Introduction

One hundred years have passed since the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. It’s surely one of the signal events of the modern era, a project whose significance for humanity is hardly exhausted by its history, including the disastrous, tragic history of Stalinism. A scholarly and curatorial boom in works and exhibits in the centenary reflecting on the impact of the revolution suggests it is not forgotten, even in the former first world, but its legacy remains clouded behind a veil of Cold War hysteria.1 What complicates matters is that the emotions, and even some of the apparatuses, of that half-remembered, misremembered history are being mobilized in the prosecution of the War on Terror.2 It may also be that the mad fury of our present makes us too impatient to open ourselves to the aspirations driving that massive transformation of a society still in the midst of war, its population mostly illiterate, desperately cold and hungry, in the throes of awakening to what was their due as human beings. But it’s precisely because of the misery and dread produced by unbridled neoliberalism and reckless militarism, along with unmistakable signs of ecological devastation that we, in fact, need to learn about a historic effort to pursue a different vision of modernity—one that insisted on universal literacy and health care, gender and racial equality, and the reimagining of society such that it would both enable and express those goals.

|

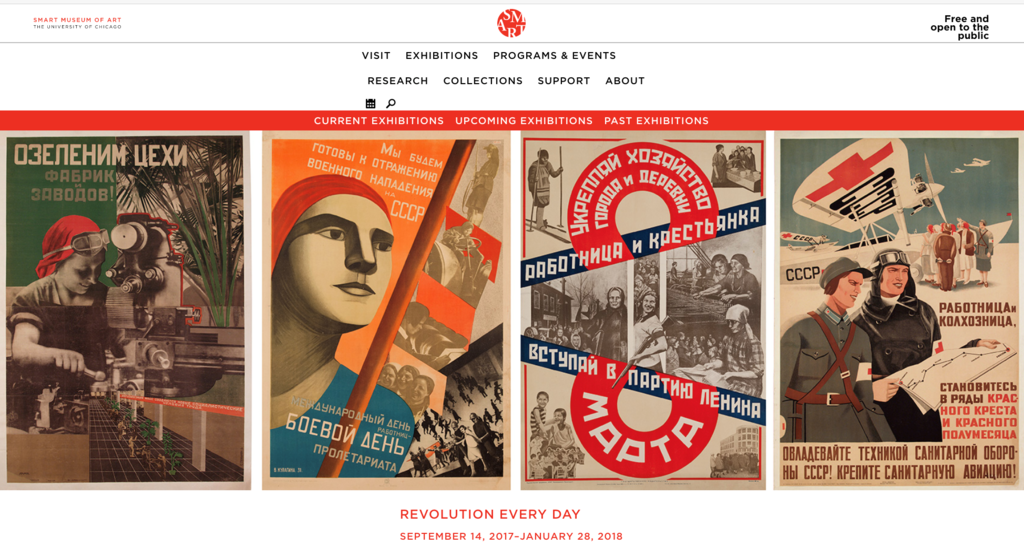

Screenshot of “Revolution Every Day” website, special exhibit at the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, September 14, 2017-January 28, 2018. Left to right): Sergei Sen’kin, Let’s Make the Workshops of Factories and Plants Green! 1931, lithograph on paper (poster), 57 1/2 x 40 1/6 in. (1460 x 1020 mm), Ne boltai! Collection; Valentina Kulagina, International Working Women’s Day Is the Fighting Day of the Proletariat, 1931, lithograph on paper (poster), 39 5/8 x 27 5/8 in. (1100 x 725 mm), Ne boltai! Collection; G. Komarov, The 8th of March: Woman Worker and Peasant, Enlist in Lenin’s Party, ca. 1930, lithograph on paper (poster), 40 1/4 x 27 3/4 in. (1028 x 705 mm), Ne boltai! Collection; Mariia Feliksovna Bri-Bein, Woman Worker and Woman Collective Farmer, Join the Ranks of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, 1934, lithograph on paper, 40 1/8 x 28 in. (1019 x 712 mm), Ne boltai! Collection. |

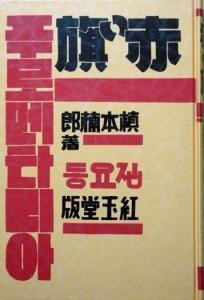

The very fact of the Russian Revolution galvanized working people and intellectuals around the world, even as their governments did their military best to topple the fledgling state. The Japanese government outdid their European and American Allies, leaving a sizable army in Siberia until 1922, two years after the others had withdrawn. From this alone might be gauged the fierceness of the repression directed at the growing numbers of men and women, in cities and the countryside, joining unions, beginning to think of themselves as socialists and even as communists, though parties bearing those names would never become legal in imperial Japan. Inspired by developments in the Soviet Union and seeking ties with comrades the world over, including the Korean colony, Japanese organized furiously, starting up groups for atheists, Esperantists, musicians, filmmakers, artists, daycare activists—all crowned by the term “puroretaria,” meaning that the unpropertied proletariat (also “musansha” in Sino-Japanese) had distinctive and necessary contributions to make. The cultural movement was indispensable to the political movement, and literature was at the heart of the cultural movement. The movement, always subject to ruthless repression, would be shut down by the mid-1930s; its literature would be met with bourgeois condescension in postwar prosperity. But in the short time they had, the young women and men in the movement took on virtually every sphere of society, honing their writing in response to new realities, simultaneously imagining and organizing for a future for which they were prepared to sacrifice a great deal, including imprisonment, torture, and death. It’s the literature produced during this breathtaking “red decade” of 1925-35 that is introduced in our anthology, For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution: An Anthology of Japanese Proletarian Literature, from which the selection that follows, “Art as a Weapon,” is taken.

The representation of reality, proletarian writers theorized, was skewed towards those with privilege who sought at all cost to maintain that privilege. The key essay undergirding their work was Kurahara Korehito’s 1929 “Path to Proletarian Realism,” a remarkable brief history of modern literature, which argued that what was called “literature” was really bourgeois literature, reproducing the individualist moral universe of the bourgeoisie and not of humanity in general. Without discarding the resources accumulated by bourgeois realism, proletarian literature needed to “rebel against the method that dictates that we must always return to ‘individual essence’ when considering social problems, and must emphasize instead one that compels us to strive to consider the societal dimensions of the problems of individuals.”3 It also needed to mobilize the resources of literature in the activity that is its special strength, the instilling of consciousness. This, of course, would require changes in content, methodology, and form.

In our Anthology, “Art as a Weapon” is preceded by chapters titled “The Personal Is the Political,” “Labor and Literature,” “The Question of Realism,” and “Children”; it is followed by two chapters, “Anti-imperialism and Internationalism” and “Repression, Recantation, and Socialist Realism.” In each, several complete works of fiction are followed by critical writings, usually excerpted. We wanted to show women and men, colonized subjects included, tackling scenes and structures crying to be communicated and transformed. Accordingly, well-known writers such as Kobayashi Takiji appear in less familiar roles as critic-theorist and short story writer, as in the selection at hand, but also as the author of the landmark “March 15, 1928,” hitherto available in English only in a disfiguring, truncated translation.4

|

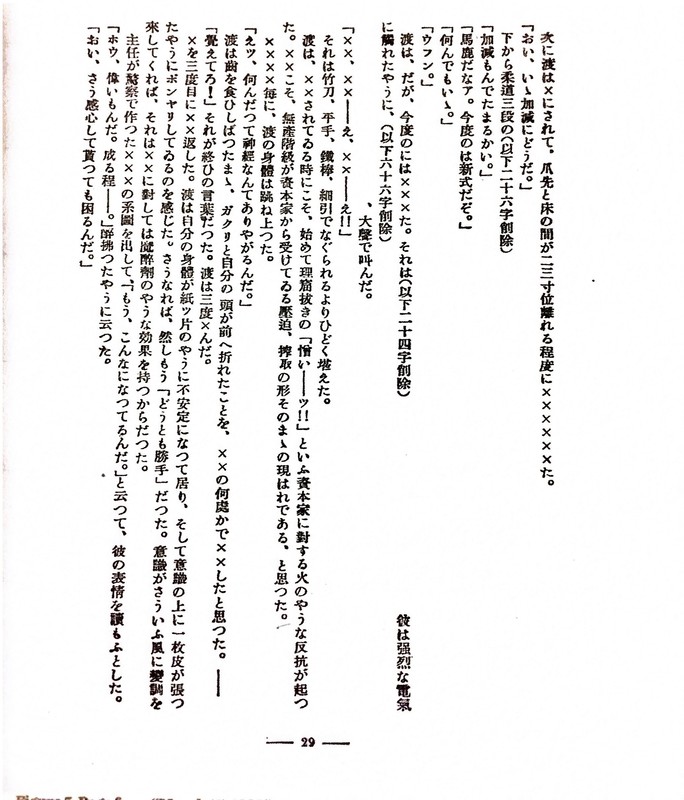

Original publication of Kobayashi Takiji’s “March 15, 1928.” Visible are the x’s meant to obscure and yet suggest objectionable words and phrases. Also visible are the blank spaces 8, 9, and 10 lines from the right, where words have been removed altogether. |

Nakano Shigeharu, whose fame extended well into the postwar era, appears in what may be our most surprising chapter, “Children.” “Tetsu’s Story” is a lively coming-of-age, coming-to-political-consciousness account of the son of desperately poor tenant farmers. The young intellectuals of the proletarian literature movement show us that the children of the industrial and agricultural proletariat, with their early induction into the labor force, had only the barest access to what modern ideology projects as a universal phase called “childhood.” In the case of girls, childhood could be terminated even earlier by sex work. And of course, the threat of sexual predation accompanied girls on their way to womanhood on the factory floor, as traced in a remarkable short story by Matsuda Tokiko, whose work appears in English for the first time. “Another Battlefront” (included in the chapter “Anti-imperialism and Internationalism”) depicts the impact of impending war on the workplace through the viewpoint of a young woman. The familiar oppressions of speedups and sexual harassment are exacerbated by chemical hazards entailed in the production of rubber (essential to waging war) and intensified surveillance, which the protagonist and her comrades contest by cultivating habits of solidarity, including support for soldiers needlessly exposed to the suffering endemic to imperialist adventurism.

“Art as a Weapon” showcases some of the pioneering efforts of, for the most part, intellectual writers, addressing the issue of form and content, vigorously debated in modernist aesthetic circles. Even as their work appealed to a considerable bourgeois readership—it was experimental and thoroughly modern—the proletarian writers understood that they had to learn to write for overworked and undereducated people with little time and no change to spare. They had to avoid the pitfall of “crappy old sermons ordering people to ‘do this and do that!’” and instead produce “the sort of work that hits you smack where it counts.”5 (For more on this issue, see the essay by Kobayashi Takiji in this selection.) In this practice, they were building on a half-dozen years of debate and had the benefit of models invented and developed elsewhere, such as the “wall story,” featured in this selection. (The only work in our Anthology not originally written in Japanese is a Korean “wall story” that reads like an origin tale of the genre.) They wanted new writers as well as new readers, and formed writers’ circles to encourage work from people who had never imagined themselves as writers of any sort. We have included in this selection, for example, a work of reportage published by a factory woman. As you can see in the images provided below, it was dignified with its own illustration like the works of core members of the movement and paired with a critique by a senior member. Literary Gazette, although frequently banned, took the cultivation of worker-farmer writers seriously.

Today, on both sides of the Pacific—indeed, around the world—we are pressed to be fearful of certain others and promised prosperity through the expanded privatization of social goods. Over the past year, especially in the U.S., we’ve been inundated by reports of horrific injustice, exacerbated by environmental catastrophe, delivered along with fresh batches of fake news designed to divide the many who suffer from job, housing, and health precarity; addiction; sexual harassment; domestic violence; educational inequality; the ever-present menace of guns and now, once again, nuclear war. All this, combined with grotesque concentration of wealth, as if in mocking testament to the dictum, “The opposite of poverty is not wealth—it is justice.”6

The writers in our Anthology were working in what they understood to be a pre-revolutionary society, replete with the harsh features of rapidly advancing capitalism. They had the historic luxury of believing, in the face of overwhelming repression, that a just society was in the making. They didn’t think literature alone would get them there, so they gave unstintingly to various activities, but literature was what they loved. So they embraced that grand instrument of modernity as a tool for grasping reality, for themselves and for hitherto excluded others, and then for imagining and creating a more just future.

We know their hopes were crushed, the fruits of their labor buried under mounting reaction and the devastation of war. We know that with the end of the war, their phoenix had a rebirth; that its flight was constrained by the revival of reactionary forces under the US Occupation and then by the security treaty regime; that its colors were dulled in the depoliticization accompanying a prosperity whose defining quality was access to consumer goods; that finally, it would be recalled, occasionally, with condescension.

But what can such dismissal of a past struggle, of this past struggle, yield us?

A 1999 video of a young Albanian’s interview with his mother provides a parable of sorts in response.7 Anri Sala, while studying film in Paris, comes upon an old reel of his mother as a young Communist militant. He shows it to his mother, Valdet, who is disappointed that the soundtrack is missing. Tracking down those who might know either how to retrieve the tape or remember the words uttered only elicits painful dismissals of the revolution itself. Finally, Anri has the inspired idea of going to a school for the hearing impaired in Tirana, where he manages to produce subtitles as his vibrantly youthful mother’s lips are read. But a shocked Valdet vehemently denies that she could have mouthed such “gibberish”—imperialism, people’s revolutionary movement, two powers, the Marxist-Leninist Party—twenty years earlier. But as she reads her own lips while listening to her son read the subtitles, she comes to acknowledge that disavowed self. Tears glistening in her eyes, she slowly allows that she had been then, and still was, a person who worked “So that society could be more social-minded … more attentive to the individual … more humane.”

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stills from the film “Intervista” (Finding the Words), screened during the “Revolution Every Day” exhibit at the Smart Museum. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Post-Soviet Albania had been wracked by pyramid schemes and just undergone a civil war. Fear and confusion beset her. She cannot see a way through it. And yet. What else is there to affirm, to seek, now as then? So it is in that spirit that we invite you, our readers, to turn to these works by young Japanese writers of nearly a century ago who observed and dignified neglected lives, and under daunting, even terrifying circumstances, exhorted themselves and others to work toward that elusive and self-evident goal: a “social-minded” society.

Note: For reasons of length and copyright, the excerpt below omits the poem “Leafleting” by Sata Ineko; “Shawl” by Tokunaga Sunao; “Our Own Literature Course [1] A Guide to Writing Literary Reportage” by Yamada Seizaburō; “A Guide to Fiction Writing: How to Write Stories” by Kobayashi Takiji; and “The Achievements of the Creative Writing Movement: An Assessment of Works to Date” by Tokunaga Sunao.

In our Anthology, we indicate passages that were suppressed at first publication with marks such as “x” and “o” or ellipses, the record of preemptive censorship by editors and authors to avoid costly banning. These marks coincided with the practice of using initials or x’s instead of proper nouns as well as unvoiced thought, all part and parcel of the orthography of Japanese modern literature. Modern literature has yet to adequately deal with this practice in translation. A few examples appear in this selection.

Art as a Weapon in Japanese Proletarian Literature8

Heather Bowen-Struyk and Norma Field

Keywords: Bolshevik Revolution, proletarian, modernism, Kobayashi Takiji, Kuroshima Denji, Kurahara Korehito, Yi Tong-gyu, female factory workers, “wall stories,” workers literature, peasant literature, children, labor organizing, anti-war, imperialism 小林多喜二, プロレタリア文学

In the poem by Sata Ineko [8, 15, 21]9 that opens this chapter, the speaker is poised in the moment before she deploys “art as a weapon”—in this case, an agitational leaflet. Art as a vehicle of protest may be as old as art itself. The rhetoric of art as a weapon, part and parcel of the language of class struggle and revolution, could be considered an instance of this venerable practice, but this twentieth-century usage, which aggressively challenged the principle of “art for art’s sake,” never failed to exercise bourgeois critics and writers of the “aesthetic school” (see [22, 29]) in Japan and elsewhere. They were inclined to declare art with a purpose, especially a political purpose, not to be art at all, or at best, an inherently inferior art. But the relationship of art and politics stirred heated debate within the proletarian literature movement itself.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LEFT:Leaflet for the 1930 Tōyō Muslin Dispute: Across the top: “Arm yourselves and attack!” Center stripe: “Don’t let the 3000 female factory workers from Yōmosu die without your help!” Source. RIGHT: Writers organized lecture events and went on speaking tours to support their movement organs, not just by publicizing them but by fundraising. This photo is from January 1931 at Tennōji Public Auditorium, Osaka. Front row from left: Takeda Rintarō, Tokunaga Sunao [23, 31], Sata Ineko [8, 15, 21], Miyamoto Yuriko [36, 40]. Back row from left: Tanabe Kōichirō, Kuroshima Denji [26, 34], Hasegawa Susumu. Ōmori Sueko, ed. Yuriko kagayaite (Shinnihon Shuppansha, 1999): 24. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The major debates of that movement—on the popularization of art, on form and content, and on the relationship of artistic value to political value—are all pertinent to the short forms included in this chapter. Can the aesthetically valuable be melded with the politically valuable? Which is more important, form or content? Or are they an inseparable whole, in which artistic and political values merge in the cause of the proletariat? What kind of writing would best reach the various levels of that proletariat, from the highly literate printer to the virtually illiterate day laborer or tenant farmer? These debates were intensely intellectual, but the stakes were high precisely because the participants were agreed that they wanted to contribute to the actual transformation of society and not just score points with one another. Of the three categories of debate, popularization had the most practical urgency: how were the intellectuals who dominated the movement to create work appealing to industrial workers and tenant farmers? The first round of popularization debates took place in mid-1928, with Kurahara Korehito [13], Hayashi Fusao [7], Kaji Wataru [16], and Nakano Shigeharu [19] as key participants. Arguments ranged from whether it was desirable to distinguish between agitprop for the masses and genuine proletarian art; whether proletarian art could even be produced in a pre-revolutionary society; or whether mass entertainment inevitably transmitted its ideology along with its forms and was therefore useless, if not harmful, for the goals of the movement.

The creation of an expanded umbrella organization (KOPF, for Federacio de Proletaj Kultur Organizoj Japanaj) in late 1931 came with the directive to locate the foundations of the cultural movement in the literature circles “at the factories, at the farms.” With this initiative came the promotion of new forms such as the “wall story,” “correspondence,” and “reportage” by industrial and agricultural workers. Kobayashi Takiji’s “On Wall Stories and ‘Short’ Short Stories” ([29]; see also [1, 5, 11, 22, 30]) suggests that this version of the genre—with possible antecedents ranging from premodern forms to the European contes to “aesthetic school” champion Kawabata Yasunari’s “palm-of-the-hand” stories10—developed in response to workers’ desires for fiction commensurate with their needs, given lack of time and disposable income as well as preparation for reading lengthy works. Takiji’s essay is an important statement of what unity of form and content meant for proletarian writers. At the same time, we need to acknowledge that even though the accessible placement of the “wall story”—in public places such as factory walls—was key to the genre, it’s unclear whether Japanese writers and readers were able to use it in this way: the extant compositions, including those given here, were all published in journals. Whether they were ever ripped out and pinned up, as described in the Korean example [24] is unknown. Kurumisawa Ken argues that the point of envisioning where the stories might be placed was to prompt writers (and illustrators and printers) to create their stories with a concrete sense of the readers who would gather there, with the story itself coming to life from that interaction.11 Kamei Hideo, reflecting on Takiji’s “Letter” [22], probably the best-known example of the genre, suggests that if these stories had been made conspicuous on a wall—a medium not, legally speaking, belonging to the workers but claimed as their site of expression—that in itself could have served as a spark for struggle.12 At any rate, selections 22 through 26 suggest the range of the “wall story.”

The international, especially German, inspiration for these forms is attested by a far more extensive treatment of “wall fiction” written for a Japanese readership by Otto Biha, editor of the Left Turn (Die Linkskurve), the organ of the Association of Proletarian-Revolutionary Writers. Biha’s essay on “Burgeoning Forms of Proletarian Literature in Germany” appeared in Japan as part of a five-volume series edited by Akita Ujaku (1883–1962) and Eguchi Kan (1887–1975), General Course in Proletarian Arts, an extraordinary collection of theoretical analysis, historical reflection (on such a young movement!), and guides spanning the range of proletarian arts—visual, theatrical, cinematic, and literary—primarily in Japan, but also in Germany, the Soviet Union, and the United States. Takiji’s “Guide to Writing Fiction” appeared in the second volume of the General Course, following Tokunaga Sunao’s guide in the inaugural volume. Much of the advice is likely to strike the reader as sensible for any young, or for that matter, seasoned fiction writer. Together with Tokunaga’s “The Achievements of the Creative Writing Movement” [31], a retrospective assessment identifying areas for improvement, these reflections demonstrate the proletarian writers’ care for their craft and, in so doing, prompt us to reexamine the significant and superficial distinctions between proletarian and bourgeois literature.

Together with the essays from Takiji and Tokunaga in this chapter, Yamada’s “A Guide to Writing Literary Reportage” [28] illustrates the movement’s efforts to recruit not only new readers, but also writers who were workers and tenant farmers by day. Yamada encourages them to try their hand at correspondence or literary reportage, a genre also discussed in Otto Biha’s “Burgeoning Forms.” When the literary wing of the movement was reorganized as one among many units (music, art, film, etc.) under the umbrella of KOPF in late 1931, “circles” were organized in factories and farm communities.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LEFT: “Activities of the Culture Circle,” cover of NAPF (November 1931), organ of KOPF (Federacio de Proletaj Kultur Organizoj Japanaj); design by Ōtsuki Genji (1904-1971). Black and white version. RIGHT: Poster for the Defense of Senki (Battle Flag) Lecture Meeting. Speakers include Kobayashi Takiji [1, 5, 11, 22, 29, 30], Tokunaga Sunao [23, 31], Kataoka Teppei [12], Ōya Sōichi, Nakano Shigeharu [19], Kishi Yamaji, and others. May 19, 1930. Admission: 30 sen. Workers: 20 sen. Source. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The impetus was a call from the Fifth Congress of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profintern) in 1930. If workers were to be exhorted to put their experiences into writing, their effort needed to be acknowledged through publication. The Literary Gazette was one such site, carrying international and domestic news, reports of various circles, articles by major figures (Takiji, Tokunaga, Miyamoto Yuriko [36, 40], Nakano, etc.), but also a page for readers’ prose and poetry, sometimes with prizes and evaluation. Every page had photographs, and original illustrations were as likely to accompany submissions by readers as well as by movement leaders. “A Day at the Factory” [27] is the only piece in this anthology by a writer about whom we know nothing beyond what appears here. It is paired with Yamada Seizaburō’s how-to piece [28], which includes a criticism of her composition. His discussion helpfully illustrates the political imperatives underlying promotion of the reportage form. However we assess his framework, as well as the appropriateness of his specific criticisms, we acknowledge the serious commitment the leaders of the proletarian literature movement made to encourage men and women who had never imagined themselves as writers to take up pen and paper.

That so much writing, organizing, teaching, and editing persisted at this time is remarkable. Not only were key leaders arrested and imprisoned beginning in April of 1932, but of the thirty-three issues of the Literary Gazette published between October 1931 and August 1933, one was confiscated in its entirety and twenty-four were banned. With the tenacity of the forbidden, they still found their way to readers. (Norma Field)

[(21) Leafletting omitted]

(22) Letter

KOBAYASHI TAKIJI

Translated from Central Review (Chūō kōron, August 1931)13

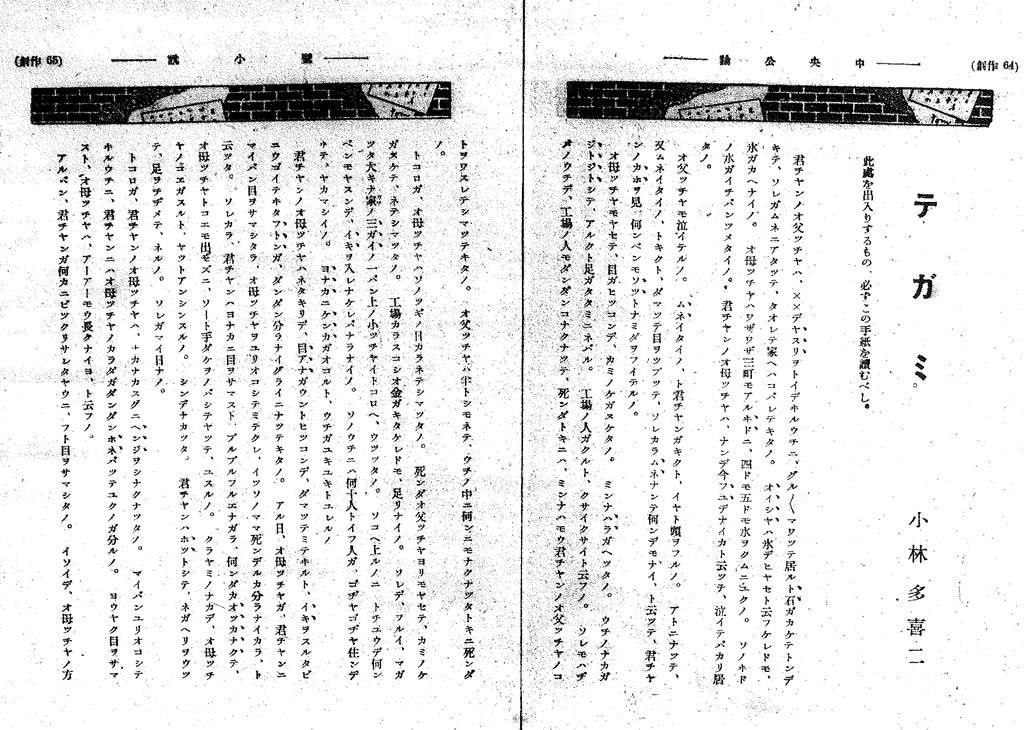

The best known of all “wall stories,” “Letter,” written in the script children first learn, was published as one of six examples of the genre in the very mainstream Central Review. At the time of its publication, 1968 Nobel laureate Kawabata Yasunari singled out “Letter” for praise: in contrast to the insensitivity to language displayed in the other five selections, he observes, there wasn’t a single needless word in “Letter”; nor, at the same time, was there anything exceptional that called attention to itself.14 Intriguingly, this is not the only instance of Takiji, iconic proletarian writer, receiving praise from Kawabata, champion of the “aesthetic school” fiercely critical of the proletarians.15

Kawabata’s praise, though, invariably refers to Takiji’s writing and avoids the content of his fiction. For Takiji [1, 5, 11, 29, 30], the literary and political demands of writing implicated each other, just as form and content were inseparable. As we’ve seen in “Comrade Taguchi’s Sorrow” [1], he was interested in the experiences of proletarian children and experimented with their portrayal. A tireless letter writer himself, he seemed to find the epistolary form especially conducive to presenting their voices. Even more, Kurumisawa Ken argues, the choice of the form reflects Takiji’s grasp of the essence of the genre, for what is a letter that doesn’t anticipate a response? Had this story-letter been posted near the factory gate (“this place”) where the events described could easily be imagined as taking place, the worker-readers could begin arguing about whether the father needed to die, whether his family needed to starve, what more could have been done—all the while comparing the fictional circumstances with their own reality.16 (Norma Field)

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LEFT: First publication of “Letter” by Kobayashi Takiji. The script is mostly katakana, suggestive of a child’s writing.

RIGHT: Kobayashi Takiji. Source. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Attention: All persons passing this place are to read this letter.

Kimi-chan’s papa? He was sharpening a file at the XX, when a piece of the spinning stone broke off and hit him in the tummy. He fell down onto the floor, and they carried him piggyback all the way back home. Doc said to keep his wound cool with ice, but they didn’t have no money for that. That’s why Kimi-chan’s mama walked three big blocks to fetch cold water from a well. She musta headed out there four or five times, ’cause the reason for that is the water over there is coldest of all. Her mama kept on crying and crying and saying, Oh, why ain’t it winter no more?

Her papa was crying too. And when Kimi-chan asked, It hurt Papa? he just shook his head. No, it don’t. And when she asked him later, It hurt Papa? he closed his eyes without saying nothing, and then he told her, Papa’s chest don’t hurt him at all. He looked up at Kimi-chan’s face, and whenever she wasn’t watching, he wiped away his tears.

Kimi-chan’s mama was thin, too, and her eyes were all dark and hollow, even her hair was falling out. And I’d say all of ’em was practically starving. It was so damp inside that house of theirs that the floor was all sticky when your feet touched it. And whenever they came by from the factory? To check on him, you know? You could always hear ’em saying, Pew, it stinks in here! But that was just at first, ’cause soon enough they just stopped coming by at all. By the time Kimi-chan’s papa died, just about everyone forgot about the whole lot of ’em. Kimi-chan’s papa went beddy-bye for six months long, and just as soon as they ran out of things to sell, he went and died.

But the day after that Kimi-chan’s mama went beddy-bye too. And she was even more skinny than Kimi-chan’s dead papa, and had less hair than he did. And that’s the reason why she had to go beddy-bye. They still had a bit of money from the factory leftover, but it wasn’t near enough, and that’s why they moved into that tiny room—up on the third floor of that old building about ready to fall down. With that steep staircase and all you gotta rest a couple times on the way up just to catch your breath, you know. And there’s dozens of people crammed up inside there making all kinds of scary noise. Sometimes people get into fights in the middle of the night and you can feel the whole building wobbling side to side.

So there was Kimi-chan’s mama lying in bed, with her eyes looking dark and hollow, and not saying nothing at all. And you know how when you breathe, you can see your blankets moving up and down? Well, it was almost like her blankets didn’t move up and down no more. . . . And then one day her mama tells Kimi-chan to shake her whenever she wakes up at night, ’cause you never know, she said, I might just be laying here dead as a dog. Later that night Kimi-chan opens her eyes, and she was all shaking and scared. She didn’t try saying nothing to her mama, but just stuck out her hand to give her a poke. It was only when she heard her mama answer in the dark that Kimi-chan stopped worrying no more. She ain’t dead yet! said Kimi-chan, breathing a sigh of relief, and turning onto her side. She curled herself up into a ball and went back to sleep again. The same thing happened to Kimi-chan just about every single night.

But after a while, you know, Kimi-chan’s mama? She didn’t answer Kimi-chan so fast no more. And whenever Kimi-chan tried to wake her up, she could tell her mama was turning skin and bones. And then one time? When her mama opened up her eyes? She done whisper to Kimi-chan, It ain’t gonna be long now. . . .

A couple nights later something woke up Kimi-chan. She stuck out her hand to find her mama, ’cause she was too scared to talk out loud in the dark. But when she shook her mama? She didn’t wake up. And then, after a while? Kimi-chan starts shaking her mama harder and harder. And she starts yelling out loud, Oh, Mama, Mama! She could hear her own voice echoing in that dark room of theirs. But her mama? Her mama didn’t move at all.

All of a sudden Kimi-chan screamed out loud. She jumped to her feet and tried to run outside. But she tripped on the way out and fell all the way down that steep set of stairs. And what a racket that made, being the middle of the night and all. But Kimi-chan’s mama? Sure enough, she was dead as a dog.

The only ones left now are Kimi-chan, her baby brother, and her kid sister. And after falling down them stairs like that, Kimi-chan got bruised up enough to end up in bed. That’s why all the people living in the same building as them got together to hold a funeral for Kimi-chan’s mama. Everyone in that building’s so darn poor they figured best stick together to help one another out.

But on the night of the wake, after everyone fell asleep? That’s when someone woke up and saw all the food on the altar done disappeared. And let me tell you, what a stir that caused! It wasn’t no cat or dog that’d eaten that food neither. Who coulda done it? we was all thinking.

I was at the wake too. And when I happened to walk into the room next door, the room where Kimi-chan and them was sleeping, well, I near got the shock of my life and froze up on the spot. They’s just kids, I know, but there was Kimi-chan, her baby brother, and her kid sister gobbling down all the food we’d brought for their dead mama. And ’cause I wasn’t thinking straight, I done scream out loud. All the others then came running into the room shouting, What’s the matter, what’s the matter? Those three kids sitting there, gobbling up all that food like that. Well, to me, they seemed like goblins or something with them lips of theirs hanging open wide.

They all asked Kimi-chan, What d’you think you’re doing, girl? But Kimi-chan? She just turned white as a sheet and didn’t say nothing at all. Then all of a sudden she starts crying. Tears are rolling down her cheeks, and she says ever since their mama died four or five days beforehand they didn’t have no food left to eat. They was so hungry their heads was spinning, and they got the pains in their chest, and they been lying down on the floor half dead all day long. And since they didn’t have no food to eat for so long, there wasn’t nothing gonna stop their eyes from popping out of their heads when they saw the offerings set out for the funeral. Kimi-chan wasn’t doing right by her dead mama, and she knew it, but with her kid brother and sister being so small and all, she just waited for when no one was looking, and then let them eat as much as they wanted.

There wasn’t a soul in the tenement not crying after hearing Kimi-chan tell her story.

Kimi-chan won’t be around for much longer. But even still she sometimes tells me things like this: Why is it that all XXXX people like us have our papas die, and then have our mamas die, and then end up dying too? Well, when I get better, Kimi-chan says, I’m gonna become a XXXXXXXXX and go out marching with a XX in my X.17

Translated by Samuel Perry

[(23) Shawl omitted]

(24) The Bulletin Board and the Wall Story

YI TONG-GYU

Translated from Group (Chiptan, February 1932)18

As with many Korean figures of the Japanese colonial period and the early postliberation years, the basic facts of Yi Tong-gyu’s life are subject to speculation. He was born in Seoul, perhaps in 1911 or 1913.19 He was working as a reporter for the journal New Youth (Sinsonyŏn) when he joined KAPF (Korea Artista Proletaria Federacio), of which he would remain a member until its dissolution in 1935. Caught in the mass arrests of 1934, Yi was imprisoned until 1936. After liberation, in 1946, he became chief editor of People’s Korea (Minju Chosŏn), the official newspaper of the North Korean People’s Committee, but he died sometime during the Korean War.

In December of 1931—the same year when “wall stories” began to appear in Japan—Yi published “The Mute” (Pŏngŏri), perhaps the first piece to be labeled a “wall story” in Korea.20 We are lucky to have “The Bulletin Board and the Wall Story,” for it appeared in the only issue of the journal Group (Chiptan) currently known to have survived censorship and other historical vicissitudes. This is the only piece in this anthology not originally written in Japanese. (As other selections [33, 39] show, some Koreans in the proletarian movement, whether in Japan or colonized Korea, also wrote in Japanese.) Although intensifying crackdowns had weakened the ties between the Japanese and Korean movements by the time this story was published, it presents an ideal origin narrative of the wall story, as plausible in Japan as in Korea. For more proletarian stories translated from Korean, see the anthology edited by Hughes, Kim, Lee, and Lee, Rat Fire.21 (Norma Field)

Like the setup in any old shack put up to serve red bean porridge, the factory cafeteria was laid out with rows of long pine boards, nailed to makeshift legs, except that today, hanging on one of the walls, there appeared a gleaming, newly lacquered bulletin board. What the heck is that for? wondered the puzzled factory workers.

The next day, coming inside to eat their lunches, they found a white piece of paper posted on the bulletin board, a piece of paper covered with neatly penned letters. Their curiosity sufficiently piqued, they gathered round. “What is it, an advertisement?” shouted Sŏngdong, the short one standing behind the rest. “Advertisement? This ain’t no advertisement,” replied one of the men standing in front, all of whom now proceeded to read it out loud.

“Lessons in Character Building. Part One: Diligence. It has long been said that the hardworking man is the successful man, therefore all men should be hardworking. In order to build his personhood and then to establish his household, it not only behooves a man to approach all his tasks with the utmost of sincerity but also . . .”

The men sounded out each word deliberately, as though they were reading from a storybook out loud.

No sooner had the lunchtime siren started ringing than Insŏng ran quickly toward the cafeteria, opened up his lunch box, and started chomping on a rice ball. And as he sat there now, lunch in hand, he too glanced over at the bulletin board: “What do we need that kind of lecture for?”

“Hey, let me see too!” said Sŏndong, muscling his way to the front of the crowd.

“What do you need to look at that for?” chimed in Yunsik, the prankster, blocking Sŏngdong’s view.

Sprawled out on a bench as he ate his lunch, Taesŏk offered his two cents as well:

“What do ya think they’re up to, posting something like that up here?”

“Something stupid, that’s what.” Good old highpockets, Sŏngbok, had finally chimed in. “‘Stop goofing off and work harder’ is all they want to say.”

“Man, that ain’t the half of it. I bet when they announce more layoffs or lower wages, they’re just gonna post a notice up here, so they don’t have to tell us face-to-face.”

From that day forward the office posted a new Lesson in Character Building every day, which basically said something along the lines of “work hard” or “be loyal.” About once a week a factory supervisor or one of the office employees would come to read out loud the writing as though they were delivering some sort of lecture. But not a single one of the workers attempted to read these notices any longer, or even give them a second glance. Three or four months beforehand there might have been one or two men who would have read them with sincerity. But since then a strike had broken out to demand better treatment from their bosses and to protest the reduction in wages that had so shocked the world. After this, things finally sank in and the workers were no longer the fools they once had been—not a soul among them now had time for this sort of garbage. After all, the only reason this cafeteria had been constructed in the first place was that they had demanded it in the last strike.

Sometime afterward a theory of sorts circulated among the workers: “It is with great regret that this bulletin board, supposedly for our benefit, has offered us nothing whatsoever. So let us make this bulletin board something beneficial to ourselves!” This is why they all decided to take turns writing down something and posting it on the wall for everybody to read together. Each day something new was posted right on top of the piece of paper drawn up and posted by the office. They posted newspaper articles as well (especially articles about strikes) and even good pieces of writing they had torn out of magazines. Later on they posted wall stories they took from journals, which brought about the best results. Reading them while they ate lunch became a daily routine, one they found thoroughly enjoyable. Of course the office knew nothing about what was going on.

Then one day during lunchtime their supervisor walked into the cafeteria, cool as a cucumber, with that big smile of his plastered on his face. He was there to read to them what was written on the bulletin board. On the bulletin board, however, had been posted a sheet of white paper with a wall story on it called “The Workers Committee” by Mr. XYZ. Mistaking it for something the office had actually posted, the supervisor began reading the story out loud.

“Ahem! ‘They gathered together with great excitement. For an event of the utmost gravity was about to play out before their very eyes. . . .’”

After he read a few lines, the color suddenly drained from the super’s face.

“Wait a minute, just what is this . . . ?”

The man was all eyeballs as he read the remainder of the story to himself. The workers watching him now could hardly help bursting out into wails of laughter, which they had only managed to hold back for a few seconds.

“Aha, ha, ha!”

“Whoopee!”

Without speaking a single word—his face indeed spoke what was on his mind—the super lifted the heavy bulletin board off the wall, propped it onto his shoulder, and then headed straight toward the office. Behind him followed a stream of uproarious laughter that shook the entire cafeteria.

By the following day the bulletin board had disappeared for good. But by then the workers had all understood the need for more wall stories, and having become quite accustomed to reading them, they were determined to start them up again. From now on they would use the doors of the cafeteria just as they had the bulletin board, and whenever they found wall stories in magazines, they would post them on the doors and read them with enthusiasm every day.

Translated by Samuel Perry from the Korean

(25) A Farmer among Farmers

HOSONO KŌJIRŌ

Translated from Proletarian Literature (Puroretaria bungaku, February 1932)22

Hosono Kōjirō (1901–1977) was born in Gifu Prefecture but moved to Hokkaido in his youth. There, as a farm worker, he gained intimate knowledge of the bleak conditions of tenant farming in northern lands as depicted in this selection. While holding a string of jobs including reporting—a feature shared with many proletarian writers—he became active in the movement, maintaining his commitment through its decline and resuming his activities after the war.23

The proletarian literature movement, like the larger political units of the movement, regularly coupled “farmers” with “workers.” But the materials it drew on were much more likely to reflect urban industrial life, despite the fact that the boundary between city and country was increasingly blurred, with tenant farmers finding it difficult to support themselves with farm work alone. Besides “Tetsu’s Story” [19], “A Farmer among Farmers” is the only selection in this anthology with a rural setting. Farmers were ostensibly harder to organize because they didn’t have a shared workplace to foster solidarity; nor were they likely to have a bulletin board for posting this kind of story. The depiction of encroaching war in this story, however, brings it in dialogue with other pieces [26, 32, 34] revealing subtle and explicit resistance to Japan’s imperialist ventures. (Norma Field)

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LEFT: The fifth meeting of the National Farmers Union. March 20 and 21,1932, Tokyo. “We resolutely oppose high sharecropping fees, land confiscation, high-interest loans, and heavy taxes! Defeat the exploitation by landlords and capitalists and the war of oppression! Join the National Farmers Union— it fights for farmers’ livelihood! String the ropes of National Farmers Union members in every village! Destroy the Zenkoku Kaigi Faction’s split movement!! Help the masses’ National Farmers Union advance forward!! 1932. Source. RIGHT: Lecture on Farmers’ Problems, sponsored by Japan Farmers’ Union; poster design by Yanase Masamu (1900-1945), 1920s. Source. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

He stooped down beneath the eaves and tossed off the reed mat that was folded over his back. In his haste, however, the snow clinging to an old straw mat, hung over a crack in the wall, was knocked down onto the nape of his neck.

“Oh, cripes, that’s cold,” said the old man, jerking his head to the side and shaking off the snow. A copy of the Farmers Union Newsletter he’d just been given fell flat on the ground in front of him. He picked it up off the floor and stood up again, noticing as he did so that visitors had arrived, and then hearing people talking softly inside. Now, who could that be? the old man wondered for an instant, his mouth watering as he opened the muddied neck of his straw sack. Inside the sack were bracken roots still freshly covered in soil, by now so bone-chillingly cold they were practically frozen to a crisp. The old man lifted his shivering hands up to his mouth and blew on them repeatedly. Each time he did so there came a grumbling sound from the depths of his stomach. It had been empty for a very long time.

Twilight was setting in and the powdery snow that had begun to fall since noontime had already spread out a blanket of white in all four directions. Winter had arrived. In the paddies on either side of the road stood the rotting stubs of last year’s rice plants, with what looked like tiny withered beards of grain stuck here and there. The apple orchards and mulberry fields were engulfed in a gray haze that extended far into the distance—dusk was settling over this hamlet, which now looked like a desolate heath. Plagued by poor harvests and widespread famine, this cold and barren northern village hadn’t a hearth still burning, and would soon be abandoned into the depths of the snow.

Soaked to the skin and chilled to the bone, the old man managed to stumble into his house on legs numbed of all sensation. The visitors were the village head and a man from the town hall. The village head shifted his gaze toward the black bracken roots stacked up on the earthen floor.

“Still workin’ hard though it’s gettin’ to be winter, eh?” he said with a smile.

“It’s gotta be tough now that you’re older. How about it, heard from your boy recently?”

By “your boy” the visitor was referring to his son, who’d been taken off24 to the Mongolian-Manchurian front line. Had something happened? wondered the old man, his face twisting into an expression that betrayed his bewilderment.

“They say a journalist’s coming by to visit. So—” chimed in his wife from beside the hearth.

“A what?”

“Well, actually—” began the village head, launching himself into the following explanation.

A journalist from a newspaper in Tokyo was making his rounds in the area, visiting the families of soldiers drafted to the front from places hit hard by poor harvests, and it appeared that he might stop by this hamlet sometime tomorrow. If the journalist did come, they wanted to make sure the old man would not complain about how hard it was to feed himself, and instead focus on how his son was devoting himself to the good of the nation.

“You know, it’ll be an honor for the whole village if we get taken up in the papers,” said the man from the town hall, conspicuously slipping something wrapped in paper toward the doorframe. As he did so, a malnourished child with sunken eyes, who sat beside the hearth, flashed his eyes greedily in its direction.

“So that’s what this is all about—you gotta be kidding me.” The old man glanced to the side of him. “Me, I don’t do business that way!”

“Well, it’s not meant to be—I mean, you’re a loyal citizen of Japan, aren’t you?”

“Look here, mister, I don’t know how all you gents with storehouses full of rice do things, but poor folk like me? Who’ve got to feed themselves by digging up wild roots outta the snow—? Well, I say to hell with you and all your smooth talking—and your goddamned country as well!”

“Pa, how could you—” shouted his wife, stern-faced, from beside him.

“Oh, shut up, woman!” he replied. Shifting his glance toward the village head and his lackey, he added something more menacing:

“We’re already at our wit’s end! All you gents with full storehouses best be careful, you hear?”

Sour-faced, the visitors then took their leave. Through the crack in the door the powdery snow blew its way into the dark, earthen-floored room with each gust of the wind.

“I’m starving, goddamnit,” the old man said angrily, as he stepped up to the hearth and sat in front of his “dinner” tray.

“‘A gesture of the government’s sympathy’—Hell, they’ll say any god-damn thing they want to get what they’re after. And all to pull the damn wool over our eyes! Crafty old bastards, the whole lot of ’em.”

His lips already pursed, the man blew into his steaming bowl. The broth made a bubbling sound as it was forced into small ripples that ran to the opposite side. The barnyard millet, almost grayish in color, rose up to this side of the bowl as though it were sand in the surf. It was just then that the words from the newsletter he’d placed in his breast pocket surfaced in the old man’s mind:

Don’t be fooled by the “sympathy” of the capitalist landlords! Let us join arms and rise up!

Translated by Samuel Perry

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LEFT: Senki cover showing a Chinese peasant and Japanese peasant working together, October 1929; cover announces that August and September issues were banned. Design by Ōtsuki Genji (1904-1971). CENTER: January 15-21, 192?: Anti-Militarism Week. Oppose the Burden of Militarism that Sacrifices the Youth! The All-Japan Proletarian Youth League. Design by Yanase Masamu (1900-1945). Source. RIGHT: September 19-24, 1927: Declaration Opposing the Invasion of Manchuria and Mongolia Week. Poster depicts the outstretched hands of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Russian workers all threatened by a man with a sword. Design by Yanase Masamu. Source. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(26) “To Qiqihar”

KUROSHIMA DENJI

Translated from Literary Gazette (Bungaku shimbun, February 1932)25

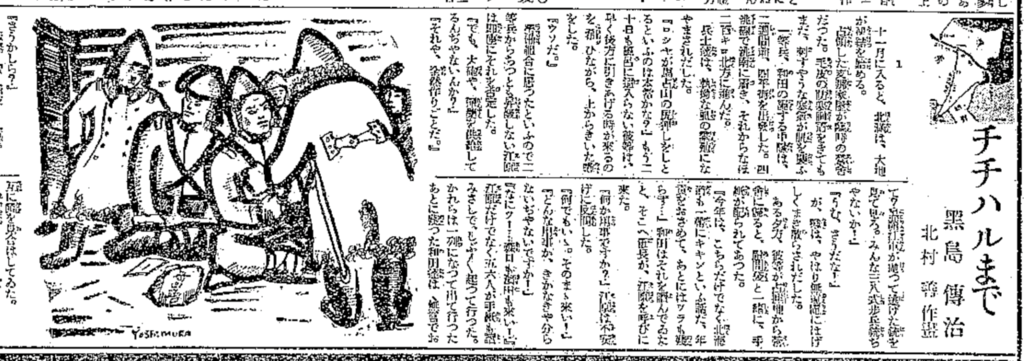

As evident from his biography (see the introduction to [34]), Kuroshima Denji was a tireless proletarian critic of war. Following the Manchurian Incident of September 1931, in which the Japanese military staged a pretext for expansion into northeast China, stepped-up mobilization prompted communists to combine antimilitarist and labor issues in their factory organizing. With great courage, they attempted to do the same in the military. As this story shows, the correspondingly wary authorities did not hesitate to act swiftly on their suspicions.26 With a handful of details, Kuroshima manages to sketch the shift of control over terrain among the Japanese and Soviet armies, Chinese warlords, and resistance forces. Zooming in on the campaign to take Qiqihar, which would become an important base throughout the war in northeastern China, he fashions a narrative of Japanese resistance to the imperialist war. Given the eagerness of the authorities to stamp out antiwar activity in the military, it is curious to note the absence of defensive deletions in this story and the fact that the issue of the Literary Gazette in which it was carried was one of the few to escape banning. (Norma Field)

|

First publication of “To Qiqihar” by Kuroshima Denji; illustration by Kitamura Zensaku. |

At the start of November, northern Manchurian ground begins to freeze.

The occupied Chinese houses were turned into temporary barracks. A piercing cold assaulted the skin even through winter coats made of fur.

Two weeks earlier, First Class Private Wada’s company had set out from Sipingjie. They arrived in Taonan by the Si-Tao line, and then advanced two hundred kilometers farther north.

The soldiers began to be afflicted by stubbornly proliferating lice.

“I wonder if it’s true that Russia is backing Ma Zhanshan.” They had not taken a bath for a full twenty days. Hoping they could soon withdraw to the rear, they discussed a rumor heard from above.

“It’s a lie.” Second Class Private Ehara denied it on the spot. Ehara was a soldier with no chance of promotion because he had once belonged to a labor union.

“But they’re supplying him with cannons and ammunition, aren’t they?”

“That’s a totally made up story.”

“I wonder.”

In the wake of shelling, countless Chinese soldiers lay scattered along the hills and trenches around the Daqing Station, looking like lumps of meat ravaged by wild animals. Wada’s company had occupied the area. That the Chinese soldiers had not been blessed with money or food or clothing while alive was evident from their malnourished skins and from the torn and ragged Sun Zhongshan jackets in which they lay. Seeing that, Wada shivered in spite of himself.

Following its retreat, Ma Zhanshan’s Heilongjiang army readied the ammunition and cannons and concentrated its forces to attempt a counter-attack. Russia was supporting this. A communist army of “Chinese and Koreans” had marched out of Blagoveshchensk as reinforcements. Such were the rumors that had spread through all the units.

“—The goddamned enemy’s not just the Chinese, so you’d all better not let your guard down even for a moment! Got that?” The pencil-mustached company commander repeated his warning.

Officers who returned from reconnoitering at the front line spoke of seeing Russian cannons.

“Can it be true?” Feeling numb as if anesthetized, many of Wada’s comrades were at a loss what to believe.

“How can they say Russia supplied the weapons? Just look at the guns the Heilongjiang army threw away when they ran off. Nothing but Type-38 Arisaka rifles, right?”

“Yeah, that’s right!” But the rumor began to spread wildly out of control.

One evening when they returned to the barracks from the occupied territory, letters were distributed to them along with the comfort packages.

“This year, looks like there’s a famine not only here but all over Hokkaido too. After paying the land tax, we don’t even have any straw left. . . .” This is what Wada was reading when a corporal arrived to summon Ehara.

“Something they want me to do?” Ehara asked uneasily.

“Don’t ask. Just come!”

“How do I know what it’s about if I don’t ask?”

“Shut up! . . . Moriguchi and Hamada, you come too!”

Not only Ehara but five or six others reluctantly rose and went before they had even had a chance to finish reading their letters. They lined up and marched out. Wada and those of his comrades who were left behind looked silently at one another’s faces.

Ehara and the others never came back.

The next day at dawn, the army received the order to proceed north.

After twenty-six hours of fierce fighting and marching, they advanced as far as Qiqihar. Clusters of Chinese soldiers lay about everywhere, like ants doused with boiling water. Horses shot in the legs were shrieking among the abandoned cannons and rifles. But no Russians, Russian rifles, or Russian cannons could be discovered anywhere. Wada gradually began to feel deflated as if his expectations had somehow been betrayed.

Translated by Željko Cipriš

|

The expansion of the Japanese empire. Source. |

(27) A Day at the Factory

NAGANO KAYO (Shimosuwa Circle)

Translated from Literary Gazette (Bungaku shimbun, April 25, 1932)27

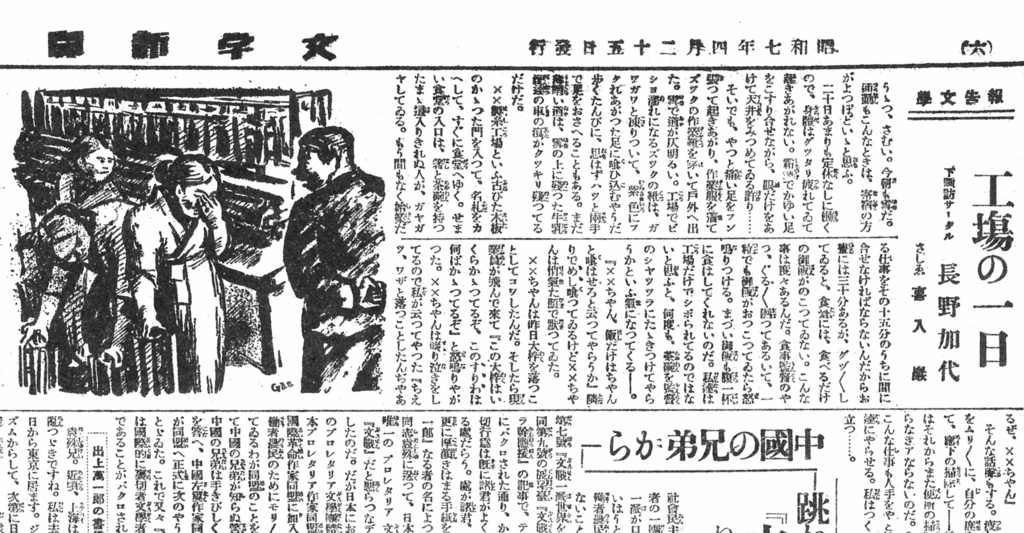

All we know about Nagano Kayo is her name, her membership in the Shimosuwa Circle (Nagano Prefecture), and what we learn from this piece itself. She is, in other words, one of the workers encouraged to write under the “Bolshevization” of the movement in the early 1930s, which meant taking the movement to the factories and the farms and hearing back from them. Absent the circle movement, it is hard to imagine Nagano thinking her experiences worth recording and sharing. In terms of format, her piece, illustrated by Kiire Iwao and published in the Literary Gazette, looks much like the celebrated Tokunaga’s “Shawl” in the Arts Gazette. The pedagogical function of such writing is made clear in Yamada Seizaburō’s critique [28] in the same issue. That the work and its review appear in the same issue provides not only a rare opportunity to witness a concrete example of the pedagogical process, but also to see what was important for the leadership as compared to the young factory worker, for whom the prospect of organized protest did not yet have immediacy. This aspect—of the lack of exposure to organizing—makes for interesting comparison with “Another Battlefront” [32], a piece of fiction by the comparatively experienced writer Matsuda Tokiko.

(Norma Field)

|

First publication of “A Day at the Factory,” Nagano Kayo; illustration by Kiire Iwao (1904-1989). |

Whew! It’s cold. Another snowy morning.

If you commute on a day like today, you realize it’d be a whole lot better just to live in the dorm.

I’ve been working for twenty days straight without a day off. My body’s plumb worn out and I can’t even get up. My feet are chilblained and itchy so I rub ’em against each other and just stare up at the ceiling. . . .

Anyways, I force myself to stand up and put on my work clothes and get into my canvas work shoes and head out the door. I can see the road in the weird faint brightness of snow. These canvas shoes, they get soakin’ wet in the factory then frozen stiff so they creak with every step and cut into my feet that’re all swollen and purple. It’s still a little dark, and all you can see in the snow are the sharp tracks of the milkman’s wheels.

I go in at the gate with a worn-out wooden sign saying XX Silk Filature, turn my name tag over, and head straight for the cafeteria. The narrow entrance to the cafeteria is abuzz with folks stuck there holding their chopsticks and rice bowls. It’s practically start time and the table only holds about twenty when there’s four hundred girls waiting for their breakfast, you can hardly eat in peace, it’s practically like you’re fighting with everybody. You get some crumbly black mixture of three parts rice and seven parts barley and just one plate of shriveled up greens for a side.

The monk who gives lectures on self-improvement at the factory preaches, “When you receive food you must bow in gratitude.” So some simple-minded fools actually bow to their food. You have to wash your own rice bowl. And there’s only cold water. So blood starts to trickle out of the cracks in your chapped hands.

It’s on us to soak fourteen reels. They’re metal, so they make your hands bleed. Can’t wait for ’em to get all callused up. . . .

The minute you hang up your cleaning rag on your seat or in the hallway, the shaft starts to turn. Even though start time’s supposed to be six thirty, work always begins five or even ten minutes early. And then you can’t hear nothing but the shaft roaring and the foreman yelling.

The only ones who take the fifteen-minute break at nine o’clock are the foreman and the clerk and maybe the guys. We gotta use that fifteen minutes to make sure we’re caught up on the work, because even though we’re supposed to have a half an hour at lunch, if we’re just a little bit late, there’s no rice left in the cafeteria. Matter of fact, this happens all the time. That damn cafeteria supervisor, he walks around and around, and if he finds a grain of rice on the floor, he starts yelling. They don’t even let you fill up your belly with that stinking food. When I think about how it’s not just in the factory that we’re being wrung dry, I want to take my rice bowl and smash it on the foreman’s mug—

“Hey, XX-chan. Shall we tell ’em they have to feed us right at least?” XX-chan was sitting next to me, eating but looking sad, not saying a word.

Yesterday, XX-chan let the big reel drop and broke it. Then a supervisor guy rushes over and has the nerve to yell, “This here reel cost a helluva lot. Same’s these rings.” XX-chan was sobbing so I says to him, “It’s not like she did it on purpose.” Then the guy glares at me, but who gives a shit. XX-chan just doesn’t have any guts. . . .

You can’t even sit down once during the eleven hours (in fact, more like eleven and a half hours if you add the time before start time and the extension of finish time), you’re just flying in front of the Minorikawa-style reeling machine, just hoppin’ around, so that by evening, everybody’s face is pale and their hairdo’s falling apart and all’s you can do is look at each other with sad faces. . . .

The big reel gets inspected under a dim ten-watt light and then gets inspected under a hundred-watt light in the quality-control section. Sure enough, the light’s different so it doesn’t pass, and then for punishment you have to sit on the wooden floor for over an hour and get preached at.

Finally, the shaft stops turning, and it’s like a big wind died down, it’s so quiet. We’re in a daze for a while, then from somewheres comes a sigh of relief.

“I’d just as soon die as live another day like this,” says XX-chan next to me in a pitiful voice.

“My chilblains are a-itching and a-hurting, maybe I’ll just take these shoes off.”

“You take those shoes off and you’ll really get it, XX-chan.”

You hear people talkin’ like that. Then you force your tired body to clean up your spot, then clean the hallway, and the person whose turn it is to clean the toilet has to do that, too. The company saves money by making us do these things instead of hiring somebody. It makes me so mad. . . .

Translated by Norma Field

|

Female factory workers at a textile factory using Masuzawa-style reeling machines, similar to Minorikawa-style. Source. |

[(28) Our Own Literature Course (1): A Guide to Writing Literary Reportage omitted]

(29) On Wall Stories and ‘Short’ Short Stories: A New Approach to Proletarian Literature

KOBAYASHI TAKIJI

Translated from Studies in the Newly Rising Arts (Shinkō geijutsu kenkyū, June 1931)28

This and the following piece [30] show Kobayashi Takiji (see [1] for biographical information) as theorist as well as star writer in the movement. This discussion of wall stories appeared in Volume 2 of a three-volume series, Studies in the Newly Rising Arts, which was, interestingly enough, a volume devoted to writings of the “aesthetic school,” understood to be generally critical of Marxism. Perhaps this indicates a special regard for Takiji as craftsman and/or tacit sympathy for his cause. Takiji himself doesn’t disguise his ideology or his purpose for one moment. His elaboration of the “risk of bias” is telling. “Bias” was the word routinely modified by “political” to indicate submission to the primacy of politics as the fatal flaw of proletarian literature. Takiji, however, uses “bias” to indicate “one-dimensional” and “formulaic” writing, which will necessarily thwart the political purpose of the genre: to attract readers without much education or spare time. Bad art, in other words, makes for bad politics. Was this primarily strategic?

Surely so. But we shouldn’t overlook the respect for the intended readership implicit in this view. That readership is deemed to be of “low cultural level,” a phrasing that doubtless makes us wince, but we might also acknowledge the resonance of the “wall story” project with our contemporary pedagogical principle of “meeting the students where they’re at.” It’s also interesting to see Takiji’s openness, in contrast to some of his comrades, to such popular writers as Kikuchi Kan (1888– 1949) as valuable guides to writing that could hold the interest of nonintellectuals. (Norma Field)

As writers, many of us have fully appreciated [Anatoli] Lunacharsky’s [1875– 1933] observation that we need to create literary works “elementary and simple” in content that will gain currency among the millions of industrial and agricultural workers.29 We have not, however, succeeded in producing works that live up to this ideal.

Early last year, some among our ranks misunderstood the ideological implications of “elementary and simple” content. Even after this misinterpretation had been rectified (“Resolution on the Problem of Popularization,” Battle Flag [Senki], July 1930), no concrete example of this concept—in other words, no “literary work”—appeared.

This results not so much from our sloth but rather reveals the practical difficulties of the task that we have been assigned.

From the latter half of last year, however, Battle Flag proposed that we experiment with wall stories. As for why Battle Flag embarked on this experiment, it was first and foremost our way of responding to the wishes of the people right away; it was also a matter of the writers themselves wanting to dedicate energy to this project. Though they are far from perfect in form, we have succeeded in finding in wall stories the early manifestations of a new type of proletarian literature, one grounded in “elementary and simple” content.

I can offer several reasons why wall stories will find favor among people of the industrial and agricultural working classes. First, they are only a page or two in length, so they can be read quickly at any time, any place, and moreover, they let the reader grasp something solid and coherent. Second, wall stories will be posted in places where workers and farmers congregate, and address topics of immediate concern to the masses.

Given such a role, wall stories hold great potential if we put effort into them. We must be wary, however, of the risk of developing a certain bias. What sort of bias do we risk?

It is the risk of understanding the role of wall stories one-dimensionally and formulaically. If such an understanding were to take hold, wall stories would turn into crappy old sermons ordering people to “do this and do that!” And in actual practice, all the wall stories to date seem to have succumbed to that tendency, despite the authors’ good intentions and efforts.

Nevertheless, to the extent that wall stories are wall stories as distinguished from “short” short stories—however much they may resemble them—I believe they have a limitation. The reason is the role with which they have been charged. In that respect, wall stories are bound to be a “one-dimensional” art form.

What I wish to emphasize here is that the genre of wall stories will have a completely new and significant influence on the field of proletarian literature. This is because wall stories can inform our interest in the “short short story” in proletarian literature, yielding rich contributions on the question of form in short short fiction.

There is an important reason for why I refer to “short” short stories here, rather than “short stories.” What would that reason be? Allow me to quote from my monthly literary review for the May issue of Central Review:30

A factory worker once said to me, “Can we get you to write lots of really short pieces that we could read in five or ten minutes?” The kind of story he had in mind was very simple, with a very specific theme, something that he could get the gist of immediately. A story that makes you say the minute you finish reading it, yeah, that’s the way it is, or, is that right—the sort of work that hits you smack where it counts.

In the case of proletarian literature, especially in Japan, which is pre- revolutionary, and where the cultural level of workers is low, I believe this type of short story has a special significance.

Many short stories familiar to us look like excerpts from novels with the beginnings and ends cut off. You finish reading them, and you don’t really “get” it. (However excellent they may be as examples of a certain kind of narrative, they fail to stand on their own as short stories. We have had many “excellent” short stories of this kind in Japan.) The minute you finish reading the last line of a short story, the story should become crystal clear to you.

Just as in the case of a bad joke, if the last sentence of a short story is vague and unclear, the reader feels unsatisfied and is likely to prefer an interesting, plot-driven novel. For workers who have little time or money, however, this is not an option. —For this reason as well, we must produce many, many short, convincing works.

Proletarian writers have much to learn from the “theme stories” of Kikuchi Kan [1888–1948] or the works of some of the excellent foreign short story writers who employ the conte form.

It takes a special talent and technique to master the short story form. One reason that we have seen so few convincing short stories is that many writers regard them as something to be slapped together when taking a break from novel writing, rather than as a form requiring a specific skill.

The important thing is that henceforth, when we “consciously” take up short stories in this sense, Lunacharsky’s dictum—that these stories must penetrate the stratum of workers of low cultural level by relying on “elementary” and “simple” content—will surely find concrete realization. . . .

I have only been able to discuss these topics in a very general manner, but I believe that this is one new direction that our Japanese proletarian literature must seek in 1931.

Translated by Ann Sherif

Notes

Here are a few of the works published on the centenary: Tariq Ali, The Dilemmas of Lenin (Verso, 2017); Laura Engelstein, Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914–1921 (Oxford University Press, 2017); Stephen Kotkin, Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 (Penguin Press, 2017); China Miéville, October (Verso, 2017); Ronald Suny, Red Flag Unfurled: History, Historians, and the Russian Revolution (Verso, 2017); Yuri Slezkin, The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution (Princeton University Press, 2017); A. James McAdams, Vanguard of the Revolution: The Global Idea of the Communist Party (Princeton University Press, 2017); a 30-article series in the New York Times on the “history and legacy of Communism” titled the “Red Century,” (February 24-November 6, 2017). In Chicago, where we live, the Art Institute of Chicago mounted the largest exhibit of Soviet art in a quarter century, “Revoliutsiia! Demonstratia! Soviet Art Put to the Test” (October 29, 2017-January 15, 2018); the University of Chicago, “Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago” at the Special Collections Research Center Exhibition Gallery (September 25, 2017-February 2, 2018); and the Smart Museum of the University, “Revolution Every Day,” a special exhibit of posters and video and film, mostly focused on women (September 14, 2017-January 28, 2018), yielding a catalog by the same title in the format of a Soviet tear-off calendar, Revolution Every Day: A Calendar (Mousse Publishing, 2017).

Joseph Masco, The Theater of Operations: National Security Affect from the Cold War to the War on Terror (Duke University Press, 2014).

Kurahara Korehito, “The Path to Proletarian Literature,” translated by Brian Bergstrom, in For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution: An Anthology of Japanese Proletarian Literature (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 178.

A partial version was first translated anonymously by Max Bickerton, an English teacher in Japan in the early 1930s, sympathetic to the movement, thanks to which he was subjected to arrest and torture, in The Cannery Boat by Kobayashi Takiji and Other Japanese Short Stories (New York: International Publishers, 1933). This version was reproduced in The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature, edited by J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

Kobayashi Takiji, “On Wall Stories and ‘Short’ Short Stories: A New Approach to Proletarian Literature,” translated by Ann Sherif, in For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution, 254.

Leonardo Boff, quoted in Julie McCarthy, “Pope’s Brazil Visit Puts Social Justice in Spotlight,” National Public Radio, May 8, 2007. A variant also appears in Bryan Stevenson’s work on racial injustice in the US penal system: “My work with the poor and the incarcerated has persuaded me that the opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice” (Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2014), 18.

“Intervista” (Finding the Words). Screened during the “Revolution Every Day” exhibit at the Smart Museum (see note 1, above).

“Chapter 5: Art as a Weapon” is an excerpt from For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution: An Anthology of Japanese Proletarian Literature (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2016). Republished with permission from the University of Chicago Press, the University of Hawai’i Press, the editors, authors, and translators. Not for additional publication without permission.

“Leafletting,” omitted from this excerpt. Numbers in brackets refer to works in the anthology [1-40] of which 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, and 29 are included here.