The Unasked Questions

Angus McDougall, an Australian serviceman, was captured by the Japanese in the early stages of the Asia-Pacific War and sent to Changi prisoner of war camp. From there he, like over 40,000 others, was transported by rail to Banpong in Thailand on his way to work on the Thai-Burma Railway. The journey was gruelling. POWs were packed 28 or more to a truck in goods wagons. The trucks were far too small to carry such a number, the heat was intense, and food and water were scarce. Interviewed about his experiences many decades later, McDougall echoes other survivors in describing the journey as “hell”.1

But, as you can hear if you listen to his recorded interview on the website of the Australian War Memorial, McDougall then goes on to make a remark that catches his interviewer unprepared: “You don’t want to know about the girls and everything in the truck?” he asks. “Girls in the truck?” echoes his interviewer in surprise. McDougall responds by explaining that alongside the POWs, their train also transported 25 to 30 “comfort girls”, as he calls them: “one carriage of them, with guards, same as we had, like the guards with us”. These girls, McDougall recalls, were not Japanese, but a multiethnic group made up (he thinks) of “Malays, Indians, Chinese and others”. Transported like prisoners, in the same hellish conditions on the same military train, the young women were on their way to Japanese army brothels in Thailand or Burma.2

But McDougall’s assumption was right. His interviewer evidently did not “want to know about the girls”, and briskly moved the conversation on to other topics. The pattern is repeated again and again in the oral history record of the Asia-Pacific War. From the 1980s to the first decade of the twenty-first century, historians undertook a massive task of recording many thousands of interviews with former allied service people and civilians who participated in one way or another in the war. These interviews provide an astonishingly rich record of many long-neglected aspects of mid-twentieth century history. But the references to Asian “comfort women” which from time to time emerge in this record are very rarely followed up. Fleeting descriptions of encounters with Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Indonesian and other women recruited into Japanese military brothels all over Asia are left frustratingly hanging in silence, a thousand questions unasked and unanswered.

The silences reflect the widespread attitudes of allied service people during wartime. The ubiquitous presence of Japanese military brothels in China and Southeast Asia was regarded sometimes as a subject for criticism, more often as a curiosity. But in either case, it was seen as an issue of relatively little importance compared to other all-consuming concerns of war. Frederick Arblaster, an Australian translator who had learnt Japanese and was sent to the Dutch East Indies to assist with post-surrender interrogations, recalls encountering a group of women who were with newly-surrendered Japanese forces. A Japanese officer, asked about the women, insisted that they were Red Cross and hospital nurses, but Arblaster noticed their clothes and powdered faces and observed “they’re the funniest looking Red Cross and hospital staff that ever I saw in my life”. He asked his commanding officer for permission to question them, but the brusque reply was “don’t waste your time, sergeant. Let’s go”. Some time later Arblaster realised that they must have been “comfort women”, and regretted having failed to talk to them:

I’m sure that if they [his commanding officers] had accepted my view that there was something wrong there, then we could have spent some time… Once I’d spoken to these women, I’d have found out, and arrangements could have been made to look after them. But any way… I can still see them. It was so incongruous to see these women in the jungle.3

Until quite recently at least, British, American and Australian war historians seldom showed more interest in the stories of such women than Arblaster’s commanding officer. When oral history interviewees mention encounters with “comfort women” in China, Southeast Asia or even in India, the interviewers rarely pursue the matter. British missionary Norah Inge, who had been in charge of a section of the civilian internment camp for Japanese in Deoli, India, volunteered the information that in the latter stages of the war some Japanese “comfort women” found by British troops in various parts of Southeast Asia were transported to Deoli, where they were held in their own separate compound.4 But in several hours of fascinating recording, her interviewer does not pose a single follow-up question about the story or about fate of these women, instead immediately steering the conversation back onto more familiar territory.

Despite this lack of interest, the traces – passing mentions, sketchy anecdotes, tersely labeled photographs – remain on the record, and provide glimpses of important but neglected facets of the “comfort women” issue. These traces remind us that many non-Japanese witnesses observed the presence of Japanese “comfort women” throughout wartime Asia, and some were able to bear testimony to the conditions in which women were transported or kept in brothels. At the same time, this testimony, and the context in which it was given, makes it necessary to confront difficult questions about the sexual abuse of women not only by Japanese troops but also by other armed forces in Asia. Historian Hank Nelson made powerful use of the testimony of allied soldiers to explore the history of the women transported to brothels in New Guinea by Japanese forces during the war.5 Here, drawing particularly on the wealth of records in the Imperial War Museum and the Australian War Memorial, I retrieve other traces from the spoken, written and visual records left by allied troops and civilians in Asia, and consider what they add to our knowledge of this troubling and contentious issue. The material presented here is, I think, just the tip of an iceberg of third party testimony to the history of the “comfort women”. Much has surely been lost, or soon will be, as the generation with personal memories of the war disappears. But there is certainly more to be found, and I hope that this essay will contribute to the gradual process of bringing evidence together, deepening our understanding of that history and of its implications for the present and future.

|

Kupang, Timor, A group including twenty-six Javanese women who were liberated from Japanese brothels, 2 October 1945. Photographer K. B. Davis; AWM 120082 |

Sources of Contention

The question of historical sources lies at the heart of the bitter contemporary disputes about the “comfort women”. Those who deny that the Japanese military forcibly recruited women to brothels, or who dismiss the issue out of hand, commonly draw a sharp distinction between official documents and oral testimony, discounting the latter or focusing their energies on parsing specific pieces of testimony in order to undermine their credibility. But both written and oral historical source materials are created by human individuals with human strengths and weaknesses. Why should we privilege one over the other? The bureaucrats who compose an official document are neither more nor less likely to present a full and accurate picture of the truth than elderly women who tell the stories of their past.

The “denialists” claim that there are no official documents proving the involvement of the Japanese military in the forced recruitment or incarceration of “comfort women”. These claims play down the fact that many official military documents detailing the establishment, running and regulation of “comfort stations” have been unearthed by historian Yoshimi Yoshiaki and others. These include several sets of regulations for “comfort stations” which deny women freedom to leave military brothels.6 Other official documents show that recruiters selected by the military police were dispatched (for example) to Taiwan to collect specified numbers of “native women” for military brothels in Borneo.7

The rhetoric of denial dismisses the oral testimony of women who speak from personal experience, arguing that this testimony is unreliable or fabricated – despite the fact that some of the personal accounts have been tested in Japanese and other courts of law and found to be credible.8 Events like those in Mapanique, the Philippines – where women kidnapped by Japanese troops after the massacre of the village’s male population were held in a house where they were repeatedly raped – are ignored, even though judicial rulings have acknowledged the sufferings of the victims. Despite rejecting a claim for compensation on technical legal grounds, in 2014 a panel of presiding judges in the Philippines expressed great sympathy with the cause of the surviving Mapanique women, commenting: “we cannot begin to comprehend the unimaginable horror they underwent at the hands of the Japanese soldiers”.9 Denialists also either reject or ignore materials like the Dutch parliamentary report of 1994, which found, not only that some European civilian internees had been forcibly taken to Japanese military brothels, but also (for example) that in West New Guinea, Papuan women whose husbands had been killed for anti-Japanese activities were among those required to serve as “comfort women”.10

To understand history, we need to place multiple records side by side in ways that allow them to illuminate, confirm, refute or enrich each other; and we need to think carefully about the processes through which all historical records – written, spoken or visual – are created and destroyed. This involves reflecting on the human motives behind the making of records of all kinds. History is always intertextual. It involves comparing and assessing the wealth of resources; for it is the testimony of many independent witnesses and records that allows us to piece historical events together. The materials presented here, like other historical records, have their own particular strengths and limitations. They add to, and should be read alongside, the abundant evidence already presented by Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Sarah Soh, Yuki Tanaka, Hank Nelson and many other scholars.11

The oral, written and visual record left by allied troops and civilians in war time Asia is very diverse, reflecting the complexity of the military and colonial presences in the region. Many British, Australian and other servicemen during the Asia-Pacific War had deep-seated prejudices towards Asians, and many had views of women that would now be considered profoundly sexist. Mary Louise Roberts observes in her study of US soldiers in wartime France that “sex was fundamental to how the US military framed, fought and won the war in Europe. Far from being a marginal release from the pressures of combat, sexual behaviour stood at the centre of the story in the form of myth, symbol and model of power”.12 The same might be said about British, Australian and American – and of course Japanese – military forces in wartime Asia. The violence and the artificial sex segregations of war created fevered worlds of erotic fantasy which echo in the recorded memories of many servicemen, and the fantasies sometimes spilled over into actions. When British, Australian, American and other servicemen speak of encounters with “comfort women”, they often do so with a half jocular and half embarrassed laugh. You can hear the nudge and the wink in their voices. Many of them too, of course, had frequented prostitutes at some point in their military careers – a fact that opens up spectres of comparison to which I shall return.

But their stories, and the photographs and films they brought back from Asian war zones also provide glimpses of events that no other records preserve. And the ways they tell their stories are remarkably diverse. Some Commonwealth service people, for example, express bitter hostility toward the Japanese; but other soldiers and civilians, even in wartime, felt overt admiration for Japanese individuals whom they encountered. Norah Inge, for one, speaks with warmth and affection of the detainees she supervised. She had known a number of them before the war, and maintained friendships with some after its end.13 Eyewitness descriptions of encounters with “comfort women” need to be placed in the context of the lives and personalities of the witnesses. Every film and photograph too, of course, expresses a personal point of view.

|

Building believed to have been used as a brothel during the Japanese occupation of Lae, New Guinea; AWM 099134 |

A Far-Flung Network

Placed side by side, these multiple records convey important messages. First, they emphasise the scale of the Japanese military brothel network in wartime Asia. This does not help us to make any accurate estimate of the numbers of women recruited, but it does reinforce the impression that the number was very large. Leslie Lyall, a British missionary in China, first encountered “comfort women” in 1937 or 1938, when the Japanese commander of a newly occupied area of Hebei Province took over the local church for use as a brothel. Hearing the news, Lyall confronted the commanding officer, who agreed to move the women to “other premises”, thus acknowledging his own determining authority over their presence. Lyall observes that “as soon as they occupied a city they [the Japanese military] brought in Korean prostitutes”. Interestingly, Lyall does not express any interest at all in the fate of the women. He just seems glad to have his church cleansed of the blemish of prostitution.14

Eleanor May Clarke, the daughter of a British colonial judge and a princess from the Shan States, spent the war at school in occupied Burma, and left a fascinating account of her experiences. She recalls that there were “lots of” Korean “comfort women” in Burma: the local people referred to them as “Mei-Chosen”. She remembers an expedition with two other children to the outskirts of Rangoon, where

we saw this house, and all the Japanese soldiers coming down from it, and I remember the three of us were standing there looking up at it, and then there were these…, they were doing up their trousers, and then we suddenly realised: oh, that’s where the… we call them Mei-Chosen, you see… They came from Chosen [Korea], you see… Mei is sort of women – women or, if you say mei, it’s ‘mother’, you see, it’s a term used for women. So we said ‘oh, that’s the house of the Mei-Chosen’.15

|

“Chinese and Malayan girls forcibly taken from Penang by the Japanese to work as ‘comfort girls’ for the troops”. Photographer E. A. Lemon; IWM SE 5226 |

These archives are full of telling reminders of the huge geographical extent of the “comfort station” network, and of the vast distances over which many women were transported. One photo taken by British troops at the end of the war in the Andaman Islands shows a group of “Chinese and Malayan girls forcibly taken from Penang by the Japanese to work as ‘comfort girls’ for the troops”. In Kupang, East Timor, allied troops arriving to take the surrender found twenty-six women from Java who had been brought to work in the military brothel there. Like the “comfort women” whom Frederick Arblaster encountered around the same time, these women had been “camouflaged” as nurses by the Japanese military, who had issued them with Red Cross armbands on the eve of the surrender. A striking and enigmatic photo shows one of the women, radiantly smiling, holding a small white china doll in one hand.16 Is the doll a gift from arriving allied troops? A treasured possession that she had somehow managed to hold on to during her time in the military brothel? An item salvaged from war damaged Kupang?

|

One of twenty-six Javanese Kupang who were liberated at Kupang from Japanese brothels, 2 October 1945. Photographer K. B. Davis; AWM 120083 |

The record remains silent on so many things. But the issue of distance matters. In wartime, as in contemporary human trafficking, the further people are removed from their homes, the greater becomes the power imbalance between the transporters and the transported. Women who work in brothels in their home towns are vulnerable to gross exploitation and sexual violence too; but there remains at least a possibility of flight to some familiar point of shelter, or of contact with acquaintances who may help in times of desperation. Women transported across half a continent to an unfamiliar place lose those possibilities. Unfamiliar landscape and unknown language can become a kind of prison. Even at war’s end (as we shall see) escape was a flight into a dangerous and utterly unpredictable world.

Not only were many women thousands of miles from home; many were constantly on the move in extremely harsh conditions. Several Commonwealth soldiers who were POWs in Southeast Asia speak of “comfort women” being trucked in to their guards’ camps at regular intervals: part of a system of mobile brothels circulating around the Japanese military bases of the area. And as the Japanese forces retreated towards the end of the war, the advancing allies would find abandoned “comfort stations”, whose inhabitants had presumably been taken by the retreating troops on their gruelling marches through unforgiving terrain, only (as we shall see) to be abandoned at the final moment of defeat.

Degrees of Servitude

The testimony of Commonwealth soldiers and civilians also reinforces an important message of earlier research on the “comfort women” history: that the conditions in which women were recruited, transported and kept varied greatly, so a single case can never be generalised to describe the system as a whole. Angus McDougall’s encounter with the women on the POW train, for example, can be placed side by side with the account of Francis McGuire, a Scottish POW taken to work on the Thai-Burma Railway. During his interview, McGuire was asked whether any Japanese he encountered in Thailand or Burma was ever kind to him. He starts to say “no”, and then corrects himself, recalling a single instance of kindness, when he was being held at a POW camp in Thailand:

A train with some carriages was moving up the railway to go over the border into Burma, and it stopped at our camp there. We were ordered to parade in front of the trucks where the top brass – generals, colonels, majors – were all on board that train. Also on that train were what was known as “comfort ladies”. You can guess what I mean. They leaned over, and whatever they had in the shape of cigarettes, sweets and money they gave us. The Japanese military paid no attention – just let it be.17

In some cases, POWs were put to work building or maintaining “comfort stations”. British officer Geoffrey Pharaoh Adams recalled how twenty of his fellow prisoners were sent as gardeners and cleaners to a hot spring resort in Hindato, Thailand, where they found a large Japanese military “comfort station” divided into separate sections for officers and other ranks. These POWs, like McGuire, described the kindness of the women, who gave them “food, cigarettes and as much water as they wanted to drink, and occasionally a drink of beer”.18 The Hindato brothel was clearly very different from the one constructed by another group of POWs including John Barratt, a British army captain who described being “put on building a line of bamboo cubicles and, before long, a number of Japanese ‘comfort girls’ arrived up the railway in trucks. They were taken to the cubicles and we watched them getting ready and testing ‘French letters’ by blowing them up. Before long they had the equivalent of a platoon of Jap soldiers in a queue opposite each cubicle”.19

|

Second World War period wooden sign which was reputedly taken from the door of a Japanese brothel, sometime in Burma, 1944; IWM EPH 5425 |

The large abandoned Japanese military brothel found by Commonwealth forces at the hill station of Kalaw, Burma, had also been divided into cubicles with bamboo screens and had a ticket booth outside the front door, but it contained a pink ceramic bathtub and “they’d got branches of trees with little bits of pink tissue paper all over them to simulate cherry blossom”. By contrast, British POW Thomas Coles, sent with others to repair a Japanese military brothel on Haruku Island in Indonesia after a bombing raid, found that the brothel’s toilets were “sea latrines”, “a bamboo contraption” which the women reached by walking along a narrow gangplank over the sea, exposed throughout to the prying eyes of male observers. Coles is disparaging about the appearance of the women he met there: he found their white-powdered faces distasteful. But, he too remembers their kindness. One woman “gave me a Davros cigarette, which was a tailor-made, machine-made cigarette. At this time we’d be lucky to roll native tobacco in banana leaves and puff away, but this tailor-made Davros was absolute nectar, and I can see the face now of this poor female that gave it to me”. Despite the difficulties of communication with these “comfort women”, Coles recalls that “they more or less intimated that they were suffering under the Japanese heel as much as we were”.20

When listening to these stories, it is important to distinguish questions of living conditions from questions of free will. The women who traveled to Burma alongside the military “top brass”, or who worked in the officers’ section of the Hindato hot spring brothel, clearly had more comfortable physical conditions than those transported in POW freight trucks and put to work in places like the Haruku brothel. But this does not tell us which, if any, of these women had volunteered for the work. Even many of the Japanese women who had worked as prostitutes before the war, and who were transported to distant places as “comfort women”, had originally been sold into prostitution by their families or tricked by unscrupulous brokers. The fact that some women received money, sweets or beer does not tell us that they were free agents: it does not tell us whether or not they had been forcibly recruited, or whether they were free to leave.

This issue is crucial to contemporary controversies about the use of terms such as “forced transportation” [kyōsei renkō] or “sexual slavery” [sei doreisei]. Though methods of recruitment were diverse, I find it difficult to imagine what term other than “forced transportation” can be used for women and girls transported under Japanese military guard in POW trucks. But even those who reached their destinations by more comfortable means were not necessarily “free”. On the question of “sexual slavery”, those who object to the term often interpret “slavery” as meaning “being forced to work without pay”: a definition still used by some anti-slavery movements today.21 But the more common contemporary understanding of “slavery” is that the defining characteristic of enslavement is not lack of monetary payment, but denial of freedom.

The United Nations’ 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, for example, defines a range of “institutions and practices similar to slavery”, which it seeks to abolish. These include:

a) Debt bondage, that is to say, the status or condition arising from a pledge by a debtor of his personal services…, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied towards the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined…

(c) Any institution or practice whereby:

(i) A woman, without the right to refuse, is promised or given in marriage on payment of a consideration in money or in kind to her parents, guardian, family or any other person or group…22

The last point surely applies equally well to those contracted into prostitution through promises to parents, family or others.

One of the most detailed descriptions of a single instance of recruitment of Korean “comfort women” comes from the testimony, recorded in US intelligence reports, of a Japanese brothel operator named Kitamura and of twenty women whom he transported from Korea to Burma.23 Kitamura ran a brothel on behalf of the Japanese military in Myitkyina, southern Burma, and he and the women were captured by allied troops in 1944 as Japanese forces crumbled in the face of the allied assault. Although sections of this testimony have been widely discussed, the material is worth re-examining, both because it provides a vivid picture of the use of debt bondage by the Japanese military, and because its content is frequently misquoted or misinterpreted by right-wing commentators in Japan.24

Kitamura had owned a restaurant in Seoul before the war, and described to his captors how in 1942 the Japanese army headquarters in Seoul suggested to various Japanese businesspeople in Korea that they could make money by collecting Korean women, transporting them to Burma and setting up military brothels in which the women would be put to work. Since Kitamura’s restaurant was struggling financially, he jumped at the opportunity, and “purchased 22 Korean girls, paying their family between 300 and 1000 yen according to the personality, looks and age of the girl”. These young women became the “sole property” of Kitamura and his wife.25 The allied interrogation of twenty of the women shows that they had been duped into believing that their work would be to visit the wounded in hospital, roll bandages and perform other similar tasks.26

Kitamura and his wife took the twenty-two women to Busan, where they joined a large contingent of Korean women recruited at the same time for the Burma front. On 10 July 1942, a total of 703 Korean women collected during this recruitment drive were put onto a 4000 ton vessel and shipped from Busan to Rangoon in a convoy. Their fares were paid by the Japanese army headquarters in Seoul, while the brothel operators, who were to reap the financial profits of this collaborative venture, paid for the women’s food. On the way, the ship stopped to collect more women from Taiwan and Singapore.

Kitamura’s brothel in Myitkyina operated under the supervision and regulation of the imperial army’s 114th Infantry Regiment. Soldiers paid money directly to the “comfort women”, who had to hand over at least half of the payments to the brothel operator. Kitamura reported that on an average day around 80-90 non-commissioned officers and enlisted men and around 10-15 officers visited the brothel for sex. The information he gave enables us to estimate that initially, on average, each woman would probably received around 300-350 yen per month, of which she would have kept about 150-175 yen, handing the rest to Kitamura.27 This sum decreased after a highly unpopular commander of the Myitkyina garrison (himself reportedly a frequent visitor to the brothel) cut the prices paid by officers and NCOs (though not those paid by enlisted men). In any case, money earned in the Myitkyina brothel may not have gone very far, for the operator made additional profits “by selling clothing, necessities and luxuries to the girls at exorbitant charges”.28 Whatever their takings, the women were required to hand over a minimum of 150 yen per month to the Kitamuras, so those who were unable to earn that much because of ill health or for other reasons would have sunk deeper into debt. The original contracts stated that once they had repaid their family’s debt, plus interest, they would be given free passage back to Korea (though it is not clear what rate of interest was charged). But in fact, “owing to war conditions”, none of the women bought by Kitamura was actually allowed to return home: the “one girl who fulfilled these conditions and wished to return was easily persuaded to remain”.29

The account fits quite closely with other testimony of debt bondage and recruitment by deception, but it too is just one case, and cannot be universalised. Kitamura’s story too needs to be read alongside others, like the interrogation report of a Chinese man who had been taken prisoner of war by the allies after working with Japanese forces in Thailand and Malaya: “I have seen with my own eyes Japanese young officers and soldiers raiding Chinese homes where they thought they could get some young Chinese girls”.30

In practice, forcible recruitment and denial of freedom take many forms, including direct physical violence, the use of threats and deception, and the use of various forms of debt servitude. The evidence shows that, although they were not universal, all of these practices existed within the Japanese military “comfort station” system, and some (for example recruitment by deception or debt bondage) were particularly widespread.

Acts of Abandonment

The record in the Commonwealth archives also focuses attention on an issue that has been little debated. What happened to the women when the war ended? The nature of the recruitment of “comfort women” has been the subject of ferocious debate. But the problem of historical responsibility is wider than that. The evidence shows that the Japanese military, having transported “comfort women” all over East and Southeast Asia, abandoned them to their fate at the time of the surrender. Historical responsibility derives from the moment of abandonment as well as from the moment of recruitment, and from the events in between.

William “Tug” Wilson was a Liverpool shipyard worker who had joined the Royal Artillery and was sent during the war to India and then to the Burma front. He was stationed at Kohima in the northeast of Burma, from where he participated in the advance on Rangoon. At the end of a long interview recorded in the year 2000, he tells a vivid and chilling story of an encounter during that advance through the Burmese jungle:

Two of us were crawling along, and I saw two sticks, like this. I said, ‘That’s peculiar. They’re straight, and nothing grows straight in the jungle”. And then I crawled up there and had a look around, and I saw a toenail, and a toenail there, so I picked up the feet, and it was two… We found two geisha girls. They couldn’t keep up with them, so they just shot them and buried them.31

|

Labuan, private house in Fox Road used by the Japanese as an Officer’s club and brothel, September 1945, AWM P02919.057 |

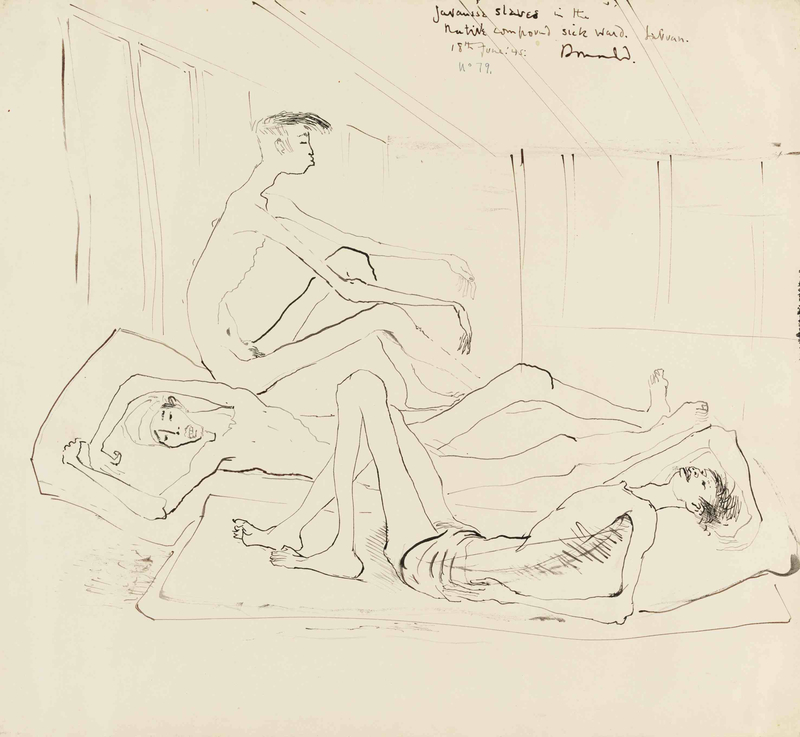

An equally chilling image is left by the acclaimed Australian war artist Donald Friend, who was sent to record the surrender of Japanese troops in Labuan, Borneo. His diaries are a stark record of his horror at what he encountered there: not only at the havoc wreaked by the Japanese occupation, but also sometimes at the behaviour of the victorious allies. He expresses disgust, for example, at the actions of some Australian troops, who salvaged “trophies” from the bodies of their former enemies. As he wrote in his diary while in Labuan, he struggled to find artistic expression for “the enemy’s atrocities [and] our own less frequent but hardly less shameful barbarities”.32 A particularly dark moment was his encounter with the hospital in Labuan, filled with emaciated and dying labourers who had been transported by the Japanese military from Java to Borneo. Most were in the final stages of death from malnutrition. Friend’s sketches graphically depict the scene in the men’s section of the hospital. The accompanying notes read: “the Javanese were promised good jobs and pay; the men worked on the airstrips; the women, brought over ostensibly for office jobs, were put in brothels in Labuan”.33

|

Drawing by Donald Friend, Depicts the emaciated natives of Java, shipped to Borneo by the Japanese from that island during their occupation of Java; 1945; AWM ART23229 |

We have no way of knowing how many women, transported to “comfort stations” across Asia during the war, were killed or left to die in the war’s final stages; but some certainly were. Others found their way home, either by their own devices or with the very uncertain help of the arriving allied victors. As the Japanese forces crumbled, some women fled brothels and sought the protection of arriving allied troops. One dishevelled woman wandered into a British army camp on the Thai Burma border in 1945, having escaped from Japanese forces who had held her as a prostitute. Her nationality is unclear, though she seems to have understood Burmese. She proceeded to give the British commanding officer detailed information about the movements of Japanese troops.34

Some “comfort women” managed to bring belongings or money with them when they fled. An unnamed British officer serving in Burma at the end of the war was approached by a group of five Korean “comfort women” who, in the chaos of the Japanese retreat, had escaped from the brothel where they had been held. They pleaded for his protection. Although they were bedraggled from their perilous march, they had managed to obtain a large amount of “banana money” (the Japanese military currency issued during the occupation, by then almost entirely worthless), and had wrapped it in condoms to protect it from the tropical downpours. They were sent to the brigade headquarters, but what happened to them afterwards is unclear.35

Another group of fifteen Korean women fled from a Japanese military brothel in Ubon, Thailand, and sought refuge with British military intelligence officer David Smiley, who was engaged in overseeing the surrender of Japanese forces in the area. Remarkably, Smiley’s first response to their plea for help was to consult with the Japanese officers about the women. The Japanese military told him that “they had paid the girls 10000 ticals (or bahts) for services that they did not consider had been rendered, and they were therefore reluctant to let them go”. Smiley proceeded to produce an “official” document writing off the women’s debts (which would have amounted to about $32 per head in the values of the time) and found them a house, where they were guarded by Thai police “for their own safety”.36 The incident is significant not least because it indicates the Japanese military had paid the women (or possible their families) in advance and then treated the payment as a debt which bound the women to work for them. The women described at length how they had been held against their will, but Smiley’s response to their story, and to the women themselves, is audibly dismissive.

|

A Chinese girl from one of the Japanese Army’s ‘comfort battalions’ awaits interrogation at a camp in Rangoon, IWM SE 4523 – Note: This very young looking girl is not among the five who appear in the Imperial War Museum film |

Many women fled empty handed. The Imperial War Museum holds moving fragments of film taken by two army cameramen for the Southeast Asia Command Film Unit. They show five Chinese “comfort women” arriving at a camp in Burma where bedraggled and wounded surrendering Japanese troops are being processed.37 The women are barefoot, and carry nothing but the clothes they are wearing and the small towels that two women have wound around their necks. The film is silent, so we cannot hear their voices; and although they are questioned by British troops and are filmed signing papers, I have been unable to find any documentary record of their story.

It is uncomfortable watching the film. These women have not chosen to be filmed, and we are observing them in a moment of particular confusion and anxiety. They sit in a row on the step of a wooden porch while a large Caucasian soldier with bare chest and a cigarette dangling from one hand stands, towering over them, as he attempts to question them (although it is unlikely that he and they have a language in common). Their faces express the varied reactions of people responding to a bewildering moment of hope and fear. Some smile, or giggle shyly behind raised hands. One slightly older-looking woman – perhaps in her thirties – remains calm and smiling throughout. Another very young woman sits with her head bowed and an expression of profound misery and despair on her face. In the final shots we see three of them, still barefoot and clad in the same clothes, clambering on to an army truck for the journey to an unknown destination. What happened to them afterwards?

We can only imagine the terror involved, after years of sexual suffering at the hands of one military force, in entrusting oneself to the hands of another unknown army. Some sense of that terror is captured in a passage from the unpublished memoirs of a British army major, George Mailer-Howat. He describes how his unit arrived at the Burmese oil refining town of Syriam (now called Thanlyin), where they found “a group of frightened Korean girls”. The young women had fled from a Japanese military brothel, and, Mailer-Howat writes:

they had evidently been kidnapped and forced against their will to become virtual slaves for the Jap soldiers. They were terrified and amazed when given tea and a meal but very grateful when we handed them over to the Military Police to be rehabilitated and through a local Burmese interpreter told them that they would be looked after.38

Allied Forces and the “Comfort Women”

Were they looked after? The Japanese authorities bear responsibility for recruiting and using these women and then abandoning them in the violent chaos of post-defeat East and Southeast Asia. But the allied forces too had no coherent response to the problems faced by these scattered, frightened and often destitute groups of women. The issue appears to have been dealt with in an ad hoc way by troops on the ground. In the end, it seems that a number of Japanese and Korean “comfort women” from Thailand and perhaps also from Burma were taken to Bangkok, from where they were repatriated on allied naval vessels. A British military cameraman was sent to film the scene, but at the crucial moment his camera broke down, leaving us with yet another blank in the historical record.39 We do have fleeting shots of Japanese (and possibly also Korean or Taiwanese) “comfort women” in Manila in October 1945, boarding Japanese ships requisitioned by the allies for the journey home.40 There is evidence too that some Australian naval vessels were used to repatriate the surviving Javanese “comfort women” left stranded across the Indonesian archipelago at the end of the war. An Australian crew member, interviewed in 2002, recollected a ship from his squadron being dispatched for the purpose, and added “so the story that the ladies are telling in recent years, it’s quite true, that they were impounded in these brothels up there in the islands”.41

Though some of the victors responded with kindness, the general air of confusion leaves open a troubling question: whether “comfort women” were ever abused by their supposed liberators. There are one or two stories of allied soldiers having sexual relations with “comfort women” controlled by the Japanese military during wartime. Jack Caplan, a British signalman who became a prisoner on the Thai-Burma railway, recalled how a fellow allied POW became friendly with one of the Japanese guards. The guard arranged for the prisoner to have a brief sexual encounter with one of the “comfort women” who were regularly trucked into the guards’ compound. As a result, the POW caught syphilis and, unable to seek treatment for fear of revealing how he had contracted the disease, committed suicide by throwing himself under a train.42 According to Arthur Hudson, a POW who was held in a camp near Hiroshima at the end of the war, the Japanese military created a brothel for former allied POWs in the period between the Japanese surrender and the arrival of the allied occupation forces. Hudson claims that only one of the POWs visited the brothel, since the rest were too physically weakened, and were afraid of contracting venereal disease.43

Yuki Tanaka, in his research on the “comfort women” issue, points to evidence that some senior members of the US military were entertained in Seoul soon after the surrender by Korean “geisha” who were probably former “comfort women”.44 Katherine Moon suggests that the first generation of women recruited to brothels in the gijichon (camptowns) that grew up around US bases in Korea included former “comfort women”.45 The British and Australian records and testimony that I have seen do not contain any direct evidence of sexual abuse of rescued “comfort women” by their rescuers, but they do present the spectacle of one rescuer actively engaged in setting up military brothels even as he offered protection to escaped “comfort women” in another part of the same town. David Smiley, who had “discharged the debt” of the fifteen Korean women in Ubon, was simultaneously (as he explains in his memoirs) creating a “system of brothels”: “several for the [British] troops and one for the officers christened the ‘Chinese Hotel’”. The brothels were set up with the help of the local police chief, and the [presumably Thai or Chinese] women who worked there were paid “three panels of parachute silk… for each performance”.46

As soon as you begin to explore the oral archive of the Asia-Pacific War, you unearth repeated stories of sexual encounters between allied soldiers and prostitutes. Unlike both Japan and France, which operated extensive systems of military brothels, the British, Australian and US military at this time did not generally create their own brothels. Instead, they had inconsistent and fluctuating policies of venereal disease control, which in fact allowed much scope for soldiers to visit private brothels. As in the Ubon case, though, individual officers sometimes took matters into their own hands.

Similar events took place during the Korean War. One British veteran recalls the sergeant major in his unit operating a small brothel in a building adjoining their base in Incheon. It was, he comments, not officially approved by the authorities, but was “condoned”.47 British officer Harold Pullen, in Japan during the allied occupation, visited a “geisha house” which he says was “run by the Australians”. He gives a very detailed description of being entertained by young women whom he and three companions had “discreetly” selected at the beginning of the evening. After eating and drinking, each went to separate rooms to have a bath and sex with one of the women. In the course of the night Pullen learnt that his companion was fifteen years old.48 Although there is no evidence that the Australian military officially operated brothels in Japan, it may be that this too was the enterprise of some individual Australian officer which was “condoned”. We know far too little about the ways that such brothels, and the mass of other private houses of prostitution frequented by allied troops in Asia (and in Australia and New Zealand), were organised. We know little or nothing about the way that women were recruited to these places, and we hardly ever hear the voices and experiences of the women themselves. Were they recruited by practices like deception or debt bondage? Were any recruited by direct force? How free were they to leave? Without knowing at least some answers to these questions, we cannot advance debate about crucial questions about the wartime violation of women’s rights.

The debate on the “comfort women” issue has become polarised into a bizarrely distorted discourse that traps language in obsessive whirlpools where words circle endlessly around a historical and ethical void. Resurgent revisionism in Japan rides uncomfortably on the back of two fundamentally contradictory claims. One claim runs: “there is no evidence of a system of military brothels; there was no forced recruitment; the stories of the former comport women are lies”. The other says: “all countries operate similar systems in war; the US, France and Britain all had systems of military brothels; what Japan did in the war was just normal”. Meanwhile, the critics of Japan’s wartime military brothel system (and here I include myself) have been too slow to confront their own countries’ histories of military sexual exploitation of women, in part because we are always afraid that any evidence we produce on this issue will be hungrily devoured by the Japanese denialist right and regurgitated across the Internet in distorted forms to bolster their claim that “Japan did nothing wrong”. I feel that anxiety now as I write this article, fully expecting the “comfort women” deniers to seize and exploit sentences that mention “comfort women” receiving money or British soldiers establishing brothels, while blanking out the testimony which (equally reliably) speaks of the kidnapping, forcible transportation, impounding and even possibly killing of “comfort women” by the Japanese military.

The Spectre of Comparison

Seventy years after the end of the Asia Pacific War, we need a new approach that places the history of the Japanese military’s “comfort women” system firmly in an international history of the military sexual abuse of women. This cannot be done by treating history with a bland moral apathy that says “war is war; boys will be boys; everybody does it”.

The historical record shows that war greatly increases the likelihood of all forms of sexual violence against women (and also of sexual violence against men). It transports hordes of young, confused and often frightened young men to alien environments where they lack normal social means of interaction with women. It creates violent and unequal power relations which make it easier to get away with rape and sexual assaults of all kinds. Abolishing war would be a wonderful way of reducing global levels of sexual violence.

But, short of this ideal, there are things that can be learnt from history if people are willing to look at the historical record. History shows that different militaries address the issue of sex in different ways, and that the way military forces are organised and disciplined profoundly affects the amount of harm that they inflict on civilian populations. To condemn the Japanese military’s treatment of the “comfort women” is not to imply that Japan was unique in inflicting various forms of sexual violence on women in wartime, nor is it a personal condemnation of Japanese soldiers, who as individuals, were surely neither more nor less inherently moral than their allied counterparts. But abundant historical evidence (to which this essay adds only a tiny fraction) shows that the wartime Japanese military operated an unusually massive system of brothels to which large numbers of women from Japan, its empire and occupied areas were transported, often over great distances, and where they were held in conditions where many suffered terribly.

The recruitment and treatment of these women seems to have varied greatly. The testimony presented in this essay adds to other evidence showing that some women were paid and received goods like sweets and cigarettes; but also that some women were “bought” from their families or others, some recruited by trickery, some were taken and many were held by force, and some were transported in guarded military trains in the same conditions as prisoners of war. It also shows that at the end of the war all of them were abandoned, and suggests that some of them may even have been killed, by the Japanese military.

|

Zahle, Lebanon. Prostitutes standing in a street outside a brothel. This brothel was reputedly run by the British Army for British troops only. c. 1941, AWM P03498.006 |

Evidence from the war archives also shows that Commonwealth soldiers visited brothels in large numbers, and that some set up brothels for the use of their troops. Beyond the geographical scope of this essay, the use of brothels by Commonwealth troops seems to have been particularly widespread and disturbing in Egypt and the Middle East: a forgotten history which casts a palpable shadow over contemporary global events. Curiously, in the many oral history interviews to which I have listened, the interviewers seem a good deal more willing to ask questions about the sexual behaviour of British and Australian troops than they are to pursue the question of the Japanese military “comfort women”. But in either case some questions are very rarely asked: “who were the women who worked in the brothels? How were they recruited? In what conditions did they work?”

Through the research of scholars like Yuki Tanaka and Katherine Moon, we know a little more about the women who were taken into “camptown” brothels which served (and still serve) the US military in Japan and Korea.49 We know that these camptowns raise enormous and still unresolved problems of sexual violence, exploitation and human trafficking. But before we assume too simple an equivalence between the Japanese military “comfort women” system and the US military “camptown”, we must also remember this: although US military forces were responsible for large scale sexual abuse of women in Japan and Okinawa, and later in Korea and Indochina, in the postwar decades, they did not (for example) transport Japanese, Okinawan or other Asian women en masse and without their consent to their military bases in Vietnam and Cambodia and other places where the US was at war, and then abandon them there when America was defeated. If they had done so, the feeling of anger towards the US in Japan and Okinawa, Korea and elsewhere today would surely be much greater than it is. Through imagining that counterfactual history, we can understand at least some of the anger that persists in Korea and China and elsewhere about the history of the “comfort women”.

One further under-researched case helps us to consider the international dimensions. Fleeting references to issues of wartime and postwar prostitution in China remain in the oral history archive of Imperial War Museum. Some British conscientious objectors, in particular, went to China during the war and worked as ambulance drivers, teachers, etc. They testify to the widespread existence of Chinese brothels frequented by Chinese and their US and other allies in the Nationalist controlled areas of China.50 But there is also testimony that Communist forces, at least during the civil war and in the early phases of the People’s Republic, made strenuous efforts to get rid of military and other prostitution, and to provide training and alternative work to former prostitutes.51 Similar testimony, interestingly, comes from one former member of the Japanese wartime military who was left behind in China, and ended up fighting with the Chinese People’s Volunteers in the Korean War. Interviewed on his return to Japan, he too remarked on the correct behaviour of the Chinese communist troops to civilian women.52 I lack the knowledge to judge how far this testimony can be generalised, and the topic deserves much further research. But the fragmentary evidence suggests an important point: that differences in the treatment of women in war by different armies are not determined by nationality, ethnicity or immutable cultural attributes. They are problems of the ethos and structure of military systems: a thought which should give us hope, for these things can be changed.

Towards Another Future

Seventy years after the end of the Asia Pacific War, we have barely taken the first steps towards overcoming the problems of violence against women in war. This violence remains a living and terrible reality in the Middle East, parts of Africa and elsewhere. Japan and other countries of the Asia Pacific and beyond urgently need to contribute to the search for a better future. But this can only happen when the history of sexual violence inflicted by many militaries is confronted, and its lessons are taken to heart. The Japanese military was of course not unique in inflicting sexual violence during the Asia Pacific War. But its military “comfort women” system was very large and widespread, and caused enormous suffering to large numbers of people. Japan cannot play a significant role in the search for solutions as long as its government refuses to acknowledge the reality and violence of this system, and as long as large numbers of Japanese people are miseducated about this history by their political leaders and by denialist mass media.

The task of confronting Japan’s past would be made easier if people in other countries – Britain, the US, Australia, Korea, China and elsewhere – were more willing to explore their own militaries’ records of sexual violence. The story of the Asian and other women who worked in military and civilian brothels serving US and Commonwealth troops during and after the Asia Pacific War deserves to be much better known. We need to know more about the diverse, shifting and often inconsistent policies used by militaries to regulate sexual relations with civilians, and to understand more about the effects of different policies on levels of sexual violence. For too long, we have “not wanted to know about the girls/women”, turning blind eyes towards the experiences of those affected by the sexual violence of war. The search for a better future requires a new commitment to historical honesty all round.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History in the Division of Pacific and Asian History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. Her most recent books are Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era and To the Diamond Mountains: A Hundred-Year Journey Through China and Korea.

Recommended citation, Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “You Don’t Want to Know About the Girls? The “Comfort Women”, the Japanese Military and Allied Forces in the Asia-Pacific War”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 31, No. 1, August 3, 2015.

Related articles

• Norma Field & Tomomi Yamaguchi, ‘Comfort Woman’ Revisionism Comes to the U.S.: Symposium on The Revisionist Film Screening Event at Central Washington University

• David McNeill & Justin McCurry, Sink the Asahi! The ‘Comfort Women’ Controversy and the Neo-nationalist Attack

• Uemura Takashi and Tomomi Yamaguchi, Labeled “the reporter who fabricated” the comfort woman issue: A Rebuttal

•Yoshimi Yoshiaki with an introduction by Satoko Norimatsu, Reexamining the “Comfort Women” Issue. An Interview with Yoshimi Yoshiaki

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Addressing Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’ Issue From an Academic Standpoint

• Totsuka Etsuro, Proposals for Japan and the ROK to Resolve the “Comfort Women” Issue: Creating trust and peace in light of international law

• Okano Yayo, Toward Resolution of the Comfort Women Issue—The 1000th Wednesday Protest in Seoul and Japanese Intransigence

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Out With Human Rights, In With Government-Authored History: The Comfort Women and the Hashimoto Prescription for a ‘New Japan’

• Wada Haruki, The Comfort Women, the Asian Women’s Fund and the Digital Museum

Notes

1 Angus McDougall (Private, 2/20 Battalion and prisoner of the Japanese, 1941-1945), oral history interview, 18 July 1984, Australian War Memorial (hereafter AWM), S04083, reel 3.

2 McDougall 1984.

3 Frederick Alexander Arblaster (Australian NCO served as Japanese translator and interpreter in Australia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Japan, 1943-1947), oral history interview, 16 October 2003, Imperial War Museum (hereafter IWM), 25574, reel 6.

4 Norah Newbury Inge (British civilian missionary with Japanese civilian internees in Singapore and India, 1941-1946), oral history interview, 5 November 1984, IWM, 8636, reel 3; the story of Deoli, almost unknown in Britain, is an important and disturbing one. As Inge recounts, some twenty Japanese civilian detainees were killed by guards during a riot following Japan’s surrender. Inge is highly critical of the camp commander for his handling of the crisis and for its disastrous outcome. It is unclear whether any of the former comfort women were involved in these events.

5 Hank Nelson, “The New Guinea Comfort Women, Japan and the Australian Connection: out of the Shadows”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 22 May 2007.

6 Yoshiaki Yoshimi (trans. Susan O’Brien), Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II, New York, Columbia University Press, 2000; Yoshiaki Yoshimi, “Government must admit ‘comfort women’ system was sexual slavery”, Asahi Shimbun / Asia and Japan Watch, 20 September 2013.

7 Taiwan Gun Shireikan, “Nampō Haken Tokōsha ni kansuru ken”, in 12 March 1942, in Josei no tame no Ajia Heiwa Kokumin Kikin ed., “Jūgun Ianfu” Kankei Shiryō Shūsei, vol. 2, Tokyo, Ryūsei Shosha, pp. 203-204

8 For example, ruling in the case of the former Busan (Korea) comfort women and forced labourers, Shimonoseki Branch of the Yamaguchi District Court, 27 April 1998 http://www.gwu.edu/~memory/data/judicial/comfortwomen_japan/pusan.html accessed 15 November 2014 (note that this ruling was overturned, but on issues related to right of the plaintiffs to sue the Japanese government, not on the facts of the case).

9 Harry Roque, “The Ongoing Search for Justice for Victims of the Japanese War Crimes in Mapanique, Philippines”, Oxford Human Rights Hub, 31 August 2013; Decision of the Republic of the Philippines Supreme Court, 28 April 2010.

10 Bart van Poelgeest, Gedwongen Prostitutie van Nederlandse Vrouwen in Voormalig Nederlands-Indië, report to the Second Chamber of the States General, 24 October 1994, p. 16, accessed 10 July 2014.

11 Yoshimi, Comfort Women; Yuki Tanaka, Japan’s Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation, London, Routledge, 2002; C. Sarah Soh, The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008; Nelson, “The New Guinea Comfort Women”.

12 Mary Louise Roberts, What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2013, p. 11.

13 Inge 1984

14 Leslie Theodore Lyall (British civilian missionary in China, 1929-1944), oral history interview 1986, IWM 9242, reel 3.

15 Eleanor May Clark (Burmese civilian during Japanese occupation of Burma, 1942-1945), oral history interview, 16 May 1995, IWM, 16671, reel 3.

16 AWM photographic collection, item 120083 (photographer K. B. Davis).

17 Francis McGuire (British NCO served with Malaya Command Signals in Singapore, Malaya, 1942; POW in Changi POW Camp, Singapore, Malaya, on Burma-Thailand Railway and Ube POW Camp, Japan, 1942-1945), oral history interview, 1 November 1982, IWM, 6374, reel 2.

18 Geoffrey Pharaoh Adams (British officer with Royal Army Service Corps in Singapore, Malaya, 1941-1942; POW in Changi and Sime Road POW Camps, on the Burma-Thailand Railway, in Fukuoka 17 POW Camp, Omuta, Japan and Hoten POW Camp, Manchuria, 1942-1945), oral history interview 1 March 1982, IWM, 6042, reel 6.

19 John Allan Legh Barratt, His Majesty’s Service, 1939-1945, Manningtree, Status, 1983, p. 22.

20 Thomas Robert John Coles (British airman, served with RAF off Singapore and in Java,1942; POW in Java, the Moluccas and the Celebes, Dutch East Indies, 1942-1945), oral history interview, 21 May 1996, IWM, 16660, reel 2.

21 For example, the British based Abolition Project defines a “slave” as “a human being classed as property and who is forced to work for nothing”.

22 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery, Adopted by a Conference of Plenipotentiaries convened by Economic and Social Council resolution 608(XXI) of 30 April 1956, and done at Geneva on 7 September 1956; Entry into force: 30 April 1957.

23 This testimony is summarised in two documents: Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces, research report no. 120, produced by the Allied Interpreter and Translator Section, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, in Josei no tame no Ajia Heiwa Kokumin Kikin ed., “Jūgun Ianfu” Kankei Shiryō Shūsei, vol. 5, Tokyo, Ryūsei Shosha, pp. 151-153; and United States Office of War Information, Psychological Warfare Team Attached to US Army Forces India Burma Theatre, “Japanese Prisoner of War Interrogation Report No. 49”, APO 689, in “Jūgun Ianfu” Kankei Shiryō Shūsei, vol. 5, p. 203-209.

24 A widely circulated paper by former banker and passionate historical nationalist Ogata Yoshiaki, for example, cites “Japanese Prisoner of War Interrogation Report No. 49” as proving that “ the monthly take of the [comfort] women was approximately 1,500 yen, and they kept between 40 to 50 percent of this. In other words, their ‘take home’ income was an extremely high wage of 750 yen per month”; see Ogata Yoshiaki, “The Truth about the Question of ‘Comfort Women’”, p. 2. This statement, much quoted as demonstrating that “comfort women” were merely “well-paid prostitutes”, reflects a very inattentive reading of the Kitamura interrogation material. Interrogation Report No. 49 does include a statement that “in an average month a girl would gross about fifteen hundred yen. She turned over seven hundred and fifty to the ‘master’” (p. 205, emphasis added). But cross-referencing this with the more detailed Amenities in the Japanese Forces, it soon becomes clear that this is a mistake. The sentence should read (as it does in the latter document): “the maximum gross takings of a girl were around 1500 yen per month, and the minimum around 300 yen per month” (p. 152, emphasis added). Because Amenities in the Japanese Forces provides details of the numbers of soldiers who visited the brothel and the amount they paid, it is easy to calculate likely average earnings. On the basis of this information, it is clear it would have been extraordinarily difficult for any one person to make gross earnings of 1500 yen in a month, and that the average was actually close to the 300 yen “minimum”.

25 Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces, p. 151.

26 “Japanese Prisoner of War Interrogation Report No. 49”, p. 203.

27 Calculated from Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces, p.152.

28 Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces, p.152.

29 Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces, p.152.

30 South-East Asia Translation and Interrogation Center, Psychological Warfare Bulletin no. 182, 1945, in Josei no tame no Ajia Heiwa Kokumin Kikin ed., “Jūgun Ianfu” Kankei Shiryō Shūsei, vol. 5, Tokyo, Ryūsei Shosha, (http://www.awf.or.jp/pdf/0051_5.pdf), p. 38.

31 William “Tug” Wilson (British NCO, served with 16th Assault Regt, Royal Artillery in India and Burma, 1941-1945), oral history interview, 14 February 2000, IWM, 20125, reel 4.

32 Ian Britain ed., The Donald Friend Diaries: Chronicles and Confessions of an Australian Artist, Melbourne, Text Publishing, 2010, p. 146.

33 AWM art collection, item ART23229..

34 Arthur Francis Freer (British trooper and NCO, served with 3rd Carabiniers in India and Burma, 1943-1945), oral history interview, 24 September 1999, IWM, 19822, reel 6.

35 Anon (British officer served with 7th Bn, 10th Baluch Regt in India and Burma, 1941-1946), oral history interview, 1999, Imperial War Museum, 19807, reel 11.

36 David Smiley, Irregular Regular, Wilby, Michael Russell Publishing Ltd., 1994, p. 167.

37 South East Asia Command Film Unit, “Japanese Prisoners of War at Penwegon, 30 July 1945, (cameraman: J. Abbott), IWM, JFU 284; and South East Asia Command Film Unit, “Japanese Prisoners of War at Penwegon, 30 July 1945, (cameraman: J. A. Hewit), IWM, JFU 285.

38 George Mailer-Howat, “Extract from George Mailer-Howat’s Memoirs (1942-45)”, n.d., unpublished, IWM, Documents.22637, p. 15.

39 See Joe Royle (British NCO, served as cameraman with No 9 Army Film and Photographic Unit in Far East, 1945-1947), oral history interview, 17 July 1999, IWM, 19654, reel 3.

40 “Evacuation Japanese civilians, Manila”, 13 October 1945, (cameraman: Roy Driver), AWM F01352.

41 Francis Stanley Terry (cook; minesweeper HMAS Mercedes and corvette HMAS Warrnambool; Australian western approaches and northern and eastern waters; 1941-1946), oral history interview, 27 July 1995, AWM, S01794.

42 Jack Israel Caplan (British signalman served with Royal Corps of Signals in Singapore, Malaya, 1942; POW in Changi POW Camp, Singapore, Malaya, on Burma-Thailand Railway and Saigon POW Camp, French Indo-China, 1942-1945), oral history interview 11 May 1981, IWM, 4884, reel 5.

43 Arthur Hudson (British air photographer, served as armourer with 605 Sqdn, RAF in GB and Dutch East Indies, 1939-1942; POW in Java and Sumatra, Dutch East Indies and in Japan, 1942-1945), oral history interview, 16 March 1994, IWM, 13923, reel 4.

44 Yuki Tanaka, Japan’s Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation, London, Routledge, 2002, p. 86.

45 Katherine Moon, Sex among Allies: Military Prositution in US-Korea Relations, New York, Columbia University Press, 1997.

46 Smiley, Irregular Regular, pp. 160-161.

47 William John Hiscox (British driver served with 170th Independent Mortar Battery, Royal Artillery and 120th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery in Korea, 1951-1952), oral history interview, 29 April 2006, IWM, 28764, reel 6.

48 Harold Neil Desmond Pullen, (British civilian officer, served with 1 Bn Royal Norfolk Regt in Korea, 1951-1952), oral history interview, 7 May 1998, IWM, 18018, reel 4.

49 Tanaka, Japan’s Comfort Women; Moon, Sex Among Allies.

50 Gordon Douglas Turner (British civilian pacifist in GB, 1938-1944; served with Friends Ambulance Unit in China, 1944-1947), oral history interview, 24 June 1984, IWM, 9338, reel 11.

51 Anthony Curwen, (British civilian conscientious objector served with Friends Ambulance Unit in GB, Syria and China, 1943-1951; aid worker in China, 1951-1954), oral history interview, 18 May 1987, IWM, 9810, reel 7.

52 Hyūga Nichinichi Shinbun, 4 August 1954