Introduction

As discussed in Part I, Buddhist temples in Japan have, at least until recently, had a near monopoly on the conduct of funerary rites, including memorial services for the deceased lasting over many years, even generations. Additionally, cemeteries with family, not individual, graves are typically located on temple grounds. Thus, temples play a significant role in the manner in which the deceased are remembered if not eulogized.

Deceased soldiers from the Asian-Pacific War (1931-45) can be eulogized with as simple a designation as that ofeirei(heroic spirit) added to their names on grave markers or other monuments. From there, as introduced in Part I, it can escalate to take on many forms such as statues of Kannon(Skt. Avalokiteśvara, Ch. Guanyin), located either outside or inside of temples, whose compassionate embrace is dedicated to consoling the spirits of deceased soldiers, e.g.,Tokkō Kannon(Kannon for “Special Attack Forces” akaKamikaze pilots).

Part II of this article focuses on the way in which deceased soldiers, and the war they fought in, are remembered and eulogized at the headquarters of the esoteric Shingon sect in Japan located on Mt. Kōya. Unlike the Zen sect, the Shingon sect was not closely connected to Japan’s warrior class and therefore is not known as an especially warlike sect. However, it was closely connected with Japan’s aristocracy, including the emperor, from the time of its introduction into Japan by the priest Kūkai (774–835) at the beginning of the ninth century. With its elaborate mystical ceremonies, it was quickly adopted by the aristocracy due to its alleged ability to protect the state (chingo kokka) from all manner of calamities, war included. Thus, like other institutional Buddhist sects, it fervently supported the Asia-Pacific War. In the postwar period the Shingon sect would also play a role in war remembrance, especially as the right wing in Japan maintains that the peace Japan now enjoys is thanks to the ultimate sacrifice made by millions of its soldiers during the war.

Additionally, as its English name, “True Words” (Shingon), suggests, this sect places great emphasis on words or syllables, for it regards the recitation of particular mystical syllables or phrases, i.e., ‘true words’ (Skt. mantras), as having inherent spiritual power, contributing to the enlightenment of the practitioner. Thus this sect is very careful in its use of language to the point that its most intimate teachings are subject to solely oral transmission from master to disciple. Speaking ‘false words’ is held to produce as much harm as ‘true words’ can bring spiritual awakening. Just how ‘true’ the war-related words this sect now promotes on Mt. Kōya I leave to the reader to decide.

Religion’s “Social Reality”

Before going further, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that what I am about to describe on Mt. Kōya, like the examples presented in Part I, is only one “case study” of a more universal phenomenon, i.e., the manner in which all faiths are inevitably incorporated into the wars their countries fight. Sociologist Peter Berger describes what he calls the “social reality” of religion as follows:

Whenever a society must motivate its members to kill or to risk their lives, thus consenting to being placed in extreme marginal situations, religious legitimations become important.… Killing under the auspices of the legitimate authorities has, for this reason, been accompanied from ancient times to today by religious paraphernalia and ritualism. Men go to war and men are put to death amid prayers, blessings, and incantations.1

Yet, it is also true that there is a uniquely Japanese cultural component embedded in this universal social reality just as there is a Buddhist, and more explicitly, a Mahāyāna, component. Sacralized warfare, better known as “holy war,” may be universal, but it is always found embedded in the culture and religious faith of which it is a part.

Mt. Kōya

The Shingon temples on Mt. Kōya give little hint to visitors, especially from abroad, of this sacred mountain’s links to Japan’s wartime past. First time visitors cannot help but be impressed by not only the large number of temples, but by the age and scale of temples like Kongōbu-ji, the ecclesiastic headquarters of the Mt. Kōya branch of the Shingon sect.

|

Kongōbuji |

They will also be impressed with the nearby complex of temples and pagodas known as the Danjo Garan.

|

Danjo Garan |

However, visitors will encounter stone pillars here and there dedicated to one or another Japanese military unit and the soldiers or sailors who served in it. Some of these pillars stand along the road in front of one of the many temples on Mt. Kōya and others are located in the vast adjoining cemetery.

Manihōtō

In addition to the many pillars, one finds large war-related structures as well, the largest of which is the three-storied, octagonal Manihōtō pictured below. As the only eight-sided structure on Mt. Kōya, the architectural style was chosen because it is the closest to the nearly circular form of a Burmese temple, Completed in 1984, the Manihōtō is located alongside the main road leading to the massive cemetery area and Oku-no-in, the mausoleum of Kūkai, founder of the esoteric Shingon sect of Buddhism in Japan. Its stated purpose is “to pray for the repose of the heroic spirits.”2

|

Manihōtō |

On entering this temple one encounters two Buddhist statues, one, a small Burmese-style statue of the historical Shakyamuni Buddha seated in front, the second, a much larger statute of Fudō Myō-ō in the rear.

|

Shakyamuni with Fudō |

This is an unusual juxtaposition of Buddhist statuary in any of Japan’s Buddhist sects. Although only his glowing eyes can be seen in the background, Fudō Myō-ō (Skt. Ācala-vidyā-rāja) has a long-standing relationship with Shingon as an esoteric deity, especially as a Dharma protector as well as vanquisher of evil, symbolized by the sword he holds in his right hand and the lasso in his left. It was this latter characteristic that made Fudō (lit. immovable one) a popular deity, including among warriors, past and present.

As the content of this altar reveals, Fudō’s manifest presence behind the Burmese Buddha is clearly a symbolic representation of Japan’s rationale for its wartime occupation of Burma, i.e., not to subdue the Burmese or occupy their country but to free and protect them and their Buddhist faith from the ravages of their prewar colonial ruler, Great Britain. This story line is repeated again and again in the photographs and words of this temple building.

|

Fudō |

Military connection

First, it is necessary to establish the connection of this temple-like building to the Imperial Japanese military. This is done through a number of exhibits that would normally be displayed only in a war museum. Display cases immediately to the left and behind the main altar contain wartime uniforms, weapons and assorted military paraphernalia.

|

Military paraphernalia |

With the military connection clear, the major focus of the visitor’s attention as one proceeds into the gallery is directed toward the various photographs of Imperial Japanese soldiers interacting with Burmese civilians and government officials. The viewer is given the impression that the Burmese welcomed, and were grateful for, the Japanese military occupation of their country that began in March 1942.

Here is a photo of officer candidates beaming with youthful enthusiasm and pride as they train to become future leaders of what would come to be known as the Burma National Army, the forerunner of which had been created by the Imperial Japanese military with the support of indigenous Burmese leaders.

|

Officer candidates |

Significantly, Burmese officer candidates were trained by their Japanese mentors. Notice that the signage for their training camp is entirely in Japanese. Furthermore, as if to underscore the military-religious connection, there is a depiction of a Buddha, likely Amida Buddha, on the wallpaper at the bottom left behind the photograph.

|

Office candidates with Japanese writing |

Albeit in a nursing capacity, Burmese women were also given the opportunity to voluntarily join the newly constituted Burmese military. While the Burmese soldiers salute, the women bow, Burmese flag in hand.

|

Burmese nurses |

At the same time there are also plaques scattered throughout the Manihōtō with words of praise for Imperial Army units stationed in Burma. The following plaque describes the well-known Yoshida Regiment: “From an early stage in the war its courageous name was well known. It received letters of commendation for its great deeds.”

|

Yoshida regiment |

Lt. General Iida Yōjirō was the Imperial Army officer in charge of the Burma theatre. In this photo there are nothing but happy smiles on the part of all.

|

Iida Yōjirō |

The Japanese occupation of Burma was, however, not exclusively military. Shingon Buddhist priest Ueda Tenzui is seen here giving Japanese language lessons at a Burmese Buddhist temple. He would go on to establish Japanese language schools throughout Burma. In addition to their role as military chaplains, Buddhist priests like Ueda played a significant role in the Japanese war effort, particularly in occupied Buddhist countries, where they promoted a sense of pan-Asian religious identity, thereby lessening resistance to Japan’s military rule. Such priests also served as spies for the Imperial military, identifying individuals and groups in the local community opposed to Japanese occupation of their country.

Following repatriation to Japan in the postwar period, Ueda went on to become the president of Mt. Kōya University. It was Ueda who first proposed the construction of Manihōtō.

|

Ueda Tenzui |

Perhaps the most important photograph of all is the one showing the first Burmese Prime Minister and his Cabinet wearing Japanese decorations on traditional dress at the time of Burma’s alleged “independence” on August 1, 1943. Such photographs, taken in wartime Burma and the other colonized countries of Southeast Asia, have been long been used to prove that Japan fought to liberate Asia from the yoke of Western colonialism.

The third man from the right in Japanese-style military uniform is Aung San, minister of defense, father of today’s well-known political leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who is widely regarded as the founder of independent Burma. During the Japanese occupation, Aung San took the Japanese name of Omoda Monji (面田紋次).

Using Truth to tell Lies

No photographs are on display dating after August 1, 1943. This may not seem strange to some, for with Burma’s independence on that date one might expect the Japanese military would have gone home (or at least to their next battlefield), mission accomplished. In fact, the Japanese military did not leave Burma until May 1945 when they were routed from most of the country by the Burma National Army with the aid of the British. Their expulsion came about as a result of the Burma National Army’s countrywide rebellion begun on March 27, 1945. But why had the Burmese revolted against the very military that had freed them from the British?

As British Field Marshal William Slim described it:

It was not long before Aung San found that what he meant by independence had little relation to what the Japanese were prepared to give – that he had exchanged an old master for an infinitely more tyrannical new one. As one of his leading followers once said to me, “If the British sucked our blood, the Japanese ground our bones!”3

Had the Burmese understood why the Japanese occupied Burma in the first place they would not have been surprised by the way they were treated. For Japan’s military leadership, Burma’s nominal independence was merely an expedient way to secure Burmese support for their occupation. Their true objective was to cut off a critical Allied supply link to the Nationalist Chinese. It was critical because the Japanese had already occupied all of China’s seaports and regarded the recently constructed 700-mile Burma Road as China’s last remaining lifeline. The Japanese also knew that rubber was one of the few militarily vital resources the United States lacked. To gain peace terms favorable to Japan, it was critical to deny the Allies access to Southeast Asian rubber supplies.

The historical record also demonstrates that exchanging “an old master for an infinitely more tyrannical new one” is an apt description of the entire Japanese “liberation” of those Asian countries formerly colonies of the Western powers. This certainly doesn’t excuse the ‘blood-sucking’ of the British, any more than that of other Western colonial powers, including the United States with its colonial control of the Philippines. But it does reveal that the Japanese were also colonialists whose brief rule, under increasingly desperate military conditions, was even more repressive. However, this part of the Japanese occupation of Burma is not even hinted at among the litany of smiling faces hanging on the walls of Manihōtō. It is by omitting the whole truth of Japan’s occupation of Burma that the partial truth on display can be utilized, even today, to falsify the reality of Japan’s alleged liberation of Asia from the yoke of Western colonialism.

In the cemetery

If, in some sense, the exhibits in Manihōtō represent a ‘soft’ or indirect approach to valorizing Japan’s wartime actions, the same cannot be said for the major war memorials in the nearby cemetery. Although these memorials are located some distance away from the main pathway leading to Kūkai’s mausoleum, they are nevertheless located in a place of prominence and readily accessible anyone who looks for them. Given the language barrier, however, foreign visitors are highly unlikely to understand their significance even if they were to stumble across them.

The most impressive of all of the cemetery war memorials is known as the “Eirei-den” or “Hall of the Heroic Spirits.” It is dedicated to all military personnel who died during the war. While it is only the name of the Eirei-den that serves to valorize the war, the same cannot be said of signage located immediately beside it or the other war memorials on each side.

The first sign on the left is replete with a map of Asia, showing the countries in which the Imperial Japanese military was active. One might expect to find the numbers of Japanese casualties in each of these countries, but the title at the top of the sign tells a much different story. It reads: “Shōwa Junnan-sha Shibotsu-chi Ryakuzu” (A Rough Sketch of the Places Shōwa Era Martyrs Died).

But who were these “martyrs” from the Shōwa era (1926-1989)? The number of martyrs recorded in each country leaves no doubt. The reference, as exemplified by the seven executed martyrs in Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison, is to what the rest of the world calls “war criminals.” A total of 1,180 Class A, B, and C war criminals were either executed or died in prison as a result of military tribunals held by the Allies throughout Asia. More than 3,000 others received prison terms of varying lengths.

Immediately to the left of this sign stands one of the stone pillars described earlier. The inscription on this pillar, however, is somewhat unusual in that it contains the death poem of an Imperial Naval officer written just before he was executed as a war criminal. Engraved on it are the words of Imperial Navy Lt. Kamitōge Yukinosuke: “Innocent though I am, I am made to bear the grave sin [of having committed war crimes]. I am just a soldier from the Wakayama area whose body will be scattered to the winds.” The point of this pillar, like the map adjacent to it, is not simply to lament the postwar death of an allegedly innocent soldier by Allied justice but to symbolically decry the whole postwar system of war crimes trials, derided by Japan’s right wing as nothing more than “victor’s justice.”

To the left and right of the Eirei-den are still more war memorials related to both individual military units as well as those areas in which they fought, especially the Battle of Okinawa fought in the spring of 1945. Often built of marble, these monuments are clearly designed to last a lifetime and more. The two Chinese characters on the large stone on the left of this monument, typical of many others, read chinkon (repose of the deceased).

Each of the many monuments also has an inscription that explains the background and purpose of its construction. The preceding monument’s inscription (located on the right-hand side) reads as follows:

Purpose of the Monument

The heroic spirits of those who died during the Great East Asia War rest in this place. They were graduates of the Maebashi Army Reserve Officers Academy.

We recall that these soldiers, forming the nucleus of the Imperial Army, pledged their bodies and minds at a time of national crisis for our nation. More than 7,000 of our comrades, having cast aside their civilian occupations and abandoned their studies, bravely departed the academy’s doors to go to their assigned stations without any hope of returning alive. This occurred in the midst of the great war.

Brothers, nothing can be compared with our regret when we consider how you tested your patriotism in the bitterly cold wilderness or fought starvation in the dense jungles of lonely islands. Or how you submerged yourselves in the southern oceans with utmost loyalty or painted the blue sky a bright red, offering your young lives as righteous martyrs for your country. When we recall your rosy cheeks, a thousand emotions flood our hearts, and it is difficult to hold back our tears of bitterness.

However, your heroic deaths were not wasted, for our nation, Japan, has experienced thriving development, making peace its national policy. Thus a group of us got together to erect this public monument to pacify your spirits and transmit your feats of utmost loyalty and valor to future generations.

While the regret and sadness at having lost their comrades in the Asia-Pacific War is palpable, what is striking is that there is no hint of reflection on the roots, meaning or consequences of Japan’s war of aggression, let alone the vast destruction it brought to millions of Asian peoples not to mention Japanese soldiers and civilians. On the contrary, the creators of this monument want to make sure that the “feats of utmost loyalty and valor” of their deceased comrades are transmitted down to future generations in perpetuity. Although Japan’s postwar policy of peace is acknowledged, there is nevertheless the suggestion that future generations should be prepared to fight and die for Japan when faced with a “national crisis.”

War-related Ceremonies

In addition to permanent war-related memorials, there are yearly memorial ceremonies dedicated to not simply remembering but valorizing Japan’s wartime endeavors and soldiers. These ceremonies, especially those dedicated to war criminals, have raised concerns both inside and outside of Japan. One example is described by Martin Fackler in the August 27, 2014 New York Times:

Japan’s Premier Supported Ceremony for War Criminals

TOKYO – Japan’s conservative prime minister, Shinzo Abe, sent a message of support earlier this year to a ceremony honoring more than 1,000 Japanese who died after convictions for war crimes, a government spokesman said on Wednesday. The move could worsen frictions between Japan and its neighbors, particularly China, over bitter memories of World War II in the region.

Mr. Abe wrote in the message that the convicted war criminals had “sacrificed their souls to become the foundation of the fatherland,” according to a news report that first appeared in The Asahi Shimbun, a major Japanese newspaper.

One would like to ask Prime Minister Abe what it means for contemporary Japan that it must rely on Japanese soldiers and officials convicted of deadly brutality toward prisoners of war and civilians as “the foundation of the fatherland”? Can any and all acts, no matter how horrific, be justified, even eulogized, in the name of nationalism?

The spokesman, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga, confirmed the report, saying that Mr. Abe had sent the message not in his public capacity as prime minister but as a private citizen, signing his name as the head of the governing Liberal Democratic Party. The report said the message was read aloud at the ceremony, which was held on April 29 at the Mt. Kōya temple4 in western Japan. Mr. Abe did not attend.

The annual ceremony, which is not well known in Japan, honors 1,180 Japanese who were executed or died in prison after being convicted of war crimes by Allied tribunals. The tribunals, which were held across Asia after the war, convicted the Japanese soldiers and officials for crimes such as the massacre and rape of civilians and the killing of Allied prisoners of war.

The ceremony’s organizers share a view held by many on Japan’s right that the tribunals were nothing more than victor’s justice and that the convictions were wrongful. The ceremony was held before a monument that identified the convicted war criminals as “Showa martyrs.” Showa is another name for the late Emperor Hirohito,5 in whose name the war was waged. . . .

For Prime Minister Abe, just as for the ceremony’s sponsors, it is clear that each convicted war criminal is not only innocent but was himself a victim of “victor’s justice.” “Martyrs” for a noble cause. Were a contemporary German leader to make similar claims about Nazi war criminals, the roar of condemnation would be deafening, not least from within Germany itself.

While Mr. Abe’s message to the ceremony appeared carefully worded, he has in the past openly questioned whether Japan was the aggressor in the war. In a parliamentary budget committee hearing last year, he said that only Japanese were condemned for war crimes in the Pacific because the Allies were able to impose their view of events there.

Such sentiments have made him the target of criticism by China, a victim of Japan’s wartime empire-building that has accused Mr. Abe of trying to exonerate Japanese militarism.6

In light of the material presented above, there can be no question that the sponsors of this ceremony on Mt Kōya hold a similar view of Japan’s wartime actions as those affiliated with Kōa Kannon and the other Kannon-centric temples introduced in Part I of this series. In addition, and more significantly, Prime Minister Abe basically agrees despite the fact that his message “appeared carefully worded.” Thus, it is not surprising that with the recent passage by the lower house of the Diet of a series of laws authorizing Japan’s participation in “collective self-defense,” Abe and his conservative supporters are poised to turn Japan into a country that can once again wage war abroad, defying Article Nine of Japan’s so-called “peace constitution.”

Conclusion

Returning to Buddhism, the chief question to be asked is how “Buddhist” is the current pan-sectarian use of Buddhism in Japan to both valorize and eulogize the Asia-Pacific War and those who fought and died in it? Bhikkhu Bodhi, a translator of the Pali-based Buddhist canon, provides one answer:

The suttas [Skt. sutras], it must be clearly stated, do not admit any moral justification for war. Thus, if we take the texts as issuing moral absolutes, one would have to conclude that war can never be morally justified. One short sutta even declares categorically that a warrior who dies in battle will be reborn in hell, which implies that participation in war is essentially immoral. . . .The early Buddhist texts are not unaware of the potential clash between the need to prevent the triumph of evil and the duty to observe nonviolence. The solution they propose, however, always endorses nonviolence even in the face of evil.7

If the earliest teachings of the founder of a faith are considered normative for the adherents of that faith, there can be no question that neither General Matsui, Kannon as a divine general, nor those who built war memorials on Mt. Kōya and elsewhere, reflect the conduct expected of a Buddhist. However, Buddhists in the northern Mahāyāna school, including Japan, may refute this claim by pointing to sutras in their school which suggest that under certain circumstances, e.g. in the case of the conduct of a bodhisattva rather than a Buddha, the use of violence may be acceptable or at least unavoidable.

While true, this does not alter the fact that the very first precept all Buddhists, of whatever school, pledge to follow, is “do not kill.” There are no conditions or exceptions attached to this pledge. Given this, it is unsurprising that Shakyamuni Buddha would have taught “a warrior who dies in battle will be reborn in hell.” Not even Kannon is identified as having the power to save the warrior from this fate.

Nevertheless, the collaboration of religion with war is clearly not just a Buddhist problem, for which of the world’s major faiths can claim to be different in this regard? For example, Islam teaches that God is “the Compassionate” (al-raḥmān) and “the Merciful” (al-raḥīm). Christianity teaches that “God is love.” Yet these characteristics seem far removed from the wartime practice of those calling themselves Muslims and Christians, past and present. Thus, in practice, it appears these proclaimed characteristics of God have little bearing on the conduct of believers. The same may be said of the other major world religions, Christianity, Judaism and Hinduism, each of whom have been mobilized in support of aggressive wars despite criticism within their ranks.

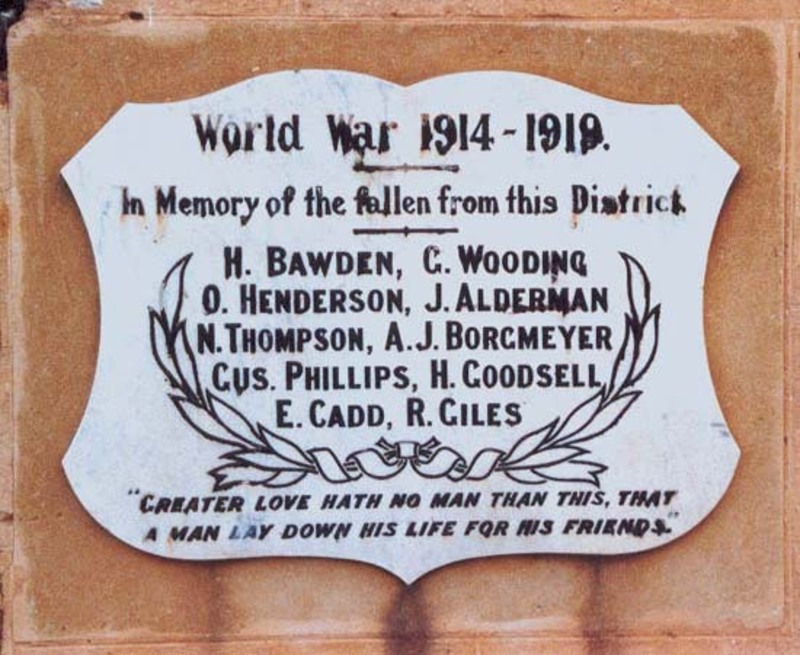

On a personal note, I remember visiting a number of war memorials located in small towns in rural South Australia. The memorials listed the names of soldiers from the town who died in Australia’s modern wars, beginning with World War I. Inevitably, there would be an additional inscription, this one from the Bible: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13). Though unspoken, the implication was clear, no matter how many of the enemy were killed, or the circumstances of the war, if it were done in order to protect one’s fellow soldiers, and by extension, one’s country, then it was a Christian act. This is despite the fact that Jesus is also recorded as having said: “But I say unto you which hear, Love your enemies, do good to them which hate you. Bless them that curse you, and pray for them who despitefully use you” (Luke 6: 27-28).

|

As attractive as it is to place the blame for Buddhism’s incorporation into war memorials, etc., solely on Japan’s Buddhist and political leaders, the root of the problem is not uniquely Japanese. That does not mean, however, that those Japanese leaders who condone, either by commission or omission, the abuse of Buddhist doctrine and practice should not be held accountable. In holding them accountable, however, we must remember that they have many accomplices in religions throughout the world. If ever the world is to be free of “holy war” it must begin with a denial that those who died (or were effectively forced to die) in a war on behalf of the narrow self-interests of their country were in any way engaged in a sacred or “holy” undertaking worthy of being eulogized by religious leaders, of whatever faith.

The Japanese have a folk expression that depicts “a teacher by negative example” (hanmen kyōshi). As this article demonstrates, war remembrance in Japan, whether by Buddhists or Shintoists, fits this category quite nicely. But as noted above, adherents of these two religions are far from the only ones in this category. In the present age, when military personnel who die in distant lands are instantly eulogized as “fallen heroes,” the reality is that few dare to challenge the way religion is used to sacralize their deaths, for doing so risks being labeled as “unpatriotic” and worse. As John Donne so presciently noted, “Ask not for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee.”8

Part I of this article is available here http://japanfocus.org/-Brian-Victoria/4353/article.html

Recommended citation: Brian Victoria, “War Remembrance in Japan’s Buddhist Cemeteries, Part II: Transforming War Criminals into Martyrs: “True Words” on Mt. Kōya, The Asia-Pacifi Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 34, No. 3, August 24, 2015.

Brian Daizen Victoria holds an M.A. in Buddhist Studies from Sōtō Zen sect-affiliated Komazawa University in Tokyo, and a Ph.D. from the Department of Religious Studies at Temple University. In addition to a 2nd, enlarged edition of Zen At War (Rowman & Littlefield), writings include Zen War Stories (RoutledgeCurzon) and Zen Master Dōgen coauthored with Prof. Yokoi Yūhō of Aichi-gakuin University (Weatherhill). He is a Visiting Research Fellow at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken) in Kyoto.

Related articles

• Brian Daizen Victoria, Sawaki Kōdō, Zen and Wartime Japan: Final Pieces of the Puzzle

• Narusawa Muneo and Brian Victoria, “War is a Crime”: Takenaka Shōgen and Buddhist Resistance in the Asia-Pacific War and Today

• Karl Baier, The Formation and Principles of Count Dürckheim’s Nazi Worldview and his interpretation of Japanese Spirit and Zen

• Brian Victoria, Zen Masters on the Battlefield (Part I)

• Brian Victoria, Zen Masters on the Battlefield (Part II)

• Brian Victoria, A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan Count Dürckheim and his Sources-D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel

• Vladimir Tikhonov, South Korea’s Christian Military Chaplaincy in the Korean War – religion as ideology?

• Brian Victoria, Buddhism and Disasters: From World War II to Fukushima

• Brian Victoria, Karma, War and Inequality in Twentieth Century Japan

Notes

1 Peter L. Berger, The Social Reality of Religion, p. 53.

2 Quoted on the following Web page (accessed 14 July 2015).

3 Slim, Defeat into Victory, p. 584.

4 In point of fact there is no single “Mt Kōya temple.” Today Mt. Koya is home to over one hundred larger and smaller temples.

5 Strictly speaking, “Showa” is the name for the period of Emperor Hirohito’s reign, i.e., 1926-1989. Thus, in this instance “Showa” simply signifies the period in which these war criminals/martyrs died.

6 Available on the Web here (accessed 1 May 2015).

7 Bhikkhu Bodhi, “War and Peace: A Buddhist Perspective” in Inquiring Mind, p. 5.

8 The main meaning of this phase is that the death of any person diminishes us all. However, a secondary meaning is that inasmuch as all of us will die one day, the bell tolls for each of us. Applied to this article, the meaning is that the difficulties both Buddhism and Shinto encounter in war remembrance in Japan are difficulties that all of the world’s main religions encounter in war remembrance, most especially in remembering soldiers who died in wars that, if only in hindsight, are now recognized as wars fought in whole or in part for national self-aggrandizement rather than genuine defense of the nation.