Introduction

The “Okinawa problem” to which the APJ has paid so much attention over recent years continues to evolve, and the contradiction between the national governments of Japan and the United States on the one hand and the prefectural government and people of Okinawa on the other to intensify. The following paper was drafted by Hideki Yoshikawa and issued on May 19 in the name of the US Working Group section of the “All Okinawa Council.” The “All-Okinawa Council” is an Okinawan mass organization set up in July 2014 representing local communities, civil society groups, local assemblies, and business establishments, to press for reduction of the burden of the US military presence. It has constituted a major plank in support of Governor Onaga’s insistence that no new base be built in Okinawa for the Marine Corps.

The attached document is intended as an “Update” in the sense of being a supplement to the “Position Statement” issued in the name of the Council on the occasion of its November 2015 delegation to the US. That delegation visited US Congress and other institutions and called on the US government to cancel the Henoko base construction plan (in the north of Okinawa) and to close the US Marine Air Station Futenma in the middle of Ginowan City.

That “Position Statement” presented the case of the overwhelming majority of the Okinawan people who have shown in every conceivable way that they oppose the Henoko plan and demand the return of Futenma. It argued that the Henoko plan constituted not merely an Okinawan problem but that it involved the United States, and that US laws had been and were being infringed.1

Since that November visit, a number of significant developments have taken place, including various court-related suits and counter-suits and a March 2016 court-ordered halt to the Henoko base construction works. Even the Congressional Research Service, generally a fair, reliable, and informative source, failed to mention in its January 2016 report those judicial suits filed by the Japanese government and the Okinawan prefectural government against each other.2

Furthermore, late in April 2016 a 20-year old Okinawan woman was raped and murdered, evidently by a US base civilian employee (and former Marine) employed on Kadena Air Base. The horrendous crime shocked, saddened, and angered the Okinawan people. The All-Okinawa Council restated its demand that Henoko be abandoned and Futenma returned, and going beyond that for the first time, that the Marine Corps in its entirety be withdrawn from Okinawa (i.e., not only Futenma but also Camp Hansen, Camp Schwab, and the Northern Training Area). On 25 May, the Prefectural Assembly adopted a resolution around those same demands,3 and the majority group in the Assembly, Onaga supporting, increased its majority just days after adopting it. A 3 June 2016 newspaper poll conducted shortly after the murder incident found 52.7 per cent of people in agreement with the Assembly, and opposition to the Henoko project had grown to an unprecedented 83.8 per cent. 42.3 per cent of Okinawans favoured ending the security treaty with the US altogether, another 19.2 per cent saying it should be converted to a peace treaty.4 70 per vent of Okinawans do not support the Abe government. In other words, the Okinawan people stood even farther to the “left” on base and “alliance” matters than Onaga and their other elected representatives.

The All Okinawa Council summoned a prefectural mass meeting – the ultimate expression of democratic governance – for June 19 to press those (and several subsidiary) demands. In the presence of Governor Onaga, who till now has been a supporter of the US base presence and an opponent only in respect of Henoko and Futenma, the meeting, attended by an estimated 65,000 people, for the first time demanded total withdrawal of the Marine Corps. It constituted a formidable expression of popular will.5

And beyond that already seriously escalated demand, for the first time demands that exceed those of the Council, and that call for closure and return of all US bases in Okinawa (including the giant US Air Force base at Kadena), began to be heard. On the day after the latest brutal attack on an Okinawan citizen by an American base employee, representatives of 18 Okinawan women’s groups met and agreed that there could be no “security,” especially no security for the women of Okinawa, otherwise.6Former Governor, the now 91-year old Ota Masahide, commonly respected as a voice of Okinawan conscience, took the same view.

|

A protestor holds up a sign demanding that U.S. military leave Okinawa during a June 19, 2016 rally in Naha, the capital of Okinawa. AMES KIMBER/STARS AND STRIPES |

Whatever the outcome in the short term, the Meeting would undoubtedly serve as a fresh index of the absolute opposition between national and prefectural governments. The two national governments, Japan and the United States, would watch with growing nervousness as the Okinawan movement, till very recently concentrated on opposition to a new base at Henoko, gradually expands, widening from Henoko and Futenma to include all Marine facilities and then to include all bases. While Prime Minister Abe kept insisting to the US government that Henoko would be built (it was the “only” solution), the more unlikely it became. Instead, the entire US military presence in Okinawa was coming under question.

Meanwhile, on June 18, the “Central and Local Government Disputes Resolution Council,” which had been deliberating in response to the court-ordered “conciliation” of March, announced that it would not issue any ruling other than to urge the parties, the national and prefectural governments, to resolve their own differences.7 There seemed little, even zero, prospect of that.

The text of the May 2016 “Update,” lightly edited, follows.

GMcC

The Update

Lawsuits and Court Intervention

As we predicted (in the All-Okinawa Council’s Position Statement) Okinawa governor Onaga Takeshi’s October 2015 revocation of the land reclamation approval for the construction of the U.S. military base, granted in December 2013 by his predecessor, led to a series of suits and counter-suits between the Okinawa Prefectural Government and the Japanese Government.

On November 17, 2015, the Japanese government filed a suit under the Administrative Appeals Act against the Okinawa prefectural government in the Naha Brach of the Fukuoka High Court.8 The Japanese government insisted that since there were no legal flaws in the previous governor’s approval the revocation by Governor Onaga was illegal and the Okinawa Defense Bureau was entitled under the Administrative Appeals Act to seek redress. The Japanese government also sought reclamation “execution by proxy.”

On December, 25, the Okinawa prefectural government countered by filing a suit against the Japanese government in the same court.9 It insisted that the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLITT)’s suspension of Onaga’s revocation was illegal, since there were indeed legal flaws in the previous governor’s approval process and since the Administrative Appeals Act, under which the suspension decision had been made, was designed to offer recourse to private individuals, not to government or government agencies.10 The prefectural government’s filing of the case came one day after the Central and Local Government Disputes Management Council, a supposedly independent review body, refused to take up the complaint by the Okinawa prefectural government against the suspension of Onaga’s revocation.

On January 29, 2016, Judge Tamiya Toshio, presiding over the two lawsuits, made an unexpected move. Expressing his concerns over such an unprecedented exchange of lawsuits between the central government and a local government, Judge Tamiya advised both sides to consider an out-of-court settlement. He offered two alternative plans.11

Both sides showed initial reluctance, but on March 4, 2016 they agreed to accept what was commonly referred to as the Provisional Plan.12 Under it, both withdrew their court cases, the Okinawa Defense Bureau immediately halted construction works (drilling surveys and preparatory works on Camp Schwab), and the parties expressed readiness to enter discussions towards achieving a satisfactory resolution (enman kaiketsu) pending outcome of a judicial determination.

However, it quickly became clear that both sides had agreed to the out-of-court settlement for their own reasons: they had no expectation of a mutually satisfactory resolution This was vividly manifested when, just three days after both sides accepted the provisional plan, the Japanese government sent a “rectification order” to the Okinawa prefectural government, and claimed it was “prescribed in the settlement details” as precondition.13 Governor Onaga expressed his regret and criticized the government for issuing such an order so soon after the settlement. He insisted that settlement involved talks, not orders.14 The Japanese government continues to maintain that the Henoko plan is the only choice while the Okinawa prefectural government insists that the Henoko plan is not an option it could accept.

The acceptance of the out-of-court settlement plan by the Japanese government and the Okinawa prefectural government prompted many different interpretations. Some argued that the Japanese government accepted the plan only because it was worried about the effect of the lawsuits on the upcoming elections for prefectural assembly and National Diet Upper House.15 Others argued that Governor Onaga feared that the anti-construction camp, consisting of various political parties and citizens with different political views on the U.S. military, could not be held together if the lawsuits were prolonged. Still others, including the U.S. Section of the All-Okinawa Council, took the view that the Japanese government, and probably the court itself, would not want all details of legal flaws to be discussed in court, but would be likely to rule in the end in favor of the Japanese government (as in numerous prior cases).

Meanwhile, U.S. President Barack Obama expressed his concern over the delay16 while the Japanese government insisted that it was “doing its utmost to realize the plan.”17

Under the agreement, if the two sides fail to resolve their differences, the Naha branch of the Fukuoka High Court would then be called on to deliver a ruling. Whichever side loses the case would then appeal to the Supreme Court.18 It is generally thought that its final verdict would favor the central government.

Even with such a Supreme Court “final verdict,” however, there are many other legal options for Governor Onaga to stop the Henoko construction plan. Governor Onaga has said that, in case the outcome of the settlement was not acceptable to Okinawa prefecture, he would consider the option of “repealing” the land reclamation approval.19 Repeal is one of the two legal forms available for rescinding the land reclamation approval. Such an option can be utilized when flaws are found after the approval. So far, Governor Onaga has used the other form, cancelation, on the grounds that there were flaws in the approval process.

Judge Tamiya’s statement calling for an out-of-court settlement point to the possibilities of further legal and procedural battles between the Okinawa prefectural government and the Japanese government. He said, in part,

“Even if the state wins the present judicial action, hereafter it may be foreseen that the reclamation license might be rescinded (revoked) or that approval of changes accompanying modification of the design would become necessary, and that the courtroom struggle would continue indefinitely. Even then there could be no guarantee that it would be successful. In such a case, as the Governor’s wide discretionary powers come to be recognized, the risk of defeat is high.”20

Thus it is imperative that the U.S. government (executive, legislative and judicial branches) pay close attention to the Japanese court’s intervention and consider its implications, since the U.S. government is itself deeply involved in the construction plan and bears a responsibility under U.S. laws.

Construction, Protest, the U.N. Human Rights Council, Site Entrance Permits

While the lawsuits were underway, the Japanese government continued underwater drilling surveys in Henoko and Oura Bay and preparatory works on the ground of Camp Schwab for the construction of a new base. In response, protesters continued their activities in the forms of sit-ins on land and canoe and boat protest at sea. Confrontation escalated between protesters and police and the Japan Coast Guard and the authorities used force against the protesters. The international community, including the U.N. Human Rights Council, now pays close attention to this.

During the period from November 17, 2015 to March 4, 2016, or from the time the Japanese government filed its first lawsuit against the Okinawa prefectural government to the time both parties accepted the out-of-court court settlement, arrests and detention of protesters, and some injuries, were reported.21

Okinawan NGOs submitted a report on this confrontation to the 31st General Assembly of the Human Rights Council in February 2016.22 It said,

“The police forcefully evacuate and detain them on the sidewalk of the U.S. military Camp Schwab gate in Henoko, where they are kept inside an enclosure of iron bars and police vehicles. At sea, in addition to detention and evacuation, protesters and journalists in kayaks and small boats have been subject to violent measures by the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) such as colliding with and damaging their boats and deliberately flipping (overturning) smaller boats. The JCG has used excessive force, including chokeholds and holding demonstrators underwater to threaten them with drowning. The police and JCG have taken video footage of protesters and journalists, identified and threatened them by name.”

Over recent years, at NGO request, the U.N. Human Rights Council has been engaging in “communication” with the Japanese government, inquiring about the Japanese its “excessive use of force, harassment, arbitrary arrests of peaceful protesters in Okinawa.”23 The Japanese government has maintained that the Okinawa prefectural police and the Japan Coast Guard “have taken legitimate and necessary measures in the light of duties of the police organizations, namely, protecting people’s life, body and property and maintaining public safety and order.”24

At a press conference held in Tokyo in April 2016, David Kaye, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression, expressed concern in his “preliminary observations.” He referred to “public protest in particular in Okinawa with the Coast Guard,” “allegations of disproportionate restrictions on protest activity in Okinawa,” “credible reports of excessive use of force and multiple arrests.”25

Meanwhile, it should be pointed out, as discussed in our Position Statement, the Japanese government has been able to carry out drilling surveys and construction work in the area of Henoko and Oura Bay only because the U.S. military issues entrance permits to the Okinawa Defense Bureau according to the U.S. and Japan Status of Forces Agreement. During the period in which the court cases were still in process, the U.S. military continued to issue entrance permits, contributing to the exacerbation of the situation. Given that the U.S. Congressional Research Service’s reports on the Henoko base construction have constantly warned against “heavy-handed actions by Tokyo and Washington” to protesters,26 now that the Japanese Court has intervened to halt the construction works the decision made by the U.S. military in Japan to keep issuing entrance permits needs to be reviewed.

It is imperative that the U.S. military take into consideration the implications of issuing entrance permits to the Okinawa Defense Bureau in light of the U.N. Human Rights Council’s concerns of violation of the rights to freedom of opinion and expression as well as in light of the current out-of-court settlement and possible future litigation between the Okinawa Prefectural government and the Japanese government.

The Dugong and U.S. Responsibility – A New Document

There has been an important development in terms of information on the status of the dugong, an endangered marine mammal and Japan’s Natural Monument, inhabiting the area of Henoko and Oura Bay, the site of the Henoko base construction. On March 23, 2016, through a persistent inquiry by the Office of National Diet House Representative Akamine Seiken, the Okinawa Defense Bureau (ODB) finally (and probably reluctantly) released the Schwab (H25) suiiki seibutsu to chosa houkokusho Schwab [(H25) Survey on Aquatic Organisms Report] (hereafter the Schwab (H25) report).27 It presents the results of the ODB’s surveys on aquatic organisms in the area of Henoko and Oura Bay and its vicinity conducted between November 2013 and March 2015. The information on the dugong in the report challenges the conclusions of the ODB’s controversial Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) that the area of Henoko is rarely used by the dugong, and thus the construction of a military base in Henoko will have no adverse effects on the dugong and the base can be built in that area. This conclusion is the legal/procedural and scientific foundation for the Henoko construction plan.

|

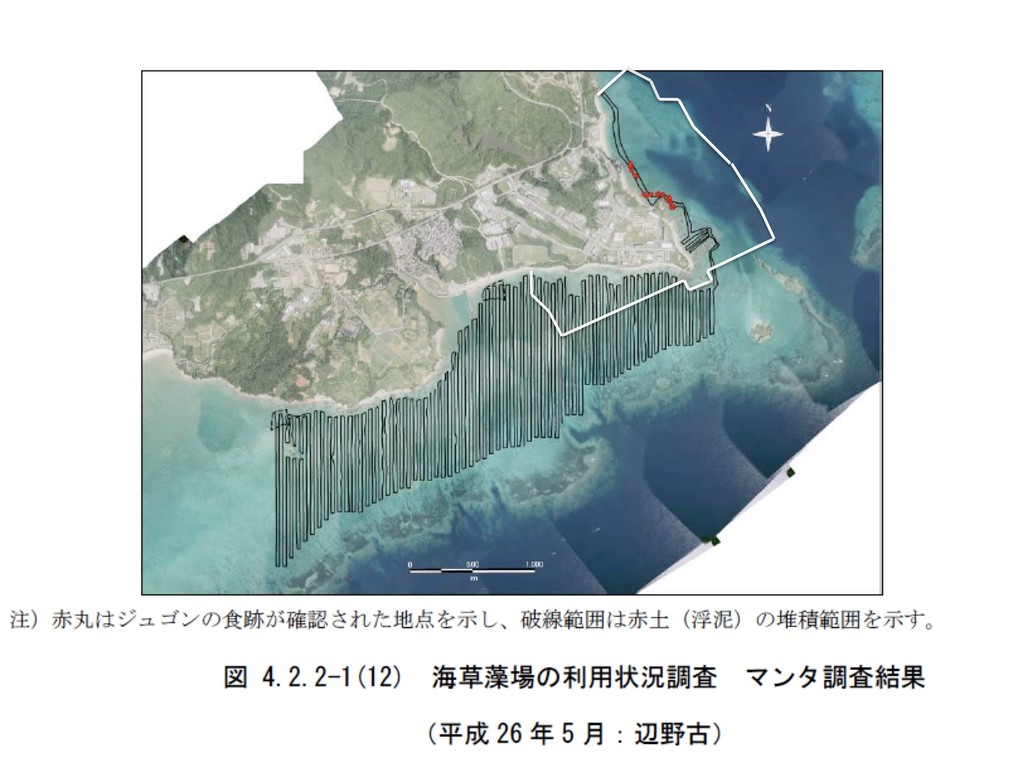

Note: Dugong feeding trails (in red) confirmed at the construction site as of May 2014. Broken lines indicate soil run-off in polluted area. Image taken from the Okinawa Defense Bureau’s “Schwab (H25) report.” Superimposed white line indicates the new base. |

The Schwab (H25) Report shows that between April and July 2014 the ODB found 77 dugong feeding trails in the seagrass beds directly on the base construction site.28 This supplements similar survey results presented by NGOs in August 2014 that between May and July 2014 NGOs had found more than 110 dugong feeding trails in the Henoko area.29 These numbers are in stark contrast to the OBD’s EIA surveys in which the Bureau did not find any dugong trails in the same area, and so cast doubt on the EIA conclusion. The OBD’s own survey results could serve to support the long held argument by NGOs, the Okinawa prefectural government and many others, that the construction site is an important feeding ground for present and future Okinawa dugong.

In fact, with this new information, it can be pointed out that, over the 16 years between fiscal year 1998 and 2014, the number of years in which dugong feeding trails were found in the area of Henoko was three times higher than the number of fiscal years in which such trails were not found (2004, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011). These “absent years,” except for fiscal 2004, correspond to the years in which the OBD used lots of heavy survey equipment including passive sonar system and underwater video cameras to conduct its “preliminary surveys” and EIA surveys. NGOs and Nago City have argued that these preliminary surveys in fact scared dugong away from Henoko and Oura Bay.30

The Schwab (H25) report shows that, between August 2014, a month after the ODB started drilling surveys in the area, and March 2016, the ODB could not find any dugong feeding trails in the area. The implication is that drilling surveys most likely impacted and altered the feeding behavior of the dugong.31

Despite this new evidence on dugong feeding trails, there is no discussion in the Schwab (H25) report on the EIA conclusion and on differences among the survey years in terms of presence and absence of dugong feeding trails. Instead, in a meeting with NGOs, OBD officials said that the Bureau maintains its original conclusion as set out in the EIA, that dugong rarely use the Henoko area but do use the Kayo area, meaning that the construction of a military base in Henoko and Oura Bay would have no adverse effect on them.32 The OBD also refrained from answering questions regarding possible effects of drilling surveys on the feeding behavior of the dugong.

It is still unclear whether any experts supported the OBD’s adherence to the EIA conclusion. Since the Schwab (H25) report was released in March 2015 (not becoming publicly available until March 2016), the ODB has not submitted the Schwab (H25) report to the Environment Monitoring Committee, which was set up by the OBD to advise on natural conservation in the process of building the base.

The Schwab (H25) report also shows that the Okinawa Defense Bureau continued its awkward practice of area categorization regarding dugong sighted in aerial surveys. As with its EIA, the Schwab (H25) report refers to dugong sighted in the Oura Bay area as being found in the Kayo area. Its analyses refer only to Henoko, Kayo, and Kori, and has no Oura Bay category. This practice of area categorization distortedly represents the area of Kayo and Oura Bay as distinctive and separate. In fact, Henoko and Oura Bay constitute together a single, large ecological area, and the construction of the planned base is generally regarded as taking place in it. The distinctive categorization falsely supports the ODB’s claim that the dugong uses the Kayo area but not Henoko.

The ODB has refrained from commenting on why the OBD continues this awkward practice of categorization, instead insisting that the OBD is taking the utmost care.33

In light of the OBD’s release of the Schwab (H25) report, the U.S. military has to provide explanation and accept its own responsibility. In particular, it has to address its own review and assessment of the Schwab (H25) report. According to the Akamine Seiken office, the Japanese Ministry of Defense submitted the new report to the U.S. military at a meeting held in June 2015. That means that the U.S. military had the Schwab (H25) report nine months before it became available to the general public and to the OBD’s Environment Observation Committee.

The U.S. military stated in its U.S. Marine Corps Recommended Findings April 2014 that:34

“Construction activities will occur over multiple years and the USMC feels that it is prudent to request and review monitoring information collected by the GoJ during construction and initial operations. Should the GoJ’s monitoring of the area during construction reveal the regular presence of the dugong in Henoko Bay, the USMC will consult with GoJ and adaptively manage its operations to minimize any adverse effects on Okinawa dugongs.”

It is not clear whether the U.S. military reviewed the Schwab (H25) report or consulted with the Japanese government since there is no information available regarding the U.S. military’s review and assessment of the report. However, the fact that the U.S. military continued to issue entrance permits to the OBD for the construction of the base between June 2015 and March 2016 points to the possibility that the U.S. military had also concluded that the new survey results did not change its stance on the impact of the base construction on the dugong. It is imperative now that the U.S. military follow its procedural steps stipulated in the Findings and makes available to the public the details of its review and assessment.

Ginowan City Mayoral Election

In January, 2016, an important mayoral election was held in Ginowan City where the U.S. Marine Corps. Futenma Air Station is located. One of the critical issues was the closure of Futenma Air Station. The incumbent Mayor Sakima Atsushi, backed by the Abe Administration, easily defeated Shimura Keiichiro who was supported by the opponents of the Henoko Construction plan including Okinawa Governor Onaga Takeshi.

The election was depicted as a proxy battle between the Japanese government that is proceeding with the Henoko plan and the Okinawa prefectural government that opposes it.35 Thus, the result of the election was welcomed by the Abe administration. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga went further, challenging the notion that All-Okinawa opposed the construction plan.36 Aiko Shimajiri, an LDP Upper House member from Okinawa, asserted that a “silent majority” had spoken in the election.

Among the residents of Ginowan City, however, the Sakima victory has not been regarded as signifying approval for the Henoko construction plan.37 During the election, Sakima refrained from taking a clear position on the Henoko construction plan. Rather he emphasized his campaign pledge to have operations of the Futema Air Station halted within 5 years. Moreover, exit polls conducted by Asahi shimbun and Mainichi shimbun showed that 57% of the voters opposed the Henoko construction plan. And Mainichi also showed that 55% were very critical of the Abe administration’s handling of the issue of the Futenma Air Station.

Above all, the result of the Ginowan mayoral election confirms a peculiar pattern in local elections in Okinawa: Tokyo backed candidates can win in mayoral, gubernatorial, and National Diet elections when they avoid taking a clear stance in favour of Henoko construction plans, but when they make a clear stance in favour of it they lose, as with the case of Nakaima in the 2014 governor’s election and Suematsu in the 2014 Nago Mayoral election.

It remains to be seen whether this pattern will continue or not in upcoming elections of prefectural assembly and National Upper House in June and July 2016.

Developments in the U.S.: City Council Resolutions and Appeals Court

There have been two important developments in the U.S. regarding the Henoko construction plan.

First, following in the footsteps of the City Council of Berkeley, California, the City Council of Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 25, 2015, adopted a resolution calling upon the U.S. government to take responsibility.38 It resolved that “the U.S. Department of Defense undertakes an appropriate and sufficient “take into account” process as ordered by the Court under the National Historical Preservation Act” and that “Congressional hearings take up environmental issues in the Henoko plan.”

These requests of the policy order resolution by the Cambridge City Council are basically the same as the demands of the All-Okinawa Council’s Position Statement. It is anticipated that similar steps will be taken by other city councils in the U.S.

Second, the plaintiffs of the “dugong lawsuit” are now appealing in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, insisting that the DoD failed to comply with the NHPA. In particular, they are challenging the district court’s ruling that the plaintiffs lack standing to bring their NHPA claim and that the political question doctrine bars the court from accepting the plaintiffs’ request for relief because, even though construction is under way, any harm to the dugong can still be redressed.

It is our understanding that, in a few months, the 9th circuit will appoint judges and set a date for a court hearing. It is also our understanding that the appeals court will be provided with information on developments in Japan discussed above, in particular the Japanese court-mediated halt to construction work and the new information on the dugong.

Our Demands

The All-Okinawa Council’s “Position Statement” had a section that outlined our demands to the U.S. government. Our demands have yet to be met with adequate and substantive response. We call upon the U.S government to respond to our demands. In particular, we are disappointed that the DoD has to date not undertaken an appropriate and sufficient “take into account” process as required by the National Historical Preservation Act and that Congressional hearings on the Henoko construction plan so far have not involved any representatives from Okinawa able to represent the views of Okinawa’s overwhelming majority opposed to the Henoko plan.

We acknowledge and appreciate the positions held by the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission and the Advisory Council on Historical Preservation as they wait for sufficient information to decide on their next step. We are preparing information for these two agencies.

We believe that the developments discussed in this paper have created a situation in which the U.S. government can and should take appropriate action.

The US Section Working Group, All-Okinawa Council, May 18, 2016.

Notes

Hideki Yoshikawa, “All Okinawa Goes to Washington – The Okinawan Appeal to the American Government and People,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 47, No. 3, December 7, 2015.

Emma Chanlett-Avery and Ian E. Rinehart, “The U.S. military presence In Okinawa and the Futenma Base Controversy,” CRS Report, January 20, 2016.

“Zen kichi tekkyo 4 wari cho,” Ryukyu shimpo, June 3, 2016, and for a slightly abridged English translation, “Over 40 per cent of Okinawans want bases withdrawn and 53 per cent want Marines withdrawn,” ibid, June 3 2016.

“Okinawa kenmin taikai 6 man 5 sen nin, higaisha itami kaiheitai tekkyo yokyu,” Okinawa taimusu, June 19, 2016.

See Press Conference by the Minster of Defense Gen Nakatami, November 18, 2015. See also “Court battle over Henoko,” Japan Times, November 18, 2015.

See “Okinawa sues Tokyo over Futenma relocation dispute, taking legal battle to next level,” Japan Times, December 25, 2016.

See Governor Onaga’s statement (in Japanese only) on filing suit against the Japanese government December 25, 2015.

For detailed discussion (and translation) of Judge Tamiya’s out-of-court settlement proposal see Gavan McCormack, “ Ceasefire’ on Oura Bay: The March 2016 Japan-Okinawa ‘Amicable Agreement’ Introduction and Six Views from within the Okinawan Anti-Base Movement,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 7, No. 1, April 1, 2016.

“Obama concerned over possible delay in Okinawa base relocation,” Mainichi Shimbun, April 1, 2016.

“Gov’t officials puzzled by Okinawa Governor Onaga’s remarks over Futenma base transfer,” Mainichi Shimbun, April 7, 2016.

“Onaga says he could ‘repeal’ land fill approval over Futenma base transfer,” Mainichi Shimbun, April 6, 2016.

For detailed discussion on Judge Tamiya’s out-of-court settlement proposal as well as translation of the proposal, see Gavan McCormack’s article “ Ceasefire’ on Oura Bay: The March 2016 Japan-Okinawa ‘Amicable Agreement’ Introduction and Six Views from within the Okinawan Anti-Base Movement,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 7, No. 1, April 1, 2016.

Joint Statement by Shimin Gaiko Centre (Citizens’ Diplomatic Centre for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR).

See “Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders,” letter sent by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to the Japanese government, June 15, 2015.

See “Reply of the Government of Japan to the request for information through the communication of the Speical Rapporteurs of the United Nations Human Rights Council.” July 27, 2015.

David Kaye, press conference, “Preliminary observations by the United Nations special rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Mr David Kaye at the end of his visit to Japan (12-19 April, 2016),” April 19, 2016.

Emma Chanlett-Avery and Ian E. Rinehart, The U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa and the Futenma Base Controversy,” CRS Report, January 20, 2016.

See Schwab (H25) suiiki seibutsu to chosa houkokusho [Schwab (H25) Survey on Aquiatic Organisms Report].

According to the Schwab (H25) report, in April, during a total of 7 days survey per, the ODB found 13 new dugong trails; In May, during a total of 4 days research, the ODB found 28 new dugong trails; In June, during a total of 4 days research period, the OBD found 28 new dugong feeding trails; In July, during a period of 4 days research periods, the OBD found 8 new dugong feeding trails.

See the NACS-J’s survey reports and press release on the finding of dugong feeding trails in May and July, 2014.

See the NACS-J’s survey reports and press release on the finding of dugong feeding trails in May and July, 2014.

U.S. Marine Corps Recommended Findings April 2014 is here provided as EXHIBIT 1 to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, San Francisco Division.

Eric Johnston, “In proxy battle over Futenma base relocation, Ginowan mayor wins re-election,” Japan Times, January 24, 2016, and Gavan McCormack, “The Ginowan Mayoral – Okinawan Currents and Counter-Currents,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, February 1, 2016.

Peter Ennis, “Local Election Fails to Break Stalemate over US Marine Presence in Okinawa,” Tokyo Business Today, February 4, 2016.