Reflecting on the 70th anniversary of the end of Japan’s War, it is worth noting that teaching the history of World War II to Japanese children has always been difficult at best. As a subject fraught with contentions over textbook content and conflict between teachers and state bureaucracy, teaching war history has long been “a dreaded subject” for many school teachers. Japanese history education has been criticized for not going far and deeply enough to describe perpetrator history – especially the injury and death inflicted on tens of millions of Asian victims. At the same time, it has been admonished for the opposite: that it goes too far in promoting Japan’s negative self-identity. This contest to shape hearts and minds of future citizens has long burdened Japan’s history education in schools, and has yielded mixed results.

Flawed as the school instruction of war history is in many respects, however, what is easily overlooked in the focus on the shortcomings of formal history education is the significant impact of informal education about the Asia-Pacific War. What can deeply influence the hearts and minds of the next generation – perhaps more than textbooks – is the power of popular war stories accessible to children in the commercial media and libraries. This “pop” war history is readily available in children’s everyday life, mostly unmediated by teachers and unfiltered by state authorities.

War stories for children in Japan’s popular culture have been influential carriers of war memory for many decades. Famous stories created by celebrated manga and anime artists like Barefoot Gen, Grave of the Fireflies, and To All Corners of the World have successfully exposed young readers to the destructive aspects of the Asia-Pacific War and influenced them to feel the horror of death. Others like Mother’s Trees, Glass Rabbit, and Poor Elephants have been equally successful in shaping young children’s antipathy toward lethal violence, exposing them to the sheer meaninglessness and horror of mass death. The cumulative effect of these cultural materials – produced, reproduced, and revised over many years in multiple editions and in diverse media – is to nurture negative emotions about the Asia-Pacific War and war in general that have become powerful motivators of moral conduct. The discussion that follows draws from my book, The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Japan, where the topic of children’s education about the war appears in the larger context of Japan’s collective memory of colonialism and war, the national fall, and its pathways toward moral recovery.

Collections of Study Manga: History from Below

In a country where the popular cultural media are ubiquitous, it is not surprising that material on Japanese history is abundant in the commercial media. In Japan 40% of all books and magazines are manga (comic art) publications. It stands to reason that manga has been a popular vehicle for supplemental instruction and education. Indeed, this genre called “study manga,” or “education manga” (gakushū manga), is found readily in school libraries, local public libraries and bookstores. As informal tools of cultural learning they are on a par with television and animation films in how they bring cognitive comprehension to children, influencing their perceptions as memory carriers of the next generation. They are entirely distinct from young boys’ entertainment comics, not discussed in this essay, that valorize heroic fighters, fictive or otherwise, in throwaway paper format. Of the public media that transmit and translate war memory – from newspapers, magazines, books, and novels to television documentaries and films – study manga merit special attention as a vehicle that exclusively targets children at a formative age, when their ethical judgment and moral dispositions are formed.1

The moral evaluation of war and peace in pop history study manga comes into clear focus when we closely examine their content for plot, characters, visual clues, and dramatic style. They are, however, not standardized or uniform within the genre. Study manga can be classified in several categories: “academic” history manga series by professional scholars; “popular” history manga series by superstar artists in the manga industry; “Cliff-Notes” history manga designed for students preparing for entrance exams; “digest” history manga for quick reference; “biographical” manga of eminent and popular figures; “novelized” history manga for entertainment, and more. I focus here on two types of study history series – the “academic” and the “popular” – that have proven their staying power with major, powerhouse publishers, some becoming classics, reprinted many times over in the last decades. They include six well-known series: three “academic” collections supervised by professional historians, and published by the mainstream publishers Gakushū Kenkyūsha (known by the shorthand Gakken), Shūeisha, and Shōgakkan; and three “popular” collections offered by the studios of three phenomenally successful star artists of the postwar manga industry, Fujiko F. Fujio, Mizuki Shigeru, and Ishinomori Shōtarō.2

Successful study manga make grim history palatable, even engrossing, with dynamic plots, colorful characters, and humorous asides. The stories, in contrast to the typically bland textbooks, are often page turners that sustain readers’ curiosity and entice them to imagine and identify with distant, unfamiliar times and places. They also help the reader’s cognitive grasp of moral distinctions by showing the ethical qualities of key characters with graphic visual cues like facial expression, body language, and other signals. For example, if characters are drawn with a menacing grin, harried body language and in dark silhouettes, the reader readily understands that the plan they are hatching must be of dubious moral quality. Equally significant and captivating in study manga is the view of history from below, allowing readers to see events through the eyes of “ordinary families” that are interspersed in the narrative to drive the plot, to comment on the events, and to express feelings about the impact of the events on their everyday life. This sympathy with the “little people” gives these stories an unmistakable populist tilt, and an interpretive framework critical of higher authority. The chutzpah and irreverence typical of Japanese comics are perfectly suited to expressing misgivings about authorities like the government, military, and police, and indeed, caricatures are delightful ways to get back at the overbearing bullies who intimidated, oppressed, policed, betrayed and devalued the masses in wartime society.

Academic history manga

Educational comics about national history, a familiar genre of children’s literature in many countries, have been popular tools of learning in Japan since the 1970s.3 In Japan, they typically come in multi-volume collections offered by well-known, major publishers in hard-covers, and purchased by schools and local libraries as well as parents and grandparents for young children to read at home. For example, the well-known Gakken series on Japanese history is an 18-volume set in its current edition, now in its 60th printing since 1982; Shōgakkan’s current series spans 23 volumes, and is now in its 49th printing since 1983; Shūeisha’s current series is a 20-volume set in its ninth printing since 1998. These educational manga series, supervised by academic historians, are targeted to children of school age, mostly in elementary and middle schools.4

For the most part, the academic manga offer colorful portrayals of 2000 years of Japanese history from early settlement through the contemporary era in chronological order. The portrayal of the Asia-Pacific War usually takes up one volume, averaging about 150 pages in length. As a portrayal of a discredited and disastrous war, there are no gallant national heroes or enchanting political leaders that brighten up the pages and dramatically drive the plot. Instead, the stories unfold with accounts of divisive politics and deteriorating economic life that are rife with social conflict, unstable government, ambitious military, terrorist violence, rogue actions, and rampant poverty. These accounts are interspersed with descriptions of bloody violence, oppression, and massacres, which, in turn, lead ultimately to crushing defeats, mass deaths, and the devastating national fall.

|

The War in Asia and the Pacific (Shōgakkan’s manga history of Japan) |

The descent into war is rendered into a sobering morality tale of what not to do again. The pacifist moral frame is consistent: war-friendly characters and actions are portrayed negatively, and peace-friendly characters and actions are portrayed favorably. The anti-war messages of the “little people” are especially striking, from a grim conscript’s cry (“I curse this war,”)5 to a stunned mother’s lament (“War – I hate war…”)6 and a grandmother’s desperation about her grandson’s departure to war (“everyone cursed the war, and prayed their children would come home safe”).7 Even a family dog bemoans, “I hate war!”8 Front and back matters of the books also convey moral evaluations, such as a note to the family that pleads, “please make sure to let the readers pay attention to Japanese acts of perpetration in China.”9 As war memory is translated into cultural memory in educational manga, compassion for suffering is now directed to anti-war pacifism – the desired moral quality transmitted to the young readers – even though in wartime it was condemned as unpatriotic.

No heroes make their mark in these academic study manga, but a few villains make unceremonious appearances. None of these villains are American, Chinese, Russian, or anyone else in the enemy camp; they are all Japanese. The designated “bad” characters are Japanese men who advocated, instigated, promoted, and then bungled the war. Such “war mongers” are usually officers of the Japanese Army, especially those in the Kwantung garrison in Manchuria and the high military and state leadership who backed and covered for the rogue Army. These loaded characterizations produce a vernacular understanding of Japan’s colonial war on the continent in young readers who develop an early moral awareness of “something gone terribly wrong in Japanese history.”

|

The Asia-Pacific War (Shūeisha’s manga history of Japan) |

To be sure, what went terribly wrong is not only the colonial exploitation and military catastrophe both across Asia and in Japanese cities, but also the massive death toll of over 20 million people in Asia, many of whom were noncombatants, and 3.1 million Japanese including nearly one million noncombatants. To this end, two of the three study manga series – Shūeisha and Shōgakkan – offer explicit perpetrator narratives illustrating Japan’s subjugation of civilians in East and Southeast Asia during the years of war and colonization. One volume describes Japanese atrocities carried out in the Nanjing “Incident,” the slaughter of civilians in Chinese villages, recruiting forced laborers in occupied territories, and the biological warfare Unit 731.10 Another volume gives graphic accounts of civilians slaughtered in Nanjing, as well as villagers slain in rural China in the campaign to kill, plunder, and burn (the Three-Alls campaign).11 The ferocious Japanese invasion of East and Southeast Asia is also described, including full-page accounts of the massacre of civilians in Singapore and elsewhere.12 The brutal treatment of forced laborers – locally drafted or captured POWs – by Japanese soldiers and administrators also takes up full pages in both volumes.13

As a rendering of a multidimensional war, the portrayal of the violence and dehumanization inflicted by Japanese soldiers on Asian victims is also extended to those inflicted on Japanese soldiers by the Japanese military. Their anguish typically comes from the battlefront, from fighting unwinnable and lethal battles planned by incompetent military strategists in places like Imphal (“Damn! I curse the top brass who planned this.”),14 to dying of disease and starvation in Guadalcanal and elsewhere as supplies ran out (“We can’t go on fighting with malaria and malnutrition …”),15 and killing themselves en masse rather than surrender to the enemy (“I can’t move anymore. Kill me.”)16 The suffering of Japanese civilians is described with equal candor – deaths by aerial bombings, atomic bombs and the battle of Okinawa – and takes up an amount of space similar to the illustration of Asian victims at Japanese hands. Indeed, the number of pages devoted to recounting the hardship of Japanese civilian victims devastated by bombardments on the home front and driven to mass deaths in Okinawa is roughly comparable in length to the space allotted to Japan’s acts of imperial oppression and perpetration overseas.

In all, these texts offer a barebones synopsis, yet nevertheless visually riveting account, of a war that caused, in their estimates, a total death toll on the order of 20 to 23 million. The underlying causes of the atrocities, however, are not explained in detail to the young readers. Other than the outlines of events, there is no close reasoning of the causal chain of events. They are tuned to cognitive rather than conceptual comprehension, and emotional rather than rational understanding. These, abridged history stories for young children are sanitized cultural products, but they can nevertheless play a notable role in cultivating moral and even political dispositions. What is inculcated here is a simple pacifist sentiment that precludes any possibility of a just war: war is bad and unjust, because war kills and people suffer; it is an evil that hurts people like you, your family and friends; the government that wages war is bad, and can’t be trusted to help and protect you.

|

The Road to War (Gakken’s manga history of Japan) |

Compared to the foregoing two series, Gakken’s national war is visually brighter, shown as an event carried out by child-like, inoffensive protagonists who are muddling through an international crisis. It is largely a “war story lite” about state and military leadership decisions, without showing any bloodshed or dead bodies, still less atrocities. The war was instigated by the belligerent Japanese Army which amassed power through the prolonged crisis, and turned Japan into an oppressive military state. They waged a bad war, and created a bad society, but as the plot moves forward and people’s lives deteriorate, not much suffering of Japanese or Asian victims is shown. When no suffering is shown, no one is held accountable for it; when no one is held accountable for suffering, it is possible to take a benign, no-guilt approach to war and colonial oppression. This untroubled approach is different from the foregoing two series, but the moral sentiment that “everyone cursed the war”17 is nevertheless built into the storyline, and comes across clearly to the readers. The much simplified, abridged history strives to be unthreatening to children, yet war is anything but glamorous. When historical memory is rendered into long-term cultural memory in this type of no-guilt educational manga, the moral sentiment is still anything but pro-war or pro-military.

Popular history manga

Fujiko F. Fujio, Ishinomori Shōtarō, and Mizuki Shigeru are superstar manga artists who are celebrated for their classics from samurai adventures and space ventures to family stories and ghost stories, and are well-known beyond the manga and animation film industries. Over the years, their imaginary characters have become household names, like the delightful robocat Doraemon who is ubiquitous in popular culture from television shows and commercials, to paraphernalia like guitars, stationery, and refrigerator magnets, and now an international superstar. Such popular characters that enchanted and entertained successive generations growing up in postwar Japan have also been put to good use for producing “popular” history comics, rendering complex history into abridged stories for successive young generations. The result is a particular style of documentary history comic stories told by fictional narrators, unfolding with a kind of Verfremdungseffekt (alienation effect) of a Brechtian play that tells stories within stories to create a disengaged critical perspective. With commentary from lovable iconic characters, tragic dark history can be rendered into accessible morality tales rich with emotion, irony, and caricature. These popular stories, produced by the manga artists or franchised by their production companies, are multi-volume sets of history manga published in paperback which are less scholarly than the academic series and less constrained by curricular guidelines. These popular study manga take more artistic liberties than academic manga. They are imaginative in rendering war history into entertaining cultural products that are appealing for young generations. To be sure, the artistry comes at a cost to comprehensive or rigorous assessment of history. The complex reality of defeat culture in which heroes, victims, and perpetrators are often the same people is left largely untouched. But readers nevertheless take away a cognitive understanding that contemporary Japanese history is a stained legacy, and that being Japanese means they are burdened with that stain.

Fujiko F. Fujio Studio’s Doraemon series

As a winner of many prestigious awards and a phenomenal merchandizing success, Doraemon is perhaps the most fitting manga icon to entice elementary school children to take an interest in learning dark history. The section on World War II in the Nichinōken series takes up only 18 out of 220 pages, but takes readers from the depression and the Manchurian Incident through the escalation of war and oppression in society, to the final catastrophic defeat. As the section sketches the main events, young readers are given succinct commentaries about them by the endearing robocat Doraemon and his dim-witted friend Nobita. It is mostly Nobita who conveys the moral evaluation of the war and wartime society through his visceral cries: “ugh, another war? I can’t take another one.”18 “That’s a terrible law [to arrest people who opposed the government].”19 “I will never go to war!”20 “They’re even sending students to war.”21 “Someone, stop [the atomic bomb]!”22 These gut pacifist sentiments are Nobita’s response to the violence and authoritarian oppression introduced in the text. Even though the number of pages devoted to the war is slim, the morality tale to be learned here comes across clearly: the government, military, and business go to war to profit from it. The little people like us are dragged into war and are hurt by it. We don’t trust leaders in power who hurt the little people.

To be sure, the ethics of care for the suffering of little people being taught here applies only within the limits of Japan’s national boundary. Taking the blame for the horrors of war and mounting casualties are not the enemy forces in China or the U.S., but Japanese war mongers who instigated and promoted the war. Not even the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are blamed on the Americans but on the Japanese leadership that missed chances to capitulate earlier, which might have forestalled those tragedies.23 All told, this domestic perspective on the war depicts the Japanese as both perpetrators and victims.

Mizuki Shigeru’s Shōwa History Series

Mizuki’s message about the war is direct and consistent: Fighting in the military to die for the country is utterly absurd. The powerful message that there is no heroism in fighting and dying in an unwinnable war is grounded directly in Mizuki’s wartime experiences – near-death experiences from combat, bombardment, starvation, malaria and amputation – which are all depicted in the series. This compelling message flies in the face of the patriotic mantra of “honorable death” ingrained in his generation of soldiers. Born in 1922 and conscripted at age 20, Mizuki was sent to Rabaul in New Britain, Papua New Guinea, which was a central base of Japanese military and naval operations in the South Pacific at the time. He barely survived combat and repeated bombardment that overwhelmed the ill-equipped and scantily supplied Japanese forces. He survived, thanks to the help of friendly local tribes, and was repatriated after the war. He started writing his war stories in the 1970s after garnering success with Kitarō in the 1960s, and has since remained an anti-war voice, driven by his loyalty to his buddies who died needlessly, and his indignation toward the military and state leaders who abandoned the soldiers without proper supplies, strategic planning, or compassion – causing preventable disasters and unnecessary loss of lives.24 Both Mizuki and his brother Sōhei survived, but not without sustaining life-changing traumas like many others of their generation: Mizuki became an amputee, and his brother became a Class B war criminal for killing a POW, and was indicted and incarcerated in Sugamo prison.

|

|

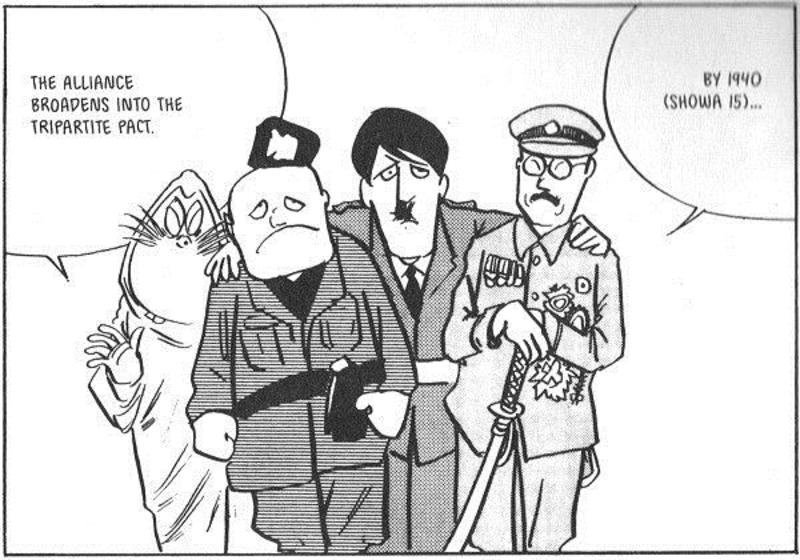

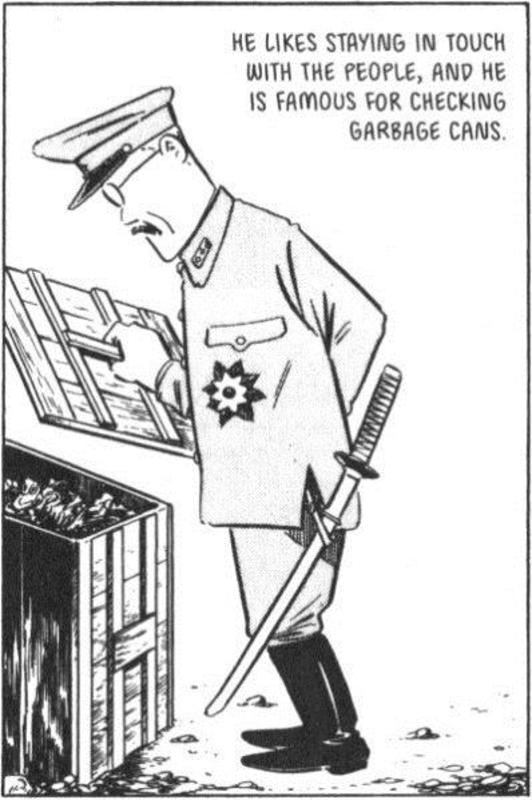

| The Tripartite Pact (Mizuki Shigeru’s manga history of Shōwa Japan) | Prime Minister Tojo inspecting the garbage (Mizuki Shigeru’s manga history of Shōwa Japan) |

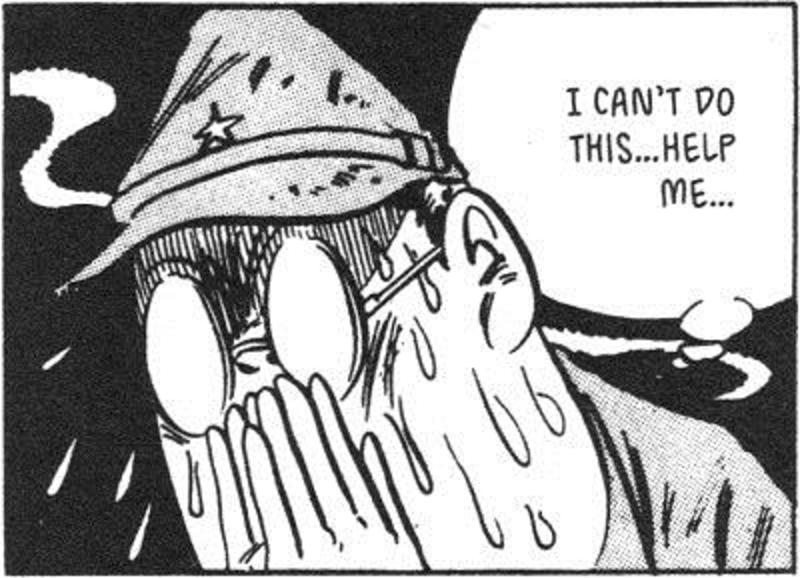

Mizuki’s war history, focused on the lowest rung of military life, is an especially gripping tale that young readers can probably empathize with. The young men in the stories who went to war and died for the country, however, are not heroic personalities that children could desire to emulate. They are unfortunate scrawny characters, beaten and broken, who succumbed to defeat. To be sure, there are extensive battle scenes, and gallant military encounters especially in the first six months of the Pacific War – like Pearl Harbor – reminiscent of boys’ war stories popularized in major comic weeklies in the 1960s.25 But as losses mount and war prospects turn grim, the battles become more chilling than thrilling and the soldiers become more pitiful than brave. For hundreds of pages, readers wading through graphic illustrations of men falling and dying – in Leyte, Guadalcanal, Imphal and elsewhere – can recognize the protracted despair. There is no exhilarating valor.26

|

Soldier Mizuki in mortal fear on the battlefront in Papua New Guinea (Mizuki Shigeru’s manga history of Shōwa Japan) |

Mizuki’s accounts are largely victim narratives. The stories of wrongs inflicted on Japanese soldiers — whose survival rate was atrocious — overshadow those inflicted on Asian people whose lands they invaded.27 This narrow focus on one’s own suffering does not derive from the intent to whitewash or divert attention from perpetrator history, though personal narratives focused on local experience can depict a narrow range of events that often exclude distant suffering. These stories are powerful indictments of the Japanese state and the military that dragged people through an unnecessary war, killed them needlessly, and betrayed their trust until the bitter end. The anguished stories barely conceal anger toward the deception of the unjust military establishment. War memory here is framed by the “pent-up anger toward war” that gnawed at the survivors like Mizuki for many decades.28 In the final volume, Mizuki himself takes over as the narrator to offer his reflections and reminiscences. Here, his indictment of the Japanese state as the perpetrator is no longer disguised. The anti-state, anti-military message to young readers is unmistakable:

“…I really hated militarism. People deluded themselves into believing that anything daring and brave would bring luck and fortune. They parroted all along: ‘Loyalty to the Emperor. Patriotism to the State.’ …We were not supposed to think about ‘ourselves’ but be happy to die as ‘good citizens’ when the draft letter arrived. If truth be told, people who lived through the early Shōwa [era] were bullied by the State …The ‘military’ was like a cancer that had to be surgically removed [by defeat].”29

|

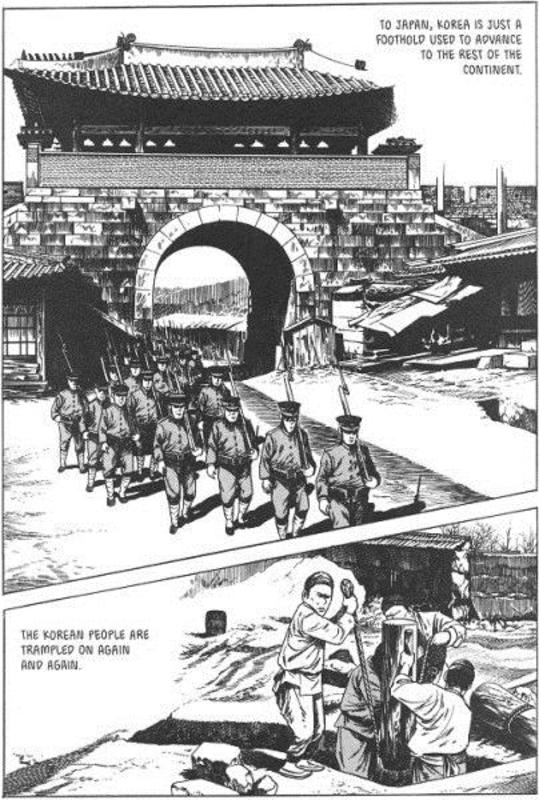

Japan’s occupation of Korea (Mizuki Shigeru’s manga history of Shōwa Japan) |

Ishinomori Shōtarō’s Manga History of Japan Series:

In Ishinomori’s Manga History of Japan, the Asia-Pacific War period takes up nearly 300 pages, and is presented as a descent into a ruinous war through many ill-fated political maneuvers and erroneous decisions. The dominant story is that of the fierce political struggle among a cadre of elite men in power. In that struggle, the bellicose Army leadership ultimately rises to power, and recklessly thrusts the nation into a world war that ends in the devastating downfall. The bickering rivalries, mistrust, miscalculations, and miscoordination at the heart of the story are recounted in detail: the leaders fail to heed warnings, miss opportunities to negotiate, lose strategic momentum, misplace their confidence in wishful thinking, and make incompetent decisions. As the military amasses more power over time through emergency legislation and totalitarian repression, the nation becomes a police state. All told, this is a disheartening history of a nation led by misguided villains without any wise heroes who stood firm enough to foil them and save the nation and Asia from disaster.

Ishinomori’s history, unlike the foregoing examples, does not rely on familiar manga characters for narration but develops the plot solely through authorial narratives and graphic depictions of dynamic events and encounters. Taking a populist approach, a regular cast of seven or eight people appears throughout as ordinary citizens voicing their thoughts and feelings about the unfolding events. Their commentaries are presented as casual conversations in a mom-and-pop diner, where the proprietor family and regular patrons shoot the breeze over meals and drinks. They are imaginary witnesses and bystanders of wartime Japan: independent-minded people who own small establishments and regular customers who drop in from all walks of life: newspaper journalists feeling the squeeze of state censorship, youths at schools or in show business being called up to military service, foreign ministry workers confessing to being clueless about the ongoing diplomatic whirlwind, blue-collar workers being laid off from struggling factories, and others. As the war escalates, they feel by turns apprehensive and ambivalent, surprised and cheered, ignorant and manipulated, fearful and confused, resentful and weary, and ultimately, desperate and indignant that the war is dragging the country into an abyss with no end in sight.

The Japanese are clearly shown as the aggressors, and to a lesser extent, as pitiful victims. The reasons why this war escalated to such levels of brutality or why the military callously abandoned Japanese civilians in Manchuria, Saipan, and Okinawa – driving them to desperate mass suicides – are never fully explained, however.30 While young readers are offered insights that this war should have been and could have been prevented, they are given no moral or conceptual means to reflect on practical alternative possibilities that could have been pursued.

|

The Sino-Japan War-The Pacific War (Ishinomori Shōtarō’s manga history of Japan) |

“Something Dreadful Happened in the Past”

Successful pop history projects of manga celebrities like these exemplify the power of cultural memory forged outside the reach of state educational institutions. Phenomenally effective in reaching youth – though overlooked by scholarship preoccupied with official textbooks – manga rode the wave of a generational turnover of Japanese youth, for whom it continues to be, with television and the internet, a compelling, indispensable mode of communication and resource for information. Compared with textbooks, communicating history through manga has been a generationally distinct, and decidedly freer, mode of transmitting memory, embraced first by the baby boomers who welcomed the new expressive voice unencumbered by traditional literature, plays and poetry. Those readers were also happy to turn up their noses at “serious” moralizing work by the wartime generation that controlled the public sphere. Having sensed that those adults had themselves wrought “something dreadful that happened in the past,” the younger generation had good reason to distrust the traditional carriers of memory and celebrate an alternative sphere of communication of their very own. Manga stories, then, became their stories, allowed them to indulge in subverting the authoritarian gaze while also bonding with their peers. It is therefore not surprising that mistrust of state authority is a salient element of pop history, even when criticism is indirect. There is neither glamour nor valor in the way most mainstream study manga history depicts those responsible for the war and their policies. In this sense, young readers of these volumes are more likely to come away disheartened and distressed than entertained by the illustration of the legacy that they have inherited as Japanese nationals.

Japanese children are raised in an environment encoded with generational memory that often encourages them to develop negative moral sentiments about the war. The “encouragement” comes in subtle and unsubtle ways, as young children develop gut instincts that “something dreadful happened in the past,” even if they don’t fully understand what or why. Even when they encounter emotional accounts of terror that seem unfathomable, many can still understand that, unlike the fictive wars in video games and television shows, this one really engulfed the lives of their grandparents when they were small children like themselves. It was so bad that children like themselves lost their families, friends, homes, then couldn’t escape and died. From such “shock and awe” war stories that elicit a visceral response – in animation films, textbook photos, peace education, school instruction, popular history, and more – they may learn to empathize and identify with those war orphans, malnourished children, bombed children, injured children, and abandoned children who lost everything that sustained them.

Over time, this kind of emotional socialization that taps into instincts for self-preservation turns into “feeling rules,” with which children learn to internalize how they are supposed to feel about war in a pacifist country.31 Clearly, this choice of strategy is not geared toward raising nascent critical thinkers who would assume responsibility for the past atrocious deeds of their forefathers as in a culture of contrition like Germany, but is focused instead on not raising the type of Japanese people who could perpetrate another abhorrent war in the future. These are important influences that have long played a role in nurturing Japan’s grassroots pacifism, which have been intensified in this summer’s protests against the Abe government’s push for remilitarization.

The Broader Picture

Turning our attention to study manga published in the last two years, a few trends are worth noting. Some have trimmed down the number of pages describing the Asia-Pacific War, while others have also curtailed the moral evaluation of the war. For example, the NEW History of Japan (NEW nihon no rekishi) reduces the description of the war by half, to 54 from 102 pages, focusing now on stories of select historical figures.32 The moral evaluation of the Asia-Pacific War is truncated accordingly, now articulated through the tormented figure of the Shōwa Emperor who receives a series of troubling reports of international and domestic problems from his advisors and ministers that serve as the book’s narratives of Japanese history. The latest Doraemon series History of Japan has now revised the didactic format of the book to one that focuses on helping readers prepare for middle school entrance exams. Nobita’s humorous asides uttering his fear of and distaste for war are gone in the 36 pages of this volume.33 As the wartime generation who created the original study manga series passes on and postwar scholars now gradually take over the series editorships, it is possible that the negative moral sentiments expressed in study manga will be less salient. It may be part of a trend to promote a vision of history that sees Japan’s road to hell as having been paved with good intentions.

It would be a mistake, however, to see this change, if it continues, as a trend to represent the Asia-Pacific War as a “good war.” Here, the war remains a ‘bad war,” and the underlying message that “something dreadful happened in the past” remains intact; the emotional accounts of terror, and the concomitant moral indignation are, however, considerably diminished. In contrast to the heroic war manga that Kobayashi Yoshinori wrote for adult readers 17 years ago, these recent volumes still represent the Asia-Pacific War as a failed war of a failed state, not a glamorous heroic war. Even when the historical figures are romanticized and mythologized in those volumes, they are not depicted as avid war mongers but rather as tragic heroes who waged war reluctantly. In an interesting twist, even Kobayashi himself today emphasizes the horrors, rather than the glory, of war in his latest “New” Treatise on War (Shin Sensōron).34

Narrating war history in a defeated nation is a complicated, painful project. As I describe in my book, it is part of a long process of repairing the moral backbone of a broken society after a monumental national fall. In Japan’s public discourse today, accounts of war memories are diverse and divisive, articulated through the interplay of multiple narratives of heroes, victims, and perpetrators. These narratives are intertwined with the nation’s moral recovery from defeat, to recover from stigma, to heal from the losses, and to right the wrongs. It would not be surprising, in this context, to see that war stories for children – such as study manga – diversify further in message and moral import in the future.

This article is adapted from Chapter 4 of Akiko Hashimoto, The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Japan (Oxford University Press, 2015). The author has lived and studied in Japan, Germany, England, and the United States, and taught cultural, comparative, global sociology at the University of Pittsburgh for 25 years. She is also a Faculty Fellow at Yale University’s Center for Cultural Sociology, and currently visiting professor at Portland State University.

Related Issues

• Tawara Yoshifumi, The Abe Government and the 2014 Screening of Japanese Junior High School History Textbooks

• Koide Reiko, Critical New Stage in Japan’s Textbook Controversy

• Matthew Penney, ‘Why on earth is something as important as this not in the textbooks?’ – Teaching Supplements, Student Essays, and History Education in Japan

• Nakazawa Keiji, Hiroshima: The History of Barefoot Gen

• Yuki Tanaka, War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The humanism of his epic manga

• Yoshiko Nozaki and Mark Selden, Japanese Textbook Controversies, Nationalism, and Historical Memory: Intra- and Inter-national Conflicts

Recommended Citation: Akiko Hashimoto, ““Something Dreadful Happened in the Past”: War Stories for Children in Japanese Popular Culture”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 30, No. 1, July 27, 2015.

Notes

1 Study manga often target school children in the latter years of elementary school and in middle school, typically ages 10-15.

2 The mainstream academic study manga discussed here became widely available in the early 1980s, and some have been reprinted as many as 50-60 times. The popular study manga by Fujiko, Mizuki, and Ishinomori became available in the 1990s. The iconic status of these manga artists is celebrated in their individual museums across the nation today.

3 Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. The past within us: media, memory, history. London: Verso. 2005, 170;

Penney, Matthew. “Far from Oblivion: The Nanking Massacre in Japanese Historical Writing for Children and Young Adults.” Holocaust and Genocide Studies (2008) 22:25-48.

4 Gakken Manga, Nihon no rekishi, volumes 1~17, 1982; Shōgakkan Shōnen Shōjo Gakushū Manga, Nihon no rekishi, volumes 1~21, 1983; Shūeisha Gakushūmanga, Nihon no rekishi, volumes 1~20, 1998

5 “Sensō o nikumu.” Shōgakkan Shōnen Shōjo Gakushū Manga, Nihon no rekishi vol. 20. 1983, 110

6 “Sensō – iyadane, sensō.” Shūeisha Gakushūmanga, Nihon no rekishi Vol.18. 1998, 58

7 Gakken Manga, Nihon no rekishi:15, 121

8 Shōgakkan, Nihon no rekishi: 20, 102.

9 Ibid. 157.

10 Shūeisha, Nihon no rekishi:18, 72,75, 98-104.

11 Shōgakkan, Nihon no rekishi: 20, 53, 58.

12 Ibid. 81.

13 Shūeisha, Nihon no rekishi: 18, 103. Shōgakkan, Nihon no rekishi: 20, 106.

14 Ibid. 115.

15 Shūeisha, Nihon no rekishi:18, 111.

16 Ibid. 114.

17 Gakken Manga, Nihon no rekishi:15, 121.

18 Nichinōken and Fujiko F. Fujio, Doraemon no Shakaika Omoshiro Kōryaku: Nihon no rekishi ga waraku 2: Sengoku~Heisei jidai, Tokyo: Shōgakkan, 1994, 192.

19 Ibid. 195

20 Ibid. 195

21 Ibid. 199

22 Ibid. 201

23 Ibid. 192, 200-1.

24 Mizuki, Shigeru. Sōin Gyokusai Seyo! [Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths Tokyo: Kodansha, 1995, 357.

25 Penney, Matthew. “‘War Fantasy’ and Reality – ‘War as Entertainment’ and Counter-narratives in Japanese Popular Culture.” Japanese Studies 2007, 27:35-52.

26 Mizuki, Shigeru. 1994. Komikku Showa shi. 8 vols. Tokyo: Kodansha. Thesevolumes are nowavailable in English translation, published by Drawn and Quarterly.

27 For example, Mizuki describes graphically how only one tenth of the soldiers survived the disastrous Imphal Campaign in 1944. Mizuki Shigeru Komikku Shōwashi:5, Tokyo: Kodansha, 1994, 26.

28 Mizuki, Komikku Shōwashi:8, 248

29 Ibid. 261-3.

30 Ishinomori, Shōtarō. Manga History of Japan Vol. 53, Tokyo: Chūōkōronsha, 1999. 22-23.

31 Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983. Hochschild, Arlie Russel. 1979. “Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure.” American Journal of Sociology no. 85:551-575.

32 Gakken Manga. NEW Nihon no rekishi 11: Taishō demokurashii to sensō e no michi. 2013. Tokyo: Gakken kyōiku shuppan.

33 Hamagakuen and Fujiko F. Fujio. 2014. Doremon no shakaika omoshiro kōryaku: nihon no rekishi 3. Doraemon no gakushū shiriizu. Tokyo: Shōgakkan.

34 Kobayashi Yoshinori. 2015. Shin-Sensōron 1. Tokyo: Gentōsha.