Translated by Norma Field

Setting out in poor health

It was April 28, 2015—my 57th birthday. I was leaving Japan to embark on a lecture tour. My mood was glum. Fatigue accumulated over the past months had left me with a case of sinusitis, and I was beginning to lose my voice. How can you be going on a lecture tour of the US when you can hardly talk, I asked myself. Moreover, it was an English-speaking world that awaited me. True, there were supposed to be interpreters. But would my story get through to the audience? Waves of uncertainty overtook me.

Back in 1991, when I was a reporter for the city news section of the Osaka office of the Asahi, I wrote an article about how an organization in Seoul had begun interviewing a halmoni (“grandma”) who had been a former military comfort woman. Three days after my article appeared, this halmoni appeared at a press conference, using her real name (Kim Hak-sun). Her courageous testimony, the first instance of a former comfort woman going public, prompted the globalization of this issue. Despite the fact that my article had referred to Ms. Kim’s having been “tricked into becoming a comfort woman,” the comfort-woman deniers asserted that it was my article that had spread the view around the world that the “comfort women were forcibly taken” and began to attack me. Toward the end of January 2014, the conservative weekly Shūkan Bunshun carried an article libeling me as a reporter who had fabricated the comfort woman issue. This, in turn, led to the escalation of attacks, including an onslaught of emails and telephone calls directed at Kobe Shōin Women’s University, where I had secured a position as part of a planned career change. My attackers urged the university not “to hire a reporter of fabrications,” which led to the cancellation of my contract. At Hokusei Gakuen University in Sapporo, where I hold an adjunct lecturer’s position, emails arrived demanding that my contract be rescinded as well as letters threatening to “kill Uemura’s daughter.”

During the past fifteen months, the attacks against me have been especially fierce. April 27, the day before my departure, was the date set for the first oral arguments in the civil suit I filed against the sources of these attacks, namely, Nishioka Tsutomu, a professor at Tokyo Christian University, and Bungei Shunjū Co., the publisher of Shūkan Bunshun. Despite my state of utter exhaustion, I was able to say everything I wanted to say in the ten minutes allotted me. You can still come through when it counts, I said, cheering myself up.

With a friend from my reporter days accompanying me, I boarded a United Airlines flight in Narita. My friend was fluent in English, and he had been dispatching news about my case to western media sources from early on. Journalists from the Hokkaido Shimbun who had also been steadfast in following me had committed to joining and covering my tour. I told myself to switch from “oral argument mode” to “US tour mode.” The abnormal situation unfolding around me had been reported to the world through such media as the web-based Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, the Guardian, and the New York Times. Concerned scholars had extended invitations for me to come speak at their institutions. Between April 28 and May 9, I was scheduled to speak at the University of Chicago, DePaul University, Marquette University, New York University, Princeton University, and UCLA. All the lectures I have been giving in Japan are the result of invitations from citizens’ and lawyers’ groups; no invitation, to date, has come from an academic institution.1

In the afternoon of April 28, University of Chicago professor emerita Norma Field met me at the airport. In the car ride into the city, we talked about a cultural journal titled Doyōbi (Saturday), which was published biweekly in Kyoto during the 1930s. It was a medium for the expression of citizen resistance to fascism. More than thirty years ago, when I encountered a reprint of that journal as a twenty-year-old, I was deeply moved. It was one of the sources of my wish to become a journalist. Norma told me of her friendship with a daughter of philosopher Nakai Masakazu,2 one of the founders of Doyōbi. “She’s coming to Otaru [not far from Sapporo] at the end of May. I’d really like to introduce you to her,” she said. Thinking back to my youthful self, I rejoiced in this curious link chance had brought to me. Our conversation grew lively, and the trip that I had contemplated with foreboding was beginning to seem pleasurable. In the five days to come, Norma would serve as interpreter as well as driver. In the course of my presentations, I was able to feel in her English the sure transmission of my words to the audience. Even though this was my first time meeting her, I felt as if I’d gained a true friend.

|

Uemura with writer, weaver, and indigo dyer Tokumura Tokiko, daughter of Nakai Masakazu, one of the founders of Doyōbi. He holds a reprint of the prewar popular front journal and she holds an issue of Waseda Journal, which Uemura, inspired by Doyōbi, helped found. At Tokumura’s benefit exhibit for Fukushima children in Otaru, Japan. Photo by Norma Field. |

Students in Chicago

On the third day after arrival, I was scheduled to speak to two classes at DePaul University and a graduate workshop at the University of Chicago. It was at DePaul University in 2007 that presidential candidate Barack Obama gave a speech in which he uttered the words, “America seeks a world in which there are no nuclear weapons.”

Speaking at DePaul’s downtown campus, I used a powerpoint that I’d prepared in the hopes of making immediately clear points that were cumbersome to communicate verbally. My first presentation was in a course called “The Ethics of Memory.” Eighteen students were present. I showed them a slide from an anti-Korean manga with a caricature of me along with slanderous captions, and I could see the surprised expressions on the students’ faces.

I went on to explain the charges leveled against me and my former employer, the Asahi Shimbun; the deniers’ focus on whether the comfort women had been “forcibly taken” and whether I had actually written to this effect; the reasons for the attacks against me; the reasons why I had filed suit; and why I felt I could not give up on this fight.

Many questions came from the students, including expressions of concern for my daughter. One American scholar in the audience even offered suggestions for her future education, which was heartwarming. I was grateful for the sense that the audience were angered by the unwarranted attacks and concerned for my family.

Professor Yuki Miyamoto, the instructor of the class, kindly sent me student responses, from both women and men, of which the following are some examples:

• The comfort women story was such a terrible part of Japan’s history, but I am thankful that Mr. Uemura decided to write about it because it helps restore faith in humanity and it teaches us that the truth will always come out.

• I am so grateful to have been able to listen to him, to listen to his brave and kind words, but to also see the courage and fight in his eyes. I will always remember this day.

• Overall, he is a great example [of] someone who is remaining strong through all the hate that he is receiving. What I appreciate the most is that even though this situation [of the former comfort women] does not particularly concern him, he is fighting with all his might to have this one memory not be erased from Japan’s past. This is not only for his wife, daughter, and mother, but for all women around the world.

• In my DePaul career I have never attended a more impactful class period or lecture. … He is not only fighting against the attacks directed at him, but he is also fighting for the memories of the comfort women. His whole story brought a new light on the topic of memory that I have never been exposed to. I had never really thought in the past how certain parts of countries history may be dark, and with that darkness comes the erasing of memories.

Though embarrassed by the extravagant praise, I was frankly happy to confirm that my story had reached this American student audience.

|

Uemura (right) with Norma Field as interpreter (left), speaking to students at DePaul University. Photo by T. Mizuno. |

Later that day at the University of Chicago workshop, a Japanese language lecturer at the University called my name and said, “I am proud to be an alumna of Hokusei Gakuin University.” Hearing Ms. Yoko Katagiri’s words, I, too, felt pride in being an adjunct lecturer at that institution.

At Marquette University in Milwaukee, approximately an hour and a half from Chicago, I was to speak at the Center for Transnational Justice 2015 workshop, “Integrity of Memory: ‘Comfort Women’ in Focus.” The workshop emerged from a prize-winning proposal by Eunah Lee, a visiting assistant professor in philosophy. The day began with the screening of Comfort Women Wanted, a 2013 video by New York-based Korean artist Chang-Jin Lee. While the screen showed partial black-and-white portraits of “comfort women” survivors from seven countries (and one Japanese soldier) who were interviewed by the filmmaker, we heard their testimonies and read the English translations, which appeared as typescript synchronized with the pace of their speech. It is an excellent work of art aiming to transmit comfort-woman testimony to the world. It has yet to be screened in Japan. I hope very much that it will be shown there.

Gaining courage from my New York experience

My talk at New York University was organized as a public event by Professor Tom Looser, an anthropologist. Approximately eighty people attended, including members of the comfort-woman denier camp. In the meanwhile, statements casting aspersions on my US tour were appearing on the Internet, such as “Insincere Japanese journalist embarking on US tour.” I arrived at the venue filled with tension but was quickly heartened as I listened to the introduction by Professor Carol Gluck, historian at Columbia University. She provided a chronological context, showing on the one hand how “nonsensical” it was to blame my article for singlehandedly sparking global and especially South Korean interest in the comfort-woman issue and how, on the other hand, the campaign against me, my family, and other reporters was nothing other than “freedom of expression … [being] trampled” and of the need to “do justice to the past” (even while the politics surrounding it have very much to do with the present.) Professor Gluck paraphrased Martin Luther King in saying, “The suppression of freedom of expression anywhere is a threat to the expression of freedom everywhere,” which I take to heart as an expression of solidarity by an American intellectual.

A question-and-answer session followed my talk. An older Japanese man spoke rapidly and vehemently. It was hard to catch all his words, but the gist of his question seemed to be “Japanese children are being targeted by Koreans. That’s because of the Asahi’s mistaken reporting, and you, Mr. Uemura, are part of that” and “Why are you trying to run away?” I responded that I wasn’t running away, that if I were, I wouldn’t be there speaking publicly. If Japanese children were being targeted, that was a violation of human rights. If there was concrete information, it should be reported to the Embassy, for instance. The argument went no further.

The Sankei Shimbun, which had also mounted a sustained attack against me, sent a local correspondent. I wondered what sort of article he would write and braced myself. But the article, headlined “Former Asahi reporter ‘subjected to bashing on comfort women’; criticizes prime minister in New York lecture” (“Moto Asahi kisha ‘ianfu de basshingu,’” May 6, 2015)3 dispassionately recounted the content of my talk. A former senior colleague at Asahi back in Tokyo wrote to say, “The article conveys what you want to say very well. It’s the sort of article that could easily appear in the Asahi itself.”

The following day, I was scheduled to lecture at the beautiful campus of Princeton Univer, lush with greenery. Professor David Leheny, political scientist and professor in East Asian Studies, was my host. The participants were Japanese and American, and I was told I could speak in Japanese, without an interpreter. That this was possible impressed me with the depth of Japan studies at Princeton. I was struck by the observation of one Japanese participant on the comfort-woman deniers: “For Americans, the Japanese who plunged into WWII and the Japanese of the postwar era are two entirely different people. Given that, it’s hard for them to understand why they [Japanese today] feel they need to defend their honor because of criticism directed at wartime activities.”

|

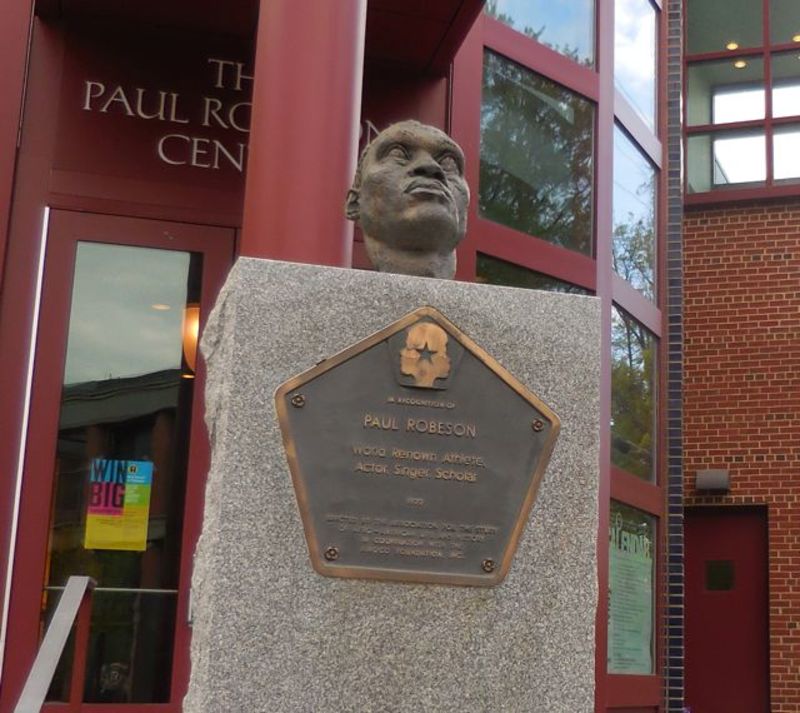

Bust of Paul Robeson. Photo by Uemura Takashi |

The following day, May 6, was completely open. I spent the day walking around the park-like town of Princeton. How long it had been since I had such free time! My spirits were renewed as I walked around, seeing squirrels peek out from behind tree trunks. An email came in from Norma Field, who had served as driver and interpreter for the first half of my tour. Since she had gotten her degree at Princeton, I wondered if she was sending me tips about things to do.

In fact, her email said, “Princeton is the birthplace of the great singer, athlete, and activist Paul Robeson. Please take your time and enjoy walking around the town.” I had never heard of the African American Paul Robeson (1897-1976), who fought racism and McCarthyism. I went straight away to a used record store near my hotel and bought two CDs. The next morning, I went to see a bust of Robeson. Reflecting on the indomitable spirit that had governed his life helped me gather my own courage.

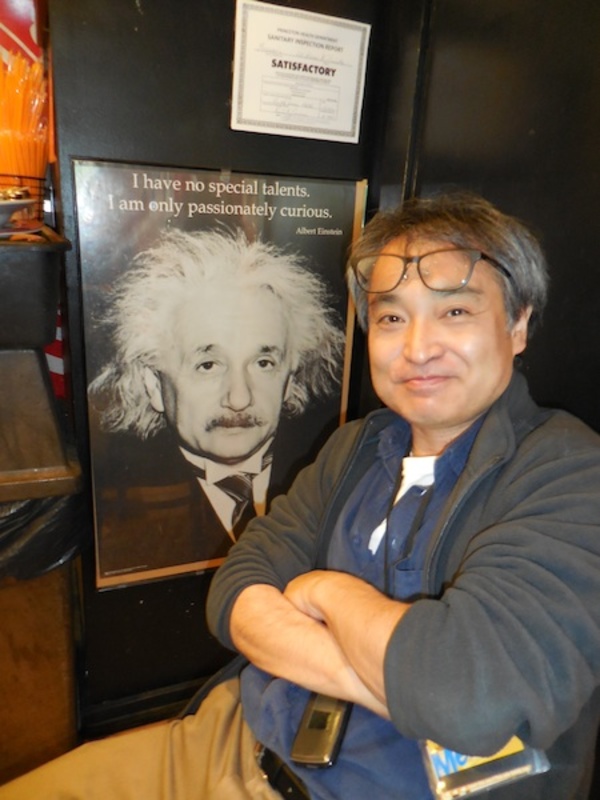

A pizza shop in town had a poster of Dr. Albert Einstein (1879-1955) on its walls. I had a picture taken of myself next to it. Einstein became a refugee from the Nazis and settled in the US and spent the latter part of his life at Princeton. I read that he was committed to antiracism and had a cordial relationship with Robeson. Learning about Einstein and Robeson was an unexpected side benefit to my stay at Princeton.

The “Open Letter” becomes a wind in my sails

My US tour (April 28-May 9) overlapped in part with Prime Minister Abe’s visit to the US (April 26-May 3). I read about his speech of April 29 in the papers during my stay in Chicago.4 Even though the speech deployed the phrase “deep remorse” about WWII, it made no mention of the comfort woman issue, or “colonial occupation” or “apology.” The Korean and Chinese media responded with displeasure.

On May 5, after the prime minister’s visit, a letter signed by 187 historians and other scholars of Japan was released that urged Abe to “act boldly” on the issues he raised in his speech, including human rights, human security, and the suffering caused by Japan in WWII. Friends in Japan wrote to tell me about the contents of the “Open Letter in Support of Historians in Japan,” published in both English and Japanese.5 As I poured over this text, I was moved by a powerful sense of encouragement. Among the signatories, I noted seven who were involved in my tour.

|

Uemura with poster of Albert Einstein. Photo by Tokosumi Yoshifumi |

I was especially emboldened by the declaration that “Employing legalistic arguments focused on particular terms or isolated documents to challenge the victims’ testimony both misses the fundamental issue of their brutalization and ignores the larger context of the inhumane system that exploited them.” Given that comfort-woman deniers had attacked me for having written as if the comfort women had been “forcibly mobilized” and for having referred to the “Women’s Volunteer Corps,” this passage struck me as demonstrating that in the common sense of scholars around the world, I was not a “reporter of fabrications.”

My last stop was UCLA, where Professor Katsuya Hirano had organized a public event. About 140 people had crammed into the hall. Ms. Lee Yong-soo, a former Korean comfort woman who was visiting the US was present, as well as several Japanese comfort-woman deniers. The weekly Shūkan Bunshun, which had kept up a steady stream of attack against me, had sent a reporter from Tokyo. I wanted to share with the participants my sense of the significance of the “Open Letter.” I was especially moved by the sentence, “The process of acknowledging past wrongs strengthens a democratic society and fosters cooperation among nations.” To reflect on past wrongs, to apologize for them, to transmit them to the future, will surely contribute to the effort to prevent the recurrence of war and human rights violations. Such acts would strengthen democracy in our society and advance reconciliation with East Asia.

It was good for me to visit the US. I was able to meet many people, including scholars. I learned about those who had gone before me in the fight for human rights and equality. During my twelve days in the US, my circles were expanded and my courage bolstered. I recovered my health. And I became convinced that my struggle was part of a struggle to safeguard democracy in Japan. Upon my return to Japan, friends and colleagues alike said, “You seem really cheerful since you got back.” My convictions were reinforced and my strength boosted. I would like to convey my thanks to everyone who helped arrange this trip. I would also like to thank my friend and the journalists from Hokkaido who accompanied me.

Shūkan Bunshun, which sent a reporter to UCLA from Tokyo, ran an article in its May 21 issue titled, “Former Asahi reporter criticizes Bunshun on US barnstorming; Uemura Takashi caught red-handed in LA.” The article closed with the line, “Will this unrepentant journey of self-vindication continue?” I will never be “repentant” in response to the unjustified attacks directed at me. It is rather Shūkan Bunshun that should repent its efforts to demean me. I intend to continue my journey of struggle. The “Open Letter” has been joined by European and other researchers and is said to have 457 signatories as of May 19.

Let me conclude by repeating the words with which I concluded my talks in the US: “I will fight. I cannot lose this fight.”

Uemura Takashi is a former reporter for the Asahi Shimbun (1982-2014) and currently an adjunct lecturer at Hokusei Gakuen University in Sapporo. 1991 he wrote two articles on the first “comfort woman” to come forward, Ms. Kim Hak-sun. He has been criticized as the “reporter who triggered the comfort woman issue” with “fabricated” articles. Intense attacks against him and his family became a major social issue in 2014. Aside from work experience in the city news sections in Osaka and Tokyo, Uemura also worked at theAsahi’s Teheran, Seoul, and Beijing Bureaus. He ended his career at theAsahias chief of the Hakodate Bureau.

A version of this article, in Japanese, appears as “Futō na basshingu ni kōsuru Amerika no tabi,” Tsukuru (September 30, 2015), 114-23.

Please see parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 of this series.

Norma Field retired from the University of Chicago in 2012. Her most recent work is the co-translation of the ebook Fukushima Radiation: Will You Still Say No Crime Was Committed?

Recommended citation: Uemura Takashi, translated by Norma Field, “A Chronicle of My American Journey: The Things I Learned”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 33, No. 5, August 17, 2015.

Notes

1 Since his return from the U.S., Uemura has received several invitations.

2 See Leslie Pincus, “A Salon for the Soul: Nakai Masakazu and the Culture Movement in Postwar Hiroshima” (1997). On the “Children’s Village” movement sustained by Nakai’s daughter Tokumura Tokiko and her husband Tokumura Akira, see Pincus, “On the Shores of Japan’s Postwar Left: An Intimate History” (2015).

3 This is the title given to the print version of the article; the internet version, somewhat longer, is titled, “Mr. Uemura Takashi, formerly of Asahi, criticizes Prime Minister Abe in NY; Ms. Sakurai Yoshiko and others also say ‘I will not lose this fight!’” (“Moto Asahi no Uemura-shi, NY de Abe Shushō o hihan; Sakurai Yoshiko-shi ra mo ‘Watashi wa kono tatakai ni makenai!’”). Ms. Sakurai herself is not, however, quoted in the article.

4 The text of the speech in Japanese and English may be found on the kantei (prime minister and cabinet) website.

5 See text updated with additional signatories as well as May 25 statement by 16 Japanese historical associations, in English and Japanese, here.