Introduction

The history of the “comfort women” (ianfu) concerns women and girls from Korea, China, the Philippines, and other parts of the Japanese empire who were forced into sexual slavery in Japanese military-run or sponsored stations during the Asia-Pacific War.1 Knowledge of this episode in human history is above all the result of the courage and persistence of the victims who have testified and chronicled their experiences, but also of the work of researchers, journalists, and concerned citizens inside and outside Japan, who investigated the facts and published their findings despite efforts by history denialists to intimidate them. For example, their experience is well documented in memoirs by former “comfort women,” such as South Korean Kim Hak-sun, the first woman to come forward in 1991, and Filipina comfort woman Maria Rosa Henson, who wrote a memoir describing her experience.2 Activists and NGOs, such as the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Sexual Slavery by Japan, recorded testimonies by former “comfort women.” In 2000, survivors from more than a dozen countries gathered and gave testimonies at the International Women’s War Crimes Tribunal held in Tokyo.3 Works by scholars and journalists were also significant. For example, historians such as Yoshimi Yoshiaki discovered Japanese military archival documents describing the ”comfort woman” system, and journalists such as Uemura Takashi covered the story of Kim Hak-sun for the Asahi Shimbun. Yoshimi, Uemura and others were subjected to vicious attacks by Japanese neonationalists.4

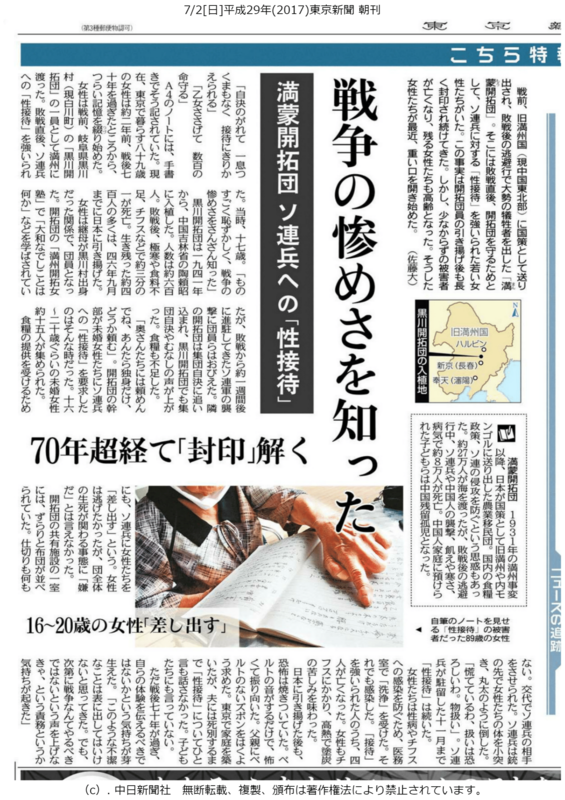

In 2017 the “comfort women system” remains a source of political conflict between Japan and former colonies and occupied areas, especially Korea and China, and the subject of a vast contentious literature. With the comfort women issue and other wartime violence against women being debated, survivors of other forms of wartime sexual violence began to speak out. The recent Tokyo Shimbun newspaper article translated here tells a number of stories that have rarely been told, including the story of the self-sacrifice and trauma of Japanese adolescent girls and unmarried women in Manchuria following Japan’s 1945 defeat. Soviet Red Army soldiers entered Manchuria at the very end of the war on August 8, 1945, occupying the area following Japan’s surrender and capturing Japanese soldiers, many of whom faced years of imprisonment in Siberia. This article describes the fate of the young women of the Kurokawa Settler Community who were dispatched by their own community to provide sexual services to Soviet Red Army soldiers in hope of assuring the survival of the local community and safe passage to Japan in the wake of Japan’s defeat. More than half a century would pass before the first aging survivors began to tell their stories to the next generation.

This article reveals the decades-long silence surrounding the sacrifice of the young women for their community. The weight of community pressure to maintain silence about their sacrifice meant that the issues remained suppressed even after many of the victims passed away.

The involvement of family and community members in the case of the Kurokawa Settler Community also complicates the picture of military sexual slavery and sex trafficking. The remorse of a few of the remaining elderly settlers and their children, and their gradual, public recognition today, nearly three-quarters of a century later, of the sacrifices made by the adolescent girls and young women was presented in a Tokyo Shimbun article and an NHK documentary that aired on August 8, 2017, on Japan’s public broadcasting station NHK: “Kokuhaku: manmō kaitakudan no onna tachi” (Confession: Women of the Settler Community of Manchuria and Mongolia).5

The Tokyo Shimbun article introduced here is not the only coverage of the Kurokawa Settler community case. For example, researcher Inomata Yūsuke, who is cited in the article, has studied the case since 2005, conducting interviews with former members of the Kurokawa Settler Community.6 Nonfiction writer Hirai Miho also conducted investigative journalistic work and interviewed the survivors and others in the community, and published her articles in such popular media venues as the women’s magazine, Josei Jishin (Oct 4, 2016), and more recently, in an online magazine, Gendai Business.7 Their groundwork led to further work, including the Tokyo Shimbun article introduced here, and the NHK documentary mentioned above. These works by scholars and journalists play crucial roles in highlighting the forgotten history and the voices of the aging survivors, just as researchers working on “comfort women” have long been doing. (JE)

I Learned about the Wretchedness of War: Women Settlers’ ‘Sexual Entertainment’ of Soviet Red Army Troops in Postwar Manchuria

The Settler Community of Manchuria and Mongolia (Manmou Kaitaku Dan) was the home of many Japanese in the years 1920-45. In accordance with national policy the settlers were sent to Manchukuo (in present northeastern China). Along with their repatriation after Japan’s defeat in the war there were a huge numbers of victims. It was there, in the immediate aftermath of the war, with the aim of protecting the settler community, that young women were forced to provide “sexual entertainment” for Soviet troops. The facts of this story remained concealed long after the settler community members’ repatriation. Although more than a few of the victims have died, and the remaining victims are elderly, these women have recently begun to reluctantly tell their story.

“We had given the slip to [compulsory] suicide, but before we had even caught our breath from that narrow escape, we were converted into entertainers.”

“We will save the lives of hundreds of people by sacrificing our young maidens.”

These words were written by hand in an A4-size notebook. About two years ago an 89-year-old woman who now lives in Tokyo began to put down on paper her bitter recollections, 70 years after the War ended.

She had emigrated to Manchuria before the War as a member of the “Kurokawa Settler Community” from Kurokawa Village (which now is part of the town of Shirakawa-cho) in Gifu Prefecture. Right after the end of the War, she was forced to serve soldiers of the Soviet Red Army as a “sexual entertainer.” She was 17 years of age at the time. “I felt the most intense shame and learned of the wretchedness of war in an absolutely merciless way.”

The Kurokawa Settler Community settled in Taolaizhao (between Changchun and Harbin) in Jilin Province, China in 1941. The Community consisted of some 600 people. After Japan’s defeat, approximately one in three people died from extreme cold, starvation, typhoid fever, or other conditions. Most of the approximately 400 people who survived repatriated to Japan by September of 1946.

The 89-year-old woman had become a member of the Community due to the fact that her stepmother was from Kurokawa Village. In the settler community’s “Manchuria Settler Women’s School” she had been taught “what is expected of a traditional Japanese woman.” But one week after defeat, the community members were filled with fear as they were suddenly caught off guard by news that the Red Army had advanced into and occupied Manchuria. A neighboring settler community had been cornered into committing collective compulsory suicide (shūdan jiketsu), and there were those in the Kurokawa Settler Community who also felt they had no choice but to end their lives in this way.8 Their stores of food had run out.

“You know, we can’t ask married women to do this. It’s up to you, the single women. Please, you are our only hope.” It was then that the Settler Community leaders asked the unmarried women to “sexually entertain” Soviet Red Army troops. Approximately 15 girls between the ages of 16 and 20 were gathered together.

In order to receive help from the Soviets, including food provisions, the community “offered” the girls to the troops. The girls wanted to escape, but with the lives of everyone in the community in jeopardy, they had to cooperate.

In one room of the Settler Community’s shared facilities, futons were spread on the floor side by side without any partitions between futons. The girls were assigned to Red Army soldiers one after another. The Soviet soldiers jabbed the girls with the tip of the barrel of their guns and knocked them down like so many logs.

“We felt panic and confusion. The way they treated us was terrifying. We were treated like mere physical objects.” The “sexual entertainment” continued until November while Red Army troops were stationed there. In order to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and typhus, the girls were “irrigated.” They contracted such diseases anyway. Among the girls who were forced to provide “entertainment,” four died. They caught typhus and suffered unspeakable agonies from high fevers.

The terror was still burned into her after she returned to Japan. Even the sound of a belt was enough to make her turn about in fear. She asked her father to wear beltless trousers. She raised a family in Tokyo but never said a word about the “sexual entertainment” until after she and her husband were separated by his death. She did not even tell her children about it.

70 years after the War ended, the feeling sprang up in her heart that she should tell about her experience. “There was a time when I believed that I should never speak of an experience as filthy as this. But gradually I came to feel a sense of obligation, to let out a cry of protest that war is wrong.”

“I Want It to Be Remembered That It Was Due to Our Sacrifice That They Were Able to Return”

We do not know what sort of negotiations took place back then between community leaders and the Red Army. The officials did not offer any explanation even after everyone had been repatriated. What we did hear—from members of the community—was that the women who had suffered had been slandered by the settler community. It was outrageous.

“What deep sadness we felt! I want it to be remembered that it was our sacrifice that allowed others to return.”

Another woman who suffered (now 91 years old and living in Gifu Prefecture) exclaimed, “We had such an urge to run away! The person in charge of our settler community requested of me: ‘Your turn has come. I’m sorry. But go.’ I felt afraid, but I knew that we needed to return to Japan, and this was the time for me to help everyone, even if something scary would happen to me.”

She contracted a sexually transmitted disease, but later revealed everything to the man who eventually became her husband. That was after she returned to Japan. She even handed him her medical certificate. They moved to another part of Gifu Prefecture and she worked as hard as she could.

“We never imagined that we could live this long. This sort of history, too, is important. It will be remembered even after we are dead.” She says that now there are only three survivors remaining.

Ms. Yasue Kikumi (now 82) of the Kurokawa Settler Community was 10 years old when the War ended.

She said, “We cannot forget the noble women who saved us.”

In 1981 the “Former Manchukuo Kurokawa Division Village Survivors Society” erected a “Monument to the Maidens” to enshrine the spirits of the women who had been “sex entertainers” and who were no longer among the living. Ms. Yasue has prayed there many times. Not many people, not even locals, know how the Monument came to be there.

Although Ms. Yasue was a small child at the time, she knew about the “sex entertainers.” While helping heat up the bath with chopped wood and feeling excited about being able to take a bath, her mother scolded her saying, “With the older girls out there saving us by going to where the Red Army soldiers are, you put your heart and soul into heating up that bath.”

When Ms. Yasue went to a clinic to help with the treatment of her younger sister who was suffering from malnutrition, she learned that the older girls were being “irrigated.”

After they returned to Japan, the Village Survivors Society held memorial services. But the “sex entertainers” were not spoken of openly, and in the written records of the Settler Community, no mention was made of them.9

It was the death of one of the victims that moved Ms. Yasue to resolve to pass this history on to future generations. A 91-year-old woman with whom she had been friends requested of Ms. Yasue just before she died, “I want you to tell people about our sacrifice, people who don’t know about it.” Later, Ms. Yasue began to serve as a storyteller, giving talks about the sex entertainers at places such as the Manchukuo Settler Peace Memorial Hall (in Achi Village, Nagano Prefecture).

Changes in the atmosphere in the Survivors Society also supported Ms. Yasue’s efforts. In 2012 Mr. Fujii Hiroyuki, a second generation member of the Community born after the War, assumed responsibilities as the new chair of the Survivor’s Society. Mr. Fujii, whose four older brothers and sisters died in Manchuria, thought deeply about the importance of telling the community’s history.

“What I can do is tell the next generation about it. That is another way that we can bring peace of mind to the victims who have passed away, just like holding a Buddhist memorial service.”

Inomata Yūsuke, a researcher at the non-profit organization “Institute on Social Theory and Dynamics” (“Shakai Riron Doutai Kenkyuujo”) in Hiroshima City, has done research on war-time sexual violence and interviewed former members of the Kurokawa Settler Community.10 He says, “The former members of the Community had a strong sense that this was ‘the Community’s shame,’ so they have not yet been able to provide details about exactly how this whole thing came about. But with the comfort women issue and other such issues being debated, and they themselves having reached old age, they have become aware of the need to preserve these memories for the sake of history.”

The 89-year-old woman mentioned above spoke for three hours without drinking any water at all, as if she was saying “I am leaving behind my will.” In her words, “War, you know, is something that hurts the weak. People must never use weapons, no matter how many years it takes to come to an agreement.”

In one woman’s notebook, these words had been set down in writing:

Even after 70 years

Facts that cannot be erased

Absolutely opposed to militarism

|

|

Related articles

Hayashi Hirofumi, Government, the Military and Business in Japan’s Wartime Comfort Woman System

Ichikawa Miako, Child survivor of forced mass suicide in Manchuria still loves hero who saved her

Mori Takemaro, Colonies and Countryside in Wartime Japan: Emigration to Manchuria

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Addressing Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’ Issue From an Academic Standpoint

Mariko Tamanoi, Victims of Colonialism? Japanese Agrarian Settlers in Manchukuo and Their Repatriation

Rowena Ward, Left Behind: Japan’s Wartime Defeat and the Stranded Women of Manchukuo

Notes

“Fact Sheet on Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’,” Asia-Pacific Journal Feature, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 13:19:2 (11 May 2015).

Maria Rosa Henson, Comfort Woman: Slave of Destiny (Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 1996).

The full documentary of the tribunal, Breaking the History of Silence, is available here on youtube.

Yoshimi’s works include Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II, trans. Suzanne O’Brien (Columbia UP, 2002). See also, “Reexamining the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue: An Interview with Yoshimi Yoshiaki.” Introduction by Satoko Oka Norimatsu. For Uemura’s coverage of Kim Hak-sun, see Uemura Takashi, “Labeled the Reporter Who ‘Fabricated’ the Comfort Woman Issue: A Rebuttal.”

Inomata, Yuusuke. “Homo sōsharu na sensō no kioku wo koete – ‘manshū imin josei’ ni taisuru senji sei bōryoku wo jirei to shite.” (Beyond the homosocial memory of the war: a case study of wartime sexual violence against ‘settler women in Manchuria’) Gunji Shigaku, 51(2), 2015:94-115.

Hirai, Miho. “Wasuretai ano ryōjoku no hibi, wasure sasenai otome tachino aietsu” (We want to forget the days of humiliation, we won’t let the maidens’ tears be forgotten) Josei Jishin, October 4, 2016. Hirai Miho, “Sorenhei no ‘seisettai’ wo meijirareta otome tachi no 70nen go no kokuhaku” (Testimonies 70 years later by maidens who were ordered to “sexually entertain” the Soviet soldiers) See part 1 here and part 2 here.

In some cases Japanese authorities pressed Japanese settlers as well as soldiers to commit suicide rather than surrender.

In 1981 the Settler Community printed a commemorative booklet (“kinenshi”) to record their history. In a section that one man wrote, he gave the “entertainers” some recognition, saying that the settlers owed their lives to the girls who entertained the Soviet soldiers, but he only spoke of their serving the soldiers various foods, such as a cooked pork dish. (See section 40:40 to 41:30 of the documentary here).