Abstract

With the withdrawal of British troops from the Australian colonies in 1870, a sense of strategic exposure crept through the colonies over the following decades. This feeling of exposure was conspicuously felt in the New Hebrides (modern Vanuatu), where French settler intrigues threatened the Pacific “island wall” the Australian colonies increasingly hoped would guard against the “Yellow Peril” of an expansionist Japan. However, Whitehall found that the growing Australian-French settler antagonism over the New Hebrides interfered with its global imperial policy. Britain was forced to balance competing interests between its primary Pacific dominion and its emerging European ally. The move towards an eventual Anglo-French New Hebrides Condominium (1906), led to a distinct bifurcation of Anglo-Australian imperial policy in the Pacific. It also resulted in the physical, cultural and social decimation of native society.

Keywords: New Hebrides, Australia, French Colonialism, Japan, Pacific, British Empire, Anglo-French Condominium, Sub-imperialism

“His Majesty’s Government regards the New Hebrides as quite unimportant from the point of view of defence, and do not consider that their occupation would in any sense be a strategic gain.”1 This matter of fact response was forwarded to Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia, Alfred Deakin, by Australian Governor-General Henry Northcote in November 1905 at the height of a decades-long Australian-French settler rivalry over the future control of the archipelago.

The New Hebrides, modern Vanuatu, could not be any further from the main centers of British imperial power at the time, and most certainly not any further from its core imperial interests. Indeed, this island chain lying 2,500 km northeast of Sydney in the middle Southwest Pacific, held little economic and even less strategic importance for Whitehall. It did not control a chokepoint of Far Eastern trade like Singapore, nor protect the approaches to British India like Aden. The New Hebrides were just another set of Melanesian islands where little more than copra could be cultivated, and Whitehall had historically tried everything in its power to resist being dragged into official colonial administration in the region.

While “quite unimportant” to Whitehall policy makers during the high tide of the British Empire, Vanuatu would emerge as an important well-spring of Melanesian nationalism during the era of decolonization following World War II. By the 1960s, land disputes between native groups and European settlers, a common dynamic of revolution in the decolonizing world, spurred the foundation of one of the earliest Melanesian nationalist movements in the region. Under the leadership of Jimmy Stevens, known to his followers as “Moses”, the Nagriamel conservative-traditionalist movement and the socialist Vanua’aku Pati party of Anglican Fr. Walter Lini emerged as leaders calling for Melanesian self-determination. As the two parties competed for influence throughout the 1970’s amidst the backdrop of broader decolonization in the Pacific, British and French interests again clashed.

British policy makers, happy to rid themselves of the expense of economically and strategically “unimportant” Pacific colonies, hoped that Vanuatu’s independence would coincide with that of the other British colonies in the region. However, French interests, which opposed decolonization in French Polynesia and New Caledonia, actively undermined the independence movement. French interests supported Stevens’ Nagriamel movement, which sought a prolonged transition to independence, while the British supported Lini. In the end, Lini’s Vanua’aku Pati triumphed – with Lini becoming Vanuatu’s first prime minister in 1980. An effort to establish a separate French-backed state on Espiritu Santo by Stevens was put down with the support of Papua New Guinean troops.2

Lini’s government, which many in the West viewed as Communist-aligned, pursued an independent Melanesian socialism which sought to blend Western socialist thought with traditional forms of the Melanesian economy, culture and society (known as kastom).3 This doctrine gained admirers among Melanesian populations throughout the region and continues to be advocated by pro-independence parties in French New Caledonia. Lini also sought stronger ties with other Melanesian nations, like Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, laying the basis for the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG).4 Lini also remained a vocal critic of continued French colonial occupation in the region, and Vanuatu emerged as a major supporter of Melanesian nationalists in New Caledonia calling for the termination of French nuclear testing during the 1980s.5 In this role Vanuatu continues to exercise a quite important regional leadership role, specifically through the MSG, advocating for Melanesian self-determination in places like New Caledonia and West Papua.6

|

Map of the modern Southwest Pacific with inset of Vanuatu (former New Hebrides)7 |

However, a century before Vanuatu’s independence, this “quite unimportant” island chain gave rise to a dramatic reorientation of British imperial policy during the Edwardian years. In the New Hebrides, British foreign policy’s dramatic shift away from its Pacific colonies and toward Europe would accelerate – diverging from Australia and increasingly converging with that most traditional of foes, France. In the signing of the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides in 1906, Britain would formally subordinate the desire of its Pacific settler colonies to its alliance with France.

Not surprisingly, given the “unimportance” of the New Hebrides for the British Empire, the historiography of the region in light of its imperial relevance is sparse. Most macro-imperial histories fail to even mention the New Hebrides or the Anglo-French Condominium.8 In Australian historiography the New Hebrides are often little more than a footnote. Only amongst Australian defense works, such as Neville Meaney’s The Search for Security in the Pacific, 1901-14, do the New Hebrides have a place at the table.9 By far the best accounts of the New Hebrides are from the French perspective but still fall victim to the nationalist narrative.10 The intent of this paper is to bring the Franco-Australian settler antagonism over the New Hebrides out of obscurity and define the role this small, “quite unimportant” chain of islands played in accelerating Britain’s turn from empire in the Pacific.

The end of British Hegemony in the Asia-Pacific

The Franco-Australian antagonism over the New Hebrides, which reached a fever pitch by 1905, should be viewed in the context of a decades-long shift in the status quo of the Asia-Pacific, which in turn was shaped by the evolving strategic situation in Europe following the unification of Germany. The aggressive rise of German Weltpolitik and naval projection under the influence of nationalist elements beginning in the 1880s, forced a reevaluation of British imperial policy that sent significant ripples through the Pacific. The Second German Naval Law of 1900, which was spearheaded by arch-Alldeustchen Admiral Tirpitz, called for the doubling of the German Navy by 1912. General Bernhardi, a leading German strategist, would state that the Kaiserliche Marine was created specifically to wage a bold and energetic campaign against British commerce.11 The bellicose posturing of the Germans during the Moroccan Crisis and the Algeciras Conference (1905) fully confirmed suspicions that Britain itself was under an unambiguous threat for the first time since Napoleon.

The Foreign Office, in close coordination with the Admiralty, acted with foreseeable alacrity in countering this German threat as it continued to develop towards the turn of the twentieth century. The Anglo-Japanese Treaty (1902) was signed, the Entente Cordiale (1904) was codified with France, and the Admiralty requisitioned all “non-essential” Royal Navy ships from the colonial-based squadrons to reinforce the newly constituted home fleet at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland. The Pacific security brought by Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War and the renewal of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1905 allowed the Admiralty to target the Pacific squadrons for reduction while leaving regional security to their Japanese allies. By 1906, five British battleships had left the Pacific.12 This worked out to approximately one-third of all British ships in Australasian waters removed in less than a year.13 This reduction, which capped nearly two decades of creeping British disengagement from the Southwest Pacific, inflated the sense of strategic vulnerability of Britain’s settler colonies in the region.

Policy makers in the six self-governing Australian colonies (New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia) became increasingly anxious about declining British military support after the formal withdrawal of British soldiers from the continent in 1870. This sense of abandonment was further exacerbated by the meteoric rise of Japan. An unabashed jingoism, which was codified in various anti-Asian immigration policies and merged into the official “White Australia” policy after the federal unification of the colonies in 1901, rejected Asian immigration into the colony and saw Japanese military and industrial modernization as a great “Yellow Peril” to Anglo-Saxon settlement in the region. But any Japanese-excluding “Monroe Doctrine for Australia”, as Alfred Deakin later termed it, was solely reliant on British hegemony in the region.14 And as Britain withdrew and Japan rose, the balance of power slowly turned in favor of the Rising Sun.

By 1905, the Australian self-governing colonies had been united as the Commonwealth of Australia (1901) in light of Britain’s withdrawal from the region, while the Japanese secured an undisputed position of regional primacy. Over the preceding three decades, the Japanese had militarily defeated the other independent Asiatic power, Qing China (1895), and their primary Eurasian rival, Russia (1905). The Imperial Japanese Fleet now was quantitatively superior to any other fleet in the region and dwarfed the British Royal Navy’s Australia Station.15 The Japanese population was twelve times that of the Commonwealth of Australia and her GDP was three times as large.16 Japan had annexed the Ryukyu Islands (1879) and Formosa (1895) and incorporated the Empire of Korea as a protectorate (1905). The colonization of Formosa expanded the Japanese Empire 2000 km further south toward the Australian continent.

Moreover, the new Japanese position not only alarmed Australia. The United States came to view Japan as a likely adversary in the Asia-Pacific and began reorganizing its military and foreign policy to check continued Japanese expansion, which increasingly dovetailed with Australian security objectives. Japanese victory over Russia in 1905, crushing the Russian Baltic Fleet at the Battle of Tsushima Straits and capturing Port Arthur, marked a watershed moment in the reordering of the entire Asia-Pacific balance of power.

In response to Japan’s new geopolitical preeminence in the Western Pacific, and despite the assurances of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, the Commonwealth government sought to hastily buttress its defense against possible Japanese aggression. Key to this new colonial defense was Deakin’s efforts in 1905 to close the “island wall” between Australia and Japanese possessions north of the equator, a concept which had increasingly shaped Australian defense policy since the late 1870s. By painting Melanesia and Polynesia, from New Guinea to Samoa, British Red, the Australian colonies hoped to create a strategic tripwire that would keep Japan from crossing the equator. In 1905, with Japan’s regional strength secured, the Commonwealth frantically pushed for British annexation of the New Hebrides – the final unclaimed section of the “island wall” – before Japan turned her newfound capabilities toward Australia.

Franco-Australian antagonism in the New Hebrides

Tensions between French settlers and British settlers from the Australian colonies in the New Hebrides initially arose in response to antagonisms beginning in the 1870s. Economic competition between the settler blocs was growing and it was presumed that either Britain or France would seek to annex the New Hebrides. French settlers, predominantly from New Caledonia, were unified in support of French annexation. However, considerable differences of opinion on which colonial power should annex the islands emerged within British settler circles. British settlers from Fiji on Efate (Sandwich Island) actually demanded French annexation in 1875-76, given the strong French support for settler over native interests, while the movement for British annexation was led by John Paton, a Methodist missionary representing the British settlers from the Australian colonies.17 The fact that British settlers from Fiji, often viewed as representing the interests of Whitehall, generally supported French annexation of the New Hebrides against the wishes of their Anglo-Saxon cousins from the Australian colonies remained a point of tension between London and the Australian colonies throughout the period of conflict.

Public opinion across the Australian colonies certainly supported the calls for British annexation, particularly in light of Britain’s increasing disengagement in the region. A letter to the editor of the Melbourne Argus stated that British annexation was needed “to check French designs upon the New Hebrides.”18 By October 1877, an official petition was sent to Whitehall from the British Australian colony of Victoria requesting annexation and the Sydney Morning Herald blatantly supported this aspiration.19 By November the powerful Presbyterian lobby in the colony of New South Wales, appalled at the thought of the New Hebrides metamorphosing into a New Caledonian-esque French penal colony, appealed directly to Queen Victoria for a swift hoisting of the Union Jack over the archipelago.20

The growing raucous calls for annexation within the Australian colonies alarmed French settlers in the New Hebrides. Responding to an official request from the French Foreign Office, Georges d’Harcourt, Ambassador at the Court of St James (1875-79), wrote to the British Foreign Office for assurances of neutrality in January 1878.21 In February the French received a response from Lord Derby, British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (1874-78), who was pleased “to inform Your Excellency that it is not the intention of Her Majesty’s Government to…modify the independence which the New Hebrides at the present possess.”22

The news of this “self-denying ordnance” would not reach the Australian colonies until June 1878, and laid the foundations for decades of mistrust between policy makers in the Australian colonies and the Commonwealth of Australia, and Whitehall from 1901.23 However, the response did not quell Franco-Australian settler competition in the islands and, by the early-1880s, the intrigues of a naturalized French settler of Anglo-Irish descent were causing increasing anxiety in the Australian colonies.

John Higginson, a well-to-do Anglo-Irish resident of New Caledonia, founded the Compagnie Calédonienne des Nouvelles-Hébrides in 1882. Originally constituted with £20,000 capital, the company aggressively purchased real estate in what became one of the greatest land speculation efforts in the colonial Pacific. The company soon controlled nearly 100,000 hectares in the New Hebrides and was viewed by the Australians as a back door for a de facto French annexation of the archipelago.24 By July 1883, Australian suspicions were validated by a major exposé in The Argus. Not only was there a major effort led by Higginson’s Compagnie Calédonienne to ensure French annexation, directly seeking to capitalize on its land speculation, the company’s largest financiers were the British firms Morgan and Nephew and Morgan Brothers. The fact that British capital was supporting French attempts to destabilize Australian security further undermined the Australian colonies’ confidence in Whitehall.

Higginson’s efforts did not materialize without provocation. Victoria Premier James Service had emerged as the leading public advocate from the Australian colonies demanding British annexation – particularly during the debacle over the German annexation of Northeastern New Guinea. There was a scramble for colonies in the Pacific, and the British had best lay claim to the remaining unincorporated islands in the region or the security of the Australian colonies would be compromised even further. Tensions with France were particularly high in the aftermath of Britain’s seizure of Egypt in 1882, and the possibility of a hostile French naval squadron in Australasian waters was not reassuring to any of the Australian colonies.

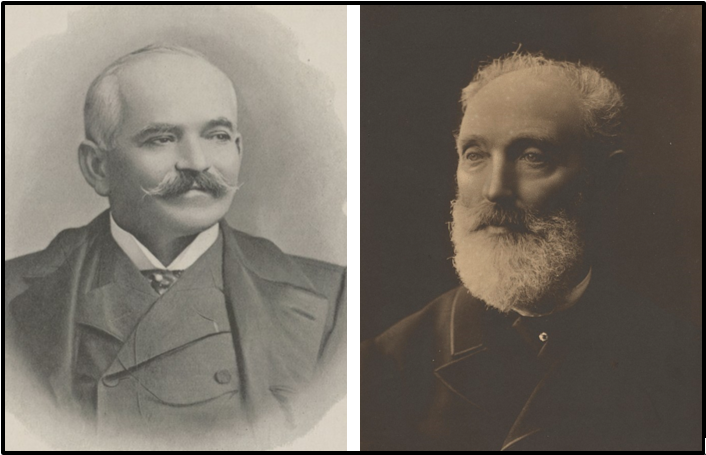

|

John Higginson (left) and James Service (right)25 |

The French settlers responded to Service’s agitation with a major gathering in Noumea (New Caledonia) in 1883 where Service’s support was termed an act in “violation of our rights” and “a mortal blow” to French interests in the region.26 The audience solicited Mons. Pallie de la Barriere, Governor of New Caledonia, with a resounding call to bolster the tricolor that “has been planted in the New Hebrides.”27 By September reports were arriving in Australia from Paris that Higginson and Morgan were attempting to import French convict labor to the New Hebrides to create an overwhelmingly demographic majority for the French. And rumors were rife throughout Australian colonial policy circles about an impending French annexation.28

The Compagnie Calédonienne, refusing to ease its provocative quasi-official speculation, continued to aggressively purchase land throughout the New Hebrides as tensions simmered. By 1884, Higginson’s company controlled the vast majority of cultivated land, further exacerbating fears in the Australian colonies of a de facto annexation. Higginson, ruthless in his quest to monopolize trade, brazenly undercut investors of the recently founded Anglo-Australian Company on Malekula in late 1884. Arriving with French marines, Higginson intimidated the local chiefs into nullifying previous contracts with the Anglo-Australian Company and selling to Higginson exclusively.29 With French marines supporting settler land grabs, the specter of French annexation elevated to a distinct likelihood. The Australian colonies had had enough and by late 1884 an official request was sent to London from Premier Service on behalf of all the colonies, stating that they were ready to meet “any expenses in taking possession of the archipelago” as long as Britain hoisted the Union Jack.30 It is interesting that this offer to take over full administrative and fiscal responsibilities was not replicated in British New Guinea (occupied in 1884) and arguably of far greater strategic importance, until 1902. Thus, it appears that the importance of the New Hebrides for Australian defense had taken center stage by the mid-1880s.

The British Foreign Office would again find itself pulled into the Franco-Australian settler struggle. Much to their annoyance, Britain would invest significant resources in something utterly worthless to Whitehall. Even as late as 1914, the New Hebrides were destitute when contrasted with comparable colonial possessions in the Pacific. British total exports from Tonga reached £240,104 by 191131, Fiji reached £1,425,940 by 191332, and French exports from New Caledonia peaked in 1914 at 15,468,607 francs33 (£608,521).34 This compared to less than £121,000 in total exports, French and Anglo-Australian, from the New Hebrides in 1914. However, the archipelago’s unimportance to the Foreign Office did not deter the French, with support of the British settlers from Fiji, or the Australian settlers, from continuing their calls for annexation. By 1885 the Foreign Office was obliged to directly approach the French government to resolve the quarrel before some spark ignited a violent confrontation between the two parties.

During the 1885-1887 negotiations over the New Hebrides, neither the Ministère des Affaires étrangères nor the Foreign Office called for direct annexation. Indeed, both governments were even open to sidelining the interests of their own settlers to gain more important diplomatic concessions elsewhere. Although he was awarded the Légion d’honneur for his work in early 188735, the French stated that they would gladly sacrifice Higginson’s claims to the New Hebrides for British concessions in Tahiti and Newfoundland. Concurrently, Whitehall was not wholly opposed to French control over the archipelago, but sought to restrain the rowdy Australian colonial lobby before some major incident occurred.36 Though it should be noted that the British still supported the Australian colonies’ concerns over French settler calls for annexation, and the British informed the French that its position “could not but be mainly guided…by the opinion of the Australian colonies.”37 Ultimately, both governments settled on an Anglo-French Joint Naval Commission (16 November 1887), an effort to reduce both security and administrative costs to the extent possible.

The commission’s leadership would alternate monthly between French and British commanders who would coordinate responses to any violent disturbances on the islands and protect and police their own national settlers. Only in cases of imminent danger to the white population from the native population would independent military action be allowed.38 The commission, which was also tasked with diplomatically settling land disputes between the settler factions, seems little more than an attempt by both London and Paris to control their unruly and unpredictable settlers in order to prevent any escalation which could damage Anglo-French cooperation in more important theaters. This commission brought both governments closer together at a time of significant Anglo-French antagonism over Egypt and the Scramble for Africa following the Berlin Conference (1884). The willingness of both parties to ignore the calls for direct annexation by their settlers, and the equality of the military aspect of the commission, speaks to the growing relationship between Britain and France.

While fraught with administrative deficiencies, the commission did lower Anglo-French antagonisms for the better part of two decades. However, a petition of 42 British and 14 French landholders, representing a supposed 1,650,000 acres, sent to the Governor of New Caledonia in August 1899 demonstrates that support for French annexation still existed.39 Settler opinion aside, the commission dashed Higginson’s hopes for direct French annexation and caused the Compagnie Calédonienne efforts at land speculation to spectacularly collapse.40 By 1894 the French government was forced to reorganize the company as the Société Française des Nouvelles-Hébrides, which excluded Higginson from the board of directors.41 With their arch-antagonist dislodged, the Australian colonies were far less agitated. France further thwarted a subversive effort by French settlers to found a new municipality at Francheville on Vila in 1889.42 Paris was serious about upholding its end of the bargain, a bargain substantially in its favor. French officials in Paris believed that the agreement was preferable to direct annexation. With a growing preponderance of French settlers, land ownership and commercial control, France already reaped the majority of the benefits of direct colonial rule while sharing the burden of administration and security with the British.43

|

A French Copra Plantation during the Anglo-French Commission Period (ca. 1890)44 |

Despite a growing French settler population, the commission’s judicial structure was viewed as favoring the settlers from the Australian colonies, particularly regarding disputes over land claims. Vital to the early success of the commission was the de facto governing capacity of the well-established Protestant missions, tied to churches in the Australian colonies, which helped mitigate inter-indigenous and inter-settler rivalries. These missionaries, who were often the only Europeans to speak native languages and gain familiarity with native culture, acted as arbiters and assisted the commission in settling land disputes. However, the primacy of these Australian-based institutions was soon challenged by the arrival of the antagonistic Catholic Marist mission, sponsored by the Vicar Apostolic of New Caledonia in the 1890’s.

The aggressive push by the Marists led to increased land-claim disputes as French settlers now had the powerful political backing of the French Catholic Church. Ultimately, growing land-claim disputes, combined with an increasing French settler population and commercial control, rekindled calls for British annexation by a now united Commonwealth of Australia. The divided state of affairs, increasingly incited by the inter-missionary rivalry, had made the islands ungovernable by 1904 and the ability of the Joint Naval Commission to adequately resolve land-claim disputes collapsed.45

The growing land-claims issue led the Commonwealth government under Deakin to force a final showdown with the French settlers, much to the annoyance of Whitehall. By 1905, and against the larger backdrop of Japan’s new position as the region’s hegemonic power, Deakin officially proclaimed that “the New Hebrides will become part and parcel of the Commonwealth.”46 Deakin informed Governor-General Northcote that, “no settlement will be satisfactory to the Commonwealth which does not decide the possession of the Group, and that the only ownership which can be acceptable…is that of Great Britain.”47 In his conclusion, Deakin brashly derided the Foreign Office for failing to take “even the simplest and most necessary measure to protect British [particularly Australian] settlers” which had resulted in “discouragement throughout the Commonwealth.”48

Deakin’s brazenness earned the ire of the British Foreign Office who had painstakingly crafted a land settlement agreement with the French since June 1905. This sentiment was reflected in Northcote’s terse reply on 03 November 1905. In addition to describing the islands as “quite unimportant”, Northcote stated that “His Majesty’s Government have taken…action in regard to the islands solely at the wishes of Australia and in her non-military interests.”49 Not only would Whitehall not support the Australian position for annexation, it had invited a “French official” to expedite the establishment of a new land claims tribunal.50 Eventually Deakin, who was completely sidelined during the negotiations, was forced to abandon the idea of direct annexation and moved to support joint control by early 1906.51

During consultations with the French, Whitehall realized that a more substantial form of government was needed and, on 27 February 1906, produced a draft envisaging an Anglo-French Condominium – a form of joint rule previously employed in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (from 1899). The draft was forwarded to the governments of Australia and New Zealand, which duly replied with a significant list of amendments. Then the issue sat at the Foreign Office until September, despite repeated enquiries from the Commonwealth as to the status of the agreement and its proposed amendments. According to Le Matin, the delay was due to Australian protests at being excluded from the negotiations.52 However, within weeks, the condominium was hastily finalized and ratified. An Anglo-French Condominium was established on 20 October 1906 without any input from their respective settler representatives.

In contrast to the 1885-87 crisis, the British Foreign Office failed to even tacitly support the wishes of the Australians during the negotiations. A draft of a Whitehall press release dated 03 November 1906 demonstrates the utter lack of consideration for Commonwealth interests on the part of the British during the negotiations. According to Whitehall, the Commonwealth was only informed that the French were seeking a condominium on 09 March 1906, four months after Northcote’s “land claims tribunal” reply and two weeks after the draft condominium was submitted.53 Lord Elgin, Secretary of State for the Colonies (1905-08), was even more disdainful, informing the Australians that the draft must be “confirmed or rejected practically as it stands.”54

The British had had enough of Australian agitation and set about engineering a panic in Australia to achieve the objective of permanently ending this unimportant matter in the New Hebrides. The British falsely hinted that the condominium needed to be approved immediately as a “third party” annexation, possibly by Germany or Japan, was imminent. The Foreign Office correctly surmised that the Australian government would prefer a joint condominium to Japanese annexation. An anxious Commonwealth, left completely in the dark by the Foreign Office, requested on 31 August, 08 and 18 September, that a Joint Protectorate be immediately established “leaving the details…to be settled later.”55 In response to the Australian position, the French government forwarded their request for immediate action on 20 September 1906. The British coyly agreed that haste was needed and failed to support any of the proposed Australasian amendments.56 The British Foreign Office had completely subordinated Australasian interests to that of their new French allies.

When news of Whitehall’s chicanery reached Australasia, the Anglo-French condominium was roundly attacked in the press. The agreement was presented by the Sydney Morning Herald as “new evidence of the [British] to buy foreign friendship at the expense of the colonies” and that it went “against the interests…of the colonies concerned and of the Empire.57 New Zealand Premier J. G. Ward echoed these sentiments by describing the whole affair as a “subordinating of the self-governing colonies to the Imperial requirements with France.”58 The Times correspondent in Sydney reported that public opinion “is one of disgust that British electors can impose upon the Empire a Ministry which within a single year endangers the interests of Australasia.”59

The antipathy was mutual at Whitehall. Lord Loreburn, Lord Chancellor, candidly declared that “the motherland must not make ruinous sacrifices to the colonies and …there ought to be no more annexations” – to Loreburn, the colonies should provide their own defense and not expect assistance from Britain in the future.60 The French did not miss the opportunity to twist the knife with La Patrie congratulating the French diplomats on greatly “irritating” the Australian lobby.61 The Journal des Débats Politiques et Littéraires, hopeful that the future would “open the eyes of Australians”, lectured the Commonwealth on its role as an unconditional supporter of Britannia and her French entente partners.62

Of course, there were other interests in the archipelago than simply French and Australian settlers which found themselves wrapped up in nearly half-century antagonism. The native Melanesian population of the islands, known today as Ni-Vanuatu, had suffered considerable harm over their decades-long contact with French, British and Australian settlers. A system of indentured labour established in the 1860s to support cotton and sugar production in places like Queensland, Fiji, New Caledonia and Samoa – known as “Blackbirding” – enlisted tens of thousands of Melanesian men from New Guinea, the Solomons and the New Hebrides.63 It was a practice that persisted to the establishment of the condominium.

The practice, which often involved coercing illiterate islanders into signing years-long contracts and employing brutal corporal punishment to ensure obedience, tore apart indigenous societies. It is estimated that nearly half of the male population of the New Hebrides were employed in overseas plantations during the height of blackbirding. With many males absent, indigenous birth rates plummeted. Many laborers also died of disease on the plantations, and those that survived often brought back diseases, like syphilis and tuberculosis, which decimated local populations. Returning laborers also introduced Western ideas about social hierarchies and, combined with increased wealth from plantation pay, undermined traditional chiefly power structures. This, in turn, led to inter and intra-tribal conflict, which was exacerbated by the uncontrolled trade in European fire arms, alcohol and opium.64

This societal collapse was further aggravated as British, French and Australians increasingly settled in the archipelago. Various Protestant missions, most of which were based in Australasia, began proselytizing in earnest by the late 1860s. Although the missions assisted in native health care and education during the antagonism, and were leading advocates for the abolition of blackbirding throughout the period, they also undermined native hierarchies based on indigenous religious authority. Furthermore, many young Ni-Vanuatu converts saw Christianity as a way to challenge traditional power brokers – ultimately destabilizing native social cohesion.

The establishment of industrialized plantations by Europeans from the 1870s, with cotton and copra being the chief products, further removed many males from traditional subsistence agriculture and political authority. The European planters, whether Anglo-Saxon or French, also contributed to widespread native land alienation. European land speculation companies like Higginson’s coerced local groups to sell prime cultivated land for European plantation cultivation en masse, removing whole groups to agriculturally poor regions. For a native economy based chiefly on subsistence agriculture and a cultural tradition of shared access to land, land alienation was devastating in both economic and social terms.65 Under this multifaceted pressure during the inter-European antagonism, it was estimated that the native population of the New Hebrides fell from 650,000 in 1870 to only 100,000 in 1900.66

|

Irrigated Native Taro Field on Espiritu Santo (ca. 1913)67 |

But European settlement also led to widespread changes in native society which today form the basis of a Ni-Vanuatan identity. Missionary activity led to a native population which is predominantly Protestant. The training and education of native clergy has likewise developed unique Melanesian forms of Christian practice and worldview. Father Lini’s political rise to power, successful independence movement, and Melanesian nationalism more broadly were rooted in this unique Melanesian Protestant tradition of which he was trained. The establishment of European plantations also altered the character of the islands’ economy. Copra now makes up a third of Vanuatu’s total exports, while cattle, introduced by French settlers, are the nation’s second largest export. Moreover, the widespread introduction of Bislama, a form of Pidgin English which became a lingua franca for various indigenous groups working on the plantations, is today a unifying national language. Although European settlement greatly undermined traditional society, the antagonism also influenced the rise of a particularly Melanesian form of nationalism which has been exported throughout the region.

Conclusion

After thirty years of growing Franco-Australian settler antagonism over the New Hebrides, the Foreign Office had made clear Britain’s reorientation from the Pacific and embrace of France in 1906. The self-denying ordnance of 1878 attempted to maintain the status quo, while the 1887 Joint Naval Commission sought to placate Australian colonial ambitions while incorporating the French in administration. By the time of creation of the Anglo-French Condominium in 1906, colonial demands were completely subordinated to the interests of the Anglo-French Entente (1904). Perhaps most telling was Whitehall’s unapologetic stance on the issue. Despite the outrage of the Australian government, press and people, the Foreign Office refused to apologize for its demeaning actions.

It was now apparent to policy makers in Australia and New Zealand, that they would need to look to their own defense and set their own “sub-imperial” foreign and security policies based on regional threats – specifically that of Japan’s “Yellow Peril”. Within a year of the Condominium’s establishment, Australia appealed directly to America for a visit of the Great White Fleet (1908), the first foreign naval port call in Australian waters and a symbol of a new Anglo-Saxon solidarity.68 Deakin specifically described the new relationship as an alliance of Anglo-Saxon Pacific powers, tied together by a common fear of the “Yellow Peril”. Over the next decade, Australia greatly expanded its own military, coastal defense and naval forces with an eye toward Japan, despite the good standing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

At the outbreak of World War One, Australia and New Zealand moved quickly to ensure that Japan did not breach the “island wall” by occupying Germany’s colonies south of the equator. The capture of New Guinea, Samoa, and Nauru effectively sealed the Japanese out of the Southwest Pacific. But despite the final achievement of the “island wall”, and the fact that the Imperial Japanese Navy escorted Australian ships from Suez to Sydney throughout World War One, the Australian government continued to view the “Yellow Peril” as its main strategic threat. It was the Australasian government which, during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, insisted that a Japanese-sponsored racial equality clause be excluded in the final Versailles Treaty. Such a clause would undermine the “White Australia” policy, which now extended to all Australasian occupied territories south of the equator. By the Imperial Conference of 1921, Australia and New Zealand vehemently argued for the termination of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in favor of a stronger relationship with the United States. Unlike during the debate over the New Hebrides, Australian posturing, combined with a desire to maintain its relationship with the Japanophobic United States, led Britain to terminate the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1923.

Ultimately, the “quite unimportant” issue of the New Hebrides exacerbated the shifting dynamics of British prewar imperial policy. The animosity between the Australian colonies (and later Commonwealth) and Britain, generated by Franco-Australian settler antagonisms over the New Hebrides and a fear of strategic abandonment in the face of the Japanese “Yellow Peril”, altered the perception of imperial responsibilities in the Pacific by both parties.

Notes

Governor General Henry Northcote to Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, 03 November 1905, Prime Minister Papers, No. 05/4706, para 4, National Archives of Australia, Canberra [hereafter NAA].

Mark Kurt Tabani, “Walter Lini, la coutume de Vanuatu et le socialisme mélanésien”, Journal de la Société des océanistes, Vol. 111 (2002). pp. 173-194.

Stephen Henningham, The Pacific Island States: Security and Sovereignty in the Post-Cold War World (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995), p. 38-40.

PMC Editor, “Solomon Islands, Vanuatu promote MSG support for West Papua“, 13 May 2016, accessed 30 March 2017.

This composite map was created from two separate maps. “Southwest Pacific” and “Vanuatu Base”, CartoGIS, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, accessed 07 April 2017. See here.

Neville Meaney, The Search for Security in the Pacific, 1901-14 (Sydney, 1976), p. 16-21 and 117-119.

For a substantive view of the New Hebrides in a French Regional Context, see: Robert Aldrich, The French Presence in the South Pacific, 1842-1940 (London, 1990).

“Das schließt natürlich … überraschend einsetzen müßte.” Friedrich v Bernhardi, Deustchland und die nächste Krieg (Berlin, 1912), p. 176.

Henry P. Frei, “Japan in World Politics and Pacific Expansion, 1870s-1919”, The German Empire and Britain’s Pacific Dominions 1871-1919, (ed.) John Moses, and Christopher Pugsley (California, 1999), p. 182.

Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 12 September 1901, Vol. 4. p. 4805-7, 4817, in F. K. Crowley, Modern Australia in Documents, Vol. I (Melbourne, 1973), p. 17.

By 1905, the Imperial Japanese Navy consisted of six first-rate battleships, eight heavy cruisers and seventeen light cruisers. The Royal Navy’s Australia Station maintained only ten 2nd and 3rd rate cruisers. Masayoshi Matsumura, Baron Suematsu in Europe during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5); His Battle with Yellow Peril, Ian Ruxton (trans.) (Morrisville, 2011), p. 72.

In 1905, the Japanese population was 46.8 million and her annual GDP was 54 billion (in 1990 US dollars). Australia, by comparison, had a population of four million and an annual GDP of 17.1 billion. Angus Madison, Historical Statistics for the World Economy, 1-2003 A.D., accessed 12 February 2017.

Historical Section of the British Foreign Office, Peace Handbooks (1920), Vol. XXII, No. 147, p. 10.

Le Marquis d’Harcourt to Lord Derby, 15 January 1878, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères Paris, Affaires Des Nouvelles-Hébrides et des Îles-sous-le-vent de Tahiti, Documents Diplomatiques, (Paris, 1887), No. 2.

La Dépêche coloniale illustrée (Paris), 31 Julliet 1902, Cover Page, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, accessed on 20 April 2017, James Service, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, H93.359/5, accessed on 20 April 2017.

Conversion rate of 25.42 Francs to Pounds Sterling based on adjusted conversion rates of the British Foreign Office in 1920. Peace Handbooks, Vol. XXII, No. 146, p. 29.

Jean-Philippe Dumas, “La Marine et les intéréts française aux Nouvelles-Hébrides (1860-1907)”, La Revue administrative, 57e Année, No. 337 (Janvier 2004), p. 75-84.

Lord Rosebery to Mons. Waddinton, 07 July 1886, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, Affaires Des Nouvelles-Hébrides et des Îles-sous-le-vent de Tahiti, Documents Diplomatiques (Paris, 1887), No. 24.

Declaration between Great Britain and France, for the constitution of a Joint Naval Commission for the protection of Life and Property in the New Hebrides (Paris, 26 January 1888).

“16. Que les pétitionnaires … pour la condition des colons”. E. N. Imhaus, Les Nouvelles-Hébrides (Paris, 1890), p. 153.

By 1888, only 250 out of 100,000 hectares were under active cultivation by the Compagnie Calédonienne. Aldrich, p. 132.

Draft notes from Whitehall Press Statement, London, 03 November 1906, Department of External Affairs, No. 06/8527, fo. 2, NAA.

“The British colonies are irritated at seeing their representations have not been taken into consideration and they hold that the clauses of the agreement are too favorable to France….that once again is to the honour of M. Marcel Saint-Germain…it would be impossible to congratulate them too warmly on their achievement”. Argus, 06 December 1906.

“Peut-être un avenir … européens de ce dernier”. Journal des Débats Politiques et Littéraires, 10 November 1906.

Gerald Horne, The White Pacific: U. S. Imperialism and Black Slavery in the South Seas after the Civil War (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007), Chap. 2.

Felix Speiser, “Decadence and Preservation in the New Hebrides”, Essays on the Depopulation of Melanesia, W. H. R. Rivers (ed.) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922), p. 25-61; John R. Baker, “Depopulation in Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 58 (January – June 1928), p. 279-303.

Palauni M. Tuiasosopo, “Land Alienation in the New Hebrides: Colonial Policies of France and Great Britain”, Unpublished MA Thesis (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 1994).

Felix Speiser, Two Years with the Natives in the Western Pacific (London: Mills & Boon, 1913), p. 180.