Abstract

In discussions on Japanese whaling, a common question is why Japan appears indifferent to international pressure (gaiatsu) on the issue, that is, why it continues to flout the international anti-whaling “norm” despite widespread criticism and condemnation. The key to answering this question is to examine why the anti-whaling “norm” resonates so poorly in the domestic sphere. This paper argues that the impotence of international pressure to curb Japanese whaling can only be understood by examining how whaling has come to be reactively defined in the domestic debate not as an issue of conservation and environmental protection but as a symbol of national identity and pride. The paper concludes that because whaling is framed as a key marker of “Japanese-ness”, international pressure is counter-productive as it merely serves to stoke the fires of nationalism, creating an atmosphere in which anti-whaling opinion is seen as “anti-Japanese”.

Keywords: Whaling, Japan, national identity, international pressure (gaiatsu), nationalism

|

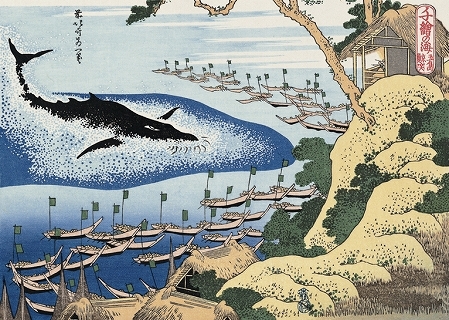

Hokusai, “Kujiratsuki” (Whaling), from Chie no umi (Oceans of wisdom), 1834. |

|

Hayashi Yoshimasa |

“I don’t think there will be any kind of an end for whaling by Japan…we have a long historical tradition and culture of whaling…criticism of the practice is a cultural attack, a kind of prejudice against Japanese culture.”

Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa, February 2013 (News.com.au 2013)

“The more the whaling issue becomes a racial or moral one, the more the Japanese will become unwilling to accept it…It has become a matter of international pride.”

Fisheries Agency Assistant Director Okamoto Junichiro, March 1989 (quoted in Miyaoka 2004: 96)

Introduction: Drive Fishery for Dolphins

In May 2015, the Japan Association of Zoos and Aquariums (JAZA) decided to ban member aquariums from acquiring dolphins caught by drive fishery (oikomi-ryō), a method of fishing that drives dolphins into a cove by banging metal poles. The decision was in response to the suspension the previous month of JAZA’s membership in the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) which deemed drive fishing cruel and unethical. If JAZA had not acquiesced to the international body’s demands, Japan’s zoos would have been unable to lease rare species from overseas for breeding and other purposes. JAZA’s “capitulation”, as the Yomiuri described it, to gaiatsu or international pressure is in stark contrast to Japan’s continued whale hunting which, despite international disapproval and legal rulings, continues unabated (The Japan News 2015a).

|

Drive fishing (oikomi-ryō), Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. |

One similarity between the dolphin incident and the debate on whaling was the denial of outside arguments that such fishing is “cruel” and the assertion that as “traditional Japanese culture” it deserves to be protected and continued. “WAZA’s lopsided attitude of paying no attention at all to a fishing culture unique to Japan,” argued an editorial in the Yomiuri, “while failing to specify what particular aspects of the fishing method should be deemed cruel, is extremely problematic” (The Japan News 2015a). The same publication, in an article entitled “‘Cruelty’ charge bewilders Taiji”, described “discontent and questions” about what exactly was cruel about drive fishery alongside details on improved culling techniques (The Japan News 2015b).2 One feature of the media coverage of this incident was the giving of voice to fishermen and other self-interested parties at the expense of ordinary citizens and Japanese animal rights groups.

The JAZA/WAZA dispute of May 2015 may provide some hints when attempting to answer one of the central questions in this paper: why has Japan’s whale hunting remained immune from the effects of gaiatsu? While international pressure – particularly UN and US pressure – on Japan has been strikingly successful in areas as diverse as trade, gender equality, indigenous people’s rights, and child-custody, Japan has remained unmoved by harsh international disapproval and even legal rulings against its whale hunts in the Pacific and Antarctic. The paper proceeds as follows: part one defines and introduces the concept of gaiatsu together with relevant examples. Part two looks at Japanese whaling in historical perspective. Part three examines the various international pressures brought to bear on Japan to end whaling and the Japanese government’s response, while part four describes how, in the domestic sphere, whaling has come to symbolise national pride, identity, and the Japanese race itself. The conclusion notes that heightened international pressure has had the opposite of the intended effect, actually strengthening Japanese support of whaling.

1. Gaiatsu (International Pressure)

The “gunboat diplomacy” forced opening of Japan to American trade by Commodore Perry between 1852 and 1854 and the ensuing unequal treaties is probably the most famous example of gaiatsu. In recent years, gaiatsu has been most closely linked to trade liberalisation, particularly agricultural trade liberalisation. Schoppa (1993), for example, in a study of the 1989-1993 US-Japanese negotiations known as the Structural Impediments Initiative (SII), examines the pressure put on Japan by the US to reform “structural barriers” to the expansion of US exports. Schoppa (1993: 368) concludes that “international pressure can make a difference”, but qualifies this by saying that “domestic political context matters as well.” This includes both public opinion and elite interests: elite and general public involvement and local media attention. In other words, the effectiveness of foreign pressure is not just about the strength of the demands but also about how these demands “resonate” in domestic politics (Schoppa 1993: 386). Schoppa uses Putnam’s “two-level game” theory to frame his argument. Also drawing on this model is Mulgan (1997) who notes that foreign pressure was often effective because it formed a convenient focus around which domestic pro-liberalisation forces could mobilise, adding crucial momentum to market opening.

The international/domestic “two-level game” theory also explains the success of a number of other recent examples of foreign pressure. One example was Japan’s indigenous Ainu who had long been denied recognition despite criticism and pressure from the United Nations.3 It was only in 1997 when a Japanese judge recognised, in a case over the construction of the Nibutani Dam in Hokkaido, that the Ainu were an indigenous minority that the government was forced to act, passing the Promotion of Ainu Culture Act in the same year. The momentum this provided for indigenous groups and their supporters in Japan undoubtedly influenced Japan’s decision to sign the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which in turn prompted official government recognition of the Ainu in 2008. Another example of the importance of domestic actors was the ratification of the international land-mine ban in 1998. Despite international pressure, Japan had initially dragged its feet on signing the accord. However, a rapidly expanding civil society, particularly post-1995, saw growing awareness of global issues at the grassroots level in Japan. Ultimately, Japanese NGOs, riding a wave of public interest in the issue, played a key role in pressuring the government to ratify the international land-mine ban in 1998 despite American opposition (Hirata 2002: 121).

|

|

| Nibutani Dam and Ainu Cultural Museum | |

A counter-example, which also supports the “two-level game” theory, relates to racial discrimination. Although, the UN International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) came into effect in 1969, Japan was one of the last developed countries to ratify it when it did so in 1995. Moreover, since ratification Japan has come under constant criticism by the UN for not introducing domestic legislation against racial discrimination despite its obligation to do so in the treaty:

The Committee noted with concern that although article 98 of the Constitution provided that treaties ratified by Japan were part of domestic law, the provisions of the Convention had rarely been applied by national courts. In light of the information from Japan that the direct application of treaty provisions was judged in each specific case, the Committee sought clarifying information from Japan on the status of the Convention and its provisions in domestic law (United Nations 2001)

However, despite frequent reminders that it is necessary for Japan to adopt specific legislation to outlaw racial discrimination, there has been no progress on this issue. Calls to adopt domestic legislation heightened with the emergence of hate-speech demonstrations against Koreans in 2013; in July 2014, the UN Human Rights Commission recommended outlawing hate-speech (Japan News 2014b) while the following month the CERD Committee reminded Japan again of its obligation to “to reject all forms of propaganda aimed at justifying or promoting racial hatred and discrimination and take legal action against them” (Japan News 2014c). However, despite some political discussion on the issue of hate speech, there have been no moves to enact a domestic law on racial discrimination. A key reason for intransigence may be the lack of popular interest in this issue; Japan has a relatively small foreign population (less than 1.7% of the total population) and a strong emphasis on assimilation and homogeneity. There is also marked opposition to increased migration: a recent Yomiuri poll found that 61% of Japanese were against allowing in foreigners who want to settle in Japan as migrants (Yomiuri Shimbun 2015b). In sum, it is not an issue that arouses much public interest or sympathy and there is little political benefit to introducing legislation.

In the above example, the lack of direct US pressure on Japan might be considered significant given the special relationship between the two countries. However, another issue the UN has frequently brought up is the “comfort women” issue concerning wartime sexual slavery, an issue on which in recent years the US and other countries have grown increasingly vocal. The UN Human Rights Committee made the following comments about the “comfort women” issue:

The Committee urged Japan to express a public apology and officially recognize the responsibility of the state over the comfort women issue. It also recommended that Japan educate students and the general public on the issue, including by making adequate references in textbooks (Japan News 2014b)

|

In contrast to the discussion on racial discrimination and hate speech, the US has taken an increasingly critical stand on the “comfort women” issue, especially since US House of Representatives House Resolution 121 was passed in 2007. Like the UN demands above, this Resolution called on the Japanese government to apologise and improve education on the issue. Moreover, in 2012, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was reported to have rejected the euphemism “comfort women” in favour of “enforced sex slaves” (Japan Today 2012). Finally, over Japanese government protests, statues have been erected in a number of US towns by citizen groups in memory of the “comfort women.” For its part, Japan has removed references to “comfort women” in school textbooks in recent years (Asahi Shimbun 2015a; 2015b), while Abe’s August 2015 statement to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII while offering a general apology made only indirect reference to the “comfort women.”4 While a Japan/South Korea deal was announced in December 2015 to “finally and irreversibly” resolve the issue, following heavy US pressure (Japan News 2016a; Yomiuri Shimbun 2015), it threatens to unravel in the face of harsh domestic criticism in both countries. In sum, the “comfort women” issue has become inextricably tied up with patriotism, nationalism, and national pride and as such has become something of a taboo topic in Japan, discussion of which risks raising the ire of conservative right-wing groups. In this respect, there may be parallels with the issue of whaling.

2. Japanese Whaling

|

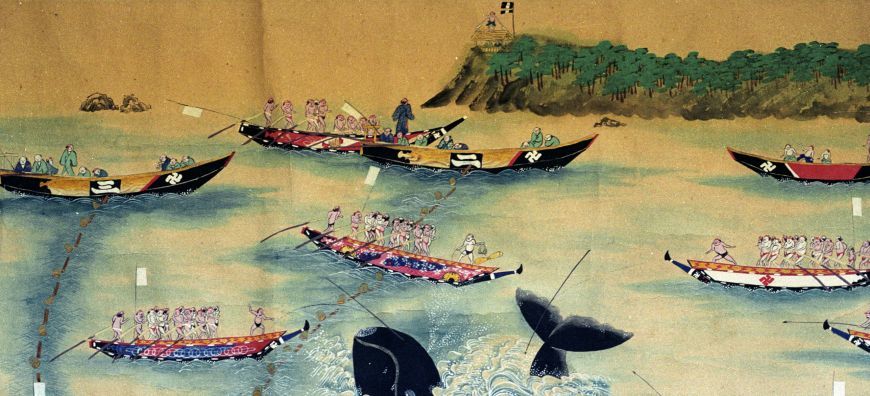

Koshiki horyō makie, Taiji Whaling Museum. |

It is important to understand the history of whaling in Japan if one is to make sense of the Japanese government’s position on whaling today. As Table 1 shows, “active” whaling only began at the start of the seventeenth century, with Taiji, a town of some three and a half thousand in Wakayama, having the longest continuous association. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, “traditional” net fishing, which began in Taiji, was in major decline. The introduction of American and Norwegian technology during this period marks the start of “modern” Japanese whaling and large-type coastal whaling (LTCW). The 1930s also saw the advent of factory-ship (pelagic) whaling in the Antarctic and this continued post-war when GHQ gave permission for Japanese whaling fleets to fish there in order to overcome food shortages. The post-war period saw a free-for-all race to kill as many whales as possible known as the “Whaling Olympics”, something which finally ended in 1987 when the 1982 IWC moratorium came into effect.

|

Steam-powered whaling vessel with harpoon cannon, Sept-Îles (Québec), circa 1900. |

Modern whaling vessel, Nisshin-maru. |

The Japanese government’s position on whaling rests on two key premises which are not always consistent with the historical record: (1) there is a long and deep relationship between the Japanese and whales: whaling is traditional Japanese culture and (2) eating whale is Japanese food culture (Consulate General of Japan (Sydney) 2015).

Table 1: The History of Japanese Whaling

|

Year |

Event |

|

~16 cent. |

① “Passive whaling” (dead or wounded whales caught) |

|

1600 1606 |

② Emergence of “active whaling” (small-type coastal whaling=STCW) Taiji, Wakayama: first organized large-scale whaling (harpoons) |

|

1675 |

③ Net Whaling introduced in Wakayama |

|

~1896 |

Decline of traditional net-whaling/introduction of ④US-style whaling |

|

1897-1908 |

Introduction of ⑤Norwegian-style whaling (explosive harpoons) |

|

1909-1933 f 1911 |

Tōyō company creates whaling monopoly: modern coastal whaling for large-type whales (LTCW) becomes firmly established Riot and burning of Toyo Whaling Station in Same, Aomori |

|

1934-1941 |

⑥ Advent of factory-ship (pelagic) whaling (Antarctic Ocean) |

|

1942-1945 |

Suspension of factory-ship whaling |

|

1946 |

International Whaling Commission (IWC) set up under the terms of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) GHQ gives permission for whaling fleets to fish in Antarctic Ocean in order to overcome food shortages |

|

1951 |

Japan joins IWC |

|

1960 |

Japan becomes the leading whaling nation |

|

1982 |

IWC agrees on moratorium on whaling |

|

1987 |

IWC moratorium comes into effect Japan’s Antarctic “research whaling” begins (JARPA) |

|

1994 |

Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary Created (only Japan votes against) North Pacific “research whaling” begins (JARPN) |

|

2010 |

Australia takes Japan to Hague International Court of Justice (ICJ) |

|

2014 |

ICJ rules Japan’s “research” whaling not scientific, demands halt |

Source: Watanabe (2009: chapter 1 and throughout); Kalland (1992: chapter 2-3, 90)

In emphasising the first premise (the long history of whaling in Japan), the government points to “artefacts from the Stone Age, traditional arts, gravestones and monuments” as well as ancient poetry, folk festivals, and even puppetry as proving the importance of the whale in Japanese society (Consulate General of Japan (Sydney) 2015). In supporting the second premise (whales as a traditional food source), the government argues that the consumption of whale meat “spread widely throughout Japan during the Edo era (AD 1600-1867)” and is eaten in various prefectures across the country (Consulate General of Japan (Sydney) 2015).

Hiroyuki Watanabe in Japan’s Whaling: The Politics of Culture in Historical Perspective, challenges both assertions, (1) questioning the claim that whaling is “traditional Japanese culture” and (2) examining how complex and diverse human-whale relations in Japan have been reduced to the single relationship of killing whales for their meat. On the first point, Watanabe (2009: 48) argues that “traditional” net whaling practiced in a small number of coastal communities5 and modern Japanese whaling based on Norwegian technology are “completely different.” As proof he (2009: chapter 2, 164) cites examples of violent opposition to the spread of the whaling industry in the early 20th century and stresses “the danger in designating any large industry the ‘culture’ of a particular nation-state or ethnic group.” Certainly, given the regional diversity among the mostly remote local whaling communities, the only feasible way to talk about a single national integrated whaling culture is through the existence of a unified whaling industry (Kalland and Moeran 1992: chapter 8). Concerning the second argument, Watanabe points out that the current focus on “whales for meat” stems from the Japanese government’s sponsorship of whaling as a kind of “national industry”, closely bound to imperialism and empire. He (2009: 99) notes that the stimulus for the spread of whale meat consumption from the end of the nineteenth century was “vigorous promotion by the whaling industry” and even then he notes that whale meat only came to be widely eaten as part of the daily diet after 1946 as the result of food shortages. He (2009: 99: 121) concludes that there is no evidence that “the eating of whale meat is part of the traditional food culture of the Japanese race.” Today, there is very little demand for whale meat especially among the younger population: “As domestic consumption of whale meat has plunged in recent decades, some Japanese are sceptical of the worth of spending several million yen each year on research whaling” (Japan News 2014a).6 Nevertheless, the official position is that eating whale meat is an untouchable traditional culture rooted in history:

Asking Japan to abandon this part of its culture would compare to Australians being asked to stop eating meat pies, Americans being asked to stop eating hamburgers and the English being asked to go without fish and chips…whaling in Japan was mainly carried out for the production of meat, and because of strong demand for whale-meat in the domestic market, whaling can still continue to be viable (Japan Whaling Association 2015)

This would suggest that whaling has become a symbol of Japanese national identity, an explanation which might help to explain Japan’s resistance to international pressure. This is examined in detail in the following section.

3. Whale Hunting and International Pressure (Gaiatsu)

Japan’s decision to comply with the 1982 IWC moratorium was certainly influenced by gaiatsu, coming as it did under threat of an international boycott. Japan’s submission to outside pressure was in contrast to the responses of Norway and Iceland which objected to the moratorium and went on to set their own quotas regardless of international pressures; since 1994, Norway has been whaling commercially and Iceland began hunting commercially in September 2006 (Wikipedia 2015). Japan lodged a formal objection at the time but, in a clear case of gaiatsu, this was later withdrawn due to US threats to reduce its fishing quota within US waters (Hirata 2005: 132). In other words, Japan was clearly susceptible to international pressure on whaling at the time of the moratorium.

In the ensuing years, similar threats have come from the US in an effort to persuade Japan to reduce or abandon whaling. For example, Danaher (2002: 116) notes that the US certified7 Japan in 1988, 1995, and 2000 under the Pelly Amendment, though the lack of concrete sanctions probably reflected uncertainty over the legality of such sanctions. Danaher (2002: 116) concludes that such actions show “how the United States has threatened to challenge the pro-whaling stance of the Fisheries Agency, and this is a form of outside pressure or gaiatsu (leverage in international trade).” Ultimately, though, US pressure has been ineffective. As Salles (2014) has argued, Japan is certainly aware that despite being berated by the US at the IWC, America today has far greater concerns than Japan’s whaling practices:

With environmentalist concerns losing ground on the global political agenda, it is difficult to envision any sort of sanctions by the United States if Japan follows through with its intentions. With a growing interest in strengthening military and economic ties with Japan, the U.S. is comprehensibly uneasy about aggravating Japanese nationalist sensitivities; in fact, the Obama administration has openly shown signs that it would support a lift of the moratorium

|

Morishita Joji |

Overall, despite its ostensible rejection of the IWC programme, Japan has in fact been relatively content8 to work within that programme – rather than go the path of Norway or Iceland – since its research whaling has allowed it, to some extent, to circumvent the ban while at the same time deflect criticism by saying its actions conform to international law (Salles 2014). Indeed, Danaher (2002) argues that underlying Japan’s pro-whaling stance are a number of consistent principles which it holds important, namely respect for (1) the legally binding rules of international treaties and (2) science-based management of international resources. “That Japan would sacrifice so much international goodwill for this practice,” notes Danaher (2002: 116), “reflects the principles it is attempting to defend.” For example, Japan frequently points out that the main reason for introducing the moratorium was scientific uncertainty about whale numbers; research whaling is therefore both necessary and legal (BBC News 2008). A central belief that drives the Japanese position is the principle of sustainable use of resources: the minke whale population, for example, is abundant. “It would be good if we were not causing any bad feelings,” deputy whaling commissioner Morishita Joji says, “but sometimes issues of science and principle might be more important than simple issues of emotion” (BBC News 2008). Thus, until recently, legal and scientific principles provided Japan with a large degree of immunity from international pressure.

Japan’s principle-based position came under threat in April 2014 when the International Court of Justice – in a case brought by Australia, one of Japan’s closest friends in the region – ruled that Japan’s “research” whaling was not scientific and ordered Japan to halt whaling in the Antarctic (Japan News 2014d). Specifically, the scientific output of the research program was deemed not proportionate to the number of animals killed (Japan News 2014d). Given Japan’s principle of respecting international law, the Japanese government had little choice but to vow to respect the ruling and promise to abide by the court’s decision. The fact that in recent territorial disputes with its neighbours, particularly China, Japan has consistently presented itself as a country that conforms to the rule of international law made such a response inevitable.9

|

Search results for whale meat sold on Rakuten website, 3 April 2014. |

However, in the September 2014 IWC meet in Slovakia, despite sharp condemnation from US and other representatives, Japan declared its intention to continue whaling for scientific purposes in the Antarctic after reviewing its programme and submitting a new research plan (Japan News 2014a). Although in June 2015 the scientific committee of the IWC raised doubts about the need for lethal sampling, the Japanese government announced that the country’s Antarctic whale hunt would be resumed that year (Japan Times 2015a) and Japanese ships did indeed depart for the Antarctic on December 1st for the first time in two years (Yomiuri Shimbun 2015a). This suggests that legal and scientific principles are not the main driving force behind Japanese whaling as Danaher had suggested.

4. Whale Hunting and Domestic Pressure

As detailed earlier, the “two-level game” model requires assessment of the domestic situation to understand why international pressure does or does not work. In Japan’s case, the weakness of the domestic anti-whaling lobby means that foreign pressure has difficulty resonating within the country. “Foreign demands on Japan to stop whaling,” writes Danaher (2002: 116), “are not aligning with any powerful domestic constituencies, whereas the domestic political pressure on Japan to continue whaling is great.”

In Japan, the pro-whaling lobby is extremely strong while the anti-whaling lobby is markedly weak. The key pro-whaling groups are the Fisheries Agency10 (Suisanchō), the pro-whaling parliamentary groups (Hogei Gi’in Renmei and Hogei Taisaku Gi’in Kyogikai),11 and the fishing industry. These voices are supplemented by semi-governmental pro-whaling NPOs (such as the Japan Whaling Association or JWA, and the Institute of Cetacean Research or ICR), and a sympathetic media.12 In contrast, anti-whaling voices are limited to a small number of environmental NGOs (such as Greenpeace Japan13 and Elsa Nature Conservancy) while the Environmental Ministry (EA) remains silent on the issue.14 As Danaher (2002: 111) notes, “there is no substantial anti-whaling coverage in the mainstream news media…the numbers of people willing to be outspoken against whaling are very limited.” Unsurprisingly, then, public opinion is firmly in favour of whaling, though this has begun to change. In an April 2014 opinion poll, while 23.6% disagreed that Japan should continue whaling against 45.5% who said they agreed, the latter was down by 11.7% since June 2013 (Yomiuri Shimbun 2014). A 2012 poll found 27% of respondents supporting whaling and 11% opposed, with younger respondents more likely to be opposed (The Daily Beast 2013). While the number of “don’t know’s” has remained consistently high, support does seem to be eroding compared to past surveys.15 It is possible that an increasingly popular whale-watching industry and a growing engagement in whale rescues (Danaher 2002: 113-114) have influenced public opinion.

It might be natural to assume that the drive for profits underlie the dominance of the pro-whaling lobby in Japan. However, the commercial viability of the whaling industry is highly questionable. “The Japanese whaling industry, which employs only a few hundred people and generates at best marginal profits,” writes Hirata (2005: 130), “is too small and weak to influence government policy.” In fact, the government spends large amounts of taxpayers’ money to subsidise stockpiles16 of whale meat which few Japanese want to eat. In a 2009 report, for example, the World Wildlife Fund (2009) found that Japanese subsidies for whaling had amounted to US$164 million since 1988. However, the existence of such subsidies is generally not well known in Japan. For example, in October 2012 when Greenpeace Japan publicised the fact that the Institute of Cetacean Research was provided with 2.28 billion yen ($29 million) in financial assistance from the earthquake reconstruction fund to increase security for the whaling fleet, it made headlines in foreign media outlets (e.g. The Guardian 2011; USA Today 2011) but received little attention in the major Japanese dailies.17

Given the amount of subsidies detailed above, it is possible to question Hirata’s contention that financial issues are irrelevant. Kagawa-Fox (2009) concurs, arguing that whaling policy is driven by “vested” interests seeking financial advantage, what she calls the “Whaling Iron Triangle”: the Fisheries Agency, the ICR, and the Japan Fisheries Association (JFA), which represents Japan’s fishing industry as a whole. Certainly, the fishing industry does have influence above and beyond its actual impact on the economy; nevertheless, it is not profit that keeps whaling afloat in Japan but more the fact that the end of whaling would mean a decline in the political clout of the Fisheries Agency (Hirata 2005: 146).

|

Media event publicising serving whale cuisine to MPs in cafeteria, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 18 November 2014. |

In sum, domestic support for whaling is not pushed so much by economic demand as by political ideology. “Whaling in Japan is essentially not driven by demand by gourmands and specialty restaurants,” observes Salles (2014), “but by the Japanese government itself, which finances and subsidizes the supply of whale meat.” Specifically, whaling in Japan is largely driven by the Fisheries Agency which has skillfully re-defined it as “a policy issue of national interest to protect its own interests from foreign pressure” (Danaher 2002: 116). By building the whaling issue into a symbolic one of “traditional culture, national pride, food security and sovereignty” (Danaher 2002: 116) it has in effect insulated whaling from criticism and largely silenced its domestic critics. In other words, as Watanabe suggested earlier, whaling has become a conservative ideological project of the state, closely tied with national identity. Kalland and Moeran (1992: 194-5) suggest that one of the reasons this re-definition has been so successful is that, in the post-war period at least, there has been a lack of national symbols acceptable to all Japanese: “In this vacuum of national symbols, whale meat has provided a particularly powerful image,” they write, “…and the whaling issue serves to strengthen the much cherished Japanese myths about their identity (nihonjinron), which itself helps fuel one form of Japanese nationalism.”

|

Revival of whale school lunch served by restaurant in Chiba Prefecture. |

The potency of the whale as a unique national symbol has heightened in recent years as Japanese politics has taken on a more conservative, even nationalistic bent. The (first) Abe administration’s 2006 reform of the fundamental law on education marked the beginning of a push to teach patriotism and tradition in schools and to foster Japanese citizens who “love their country.” One relevant example are the moves since 2005 to put (heavily subsidised) whale meat back on school lunch menus in order to teach children about the school lunches “Japanese schools have served in the past” – and perhaps also to stimulate demand for whale meat in the present (Japan Times 2010). In 2013, the Fisheries Agency set a goal of doubling its distribution of whale meat to school-lunch programs (The Daily Beast 2013).

5. Conclusion: International Pressure as Counter-Productive

In November 2012 in Shibuya, Tokyo, a demonstration against the hunting of whales and dolphins was organised by The Society to Protect Marine Mammals (Kaiyō Honyūrui o Mamoru Kai), a Japanese grassroots group. It was apparently the first ever locally-organised demonstration (an earlier September rally apparently broke up after it was disrupted by right-wing counter protesters).18 A counter-demonstration was held at the same time sponsored by an organisation roughly translated as “Japanese National’s Group denouncing the anti-Japanese group Sea Shepherd” (Nihon Sabetsu Shūdan Sea Shepherd o Kyūdan suru Kokumin no Kai), with support from Zaitokukai, a group known for organising the anti-Korean hate-speech protests mentioned in section one. The Zaitokukai website carried the following details:

Throw Sea Shepherd out of Japan! An Angry Counter Demonstration against the Anti-Dolphin Hunting/Anti-Whaling Protest in Shibuya

In support of environmental terrorist group Sea Shepherd’s “Global Anti-Dolphin Hunting/Anti-Whaling Movement”, an SS [Sea Shepherd]-type demonstration in Shibuya, Tokyo will be held. We will hold a counter demonstration to show our anger as Japanese towards Westerners who should be ashamed at their discrimination of [our country’s] Food Culture” (Zaitokukai 2012, author’s translation)

|

Image from video of protest by Nihon Sabetsu Shūdan Sea Shepherd o Kyūdan suru Kokumin no Kai, Shibuya, 24 November 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H-63pwwwaJ0 |

One of the salient points here is how the issue has been framed as Japan vs. the West, specifically the Japanese as victims of Western discrimination, imperialism, and “Japan bashing.” Consequently, the demonstration was portrayed as driven by a foreign group when in fact it was organised by Japanese citizens and more than half of activists were Japanese. The message that whaling is inherently tied with the Japanese race was personified by one of the placards which read, “Killing the practice of whale hunting is the same as killing the Japanese people” (The Daily Beast 2013). Other placards (written in English) attacked “white supremacy” and “white pigs.” The ideology of race has thus become the central feature of recent pro-whaling demonstrations. For example, in February 2010, protests against Sea Shepherd’s “racially motivated attacks”19 on the Japanese whaling fleet were held in front of the Australian Embassy. More recently, in April 2014, demonstrations outside the Australian Embassy labeled Australia as a “racist country” and criticised “white westerners” destroying Japanese whaling culture. In sum, the issue of whaling has been portrayed by its Japanese supporters as one of racial prejudice, discrimination, and persecution by white people against the Japanese race.

The prominence of the Sea Shepherd name in the anti-whaling discourse reflects the rising profile of the US marine conservation group and its heightened harassment of the Japanese whaling fleet. In 2012, a US court granted an injunction, in a case brought by the ICR, against Sea Shepherd, ordering it to cease its “dangerous protests”; in 2014, the group was found to be in contempt of court and in June 2015 it paid $2.55 million in damages due to its “continued obstruction of whaling vessels” (Japan Times 2014; 2015e). In this way, Sea Shepherd’s actions have become a focal point for the pro-whaling voices in Japan. As Ishii (2011), Hirata (2005: 149), and Miyaoka (2004: 95) have argued, such militant actions have “back-fired” by fuelling nationalist sentiments and boosting the demand for whale meat, thereby prolonging the life of the whaling industry. As Blok (2008: 41) asserts, the pro-whaling movement is essentially a counter-movement, a reactive moral challenge “to the identity claims espoused by the global anti-whaling community.” The growing polarisation of the debate, with “Western” moral and green arguments being matched in emotional intensity by the Japanese emphasis on national pride and racial identity, make prospects for a compromise more distant than they have ever been. A first step towards reconciliation might be, perhaps non-intuitively, to dial down international pressure against Japan.

Chris Burgess took his PhD at Monash University, Melbourne. He is a Professor at Tsuda Juku University (Tsuda College), Tokyo, where he teaches Japanese Studies and Australian Studies. His research focuses on migration, globalisation, and multiculturalism in contemporary Japan. Recent work includes papers on “Cool Japan“, global human resources, and civil society. . – See more here.

Related articles

- David McNeill, Whaling as Diplomacy

- David McNeill and Taniguchi Tomohiko, A Solution to the Whaling Issue? Former MOFA spokesman speaks out

- David McNeill, Campaigners fight to clear “Tokyo Two” in Whaling CaseExtraordinary treatment of two Greenpeace activists creates worldwide protests

- Mark Brazil, Wild Watch: Blood in the Water in Hokkaido’s Sea of Okhotsk

- Kate Barclay, Fishing. Western, Japanese and Islander Perceptions of Ecology and Modernization in the Pacific

- David McNeill, Harpooned. Japan and the future of whaling

- David McNeill, Japan and the Whaling Ban: Siege Mentality Fuels ‘Sustainability’ Claims

- David McNeill and Ian Mather, Japan and the Intensifying Global Whaling Debate

- Michael McCarthy, 20 Years On and Whales are Under Threat Again: Japan, Norway, Iceland

Bibliography

ABC-News

2010 ‘IWC rejects commercial whaling bid’. (June 24).

Asahi Shimbun

2015a ‘Publisher to drop ‘comfort women,’ ‘forcibly taken away’ from high school textbooks’. (Jan. 10).

2015b ‘EDITORIAL: LDP should not meddle in school textbook selection process’. (Aug. 24).

BBC News

2008 ‘Whaling: The Japanese position’. (Jan 15).

Blok, Anders

2008 ‘Contesting Global Norms: Politics of Identity in Japanese Pro-Whaling Countermobilization’. Global Environmental Politics 8:2 (May 1), pp.39-66.

Butterworth, Andrew, Philippa Brakes, Courtney S. Vail, and Diana Reiss

2013 ‘A Veterinary and Behavioral Analysis of Dolphin Killing Methods Currently Used in the “Drive Hunt” in Taiji, Japan’. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 16:2, pp.184-204.

Cabinet Office

2001 ‘Hogei Mondai ni kansuru Yoron Chōsa (A Survey about the Whaling Issue)’.

Consulate General of Japan (Sydney)

2015 ‘The Japanese Government’s Position on Whaling’.

Danaher, Mike

2002 ‘Why Japan Will not Give up Whaling’. Pacifica Review 14:2 (June), pp.105-120.

Fisheries Agency

2011 ‘Japan’s Opening Statement to the 63rd Annual Meeting of the International Whaling Commission’.

Hirata, Keiko

2005 ‘Why Japan Supports Whaling’. Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy 8:2-3 (April 1), pp.129-149.

2002 Civil Society in Japan: The Growing Role of NGOs in Tokyo’s Aid Development Policy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ishii, Atsushi, and Ayako Okubo

2007 ‘An Alternative Explanation of Japan’s Whaling Diplomacy in the Post-Moratorium Era’. Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy 10:1 (March 16), pp.55-87.

Ishii, Atushii

2011 Kaitai Shinsho: Hogei Ronso (Anatomy of the Whaling Debate). Tokyo: Shinhyoron.

Japan News

2016a ”Comfort Women’ Deal Reached’. (Dec. 29), p.1.

2016b ‘Japan Signs Minamata Treaty’. (Feb 4), p.3.

2015 ‘Abe Cites Apology, Aggression’. (Aug 15), p.1.

2014a ‘Japan Faces Waves of Criticism for Plans to Continue Research Whaling Program’. (Sept 19), p.1.

2014b ‘UN Rights Panel Seeks Penalty for Hate Speech’. (July 26), p.3.

2014c ‘UN Panel Urges Nation to Regulate Hate Speech’. (Aug. 31), p.2.

2014d ‘ICJ: Japan’s Whaling not Scientific’. (April 1), p.1.

Japan Times

2015a ‘Whale Hunt to be Resumed this Year, Official Says’. (June 22).

2015b ‘As whale meat consumption falls, efforts afoot to boast its merits’. (June 26).

2015c ‘Whale meat arrives in Osaka via new Arctic route to avoid protesters’. (Aug 31).

2015d ‘Japan’s whaling hiatus sees meat stocks hit 15-year low’. (July 19).

2015e ‘Sea Shepherd to pay $2.55 million in damages as Japan’s research whaling set to resume’. (June 10).

2014 ‘Sea Shepherd protesters found in contempt of court for anti-whaling campaign’. (Dec 20).

2010 ‘Whale meat back on school lunch menus’. (Sept 5).

Japan Today

2012 ‘Clinton says ‘comfort women’ should be referred to as ‘enforced sex slaves”. (July 11).

Japan Whaling Association

2015 ‘Questions and Answers’. (Aug 11), (http://www.whaling.jp/english/qa.html#01_03).

Kagawa-Fox, Midori

2009 ‘Japan’s Whaling Triangle – The Power Behind the Whaling Policy’. Japanese Studies: The Bulletin of the Japanese Studies Association of Australia 29:3, pp.401-14.

Kalland, Arne, and Brian Moeran

1992 Japanese Whaling: End of an Era? Oxford and New York: Curzon Press.

Miyaoka, Isao

2004 Legitimacy in International Society: Japan’s Reaction to Global Wildlife Preservation. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mulgan, Aurelia George

1997 ‘The role of foreign pressure (gaiatsu) in Japan’s agricultural trade liberalization’. The Pacific Review 10:2 (Jan 1), pp.165-209.

News.com.au

2013 ‘Japan ‘will never stop whaling’, Japanese fisheries minister says’. (Feb 26).

Nikkei Keizai Shimbun

2012 ‘”Mizu Fukure Hosei” Manaita Fukkō Yosan no Ryūyō (“Overflowing Supplementary Budget” Invited Misappropriation of Reconstruction Funds)’. (Oct 17).

Pekkanen, Robert

2006 Japan’s Dual Civil Society: Members Without Advocates. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Salles, Joaquim Pedro Moreira

2014 ‘Can International Pressure really keep Japan from Whaling’. (April 29).

Schoppa, Leonard J.

1993 ‘Two-level Games and Bargaining Outcomes: Why Gaiatsu Succeeds in Japan in some Cases but not others’. International Organization 47:3 (Summer), pp.353-86.

The Daily Beast

2013 ‘I’ll Have the Whale, Please: Japan’s Unsustainable Whale Hunts’. (May 2).

The Guardian

2014 ‘Japan’s biggest online retailer, Rakuten, ends whale meat sales’. (April 4).

2011 ‘Japan whaling fleet accused of using tsunami disaster funds’. (Dec 7).

The Japan News

2015a ‘Japanese Associations’s Capitulation to International Pressure over Dolphins Inevitable (Editorial)’. (May 23), p.4.

2015b ”Cruelty’ Charge Bewilders Taiji’. (May 27), p.2.

Tokyo Shimbun

United Nations

2001 ‘Press Release, CERD Committee’. (March 20).

USA Today

2011 ‘Japan using tsunami funds for whaling hunt’.

Watanabe, Hiroyuki

2009 Japan’s Whaling: The Politics of Culture in Historical Perspective (translated by Hugh Clarke). Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Watson, Paul

2006 ‘The Truth about “Traditional” Japanese Whaling’. (June 27).

Wikipedia

2015 ‘International Whaling Commission’.

World Wildlife Fund

2009 ‘Norway, Japan prop up whaling industry with taxpayer money’. (June 19), (Norway, Japan prop up whaling industry with taxpayer money).

Yomiuri Shimbun

2015 ‘Beichōkan, Nikkan Kaizen Unagasu (US Secretary of State Urges Japan and Korea to Improve [Ties])’. (May 19), p.2.

2015a ‘Chōsa Hogei Gyakufū no Funade: 2 nen buri Hokaku Hanpatsu Hisshi (Research Whaling, Ships Set Sail against an Unfavourable Wind: Opposition to Catch Inevitable after two year Hiatus)’. (Dec. 1), p.38.

2015b ‘Imin ni Hantai 61% (61% against Migrants)’. (Aug 26), p.12.

2014 ‘Ōbei kara Hihan 「Sansei」 Ha Genshō (Criticism from the West, number of those who “agree” with whaling falls)’. (Sept 17), p.6.

Zaitokukai

programs (The Daily Beast 2013).

Notes

An earlier version of this paper appeared in the Tsuda College journal Kokusai Kankeigaku Kenkyu (The Study of International Relations, Tsuda College) No. 42 (2015).

The new killing methods have not been evaluated highly in scientific terms. For example, Butterworth et al (2013) conclude that the new methods “would not be tolerated or permitted in any regulated slaughterhouse process in the developed world.”

Outside pressure (and exchanges and cooperation between groups) strengthened considerably following the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People in 1993 and the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People starting in December 1994.

“We must never forget that there were women behind the battlefields whose honor and dignity were severely injured” (Japan News 2015).

For most of these small coastal communities the history of whaling is not very long. For example, since 1987 Japan has pushed the IWC for small-type coastal whaling (STCW) practiced in Abashiri, Ayukawa, Wadaura, and Taiji to be given rights similar to aboriginal subsistence whaling. However, aside from Taiji whaling was not introduced in these communities until the twentieth century and whaling remains of limited importance to the towns as a whole (Kalland and Moeran 1992: chapter 2). Nevertheless, and despite international opposition, Japan’s small type coastal whaling “remains as a priority issue for Japan”, something which was re-emphasised following the devastation suffered in Ayukawa following the March 2011 tsunami (Fisheries Agency 2011).

Today, annual whale meat consumption in Japan is around 4,000-5,000 tons a year, a sharp fall from the peak of more than 200,000 tons in the early 1960s (Japan Times 2015b).

In this context “certified” means that the US Secretary of Commerce “determines that the nationals of a foreign country are diminishing the effectiveness of an international fishery conservation program” and officially reports (=certifies) this fact to the President.

Of course, Japan is vocal in calling for lifting the moratorium allowing it to resume commercial whaling and it has consistently tabled such bids at IWC meets. For example, the 2010 IWC Conference in Morocco rejected Japan’s proposal that it be allowed to resume limited commercial whaling if it agreed to cut its scientific quota in the Southern Ocean (ABC-News 2010). However, Ishii and Okubo (2007) argue that Japan’s real goal is actually the continuation of “research” whaling and that calls to resume commercial whaling are simply a smoke-screen.

The ICJ ruling also pushed online retailer Rakuten to end all sales of whale and dolphin meat, suggesting that while international pressure may have little effect on the Japanese government it can influence those Japanese firms with a global presence (The Guardian 2014).

Whales, of course, are not fish but historically they have been treated as such: in the past they were referred to as isana or “brave fish”. Even today, the character for whale contains the fish radical.

Whaling is supported by all Japanese political parties. Japan’s Green Party (Midori no Mirai) has no national political presence.

Greenpeace Japan, established in 1989, has much less visibility or voice than it does in many other countries. Most NGOs/NPOs in Japan are small, local ones with few or no employees; Japan has few large, professionally managed national organisations, such as Greenpeace. Pekkanen (2006) refers to this as Japan’s “dual civil society” and highlights strict state oversight and regulations as one explanation.

Hirata (2005: 129) sees whaling as a puzzling exception in a country that has been a key player in various global environmental initiatives. The EA’s silence is even more surprising given its promotion of “The Minamata Convention on Mercury”, adopted at a UNEP conference in Kumamoto in 2010 and ratified by Japan in February 2016 (Japan News 2016b). The Convention calls for new controls and reduction of the use of mercury worldwide, to “prevent it from polluting the environment and damaging the health of the world’s population” (The Daily Beast 2013). Whale meat contains high levels of mercury.

Although the Japanese government frequently takes public opinion polls on a variety of issues, it has not asked if people were for or against whaling since 2001. In that year, 75.5% expressed support for this question: should countries be able to hunt whales “in a sustainable fashion if based on science”? (Cabinet Office 2001). Most questions in the survey were actually about people’s knowledge of the IWC and Japan’s whaling culture, such as, “Did you know Japan has used whales since the Jomon period?”

As well as stockpiling meat from research whaling (known as “by-product”) which Japan is allowed – indeed obliged – to do under IWC rules, Japan also imports whale-meat from Norway and Iceland. As of May 2015, inventories were at 1,157 tons, the lowest since March 2000, partly as a result of the ICJ ruling and Japan’s suspension of its Antarctic whaling (Japan Times 2015d). To alleviate this “shortage”, a ship carrying some 1,800 tons of whale meat from Iceland arrived in Japan at the end of August 2015 after an almost three-month journey (Japan Times 2015c).

Stories were carried in the Tokyo (2012) and Nikkei (2012) newspapers. Although the north-eastern coast, including the coastal whaling town of Ayukawa, was indeed devastated by the tsunami, criticism was centred on use of the fund for something other than recovery efforts.

About 70 protestors (including 40 Japanese activists) were faced by a similar number of counter-demonstrators. For more information see here.

Although Sea Shepherd has taken pains to point out that it has also taken action against Canadian sealers and other non-Japanese groups, racism is not entirely absent from the Sea Shepherd rhetoric: “The brutal killing of whales has become an icon for the Japanese identity. This is not unusual. Japan has always closely identified with blood and slaughter. From the decapitations by the Samurai upon innocent peasants to the suicidal insanity of the Kamikaze, violence and self destruction have been a part of Japanese culture” (Watson 2006).