At the January 2014 World Economic Forum in Davos, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō stumbled on the world stage when he warned of the dangers of complacency regarding the possibility of conflict between China and Japan, drawing a parallel between the UK and Germany on the eve of World War I when European diplomats were ‘sleepwalking’ into the abyss. The media suggested it was a warmongering speech, based apparently on a misleading translation. Abe’s spin-doctors were fuming at the damaging misinterpretation, but given that Abe made a pilgrimage to the Yasukuni Shrine only three weeks earlier on 26 December 2013, it is understandable that the press was primed to assume the worst. This is because Yasukuni is widely viewed as ‘ground zero’ for an unrepentant, glorifying narrative of Japan’s wartime rampage in the years 1931-45. While Beijing and Seoul’s criticism of Abe’sisit to the shrine was anticipated, Washington’s swift and sharp rebuke was not.

|

Prime Minister Abe at the Yasukuni Shrine 2013 |

Abe probably thought he would get a pass from Washington, despite extensive behind the scenes lobbying warning him not to go to the shrine, including a phone call from Vice President Joseph Biden. This is because he had just closed a deal with then governor of Okinawa Nakaima Hirokazu to proceed with plans to build a bitterly contested new Marine airbase in Ōura Bay, Henoko in exchange for a little over $20 billion in aid spread out over eight years. The base is important to the Pentagon and Abe appeared to deliver on security what his predecessors could not. But he and his advisors misread Washington on history issues and paid the price.

Champagne corks were no doubt popping in Beijing and Seoul celebrating Abe’s ‘own goal’ at Yasukuni and media drubbing at Davos. There was also a war of words conducted in op-eds in Europe and the US as usually dignified diplomats exchanged insults and invective, even invoking Harry Potter characters to vilify their counterparts. In The Telegraph (1/1/2013), for example, the Chinese ambassador to the UK wrote: ‘If militarism is like the haunting Voldemort of Japan, the Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo is a kind of Horcrux, representing the darkest parts of that nation’s soul.’ The Japanese ambassador replied in the same tabloid, “East Asia is now at a crossroads. There are two paths open to China. One is to seek dialogue, and abide by the rule of law. The other is to play the role of Voldemort in the region by letting loose the evil of an arms race and escalation of tensions…” (The Telegraph, 1/5/2014)

In January 2014, Ambassador Caroline Kennedy opened the bilateral rift further by tweeting critically about Japan’s dolphin hunt. Japan seemed to be on its back foot and thus the decision at the Angouleme International Comics Festival in southwestern France to feature a South Korean entry critical of Japan’s comfort women system reinforced perceptions that, on the global stage, Tokyo was losing the war of words with its bitter rivals.

When Obama visited Tokyo in the spring of 2014, Abe was still in the doghouse as Obama pointedly brought up the comfort women issue. Obama said that it is a crucial issue, one that he knows the Japanese public understands and one that he thinks Abe gets, following this up with further pointed comments in Seoul that could only be interpreted as critical of Abe. Indeed, Abe has spent his political career trying to trash the 1993 Kono Statement acknowledging state responsibility for coercive recruitment of comfort women, sparking a furor in 2007 when he quibbled about the degree of coercion used in recruiting the women who were used as sex slaves on Japanese military bases around the region. Washington nudged Abe way beyond his comfort zone when he concluded a diplomatic agreement with Seoul at the end of 2015 regarding the comfort women issue that paved the way for a meeting with Presidents Park Geun-hye and Barack Obama in Washington at the Nuclear Security Summit in March 2016. The agreement is unlikely to resolve the inescapable comfort women issues that roil bilateral relations and inflame public perceptions, but for Abe it was a big stretch. This helps explain why in early 2016 he announced his resolve to revise the Constitution as a way to appease supporters who were dismayed by what they view as Abe’s apostasy on the sex slave controversy.

|

The ROK-Japan Agreement on the Comfort Women requires Seoul to remove this statue in front of the Japanese Embassy, but the South Korea public opposes this and activists maintain a 24/7 vigil. |

Despite these setbacks, Team Abe runs an impressive PR operation in Japan, managing the media quite effectively, limiting access, orchestrating press conferences and ensuring that Abe is not put in a position where he has to improvise, make unprepared remarks or answer awkward questions. But the ways and means that work in Japan don’t necessarily work in the global arena. Access for international correspondents working in Tokyo is the bait that the prime minister’s office dangles in exchange for favorable coverage. It is a cat-and-mouse game because the journalists don’t want to appear craven and Team Abe is intent on squeezing out as many concessions as possible, such as magazine covers and puff pieces.

|

Back in 2013 when there was a buzz about Abenomics. |

It’s not always pretty, but that is how the game gets played. NY Times correspondent Martin Fackler told me that MOFA tried to get him to write a letter of apology in 2009 for his predecessor’s reporting about comfort women, threatening not to give him an interview with Abe if he refused to comply. He refused, never did get that interview, and asserts this is a counterproductive strategy because it denies the government a chance to get its side of the story out there. And feuding with the NY Times does not seem an inspired policy to win influence in the US.

This article focuses on the Sino-Japanese rivalry as it plays out in the U.S., considered by both nations to be one of the key battlegrounds where the stakes are high in influencing policies and attitudes.

Japan Lobby and Alliance Management

All governments manage the media and every administration has a few spin-doctors to massage the message. Tactics may vary, but governments hope to sway public opinion in their favor. Key to understanding this lobbying process in US-Japan relations is the role of US think tanks and American Japan hands who work as alliance managers and thus have a stake in the outcome and act accordingly in concert with Japanese counterparts, especially on security issues, but more generally as well. For example, the Trans Pacific Partnership is ostensibly about economic issues, but PM Abe’s decision to join was predicated on a geo-strategic assessment that doing so would strengthen the U.S. security alliance and counter China’s growing influence in the region. Abe has delivered more than all of his predecessors combined on Washington’s longstanding wish list on security matters ranging from bases in Okinawa to easing constitutional constraints on Japan’s military forces, underscoring that the alliance is a subordinate relationship in which Americans dictate the terms. Ironically, in Abe the U.S. has a willing accomplice who frequently calls for overturning the postwar order that his neo-nationalist constituency disparages as an unwelcome humiliation imposed by the U.S. to keep Japan weak, dependent and subordinate.

PM Abe Shinzo is seen by Washington’s security wonks as their man in Japan, so his strengthening of the alliance seems to be a key achievement in bolstering ties. This development involved considerable back stage maneuvering and extensive communication about a range of security issues through various channels. The Japan Lobby has evolved from an organization focused on trade issues to one that is funding and guiding public diplomacy regarding China, especially over security and history issues. In the 21st century Japan has found itself at cross-purposes with global perceptions about war memory, especially the comfort women issue, but China’s regional hegemonic ambitions under President Xi Jinping have facilitated an upgrading of US security cooperation with allies and partners in Asia, including Japan.

|

For example, in April 2015 Japan signed new US-Japan Defense Guidelines, the first since 1997, which greatly expand what Japan is theoretically prepared to do militarily in support of the U.S. in the event it is attacked. In September 2015, despite overwhelming public opposition, PM Abe rammed enabling legislation through the Diet that eases significantly constitutional constraints on Japan’s military forces and allows their dispatch anywhere in the world in the name of collective self-defense. Abe repeatedly reassured the Japanese public that his security laws won’t really have much of an impact while in Washington he promised they would be a game-changer, a rhetorical maneuver that sowed dissatisfaction on both sides of the Pacific. While the Japanese public expresses concern that the Abe Doctrine will endanger Japan because Tokyo may eventually be dragged into conflict at America’s behest, Washington ‘alliance managers’ are quietly disappointed that after all the smoke cleared it appears that what Japan will be able to deliver is a lot less than they thought Abe committed to.

|

Protestors in August 2015 opposing Abe’s Security Legislation portray him as a US Puppet. |

In trying to woo domestic and foreign support-both government and public-the media is only one battlefield in the larger war of public diplomacy, but a crucial one. Back in the 1980s when bilateral tensions between Japan and the US were high due to trade imbalances, Tokyo engaged professional lobbyists in Washington to woo Congressional and media opinion. This is how the game is played, but in that febrile atmosphere Pat Choate’s Agents of Influence (1988) struck a chord. The Japanese government was playing by established rules, but in Choate’s book it was portrayed as suborning the system while those who lobbied on Japan’s behalf were depicted as betraying their nation and abetting “the enemy”. Those were the days when a cascade of ‘revisionist’ tomes hit the bookshelves, reassessing the US-Japan relationship, dismissing the more benign views toward Japan that prevailed, and arguing that Japan had an advantage because it was not playing by the same rules and the government was managing not only markets, but also trying to manipulate American public opinion. (Johnson 1982, Prestowitz 1988, Fallows 1990 & 1995, and von Wolferen 1989) The Cold War bargain of sacrificing US economic interests to help Japan become a showcase of the superiority of the American system, and a stalwart ally hosting bases that allowed Washington to project its military might in Asia, was seen to be unsustainable and no longer justified.

Hard as it is to imagine today, Japan was portrayed as the relentless juggernaut that would stop at nothing to prevail and establish a Pax Nipponica. There was even a multi-episode BBC documentary of that title, conjuring up warmed over ‘yellow peril’ nightmares, reinforced rather emphatically by Ishihara Shintaro (1989) in his infamous The Japan That Can Say No. This polemic threatened, inter alia, to withhold key semiconductor parts from the US military industry that would weaken its capabilities and advocated that Tokyo cozy up to Moscow. However, Ishihara’s gambit was ill timed as the Soviet Union was already unraveling and in its death throes.

Back in 1987, NY Times journalist Clyde Farnsworth drew back the veil on Japan’s lobbying efforts in Washington where nations around the world seek to buy influence and shape policy outcomes. Farnsworth (1987) wrote,

“The Japanese, according to Congressional aides, spent more than $60 million last year for direct representation to improve their image and try to keep doors ajar in their biggest market. That’s four times the level in 1984. Japan’s interests have become increasingly intertwined with America’s, not only because the United States consumes about a fifth of Japan’s total production, but also because the Japanese investment here has mushroomed.”

|

Robert Angel (1996) further detailed Japan’s lobbying efforts, providing an insider’s perspective as he headed the Japan Economic Institute between 1977-84, an organization in Washington that played a key role in the Japan Lobby. He discounted the more alarmist portrayal of the Japan Lobby as exerting a “pernicious influence”, but detailed the hydra-headed effort in a manner that left no doubt about the extent of its activities and the unusual public/private cooperative nature of the enterprise:

“By Japan Lobby I mean Japan’s governmental and private sector efforts to influence the policy formulation and implementation processes of the United States through unofficial, non-diplomatic means. My definition of the Japan Lobby includes institutional and individual participants in both Japan and the United States. They share responsibility for target analysis, planning, and implementation. But all important decisions are made in Japan, and Japan supplies nearly all of the funding. Japan Lobby participants on the Japanese side include government ministries and agencies, quasigovernmental and private-sector organizations, business corporations and organizations, academic institutions and their cooperative faculty, Japan’s version of think-tanks, publishers, public relations firms, and even political parties and the personal offices of well-financed politicians. In addition, Japan Lobby managers have established several foundations that channel amazingly generous funding to Lobby participants who would find it uncomfortable to receive such funds directly from the Japanese government.”

Angel asserted that every ministry was involved in disseminating the government line domestically and internationally while corporate public relations departments and various foundations provided valuable support. The Japanese foundations, he argued, provide funds to experts and institutions that have a high degree of credibility with the US public precisely because it was assumed that the opinions and assessments they espoused were untainted by financial inducements. The funding was thus channeled in ways that don’t impugn the independence and credibility of the beneficiaries. He alleged that the Japan Foundation established in 1972 under the aegis of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was the first and has been one of the most influential of these institutions, a key component of the Japan Lobby infrastructure. Aside from these efforts to sway public discourse, Angel wrote that, “the Japan Lobby has found a way to support the political campaigns of elected officials without violating the law through announcements of intentions to invest in employment generating projects.”

|

In Bamboozled (Routledge 2002), Ivan Hall also draws attention to the unwitting and opportunistic dupes of Tokyo and the various ways that the Japanese government manages bilateral relations by influencing American perceptions. This is not exclusively a government effort, but Hall argues that it orchestrates non-government and quasi-government foundations, and media coverage, to incentivize positive assessments and coverage while deliberately sidelining awkward issues and critical observers. This shaping of bilateral discourse, what he terms the ‘mutual understanding industry’, has been a critical factor in facilitating closer ties and highlighting common ground and ostensibly shared values.

The shared values nostrum emphasizes democracy and civil liberties such as freedom of the press, requiring a degree of cognitive dissonance on both sides of the Pacific in light of the marginalization of Okinawan democratically expressed preference in discussions about strong opposition to the siting of U.S. bases in the prefecture and Team Abe’s orchestrated ouster of prominent television anchors and commentators critical of the prime minister. (Kingston 2015a,b; Kingston 2016.) In my opinion, “The talismanic invocation of shared values provides an ideological foundation for pursuing common interests as defined by Washington. Shared values might best be understood as the mood music for getting Japan to dance to America’s tune, while making it seem that it is really only taking a principled stand based on its own ideals. Japanese leaders understand that as a client state, it is in Japan’s interest to take its cue about common interests from the United States.” (Kingston 2015c)

Rising China

From the late 1990s there has been growing anxiety about “Japan passing”, a fear that the US is seeking closer relations with China, encapsulated in the G2 concept, at Japan’s expense. The phenomenon of Japan passing stemmed from President Bill Clinton’s nine-day visit to China in 1998, when he did not stop by Japan and consult with America’s major ally in Asia. At the time, a growing trade deficit undermined bilateral relations and led to what Tokyo referred to as ‘Japan bashing’, a term meant to dismiss any criticism of Japan.

In the 21st century, there is concern in Tokyo that growing US-China ties might undermine the security alliance, leaving Japan isolated in a dangerous and hostile neighborhood. At the extreme, Tokyo worries that the US won’t come to its aid in a territorial conflict with China because it doesn’t want to risk its economic interests. The rapid rise of China as an economic and military power has transformed the geopolitical landscape in East Asia in ways that Japan finds threatening; double-digit annual growth in China’s defense spending, now treble Japan’s military budget, a more assertive foreign policy regarding regional territorial disputes and unresolved grievances with Tokyo over history have had significant repercussions.

Japan should be reassured by public opinion polls in the US that indicate a deep reservoir of goodwill, as 74% of Americans in 2015 express a favorable view of Japan. In contrast, this 2015 Pew Poll found that American attitudes toward China remain negative with 54% expressing an unfavorable view and 38% holding a positive view. (Pew 2015) Back in 2005, 43% were favorable to China while only 35% were unfavorable and thereafter until 2011 favorable views (51%) exceeded unfavorable views (36%). Since 2012, however, a majority of Americans have expressed negative views of China, a time when a rupture in Sino-Japanese relations developed over Tokyo’s nationalization of the Senkaku Islands. There is no reason to believe, however, that Japan’s public diplomacy has had any role in this sharp negative swing in American opinion towards China. As Tokyo vies for influence and tries to nurture closer ties, it is benefitting from China’s clumsy diplomacy and ‘radar rattling’ maritime forays. According to Pew, negative American views are driven by the large amount of US debt held by China, cyber attacks, trade deficits, Beijing’s growing military power, perceptions that a rising China is causing a loss of US jobs, in addition to human rights and environmental issues. The US media has been quite critical of China over a range of issues and in the US Republican presidential campaign, Donald Trump has engaged in China bashing, although he has also tagged Japan for free riding on the US military and suggested it along with South Korea develop its own nuclear weapons.

|

Republican Presidential Candidate Donald Trump Slams China and Japan. |

In addition, the Obama Administration has adopted a neo-containment policy toward China in a bid to counter its regional hegemonic ambitions. The Obama pivot to Asia, or rebalancing, has involved upgrading defense ties in the region, including Japan, Australia, the Philippines and India, and tapping into regional concerns about what a rising China portends. This is the context in which the US promoted TPP and opposed Beijing’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB); only Japan among close US allies stood with Washington by refusing to join China’s 2015 AIIB initiative. The goodwill generated by Hu Jintao’s earlier smile diplomacy has evaporated to Tokyo’s advantage. Xi Jinping’s maladroit diplomacy and muscle flexing has stoked an Arc of Anxiety in Asia that has undermined its interests and helped Japan overcome its own inept forays in public diplomacy. Its no exaggeration to say that Japan’s most effective strategy is to let China alienate American public opinion all by itself.

Public Diplomacy Battles

In Asia in Washington, Kent Calder (2014) calls Washington, D.C. the world’s, “preeminent agenda setting center.” This is because of the outsized power of the US and the concentration of international organizations, foundations, think tanks and non-government and non-profit organizations involved in trying to shape policies and attitudes render Washington a crucial battleground for Asian governments. Asia’s pivot to Washington aims to influence US policies, counter rivals’ similar efforts and nurture warmer relations at the expense of rivals.

|

Calder, Director of the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at SAIS/Johns Hopkins University in Washington, concludes that the heyday of Asian lobbying is past, “So formal lobbying on behalf of Asian interests, while quite intense in the 1970s and 1980s, appears to have been epiphenomenal and to have waned substantially over the past two decades, just as the pace of classical Washington lobbying itself appears to have done.” (Calder 2014: 131) Apart from Japan, the two most determined Asian lobbyists in Washington are China/Taiwan, each claiming to represent China, and South Korea. Their lobbying has generated a competitive battle over territorial and historical memory issues that Calder thinks Tokyo is losing. Drawing attention to what he describes as Beijing’s more aggressive, extensive and successful lobbying efforts Calder writes,

“To a greater degree than most foreign nations, China represents its interests in Washington by working through local American organizations with similar concerns, rather than directly. U.S.-China relations also involve a host of other semiofficial support organizations, including the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations (NCUSCR), the China Institute, the U.S.-China Policy Foundation (USCPF), and the Committee on Scholarly Communication with China (CSCC). These bodies have collectively helped to stabilize China’s role in Washington, including agenda setting, early warning, public education, and informal lobbying.” (Calder 2014: 145)

He adds, “While these mediating NGOs have some analogue in U.S. relations with NATO, and to a lesser degree in American ties with Korea, they have no good parallel in U.S.-Japan relations.” (Calder 2014: 146) Perhaps, but Calder’s description of the China lobby seems quite analogous to what Angel writes about the Japan Lobby and the influential US-Japan Council, according to its website, “is a Japanese American-led organization fully dedicated to strengthening ties between the United States and Japan in a global context.” Moreover, Calder’s high appraisal of China’s lobbying efforts is unconvincing as its soft power efforts have fallen flat and its lobbying is widely disparaged as heavy-handed and ineffective.

In contrast to Beijing’s ostensible PR juggernaut, Calder writes, “over much of the past two decades, both the Japanese government and the country’s private sector had a remarkably low profile in Washington, even as their competition has grown more active.” Calder paints a picture of a receding Japan across-the-board with significant recent declines in Congressional exchanges, fewer think-tanks with Japan-oriented programs, fewer Japan specialists in Washington, and a shrinking number of Japanese students and researchers in the US.

Yet on history issues, the Embassy has been assertively engaged, especially regarding the comfort women. Calder blasts the 2007 debacle when, “the embassy spent substantial political capital trying to head off a congressional resolution of censure (H.R. 121) … that offended both major human rights and Asian American constituencies in the U.S. Congress and the Democratic Party. The struggle ended with a motion of censure, opposed by the Japanese Embassy in Washington, passing the U.S. House of Representatives.” It was not helpful that on June 14, 2007 conservative Japanese supporters of Abe’s apologist stance on the comfort women placed a full-page Washington Post ad blasting the resolution on the eve of the vote, making it awkward for Japan’s friends on the Hill to stave off the legislative censure as they had several times before.

|

This is the ad placed in the Washington Post on June 14, 2007 by the Committee for Historical Facts. |

Calder, (2014:186) also asserts there is a more proactive approach to mobilizing Japanese–Americans, “Since early 2009, when the U.S.- Japan Council (USJC), a group of Japanese American leaders devoted to maintaining effective working relations among American, Japanese, and Nikkei communities was founded, relations between the embassy and the Japanese American community have grown even closer.” The USJC was established at the instigation of Hawaiian Senator Daniel Inouye (1924-2012), the most prominent Japanese-American politician in U.S. history who was an ardent opponent of Congressman Mike Honda’s comfort women campaign and a reliable supporter for Tokyo in the corridors of power.1 Below we discuss this development regarding the anti-comfort women statue campaign in San Francisco.

Calder is less impressed by what he characterizes as Japan’s inbred, hereditary diplomatic corps, concluding that it has not been terribly effective: “In bilateral skirmishes within Washington against East Asian neighbors over territorial and historical issues, for example, the neighbors typically come out ahead, although Japan achieves its policy goals bilaterally with the United States on most important security questions.” (Calder 2014:188)

Ringing the alarm bells, Calder adds, “Also in 2009 as much as 60 billion renminbi ($8.8 billion) was pumped into the Big Four Beijing media outlets (Xinhua News Agency, CCTV, China Radio International, and China Daily) to fund their global expansion.” China has also been nurturing closer relations with the 4 million Chinese American citizens of the United States, something he believes Japan has found more awkward due to wartime internment of Japanese-Americans.

William Brooks (2013), a 35 year State Department veteran and adjunct professor of Japanese Studies at SAIS, agrees that Japan is losing out to China in the information wars waged in Washington between these East Asian rivals, writing, “it is increasingly the focus of an enhanced media-centered effort to favorably influence American views in the capital area and across the country on their respective countries. China, through its sophisticated CCTV World channel, has emerged as the clear technological leader in the de facto information-providing rivalry with Japan. It has set up a Washington bureau and state-of-the art programming that is as sophisticated as CNN’s, even to the extent of adding top-notch American anchors and reporters to present hard-hitting balanced news and features to a world audience. Japan has no comparable U.S.-based programming.” In his opinion China has earned a super-achiever award for its English language media efforts, noting that the China Daily US edition is available on Kindle for only $5 a month, China Watch is a free insert in major newspapers like the Washington Post and CCTV broadcasts (with 2 channels in English) are readily available on satellite, cable and the Internet. All of this helps shape US opinion towards China and gives it an opportunity to counter negative coverage in US and other international media while also presenting human-interest stories that appeal to audiences. It also broadcasts grisly documentaries about the Sino-Japanese war that viscerally challenge the revisionist history tropes favored by PM Abe and other revisionists. But who actually watches CCTV and to what extent are they persuaded by Beijing’s propaganda since nobody believes that press freedom exists in China for the very good reason it does not and the intimidation and arrest of journalists for doing their job is routine. Moreover, China’s forays into social media have repeatedly back-fired as videos depicting various aspects of China such as the making of the thirteenth five-year plan seem more a cringe worthy parody of nation branding than crack public diplomacy.2

|

While Japan has NHK World, its level of professionalism pales in comparison to CCTV and, Brooks points out, it doesn’t tailor its programs to US audiences the way that CCTV does. The Japanese media, in his view, is far better at disseminating news about the US to Japanese rather than conveying Japan’s views and influencing American public opinion. Instead, “There seem to be endless fashion shows and cooking shows, and the emphasis on “Cool Japan” – programs centering on the wide-eyed views of young foreigners living in Japan regarding aspects of the country that appeal to them, or perplex them.” Brooks concludes that, “While China is making a tremendous effort to reach American audiences with a full platter of news, documentaries, special programming, and broadcasts out of Washington and New York, Japan seems to be slipping off America’s radar scope as information from domestic and Japanese news sources tailored for an American audience becomes a scarce commodity.” In his view, by remaining passive in this lopsided information war, Japan’s media have punched below their weight in the US to the detriment of Japanese interests.

Japan’s Public Diplomacy

A veteran Japan hand with extensive government and academic experience warns that, “The Abe administration has a bad reputation among some segments in Washington because of the history issue. That is well known. The problem here is the tendency for the GOJ to shun those who are critical of the Abe administration — probably on orders from thepolitical elite. Abe’s April 2015 speech to Congress helped repair his tattered image, but if he issues a statement in mid-August that is seen as watering down Japan’s previous apologies for wartime acts, then no matter how much money is poured into PR, it won’t buy any goodwill in this town. He will be pilloried.” Perhaps, but Abe did not get pilloried for his evasive August 14, 2015 statement, perhaps attesting to savvy image management by PR firms.

An American insider with extensive foundation experience involving Japan explains, “the Gaimusho has become much more serious about its public diplomacy efforts in the States. The Embassy has pumped a lot of money into the major think tanks in Washington in order to support Japan-related public events and projects. MOFA has also published glossy brochures in English that argue Japan’s position on various disagreements with China (and South Korea re the Takeshima/Dokdo dispute). Japanese funding is underwriting visits to Japan by young Americans and there is increased funding for English-speaking Japanese scholars who can more articulately argue Japan’s case in overseas academic forums and the like.”

“So what we’re seeing now is a much more sophisticated and well-funded public diplomacy effort by Japan than in previous years. It’s hard to gauge how effective and influential this ultimately is–particularly in the universe of other countries’ charm offensives in Washington. True, it may be paying more than other countries, but it also has deeper pockets than most other countries and, as far as its national interests are concerned, it cannot afford to be marginalized in the capital of its sole security guarantor,” he says.

Moreover, “Another dilemma for Japan is that it has to strike the right balance between public diplomacy and carrying out an all-out propaganda campaign. The latter might backfire if it’s seen as too heavy handed. For instance, I’m not sure but I don’t think that the GOJ is explicitly telling the think tanks that it’s funding to promote a specific message about history or territorial issues, etc. You might say that that’s implicitly expected through the financial support that the GOJ provides.”

“That said, I’m not naive enough to think that all this money swirling around is of no concern whatsoever. I am somewhat concerned about the quality of objective analysis of Japan when so many American researchers and scholars depend on Japanese money for their livelihood. The Abe administration is particularly thin-skinned when it comes to outside criticism and I wouldn’t be surprised if it were to withhold funding from people that it considers “unfriendly” to its cause.

So, I guess in the final analysis, Japan is certainly playing hardball in the public diplomacy realm. (emphasis added) That may at times seem over the top but I do think there is a vigorous message war going on between China and Japan, and the GOJ has to do what it can to come out on top of that game.”

|

Brad Glosserman, Executive Director of Pacific Forum CSIS Hawaii and co-author of The Japan-South Korea Identity Clash: East Asian Security and the United States (Columbia 2015), says, “if the question is the competition for influence WITHIN the US, I don’t think Japan has much to worry about. There is interest, there is knowledge, there is suspicion and there is influence – all are different outcomes and I am not sure that China is getting much positive out of their Confucius Institute (CI) program; academics are very mixed, China specialists typically scathing and administrators more supportive- until there is an incident that exposes Beijing’s heavy hand. In short, the best thing for Japan to do is to let the CI project be and not compete. I would have thought that the head to head competition with Korea over the comfort women statutes would have shown that such crude behavior is a loser’s bet.”

He adds, “the biggest issue is the lack of weight Japan brings to global issues and the global arena. Japan does seem like a presence that reflects an increasingly uchimuki (inward looking) mentality, a sense that the outside world is a hostile place, a sense that Japan is first and foremost Japanese, and of Asia, not in Asia, and certainly not in anywhere else.” Overall, Japan projects disinterest in global issues not directly affecting it such that “Tokyo seems an incredibly selfish actor. Either way, no one really cares about Japan’s preferences.”

There is little to worry about in terms of vying for US support because, “Japan has long had its group of supporters – the chrysanthemum crowd and alliance managers – that largely insulated it from the vicissitudes of waves of negative opinion. Absent some big screw up that harms US national interests, that buffer will remain.”

In his view, “competition with China is a losing bet. Tokyo doesn’t have to engage in that competition directly; Beijing will prove its own worst enemy. Japan should not position itself as an enabler or excuse for bad decisions in China. It should do its own thing and let its own values shine through.” It is thus perplexing to observe the counterproductive blunders of Abe’s brasher public diplomacy.

Japanese Hardball3

Despite Calder’s more benign assessment of a bumbling, slow off the mark public diplomacy, Japan is not exactly a retiring wallflower. As noted above, the Japanese government, foundations and firms have developed an influential network in the U.S. that dates back to the 1970s, an era of acrimonious trade frictions. This Japan Lobby has tackled various other issues and is now a valuable weapon in Japan’s public relations war against China in the US. The Sunlight Foundation and ProPublica estimate that total Japanese spending on lobbying and public relations was $4.2 billion in 2008, putting Japan third behind the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom while South Korea ranked eighth with $2.9 billion (ProPublica August 18, 2009).4 And this lavish spending is not new as The Center for Public Integrity found in 2005, for example, that Japan and China / Taiwan both ranked among the top ten in terms of lobbying expenditures during the 1998-2005 period. (Calder 2014:92)

Calder’s overall portrait of the Japan Lobby is a far cry from Angel and Hall’s account in the 1990s and Choate’s in the 1980s. In his view there have been signs of change since 2005 suggesting a more proactive and effective public diplomacy, but overall he still thinks Japan is losing this battle to its rivals from Seoul and Beijing. Brooks also suggests that Beijing has a much slicker, well-funded and effective media strategy and that there are very few efforts to project Japanese views in the US. It is important, however, not to confuse the quantity of funding with the quality of the public diplomacy and it is not clear that China’s efforts have in fact been very effective. Problematically, the target audience sees that hand of the state behind all of these initiatives, thus undermining their credibility and impact. For example, China’s Confucius Institutes have drawn considerable criticism that suggests that they have not been effective in improving US opinion toward China, but may have influence on the research agendas of China specialists and university departments’ hiring and public outreach activities. (Sahlens 2013, 2014)

|

China’s Soft Power Confronts Opposition. |

There are signs of a more proactive Japanese public diplomacy, but as with the comfort women resolution battle in the US Congress in 2007, the Embassy may be digging a hole, deepened by private efforts, in promoting a revisionist narrative of history that downplays Japanese depredations. It appears that the comfort women statues that are popping up around the US are attracting similar Japanese government and nongovernmental efforts that are likely to backfire, putting Japan into the crosshairs of history and gender.

In 2015 Japan announced it would treble its budget for public diplomacy to $500 million, apparently a response to perceptions that the governments of China and South Korea are embracing a more assertive diplomacy aimed at tarnishing Japan’s reputation. Japan’s diplomats now can’t complain about a lack of firepower in what is often likened to a public relations war. Conservatives have long grumbled that Japan’s diplomats have been ciphers on the world stage, adopting a reactive and ineffective approach to countering misinformation and misinterpretation of government policies and initiatives. But based on Japan’s recent miscues, taxpayers have every right to complain that this gold-plated, brazen diplomacy is undermining Japan’s stature. This lavish funding was also justified in terms of funding Japanese studies at universities to counter China’s Confucius Institutes and to establish Japan Houses in London, Los Angeles and San Paolo. It is not clear what role the Japan Houses will play that is not already being played by various existing organizations, but the sites were selected due to sizeable Japanese communities and it appears that they will serve to disseminate information and government views on issues that crop up in the media, promote soft power and generate sinecures for retiring diplomats.

Public diplomacy is the art of convincing and seducing other governments and people in other nations to agree with, support or acquiesce to the policies and positions of the practitioner’s government. On this score Japan is not doing too badly, but there have been some unfortunate lapses. For example, in January 2015 Japanese diplomats visited the offices of a US textbook publisher to complain about errors in a two paragraph descriptions of the wartime military “comfort women”, a bête noire of reactionaries and the government of Prime Minister Abe. The world history textbook in question does contain several errors, but the question is whether this diplomatic pressure was the best way to handle the problem. Presumably, diplomats understand the society in which they are representing their government so could have anticipated the resulting US media backlash against Japan, one that questioned Tokyo’s stance on press and academic freedoms.

Perhaps more successful are the ‘infomercials’ that Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has run on CNN, one in 2016 focusing on the Rule of Law at Sea that highlights naval cooperation with Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines. (Japan Times, March 15, 2016) China is not named, but is nonetheless implicated as the transgressor and common threat. These expensive forays into public diplomacy on international commercial television signal an end to Japan’s low-key diplomacy and suggest just how high Tokyo thinks the stakes are in the battle with China for global hearts and minds.

|

Cartoon depicting aggressive China. |

The conservative Sankei newspaper advocates a more aggressive diplomatic stance on history issues that dovetails with the mission of Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), a neonationalist organization including numerous LDP Diet members, and a sprinkling of high profile pundits and presidents of companies and universities. From their perspective Japan has been too reticent and too polite; it needs to take the gloves off on the world stage. It does not seem to have occurred to them that this might be a counterproductive strategy and that on history issues it leaves Japan vulnerable to criticisms of whitewashing, backsliding and promoting an exonerating narrative that glorifies wartime and colonial excesses.

Actually, Japan’s reticent diplomacy over the years has paid dividends as polls show that Americans rate Japan more highly on history issues than Germany, a nation usually held up as the model penitent. It takes confidence for a government to acknowledge and atone for the shameful past, build a track record of peace and believe that global support will follow. Polls indicate that Japan’s self-effacing style over the years has won widespread admiration for Brand Japan, but this is now at risk from the Abe government’s swaggering public diplomacy, a shift in tone that reflects more diffidence than confidence. Let’s examine a few instances where Japan’s hardball has backfired.

|

Sakurai Yoshiko is a prominent conservative pundit affiliated with Nippon Kaigi. |

Germis Affair 5

In an April 2, 2015 essay in the Number One Shimbun published by the Foreign Correspondent’s Club of Japan, veteran German journalist Carsten Germis wrote about his experiences of being harassed by the Japanese government basically for doing his job. In his view, the Abe government is overly sensitive to press criticism and responds aggressively in trying to suppress such views. Team Abe has been especially sensitive to criticism about what Germis terms, “a clear shift that is taking place under the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – a move by the right to whitewash history.”

In 21st century Japan, there is far too much official paranoia that all criticism of Japan is aiding and abetting China and Korea. Officials everywhere get testy about negative coverage and Japan is certainly not the only country where journalists are singled out for harassment. Journalists who have worked in China have many stories to tell about intrusive monitoring and restrictions that make reporting the news in Japan seem relatively easy and pleasant. But everyone knows that China is not democratic and doesn’t tolerate a free press while it is generally assumed Japan is and does. The intolerance towards criticism is based on the erroneous belief that all criticism of the Japanese government, and or Abe, reflects anti-Japanese sentiments. There is also a presumption that journalists are “guests” who should be polite to their hosts while scholars who take Japanese research money also risk being labeled traitors if they express critical views.

Anna Fifield, the Washington Post’s Tokyo correspondent has written about Tokyo’s clumsy media intimidation and says, “As we can see in the cases of NHK and Asahi being hauled over the coals for their reporting, the Japanese government is trying to silence anyone who doesn’t toe the government line, but the government has a much harder time restraining the foreign press in this way. That doesn’t mean they’re not trying. Like many other foreign journalists, I’ve been on the receiving end of unwelcome emails trying to influence my coverage on the history issue.” 1 Justin McCurry at the Guardian, David McNeill at The Independent and The Irish Times, Martin Fackler at the NY Times and others relate similar experiences. This can’t help Japan’s image.

|

Carsten Germis’s visit to the disputed islands of Dokdo/Takeshima drew the ire of Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. |

Germis argues that if Japan’s popularity in Germany has suffered, it is not due to the media coverage, but to Germany’s easily understood repugnance at historical revisionism. In this context, the Japanese government’s efforts to promote an exonerating and valorizing narrative of the wartime past are self-defeating. Germis revealed that, “The paper’s senior foreign policy editor was visited by the Japanese consul general of Frankfurt, who passed on objections from ‘Tokyo.’ The Chinese, he complained, had used it for anti-Japanese propaganda.”

“It got worse. Later on in the frosty, 90-minute meeting, the editor asked the consul general for information that would prove the facts in the article wrong, but to no avail. I am forced to begin to suspect that money is involved, said the diplomat, insulting me, the editor and the entire paper. Pulling out a folder of my clippings, he extended condolences for my need to write pro-China propaganda, since he understood that it was probably necessary for me to get my visa application approved.”

“Me? A paid spy for Beijing? Not only have I never been there, but I’ve never even applied for a visa. If this is the approach of the new administration’s drive to make Japan’s goals understood, there’s a lot of work ahead. Of course, the pro-China accusations did not go over well with my editor, and I received the backing to continue with my reporting. If anything, the editing of my reports became sharper.”

The Japanese diplomat subsequently alleged that he never made such allegations, possibly due to the misunderstanding of the editor or an error in translation. (Asahi 4/28/2015) Dr. Peter Sturm, the FAZ editor involved, emailed me that the conversation with the Japanese Consul General took place in August 2014. “He said he was instructed by ‘Tokyo’ to lodge a formal complaint about Carsten Germis’ reporting. He had with him a number of papers in Japanese, which he continually consulted during the conversation. He also submitted a letter to the editor by the Japanese Ambassador to Germany (in German) that we published on our letters page a day or two after the conversation had taken place. In this letter the Ambassador summarized the official position of the Japanese Government. The conversation was conducted in German, which the Consul General speaks excellently. Therefore there was no interpreter present.” (Personal communication April 28, 2015)

Sturm added, “I can confirm the Consul General made the remarks about Carsten Germis’ personal integrity exactly in the way Carsten reported. As far as our newspaper and me personally are concerned we never were ‘anti-Japanese’ – or ever will be. I tried to tell the Consul General that our concern about certain aspects of policy, which had found their way into the columns of the paper were derived solely from a deep sense of friendship towards an allied country.”

In these times those who criticize Abe are often accused of Japan-bashing and venality. This is a convenient way to marginalize critical voices, suggesting that they have insidious motives and are helping, as alleged in the Germis case, Chinese propagandists in exchange for money and favors. It doesn’t seem to matter that no evidence was presented or that such allegations are demonstrably untrue. Labeling critics as Japan-bashers evades engaging the arguments and the facts and instead relies on cheap shot ad hominem attacks, tarnishing Japan’s image.

Officials also warned several foreign correspondents, including Germis, not to interview Nakano Koichi, a respected political scientist at Sophia University. Nakano’s critical assessments of PM Abe’s policies and revisionist views on history are widely quoted. The government’s press handler asserted that he is unreliable and steered journalists to sources that adhere to the government line, including a free lance foreign journalist who appeared on the scene in 2014 with no prior experience in Japan. Doing so only enhanced Nakano’s reputation and boosted interview requests because journalists understand that if the government is slagging him, it is probably because he speaks truth to power. Other foreign journalists confide that they have felt pressure and know that their reporting might jeopardize gaining access, as blacklisted reporters/newspapers don’t get interviews with Abe or his inner circle. Some current and ex-government officials confide that they personally think Team Abe’s effort to more aggressively assert revisionist history is counterproductive and harming Japan’s international image, but they do as they are told.

Controlling the press has become more toxic in contemporary Japan because it involves government officials, and those who do their bidding, impugning the professional integrity of journalists and their sources as a way to discredit the analysis. Spin doctors everywhere massage the message, wine and dine journalists, dangle access as an inducement and take umbrage at what they feel is unfair reporting, but what is now going on in Japan is getting more “Rovesque”. Karl Rove and Scooter Libby in the Bush Administration reveled in their power and intervened aggressively to push their storylines in ways that rewrote the rules of engagement with the press. Libby was convicted of a felony for his role in “Plamegate” that involved outing Valerie Plame a CIA agent, the wife of Joseph Wilson, an administration critic.

Nothing that the Kantei (Prime Minister’s Office) has gone so far comes close to that level of vindictiveness, but as Martin Fackler explains, “Some degree of push back by governments against media coverage is normal in most democracies. For instance, I have dealt with White House press handlers who will bite hard if they think reporters have misrepresented what the President said. On the other side of the coin, the Japanese government goes further in certain ways, playing this game of denying access to and bad mouthing journalists who don’t toe the line. I think they use these tactics because they probably work with the local press. I’m surprised that they’d think the same tactics would work on foreign press.”2

Why is the government expending so much political capital on promoting revisionism and going after critical journalists? Ellis Krauss, a leading specialist on the Japanese media at the University of California-San Diego, told me, it was “…because for most of the postwar period the Left always connected the defense/Article IX issue to the war guilt. So Abe and his cronies believe that unless they legitimize the prewar military they won’t be able to justify the SDF and constitutional changes they want to make.”3

Krauss also thinks that, “MOFA is trying desperately to please Abe for fear he will pick on them as a scapegoat. The media is cowed…This campaign reflects a huge insecurity, not confidence, about Japan, about their identity, about their history.”

Krauss has coined the term “Abenigma”, noting that, “the real mystery is why Abe and the Japanese media don’t realize how counter to Japan’s own national interests this is. War memory is an issue that Japan cannot win on. Right wing denials only help the Chinese and Korean nationalists (who are themselves irrational on this issue), and will alienate Americans, their strongest ally, and the Europeans and Australians, their natural democratic friends.” In his view it’s not about apologizing, but rather “it’s about denial, like Holocaust denial in Europe. The best thing the Japanese government and right wing can do for Japan’s own interests is just shut up on these issues.” But, Abe’s advisors and supporters take a rather different view on national interests and, seeing the battles over history in terms of identity politics, insist on exculpatory revisionist narratives that draw international censure.

Churlish on UNESCO

The Japanese government’s denunciation of UNESCO’s decision in October 2015 to inscribe China’s submission of “Documents of Nanjing Massacre” in the Memory of the World Register is both churlish and regrettably one-sided. Such fulminating damages Japan’s reputation because it sends a message that the government is seeking to downplay or deny the atrocities committed by Japan’s Imperial Armed Forces in the war of aggression it instigated against China. At the same time, UNESCO also accepted two sets of archives compiled by Japan, including a submission about mistreatment of Japanese POWs by the Soviet Union following the end of WWII; of 600,000 sent to Siberia, 60,000 never made it home. So Japanese accusations that Beijing is politicizing UNESCO seem self-serving and inconsistent. Oddly, Japan alone is allowed to position itself as a victim of WWII while nations victimized by Japanese imperialism are castigated for drawing attention to Japan’s misdeeds and subject to accusations of discrediting the Memory of the World Register. UNESCO did not accept China’s dossier on the comfort women, a decision that further undermines Japan’s intemperate attack on UNESCO’s alleged bias.

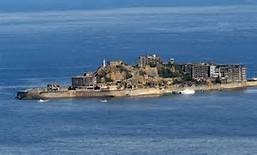

|

Hashima (aka Battleship Island) site of coal mine where Koreans were pressed into service during the early 20th century was subsequently made famous in the James Bond movie Skyfall (2012) and as of 2015 was designated an UNESCO World Heritage site. |

In July 2015, the government also made a hash of the UNESCO designation of 23 Meiji Industrial Revolution sites after some very public wrangling with South Korea, with Tokyo also accusing South Korea of politicizing the process. Seoul had opposed the listing of seven sites honoring Japan’s modernization because they involved 57,900 Korean forced laborers, but finally acquiesced to Japan’s proposal. This is because Japan agreed to establish an information center that would acknowledge the forced labor and because Japan’s ambassador to UNESCO Sato Kuni stipulated, “Japan is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites, and that, during World War II, the Government of Japan also implemented its policy of requisition.” The meeting of minds was short lived as Foreign Minister Kishida asserted, quite wrongly, that “forced to work” does not mean “forced labor”. This peevish outburst was probably aimed at smoothing the ruffled feathers of benighted LDP constituencies, but that does not make his remarks any less fatuous and unbecoming of Japan’s top diplomat. Additionally, in the wake of the brouhaha Japan dispatched an envoy to meet with Bulgarian Irina Bokova, the Director General of UNESCO, providing an opportunity to express a desire to appoint a permanent Japanese observer to the Memory of the World Register while conveying veiled threats about withdrawing Tokyo’s funding, and dangling the possibility of GOJ support should she decide to run for UN Secretary General, apparently contingent on accommodating Tokyo’s concerns

Flouting Rule of Law

In the category of what not to do, resumption of whaling is a major stumble for Japan because it undermines its rule of law diplomacy in ways that anger many of its major allies and others. In the war of words with Beijing, Tokyo has gained moral authority by criticizing its rival for not abiding by the rule of law and trying to change the status quo through unilateral military coercion. So Japan’s defiance of the International Court of Justice’s ruling that Japan’s research whaling program in Antarctic waters violates the terms of the 1986 moratorium of the International Whaling Commission is a major setback because in doing so Japan is exempting itself from the rule of law it otherwise assiduously upholds.

|

In 2016 Japan resumed whaling in defiance of the ICJ. |

When the ruling was issued in March 2014, Japanese foreign ministry spokesman, Shikata Noriyuki, told reporters that Japan respected the rule of law and would abide by the decision. This was the right call because by agreeing to participate in the ICJ process Japan and Australia committed to accepting the outcome. Subsequently, in 2015 Japan reversed itself and is now flouting the ruling by resuming the whale hunt in the Antarctic. This is not a good precedent to shore up Japan’s legal position in any potential future arbitration cases that might arise over territorial claims or EEZs. Moreover, in terms of public image in the US, Europe and beyond, whaling is a losing proposition, something that provokes a viscerally negative reaction. In 2016, for example, Japan’s research whalers killed over 200 pregnant minke whales in the Antarctic, justifying this cull as essential to determine the age at which minke whales reach sexual maturity, but again convinced few in the court of public opinion while disregarding the rule of law it frequently invokes in pillorying China’s territorial aggrandizement. Domestically its also hardly inspired policy given that almost no Japanese consume whale, and the entire program is only viable with heavy government subsidies. Moreover, health authorities have found very high concentrations of mercury and PCBs in whale meat, advising pregnant women not to eat any at all. Pro-whaling advocates in the Japanese government and Diet may think they are justified on cultural and culinary grounds, but they are harpooning Brand Japan. Nevertheless, their transgressions pale in comparison to revisionists’ falsehoods seeking to rehabilitate Japan’s shabby wartime past.

Statues of Reproach

Like many other academics and journalists in Japan and the US, in 2015 I received copies of two books from Dr. Kuniko Inoguchi, an LDP member of the Upper House: History Wars: Japan-False Indictment of the Century compiled and published by the Sankei Shimbun and Getting Over It! Why Korea Needs to Stop Japan Bashing by Sonfa Oh a professor at Takushoku University in Tokyo. The U.S.- registered Japanese nonprofit Global Alliance for Historical Truth claims credit on its website for the Sankei book distribution. Dr. Inoguchi laments that unnamed individuals with political ambitions have distorted 20th century regional history and that “this distorted history has been exported into some areas outside of East Asia.”

|

Revisionist tracts sent to Japan specialists around the world. |

It is unlikely that these polemical jeremiads will convince anyone to change their mind and are more likely to incite a negative reaction in the US because they read like propaganda. The Sankei slams China’s alleged backing of a comfort woman statue and Pacific War Museum in San Francisco, apparently misunderstanding the local politics of these initiatives. It conveniently overlooks how in 2013 Hashimoto Toru, as mayor of Osaka, sister city of San Francisco, drew the ire of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors with his comments justifying and downplaying the comfort women system. The Sankei raises the alarm about ongoing “History Wars” in the US, what it calls the main battlefield for public opinion, asserting that China is orchestrating discord between the US and Japan. If so, Beijing is doing a lousy job as more Americans by far distrust China, by an almost 2:1 margin; only 38% of Americans have a high opinion of China while 74% have a favorable view of Japan. (Pew 2015)

Local Bay Area activists report that before the Board unanimously approved the comfort women memorial in September 2015, the Japan Lobby was vigorously working behind the scenes to kill the resolution. Local Japanese-Americans privately confirm that disinformation was sowed and that they were pressured to lobby against the resolution, with continued Japanese corporate funding hanging in the balance. One wrote in an email: “The Consulate General of Japan was not just actively lobbying against the proposed resolution on recommending a “comfort women” memorial in San Francisco, but also feeding false rumors to prominent members of Japantown establishment and pressuring them to support its effort to block the resolution, creating serious divisions within Japanese American community as well as in larger Asian American community.” Another referred to Japanese pressure brought to bear on Board members, with “the implicit threat that Jtown’s political contributions may be at stake. But they took notice when the API (Asia Pacific Islander) Caucus of the California Democratic Party endorsed the resolution. We need more support from the Democratic leadership (endorsement letters, etc.) to push back against the ugly foreign government intervention on our political process.”

The Board disregarded spurious allegations about incidents of discrimination and bullying targeting ethnic Japanese children in Glendale, California after a comfort woman statue was erected there. A local SF observer reports that, “Supervisor Mar contacted various people in Glendale, including city officials, board of education, local Japanese American groups, and others and confirmed that there are no such bullying or hate crimes against Japanese/JA children there.” Glendale authorities dismissed these unsubstantiated allegations as fabrications by opponents to the statue, pointing out there were no reports to schools or police at the time. It seems that Japan would do better to ignore these statue and memorial initiatives because intervention has repeatedly backfired, throwing fuel on the fires of recrimination over the shared East Asian past of colonialism and war. Two new ones unveiled in October 2015 in Seoul, one placed by Chinese-American activists depicting a Chinese comfort women, and an appeal to add a Filipina statue to the memorial, suggest the perils of Japan’s current tactics.

|

Japanese delegation protests Glendale’s comfort woman statue. |

Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and South Korean President Park Geun-hye understand something needs to be done about the comfort women issue, but they still have a way to go. It is unlikely that the Dec. 28, 2015 “final and irreversible resolution” to issues surrounding the women who worked in wartime brothels at the Japanese military’s behest will prove to be much of a resolution at all. Indeed, the clever evasions and semantic parsing could easily unravel and become another bone of contention and trigger renewed mutual recriminations. The UN has issued a yellow card to Tokyo on the 2015 comfort women agreement, with the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) stating it, “did not fully adopt a victim-centered approach” and was evasive on responsibility for the human rights violations endured. In its March 2016 report, CEDAW also admonished Japanese leaders for ongoing disparaging statements about the comfort women and urged the reinstatement of the comfort women issue in secondary school textbooks. Subsequently, on March 11, 2016 a group of UN human rights experts issued a statement rebuking the Japanese and South Korean governments for the diplomatic chicanery, insisting that they, “should understand that this issue will not be considered resolved so long as all the victims, including from other Asian countries, remain unheard, their expectations unmet and their wounds left wide open.” They also expressed concern that the South Korean government “may remove a statue commemorating not only the historical issue and legacy of the comfort women but also symbolizing the survivors’ long search for justice.”

Japanese conservatives insist that the Yen 1 billion (about $8 million) Seoul is promised under the accord won’t be paid until after the comfort woman statue across the street from the Japanese Embassy is removed, but citizens maintain a 24/7 vigil around the bronze figure of a school girl to prevent its removal. Forcible removal risks igniting a firestorm of protest that would ensure the accord going up in smoke and perpetuation of bilateral discord no matter what the diplomats want to believe. But if the statue remains, the accord will be derailed because the ‘not called reparations’ won’t be paid.

In addition to such diplomatic deceit, Japan’s hardball tactics on the comfort women issue involve crude campaigns in the U.S. What should we make of the Voices of Vietnam, a well-funded group that has hired former Minnesota senator Norm Coleman to be the point-man in demanding President Park Geun-hye apologize for Vietnamese comfort women who served some 320,000 Korean soldiers fighting at the behest of Washington in the Vietnam War? This organization held a press conference on October 15, 2015 in connection with Park’s summit with President Obama, timed to maximize publicity. In a Fox News op-ed published on the eve of the summit, Coleman demanded Park apologize to the Vietnamese victims of Korean sexual predations, write, “Failing to make such an unequivocal apology would only undermine President Park’s moral authority as she presses Japan to apologize for the sexual violence perpetrated against South Korean ‘comfort women’ during World War II.” Apparently attacking Park is the main mission of an organization that seems, rather curiously, to have sprung up out of nowhere according to contacts in the Vietnamese U.S. diaspora. Certainly, amends to these women-there are an estimated 800 survivors who served Korean soldiers- and the thousands of children of mixed ancestry born to them are in order, but why hasn’t Coleman spoken out about the far larger, problem involving US soldiers? And, does Coleman think that the comfort women system is really the same as what happened in Vietnam?

|

South Koreans opposed to removal of statue. |

K-Street Maneuvers

K Street is synonymous with lobbying and PR firms that offer clients services that help them gain access and convey their messages. Japan vigorously lobbied to amend the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) in the US, hoping to make adjustments in line with Japanese government desires. Wilson and Needham (2014) writing about Japanese lobbying on TPP in the newsletter The Hill reported that, “Akin Gump was influential in the creation of the U.S.-Japan Caucus in Congress, cofounded last year by Reps. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.) and Joaquín Castro (D-Texas). Japan paid Akin Gump $638,000 last year, the most of any firm it had on retainer.” The Hill reports that overall Japan spent $2.3 million on US consultants from 2014 until early 2015 and keeps 20 firms on retainer.

Ackley (2015) adds, “The government of Japan knows its way around K Street. In the months leading up to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Washington this week, the country spent more than $1.2 million on lobbying, law and public relations firms, according to documents filed with the Justice Department. As the country navigates numerous policy issues, including a massive trade deal with the United States, it relies on the hired help of such firms as Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, Hogan Lovells and the Podesta Group. Japan enlisted the Daschle Group, the firm of former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D., just this month. “

|

PM Abe addresses joint session of the US Congress April 29, 2015. |

Bogardus (2014) writes, “K Street operators… offer on-the-ground intelligence about Congress and the executive branch that diplomats and other Japanese officials might otherwise miss. They also help forge ties and set up meetings with government officials, think tank policy wonks, corporate lobbyists and journalists.” Lobbyists also are monitoring the comfort women story for the Japanese Embassy: “K Street has compiled information on meetings between House members and Korean-American groups – many of which pushed for the original resolution. Hogan Lovells also tracked what Honda, Royce and Ros-Lehtinen said during an event honoring the sixth anniversary of passage of the comfort women resolution. The firm has also compiled a list of memorials to comfort women across the United States, as well as advertisements and state legislation. ” (Bogardus 2014)

Rabin-Havt (2015) explains the logic of hiring former high ranked officials and politicians, “This points to the reason Japan and other countries are eager to hire former senior members of Congress and well-connected insiders. The ability to glean information from former colleagues and contacts is just as important as their skill at influencing legislative and administrative outcomes. This expertise is particularly crucial during complex foreign negotiations requiring approval of a finicky and partisan Congress.”

Conclusion

It is hard to reconcile Calder’s wallflower Japan with significant counter evidence discussed above about a more aggressive public diplomacy as the hybrid public and private sector efforts of the Japan Lobby are playing hardball, especially on history issues, and ramping up overall lobbying efforts. Calder’s view that Japan’s public diplomacy has not been as effective as its rivals and inept in identifying and exploiting opportunities is not convincing. China seems even more hopeless than Japan in public diplomacy. Japan is not alone in hiring lobbyists and is not the only nation underachieving on its public diplomacy, but like China, its hardball tactics seem to be backfiring. Given the reservoir of goodwill in the US public towards Japan, and favorable attitudes at the highest level of government that contrast with hostility towards China, Japan would be better served by a low key public diplomacy rather than the more imperious approach favored by Team Abe.

The Japan Lobby is becoming more active under PM Abe and fighting battles over history that are not promoting a more positive image. It need not do so as a 2015 Pew Poll indicates that Americans rate Japan more highly on dealing with wartime history than Germany, the nation usually touted as the model penitent; 61% of Americans believe that Japan has apologized enough or has nothing to apologize for compared to 54% expressing similar views about Germany. (Pew 2015) There is a risk that Japan’s newly aggressive strategy on wartime controversies will backfire, undermining goodwill in the US while roiling regional relations in northeast Asia. Japan has reaped the benefits of a more reticent, self-effacing diplomacy, one that acknowledged much more about wartime excesses than the Abe Cabinet is prepared to tolerate. The growing intolerance in Japan toward critics in media and academia handicaps Japan’s public diplomacy while revisionist rewriting of history makes it look like its shirking responsibility. In short, hardball history initiatives represent a dead-end and Japan would be better served in its PR battle with China by focusing on contemporary security and territorial issues and championing the rule of law where its case is far more compelling. Quibbling and caviling over memory wars that focus global attention on Japan’s worst moments is a dead-end, no-win strategy. This distracts attention from Japan’s strengths and its enormous accomplishments over the past 70 years in promoting peace, stability and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific. In promoting a national identity that takes pride in the nation, it is this post-1945 record that merits the limelight. Thus, Abe and fellow revisionists are unwittingly helping Asian rivals and undermining Japan’s public diplomacy.

SOURCES

Ackley, Kate. “Japan Taps Lobbyists to Bolster U.S. Ties”, Rollcall, 4/27/2015

Angel, Robert. “The Japan Lobby” Asian Perspective Vol. 24, No. 4, Special Issue on Dysfunctional Japan: At Home and In the World (2000), pp. 37-58

Angel, Robert. (1996) The Japan Lobby: An Introduction. JPRI Working Paper No. 27: December.

Baerwald, Hans. Fund-Raising in Japan: A Sasakawa Saga , (JPRI Occasional Paper No. 3 , May 1995).

Bogardus, Kevin. “Japan turns to K Street amid calls for apology on WWII-era ‘comfort women'” The Hill Feb 6, 2014.

Brooks, William. (2013) “Changing Influence of Chinese and Japanese Media in Washington and America” Unpublished manuscript.

Calder, Kent. (2014) Asia in Washington. Brookings.

Fallows, James. Looking at the Sun: The Rise of the New East Asian Economic and Political System. Pantheon, 1994.

Farnsnworth, Clyde. “Americans who lobby for Japan”, NY Times , May 3, 1987.

Ishihara Shintaro (1989) The Japan That Can Say No. Simon & Schuster.

Johnson, Chalmers. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975. Stanford University Press.

Kingston, Jeff (2015a) “Are forces of darkness gathering in Japan?” Japan Times. May 16. (last accessed March 12, 2016)

Kingston, Jeff (2015b) “Testy Team Abe Pressures Media in Japan” May. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus” (last accessed March 12, 2016)

Kingston, Jeff. (2015c) “In search of Japanese and American shared values” Japan Times. June 20. (Last accessed March 12, 2016)

Kingston, Jeff (2016), “Hiroko Kuniya’s ouster deals another blow to quality journalism in Japan” Japan Times, January 23. (last accessed March 12, 2016)

McNeill, David. (2014) Japan’s Contemporary Media”, in Jeff Kingston (ed.) Critical Issues in Contemporary Japan. Routledge.

Nishino Rumiko and Nogawa Motokazu (2014) with an introduction by Caroline Norma, The Japanese State’s New Assault on the Victims of Wartime Sexual Slavery. The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 51, No. 2, December 22.

Pew (2015). “Americans, Japanese: Mutual Respect 70 Years After the End of WWII: Neither Trusts China, Differ on Japan’s Security Role in Asia”. Pew Public Research Center: Global Attitudes and Trends. (Last accessed March 12, 2016).

Prestowitz, Clyde.(1988) Trading Places: How We Allowed Japan to Take the Lead. Basic Books.

ProPublica (2009) “Adding it up: The Top Players in Foreign Agent Lobbying”

Rabin-Havt, Ari. “Bipartisan Agreement: Foreign Governments Pay Former Senate Leaders to Sell TPP”, The Observer June 11, 2015

Ramonas, Andrew. ” Japan’s Warriors: Trade Pact leads to a lobbying skirmish”, The National Law Journal, Feb 13, 2012

Sahlens, Marshall (2013) “China U”, The Nation Oct 30.

Sahlins, Marshall (2014) “Confucius Institutes: Academic Malware”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 46, No. 1, November 17, 2014.

van Wolferen, Karel. The Enigma of Japanese Power. Alfred A. Knopf, 1989.

Wilson, Megan and Vicki Needham (2014) “Japan Launches major blitz on trade” (April 28)

Notes

In June 2011, Inouye was appointed a Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers, the highest Japanese honor conferred on a foreigner who is not a head of state. He was only the seventh American overall and first Japanese-American to receive this award. He was decorated, “to recognize his continued significant and unprecedented contributions to the enhancement of goodwill and understanding between Japan and the United States.” Hawaii 24/7, June 22, 2011.

The focus here is on Japan’s public diplomacy and lobbying efforts, but it does appear that China engages in similar tactics through its Confucius Institutes in terms of influencing academia and the US-China Business Council that includes many Fortune 500 member firms that are experienced and adept at the art of political lobbying. In addition, Chinese-American groups are active, especially on war memory issues. Over the past two decades the growing heft of Chinese companies means they also can exert more influence in terms of where they decide to invest and the jobs that go with that. Clearly China does not gets its way on many issues such as buying firms deemed to have national security importance, trade disputes and its growing assertiveness in the South and East China Sea and polls suggest it has clearly not charmed the American public.

China did not make the list, but whether this means low spending on lobbying or something else is unclear and I have been unable to find comparable estimates of what China spends on lobbying.