On September 9, 2014, the Imperial Household Agency released to the public its carefully vetted Authentic Account of the Showa Emperor’s Life and Reign (Showa Tenno Jitsuroku). This was the long-awaited official version of nearly every aspect of Emperor Hirohito’s long life and reign. Compilers, researchers, and outside scholars of the Agency’s Archives and Mausoleum Department—including a few specialists in modern Japanese history–started on the project in 1990. It took nearly a quarter century to finish. Through negotiations they secured the cooperation of imperial family members, chamberlains, and others who had worked closely with the emperor and were prone to self-censorship in revealing what they knew about him. They collected a huge trove of 3,152 primary materials, including some unpublished, even unknown diaries of military and civil officials, all of which were arranged chronologically in 61 volumes.1

|

The Showa Emperor in 1988. The present Emperor Akihito is at left. |

Included in the Jitsuroku are documents that flesh out his childhood, education, and regency during which his protective entourage instructed him to study hard so that he could participate fully in political and military decision making once he took up his duties as emperor–something his chronically ill father the Taisho emperor had been unable to do. Precious material on who and when the emperor met civil and military officials was included, thereby enabling historians to construct more accurate chronologies of decision making for war and diplomacy. Confirmed by documents beyond any doubt was the emperor’s bullheaded insistence on delaying surrender when defeat was clearly inevitable–inevitable, that is, to everyone but him. The U.S. firebombing of Japanese cities, the mass slaughter of civilians in the Battle of Okinawa, and the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed as fateful consequences of the decision to postpone surrender.

Journalists, writers, and a few specialists in modern Japanese history who were given pre-publication access to a PDF file of all volumes, quickly realized that the Jitsuroku can never stand as a truthful record of the emperor’s entire life, perhaps least of all that portion of it in which he participated with others in guiding the China war from 1937 onward and later when he joined the war party by selecting Gen. Tojo Hideki as prime minister in October 1941, and thereafter extended the China conflict to the vast Asia-Pacific region.

Despite publication of valuable new materials, some commentators saw that the Jitsuroku dodged questions about important events before, during, and after Japan’s lost war. The official history does not have truth as its objective. Rather, it is based on the premise that the emperor was a non-political, constitutional monarch. In that sense it is a form of domestic propaganda and fails to compel a major revision of existing critical biographies and monographic studies of the monarchy by eminent Japanese historians.2 The critical works show that from the start of his reign in 1926 the young Showa emperor was a dynamic, activist and conflicted monarch operating within a complex system of political irresponsibility inherited from his grandfather, the Meiji emperor.

This system veiled him in secrecy, leaving him conveniently free to act energetically behind the scenes, guiding the nation’s course with the aid of close court advisers. Japanese historians had already established that during the period of the Manchurian “incident” (1931-33), which marked the start of Japan’s long war in China, the emperor knew full well his will had been violated by a cabal of Kwantung Army officers. But he sanctioned their aggression after the fact for he believed Japan’s colonial implantation in Manchuria had to be protected from Chinese nationalism, and also because his political advisers discouraged him from acting as he wished.

The tactic that Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Makino Nobuaki and retired elder statesman Saionji Kinmochi used to justify compromising with the military was imperial “constitutionalism.” Meiji had bequeathed Showa not only an empire with treaty rights in China but also a constitution that he could hide behind while operating secretly and energetically. Further complicating the picture was his special relationship to the army and navy which he alone directly commanded, and his need to uphold the principle of constitutionalism even though it was merely a tactic for avoiding responsibility for his actions. The complex Meiji system of oligarchic government enabled a privileged few to dominate decision-making and mandated Hirohito to play multiple roles and wear many faces. He was chief priest of State Shinto, supreme commander of the armed forces, superintendent of all the powers of sovereignty, and the nation’s teacher of morality, accountable only to his dead ancestors. Moreover, the Meiji constitution gave priority to his imperial will rather than the Cabinet’s, and it did so before prime ministers ever brought policy documents to him to approve.3 The emperor worked hard to maintain this system.

Also assisting Hirohito in strengthening the monarchy was religious myth grounded in “state Shinto” and in the notion of him as the unifier of rites and governance. Hirohito knew quite well he was not a living deity but thought it good if the people, especially his armed forces, believed he was. Thus, Hirohito can be called a leader comfortable with deceiving the public but at no time before 1946 can he be called a real constitutional monarch; nor was he one afterwards when the new American-modeled constitution redefined him as “the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people.”

***

The Jitsuroku compilers summarize historical documents and quote directly from them when it made the emperor look good. The reader is left to analyze events of Hirohito’s reign on his or her own without access to many key documents. The official history fails to provide a clear picture of Hirohito documents that remain classified. Omitted from the official history are many of the emperor’s exchanges with important foreign leaders. It is unclear, for example, whether the Jitsuroku includes the stenographic records kept by Japanese interpreters at his meetings with General MacArthur during the occupation. We need to know whether, after the new constitution went into effect, Hirohito actually lobbied MacArthur for a military relationship with the U.S. at their fourth meeting (May 6, 1947), or at their tenth meeting (April 18, 1950) pressed him to crack down on Japanese communists. Has the Jitsuroku ended speculation about what was said at these meetings?

Quite apart from its method of presenting materials, the official history fails to consider the glaring shortcomings of the emperor’s performance as a leader, and the institutional structures and legal documents on which rested his performance down to Japan’s capitulation on August 15, 1945. These included the 1889 Meiji Constitution and the 1890 Education Rescript, which confirmed his exclusive authority as the nation’s teacher of morality.

In dealing with the postwar emperor the compilers give little consideration to the meaning of the 1946 Constitution of Japan, which preserved the throne with the wartime emperor on it but stripped of political power. This incorporation of the monarchy into Article 1 of the constitution created long-term problems. It meant that postwar Japan, unlike postwar Germany, could not be reformed on the basis of a fundamental disavowal of its wartime past. That was impossible to do because the Americans preserved the single most important component of the prewar state–the emperor–and never interrogated or indicted him to face war crimes charges. So General MacArthur was free to use him for his own purposes of occupation control while Japanese ruling elites adapted to American policies and rarely stood up publicly to Washington’s policies no matter how illegal or unjust they were.

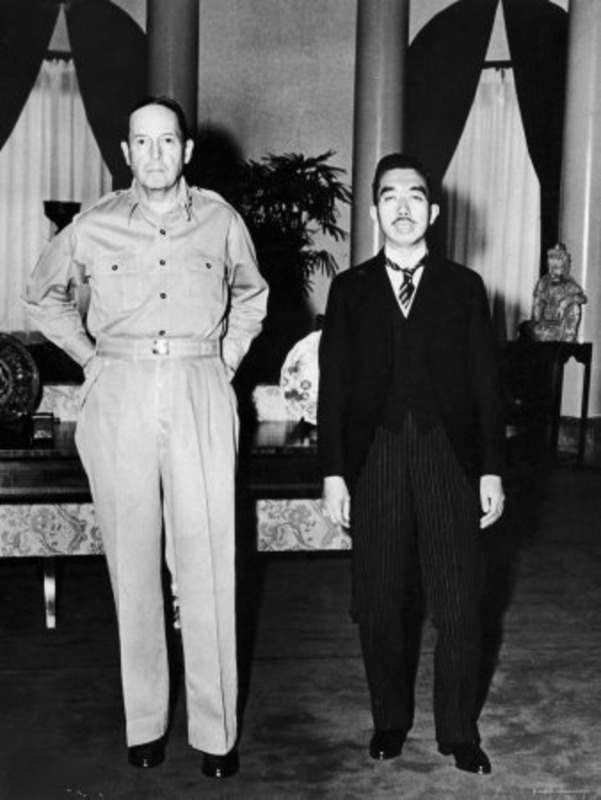

|

MacArthur and Hirohito |

To the end of the Showa era it was nearly impossible to question Hirohito directly about his war responsibility. When he and his wife held a televised press conference at the palace on Oct. 31, 1975, a few weeks after his return from the U.S., an intrepid Japanese journalist, Koji Nakamura, dared to ask him an “improper” unscripted question: “Does your majesty feel responsibility for the war itself, including the opening of hostilities [that is, not just for the defeat]? Also, what does your majesty think about so-called war responsibility?” A stiffed faced Hirohito replied: “I can’t answer that kind of question because I haven’t thoroughly studied the literature in this field, and so don’t really appreciate the nuance of your words.” When Nakamura asked in addition about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Hirohito gave this reply: “It couldn’t be helped because that happened in wartime.”4 The prewar tendency to carry respect for the monarch to extremes may explain why even today, when there is no lese majesty law, Japanese journalists still tend to draw a veil over the symbol monarchy.

On several occasions during and after the occupation period Hirohito violated the letter and the spirit of the nation’s “peace” Constitution. On Sept. 20, 1947, for example, he used the interpreter and spy Terasaki Hidenari to carry his colonialist views on the future of Okinawa to MacArthur’s political adviser, William J. Sebald, who then reported them to Washington. On another occasion Hirohito participated indirectly in selecting the men who would be indicted and stand trial at the Tokyo War Crimes tribunal. Although the Constitution confined Hirohito to a mere ceremonial role, he continued to play a secret political role in both foreign and domestic affairs whenever circumstances permitted.

None of these events are addressed in the Jitsuroku. It does not explore how Hirohito fostered the ethos informing Japanese politics in the 1930sand early ‘40s, and the lasting stain on the monarchy caused by his refusal to abdicate and accept responsibility for his actions on the different occasions when he had the opportunity. The Jitsuroku further ignores the legal structure of the postwar “client state” that dutifully serves U.S. imperial interests. The 1951 Japan-U.S. military alliance and the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty that forced Japan to accept all the judgments of the international war crimes trials are also not discussed. After Hirohito’s death critical historians and progressive journalists vigorously debated his war responsibility and the role that the monarchy played in weakening the pacifist principles embedded in the Constitution. But nowhere are those debates reflected in the Jitsuroku.

In short, despite the historical value of many of its documents, the Jitsuroku can be characterized as the sanitized political history of a nation that was not allowed to break completely with its wartime past. Not surprisingly, it reaffirms the false official view of Hirohito as a pacifist and normal constitutional monarch. NHK, Japan’s state-owned broadcasting corporation even claimed that Hirohito always “valued party politics and international harmony.” Such misleading assertions about a monarch who conceived of himself as the occupant of a divinely descended throne, distrusted party politicians, and whose actions were protected from criticism by a framework of meaning inculcated in the schools, simply defy reason. In this sense, the official Showa history drives home an ideology impenetrable by factual evidence and has some of the features of a carefully contrived apologia just as the Showa Emperor’s famous “Monologue” (Dokuhakuroku), dictated to six close aides in 1946 and now included as a major source in the Jitsuroku, was to a much greater extent.

One purpose of the Monologue was to answer questions that Hirohito’s aides thought might be put to him by MacArthur’s staff prior to the Tokyo war crimes trial; another was to establish myths about why he had sanctioned war in 1941 and why, three and a half years later, on the night of August 9-10, 1945, he intervened politically to break a deadlock among his divided ministers of state and other participants in his Supreme War Leadership Council. This meeting and others that followed was carefully staged to convey the message that Hirohito saved the nation (and the monarchy) from destruction. By contrast, the Jitsuroku, which also deals with key turning points in the emperor’s life when he made disastrous errors of judgment and incorrect assessments of geopolitical situations, is intentionally designed to foster Japanese pride in the “symbol monarchy,” enhance its prestige, and promote the same theme of the benevolent emperor tirelessly working for peace.

***

For reasons stated above, the official history of Showa and its timing links to the political climate in today’s Japan. It appeared after the Japanese nation experienced in 2011 the Fukushima triple disaster, the serious escalation of ongoing maritime disputes with China and South Korea, and the deepening of persistent economic crises. If we focus our attention on the start of a new recession triggered by Abe’s sales tax increase and the widening since the 1990s of the wage gaps between classes and generations, crisis consciousness becomes understandable.5 The Jitsuroku’s appearance also coincided with preparations for the forthcoming seventieth anniversary of the ending of the war. All of these events furnish the necessary backdrop for assessing Abe Shinzo’s historical revisionism and the beliefs that support it.

Abe knows Japan is unique not only because of its war-renouncing constitution, but also because issues of war responsibility cannot be pursued in Japan without bumping against the Showa emperor’s personal leadership during the war, and his rapid transformation afterwards into the nation’s symbol. How can Abe change Japan into a state capable of fighting wars while at the same time avoiding the emperor issue that is also a war crimes and impunity issue? This is the same dilemma all governments in postwar Japan have confronted. But Abe’s hawkish ideological inclinations, not to mention his genealogical background as the grandson of Kishi Nobusuke–wartime munitions minister in the Tojo cabinet, later imprisoned as a war crimes suspect–may make him feel the situation more acutely than his predecessors did. Yasukuni Shrine visits and “comfort women” threaten to raise unresolved problems that lie in the background to the “official history” of Hirohito’s reign.

The issue of “comfort women,” i.e. the sexual enslavement of Korean, Chinese, and Southeast Asian women by wartime Japan’s military, is particularly salient for rightist politicians. When Abe succeeded Koizumi Junichiro in September 2006, he established Japan’s first Defense Ministry since the end of World War II and revised the liberal 1947 Fundamental Law of Education so as to strengthen state control and cope with the deepening splits in society exacerbated by neo-liberal economic policies.6 The amended education law allows the teaching of religious education, curtails teachers’ freedom of expression, and could be interpreted as promoting mystical “Japanese-ness.”7 But Abe also wanted to undo the impression widely held abroad that the imperial armed forces had once forced women into sexual slavery. His one-year in office did not permit him to do that.

Five years later in December 2012 the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ collapsed, new parties formed, and the LDP again emerged victorious at the polls, assuring Abe’s return to power as prime minister. While maintaining his ties to the bureaucratic and big business elites , he has kept lines open to the bigoted ultra-nationalist right and is now strengthening nationalism and fighting an ideological battle to restore lost “honor.” Abe’s primary goal, however, is to reshape political rule so that Japanese capitalists can maintain their position as global economic competitors whatever the social costs to the majority of Japanese workers and their families.

Abe’s unwillingness to accept the verdicts of the Tokyo Trial as promised in the San Francisco Peace Treaty is part of his revisionism. His reshaping of Japan entails changing the legal basis on which the post-World War II state rests as well as changing the consciousness of the Japanese people about the lost war, the emperor’s role in it, and the war crimes issues that once tarnished the state’s reputation.8 In Abe’s view, key parts of the Constitution need to be rewritten. Constitutional restrictions on Japan’s support of imperial America’s endless wars and interventions in other nations need to be eliminated. One way of weakening the constitution’s pacifist principles is to create conditions that will strengthen taboos on criticism of the symbol monarchy; another is to bring the press into line.

At a Budget Committee session of the House of Representatives on Oct. 3, 2014, Abe noted that “false reports” by the Asahi shimbun “gravely damaged Japan’s reputation abroad” and that ‘the groundless defamation of Japan ‘as a state that was involved in sexual slavery’ has spread globally.’”9 The LDP government’s persistent attacks against the liberal Asahi for alleged errors in reporting on the wartime comfort women system already has caused Japanese journalists, editors, and television commentators to hold back in their reports on this controversial issue. When editors initially denied that some errors had occurred in their news reports on this evil and sought to cover them up, the right-wingers in and out of government pounced and their actions have had demoralizing effects on liberal journalists.

Uemura Takashi, the retired Asahi shimbun investigative journalist who a quarter century ago told the story of a former “comfort woman” from Korea, has been branded a traitor and threatened with violence by right wingers who accuse him of disseminating “Korean lies.” In their effort to generate a positive portrayal of imperial Japan, Abe and the right are making an object lesson of the Asahi. Because of their attacks more than a quarter million subscribers have already dropped their subscriptions. Worse still, the Asahi editors have not defended Uemura, whose university teaching job was threatened.10 Thus academic freedom of expression has also been affected.

In addition, even the conservative Yomiuri shimbun and the Sankei shimbun have been attacked by the government for the words they used in reporting on the Nanjing massacre and sexual slavery issues. In both cases editors caved to the pressure and issued apologies to their readers. 11

Nevertheless, despite the present clamp down on expression concerning imperial history, critical viewpoints manage to get stated in mainstream Japanese news media, particularly those outside the capital. As for Abe, while continuing to pursue historical revisionism, when opposition to his policies becomes too insistent to ignore, he is flexible enough to amend his goals and return to the older method of changing the Constitution through reinterpretation.

Meanwhile, Okinawans have not forgotten that Hirohito twice sacrificed them: first by turning their island into a battlefield in order to gain time for the defense of the home islands, second by consenting to indefinite American military control of Okinawa. Later he encouraged permanent maintenance of the overwhelming American base presence on the islands after the 1972 reversion of administrative rights to Japan. The Jitsuroku has kept those embers of memory burning by failing to address the responsibility of the emperor and the Japanese state for the devastation of Okinawa and for not meeting the need of Okinawans for a land cleansed of the overwhelming presence of military bases.

***

Next month some Okinawans will call attention to February 14, 1945, the seventieth anniversary of the day that the senior statesman Prince Konoe Fumimaro presented a written report to Hirohito in which he told the emperor after endless defeats the war was irrevocably lost and he should surrender immediately, without negotiation. Hirohito’s fateful negative response–we’re going to hit them hard one more time, then we’ll talk about it–was the prelude to the Battle of Okinawa. Six weeks later the battle started and more than one quarter of Okinawan civilians died following this decision of the emperor. On June 23 all Okinawans regardless of whether they support American bases or not will be commemorating the seventieth anniversary of the virtual end to the battle fought to buy time for the defense of the homeland.

When the Showa era ended with Hirohito’s death on January 7, 1989, the outpouring of interest in his reign lasted for more than a decade, during which historians and journalists fiercely debated his and the state’s war responsibility. Now, a quarter-century later nationalism in Japan and throughout East Asia has strengthened.

Every five years since 1973 NHK researchers conduct a survey of opinion on Japanese life and society, asking the same questions of individuals from 16 to age 75 and older chosen from every part of the country. The ninth and latest NHK survey, carried out in late October 2013, polled 3,070 interviewees. The survey’s major finding on the emperor question was this:

Last time and this time the number of persons who said they have respect for the emperor increased. It has now increased by 34 percent and is parallel to the 33 percent seen in the Showa Emperor’s period. The percentage of interviewees who admire the emperor increased as the generations got older and shrunk as they got younger. In addition, this [trend] remained unchanged until the early 2000s. But during the past decade the percentage of those who respect the emperor increased in nearly every single generation.12

This passage clearly links rising nationalism to centripetal tendencies in Japanese politics focused on the symbol emperor. Yet a cursory search of articles on the Jitsuroku, using the National Diet Library search engine, turned up only 37 articles in the months of October, November and the first week of December 2014. Most of them appeared in in mass circulation newspapers and small, monthly and weekly tabloids. Of the latter, many leaned to the right or far right; and half of all the articles were serialized by Hosaka Masayasu and Hando Kazutoshi–two writers who appear often in the conservative monthly Bungei shunju. Few professional academic historians and political scientists specializing on the Showa era have as yet weighed in with careful investigations of the actual contents of the documents in the Jitsuroku, though this is likely to change. Meantime, in political and rightwing circles, the myth of the “pacifist,” “normal constitutional” Showa emperor–who was actually the chief protagonist in the militarist phase of Showa history–continues to be re-affirmed.

The author responded to a request from the Chosun Ilbo for responses to its question. The Q&A is here.

Herbert P. Bix is emeritus professor of history and sociology at Binghamton University, and the author of Peasant Protest in Japan, 1590-1886 and Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. His essays on foreign policy and Japanese history have appeared in books, scholarly journals, and leading newspapers in many countries around the world. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal Contributing editor.

Recommended citation: Herbert P. Bix, “Showa History, Rising Nationalism, and the Abe Government,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 2, No. 4, January 12, 2015.

Related articles

•Herbert P. Bix, Abe Shinzo and the U.S.-Japan Relationship in a Global Context

•Herbert P. Bix, War Responsibility and Historical Memory: Hirohito’s Apparition

NOTES

I thank Mark Selden, John Dower, and Gavan McCormack for helpful comments.

1 Henshubu, “Kunaicho OB ga akashita hensan no uchimaku,” Bungei Shinjjuu, October 2014, pp. 124-130.

2 For over half a century historians and political scientists wrote important critical works on Hirohito and his performance as emperor. To name just a very few: Inoue Kiyoshi, Awaya Kentaro, Fujiwara Akira, Yoshida Yutaka, Yamada Akira, Watanabe Osamu, and Nakamura Masanori.

3 Herbert P. Bix, “Hirohito: String Puller, Not Puppet,” New York Times, Sept. 29, 2014.

4 Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan (HarperCollins Publisher, Perennial, pb, 2000), p. 676. The brave journalist who dared to ask these questions was Nakamura Koji. See Norihiro Kato, “The Journalist and the Emperor: Daring to Ask Hirohito About His Role in WW II,” New York Times Op-Ed, Oct. 14, 2014.

5 Yuka Hayashi, “Piketty on Japan: Wealth Gap Likely to Rise,” The Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2014.

6 Watanabe Osamu, “Abe seiken to wa nani ka,” in Watanabe Osamu, Okada Tomohiro, Goto Michio, Ninomiya Atsumi, ‘Taikoku’ e no shitsunen—Abe seiken to Nihon no kiki (Otsuki Shoten, 2014), p. 147ff. and private e-mail communications with Professor Watanabe.

7 Adam Lebowitz and David McNeill, “Hammering Down the Educational Nail: Abe Revises the Fundamental Law of Education, Japan Focus, July 9, 2007.

8 Gavan McCormack, “The End of the Postwar? The Abe Government, Okinawa, and Yonaguni Island,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 12, Issue 48, No. 3 (Dec. 8, 2014).

9 Committee of the Historical Science Society of Japan (Rekishigaku kenkyukai) Public Statement, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, English translation of Dec. 5, 2014.

10 Martin Fackler, “Rewriting the War, Japanese Right Attacks a Newspaper,” New York Times Dec. 2, 2014.

11 “Reexamining the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue: An Interview with Yoshimi Yoshiaki,” transl. by Yuki Miyamoto, introduced by Satoko Norimatsu, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 1, No. 1, Jan. 5, 2014.

12 “Dai kyukai Nihonjin no ishiki chosa” (2013).