1. 2014: Year 18 of the Anti-Henoko Base Struggle

If 2014 was a year of consolidation on the two opposing sides of the long-running Okinawan saga over US military base hosting plans, 2015 promises to be one of intense, perhaps decisive struggle. By 2014, civic groups had established a strong institutional power base in the city administration in Nago and the prefectural one in Naha, while resistance continues also at Takae in the Yambaru forest (against the construction of “Osprey pads” for the Marine Corps), and on Yonaguni Island, where the town assembly has called a plebiscite on the issue of the construction of a Self-Defense Force base, to be held on 22 February 2015. But the Japanese state had shown itself to be implacable in its determination to push ahead with its long delayed project for the construction of a major military complex for the US Marine Corps at Henoko, in Northern Okinawa. Since the national government is unbending in its determination to overrule Okinawan dissent and the “Okinawan problem” was scarcely mentioned during the national elections of December 2014, Prime Minster Abe Shinzo has a more-or-less free hand to deploy whatever resources of the state he wishes in order to crush opposition and implement his design on all fronts.

Through 2014, Okinawan civil society delivered powerful messages to the government in Tokyo, to the nation, and to the government of the United States on three major fronts. In January, citizens of Nago City returned to office its mayor, Inamine Susumu, who was an uncompromising opponent of any base construction within the city (and in September, Inamine supporters retained control of the City Assembly); in November, the Okinawan electorate decisively rejected the Governor, Nakaima Hirokazu, who had reneged on his pledge to oppose base construction and issued the permit the government needed to commence reclamation of Oura Bay, electing in his stead a candidate committed to doing “everything in my power” to stop construction at Henoko, close Futenma Air Base, and have the Marine Corps’ controversial Osprey MV 22 aircraft withdrawn from the prefecture (and therefore stopping the construction of “Osprey Pads” for them in the Yambaru forest, also in Northern Okinawa); and in December all four Okinawan local constituencies elected anti-base construction candidates to the lower house in the National Diet.1

But if the anti-base struggle recorded significant political victories during 2014, it also suffered reverses. Its leaders knew that what counted was the eventual strategic outcome, not the interim tactical skirmishes, and that the odds were stacked against them to an almost impossible degree. During 2014, all five judges of the Supreme Court’s 3rd Petty Bench rejected the complaint of 344 residents against the Henoko project on grounds of a flaw in the environmental assessment process, confirming the two lower court decisions that held residents had no standing to make such complaint.2 As for the “Osprey pads” being constructed in the Yambaru forest at Takae for the Marine Corps, the government late in 2014, having failed to exclude local protest by securing various restraining “SLAPP”-type court orders,3 was planning to transfer control over the No 70 prefectural road to the US military, assuming that it would effectively brush aside protest when works resumed in January 2015.4 On Yonaguni Island, the situation was more opaque. The Town Assembly in 2014 adopted a resolution to conduct a plebiscite on the government’s plan to construct a Self-Defense Force base. Eventually a February 2015 date was set, but the government has already acquired a site and commenced construction. The state would not be easily stopped. It would likely brush aside any unfavorable expression of island opinion. Neither the Okinawan community in general nor incoming Governor Onaga had adopted any clear position on the question of Japanese military bases in the Southwestern frontier islands (including Yonaguni). But sooner or later, and probably sooner, both would have to do so.

In accordance with the Abe design and despite the opposition, construction works began on the much contested base project at Henoko in July 2014, but the combination of fierce and continuing Okinawan protest, unstable (typhoon) weather, and the exigencies of elections led to them being several times suspended, and not resumed after late November. Suspension was not reprieve, however. Budgetary allocations were unchallenged, tenders continued to be let, landfill sought and allocated, and Abe continued to assure the US government that the works would proceed according to plan, regardless of Okinawan sentiment.

Nakatani Gen, newly appointed Defense Minister in the reorganized Abe cabinet of December 2014, offered the bizarre, and to Okinawans deeply insulting justification for the concentration of US forces on Okinawa, including Camp Schwab/Henoko, that no other district in Japan would have them, implicitly assigning a lesser weight to the sentiment of Okinawans compared to residents of other prefectures. As his Democratic Party predecessor, Morimoto Satoshi, had put it, the reasons were not to do with military considerations or deterrence but were political. A presence that nobody wanted would be imposed on Okinawa rather than anywhere else because it could be, and because that was what successive governments in Tokyo had found the easiest path.

In the immediate aftermath of Onaga’s election, there followed a brief flurry of construction activity at Henoko. One week afterwards, however, it suddenly stopped and even sundry construction-related structures were dismantled and removed, presumably in recognition by the Abe government of the adverse political consequences of defying Okinawan opinion leading up to the lower house national elections that it had called for 14 December. Works have not since been resumed, but preparations continue and late at night on 10 January a series of concrete mixers entered the Camp Schwab construction site, provoking violent clashes with protesters ahead of full works resumption expected on 12 January.

2. 2015: Change of Regime – Nakaima to Onaga

Although the Nakaima consent in December 2013 to the government’s reclamation plans seemed to resolve one large problem for the Abe government and open the door to survey and construction, the fact that just one month later Nago City, site of the projected base, returned the determinedly anti-base Inamine Susumu as mayor greatly complicated things. Nago City administered major resources and facilities that have been ear-marked for the base project, including water and landfill and the fishing port of Henoko, originally designated as site for a large works yard. Having failed to unseat Inamine or weaken his city control, the government in 2014 sought ways, if not to persuade him, then to evade his power of veto. That meant concentrating more of the project on the existing Camp Schwab, which being under complete control of the Marine Corps was inaccessible to protesters, a kind of “Guantanamo” within an Okinawan “Cuba.”

|

Four Major Changes sought by the Okinawa Defense Bureau in September 2014 to the December 2013 Henoko Plan. |

Early in September 2014, the Abe government submitted to the then Nakaima-led Okinawan prefecture a request for variation of the plans approved the previous December.5 The new plans envisaged various works, including three additional roads to be constructed through Camp Schwab and the diversion and sinking underground of a 1,022 metre stretch of the Mija River that exits through Camp Schwab (instead of the initially planned 240 metres). Much about the formal application was vague, and it only later was revealed that the construction of a 300 metre long “temporary” wharf, between 17 and 25 metres wide and requiring over 20,000 cubic metres of landfill, on the Camp Schwab-fronting sea was part of it.6 Then, shortly after his electoral dismissal, and just four days before his ignominious departure from office, Nakaima issued his formal consent to two of the original four alterations, after deleting, without explanation a third – diversion of the Mija River). 7 That left the question of a system of road delivery for refill from the Henoko Dam site to replace the planned conveyor belt (that Nago City would certainly block). This had been the subject of a series of questions and answers between the Department of Defense in Tokyo and the Okinawan prefecture so that the file on Onaga’s desk when he took office was known as the “Fifth Question.” 8

|

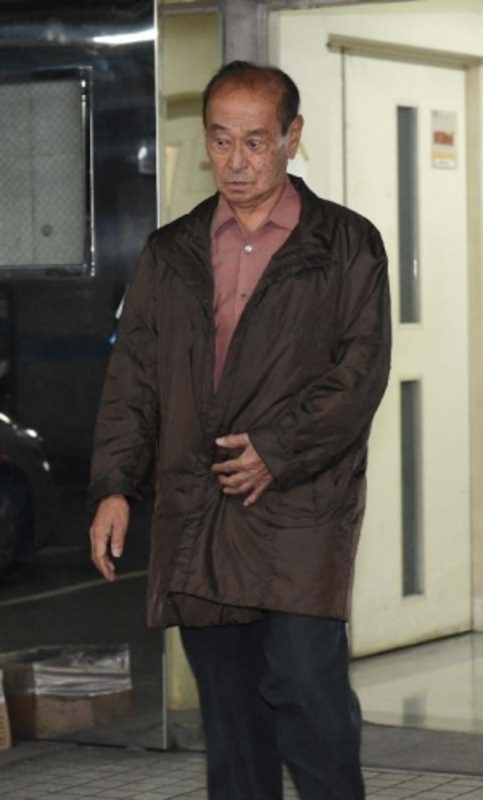

Governor Nakaima evades protesting Okinawan citizens by leaving his office by the back stairs, two days before departing permanently, 8 December 2014 (Photo: Okinawa taimusu) |

Two days after agreeing to the main alterations, Nakaima was shown on Okinawan media escaping his office via the back stairs in order to avoid being confronted by angry Okinawan citizens. The Nakaima who shortly afterwards was feted in Tokyo, received by a grateful Prime Minister, was unable to show his face in Okinawa.9

Onaga while still Governor-elect, had protested that Nakaima had deliberately evaded the plainly expressed will of the Okinawan people, not only by his initial agreement to reclamation in 2013 but by his last minute authorization of major changes late in 2014.10 He promised to reconsider the matter once he took office. Once in office, however, from 10 December,11 he indicated that concrete action, including possibly canceling or withdrawing the consent that Nakaima had given in December 2013, would not be taken till the New Year.

Since Onaga had declared absolute opposition to construction, and had denounced Nakaima both for his initial consent and his subsequent endorsement of major alterations, it might be thought obvious that he would simply scrap this “fifth question.” Five major groupings from the Prefectural Assembly (basically the Onaga camp) and the four major prefectural environmental organizations joined in urging him to do so.12 Controversially, however, Onaga chose otherwise,13 and the prefecture submitted its “fifth question” on 25 December 2014. Onaga’s closest advisers insisted that such a step carried no implication of endorsement of the Nakaima 2013 decision that it sought to vary.

Whether or not this is so in a strict legal sense, by doing so Onaga appeared to be entering upon negotiations with the national government in a way that implied construction proceeding.14 For Onaga to thus open his administration by taking a position at odds with his supporters in both the Prefectural Assembly and the community, without explaining his reasons, did not augur well for the Onaga new regime.

Though Onaga in 2015 might have chosen to wield a reformist broom through the prefectural offices so as to create a committed “All Okinawa” team esprit de corps, instead he seemed intent on placating and retaining the core of the old regime within the new. Onaga could hardly have been unaware of the fate of the reformist Democratic Party government of Hatoyama Yukio in 2009-2010, when Hatoyama’s staff refused to implement his policies and deliberately white-anted him, causing his government to collapse, but if so, he chose not to learn any lesson from it.

Instead, as Deputy Governors he chose two local politicians with wide bureaucratic experience but no known record of strong views on base issues or dugong – Ageda Mitsuo (aged 66) and Urasaki Isho (aged 71). These appointments were followed by an even more startling appointment, that of Henzan Hideo to set up and run the Okinawa prefecture’s Washington office. Since Henzan’s career included 30 years employment as special adviser to the US consul-general’s office in Naha, committed to serving US (rather than Okinawan, or even Japanese) interests, whatever his competence at negotiating in English and his wide circle of Washington insider contacts, it was far from clear how from 2015 he would embody “All-Okinawan” anti-base determination.

|

Mija River-entry point to Oura Bay, Camp Schwab in background (Photo: Mainichi Shimbun (helicopter), 18 August 2014.) |

Perhaps no appointments carried as much weight as those to membership of the specialist advisory body (an “Experts Committee” that Onaga set up to examine and advise him on the legality of the processes of environmental assessment and the Nakaima consent to reclamation. It was to be made up of three environmentalists and two lawyers.15 The only member to be announced at the outset was Sakurai Kunitoshi, environmental assessment specialist and former president of Okinawa University. Sakurai (see the index to this site for representative Sakurai essays translated and posted in English) had long insisted that the assessment process was deeply flawed and that therefore the Nakaima decision to license reclamation was improper and illegal. Furthermore, he saw the alterations to the original design to which the Department of Defense sought permission in September 2014 as at least equally flawed. If such a view prevailed in the Experts’ Committee, it would advise Onaga that the process followed by his predecessor had been flawed and that therefore the license to reclaim the Bay should be canceled. Even in the event of no such flaw being identified, however, based on the expression of the popular will in the November gubernatorial election, the Committee could advise revocation.16 Although nothing had been more urgent for the Onaga team during the election than stopping the works at Henoko, whether by cancelation or revocation, as of 11 January 2015, the full membership of this Committee had still not been announced and works at Henoko were about to recommence. It was of possible significance, however, that the Committee had been placed under the Prefecture’s General Affairs Department, not the Governor’s office, which normally handled civil engineering and base-related matters.17

|

Governor Onaga on Assumption of Office, 10 December 2014 (Photo: Okinawa taimusu) |

A certain ambiguity also arose at this time over Onaga’s own stance. The Onaga who in his public persona as candidate had spoken of his determination “to stop [Henoko] construction using every means at my disposal,”18 and to rid Okinawa of the Osprey,19 was shown to have adopted a much more flexible tone in confidential negotiations early in 2013. He had then put his name to a document with the mayor of Ishigaki City, Nakayama Yoshitaka, in which Nakayama stated that he did not rule out construction of a replacement base within Okinawa. It was only after this that Nakayama agreed to sign the Kempakusho agreement (Kempakusho being the fundamental statement of Okinawan demand for cancelation of Henoko and removal of the MV-22 Osprey aircraft from Okinawa).20 Once in office, Onaga did not deny the existence of this document but dismissed it as meaningless.21 It was of course possible that the Onaga of January 2013 was still in the process of clarifying what later became the fully-fledged “All Okinawa” agenda, but nevertheless his feeble denial on this matter weakened two core claims: that the Kempakusho had been unequivocal in ruling out Futenma replacement within the prefecture and that it had been endorsed by all 41 local government heads.22 This affair also left a certain shadow over Onaga.

There was also a subtle shift in tone to the Onaga message. Once in office, the campaign terms “revocation” and “cancellation” were no longer to be heard.23 Onaga suggested that cancelation might not be necessary because he might be able to persuade the Abe government to stop construction.24 This circumspect Onaga sounded very different to the Onaga who just before the election had stood on the beach at Henoko and declared that he would “absolutely smash” (zettai ni soshi) the base project. Onaga even said, in response to a question in the Prefectural Assembly, that it might not be possible to fulfill his pledges within his four-year term.25 But if, indeed, that were so, it would mean that his term of office had been a failure and that he had been unable to stop construction and save Oura Bay.

As for the suggestion that he might be able to persuade Abe to change his mind, this is a highly unlikely prospect given that Abe and his government have been utterly uncompromising, and have repeatedly assured president Obama that the base would be built and handed over on time.26 Those who supported Onaga’s campaign and his pledge to “do everything in his power” to stop Henoko construction had assumed that the first step would be a formal statement of cancellation or revocation. Probably few if any of them imagined that the problem might be left unresolved for four more years, or that Onaga might simply appeal to Prime Minister Abe.

On 18 December 2014, Onaga paid a courtesy visit to Lt. General John Wissler, commander of US Marine Corps Japan, to introduce himself and declare (according to his own account) that his election signified “the will of the Okinawan people to oppose construction of a new base.”27 A few days later, (24-26 December) he visited Tokyo to present his credentials and establish contact with the Abe government. However, Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga had already declared that the base issue was “settled” and there was therefore nothing to discuss. Major figures (Prime Minister, Cabinet Secretary, Foreign Minister) refused to see him (in marked contrast with their warm greetings for his predecessor earlier in the month). Suga said bluntly, “I have no intention to meet him during [the remainder of] this year.”28 The contrast was sharp between December 2014, when Onaga sat cooling his heels in a Tokyo hotel while the top figures of government refused to meet him, even to exchange name cards, and December 2013, when Nakaima had secreted himself in a Tokyo hospital, conspicuous in a wheelchair that he seems to have not needed either before or since, so as to pursue the secret negotiations that resulted in the deal of record budgetary allocations for Okinawa in return for his surrender on the base issue.

Again in January 2015 Onaga ventured to Tokyo for crucial budget negotiations, but again he was cold-shouldered.29 If Onaga wanted to communicate something to the government, said a senior official of the ruling LDP, then he could do so through the prefectural branch of the party, i.e., precisely those forces with whom he was at odds over fundamental policy issues.30 The government seemed to think that a severe scolding would lead Onaga to resume the proper role of Governor, as obedient supplicant. His treatment was reminiscent of that accorded Ota Masahide, governor between 1990 and 1998, who also offended Tokyo by his stubborn attempts to re-negotiate the base issue and was therefore frozen out of all contacts with the national government from February to December 1998, when he was eventually defeated at the polls. An unnamed Okinawan LDP member of the Diet probably spoke for general sentiment within the party when he (or she) was quoted as saying there was “no need to cooperate with those who have gone over to the enemy.”31 The punishment to Okinawa for electing Onaga included a 10 per cent cut in the annual budget for 2015 (to around 310 billion yen),32 and the almost certain deletion of the main projected infrastructural item – construction of a north-south railway on Okinawa Island.

3. The Outlook for 2015

One little remarked feature of the December 2014 general (lower house) national election was that the Abe who swept all before him to achieve a large majority elsewhere in the country was rejected, decisively, in Okinawa. There, the issue was not “Abenomics” or monetary or fiscal policy but democracy, justice, the fate of the country. Okinawans insisted on the constitutionally guaranteed sovereignty of the people and their right to say No to projects conceived without concern for their interests or wishes. Once again, they sent to Tokyo the same message they had sent repeatedly and in innumerable ways over 17 years: Futenma Marine base should indeed be returned as was then promised, but without any substitute base being constructed in Okinawa; enough is enough, we will tolerate no more.

As Onaga considered his policy options as the embodiment of this sentiment, he was bound to face conflicting advice from “All Okinawa” (or “new regime”) elements in civil society and in environmental and business groups who had elected him on the one hand and residual elements of the “old regime,” especially those still entrenched in the prefectural bureaucracy and who had been central to the Nakaima project, on the other. Some key appointments looked to be favoring the latter and, as noted above, on the “Fifth Question” it was their advice that he chose to follow. The Experts Committee is of course crucial. But, even if in due course it advises Onaga to revoke or cancel the Nakaima reclamation license that would not necessarily be decisive because Onaga has said only that he will give serious attention to its recommendations, not that he will necessarily implement them.

Yet it is even unclear that any such deliberative process is necessary. The “Reclamation of Publicly Owned Water Surfaces Act” (Koyu suimen umetateho, 1921) which specifies that reclamation may only be permitted (under Article 4) if due consideration has been paid to conservation, whereas this environmental impact assessment process has been widely declared “the worst EIA in the history of Japanese EIA.”33 And even Governor Nakaima, though he eventually signed off on it, declared that construction would “cause tremendous problems in terms of environmental conservation” and that “even with the conservation measures in the EIA, the conservation of the livelihood of local people and of the environment in the area affected is impossible.”34

As Onaga assumed office, Okinawa faced the bleak prospect of the irresistible force of “All-Abe” or “All-LDP” Japan meeting the immovable object of “All-Okinawa” without obvious prospect of compromise, a situation without precedent in Japanese history. Onaga seems to have begun his administration ruling out radical change in his own office and thinking or hoping for compromise so as to avoid severance of relations with Tokyo, appealing, so to speak, to Abe’s “better nature.” He was met, however, with crude attempts to browbeat him into submission. Nearly two months into the Onaga era, his gubernatorial home page had yet to articulate its demands of the national government or to post its policy.35

Simultaneously with the establishment of the specialist “experts” panel, the Onaga administration’s mass support organ (established in July 2014), the “All Okinawa Conference to Implement the Kenpakusho and Open the Future,” began drawing up plans to press the Okinawan cause to all 46 Japanese prefectures, the US government and the United Nations.36 Yet the grim fact was that it needed above all to open a line of communication to the national government in Tokyo, where crucial decisions were being taken without consultation and plainly contra to the wishes of the Okinawan people.

For Abe, construction of the Henoko base is a core national policy, fundamental to the relationship between Japan and the United States, whereas Onaga is committed to “employ all resources at my disposal” to stop it. Likewise, not only is the Abe government determined to support the deployment of Osprey MV 22 aircraft to Okinawa, but it considers equipping the Self-Defense Forces with them, whereas Onaga has pledged to have them withdrawn from Okinawa (which also means, implicitly, stopping the construction of “Osprey pads” in the northern Okinawa forests designed to accommodate them). The Abe government is also committed to the deployment of Japanese Self-Defense Forces into the frontier islands, including Yonaguni, and only after a long and bitter struggle within that island to demand the right to a say in its own future was agreement reached early in 2015 to canvas island opinion by conduct of a plebiscite, to take place on 22 February.37

So complex and substantial is the challenge in trying to weave a credible politics out of the principle of “All Okinawa,” and so impossible of quick or simple resolution, that the wisest immediate measure might be to call for the interim measure of a moratorium, cooling-off period, of at least three months, during which works at Henoko, Takae and Yonaguni are suspended, Okinawa draws up its plans and enters intensive negotiations with the governments of Japan and the United States, the Experts Panel conducts its hearings and presents its report, and the people of Yonaguni have their long-delayed say.

In an insightful 2014 year-end essay, the Okinawa taimusu‘s Washington correspondent, Heianna Sumiyo, suggested that Okinawa needed to do three things: first, draw up its plan for cancelation of the reclamation license, second, have Okinawan specialists draw up comprehensive, concrete plans, addressing military, diplomatic, environmental and legal aspects of a Futenma reversion not dependent on construction of a Henoko base (to be further developed in consultation with a major American think-tank such as the Rand Corporation), and third, set up a high-level Okinawa – US advisory or consultative Committee, headed by US Ambassador Caroline Kennedy and Governor Onaga. 38 Anticipating resumption of Henoko works (and of clashes between Abe’s state forces and Okinawa’s citizens) from 15 January 2015, she also ominously recalled the history of the American civil rights movement and urged Governor Onaga to write as a matter of urgency to President Obama to ask him to intervene before blood was shed, to ensure that the civil rights of Okinawans be respected.39

Despite the hesitation and ambiguities of his early months in office, Onaga had begun and ended his campaign for the governorship with the powerful gesture of visiting the anti-base activists on the Henoko front lines and declaring solidarity with them. It was unthinkable that he would ever renege on such a solemn pledge. As he works to weave a credible politics out of the general “All-Okinawa” principle, he must now be considering his options for response when prefectural riot police are deployed to crush those protesters whose cause he shares, or when he is confronted (a strong probability in the medium term) with court orders issued at the behest of the national government demanding compliance with government directives and carrying the threat of possible jail if he then stands firm on “All-Okinawa” and against “All-Abe” policies.

The problem with Onaga’s reiteration of the mantra “identity has precedence over ideology” is that politicians, and indeed humans, all possess multiple identities. In Onaga’s case being Okinawan is one, but having been a lifelong (to 2014) member of the Liberal Democratic Party is another, one he shares with Prime Minister Abe. Abe and his government plainly now hope that, in this contest between identities, Onaga’s political identity as a conservative would reassert itself over his ethnic or cultural identity as Okinawan. Onaga will be torn between these two poles in the months ahead and the solidarity he has declared with Okinawan protesters will be sorely tested.

Gavan McCormack is emeritus professor of Australian National University, editor of The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, author of many books and articles, including at this site (see index). His most recent books are: Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States (with Satoko Oka Norimatsu), Rowman and Littlefield, 2012, Japanese, Korean and Chinese editions from Horitsu Bunkasha (Kyoto, 2013), Changbi (Seoul, 2014) and SSAP (Beijing, 2015), and Tenkanki no Nihon e – ‘pakkusu amerikana’ ka ‘pakkusu ajia’ ka (with John W. Dower), NHK Bukkusu, 2014 (in Japanese).

The author acknowledges with gratitude the critical comments of Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Douglas Lummis and Mark Selden.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack,”Storm Ahead: Okinawa’s Outlook for 2015″, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 2, No. 3, January 12, 2015.

Related articles

Gavan McCormack (introduced and commented), “Okinawa Facing a Long, Hot Summer,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 23, No. 1, June 9, 2014.

Hideki Yoshikawa, “Urgent Situation at Okinawa’s Henoko and Oura Bay: Base Construction Started on Camp Schwab,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, July 8, 2014.

Gavan McCormack and Urashima Etsuko, “Okinawa’s “Darkest Year”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 33, No. 4, July 28, 2014.

Hideki Yoshikawa, “An Appeal from Okinawa to the US Congress: Futenma Marine Base Relocation and its Environmental Impact: U.S. Responsibility”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 39, No. 4, September 29, 2014.

Gavan McCormack, “The End of the Postwar? The Abe Government, Okinawa, and Yonaguni Island”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 49, No. 3, December 8, 2014.

Notes

1 All four defeated LDP candidates, however, were then returned to Diet seats under the proportional representation “bloc” system, as part of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) slate for the Kyushu-Okinawa region.

2 “Henoko asesu jokoku kikyaku, saikosei, jumin no shicho mitomezu,” Okinawa taimusu, 12 December 2014.

3 Yamaguchi Masanori, “Media ga hojinai Okinawa,” Shukan kinyobi, 13 July 2013, p. 58. For the background to the Takae struggle, Gavan McCormack and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2012, pp. 168-172.

4 “Takae heripaddo, toshiake kogi haijo e, Bei ga rosokutai kanri,” Okinawa taimusu, 31 December 2014.

5 “GOJ applies to change Henoko construction: OPG to approve next month,” Ryukyu shimpo, 4 September 2014.

6 “Boeikyoku, Henoko ni kanpeki no keikaku,” Ryukyu shimpo, 21 November 2014.

7 “Suiro henko torisage Nakaima shi wa handan shikaku nashi,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 29 November 2014.

8 “Henoko koho henko, ken ga boeikyoku ni 5 ji shitsumon no hoshin,” Ryukyu shimpo, 21 December 2014.

9 “‘Mendan moshiire fuhatsu’ seifu wa Okinawa no koe o kike,” editorial, Okinawa taimusu, 27 December 2014. Also “Chiji to no kaidan kyohi kenmin to no taiwa tozasu no ka,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 28 December 2014.

10 “Henoko koho henko: Onaga shi ‘gatten ikanai’,” Okinawa taimusu, 6 December 2014.

11 Text of his address on assuming office at “Onaga chiji kaiken, boto hatsugen zenbun,” Ryukyu shimpo, 10 December 2014.

12 “Henoko shinsa chushi motomeru,” Okinawa taimusu, 23 December 2014.

13 He would appear to have preferred the advice given by Tome Kenichiro. Tome, as head of the prefectural Engineering and Construction Department, had been a key figure in the Nakaima administration’s reversal during the previous year.

14 “Henoko shinsa chushi motomeru,” op. cit.

15 “Henoko umetate shonin, kenshohan wa Sakurai shi ra 5 nin, toshiake hatsu kaigo,” Ryukyu shimpo, 25 December 2014. For representative Sakurai texts on the environmental implications of the Henoko project, see the Asia-Pacific Journal index. The title of one, “Japan’s Illegal Environmental Impact Assessment of the Henoko Base,” (The Asia Pacific Journal, Vol. 10, Issue 9, No 5, February 27, 2012) was characteristically forthright.

16 “”Sakurai shi ra koho, Henoko shonin kensho chimu jinsen,” Okinawa taimusu, 11 January 2015. This distinction was expected to have legal ramifications, and the Onaga administration was anticipating that whatever step it took would be subjected to judicial challenge by the government in Tokyo.

17 “Sakurai shi ra koho,” op. cit.

18 “Arayuru shuho o kushi shite, Henoko ni shin kichi wa tsukurasenai.”

19 “Futenma kichi no heisa, tekkyo, kennai isetsu dannen, Osupurei haibi tekkai o tsuyoku motomeru.”

20 “Kennai isetsu hitei sezu,” Yaeyama nippo, 3 November 2014.

21 “Hayaku mo kotai…” op. cit.

22 See full text of Kenpakusho in both Japanese and English here.

23 In his taking-office speech on December 12, he only talked of “cancellation,” and in his New Year address to Okinawa prefectural staff on January 5, he did not mention either “revocation” or “cancellation.”

24 “Shimin kensho kankyo men o jushi,” Okinawa taimusu, 18 December 2014 (see discussion in “Hayaku mo ‘kotai’ shita hatsu gikai toben, Onaga chiji ni setsumei sekinin o,” in the blog “Watashi no Okinawa/Hiroshima nikki,” 20 December 2014.

25 Ryukyu shimpo, 17 December 2014 (quoted in “Hayaku mo,” ibid.)

26 “On time,” is a very flexible concept in relation to this project. The original target date, set in 1996, was 1999 to 2002 (“within three to five years”) but by 2013 Nakaima was promising reversion of Futenma following completion of Henoko, by 2018, while the officially agreed date (settled in 2013) was “at earliest 2022.”

27 “Onaga chiji, seifu kikan nado ni Henoko hantai tsutaeru,” Okinawa taimusu, 19 December 2014.

28 “Mendan moshiire,” op. cit. Onaga had only a brief meeting with Yamaguchi Shunichi, cabinet minister responsible for Okinawan affairs.

29 “Onaga chiji, nosho osei mo mitei, jimin kenren, nittei chosei kotowaru,” Ryukyu shimpo, 7 January 2015.

30 “Okinawa chiji o reigu, jiminto kanbu ‘Nakaima ja nai kara’,” Asahi Shimbun, 9 January 2015.

31 “Mendan moshiire,” op. cit.

32 “Okinawa shinko yosan ichiwari gen, rainendo seifu, 3100 oku en de chosei,” Okinawa taimusu, 8 January 2015.

33 Shimazu Yasuo, former chair-person of the Japan Society for Impact Assessment, quoted in Hideki Yoshikawa, “An appeal from Okinawa to the US Congress,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 29 September 2014.

34 Yoshikawa, ibid.

36 The “Kempakusho o jitsugen shi mirai o hiraku shimagurumi kaigi”. See “Shimagurumi kaigi, kokuren to Bei ni yosei kettei,” Ryukyu shimpo, 24 December 2014.

37 On Yonaguni, see my earlier essay, “The End of the Postwar? The Abe Government, Okinawa, and Yonaguni Island”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 49, No. 3, December 8, 2014.

38 Heianna Sumiyo, “Omoikaze – Washinton hikiyosete,” Okinawa taimusu, 30 December 2014.

39 Heianna Sumiyo, “Omoikaze – Henoko, kogi no jiyu o,” Okinawa taimusu, 9 January 2015.