2017 and talk of war games is all around us. When The New York Times reported on 10 July of this year that India, the U.S. and Japan had begun “war games,” surely very few readers thought of these war games as actual games. After all, they were designed to have submarines slide unannounced into the deep waters of the Indian Ocean in order to silently take positions near the Indian coastline. When, about a month later, according to The People’s Liberation Army Daily China’s army commanders declared that the mobile phone game Honor of Kings endangered national defense, they were not joking either. They appeared convinced that the game had infiltrated soldiers’ and officers’ daily lives and that their addiction to the game would undermine their combat readiness.1 Around the world, many similar, and often contradictory pronouncements are made daily.

Roll back about one hundred years. Until the end of the Asia-Pacific War, in Japan at least, “war games” or “heitai gokko” more often than not referred to a range of war games played by children. In such games and pictures, Here, I tell the story of how Japanese children learned to conceive of war as play and how, in the words of a war game manual of 1913, “children’s little wars” connected and interacted with the “grand game”—a term that over the years has referred to both the annual grand maneuvers of the Imperial Army and Japan’s wars in Asia. I describe various modalities of and debates about children’s war play and its rules and regularities in the hills and along the rivers of nineteenth-century rural Japan to the killing fields of the twentieth century. Throughout, children’s war games have shared the qualities of instruction, training, and disciplining, thus embodying the modern notion of “continuous war” that has dramatically gained currency with the centralization of the power to make war, the rise of the nation-state, and the simultaneous marginalization of war to national borders.

|

In Miyagawa Shuntei’s Ikusa gokko (1897), two groups of boys face each other in a war game. Printed with the kind permission of Kumon Museum of Children’s Ukiyo-e. |

One chronicle, Rumors of Early Modern Times (Kinsei fūbun: mimi no aka) by Kondō Juhaku, referred to a children’s war game scenario in the following terms.

In 1855, a group of [Japanese] children gathered to play an ordinary war game, but in this game the children split into two sides, one American and the other Japanese. Each side had a leader, the Japanese side led by a twelve-year-old and the American side by a fourteen-year-old. The fourteen-year-old, being older, was considered the stronger, and for that reason alone he was able to draw ten new members to his side from the enemy. The children gathered bamboo rods and flung them about wildly pretending to be in the heat of a battle. That day the American side claimed victory. The next day the children gathered to play again. The leader of the Japanese side, however, was late. When he arrived, he had brought with him bamboo rods that had been whittled down to sharp points. The Japanese leader suddenly thrust one into the boy who was playing the leader of the Americans, and the boy immediately fell to the ground in pain. People from the neighborhood and the fallen boy’s parents came to his aid, but the wound proved fatal.

The angry parents took the matter to court. The court ruled in favor of the young boy who had killed the American leader. The court believed that he had done the proper thing and had defended his country by defeating the enemy: America. As a reward, he was given a lifetime stipend and his followers were commended for their behavior” (Kondō Juhaku, ed., Kinsei fūbun-mimi no aka. Tokyo: Seiabō, 1972:163; quoted in Minami Kazuo 1989[1980]:26–27, trans. by M. William Steele and Robert Eskildsen, 1989).

While we today may consider this anecdote peculiar, even shocking, Kondō revealed no such conflict of consciousness. He simply, matter of factly, noted that this was just one of many incidents that revealed the widespread anti-foreign sentiment held by Japanese commoners—and, one might add, their children—following the 1853 arrival of Commodore Perry’s fleet. That fleet’s arrival had been chiefly responsible for the much-resented opening of Japan to the West after roughly two hundred and fifty years of a largely “closed country” policy and a time of “great peace” (Roberts 2012).2 Kondō also did not allude in general terms to attitudes about the connections between aggressive military action and child’s play. We might speculate that he thought nothing of children enacting an ongoing adult conflict. Alternatively, he might have considered an incident involving military play leading to the death of a child as one particularly effective in describing both the mood of the time and the drama that mood was capable of unleashing.

In the hundred years or so since instances of children playing at war became a contentious subject. I am interested in how assumptions about three topics—children and childhood, play, and war and the military—have intersected, and how these intersections have evolved in the decades that followed during the nation- and empire-building efforts that began shortly after the incident Kondō recounted in the middle of the nineteenth century. More specifically, I examine children’s war games as manifestations and generators of rhetoric about the nature of children and the roles they ought to play. I interrogate what problems they pose for a nation intent on militarization and imperialism, and aim to describe the virtues attributed to children in order to symbolically sustain pacifism and carry the burden of Japan’s future later in the twentieth century. Such games, I argue, have on a number of occasions throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first prompted dramatic shifts in adult attitudes. Sometimes these shifts have been closely aligned with theories about child development; at other times, they have been driven by the requirements of a nation in crisis. For example, at one time, public rhetoric proposed that war games were to be understood as children’s unfortunate and dangerous enactment or impact of (adults’) recent, ongoing, or impending violent conflicts. At another, children’s war games were cited as (childish) manifestations of an innate human desire to destroy and kill. And while Japanese parents, journalists, social critics, child experts, and government authorities of one generation called for the control and suppression of such games, oftentimes the next generation just as aggressively promoted them—even to the extent of wanting them incorporated into school exercise regimes carefully choreographed and controlled by teachers and military instructors. Indeed, some generations of parents urged that war games regularly appear on the pages of children’s books and magazines—so as to establish such games as a tool to demarcate and reproduce both war as an inherently human endeavor and children, particularly boys, as always being already (and, thus, inherently) soldiers.

During the first half of the twentieth century, there was no linear progression from one attitude to another. Rather, educational and political elites in Japan and elsewhere—in agreement on the importance of children growing up fit for war—argued about which training, education, and play would best prepare them for that purpose. They did so somewhat enthusiastically after the Sino- and Russo-Japanese Wars and more aggressively with the onset of the Asia-Pacific War. Henceforth, they facilitated the creation of a children’s culture that increasingly had children—whether on school grounds or in the field or on paper—playfully explore, subordinate, and control the empire in the making. We might imagine that, separated from adult supervision and control, children’s games of war tapped into children’s joy in “playing with power” and fostered “childish omnipotence” (Kinder 1993).3 I explore the role of such instances of childlike omnipotence in sustaining children’s war games—on the ground, on paper, and on screen—from the late nineteenth century through to today. From early on in this story, children’s war games provided children with opportunities to apply and deepen their knowledge of territory, maps, and geography. In many ways children’s war games mimicked the playful colonization of territory, first in the field and on paper, then within a virtual topography. It is not so much that each new style of war games eliminated the styles that had preceded it; instead, the styles coexisted, bled into each other, and mutually informed techniques, strategies, and tactics.

From the beginning of the twentieth century onward, educational and political elites reenvisioned war games as ideal tools of nurturing in children an enthusiasm for war. Many spoke and wrote about how, through children’s engagement in war games, children and soldiers were infinite reflections of one another. Playing war, many adult commentators imagined, would inevitably lead to (the will and ability to) make war. Contemporary critics disagreed, however, on whether children shared an enthusiasm for such play that could be understood as “natural” and thus inherent in all children, or if they perhaps felt an equally inherent resistance toward war games. For instance, Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962), prominent commentator on his times and founder of Folklore Studies, suggested there was a special relationship between children and militarism. He observed that, prior to the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), only those in elementary school considered “soldiering something splendid” (Yanagida 1957:236). Beyond those youngest children, he confidently claimed, “the militaristic spirit did simply not exist.” He did not posit whether this was because children conflated war games with war, thinking of both in terms of entertainment and fun, not death and destruction; nor did he indicate whether he meant to imply that anyone who shared such enthusiasm necessarily viewed war with a child’s mind. Regardless, with Japan’s victory over China in 1895 all of that changed. The “Japanese public’s enthusiasm for the military climbed to fever pitch” and, according to Yanagita’s recollections, “it gradually came to be considered a great distinction for a young man to be conscripted” (Yanagida 1957:236).

In actuality, the relationship between children and militarism had been more ambivalent and contested than Yanagita recalled. The meanings of and the interrelations between modern notions of childhood, play, and war varied a good deal depending on whether that play was the preoccupation of a handful of children after school, simulated grand maneuvers of the Imperial Japanese Army enacted by masses of school children and recorded in newspapers, or the imagination captured in children’s books, magazines, and other manifestations of children’s culture. These are my questions: How were the rules and regularities of war play negotiated and who had a say? What made adults so firmly disagree on the value or risk of such play, and on whether children’s war games should be suppressed as dangerous, furthered as a vehicle of discipline and militarization, or viewed as an expression of their inherent and still intact human nature? These questions lie at the heart of what I explore, especially in the nefarious underpinnings of such a philosophy. For, if children have a natural inclination to play war – as many adult commentators around the globe have claimed throughout modern and contemporary history – perhaps the adult will to make war is natural, normal—and thus, at times at least, inevitable and unavoidable, perhaps even something to be fully embraced. Of course, there is a flip side to this thinking as well: if children’s desire to play war can be incited, perhaps their will to make war as adults can be developed early on, to the inevitable and indefinite betterment of the military machine. And yet, war play was also perceived as a social phenomenon with dangerous potential: not just of contradicting modern notions of “proper” childhood, but also of challenging social and political order if left unsupervised. According to the Yomiuri Shinbun of 22 February 1877, “children’s war games in the field hold plenty of dangers,” and yet, “lots of children got together to play soldier. They fought, district against district, with bamboo sticks and small stones and some got injured” (page 4). Shortly after, on 21 March (1) the same newspaper reported that the Education Department of Tokyo Prefecture had advised primary school teachers to reprimand pupils who engaged in “play that imitated the military” (ikusa no mane to shite). Yet just one month later, on 12 April 1877 (1), the Yomiuri lamented how more than one hundred children had staged a play battle “imitat[ing] the military”—with many injured in the process.

That same year, Edward S. Morse—another foreign advisor to the Meiji government and the Tokyo Imperial University’s first professor of zoology—suggested that such “bad games” were inspired by that year’s Satsuma Rebellion against the new Meiji government (Morse 1978:297). According to newspapers of the day, children’s war games escalated around New Year’s Day of the following year. In one account, a group of fifty to sixty children, including six- and seven-year-olds, split in two groups—Eastern and Western armies—with a fifteen-year-old serving as the commander. Every morning a war cry launched a fresh skirmish fought with stones and bamboo sticks—continuing until the evening only to begin anew the next day. Eventually, the children were even joined by men as old as twenty-five and twenty-six in what by then was called their “great war of every evening” (maiyū no daisensō). In response, on 22 March 1878 the daily paper Chōna Shinbun established a column titled “Watching Commentary” (Kansen shōgen). According to that column of 30 March, a children’s army, made up of ten members between the ages of six and fifteen, had started a war on the north side of a local shrine that resulted in a variety of injuries, including to the eyes. The columnist appealed to the local community, demanding that parents, schools, and businesses collaborate to prevent children from engaging in such dangerous play (Ujiie 1989:90–91).

The columnist’s appeal highlighted a series of contradictory moves—years in the making—that the new Meiji government, the education establishment, the military, and the fledgling modern print media had all separately worked to both decouple the identification of the samurai class as warmongers and link children to the welfare and power of the nation. These efforts began in earnest in 1872, when the Meiji government implemented two laws that had revolutionary, modernizing, and democratizing effects. One was the universal and mandatory Conscription Act, which coincided with the dismissal of the old warrior class, the samurai, as men who had “led an easy life, were arrogant and shameless, and murdered innocent people with impunity” (Lone 2010:15). The other was the Fundamental Code of Education: mandatory elementary education for both boys and girls, which was introduced the same year by Mori Arinori, the architect of Japan’s modern education system. Together this new legislation both rewrote what it meant to be a child and, at the same time, reset the boundaries for male maturity. As the new education system unfolded in the decades to follow, new terms named and distinguished the young primarily by level of schooling. The Education Law (Kyōikurei) of 1879 classified all children of elementary school age – from six to twelve – as “jidō”; “student” (seitō) came to universally apply to children between elementary school and university. The Kindergarten Ordinance of 1927 distinguished kindergarteners as “yōji”; later, the post-Asia-Pacific War education laws distinguished between kindergarteners (“yōji”), elementary school children (“jidō”), middle school and high school children (“seitō”), and university students (“gakusei”) (Moriyama and Nakae 2002:18–21, Kinski 2016). With the introduction and development of a universal school system, the exact age of a child—which had once mattered much less, and whose significance had greatly varied across different classes—became a significant marker of the bounds of childhood. For a while children’s and youth groups in rural areas remained more important communities than the schools, but these new terms, and the age identities that went with them, gradually replaced the older ones. Before long, gone were terms that had identified the “child that was young enough to still nurse” (chigo), the child that had “messy hair and laughed a lot” (warawa), or the child so young that it “was not quite yet a human being” (kozō)—in addition to numerous other phrases that either signified children of various ages and statuses or referred to other individuals found to (inappropriately) behave like them (Moriyama and Nakae 2002:8–19).

In 1905, 90 percent of Japan’s children attended or had attended school. In addition to the new nationwide education system, other knowledge systems also took shape around 1900, contributing to a view of children as an avenue to the potential control by and guidance of the adult members of their families and society as a whole. Modern Japanese education legislation, from the Fundamental Code of Education to the Imperial Rescript for Education (Kyōiku chokugo) of 1890 and beyond, conceptualized children as yet-to-be-formed individuals primarily designed to realize adult goals for the nation (Okano and Tsuchiya 1999:15–19; Amano 1990:xiii–xiv; Inagaki 1986:79). Pedagogues, physicians, politicians, and other contemporaries concerned with the future of the Japanese empire in turn began to promote programs both to further children’s physical exercise and cleanliness in schools and to better balance scholastic training—which had come to dominate school education—with physical modes of training. In addition, welfare institutions for children were developed, and child protection laws were implemented (Frühstück 2003). The representatives of the new field of pediatrics confidently promoted the notion that childhood ought to be a realm separate from adulthood. They insisted that children were particularly vulnerable and worthy of study, special care, and protection—concepts that were framed primarily in terms of social order and control and only secondarily in terms of scientific and socio-political concerns, all the while working to ever more clearly distinguish and separate children from adults.

Schools did their part. New physical exam systems, first in military barracks and, later, in elementary schools, allowed physicians to define, name, and hierarchize the markers of healthy childhood. These examinations valorized maturity and manhood in medical and social scientific terms—for decades excluding women and girls beyond the elementary school level. Likewise, military physicians determined that a healthy twenty-year-old male of at least 150 centimeters (4’9″) and 50 kilograms (110 pounds) was to be considered a first-class conscript. Such was a source of pride for some young men and their families and communities; others felt great anxiety about the possibility of being drafted. The results of these health exams determined that the young generation’s condition was inadequate, even weak, alerting military men, pedagogues, medical doctors, politicians, and other contemporaries concerned with charting the future of the empire of the necessity of developing programs for the improvement of youths’ physical fitness and hygiene. In particular, the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) served to both lament the quality of boys’ physiques and to vigorously urge their improvement. Strikingly resembling similar debates about children’s bodies around the world, this Japanese debate centered on the proper balance between learning and training, freedom and discipline, protection and control, intellect and force.

By the early 1880s military medical personnel conducting the physical exams for conscript-aged twenty-year-olds still frequently noted that some young men demonstrated feeble health, lack of enthusiasm for military training, and effeminate demeanor. Similarly, Japanese school children were seen as lacking in essential discipline. This latter finding was intriguing given the fact that many schools had taught gymnastics as a form of paramilitary training as far back as the time of the 1853 arrival of the Black Ships—long before many of such facilities were converted into elementary and middle schools, after which school exercises played an increasingly important role in encouraging good health, unity, and cooperation. And so schools next adopted the army infantry manual for their physical education; first implemented in secondary schools, these military exercises were soon after expanded to elementary schools as well.

At the same time, individual educators called on the public to do more to steel the character of children. The strength of boys’ bodies came to be considered crucial to the strength of the nation. Education ministers ordered more physical exercise for elementary school children; more advanced elementary school boys were in addition assigned military exercises accompanied by the singing of war songs. Pupils were encouraged to lead a healthy lifestyle, which was to include walking to and from school. Subsequent school ordinances prescribed raising the consciousness of the national polity, instigating the spirit to defend the fatherland, and strengthening loyalty and allegiance (Lone 2010:132–133). Much of these efforts took place within a country at peace; consider, then: what of the environment at home during times of war?

Playing to the Tune of Japan’s Modern Wars

At the onset of the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Japan’s first modern war primarily fought over the control of Korea, hundreds of school children engaged in war exercises under the careful choreography of their teachers and military instructors. Indeed, care was taken in all details: even boys’ school uniforms were altered, their baggy sleeves trimmed so as to move in concert with the pumping arm. The singing of martial songs celebrated the courage of Japanese soldiers, declared enemies were taking flight, glorified enlistment in the Imperial Japanese Army, and evoked historical precedents of former aspirations toward Greater East Asia (Eppstein 1987:438; Manabe 2013). All this glory had a distinct purpose: the Sino-Japanese War engaged a mass army, its troops drafted in a conscription system that, theoretically at least, could include any able-bodied man aged twenty or older—and, of course, a boy all too quickly reaches age twenty. And yet, since the fighting mostly took place in far-away Korea, there were limited opportunities for Japanese society to envision the action at the front lines.

Back home in the meantime, children’s war games increasingly served as a rhetorical platform: children’s “nature” was to be productively unleashed and managed. The proper balance between the two, however, remained contested until after World War I. Children’s war games could be any size—from a few dozen students to several thousands. The larger ones sometimes simulated the grand maneuvers of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) taking place nearby. While some rural folk met the arrival of large IJA troops with a measure of hostility, as the IJA’s reputation was for some ambiguous and for others outright negative. At the same time, the IJA’s maneuvers often enjoyed a certain appeal as rare, impressive public spectacles, entertaining theatrical displays intended more to impress the public than to prepare troops for combat—in short, an adult war game of sorts (Yoshida Yutaka 2002; Lone 2010). At the annual grand maneuvers held in Gifu in the spring of 1890, for instance, 30,000 men and about twenty naval vessels participated. It was, Stewart Lone (2010:18) suggests, “the biggest show in town.” In a similar vein, military camps also welcomed the public to share in the anniversary of their founding. On such occasions, several thousand tickets were issued for relatives and friends of the troops, along with parties of school children, local dignitaries, and ordinary citizens.

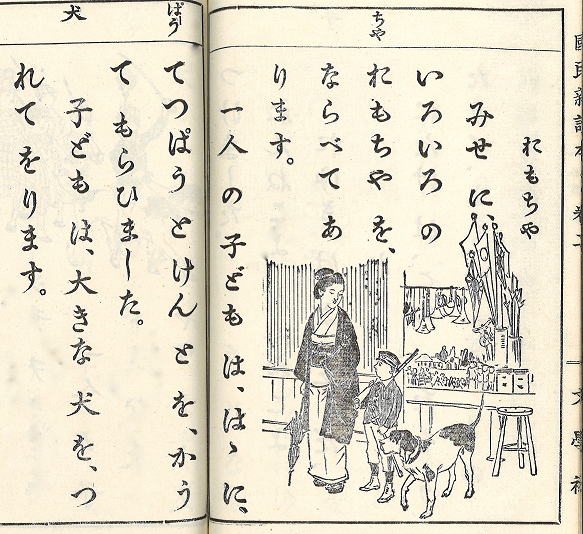

The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) marked yet another forward march in the trend of associating childhood with war by debating the notion of children as future soldiers in more concrete terms than ever before. School textbooks matter-of-factly featured weapons and the military in ways that suggested a normal trajectory of boys growing up and becoming soldiers—and war play as a logical route to get there. One, the 1899 Kokumin Shindokuhon (Citizens’ Reader) for elementary school children features an illustration of a boy holding a toy rifle and a sword accompanied by his mother and a dog inside a toy store. Under the heading “Toys” the text reads, “In the store there are all kinds of toys lined up. One boy’s mother bought him a rifle and a sword.”

|

A page from the elementary school reader New Citizens’ Reader for Use in Elementary Schools (Kokumin shindokuhon jinjō shōgakkōyō), 1899. Private collection. |

With the pronounced emphasis on toughness and the embrace of militarist values in schools, “playing soldier” was promoted both in schools and in children’s books and magazines. One man who was a child at the beginning of the twentieth century remembered “naturally” splitting up in groups of children that mixed boys and girls and playing war together. War games could be played “by just about any child from the rural poor to the urban underclass,” and so they belonged to the most popular children’s games during the 1920s. No equipment was needed to play them, not even a ball (Kami Shōchirō 1977:54–58).

By this time, the previous adult ambivalence toward such games began to subside, even when the games were conducted by children alone, and even when they led to injuries. But since the games were no longer exclusively or primarily self-organized, whatever defiance boys might have previously felt in playing them on their own seemed to have been lost. Likewise, the earlier practice of role-playing past or present conflicts gave way to anticipating the wars of the future—or, at least, anticipating the boys’ future participation in war. As such, textbooks shifted toward a new tolerance for and an encouragement of dangerous play for boys.

In the hope that such games would further a sense of intimacy with and admiration of soldiers and soldiering, textbooks even prescribed war games (heitai gokko) at school. This transformation of war into child’s play at school also took the form of mock battles, which were variously referred to as “war exercises” (sensō undo), “mock war” (mogi sensō), or “children’s war” (kodomo no sensō) (Lone 2010:55, 68–69). In addition, school textbooks claimed that Japanese boys were the strongest in the world and that singing military songs made a boy a proper Japanese man (Yamasaki 2001:38, 41, 48). While the various names of these war games tended to gender-neutrally identify “children” as players and we know from contemporaries’ recollections that girls war not necessarily marginalized in the games themselves particularly not when left to their own devices (Piel 2017), textual and visual descriptions typically ascribed the role of the attackers and combatants to boys and featured girls as nurses, observers, or performers of wartime duties at the homefront.

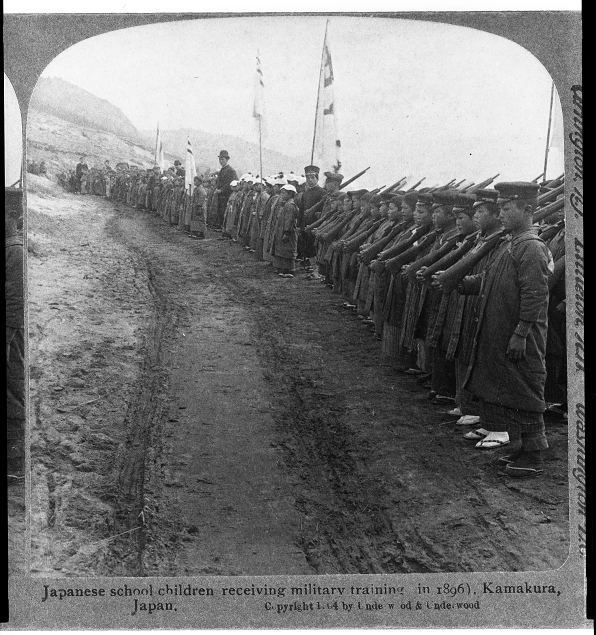

|

Elementary school children receive military training in Kamakura in 1896. Printed with the kind permission of the Library of Congress. |

While children did continue to marshal their own war games for fun, large scale children’s war games were thereafter held under the watch of teachers and military instructors, as they were seen as preparation for later military training. At one such occasion, hundreds of “Japanese [elementary] school children receiv[e] military training in 1896, Kamakura, Japan.” Based on at least one photograph taken at that event, children did not consider such war play—commanded by teachers and military instructors—to be much fun. And while both boys and girls participated, the boys were armed with rifles and wore caps, while the unarmed girls wore headscarves. Among the grown-ups are male and female teachers, as well as at least one man who, by the look of his cap, could have been a member of the military (see fig. 3).

To some extent, the transformation of play went hand in hand with the transformation of the words representing play. This was part of a wave that swept the nation of naming both a variety of phenomena perceived to be new and phenomena that had changed to such a degree they were no longer recognizable. For example, texts from as early as the twelfth century included terms like “ikusa.” Meaning “military,” “ikusa” could also stand for “soldier,” “war,” and “battle.” As both “asobi” and “gokko” signify play, “ikusa asobi” and “ikusa gokko” had long referred to playing war. But in 1868, The Chronological Tables of Takee (Takee nenpyō 1868:217) introduced the terms “heitai” (soldier) and “sensō” (modern war), which led to new phrases of “playing soldier” (“heitai gokko”) and “playing war” (“sensō gokko”). This terminological change derived both from the fact that the modern army was no longer composed of samurai but of conscripts (heitai) and from the engagement in modern wars beginning with the Sino-Japanese War in 1894–1895 (Hanzawa 1980:10–12).

Despite this orderly formal nomenclature, however, older terms continued to appear in twentieth-century publications, and children still engaged in a variety of war games of their own: in the fields, in the backyards of houses and temples, on the streets, and in exercise areas of military barracks. Though such games could be played in indefinite variations, the basic principle was always to separate into two groups, friends and foes—usually one as Japan and the other as China. Modeling their hierarchy on the actual military, children designated ranks and roles before commencing battle, carrying toy weapons that, over time, were ever more realistically fashioned after those of the Imperial Japanese Army. Starting on a signal, the children—often, all boys—enacted various maneuvers, from moving toward one another in large packs to one-on-one fighting. The battle was declared over when the enemy position was conquered, the general overwhelmed, or the flag captured (Hanzawa 1980:13–17).

Despite the move in the wake of the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars toward incorporating such war games into grade school curricula, attitudes toward children’s war games off school grounds remained a point of contention. For decades, school and military officials debated the pros and cons of unsupervised war games: They noted the benefits for physical health, and the development of strength and stamina. They saw them positively as a sign of children’s virility, boundless energy, and playfulness. Yet, they were also aware of the dangers, namely the very real potential for physical harm and the sometimes-unclear boundaries between a war game and socially disruptive behavior. Accordingly, newspapers of the day also expressed concern, regularly reporting on the injuries—even deaths—of children engaging in battle games along the rivers of urban Japan, and urging parents to prevent such dangerous and misguided behavior. Ultimately, no one could determine which instances of unsupervised war games were an expression of disobedience and which were a challenge to social order; the latter assessment of course fed into the latent anxiety about the wildness and uncontrollability of children.

For example, the spring of 1904, about a month after the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, the Yomiuri Shinbun noted how

school children of Shinshū Elementary School played war (heitai gokko). . . . [O]ne child who played a Russian soldier got killed. It was a serious affair for the whole country (Yomiuri Shinbun 14 March 1904, 1).

In an article of 28 May 1904—by which time it appeared that children’s war games simulated the ongoing war with Russia, prompting the police to break them up—the Yomiuri Shinbun appealed to parents with a pointed warning: “Parents beware! War games (ikusa gokko)”:

This too is the influence of war. . . . [S]everal tens of other boys gathered, divided themselves in four parties, and played war, including a “medical squad” and a field hospital. The police captured four of the boys. They were released upon a warning to their parents (Yomiuri Shinbun 28 May 1904, 3).

While the tone of this article is alarmist, particularly about the extent to which children played such dangerous games beyond adult supervision, the ongoing debate about children’s war games often highlighted the necessity of controlling and directing children’s inclinations to play (ongoing adult) war.

Other contemporaries were convinced that war games constituted “a pastime of choice for school children the world over.” For instance, Georges Ferdinand Bigot (1860-1927), a French language teacher and gifted illustrator, cartoonist and artist working in Japan from 1882 to 1899, noted in the Supplément Littéraire Illustré of the prominent Parisian newspaper Le Petit Parisien how “the zeal with which they play grows when, in any part of the globe, a real war unfolds its terrifying and grandiose spectacles” (see fig. 4). “Thus, in the schools of Japan,” he reported:

Under the watchful eyes of teachers, students organize into two enemy camps. One group represents the army of the emperor, while those students who play the role of Russian troops don fur hats that vaguely make them look like Siberian riflemen. A white flag decorated with a red star guides the defenders of the Empire of the Rising Sun, while their adversaries rally around the Tsar’s banner. Then, both sets of troops, armed with sticks whose tips are covered in a ball, charge towards each other, crossing their harmless weapons. The melée is soon generalized and numerous blows are given and taken, in the presence of young girls who witness this miniature war game (4 September 1904, 288).

|

Georges Ferdinand Bigot’s illustration La petite guerre dans les écoles Japonaises appeared in the Supplément Littéraire Illustré of the prominent Parisian newspaper Le Petit Parisien, 4 September 1904. Private collection |

In contrast to both the anxious tone of the Yomiuri Shinbun and Bigot’s bombastic voice in 1904, in 1914 the magazine Fujin to Kodomo (Women and Children) took a more contemplative stance about the martial games children played beyond the confines of adult control.

As its title suggested, in “Children’s Games of War: There Are Seasons for Children’s Games,” Watanabe Fukuo explained that for every play there is a season. In spring, the time of the cherry blossoms, he noted that children played peaceful games. In the high temperatures of summer, children avoided vigorous, sweat-inducing play, favoring water games instead. But once the weather cooled off again, children resumed playing more active games. And, so, they quite naturally played war games (gun gokko) in autumn, especially as fall was the time of the grand army maneuvers—adult games of sorts, he seemed to be implying, for children to imitate. Yet the author acknowledged that, beyond seasonality, one might take any number of positions on children’s war games; it so happened that his view was favorable in terms of the benefit of such play, not just for children at the individual level, but also for its larger societal implications.

|

Shot by an unnamed photographer in 1914, this press photograph, with the caption “À Tokyo, petits Japonais jouant à la guerre,” features a small group of Tokyo boys playing war. Printed with the kind permission of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. |

At the individual level, Watanabe commented on how children had become increasingly selfish and egotistical. He felt war games taught them to suppress these sentiments, instead learning to embrace group spirit; as such, the experience of playing war games would serve them well when they grew up and needed to navigate the social world of adults (Watanabe 1914:487). As for the societal level: the article explained how during such “over-civilized times” children need to be taught that, in a state-against-state conflict, Japan would prevail only if the population was strong. As such, successful “self-defense” at the state level rested on the “martial education” (gun no kyōiku) of children (488). The nurturing of such a military spirit was to be conducted in schools and families. Women specifically were to be charged with the “training of the will” (ishi no kunren) of the children in an effort to replace what Watanabe believed to be an obsessive focus on materialistic gain (489–490). Like Watanabe, many commentators expressed or at least implied a logical progression from children’s war play to war exercises and from drill to the willingness to support or even go to war.

It seems that articles such as Watanabe’s successfully convinced publishers and administrators that war games would remedy the aforementioned complaints about children. Thereafter, war games featured in children’s books and magazines appeared to be put on by children almost entirely without adult encouragement, interference, or presence. Watanabe’s anxieties about the corrupting effects of modern urban life on children, however, were echoed around the world. Children’s war games were variably discussed as countermeasure against the weakening of children’s bodies and minds brought about by modern urban life and, particularly in the wake of World War I, as proper preparation for or regrettable result of the war around them. Indeed, during the time between World War I and World War II, the power, purpose, utility, and impact of children’s war games were at the core of a global conversation that was in part fueled by the internationalism of pedagogical concepts (Ambaras 2006, Jones 2010, Frühstück 2003); international travel tours of delegations of paramilitary youth groups ranging from the Boy Scouts to the Hitler Youth (Bieber 2014); the beginnings of the industrial production of war toys in a number of places around the world; and the first studies of the impact of war on children in light of the wide acknowledgment of the heretofore unprecedented magnitude of the social impact of war.

Falling in Step with the Imperial Army

Despite its relatively small role in World War I on the side of the United Kingdom, Italy, France, and the United States, and against the German (1871–1918) and Austro-Hungarian (1867–1918) empires, by the close of the war Japan emerged as a great power in international politics. As a result of the Versailles Peace Conference, Japan gained a permanent seat on the Council of the League of Nations, and the Paris Peace Conference confirmed the transfer to Japan of Germany’s rights in Shandong, China. Similarly, Germany’s more northern Pacific islands came under the Japanese South Pacific Mandate. With the Japanese military’s increased predominance abroad, so too increased its sway back home, a stature that could also be seen in children’s cultural sphere in the decades to follow. For one thing, by the end of World War I newspaper reports on children’s war games retained none of their previous tone of alarm. Take for example the Yomiuri Shinbun: the same paper that less than fifteen years prior had so consistently warned of the dangers of children’s war games on 24 November 1918 announced the third Battle Game Tournament of twelve participating elementary schools, an event launched with a ceremonial parade (Yomiuri Shinbun 24 November, 1918, 5).

From 10 March to 20 July 1922, more than eleven million people visited a peace exhibition (Heiwa Kinen Tōkyō Hakurankai) in Tokyo that was held to commemorate the fifth anniversary of World War I. Only two years later, adult “war games” enjoyed increased approval. In 1924, when the Imperial Japanese Army planned its autumn maneuvers in Gifu, it received more than fifty thousand applicants from children and women’s groups who wanted to attend. Back in 1890, several thousand had been granted the honor; in 1924, the IJA approved all fifty thousand. And, previously such maneuvers’ spectacular character had been somewhat limited by the terrain, with the narrow roads and paddy fields of rural Japan hampering engagement of large-scale movement of troops. In later years, the larger appeal—and potential of cinema newsreels—prompted the staging of maneuvers even farther from populated areas, while nonetheless reaching an even larger audience. On 27 February 1925, the Yomiuri Shinbun noted that twenty thousand elementary school children—plus ultimately another ten thousand onlookers—would soon be engaging in a war game to honor the founding anniversary of the Imperial Japanese Army. The event would include a military music concert by the Toyama School, followed by the exercises of various branches of the IJA (Yomiuri Shinbun 27 February 1925, 5).

Earlier that year, as deemed by the Army Active Service Commissioned Officer School Ordinance (Rikugun geneki shōkō gakkō haizokurei), military training (gunji kyōren) of students in middle schools, high schools, and universities fell under the direct control of the IJA.4 In 1931, a range of children and youth groups was merged to form the Greater Japan Alliance of Youth Associations (Dai Nippon Rengō Seinendan). Commissioned army officers, using their own infantry drill manual (Hohei sōten), taught rules of command (shikihō), lectured on military affairs and military history, and conducted both formal and informal marching and battle training (Akiyama 1991a, 13–14).

In autumn of that year the IJA invaded Manchuria, an event that the Japanese press would thereafter refer to as the Manchurian Incident and that was considered to have been engineered by the Imperial Japanese Army as a pretext for invading northeastern China and establishing the puppet state of Manchukuo. The subsequent establishment of its puppet state Manchukuo increased Japan’s diplomatic isolation and eventually prompted Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933. As a result, with troops now even farther from the homeland, active duty soldiers felt an increasing alienation from society back home. Around this time, reports about and references to children’s war games in print media lost their last vestiges of ambivalence and ambiguity. For instance, when the magazine Fujin Kurabu (Women’s Club) ventured to advise mothers on how to “successfully raise extraordinary, beautiful children” in a supplementary guide to its September 1932 issue, it hinted at the usefulness of such games under the heading “Preparations for Entering Elementary School.” The text, written by Nishiyama Tetsuji, must have been intended to address or, perhaps, create maternal readers’ anxieties about their children’s potential inability to suddenly handle the demands of group life—especially for children raised exclusively at home or without friends. While the article somewhat neutrally advised that “playing with children in the neighborhood” would go a long way toward “preparing the child for school,” the drawing that featured such neighborhood play had heavily armed boys engage in a street war game.

Some parents no longer needed such encouragement, having already wholeheartedly embraced the concept by buying toy weaponry and other everyday items that referenced war and the military. For example, the 15 June 1932 issue of the photo magazine Tainichi Gurafu (vol. 4, no. 6), printed an entire page with baby pictures sent in by reader-photographers. Centrally placed is a photograph of a little boy in a tank-shaped stroller pushed by a girl of perhaps five years of age. Under the heading “Children’s Heaven,” the humorous caption reads: “Baby in a tank—he is going to Manchuria but the tank won’t move. So his sister pushes from behind”.

|

For some, the idea of “children’s heaven” included playing soldier, as illustrated in the magazine Tainichi Gurafu, 1932. Private collection. |

Likewise, in its October issue of 1936, the elegant magazine Hōmu Raifu (Home Life) printed a photograph that featured boy attendees of the Ōsaka Aishu Kindergarten playing war with wooden toy rifles (Tsuganezawa 2006:135). As such, we can see that representations of war games had by this time become utterly normalized, even for the youngest children and, perhaps particularly, for upper-class children—who spent less time playing unsupervised than did their less-protected peers.

|

This illustration by Satō Shigeo originally appeared in the October 1936 issue of the elegant magazine Home Life (Hōmu Raifu), published by the Ōsaka Mainichi Shinbun Press. Printed with the kind permission of Kashiwa Shobō. |

|

A children’s game of war (ikusa gokko), according to the 1932 publication Album of Pictures for Boys’ and Girls’ Self-Study (Shōnen shōjo jishu gaten). Private collection. |

Similarly, drawings of war games featured prominently in a 1932 volume titled Album of Pictures for Boys’ and Girls’ Self-study (Shônen shôjo jishu gaten). One drawing, by a teacher named Honda Shōtarō, was of children “playing soldier” (ikusa gokko) (31). It appeared next to two of his actual “war pictures” (sensō-e) (30).

The text cheerfully praises the “brave soldiers” in the children’s game and suggests that child readers may “play soldier themselves as well as enthusiastically draw similar pictures of their own war games.” I must note that, overall, only a handful of pictures in this work feature war and the military, and only represents a children’s game of war. My point here is that the messages such pictures and the accompanying text convey indicates how utterly normalized children’s war games had become—so much so that children were shown battling one another even in a progressive publication, one whose intention was the democratization of art. Indeed, the volume was created by a group of artists, educators, and activists of the School Art Association (Gakko Bijutsu Kyōkai), whose key goal was to bring art (education) to the masses. While the drawings themselves were produced by the adult members of the association, the volume was put together with the declared intention of encouraging children to make their own art at home—indeed, to be inspired by the pictures found within to make yet others of their own imagination (foreword).

By that time, visual and textual instructions on how to conduct such war games had long appeared in children’s magazines and books. Kōdansha and other large publishers produced hundreds of books and magazines for children and youth with military themes, some of which depicted toddlers playing with “soldiers’ toys” and only slightly older children engaging in battle. So as to bring these often wild and dangerous outdoor games home, publishers also advertised war games as special features or magazine supplements. Simultaneously, war games increasingly permeated indoor board and paper games, battles to be fought on tables and floors. Here, I want to emphasize that newspapers continued to consider children’s outdoor war games news—at least soft news. It did not take long for international media to pick up on the vibe: The cover of the 21 November 1938 issue of Life magazine, for instance, featured a “little tycoon” photographed by Paul Dorsey on a Tokyo street while shooting a series of photographs on “Japan at war.” The caption inside the magazine read:

That day Tokyo was full of processions of departing soldiers and friends and this was the best picture of the Japanese who stayed at home. In war or peace Japanese boys prefer to play soldiers. Naturally this one thinks it would be the finest thing in the world to be with the Japanese armies in China. To that end he has a gun (13).

The remainder of the description romanticizes Japan’s samurai past (“a tycoon is an old-time Japanese war lord”), belittles the conflict in Asia, and, inadvertently, conveys how very distant that war felt to American media and, presumably, American readers—less than a year after the six-week Nanking Massacre that began in December 1937 and just three years prior to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

|

The image of the war-playing Japanese boy fascinated Western journalists and photographers far into the 1930s. Printed with the kind permission of Time, Inc. |

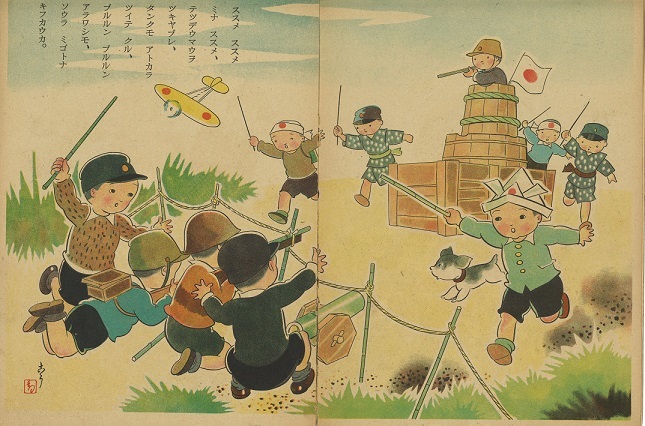

|

The 1941 book Japan’s Children (Nippon no kodomo) promoted children’s imitations of battles for the youngest readers in pictures stretched across several pages. The text puts the following dialogue into children’s mouths: “Forward, forward, everyone forward, break through the barbed wire, the tank also follows behind, vroom, vroom, look at the eagle exhibiting a beautiful dive too” (Takeda and Toda 1941: 6–7). Private collection. |

Newspapers condoned—indeed, enthusiastically embraced—children’s outdoor war games, often particularly praising efforts to make the play “realistic.” And so on 12 June 1938, when the Yomiuri Shinbun reported that a child playing war with friends had slipped into a river and drowned, it did so matter-of-factly (Yomiuri Shinbun 12 June 1938, 7). Gone was an inclination to appeal to parents to protect their children from such dangers; gone was any reference to “a tragedy for the entire nation.”

Less than a year later, on 12 March 1939, in an article titled “Fierce War Play On Top of Growing, Young Grass” (“Moeru wakakusa no ue ni isamashii heitai gokko”), the Yomiuri Shinbun encouraged its youngest readers to step up their game, “progress[ing] toward engaging” as if in a “real war” (jissen-dōri). To that end, the paper described such advanced play, reporting how at an unnamed location thirty to forty children had fought each other following battle plans laid out by an army colonel straight from the Imperial General Headquarters. Incorporated into the story was the drawing of a “battle map” that specified obstacles, light and heavy machine guns, and assault routes. Another such article, “Bullets are Balls: Building the Provisions of Death or Injury in Battle, Girls as Nurses,” featured a photograph of actual IJA soldiers attacking in the field. The article explained in detail how to dig trenches, position troops, and commence an assault, noting that only by following the rules, including the roles of those predetermined to die and get injured, would they have an interesting battle (Yomiuri Shinbun 12 March 1939, 5).

Whatever the degree of adult control, adult proponents of such outdoor war games knew that, for these games to successfully engage children—to possibly instill in them the desire to become soldiers, or at least convince them of the inevitability of war—they needed to be playful, enjoyable, and as physical as possible. And so, among many other such accounts, the article “Win Through Strategy: A Fun Way to Play” (“Sakusen de katsu omoshiroi asobikata”) highlighted how well-crafted war games could provide both physical and strategic training. To that end, the article laid out many strategic details, including the importance of the two sides—“like the Japanese and the Chinese military, or the German military and the French military”—not knowing where the enemy might hide. The article put particularly emphasis on the fun of playing war in this way.

Though Japanese newspapers reported most often about Japanese children’s war games, they occasionally featured stories from beyond the borders of the homeland, particularly in other parts of Asia under Japanese colonial rule. On 2 June 1940 (4), for instance, the Yomiuri Shinbun reported on children’s war games played around the globe—though they suppressed the how and why of such war games and, indeed, never mentioned the ongoing adult war. They chose these other locales, based on political considerations, either to signal good relations with or lay claim on countries rich in natural resources that were of vital interest to Japan or to describe warm relations with the (child) populations of Japan’s colonies.

For example, less than six months after the Netherland Indies government surrendered to Japanese troops, the Yomiuri Shinbun enthusiastically claimed in a 20 September 1942 article (4) that, “despite their anti-violence traditions,” Javanese children “engaged in war play following commands uttered in Japanese.” Photographs featured boys clad only in shorts lying on their stomachs, holding rifles pointed at the invisible enemy in the distance. The text relayed how

The children of Java . . . have become friends with the (Japanese) soldiers . . . and are extremely mature. One never sees them argue with one another. The older ones wish nothing more than becoming as strong as Japanese soldiers when they grow up and, like Japan’s soldiers, help defend Asia.

The account of this “Indonesian war game” is just one of many such reports of games played throughout the Japanese empire.5 On 11 April 1943 (3), the Yomiuri Shinbun recounted in “Kodomo made heitai gokko” (Even [Korean] Children Engage in War Play) that this unexpected turn of events occurred as an effect of the Law on Special Volunteer Soldiers from Korea that had been introduced in 1938 to recruit Koreans into the IJA. Close to forty years after Korea’s sovereignty had been forfeited to Japan, the article referenced a Korean military official who enthusiastically explained that war play had become very popular on the peninsula. This had previously been unusual; Korean children had theretofore been raised by parents apprehensive of martial affairs—having grown up themselves with the once-prevalent Confucian worldview, which abhorred military violence and looked down on the warrior class. In an effort to explain that apprehension the article quoted the military official reciting an old proverb: “Ryōmin wa hei to narazu” (Good people do not become soldiers). Yet in the Chinese original the words were: “Hao nan bu dang bing, hao tie bu da ding” (A good man does not become a soldier, just like good iron is not made into nails). Despite this longstanding dismissive view of the military, the newspaper went on to speculate that the new “desire to play war games” had “naturally developed in children who saw their older brothers leave for the front lines.” It is important to note that the Yomiuri Shinbun did not address the question of which front line this referred to, and under whose command. Likewise, that Japan had made Korea a protectorate in 1905, then fully annexed the country in 1910, remained unmentioned; nor was it stated that the children in question had lived their entire lives under Japanese colonial rule. Instead, the article simply hinted at Japan’s “politics of assimilation,” emphasizing the popularity of playing war as a symbol of Japanese and Korean unity.

Though some photographs of field games organized and orchestrated by teachers and IJA personnel raise doubts as to whether or not children actually enjoyed them, some instructors who choreographed children’s war games in the prescribed fashion were apparently successful at making them fun—or at least we might be led to believe as much. Higuchi Ichiyō’s character in the 1896 novella Takekurabe (Child’s Play) says as much (Ujiie 1989:91), as does a boy in Akutagawa Ryūnosuke’s 1924 short story “Shōnen” (Youth) (Hanzawa 1980:29–30). Nakane Mihōko, a ten-year-old girl in elementary school, wrote the following in her diary for 4 June 1945:

Today we had fun evening drills. We left here this afternoon at 2:00 pm. We put on sedge hats and went off. It was very hot and seemed like summer. After some time, I could see Ishida-sensei strip down and put on a headband. We went there and rested for a while. Then we went to gather firewood. The third-section fifth graders already were there. We gathered firewood for some time and then returned. After a while we had a meal. The miso soup had dried tofu, strips of dried gourd, and two rice cakes in it. It was really, really delicious. After the meal, we practiced singing war songs. Then we played “Searching for the Jewel.” The “jewel” turned out to be Kobayashi’s apple, . . . . it wasn’t much fun for the rest of us. I searched as hard as I could, but in the end we were ordered to assemble. In our group it was Kobayashi alone. Then we were divided into attack and defense units and made war with each other (Samuel Hideo Yamashita 2005:285).

By the time the Imperial Japanese Army committed one of its most horrific war crimes, the Nanking Massacre of December 1937, no traces of concern about Japanese children’s war games remained—having given full ground to the promotion of such play as a meaningful instrument of preparation and training for war and life. In thus normalizing and naturalizing the progression from playing war to making war, Japan’s leaders, educators, and administrators had established a definitive path from childhood to soldierdom. No matter what meanings children had previously attached to such combative, physical, outdoor games, once the games were under almost total adult control they were to be played so as to develop their bodies and minds in line with the militarist and imperialist project taking shape around them. As IJA soldiers were to fight battles, children were to play war games. Despite the distance between one world and the other, children had become the foreshadows of soldiers; both were liminal characters. By all accounts, children’s war games would eventually result in children taking part in war as adults; and, well-trained and powerful, the soldiers’ war would in turn result in peace. Through their engagement in war (games), children and soldiers became infinite mirror images of one another.

The war children played between the end of the nineteenth century to the immediate postwar period—in school yards, streets, fields, and along rivers—involved role-playing, imitating, and reenacting past or ongoing conflicts in whatever ways their imagination, environs, and means allowed. During this time adult attitudes about such play dramatically shifted back and forth, varying between concerns about children’s safety and proper behavior on the one hand and notions about war games’ beneficial effects of maturity and battle-readiness on the other. Politicians, pedagogues, and parents also grappled with reconciling the concept of children being pure and innocent, in touch with their innermost feelings, with the stance that that precious innocence must also be shaped and controlled. War games and the various debates about them brought into one arena the debates many adults concerned themselves with: the proper ways of raising modern children, providing them with a safe environment, freedom, and care; the desire to build the nation and empire, and thus the need of a potent army; and the discovery of play as a pedagogical and political tool of teaching children to embrace the nation, empire, and war. More than anything, war games served as a mechanism to establish and reproduce war as an inherently human endeavor—and to ensure that children, boys in particular, became ever ready soldiers.

When ten-year-old Nakane made the above entry in her diary, girls just like her living in Okinawa no longer played such games—they were caught in the midst of the Battle of Okinawa and the Allied invasion of Japan. Less than two months later, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima (6 August 1945) and Nagasaki (9 August 1945), precipitating Japan’s unconditional surrender six days thereafter.

Only a few years later, in 1951, the Japan Teachers Union began to pursue a ban on war toys. In a declared effort to eventually provide children with possibilities for “good play” and “good playgrounds,” the Youth Division of the Police Agency conducted a first large-scale surveys regarding children’s play practices and child attitudes towards them. Among other results, the survey revealed that less that 3 percent of preschool and elementary school-age children proclaimed to often play war. An equally small portion of the over 200 respondents named war games, playing with and shooting pistols, stone fights, brawls, and playing in the street among the “bad games” they admitted to playing (Keishichō Shōnen-ka 1952:30-34).

In the wake of the Japan Teachers’ Union’s attempts to get “war toys” banned, newspapers returned to their early-twentieth-century tone of grave concern regarding such games. On 28 October 1952, for example, the Yomiuri Shinbun printed a reader’s letter expressing indignation and worry at the sight of children playing war in the streets (see fig. 11).

|

Titled Kondō Isami and Kurama Tengu (Kondō Isami to Kurama Tengu, 1955), this is one of many photographs Domon Ken (1909–1990) shot of “chanbara,” or “samurai-style swordplay fighting,” and other improvised play of children in the aftermath of war. Previously a prominent photo journalist who helped Japan’s war effort, Domon remains one of Japan’s most renowned photographers. Printed with the kind permission of the Domon Ken Kinenkan. |

Recently, on the way home, I ran into a few children who engaged in war play. Seven, eight children were at it. The biggest and strongest-looking was their commander and they were imitating soldiers down to the marching style. . . . It’s the responsibility of parents and teachers to raise children and have them play peaceful, bright kinds of games (28 October 1952, 3).

One can understand this reader’s concern. And yet, the children he described had played all their lives in the shadow of militarism, first of a Japan at war and, later, of the occupation by the Allied Forces, which effectively lasted until the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952. In addition, they had been brought up by parents for many of whom military play was a deeply ingrained component of nationalism and pride. This reader’s concern, and the newspaper’s printing of it, thus encapsulates the contested angles of the debate—as well as how children were trapped at its center, pawns of a much larger game.

This is an abridged and revised version of chapter 1 of Sabine Frühstück’s new book, Playing War: Children and the Paradoxes of Modern Militarism in Japan. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.

Bibliography

Note: The place of publication for Japanese works is only noted when it is not Tokyo.

Akiyama Masami, ed. 1991a. Shōgakusei Shinbun ni miru senjika no kodomotachi (Children at war as viewed by The Elementary School Pupils’ Newspaper). 3 vols. Vol. 1. Nihon Tosho Sentā.

Amano Ikuo. 1990. Education and examination in modern Japan. University of Tokyo Press.

Ambaras, David R. 2006. Bad youth: Juveline delinquency and the politics of everyday life in modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bieber, Hans-Joachim. 2014. SS und Samurai: Deutsch-japanische Kulturbeziehungen 1993–1945. Munich: Iudicium Verlag.

Eppstein, Ury. 1987. “School songs before and after the war: From ‘Children tank soldies’ to ‘Everyone a good child’.” Monumenta Nipponica 42 (4):431–447.

Frühstück, Sabine. 2003. Colonizing sex: Sexology and social control in modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hanzawa Toshirō. 1980. Dōyū bunka-shi dai 4-kan (Cultural history of children’s games vol. 4). Tōkyō Shoseki.

Inagaki Tadahiko. 1986. “School education: Its history and contemporary status.” In Child development and education in Japan, ed. Harold Stevenson, Azuma Hiroshi, and Hakuta Kenji, 75–92. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Kami Shōichirō, ed. 1977. Nihon kodomo no rekishi 6 (A history of children in Japan 6). Daiichi Hōki Shuppan.

Keishichō Shōnen-ka. 1952. Shōnen no asobi to dōtoku ishiki no hattatsu (Youth play and the development of moral conscience). Keishichō Bōhanbu Shōnen-ka. In In Sōsho Nihon no jidō yūgi dai 25-kan (Collection of books on Japanese children’s play vol. 25), ed. Kami Shōichirō, 1-102. Kuresu Shuppan.

Kinder, Marsha. 1993. Playing with power in movies, television, and video games: From Muppet babies to teenage mutant Ninja turtles. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kracauer, Siegfried. 1960. Theory of film: The redemption of physical reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Manabe Noriko. 2013. “Songs of Japanese schoolchildren during World War II.” In The Oxford handbook of children’s musical cultures, ed. Patricia Shehan Campbell and Trevor Wiggins, 96–113. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moriyama Shigeki and Nakae Kazue. 2002. Nihon kodomo-shi (A history of children in Japan). Heibonsha.

Morse, Edward Sylvester. (1917) 1978. Japan day by day, 1877, 1878–79, 1882–83. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Okano, Kaori, and Motonori Tsuchiya. 1999. Education in contemporary Japan: Inequality and diversity. Cambridge University Press.

Piel, Lisbeth Halliday. 2017. “Outdoor Play in Wartime Japan.” In Child’s Play: Multi-sensory histories of children and childhood in Japan, edited by Sabine Frühstück and Anne Walthall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Roberts, Luke Shepherd. 2012. Performing the great peace: Political space and open secrets in Tokugawa Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Tsuganesawa Toshihiro. 2006. Shashin de yomu Shōwa modan no fūkei (Reading the modern landscape of the Shōwa era in photographs). Kashiwa Shobō.

Ujiie Mikito. 1989. Edo no shōnen (Youth during the Edo period). Heibonsha.

Watanabe Fukuo. 1914. “Kodomo no sensō gokko.” Fujin to Kodomo 14 (11): 486–490.

Yamashita, Samuel Hideo. 2005. Leaves from the autumn of emergencies: Selections from the wartime diaries of ordinary Japanese. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Yanagida, Kunio. 1957. Japanese manners and customs in the Meiji era, trans. Charles S. Terry. Ōbunsha.

Yoshida Yutaka. 2002. Nihon no guntai: Heishitachi no kindaishi (The Japanese military: A modern history of soldiers). Iwanami Shoten.

Notes

Hari Kumar and Ellen Barry, “India, U.S. and Japan begin war games, and China hears a message.” The New York Times, 10 July 2017. Kai Strittmatter, “Chinas Armeechefs erklären einem Handyspiel den Krieg.” Der Standard, 8 August 2017.

Kondō Juhaku, ed., Kinsei fūbun-mimi no aka. Tokyo: Seiabō, 1972, 163; quoted in Minami Kazuo 1989[1980], 26–27, trans. by M. William Steele and Robert Eskildsen, 1989.

Sociologist, cultural critic, and film theorist Siegfried Kracauer (1960:171) wrote of “childlike omnipotence” in a similar context. For Kracauer, childlike omnipotence was what took hold of the audience in the movie theater. In his view, the moviegoer magically rules the world onscreen in the same way that a child at play imagines: “by dint of dreams which overgrow stubborn reality.”

This further formalization of military-style training at schools was not an isolated move. It was made against the backdrop of new universal suffrage for men—along with the implementation of the Public Security Preservation Law, designed to contain the democratizing and thus potentially destabilizing effects of those voting rights.

The documentary Japanese School Children and War Games (Extracts from Japanese Newsreels), a twenty-two minute 35mm short film shot in 1942 with Japanese and Indonesian voices, shows Japanese children at school engaging in various activities, including a mock battle. Source: Film ID F06931 (courtesy of the Australian War Memorial). accessed on September 11, 2015.