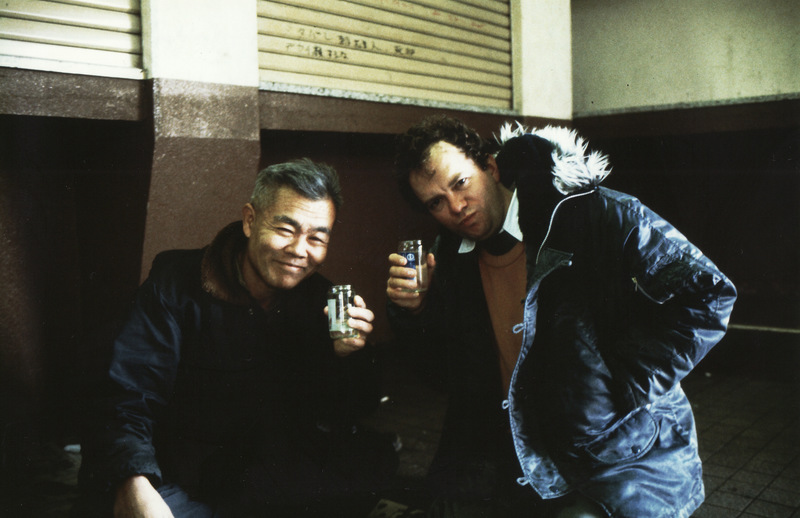

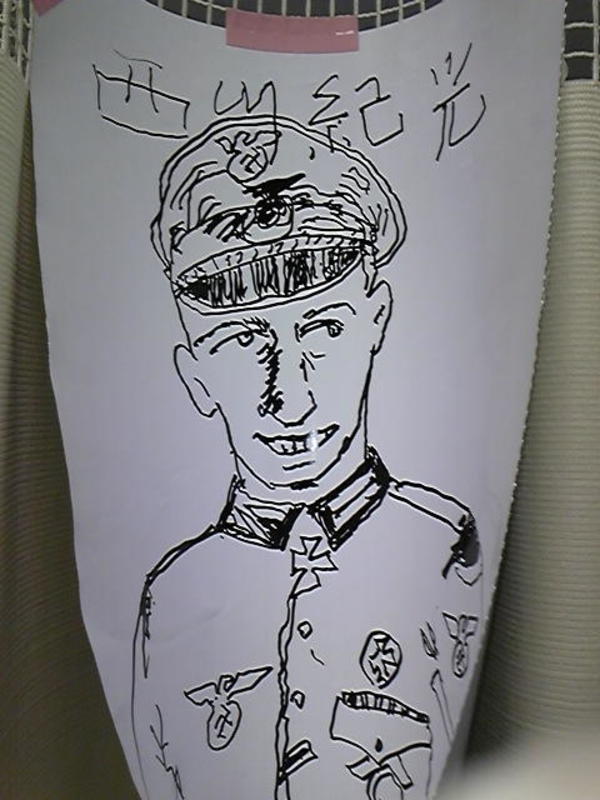

The first time I met Nishikawa Kimitsu was on October 20, 1993, at 6 o’clock in the morning in front of the casual labor exchange in Kotobuki, the notorious Yokohama slum district. He was struggling to get a day’s work on a building site in Yokohama. When I told him I was doing fieldwork for a doctorate in social anthropology, he immediately asked me if I was a Malinowskian functionalist or a Levi-Straussian structuralist. He had a copy of Levi-Strauss’s Le Regard Eloigné in his pocket. He lived in a run-down doss-house, in the filthiest room I have ever seen, with cobwebs, cockroaches, empty sake bottles, overflowing ashtrays and cigarette burns on the lank and greasy tatami.The room was stuffed with teetering piles of heavyweight scholarly monographs and intellectual magazines, and the walls were graffiti’d with his obsessive pictures of Nazi concentration camp guards.

|

Nazi officer, drawn by Kimitsu |

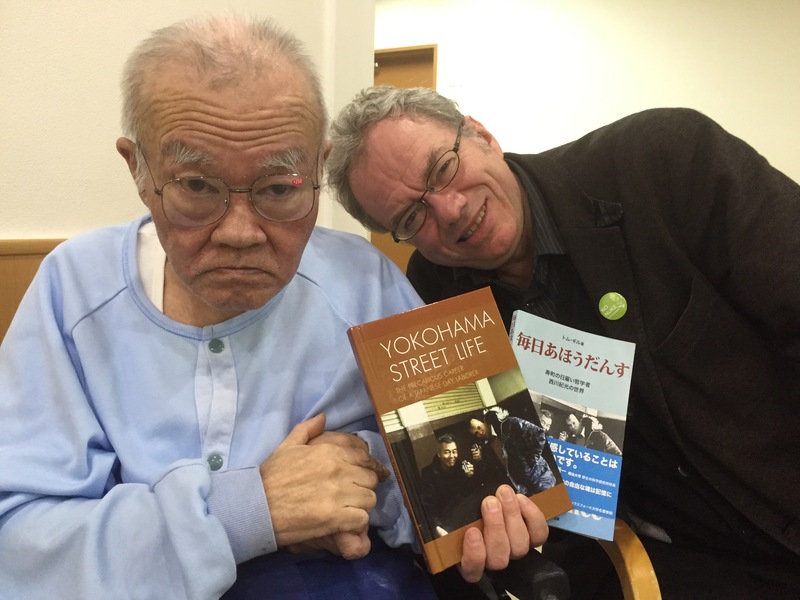

It was the start of a friendship which continued intermittently for over two decades, culminating in my book, Yokohama Street Life: The Precarious Career of a Japanese Day Laborer, recently published by Lexington Books in the US and UK. It is a one-man ethnography of Kimitsu, who recently played out the last few months of his life in the dementia ward of a hospital in Yokohama. Nobody around him knew that one of the inmates was so well read that I was repeatedly obliged to scour the Meiji Gakuin library to look up references during the months I was interviewing him to write the book.Nor did they know that he was also an artist – the book contains quite a few of his unique sketches and cartoons.

As well as Kimitsu’s life and thoughts, the book also discusses the recent history of yoseba/doya-gai (street labor markets and skid row districts in Japan). And in surveying Kimitsu’s final years surviving a pair of strokes after a lifetime of alcoholism, chain smoking and hard work, with the aid of livelihood protection (seikatsu hogo), it casts some light on the Japanese welfare system, showing how marginal men who traditionally were left to die in the street are now cared for rather better.

Shortly after the book was published, Kimitsu passed away. In choosing the extracts from the book that follow, I have focused mainly on Kimitsu’s childhood and youth, mostly based on interviews conducted in 2007. Afterwards, I append a few episodes from the end of Kimitsu’s life. Consider them a postscript to the book of his life.

|

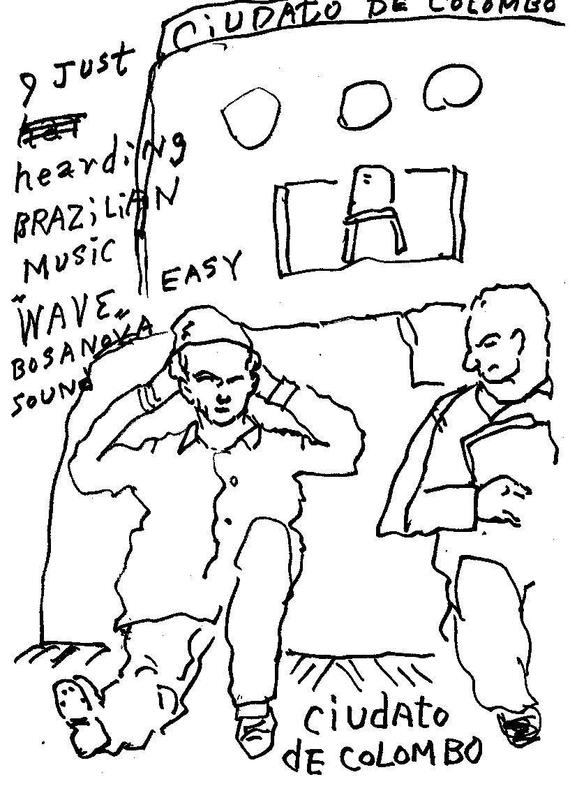

Nishikawa and Gill, Kotobuki Labor Center, 1994 |

Extracts adapted from Yokohama Street Life: The Precarious Career of a Japanese Day Laborer

My name is Nishikawa Kimitsu. I was born in Kumamoto city in 1940, the 15th year of the Showa era. Others born in that year include John Lennon, Al Pacino, Peter Frampton, Raquel Welch, Jack Nicklaus and the great sumo champion, Taihō.

My parents gave me a very pompous name. They called me “Norimitsu” (紀光), meaning something like, “light of the century.” That’s my formal name in the family registry. Those were nationalistic times – 1940 was celebrated as the 2600th anniversary of the founding of the nation by emperor Jimmu, and the “nori” in Norimitsu is also the final character of the Nihon Shoki, or Chronicles of Japan (日本書紀), which was compiled in the 8th century and was supposed to have all the history about Jimmu and how he was the direct descendent of the sun goddess Amaterasu. It was a dark age. I never liked my name. When I was young, a fortune teller told me it was an unlucky name, because the character kawa (川) in Nishikawa had three strokes and the character nori (紀) in Norimitsu had nine strokes, and three plus nine equals twelve, which signifies a bad life, easily getting neurotic, likely to have difficulty in getting married, etc., etc.

The nishi (西) in Nishikawa is a problem too. It means ‘west’, and in Buddhist cosmology all bad things come from the west. The realm of the dead is always in the west. In English “gone west” means somebody died, right? The Dalai Lama’s looked into this, you know, and I too am interested in this kind of thing.

Home to me is Yamaga, in Kumamoto prefecture, Kyushu. I was born in Kumamoto city, but I was evacuated to Yamaga because of the war. It’s a small town on a plain in the middle of the mountains. The other day I made a trip back to Yamaga. After I turned 65, I suddenly started thinking about my hometown, and since then I’ve been back about five times. I drink too much, and death is catching up on me now, so it occurred to me that I should go back to my home country one time, see my big sister, see the old mountain peaks of my youth, get a look at that beautiful countryside. Then I could go back to Yokohama and die in peace. It wouldn’t do to die without seeing those places again.

It’s quite an operation, getting back to Kyushu from here. It’s about 500 miles. I used a special way of travelling I call the “gun” (teppō). It means buying a cheap ticket and then using it to fly a long distance like a bullet from a gun. I bought a ticket for a couple of hundred yen at Ishikawachō station. I got about as far as Shizuoka with that, on a slow train. They have far fewer ticket inspections than express trains. Then I chose a little unmanned station and got off there. There was no one around so I slept on the platform. Then I bought some saké from a vending machine, bought myself another 200 yen ticket, and this time I got as far as Toyohashi. I told the ticket collector there that I’d got drunk and lost my ticket, and managed to carry on as far as some little unmanned station in Gifu prefecture, where I spent the night and then bought another little ticket. This time I got as far as Osaka. I told them I’d fallen asleep and missed my stop at Takatsuki, had a few drinks and lost my ticket. There are lots of people like that in Osaka, so they’ll believe you right away.

Riding the gun. When the ticket inspector comes along, you just go to the toilet, or start coughing violently or making like you’re about to throw up, so that the inspector doesn’t want to get too close to you. You don’t want to ride the gun in a suit and necktie. But with this kind of blue worker’s overalls, you’re generally OK. It’s no good being sober. So long as you’re good and drunk, the ticket inspector doesn’t come near you. Call it the mysterious power of alcohol, if you like.

Anyway, the whole point of riding the gun is to avoid paying a substantial fare. There’s no fun in paying out big fares, right? Because your adversary is the representative of authority – and you have to resist authority.

It was my first visit to Yamaga for 30 years, and the place had changed quite a bit. But the fundamental character of the place hadn’t changed. There’d been no revolution. They hadn’t suddenly achieved enlightenment down there. It was just that my sister had got older, and a lot of my old buddies had died. The landscape had changed a bit, but the river was still running. The familiar peak of the Fudōiwawas still there.

I went to look at my old high school. I kept thinking of that poem by Charles Lamb, ‘The Old Familiar Faces’: “Ghost-like I paced round the haunts of my childhood… Seeking to find the old familiar faces… All, all are gone, the old familiar faces.” Lamb also went back to his school after several decades. And there was no one he knew in the grounds of the school. I was very moved when I read that poem. It was the same for me. In the old days I had lots of friends, but now I couldn’t find one. Of course I couldn’t. I first read that poem of Lamb’s a long time ago, and I always thought it was a terrific work of nostalgia. I’ve always thought it has a Buddhist scent to it.

Yamaga itself really is a ghost town. It feels just like a movie set: the townscape is there, but there are no people. It’s a hot-spring town, in the volcano zone. In the old days they had this giant bath, called the ‘Thousand Person Bath’ – admission was 2 yen. There were lots of people there, children running around all over the place, young men and women flirting with each other. But now there’s nobody there. You’d not be surprised if a few ghosts showed up. It’s a zombie town. Why do politicians let this kind of thing happen, I wonder? Do they reckon that little rural villages just don’t matter? Since you can import your agricultural produce from America. And your timber from Indonesia. Just use the country for golf courses. I’d rather be in Kotobuki. At least this town is still alive. Down in Yamaga you never know what kind of zombie might suddenly come out from somewhere.

|

Kimitsu in his room, 2007 |

My earliest memory is from when I was three. We were still living in Kumamoto. I could see the railway tracks on the far side of the Tsuboi river. It was part of the national railways. There were steam trains running along it, and I enjoyed wondering where on earth they might be going.

When I was four or five, we evacuated from Kumamoto to Yamaga. It happened very suddenly. A truck came, and we put all our stuff on it. “You – hop on board.” Like that. “Is it really OK to do things so suddenly?” I wondered. Well, I could hear the sound of falling bombs occasionally, so it was only natural to evacuate from the city to the country. I guess it was 1945, and the American air raids were gradually getting more intense. In April there was a big raid on Kumamoto city and about 500 people were killed. So it’s just as well we evacuated to Yamaga. My father made the right decision there. My father was very smart (Kimitsu sheds a tear). I want to be like my father. There’s a lake near Kumamoto called Lake Ezu. My dad used to go boating there, and he looked very dashing. He was good at running the marathon too. A sporting person. He was a banker. He managed to get into Yasuda Bank with a leg-up from his own dad.

I’m not good at talking about my mother. I was effectively separated from her from the age of three. We were still living in the same house, but my relationship with my mother gradually got weaker. Like being weaned from the breast. It’s the same in Europe, right? Role playing, division of labor. I was brought up by my grandparents. They meant a lot to me, my granddad and grandma. In families these days the grandparents nearly always live separately, right? That’s all wrong. You can’t receive the wisdom of the senior generation. In my case I was very lucky to have my grandfather with me.

My grandfather didn’t last long before he died though. He was a right-wing person and very patriotic, so he was deeply affected by defeat in the war. After we lost the war, he walked all the way from Kumamoto to our house in Yamaga. He had a walking stick, and he carried all his luggage on his back. He was all messed up, and crying out for help. He died about three days later.

I well remember the day the war ended. That day, there was the bluest sky I’ve ever seen. It really moved me, as a kid. It was incredibly quiet. You could have heard a pin drop. And the sky was blue. Pure blue. We didn’t have the kind of atmospheric pollution you get nowadays. There were no American bombers. All thanks to the war ending.

I didn’t hear the Emperor’s surrender broadcast, but I read it later in a weekly magazine. In those days magazines consisted almost entirely of war photographs. A brilliant attack by the German Panzers and so on. Asahi Graph was full of German propaganda. Later, when I went to high school, I learned about Auschwitz for the first time in the pages of the Sunday Mainichi.

Before the war, my father owned a 9.5 millimeter projector. It was made by the French company Pathé, and he had a few films, slapstick comedies with Charlie Chaplin, that kind of thing. He would put on film nights for the neighbors. In those days there were still lots of houses that didn’t even have a radio, so this was fantastic. We also watched newsreels. We’d see German soldiers riding on Panzer tanks as they took over Europe. In these propaganda movies the German soldiers were always great big blond guys. After the war, a lot of American soldiers came to Kumamoto, and a lot of them were big blond guys as well. I was only five, so I didn’t understand the difference between German soldiers and American soldiers. To me it was like these blond supermen who conquered Europe had now come and conquered Japan.

When the war ended, I was five years old and attending kindergarten. I hated kindergarten. I was bullied by one of the older kids. I can still remember his name: Toyoda-kun. If I ever meet him again, I’d like to give him a good beating. Then I went to elementary school. I hated that too, except for the first year, which wasn’t too bad. We had the same textbooks that they used during the war, but all the really patriotic bits had been deleted with black ink. Nearly all the teachers were just back from the army, and they were very violent. Kawahara Yasunobu sensei, for instance. Just a tiny bit of chatting in class and he’d give you a stinging slap. It felt like prison. He’d pull the girls’ hair too. The elementary school was a postwar battlefield.

I hate authority. Authoritarian teachers, priests etc. Christ or Buddha would never have behaved the way they do. Real gods are not authoritarian.

The teachers often spoke about the war. One of them had been wounded. He’d lost a little finger. He often told us boring war stories. “Here we go again,” I’d think to myself. “We lost, but he still makes such a big deal of it.” I can sort of understand what we went to war for, but some of the things we got up to… kidnapping Koreans to pressgang them into the war effort and so on… were all wrong.

I had no dream for the future. It was all I could do to stay alive from one day to the next. Every day, a dance of fools. No time-outs. Wandering around and bumping into stuff. Economic problems in the background. A deer about to be eaten by a lion. No leisure to think about the future. I was living like a wild animal. The life of a brute.

However, since my family was concerned about appearances, I did go to senior high school although we couldn’t really afford it. After all, I was the oldest son of a banker. If someone was born into the kind of poverty I experienced and had a navvy for a dad and a bar girl for a mum, they’d probably end up being a yakuza or a criminal. Of course there’s a genetic element to it as well. You’d end up playing on the center court at the Old Bailey. Like the hero of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. If you choose a bad road, then punishment surely awaits you.

I graduated senior high school in Showa 34, that’s 1959. When I left school I thought I’d have to earn a salary somehow, so I joined the Self-Defense Force. It was interesting. The rules were strict, but all the people who went in had lots of personality defects – just like me – so we got on well. Fellow samurai. A society of knights. Like the crusaders. It’s because there are no women there that such an ideal society can be created, even if just for an instant. When women come in everything gets spoiled. I’m not talking about gays. But I do think there’s a need for beauty among fellow men. However, the war was long over, and there was no particular prospect that we’d have to do any real fighting. So we felt more like boy scouts than soldiers. Or some sort of high school club.

We did basic training at Sasebo. In a time of peace, there really is nothing more refreshing to the spirit than to become a soldier. There wasn’t going to be any war. If something cropped up, the Americans would take care of us, we reckoned. So it felt like a sports club. There wasn’t a particularly powerful militarism about the place. There was an American overseer, you see, and if one of the Japanese officers got violent and slapped us around, he’d be fired right away. That was very reassuring. And they even gave us money… about 6,000 yen a month in those days.

I learned how to use a machine gun and a bazooka. They have tremendous destructive power. It was fantastic. Great fun. I became slightly manly. Taking responsibility for my own decisions. I think the British tradition of getting the royal princes to serve in the armed forces is a good one. Youngsters today should go into the army. They’ve got no discipline, they’ve got no culture, they’re not brought up strictly enough. I think yakuza children are better brought up as a matter of fact. Ironically enough. Because they’ll get killed if they mess around.

One day, when I was doing some road-building work, I had an accident. We were working like navvies on the orders of the sergeant. In the middle of some heavy rain, I was with a couple of other guys, trying to lift and carry a heavy concrete block. The conditions were so bad that we ended up dropping the block. It came down on my index finger and squashed it flat. The bone was sticking out. That was the first time I’d ever set eyes on my own bones.

|

Kimitsu’s accident |

I spent about ten days in hospital, and that finger remains painful to this day – when winter comes. The doctor did his best, and stuck the finger together again. But even so I couldn’t pull the trigger on a gun anymore. I daresay that if I’d been a carnivore like Arnold Schwarzenegger I might have been able to carry on working. If I’d been a roast beef guy or a steak guy, you know? But on rice and miso soup? I decided it would be better to quit. Japanese people have this tendency to give up rather easily.

I noticed a mistake in the record of our last conversation. You wrote “It was all I could do to stay alive from one day to the next. Every day a dance of fools. No time-outs.” But I didn’t say “dance of fools” (ahō dansu), I said “affordance” (afōdansu). It’s a biological thing really. A kind of natural science that goes beyond genetics, beyond Darwin. J.J. Gibson, the American psychologist, came up with it. What he says is that people don’t actually see things with their eyes or hear things with their ears – rather they are shown things, or allowed to hear things – they are afforded those experiences. The earth beneath our feet affords us the act of walking; a chair affords us the act of sitting. When a child gets born in the natural world, it has to be protected from lions. There are no walls in the house to afford protection. And when I was a kid, there was no affordance for me to think about the higher things; in the post-war chaos, we just had to struggle for survival every day.

I was a very angry young man. I was foul mouthed, I swore all the time. I was like a meteorite. I was only a private second class, but I insulted the soldiers around me, got into drunken fights. The next morning, I’d think, what on earth was I going on about last night? Oh the shame of it! (He starts talking in English; italicized.) In the morning, I think it’s a bloody shame. No good. It’s a cycle. That’s why I quit the military. Recognized I am no good. Bloody no good. Against god, against Buddha. So I ran away. Ran away. Away. I have nothing to do. Nothing great. So anyway, ran away. Went down from Hokkaido to Yokohama. So it began. Free time. A navvy. Day laboring at a time before the era of high economic growth set in. Almost poor people, like young boys in Ireland, London’s East End. So I go into Yokohama, construction sites, port lighterman. 1970. Same work, Putaro (day laborer) work, until about 2001. Along the coast, warehouses, on the ship. Like England, Thames River lighterman.

|

The pleasures of longshore work – taking a break on a Brazilian freighter |

I love Latin music, especially the bossa nova, and I much enjoyed taking a cigarette break and listening to that music with the Brazilian ship-hands. (Mimes bossa nova dancing). I felt as if I were connected to Brazil, and I really felt like diving into the sea and swimming to Brazil. The ship hands all had these cassette players that they’d carry on their shoulders while they listened to the music. The other ships were good too, but the Brazilian ones were the best.

I like stories about the sea. Like Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock or Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon. In the end, people are saved by the sea. Stories of the desert, like Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, are hard to endure. California’s turning into a desert. In a way desert people are the most modern. Because they’re furthest from the sea. The sea – that’s what everybody yearns for. I love Turner’s seascapes in oils. That dark sea, caught in an instant of a storm. We humans are water-based animals. So the sea has a calming effect on us. Rivers won’t do. You still feel a little insecure with a river. Even one like the Rhine. For looks, you cannot beat the Baltic. During the Cold War, there were these prisoners who escaped from camps in East Germany or Czechoslovakia, and they got away by going underwater up the Vistula river, breathing through long straws, until they reached the Baltic. Sure enough – what they ultimately yearned for was the sea. I saw the news of those escapees on the Movietone News at the cinema. So I guess it’s a fact that rivers hold out the prospect of escape.

I asked Kimitsu to tell me more about “affordance.”

If you want an analogy, consider the Cro-Magnon and Neanderthal men of the Stone Age. Theirs was a tough, pressurized existence, constantly having to protect themselves from lions, wolves and vultures. Their brains developed through a process of neural Darwinism, so that they could protect themselves better. Wild beasts would come to attack them; so too would the neighboring tribe. Then gradually their brains became more specialized, and they got to make weapons… guns, and then later atomic bombs. It’s something that can’t be helped, but the reason why humans are capable of wonderful things but do terrible things is because they lack an inclusive way of thinking. They can make better and better weapons, but they cannot fully grasp the significance of the way they use those weapons. So surely what we really need is a brain, or a philosophy, like Samuel Johnson’s – a way of thought that generalizes, that brings ideas together, that can encompass the whole picture. Johnson wrote the world’s first ever dictionary, and I think that kind of encyclopaedic, all-encompassing mode of thought is very important.

People like Yukawa Hideki and James Watt had a highly specialized mode of thought, and we need that too, but in the modern age we should think not only about utility but also about generality. At present we overemphasize utility. We no longer have lions coming at us, and there is no need to wave a gun around; therefore we no longer need our brains to develop in the direction of specialization. An end to war. This is the trend of what people call affordance.

Yes, what we need is a Samuel Johnson type of generalized worldview. Biologists have to take an interest in Buddhism. Research chemists must also research Christianity. Marginal knowledge is called for. Superman’s knowledge is needed. Self-control is needed. But in the present era, the self-control that is called for gradually becomes inhuman. We mustn’t smoke. We mustn’t drink. We mustn’t drive, because of the environmental damage done by exhaust fumes. Self-responsibility gets heavier. That is “inhuman self-control.” We can no longer do as we please. The environment reflects human lifeways, bringing hurricanes, whirlwinds and global warming as its “counter-argument.” That is the response of the natural world. Nature affords human beings the opportunity to live. People have to respond to that affordance.

The End

Postscript: The Last Days of Nishikawa Kimitsu

On November 14, 2014, Kimitsu was obliged to leave his little room in Kotobuki and enter the dementia ward at a hospital in a semi-rural outskirt of Yokohama. I made a few visits, the last being on Sunday, April 12, the day of his 75th birthday. That he lived to see that day was in itself a remarkable fact, since Kimitsu lived almost entirely on alcohol for most of his adult life and never expected to live past sixty. What follows is a note from my first hospital visit.

I ascend the stairs to the third floor, where Kimitsu is being kept in the dementia ward. A locked metal door bars access. I have to write my name and address on a piece of paper, along with the name of the person I wish to visit. Then I press a button on the interphone and request admission. This is a gently controlled society. A nurse comes and lets me in. They are expecting me. You have to ask permission in advance. The last time I was refused, as there had just been an outbreak of influenza in the ward.

Into the ward. A big, airy room with patients sitting around here and there, a few of them moving back and forth, mostly in wheelchairs. One man by the window in red protective head gear like boxers use for sparring. He sits there unmoving all the time I am there, occasionally letting out a groan. A tiny old lady lying back on a bed gives me a seraphic smile and a wave.

The nurse goes to Kimitsu’s room and brings him out in his wheelchair, and we are left together in a semi-enclosed space called the danwa-shitsu or conversation room. The last time I saw Kimitsu, he could still walk. I believe he probably still can. I soon realize that the wheelchair is a form of restraint. It has a safety belt with its clasp at the back of the chair, where Kimitsu cannot reach it. I ask the nurse about restraint of patients, and she admits that it is practiced here. In fact, she volunteers that when Kimitsu first arrived, he was tied to his bed at night. They do not do that to him anymore, she adds. However, he is still wearing a one-piece pajama that he cannot take off without assistance.

When Kimitsu sees me, he gives a friendly smile. He has a good appetite, and swiftly devours two little pots of pudding I have brought for him. (The hospital had recommended pudding, warning me that Kimitsu had difficulty eating anything more solid.) “Got a cigarette?” he asks, several times.

Kimitsu was taken off alcohol a couple of years ago, when Dr. Tsuchiya Hiroko, who looked after him at the Kotobuki clinic, persuaded him to accept an alcohol-free regime to prolong his active life. As well as his strokes, he was also suffering from slowly progressing liver cancer. He had no access to cash – instead, a case worker would take him shopping with his welfare money and buy him anything other than alcohol that he needed. That was very hard for him. He nearly always asked me to get him a drink when I visited him. But they did let him smoke – almost as a compensation for deprivation of alcohol. That had ended when he moved into hospital. Now instead of asking for a drink, he asked for a cigarette.

“Do you remember me, Kimitsu?”

“Of course, we danced the Bon Odori together.”

It was true. Many years ago I had hung out with him at the Kotobuki summer festival, and we had danced the Bon Odori, shuffling around the towering stage with the taiko drum being beaten upon it.

“We were back at the festival again last summer, selling our book.”

“Yes, it sold very well.”

We had managed to flog 37 copies in a few hours.

|

Selling the Japanese edition of the book, August 14, 2014 |

“I’ve been reading Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro recently.”

“You can’t beat Sōseki. I read And Then when I was a kid. Sōseki’s got a special atmosphere all of his own.”

In moments like these, Kimitsu didn’t seem senile at all. But when I showed him the proposed cover image of the English edition of our book, Yokohama Street Life, he asked me who were the two men in the photograph.

“Don’t you know? It’s you and me! When we were a bit younger.”

“Oh…”

OK, that photo was taken 22 years ago and neither of us is quite the man he once was.

“How old am I, anyway? A hundred? Ninety-nine?”

“Kimitsu, you are a youthful 74.”

He seemed dumbstruck to learn that.

I tried to get him to talk about his youth. “We lived in a working-class district, next to a factory that made parts for airplanes… music was my favourite subject at school – I liked my music teacher…”

No one else would be interested, but these were fragments I hadn’t heard before, and I dutifully noted them down. But when I tried to draw him out some more, he suddenly said he wanted to go to bed. Somehow I persuaded him to stay up a little longer. Kimitsu was restless – he kept trying to get out of his wheelchair. A nurse removed the cumbersome meal tray that had been clipped to the wheelchair handles, but still he wasn’t satisfied. He kept struggling to stand up.

When the nurses weren’t looking our way, I surreptitiously reached round the back of the wheelchair and unclipped the safety harness. He struggled to his feet and walked unsteadily away from the wheelchair. He had lost the use of his left hand in his second stroke, but he used his right hand to grasp the rail running along the wall of the corridor and steadfastly advanced. I took his left arm and gave a little support.

I don’t know where he thought he was going, but our route took us past the nurse station and attracted attention. A nurse approached and tried to steer us back to the wheelchair. Kimitsu pointed to the gents toilet. “He’s wearing a diaper, and he doesn’t usually go to the toilet,” the nurse confided to me, but she was good-natured enough to take Kimitsu to the toilet. I doubt whether he produced anything there. The nurse was also kind enough not to ask who had released Kimitsu from his wheelchair, but I took the liberty of pointing out that he seemed to be quite good at walking. “Yes,” said the nurse, adopting a sterner tone, “but it would be a serious problem if he fell over.” I suppose she had a point.

Back in the conversation room, Kimitsu sank into the wheelchair in apparent exhaustion, but moments later he stood up and started walking off again. This time I managed to steer him down an empty corridor away from the nurse station, but as soon as we got back to the conversation room he was off again and heading for the nurse station. He tried to sit down on a bed right in front of the nurse station, finally prompting an intervention. “That’s not your bed, Mr. Nishikawa,” said a nurse, kindly but firmly, and she steered him back to the conversation room. She put him in the wheelchair, locked the harness and gave me a slightly reproving look.

The thing is, there are old people in hospital who the doctors and nurses want to walk, and those they do not want to walk. My mother-in-law is one of the former – the staff at her hospital are always encouraging her to try and walk a few steps, to move towards rehabilitation and save her from becoming totally bed-ridden. But Kimitsu was in the latter category. The moment he started walking he would surely go somewhere he wasn’t supposed to go and cause trouble for everybody. That was the real reason he was lashed to his wheelchair – not the risk he might fall over. This foreigner who had suddenly shown up four months after Kimitsu arrived in the hospital knew nothing of his condition and was making a lot of trouble by releasing Kimitsu from his wheelchair. That, I imagine, is how the staff looked upon me.

When I first arrived, a senior nurse had told me, “He’s in a wheelchair because he can’t walk properly.” But when I was taking my leave the same nurse confided in me, “we do let him have a walk once a day, for rehabilitation. This is a hospital, and really he should be in a different kind of institution, where they put more emphasis on rehabilitation. We just don’t have the staff for it.”

That is the nub of the matter. Letting Kimitsu walk about freely would mean having a member of staff keeping an eye on him all the time. And that goes beyond what a social welfare recipient in contemporary Japan can expect.

A week later, I received my first copies of Yokohama Street Life from the publisher, and on March 17, 2015 I returned to the hospital to give Kimitsu a copy. I’d had a brilliant idea. I’d asked the hospital if it would be OK to take Kimitsu out to Zoorasia, a nice wildlife park that happened to be quite near the hospital. Kimitsu was being kept warm and fed, but he wasn’t getting any mental stimulation. He wasn’t reading any more, and I heard from the nurses that he barely even watched TV. Perhaps seeing some exotic animals would perk him up. I was given permission, provided I hired a “care taxi” (kaigō takushii) that he could get on while still riding his wheelchair. I did that, and very expensive it was too.

Alas, on the morning of my visit, I received a phone call from the hospital, saying that the doctor in charge of Kimitsu had withdrawn permission for him to be taken out. I do not know what exactly prompted that change of heart. Maybe they decided they couldn’t trust me not to pump him full of alcohol and nicotine. I had to cancel the care taxi. By way of consolation, I was allowed to wheel him out to the car park in front of the hospital, with a nurse in attendance, to get a breath of fresh air and take a look at a few flowers they had growing in a corner of the car park.

I made one last visit, on Kimitsu’s 75th birthday – April 12. I had some more fancy pudding for him, and a sensational weekly magazine. He was quite interested in the magazine, but he couldn’t read it as he didn’t know where his reading glasses were. I asked the nurses, and they eventually found them in the downstairs ward where he had spent the first couple of weeks. That meant he hadn’t read anything for several months – kind of sad, for such an avid reader as he.

They still wouldn’t let me take him to the zoo. One of the reasons, a nurse told me, was because I wasn’t a relative. We who are mere friends are not to be trusted with patients. I did have a try at writing to Kimitsu’s sister in Kyushu, asking if she might put in a word for me with the hospital authorities, but nothing happened

|

Signed drawing of Nazi officer attached to Kimitsu’s hospital bed |

“Mister Nishikawa has left the hospital”

It was a Monday evening, the first of June. My wife and I stopped off at Chigasaki on our way home from work to visit Kimitsu. I had just heard from his social welfare case worker that he had changed hospitals because of a deterioration in his liver cancer. And so we went to the reception and asked which room he was in. We were told the west wing on the fourth floor, so that’s where we went. But the nurse there insisted that there was nobody of that name in the ward. We should try the east wing. The nurse in the east wing insisted that he definitely was in the west wing and went back there with us. A lengthy conversation ensued between the east wing nurse and the west wing nurse, as they bent over a computer. Finally, the east wing nurse came over and told us, “he was here, but he has left the hospital today.”

Fearing the worst, I telephoned Dr. Tsuchiya. She promised to investigate and we went to a nearby izakaya to get sashimi and lemon sours while we waited.

Shortly the phone call came. As I feared, Kimitsu had died that morning, around 3.15 a.m. We’d missed him by a few hours. The hospital couldn’t tell us he’d died because of the heavy rules on patient confidentiality. All they could tell us was that he’d left.

It is the end of a 22-year-long friendship. I am going to miss that guy. The last half year of his life was not much fun, as he was slowly worn down by liver cancer and senile dementia. But at least he lived long enough to see both the Japanese and English editions of our book.

There are a lot of interesting old men in Kotobuki. I am glad I managed to preserve the memory of just one of them.

|

Kimitsu on his 75thbirthday, April 2015 |

Farewell to Kimitsu

Three days later, on June 4, I got up much earlier than usual and put on my only respectable black suit. My black shoes were useless – the left one was gaping open at the toe. I would have to see Kimitsu off in brown shoes. My wife also had her mourning on and we cycled down to Ninomiya station in bright and breezy early morning air. We caught the train to Tsujido and found the funeral parlor. We were ushered into the foyer, all diffused light and marble, and an unctuous attendant introduced us to the only other mourner – Kimitsu’s younger brother, who had come up from Osaka to collect the ashes and take them back to the family home in Yamaga, Kumamoto prefecture.

He was a short, stocky man with gleaming gold teeth and hazel eyes twinkling behind his silver-rimmed glasses. Just 69, he’d retired after working his whole career at Matsushita Electric. Kimitsu’s family was not the kind of rough, proletarian family you might have expected of a career day laborer. His father had been a banker, his younger brother was a respectably solid salaryman, and his older sister was headmistress of a kindergarten in Yamaga. Something got into Kimitsu when he was a kid that sent him in a different direction. I don’t know quite what it was.

I had mixed feelings about Kimitsu’s brother. During fifty years when Kimitsu was living in Kotobuki, his brother had almost completely ignored him. He seemed happier to see Kimitsu dead than alive. But who am I to judge such things? Kimitsu himself admitted that he had been drunk and badly behaved in the far-off days when he still went to see the family occasionally. His mother had caught him drinking from a concealed bottle when he visited his father on his death bed in Kumamoto Hospital way back in the 1970s, and given him a slap in the face. His sister had described him in a phone call with me, striding around the ward, loudly uttering incomprehensible stuff in a foreign language, possibly English.

I only knew Kimitsu when he was already getting old and had mellowed out a bit. I didn’t know the roaring Kimitsu of his youth. I never met the Kimitsu who nearly killed a man in Kotobuki in a drunken knife attack and served two-and-a-half years in prison for armed assault.

I could not, therefore, pass judgment on his family for avoiding him while he was alive. Rather, I was relieved that one of them had come to get his mortal remains. In that respect, Kimitsu was luckier than a lot of other day laborers. Often a man dies with no known relatives in Kotobuki. Such a man is called a “muen-botoke” or “unconnected spirit.” His remains may well end up in the Charnel House for the Deceased without Relatives in Yokohama’s Kuboyama Public Cemetery, there to be kept for five years and then chucked away if still unclaimed. Luckier men, known to activists or social workers, may find a resting place on the Hill of a Thousand Autumns (Senshūgaoka) at Tokuonji temple, a radical rural temple in Yokohama that has found space for unconnected spirits from Kotobuki since the 1990s.

I sometimes thought that the Hill of a Thousand Autumns might be quite a good resting place for Kimitsu, as it would reunite him with a lot of workmates from the place where he lived half his life. But the man himself yearned for Yamaga. When he turned 65, he sensed mortality and developed a powerful homing instinct. He paid several visits to Yamaga, which would be a full day’s journey from Yokohama by the bullet train, but took three or four days for Kimitsu, fare dodging on slow local train lines and sleeping rough at random rural stations. He would show up at the rusty old hot-spring town of Yamaga late at night and drunk. He would bang on his sister’s door and shout out, disturbing the neighbors. One time she had to collect him from the hospital after he collapsed in the street on the way to her house.

Yes, it was a good thing that Kimitsu’s brother had come for him.

The bowing attendant took the three of us into a little white room where Kimitsu was lying, dressed in a yukata – a light cotton kimono – and wrapped up in a blanket in an open coffin on a pair of trestles. It seemed like a pretty cheap plywood coffin, fair enough since it was about to be burned, and a perfect rectangle. There were no flowers in the room, no incense burning, no monks chanting sutras. Just the bare minimum.

I had imagined him drained white, but his face was a ghastly yellow, no doubt due to the jaundice that had set in during the final phase of the liver cancer that finished him off. His toothless mouth was closed with the lips puckered in. He’d been given a shave and a haircut and looked very dead indeed.

My wife burst into tears and apologized for not coming to see him one more time. She placed a bouquet of purple and white chrysanthemums on Kimitsu’s breast. Kimitsu’s brother also had a present for him. It was a hundred-yen carton of rough saké, which he placed above Kimitsu’s shoulder, near his mouth. “You can drink as much as you like now,” he said softly. “And don’t worry, I’m going to take you home to Yamaga.” He placed his hands together in prayer, with a string of brown wooden juzu prayer beads wrapped around his left hand. I did the same, only with black prayer beads I’d bought from the hundred-yen shop, along with a special kōden envelope to put some money in for Kimitsu’s brother, and a fukusa envelope to put the kōden envelope in. So much wrapping up goes on at a Japanese funeral. And in 25 years living in Japan, this was the first time I’d attended one – not that this was a proper funeral, just a quick send-off.

Somebody, perhaps a nurse at the hospital, had put a plastic bag in the coffin by Kimitsu’s feet. We were all curious about it, and Kimitsu’s brother opened it up to have a look. It turned out to contain some underwear and socks – something for the journey.

Eventually the three of us backed out of the room, saying sayonara as we left. We returned to the foyer and I took the opportunity to hand the kōden over to Kimitsu’s brother. “Tsumaranai mono desu ga…” (“I know it’s not much, but…) I said, which was totally wrong. I should have said “goshūshōsama” (deepest condolences). My wife put me right later. Despite the gravity of the situation, she had to struggle not to burst out laughing.

A little later we followed the coffin out of the hospital and helped the staff to load it onto the back of the hearse. It wasn’t one of those magnificent Japanese hearses with a shiny black body and magnificent gilt wood carvings on the top. This one wasn’t even black. It was a grey station wagon that had been modified to accommodate a coffin.

There was only room in the hearse for two passengers, so my wife left us to go and attend an operation her mother was to undergo that very afternoon. Kimitsu’s brother and I climbed in. He was in front, I was behind, sitting next to the coffin. I was right next to Kimitsu on his final journey.

It took about half an hour to drive to the crematorium in Totsuka. On the way, Kimitsu’s brother was quite happy to chat about Kimitsu, sometimes giggling in a slightly disconcerting way. Being five years younger than Kimitsu, he had been born just after the war ended – a decisive difference in early life. Still, life in the early years after the war was a desperate affair. He recalled how the family would go to the river and gather horsetails (tsukushi) from the embankment to boil up with soy sauce and eat for dinner.

He recalled a dreadful row between Kimitsu and his mother, over a judo suit. At the age of 16 or so, Kimitsu was already a black belt in judo (something he never mentioned to me), but he only had one judogi. He kept asking for another one, since he was reduced to borrowing from friends when his judogi was in the wash, and his mother kept putting him off because she hadn’t yet saved enough money. Finally Kimitsu’s frustration boiled over in a furious tirade against his mother. Kimitsu’s brother vividly remembered that incident and even named it as the reason why Kimitsu rarely talked about his mother. Could that have been Kimitsu’s rosebud moment, the trigger that sent his life off on a trajectory so different from those of his siblings?

We arrived at the crematorium. The coffin was transferred to a stainless steel trolley and placed in front of a stand which had a little mound of incense burning on it, along with a mound of fresh incense. My wife had taught me to take three pinches of the fresh incense, drop them onto the burning incense, then put my hands together in prayer. So I did that, although Kimitsu’s brother only transferred one pinch of incense.

Then the coffin was taken to a room with six furnaces. Kimitsu’s name was displayed next to furnace number 4. Kind of funny. The number 4 is considered ill-omened in Japanese, because one of its readings – shi – is a homonym for “death,” and many condominiums don’t have a 4th floor. But apparently they had no qualms about numbering a furnace No.4. Maybe being associated with death doesn’t matter anymore once you really are dead.

Kimitsu’s coffin was whirred into the furnace on a conveyor belt. The brother and I would have to wait an hour or so for the flames to do their work. It wasn’t like in the film Okuribito (Departures; 2008), where the mourners get to see the flames licking around the coffin through a glass window. No, we just got to sit in a functional grey waiting room with a little shop and some vending machines, with a bereaved family dressed in black but merrily stuffing themselves with food while the children played with their yo-yos. I got myself a comforting bar of chocolate and shared a few squares of it with Kimitsu’s brother, while we talked a bit more about Kimitsu’s childhood.

Eventually we were told we could come and view the remains. We saw them being removed from the furnace on a pair of square steel trays. Not ashes – white bits of bone. They were wheeled into an adjacent room, where a tubby, rosy-cheeked attendant in crematorium uniform – blue trousers and a blue-and-white striped shirt, with a blue peaked cap – gave us a little lecture. Bones from the bottom half of the body were in the left tray, bones from the upper half were in the right tray. This bone was a bit of skull, from just next to an ear, and that one was from where the neck joins the shoulder. Kimitsu’s brother picked up a couple of the larger fragments and dropped them into the plain white china urn which the crematorium supplied as part of the service for its modest 12,000 yen fee. Then I did the same. The attendant plonked in a few more bones, then put the lid on, sealed it with adhesive tape, put it in a white silk bag, and gave it to Kimitsu’s brother, who wrapped it in a purple cloth he had brought with him for the purpose.

The urn was far too small to put all the bone fragments in. At least three-quarters of them were left behind in the steel trays, later perhaps to be chucked out with the rubbish.

|

Celebrating publication of the English edition, May 2015 |

Kimitsu’s brother and I took a taxi to Totsuka station. He was heading back to his hotel in Tsujido, then on to Haneda airport to catch a plane bound for Kumamoto, from where he’d get the bus to Yamaga and introduce Kimitsu’s bones to their sister. The next day, he told me, they would have a proper funeral in Yamaga.

As for me, I waved him goodbye, then caught the staff minibus to go and teach a couple of classes at the university, trying hard to put Kimitsu’s stretched and yellow face out of mind for a while.

Tom Gill is a professor at Meiji Gakuin University. He is the author of Men of Uncertainty: the Social Organization of Day Laborers in Contemporary Japan, co-editor of Globalization and Social Change in Contemporary Japan, and co-editor of Japan Copes with Calamity: Ethnographies from the Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Disasters of 2011.

The publisher’s data for Yokohama Street Life may be found here.

A flyer for the book, with a 30% discount form, may be found here.

The Japanese edition, Mainichi Ahoudansu (『毎日あほうだんす:寿町の日雇い哲学者西川紀光の世界』, (Everyday Affordance: The World of Nishikawa Kimitsu, the Day Laboring Philosopher of Kotobuki-chō) was published in 2013, and is available from Amazon Japan.

Alternatively, the whole text is available to read for free at Tom Gill’s academia page, under books.

Recommended citation: Tom Gill, “Yokohama Street Life: The Precarious Life of a Japanese Day Laborer”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 34, No. 2, August 24, 2015.

Related articles

• Paul Jobin, The Roadmap for Fukushima Daiichi and the Sacrifice of Japan’s Clean-up Workers

• Gabrielle Hecht, Nuclear Janitors: Contract Workers at the Fukushima Reactors and Beyond

• Tom Gill, Failed Manhood on the Streets of Urban Japan: The Meanings of Self-Reliance for Homeless Men

• Stephanie Assmann and Sebastian Maslow, Dispatched and Displaced: Rethinking Employment and Welfare Protection in Japan

• David H. Slater, The Making of Japan’s New Working Class: “Freeters” and the Progression From Middle School to the Labor Market

• Toru Shinoda, Which Side Are You On?: Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics