In the Beginning

Horrified by the sight of the lynching of African Americans, Abel Meeropol wrote a poem called Strange Fruit that is perhaps better known in the form of the 1939 rendition by Billie Holiday. African Americans continued to suffer lynching for many decades after the American Civil War—mostly in the South, but also in many other states all around the country. Being black meant risking being turned into a strange fruit hanging from a poplar tree, giving off the smell of burnt flesh as it swung in the southern breeze. Being black meant close proximity to death—by accidentally stumbling into a white person, by not adhering to prescribed etiquette, by not addressing a white person properly, or simply by making eye contact with a white woman. In a word, lynching could and did take place at the whim of certain white people. Hardly any explanation, let alone justification, was required. In some states, a lynching would be announced in advance in the local newspaper so that white people could gather and enjoy a picnic while watching it. Men and women, old and young, and boys and girls participated, eager and curious witnesses to the spectacle of black bodies being beaten, severed, carved, sliced, burned, and mutilated. Today, half a century after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, great numbers of black Americans die at the hands of police or while in police custody, reminding us that to erase a belief and the system that it is founded upon takes more than the declaration of a new law.

Being Korean in Japan during the twentieth century carried a similar peril for a long time. Being a chōsenjin (Korean) meant to be in a situation more likely to incur harassment, blame, penalty, or punishment. Perhaps the worst moment for anyone to be a Korean in Japan came in 1923 in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake, when pogrom-like hunt for Koreans spread across the scorched lands of Tokyo and its vicinity. Like the black bodies hanging from those southern trees, Korean bodies were on display without eyeballs, without nose, without breasts, their thighs and arms covered with lacerations and with very little skin surface intact (Ryang 2007). The end of Japan’s colonialism twenty-two years later did not of course end the peril of being Korean overnight. Just as the shift from public lynching to racial profiling, police brutality, and the disproportionately large number of incarcerations in the case of African Americans attests, for Koreans, too, the form of peril shifted as they were incorporated into a more formal, administrative apparatus.

In contrast with 1923, what Koreans faced in 1945 after thirty-six years of colonial rule was abject poverty, disenfranchisement, and tremendous uncertainty. One factor differentiating their case from that of African Americans persecuted in twentieth-century America was that their former colonizer, the Japanese, had been defeated by the Allied Forces and rendered powerless—as powerless as their former colonial subjects—making possible Korean independence. The majority of Koreans who were in Japan at the end of World War II did not view themselves as Japanese and considered it natural that they be repatriated to Korea now that Korea was an independent nation. And indeed, about 1.4 million Koreans voluntarily returned to Korea, following Japan’s defeat in 1945, leaving around 600,000 in Japan (Morita 1996; Ryang 1997: Ch.3). For those who remained, the peril of being chōsenjin continued, although, unlike the case of African Americans, their similar skin color with the majority of Japanese would create a different dynamic of discrimination and disenfranchisement. As well, especially for the Japan-born generations, their ability to speak Japanese as their native language (without any accent) would enhance their opportunities even given obvious limitations. But, such opportunities would only emerge after a generation or two of living in Japan. Following World War II, Koreans in Japan found themselves in a peculiarly fragile situation of being chōsenjin in the former colonial metropolis, their former masters defeated and forced to give up their colonial possessions and to rebuild their nation from the ruins of war. The story of Chongryun, or the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, begins here.

Genesis

In the early months of the Allied occupation of Japan, at a time when authorities were more open to liberal reform, wartime political prisoners were released, including several prominent Korean members of the Japanese Communist Party who quickly rose to leadership positions among the Koreans remaining in Japan.

The vast majority of Koreans in Japan had moved or been transferred to Japan from the southern provinces of the Korean peninsula during the colonial period. Like most other newly-liberated peoples in the post-WWII period, Koreans in Japan were fervently nationalistic, with even those self-identifying as communist more nationalist than Marxist. Thus, when the left-leaning Korean expatriate organization, known in Japanese as Zainichi chōsenjin renmei, in Korean as Jaeil joseonin yeonmaeng and in English as the League of Koreans in Japan (hereafter referred to using the abbreviated Korean name Joryeon), was formed in October of 1945, the hegemonic ethos was nationalism. The same applied to the anti-communist alternative for Koreans in Japan, Mindan which was formed shortly after the establishment of Joryeon.

Although the majority of Koreans in postwar Japan originated from the south of the Korean peninsula, most Koreans supported Joryeon which was more sympathetic toward the northern half of the peninsula under Soviet occupation, while Mindan supported the south under American military occupation. This was a reflection of the widespread belief that the partition of the Korean peninsula that had taken place in 1945 would be merely temporary. Moreover, Joryeon’s sympathy toward northern Korea was not exclusive; by locating its Korea office in Seoul, Joryeon preserved ties with the original homes of its members from the southern half of the peninsula.

This is an important point: Joryeon was not a North Korean organization and its goal was to enable all Koreans in Japan to repatriate to a would-be unified Korea. For, in the eyes of Koreans in Japan, the separate occupation of Korea’s northern and southern halves respectively by the Soviets and the Americans would be transient—indeed, why should it not be, since Korea had not played any hostile role in WWII against the Allied powers and Koreans who were conscripted and participated in the war did so as Japanese subjects (Fujitani 2011)? Moreover, the American Military Government occupying the southern half of the peninsula was deemed less favorable to Koreans than the Soviet one occupying the North. The primary reason for this was that the Americans relied heavily upon former colonial elements, while the Soviets entered Korea with the agenda of building a newly independent nation on a new footing, shedding the legacy of the colonial past. The Soviets brought to the fore indigenous Korean leaders of diverse persuasions, including Christians and anti-Japanese guerrilla veterans including Kim Il Sung (Armstrong 2003).

Divide

Once separate regimes began operating in each half of the Korean peninsula in 1948, however, the situation became immensely unstable, with deepening mutual animosity and numerous border skirmishes and confrontations along the line of partition, the thirty-eighth parallel (Cumings 1981). In Japan, reflecting rapidly rising Cold War tensions in East Asia and the rise of the People’s Republic of China, the Allied occupation took a radical anti-communist turn. One result was that expatriate Korean politics began exhibiting a clearer division with pro-North and pro-South orientations respectively sustained by Joryeon and Mindan.

Among Koreans in Japan Joryeon commanded broader and stronger mass appeal than Mindan. The operations of the former group encompassed a comprehensive assortment of activities, including community organization, propaganda, and, perhaps most importantly, Korean language instruction. Starting from October 1945, Joryeon built makeshift Korean schools in key urban areas where Koreans were concentrated. Behind this undertaking lay the assumption that all Koreans would soon be repatriated to Korea.

When the Occupation administration and Japanese authorities decided in 1948 that all schools would have to be accredited by the Japanese education authorities and that the sole language of instruction should be Japanese, mass protests erupted in the Korean enclaves. Koreans in Kobe, in western Japan, protested, insisting that they should be exempted from the ruling on the basis that they were former colonial subjects. When this protest was spurned, Koreans and Japanese supporters occupied the offices of the Mayor of Kobe and carried out street demonstrations in April 1948. The protests culminated in the shooting of unarmed demonstrators by military police, with one youth shot to death, a girl left to die from a head injury, and a Korean teacher dying while in custody in jail (Inokuchi 2000; Koshiro 1999). It is notable that this was the only incident in which martial law was declared during the entire seven-year Allied occupation of Japan. Even the waves of mass demonstrations led by the Japanese Communist Party did not result in a declaration of martial law. One can discern in this state of affairs the lingering figure of the chōsenjin as a group lacking basic rights in postwar Japan, a figure that posited more threat to American and Japanese authorities than did the Japanese left.

Purge

The legal status of the Koreans remaining in Japan remained ambiguous throughout the Allied occupation, often referred to as daisangokujin or third-country nationals, meaning neither Japanese nor Allied nationals. Koreans assumed that the end of Japanese colonialism meant that they had acquired civil and legal rights, including the right to engage in education in Korean language, culture, and history. The reality, however, was that Koreans in Japan were as stateless, if not more so, than they had been during the colonial period. Under the Allied occupation administration, they were, collectively, an unwanted legacy of the colonial era, initially deemed an anomalous population by the Allied powers as well as by the Japanese government, and later troublemakers that Japan would eventually rid itself of. Either way, chōsenjin were deemed unruly, and inferior to the Japanese.

Reflecting rapidly rising Cold War tensions in East Asia, with the rise of the People’s Republic of China, Koreans in Japan increasingly came to be seen as a serious problem, such apprehension peaking when Joryeon began publicly supporting the North Korean regime after its foundation in September 1948. In 1949, the Allied occupation and the Japanese government forcefully suppressed Joryeon. Its offices were shut down, properties confiscated, assets frozen, and arrest warrants issued for its leaders. This resulted in a strange twist in the history of the expatriate nationalist movement as remaining Joryeon activists joined the Japanese Communist Party, which already had a sizeable Korean contingent. Interestingly, the authorities allowed the JCP to remain intact, despite its conspicuous and often violent opposition to the Japanese government.

The situation underwent another drastic change after the Korean War broke out in 1950. In 1952, as truce talks continued between North Korea and U.N. forces, the North Korean foreign ministry issued a number of communiqués stating that its government was prepared to enter into a normal diplomatic relationship with Japan. Under these circumstances, Korean members withdrew from the JCP en masse and formed their own unified underground organization with the abbreviated Korean name Minjeon.

When the Korean War truce agreement was signed in 1953, Minjeon began a prolonged period of self-examination. Two years later, in May 1955, the forces organized under Minjeon re-emerged as the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (known in Korean as Jaeilbon joseonin chongryeonhaphwe or by its abbreviation Chongryun and in Japanese as Zainihon chōsenjin sōrengōkai). It soon embraced a diverse assortment of political organizations, including a youth league, a women’s union, a writers’ association, an artists’ association, a scientists’ association, an athletic union, merchants’ and entrepreneurs’ associations, and the Young Pioneers. Chongryun soon came to command mass support among Koreans in Japan for whom North Korea still had greater sway than South Korea, which remained under military dictatorship. It issued its own publications, not only in Korean, but also in many foreign languages, including Japanese, English, Spanish, and French and operated numerous business and cultural organizations including its own art troupes, soccer team, nationwide credit union, and film production company. Chongryun’s organizational network of local headquarters (sub-divided into lower branches and cells) extended to every prefecture from Hokkaido to Okinawa and was under the direction of Chongryun’s central headquarters in Tokyo.

Coexistence

The most formidable element of Chongryun’s organization was its independent school system, and its ability to sustain itself was closely related to its new identity as an organization representing North Korea overseas. In order to avoid the violent suppression suffered by its predecessor at the hands of the authorities in 1948/49, Chongryun declared itself to be an entity existing outside domestic Japanese politics. While Chongryun existed within Japanese jurisdiction, it defined itself as an organization that would not interfere in Japan’s internal politics. Thus, its criticism of the Japanese government was confined to issues involving Japan’s foreign policy toward North Korea. Chongryun did not demand Japanese citizenship or residential rights for Koreans as former colonial immigrants. Nor did it call for postcolonial reparations. Rather, its political focus was the promotion of North Korea’s position and securing mass support for the regime among Koreans in Japan.

Against the backdrop of what was later named the 1955 system, in which the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party reached a structural compromise with other parties including the JCP and Japan Socialist Party thereby making possible a certain peaceful co-existence, the declaration of non-interference in Japan’s domestic affairs by Chongryun created a situation that suited the Japanese authorities. This unusual situation – contrasting sharply with the situation in other Asian nations such as China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Korea, in which irreconcilable differences between left and right resulted in massive bloodshed – benefited Chongryun too. By presenting itself as an entity that was not demanding civil rights for Koreans in Japan or postcolonial reparations, Chongryun secured a semi-autonomous space for itself within Japan, enabling it to create an organization representing overseas nationals of North Korea.

Legally speaking, there was no such category as “overseas national of North Korea living in Japan.” Japan and North Korea did not have diplomatic relations (a situation that remains true today), so there is no legal structure allowing citizens of each country to reside in the other’s territory. Rather, this identity was politically and ideologically coded and reinforced by Chongryun through its propaganda, its public discourse, and, above all, its school system. This became a real identity for Koreans joining Chongryun, who proudly identified themselves with North Korea and refused to accept the label of a marginalized minority in Japan. The Japanese authorities, while closely monitoring and collecting intelligence on Chongryun, also maintained the stance that would be characterized as laissez-faire, so long as Chongryun did not exceed the boundaries.

Growth

International trends in the 1950s and 1960s were on Chongryun’s side: North Korea, in contrast to the US-backed South Korea, looked almost heroic in singlehandedly resisting the U.N. invasion during the Korean War. (This was not, of course, true, as the Chinese People’s Army and the Soviet Union provided crucial support.) Its economy demonstrated strong growth, while South Korea struggled with massive poverty under the constraints of a severe military dictatorship which monopolized postcolonial settlement funds from Japan and redistributed them among the large jaebeol enterprises, leaving the vast majority of people in deplorable conditions. The continued heavy US military presence emphatically reinforced the image of South Korea as an American puppet, while North Korea had rid itself of Soviet and other foreign forces (including Chinese Korean War volunteers) by the mid-1950s. North Korea began to be seen as a leading force among the non-aligned and newly independent nations of Asia and Africa. The popularity and rapid growth of Chongryun’s school system needs to be seen against this backdrop of North Korea’s increasing international standing.

|

A man in a Japanese ultra-nationalist demonstration holds sign stating: “Put the trash in the trash can; Send Koreans back to the Korean peninsula.” Photo taken from a blog site Tadashii rekishi ninshiki, kokueki jūshi no gaikō, kakubusō no jitsugen [The Correct Understanding of History, the National Interest-First Diplomacy, the Materialization of Nuclear Armament]. Source |

At its peak, Chongryun had more than 160 schools all over Japan from Hokkaido to Kyushu, including rural prefectures on the Japan Sea side of the archipelago, its institutions offering education at all levels, from kindergarten right up to graduate programs, and all-Korean instruction, except for Japanese and English classes. Subjects that were included in fourth through twelfth grades included “The revolutionary history of Marshal Kim Il Sung” and “Revolutionary activities of Great Leader Kim Il Sung.” Aside from promoting Kim Il Sung’s authority and authenticity as leader of all Koreans, Chongryun’s education was patriotic and nationalistic in tone, emphasizing the suffering that Koreans had endured during the colonial era, the pride that Koreans needed to feel with respect to their national traditions, and the superiority of Korean culture.

North Korea took notice, sending funds in 1956 to assist with the construction of the campus of Chongryun’s new university. Further funds followed in 1957, marked for educational subsidies. Until the early 1970s, Chongryun held frequent public meetings at which thanks would be offered for funds that had been sent by North Korea, primarily to assist with Chongryun’s educational activities.

The reason that such things were possible in Japan—not hidden in some obscure enclave, but openly and all over the country without repeating the 1948-style suppression under the martial law of Korean schools—was closely related to Chongryun’s strategic self-definition. By declaring itself to be a non-Japanese, North Korean organization, and by adopting the strategy of registering its schools as non-academic institutions (miscellaneous schools) or kakushu gakkō, thereby placing them beyond the purview of the Japanese education authorities, Chongryun was able to legitimize its identity to the massive population of followers that it acquired in the early days following its foundation. In exchange, Chongryun high school graduates’ education was not recognized as a GED equivalent. By explicitly de-emphasizing demands for civil rights within Japan, Chongryun was able to redirect the passion of its followers away from their disenfranchised civil status in Japan and toward the utopic (and positive) future of rejoining a reunified Korea, the genuine homeland of all Koreans remaining in Japan.

What is remarkable is not so much the fact that Chongryun’s strategy succeeded in certain ways, but the fact that hundreds of thousands of Koreans in Japan welcomed it, supported it, and eagerly enrolled their children in its schools—not only in order to raise their children as part of the future generation of a reunified nation, but also to shed themselves of the colonial past. For, even until well into the 1970s, the official ideal of the reunification of Korea and the eventual return of all Koreans to their unified motherland was alive and well among Chongryun Koreans. This should be seen not as simply the product of indoctrination, but rather more as part of a process of self-decolonization that Koreans in Japan opted for.

|

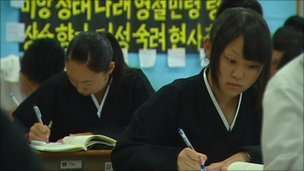

A glimpse at a Chongryun school classroom. Female students wear school uniforms made of modified Korean traditional dress for women. Photo source: Roland Buerk, “North Koreans in Japan Remain Loyal to Pyongyang,” BBC Asia/Pacific, October 28, 2010. Source |

I would also associate the broad and enthusiastic mass support that Chongryun enjoyed from its inception in 1955 through until the late 1970s with the primordial sense of being a chōsenjin, and the perils associated with such an identity, that every Korean in Japan experienced. For those too young to have experienced such a sense first-hand, their parents’ recollections of their poverty-stricken lives and lack of access to education, along with the raw anger and violence that they displayed to them domestically, would have sufficed. As recently as the early 1970s, Koreans in Japan continued to live tough and deprived lives. They were poor—much poorer than the Japanese poor. The typical education level of a member of the Korean population was extremely low, and they suffered from high unemployment (Ryang 2000; Ryang 2008). The combination of a lack of a steady livelihood, poor living conditions, unsanitary housing (often with limited access to running water and sewerage with shared communal outhouses), confined many Koreans to a slum-like existence. Even though the colonial era was over, deprived of their civil rights and with no stable residential status, Koreans hovered on the edges of Japanese society.

Repatriation

The repatriation of Koreans from Japan to North Korea, starting in December 1959 and lasting until the end of the 1970s, should also be understood as having taken place during a period when many Koreans in Japan were suffering from the effects of poverty and deprivation of all kinds. While Chongryun’s propaganda, often involving exaggerated claims relating to the benefits that were accessible in North Korea, played a large part in motivating Koreans in Japan to make the journey to North Korea, the peril of being a chōsenjin in Japan in the late 1950s and early 1960s was an ontological condition that Koreans lived every day and that made the option of being repatriated to North Korea emerge as a viable alternative.

From December 1959 through the 1970s, over 90,000 Koreans were repatriated to North Korea (Morris-Suzuki 2007). This was an anomaly, given that the majority of the returnees had originated from the southern provinces of the Korean Peninsula. But the North Korean promise of steady employment for parents, education for children, and better housing—all relayed by Chongryun in an emphatic propaganda campaign— looked extremely attractive to the poor Koreans. Besides, the assumption still remained that all Koreans would eventually be repatriated to the reunified motherland. While repatriating to North Korea meant a one-way journey with no possibility of return to Japan, many chose this option.

It needs to be underscored that the legal residential status of Koreans in Japan was left unresolved until 1965, twenty years after the end of WWII, which meant that Koreans were required to renew their limbo-like status as temporary foreign residents annually in person at local municipal offices including mandatory finger-printing—the rule applying to all Koreans above the age fourteen. Upon the normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea in 1965, permanent resident status became available—but only to those who opted to become South Korean nationals.

The 1960s were a decade deeply fraught with Cold War tensions in Korea, leading thousands of Chongryun followers to refuse to become South Korean nationals on the basis of their opposition to the brutal military dictatorship then in power in South Korea. This meant that the majority of Koreans in Japan remained stateless, as Chongryun commanded a far broader support base than did the pro-South Korean Mindan.

This situation created a perfect storm for Chongryun to fan the zeal for repatriation to North Korea among Koreans in the 1960s and well into the 1970s. During those decades, Chongryun solidified its already-strong ties with North Korea, the strength of the connection exemplified in the lavish list of gifts presented to Kim Il Sung on his sixtieth birthday in 1972—Mangyeongbong, the repatriation ship, left the Japanese port of Niigata filled with an inventory that included items as diverse as Mercedes Benzes and bushels of premium-grade Koshihikari rice.

As stated earlier, the zeal shown toward North Korea by Koreans in Japan in those days was a child born from perilous memories of a colonial past, as well as the abject living conditions and complete disenfranchisement from Japanese civic life that Koreans in Japan were subjected to during the 1950s and well into the 1970s. It was not until the 1980s that this pattern began to change, which was the product of several major historical factors: changes in the residential status of Koreans in Japan, changes in the South Korean political and economic environments, and Chongryun’s own internal strife reflecting a demographic shift in the Korean population in Japan from first-generation colonial immigrants to Japan-born generations.

Erosion

At the very beginning of the 1980s, Japan ratified the International Covenants for Human Rights and joined the UN Refugee Convention. These moves made it necessary for the Japanese government to amend its previous human rights breaches, including the deprivation of residential stability for those Koreans in Japan who had migrated to Japan during the colonial period (and their descendants) and who had not acquired South Korean nationality after the 1965 normalization of relations between Japan and South Korea. The majority of Chongryun Koreans belonged to this category. Starting from 1981, they were able to gain permanent resident status, which was accompanied with the ability to obtain re-entry permits to Japan.

This opened the possibility of Chongryun Koreans paying visits to North Korea and being reunited with their repatriated families. Even though diplomatic relations did not (and still do not) exist between North Korea and Japan, Chongryun Koreans became able to visit North Korea on humanitarian grounds for the purpose of visiting family members, including those that had been repatriated. Thus, during the 1980s, the ferry service between Niigata, Japan, and Wonsan, North Korea, came to be redefined as a family reunion route, replacing the one-way journey of repatriation. After experiencing an initial wave of emotion during their reunions, Chongryun visitors to North Korea realized that their repatriated families and friends were not living in a “paradise on earth,” as North Korean propaganda insisted. Instead, the lack of material means as well as the surveillance factor that Koreans in Japan were not familiar with made them increasingly uncomfortable. Although witnessing the material shortages motivated Koreans in Japan to send overseas remittances to North Korea, Chongryun followers came to feel not only deceived, but deeply concerned over the fate of their relatives, especially those that they had been unable to locate, growing increasingly suspicious of North Korea and Chongryun. With North Korean education funds long since stopped, many Chongryun Koreans came to the realization that North Korea was a land of material shortage and political repression.

Changes in the residential status of Chongryun Koreans in Japan came in stages. During the 1980s, every effort was made to intimidate Chongryun Koreans who applied for re-entry permits to visit North Korea and return to Japan. Upon their departure and arrival, their paperwork was subjected to excessive scrutiny, while it was not uncommon to hear the uniformed immigration officer utter words such as “chōsenjin no kuse ni,” equivalent of: “Who do you think you are, you f-ing Korean.” Each time that they applied for a re-entry permit, they were required to submit tangansho, a personal petition in writing using the polite form begging the Japanese Foreign Minister for the permit.

In the 1990s, reflecting the improvement in relations between Japan and South Korea following the end of the decades-long military dictatorship, Koreans in Japan were given a more comprehensive form of permanent residence on the basis of their colonial past, this time without a distinction being made between those who had South Korean nationality and those who did not. Moreover, demographic shifts in the Korean population in Japan meant that, now, the majority had been born in Japan and, therefore, calling North Korea or South Korea their motherland was basically a political act rather than a visceral or affective one. As such, sections of the Korean population in Japan, including Chongryun affiliates, began acquiring permanent residence in Japan; before long, they would acquire South Korean nationality.

The 1990s was a decade characterized by steady attrition in Chongryun membership and support for North Korea among Koreans in Japan on one hand and an equally steady increase in the number of Koreans in Japan acquiring South Korean nationality. The latter trend did not, however, signify a transfer of support from North to South Korea. Now that South Korea was governed by a civilian head of state, the act of acquiring South Korean nationality primarily seemed a matter of convenience for the purpose of securing a passport rather than continuing to rely only on a re-entry permit. For, by then, the majority Koreans in Japan had been born in Japan and had no intention of repatriating either to the North or the South. Reflecting the sea change in Europe and elsewhere after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the collapse of Communism, Koreans in Japan, too, entered a phase in which politics alone no longer ignited passions. While the lack of economic data relating to the Korean population in Japan makes it difficult to statistically demonstrate, by the end of the twentieth century Koreans were no longer living below the poverty line. Their livelihoods had improved, and they were enjoying the benefits of higher education levels and improved residential status in Japan, albeit slowly (Kim 2003).

Kim Il Sung died in July 1994, to be quickly replaced as North Korean leader by his son, Kim Jong Il. This dynastic succession became a substantial—and for many insurmountable —hurdle for Chongryun’s rank and file. Many distanced themselves from Chongryun and removed their children from its schools, placing them in Japanese schools, despite feeling extremely ambivalent about this.

Chongryun’s difficulties were compounded by a looming distrust in its leadership. Ever since its foundation, Han Deok-su had presided as its chairman. By the early 1990s, he and his family were living a life of luxury, occupying a massive mansion in a choice Tokyo neighborhood that was staffed with domestic workers, body guards, personal assistants, academic tutors for the children, chefs, and chauffeurs. His younger daughters had a limousine transport them between the residence and their school. Chongryun employees were paid very modest salaries, barely getting by with their rental payments, making Han Deok-su’s lifestyle stand out as being excessively indulgent. Given that Chongryun’s predominant sources of revenue were membership dues, school tuition fees, and charitable gifts from supportive Koreans, critical voices became louder. The rise of such voices reflected the inevitable demographic shift inside the Korean population in Japan. To older generation Koreans, Han represented the tough past which he survived to eventually build this formidable organization. For this generation, it was tolerable that he received special treatment. Younger, Japan-born Chongryun Koreans did not share such sentiments. In their more pragmatic approach to the future, it was inevitable that such treatment of the chairman’s family be seen as a great disservice to the unity of the organization, resulting in further attrition and distancing.

|

A Chongryun high school Korean dance club. Korean dance clubs are one of the most popular among female middle school and high school students of Chongryun schools in Japan. Photo credit: Emil Truszkowski , “What I Learnt at a N. Korean School Festival at Japan,” July 21, 2015, NKNews.Source |

Zainichi

By the end of the 1990s, Chongryun Koreans were no longer passionate about North Korea. Rather than pursuing the end of diaspora and an eventual return to the homeland, younger, Japan-born Koreans sought an alternative future in Japan. Even though some continued placing their children in Chongryun schools, their primary reason for doing so shifted from the ideological commitment of their parents’ generation to the lack of an acceptable alternative in the Japanese public education system, where the homogeneity of the population was fundamentally assumed and the basic historical sources of ire for Koreans, such as Japan’s colonial rule of Korea, was not taught properly, if at all. After haunting Koreans in Japan for nearly half a century, the figure of the chōsenjin was being replaced by that of the zainichi, a Japanese term denoting “being in Japan” or “existing in Japan.” Whereas in the past, the chōsenjin represented the face of the colonial—undernourished, speaking Japanese with a Korean accent, walking with strangely broad gait, and characterized by the colonial authorities as ignorant, insolent, and quick to resort to a fist fight, the zainichi had a different face—a native speaker of Japanese with a high level of education, perhaps enjoying minor commercial success, aware of his or her ethnic origin, yet dignified, assimilated into the Japanese cultural environment, while also knowing how to distinguish him or herself from the rest of Japanese society. The zainichi constituted a different form of existence from the chōsenjin. While the latter evoked ontological peril, the former denoted an alternative future in Japan, while building upon complex reflections on postcolonial life (Lie 2008).

For those Japan-born zainichi Koreans who were raised according to the tenets of Chongryun and who had lent it their support, the decades of the 1980s through 1990s proved to be crucial in marking Chongryun’s definitive fall from its status as the object of mass support. The gradual replacement of the figure of the chōsenjin with that of the zainichi cost Chongryun its political identity or raison d’être. Japanese society was changing, and the ethnic discrimination and sense of disenfranchisement that the chōsenjin had formerly experienced as parts of everyday life in Japan were becoming less pronounced. The figure of the zainichi would appear in public discourse, in a vast array of publications, including prize-winning novels, and even in popular films (Iwabuchi 2000; Kuraishi 2008; Ryang 2008b: Introduction). Whereas the chōsenjin was abominable and grotesque, in the public imagery of Japan, in the new millennium the zainichi appeared in a form comparable to that of a minor star, a cool alternative to simply being Japanese. In other words, the emergence of the zainichi stripped the political edge from Korean identity in Japan, somewhat normalizing or at least politically neutralizing it, thereby accentuating the prospect for Koreans born in Japan to be part of Japan, albeit in a special framework. This contrasted with Chongryun’s self-exile from Japan and its identification as a North Korean organization. In this new setting, the home of the zainichi was Japan, not North Korea or South Korea.

It must also be borne in mind that the very last decade of the twentieth century was a time of unprecedented optimism, albeit short-lived. It was the decade in which the Japanese left showed its final demonstration of integrity. In 1995, Japan Socialist Party Prime Minister, Murayama Tomiichi, issued a statement of apology for the sexual slavery of women from the Korean peninsula by the Japanese Army during World War II. On the local level, there was a hope for zainichi Koreans to gain wider civic enfranchisement and solidarity with their Japanese neighbors without having to compromise their identity. Some municipalities voluntarily abolished nationality hurdles for public service positions, for example, in order to accommodate the broader participation of zainichi Koreans in civic affairs (Chung 2003).

It was also around this time that the post-1988 liberalization of overseas travel for South Korean citizens began to have a real impact on zainichi life. The so-called newcomers began reaching ethnic enclaves that had hitherto been left without any tangible contact with ancestral homes in South Korea. Accompanied by a shift in the South Korean political environment from one of the most oppressive military dictatorships in the world to a civilian government, the influx of South Korean migrants as employees, co-workers, and business partners recast the divisive Cold War-inspired stance that had been rife amongst Koreans in Japan.

Yet another factor, which became evident in the early years of the twenty-first century, was the steady increase in the number of Koreans being naturalized as Japanese citizens. The number would reach an average of 10,000 to 15,000 per year during the early 2000s, indicating a fundamental shift in the area of postcolonial identity formation that involved practical considerations, such as gaining full citizenship, even though that citizenship was that of Japan, the former colonizer (Ryang 2010).

The trend toward gaining Japanese citizenship was a challenge to Chongryun’s program, which insisted that the homeland of Koreans in Japan was North Korea, that Korea would be eventually be reunified through the initiative of North Korea, and that all Koreans in Japan would repatriate to the reunified Korea to regain the national independence that had been taken away originally by Japanese colonialism and then through the partition of the peninsula that was the product of US imperialism and the cooperation of its South Korean lackeys. This platform implicitly relied on the continuing peril of being a chōsenjin.

The replacement of the chōsenjin with the zainichi, and perhaps, eventually, the zainichi as a Japanese citizen, was not a welcome development for Chongryun. Yet, the changing institutional and socio-cultural structure of disenfranchisement among Koreans that is now seen in the availability of a relatively permanent residence status has steered the dynamic for Koreans in Japan, especially those born in Japan, the numerical majority, away from homeland politics and toward an exploration of the possibilities for improving their livelihoods in Japan and contributing to reshaping Japanese politics. Chongryun lacked the proclivity, let alone the capacity, to respond to these changes, causing the organization to steadily lose legitimacy in the eyes of zainichi Koreans.

Death or Rebirth

The crisis in the legitimacy of Chongryun as shown above was, through yet another ironic turn of events, temporarily mitigated, as it were, by the robust rise of the rightwing and growth in all-out hostility toward North Korea in Japan in the early twenty-first century, trampling the short-lived optimism of the mid-1990s. In 2001, during a historic first meeting between Kim Jong Il and the then Japanese Prime Minister, Koizumi Junichiro, it was revealed that North Korean agents had kidnapped innocent Japanese citizens from Japan’s shores during the 1970s and 1980s. This revelation led to an all-out assault on Chongryun. Its assets were thoroughly audited, resulting in numerous charges of tax evasion and other illegal acts, subsidies that its schools had received from local governments (not from the central government) were suspended, the media began carpet-bombing Chongryun with hostile questions, and right-wing and ultra-nationalist organizations launched campaigns of intimidation and harassment against Chongryun schools, offices, and individuals, including women and children–not entirely unlike the repression of 1948 and 1949.

|

The 23rd congress of Chongryun, May 2014. The Large screen on the left front introduces the message sent from Kim Jong Un. The venue is filled with gray-haired participants, reflecting the younger generation’s distancing from the organization. Photo source: Korean Friendship Association, the official website of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Source |

Unprecedented audit assaults were waged against Chongryun offices, credit unions, businesses, and businesses operated by individuals that were sympathetic with Chongryun, revealing irregularities in tax payments, resulting in exorbitant fines, court cases, and arrests (e.g. “Tokyo Police Raid N Korea HQ” 2001). During the last decade and a half, Chongryun has lost a substantial portion of its assets including its now-defunct credit union, dozens of schools, press buildings, printing facilities, and most symbolically, its headquarters building in Tokyo. Funds from North Korea have long since dried up, while the donor basis has crumbled, with many entrepreneurs and business people expressing disenchantment.

|

The Japanese authorities raid Chongryun Headquarters in Tokyo. The tall white building in the left rear is the Chongryun Headquarters building. The building has since been sold to a non-Korean entity, although Chongryun is said to be renting it. Photo source: “Decision on Chongryon Site Delayed,” Japan Times October 22, 2013. Source |

What I meant by the ironic turn above is that the more persecutions Chongryun receives, the stronger Koreans unite around it. And indeed, the rage against Japanese ultra-nationalism which normally comes hand in hand with the state-staged audits would remind Koreans in Japan of the reality of disenfranchisement they continue to face. But, unlike the 1950s or even the 1990s, today, the threat is less acute: chōsenjin, the figure of anger and indignation, does not emerge in response to this persecution. Rather, zainichi strategize and make calculated moves in response to the situation. So, even though, temporarily and sporadically, Koreans are made to feel the necessity for action and representation of themselves as a group, the reaction is no longer the earlier reflex of uniting around Chongryun. How is it possible, then, that Chongryun continues to exist, albeit with a greatly reduced number of schools, each with far fewer students and teachers, with its press offices now operating in rented suites on a much smaller scale, and with very few Koreans even concerned with North Korea, save for the welfare of family members who were repatriated. Despite public denunciation of Chongryun by the Japanese media and right-wing organizations, despite repeated raids of its offices throughout Japan by Japanese taxation authorities, and despite visibly diminished support from Koreans in Japan, reduced, shrunk, disgraced, and weakened, Chongryun still exists.

Or, perhaps, it is developing a new relationship with North Korea in these post-2001 conditions of adversity. This can be glimpsed in the May 2015 arrest and indictment of Chongryun employees, including a son of current Chongryun chairman, Mr. Ho Jong-man. A charge was laid against four people, including Mr. Ho’s son, for illegally importing three tons of mushrooms from North Korea and using fake labels to suggest that they were imported from China: Japan had placed an embargo on North Korean trade since 2006 as punishment for the earlier kidnappings of Japanese citizens mentioned above (“Chongryon Chief’s Son Arrested over Suspected N. Korea Mushroom Imports” 2015). These mushrooms, known as matsutake in Japanese, are a delicacy in Japan and yield substantial profits. Pyongyang joined Chongryun in denouncing the Japanese authorities, a show of solidarity of a kind that had been absent for the past decade. It appears that Chongryun and North Korea have entered into a business partnership in illegally importing and selling North Korean products in Japan and possibly elsewhere. This form of relationship does not require a mass support base. Taken altogether, the current situation is something of a prolonged death for Chongryun as a mass organization of Korean expatriates in Japan. The open hostility expressed toward Chongryun functions something like a ventilator for the final breaths of this once robust organization. Its schools still exist, their curricula still including some North Korean material. Its performing arts company still exists, its repertoire having become less revolutionary and more traditional, so to speak. Its publications still exist, although the predominant language is now Japanese not Korean. Its public rallies still take place, albeit with notably thinning levels of participation—down from the thousands of participants of all age groups in its glory days to a few hundred seniors today. The skeleton of the utopia of Korean reunification coupled with the peril of being a chōsenjin clings to the final stretch of its life.

Ultimately, the chōsenjin has died its death through history—it was not through lynching or mob violence, but via historical shifts and structural readjustments that Koreans in Japan have been subjected. The chōsenjin came to be replaced by the zainichi, bringing about a steady weakening in Chongryun’s mass basis and pretty much taking the life out of it. Koreans in Japan today, regardless of their past support for or opposition to Chongryun, face their future in Japan and the question of how to live—and die—in Japan. Many will be naturalized as Japanese citizens. Many will remain South Korean overseas nationals. But not many will call themselves overseas nationals of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. As such, zainichi, too, is faced with the possibility of being replaced with that of the new figure, the naturalized Japanese citizens with Korean heritage. Whether such a figure is able to retain his/her heritage with pride remains to be seen: the answer will hinge on the possibility of multicultural tolerance and acceptance on the part of Japanese society, resilience of Koreans in Japan, and taken together, possibility of coexistence of different peoples that were once unequivocally superior and inferior, the master and the subjugated. Edward Said wrote in the late 1970s:

The life of an Arab Palestinian in the West, particularly in America, is disheartening. There exists here an almost unanimous consensus that politically he does not exist, and when it is allowed that he does, it is either as a nuisance or as an Oriental. (Said 1978: 27)

Would a Japanese who was formerly a Korean be able to have a life that is not disheartening in the twenty-first century Japan? The question warrants future inquiry. For, 40 years later, I suspect, the life of an Arab Palestinian in the US has gotten much more precarious despite, or precisely because of, globalization. Is chōsenjin, and then, zainichi, able to be reborn as some other figure that can find a meaningful place in Japan? And can this figure still claim traces of Korea that was once colonized and erased? Or, indeed, will this figure still be interested in such an endeavor?

Acknowledgements

More than twenty years ago, I embarked on my research on Chongryun and the Korean community surrounding this organization. I thank Mark Selden and Asia-Pacific Journal for giving me the opportunity to revisit this topic. Much has changed since I first started this research in the early 1990s. I realize in retrospect that those were the last days for Chongryun‘s strength. Today, only ruins remain.

Note on romanization

In this article, I use the spelling of Chongryun denoting the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan. While its current English name is spelled Chongryon, it long used Chongryun. There exists no state-officiated Romanization/transliteration system in North Korea, and measured against the current South Korean transliteration system, neither is correct.

Related article

John Lie, The Nation (and the Family) That Failed: The Past and Future of North Koreans in Japan

References

Armstrong, Charles. 2003. The North Korean Revolution, 1945—1950. Ithaca, NY.: Cornell University Press.

“Chongryon Chief’s Son Arrested over Suspected N. Korea Mushroom Imports.” 2015. Japan Times May 12, 2015. Online (accessed March 1, 2016).

Chung, Erin. 2006. Immigration and Citizenship in Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cumings, Bruce. 1981. Origins of the Korean War, vol. 1: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945-1947. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Fujitani, Takashi. 2011. Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Inokuchi, Hiromitsu. 2000. “Korean Ethnic Schools in Occupied Japan, 1945—52.” In S. Ryang ed., Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin, London: Routledge.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. 2000. “Political Correctness, Postcoloniality and the Self-representation of ‘Koreanness’ in Japan.” In S. Ryang ed., Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin, London: Routledge.

Kim, Myungsoo. 2003. “Ethnic Stratification and Inter-Generational Differences in Japan: A Comparative Study of Korean and Japanese Status Attainment,” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 12: 6-16.

Koshiro, Yukiko. 1999. Transpacific Racisms and the U.S. Occupation of Japan. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kuraishi, Ichiro. 2008. “PACCHIGI! And GO: Representing Zainichi in Recent Cinema.” In S. Ryang and J. Lie eds., Diaspora without Homeland: Being Korean in Japan, Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Lie, John. 2008. Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): Diasporic Nationalism and Postcolonial Identity. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Morita, Yoshio. 1996. Sūjiga kataru zainichi chōsenjin no rekishi [A history of Koreans in Japan told through statistics]. Tokyo: Akashi shoten.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. 2007. Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War. Lanham, MD.: Rowman and Littlefield.

Ryang, Sonia. 1997. North Koreans in Japan: Language, Ideology, and Identity. Boulder, CO.: Westview Press.

Ryang, Sonia. 2000. “The North Korean Homeland of Koreans in Japan.” In S. Ryang ed., Korans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin, London: Routledge.

Ryang, Sonia. 2007. “The Tongue That Divided Life and Death: The 1923 Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus September 3, 2007, Vol. 5, Issue 9. Online (accessed February 14, 2016).

Ryang, Sonia. 2008a. “The De-Nationalized Have No Class: The Banishment of Japan’s Korean Minority—A Polemic,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus June 1, 2008, Vol. 6, Issue 6. Online (accessed February 14, 2106).

Ryang, Sonia. 2008b. Writing Selves in Diaspora: Ethnography of Autobiographics of Korean Women in Japan and the United States. Lanham, MD.: Lexington Books.

Ryang, Sonia. 2010. “To Be or Not to Be – In Japan and Beyond: Summing up and Sizing down Koreans in Japan,” Asia Pacific World Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 7-31.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Random House.

“Tokyo Police Raid N. Korea HQ.” 2001. BBC News Asia Pacific November 29, 2001. Online (accessed March 1, 2016).