|

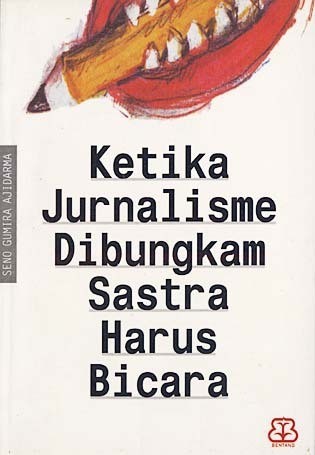

Cover of Seno Gumira Ajidarma, Ketika Jurnalisme dibungkam hastra harus bicara (When Journalism is Silenced, Literature must speak). |

Introduction

“When journalism is silent, literature must speak,” in the words of Indonesian writer Seno Gumira Ajidarma, whose reporting on the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre in Timor-Leste (East Timor) broke the silence about the killings in Indonesia.1

In 1965-66, as many as a million Indonesians, and perhaps more, died in a wave of violence following the seizure of power by General Suharto. The events are now well covered in scholarly work in English.2 Army officers spurred on killings of suspected leftists and many more were arrested for their political views, becoming “tapol” (political prisoners, from the Indonesian phrase tahanan politik). Several scholars have also pointed to the role of the United States government in encouraging the Indonesian army to carry out the mass killings, a complicity highlighted decades ago and confirmed by recently-declassified US government documents.3

The most famous Indonesian literature outside the country is the Buru quartet of books by the writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer, written while Pramoedya was a tapol on the island of Buru.4 The writings of Eka Kurniawan also reference the 1965 killings.5 Half a century later, debate about the “1965 events” continues to face challenges, even in post-Suharto democratic Indonesia.6 Literature may speak more freely than journalism even now.

|

Cartoon from TAPOL Bulletin |

The Indonesian armed forces invaded Timor-Leste (East Timor) in 1975 and colonized it for 24 years, with the cost of more than 100,000 lives – estimates of the death toll run as high as one-third of the population.7 Timorese students were forced into the New Order educational system, which placed heavy stress on a nationalist view of Indonesian history and continually underlined the regime’s basis of legitimacy as the force that vanquished an alleged communist coup effort in 1965 and “saved” the nation. Only after the fall of Suharto and the dismantling of his “New Order” system of control were the Timorese granted a referendum, in which they voted overwhelming for independence. After the fall of Suharto, Timor-Leste was able to regain its independence and elected governments took office in Indonesia. Indonesian civil society activists, long repressed, burst into the open. It became possible at last to discuss the “1965 events” more openly. At the same time, the Indonesian military and elite figures linked to the New Order remain influential, and have often resisted the more open tone of conversations about 1965.

As Indonesian military elites try to downplay discussion of the massacres that engulfed their country in 1965, a powerful new poem from emerging Timorese writer Dadolin Murak expresses solidarity from now-independent Timor-Leste for the victims of 1965 and those trying to debate the 1965 tragedy today. “General!” is a wake-up call and a warning that is receiving wide distribution in the Indonesian language. It is an intervention from a formerly colonized land into Indonesian debates by one of a generation of Timorese intellectuals who came of age within the New Order educational system, but also within Indonesian pro-democracy activism.

In 2017, he published “General!”, a powerful “poem of solidarity from Timor-Leste for the discussion of the 1965 tragedy in Jakarta and victims of the 1965 tragedy.” Written in Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia),8 it aims, as Murak writes, to speak to silences and to help advance the Indonesian national debate on the 1965 killings. It opens with a reference to the way the 1965 coup was taught to the poet and other students during the Suharto era, passes through a litany of the suffering of Timor-Leste under Indonesian occupation, and ends with a call of solidarity with Indonesian activists that echoes solidarity from Indonesian activists for Timor-Leste expressed back in the 1990s.

“General!” was not published in a literary journal or book. Instead, it was part of a proliferating “Facebook literature” of poems and prose in the highly-networked world of Indonesian-language Facebook.

Below is the English translation of the poem “General!” with explanatory notes. An edited transcript of an interview with Dadolin Murak follows.

General!

Dadolin Murak

General!

We didn’t know

The dark affair of 30 September 1965

When you came

We were indoctrinated by your false history:

Cutting genitals

Slashing with razors, gouging out eyes

Joined the communist cavorting at Lubang Buaya9

General!

We were forbidden to speak of Boaventura and Nicolau Lobato

You forced us to memorize the seven Heroes of your Revolution

You even forced us to memorize the number of feathers on the Garuda’s wings10

Statue of Nicolau Lobato, Dili, 2017 (Photo by Cintia Gillam)

And the birth date of Diponegoro and Imam Bonjol

Not forgetting Suharto’s ancestors and grandchildren who we knew by heart

He called them the perfect Pancasila family! 11

General!

Your methods were truly sadistic

To stamp out the seeds of resistance

Yet through 24 years

Still we proved

That all your weapons were not as sharp

As the steel of our resistance

General!

From the land you once colonized

Our hearts torn open

The rank tactics you long used

To gag and kill us

You still use

Towards the children of your own nation

General!

Our country still has many troubles

But a discussion of history

Has never been raided by the state apparatus

discussion is a pre-condition

for human civilization

In our country, General!

The muezzin’s call to prayer and the Alleluyah choir

Resonate together as if in a sonata

Gay and Lesbian people hold hands

With no fear they will be tortured by the Police

Timor-Leste’s first LGBT+ Pride Parade, Dili, 2017 (Photo courtesy Hatutan, a Timorese LGBT+ rights group)

General!

Today is September 30th

A dark day in the history of your country

And of the world

The same month

September 1999

You scorched the earth of our small country

You used bullets

When you failed at the ballot box

General!

There is still a long litany of bleak history

The May 1998 tragedy in the heart of your country

The kidnapping of Wiji Thukul and his friends

The poisoning of Comrade Munir

The massacre in the land of Cendrawasih

Santa Cruz, 1991 in Dili12

General!

Let our friends speak out

About the history of civilized nations

They are the children of that dark history

Learn from history

The barrel of your guns

Can’t silence

The cry for justice from the children of your nation!

Dili, September 25, 2017

Interview with Dadolin Murak

Q. Why did you decide to write this poem? And why in Indonesian?

Many of us Timorese students that grew up during the Indonesian time were taught about Indonesian history. I attended elementary school to Senior High School in Timor and later continued my study in Indonesia. I only had a chance to read properly about Timorese history when I came to university in Indonesia, where I was able to access very rare historical books.

In elementary school, and especially in middle school (SMP) and high school (SMA), we were indoctrinated with the New Order (ORBA)13 government’s version of history through subjects such as the History of the National Struggle (PSPB, Pendidikan Sejarah Perjuangan Bangsa). One main part of the PSPB was the story of the September 30 Movement/Communist party (Pemberontakan 30S/PKI) alleged coup attempt of 1965. Our teacher asked us to watch the government-approved film G30S/PKI. At the end of the course, we had to write about the tragic history of Indonesia. But, the paper was supposed to be written in the spirit of the ORBA version taught by the teacher. Sometimes, we had to copy the photos of the generals that were murdered in Lubang Buaya14 and put them in our paper. So, basically, we wrote the text from the book into our paper without any new information or critical thinking.

I was a bit critical of the official version of the history, but there were no other sources of information at the time to counter it, so I didn’t give much attention to other versions. My eyes were more open when I came to Indonesia and started to become involved in various critical students group in Indonesia in the 1990s in Java. I was involved in the Timorese clandestine student group, but at the same time started to be active with student’s movements in Java.15 So, many of us Timorese students, especially those who were involved in clandestine activism, came to the conclusion that the Indonesian people were facing the same “enemy,” namely the military regime under Suharto. The Indonesian people also had been indoctrinated by the regime with false history such as G30S/PKI and of course, about the invasion of Timor-Leste as well.

I started to read some alternative books on the PKI as well as novels of the great Indonesian author Pramoedya Ananta Toer. I became aware that the ORBA regime had slaughtered its own people. Indonesians weren’t aware of that or, if they were aware, they were scared to speak up.

I wrote this poem “Jendral” as a genuine gesture of solidarity to the victims of this tragedy. I was so upset, after more than 50 years, that the victims still had not received any formal state apology, and worse still, had been denied their rights. Although we in Timor-Leste have achieved our independence, we are still following the efforts of our Indonesian comrades to get justice for victims and families arrested after the “1965 events,” justice for West Papua, and so on.16 We also still have the same “homework” regarding the past atrocities committed by the Indonesian armed forces (ABRI) in Timor-Leste. So, for me, fighting for human rights should transcend national borders.

I wrote the poem in Bahasa Indonesia as a better way to reach Indonesian audiences. And I have to say that Indonesian was my first academic language as I was forced to learn it from elementary school through university. Of course, the sad part was Tetun was ignored during the occupation. And I am glad that now I am also comfortable in writing in my native language, Tetun.

Q. The poem has received wide distribution online, especially on facebook. Can you describe some of the reactions?

Yes, since I put the poem on my FB wall, hundreds clicked “like” and hundreds of FBookers have shared it, too. I got responses from Aceh to Papua and from some other countries. In general, most people like the poem and agreed with its contents. Just a few people challenged the poem and accused me of being ignorant of Indonesian history, even of “having an agenda to divide the Indonesian nation” (“ada agenda untuk memecah-belah Bangsa Indonesia”), which I think is very silly.

Here is a long comment by Wisnu Trihanggoro, former head of the Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA):

The Dadolin Murak poem above reminds me of the Santa Cruz Cemetery I visited in May last year (2016). This is one of the best known cemeteries in the world. On this site, about a quarter of a century ago (in 1991) there was a brutal massacre of hundreds of Timorese civilians.

Memorial to the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre, Dili, 2015 (Photo by David Webster)

Tragically, this was carried out by Indonesian soldiers who every day swear the military honour vow (sapta marga). The state should assign them to protect every citizen. They should practice the Five Principles (Pancasila),17 especially the principle of a just and civilized humanity.

Timor-Leste was declared part of Indonesia. The Indonesian government under the Suharto regime imposed that annexation unilaterally. The government should also have been responsible for protecting the Timorese, in keeping with its duty to protect other Indonesians.

However, history records the opposite. Instead of protecting them, they brutally sacrificed them. Thousands of unarmed people were shot. At that moment in 1991, Timorese protesters flocked to the cemetery after attending a mass for the slain Timorese activist Sebastiao Gomes, who had been shot a few days before.

More than 250 lives were lost in the massacre. An unknown number were wounded. At the entrance to the cemetery, where I stood later, scores of people had their lives ended without mercy.

A few months after that event, in Salatiga, I witnessed the savagery through a video taken by British journalist Max Stahl. There is a clear picture of the violent faces of the soldiers of the Pancasila state.

But last May, I visited the site of the tragic events that I had seen in the video. My good friend Nuno Saldanha took me to the site of the slaughter. He also introduced me to some of the survivors who had witnessed it.

Nuno is himself a survivor of that massacre. He told me how he had saved himself together with thousands of other helpless mourners who could only run and hide.

Santa Cruz is a silent witness which the Timorese will never forget. In this cemetery my heart and feelings were torn open. Thoughts passed through my mind of the hundreds of people who lost their lives.

Reading Dadolin Murak’s poem brought my painful feelings flooding back. The poem represents the inner turmoil of Timorese whose families were slaughtered at Santa Cruz.

Ahh, not only them. Santa Cruz was not the only sacrifice. Those massacred in other parts of Timor-Leste during the quarter-century of Indonesian occupation number in the thousands, as much as half the population of the territory. (Ironically, the preamble of the 1945 Indonesian constitution states clearly that ” independence is the inalienable right of all nations, therefore, all colonialism must be abolished in this world.”)

I am also convinced that Timorese feeling of trauma is also experienced by many Indonesian citizens. In Aceh, in Papua, even in Java and elsewhere that suffered in 1965, Tanjung Priuk, 1998, and so on, it is impossible to deny the pain of recalling the abominations of soldiers who lightly spew bullets from rifles they were supposed to carry with care.

The bullets are bought with the people’s money. The bullets are supposed to protect the people from the threat of other countries that might threaten the state’s sovereignty. Not to slaughter the people themselves.

Greetings of solidarity! Obrigada!

Others agreed, but questioned how to change the situation. One wrote: “Speechless… But how & what we can do against the circle of the most powerful system of the nation ??????????”

As I said, mostly they liked and agreed with the poem, except for a few commentators that questioned the poem’s version of events. For example: “People from the regions: Aceh, Papua or East Timor hate the army and the New Order government because those regions used to be Military Operations Zones (DOM). If you read books written by anti-New Order writers it will look bad depending on which source we use.”

To make it short, I was surprised that the poem got so many responses from so many Indonesian friends as well as Timorese friends.

Q. Do you aim to contribute to a conversation on justice for victims of 1965 and to a more open climate for discussion in about 1965 in Indonesia? How about in Timor-Leste?

Exactly, that was my main objective. It is time for the Indonesian government to open up discussion of this tragedy. Victims and families, as well as the perpetrators, should be brought together to discuss this dark chapter in not only the history of Indonesia, but also the history of mankind.

We have organised a movie night to screen “Silence”18 and discussed it with activists and students in Dili. We also still have the task to fight for justice for the past human rights abuses. So, solidarity with the Indonesian people is paramount in order to demand justice for human rights victims during the illegal occupation by the Indonesian military regime. Of course, we are also sad to see our current national leaders that choose to embrace those former Indonesian army generals allegedly involved in crimes against humanity in Timor-Leste in the past. They ignore the rights of victims and survivals in Timor-Leste, thus perpetuating the cycle of impunity in Timor-Leste.

Q. Human rights seem to be a big aspect of your writing. Did your own experiences shape your attitudes to human rights?

As I have described, I was born in Timor-Leste and only went to Java to study in university after I finished senior high school.

My childhood was full of bad memories, since we had to move from one place to another in order to survive the military attacks. I witnessed my sister dying because of malnutrition during the war. I heard so many atrocities encountered by fellow Timorese as I grew up. Lost families and friends are the litany of my childhood in Timor. As I came to Java to study, still the same litany that I heard every day from relatives and friends in Timor. I was just lucky: although I was involved very actively in the clandestine movement, I managed to escape the military, although so many friends were sentenced to jail.

Apart from the human rights theme, I also write poems and story about other things, i.e, love poems, environment, culture and politics as well. I weave cultural aspects, myths, contemporary politics and some satire into my poems and stories.

Q. What do you think the future holds for Timorese poetry and literature?

To be frank, it is a bit sad. There are no outlets for Timorese writers to express their talents. Few local newspapers publish poetry and fiction. Lately, Timor-Aid NGO has been trying to publish some novels in Tetun which I think is a good move. There is no attention at all from the government side, instead they love to hire “consultants” to write very thick report with very expensive budgets although they themselves do not read the reports.

One important thing is that an increasing number of Timorese writers write in Tetun, the native language of Timor-Leste, although some “consultants” and a few “Timorese leaders” are still sceptical that we can express our ideas scientifically and write fiction in Tetun. We are proving that we can do that, and of course there is no doubt that we need to keep developing Tetun.

There are so many talented Timorese writers, but they get no support and facilities at all from the government or any other institutions. So, what I am doing now is “Facebook literature” since there are no other means. But I am quite happy to see so many friends, students, especially those in the Dili middle class, respond to my writing without even knowing me personally. Many school teachers asked permission to use my poems and stories to teach their students. And I said, please, go ahead. Most of them praise the poems and short stories that I put on my FB wall. Some of the responses to my poems are actually beautiful poems written by many Timorese poets. Every time I post my poem, they write their own poems on my FB wall. It is a fantastic exercise, where we create our own space of creativity. I hope to find a sponsor to publish my collection of poems and short stories this year.

|

Cover of a recent book of Tetun-language poetry, edited by Dadolin Murak and Hugo Fernandes. Its colours evoke the Timorese flag. |

Notes

Seno Gumira Ajidarma, Ketika Jurnalisme Dibungkam Sastra Harus Bicara (Yayasan Bentang Budaya, 1997). See also Seno Gumira Ajidarma’s collection of short stories, including a powerful account of the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre in Timor-Leste, Saksi Mata [Eyewitness] (Yayasan Bentang Budaya, 2002).

Amongst many sources on the 1965 coup and mass killings, see John Roosa, “The State of Knowledge about an Open Secret: Indonesia’s Mass Disappearances of 1965–66,” The Journal of Asia Studies 75, no. 2 (2016): 281–97; John Roosa, Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’Etat in Indonesia (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006); Douglas Kammen and Kate McGregor, eds., The Contours of Mass Violence in Indonesia, 1965–68 (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2012); Robert Cribb, ed., The Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966: Studies from Java and Bali (Clayton, AU: Monash University Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, 1990) and most recently Geoffrey Robinson, The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

Peter Dale Scott, “The United States and the Overthrow of Sukarno, 1965-1967,” Pacific Affairs (Vancouver, B.C.) 58 no. 2 (Summer 1985): 239-64. ; Peter Dale Scott, “Still Uninvestigated After 50 Years: Did the U.S. Help Incite the 1965 Indonesia Massacre?“, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 31, No. 2, August 3, 2015; Bradley R. Simpson, Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.-Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968 (Stanford University Press, 2008); Alfred W. McCory, In the Shadows of the American Century. The Rise and Decline of US Global Power, (New York: Haymarket Books, 2017); Bernd Schaefer and Baskara T. Wardaya, eds., 1965: Indonesia and the World / Indonesia dan Dunia (Jakarta: Gramedia, 1965).

English translations by Max Lane were published by Penguin in the 1990s as This Earth of Mankind; Child of All Nations; Footsteps; and House of Glass.

For a recent overview, see Baskara T. Wardaya, “Cracks in the Wall: Indonesia and Narratives of the 1965 Mass Violence,” in David Webster, ed., Flowers in the Wall: Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia and Melanesia (University of Calgary Press, 2017).

The figure of 100,000 comes from Chega! The Final Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation Timor-Leste. On the history of the occupation, see, among others, James Dunn, East Timor: A Rough Passage to Independence (Double Bay, AU: Longueville, 2004); Geoffrey S. Robinson, “If You Leave Us Here, We Will Die”: How Genocide Was Stopped in East Timor (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); Clinton Fernandes, The Independence of East Timor: Multidimensional Perspectives—Occupation, Resistance and International Political Activism (Eastborne, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2011).

In the “dark affair of 30 September 1965,” a group of junior army officers kidnapped leading generals. The army command under general Suharto struck back and seized power, blaming the abduction on the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and accusing the PKI of carrying out lurid acts on the dead generals at Lubang Buaya, near Jakarta.

Dom Boaventura was a Timorese fighter who resisted Portuguese colonial rule. Nicolau Lobato was the leader of Fretilin, the political party that declared Timorese independence in 1975, until his death in 1978 fighting against Indonesian colonial rule. Indonesia colonized Timor-Leste for 24 years, from 1975 to 1999. Human rights violations during Indonesian rule amounted to crimes against humanity, a subsequent truth commission found. In September 1999, the Timorese voted for independence in a UN-supervised referendum. The garuda is a mythical bird that is the Indonesian national symbol.

Indonesia has a pantheon of “national heroes” (pahlawan nasional) recognized as key figures in its nationalist movement. hey include Diponegoro and Imam Bonjol, who opposed Dutch colonial rule over Indonesia. General Suharto was the leader of the 1965 coup and Indonesian president from 1966 to 1998. Pancasila (the five principles) was Indonesia’s official national ideology.

Wiji Thukul, the “people’s poet,” was “disappeared” after writing a series of anti-regime poems in Indonesia. Munir Said Thalib was a human rights activist and Right Livelihood Award laureate. On board a flight to the Netherlands in 2004 he was poisoned with arsenic. His killer has been linked to Indonesian State Intelligence agents. The land of Cendrawasih (the bird of paradise) refers to West Papua, a former Dutch colony taken over by Indonesia in the 1960s where independence sentiment remains strong and human rights violations remain common. In the Santa Cruz massacre of 12 November 1991 Indonesian soldiers opened fire on Timorese independence protesters, killing some 250 people.

When General Suharto took power in the 1960s, he declared the creation of a “New Order” (Orde Baru) in contrast to what he called the “Old Order” under President Sukarno 1945-65). He governed under the New Order name until 1998, since which time his successors have presided over a new period dubbed “reform” (reformasi).

Lubang Buaya is the “crocodile hole” in Jakarta where G30S members took six generals that they had kidnapped and killed them. Indonesian curriculum on the G30S stressed the suffering of the generals and the alleged dancing by Communist women at the site as being especially horrific. The opening lines of Jendral recall the imagery taught in Indonesian schools.

Student organizing had to be carried out clandestinely under the New Order. As more Timorese students came to universities in Java, they formed clandestine organizations such as Renetil (the National Resistance of Timorese Youth) and others.

Indonesia annexed West Papua in the 1960s (taking over administration in 1963 and formally integrating it in 1969) and has faced a Papuan independence movement ever since.

Pancasila, the five principles, are the Indonesian state ideology. The principles are generally rendered as nationalism, internationalism, social justice, democracy and belief in one God.

Senyap (Silence) is the Indonesian-language release of director Joshua Oppenheimer’s film “The Look of Silence” (2014) about the perpetrators of the 1965-66 killings in Indonesia.