Introduction and Translation by Masako Tsubuku

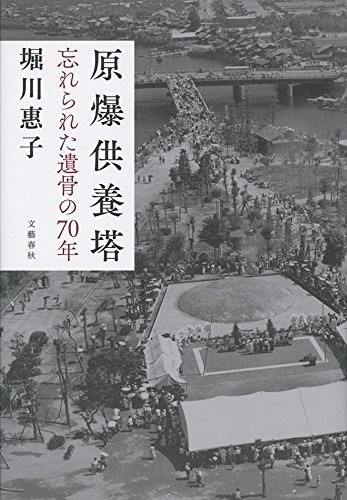

In May 2016 freelance journalist Horikawa Keiko received a special award from the Japan National Press Club for her book, “Genbaku Kuyoto,” which is about victims of the Hiroshima atomic bombing whose remains have been identified but not claimed. Of the five books she has published, not counting one she co-authored, four are about capital punishment. As she explains during the following press conference for “Genbaku Kuyoto,” she feels capital punishment and the bombing of Hiroshima are thematically related. Though she worked for years as a TV journalist in Hiroshima and covered stories about the bombing many times, it wasn’t until she researched Japan’s death penalty that she made a connection and realized how little she knew about what happened on August 6, 1945.

One of the goals of her research was to find out how the number of official dead was determined. To her, the number is important, because each life has meaning. To lose track of that number is to lose the meaning of that event. The only way she can bring them back to life is to show how a few of them lived. MT

|

The following press conference (abbreviated here) took place on Aug. 4, 2015 at the Japan National Press Club in Tokyo

This is how I wrote my book.

I used to work for Hiroshima TV, which is part of the Nippon TV network. I worked there for 12 years before I quit. In my 11th year there I was transferred to a desk. Those around me probably thought I was being promoted rather quickly, so it should have been a positive thing, but in that position I didn’t have the chance to go out in the field and do stories. All I did was check other reporters’ work and plan future stories. I did that for a year and I couldn’t stand it, so I thought of quitting, even though I had no prospects, no connections.

But I quit anyway. Living in Hiroshima I wondered if it was the best place to work, so I moved to Tokyo at the end of 2004. I was hoping there would be something there for me. For two years I just studied the system in Tokyo. It wasn’t as if suddenly I was a freelance reporter. After leaving the TV station I worked for a production company on an exclusive contract. My main work was to produce TV programs, but during that time I also wrote books.

In 2005, the 60th anniversary of the surrender, I made a TV program about Hiroshima for NHK: “Chinchin Densha Jogakusei,” about female students who drove street cars [in the city during the war]. I had already covered this topic when I was working at Hiroshima TV, and then supplemented that research and made a book out of it.

But what I really wanted to cover was capital punishment. Why am I talking about this now? Everything I talk about is connected. The issue of Hiroshima is at the root of my interest. Whatever I do it is all related to the same thing in my mind. So this book, “Hiroshima Memorial,” is just one facet of this life work.

When I was working at Hiroshima TV, there was one project I could never carry out. It was impossible. In 1998, Asahi Shimbun’s front page had a story about executions, which I think had taken place that day in Tokyo, Sapporo, and Hiroshima. In fact, Hiroshima Prison is located in the center of the city, about 3 minutes from the main shopping area. Next to the prison there is a high school and a college for women. It was there that the execution took place. When I found that out I was deeply shocked.

Without knowing anything else I just wanted to cover this story–who was involved and what the process was. What happened behind those walls? But no one I talked to knew anything. I couldn’t get anything; or maybe I should say they wouldn’t talk to me. I didn’t even know where to look for anyone who did know about it. Of course, I called the justice ministry and they wouldn’t talk to me. Then I talked to my supervisor, and he wouldn’t even let me cover it. “Capital punishment is a media taboo,” he said. “Such an issue can’t be covered by commercial TV.”

But I couldn’t let it go. Now I can say, there shouldn’t be any taboos when it comes to reporting the news. If a reporter can’t cover a story due to a taboo, then the country is on the road to totalitarianism. I formed that opinion long ago and decided I would devote my efforts to capital punishment. I started at the end of 2007. Then in 2014 I published the book, “Prison Chaplain.” It took 7 years. In the meantime I made several programs for NHK and wrote other books on the subject.

While I worked on the capital punishment story, I was reminded how precious life is. I had to face the truth of capital punishment, that there are people being killed, people who do the killing, and people who decide to do the killing. Then there are the people on the side: the families of the victims, the families of the convicted. In my books I haven’t talked much about victims’ families. I interviewed them but I didn’t write about them, and that’s intentional. During all these interviews, I felt the weight of it all. When a life is taken away, as a writer I cannot bear the responsibility, so I always had a hard time doing the writing.

But it’s easy to imagine. Think of your mother or father being killed, or someone you love killing someone else, the weight of that. It’s not just an intellectual thing, but a spiritual thing. You feel it in your gut.

Then I realized that the victims of the Hiroshima bombing…from August to September, some 140,000 people died, give or take 10,000. Just think about that. The weight of one life is so great, and then you think that this enormous number is off by 10,000 lives. I just couldn’t process that. So I realized there was a task I neglected when I lived in Hiroshima. In 2012 that feeling became overwhelming, and so I returned.

Strangely enough, when you’re working on several different projects at the same time you find connections. Then I gained confidence, thinking that this Hiroshima story could be successful.

At that time I was researching “Prison Chaplain,” and one of the chaplains I interviewed was a hibakusha. He suffered because he escaped death without helping other victims. He carries that guilt with him to this day. In his work, he faces death all the time and has to attend executions. At that point I realized I had to go back to Hiroshima.

But I had no plans to make a TV program or write a book on this theme. Let me digress. When I quit my job at Hiroshima TV the best thing that happened was that I was free from deadlines and the restricting framework of broadcast journalism. Those aspects have nothing to do with the import of your topic, they are only there for the convenience of the people who are producing the news. They are put in place by the organization. They have no bearing on the truth, and, in fact, are often obstacles to uncovering the truth. Without those restrictions, I could see the topic clearly and knew exactly what I wanted to do with it.

Even now, I’m working on several projects at once. I’m not sure which one will develop into something worth exploring further. I cover something because I want to know about it. That’s my incentive. My method of operation.

So when we say “give or take 10,000 lives”–that’s what drives me to find out more. And the first thing that came to mind was that in 2004, when I quit my job, I wanted to cover the Memorial. So in July I went to Ninoshima Island, about 20 minutes from Hiroshima harbor by ferry. South of Ninoshima is Itajima Island. My purpose in going there was that I heard they were exhuming bodies. The atom bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, and the harbor is about 5 km from the epicenter. Thousands of bodies were buried on Ninoshima and are still being dug up today. In the summer of 2004 they were carrying out the fourth series of exhumations.

Another reason I went was sentimental: I was leaving and thought I should properly confront the dead. However, what I felt there was very different from what I expected. It wasn’t sentimental. It was much more profound.

Digging up bones is a very delicate process. The bones are entangled in the roots of trees. It was everywhere. Removing the bones was extremely difficult because the roots were so thick. The workers did all they could to retain the integrity of the bones, but they would just turn to dust. It was very unpleasant to watch, as if the bones were resisting their exhumation.

In my book I described this scene as if the dead were reacting with anger. While I worked at Hiroshima TV I produced more than 100 segments about the bombing, but mainly they were about survivors. Or they were scoops–finding survivors who no one had talked to before. And that was an important job, but at the time I’d always write the figure “140,000” without thinking twice about it. So now I thought: Was I being sincere about all those people who died? It wasn’t until I came to the end of my time in Hiroshima that this occurred to me. The experience left a bad taste in my mouth, and I remembered that taste in 2012.

Hiroshima is very sensitive to the seasons: It’s customary to talk about the bombing at a certain time of the year. A related activity is taking out the list of the dead from storage, just to air it out. There is a list of people whose remains have been identified, with names and addresses, but which no one has claimed. The idea of airing the list is to get surviving relatives to come and claim them. The list is posted, and media companies cover it without comment. I covered it myself, every year.

So why has no one claimed these remains, despite the fact that their names and addresses are available? When I was working for Hiroshima TV it never occurred to me to locate the families of these people, usually because I was very busy. I didn’t have the presence of mind to think about it. All I did was search for scoops.

In 2012 I had a better idea of what I wanted to do and hit on this project, which would be to confront the dead. It’s easy to say, but in practice it was very difficult.

I started to research the names on the list. I knew it would be hard, because the dead don’t speak. I had been covering capital punishment, which no one tends to cover because it’s difficult to get all the facts, but I did and that gave me the idea that I could tackle this new project.

How many people here have ever been to the Genba Kuyoto [Atom Bomb Memorial]? [Only her editor; people laugh uncomfortably] Oh, one other person. Yes, that’s how it is. It’s not the Ireihi [Peace Memorial], which everyone knows. One hundred and twenty meters north of the Ireihi is the Genba Kuyoto. Local people call it Domanju [the mound]. It looks like a kofun [burial mound] covered in vegetation. Inside the mound is a chamber. From the north side you can enter and descend by a stairway. Until recently it was locked, but in that chamber the remains are stored. The number of individuals represented by the remains is about 70,000. That’s what the documents say. I knew that number when I was working in Hiroshima, and of those 70,000, 816 have names and addresses. Due to my research, however, the number has since been reduced to 815.

So these 815 people have names and addresses. Some also have photos in their boxes, and information about where they worked. This data is included on the list of remains. In 2012 I decided to find out who they were.

What that means is that I was going to enter somebody’s private life, with my shoes on, and then reveal those lives to the world. In the process I was hoping I could reunite these remains with their families, and that eased my conscience to a certain extent.

Then I started traveling with this list. Originally, I thought I could get the backgrounds of a few of the names on the list in maybe six months. Then I would write about the people whose lives I uncovered, how they died, and why they were there at that particular time. Also, I would find out why their families didn’t receive their remains for 70 years.

But I didn’t get anything. Half a year later, nothing, and I thought: Why am I doing this? Everyday, I’d go to an address on the list and there is no trace of that address. Maybe it’s on a small island, like the one I describe in the first chapter. I believed I could find it because the address was so detailed, but it was on an island and nothing had changed there for 70 years. I went and there was no such number. When I mentioned to neighbors the name of the person I was looking for, none of them had ever heard of the person. They said very definitely that no person with that name ever lived there. I went to the local temple, which keeps records of all the residents going way back in time, including all the names of the people who had died in the area, but no such name was in their records. I even went to the Diet Library in Tokyo and checked all the old telephone books, and still nothing. The person just didn’t exist, but the list said that person died in Hiroshima.

Another address was in a remote mountain village. I went to the address and found a place with that number, so I thought I was getting somewhere. But it turned out the person who lived there had a different name. The name of the person on the list was Furutani. There was no trace of such a person at that address. Then a neighbor told me that nearby there was a family whose daughter did not return after the war, so I thought, maybe in the confusion someone’s name had been mistakenly included on the list. Other errors were easier to determine.

One was an attorney named Baba. His body was found in Shinsenba-cho in Hiroshima, an address that no longer exists. I thought it would be easy to locate, especially since he was a lawyer. There were about 5,000 lawyers in the prefecture at that time, so I started checking every one. But of all the lawyers practicing in Hiroshima in 1944, there was no one named Baba. Then I checked all the Babas in the records, but all their relatives said no one in their family had died in the bombing.

I expanded my search to surrounding prefectures, and still couldn’t find an attorney named Baba. Shinseba-cho is located near the courthouse. I had an old map and there were likely many law offices in the area, not to mention inns and other accommodations. In that area, many buildings had been demolished beforehand on purpose [to eliminate possible air raid targets], but the courthouse and the law offices were not destroyed, because they were important to the workings of the city. Still, I couldn’t find the name Baba.

Then I returned to Tokyo and looked through the records of the justice ministry, which I had used many times before. In 1945 there were four people named Baba. Three years later, according to documents, there were only three. So that means one of them had either died or had left the bar. As I said earlier, this kind of research is the equivalent of invading someone’s privacy. You are pressing against a wave of rejection. The bar association was never going to give me the information I wanted. All I could do was keep asking. But through my research into capital punishment, the bar association knew me, and had asked me in the past to participate in symposia [against capital punishment]. But they wouldn’t give me information about Baba. I thought it was unfair. I was frustrated and angry, but I kept pushing.

And gradually, I received information one bit at a time. I found out that on August 20, 1945, someone named Baba was removed from the bar association’s list of lawyers. So he either had died or quit being a lawyer. He was 39 at the time, which is too young to retire, so I assumed he was the person I was looking for. I can’t publicly reveal the source, but I found out about his background and how he came to Tokyo. I got his home address, which is on the Kunisaki Peninsula, in Oita Prefecture. I assumed he came from Oita to Tokyo to attend Chuo University, and graduated from that university’s night school program. He passed the bar exam when he was 24, a prodigy.

So why was he in Hiroshima on that day? My imagination was running away with me. Maybe he was on his way home from Tokyo, riding the ferry from Hiroshima to Kunisaki through the Bungo Channel. So I checked all the routes that anyone could possibly take at the time from Tokyo to Kunisaki, as well as all the passenger lists, and narrowed it down to certain possibilities. One thing I didn’t mention in the book: There was a lawyer from Hiroshima who attended the same night school at the same time. Maybe Baba had stayed with him in Hiroshima, or at an inn. With that notion I went to Oita and finally located a distant relative who told me he died in Tokyo, but that no one had ever confirmed his death. They had just received a notification that he had been killed in an air raid while hiding in a shelter. His remains were sent home and placed in the family graveyard. That’s strange, because all the documents I found indicated he had died in Hiroshima.

Finally, I came to the conclusion that maybe the list was wrong. I thought if I worked hard enough I could eventually reach the families of the people on the list. The other day a reporter from the Yomiuri interviewed me, and I got the feeling he thought I was either naive or making a big deal out of this one name for the sake of my book. Of course, a smart person would have been skeptical from the beginning. Someone who had never been to Hiroshima seemed to understand what a chaotic scene it must have been at the time. To tell you the truth, I was a bit offended.

So in my innocence I had been running around aimlessly, and then finally realized the list was all wrong. I should have stopped investigating then and there, but I had a very powerful accomplice. That person was described in the first half of the book. She will be 96 years old this December: Saeki Toshiko, a hibakusha.

“Go to the Memorial. You’ll see Saeki-san.” That was something you always heard among the reporters in Hiroshima. She was 26 when the bomb dropped, and her memory of that day is still clear. Twenty-one members of her family died in the explosion. She looked all over Hiroshima for them, for days. Since she couldn’t recognize them among all the wounded–they were so badly burnt–she would touch their legs and make them scream in pain in order to hear their voices. If it was a loved one, she’d recognize the voice. Faces bloated, hair singed, eyes gone, lips swollen, skin sloughing off. Naked. Only the voices remained recognizable. She finally received her mother’s remains, but it was only her head, the face burned and her glasses still attached. Only a few strands of hair left.

Saeki-san regretted what she had done to the other victims, so after the war she went to the Memorial every day to pray for the people who were unclaimed. If the bus wasn’t running for whatever reason, she’d walk. Without fail. Ten kilometers. She would clean the memorials and give them water and go back home. At that time there were no restrictions. Anyone could enter the chamber, so if you wanted to pray, you could go inside. Saeki-san was even given a key by the authorities so she could come and go at her leisure.

Keep in mind, this is before the list of unclaimed remains was made. Saeki-san would open a container and find a paper with a name and address, and she wondered why the family didn’t come to claim the remains. She checked all the containers and wrote down all the names if she found a piece of paper inside. Then she would cross check the names with the available documents and made her own list of unclaimed remains. And then she would look for the families.

This is 1961-62. While she was doing that, society in general started wondering why Hiroshima City wasn’t doing something, so eventually the city forbade her from entering the Memorial. They took her key away, saying, “We didn’t ask you to do this…” And then they finally started doing their own investigation and came up with the list of unclaimed remains.

I met Saeki-san many times when I was working at Hiroshima TV. At the time, she was famous in Hiroshima. Sometimes she gave lectures to students visiting the city on school outings, or interviews on TV or in newspapers. When I was there, all I cared about was getting scoops, and she gave me valuable information, but she was covered by everyone, so she was never a subject of my reports. But I talked to her a lot just for information.

So after that half-year of chasing false leads I finally thought of her and contacted her. In 1988 she had suffered a stroke. She was quite frail and I visited her in a nursing home and started working with her on this book. I explained to her what I was doing and said that maybe the list of unclaimed remains was incorrect. I couldn’t find addresses, etc. Usually, she’s very cheerful, but suddenly she became silent, as if she were angry. She said in a very harsh tone, “It would be very strange if that list was correct.” How could it be, considering the circumstances that brought it into being? There’s no way it could be right. She was essentially telling me I was being perverse because I believed in it from the beginning. It was as if I’d been struck on the head. In the chaos of the bomb, survivors made mistakes or forgot something. People who are dying desperately want to be with their families, but people who make lists are alive and have different priorities. That’s when I understood. If you are making a list you have to get the correct information using every little bit of information in order to return these remains to their families. So I was doubly determined to continue my work with the help of Saeki-san. Even if I could only find the survivors of ten people on that list, I should try.

I had thought that everyone killed on that day was from Hiroshima, but later learned that people from other places were also victims. On the list was a woman named Tanaka from Wakayama who worked for the Red Cross Hospital. I thought it was strange that such a large organization couldn’t find her family, so I went to the Red Cross in Wakayama and found that the Tanaka who worked for the Red Cross did not die in Hiroshima. Before she really did die several years ago, she talked to a colleague, who told me that Tanaka-san knew her name had been mistakenly placed on the list of Hiroshima victims. She knew why the mixup had taken place. She was a nurse in Rangoon, and at that time the Red Cross HQ was in Hiroshima, in Ujina Harbor. When she departed for Rangoon, she left from Ujina and on that day used a public toilet. She left her bag outside the stall and when she came out the bag was gone. Inside the bag was her underwear with her name and address printed on it. The bomb was dropped 2 years later. Obviously, one of the victims had been wearing her underwear.

Tanaka Mitsue herself had a terrible experience in Rangoon and empathized with the people killed in the war, so she told her colleague, “If I said publicly that the person on the list was not me, it would reflect badly on the dead, because it would imply that person was a thief.” So the only person she told was her best friend. Because I found this out, they removed her name from the list.

The names on the list have full addresses, so I went to one of them, this time armed with skepticism. The neighborhood was called Narioka. Only ten people lived there, and all the names are in the public record. They showed me the list of residents who lived there during the war. The name of the person on the list of unclaimed remains was Yamamoto, but the current residents said that no one by that name had ever lived there. So, again, I thought I was chasing a false lead, but another neighbor told me of a nearby neighborhood of mostly Koreans. About ten kids from that community went to the local school. So the person who died in Hiroshima might have been Korean. The address was clear, so in the end we figured out the person had come from the Korean peninsula. Of course, this person had changed their name to a Japanese name in accordance with the law at that time. As I said before, the number of victims is said to be 140,000, give or take 10,000. That number, however, did not include people from Korea. That was the first time I became aware of that, and the Koreans numbered anywhere from 5,000 to 50,000. I’m pretty sure the number of Koreans who died in Hiroshima was in the tens of thousands. Officially, they weren’t included in the number of victims.

Also, there were people from Okinawa among the remains. An editor at Bungei Shunju who worked with me on this book told me where to go to find out about Okinawa and the military. That publisher is famous for looking frankly at Japanese history. I can’t say here where he suggested I go, but you probably know the place I’m talking about. I found out that Okinawans were forced to evacuate in 1944 by order of the government. Tens of thousands went to Hiroshima.

The remains of one particular person belonged to a soldier who had been drafted and sent to Hiroshima. I met his surviving family, who were trying to decide whether or not to accept his remains.

As of Aug. 6, 1945, the population of Hiroshima was increasing at a rapid rate. From what I could confirm records reported that the population was close to 300,000. But maybe it was closer to 400,000. The reason is that soldiers from all over Japan left for the Pacific and Asian fronts from Ujina Harbor. It is said that 3.1 million Japanese died during the Pacific War, but more than two-thirds of that number perished in the final year of the war. More and more people were being drafted and mobilized, and they all came through Hiroshima. The ages varied widely, from boys to older reserves. The problem is there were not enough boats to transport them, so they were just in the city, waiting. And then the bomb was dropped.

After Saipan was captured by the Americans, B-29s just kept destroying all the transport ships as soon as they left Japan. The headquarters of the Second Army had been moved to Hiroshima in April 1945, near Hiroshima Station, so the military population of Hiroshima just kept getting bigger. What were those soldiers doing there? They were quartered in schools, just waiting. There were not enough barracks at military facilities. During the day they trained on school grounds. The defense of Honshu had become the overriding military consideration.

They began destroying buildings in the city in order to reduce the number of possible bombing targets, and as a result residents were being evacuated, but in actuality the population was increasing because of the military changes. Of the 815 remains on the list, many were from places outside of Hiroshima.

As I said before, when I worked for Hiroshima TV my main task was getting scoops, looking for stories that no one had covered yet. But I became aware that some stories that had already been reported were incomplete, that they went deeper than the coverage they had received. Reporters who made their careers in Hiroshima always centered on the “end of the war,” which in Hiroshima means Aug. 6. Local reporters always focus on that day. I started looking at Hiroshima’s history starting in the Meiji Period, in the context of Japanese history and all the events of the war before that. You have to talk about all those things when you write about the atomic bombing. It had a great effect on me as a journalist.

But it was a dilemma. There were suddenly too many things I wanted to cover and had to cover.

This book was published at the end of May. When you finish writing a book, it doesn’t mean you’re done with it. I need readers. In July I started receiving reactions. Some people asked me for help looking for their relatives. I realized my work wasn’t finished.

In addition, the Memorial was opened to the public for the first time in 20 years, and covered by NHK for the first time in 10 years. That made me angry. Local media covered and analyzed it. They all featured the same narration or content, which said that Hiroshima City is opening it to the public in order to find the relatives of the victims interred therein, and while that isn’t necessarily untrue, as a journalist who has covered this subject for a number of years I felt it was hypocritical. After all, it was the city which forbade Saeki-san from carrying out her own research to find those families and took away her key. And at the beginning of my coverage Saeki-san told me it was useless to go to the city office, because they wouldn’t answer me seriously. They’d just tell you not to do what you’re doing. I told her that wasting time is actually part of a journalist’s job in getting information. So I went to City Hall and, yes, she was right, they just shut the door in my face. Over and over they just kept saying it was an invasion of privacy. Dead people have privacy. Surviving families have privacy. That’s what they kept saying. “Why are you trying to dig up all this?” Their reaction was unbelievable.

But through my research new information came out, including the number of victims on the list. Gradually, my findings intrigued them and they became more interested in what I was doing. If I found something that should have remained secret, they would accept it because they had the resources to confirm it. Finally, I reached the stage where I could have free interactions with city officials on this matter.

After I published the book, I deliberately didn’t apply to City Hall to disclose the list to the public, because after people read my book I wanted them to demand the list be disclosed, but it didn’t happen, because reporters these days don’t read books. My editor told me we have to apply ourselves in order to disclose the list publicly. Actually, I’m the one who has to apply, but my editor talked to a variety of people who made applications. At first, city hall refused. Then my editor sent a plea directly to the mayor along with reviews of the book. So the mayor ordered his staff to reconsider my request, and they disclosed the list.

I will continue working on this project with city hall, but other media realized the door was open and so they rushed to do their own reports. They interviewed city staff, who said they wanted to show it all to the public. Those media didn’t question these remarks, didn’t reveal what had taken place behind the scenes. A dozen media companies, and they were all the same. It made me see that journalism had become impotent. If any of those reporters had read my book, even a few pages, they wouldn’t have covered the list the way they did. Saeki-san is still alive and resides in Hiroshima. If they interviewed her they’d discover the real significance of the list.

I don’t want to bash city hall. I just want the media to understand what happened and report it in their own words. They didn’t. Since publishing my book, Hiroshima City treats me very differently. I’m like a VIP. Any time they have new information they call me. It’s quite a change.

Due to the mayor’s intercession, the list and the memorial is now open to the public. But it’s not finished, because if you go into the chamber and see all those urns, you will definitely feel something. They are the seeds for future coverage.

Just yesterday I received a letter from a person in Kumamoto saying that their father was exposed to the atomic bomb close to the epicenter, and his remains are still missing. The person’s nephew is also missing. They never knew that remains were interred in that memorial. Maybe that person’s father is there. They didn’t even know of the existence of the memorial.

The person went there last July, but the door to the memorial was locked. They went to the archives and asked staff about it, but they didn’t respond. On the way home, they found my book in the train station and that’s when they found out their father’s remains might be there and contacted me.

The last thing I want to say is that I understand the city’s position that the memorial is a sacred place. That suggests the remains are divine. But they aren’t divine. They are the remains of people who were killed and who still have families. By making them divine, they effectively make them untouchable. Moreover, they don’t even publicize that such a place exists within the Peace Park. Is that acceptable?

If surviving families want these remains back, the city is obliged to respond. It’s not like tourists dropping in and demanding the chamber be open. There aren’t that many surviving families left. Seventy years is a long time, and there are fewer and fewer surviving family members. When those families die off, it’s impossible to trace the lives of the people who died in the bombing. If there are survivors left, the city should allow them to come and pay respects in the chamber whenever they want.

The fact that we are still talking about this 70 years after the fact means the postwar period is still with us. So I will continue reporting on these matters.

-Question and answer session

Q: Of the 800 or so names on the list, how many have you investigated so far?

Saeki-san looked for the families of ten people. I told you about one person, the nurse, that I investigated myself. I found families of two other people and wrote about them in the book. I also found two other families but didn’t write about them. So five altogether for me. I plan to write more about this in the future. Whenever I go to Hiroshima I continue doing research on the remains.

While working on this project, I constantly feel the weight of these 140,000 victims. The counting of the dead was not done responsibly. It’s very approximate. The number they came up with doesn’t mean they counted everyone who died. And having the remains of 70,000 people doesn’t mean they actually have the remains of that number of people. They simply calculated how many people were in Hiroshima on the day and then subtracted the number of survivors. The number of soldiers killed was 20,000. Based on all this they arrived at a number.

After the war several media outlets and the authorities announced the number of people who died in the bombing, and that number has always changed. On August 25, 1945, it was 63,613, according to Hiroshima Prefecture. Three months later it was 92,133, including missing people. Those are local police figures. In Aug. 1946, it was 122,338, according to the city. In 1949, the city reported 210,000 to 240,000 had died. In 1951, the US and Japan collaboratively estimated the number to be 64,000, which was eventually adopted by the UN. In 1953, Hiroshima city said the number was 200,000, and in 1961 that it was 119,000 to 133,000, according to the Japan Society Against Atomic Weapons. In addition, Hiroshima prefecture says 200,000. Newspapers tend to report 250,000.

Why such a wide discrepancy? The reason is that whoever is counting is not counting the number of deaths. When I walk through the Peace Park, I often hear tour guides say, “Hiroshima City lost all family registers in the bombing,” but actually all the family registers survived the bombing because the documents were sent out of the city when people were evacuated.

So after the war when they started investigating who was missing, there shouldn’t have been that much of a difference. When they tried to get an accurate number, they started by counting the dead, in 1969. The number of people who they are certain died in the bombing is 88,978. They have the names and addresses of all those people. And every few years they revise this number after more research. So if you subtract 90,000 from 140,000, it leaves 50,000. The unclaimed remains in the tower amount to about 70,000, so this number remains the issue’s most ambiguous factor.

What I want to emphasize is that the number of Japanese deaths during the war was 3.1 million. If you think of the number who died in Hiroshima you can see how uncertain those numbers are. The media repeats the 3.1 million figure without qualification, and I really wonder. I think they should check that number further.

Q: Did you do any research into boy soldiers?

When I was doing my research, I kept asking myself, who made this list of 815 remains with names and addresses? Originally, the remains represented 2,200 individuals, all with names and addresses. Who compiled that list? I asked Hiroshima City and they said that after the war neighborhood associations submitted lists of names. That’s all. Now I always hear people say, “At that time, the soldiers who were collecting and burning the bodies were very young, just boys.” The Army School for Boys was in Hiroshima. They wore badges on their uniform. They were a kind of elite. The story was always made to sound so beautiful, and I believed it.

Then I looked into it and found out that the school had moved out of the city in April, three months earlier, along with all the students, except for a handful who were stationed in the city and perished in the bombing. But there was the Akatsuki Corps, which belonged to the Naval Command. They were teenage officer candidates, but actually secret troops. I found out these boys were being prepared for suicide missions. As it happens, a book was just published about them. We talked earlier about Itajima, which was a base for elite officer candidates during the war. Now it’s a base for the Marine Self-Defense Force. North of Itajima was a secret base. Locals didn’t know anything about it, but there are two small plaques there. Eventually, I found records saying that between 2,000 and 2,500 boy soldiers, between the ages of 16 and 19, from all over Japan were there about to ship out. They were secret troops, which is why they were isolated. About 1,800 had already left. They manned these vinyl crafts with car engines, and all I presume died on suicide missions. They were the first phase. The second and third phase students were still there when the bomb dropped.

After the bomb was dropped, the Naval Command sent out an order to these boys at 11 a.m. to enter the city and help survivors. I found a copy of that order. By 2 p.m. they were already in the city. Their first task was to rescue survivors, but people were just dying on a continuous basis. The next day they started collecting and processing the dead. Members of this group are now living all over Japan. They told me they were supposed to record all the information about the remains they collected. They were given lined forms to write down this data. Before they burned a body, they had to record the name of the person as printed on the name tag everyone was required to sew into their clothing.

Of course, in accordance with Saeki-san’s dictum, it’s strange if that information was correct. For instance, one former boy soldier I interviewed was from Aomori. He didn’t know anything about Hiroshima before he arrived. When he asked a dying person their name, he didn’t always understand because of the local dialect, and so the name he wrote down was probably wrong. After they burned the bodies they buried them. On the 14th that task was taken over by the city.

Later, the mayor of Hiroshima said in recorded minutes at a city assembly meeting that there is a list of 60,000 names recorded by these boy soldiers. It doesn’t mean they had all the remains, only that there was a list of 60,000 names. So we have those names thanks to the military system, which is quite disciplined. This came out through my research.

Q: As you said earlier, the US counted 64,000 dead at one point. In your research, did you notice American and Japanese political influence regarding this matter?

Yes, I did. America’s influence was clear, though I didn’t discuss it in the book. Right after the war there was a press code in place. I don’t need to tell you this, but there was a crackdown on any antiwar movement in the city. You couldn’t write about hibakusha either. The anti-nuclear weapons movement didn’t start until 1954. The press code was in effect until 1952.

More than 100,000 people were killed in the explosion, but in years after that tens of thousands of people were dying from the effects of radiation. You can see those records. But no newspaper ever covered it. Then the Americans arrived in Hiroshima and came up with the number 64,000. It seemed to have something to do with Auschwitz. They wanted to minimize the number, and the Japanese media closed its eyes, ears, and mouths. The damage caused by the bomb was hardly covered at all here. In the immediate postwar period it wasn’t mentioned at all. But then in 1954 with the Daigo Fukuryu maru (Lucky Dragon # 5) incident [in which Japanese fisherman were irradiated during the US hydrogen bomb test at Bikini] the modern antiwar movement started. The previous period is called the “empty ten years.” I wrote about it in the September issue of Bungakkai. I wanted to see if those years were really empty, but some things were written. There was some testimony, it’s just that newspapers didn’t cover it and there was hardly any TV at the time. “Empty” in this case means empty in the organized media. In that way, America tried to minimize the damage.

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, which was controlled by the Pentagon, was collecting detailed data about the victims. Fukushima Kukijiro’s book of photographs showed this period vividly. ABCC collected data but they didn’t treat anyone, because they wanted to see what radiation really did to the body. The media was toothless during this time, and America tried to minimize damage to its reputation while collecting lots of detailed data about radiation. Look at Hiroshima City. The main road is named after MacArthur. And there was a tennis tournament called the MacArthur Cup. Citizens were still having a hard time [after the war], and the tennis courts were gorgeous. But that’s a different story. Suffice to say there were many contradictions.

Q: Going back to the boy soldiers, are there any survivors?

There will be a reunion in September at Itajima. I think ten people will attend. Including those who can’t attend there are 20 or 30 still alive, with an average age of 92. I neglected to say anything earlier, but those boy soldiers running around Hiroshima after the bomb dropped, many became sick and died without explanation. If they were in Hiroshima City when they died, they were classified as hibakusha, but if they got sick after they returned home, they weren’t. The symptoms were often the same as those for radiation sickness, but the cause of death was invariably recorded as “unknown.” These are on the record. Several hundred died that way in their hometowns.

Q: I’ve read some of your books and am always impressed by how thorough your research is.. I’m sure that when you’re doing research you’re thinking about the end product–the TV program or the book. You submerge yourself in the research but sometimes you have to come up for air. How do you approach the end product? How do you find outlets?

While I’m doing the research, I think I can take it to a publisher or a broadcaster when I find a way of making the message concise. If I’m not clear about the message of the story, even if I get good interviews, it’s going to take too long. When I can summarize the message without images, then I know I can finish the work. I gain confidence. But that’s only happened in the last five years.

What keeps me going, even when the research isn’t going well, is anger. When it comes to war and capital punishment, the line separating perpetrators and victims isn’t always so clear, though most people think it is. I know that line isn’t clear, and I always feel anger because of it. I want somehow to channel that anger into a concise message. At that point I have confidence in what I’m doing, no matter what others may say about the work. Then I look for a means of putting it out. Television is difficult, because the kind of things I do don’t always come across visually. But some production companies let me go ahead and do what I want. They may not understand what I’m doing but they let me do it. “We’ll give you this much time, so go ahead.” I just wait for those opportunities. The biggest reason I started writing books was so that I could cover the death penalty, since TV was never going to be interested. And if no publisher showed any interest I would have self-published.

Of course, I have to make a living, so self-publishing isn’t something I could do all the time, but at least there would be a record out there. When I get writers block or don’t know what I’m doing, I’ll see a small item in a newspaper or magazine, and it opens something into the future. In the same way, I want to leave something behind. I always feel that way. My first book, “Death Penalty Standards,” was turned down by several publishers. One publisher finally accepted it for publication but the print run was small. It received the Kodansha Non-Fiction Award, which gave me a certain level of certification in the eyes of the publishing business. Winning an award opened up new possibilities. They could trust me. So now when I think I have a book, I can talk to publishers. They’re willing to listen.