Shukan Bunshun is one answer to the charge that aggressive, confrontational journalism does not exist in Japan. For over a year, the nation’s biggest-selling weekly magazine (about 420,000 audited copies) has scored a string of scoops. In January 2016, it harpooned economy minister Amari Akira over bribery claims, forcing him to quit. The following month, it exposed an extramarital affair by Miyazaki Kensuke, a politician who had been campaigning for maternity leave during his wife’s pregnancy. The same month it revealed illegal betting by Kasahara Shoki, a former pitcher with the Yomiuri Giants baseball team.

|

Shukan Bunshun, “‘I gave Minister Amari a 12-million-yen bribe’” |

The magazine’s editor-in-chief Shintani Manabu came to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in May 2016 to reveal his magic formula, which was disarmingly simple. “The reason why we get scoops is that we go after them,” he said. That drive, he implied, is rare among his contemporaries. “I proposed to a television colleague doing some research on (communications minister) Takaichi Sanae, he said. Takaichi had sparked a furor in February by “reminding” TV companies that flouting rules on political impartiality could result in the withdrawal of their broadcasting licenses. The TV companies declined, said Shintani: “So we did it ourselves and titled the piece: ‘Why we hate Minister Takaichi.’”

The role of journalism as guardian of the public interest against abuses of power has long been seen as perhaps its key function in liberal democracies. According to this view, an independent media should facilitate pluralist debate and the free flow of information about the political and economic interests that dominate our lives. A conflicting view – one prevalent in wartime Japan and in contemporary China – is that the media should primarily be an instrument of state power. The reality in many developed capitalist economies is that the media’s role is circumscribed by monopolies, political and commercial pressure and other formal and informal restrictions. Japan’s media, which was reformed after World War II to bring it closer to the “watchdog” model, is no exception. Critics have long noted another distinctive layer of formalized control over the free distribution of information in Japan: press clubs.

The Press Club System

Japan’s century-old press club system underwent what appeared to be dramatic change, however, in 2009-10. The new government of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which had declared its intention to challenge Japan’s powerful bureaucratic apparatus, began to allow journalists from magazines, cyberspace, foreign media companies and freelancers to attend regular press conferences. All of those categories of reporters had been previously banned from full participation at official press events, which have for decades been dominated by an umbilical relationship between lawmakers, bureaucrats and Japan’s largest TV and newspaper outlets. The DPJ move was widely expected to strengthen the watchdog function of the media and push Japan’s political institutions toward reform.

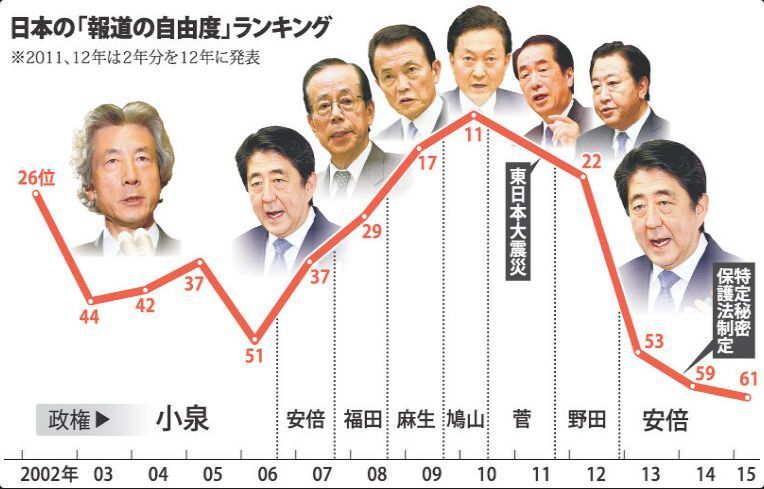

The shift was welcomed by, among others, media watchdog Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF), which hoisted Japan to No.11 in its 2010 global index of press freedom, a long way from its dismal ranking of No.51 four years previously, when RSF noted an “extremely alarming” erosion of media liberties. As I write, Japan is in 72nd place1 (out of 180 countries) and quickly retreating from that turn-of-the-decade high point. Reporting on the Fukushima nuclear crisis and the return of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in 2012 has helped weaken open media enquiry. An association of freelance journalists posing a de-facto challenge to the press club system has largely failed to make an impact on the major media. Above all, the press clubs themselves continue to dominate newsgathering, with potentially profound implications for media freedom.

|

Graph of Reporters Sans Frontières ranking, 2002–2015, Mainichi Shinbun, 12 February 2016 |

Japan’s mass media is sophisticated and lively. The country is home to a powerful public service broadcaster, the ad-free, quasi-governmental Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai (Japan Broadcasting Corp: NHK), and the world’s most widely read newspapers, led by the Yomiuri Shimbun, which has a total combined print circulation of about 9.5 million – many times that of the venerable New York Times.2Japanese publications include a mass-selling communist and religious daily newspaper, millions of manga comics every year, some dealing with highbrow topics such as economic models, history and even Marxism; and boasting a readership in the hundreds of thousands for both scandalous tabloid weeklies, such as Shukan Bunshun, and monthly magazines.3 Japan has one of the world’s highest (80 percent) internet diffusion rates, and (since 2012) full nationwide digital broadcasts.4 Unlike in many Asian countries, all forms of freedom of expression are legally protected, thanks to the 1946 Constitution. Article 21 specifically notes: “No censorship shall be maintained.”

Yet that diversity and openness is deceptive. The news media in Japan is shackled by institutional constraints: a widely criticized system of information distribution that encourages journalists to collude with official sources, discourages independent lines of enquiry and institutionalizes self-censorship. Mainstream reporters shun critical stories about Japan’s imperial family, war crimes, corporate wrongdoing, the death penalty, religion and other issues, striving to achieve a bland consensus that only rarely troubles the nation’s political and economic elite.

It hardly needs to be stated at the outset that this does not imply uncritical support for any idealized watchdog media outside Japan – as Laurie Anne Freeman notes, such a system does not exist.5 Whatever its problems, Japan’s contemporary media has made strides from the prewar and wartime period when it largely became a tool of the authoritarian, militarist state.6 After 1945, overt ideological control over the mass media was relaxed. The Allied occupation (1945 – 52) initially saw the media as a conduit for its policies of breaking with the imperial wartime regime and liberalizing and revitalizing the capitalist state.7 When the occupation ended, newspapers and television, responding to popular support from below, arguably played an independent role in some of the key national debates of the postwar era.

The Prewar and Postwar Systems

|

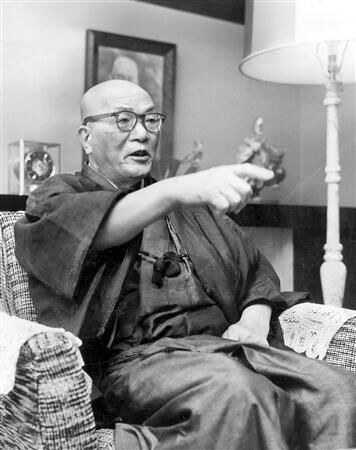

Shoriki Matsutaro |

Nevertheless, there is much overlap between the prewar and postwar media. As Susan J. Pharr notes: “Most of Japan’s key media institutions of the 1990s were…fully in place in the period of military ascendency and strict censorship from the 1930s through the end of World War II.”8 The Allied reformers, initially strongly influenced by liberal New Dealers, veered away from radical reform of media institutions and preserved and even strengthened the prewar structures. Purged newspaper managers and editors, led by Shoriki Matsutaro, president of the Yomiuri Shimbun, were allowed to resume their old positions. Hierarchical controls over editorial policy were encouraged to combat the growing problem of left-wing militancy. “Continuity, rather than discontinuity, became the dominant theme” of postwar media history,” concludes Hanada Tatsuro, a media scholar at Waseda University.9

Although a legacy of the prewar period, press clubs have become even more important since 1945. Essentially newsgathering organizations attached to the nation’s top government, bureaucratic and corporate bodies, the clubs were established in the 1890s by journalists seeking to strengthen their collective position by demanding access to official information. During the war, they became part of a top-down system dedicated to disseminating official views. For most of the postwar era, they have been closed shops, banned to all but journalists working for Japan’s top media. Freelancers, tabloid and magazine journalists and foreign reporters were excluded for decades and have only recently started to gain entry.

The Japanese Newspaper Publisher & Editors Association, the main industry to benefit from them, defends the clubs, commending them for their accuracy and calling them “voluntary institution[s]” of journalists “banding together” to “work in pursuit of freedom of speech and freedom of the press.”10 In reality, critics say, they are elite news management systems, channeling information directly from what Herman and Chomsky (1989) call the “bureaucracies of the powerful” to the public, locking Japan’s most influential journalists into a symbiotic relationship with their sources.11 Journalists are little more than well-paid mouthpieces, in this view, “co-conspirators in the cartelization of the news,” according to Freeman. One of their best known critics famously inverts the declared aim of press clubs: Although apparently designed to facilitate the dissemination of information to the Japanese public, says Karel Van Wolferen, the press club system “in fact is the most serious barrier to this dissemination.”12

In late September 2009, however, all this seemed up for grabs. Reporters in Japan enjoyed that rarest of events: a genuinely open encounter with a government official. Okada Katsuya, foreign minister with the newly elected Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), announced at his first press conference in office that all present, including members of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan (FCCJ), Japanese freelancers, magazine writers and Internet scribes would be allowed to ask unscripted questions.13 Okada then answered everyone, running over the allotted time by about 30 minutes – at one point preventing a foreign office official from calling time.

The Okada event was exceptional because Japanese cabinet ministers are normally shielded from journalists behind thick ramparts. The first line of defense is the bureaucrats who coax, nudge and steer journalists into preferred topics and away from political landmines. The second, most controversially, are the journalists themselves. As press club members, reporters for the elite media operate in isolation, with their own set of codified rules and practices.14 In return for exclusive access to information and sources, the journalists pull their punches, discouraging what might otherwise be a more adversarial relationship.

The Position of Foreign Journalists

Most foreign correspondents collide with this system at some point. In 2002, when then Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro made his historic visit to North Korea, not one Tokyo-based reporter from the 15 European Union member nations was allowed to accompany him. During the investigation into the 2000 murder of British hostess Lucie Blackman, foreign reporters were barred from police press conferences.15 Both incidents were cited in a landmark European Commission report in 2002, which criticized the press club system for impeding reporting “of events of widespread international interest and significance.”16

|

PM Koizumi Junichiro meeting Kim Jong-il, September 2002 |

Years of pressure by the Foreign Press in Japan (FPIJ), the main conduit for information between official Japan and the foreign media, resulted in the production of a letter by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) in 2002, in principle essentially guaranteeing foreign reporters the same rights to ask questions as Japanese journalists. Though little noticed at the time, the letter was an important marker in the fight for better access. “When enforced, it neutralized the press club system,” says Richard Lloyd Parry, then head of the FPIJ.17

Japan’s government is hardly alone in stage managing meetings with the media, or in giving favored journalists proprietary access to information and sources.18 One need only view the clubby, mannered affairs run by the US White House for evidence. Elite sources are favored, to one degree or another, across the world. Japan’s press clubs are very effective, however, in systematically co-opting journalists into a shared worldview with their sources, and blocking access to “outsiders” who might prove disruptive. Day in, day out, Japanese reporters share a symbiotic relationship with elite bureaucrats and politicians. Questions are often shared between competing media and even with journalistic sources in a pattern that clearly works against the public interest. Two examples should illustrate this point.

The Press and the Imperial Household

In 2007, Crown Prince Naruhito was set to embark on a trip to Mongolia. Following protocol, the Imperial Household Agency (IHA) invited a small number of foreign correspondents to a pre-trip press conference. For the IHA, such conferences are a way of publicizing imperial foreign tours but they also involve an element of risk. So the agency insists on running events so controlled and scripted, with questions submitted – and sometimes refused – weeks in advance – they are of little interest to the foreign press except as an opportunity to see members of possibly the world’s oldest hereditary monarchy up close.

Prince Naruhito himself, however, had managed to crack the stultifying embrace of the IHA in 2004 when he told reporters that the career and personality of his wife, Princess Masako, had been “denied”. Her mental health and the couple’s relationship with the Imperial House had since been the subject of some speculation. The IHA’s screening ensured that we were discouraged from asking about these topics, or why the prince would again be traveling without his wife on an official foreign engagement. But unusually for an event often timed down to the last minute, the scripted questions ran out before the end of the press conference and an IHA official asked if there was another.

For a journalist this was a unique opportunity to get under the rampart of the IHT defenses and ask a direct question to a member of the imperial family, so I immediately put up my hand. I wanted to hear more about the health of Princess Masako. The IHA official ignored me. The seconds ticked by and another foreign reporter, Eric Talmadge of the AP news agency, also raised his hand. The official looked uncomfortable and glanced pleadingly at the row of Japanese reporters sitting opposite him, heads down. Finally, after the longest time one obligingly if very reluctantly put her hand up. “Ok, shall we have ladies first?” said the official rhetorically.

What was instructive about this incident was that the reporter had not seen me as a professional colleague in our collective struggle to get more information from the IHA in the interests of the general public.Instead, she considered it necessary to rescue the IHT official from possible embarrassment and save him from the troublesome interloper. Of course, foreign reporters are less sensitive to the institutional taboos surrounding Japan’s imperial household; all the more reason – and in everyone’s interest – why they should be encouraged to ask probing questions.

The Press and the Death Penalty

During a rare media tour of Japan’s secretive gallows in 2009, the same strategy of blocking “outsiders” was evident. The Justice Ministry had reluctantly allowed the tour, possibly under pressure from abolitionist Justice Minister Chiba Keiko, who was apparently trying to trigger debate on the death penalty. Many Japanese freelance reporters applied. As then chairman of the FPIJ, I lobbied unsuccessfully on behalf of our membership. Meanwhile, elite journalists in the Justice Ministry Press Club were being briefed to prepare for the morning of Aug. 27, and to keep the date secret.

Sanitized pictures, without the all-important hangman’s noose, subsequently ran on NHK and a handful of other media outlets, along with anodyne reports by trusted journalists. Not surprisingly, the death penalty debate never materialized. Support for hanging in Japan remains at a record high.19 The press club journalists will undoubtedly say they got the best possible information to the public. But it is possible to characterize this episode in a very different way: elite journalists collaborating with elite bureaucrats to stage-manage a difficult story about an uncomfortably controversial issue.

The Press, the Journalist Cartel and the DPJ

In both these cases – and countless others – journalists who are members of these clubs aligned themselves with the people whose statements they’re supposed to be reporting so that instead of a contentious relationship between the press and official sources, you get something that is more clubby and collaborative; a cartel of rich media groups that “rewards self-censorship, fosters uniformity and stifles competition,” concludes Jonathan Watts, former Tokyo bureau chief of The Guardian newspaper.20

The DPJ’s ascent to power seemed to signal a break with this cartel. The pledge of more open access to the media was led by Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio, who said he would scrap brief, informal prime ministerial meetings with a limited number of select reporters and make press conferences “open to everyone.”21 This was partly self-interest since the DPJ felt Japan’s closed media system favored its Liberal Democratic Party rivals.

Hatoyama also revealed an open secret: the existence of a slush fund in the Kantei that for years had reportedly been used to curry political favor among journalists and television commentators.22 The Economist noted the “extraordinary silence” from most of Japan’s mass media on Hatoyama’s revelation; more evidence, said the weekly, of the media’s “central role in Japan’s longstanding political dysfunction.”

It’s important not to undervalue the efforts of Hatoyama, Okada, and Kamei Shizuka, minister in charge of banking and postal services (who had to hold separate meetings with reporters after members of the press clubs refused to share access with other journalists). After a fight, reporters for foreign wire services such as Bloomberg, Dow Jones and Reuters have been allowed basic access to Diet and other power centers. Freelancers have wider access. “But the system itself has stayed intact,” says Jimbo Tetsuo, a veteran freelance journalist. Moreover, since 2011, it has retrenched.

Rolling Back Media Freedoms

The LDP’s return to power in late 2012 (in coalition with Komeito) has seen a striking reversal in media openness. LDP officials have used a range of informal methods to limit exposure to reporters outside the press club system. Freelancers are discouraged from using media facilities and not notified by government handlers of upcoming press events;23 senior officials seek out established reporters and avoid or shun others; media meetings with the prime minister have been shortened. Prime Minister Abe’s press conferences begin with “extraordinarily long” opening statements, often occupying half the allotted time, followed by pre-submitted questions from handpicked journalists.24

“I’ve attended every single press conference held by Prime Minister Abe and I’ve never had an opportunity to ask a question,” says Jimbo. Even mild critics of the coalition, such as the Asahi group have been sidelined. All of this has helped Abe avoid scrutiny, concludes Jimbo. “The only place he faces harsh questions is in the Diet, and only part of that is on TV.”25 Perhaps more worrying, the journalists affected by these rules have not challenged them. “Members of the Prime Minister’s Office Kisha Club have never taken any collective action on this issue, while other Internet and foreign media who sit in the press conference, but do not have club membership, can do very little about it,” says Okumura Nobuyuki, a Professor at Musashi University of Tokyo and a former news reporter and producer at TV Asahi.

Occasionally, a shaft of light peeks though. During a press conference by Abe at the United Nations in New York on September 29, 2015, for example, journalists submitted advance questions and the prime minister read from a teleprompter. A reporter for the Reuters news agency, “unaffected by the professional strictures that keep his Japanese counterparts in line,” broke press club protocol, however, by asking the prime minister an unscripted question on whether Japan intended to accept more refugees from Europe.26 Forced to speak off the cuff, Abe gave a confusing answer that suggested he had not seriously considered the refugee issue. His reply was reported extensively around the world, but mostly ignored by the big media in Japan.27

In another incident, Eriko Yamatani, Chairman of the National Public Safety Commission & State Minister in Charge of Abduction Issues, gave a press conference at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan on September 25, 2014. Briefed to discuss the abduction issue, Yamatani found herself instead facing a string of questions about her alleged links to a far-right pressure group. Again, the controversy was mostly ignored by the Japanese mainstream media, though reported in some of the weekly press. Afterwards, government ministers drastically cut their attendance at FCCJ press conferences.28

The failed attempt to reform the press club system

The failed attempt to reform the press club system is cited as a reason for Japan’s declining media-freedom rankings. The latest (2016) Freedom House rankings put Japan 44th in the world; as mentioned above, RSF recently ranked Japan at 72 out of 180 countries, (that ranking was widely criticized as too harsh). Japan is one of four countries that fell out of the “full democracy” category (along with South Korea, Costa Rica and France) in the latest Democracy Index, published by The Economist. A withering report by UN Rapporteur David Kaye in April 2016 warned of “serious threats” to the independence of the media. “A significant number of journalists I met feel intense pressure from the government, abetted by management, to conform their reporting to official policy preferences,” he said. “Many claimed to have been sidelined or silenced following indirect pressure from leading politicians.”

That verdict might have triggered a robust official response; a pledge, perhaps, to launch an enquiry into the health of the nation’s Fourth Estate. Instead, Foreign Minister Kishida Fumio blamed the messenger. “The Japanese government’s explanation was not sufficiently reflected” in Kaye’s report, he lamented. One way to rectify this might have been for communications minister Takaichi Sanae to have met Kaye, but she was apparently “too busy” in the national Diet. Kaye’s press conference, though given widespread coverage in the liberal media in Japan (notably TBS, TV Asahi, and the Tokyo Shimbun) was all but ignored by the country’s most powerful broadcaster, NHK, and its leading newspaper, the Yomiuri Shimbun – somewhat proving his point.

Recent controversies

This follows a pattern evident throughout many recent controversies, including the Fukushima nuclear crisis. That crisis triggered a string of demonstrations throughout the summer of 2011, climaxing with an estimated 60,000 people in Tokyo’s Meiji Park on 19 September. One study found that 16 demonstrations received a total of 686 words in the Yomiuri Shimbun.29 NHK could more often than not be bothered to send a camera to Yoyogi Park, a stone’s throw away, to interview protestors there.

|

Demonstration in Meiji Park, Tokyo, 19 September 2011 |

A series of large anti-nuclear demonstrations in front of the National Diet building beginning on 29 March 2012 were also initially ignored by the mainstream Japanese media. Organizers relied on online social media and word of mouth to spread the word. A crowd estimated by organizers at 170,000 people rallied outside the prime minister’s official residence on 29 June 2012, probably the largest demonstration in Tokyo since the Vietnam War era. The figures were of course disputed by the police, and by many of the journalists who were there. There was, however, one conspicuous absence. The Yomiuri didn’t mention any figures, because it didn’t cover it.

Fukushima and its aftermath were widely cited as key events in Japan’s declining media freedom. Hanada of Waseda University says Japanese journalism effectively surrendered (haiboku) in Fukushima.30 To cite some of the more serious problems, television pictures of the explosion of the plant’s reactor one building were delayed for over an hour while broadcasters determined what to do with them. During the week after the Fukushima accident it seemed to many that the most accurate information was coming from outside Japan, particularly from Washington. Japanese experts connected to the nuclear industry filled the airwaves with false assurances about the safety of the Daiichi plant. Critics were effectively banned. Public service broadcaster NHK relied on openly pronuclear experts to explain what was happening.31 According to one careful study, there was just a single notable appearance on TV by an academic critical of nuclear power.32 Fujita Yuko, a former professor of physics at Keio University, speculated on Fuji TV on the evening of March 11, 2011 that the Daiichi reactors were in a “state of meltdown.” He was never asked back.

|

Dump of contaminated soil, Fukushima |

Journalists covering the crisis via the press clubs quickly settled on the explanation that “partial” fuel melt was suspected, a line maintained for two months until operator Tokyo Electric Power Co. confirmed the triple disaster. When it was reported in the foreign media that information on the diffusion of radiation had been withheld, local newspapers took weeks to follow up.33 In Fukushima itself, elite Japanese journalists evacuated en masse from Minami-soma city and from the wider threat of radiation fallout on March 12, even as their companies were publicly reassuring millions of Japanese that the area was safe. They returned some forty days later.34 When questioned afterward, the journalists said it was “unsafe” in the zone, which is true, but does not explain why they did not use their considerable resources to protect themselves while reporting from the site, or why they did not try to out-scoop their rivals.35 Suganuma Kengo, chief editor of Tokyo Shimbun, compared Fukushima reporting to Japan’s wartime-era, when military dispatches (daihonei happyo) lying about the doomed war effort were carried word-for-word in the national media.36 “Throughout the war, newspapers reported exactly what they were told and that’s why the war went the way it did,” he says.

The presence of the Tokyo Shimbun (which has marginally increased circulation since 2011), the Asahi, Mainichi as well as the rambunctious tabloids and weeklies suggests that critical journalism is still alive and kicking in Japan – with important qualifications. Tokyo Shimbun is a regional newspaper with a morning circulation of roughly 500,000, a fraction of the Yomiuri, the Asahi’s 7.2 million, and about a third of the Sankei Shimbun, the national newspaper on the other end of Japan’s political spectrum. The weeklies, barred from access to the press clubs, love to poke a stick in the eye of the powerful but they are just as likely to wield the stick against others. It was Bunshun that led the witch-hunt against Uemura Takashi, the embattled Asahi journalist blamed by the right for starting the ‘comfort women’ controversy three decades ago. Shintani admits he pulls his punches on the imperial household, partly out of fear of sparking violent retaliation from the far right of the kind that led to the unsolved 1987 murder of Tomohiro Kojiri, an Asahi journalist and colleague of Uemura’s. “But it’s also about the reaction of our readers,” Shintani said. “We are a Japanese magazine and we love our country, so we wouldn’t want to do anything that breaks the bond of trust we have established with our readers.”37

The Asahi and the politics of retraction

As for the Asahi, Japan’s flagship liberal newspaper, has also taken a beating over Fukushima. Among Japan’s daily newspapers, the Asahi (and Tokyo Shimbun) have been the most persistent post-Fukushima critics of TEPCO and the nuclear industry. The Asahi’s critical coverage arguably climaxed on May 20, 2014, when it published a story based on the leaked testimony of Yoshida Masao, the manager of the Daiichi plant during the 2011 meltdown. The scoop, (所長命令に違反), claimed that 650 panicked onsite workers had disobeyed orders and fled during the crisis.

The Asahi’s claim, challenging the view of the workers as heroes who risked their lives to save the plant, was strongly contested by the industry, the government, and Asahi rivals, particularly the right-wing Sankei, which blamed the confusion at the plant on March 15-16, 2011 on miscommunication. Finally, on September 11, 2014, Kimura Tadakazu, the Asahi’s president announced the retraction of the article, the dismissal of the paper’s executive editor Sugiura Nobuyuki and punishments of several other editors. The highly damaging announcement pleased Asahi critics and stunned journalists at the newspaper who say they were kept in the dark beforehand.38

Lawyers, journalists and academics expressed puzzlement at Kimura’s retraction. While the factual details of the Yoshida testimony were open to interpretation, there was little doubt that despairing onsite plant workers had abandoned their duties during the worst of the crisis.39 “The content of the article and the headline were correct,” insisted Kaido Yuichi, a lawyer and opponent of nuclear power who blamed the retraction on political pressure.40 An independent press monitor might have cleared up the controversy but the Asahi relied on its in-house Press and Human Rights Committee to probe the story and discipline those behind it. “In Japan, there is no such press council or professional organization in place to support journalists such as there would be in the US, for example,” lamented journalist Kamata Satoshi of the newspaper’s conduct. “The press club system is completely obstructing the development of professionalism within Japanese journalism.”41

|

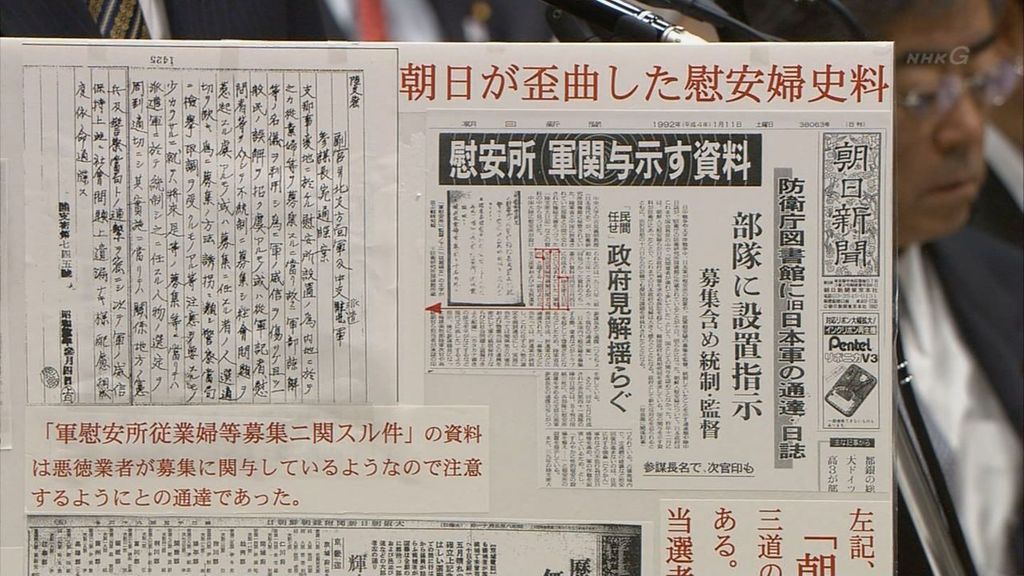

Poster of Asahi front page labelled “historical records on comfort women distorted by Asahi,” presented by MP Nakayama Nariaki in Diet, March 2013 |

The Asahi’s mea culpa followed another even more damaging retraction a month earlier over a series of articles in the 1990s on so-called “comfort women” – Asian women herded into wartime Japanese military brothels. Yoshida Seiji, the source for some of these stories had long been discredited and the Asahi’s retraction was years overdue. Yet, the reaction on the political right was not only to question the newspaper’s entire reporting reputation but to blame it for damaging Japan’s reputation abroad and poisoning ties with its neighbors.

In the right’s narrative, the Asahi articles triggered the 1993 Kono Statement, acknowledging the army’s role in forcing the women into sexual slavery. In 2007 U.S. House Resolution 121 called on Japan’s government to “formally acknowledge and apologize for the comfort women episode.” In fact, the Yoshida memoir and Asahi’s reporting of it had nothing to do with Resolution 121 – according to the group of experts who helped write it. The scholars were moved to make this clear when the liberal Mainichi newspaper reported exactly the opposite after interviewing them. “All of us were astonished,” they recalled.42

The Yoshida controversy embroiled foreign reporters too. Several of us were approached by Japanese news organizations asking the same question: Wasn’t the Asahi coverage of the comfort issue a major influence on reporting by foreign coverage? The answer was no. Yoshida Seiji was before our time. Over the last decade, however, we have interviewed many comfort women first hand, in South Korea and elsewhere.43 These points, and the rebuttals by the scholars who wrote Resolution 121, appear to have no impact on the right’s narrative in Japan. Journalists who continued to write critically on the comfort women issue were subject to harassment and threats.

Carrot and Stick

The attacks on the Asahi appear to be part of a broader assault against liberal journalism – in the domestic and foreign media. The government has sent diplomats out across the world to complain to history professors and journalists. In one incident, officials with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs attempted to clumsily steer foreign journalists away from a Japanese academic critical of the government’s stance on the war.44 In another, Japanese officials accused Germany’s largest business newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, of carrying pro-Chinese propaganda against Japan.45

This intolerance of criticism often manifested itself as ham-handed intervention in the media’s affairs. During campaigning for the December 2014 snap election, for example, the LDP demanded “fair and neutral” reporting by the domestic media, and effectively boycotted Asia’s oldest foreign correspondents’ club, the FCCJ in Tokyo. As I write, neither the foreign nor defense minister have made an appearance at the FCCJ since 2012; it took 19 months to get Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga, who tried (but failed) to have the questions scripted beforehand.46 It need hardly be said that Japanese politicians are under no obligation to prostrate themselves before the foreign press, but such micromanaging hardly indicates a confident administration.47

In March 2015, political commentator and well-known Abe critic, Koga Shigeaki, abruptly quit his regular slot on Asahi TV’s nightly news show, Hodo Station, after executives apparently succumbed to pressure from the Abe government during debates on the contentious security bills. Koga’s silencing highlighted the concerted carrot-and-stick campaign by the government to cow the media: a mix of sharp-elbowed tactics against its critics and the dedicated wining and dining of media executives.48

It seems only sensible to speculate if these regular meetings between media bosses and Japan’s most senior politicians are related to the disappearance from the airwaves in March 2016 of Japan’s most outspoken liberal anchors: Furutachi Ichiro, the salty presenter of evening news show “Hodo Station”, Kishii Shigetada, who had a regular slot on rival TBS, and Kuniya Hiroko, who helmed NHK’s flagship investigative program “Close-up Gendai” for two decades.

Producers connected to Furutachi’s show relate months of pressure against his on-air criticism of the Abe government.49 A climax of sorts came after Koga’s on-air comments. Koga’s aim, he insists, was to rally the media against government interference. Instead, the show’s producer, TV Asahi, apologized and promised tighter controls over guests.50

Kishii used his nightly spot on News 23 to question legislation in the summer of 2015 expanding the nation’s military role overseas. His on-air fulminations prompted a group of conservatives to take out newspaper advertisements accusing him of violating impartiality rules for broadcasters. In January 2016, he announced he was stepping down. “Nobody said directly I was going because of my comments – that’s not how it works,” says Kishii.51 He blames a whispering campaign by Suga, who may also have been behind the sacking of Kuniya. She had the temerity to ask him, in a live interview, unscripted questions on the possibility that the new security legislation might mean Japan becoming embroiled in other country’s wars.

It is in its suppression of NHK that the government’s hostility to critical, independent journalism is most vividly observed. Like British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was notoriously suspicious of the BBC’s supposedly liberal bias, Abe has never trusted Japan’s most powerful broadcaster and has entered into conflict with it in the past.52 NHK is vulnerable to pressure because its 600-billion budget is funded from license fees, subject to parliamentary approval. When Abe returned to power, one of his government’s first moves was to pack the company’s 12-member board with four conservative allies led by Director-General Momii Katsuto.53 The Abe appointees have repeatedly denied editorial interference – as they must.54 But one of the outcomes of their stewardship has been to pressure media workers toward greater self-censorship. The clearest example of this is the creation of the “Orange book,” an in-house stylebook of censorship for NHK’s international broadcasting arm that specifies how NHK would side with conservatives in the government, in some cases even in ways that are at odds with Japan’s official position.

|

Yasukuni on the 70th anniversary of Japan’s WWII surrender |

For example, the book instructs editors, translators and journalists to avoid using the expression ‘so-called comfort women’ and “in principle” to avoid giving explanations of what they were: “Do not use ‘be forced to,’ ‘brothels,’ ‘sex slaves,’ ‘prostitution,’ ‘prostitutes’ etc.”55 While careful not to deny the Nanjing Massacre, the book says the 1937 destruction of the Chinese capital by the Imperial Japanese Army must be referred to only as “the Nanjing Incident”. “‘The Nanjing Massacre’ is used only when directly quoting remarks made by important people overseas etc., when the fact that it is a quotation must be made clear.” In reference to Yasukuni, the Shinto shrine that venerates Japan’s wartime leaders along with its 2.4 million war dead, NHK employees must avoid English expressions such as “war-related shrine,” “war-linked shrine” and “war shrine”. This tilt toward making Japan’s broadcaster a tool of government propaganda could hardly have been a surprise since it was signaled by Momii on his appointment.56 “Avoidance of controversy, pandering to audiences, parochial nationalism; these appear to be the three basic tenets of NHK’s current operations,” concludes media scholar Hayashi Kaori.57 “They are diametrically opposed to the original spirit of public service broadcasting as it developed after World War II.”

This brief survey does not exhaust official attempts to roll back the autonomy of the media in Japan. The passage of the State Secrets Law in 2014 expands the bureaucratic state’s discretion to keep information under wraps. Breaching secrets will be punishable by up to 10 years in prison and up to a ¥10 million fine. The law triggered protests from Human Rights Watch, the International Federation of Journalists, the Federation of Japanese Newspapers Unions, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, the FCCJ and hundreds of Japanese academics. An expert for the UN Human Rights Council said it carried “serious threats to whistleblowers and even journalists reporting on secrets.”58

Members of the Abe government have hinted at revoking broadcasting licenses of overly critical networks.59 Allies have openly proposed shutting down newspapers deemed hostile to government policies.60 Low-level harassment of media professionals continues. In April 2014, the LDP summoned NHK and Asahi TV executives to dress them down for recent reporting failures, in a show of official force clearly designed to intimidate.

Conclusion

In hindsight, the 2009-10 reforms of Japan’s press club system proved to be a false dawn. The promise of more open access to sources, let alone the dismantling of the institutional machinery of the press club system, has all but evaporated. Watchdog journalism, always an embattled project, has retreated as conservative forces aligned to the state demand a less autonomous line from the nation’s major media. Similar struggles rage across the world,61 but Japan’s defense has been weakened by self-censorship and the press club system with its cosseted and co-opted army of well-paid journalists.

It is possible to question Japan’s plummeting performance in media rankings since 2011 and indeed many have. For all its faults, Japan is still among the safest and freest places in the world for reporters. Journalists are not being killed or imprisoned for doing their jobs. Does Japan really deserve to be lower than South Korea, where journalists are being intimidated or, like the Sankei’s Kato Tasuya, arrested for writing stories, and where prosecutors recently indicted a professor of Japanese literature who wrote a book complicating the nation’s official narrative about the former comfort women?62 Inevitably, such questions are forcibly put to those who write about Japan’s slide down the press freedom tables. “If you think Japan is so bad, why don’t you go and live in China,” is one typical comment. The point surely is, how to stop Japan becoming more like China.

Notes

The Seikyo Shimbun, a newspaper run by religious group Soka Gakkai, claims a daily circulation of 5-6 million. Shimbun Akahata, the daily newspaper of the Japanese Communist Party, has a claimed circulation of 1.6 million.

See Laurie Anne Freeman’s “Japan’s Press Clubs as Information Cartels,” Japan Policy Research Institute, Working Paper No.18, April 1996. (October 6, 2011). Also see Closing the Shop: Information Cartels and Japan’s Mass Media, Princeton University Press (2000). And DeLange, W., A History of Japanese Journalism: Japan’s Press Club As the Last Obstacle to a Mature Press, Routledge (1998). On differences with the US media, Freeman notes: The institutional machinery for cartelizing official news is virtually absent in the US…It is at this fundamental level – the initial source – that the two systems vary so dramatically. While the US media industry shares common institutional features in the ‘downstream’ stages of report – notably in the role of concentrated media groups in the dissemination of news – there is nothing similar at the ‘upstream’ stages. And it is here that the two systems are sufficiently distinctive to represent not simply differences in degree but differences in kind.”

For an account of prewar and wartime control over the Japanese media, see Kasza, G., The State and the Mass Media in Japan: 1918-1945, University of California Press (1993).

Pharr, S.J., “Media and Politics in Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives” in Pharr and Krauss (ed.) Media and Politics in Japan, University of Hawaii Press (1996).

Hanada, T., “The Stagnation of Japanese Journalism and its Structural Background in the Media System,” in Bohrmann et al. (eds), Media Industry, Journalism Culture and Communication Policies in Europe, Halem (2007).

Karel Van Wolferen, Karel, The enigma of Japanese power: people and politics in a stateless nation, Tuttle, 1993.

See Laurie Anne Freeman’s “Japan’s Press Clubs as Information Cartels,” Japan Policy Research Institute, Working Paper No.18, April 1996. (October 6, 2011). Also see Closing the Shop: Information Cartels and Japan’s Mass Media, Princeton University Press (2000). And DeLange, W., A History of Japanese Journalism: Japan’s Press Club As the Last Obstacle to a Mature Press, Routledge (1998).

This had been happening for years: In 1964, LA Times reporter Sam Jameson was famously barred from a police press conference following the stabbing of US Ambassador Edwin O. Reischauer.

“Press clubs stymie free trade in information: EU,”The Japan Times, Nov. 7, 2002. Available online. (April 3, 2015)

Laurie A. Freeman, “Japan’s Press Clubs as Information Cartels,” Japan Policy Research Institute, April 1996.

Feigenblatt, Hazel and Global Integrity (eds), (2010) The Corruption Notebooks. vol.VI, Washington: Global Integrity.

Ibid. See also, Brasor, P., “Abe raises eyebrows when he’s off script,” The Japan Times, October 24, 2015. At press conferences with Abe Shinzo, NHK reporter Hara Seiki is selected, even when he doesn’t have his hand up.

McNeill, D., “Japan pulls up the drawbridge as refugee problem grows,” The Irish Times, October 3, 2015. Available online. (Nov.1, 2015).

No.1 Shimbun, “Behind the Barricades,” Dec. 28, 2014, Available online here (last accessed on October 20, 2016).

Satoh K., “What Should the Public Know?: Japanese Media Coverage on the Antinuclear Movement in Tokyo between March 11 and November 30, 2011,” (Accessed October 4, 2016).

See McNeill, D., “Pro-Nuclear Professors Accused of Singing Industry’s Tune in Japan,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 24, 2011.

Ito, M., (2012) Terebi Wa Genpatsu Jiko Dou Tsutaetanoka? (How Did Television Cover the Nuclear Accident?), Tokyo: Heibonsha.

By that time a steady stream of foreign and freelance reporters had been to see the town (AFP was the first to arrive, on March 18th).

Japanese reporters for the big media have little to gain from breaking ranks during major news stories such as Fukushima because they form cartel-like arrangements to prevent rival scoops. In particularly dangerous situations, managers of TV networks and newspapers enter agreements (known as “hodo kyotei”) in effect to collectively keep their reporters out of harm’s way. The volcanic eruption of Mt. Unzen in 1991 and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, both of which led to fatalities among Japanese journalists, solidified these agreements—one reason why so few Japanese reporters from major media could be seen during the Iraq War, or in conflict zones such as Burma, Thailand or Afghanistan. There, freelancers did much of the heavy lifting. Cf. the Vietnam War where Honda Katsuichi reported extensively on the ground for the Asahi.

Personal interview with Kimura Hideaki, journalist with the Asahi Shimbun, May 6, 2015. Kimura was one of the disciplined journalists.

Kaido Yuichi, Kamata Satoshi & Hanada Tatsuro: “Crisis of Asahi and Japanese Journalism”, press conference at The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan, Dec. 16, 2014. Available online here.

“Scholars adamant that Yoshida memoirs had no influence in US,” Asia Policy Point, Sept. 25, 2014. Available online. (Accessed May 2, 2015)

See David McNeill and Justin McCurry, “Sink the Asahi! The ‘Comfort Women’ Controversy and the Neo-nationalist Attack”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 5, No. 1, February 2, 2015. (May 2, 2015)

See McNeill, D., “LDP vs. FCCJ – Behind the Barricades,” No.1 Shimbun, December 2014. Available online. (March. 31, 2016)

2016, Watanabe Tsuneo, editor-in-chief of the Yomiuri Shimbun, hosted an evening dinner with Prime Minister Abe and some of Japan’s top media executives at the company’s headquarters in central Tokyo. The companies represented included the Mainichi, Sankei, Asahi and Nikkei newspapers, along with the nation’s biggest broadcaster, NHK. Writing in the Asahi Shimbun a few days later, journalist Ikegami Akira asked the obvious questions: Who pays when the country’s leader eats with the head of its most-read newspaper? “Does the Yomiuri owe Abe something? Enough to invite him for a meal?…Did Abe meet with Watanabe because he wanted the Yomiuri to understand his views? Or did Watanabe give advice to Abe?” See: 池上彰, “安倍氏は誰と食事した?“朝日新聞, Jan 29, 2016. (Last accessed on March 21, 2016)

See Alexis Dudden and K. Mizoguchi, Abe’s Violent Denial: Japan’s Prime Minister and the ‘Comfort Women,’ Asia-Pacific Journal.

Profile of four appointees: Hyakuta Naoki, Hasegawa Michiko, Honda Katsuhiko, Momii Katsuto. Hyakuta rejects charges that Japan committed war crimes.

The original MOFA document “On the Issue of Comfort Women,” posted in 1993 at a time when the government reached an understanding with the Republic of Korea, notes: With regard to the supervision of the comfort women, the then Japanese military imposed such measures as mandatory use of contraceptives as a part of the comfort station regulations and regular check-ups of comfort women for venereal and other diseases by military doctors, for the purpose of hygienic control of the comfort women and the comfort stations. Some stations controlled the comfort women by restricting their leave time as well as the destinations they could go to during the leave time under the comfort station regulations. It is evident, at any rate, that, in the war areas, these women were forced to move with the military under constant military control and that they were deprived of their freedom and had to endure misery. Available as of Oct. 6th, 2016.

See Fackler, M., “Effort by Japan to Stifle News Media is Working,” New York Times, April 26, 2015. Available online here (last accessed, October 20, 2016).

Novelist Hyakuta attacks Okinawan media at LDP’s meeting; “The two newspapers of Okinawa should be shut down,” Ryukyu Shimpo, June 26, 2015. Available online here (last accessed October 20, 2016).

For example, see Human Rights Watch, “Malaysia: Crackdown on Free Speech Intensifies,” (Oct. 13, 2016).

See, The Japan Times, “Sankei journalist Tatsuya Kato acquitted of defaming South Korean leader,” Dec. 17, 2015. (Last accessed October 11, 2016).