Introduction

Who could fail to be deeply moved on watching the recent events at Standing Rock, North Dakota, when on December 4 the Army Corps of Engineers ordered a halt to the planned construction of an oil pipeline beneath the waters and soil of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe following months of confrontation and attempts by the American state, bolstered by private security firms, to evict the “water protectors” encampment by force and to crush the resistance?1

The security firms, also present in such spots as Iraq and Afghanistan thanks to government contracts, protect the Dakota Access pipeline for Energy Transfer Partners, which is supported by loans from, among others, Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ and Mizuho Bank.2 President-elect Trump, reported to have a stake in the company, has made clear his support for the project.3 The resistance, beginning with a tiny group of tribal youth,4 fired by determination to protect sacred soil and water and armed with social media skills, eventually joined by cascades of indigenous peoples and environmentalists from throughout the continent, received a dramatic reinforcement in the eleventh hour in the form of veterans from all branches of the U.S. military. Many came in fatigues, but unarmed, to honor the principle of nonviolence declared by the Standing Rock leadership and to help them protect “our water, our sacred places, and all living things.”

Many referred to the oath they had taken when they entered the military, to defend the Constitution and the American people from “enemies foreign and domestic.”5 Wesley Clark, Jr., co-organizer of the group Veterans Stand for Standing Rock, is the son of the former Supreme Allied Commander Europe of NATO. He was a first lieutenant in the Seventh Cavalry, a unit established in 1866 to assist in America’s westward expansion, most particularly by protecting white settlers from real and perceived threats from Native Americans. It was a 19th-century version of his unit’s uniform that Clark wore for the forgiveness ceremony at Standing Rock on December 4.

The speech of apology he delivered that day will go down in history for its simple eloquence. “We took your land …. We didn’t respect you…” he said, kneeling before Chief Leonard Crow Dog.6

|

Wesley Clark Jr., bows before Chief Leonard Crow Dog, Standing Rock Casino, December 4, 2016 |

Thousands of kilometres away from Standing Rock, at Takae, in the relatively remote northern reaches of Okinawa Island, a similar scene is playing out: protesters are abused with crude epithets (such as “Natives” and “Chinks,” Dojin or Shinajin), by massed ranks of riot police sent from all over Japan. They are dragged about, beaten, arrested and held for months as if dangerous terrorists. Yet their struggle is by and large invisible, even within Japan, much less beyond it, in the US. They have little hope of receiving any apology.

Watching the ceremony of truth and reconciliation in that remote American site, I was reminded of the words almost 60 years ago of then US president Dwight D. Eisenhower:

“The natives on Okinawa are growing in numbers and are very anxious to repossess the lands they once owned.”7

The desire to “re-possess,” evident even then to Eisenhower, is even more evident now. Okinawans are united as never before in the insistence that no new military facility be constructed on their land or sea or in their forest, that their lands not be taken and that those taken in the past be returned, protected and guaranteed against further encroachment. The “lands they once owned,” they will own again.

Yet it seems that on nothing is the rest of Japan so united as in the insistence on denying Okinawa any such right. The popularity of the Abe government rises with its determined efforts to crush those who make such demands.

The day will surely one day come, however, when representatives of the Japanese (and American) people will, like Wesley Clark Jr. and the veterans who knelt with bowed heads beside him at Standing Rock, seek the forgiveness of the Okinawan people for having taken their land and for having failed to respect the Okinawan people.

That day must now seem far off, but so, before December 4, it seemed to the protesters of North Dakota, too.

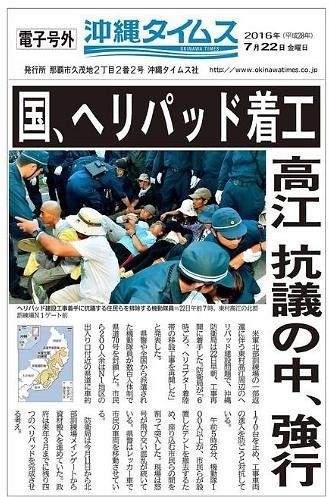

|

Okinawa Times, July 22, reports police violence at Takae |

The Okinawa Times’ North America correspondent, Heianna Sumiyo, wrote this short essay in that paper on 12 December.8 It is translated and reproduced here in a slightly author-revised version, with the author’s permission. (GMcC)

The Invisibility of the Takae Struggle

“It’s a miracle. The struggle on which we had staked our honor has borne fruit.”

December 4. When the US Department of the Army’s decision to suspend construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline was announced, a great shout went up from the indigenous peoples and environmental activists who had been carrying on the protest while camped out in the bitter cold.

The American media reported that moment as the protesters hugged one another while shedding tears of joy as a “historic victory,” but in the beginning the struggle by the Standing Rock Sioux people against the pollution of their water and their sacred earth was a lonely one undertaken by a very small number of people.

The media showed no interest, and the efforts to pursue court actions were rebuffed. The representatives of the tribe appealed before the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva to seek cancellation of the plan and respect for their first nation people’s sovereignty, saying “plans that strip away the rights of indigenous people may be legal but must not be permitted.” But the construction project was unyielding, the police set dogs upon the non-violent protestors and deployed excessive violence, brandishing their weapons. News of these events spread on social media. The protest gathered strength as well-known figures such as Bernie Sanders and Leonard DiCaprio declared their opposition to the crackdown. Interest gradually mounted. More than 10,000 telephone calls of protest were made to the White House and a protest signed by 400,000 people was handed in. More than 2,000 former servicemen and women [Vets] descended on the site in response to the call, “let us become human shields.”

For this victory won on the very last day of the deadline to evacuate the site, the tribal chair of the Standing Rock Sioux people expressed respect for the “historic decision of the Obama administration.” Yet there is a real possibility that incoming President Trump might reverse this decision.9

The outlook now is not clear, but the struggle by the once isolated indigenous people had become a “visible struggle” known to the whole country. There is one other struggle, also pitting citizens against state power, which remains in America an “invisible struggle.” It is the [Okinawan] struggle over the construction of helipads at Takae,

Okinawan Governor Onaga Takeshi, who in September 2015 explained to the UN Human Rights Council the history of the US military’s compulsory seizure of Okinawan land and called for the right of self-determination, later de facto recognized the Takae plan, describing it as a “painful decision.” He defended himself at subsequent press conferences and in the Prefectural Assembly, saying “I did not give any go-ahead,” but he has had nothing to say about the ongoing people’s struggle at Takae.

The Governor’s painful explanation seems somehow unlikely to be accepted by international society. The way that some US government officials see it is that “what is important is not whether or not he issued a plain statement of go ahead but the fact that he does not oppose the plan.”

Very soon [December 22] comes the ceremony of “return of the seized lands.” Already the US media praises the US government’s efforts over this “largest ever return” of Okinawan land.

What is it that makes Takae an “invisible struggle”? The struggle by those who have staked their honour on it continues there [as at Standing Rock] but in the absence of representatives who would stand up to the governments of Japan and the United States and say “Protect Takae.”

Notes

The Standing Rock Sioux have been emphatic about their identity as protectors (of their sacred lands and their drinking water, of “mother earth”), not protestors. Their slogan “Water is life” is replicated almost identically by the Fukushima activists summarily dismissed in their attempts to block Tepco’s contamination of the Pacific.

“We thank the tribal youth who initiated this movement,” David Archambault II, tribal chairman. http://standwithstandingrock.net/standing-rock-sioux-tribes-statement-u-s-army-corps-engineers-decision-not-grant-easement/

“Veterans apologize to Sioux tribe at Standing Rock Forgiveness Ceremony,” You-tube, 6 December 2016.

DDE [Dwight David Eisenhower, then president], “Memorandum for the Record,” 9 April 1958, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-60, vol. 18, p. 16.