Introduction

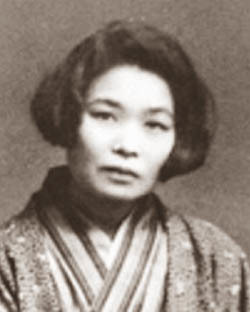

Born in Tottori Prefecture (where her last name is pronounced Osaki rather than Ozaki1), Osaki Midori (1896-1971) was the fourth of seven children in a middle-class, intellectual family. Her mother was the daughter of the head priest of a Buddhist temple; her father was a teacher, who died while Osaki was a teenager. Osaki graduated from the Tottori Girls’ School (Tottori Jogakko), and, at age eighteen, became an elementary school teacher. Aspiring to a literary career, she wrote poetry, essays, and fiction and sold a novel for schoolgirls (shōjo shōsetsu) to Shōjo sekai (Girls’ World) magazine in 1917.

In 1919, Osaki moved to Tokyo to study at Japan Women’s University. Her three older brothers had earlier pursued higher educations, attending the naval academy, Tottori University, and University of Tokyo, respectively. Osaki’s story “From the Doldrums” (Mifūtai kara) appeared in the general interest literary magazine Shinchō (New Currents) in 1919, making her name known. However, running up against the university’s policy prohibiting students from publishing literature in commercial venues, she withdrew from school in 1920 to become a fulltime writer.

Osaki strove to make a life for herself in Tokyo and to be part of the literary world centered there, for which acceptance often required the support of established writers and editors and the sale of works to magazines and newspapers. In the 1920s and 1930s, Tokyo was the epicenter of the intensification of historical and literary trends that had begun earlier, including rapid urbanization, the rise of new social groups and changing gender roles, diversification of mass media, development of popular entertainments, as well as increasing control of the police state and imperialist ventures. Tokyo was a magnet, then as now, drawing people from other parts of Japan and throughout the empire, seeking employment, education, and excitement. But, for women, a move to the capital often meant leaving behind the protective space of the family, breaking with the patriarchal system that was the basis of society. In Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense (Dainana kankai hōkō, 1931), as in her other works, Osaki expresses the alienation that many individuals experienced in the capital. She portrays unconventional familial relationships formed among youth seeking to establish themselves in Tokyo. Her female protagonists endured difficult living conditions, as Osaki herself did.

Osaki associated with authors representing diverse ideological and aesthetic goals who sought to expand the scope of Japanese literature. Most scholars have classified Osaki with the Tokyo “modernists” (then more commonly referred to by the factions to which they belonged) who were experimenting with unorthodox techniques to respond to their modern moment, which they saw as marking a break with the past, and who sought to convey the allure and contradictions of Tokyo. Many modernist writers were critical of the proletarian literature about Tokyo being written at the time, which they saw as prioritizing politics at the expense of aesthetics and as focusing solely on despair. Yet they shared a similar concern with Marxist writers in capturing the details of daily life under capitalism as part of a larger critique. So-called modernists and Marxist writers contributed to periodicals and books sponsored by the same publishers (for example, Shinchō and Kaizō) in the 1920s, suggesting that their rivalries might not have been as implacable as contemporary scholars believe them to be and that editors had their eyes on the market and knew both literary forms could sell.

Unskilled at social interactions and unable to find enough work, Osaki lived in abject poverty. Hayashi Fumiko, aspiring author and contributor to Nyonin geijūtsu (Women’s Arts) magazine to which Osaki sold many works, appreciated Osaki’s talent and respected her as a person, but Osaki lacked the perseverance and social skills that enabled Hayashi to overcome an impoverished, anonymous, and degrading life. She was able to continue writing thanks to financial support from her mother in Tottori to supplement income received from her part-time work, as well as assistance from author Matsushita Fumiko, whom she had met at Japan Women’s University. In 1932, Osaki—who had lost her emotional balance due to the side effects of medications used to treat migraine headaches and was perhaps suffering from the end of her brief cohabitation with Takeo Takeshi, a writer ten years her junior—was forced by her oldest brother to return to Tottori; there she was hospitalized for a mental breakdown. Although she regained her health, Midori abandoned her literary career and publically announced in 1941 that she was finished writing. Withdrawing to her remote hometown, she ceased contact with the Tokyo literary establishment, stopped publishing, and took care of her nieces and nephews amidst the social upheaval of the war. For years, her writings were overlooked by authors and critics.

Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense, often viewed as the culmination of Osaki’s modernism and her signature work, was published in two parts in the March and April 1931 issues of the literary magazine Bungaku tōin (Literary Members) and a revised complete version appeared in the June 1931 issue of Shinkō geijutsu kenkyū (New Arts Research). The book version was released in 1933, and Osaki attended the launch in Tottori. The story is told in a light, humorous tone by Ono Machiko, a young woman who has left behind a quiet rural life with her grandmother to live with her brothers and former childhood crush in Tokyo. The male characters’ perspectives are communicated through letters, treatises, and conversations interspersed through Machiko’s narration. All four members of this “odd household” are devoted to their studies, unusual versions of fields developing at the time and which inspired Osaki’s literature—science, psychology, music, and poetry. Machiko aspires to write poems that capture the “seventh sense” but is unable to define this elusive sense at the interface of consciousness and unconsciousness that arises from but transcends everyday reality. She perceives inklings of it through trancelike moments. The five ordinary senses are heightened to the point of discomfort—smells are disgusting, sounds discordant, tastes bitter, touches cause shivers, and sights are blurred or painful to behold. Sensory perceptions are conveyed through strange combinations of words (for example, voices grow moist). None of the characters have the intuition of the sixth sense (dairokkan).

Names are important to the relationships, themes, and motifs of the story. The given names of the narrator’s brothers contain the numbers one (Ichisuke) and two (Nisuke), and her cousin’s name (Sangorō) is comprised of the numbers three and five. (Four is skipped perhaps because it is an unlucky homophone for death.) The name of the character Yanagi Kōroku who appears later in the story contains the number six. The sequence perhaps counts up to the seventh sense. Throughout the story, precise measurements are given, furthering numerical motifs. The narrator often deliberately uses first and last names when referring to her brothers and cousin, which causes an odd distancing effect for the reader; the men, in turn, refer to her as the “girl” (onnanoko). The name Ono Machiko playfully echoes the name of Ono no Komachi, the legendary early Heian court poet renowned for her exceeding beauty. Long, straight hair, one standard for feminine beauty in the Heian era (around 794-1185), is an ironic contrast to the narrator’s reddish, frizzy hair and furthers the main theme of failure in love.

All characters are obsessed with romantic love—past, present, and future. They become embroiled in love triangles and suffer from the heartbreak of unrequited love. Machiko defines the psychological disorder of schizophrenia in terms of love triangles; and love triangles are the topic of the comic operas Sangorō sings. Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense can be read as parodying the romantic film comedies popular at the time, in which misunderstandings were resolved into happy endings, and a history of Japanese sentimental literature, from confessional writings to stories for schoolgirls, in which they often were not. Only the moss that Nisuke cultivates with manure succeeds in falling in love.

Love is also expressed as a main symptom of the various forms of “schizophrenia” (bunretsu shinrigaku) that Ichisuke studies. Scholar of Japanese literature and film Livia Monnet notes that Osaki made up the name of this psychological disorder, that, according to the afterword of the complete version of the novel published in (Shinkō geijutsu kenkyū), parodies Freudian psychoanalysis about which Osaki was well-read.2 This love-initiated schizophrenia also reflects Osaki’s interest in the motif of doubles and doppelgängers—as thematized by the likes of Edgar Allen Poe and the Surrealists—as a screen upon which to project unconscious anxieties. In the January 1930 issue of Nyonin geijutsu, Osaki published a translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s horror story Morella (Morera), which is narrated by a woman who studies philosophies of identity and gives birth to a daughter that uncannily resembles the narrator’s mother.3 Doppelgängers are hinted in the fragment of the title of the book Ichisuke asks Sangorō to buy. Machiko is said to look like a minor foreign poet.

In addition to her training in classical Japanese literature and her forays into foreign literature, theories, and music, Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense reflects Osaki’s knowledge of film. Osaki was the first woman to try her hand at film criticism, and starting in 1930, she wrote a monthly column of “Random Jottings about Film” (Eiga mansō) for Nyonin geijutsu. Her film writings included analyses of Charlie Chaplin comedies, the physical humor and pathos of which she injected into her stories, and observations of female filmgoers.4 Indeed, Osaki’s works impart the sensibility of a viewer in a theater engrossed in a silent movie. Osaki deployed cinematic techniques in her writing, including rapid scene shifts, physical gags, pans, close-ups, and montage. Montage puts images together in ways that condense the narrative and draws attention to symbolic meanings of individual sights and sounds. Almost in the manner of Freudian free association, objects, particularly food (from salty local specialties and unripe oranges to the pungent greens grown by Nisuke) illuminate the disconnect between the characters. Machiko is responsible for kitchen duty, a job commonly assigned to women, but she is often unable to prepare meals. Instead, characters mostly snack. As in the case of books and clothing, both Japanese and foreign foods appear in the story. Machiko’s bobbed hair might be a reference to foreign film actresses, as well as marking a break between her past life in the countryside and efforts to integrate herself into Tokyo.

In the 1960s, Osaki’s stories were rediscovered by literary critic Hanada Kiyoteru. Thanks to Hanada, Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense was included in a volume of Black Humor (Kuroi ūmoa) in a series on Discovery of Modern Literature: Collected Works (Zenshū—gendai bungaku no hakken) in 1969. The reevaluation of her work began with Hanada’s comparison of Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense to the literary impact of works by such 1960s authors as Abe Kōbō and Ōe Kenzaburō. Hanada deemed Osaki’s unconventional style and humor as “urban modernist,” firmly establishing the basis of her subsequent reevaluation. For example, Abe and Osaki similarly create a world of grotesque literature arising from the decadence of the city following its destruction in the 1945 firebombings. Their work is filled with discordant notes, and at the same time, represents an absurd world in which tragedy and comedy intermingle. In 1971, while delighting in her rediscovery and in the news of the reissue of her works, Osaki died of pneumonia. A single-volume of her collected works (Osaki Midori zenshū) was edited by author and literary critic Inagaki Masami and published in 1979 (Tokyo: Sōjusha).

Osaki displayed a writer’s individuality within a social milieu that restricted the expressive practice of women. As exemplified by Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense, Osaki’s literature is marked by an anti-realist, anti-worldly imagination, which conjures a fantastic realm beyond the everyday. Postwar authors, such as Mori Mari, Yagawa Sumiko, Yū Miri, and Tawada Yōko have extended the perspective of Midori’s modernism. These women skillfully utilize the subjectivity of a young girl who rejects maturity and the feminine interiority promoted by patriarchal society. Osaki’s literature, as well as her life, continues to attract the attention of writers, filmmakers, and scholars. The 1998 film In Search of a Lost Writer: Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense (Dainana kankai hōkō: Osaki Midori o sagashite, written by Yamazaki Kuninori, directed by Hamano Sachi) was financed in part through donations from women’s groups throughout Japan.5 The film combines interviews about Osaki and dramatization of her life with a staging of Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense. As noted in Noriko Mizuta’s preface to this special issue, among Kyoko Selden’s last unfinished projects was an edited volume of translations of Osaki Midori’s literature, which was to include Miss Cricket (Kōrogijō, 1932, translated by Seiji M. Lippit, published in More Stories By Japanese Women Writers [Kyoko Selden and Noriko Mizuta, editors]) and the play Apple Pie in the Afternoon (Appurupai no goro, 1929). The following are the first sections of Wanderings in the Realm of the Seven Sense, the full translation of which is only available in the Review of Japanese Culture and Society (Volume XXVII).

Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense

Some time in the distant past, I spent a brief period from autumn to winter as a member of an odd family. And I seem to have had a certain experience of love.

In this family, every member, including me, who occupied the maid’s room with its northern exposure, was an assiduous learner, and we all desired to make some contribution to a corner of life. In my eyes, everyone’s study seemed meaningful. I was at an age when I was apt to think of things in that way. I was merely a girl with frizzy, terribly reddish hair, and my official work in the household was kitchen duty, as my status as resident of the north-facing room would suggest. But unbeknownst to the others, I had the following objective of my study: I would write poems that would reverberate in the human seventh sense. After they filled a thick notebook…Ah, I would wrap the notebook brimming with poems penned in small characters and send it by registered mail to a teacher with the most developed seventh sense. Then, all he would need to do would be to read my poems, and I would not have to expose my frizzy hair to him. (I used to feel restrained by my hair.)

Such was the objective of my study. But I only had a vague notion of what it entailed. Besides, I had no idea what form the human seventh sense took. So, in order for me to write poems, I had to first find a definition of the seventh sense. Because this was a hard task replete with indecision, my poetry notebook tended to be blank.

Ono Ichisuke was the one who appointed me to kitchen duty, and Sada Sangorō was probably the one who enthusiastically supported the idea. The reason is that Sada Sangorō had worked three weeks as the cook prior to my joining the family. Those three weeks were miserable for him in many ways, and I heard that he was such a bad cook that he had even burnt miso soup. The household also included Ono Nisuke. I was the cook for all three men. While I am on the subject of names, let me add a few things about my name. I am Ono Ichisuke and Ono Nisuke’s younger sister and Sada Sangorō’s younger cousin. My full name is Ono Machiko, but because this is the kind of name that behooves a woman of great beauty, it made me uncomfortable to ponder it. Nobody would imagine that a name like this would belong to a skinny, red-haired girl. So I thought that I should come up with a name better suited to my poetry and to myself once my thick notebook was filled with poems.

My grandmother had bought my basket for me when I was about to leave home to take up kitchen duty. The first items that she packed in it were medicines: gomisin, or dried kazura japonica berries, and finely chopped mulberry root. She firmly believed that these were special remedies for reddish, frizzy hair.

After she finished packing, my grandmother sighed deeply, facing the still open basket, and said to me:

“Seven parts gomisin and three parts mulberry strips. Don’t forget the proportion. Patiently boil them thoroughly in a ceramic pot. When the water boils down to half, soak a hand towel in it, just like Grandma has always done for you. Wring it while it is still hot and apply it to your hair to stretch the frizz. Don’t forget to smooth the unwanted curls every morning. Do it carefully. Soak and wring the towel repeatedly. Do it many times.”

As her voice grew moist, I had to whistle louder. But my whistling did not seem to have much effect. My grandmother sighed again, looking toward the basket:

“Ah, you were born lazy, through and through. I doubt you will straighten your hair every morning. You won’t care about your appearance. But I hear girls in the city are stylish and pretty.”

I could do nothing about my whistling growing weaker. I stood up and went to the kitchen for a drink of water. And in fact, I drank two large teacups of water, which helped me to whistle loudly again.

After whistling loudly in the kitchen for a while, I returned to find my grandmother, having wiped away her tears, removing the hair-care medicines from the basket. She then made individual packets, each containing the proper dosage of the two medicines. Making packet after packet wrapped in the paper from the sliding doors cut into squares, she added:

“Still, no matter how stylish and pretty city girls may be, the most important thing is one’s disposition. I hear that, as far as the ancient gods were concerned, the frizzier a woman’s hair, the more kind-hearted she was. The Sun Goddess, too, must have had curly hair. Listen carefully to what your brothers have to say and try to get along with Sangorō as you lead your life. . . .

My grandmother’s tears fell into my hair-care packets.

My basket, too new for the above reason, made Sada Sangorō’s dark-blue kimono and kimono jacket with white splash patterns look old and worn as he held them in his hand. Because he was preparing to take the entrance examinations for music school a second time the following spring, he looked somewhat sad to me, even with his back turned. But seeing him like this, I sympathized with his difficulties. He had sent me a number of letters, written in his clumsy handwriting and writing style, about how crestfallen a student preparing for entrance examinations feels.

As Sangorō and I approached the house, I could see mandarin oranges a little over one centimeter in diameter growing on the trees that formed a hedge around it, shining in the sun and looking almost the same color as the leaves. I then realized that a net containing mandarin oranges still hung from my hand. Unaware, I still held the oranges I had not finished eating on the train. Anyway, how underdeveloped the mandarin oranges on the hedge were—they later turned into homegrown fruit, imperfect and shockingly behind the season, with bumpy skin and many pips and not much larger than two centimeters. They were sour. But they looked beautiful under the stars on a late autumn night, and, despite their sourness, they were later to help with Sada Sangorō’s love. He ate half of one of these two-centimeter oranges and gave the remaining half to the object of his affection. Partly because I need to tell my story in order, I will have to save the episode of Sangorō’s love for a later time.

The single-story house surrounded by the hedge looked so old that the three name cards posted at the entrance appeared strikingly bright. Of the three cards for Ono Ichisuke, Ono Nisuke, and Sada Sangorō, only the first two were printed. Sangorō’s name was inked in thick brushstrokes on a piece of cardboard. As he had written in one of his letters: “A student preparing for examinations is lonely. And a student who has to take examinations twice is even lonelier. Both Ono Ichisuke and Ono Nisuke must have long forgotten this feeling. You, Ono Machiko, alone will understand it.” At the very least, perhaps writing his name in thick brushstrokes on the card kept his spirits up.

Because Sangorō entered the house through the window by the genkan and opened the door right away, 6 I stopped looking at the name cards and went into his room. But incidentally, that letter from Sada Sangorō continued:

As proof of the fact that Ono Nisuke has long forgotten how I must feel, he boils fertilizer almost every night, and the odor from his room, separated from mine only by a corridor, is unbearable. So I have to take shelter in the maid’s room, which is on the other side of the house. Because boiling fertilizer is the basis of his graduation thesis, the odor comes often. Well, even if this escape helps me to tolerate the odor, I am forced to pull out the bedding from the closet and go to sleep early in the evening because the maid’s room has no electricity. When I have things to do, I need to use candlelight. Tonight, too, I am writing this letter on the tatami of the maid’s room. I feel sad. The odor, which is particularly intense tonight, diagonally crosses the corridor, streams toward the genkan, moves into the dining room, cuts across the kitchen, and leaks into the maid’s room. On such a night, I am so sad that I feel like banging on the piano.

Suppose I decide to tolerate the stench. It is annoying when someone else occupies the maid’s room before I can. Because Ichisuke lives next door to Nisuke in rooms divided only by a row of sliding paper doors, he seems used to the usual amount of odor, but on a night when the fertilizer smell is too intense, he takes shelter in the maid’s room before I can and studies in my bedding under my candlelight. He hardly lifts his eyes from his book when he orders me:

“If you have some studying to do, how about lighting another candle and getting under the covers at the bottom end? The odor from boiling a lot of fertilizer gets in the way of studying. Burnt ammonia smells almost the same as sulfur.”

I step away from the maid’s room and go to the public bathhouse, leaving both of my windows wide open. Then I watch a banana seller at a night stall until all the bananas are sold. Or I carry Ichisuke’s bedding into my room and get as close as possible to the open windows for fresh air, while silently mouthing my pitch-training practice.

Because neither Ichisuke nor Nisuke can stand music at night, they tell me to study during the day while they are out. When will I be able to enter music school? I do not even know myself. Tell me what you think, Ono Machiko. May your words lift my spirits.

Because Nisuke is still boiling fertilizer, tonight I will write another important thing. I have been meaning to write this important thing for some time, but I have been unable to do so. It is something I would like to tell only Ono Machiko. Please understand that. This is how it is.

The other day, a teacher at the branch school (the preparatory music school where I commute every afternoon) laughed at my pitch-training practice. Commenting that my semitones were unstable, he let out a nasal laugh that sounded like “boo-hmm.” I left school dejected and ended up buying a large sailor’s pipe. Rather than having bought it on a whim, I think the teacher who laughed at me instead of scolding me about my pitch is to blame, but I wonder what Ono Machiko thinks. People seem to prefer being yelled at to being laughed at for their failures! In particular, the shorter the laughter the less chance of dejection!

The sailor’s pipe I fancied at the pipe shop was three times as expensive as I had expected, and I spent most of the money Ichisuke had entrusted with me to purchase a book titled Doppel–something for him.7 Since then, I have been postponing my trip to the Maruzen bookstore. And I tell Ichisuke that I go to Maruzen daily but that Doppel-something has not yet arrived.

Having stowed the pipe behind the piano without once using it, I showed it to a ragman who happened to pass by in the morning when neither Ichisuke nor Nisuke was at home, and he appraised it at 30 sen.8 What nonsense! I envied the ragman and wished I could buy a copy of Doppel-something for 30 sen. And my last wish is that Ono Machiko could join us as soon as possible and save me from my dire situation. If it seems you will not arrive here on schedule, please ask grandmother for the money right away and send it to me. Doppel–something probably costs 6 yen, the amount Ichisuke gave me.

It is true that I left several days earlier than planned because of this letter. But my early departure was not to save Sangorō from his dilemma. I had already provided for his expenses, and the amount came from the money my grandmother had tucked in the pocket she sewed on the front of my kimono undergarment. She had instructed, “When you go to the capital, it will soon be winter. You will need a new scarf to keep you warm. One from the country will certainly look inferior to those worn by girls in the capital. Use this money to buy one you like. If you don’t know how to choose an appropriate pattern, ask Sangorō to go with you, and together you can select one on a par with those worn by the city girls.”

The money in my undergarment was just too opportune. I secretly changed it into one 5-yen bill and five 1-yen bills, and enclosed the amount Sangorō had requested in his letter. Then I put the remaining four 1-yen bills back into the pocket and fastened the hook. My grandmother had attached a hook-and-eye to the pocket. Saying that hooks and eyes are very convenient, she kept a number of them, which she had removed from my worn-out summer clothes, in her sewing box.

My departure had been hastened by a vague feeling.

Sangorō lived with his piano in a 1.5-tsubo room by the genkan.9 The piano looked so old that, had it been placed in a parlor or a similar place in a newly built house, it would have required a fine cloth cover. I was told that Sangorō had rented it from the landlord along with the old house. By the piano was a revolving stool, whose seat was more exposed cotton padding than velvet upholstery cover. Sangorō sat on the furoshiki he had spread on top,10 and talked to me while eating a mandarin orange from my net sack. I listened, sitting beside my basket. Behind him was the piano, its lid open, and the sailor’s pipe, still holding ashes, was perched on top of the keyboard. This is what Sangorō explained: “I rented this old, single-story house because it came with a piano, but after three weeks, I realized that it was the worst possible place for us. As long as we live with Ono Nisuke, we need a two-story house. Fine if there is no piano. Why don’t we find a slightly newer place with two rooms on the second floor for Nisuke and Ichisuke, and you and I can stay on the first floor.” (Sangorō put the peel on the piano keyboard and took another orange.)

“If the two of us look together, we will soon find a nice house. Nisuke can boil as much fertilizer as he likes upstairs. Odor tends to rise, so it won’t bother us on the first floor. On evenings when Ichisuke takes shelter downstairs—when Nisuke heats fertilizer in test tubes, the smell is not so bad, but when he uses a big ceramic pot, it is unbearable. So Ichisuke will naturally take shelter on the first floor from time to time—then, I will let him use my room, and I will take shelter in your room. If we live on separate floors, I can sing my pitch-training pieces at night. Under the present circumstances, I go to the branch school in the afternoon, and at night Ichisuke and Nisuke keep me from practicing, so I do not have time to study. In the morning, after Ichisuke and Nisuke go out, I am very sleepy. You see, I have been the one to wake early every morning and fix breakfast. Our initial understanding was that Nisuke would help with the cooking until you arrived, but he never once did. His excuse is that he stays up until late researching his graduation thesis, but you never saw a late riser like him. Besides, he asks me too often to collect fertilizer for him. Anyway, if the present situation continues, I am bound to fail again. I do not want to fail the examinations for music school twice in a row. So let’s, the two of us find a two-story house as soon as possible. We will quickly move while Ichisuke and Nisuke are out. We will need to rent a cart to carry our belongings, but I suppose you have the money for the fee. It does not cost much at all. Everyone has some extra pocket money when they first arrive in Tokyo. Let’s go ahead without saying a word to Ichisuke or Nisuke. Once we move all our belongings and fix up the second floor, we can send letters by special delivery to Ichisuke’s hospital and Nisuke’s school. Or it might be enough to post our new address at the entrance of this house. They will be content if they have rooms where they can study. They are so lackadaisical that they do not even complain about meals unless the rice gets badly burned. Nisuke’s belongings like test tubes, seedbeds, and ceramic pots are tricky to move, but you and I will just have to carry a few items at a time by hand. That means we cannot move too far, and the moving expenses will be modest.”

After a few orange peels sat in a row on the piano and the net was empty, Sangorō started smoking his sailor’s pipe. He moved on to a new topic. His pipe was not as large as he had described in his letter: “That money put my mind to rest. Right away, I bought a copy of that book at Maruzen and handed it to Ichisuke, and he is now studying it. The title of the book, Doppel–something, translates into Japanese as ‘schizophrenic psychology.’ The hospital where Ichisuke works accepts only abnormal patients with this ‘schizophrenic psychology,’ and the doctors there make it their mission to change them to have a single state of mind. The fine points of this psychology is difficult for us to understand, but it helps that Ichisuke does not do his experiments at home the way Nisuke does. And as for the money, I will repay you when my father sends my allowance at the end of the month.”

I had opened the lid of my basket and was eating caramels and leftover Tanba’s famous chestnut yōkan.11 It was already past noon, and I was hungry. Sangorō took yōkan out of my hand and started to eat it. He removed from the basket the preserved persimmons that had been hung under the eaves to dry and shared them with me. My grandmother had put the persimmons in the basket for me to enjoy on the way, but I had held back because I felt some compunction about eating on the train things so rich with the flavor of the mountain country.

Sangorō also seemed hungry. Placing the sailor’s pipe on the piano, he stood up from the stool and began searching the basket. Regardless, wasn’t he too rough with the piano? One glance at the keys was enough to detect their miserable, trashy hue, somewhere between grey and brown. Still, it was a piano, a musical instrument. On the keyboard sat a line of orange peels, followed by a row of persimmon pits, followed again by the pipe still emitting smoke.

Sangorō took out the four boxes made of thin wood that I had bought at Hamamatsu and unsealed one. Fully packed inside were small dark brown beans. Sangorō plucked a few out of the box and tried them.

“Too salty,” he remarked. “Tastes bad. Don’t you have anything better?”

I, too, tasted these Hamamatsu fermented soybeans, called hamanattō for short. I agreed with Sangorō. Ono Ichisuke had made me promise to buy some at Hamamatsu Station. His postcard had ended: “Please get a few boxes. It is my favorite food. It would be safer for you to choose a train that passes Hamamatsu during the day. At night, I fear you might be asleep when the train stops at the station.”

Sangorō finally opened one of the hair-care packets from the very bottom of my basket. In response to his question about what it was, I explained its use. He replied: “You do not need to go through all that. These days curly hair is thought to be more beautiful. Wouldn’t it be better to cut your hair short and apply hot curling irons?”

I reached into my undergarment pocket and slowly pulled out the four one-yen bills. I asked Sangorō if, instead of returning the money I had sent him, he could add these bills to the total and buy me a scarf.

“I see. Then I will keep this money for now. You mean a scarf that costs ten yen? Soon, by the end of the month, I will take you to buy one with a nice pattern. But we are hungry right now, so let’s go out and eat some lunch. I have been hungry for a while, but I didn’t want to go to the trouble of fixing anything and didn’t have any money. This month I have had a terrible time because of that pipe.”

Sangorō went to lock the door, picked up my sandals, and threw them out the window. He then threw me out the window after them.

Originally published in 1931. This translation was taken from Dainana kankai hōkō (Tokyo: Kawade Bunkō, 2009) and Osaki Midori zenshū (Collected Works of Osaki Midori), vol. 1 (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1998).

Notes

William J. Tyler, Modanizumu: Modernist Fiction from Japan, 1913-1938 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 83.

Livia Monnet, “Montage, Cinematic Subjectivity, and Feminism in Ozaki Midori’s Drifting in the World of the Seventh Sense, Japan Forum 11.1 (1999): 60.

For analysis of Osaki’s translation, see Hitomi Yoshio, Envisioning Women Writers: Female Authorship and the Cultures of Publishing and Translation in Early 20th Century Japan (Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 2012), 244-47.

Miriam Silverberg, Ero Guro Nansensu: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 200-202. See also Kan Satoko, “Kaisatsu,” Dainana kankai hōkō (Tokyo: Kawade Bunkō, 2009), 183.

For information about the film, see “Midori (English).” Hamano later directed a film version of Miss Cricket.