|

Anders Breivik at his trial |

On July 22, 2011, Anders Behring Breivik committed one of the most devastating acts of mass murder by an individual in history. Over the course of one day, he killed 77 people in and around Oslo, Norway, through a combination of a car bomb and shootings. The latter took place on the island of Utøya, where 69 people died, most of them teenagers attending an event sponsored by the Workers’ Youth League. During his subsequent trial, Breivik remained outwardly unemotional as he clearly recounted the events of the day, including the dozens of methodical execution-style shootings on the island. His calmness both on the day of the murders and during the trial, shocked many observers. It was also an important factor in an attempt to declare Breivik insane, a move that he successfully resisted. Breivik himself addressed this subject at some length, crediting his supposed ability to suppress anxiety and the fear of death through concentrated practice of what he called “bushido meditation.” He claimed to have begun this practice in 2006 to “de-emotionalize” himself in preparation for a suicide attack.1 According to Breivik, his meditation was based on a combination of “Christian prayer” and the “bushido warrior codex.”2 Bushido, or “the way of the warrior,” is often portrayed as an ancient moral code followed by the Japanese samurai, although the historical evidence shows that it is largely a twentieth-century construct.3

The extent to which the methodical nature of Breivik’s terror attack could be ascribed to his meditation techniques, “bushido” or otherwise, has been called into question by those who see it as another manifestation of serious mental disturbance. On the other hand, Breivik’s statements regarding “bushido meditation” have parallels with the “Warrior Mind Training” program implemented by the US military during the Iraq War. This program claims to have its roots in “the ancient samurai code of self-discipline,” and is described as a meditation method for dealing with a host of mental issues related to combat.4 Both Anders Breivik and Warrior Mind Training reflect a persistent popular perception of the samurai as fighting machines who were able to suppress any fear of death through the practice of meditation techniques based in Zen Buddhism. Zen has also been linked with the Special Attack Forces (or “Kamikaze”) of the Second World War, who supposedly used meditation methods ascribed to Zen to prepare for their suicide missions.5 This view of Zen as a tool for military use is found in many works on Japanese history and culture, which tend to accept the supposedly ancient relationship between Zen and the samurai.

|

Suzuki Daisetsu |

The relationship between the samurai and Zen Buddhism is often traced back to the thirteenth century, which saw both a rise of warrior power and the increased introduction of Zen teachings from China. The affinity of warriors for Zen is generally explained by their ability to identify with Zen teachings and incorporate them into their lives. As Winston L. King writes of Zen, “from the beginning of Zen’s ‘new’ presence, its meditation and discipline commended themselves to the samurai, of both high and low rank.”6 The modern Zen popularizer Suzuki Daisetsu (D.T. Suzuki; 1870-1966) was one of the best-known promoters of theoretical connections between Zen and Japan’s warrior class. In his best-selling Zen and Japanese Culture, Suzuki claimed that Zen was “intimately related from the beginning of its history to the life of the samurai…” and “…activate(d)…the fighting spirit of the Japanese warrior.”7 The martial arts are often portrayed as an important point of intersection between Zen and the samurai, epitomized through a number of popular works. The most influential text linking Zen and the martial arts is Eugen Herrigel’s (1884-1955) orientalist 1948 book Zen in der Kunst des Bogenschiessens (Zen in the Art of Archery).8 Herrigel’s contentions rested largely on a personal fascination with mysticism and Zen, combined with confusion arising from a serious language barrier between himself and his archery instructor, Awa Kenzō (1880-1939).9 Through the influence of these and other modern interpreters, the martial arts have come to be seen as a window through which Zen and the “samurai spirit” are accessible to millions of people around the world today.

This article will show, however, that the relationship between Zen, samurai, and the martial arts is neither as close, nor as ancient, as it is widely believed to be. In fact, the accepted connections between the three are largely products of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Japanese thinkers in an era of rapid change sought answers and legitimacy in ancient and noble tradition. To this end, this article first considers the historical evidence to question the supposed close connection between Zen and the samurai, as well as Zen and the martial arts. It then provides an overview of the development of bushido in the late Meiji period (1868-1912), which completely revised popular understandings of the samurai. The article then considers the activities of promoters of martial arts and Zen Buddhism in the development of bushido, as they sought to tie their causes to the burgeoning new ideology. Finally, this article looks at the ways in which the Zen-samurai connection became established in mainstream understandings of Japanese history and culture in the decades leading up to 1945, and how this view continued to be accepted largely without question in the postwar period.

Historical backgrounds

The popular view that Japanese warriors have long had an affinity for Zen is not entirely incorrect, as Zen institutions did have several powerful patrons in the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1336-1573) periods. On the other hand, recent scholarship indicates that Zen’s popularity among the elite was most often motivated by practical considerations rather than doctrine. Martin Colcutt argues that Zen teachings were too difficult for many lower-ranking warriors, “most of whom continued to find a less demanding, but equally satisfying, religious experience in the simpler Buddhist teachings of Shinran, Nichiren, or Ippen.”10 Colcutt further argues that even at its peak in the late fourteenth century, Zen could be called “the religion of the samurai” merely because most of its followers were warriors, but this did not mean that most warriors followed Zen, let alone reach a high level of practice.11 As other scholars have demonstrated, the vast majority of warriors followed other schools of Buddhism, including both established and new orders, with more accessible teachings.12

Among elite military families, patronage of Zen was based on political, economic, and cultural factors that were largely unrelated to doctrine. On the political front, Zen presented a non-threatening alternative to the powerful Shingon and Tendai Buddhist institutions that dominated Kyoto and were closely allied to the imperial court.13 Economically, trade with China was an important source of revenue for early medieval rulers, and Zen monks’ knowledge of Chinese language and culture, combined with their administrative abilities, made them a natural choice as ambassadors to the continent. As Zen institutions grew, the frequent sale of high temple offices became increasingly lucrative, eventually bringing even greater income than trade with the continent.14 With regard to the cultural importance of Zen to elites, Zen temples conducted diplomacy with Song (960-1279) and Yuan China (1271-1368), which were the primary sources of artistic and cultural innovations in this period, including tea ceremony, monochromatic painting, calligraphy, poetry, architecture, garden design, and printing.15

Political, economic, and cultural considerations were the primary factors behind the official promotion of Zen institutions by the Kamakura and Muromachi shogunates, although there were a few military and court leaders who attempted to delve more deeply into Zen practice. The shogun Hōjō Tokimune (1251-1284) is reported to have been a devoted student of Zen, studying under the Chinese monk Wuxue Zuyuan (1226–1286). An anecdote related by Colcutt provides a glimpse into the shogun’s practice, including some of the difficulties experienced by his teacher: “Discussions on Zen (zazen) were conducted through an interpreter. When the master wished to strike his disciple for incomprehension or to encourage greater efforts, the blows fell on the interpreter.”16 The major Zen temples consolidated their positions as wealthy and powerful administrative institutions, but as the medieval period went on, there was a serious decline in doctrinal content. By the late fifteenth century “little or no Zen of any variety was being taught in the Gozan [major Rinzai institutions].”17 The situation was similar in other Zen schools. These underwent a major dilution of doctrine through the increased displacement of Zen study by esoteric elements and formulaic approaches that made teachings more accessible.18

|

Zen in the Art of Archery |

The doctrinal connection between the Zen schools and Japanese warriors before the seventeenth century was certainly superficial, and even after this time, there is little evidence of exceptional samurai interest in Zen doctrine. In contrast, a number of scholars argue that samurai engaged with Zen practice rather than doctrine, and the martial arts are often invoked as supposedly providing such a connection: “The ethos of modern martial arts is derived from the Japanese marriage of the samurai code to Zen in Kamakura times,” when the “samurai practiced martial arts as a path toward awakening.”19 Heinrich Dumoulin’s seminal History of Zen takes a typically vague approach, reflecting the lack of evidence linking Zen and the martial arts. On the one hand, Dumoulin speculates that “Long before the introduction of Zen meditation, Japanese infantry-archers were probably acquainted with Zen-like—or better, Yoga-like—practices such as breath control.”20 On the other hand, Dumoulin cites Herrigel’s problematic account as evidence for a Zen-archery connection, claiming that Herrigel’s instructor Awa Kenzō was “full of the spirit of Zen,” when Awa himself denied having any connection with Zen.21 At the same time, Dumoulin concedes that the evidence for a strong link between Zen and archery is circumstantial: “Like all aspects of Japan’s cultural life during the middle ages, the art of archery also came under the formative influence of Zen Buddhism. Among the many famous master archers of that period, not a few had had Zen experience. They did not, however, form any kind of association.” Furthermore, “The different archery groups in Japan have maintained their independence from the Zen school.”22

While many promoters of the Zen-samurai connection focus on the Kamakura period, others situate the relationship much later in the Tokugawa period (1603-1868): “The application of Zen theory and practice to the training of martial skill and technique, and the investing of the warrior life with spiritual values, are really Tokugawa phenomena.”23 As evidence for this latter claim, modern Zen popularizers often cite the interest in swordsmanship displayed by a few Zen figures during the early seventeenth century. However, this does not mean that a significant number of Zen practitioners were also swordsmen, nor does it mean that a majority of the innumerable fencing schools had any Zen connections. As Cameron Hurst writes, “We have to be very careful with the idea of combining Zen and swordsmanship or asserting that ‘swordsmanship and Zen are one’ (kenzen ichinyo). There is no necessary connection between the two, and few warriors were active Zen practitioners.”24 Dumoulin also addresses this subject, writing that “During the Edo period, the art of swordsmanship—like the independently popular art of archery—was inspired just as much, if not more, by the prevalent teachings of Confucianism.” He continues: “it is clear that the military arts of archery and swordsmanship do not belong essentially to the world of Zen, despite certain close relationships. Both arts maintained an independent identity of their own.”25 Dumoulin’s claims in this regard are based on the popularly accepted connections between Zen and the martial arts, rather than historical evidence.

The ideal of the Zen swordsman is epitomized by the writer Yoshikawa Eiji’s (1892-1962) influential, and largely fictional, portrayal of Miyamoto Musashi (1584?-1645) in his best-selling novels Miyamoto Musashi, first published between 1935 and 1939. Relatively little is known of the historical Musashi, and Yoshikawa fleshed out his narrative by adding many details and anecdotes. One of these involved having Musashi study under the Rinzai Zen master Takuan Sōhō (1573-1645), although there is no evidence that the two men ever met.26 Here, Yoshikawa was inspired by modern promoters of the Zen-samurai connection, and especially the ideas of his close friend, the nationalist Yasuoka Masahiro (1898–1983).27 As Peter Haskel implies, Takuan would have to wait until the modern period to have his greatest influence, as his writings were first picked up by bushidō ideologists in the late imperial period and then revived by businessmen—the so-called “economic soldiers”—in the 1970s and 80s.28

With regard to the historical Takuan, while he had no discernible connection with Musashi, and was not a skilled swordsman himself, he did provide guidance to the fencing instructor Yagyū Munenori (1571-1646).29 In his writings to Yagyū, Takuan explained the advantages of Zen training to swordsmen, stating that the concepts of “no-mind” and “immovable wisdom” applied to all activities, including fencing, but this was only one of his interests.30 Takuan was not exclusively interested in martial matters, and his writings were certainly not only addressed to warriors. William Bodiford summarizes the influence of Takuan’s Record of Immovable Wisdom (Fudōchi shinmyōroku), which was finally published in 1779, as follows: “…Takuan’s instructions have been included in innumerable anthologies addressed not only to martial art devotees but to general audiences as well, and thus they have helped promote the popular perception that Zen is an intrinsic element of martial art training. It would perhaps be more accurate to say that success in the martial arts demands mental discipline, a topic about which Zen monks (among others) have much to say.”31

A similar situation can be seen in the case of Suzuki Shōsan (1579-1655), a samurai who experienced various battles before becoming a monk. Suzuki is often cited by later writers attempting to link Zen and the warrior class, especially as he wrote precepts specifically for samurai and had actual military experience. However, the image of Suzuki’s teachings as “warrior Zen” was created through careful selection of his writings, which span half a century and vary widely. Over his lifetime, Suzuki included elements of Daoism, Confucianism, Pure Land Buddhism, and Shinto in his teachings, and his attitude towards death did not always reflect the stoic detachment later attributed to samurai Zen. While some of his texts speak of eliminating the self and drawing energy from death, elsewhere Suzuki wrote of his own fears of death and argued against killing. “What I teach is Buddhism for cowards,” Suzuki wrote, later adding that “If it was up to me I’d say I practice just because I hate death….Everybody loves Buddhism. I know nothing about Buddhism. All I work at is not being subject to death…” Of his own abilities, Suzuki stated that “The only thing I have over others is the degree to which I detest death. That’s what’s made me practice with the warrior’s glare. Really, it’s because of my very cowardice that I’ve made it this far.”32 Suzuki’s precepts for samurai should further be seen in the context and goal of his best-known work, Right Action for All (Banmin tokuyō), which addressed all classes and sought to promote his own interpretation of Buddhism as the correct faith.33 Like Takuan, Suzuki desired to demonstrate that his teachings could be applied to all activities and classes, and warriors were merely one group that he felt could benefit from them.

A third Tokugawa-period Zen figure often cited by proponents of the Zen-samurai connection is Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1768), an influential figure in the Rinzai school.34 Hakuin believed that his teachings could be useful to all classes, and also discussed specific ways in which Zen practice could be of use to samurai. However, this should be seen in the context of his desire to spread Rinzai teachings, rather than as evidence of any exceptional interest in the samurai, who Hakuin described elsewhere as “useless.”35 Hakuin echoed the thoughts of many of his contemporaries when he wrote of the “timid, negligent, careless warriors of these degenerate days,” who had declined from a long-past ideal. “They scream pretentiously that they are endowed at birth with a substantial amount of strength and that there is no need to depend upon being rescued by another’s power, yet when an emergency arises they are the first to run and hide and to besmirch and debase the fame of their warrior ancestors.”36 Hakuin’s harsh criticisms of his samurai contemporaries have generally been left out of modern works seeking to place him in a “samurai Zen” tradition.

Relatively few Zen figures showed an interest in the martial arts, and their attitudes did not necessarily align with the interpretations put forth by modern promoters of “samurai Zen.” On the other hand, like samurai in general, martial arts practitioners in the Tokugawa period were largely ambivalent towards Zen.37 Although many fencing schools incorporated spiritual elements, these were typically an eclectic mix of Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, and folk religion specific to the individual teacher.38 In his detailed case study of the Kashima-Shinryū school of martial arts, Karl Friday has argued that it was “compatible with almost any religious affiliation or lack thereof,” and various generations of masters drew upon a wide variety of different religious and philosophical traditions to construct their own spiritual frameworks.39 This applied to many different schools of martial arts in Japan. Alexander Bennett describes even early schools of swordsmanship as resembling “pseudo-religious cults,” a condition that became more established during the peace of the Tokugawa period.40 Spiritual elements, especially those borrowed from esoteric religious traditions, were important marketing tools for martial arts schools, as they promised prospective students access to unique and secret knowledge unavailable to outsiders. Later, around the turn of the twentieth century, promoters of Zen took advantage of this ambiguity, and portrayed Zen teachings as having been the dominant force in the typically opaque mixture of spiritual traditions that coursed through the martial arts schools of the Tokugawa period.

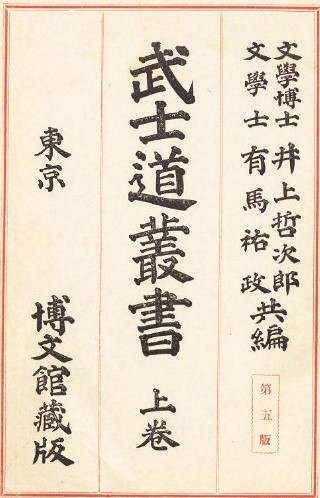

From the various perspectives of samurai, Zen figures, and martial artists in the Tokugawa period, the evidence does not support a clear and significant connection between Zen and the martial arts or any “way of the samurai.” Conversely, the texts most frequently cited as sources of bushido in modern Japan contradict many of the assertions made by promoters of Zen. Tokyo Imperial University philosophy professor Inoue Tetsujirō’s (1856-1944) 1905 collection of Tokugawa-era documents, The Bushido Library (Bushidō sōsho), established the core of the bushido canon until at least 1945, and his selection continues to have a strong influence on scholarship today. When Inoue was selecting texts for this collection, promoters of Zen were still in the early stages of engagement with bushido discourse. The texts chosen by Inoue were quite diverse in their interpretations of the duties and obligations of samurai, but were almost all in agreement in their rejection of Buddhism, reflecting the dominant sentiment among Tokugawa samurai.41 The Bushido Library includes writings by Kumazawa Banzan (1619-1691), Yamaga Sokō (1622-1685), Yamazaki Ansai (1619-1682), Muro Kyūsō (1658-1734), and Kaibara Ekiken (1630-1714), all of whom are frequently cited by modern bushido theorists.42

|

Inoue Tetsujiro |

Bushido Library (Bushido sosho), 1905 |

Yamaga Sokō, the most important exponent of samurai ethics in the eyes of most modern bushido theorists, dismissed Zen as useless, a view shared by his influential later student, Yoshida Shōin (1830-1859).43 For his part, Kumazawa Banzan criticized the Pure Land, Nichiren, Shingon, and Tendai sects, and stated that Zen was the worst of them all in the extent to which it deluded its followers.44 Criticism of Zen by samurai writers continued to the very end of the Tokugawa period, with the prominent reformer Yokoi Shōnan (1809-1869) deriding it as an “empty” teaching.45 Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659-1719)—the source of the famously death-focused Hagakure text—claimed to have retired to a Zen temple as a symbolic death after being prevented from committing ritual suicide upon his lord’s passing. This choice seems to have been made for practical rather than religious reasons, however, and Hagakure cites a Zen priest as stating that Buddhism is for old men rather than samurai.46 Hagakure contains little that could be regarded as specifically Zen in origin. Instead, in keeping with similar tracts at the time, it most frequently mentions the “gods and Buddhas” and “family gods (ujigami)” of a more general folk religion.47 Yamamoto’s stated desire was not to attain enlightenment, but to be reincarnated as a retainer as often as possible in order to better serve his lord’s descendants.48

Buddhism, samurai, and the origins of bushido in Meiji

The establishment of State Shinto in the early Meiji period presented a serious challenge to all schools of Buddhism. This new institution was intended to formalize and universalize emperor-worship in the new Japanese state, while simultaneously acting as a tool for the suppression of foreign religions. Although Christianity seems the most obvious target in this regard, Buddhism was also fiercely attacked as a “foreign religion” by state-supported Shinto nationalists. Buddhism arguably suffered the greatest shock in this period, as temples suddenly went from being the official registries of all Japanese households during the Tokugawa period to being persecuted, disowned of property, and even disbanded. Government policies restricting Buddhism met with widespread protest, and the military was required to quell uprisings in some parts of Japan. The state soon realized that the harshest policies were not tenable, and attempted limited reconciliation and incorporation of Buddhism into the State Shinto structure, thereby preventing major additional outbreaks of violence. Buddhism remained distinctly second-class relative to Shinto in the official state ideology until 1945, but it continued to dominate popular religious life in many areas.

Following the protests of early Meiji, Buddhists met the challenges in different ways. James Ketelaar has examined the movements to create a “modern Buddhism” through the reform of sectarian academies into modern institutions of broader instruction, and to develop Japanese Buddhism into something that would be recognized internationally as a universal religion.49 Another response, especially from the 1890s onward, was one of almost aggressive attempts to conform to the new order. This included proving to the government that Buddhism could play a practical role within the emperor-focused order. Important activities included the United Movement for Revering the Emperor and Revering the Buddha (Sonnō hōbutsu daidōdan), formed in 1889 in order to “preserve the prosperity of the imperial household and increase the power of Buddhism,” and to help Buddhists to secure government positions.50 To regain national acceptance, Buddhists focused on the long history of their religion in Japan and the supposedly inseparable roots of Buddhism and the Japanese character. The first discussion of Buddhism’s links with bushido in the 1890s were part of the response to nationalistic challenges that accompanied modernity.

The first decades of Meiji posed great challenges to Japanese Buddhism, and they were no less tumultuous for the samurai. Sonoda Hidehiro has described the period from 1840-1880 as one of “decline of the warrior class,” including the last decades of the Tokugawa period in his examination.51 Arguments concerning intangible changes such as a loss of spirit or general degeneration of the samurai were nostalgic for an ideal that never existed in that form, but they are one of the most common themes in late Tokugawa writings. The feeling of decline and nostalgia is clear in personal accounts by nineteenth century samurai, such as Katsu Kokichi (1802-1850) and Buyō Inshi (dates unknown).52 Influential figures such as Yoshida Shōin and Yokoi Shōnan lamented what they saw as the poor state of the samurai in the 1850s and 1860s. In the early 1870s, William Elliot Griffis wrote that “…the majority [of samurai] spent their life in eating, smoking, and lounging in brothels and teahouses, or led a wild life of crime in one of the great cities. When too deeply in debt, or having committed a crime, they left their homes and the service of their masters, and roamed at large.”53 Griffis’ description of the recent past may have exaggerated the extent of samurai delinquency, but it reflected popular contemporary views.

The samurai, who had been made effectively redundant by the formation of a new conscripted imperial army based on European models, gradually had their hereditary stipends and privileges stripped away by a series of decrees in the years after 1868. Having lost both the ideological and practical support for their traditional exalted position in society, many struggled to adapt to the new order, resulting in a number of violent uprisings. These culminated with the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion in Southwestern Japan, which involved tens of thousands of disgruntled former samurai, and was only suppressed by the government with great loss of life on both sides. The conflict has been portrayed as a showdown between the Imperial Japanese Army, consisting mainly of conscripted commoners, and their “traditional oppressors, the samurai.”54 While the sides were not necessarily so clearly delineated, this portrayal reflects popular views at the time. Most Japanese had a negative opinion of the samurai throughout the 1870s and 1880s, combining resentment of the ruling clique of former samurai from the domains of Satsuma and Chōshū with disdain for those who had fallen on hard times following the loss of their traditional privileges. There were popular tales of samurai incompetence, as well as many satirical poems about their decline, portraying them doing manual labor and unable to pursue their former leisure activities.55 There was also a smattering of appeals for compassion for the downtrodden former samurai due to their “past accomplishments.”56 This poor image of the samurai contributed to the negative popular image of the recent past. As Carol Gluck has argued, although nostalgia towards the Tokugawa period began to increase in the 1890s, it “began its Meiji career as the bygone old order, which excited little favorable comment or nostalgia except perhaps among former shogunal retainers and other chronological exiles…”57

|

Ozaki Yukio |

The notion that a samurai-based ethic could benefit the new Japan would have seemed alien to most Japanese until the 1890s. The first major step towards a positive reevaluation of the samurai came through the work of the journalist Ozaki Yukio (1858-1954). Ozaki was banned from Tokyo for three years due to his political activism in 1888, and he used this opportunity to travel to the United States and Europe. Ozaki was most impressed with England, and was especially taken by the idealized Victorian discourse on chivalry and gentlemanship that he recognized from reading English books in his youth. He was convinced that English conceptions of the gentleman provided the moral foundation of the British Empire, as this seemingly noble ethic meant that Englishmen enjoyed great trust and respect abroad. In a dispatch sent to a major Japanese newspaper in 1888, Ozaki explained his views of English gentlemen, while lamenting the supposed moral failings of their Japanese counterparts. According to Ozaki, Japan was doomed to failure if it did not adopt an ethic comparable to English gentlemanship.58 In a subsequent article in 1891, having returned to Japan, Ozaki cited the popular Victorian argument that English gentlemanship was rooted in medieval chivalry. According to Ozaki, Japan did not necessarily need to import a foreign ethic, as the country had its own “feudal knighthood” that could serve as a model. Ozaki proposed reviving the ethical ideals of the former samurai, which had long been in decline. Here, he proposed a new code that he called the “way of the samurai,” or “bushidō,” which would make Japanese merchants become “strictly faithful, strictly honor agreements, and avoid coarse and vulgar speech.” If such an ethic were not adopted, Ozaki warned, Japan was certain to fail.59

Ozaki’s ideas resonated with many Japanese in a period of disillusionment with both the historical cultural model of China and the new models of the West. The former was due to the precarious state of Chinese rulership and increasingly hostile relations with Japan, while the process of negotiating the unequal treaties with the Western powers negatively impacted public opinion. The 1890s saw many new and repurposed concepts popularized as ancient “native” ethics, and bushido was ideally suited to this purpose. At the same time, Ozaki’s examination of English chivalry and gentlemanship legitimized the use of the samurai as a source for a new morality. The popularity of an ethic based on knighthood in the world’s most powerful country emboldened Japanese thinkers to look towards the former samurai, even if they generally agreed that the samurai spirit had degenerated almost irreparably over the preceding decades. A number of other writings on bushido appeared in the early 1890s, generally referring to Ozaki or responding to his arguments.60 Bushido was given a tremendous boost with the euphoria of victory in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, setting off a “bushido boom” that peaked around the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Although bushido discourse was inspired by Ozaki’s articles, he did not agree with the chauvinism that marked many later interpretations, and contributed his last significant article on the subject in 1898. Instead, the militaristic and extremely nationalistic bushido promoted by Inoue Tetsujirō became established as the “imperial bushido” interpretation around the time of the Russo-Japanese War, and dominated bushido discourse in Japan until 1945.

Linking Zen, bushido, and the martial arts

The firm establishment of bushido as a commonly accepted and even fashionable concept during and after the Russo-Japanese War led to its adoption by a broad spectrum of institutions and social groups during the decade 1905-1914. By claiming a link to bushido, individuals and organizations promoted sports, religious orders, and other causes in a patriotic manner, providing relatively recent innovations with historical legitimacy apparently stretching back centuries or even millennia. Promoters of the martial arts were among the most active participants in the nationalistic bushido discourse that emerged after 1895. The first dedicated periodical on the subject, titled Bushidō,was published by the Great Japan Martial Arts Lecture Society in 1898.61 While historians have traditionally seen the early Meiji period as a nadir of the martial arts, Denis Gainty has recently demonstrated that martial arts competitions continued to be popular throughout the period.62 As Gainty further shows, however, there was great scope for the organization and systematic popularization of the martial arts, manifested by the Great Japan Martial Virtue Association, which was founded in 1895 and reached one million members by the end of its first decade.63 The martial arts rode the wave of nationalistic fervor following victory over China to help overcome considerable challenges from baseball and other sports, as well as intense competition among schools and styles. As a result, promoters of martial arts including kendo, judo, jujutsu, and sumo, to name but a few, were highly active in the fabrication of supposed historical links to bushido and an idealized Japanese martial tradition.64

Like martial artists, Buddhists came to use bushido to establish a connection with patriotically sound “native” traditions. Meiji Buddhists often had their patriotism and devotion to the national cause called into question, and many came to rely on bushido to prove their “Japaneseness.” Vague references to Buddhism were part of bushido discourse from the Sino-Japanese War onward, as promoters of bushido turned away from Western models and looked to Japanese culture for points of reference. In 1894, Uemura Masahisa (1858-1925), a prominent Protestant and early bushido theorist, argued for a connection between bushido and Buddhism, writing: “[t]o understand chivalry, you must know Christianity. To understand bushido, you must know Buddhism and Confucianism.” This view was echoed in 1899 by Mikami Reiji (dates unknown). In Japan’s Bushido, the first book dedicated to bushido, Mikami highlighted Buddhism as a source of bushido, along with Confucianism, Shinto, and the Heart-and-Mind School (shingaku).65 The following year, the Western-educated Quaker Nitobe Inazō listed Zen as one of the primary “sources of bushido” in his international bestseller Bushido: The Soul of Japan.66 Even Inoue Tetsujirō acknowledged Buddhism in his first text on the subject in 1901, following Uemura, Mikami, and Nitobe in contending that “bushido in its fully finished form is the product of a balanced fusion of the three teachings of Shinto, Confucianism, and Buddhism.”67

While these generic mentions of Buddhism in more general texts on bushido were common, promoters of Buddhism who sought to use bushido for their own purposes could not simply use the “imperial” bushido interpretation put forth by Inoue Tetsujirō and other Shinto nationalists. Instead, writers focusing on the connections between Buddhism and bushido were compelled to put forth new interpretations that downplayed Shinto, Confucianism, and other elements commonly linked with bushido. Furthermore, the early bushido promoted by Ozaki Yukio, which relied on Western models, was similarly unsuited to Buddhist aims. Through careful selection and appropriation of elements of bushido discourse, however, Japanese Buddhists were able to construct their own bushido theories and to benefit from the broad popular appeal of the ideology.

By the early 1900s, Buddhism had established itself in the popular mind as one of the thought systems that broadly contributed to bushido. In the second decade of the Meiji bushido boom—from 1905 to 1914—Buddhist engagement with bushido discourse increased dramatically along with popular interest. Promoters of the Zen schools expended by far the greatest efforts to link their teachings to bushido, and current popular perceptions linking Zen with the samurai are the result of this activity. In spite of a dearth of historical evidence, the supposedly close relationship between Zen and bushido became accepted due to the support it had among some of the most influential figures in broader bushido discourse. This can be seen in one of the most extensive early treatments of the subject, the 1907 book Zen and Bushido. The author of this work, Akiyama Goan, had worked closely with Inoue Tetsujirō in compiling the 1905 Collection of Bushido Theories by Prominent Modern Thinkers (Gendai taika bushidō sōron), which provided an extensive selection of recent commentaries on bushido.68

Akiyama opened his Zen and Bushido with the revealing observation that although the relationship between Zen and bushido was a very close one, few people were aware of the background of this connection.69 Akiyama’s arguments were based on the historical circumstance that the introduction and spread of Zen Buddhism in Japan in the Kamakura period coincided with the establishment and growth of warrior power. During this period, Akiyama argued, warriors developed a strong connection with Zen Buddhism. This became even more pronounced during the turmoil and constant mortal danger in the age of warring states, when the “affinity between Zen and bushido became ever closer.”70 Akiyama countered the accepted historical view that warriors were interested in Zen institutions for practical secular reasons, instead insisting that Zen teachings were at the heart of warrior interest. Akiyama also dismissed the idea that other, much larger Buddhist schools such as the Pure Land or Tendai schools could have had a significant influence on bushido during the Kamakura period. According to Akiyama, these schools were nothing more than mere “superstition” and “reasoning,” respectively, and “absolutely did not have the power to cultivate and nurture Japan’s unique ethic, i.e. the bushido spirit.”71 Instead, he wrote, Zen was fundamental to the effectiveness of bushido, and “just as Kamakura Zen worked with Kamakura bushido, we need to strive to combine Meiji Zen with Meiji bushido.”72 The importance and historical legitimacy of bushido were largely unquestioned in Japan following the Russo-Japanese War, and the ideology provided an ideal vehicle for Akiyama and others to appeal for Zen Buddhism’s nationalistic credentials.

|

General Nogi Maresuke |

The effectiveness of these endeavors was increased by General Nogi Maresuke’s (1849-1912) connection with Zen Buddhism. Nogi was introduced to the Rinzai Zen master Nakahara Nantembō (1839-1925) in 1887, and studied his teachings with such dedication that Nakahara attested to Nogi’s enlightenment and named him as a successor.73 Nogi was one of the most prominent military figures of the Meiji period. He led the capture of Port Arthur in the Sino-Japanese War, and lost both of his sons in battle for the same city against Russia in 1904. By the time of the Russo-Japanese War, Nogi was popularly known as the “flower of bushido.”74 Nogi’s combined interest in Zen and bushido reflect the revisionism of many bushido theorists at the time. He was a keen student of Inoue Tetsujirō’s bushido theories, and accordingly described the seventeenth-century strategist Yamaga Sokō as the “sage of bushido” and single most important exponent of the warrior ethic. Like Inoue, Nogi placed Yamaga’s later interpreter Yoshida Shōin a close second. In line with the selective use of earlier texts practiced by many of his contemporaries, Nogi tended to overlook Yamaga and Yoshida’s harsh criticism of Zen.

Another promoter of Zen who frequently invoked bushido was Suzuki Daisetsu. Suzuki’s writings on bushido and Zen around the turn of the century are not extensive, but are significant in light of his later activities. Suzuki became by far the most significant promoter of “samurai Zen,” especially for its dissemination outside of Japan. In this regard, his writings from as early as 1895 are revealing for the later development of his bushido thought. On the occasion of the Sino-Japanese War, Suzuki wrote that in the face of the challenge from China, “In the name of religion, our country refuses to submit itself to this. For this reason, unavoidably we have taken up arms. … This is a religious action.”75 Responding to the Russo-Japanese War in 1906, Suzuki wrote in the Journal of the Pali Text Society:

The Lebensanschauung of Bushido is no more nor less than that of Zen. The calmness and even joyfulness of heart at the moment of death which is conspicuously observable in the Japanese, the intrepidity which is generally shown by the Japanese soldiers in the face of an overwhelming enemy; and the fairness of play to an opponent, so strongly taught by Bushido—all these come from the spirit of Zen training…”76

In this passage, Suzuki echoed the imperial bushido view of death that had been established through a series of public debates concerning the responsibilities of soldiers in hopeless situations during the Russo-Japanese War.77 Earlier Japanese attitudes toward surrender and becoming a prisoner of war were largely in line with international norms, but Inoue Tetsujirō and other nationalistic hardliners carried the day on this issue. Following the Russo-Japanese War, surrender came to be widely accepted as “un-Japanese” and in violation of supposedly ancient samurai traditions. This ahistorical bushido-based interpretation led to countless tragedies in the 1930s and 1940s.78

The idea that soldiers should dismiss fear of death became one of the primary arguments put forward by promoters of Zen, who claimed that this was a contribution of Zen to the samurai and bushido. The Rinzai master Shaku Sōen (1860-1919) elaborated on this issue in a 1909 book, while other texts arguing for the Zen-bushido connection included Arima Sukemasa’s (1873-1931) 1905 “About Bushido,” Katō Totsudo’s (1870-1939) 1905 Zen Observations, and Yamagata Kōhō’s (1868-1922) 1908 New Bushido.79 The Zen influence on the alleged indifference to death felt by Japanese soldiers was expanded in the 1930s by Zen figures such as the Sōtō master Ishihara Shummyō (1888-1973).80 Zen master Iida Tōin (1863-1937) even saw death as “a way to repay one’s debt to the emperor,” while his colleague Seki Seisetsu (1877-1945) emphasized the “sacred” nature of the war.81

In contrast to Suzuki’s nativist focus on death, his discussion of “fair play” reflects the strong influence of Western—especially British—ideas of chivalry and gentlemanship on certain strands of modern bushido discourse. It is important to note that Suzuki published this article in English, making it useful to include concepts readily recognizable to a foreign audience. Many of Suzuki’s readers would already have been primed through their familiarity with Nitobe Inazō’s Bushido: The Soul of Japan, much of which is Victorian moralism with an attractive Oriental veneer.82 Although foreign observers generally approved of Japan’s conduct during the Russo-Japanese War, it was precisely the perceived lack of a “fair play,” towards both enemies and Japanese troops in subsequent conflicts that became one of the greatest criticisms of the Imperial Japanese Army and the Zen-bushido connection in the 1930s and 1940s.

Suzuki was one of the main promoters of the Zen-bushido connection both within Japan and overseas, but he was far from alone. Nukariya Kaiten (1867-1934) was another influential proponent of samurai Zen to foreign audiences, especially through his popular 1913 book, Religion of the Samurai. Nukariya reaffirmed the close relationship between Zen and the samurai claimed by many of his contemporaries, but his text was also highly revealing in other ways:

“After the Restoration of the Meiji (1867) the popularity of Zen began to wane, and for some thirty years remained in inactivity; but since the Russo-Japanese War its revival has taken place. And now it is looked upon as an ideal faith, both for a nation full of hope and energy, and for a person who has to fight his own way in the strife of life. Bushido, or the code of chivalry, should be observed not only by the soldier in the battle-field, but by every citizen in the struggle for existence.”83

Here, Nukariya concedes that Zen had been unpopular and “inactive” from the 1860s until the early twentieth century. Although he implies that Zen had been popular before this, there is no evidence to support this contention, indeed Zen had been relatively unimportant—especially to samurai—for several centuries by this point. Nukariya’s argument concerning Zen’s trajectory echoes a common trope concerning bushido in late Meiji: that it had declined in popularity since the 1860s but had now been “revived” by the wars with China and Russia. In the case of both Zen and bushido, an essentially new development was given an idealized past from which it had supposedly suffered a temporary decline. Nukariya further drew the connections between Zen and the samurai by highlighting General Nogi as the most recent “incarnation of bushido.” Nogi and his wife, Shizuko, had committed ritual suicide the previous year on the day of the Meiji emperor’s funeral, an act that Nukariya believed would “surely inspire the rising generation with the spirit of the Samurai to give birth to hundreds of Nogis.”84

During and after the Russo-Japanese War, when bushido had become firmly established in the popular consciousness, Buddhists relied on bushido to promote their own faith and causes. Promoters of Zen most openly and effectively embraced the militarism inherent in the warrior ethic, but interest in bushido reached across denominations. This can be seen in a 1905 article by the Buddhist scholar and member of the True Pure Land school, Nanjō Bun’yū (1849-1927), titled “Concerning the Relationship between Bushido and Buddhism.” Nanjō argued that “people commonly say that the basis of Buddhism is mercy, and therefore it not only provides no benefit to bushido, but there is even a danger that it will weaken the warrior spirit.” However, continued Nanjō, this was only a very superficial understanding of Buddhism, and he proceeded to discuss Prince Shōtoku (6th century), imperial loyalist Kusunoki Masashige (1294-1336), and the late Russo-Japanese War hero and “military god” Commander Hirose Takeo (1868-1904) as examples of brave men who derived strength from Buddhism. “Our bushido has received the Buddhism of causality spanning the past, present, and future (sanze’inga), and even if the body dies the spirit continues, so that one will be born as a human for seven lives” in order to reach one’s long-cherished goals of repaying the kindness of the nation (kokuon) and supporting the imperial house.85

The patriotic propaganda and activities on the part of Buddhists paid dividends by the end of Meiji, although the costs were considerable. In addition to aiding in the colonization of Hokkaido and the other northern territories, Buddhist sects sent missionaries and medical workers to the wars with China and Russia. At the same time, they spread morale-boosting information and collected donations and supplies on the home front.86 While these practical activities contributed to Buddhism’s rehabilitation in the eye of the imperial state, the skilled and consistent engagement with bushido practiced by promoters of Zen had arguably the greatest and most lasting effect. Their extensive attempts to tie Zen teachings to the burgeoning bushido discourse around the time of the Russo-Japanese War created a belief that the two had always been linked. Through their efforts, Zen became the “religion of the samurai.” The effectiveness of this approach could be seen in the writings of the literary scholar Tsuda Sōkichi (1873-1961). In a harsh 1901 review of Nitobe Inazō’s Bushido: The Soul of Japan, Tsuda dismissed any meaningful connection between bushido and Buddhism, especially Zen. Tsuda argued that even after its arrival in the Kamakura period, Zen did little more than accentuate existing warrior thought and practice.87 In contrast, in 1917 Tsuda maintained that both samurai and Buddhists rejected the notion that samurai should be involved with Buddhism, but amended this by stating that Zen’s close connection with bushido was an exception to this rule.88 Tsuda’s reconsideration over the period between these two texts reflects the convincing work by promoters of Zen and bushido in the early twentieth century. By the 1920s, many people were convinced of the intricate and ancient relationship between Zen, samurai, bushido, and the martial arts, and this ideological mix became a core element of nationalist thought, as can be seen in the writings of Yasuoka Masahiro and others.89

Conclusions

The notion that Zen had a powerful influence on bushido and the samurai is a construct of the Meiji period, but has shown remarkable resilience. Even after 1945, Zen figures such as Suzuki Daisetsu and Sugawara Gidō (1915-1978) continued to argue for the historicity of the Zen-bushido connection, and this interpretation has remained influential in popular literature and culture in both Japan and abroad up to the present day.90 Suzuki has been subjected to criticism by scholars in recent years, but his influence on popular conceptions of Zen Buddhism remains strong, especially outside of Japan. His works are widely read, and continue to contribute to the notion that Zen formed a sort of spiritual foundation for the samurai in general and bushido in particular. In spite of the widespread rejection of bushido in Japan and abroad immediately after World War II, Suzuki’s works continued to emphasize the importance of the alleged historical connections between bushido and Zen. Partly as a result of his efforts, Zen came to be even more closely identified with the samurai. At the same time, Zen and bushido were detached from problematic associations with the early twentieth century, in spite of the fact that the connection between the two was a product of this very period.

These same dynamics also tied into the development of popular views of Zen’s relationship to the martial arts. The Zen-samurai relationship was the result of conscious efforts on the part of Zen promoters to gain patriotic legitimacy by engaging closely with the burgeoning bushido discourse. In contrast, the relationship between Zen and the martial arts was less straightforward, and developed from a confluence of several factors. One of these was that, aside from Shinto nationalists and state-sponsored proponents of the “imperial” bushido ideology, promoters of Zen and promoters of the martial arts were two of the most active and effective groups tying their interests to bushido. As a result, both Zen and the martial arts were widely seen as closely related to bushido, an impression that was strengthened when direct links between the two were drawn explicitly in popular works by promoters of both, such as Eugen Herrigel. This became especially important following the discrediting of “imperial” bushido in 1945, when the more fantastical elements were stripped from the ideology, leaving behind a vague association between Zen, the samurai, and the martial arts to help revive bushido in the postwar period and carry it on into the twenty-first century.

Notes:

I would like to thank Denis Gainty and Brian Victoria for reading and providing invaluable suggestions on a draft of this article. The responsibility for any shortcomings that remain is, of course, entirely my own.

This article also draws on arguments made in Chapter Four of my book, Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014). I thank Oxford University Press for permission to reproduce excerpts from the section “Bushidō and Buddhism” (pp. 135-140) here.

Bibliography:

Akamatsu, Toshihide. “Muromachi Zen and the Gozan System,” in John W. Hall and Toyoda Takeshi eds. Japan in the Muromachi Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Akiyama Goan, ed. Gendai taika bushidō sōron. Tokyo: Hakubunkan, 1905.

Akiyama Goan. Zen to bushidō. Tokyo: Kōyūkan, 1907.

Anesaki, Masaharu. History of Japanese Religion: With Special Reference to the Social and Moral Life of the Nation. London: Kegan Paul, 1930.

Arima Sukemasa “Bushidō ni tsuite” Gendai taika bushidō sōron. Hakubunkan: 1905, pp. 273-284.

Bein, Steve trans and commentary. Purifying Zen: Watsuji Tetsurō’s Shamon Dōgen. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2011.

Benesch, Oleg. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Bennett, Alexander. Kendo: Culture of the Sword. University of California Press, 2015.

Besserman, Perle and Steger, Manfred. Zen Radicals, Rebels, and Reformers. Wisdom Publications, 2011.

Bodiford, William. “Takuan Sōhō” in William de Bary et al. eds. Sources of Japanese Tradition Volume 2. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 527-528.

Brink, Dean Anthony. “At Wit’s End: Satirical Verse Contra Formative Ideologies in Bakumatsu and Meiji Japan,” Early Modern Japan Spring 2001, pp. 19-46.

Brown, Roger. “Yasuoka Masahiro’s ‘New Discourse on Bushidō Philosophy’: Cultivating Samurai Spirit and Men of Character for Imperial Japan,” Social Science Japan Journal 16:1 (2013), pp. 107-129.

Buyō Inshi, Mark Teeuwen, Kate Wildman Nakai, Fumiko Miyazaki, Anne Walthall, John Breen. Lust, Commerce, and Corruption: An Account of what I have Seen and Heard, by an Edo Samurai. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Calman, Donald. The Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism: A Reinterpretation of the Great Crisis of 1873. London: Routledge, 1992.

Cleary, Thomas. Training the Samurai Mind: A Bushido Sourcebook. Shambhala, 2009.

Colcutt, Martin. Five Mountains: The Rinzai Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Collcutt, Martin. “Religion in the Life of Minamoto Yoritomo and the Early Kamakura Bakufu,” in P.F. Kornicki and I.J. McMullen eds. Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. pp. 90-120

Dumoulin, Heinrich; James W. Heisig and Paul Knitter trans. Zen Buddhism: A History. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1990.

Friday, Karl F. “Bushidō or Bull? A Medieval Historian’s Perspective on the Imperial Army and the Japanese Warrior Tradition” The History Teacher Vol. 27, No. 3 (May, 1994), pp. 339-349

Friday, Karl F. and Seki Humitake. Legacies of the Sword: The Kashima-Shinryu and Samurai Martial Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Fukuhara Kenshichi. Nihon keizai risshihen. Osaka: 1881.

Fukuzawa Yukichi. Meiji jūnen teichū kōron, Yasegaman no setsu. Tokyo: Kōdansha Gakujutsu Bunko, 2004.

Gainty, Denis. Martial Arts and the Body Politic in Meiji Japan. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Gluck, Carol. “The Invention of Edo,” in Stephen Vlastos ed. Mirror of Modernity: Invented Traditions in Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998, pp. 262–284.

Goble, Andrew Edmund. Kenmu: Go-Daigo’s Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Griffis, William Elliot. The Mikado’s Empire. New York: Harper, 1876.

Grossberg, Kenneth Alan. Japan’s Renaissance: The Politics of the Muromachi Age. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Haskel, Peter. Sword of Zen: Master Takuan and His Writings on Immovable Wisdom and the Sword Taie. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2013.

Heine, Steven. “A Critical Survey of Works on Zen since Yampolsky,” Philosophy East and West, 57:4 (Oct. 2007), pp. 577-592.

Heine, Steven. Zen Skin, Zen Marrow: Will the Real Zen Buddhism Please Stand Up? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Hurst, G. Cameron III. Armed Martial Arts of Japan: Swordsmanship and Archery. Yale University Press, 1998.

Hurst, G. Cameron III. “Death, Honor, and Loyality: The Bushidō Ideal” Philosophy East and West Vol. 40, No. 4, Understanding Japanese Values (Oct., 1990), pp. 511-527.

Hurst, G. Cameron. Samurai on Wall Street: Miyamoto Musashi and the Search for Success. Hanover, NH: Universities Field Staff International, 1982.

Ikushima Hajime. Seidan tōron hyakudai. Tokyo: Matsui Chūbei. 1882.

Inoue Tetsujirō. Bushidō. Tokyo: Heiji zasshi sha, 1901.

Inoue Tetsujirō, ed. Bushidō sōsho. Tokyo: Hakubunkan, 1905.

Ives, Christopher. “Ethical Pitfalls in Imperial Zen and Nishida Philosophy: Ichikawa Hakugen’s Critique” in James Heisig and John Maraldo eds. Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School, & the Question of Nationalism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1994, pp. 16-39.

Ives, Christopher. Imperial-Way Zen: Ichikawa Hakugen’s critique and lingering questions for Buddhist ethics. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

Katō Totsudō. Zen kanroku. Tokyo: Ireido, 1905.

Katsu Kokichi, Teruko Craig trans. Musui’s Story: The Autobiography of a Tokugawa Samurai. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1991.

Keenan, John P. “Spontaneity in Western Martial Arts: A Yogācāra Critique of Mushin (No-Mind),” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 16:4 (1989), pp. 285-298.

Ketelaar, James Edward. Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan: Buddhism and its Persecution. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1993.

King, Winston L. Zen and the Way of the Sword: Arming the Samurai Psyche, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1993.

Kumazawa Banzan; McMullen, Ian J. trans. “Buddhism” Sources of Japanese Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 129-130.

McFarlane, Stewart. “Mushin, Morals, and Martial Arts: A Discussion of Keegan’s Yogācāra Critique,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 17:4 (1990), pp. 397-420.

Mikami, Reiji. Nihon bushidō. Tokyo: Kokubunsha, 1899.

Nakamura Yoko. Bushidō – Diskurs. Die Analyse der Diskrepanz zwischen Ideal und Realität im Bushidō-Diskurs aus dem Jahr 1904. Ph.D. Thesis at the University of Vienna, 2008.

Nanjō, Bun’yū. “Bushidō to bukkyō no kankei ni tsuite,” in Akiyama, Goan ed. Gendai taika bushidō sōron. Tokyo: Hakubunkan, 1905, pp. 416-419

Nitobe, Inazo. Bushido: The Soul of Japan. Tokyo: The Student Company, 1905.

Nukariya Kaiten. The Religion of the Samurai: A Study of Zen Philosophy And Discipline in China And Japan. London: Luzac & Co., 1913.

Ozaki, Yukio. “Ōbei man’yū ki,” Ozaki Gakudō zenshū Vol. 3. Tokyo: Kōronsha, 1955, pp. 743-748.

Ozaki, Yukio. Naichi gaikō. Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1893.

Saiki Kazuma, et al. eds. Mikawa monogatari, Hagakure (Nihon shisō taikei Vol. 26). Iwanami Shoten, 1974.

Shaku Sōen. Sentei roku. Tokyo: Kōdōkan, 1909.

Snodgrass, Judith. Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Sonoda Hidehiro. “The Decline of the Japanese Warrior Class, 1840-1880” Japan Review 1 (1990), pp. 73-111

Stone, Jacqueline L. “Chanting the Lotus Sutra Title,” in Richard K. Payne ed. Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1998, pp. 116-166.

Stone, Jacqueline I. Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999.

Suzuki Chikara. Kokumin no shin seishin. Tokyo: Hakubundō, 1893.

Suzuki Daisetz T. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Takagi Yutaka. “The Nichiren Sect,” in Kasahara Kazuo ed. A History of Japanese Religion. Tokyo: Kosei Publishing, 2001, pp. 255-283.

Tanabe Jr., George J. “Kōyasan in the Countryside,” in Richard K. Payne ed. Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1998, pp. 43-54.

Tsuda, Sōkichi. “Bushidō no engen ni tsuite“ Matsushima Eiichi ed. Meiji shi roshū 2. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1976, p. 317.

Tsuda Sōkichi. Inquiry into the Japanese Mind as Mirrored in Literature. Tokyo: JSPS, 1970.

Tucker, Mary Evelyn. Moral and Spiritual Cultivation in Japanese Neo-Confucianism: The Life and Thought of Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714). New York: State University of New York Press, 1989.

Tyler, Royall trans. “Suzuki Shōsan.” in James Heisig et al. ed.,Japanese Philosophy: A Sourcebook. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2011, pp. 109-115.

Tyler, Royall. “Suzuki Shōsan.” In Sources of Japanese Tradition Volume 2, William de Bary et al. ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 522-523.

Varley, Paul and Elison, George. “The Culture of Tea,” in George Elison and Bardell Smith eds. Warlords, Artists, & Commoners: Japan in the Sixteenth Century. The University Press of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1981.

Victoria, Brian Daizen. “A Buddhological Critique of “Soldier-Zen” in Wartime Japan,” in Mark Jurgensmeyer and Michael Jerryson eds. Buddhist Warfare. Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 119-120.

Victoria, Brian Daizen. “A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan: Count Dürckheim and his Sources—D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel,” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 12:3:2 (Jan. 13, 2014).

Victoria, Brian Daizen. “When God(s) and Buddhas Go to War,” in Mark Selden and Alvin Y. So eds. War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004. pp. 91-118.

Uemura, Masahisa. Uemura Masahisa chosakushū Volume 1. Shinkyō Shuppansha, 1966.

Victoria, Brian Daizen. Zen at War. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

Welter, Albert. “Eisai’s Promotion of Zen for the Protection of the Country,” in George J. Tanabe Jr. ed. Religions of Japan in Practice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999, pp. 63-70.

Yamada Shōji. “The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 28:1/2 (2001), pp. 1-30.

Yamada Shōji, Earl Hartman trans. Shots in the Dark: Japan, Zen and the West. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2009.

Yamaga, Sokō. Yamaga Sokō (Nihon shisō taikei Vol. 32). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1970.

Yamagata Kōhō. Shin bushidō. Tokyo: Jitsugyō no Nihonsha, 1908. pp. 167-223.

Yampolsky, Philip B. trans. The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings. Columbia University Press, 1971.

Yokoi Shōnan. “Kokuze sanron” Watanabe Kazan, Takano Chōei, Sakuma Shōzan, Yokoi Shōnan, Hashimoto Sanai (Nihon shisō taikei Volume 55). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1971, pp. 438-465.

Yoshida, Shōin. Yoshida Shōin zenshū Volume 4. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1940.

Yu, Jimmy. “Contextualizing the Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Chan/Zen Narratives: Steven Heine’s Academic Contributions to the Field,” Religious Studies Review, 37:3 (Sept. 2011), pp. 165-176.

Notes

Benesch, Oleg, Inventing the Way of the Samurai; Friday, Karl F., “Bushidō or Bull?”; Hurst III, G. Cameron, “Death, Honor, and Loyality.”

For a critical examination of Herrigel, see Yamada Shōji, Shots in the Dark. Also: Victoria, Brian, “A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan.”

Yamada Shōji has examined Herrigel’s interactions with Awa to show that Herrigel read his own “Zen” interpretations into key situations where communication failed due to the language gap. Awa’s accounts of these events differed considerably, and he himself had no particular connection with Zen. Yamada Shōji, “The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery,” p. 11.

Stone, Jacqueline L., “Chanting the Lotus Sutra Title,” p. 147. This assertion is also made in Takagi Yutaka, “The Nichiren Sect,”; Tanabe Jr., George J., “Kōyasan in the Countryside,” p. 49.

Goble, Andrew Edmund, Kenmu: Go-Daigo’s Revolution, p. 74; Colcutt, Martin, Five Mountains, pp. 94-95.

Varley, Paul and George Elison, “The Culture of Tea,” p. 205; Colcutt, Martin, Five Mountains, pp. 99-100.

Dumoulin, Zen Buddhism: A History, p. 283; Yamada Shōji, “The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery,” p. 11.

Recent examples of this connection include: Cleary, Thomas, Training the Samurai Mind, pp. 127-132; Besserman, Perle and Steger, Manfred, Zen Radicals, Rebels, and Reformers, pp. 152-153.

Hurst III, Armed Martial Arts of Japan, pp. 70-71; Bennett, Alexander, Kendo: Culture of the Sword, p. 46.

Mary Evelyn Tucker has written of this group of scholars that “for each of them the religious dimensions of Confucian thought were an important bridge to Shinto.” Tucker, Mary Evelyn, Moral and Spiritual Cultivation in Japanese Neo-Confucianism, p. 28.

Yamaga Sokō, Yamaga Sokō (Nihon shisō taikei 32), p. 334; Yoshida Shōin, Yoshida Shōin zenshū (Volume 4), p. 240.

Saiki Kazuma et al. eds., Mikawa monogatari, Hagakure (Nihon shisō taikei Vol. 26), p. 399 (Book 6-21).

Victoria, Zen at War, p. 18; Snodgrass, Judith, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West, p. 132.

Katsu Kokichi, Teruko Craig trans., Musui’s Story; Buyō Inshi, Mark Teeuwen, Kate Wildman Nakai, et al. Lust, Commerce, and Corruption.

For example: Ikushima Hajime, Seidan tōron hyakudai, pp. 88-89; Fukuhara Kenshichi, Nihon keizai risshihen, pp. 17-20.

These texts include Fukuzawa Yukichi’s 1893 “Yasegaman no setsu,” Suzuki Chikara’s 1894 “Kokumin no shin seishin,” and Uemura Masahisa’s 1894 “Bushidō to Kirisutokyō.” For a discussion of the development of bushidō discourse, see Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai, Chapter 2.

For a discussion of these efforts, see: Benesch, Oleg, Inventing the Way of the Samurai, pp. 85-87, 132-134, 164-167.

For a discussion of Nogi’s relationship with bushido, see Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai, pp. 150-156.

Translation by Christopher Ives. Found in: Ives, Christopher, “Ethical Pitfalls in Imperial Zen and Nishida Philosophy,” p. 17.

Shaku Sōen, Sentei roku, pp. 154-186; Arima Sukemasa, “Bushidō ni tsuite,” pp. 273-284; Yamagata Kōhō, Shin bushidō, pp. 167-223; Katō Totsudō, Zen kanroku, pp. 22-60.

Victoria, Brian Daizen, “A Buddhological Critique of “Soldier-Zen” in Wartime Japan,” pp. 119-120.

For a discussion of Nitobe’s role in the development of bushido, see Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai, pp. 90-97.