Introduction

The Routledge Handbook of Modern Japanese History,1 a concise introduction to Japanese history between the middle of the nineteenth century and the end of the twentieth, was published in late 2017. In preparing the work, the editors were fortunate to obtain the cooperation of 30 historians from Japan, Europe, Australia and the U.S., who provided succinct yet comprehensive overviews of their field of expertise.

|

|

The Handbook is divided into four sections, “Nation, Empire and Borders,” “Ideologies and the Political System,” “Economy and Society,” and “Historical Legacies and Memory.” The first three address the history of the political system, international relations, society, economy, environment, race and gender. The final section consists of three chapters that address the important and, given the current situation in East Asia, highly relevant issues of historical memory, war responsibility, historical revisionism and Japan’s not always successful efforts to come to terms with its own past.

This article is by Hatano Sumio, professor emeritus at the University of Tsukuba. Professor Hatano is Director-General of the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR); he chaired the Editorial Committee of the Nihon gaikō bunsho (Diplomatic Documents of Japan) series published by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and between 2008 and 2011 he was a member of the Japan-China Joint History Research Committee. Hatano is the author of numerous books including Taiheiyō sensō to Ajia gaikō (The Pacific War and Asian Diplomacy, 1996, winner of the Yoshida Shigeru Prize) and Kokka to rekishi (The State and History, 2011) and co-edited the four-volume Jijūchō bukan Nara Takeji nikki, kaikoroku (The Diaries and Reminiscences of Aide-de-Camp Nara Takeji, 2000).

In the chapter, Hatano addresses the legacy of the Asia-Pacific War and its effects on Japan’s relations with its neighboring countries. Although many themes the article discusses such as war reparations, territorial disputes, and comfort women have been discussed in The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus before, Hatano’s article is of great value not only because it provides a wealth of historical detail but also because it reflects the views of Japanese mainstream historians. For it must not be forgotten that, in spite of the efforts of historical revisionists, a consensus prevails among academic historians both on what happened in the past and on the ways in which Japan has addressed – or failed to address – its past. We should add that Hatano’s article is an updated distillation of the themes he discusses in great detail in Kokka to rekishi, a book that draws heavily on his personal experience in exploring these controversial and sensitive issues relating to modern Japan’s historical legacy.

It is also a matter of record that Hatano, though serving on a number of governmental bodies, joined 73 other scholars, in signing a petition in protest against the Abe Shinzō government’s support for revisionism and its efforts to politicize history and historical education. The main purpose of this petition was to counter the official statements questioning the assessment that the Asia-Pacific War was a war of aggression made repeatedly by Prime Minister Abe in blatant disregard of the views of the overwhelming majority of Japanese historians. Although in the end Abe felt constrained to phrase his Statement on the Occasion of the 70th Anniversary of the End of the War inoffensively, he refused to make a clean breast and continued to obfuscate, which earned him the criticism of the signatories of the above-mentioned statement.

All sources included in this article are listed in the Handbook’s bibliography which is freely accessible online as is the Introduction which will provide the reader with more detailed information about the Handbook.3

History and the state in postwar Japan (Hatano Sumio)

The history problem (rekishi mondai) has been plaguing Japanese foreign relations in the postwar period. Japan is often criticized as being unable to come to terms with its past, and doubts are cast on the historical awareness of the Japanese government and the Japanese people. Neighbouring countries have pointed out that the coverage of war-related issues in Japanese history textbooks is inadequate. In the background of such criticisms there are strong fears, based on the experience of Japanese colonialism and aggression toward Asia prior to the end of the Second World War, that Japan might once again become a ‘military superpower’. In addition, it is frequently pointed out that reparations, indemnities, expressions of remorse and apologies concerning damages caused by Japanese colonialism and aggression to Asian countries and peoples of Asia have been insufficient and that many issues remain unresolved. Many in Japan share this view. Of course, these questions could have been settled all at once by means of a peace treaty between the victorious and defeated powers, as had been done in the Versailles Peace Treaty after the end of the First World War. However, that did not happen in East Asia after 1945.

|

Figure 1: Japanese Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru signs the San Francisco Peace Treaty (1951). |

It is true that Japan signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951 (in effect from 1952) with 48 countries including the United States, Britain, France and Australia. But not all allied nations that had been at war with Japan signed this treaty.4 As expressed in the phrase ‘a separate peace’, the United States was keen to go ahead with granting Japan independence, and in the climate of the intensifying Cold War gave priority to peace treaties with countries in the Western bloc, while the Soviet Union, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and other socialist countries stayed away from the peace conference. As a result, Japan had to negotiate separate agreements with the countries absent from San Francisco to normalize relations. Such separate agreements included the 1952 Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (the Treaty of Taipei between Japan and the Republic of China, i.e. Taiwan), the 1956 Soviet-Japan Joint Declaration (between the Soviet Union and Japan), the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of South Korea, and the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué (between Japan and the PRC). In addition, the Philippines, Indonesia, Burma (Myanmar), and Vietnam had refused to sign or ratify the San Francisco Peace Treaty on the grounds that reparations were insufficient. With those four Southeast Asian countries, the Japanese government later signed bilateral ‘reconciliation’ agreements that conformed to the model of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. As a result, Japan at present takes the position that problems caused by the war and colonial rule were settled through these ‘public acts of reconciliation’ (i.e., the San Francisco Treaty System) and that it thus made a contribution to the stability of the international order in the Asia-Pacific area. However, even now there are quite a number of people in the neighbouring countries, in the former Allied Powers, and even in Japan who think that Japan has not properly come to terms with its past and that reparations to the victims, apologies and remorse about the war have been inadequate. Especially with regard to Korea and China, one must conclude that the attempt to establish sufficient trust has failed as a result of problems with history, and that this failure constitutes an obstacle to an improvement in Japan’s relations with these two countries. What is the root of this problem? How has Japan reacted to it? What is necessary to achieve ‘historical reconciliation’? I will try to address these questions by focusing on how the position of the Japanese government has evolved over time (see Hatano 2011 for details).

The ‘History Problem’ prior to 1970

War reparations and war responsibility

The 1919 Versailles Peace Treaty made a provision concerning war responsibility and imposed reparations on Germany. However, the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty in principle waived any claims to reparations. In the peace treaty, also known as a ‘generous’ peace, the chief allied powers, that is, the United States, Britain and France, waived their right to claim reparations from Japan. However, countries that objected to this waiver, such as the Philippines, obtained the right to conduct separate negotiations with Japan. This led later to the conclusion of reparation agreements and peace treaties between Japan and a number of Southeast Asian countries. Japan paid reparations to four Southeast Asian countries, namely, the Philippines, Indonesia, Burma (Myanmar), and Vietnam. The payment of these reparations, totalling one trillion yen, was completed by the end of the 1960s. However, this huge amount was not paid to compensate for direct damage to the countries. The settlements gave priority to ‘economic cooperation’ (economic aid) that brought benefit to both parties. As such they contributed both to the revival of Japan and to the economic development of Southeast Asia. But it is also a fact that they weakened the original goal of reparations that was to bring a sense of responsibility and remorse to Japan. This formula of ‘economic cooperation’ was also applied in 1965 in the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of South Korea and an agreement regarding mutual claims signed at the same time. Immediately after these treaties were concluded, doubts were expressed in the Japanese press as to whether the original goal of reparations would be grasped properly if reparations and economic cooperation were not treated separately, but in no time such doubts were silenced by a chorus of approval for the settlements.

From the point of view of war responsibility, it must be said that, compared with the Versailles Treaty, the 1951 peace treaty with Japan was incomplete. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE, aka the Tokyo Trials) which had tried 28 Japanese war leaders came to an end in December 1948, with seven of the accused being sentenced to death. In addition, proceedings in other international military tribunals dealing with so-called class B and C war crime trials had more or less ended before the treaty was concluded. The question of what significance to give to these international military tribunals in the text of the peace treaty arose in the process of drafting it. Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty stipulated that Japan ‘accepts the judgments of the international military tribunals’, but made no reference to the question of war responsibility. As a result, this has given rise to an interpretation that the Japanese government ‘accepts the judgments’ of the Tokyo Tribunal that had sentenced General Tōjō Hideki (1884–1948), the wartime prime minister, to death, but that it does not necessarily accept the reasons for the sentence as given by the tribunal. Moreover, in Japan this has led to claims that the War Crimes Tribunal represented ‘victors’ justice’ by the Allies and thereby to doubts being cast on the legitimacy of the tribunal.

The cause of the ambiguity of the peace treaty concerning war reparations and war responsibility, as compared with the Versailles Treaty, lies in the gradual relaxation of the early postwar policy of punitive measures toward Japan by the United States, a country which played the leading role in drafting the text of the peace treaty. This was especially because, as the Cold War in East Asia intensified with the formation of the PRC in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, America decided to position Japan as a ‘bulwark against communism’. Instead of rendering Japan powerless, the United States now placed emphasis on Japan’s economic revival and economic autonomy, while the questions of the pursuit of war responsibility and war reparations were put on the backburner.

|

Figure 2: The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tokyo Trials), 1946-48. |

Be that as it may, until the 1970s the Japanese people generally regarded themselves as ‘victims’ of the war. References to the suffering inflicted by Japan upon the neighbouring Asian countries were few and far between. The discussion of war responsibility in the Japanese media focused upon the nature of wartime Japan’s political-economic structure, such as the role of the emperor or the military, but there was little awareness that Japan had been a perpetrator.

Japan’s role as a perpetrator began to be properly addressed in the 1980s, when its conduct in the war was examined and the victim consciousness questioned.

The normalization of Japan-Korea relations and the question of ‘coming to terms with the past’

Korea was a Japanese colony until 1945. After obtaining independence, Korea demanded to participate in the San Francisco Peace Treaty conference as a ‘victor’. Had it become a signatory of the Treaty, it would have been able to exercise its right to claim indemnities from Japan just like any Allied Power. In the end, however, Korea was not invited to the Peace Conference on the grounds that it had not been at war with Japan, although at the same time the United States promised to treat Korea in the same way as other Allied Powers. On the assumption that Japanese-owned property on the Korean peninsula would be ceded to Korea, the United States put it under the administration of the U.S. military government but left the final disposition of this property to negotiations between Japan and Korea.

In this way, the disposition of Japanese property in Korea at the Japan-Korea talks, which started at the end of 1951, became a contentious issue. The Japanese side argued that, having lost all public property in Korea, the national sentiment would not allow further concessions, and it continued to insist that Japan had the right to make claims on privately-owned Japanese property in Korea. On the other hand, the Korean side, on the grounds of the enormity of the damages caused by 36 years of Japanese rule, refused to be content only with Japanese property abandoned in Korea and insisted that it had the right to make claims with regard to the return of cultural assets, and the repayment of obligations to Koreans including post office savings, insurance, pensions, etc.

The Japan-Korea talks brought to the fore a difference in historical awareness between the two countries on whether Japan’s colonial rule was legal. Korea insisted that the 1910 Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty was ‘null and void’. On the other hand, Japan insisted that the Annexation Treaty was legally binding, and from this premise argued that economic activity by Japanese in Korea was legitimate. In October 1953, in what is known as the Kubota statement, the Japanese delegate Kubota Kan’ichirō (1902–77) hinted at the possibility of mutual liabilities cancelling themselves out when he declared that Japan had ‘made mountains green, built railroads, constructed harbours, created irrigated rice fields, … and provided large subsidies to develop the Korean economy’.

In December 1957, the Japanese government retracted the Kubota statement and abandoned its claims to Japanese property in Korea. In the end, in the 1960s, things moved toward a settlement through ‘economic cooperation’ whereby Japan offered financial aid in exchange for Korea’s renunciation of its claims. In this way, the perspective of indemnities for colonial rule and war receded to a large degree from the subject of discussions at the Japan-Korea talks. Keen to promote the economic development of both countries, the United States supported a solution based on this formula, because it gave priority to Korea’s economic development and ‘the unity of the non-communist bloc’ over settling the claims question. In these circumstances, in June 1965 Japan and Korea signed the Treaty on Basic Relations5 and the Agreement concerning the Settlement of Problems in regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation.6 The treaty established diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea, and settled claims between the two countries. Japan agreed to provide Korea with economic cooperation funds consisting of a 300 million dollar (non-returnable) grant in economic aid and 200 million dollars in loans. Both countries confirmed that the issue of claims ‘have been settled completely and finally’.

The South Korean government used the funds, among other things, toward the construction of the Pohang Iron and Steel Plant (POSCO) and the multi-purpose Soyanggang Dam. It should be added that under the terms of this agreement, the Korean government was also supposed to use these funds to compensate individual victims of colonialism and war.

As a result of the Japan-Korea agreements, the question of Japan’s coming to terms with the past was neglected. In reference to the legacy of Japanese colonial rule, it should be pointed out that Korea managed to take over some 80 per cent of Japanese-owned property on the Korean peninsula immediately after the liberation, and it can be said that this takeover formed the basis of Korea’s economic development. However, it proved difficult to acknowledge this, given the Korean view of its colonial past.

As regards the Republic of China (Taiwan), which like Korea had also been a Japanese colony, the issue of reparations was raised during the 1952 Japan-China Peace Treaty negotiations with the Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1975) government. The negotiations ran into trouble when the Chiang government claimed reparations and the Japanese countered that these claims were cancelled out by the Japanese property abandoned in China. In 1952, Japan and the Republic of China signed a peace treaty in which they renounced any claims to reparations7. Subsequently, the Japanese government adhered to the position that no reparations problem existed between Japan and China. However, this one-sided understanding was called into question during the 1972 negotiations to normalize diplomatic relations between Japan and the PRC.

The normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and the PRC and the reparations question

Negotiations to normalize diplomatic relations between Japan and the PRC were tricky as they had the potential to undermine the San Francisco Treaty system. To begin with, the People’s Republic of China, whose territories had suffered the heaviest damages during the war, had objected to the very idea of a peace treaty led by the United States. As we have noted above, under the terms of the 1952 Japan-China Peace Treaty, the government of the Republic of China had renounced claims to reparations from Japan. The Japanese government interpreted this treaty as applying also to claims from mainland China. However, the PRC refused to recognize this and insisted that it was entitled to claim reparations separately from the government of the Republic of China. In its ‘Three Principles for the Normalization of Relations (with Japan)’, the PRC made it clear that the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty was illegal and should be renounced. However, the Chinese insistence on reparations that ignored the peace treaty between Japan and the Republic of China threatened to prevent the restoration of relations between the PRC and Japan for many years to come. It also had the potential to harm U.S.-China relations and even threatened to undermine China’s strategy toward the Soviet Union. This is why the government of the PRC made it clear that it would renounce claims for reparations even before the start of the negotiations to restore diplomatic relations. At the end of September 1972, however, Premier Zhou Enlai (1898–1976) reacted strongly to the legalistic position of the Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs by declaring that ‘we will not accept the view that the issue has been settled by Chiang Kai-shek’s renunciation [of claims for reparations]’. The Chinese policy that renounced claims for reparations rested on the premise that Japan should accept responsibility and show remorse for ‘the war of aggression’.

Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei (1918–93) and Foreign Minister Ōhira Masayoshi (1910–80), who had to contend with opposition within the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), agonized over how to respond. The joint communiqué eventually signed contained a strong statement that ‘the Japanese side is keenly conscious of responsibility for the serious damage that Japan caused in the past to the Chinese people through war, and deeply reproaches itself’.8 This statement was inserted on Foreign Minister Ōhira’s insistence. Also, as regards the claims for reparations, the Chinese side announced that the PRC renounced claims, but, instead of using the expression ‘the right to claim’, it used the word ‘claim’. That is probably because, from the Japanese perspective, China had already renounced its ‘right to claim reparations’ in the Japan-China Peace Treaty of 1952. Clearly, this high-level political compromise was reached thanks to the strong political leadership of the leading figures in both governments.

Fifteen years before the start of the negotiations to restore relations between Japan and China, a Japanese cabinet minister had observed that ‘should China demand reparations, Japan’s economy would not be able to meet them’, so it would seem that Japan was saved by the Chinese leaders’ ‘magnanimous heart’. That indeed may have been the case, but the fact that it was the Chinese people who had overwhelmingly suffered during ‘the war of aggression’ did not go away. As seen from China, visits to Yasukuni Shrine (on this shrine, see chapter 31 in this volume) by Japanese prime ministers amount to glorifying those responsible for the Chinese suffering during the war. Such steps must appear as ‘mistaken actions that willfully hurt the feelings and dignity of the people of a victim nation’.

The internationalization of the history problem in the 1980s

The history textbook controversy

The 1980s marked the beginning of controversies over history textbooks and Yasukuni Shrine, leading to international scrutiny of Japan’s historical consciousness and war responsibility.

On 26 June 1982, the leading Japanese newspapers published the results of the Ministry of Education’s screening of high school history textbooks. All the newspapers reported that as a result of the screening, which is a part of the process of textbook approval, the word ‘aggression’ (shinryaku) was replaced by ‘advance’ (shinshutsu) in a section on ‘the Japanese Army’s aggression in China’. These press reports were mistaken in the sense that they claimed that the changes had been ordered by the Ministry of Education. That was wrong, because under the Japanese textbook approval system, all that the Ministry can do is present the authors of a textbook with an ‘improvement guidance’, but it cannot order revisions to be made. It is nevertheless true that there were some textbooks, which, in reaction to the ‘improvement guidance’, replaced ‘aggression’ with ‘advance’. In any event, the Chinese government condemned the Ministry of Education by stating that ‘Japanese militarism falsified the history of Japanese aggression in China’ and demanded that the falsification be rectified. The Korean government also criticized accounts of Japan’s colonial rule in textbooks, but China took a much tougher stance than Korea.

The fact that the Japanese government made no revisions in reaction to the Chinese criticisms caused an even stronger backlash. In the end, Miyazawa Kiichi (1919–2007), the chief cabinet secretary, published a statement saying that ‘the spirit in the Japan-Republic of Korea Joint Communique and the Japan-China Joint Communiqué naturally should also be respected in Japan’s school education and textbook authorization’ and that ‘from the perspective of building friendship and goodwill with neighbouring countries, Japan will pay due attention to these criticisms and make corrections at the Government’s responsibility’.9 In reaction to this statement, in November 1982 the Ministry of Education created a new authorization criterion for screening history textbooks known as the ‘Neighbouring Countries Clause’ (kinrin shokoku jōkō). This stipulated that ‘from the position of international understanding and international harmony, due consideration must be given when dealing with events in modern and contemporary history that affect Japan and neighbouring Asian countries’.10 Within the LDP there were complaints that this would hamper the preparation of independent textbooks, but in effect priority was given to international considerations. This ‘Neighbouring Countries Clause’ represented the first time that the Japanese government took a clear ‘historical reconciliation policy’.

Two years after the textbook controversy, during a visit by the President of the Republic of Korea Chun Doo-hwan to Japan in September 1984, the Shōwa Emperor (1901–89) said he found it ‘regrettable indeed that at one time in this century there was an unfortunate past between our nations that I believe must not be repeated’.11 The Korean side interpreted this statement as a ‘diplomatic apology for the past history’. From the point of view of overcoming ‘the past’ shared by Japan and Korea, it was thought that Japan-Korean relations entered a new stage, but just then the textbook controversy flared up once again.

In May 1986, just before the ministry released the results of the textbook examination for that year, a scoop in Asahi Shinbun revealed that the New Edition Japanese History textbook compiled by ‘The People’s Conference to Protect Japan’ (Nihon o mamoru kokumin kaigi) had ‘a reactionary tone’. The ‘People’s Conference’ was a political body whose declared goals included the drafting of an ‘authentically’ Japanese constitution (it considers the current Constitution as imposed by the United States), but it also was involved in the compilation of a history textbook in reaction to what it considered the weak-kneed response of the Japanese government to the 1982 textbook controversy. There was no doubt that New Edition Japanese History tended to justify Japan’s overseas aggression by claiming, among other things, that Japan embarked on the Greater East Asian War to ‘liberate East Asia’. It was moreover full of passages that emphasized Japan’s suffering. Both China and Korea reacted with fury. China in particular was furious that the textbook obscured the character of the war as a ‘war of aggression’. The Japanese Ministry of Education responded to this by issuing a ‘guidance’ to the publisher to revise the relevant passage. But when this second textbook controversy seemed to have died down, there was an outcry over an article by Education Minister Fujio Masayuki (1917–2006) in the October 1986 edition of the monthly Bungei Shunjū, in which he asserted that the Korean side bore its share of responsibility for the annexation of Korea by Japan. He also criticized Prime Minister Nakasone (b. 1918) as weak-kneed for his decision to discontinue official visits to Yasukuni. Nakasone immediately fired Fujio, in what was the first dismissal of a Japanese cabinet minister in thirty years.

The question of visits to Yasukuni Shrine

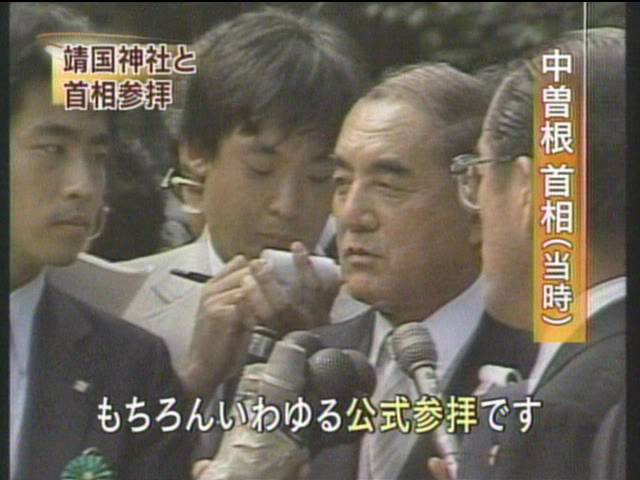

On 15 August 1985, Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro made an official visit to Yasukuni Shrine (for the background of this shrine, see chapter 31 in this volume). That was the first official visit to the shrine by a serving prime minister since the end of the war. Until then, if there had been any problems surrounding the shrine at all, they were of a purely domestic nature, namely, over whether visits to the shrine by cabinet ministers did or did not violate the Constitution, which stipulates the separation of politics and religion. The visit by Prime Minister Nakasone was based on the government’s (specifically, the cabinet legal bureau’s) opinion that a visit did not violate the Constitution as long as the form of the visit had no religious character. However, the government received an unexpected reaction from China. At the end of August, Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily) took up the subject of the enshrinement of class A war criminals12 at Yasukuni and raised the issue of the prime minister’s visit to the shrine by describing it as ‘obscuring the character of the war and the question of war responsibility’. The former prime minister Tōjō Hideki and other executed class A war criminals had been enshrined at Yasukuni in 1978,13 and this was what the Chinese side was reacting to.

|

Figure 3: Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro visits the Yasukuni Shrine (1985). |

At the same time, Renmin Ribao insisted that ‘the Chinese government has steadfastly and consistently adhered to a policy that distinguishes between a small circle of militarists and the wide masses of the Japanese people’. This was the so-called ‘bisected responsibility argument’. When in the process of normalizing relations between Japan and the People’s Republic, China renounced its claim to reparations, the same argument had been used to persuade the Chinese people to accept this renunciation. By the logic of the bisected responsibility argument, the Japanese people including class B and class C war criminals were victims of Japanese militarism, and a distinction should be made between them and the class A war criminals who bore the brunt of responsibility for the Japanese aggression from the Manchurian Incident on. As the Chinese side saw it, official visits by cabinet ministers to Yasukuni Shrine where the class A war criminals were enshrined meant the reaffirmation of aggression and evasion of responsibility for the war of aggression.

In this way, the textbook controversy and the Yasukuni problem were suddenly ‘internationalized’ in the 1980s. The significance of these two problems is that the historical consciousness and the war responsibility of the Japanese government were once again called into question. The evaluation of the Tokyo Trials also became a problem in the National Diet. For example, Chief Cabinet Secretary Gotōda Masaharu (1914–2005) in a parliamentary reply stated that the government could not repudiate the Tokyo Trials, but that did not mean that it accepted the legitimacy of the verdict of the Tokyo Trials, whose underlying view of the war was that of a ‘war of aggression’. That was the government’s position on the Tokyo Trials in the 1980s, and this position remains unchanged today.

Over the period of ten years, 1987–97, after the resignation of the Nakasone cabinet, no prime minister made either an official or private visit to Yasukuni Shrine. That was because LDP bosses and cabinet ministers were persuaded to refrain from official and unofficial visits to the shrine that might cause offence. The grounds for this were that ‘others’ feelings cannot be ignored’, based on Chief Cabinet Secretary Gotōda’s statement that Japan accepted the verdict of the Tokyo trials by signing the Peace Treaty.

While the government discontinued visits to Yasukuni by the prime minister and other cabinet members, it also began to search for a way out of the difficulty surrounding the class A war criminals’ enshrinement at Yasukuni through constructing a new memorial facility and contemplating separate enshrinement (bunshi) for them. Separate enshrinement means transferring the spirits of the seven executed class A war criminals to a facility other than Yasukuni Shrine. An expansion of the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery (established in 1959) was also considered as a plan to build a new government-funded memorial facility. This cemetery is the only central government-funded war memorial facility in Japan and it is a purely secular site14. It is basically a memorial to unknown soldiers, that is, those whose names and places of death could not be identified. At present, the remains of some 350,000 ‘unknown soldiers’ and a number of civilians are laid to rest there.

|

Figure 4: Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery. |

However, the proposals for separate enshrinement and construction of a new facility were rejected by Yasukuni Shrine and have not been put into effect. For many of the bereaved families Yasukuni Shrine remains the only memorial facility where the war dead are enshrined and for them the alternative of a separate enshrinement or the construction of a new facility is unacceptable. Yasukuni Shrine is a religious corporation, and under the Japanese Constitution with its provision for the separation of politics and religion the government has no choice but to respect the view of the shrine. This question has remained unresolved to the present day.

The 1990s: The question of postwar reparations and the Asian Women’s Fund

Postwar reparations and the question of comfort women

As we have seen above, Japan achieved a settlement regarding reparations for war damages with many Asian countries in the 1950s and 1960s. However, in the 1990s Korean and Chinese individuals began to raise the issue of ‘postwar reparations’. Postwar reparations included payments to individual war victims in Asian countries, such as slave labour, the so-called comfort women, the victims of the bombing of Chongqing (Chungking, the provisional capital of the Republic of China from 1937 to 1945) and others.

On this postwar reparations question, the Japanese government has taken the position that compensation for damages caused to Asian countries, whether to states or to individuals, was settled under the San Francisco Peace Treaty, and also under the Sino-Japanese Joint Declaration and the 1965 Japan-Korean Basic Treaty (and the claims agreement signed at the same time). Therefore, it holds that it is not legally obliged to offer compensation to individuals, but does so in certain cases on the grounds of moral responsibility and human rights. This view has resulted in ambiguities in some cases.

On the judicial level, the number of postwar cases in which Chinese and Korean victims were seeking compensation and apology from the Japanese government in Japanese courts increased sharply in the 1990s, but none of the plaintiffs have been successful to date. Though in many court cases judgments recognized the fact of suffering, they were nevertheless clear that international law specifies that an individual cannot be a party in an international lawsuit. This legalistic position has formed an insurmountable obstacle to providing compensation to individual war victims.

At the same time, questions of postwar reparations were debated in the Japanese Diet. These included the issues of slave labour and comfort women. In particular, the question of comfort women assumed a symbolic meaning in this context. These are women who during the war were placed in Japanese military brothels, where they were forced to engage in sexual acts with soldiers. Especially, after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, as the Japanese army occupied more and more Chinese territory and a large number of troops were sent to China, Japanese military brothels proliferated rapidly. This proliferation was partly the result of a concern that the large number of rapes of Chinese women by Japanese soldiers would exacerbate anti-Japanese sentiments among the Chinese. Another factor was the need to prevent the spread of venereal diseases. In 1941, when the Pacific War broke out and the Japanese occupied Southeast Asia and islands in the Pacific, military brothels were gradually set up in these areas.

Comfort women sent to these areas included Japanese women recruited in Japan by procurers for the army, and women from the Japanese colonies of Korea and Taiwan. The recruitment methods used by the procurers were diverse, as were the circumstances in which the women became comfort women. Many applied in response to advertisements; others applied in order to pay off the parents’ debts or due to other family circumstances; and a large number were deceived by the procurers.

For many years after the war, the existence of comfort women had been confined to the memories of the affected women and soldiers: it was rarely discussed in public until the 1980s. But on the crest of the democratization movement in Korea in the latter half of the 1980s, the question of comfort women began to attract attention due to ‘accusations’ made by women’s groups, whose activities focused on the question of sexual violence toward women. In late 1991, former comfort women filed a lawsuit for the first time against the Japanese government in the Tokyo District Court, seeking compensation from the Japanese state. The Miyazawa Kiichi cabinet, which had been formed just a month before, launched a full-scale investigation into the comfort women issue and the question of compensation. Previously, whenever asked what his stance on comfort women was, Prime Minister Miyazawa had merely repeated that all legal obligations resulting from Japan’s wartime actions had been settled under the San Francisco Peace Treaty and other agreements. But when, as prime minister, he was confronted with the question of how a ‘great economic power’ like Japan was to fulfill its international obligations, he concluded that Japan should recognize the suffering it had caused to the peoples of Asia and that some form of ‘compensation’ was necessary.

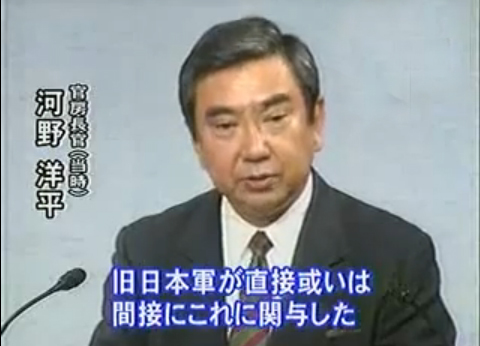

As a result of the investigation into the comfort women question launched by the Miyazawa cabinet, the government released 117 documents relating to the Japanese Imperial Army that were held in the archives of government institutions. The report concluded that there was no evidence that either the military or government officials were directly involved either in the recruitment of, or in the setting up of brothels for, comfort women. However, in August 1993 just as the final report of the investigation was published, Chief Cabinet Secretary Kōno Yōhei (b. 1937) issued an unofficial statement, in which he declared as follows:

Comfort stations were operated in response to the request of the military authorities of the day. The then Japanese military was, directly or indirectly, involved in the establishment and management of the comfort stations and the transfer of comfort women. The recruitment of the comfort women was conducted mainly by private recruiters who acted in response to the request of the military. The Government study has revealed that in many cases they were recruited against their own will, through coaxing, coercion, etc., and that, at times, administrative/military personnel directly took part in the recruitments. They [comfort women] lived in misery at comfort stations under a coercive atmosphere. … Undeniably, this was an act, with the involvement of the military authorities of the day, that severely injured the honour and dignity of many women.15

|

Figure 5: Kōno Yōhei. |

The Kōno statement was the result of a comprehensive investigation: witness testimony collections were published by Korean women’s groups; there were testimonies by brothel managers; and there was an ongoing search for documents in the National Archives in the United States. In addition, in the final stages of the investigation an oral survey of comfort women was conducted.

With regard to ‘coercion’ at the recruitment stage, which was the focus of this investigation, the Kōno statement accepted it as a fact, as is evident from the quotation above. The phrase ‘involvement of the military authorities of the day’ was based on facts like the Semarang Camp Women’s Incident in Indonesia, in which Dutch women were forcibly taken to comfort facilities. The Kōno statement applied to comfort women throughout the entire Asian region and was not limited to the Korean peninsula. However, as a concession to the Korean side, for which the comfort women issue was particularly delicate and which emphasized the issue of ‘coercion’, the following phrase was added: ‘The Korean Peninsula was under Japanese rule in those days, and their [comfort women’s] recruitment, transfer, control, etc., were conducted generally against their will, through coaxing, coercion, etc’.

The Kōno statement, which skillfully interwove both Japanese and Korean claims regarding the ‘coercion’ involved in the recruiting of women, for a time was accepted by the Korean government, which praised it as a ‘complete recognition of the coercion involved in the recruitment, transportation, and management of military comfort women’. In the Kōno statement, the Japanese government promised to investigate the means of realizing in concrete terms ‘the best way of expressing this sentiment’.

The Asian Women’s Fund

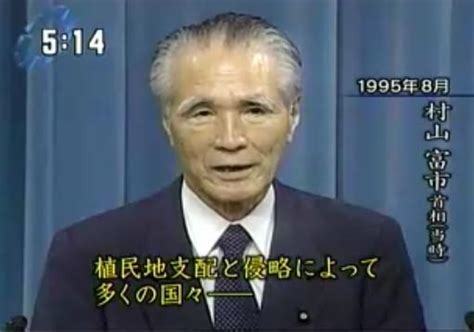

Subsequent cabinets also shared the Miyazawa cabinet’s awareness of the comfort women issue, but did nothing about it on the grounds that the option of direct compensation to individuals by the Japanese state was ruled out by the courts. It was only the cabinet under Murayama Tomiichi (b. 1924) that, in 1994–95, addressed the lack of a concrete ‘historical reconciliation policy’ with respect to the comfort woman question in the broader context of finding a method of ‘compensation’.

|

Figure 6: Murayama Tomiichi. |

At the end of August 1994, Prime Minister Murayama announced a ‘Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative’ to achieve ‘mutual understanding and trust’ between the Japanese and the peoples of Asia. This policy consisted of two planks. One of these concerned projects that supported historical research ‘to take a direct look at history’; the other concerned intellectual exchanges and youth exchanges. The centrepiece of the former was the founding of the Japan Centre for Asian Historical Records (JACAR), whose purpose was to make historical documents available online.17 There were altogether some 60 projects, with a total of 90 billion yen expenditure. Prime Minister Murayama also promised to find a ‘way of broad participation by the Japanese people’ to solve the comfort women issue and share with them the ‘feelings of apology and remorse’. The policy of responding to the comfort women question formed the second part of the ‘Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative’.

In reaction to these statements and initiatives, a subcommittee was formed by the three parties in power, the Japan Socialist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party and the New Party Sakigake. They found it difficult to reconcile the position of the Socialist Party with the position of the Liberal Democratic Party. The Socialist Party started from the premise that the state should compensate the victims and insisted on a form of compensation that would combine government funds with money raised by the Japanese people, while the Liberal Democratic Party and the cabinet were against it. In the end, the report of the subcommittee rejected the idea of compensating individuals by the state and proposed a ‘People’s Fund’ that would be raised from contributions by the Japanese people in order to fulfill Japan’s moral responsibility. According to this proposal, the government would cooperate with this fund in various ways, including contributions of capital to the fullest extent possible.

In July 1995, in response to the subcommittee report, the government launched the Asian Women’s Fund (the Asian Peace and Friendship Fund for Women, usually known as AWF) in the form of an incorporated foundation.18 A full-page ‘appeal’ to the Japanese people asking for donations was published in five national newspapers on 15 August 1995, the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Asia-Pacific War. The operations of the AWF consisted of four planks. First, it would pay each former comfort woman two million yen as compensation. Second, each former comfort woman would be given a letter signed personally by the Japanese prime minister, which would contain a clear apology. The letter recognized that the ‘issue of comfort women, with an involvement of the Japanese military authorities at that time, was a grave affront to the honour and dignity of large numbers of women’. The prime minister19 also extended ‘anew my most sincere apologies and remorse to all the women who underwent immeasurable and painful experiences and suffered incurable physical and psychological wounds as comfort women’.20 The third plank consisted of operations supporting medical treatment and welfare financed with government funds, and the fourth plank was to compile materials relating to comfort women in order to provide a ‘history lesson’.

Implementation of the first two planks, which constituted the most important aspects of the fund, did not proceed smoothly. Although the South Korean government had initially welcomed the launch of the fund, it soon gave it a negative evaluation and turned down the offer of money to former comfort women. This was the result of a powerful opposition movement in Korea, backed by the mass media and women’s groups, which supported the former comfort women. Only seven former comfort women from Korea recognized the good faith of the fund and accepted ‘compensation money’, and it is said that they were subsequently subject to strong public criticism. Under the circumstances, the fund suspended its operations for a period of time, but resumed them in 1998. However, President Kim Dae-jung (1924–2009) severed contacts with the fund and adopted a policy of offering livelihood support to victims who pledged that they would not accept money from the AWF.

The fund did not encounter such problems elsewhere. The Indonesian government, taking the position that the war claims question had been settled by the Japan-Indonesia Peace Treaty, expressed its hope that assistance would be provided toward the construction of a facility for the elderly instead of individual ‘compensation’ payments. This was accepted by the AWF. Although in Taiwan and the Philippines, there was some resistance by groups insisting that the Japanese state ought to pay reparations directly, the payment of ‘compensation money’ through the AWF went relatively smoothly. The situation with the Netherlands, which had signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty, was complicated, but eventually a settlement was reached when medical welfare assistance was given to 79 former comfort women.

The fund, which ended its operations in March 2007, collected donations of 600 million yen, while the government contributed 480 million. As many as 285 victims (211 in the Philippines, 61 in Korea, and 13 in Taiwan) received letters from the prime minister and were given financial compensation. Copies of the letter were also delivered to the Prime Minister of the Netherlands and the President of Indonesia.21 Successive prime ministers who put their signature on the letter included Hashimoto Ryūtarō, Obuchi Keizō (1937–2000), Mori Yoshirō (b. 1937), and Koizumi Jun’ichirō (b. 1942). In this way, the fund operations were partly successful with positive evaluations received in the Philippines, Indonesia, and the Netherlands. In Korea and Taiwan, however, fewer than one-third of the total of those identified and registered as victims accepted compensation. In addition, one of the problems with the fund was that its operations did not extend to China, where a large number of victims are thought to exist.

The Murayama Statement and the Japan-Korea and Japan-China joint declarations

On 15 August 1995, Prime Minister Murayama issued the so-called Murayama Statement (‘Statement on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the War’s End’).22 The expressions of ‘profound remorse’ and ‘heartfelt apology’ to the peoples of Asia for the suffering caused by Japan’s ‘colonial rule and aggression’ constituted the fundamental part of this statement. Words of apology and remorse offered by prime ministers and members of the cabinet had not been unheard before, but they had been distinguished by their stopgap and ‘lightweight’ character. However, there was nothing stopgap about the Murayama Statement, which had been drafted in the main by the Prime Minister’s Office as an expression of will by the government, which should be adhered to even after a change of administration. It was moreover based upon a unanimous cabinet decision. The statement was not intended to overcome divisions in historical awareness that had arisen in Japan, but at least cabinet ministers no longer could assert that ‘it is debatable whether the war was a war of aggression’.

The Murayama Statement was possible not so much because it was made by a coalition cabinet led by a socialist prime minister, but because it was based on the awareness of successive cabinets since the early 1990s, which had been trying to sincerely address the outpouring of complaints from Asian victims, while adhering to the legal framework provided by the San Francisco Treaty and other agreements. At the same time, the effects of the Murayama Statement percolated to neighbouring countries. The spirit of the statement was reaffirmed in bilateral agreements, such as the Japan-South Korea Joint Declaration23 of October 1998 and the Japan-China Joint Declaration24 of November 1998.

The Japan-South Korea Joint Declaration (officially titled The Japan–South Korea Joint Declaration: A New Japan-Korea Partnership towards the Twenty-first Century), was signed during the October 1998 visit of South Korean President Kim Dae-jung to Japan. In the declaration, Prime Minister Obuchi repeated the exact words of the Murayama Statement to express his ‘profound remorse’ and ‘heartfelt apology’ for Japan’s past transgressions. In response, President Kim stated that he

accepted with sincerity this statement of Prime Minister Obuchi’s recognition of history and expressed his appreciation for it. He also expressed his view that the present calls upon both countries to overcome their unfortunate history and to build a future-oriented relationship based on reconciliation as well as good-neighbourly and friendly cooperation.25

In other words, progress was made in the process of reconciliation as the Japanese prime minister expressed his ‘heartfelt apology’ for war and colonial rule of Korea, and the South Korean side ‘accepted with sincerity’ this Japanese apology. It was done without great fanfare, but to judge by its content, it was an epoch-making declaration in the history of Japanese-South Korean relations.

The Japanese government took the position that the history question was settled. In his statement, President Kim declared that the South Korean government would no longer raise the history question on the government level, which suggested that historical reconciliation had been achieved. Moreover, the ban on Japanese popular culture in South Korea (pop music, anime and manga) was lifted and a new Japan-South Korea Fisheries Agreement was also concluded, further symbolizing Japanese-Korean rapprochement.

The joint declaration made in November 1998 by the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Jiang Zemin (b. 1926), who arrived in Japan a month after President Kim, and Prime Minister Obuchi, referred directly both to the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué and to the 1995 Murayama Statement and specified that

the Japanese side is keenly conscious of the responsibility for the serious distress and damage that Japan caused to the Chinese people through its aggression against China during a certain period in the past and expressed deep remorse for this.26

This was the first joint communiqué in history which referred to ‘responsibility for aggression’ with respect to China only. At the same time, Jiang Zemin, in a speech at the dinner at the Imperial Palace and in a lecture at Waseda University, strongly criticized the war of aggression waged by ‘Japanese militarism’ and even made references to concrete damages by stating that China ‘suffered the loss of 35 million casualties and economic damage in excess of 600 billion U.S. dollars’. In Japan, this criticism came as a bolt out of the blue, but Jiang Zemin had been putting much effort into ‘patriotic education’ that taught the younger generation of Chinese the experience of the war of resistance against the Japanese, so most probably the speech was a message aimed at the Chinese people.

The spirit of the Murayama Statement was also reflected in subsequent government statements such as the Japan–North Korea Pyongyang Declaration of September 2002, the speech by Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō at the Asia-Africa Summit Conference in Singapore in April 2005, and the statement by Prime Minister Kan Naoto (b. 1946) in August 2008.

The history problem in the twenty-first century

The merging of territorial disputes and the history problem

In spite of the successes in reconciliation described above, the history problem remains a divisive issue in East Asia in the twenty-first century. In April 2001 China and South Korea reacted strongly to the approval by the Ministry of Education of the junior high school history textbook compiled by the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashii rekishi kyōkasho o tsukuru kai). The Society had been founded in reaction to the statements in textbooks concerning the comfort women question that were based on the Murayama Statement. China demanded revisions to over 30 passages. However, unlike previous Japanese cabinets, neither the Mori cabinet nor the succeeding Koizumi cabinet made any changes in response to China’s demands. In July 2001, matters came to such a pass that the Korean government re-imposed the ban on Japanese culture, while many exchange events arranged by local authorities and by private bodies were cancelled. However, the Chinese and Korean fury abated soon. That was probably because the neighbouring countries had come to understand the textbook screening system, and also because the textbooks in question had extremely low rates of adoption by junior high and high schools.27

Prime Minister Koizumi visited China in the first days of October 2001, and having toured the Marco Polo Bridge and other sites related to the Sino-Japanese War,28 apologized again for Japan’s aggression toward China. During his visit to Korea in mid-October, the prime minister visited a prison site where independence activists had been held in colonial times, and in his meetings with Korean politicians, he made clear his intention to ‘apologize and show remorse’ for Japan’s past. He also agreed to the launch of joint research into history textbooks.

At the same time, Prime Minister Koizumi resumed the practice of visits to Yasukuni Shrine. With the first visit taking place on 13 August 2001 and the last one on 15 August 2005, he made altogether six visits to the shrine during his time in office. After each visit, both China and South Korea reacted strongly. Both countries rejected Japanese proposals for summit meetings, which were not held while Koizumi remained in office. For his part, the prime minister kept insisting that his official visits were intended to commemorate the war dead and to renew his commitment to world peace and that they were not meant to legitimize past actions. A statement he made after his first visit to the shrine expressed the same historical awareness as the Murayama Statement.

Even at a time when mutual visits of heads of state of Japan and China ceased, however, the Japan-China strategic dialogue continued. After Koizumi resigned in 2005, bilateral relations were improved as the Abe Shinzō cabinet initiated a Strategy of Mutual Relationship. Abe underlined the importance of relations with China by deciding to visit the country on his first official visit abroad as prime minister. As a result of this decision, summit meetings were resumed for the first time in five years.

Thereafter, the history issue ceased to be a major point of contention in diplomatic relations, and the Japanese side assumed that reconciliation had been achieved. But soon circumstances arose that led to the disappointment of such assumptions. The main cause of this was the emergence of territorial disputes.

South Korean-Japanese relations deteriorated rapidly as a result of the Shimane prefectural assembly introducing a ‘Takeshima Day’ in February 2005. Both countries claim sovereignty over a small group of islands known as Takeshima (Dokdo, aka Liancourt Rocks), which were declared Japanese territory in 1905, when Korea was turned into a Japanese protectorate. Following the normalization of relations between Japan and South Korea in 1965, both sides, to prevent a diplomatic dispute, tacitly agreed not to address the question of sovereignty over the islands. But this tacit agreement was now violated. The introduction of a purely ceremonial ‘Takeshima Day’ may have been an action by a prefectural assembly, but, as the Korean side saw it, the fact that the assembly was not restrained by the national government amounted to an act of legitimization of past aggression. As a result, relations between the two countries deteriorated rapidly as President Roh Moo-hyun (1946–2009, in office 2003–08) reversed his originally Japan-friendly position and criticized Prime Minister Koizumi’s stance on the history question. His successor as president, Lee Myung-bak (b. 1941, in office 2008–13), added to the tension when he landed on Takeshima and demanded that the Japanese emperor apologize to Korea for colonial rule.

There is also the question of sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyutai) in relations between Japan and China. This question had remained dormant for many years after the normalization of relations between the two countries in 1972, but it reemerged in September 2010, when a Chinese fishing boat rammed a Japanese Coastguard vessel. Subsequently Chinese ships frequently violated Japanese territorial waters, leading to a rapid deterioration in relations. Tensions between the two countries reached a high point with the nationalization of the Senkaku Islands by the Japanese cabinet in September 2012.

In this unfortunate fashion, the history question became entangled with territorial disputes and continues to haunt relations between Japan and its neighbours at present.

The ‘settlement’ of the question of postwar reparations and the internationalization of the comfort women question

From the mid-1990s on, there were increasingly frequent moves by Chinese to seek individual compensation in Japanese courts of law. This was based on the reasoning that there was a distinction between war reparations paid by one state to another state and compensation for damages paid to the people of that state. The legal argument was that although the former had been renounced in the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué, the latter had not. These individual initiatives were also accepted by the Chinese government.

In April 2007, Japan’s Supreme Court, in decisions in two lawsuits concerning postwar compensation in which Chinese victims were plaintiffs, dismissed the claims while recognizing the fact of forced labour and sexual violence and expressing sympathy for the physical and mental suffering of the victims. This decision was based on the legal opinion that the validity of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which did not recognize compensation based on ‘the right to individual claims’, extended to the joint declarations between Japan and China, and between Japan and the Soviet Union, even though neither the People’s Republic of China nor the Soviet Union had signed the Peace Treaty. In other words, the final judgment issued stated that the right to claim compensation by individuals would not be recognized.

The Supreme Court decision further stated that the exercise of the right to claim compensation by nationals of victim countries ‘would impose excessive burdens on any state and people that were difficult to estimate at the time of the concluding of the Peace Treaty and, moreover, there was a concern that this might also lead to a state of confusion, which would prevent the realization of the goals of the Peace Treaty’. In short, the Supreme Court sought to ensure the legal stability of the Peace Treaty system by putting the brakes on the growing number of individual compensation lawsuits.

Another significant point of the Supreme Court decision was that it forced the government, the people and concerned businesses to find a solution, as it was no longer possible to settle by legal means a historical question dating back more than 60 years. The Supreme Court decision noted parenthetically that ‘it hopes that efforts would be made to compensate the victims’. As a result of this, a number of Japanese corporations such as Nishimatsu Construction reached reconciliation agreements with the victims in the following years.

In this fashion, the way for citizens of the victim countries to seek compensation from the state through lawsuits in Japanese courts was effectively closed. But the history problem transcended the responses of the Japanese government, as well as the Japanese judiciary and it even transcended the question of bilateral relations. The comfort women issue is a perfect example of this. The characteristics of the comfort women issue stem from the fact that this issue is no longer a problem only between Japan and Korea, but has become internationalized as a question of humanity and human rights. Since 1993 the issue has been regularly discussed by the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The Coomaraswamy Report, based on investigations in Japan and Korea and submitted to the Human Rights Committee in 1994, designated former comfort women as ‘sex slaves’ (victims of sexual coercion) and recommended that the Japanese government accept legal responsibility, offer a public apology, pay compensation, and punish the persons responsible. In addition, the report pointed out that, ‘although the Special Rapporteur welcomes the (founding of the Asian Women’s Fund) from a moral perspective, it must be understood that it does not vindicate the legal claims of “comfort women” under public international law’.29 The Japanese government rejected the report, taking the position that it had dealt with the issue with sincerity by means of the Asian Women’s Fund.

In July 2007, the so-called Comfort Women Resolution (House Resolution No. 121) was unanimously passed by the United States House of Representatives.30 The resolution strongly criticized the Japanese Army for coercing ‘young women into sexual slavery’ and demanded that the Japanese government offer a public apology. It also called for the introduction of thorough historical education on the subject. The passing of this resolution by the United States House of Representatives led to similar resolutions being adopted by the parliaments of Australia, Holland, Canada and the European Union. Also in Japan, as many as 40 resolutions and declarations were passed by various local assemblies demanding a sincere response from the government.

On the other hand, a campaign has been launched by a number of private groups and members of Japan’s National Diet seeking a revision of this issue, in an effort to ‘protect Japan’s honour’. This resulted in an issue-advocacy advertisement titled THE FACTS in the 14 June 2007 issue of the Washington Post, which contended among other things that no document had been found to show that anybody was forced to become a military comfort woman. The advertisement also denied that comfort women were sex slaves and claimed that the Kōno Statement itself, which recognized ‘abduction’, constituted the most significant piece of evidence various countries drew upon to criticize Japan.

In December 2015, the foreign ministers of Japan and South Korea signed a new agreement with the intention of ‘finally and irreversibly settling’ the comfort women issue. This would be achieved by means of an expression of apology and remorse by Prime Minister Abe and the provision of 1 billion yen by the Japanese government for the establishment of a relief foundation for former comfort women. Both governments announced that they would not mutually criticize each other in international venues such as the United Nations from that point on.31 With the conclusion of this agreement, the comfort women question reached a final settlement between Japan and Korea, but of course it does not mean that all history problems between Japan and Korea have been settled.

The Korean government continues to adhere to the interpretation that claims for reparations for ‘illegal acts that violate humanity’ fall outside the scope of the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of South Korea. It insists that these ‘illegal acts’ include the coercive recruitment of comfort women, the abduction of workers and coercive mobilization. In July 2013, the Seoul High Court in a lawsuit in which four plaintiffs who were forcedly recruited by Shin Nittetsu (New Japan Steel Corporation) sought to obtain compensation, issued a decision which ordered the payment of compensation. The decision held that ‘coercive mobilization under Japanese rule clashed with the core values of the South Korean Constitution that regards such actions as illegal’ and strongly criticized the position of the Japanese government, which insists that this issue has been ‘settled perfectly and finally’ under the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations and the claims agreement. It is clear that Japan must continue to address problems emerging as a result of the internationalization of the comfort women issue in the context of humanity and human rights.

Prospects for reconciliation

After the end of the war in 1945, the Japanese government avoided the public examination of the question of war responsibility, nor did it seek to formulate an official government opinion concerning war and colonial rule, as well as the true nature of the mobilization system related to both. This is why no government ever produced a clear answer to the questions: ‘Who are the true victims of the war?’ and ‘Who bears the brunt of responsibility for the war?’ This lack of a uniform and coherent view on the wartime past resulted in the loss of international trust, as every time that a history problem arose the government responded inadequately and often too late.

In order to overcome this problem, from the 1990s on the Japanese government initiated a variety of reconciliation policies within the framework of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. These include the Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative, the Murayama Statement, the Asian Women’s Fund, Japan-China and Japan-South Korea joint history research projects and also the 2015 Prime Minister Abe statement that followed up on the Murayama Statement. These reconciliation policies, which to some extent have been appreciated by neighbouring countries, have contributed to an improvement in international relations, but it is difficult to say that they have been appreciated in the key countries of China and South Korea.

Why is that? One can think of many reasons. For example, in Japan, some groups have always denied the evils of colonial rule. This is one factor that undermines trust in the government’s reconciliation policy. In addition, because the government has stubbornly stuck to its legalistic view that the right to claim compensation does not extend to individuals, there has been no way to respond to individual victims. Another obstacle is caused by the territorial disputes between Japan and South Korea over the Takeshima Islands and between Japan and China over the Senkaku Islands, which have become interwoven with the history question. ‘Historical nationalism’ has become inseparable from the territorial question, compounding the difficulty of overcoming the problem.

Looking at more fundamental causes, there are the differences in historical awareness concerning colonial rule and war in each country. The People’s Republic of China maintains ‘the anti-Japanese resistance war view’, which asserts that China’s postwar development is based on victory in the war against Japan, while South Korea regards ‘the illegality’ of colonial rule as ‘the core value’ of the South Korean Constitution, placing it at the centre of the nation’s historical outlook. These differences can be seen also in the joint research projects between South Korea and Japan, and between China and Japan, that are supported by the governments of the states involved.

South Korea and China share a clear tendency to judge the legacy of human endeavours and actions in terms of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, in other words, to see history as a question of morality and moral principles. In contrast, for the Japanese, the fundamental view is that ‘history’ is best left to historians and other researchers, and historical judgments should not be affected by politics or morality. Such views are reflected in historical interpretation and history education, and in this respect attitudes toward Japan as ‘the offending country’ have a tendency to turn into criticisms that are affected by moral judgments.

It is not easy to overcome these differences. Until the 1980s in Japan an optimistic view prevailed that reconciliation with China and South Korea would come naturally with democratization, economic development, generational change of leaders, and the expansion of exchanges. This expectation has dissipated since the 2000s, when Japan’s ability to pursue a policy of reconciliation appears to have reached its limits.

However, historical research in China and South Korea has made much progress since the 1990s and international academic exchanges are now frequent. Under the circumstances, Japan could take the initiative by opening and sharing resources on the modern and contemporary history of East Asia. As a first step in this direction, the digital archive JACAR has made sources available to all citizens of East Asian countries (and elsewhere). This, it is to be hoped, will contribute to the formation of new historical perspectives that will, by means of a multi-faceted dialogue, eliminate mutual criticisms, prejudices, and misunderstandings.

If factions that regard the wars waged by Japan and its colonial rule as a positive achievement are an obstacle to the historical reconciliation policy of the Japanese government, then strong political leadership is necessary to restrain them.

In any event, apologies and reparations based on a peace treaty for large-scale wars and colonial rule possess only symbolic significance that cannot possibly compensate for the mental suffering of the victims or restore the cultural damages caused. For that reason, there will be a need to continuously strive for reconciliation, even after it is believed to have been achieved at a state level. To look at historical reconciliation as a process that requires continuous effort, not to falter in one’s sincere attitude to confront history, and to ensure that this effort is taken up by future generations, is the only way to win back the trust of neighbouring countries and overcome the history problem. A long road lies ahead before this can be achieved.

(Translated by Christopher W. A. Szpilman)

Further reading

Hatano Sumio (2011) Kokka to rekishi, Chūō Kōronsha.

Ishikida, Miki (2005) Toward Peace: War Responsibility, Postwar Compensation, and Peace Movements and Education in Japan, New York: iUniverse.

Yamazaki, Jane (2006) Japanese Apologies for World War II: A Rhetorical Study, London: Routledge.

Yoneyama, Lisa (2016) Cold War Ruins: Transpacific Critique of American Justice and Japanese War Crimes, Duke University Press

Notes

‘Joint Communique of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People’s Republic of China’, website of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (last accessed 2 September 2016).

‘Statement by Chief Cabinet Secretary Kiichi Miyazawa on History Textbooks’ (26 August 1982), website of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (last accessed 2 September 2016).

See the Examination Criteria for High School Textbooks, website of the Ministry of Education (last accessed 2 September 2016).

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East categorized defendants into class A war criminals (accused of crimes against peace), class B (accused of conventional war crimes), and class C (crimes against humanity). See Kushner 2015; Lingen 2016; 2017; Yoneyama 2016; Totani 2008; 2015; Piccigallo 1979.

Enshrinement is a religious ceremony dating back to the Meiji period. All those who sacrificed their lives in incidents and wars in the name of the emperor are enshrined at Yasukuni as deities. Of 2.46 million souls, who are enshrined there, those who died during the Pacific War are the most numerous.

‘Statement by the Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono on the result of the study on the issue of “comfort women”,’ 4 August 1993.

‘Statement by the Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono on the result of the study on the issue of “comfort women”,’ 4 August 1993.

‘Statement by Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama ‘On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the war’s end’. (15 August 1995).