no matter what because of the poets who write it.”

|

Barreto Soares in the radio studio. Image via Facebook. |

Poetics and language

Flourish is a word Barreto Soares returns to. When in 2006 there was internal violence amidst a political crisis in Timor-Leste, he wrote the poem “Flourish Everlasting” about the need for reconciliation between clashing groups. Peace, in this image, emerges from a devastated and desolate land which grows green again – where the land can flourish.

Flourish Everlasting18

Everything will be crushed

Everything will be broken

Everything will become dusty

New buds will appear, the flat land flourishing

We will pray

We will sing the songs of ancestors

We will tebe

We will bidu

circling the stones of the sacred house

A big mat will be spread out

We all will sit down

Our heads will cool

Our hearts will be soft

telling the truth

recounting the wrongdoings

The happiness of love will appear

The beauty of peace will be green

Flourish and flourish

The poetry of Abé Barreto Soares, in other words, still speaks to current politics, still evokes the land and peace and indigenous traditions – here seen again though dance.

He points here to a poetic inspiration much closer to home: Francisco Borja da Costa, a Timorese poet and composer of the national anthem who was killed as Indonesian paratroopers landed in Dili on 7 December 1975. Borja da Costa’s poem “The Maubere people should not be slaves any more” is widely known, but most citations of it stress the nationalist cry of the opening stanzas. Barreto Soares, on the other hand, says he was “particularly intrigued by the fifth stanza,” which reads in part: “We must nourish a new life to forget that our people were slaves / We must irrigate the soil…. / We must from this trampled soil create a new person.” The idea of creating a new world and a new person from “this trampled soil,” he says, can be linked to Che Guevera’s ideas of creating a “new man” in Cuba and to the revolutionary words of “the Man from Nazareth.” There are links, also, to the words of Eduardo Mondlane of Mozambique and Amilcar Cabral of Guinea-Bissau, who combined the roles of revolutionary and writer. “So poetry in this sense has the sense of revolution. Poetry has the power of revolution. Poetry has the power to rock the boat. Poetry is a revolutionary act.”

The land, its connection to the people, and its sacred character, resound in Flourish Everlastingly. Barreto Soares offers a quick Tetum lesson. He speaks the word “sama rai” – step on the soil. Then “ha’u sama rai,” I step on the soil. “So you consider yourself as a plant growing from the soil.” Then “ha’u hamrik metin,” I firmly stand on the soil. And finally, the more poetic “ha’u tuba-rai metin” – I firmly step on the soil. Humans and the environment are linked, inseparable. “So the concept of terra, the concept of land, I try to make a comparison with the indigenous people of North America … for them land is a sacred thing.”

|

House and flag on the road from Dili to Liquiça, 2015. Photo: David Webster. |

So too, he says, in Timor-Leste. Timorese traditions often evoke the uma lulik, the sacred house – a theme that Timorese scholar Josh Trindade has explored.19 “The uma lulik is the centre, it is the place where you uphold the essence of the land, the essence of nature,” Barreto Soares explains. “So your connection with nature is sacred. You glorify the essence of the land, your connection with the land.”

While rooting his work firmly in Timorese soil, Barreto Soares also looks outward. He shifts easily from one language to another, playing with tongues, writing in Tetum – “the language of my soul, the centre of my soul” – Indonesian, Portuguese, English. And he also writes in some of Timor-Leste’s other indigenous languages. “The mother tongues are strongly alive,” he says, “because they are the language of the soul of the nation. I am from four ethnic backgrounds, I have Makassae blood in myself, Bunak blood in myself, Kemak blood in myself, Galole blood in myself. I am fluent in Bunak, I am fluent in Galole.” And so he has written in Galole and Bunak, offering short aphorism style work in both languages, and is learning the others. “So I see that any Timorese who has the passion for writing, he or she can be writing in Makassae or Bunak or Mambai, because those are the languages that are alive in Timor-Leste. And if he or she chooses to write in Indonesian that’s fine, or in English that is welcome too…. So it doesn’t matter what language a poet chooses to write, it is about the inner voice, the voice of the crocodile.”

“This is the beauty of mastering languages,” he adds, “that you can switch your thoughts from one language to another. In the concept of Timor-Leste, you become the lia-na’in. Lia-na’in in the sacred house concept means you are the owner of the words. I am the modern lia-na’in. The lia-na’in is the traditional poet. The modern poet is the modern lia-na’in, the keeper of the words…. The role is as a spiritual man, as a visionary man in the society, so that is lia-na’in.” Barreto Soares is consciously trying to lead this role, to mentor other poets. “This is the legacy that I would like to leave behind.”

His work also helps shape the future of the Tetum language, which lacks a strongly-developed written or scientific literature but which is developing fast. In the years after independence was restored in 2002, Timorese activists could be seen translating from Tetum into Indonesian on a regular basis, because the latter had more technical terms. That has changed as Tetum takes a firm hold. Tetum-language poetry, meanwhile, is affecting the development of the language in a process reminiscent of the role of early 20th century poets writing in Indonesian, which was then being codified as a “modern” written language.

“When you write poetry you create new expressions,” Barreto Soares says, noting that there are parallels with the influence of “Balai Pustaka, Chairil Anwar, W.S. Rendra and others” on the Indonesian language.20 “These men and women of letters played an important role in shaping Bahasa Indonesia and exactly the same thing is happening in Timor-Leste today, and they have a strong role in the evolution of Tetum.”

In an essay written in 2009, Barreto Soares called for remembrance of Timorese literary history and its role in the nationalist struggle and the building of a Timorese nation. He sought a dialogue between past and future: “As a people and a nation anywhere in the world, for the sake of survival in all aspects of life, Timorese people should, along with their poets, constantly engage in acts of reflection: looking towards the past as big lessons to learn, living in today’s reality in an intensive manner, and hoping to embrace the future with a great joy.”21

This theme stays with him today. “In order to have a brighter future,” he says, “you have to take one step backward and two steps forward. Without linking yourself to the past, you will not get anywhere. So you have to play this three-dimensional role at all times, you are a man of the past, of the future, of the present…. A visionary is a man of three-dimensional time. It’s rolling constantly, it’s rolling simultaneously. So the poet feeds the soul of the nation. The poet is the soul-keeper of the nation. The poet’s role is to continuously feed. If a nation loses its soul, that is the suicide of that nation.”

Notes

On the colonial museum, see Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, second edition (London: Verso, 1991). On song and national identity in another Indonesian colonial context, see Julian Smythe, “The Living Symbol of Song in West Papua: A Soul Force to be Reckoned With,” Indonesia 95 (April 2013): 73-91, reprinted in David Webster, ed., Flowers in the Wall: Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2016), 233-259.

On Timorese history, see among other sources Chega! The final report of the Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (Jakarta: Gramedia, 2015); António Barbedo de Magalhães, Timor Leste : ocupaçãoIndonésia e genocídio (Porto : Universidade do Porto, 1992); Carmel Budiardjo and Liem Soei Liong, The War Against East Timor (London: Zed Books, 1984); James Dunn, East Timor: A Rough Passage to Independence (Australia: Longueville, 2004); Clinton Fernandes, The Independence of East Timor: Multidimensional Perspectives—Occupation, Resistance and International Political Activism (Eastbourne, East Sussex: Sussex Academic Press, 2011); Jill Jolliffe, East Timor: Nationalism and Colonialism (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1978); Jose Ramos-Horta, Funu: The Unfinished Saga of East Timor (Boston: Red Sea Press, 1987); Geoffrey Robinson, If You Leave Us Here, We Will Die: How Genocide Was Stopped in East Timor (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2010); and Awet Tewelde Weldemichael, Third World Colonialism and Strategies of Liberation: Eritrea and East Timor Compared (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Constancio Pinto and Matthew Jardine, East Timor’s Unfinished Struggle: Inside the Timorese Resistance (Boston: South End Press, 1997).

“Maubere” was a common name among the Mambai people of Timor-Leste, originally used under Portuguese colonialism to contemptuously describe hill peoples, then reclaimed as a nationalist badge of pride. See Ramos-Horta, Funu. The National Council of Maubere Resistance (CNRM) became the National Council of Timorese Resistance (CNRT) in 1998. See Sara Niner, Xanana: Leader of the Struggle for Independent Timor-Leste (Australian Scholarly Pub., 2009).

Abé Barreto Soares, “East Timor: Towards the Year 2000,” paper presented at Ontario conference on East Timer (1993).

Hannah Loney, “Speaking Out for Justice: Bella Galhos and the International Campaign for the Independence of East Timor,” in S. Berger and S. Scalmer (eds.), The Transnational Activist (London: Palgrave, 2018).

“Speech by H.E. President Taur Matan Ruak on the occasion of the 13th Anniversary of the Restoration of Independence,” Maliana, Timor-Leste, 20 May 2015.

Text of poem from East Timor Alert Network papers, McMaster University Archives, Hamilton, Ont., Canada.

Among other inspirations, he lists Canadian poets Leonard Cohen, Earl Birney, Louis Dudek, and Margaret Avison. “These four poets really had an influence on my writing. The American poets that inspired me are Walt Whitman, Stanley Kunitz, Langston Hughes, Maya Angelou, novelists Henry James, Herman Melville, Stephen Crane, American presidents Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy, and also Martin Luther King. That is from the north, but from the south there is Pablo Neruda of course, José Luis Borges from Argentina, Eduardo Galeano from Uruguay, also from Brazil Paulo Coelho, from Nicaragua Ernesto Cardenal, from Guatemala Otto Rene Castillo, and from Mexico Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes plus Rosario Castellano. These are the writers from North and South America who really inspired me in my literary career.”

See for instance Josh Trindade, “Lulik: The Core of Timorese Values,” Paper presented at: Communicating New Research on Timor-Leste 3rd Timor-Leste Study Association (TLSA) Conference on 30th June 2011.

Balai Pustaka was a popular library and literacy program; Anwar and Rendra were nationalist poets writing in Indonesian and influencing the development of the language.

ABS, “Nationalism of Timor-Leste seen from the eyes of its poets,” posted on the author’s blog “Dadolin–poetry from the land of ‘lafaek’ – crocodile,” 2 August 2010.