Dedication: This essay is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Arasaki Moriteru, Professor of Politics at Okinawa University who passed away on March 31, 2018.

Introduction

For many years in Okinawa, Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma in the heart of Ginowan City has been synonymous with danger. In 2003, when surveying the controversial installation from the air, United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld remarked that this, “base is the most dangerous in the world.”1 On this occasion, Rumsfeld’s vantage point was that of someone in flight, such as a U.S. pilot or other flight personnel operating from the base rather than that of nearby residents in Ginowan City, then over 90,000. On the ground, the local people experience danger daily in intensely visceral ways.

Especially since the rape of a local 12-year-old girl by three U.S. military personnel in 1995 and the announcement that followed in 1996 to close down MCAS Futenma, stories of danger have been told and re-told in conjunction with the claimed necessity of moving Futenma operations from Ginowan City to the coast of Camp Schwab (Henoko). This claimed necessity, known as the ‘Futenma replacement facility’ (FRF), also necessitated massive land reclamation of the Oura Bay area, which would make marine life expendable. This life extended to include marine mammals such as the dugong, as well as sea turtles and coral colonies and their habitat.

As is well known to readers of this journal, Okinawan people have protested in peaceful, though often impassioned, acts of civil disobedience against the FRF construction plans for over twenty years. These acts put at risk the lives of protestors calling attention to impending risks to the environment. But risk, it should be noted, is also present for American pilots who operate the aircraft. The 2004 crash of a CH-53 Sea Stallion onto the campus of Okinawa International University, adjacent to MCAS Futenma, is another vivid example of imminent risks and constant concerns of those on the ground and in the air.2 Then, Marines from the adjacent Air Station were immediately dispatched to the university and “kicked out not only reporters and cameramen, but also the Okinawan firemen who had come to put out the blaze, [as well as] local police who had come to investigate the cause of the accident, and even the mayor of the town.”3 While the Marines miraculously dodged killing themselves and local people, the crash humiliated Okinawans by denying them sovereignty and inculcating a sense of precarious existence under a foreign occupation force, in their own land.

|

Figure 1: source, Authors (December 22, 2017) |

Local residents’ sense of danger has been resurrected recently by a series of potentially life-threatening accidents in December 2017: landing of a window frame and a cylindrical object on the adjacent residential area in Ginowan City, both from a flying CH-53 Sea Stallion deployed at MCAS Futenma, respectively striking an elementary school ground (one child was slightly injured),4and the roof of a child care center.

VFP-ROCK Announce Findings on ‘Clear Zones’

At a press conference on March 5, 2018 in Naha City,5 veterans of the U.S. military and Japanese Self-Defense Forces (as well as associate members) of Veterans For Peace – Ryukyu Okinawa Chapter Kokusai (VFP-ROCK) publicized an open letter to General James N. Mattis, U.S. Secretary of Defense, alerting the public to the base’s infringement of regulations regarding ‘clear zones’ set by the U.S. Navy. The group called for the immediate closure of the base. The letter emphasizes the fact that military veterans remain driven in large measure by concern for the safety of pilots and flight personnel as well as by their commitment to peace.

Directly addressing a long list of the highest ranking decision-makers of the U.S. national security state,6the letter plainly highlights the importance of safety to U.S. military personnel and cautions against the next big accident that may endanger the future viability of Okinawa itself as a U.S. military outpost. VFP-ROCK’s open letter joins other local public demands to halt, among other things, all routine U.S. military flights above educational institutions (Figure 1 illustration): eight local university presidents and the headmaster of a national institute of technology in Henoko, all publicly appealed just three days after the VFP press conference to both Tokyo and the U.S. military to cease all flights over educational institutions in Okinawa (pre-school, primary, secondary and tertiary).7

The present article examines the recent VFP-ROCK effort to publicize the U.S. Navy’s ‘clear zones’ safety regulations and their connection to the ongoing transnational court case against the DoD’s plan for Futenma’s replacement facility (FRF) construction in Henoko-Oura Bay for failing to protect the survival of the endangered Okinawa dugong. This article argues that the maintenance of the Futenma Base ultimately undermines the legitimacy of the Japanese and U.S. governments’ mutual policy of dealing with ‘danger’ by transferring it to another location in Okinawa. Together with the audio-visual records accompanying the analysis, the article underlines the danger that Ginowan City residents live with daily while pointing out the irony that the legal initiative for the dugong conservation might, in fact, protect the safety of U.S. personnel flying to and from MCAS Futenma.

‘Clear Zones’ in the Letter of the Law

In its open letter, VFP-ROCK shared with the public the incriminating evidence that MCAS Futenma is the most dangerous base in the world: this base patently breaches the U.S. military’s own safety regulations governing the legal uses of U.S. airports and airbases. The central element of the U.S. military’s safety regulations here is distilled in the ‘clear zone’ regulations: “areas immediately beyond the ends of runways and along primary flight paths, [which] have the greatest potential for occurrence of aircraft accidents and should remain undeveloped,” as stipulated in [4.a.(1)] of Section 11010.36c of the US Navy’s Operations Instructions (OPNAVINST).

This OPNAVINST Section documents formal orders of U.S. Naval policy, procedures, and requirements for the safety of Navy and Marine Corps Air Installations, issued by the Chief of Naval Operations. It mandates the existence of clear zones, “for all active runway ends” [4.b(1)] and “No structures (except airfield lighting) buildings or aboveground utility/communications lines should normally be located in clear-zone areas on or off the installation” [Note 4 to table 2]. Namely, the regulations specify that no structures within the so-called clear zones should be present either on or off military installations.

|

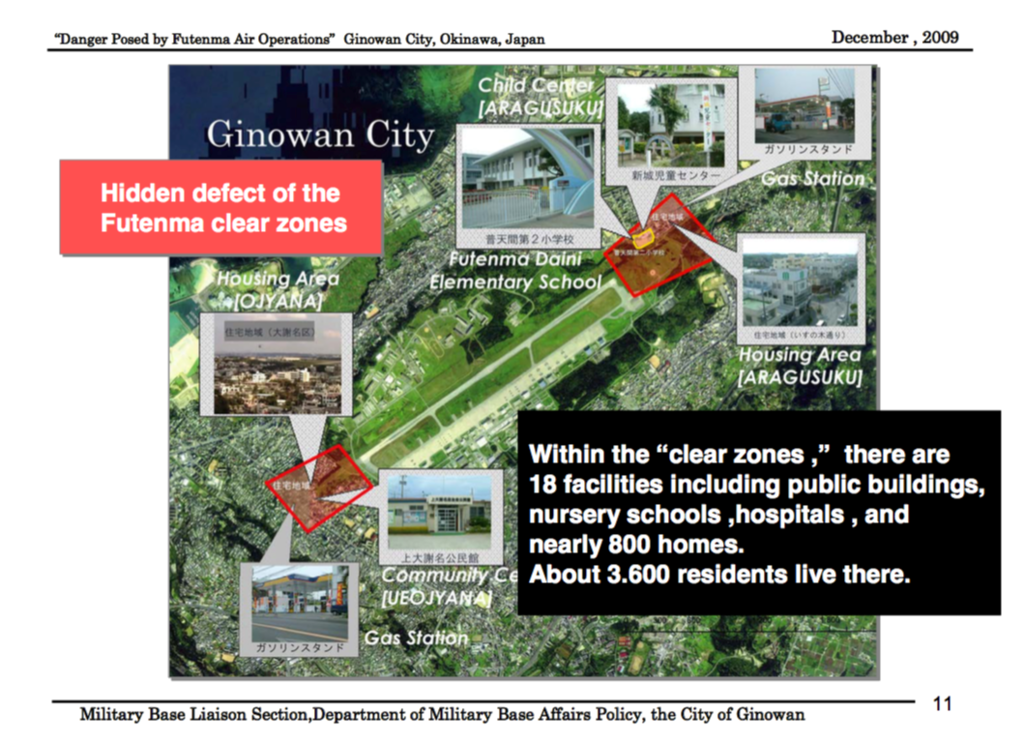

Figure 2: “Danger posed by Futenma air operations” |

MCAS Futenma flight operations clearly violate OPNAV regulations: as Figure 2 shows, there are 18 educational institutions within its so-called clear zones, where the regulations specify that no civilian structures should be present, either on or off military installations.8 While much of the northern clear zone is occupied by a stretch of trees (clearly visible in Figure 3), it appears from a glance at overhead imagery to be bounded tightly on both sides by numerous civilian structures such as houses and schools. The image in Figure 3 shows how a window and its frame could have landed at Futenma Daini Elementary School onto the playground in December 2017 as a CH-53 Sea Stallion9 approached the Futenma flight line.

|

Figure 3 |

The trouble appears much more evident at the southern approach of the clear zone. Occupied by Kamiojana, a local community crammed with homes and places of business, the area also features a popular park and playground directly on the flight path just outside the fence line. On any day free from rain many children and their families enjoy leisure or sporting activities at Sakura Koen (Park). The panorama view in Figure 4 illustrates the direct line from approach lights (within the fence) to the park and playground beyond where countless houses and apartment buildings also lie.

|

Figure 4: Panorama of Sakura Park with southern approach to Futenma Air Station |

How does the Futenma base maintain operations in light of obvious violations of OPNAV ‘clear zones’ regulations? The adverb ‘normally’ in Section 11010.36c 4.b(1) potentially releases MCAS Futenma from the infringement for being located outside “US territories or its possessions.”10 For U.S. activities in overseas bases, as in Okinawa, OPNAVINST dictates the development of Air Installations Compatible Use Zones (AICUZ) studies, “if such action supports host nation policy for protecting operational capabilities of those activities, and for on-base planning goals.”11

The bottom line of the AICUZ Program is the imperative of curtailing crashes and accidents between the U.S. forces and, in the case of Futenma, the government of Japan. Although the Environmental Review Report for the MV22 Osprey at MCAS Futenma acknowledges the clear zones “encroachment” into surrounding residential areas, the AICUZ studies on MCAS Futenma have been limited to a “noise study only.”12Safety issues arising from aircraft crashes and other mishaps around the Futenma base are simply ignored.

Thus, VFP-ROCK argued for developing comprehensive AICUZ studies on the present danger of aircraft crashes and accidents, “relating to the safety not only of the citizens of Ginowan City but also to … the pilots and passengers on aircraft flying in and out of MCAS Futenma.”13 Lummis offers an important observation: “On that tragic day (Friday the thirteenth) in 2004, those boys [Marines] might have got their helicopter back into the base if that tall school building had not been in the way.”14 If destruction of Oura Bay is to proceed for the planned FRF, construction of the new base will require decades. “Waiting, with fingers crossed,” Lummis observes, “for the new base to be built [without another mishap at Futenma] is hardly a solution.”15 The VFP-ROCK letter concludes with a call for the immediate closure of MCAS Futenma, with or without the FRF to protect U.S. pilots and crewmembers navigating their approaches to the Futenma base over the natural landscape and civilian ‘obstructions’ (schools, hospitals, buildings, parks).

The Dugong Connection

The members of VFP-ROCK appear to have taken their cues from Rumsfeld’s 2003 “most dangerous base in the world” remark. His observation suggests the possibility that U.S. leaders might, at least, consider the Base closure out of concern for the safety of U.S. military personnel, in contrast with the low level of concern shown to the local residents’ safety. Repeated pleas over the years from Okinawan people to immediately close the Futenma Base have been met with the U.S. and Japanese governments’ mantra of an imperative to speed up the FRF construction in Henoko-Oura Bay. The recent VFP-ROCK open letter, calling for the prompt closure of the Futenma Base, and other Okinawans’ protests against FRF in Henoko-Oura Bay, may appear to casual observers to be separate calls for action—isolated collective actions with different emphases on exactly whose safety is of priority. This, however, is not the case.

The intelligence on the OPNAV regulations, not easily accessible to the general public, was unearthed and shared twelve years ago by the renowned Naha architect Makishi Yoshikazu, whose technical and scientific contributions to the movement have been critical over the decades. Makishi is one of the Okinawan plaintiffs in the ongoing transnational lawsuit, for endangering the Okinawa Dugong’s survival, against none other than Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld since September 2003 (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: Graphic illustration of former U.S. Navy Captain (O6) Rumsfeld squared off against Okinawan marine mammal. |

The Okinawa Dugong, three Okinawan residents, as well as U.S. and mainland Japanese environmental NGOs have taken the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) to court in the United States on the charge of violating the National Historic Preservation Act (NHLA) in “Section 402 by failing to take into account the adverse effects of base construction plan on the dugong in drawing up the construction plan” of the Futenma Replacement Facility in Henoko-Oura Bay, demanding that DoD cancel its construction.16

During hearings over the lawsuit, Makishi discovered the OPNAV instructions on ‘clear zones’, among numerous documents submitted by the defendant (DoD) to the court, to assess the applicability of NHLA to this case.17 Makishi recognized that the U.S. government’s own documents show illegal flight operations at the Base.

Makishi shared this knowledge with then Mayor of Ginowan City, Iha Yoichi, who declared the Base’s “safety failure” on 1 November 2006, on the basis of its violation of OPNAV ‘clear zone’ regulations. The Mayor of Ginowan City demanded an immediate closure of the Base, just as VFP-ROCK has recently done. When VFP-ROCK was established in October 2015, Makishi joined as a founding Associate Member, and in March 2018, with VFP-ROCK Coordinator Douglas Lummis, he wrote a letter addressed to the U.S. State Secretary this time stressing the safety of U.S. personnel. Transnational advocacy to stop further U.S. military build-up in Okinawa has organically developed an alternative perspective of the ‘danger’ associated with the Futenma Base among the environmentalists and military veterans working tirelessly for peace: in this case accentuating the safety of American personnel, and the planet’s marine biodiversity.

Dangers Yesterday and Today: Why the ‘Clear Zones’ Can’t Be Cleared

Observers unfamiliar with history often ask why Okinawans would even build their homes in such immediacy to an active airbase. MCAS Futenma was constructed just after the Battle of Okinawa.18 With local people still held in concentration camps as refugees, U.S. military bulldozers arrived in Ginowan to bury tombs and flatten houses and farmland for the new base construction. Local residents were essentially kicked out—many had no choice but to remain in the vicinity of the airbase and attempt to rebuild their lives and livelihoods. Today, the people of Okinawa Main Island have, for the entire post-WWII decades, lived with U.S. military aircraft operating from the various bases in close proximity to the now-dense populations whose dwellings and places of business have been both threatened by and struck by aircraft.

Nevertheless, MCAS Futenma has not represented the sole danger to local residents. Though 59 years have passed since the tragedy, yearly commemorations are held at Miyamori Elementary School in Uruma City where, in 1959, a U.S. fighter pilot safely ejected from his troubled jet (based at Kadena Air Base) which flew unmanned and crashed into the school, killing 18 children. As participants in the annual ceremony “pray for the repose of the victims … and for lasting peace,”19 casualties of U.S. military ‘mishaps’ continue to constitute a collective trauma that remains engraved in the island’s history of colonialism.

Today, besides the approaches over ‘clear zones’ taken by fixed-wing aircraft, such as the C-130, various rotary-wing aircraft based at MCAS Futenma also routinely circle over Ginowan City and other neighboring urban areas on training flights. Figure 6 illustrates the proximity of flight with the structures on the ground.

|

Figure 6: CH-53 Sea Stallion on routine over-flight. |

We describe this area in greater detail in our book Okinawa Under Occupation (2017) because of widespread comments offered by conservative commentators that this location in Ginowan City, with its natural topography and structural barriers, is neither threatened by nor a threat to approaching U.S. military aircraft. The aircraft, we point out, “come in so low over Maehara and Kamiojana … that observers, if they were standing on someone’s rooftop enjoying the view, will develop the sense that they can touch the bellies of the aircraft.”20 An illustration of what people in the community experience on the ground and what pilots must navigate through on their approach can be found in the video clip (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7: Osprey overflight of Kamiojana housing area |

Various commentators both inside and outside of Japan have, we feel, hastily dismissed the safety issues and have downplayed the real potential for another future mishap involving these aircraft. We suspect that such commentary comes from a position of relative ignorance assumed by people who remain geographically remote from the position of people here both on the ground and in their training maneuvers overhead. The March press conference in Naha prompted us to examine more carefully the perspectives of people on the ground as well as in flight. While military regulations preclude our engaging directly with pilots of these aircraft, we were able to reach out to those who make their lives in the Futenma clear zone among the prohibited “buildings [and] aboveground utility/communication lines.” The video clip at Figure 8 illustrates the difficulties experienced by both residents and pilots.

|

Figure 8: Osprey overflight of Sakura Park |

Viewers of the video can see a typical over-flight and experience the sound and close proximity of the aircraft to people in the park. Of course, it is not possible to communicate through the clip the vibro-acoustic dimensions of noise from aircraft that pass overhead and the sound waves that pass into objects on the ground below, but the words and reactions of those in the park impart something even more meaningful. While the children continue to play as though pretending that the recurrent presence of aircraft does not exist, the parents offer more telling, if terse, insights. When asked to share their impressions of the situation, they shrugged and wondered aloud, “What can we do with this absurdity?”21

Conclusion

The summer of 2018 will see 73 years since the end of hostilities in WWII, and in that time, the Okinawan people collectively have had virtually no say in the variously absurd ways their limited land, sea, and air have been appropriated and used by outside powers. Changing the history of deprivation of land rights and safety of local residents requires facing a ‘political’ question: long-standing military colonialism in the name of maintaining the Japan-U.S. Mutual Security Treaty, and the unanswered question of why Tokyo steadfastly refuses to entertain the possibility of locating FRF construction in mainland Japan.

Efforts to conduct reasoned discussion of the rights and equality of the Okinawan people in contemporary Japan have not only fallen on deaf ears, but also generated vilification and hate speech directed toward Okinawans protesting these conditions—residents living near the Futenma Base and even those involved in the aircraft accidents.22 To achieve closure of the Futenma Base and halt FRF construction in Henoko, VFP-ROCK and Okinawa Dugong plaintiffs appear to have strategically diverted focus away from the obvious political questions central to the Okinawans’ struggle;23 instead, both have focused on the real concern of safety for American personnel and the dugong. In August 2017, the US Court of Appeals favorably ruled that the Okinawan plaintiffs had legal standing to demand that the DoD comply with NHPA, that is, to take necessary procedures to minimize negative effects on the dugong’s survival.24 “This ruling,” notes Peter Galvin at the Center of Biological Diversity in San Francisco, “is a critical lifeline for the highly endangered Okinawa dugong.”25

Such humanitarian and planet-level consciousness in the long term could be significant in eventually undermining the legitimacy of FRF, and the governmental logic of re-locating ‘danger’. This article has stressed, however, that the most visceral aspect of the ‘clear zones’ is the fact that the residents, schools, hospitals and other public facilities refused to bow, ‘clear out’ and make space for the occupying forces. Local people who continue to abide in the ‘clear zone’, defying the obvious risks to their own lives and that of their children, might well be the longest running act of civil disobedience.

|

Related Articles

•Hideki Yoshikawa with an introduction by Gavan McCormack, “U.S. Military Base Construction at Henoko-Oura Bay and the Okinawan Governor’s Strategy to Stop It“

•Gavan McCormack, “There Will Be No Stopping the Okinawan Resistance,” an Interview with Yamashiro Hiroji

•Makishi Yoshikazu, “US Dream Come True? The New Henoko Sea Base and Okinawan Resistance“

Notes

Given the crash into the main administration building and the resulting fireball, it is hardly hyperbole to describe the survival of the Marine Corps helicopter flight crew and the people on campus as a miracle.

C. Douglas Lummis. “Mission Creep Dispatch: C. Douglas Lummis,” Mother Jones, September 19, 2008 here.

Details of the conference can be found March 6, 2018 Ryukyu Shimpo article, “普天間閉鎖、米に要請 元軍人の会国防長官ら11人に” (p. 28).

The letter was addressed to Secretary of Defense James Mattis; Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joe Dunford; Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer; Commander of US Force Pacific Admiral Harry Harris; Commander of US Force Japan LTG Jerry Martinez; US Ambassador to Japan the Honorable William Hagarty; the US Consul General to Okinawa the Honorable Joel Ehrendreich; and the Chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee Senator John McCain.

Further details in Japanese can be found here. In early February 2018, “the headmaster and members of the parent’s association of Midorigaoka nursery school visited Japanese government officials in Tokyo to deliver a petition with more than 10,000 signatures” (Lisa Torio, “Okinawans Demand End to US Military Flights Over Schools” Aljazeera, 27 February 2018). The Chair of Okinawan Educational Committee submitted a request to the Defense Ministry to end all flights above all primary, secondary and special educational facilities (“全学校上空の飛行禁止を要求 沖縄県教委、国に異例の要請 米軍機事故多発受け、入試や式典時の騒音防止も” Ryukyu Shimpo, February 16, 2018) also, see “学校上空の飛行中止求める 相次ぐ米軍機事故、沖縄の大学学長ら「異常事態」”

Military Base Liaison Section, Department of Military Base Affairs Policy, the City of Ginowan, “Danger Posed by Futenma Air Operations” December 2009, Ginowan City

Letter to General James N. Mattis, U.S. Secretary of Defense from Veterans For Peace-Ryukyu/Okinawa Chapter Kokusai (VFP-ROCK), “Impermissible encroachment at MCAS Futenma” (March 2018).

Department of the Navy, Air installations compatible use zones (AICUZ) program procedures and guidelines for Department of the navy air installations (Washington DC: 9 October 2008), A-3.

Department of the Navy. Marine Corps Air Station Miramar: AICUZ Update (Naval Facilities Engineering Command: CA, 2005), 11.

Letter to General James N. Mattis, U.S. Secretary of Defense from Veterans For Peace-Ryukyu/Okinawa Chapter Kokusai (VFP-ROCK), “Impermissible encroachment at MCAS Futenma” (March 2018).

Hideki Yoshikawa, “Dugong Swimming in Uncharted Waters: US Judicial Intervention to Protect Okinawa’s ‘Natural Monuments’ and Halt Base Construction,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 6-4-09 January 29, 2009, 4.

Miyume Tanji, “U.S. Court Rules in the ‘Okinawa Dugong Case’: Implications for U.S. Military Bases Overseas” Critical Asian Studies, 40(3) 2008, 482, and United State District Court Northern District of California, No. C 03-4350 MHP., “Memorandum & Order,” Okinawa Dugong (dugong), et al., vs. Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense, et al., March 1, 2005.

C. Douglas Lummis, “Futenma: ‘The most dangerous base in the world’, The Diplomat, March 30, 2018.

“Remembering the tragedy of U. S. military Jet Crashing onto Elementary School,” Ryukyu Shimpo (English), July 1, 2011

Miyume Tanji and Daniel Broudy, Okinawa Under Occupation: McDonaldization and Resistance to Neoliberal Propaganda (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 122.

For example, at the Futenma Daini Elementary School, various teachers have received phone calls as well as emails from people in mainland Japan accusing the teachers in Okinawa of deliberately ‘fabricating the accident’ and for ‘not moving’ the school or teaching activities. 沖縄中傷にも苦しむ 基地そばの学校「動かせばいい」(“Hate speeches against Okinawa also taunt schools near military bases: ‘just move it’”). Tokyo Shinbun, December 22, 2017.

On the post-war ‘Okinawa struggle’, see Arasaki Moriteru, Okinawa Sengo Shi (Tokyo: Iwanami, 1976), Arasaki Moriteru, Okinawa Gendai Shi (Tokyo: Iwanami, 2005), and Miyume Tanji, Myth, Struggle and Protest in Okinawa (London: Routledge, 2006)

Courthouse News Service, “9th Circuit Revives Fight for Endangered Dugong on Okinawa”

August 21, 2017

Center for Biological Diversity, “Court Affirms Right to Sue U.S. Military Over New Base’s Threats to Endangered Okinawa Dugong” 21 August, 2017