Abstract

The Japanese manga and animation industry was established under special conditions in the high growth period of the 1960’s. At that time the domestic market of the publishing industry and the film industry was large, the literacy rate was high, other entertainment was little developed, and the industry did not yet confront the challenges of globalization. However, the industrial structure established during this period has deteriorated to one that exploits creators who have weak bargaining power. This reflects the situation throughout Japanese society in the sense that the social structure originating in the 1960s has lost flexibility, creating dysfunction and growing disparities.

Keywords: Socio-Cultural Structure, Constructed Specificity, Cognitive Precariat, manga, anime

Postwar Japan was a fertile ground of creativity that produced numerous high-caliber manga and animation works. I will investigate the background to this phenomenon, and the factors that fostered these industries to the point that they were able to find success in foreign markets. Postwar Japan was a highly literate society with a strong intellectual bent and a vibrant publishing industry. Japan at that time was still a developing nation with few other forms of entertainment. I contrast that epoch with the situation of creators of manga and animation in recent years when conditions have changed profoundly.

There has been little research on the economic and social background of manga and animation in Japan because information on these industries is rarely disclosed. This paper is also subject to that limitation. However, in 2015, the economic situation survey of animation creators was published and the nature of the animation and manga industry began to gain attention. I show that the industrial structure developed under the special social circumstances in the 1960s gave rise to many problems that have recently become clear. The path dependence and maladaptation to the change in the industry is just one example of wider problems confronting Japanese society. This paper offers an overview of the problem.

Japan in the Economic Boom Years

Japanese manga and animation established their status in society during the so-called economic boom years, the period of extraordinarily high growth that lasted from the mid-1950s to the beginning of the 1970s.

Before its transformation into an economic powerhouse, Japan was one of many developing nations in Asia. In 1948, per capita income was less than $100 in Japan compared with $91 in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and $88 in the Philippines.1

In around 1960, the number of movie productions in Japan was much higher than in the United States. This pre-dated the current competition with film for consumers’ attention and pockets, such as the Internet, computer games, mobile phones, or convenience stores. India is the most prolific producer of films in the world today, which is natural for a developing nation with limited entertainment alternatives and a gigantic domestic market—factors conducive to sustaining a flourishing cinema industry. 547 Japanese made films were released in 1960. By contrast there were 121 American films made and released in the United States in 1963. Japanese audience figures in cinema theaters peaked at 1.13 billion in 1958, and declined steadily thereafter to 126 million in 1992 as television ownership increased. (The film audience recovered to 180 million in 2016 with the spread of cinema-complexes.).2 The size and strength of film companies in the 1950s was an important factor in the development of Japanese animation, as they functioned as incubators.

Compared with today’s developing nations, Japan at that time was noteworthy for the strength of its publishing industry’s popular base. A 1968 survey of “recreational and leisure activities” listed the following results: 1) Reading, 2) Travel involving at least one night’s stay (mostly domestic trips), 3) Handicrafts and sewing (high ranking among female respondents), 4) Drinking at home, and 5) Cinema and theatre-going (mainly popular entertainment for both categories, traditional Kabuki and vaudeville theaters)3. Reading was the number one recreation in Japan in 1960s. These results were the product of a number of factors—although Japan’s economic indices were still modest, the population had a remarkably high literacy rate, and the options for entertainment were limited.

One factor supporting the flourishing cinema and publishing industries was the size of Japan’s population, which reached 100 million in 1966 and provided a massive domestic market. In many of today’s small developing nations, globalization has led to popular entertainment being dominated by American (or a regional power) in the form of films and television series. In the case of Japan, the sheer size of the population sustained domestic publishing and cinema. Japan is an island nation, but more important than geography was the fact that the country was never colonized, and universal education produced high literacy and united the populace under a common language.

The advent of Japan’s high economic growth coincided with the period when television began to gain popularity in the U.S. and Europe, so there was a smaller gap between the regions, compared with the marked contrast between developing nations and the advanced industrialized world today. Importing American and European television series was less costly than producing in Japan, but the quantity available was simply insufficient to respond to burgeoning demand. Many programs were produced by Japanese creators, including children’s series such as Gekkō Kamen (1958), and led to the establishment of Tsuburaya Productions, famous for Ultra Man, and other companies that specialized in this medium. Production of made-for-television animation began under these market circumstances.

The size and the strength of the publishing market, Japan’s high literacy rate, and the fact that the nation had yet to attain affluence were all factors that spurred youthful talent to become writers, filmmakers and manga artists. Matsumoto Reiji mentions in a 1997 interview that Disney films had originally inspired him to dream of creating animation, and that he turned to manga because of the affordability of paper and pens in 1950s Japan. Matsumoto said: “Cheap prices of stationary goods was critical as the reason I could become a manga writer despite my difficult economic situation. In Japan, paper, pencils and ink were very cheap compared with other developing countries”.4 The situation came from huge domestic stationary market and industry. Nowadays, a counterpart in a developing nation might choose to realize his or her dream by emigrating to the U.S. and finding work at Walt Disney Studios, but foreign travel was heavily restricted for Japanese until 1964, except for those who had official approval for study abroad or for business requirements.

Manga and the Economics of Publishing

It should be noted that publishing was regarded as a high earning, high status occupation in early and mid-20th century in Japan. The money paid to authors was impressive.

According a memoir of Shimizu Ikutarō, a prominent sociologist and critic from the 1930s to the 1980s, his payment from publishers was 5 yen for a standard manuscript page of 400 characters in the 1930s.5 A university graduate’s starting monthly salary in big companies in 1933 was 50 yen. It was said that publishing a single volume in the Iwanami publisher Shinsho (general information) series was worth enough to build a house.

This was because of the high prices that publishers charged. In 1926, Kaizōsha publisher in Tokyo launched a series dubbed yen hon (one-yen books) after the cover price, which was considered to be a tremendous bargain, and the focus of a great deal of excitement. One yen was 2-3% of the average university graduate’s starting salary. The descendants of yen hon, today’s paperbacks, are priced in hundreds yen (a few US dollars), not thousands of yen. It was only natural that owners were persons of privilege, and that books were regarded as status symbols. In many developing countries, books and newspapers were extremely expensive, and usually could only be afforded by the affluent, and were often shared and borrowed, rather than purchased.

After World War II, while the rate of payment declined in relative terms, high economic growth led to an expansion of the readership base. Around 1970, monthly magazines that catered to the popular market had circulation figures in the hundreds of thousands. Shosetsu Gendai (Modern Novels Magazine) from Kōdansha publisher reached 435,000 thousand in 1968. (In 2011 sales were just 24,000.) In Japan in 1968, as I already mentioned, the top in “recreational and leisure activities” was reading. Many popular novels that became best sellers performed similarly well.

Celebrated authors built showpiece houses, and their luxurious lifestyles were an aspirational for many young people. Until the 1970s, a young corporate employee would take out a mortgage to buy a house in the suburbs, furnish the sitting room with a piano, a sofa, and a chandelier, and after carefully choosing bookcases, would then purchase a set of encyclopedia and the Collected Great Works of World Literature to fill the shelves. Intellectualism was a status symbol, and provided the background for the creation of manga with a highly literary bent.

Another background of Japanese manga and animation was that the gap between mass culture and the educated classes was relatively small. This does not necessarily mean that income gaps were small. The narrow gap noted here is that there was no language division. Since Japan was not colonized, higher education was rarely conducted in European languages, and language division did not occur in society. In many colonized countries, publications aimed at intellectuals and the middle class are frequently in English or other European languages, while the mass market uses local languages, leading to a clear demarcation between the culture of the educated, and the public at large. This limits the size of the domestic publishing market, and as books of literary merit are expensive, only the upper and middle classes can afford them. This made it impossible for most full-time authors to live off their writing. They would either seek employment or seek acclaim in the English-speaking world and its international markets.

In the case of modern Japan, the high literacy rate and the single language made an entire sector of publishing that catered to the information and enlightenment of children viable, even before World War II. Famous examples include magazines such as Kōdansha’s Shōnen Club (Boys Club, f.1914), Shōgakukan’s Shōgaku-Rokunensei (6th Grade, f.1922), Kōbunsha’s Shōnen (Boys, f.1946), and the Iwanami Shōnen Bunko children’s books series, which began publication in 1950. These were primarily for middle-class children, and Shōnen-Club and Shōgaku Rokunensei were mainly available to subscribers, who received issues directly from the publishers. The common practice of sharing and borrowing reading material meant that children from lower income families could also enjoy them.

These publications that set out to inform and enlighten middle class children became the industrial and cultural nurturing ground for manga and animation. Shōnen-Club serialized Nora-kuro (Black Dog Soldier) and Bōken Dankichi (Adventure of Dan) from the 1930s, and Shōnen began to serialize Tetsuwan-Atom (Astro Boy) from 1952. Many of the titles that inspired the animation films of Miyazaki Hayao and Takahata Isao were included in the Iwanami Shōnen Bunko.

Japan’s baby boomers, born after World War II, proved to be a receptive market for these publications. By the time they were in the higher grades at elementary school, and had increased their ability to absorb information, their parents were reaping the benefits of Japan’s economic boom, and had more disposable income. This was all taking place in a world without mobile phones and computer games. Magazines published by Shōgakukan and Gakken for elementary school pupils increased their circulation, and in 1959, Weekly Shōnen Magazine from Kōdansha and Weekly Shōnen Sunday from Shōgakukan were founded.

Another incubator of the manga industry was the Kashi honya (book lenders). An investigation by the Metropolitan Police Department in 1954 found that there were about 3000 book lenders in Tokyo. There is no nationwide survey, but it is estimated that there were about 30,000 in the mid 1950s.6 Book lenders were already a feature of life in the Edo period (1600-1868).

Book lenders rented books purchased in new or second-hand at one-twentieth of the cover price. Although pre-war rental books were mostly for adults, after the war, lending books for children including manga became more frequent. Around 1950, manga books with low print quality of 16 pages to 64 pages called “Red Books” were published from small publishers and distributed through book lenders. These “Red Books” were published by a number of small publishers established after 1945, with best sellers reaching 800,000 copies.7

|

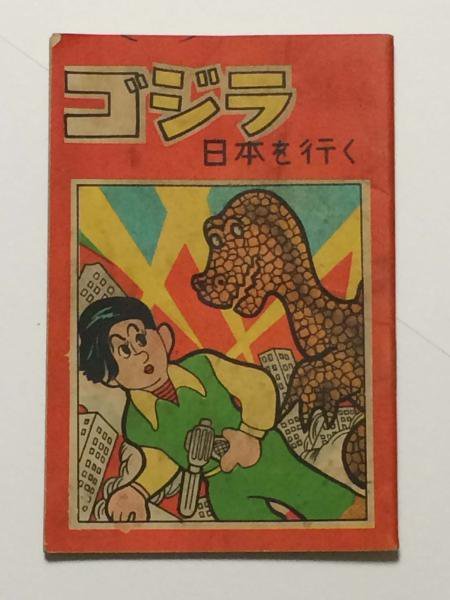

Godzilla Goes to Japan |

Takekuma Kentarō |

The boom of “Red Books” was short, and eventually the major publishers dominated manga publishing. However, in the transition period when the price of manga was still relatively high, there was still a place for book lenders. According to an interview, in the 1960s when comic books were between 220 and 240 yen, many dealers bought dead stock manga books that could not be sold at bookstores by weight. They then sold manga books to book lenders at 30 yen each, and book lenders lent these to children for 10 yen.8

As Japan’s economy continued its surge, readers began to switch from borrowing from book lenders to buying their own copies of magazines and manga books, the latter collecting manga in more durable format. Weekly Shōnen Magazine, which was launched in 1959, had an initial cover price of 40 yen, which was immediately revised down to 30 yen. At its founding, circulation was 205,000, which increased to more than 1.5 million in 1970. Manga books were still expensive compared to manga magazines, but as more and more children bought, rather than borrowed, book lenders saw their business decline.

As the economy expanded, the number of bookshops increased. Although the number has declined since the mid-90s, Japan had a large number of bookshops compared with its population, with 1 for every 7,710 persons in 2006, compared to 1 for every 13,318 in South Korea in 2006, 27,363 in the U.S. and 14,925 in the U.K.in 2002.9

The launch of weekly magazines, and their business model based on large circulation, made manga a profitable proposition for their creators. The actual rates that were paid to the artists are regarded as classified information in the industry, and no official statistics exist. According to manga artist Takekuma Kentarō, the current rate for manga is 20,000 to 50,000 yen per page, while an artist who has just debuted would receive about 5000 yen per page, which is the same fee that Takekuma received as a newcomer in the early 1980s. He believes that the payment scale has probably remained unchanged since around 1970, despite the fact that a university graduate’s starting salary has increased fivefold in the same period. According to Takekuma, until the early 1970s, “it was possible for a manga artist to buy a house or a car just from magazine earnings, something that has become unimaginable.”10

In the 1960s, young artists were attracted to manga for two reasons. One, of course, was the high earning potential. Manga was an attractive profession for individuals such as Akatsuka Fujio, a young man from Niigata, who left school after completing compulsory education, and therefore had limited options for raising his status in Japanese society. This also applied to young, talented, university students who faced similar difficulties because they happened to be women such as Takemiya Keiko. The second factor was the assistant system, which supported the high volume of production that made weekly serialization possible. This was another product of the 1960s, and often allowed young artists to hone their skills. The assistant system only applied when the featured manga artist could afford to hire help.

|

Akatsuka Fujio |

Manga is extremely labor-intensive, and it is difficult for a single person working alone to produce more than two pages a day. One installment requires 16 pages of grueling hard work, which in the case of some artists only nets 30,000 yen total in nowadays – proof of how manga earning power has declined.11

Takekuma summarizes the transition of the manga industry since the 1960s as follows. During Japan’s economic boom years, publishers were able to profit from magazine sales, and could afford to pay artists well. Book collections of manga were expensive, and had limited circulation. At that time, many comics were only published in magazines, and there were not many manga published in book form. The 1973 Oil Crisis brought an end to the period of double-digit growth, and while sales of magazines stagnated, the number of manga becoming books increased. The industry shifted its business model—magazines were kept afloat by restricting artists’ fees, and books became their new source of profit. This was still acceptable to the artists, for even though their initial fees may have been kept low, their collected work guaranteed a steady income stream. After the 1990s, sales of magazines and books both began to languish, except for a handful of titles that became monster hits. This appears to be the cause of the widening gap between successful and unsuccessful artists, and the relative decline of artists’ income.12

There are hardly any countries apart from Japan with large numbers of professional creators of narrative-based comics, rather than single-panel cartoons. This is because full-time commitment as a professional is only possible when either the artists are very well paid, or can achieve high sales in their collected work as books. The formerly gigantic U.S. comics industry fell into decline after the 1960s.13 Not only did Japanese manga gain an international audience, but it makes economic sense to import and translate manga from Japan than pay native artists high fees in many countries. What sustained the growth and development of Japanese manga in the years of high economic growth was the gigantic domestic market, which emerged as the result of a number of factors.

Kyōyō-shugi (kyōyō-ism), the belief that a thorough grounding in the liberal arts was a crucial element in self-improvement and character-building, also influenced Japanese manga. Kyōyō-shugi originated among educated elites in the Taisho Era (1911-1925), influenced by 19th century German liberal education. It regarded western literature as the pinnacle of human cultural achievement. The belief was a cornerstone of the Japanese new middle-class through the end of the economic boom years, together with other indispensible accoutrements such the piano, the chandelier, golf, the sofa, the encyclopedia, and the Collected Works of World Literature mentioned above.

Outstanding manga artists also referenced kyōyō-shugi in their work. While living at the Tokiwa-Sō apartment house—famous for the number of young manga artists who lived there in the 1950s – individuals such as Akatsuka Fujio, Ishinomori Shōtaro and Fujio Fujiko recounted in their memoirs their heavy exposure to European and American films and literature. According to an interview with Akatsuka, when they visited a famous manga artist Tezuka Osamu, Tezuka told them “If you wish to become manga artists, don’t read manga. It’s more important that you watch first-rate films, listen to first-rate music, read first-rate books, and see first-rate theatre performances.”14

Akatsuka often adapted short stories by authors such as Charles Dickens, while Ishinomori created stories inspired by European and American science fiction, and composed panels that adapted scenes from European films. Science fiction and avant-garde European films were also important for the women who created manga for girls in the 1970s. This resulted in the creation of many works that were meant for children, but had strong overtones of mature tastes that referenced literature and foreign films, a phenomenon rarely seen in other countries at that time.

As the manga sector had its roots in enlightened children’s publishing, manga with kyōyō-shugi tendencies was a natural fit. Looking at the early years of the Weekly Shōnen Magazine, each issue included numerous articles on science, literature, or foreign affairs in addition to manga. Although such content had faded away by 1970s, the economic robustness of the industry helped to support opportunities to launch experimental work. The experimental magazine COM was a special case—founded by Tezuka Osamu, and sustained by the money that he made through his manga. But even commercially published magazines such as Shōnen Magazine and Shōnen Jump carried experimental work by new artists in their back pages.

Social Background of Japanese Animation

Many of the factors that were instrumental in the emergence of manga also hold true for animation.

The defining characteristic of Japanese animation is the format that Tezuka devised—volume production for television, broadcast in weekly 30-minute episodes (23-minutes in actual except for advertisement). Animation, like manga, is extremely labor intensive. Walt Disney Studios, for example, released feature films at intervals of a number of years, and weekly programs never entered into their considerations.

Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy) began airing in 1963, and the made-for-TV format of 30-minute episodes was born. This was possible through extensive use of techniques such as limited animation, and mobilizing large numbers of low-cost animators. Japanese television broadcasting was in its infancy, there was a need of content to fill the schedules, and imported programs were not utilized to the extent that they are today, so despite the drastically simplified animation and low-grade production values, the series was highly acclaimed. The production was possible due to the country’s plentiful supply of low-cost young artists. Over the following decade, Japanese animation enhanced its production values to a level at which it could be exported around the world, until circumstances changed dramatically with the end of the 360-yen dollar in 1971, and the 1973 Oil Crisis, which cut short Japan’s era of dramatic high growth.

The cinema industry was still strong and attracted young talent to work on animated feature films. Takahata Isao was the son of the Superintendent of Education for Okayama Prefecture, and having studied French Literature at the University of Tokyo, was one of the elite who could have had his pick of good jobs. But as a film aficionado, he joined the rising young animation production company Toei Animation in 1958. This subsidiary of Toei (Tokyo Cinema) was a small enterprise, but with the Japanese film industry at its peak, the pay was in line with the usual starting salaries for university graduates.

A few years later, Miyazaki Hayao, who had been a member of the Children’s Literature Study Club at Gakushūin University, joined the company. In 1968, Takahata and Miyazaki worked together on Taiyou no ouji Horusu no daibouken (Hols: Prince of the Sun). The film drew on the experiences of the labour movement at Toei Animation in depicting a battle to save a community. Although an artistic success, it was a box office failure.15 Production was still possible, as there was a secure distribution channel as part of the packaged program for the Toei Manga Parade (Toei Animation Film Festival) screening format of family-oriented films, which was regularly featured during school holidays.

With the decline of cinema, Takahata and Miyazaki, like many others, transferred to television. Their oeuvre includes strands that originate from the Iwanami Shōnen Bunko books that they read avidly as boys, western literature and films, science fiction, and academic studies of history.

Much of their work such as Hols, Lupin Sansei (Lupin III), and Mirai Shōnen Conan (Conan, the Boy in Future) were initially weak performers at the box office and in television ratings, but later won acclaim. Together with Otsuka Yasuo, who collaborated on Lupin Sansei, Takahata and Miyazaki had an established reputation for creating expensive flops. But the overall strength of the industry, and the length of television seasons (frequently 3~4 times as many episodes as today) combined with the rarity of mid-season cancellations, the high mobility of the creators and their ability to set up their own successful companies, and the patronage of their patron, the owner of Tokuma Shoten Publishing who was a proponent of kyōyō-shugi, combined to work in their favor. This allowed them to continue to produce films until they won both acclaim and steady audiences.

There are many other examples similar to Takahata and Miyazaki, such as Kidō Senshi Gundam (Mobile Suit Gundam) and Uchū Senkan Yamato (Space BattleshipYamato) which initially had lackluster ratings but won acclaim through reruns. The situation is different today, for work that does not have mass appeal is broadcast just once on cable TV, and immediately put to video, meaning that awareness does not spread beyond a small number of fans. The pattern that existed through the 1980s is probably the result of the limited number of channels, and the then common practice of repeated showings.

Despite growing popularity throughout the world, wages in the Japanese animation industry are declining. According research by JANICA (Japanese Animation Creator Association) in 2015, the average annual income of fresh animators is only 1.1 million yen (approximately 10,000 US$), while the average annual salary of private companies is 4.20 million yen in 2015. The average for all occupations in the industry including directors and producers is 3.22 million yen (29,200 US$). The average working hours per day is 11.0 hours, the average holiday in a month is 4.6 days. Regular employees are only one in six, and those with an annual contract only one in three among contract workers.16 Payment for one painting is said to be around 200-300 yen (1.8-2.7 US$), and even an experienced animator is said to be limited to 500 sheets per month. If you draw 500 pictures per month with 200 yen per price, 6000 per year, annual income will be a modest 1.2 million yen (10,900US$).17

The wages of voice actors are also low. The performance fee for a 30 minute animation for a rookie voice actor is 15,000 yen (136 US$), even the highest rank is 45,000 yen (409 US$). If an average voice actor appeared in a 90 minute nationwide screen animation, payment would be 95,000 yen (863 US$) including special allowances.18

This situation is caused by the fact that about 80% of Japanese animation production companies are small companies, making works to be delivered to TV companies and investors at low price. Production fees paid by television stations or investors for a 30 minute animation to production companies are 15 million yen to 20 million yen (13,600-18,200 US$) , and this amount has not changed much over more than 20 years.19 With this budget, the production company has to make an animation using 3000-5000 pictures, a scenario, music, voices, and sound effects. Meanwhile, smoother movement than before was required, and the necessary time and labor are increasing. Introduction of CG and digital technology has raised production costs. Although wages are low, a quarter of animation production companies are in the red.20

This situation is shared with manga artists, and with the growing income disparity in Japanese society as a whole. In the 1960s, hourly wages in Japanese industry were high, sometimes more than those for regular employees. When the Japanese economy stagnated from the 1990s, wages of hourly workers and contract workers declined compared to the wages of large corporate regular employees. The fees paid to animation production companies and the manga artists’ drawing fees have not been raised for 20 to 30 years, evidence that their bargaining power is inferior to that of publishers and broadcasting companies.

Kamiyama Kenji, the famous animation director said in 2017, “If an animator draws such a complicated picture with 250 or 300 yen as a production fee that remains unchanged, their wages will not rise. Recently DVDs have not been sold and production costs are decreasing.” “Demand has increased over the last few years, but earnings are not easily returned to the production side because money is returned to investors.” “I intend to gradually change, but nothing has changed since 20 years ago.”21

|

Kamiyama Kenji |

A Japanese economic magazine summarized the situation in 2017. “Eighty percent of newcomers are exhausted, leaving the industry in a few years.” ”Although the animation market has expanded to 2 trillion yen and overseas demand has increased, the situation of creators has not improved.” Kawaguchi Takanori, the representative of the production company “Comics Wave Films” that produced the mega hit animation film “Kimi no Na ha (Your Name)” in 2016, says, “if the industry does not begin to hire and develop people at fair pay, no matter how much the market swells, Japanese animation production will be lost.”22

Manga and Animation as a Reflection of Postwar Japan

This was how manga and animation were established in Japan during the period of high economic growth. Various factors such as talented creators, kyōyō-shugi, the fact that the market could afford to accommodate experimentation, and the system enabling volume production combined to create formats that generated manga and animation of high cultural merit, even as they were popular art forms aimed at youth and children. Their market continued to be provided by the generations starting with the postwar baby boomers.

In the Western world, and in the markets of the developing world, there was a clear separation between cultural output intended for adults, and for children, and between high and low culture. There was not much in the way of classless youth culture that emerged with the development of industrialized societies and the rise of the middle classes, which was where Japanese manga and animation discovered its international market. The volume production system that was born from Japanese television broadcasting was another factor that aided their acceptance in Western and Asian markets from the 1970s onwards, as animation series that were based on 30-minute weekly episodes were rarities in the world at that time. Produced in massive quantities, inexpensive, but with high-grade production values and able to find acceptance amongst audiences that cut across class and generational boundaries—these characteristics were instrumental in sustaining an export industry.

The birth of the manga and animation industries was also aided by the purchasing power of Japan’s vast domestic market, and the fact that in its infancy, it was relatively insulated from foreign competition. A similar situation surrounded what became the economic and cultural symbols of postwar Japan, the automotive and electronics industries. Until the early 1960s, Japanese cars and electrical goods were inferior to those of their western counterparts both in price and performance, but subsequent mass production to fulfill domestic demand enabled manufacturers to improve their quality and prices, and then from the 1970s to expand into global markets. Japan’s manga and animation followed suit. These emblems of postwar Japanese culture emerged out of economic growth during the period of so-called “Japan as a middle class society.”

In recent decades, the decline in the Japanese economy, and the publishing market, combined with the waning influence of kyōyō-shugi, have led to difficulties for the manga industry. Weekly Shōnen Jump has the largest circulation of all Japanese manga magazines, recording 6.53 million copies in 1995 but falling to 2 million in 2016.23 Publishing has been in general decline since sales peaked in 1996, and the number of bookshops has fallen too – 22, 296 in 1999 shrank to 13,488 in 2015.24

Today’s manga magazines are highly segmented by age and taste (and probably class), and apart from a handful of exceptions, it has become rare for manga to become part of the shared awareness of the people of Japan. This reflects the changing face of Japanese society, the collapse of Japan’s mass identification with the “middle-class society” and widening inequality, combined with the shrinkage of the overall publishing market leading to higher segmentation and highly focused mining of specific niches.

Actually Japanese manga and animation are not a large presence in the world content industry. Sales of Japanese origin content was 2.5% of the world content market excluding Japan in 2015. Japanese animation sales account for 4.1% of the world’s animation market excluding Japan. This is more than 0.4% of the broadcast, 0.2% of the music, and 1.1% of the film, but it is not a large number. Manga account for 26.9%, but this is because the genre itself is special. Certainly, overseas demand for Japanese animation is expected to increase, but in the background there is a forecast that content demand in the world except Japan will increase by 3.9% per year by 2020 (7.5% in Asia and the Pacific).25 In other words, not only demand increasing for Japanese animation and manga but overall demand for content is growing.

The export of manga for North America peaked in 2005, when there was intensive translation and publication of outstanding work from Japan. It should also be noted that while manga exports attracted a great deal of attention, overseas markets did not expand far beyond a limited segment of younger readers and enthusiastic fans.26 As conditions surrounding publishers worsened, and fees declined in relative terms, making it difficult for manga to attract talent, the industry became less able to support experimental commercial work.

Technological developments have made self-publishing and self-production easier, which combined with the greater diversity due to higher segmentation of publications, and the advent of newer media such as the Internet and cable TV, have in fact increased opportunities for launching experimental work. These avenues, however, only provide access to a limited number of hardcore enthusiasts. So, with a few exceptions that manage to generate profit, it is not easy for creators to make a living.

South Korea has a smaller domestic market than Japan, and is more exposed to the impact of global market shifts. Its comic magazines flourished later than their Japanese counterparts, but experienced societal and technological transformations after financial crisis in 1997. Due to these changes, the Internet is now the usual platform for comics, but the situation surrounding creators is said to be extremely bleak.

If Internet downloads become the norm, perhaps the manga format itself will change. The small screens in mobile phones and the iPad render the technique of drawing in the details of backgrounds meaningless, so simplified drawing in thick strokes will probably become the norm. If paper and pen fall out of fashion, and direct inputs onto the computer screen become general practice, simplification will likely accelerate. It is even possible that in the manner of Vocaloid music, computers will begin to auto-correct drawings. Perhaps there will be software that can generate manga automatically, only requiring instructions concerning dialogue and the position of figures, to create archetypical characters in the manner of Japanese manga, or the Tezuka style – making it possible for those who cannot draw to become “manga artists”. These changes would also be in the interest of artists and publishers who need to resolve issues such as low fees and are interested in labor-saving techniques. Manga input operations may become viable businesses, by using software to convert publishers’ storylines into manga format, and the actual work may ultimately be contracted abroad to developing nations.

An increasing number of manga artists will continue to release highly artistic work via the Internet or self-publishing / self-production channels, while securing their livelihood through other means. It is also likely that we will see the co-existence of a handful of full-time professionals who are able to become high-earners, and manga production teams, whose output consists of new installments of long-running titles (such as Golgo 13), even in the absence of the original creator (such as Dorae-mon). Manga software may be used by “legendary artists” in order to create new work in the style of their prime, allowing them to continue to be active well into their old age. Ultimately, it is possible that hand-drawn manga will become like contemporary calligraphy, a field in which only a handful of professionals can actually make a living—an artistic accomplishment that has faded away.

With this greater “diversity” among artists, the cultural format of manga will be forced to change. But manga is not alone, for these trends can be seen in other fields such as literature, and reflect the transformations that are occurring across Japanese society.

This situation reflects the overall situation of Japanese society in two respects. Firstly, the system which once produced vitality and a decent livelihood for writers and artists is now transforming into one of disparity and exploitation. The creator, who is inferior in bargaining power, unity, and information, is being exploited with payments fixed for 20 to more than 30 years. Unless this situation is reformed, the sustainability of the system can not be guaranteed.

Secondly, this situation is shared with cognitive workers in post industrial society. If advanced information technology is introduced without asymmetric power balance being reformed, their position will become increasingly unstable. This is not limited to Japan’s manga and animation industry.

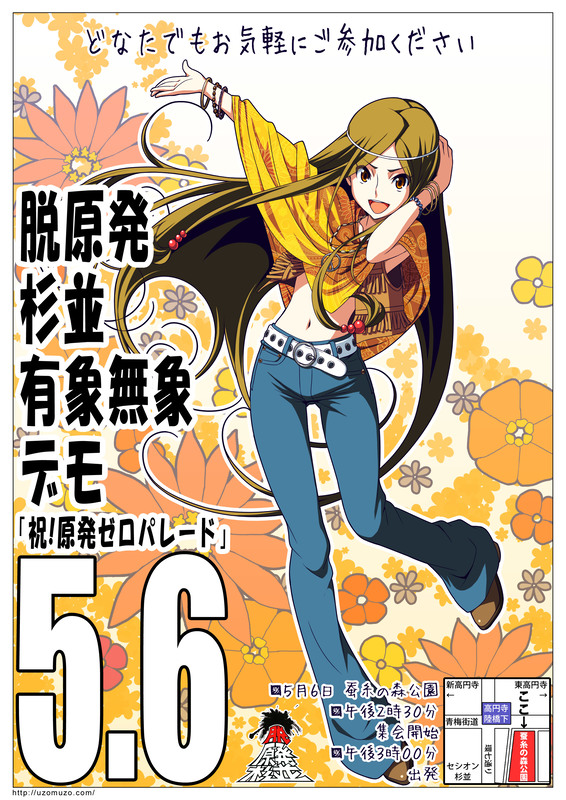

Surveying the anti-nuclear movement after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, I found the extensive involvement of the cognitive precariat.27 This movement was based on skills that they professionally acquired, such as IT and design. Some anti-nuclear flyers that can be downloaded from the organizer ‘s website include those drawn by manga artists.28 Given that manga writers and animators are also among the Japanese cognitive precariat, this is a natural phenomenon.

|

|

As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, reliable information on the manga and animation industry is limited. In particular, the situation before the 1990s can only be deduced from relevant historical information and fragmentary memoirs as in this paper. This paper provides only an overview, providing a baseline for investigations by future researchers.

Contemporary manga and animation formats are the result of the particular circumstances—economic, technical, and media-related—that existed during a specific period. This is to be expected, for culture, after all, is the product of the overall structure of society. The sustainability of this industry cannot be guaranteed without improving the situation of creators by reforming the industrial structure. If a cultural form that was born during a specific epoch in Japanese society is to be fostered, or retained, we should first understand its evolution, and then consider which aspects to develop further, and what to protect. In effect, this is a process which requires that we confront the question “what was postwar Japan?”

This paper is revised from Eiji Oguma “Generating of a Japanese Popular Culture: Manga and Anime in Postwar Japan”, keynote speech in the Second International Convention on Manga, Animation, Game and Media Art in Tokyo on March 3rd and 4th in 2012, printed in Commons of Imagination: What Today’s Society Can Share through Manga and Animation, Agency for Cultural Affairs, Tokyo, 2012, pp77-84. I appreciate courtesy of Agency for Cultural Affairs and Ms. Yokota Kayoko, the translator of original text.

Related articles

- Sabine Fruhstuck, “Ampo in Crisis: US Military’s Manga Offers Upbeat Take on US-Japan Relations,” The Asia-Pacific Journal

- Matthew Penney, “Nationalism and Anti-Americanism in Japan—Manga Wars, Aso, Tamogami and Progressive Alternatives,” The Asia-Pacific Journal

- James Shields, “Revisioning a Japanese Spiritual Recovery Through Manga: Yasukuni and the Aesthetics and Ideology of Kobayashi Yoshinori’s ‘Gomaism’” The Asia Pacific Journal

- Yuki Tanaka, “War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The humanism of his epic manga,” The Asia-Pacific Journal

Notes

Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, Economic survey of Asia and the Far East 1947 , United Nations, Shanghai, 1948, pp15-17.

Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan, Inc., “Nihon Eiga Sangyō Tōkei (Data Statistic of Motion Picture Industry in Japan)” accessed on April 5, 2017. Regarding the number of American movie productions, See Tim Dirks. “Film History of the 1960s.” http://www.filmsite.org/60sintro.html Accessed on April 29, 2017. According to UNESCO, the countries producing the largest number of films in 2013 were India, followed by Nigeria, the US, China and Japan. See here.

Uemura Tadashi, Henbō Suru Shakai (Japanese Society in Change), Tokyo, Makino Syuppan, 1969, p174. This is a survey by Video Research Corp. in November 1968.

Matsumoto Reiji, “Nihon de Manga ga Sakaeta Riyū (The reason manga became popular in Japan)”, in Tachibana Takashi ed. Hatachi no Koro (When I was 20: Interviews for Celebrities) vol.1 1937-1958, Tokyo, Shinchōsha, 2002, p595.

Shimizu Ikutarō, Waga Jinsei no Danpen (Retrospective of My Life), in Shimizu Ikutarō Chosaku Syū, Tokyo, Kōdansha, 1992-1993, vol14. p 423.

Kajii Jun, Sengo Nihon no Kashi-hon Bunka (Book Lenders Culture in Post-War Japan), Tokyo, Tōkōsha, 1977, pp63-65.

Shibano Kyōko, Syodana to Hiradai: Syupan Ryūtsū,,toiu Media (Book Shelf and Showing Floor: Publishing distribution as a Media), Tokyo, Kōbundō , 2009, p185.

Takekuma Kentarō and Akamatsu Ken, “Zasshi de naku Comics de Rieki wo eru Kozo ha Oil Shock ga Kikkake (Current Style of Manga Industry which profits from sales of manga books, not from magazines, since the Oil Crisis)“, Accessed on April 5, 2017.

“Manga Gyōkai Shinkan “Kyūjin,: Manga 16 page kansei genkō nite 3 man yen” Genkō 1 mai 1800 yen choi? (Manga industry shocked by a job offer: 16 pages 30,000 yen means 1800 yen for 1 page)” Accessed on April 5, 2017.

Takekuma Kentarō, Manga Genkōryō ha Naze Yasui noka? (Why is Payment for Manga Artists So Low?), East Press, Tokyo, 2004, pp31-34.

The United States in the 1940s and 1950s was similar to 1960s Japan in two ways. First, entertainment connected with technology as a market could be seen in publishing and films as the two major sources. Secondly, both also had a very strong middle class. The large domestic market and strong manufacturing industries meant that many middle-class people worked in factories or offices, which I think shaped the cultural background. For some time this has not been the case in some advanced industrialized countries, but it is gradually being transformed.

Koyama Masahiro, “Wasure sarareta Tōei Dōga Mondai Shi (A Lost History of Toei Animation Problem)”, Magma, vol. 11, Tokyo, Studio Zero, 2003. Reprinted in the link, accessed on April 5, 2017.

JANICA, “Anime Seisakusha Jittai Chōsa Houkokusyo 2015 (Research on Labor Situation of Animation Creator 2015)“, issued April 28, 2015. Accessed on April 6, 2017.

“Shinjin Animator no Gessyū wo Seikaku ni Shitte Imasuka? (Do you know the income of new animators?)“, Animator Web Report, issued on February 25 2010. Accessed on April 6, 2017.

“Seiyū, Zankoku Monogatari (Misery of Voice Actors) ” Syūkan Tōyō Keizai, vol. 6717, April 1. 2017, p60.

“Utage no Uragawa (Another Side of the Boom) ” Syūkan Tōyō Keizai, vol. 6717, April 1. 2017, p39.

Kamiyama Kenji, “Mada Anime ha Sangyō ja nai (Animation in Japan has not yet reached the level of “Industry”)” , Syūkan Tōyō Keizai, vol. 6717, April 1. 2017, p44.

“Ijigen Hit no Nakano Hito ga Kataru Chance to Kikikan (Hitmakers state opportunities and sense of crisis)” Syūkan Tōyō Keizai, vol. 6717, April 1. 2017, p40.

On circulation of all Japanese manga magazines, see the website of JMPA (Nihon Zasshi Kyokai, Japan Magazine Publishing Association), Accessed on April 6, 2017.

Nihon Chosya Hansoku Center (Promotion Center for Authors in Japan) “Syotensū,no Sūji (Trend of the number of bookstores)” Accessed on April 6, 2017.

Media and Content Industry Division in METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), “Content Sangyō no Hatten to Genjō to Kongo no Hatten no Hōkōsei (Contemporary situation and Future Development of Content Industry)”, p.5, 3. Accessed on April 7, 2017.

Dan Grunebaum, “Is Cool Japan Going Cold?”, Newsweek, Japanese edition, issue June 13, 2012, p52.

Eiji Oguma, “A New Wave Against the Rock: New social movements in Japan since the Fukushima nuclear meltdown,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 14, issue 13, No 2; July 1, 2016.