Henoko: The Experts Report and the Future of Okinawa

Part 1 of a three part series

1. Gavan McCormack, Introduction: The Experts Report and the Future of Okinawa

2. The Okinawa Third Party (Experts) Committee, translated by Sandi Aritza,

Those who refer regularly to this journal will be familiar with the “Okinawa problem.” The “Okinawa problem” is best understood as the consequence of a post-war 70 years divided into 27 that were under direct US rule as a military colony and 43 that have been nominally under the constitution of Japan but in practice under a Japanese government embracing subservience towards the US and support for its various wars. That has entailed shifting the burden of the US military presence as much as possible away from densely populated areas in mainland Japan and as much as possible onto Okinawa prefecture. The well-known statistic of 74 per cent of US base presence concentrated on Okinawa’s 0.6 per cent of the national land is the plainest expression of this.

Following the outburst of sadness, anger, and resolve that galvanized Okinawa in 1995 (over the rape of the Okinawan child by three US servicemen) and made clear the Okinawan demand that the inequality be ended and civil priorities substituted for military ones, the two governments agreed that the Futenma Marine Air Station would be returned within five to seven years. Nineteen years have passed since then, and no progress has been made. While Futenma still occupies its extraordinary position in the middle of the township of Ginowan, the two states have shown no interest in return, but concentrated instead on that of replacement. They would construct a “Futenma Replacement Facility” (FRF) which would be larger than Futenma, multi-functional (with the addition of a major military port), ultra-modern, more-or-less free of the nuisance of an adjacent civil population, and constructed by reclaiming much of the waters of Oura Bay, a site of extraordinary bio-diversity.

That project was anathema to a majority of Okinawans. So strong did anti-base sentiment grow that by 2012 virtually all Okinawan political parties and electoral candidates had adopted (however nominal the opposition in some cases later turned out to be) an anti-base stance (i.e. return Futenma without replacement anywhere else in Okinawa). That consensus included the Governor elected in 2010 and the major (conservative) Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

Such has been the strength of that opposition that so far only preliminary survey works on the project that was supposed to have been built and handed over to the Marine Corps between 2001 and 2003 have been undertaken. On paper, however, the project has steadily grown. The record of the remarkable struggle in those years that pitted the people of Okinawa against the Japanese state, reaching the point after 13 or 14 years of advantage to the former has been the subject of many essays at this site.

But the (second) Abe Shinzo government, from December 2012, has attached high priority to defeating this opposition. And implementing the FRF plan. Abe was determined that, where all other governments had failed to win over Okinawan opposition, he would win it over or crush it. He repeatedly promised US president Obama that the base would be built and handed over. After a year of intensive effort, late in 2013 he accomplished the “surrender” (to the pro-base cause) of both the Okinawan LDP members of the national Diet and, late in December, the Governor himself.

That in turn, however, stirred the Okinawan anti-base forces to a new level of mobilization that resulted in a series of political victories through 2014: the return of the anti-base (“no new base in this city whether on land or on sea”) mayor of Nago City, which includes Henoko and Oura Bays, the designated new base construction site at Henoko), and in September of a majority who supported him to the City Assembly, the election in November of a Governor, Onaga Takeshi, pledged to “do everything in my power to stop the construction of any new base” and in December of anti-base representatives to all four Okinawan seats in the national Diet lower house elections. Opinion polls registered sentiment of opposition to the base project in the 70 per cent range, reaching occasionally into the 80s.

Yet, ignoring these repeated expressions of Okinawan democratic opinion, in July 2014 the Abe government declared much of Oura Bay “off-limits” and commenced a boring survey of the ocean floor, the first step towards reclamation and construction.

The gubernatorial election of November 2014 was conducted with base policy its central issue, amid strong and rising public anger. Having triumphed in the election, it was expected that Onaga would actually “do everything in my power” to stop base construction by cancelling the permit issued by his predecessor for reclamation of the Oura Bay site for the base. Instead, he acted slowly, making a series of appeals to the Abe government (which dismissed them and for months refused even to meet him), and setting up a commission to investigate and advise him. It is this Commission, the “Third Party Commission on the Procedure for Approval of Reclamation of Public Waters for the Construction of a Futenma Replacement Airfield,” that has now issued its report.1 Setting it up took several months. One reason for the prolonged delay was said to be that he sought “experts” who would be “neutral” and “objective,” and that meant to exclude by definition those lawyers (who were many) that had been identified in one way or another with base opposition, including the defence of civil protesters against the base project, and likewise to exclude many environmentalists while seeking only or primarily those who had never taken a position on Okinawa’s environment. The Governor was looking, in other words, for those who by 2015 had never identified themselves with the demand for a proper environmental assessment or denounced the looming destruction of Oura Bay. Eventually, the six member Commission set up in late January comprised lawyers Oshiro Hiroshi. Tajima Hiroki, and Toma Toshiaki, and environmentalists, Sakurai Kunitoshi, Taira Keisuke, and Uchiya Makoto. All may be described as “eminent,” but only one, Sakurai Kunitoshi (former president of Okinawa University), was known to have a record of critical involvement in the base and environmental issues. We present below a new and penetrating analysis of the base and environmental problems by Professor Sakurai.

The Commission adopted a fortnightly schedule that saw its deliberations continue for nearly six months, a ponderous process that contrasted with the determined efforts by the Abe government to push the project forward with the evident design of making construction a fait accompli, while refusing to listen to Onaga and excluding and intimidating the civil protesters at the site. Onaga’s words became increasingly severe, calling the national government in talks with its various senior ministers, “condescending,” “unreasonable,” and even “depraved,” and telling the Prime Minister that,

“Construction of Futenma and other bases was carried out after seizure of land and forcible appropriation of residences at point of bayonet and bulldozer, while Okinawan people after the war were still confined in detention centres. Nothing could be more outrageous than [for you] to try to say to Okinawans whose land was taken from them for what is now an obsolescent base [i.e. Futenma], the world’s most dangerous, that they should bear that burden and, if they don’t like it, they should come up with an alternative plan.”2

But, for all the fierceness of his words, he took no decisive action.

It was during these months that criticism and suspicion of Onaga began to circulate in Okinawa. Could it be, as some suggested, that he was essentially an unreformed LDP member, sharing the same conservative affiliations and orientation as Prime Minister Abe, and that he would maintain the façade of opposition but take no decisive steps?

As one Okinawan colleague commented:3

“Onaga could maintain his official position to “stop Henoko with all the means possible” while Tokyo simply continues the works. At the end Onaga could say he had done everything possible but could not stop it, while Henoko is complete.”

The answer to that question will soon be known.

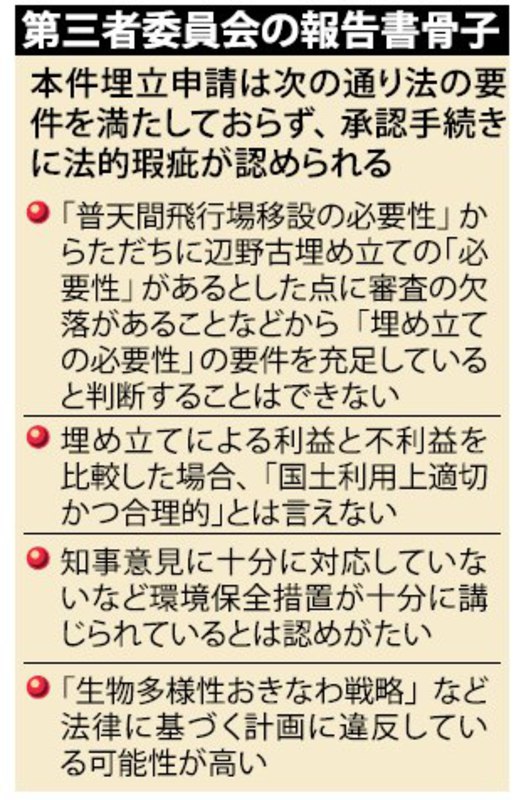

When the Commission finally delivered its report on 16 July (see the “Main Points” presented in translation below; the complete report in Japanese is here) it amounted to an unambiguous finding of multiple procedural “breaches” (kashi) in the way the Nakaima administration had made its crucial December 2013 decision to approve the environmental assessment. It found, in short, that the basis of the reclamation project was legally flawed, and thus opened the path for Onaga to cancel the reclamation license.

The Sakurai paper we attach below goes in some detail into the nature of those breaches. “Necessity for reclamation,” a crucial consideration under the Public Waters Reclamation Law (under the 1973 revision to the 1921 law), had not been established. And, of the six specific criteria under Article 4 of that law for reclamation, the Henoko project failed on three. It did not meet the tests of proof of “appropriate and rational use of the national land,” proper consideration for “environmental preservation and disaster prevention,” and compatibility with “legally based plans by the national government or local public organizations regarding land use or environmental conservation.” It was also incompatible with other laws including the Sea Coast Law (1956) and the Basic Law for Biodiversity (2008).

While it is true that, in a sense, the most notable thing about the new Report was that it contained nothing new, and could have been written by having the members sit around a table in January, when in fact documents with essentially the same content as the July report circulated already in Naha, nevertheless its findings opened a clear path for Onaga, should he so choose, to cancel the legal basis for the reclamation and base construction works. To do that would amount to an emphatic “No” to the national government and to its US partner. It might actually accomplish what Onaga had been promising: stop the works.

As to whether Onaga will now, at last, actually cancel the deeply flawed reclamation license, however, the outlook is not clear. Onaga has indicated that he intends to further examine (kensho) the report, treating it with the utmost respect (saidaigen soncho) and perhaps reopening discussions with Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide about it. Some expected that he would in fact set up a new committee to advise him further, however both major Okinawan newspapers reported their expectation that he would indeed move ahead to cancel the reclamation license “before the end of August.”

For its part, the Tokyo government has already served notice that it would ignore any “cancellation” ruling from the Governor, but the legality of any government steps to carry the project forward after such cancelation would be dubious at best. It would raise the question of the “rule of law,” on which Prime Minister Abe has repeatedly insisted in recent statements before various fora including the US Congress.

As I noted in The Japan Times,4

“For the government of Japan to step back from its many times repeated pledges that this new base will be built and handed over is unthinkable. It is equally unthinkable, however, for the Governor and people of Okinawa to step down. The stage is set for a long, bitter, destabilizing battle, without precedent and without prospect of resolution.”

Onaga Takeshi – a lifelong member of the ruling LDP (a party membership he shares with the Prime Minister and most members of the Abe cabinet) is an unlikely figure to lead Okinawa prefecture through a process of confrontation with the national government that seems certain to involve sharpening clashes between Abe enforcement officers of the National Coastguard and Riot Police and protesting Okinawan citizens on land and sea at the actual site, and courtroom and political arena clashes in Tokyo, while challenging a fundamental element in the strategic agenda of Tokyo and Washington.

For all his “successes” on other fronts, Abe has not been able to bend Okinawa to his will. As another Okinawan friend recently commented: “If Abe is to be stopped, it will have to be by Okinawans,” i.e. the level of consciousness and determination reached by nearly 20 years of intense struggle has turned Okinawa into a region with high political consciousness and so far unshaken determination, and provided Okinawans are given the support they deserve by democratically inclined citizens within Japan and by international movements for peace, democracy and human rights, and provided the present Governor does not betray Okinawans as his predecessor did, the prospect is not dark.

However improbable a people’s victory, it is not implausible and, though much delayed, and though it contains nothing actually new, the Third Party report provides a cogent statement of the Okinawan cause. Of one thing there can be no doubt: there is no prospect of any early resolution of the almost two decades of constant struggle that marks the history of modern Okinawa. A greater battle than ever lies ahead.

Gavan McCormack is an editor of The Asia-Pacific Journal and author of many studies of modern Okinawa and Japan, including (co-authored with Satoko Oka Norimatsu) Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, Rowman and Littllefield, 2012. This latter book, like much of his recent work, has been published in Japanese, Korean, and Chinese as well as English.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, “Introduction: The Experts Report and the Future of Okinawa”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 29, No. 2, July 20, 2015.

Notes

1 “Futenma hikojo daitai shisetsu kensetsu jigyo ni kakawaru koyu suimen umetate tetsuzuki ni kansuru daisansha iinkai”

2 “Onaga chiji, Abe shusho kaidan zenbun (boto hatsugen),” Okinawa taimusu, May 19, 2015.

3 Personal communication, July 18 2015.

4 “Legal flaws in government’s case on Henoko,” Japan Times, July 17, 2015.