|

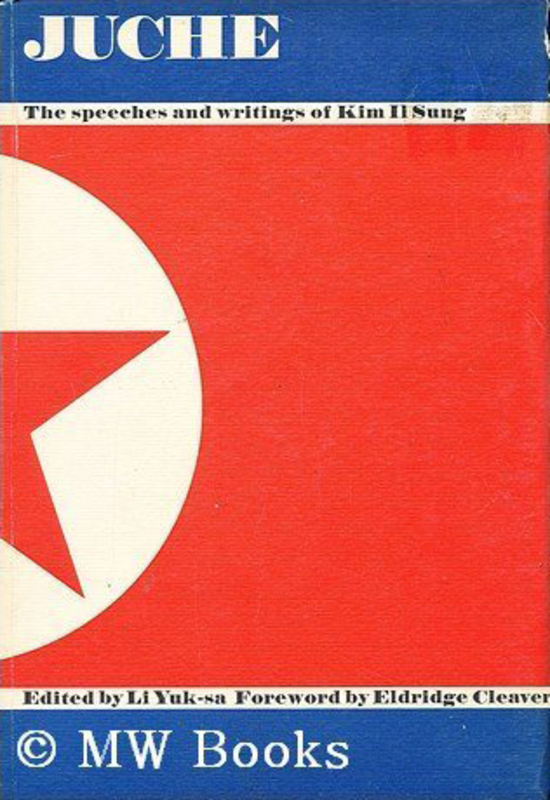

Kim Il Sung, Juche. BPP leader Eldridge Cleaver wrote the introduction for this book, which is now featured in the international friendship museum in North Korea. |

Abstract

In 1969, the Black Panther Party (BPP) established a relationship with the North Korean leadership that was based upon the principle of self-reliance (under the rubric of the Juche ideology), the transnational goal of Third World revolution, and a mutual antagonism toward American intervention around the world. Although the U.S. government forbade its citizens from travelling to North Korea, BPP leader Eldridge Cleaver along with other Panthers bypassed travel restrictions and visited North Korea to join anti-imperialist journalist conferences in 1969 and 1970. In North Korea, officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), the Panthers found a new ideology and a government that was critical of the U.S. government. The Panthers established an alliance with North Korean leaders who they recognized as an independent force within the world communist movement. They believed that the “Black colony” inside the United States could learn from the DPRK’s self-reliant stance in political, economic, and cultural matters. This study adds to recent scholarship on the global influence of the BPP and opens a new field of inquiry, as the BPP-North Korean relationship has not been analyzed in-depth.

Introduction

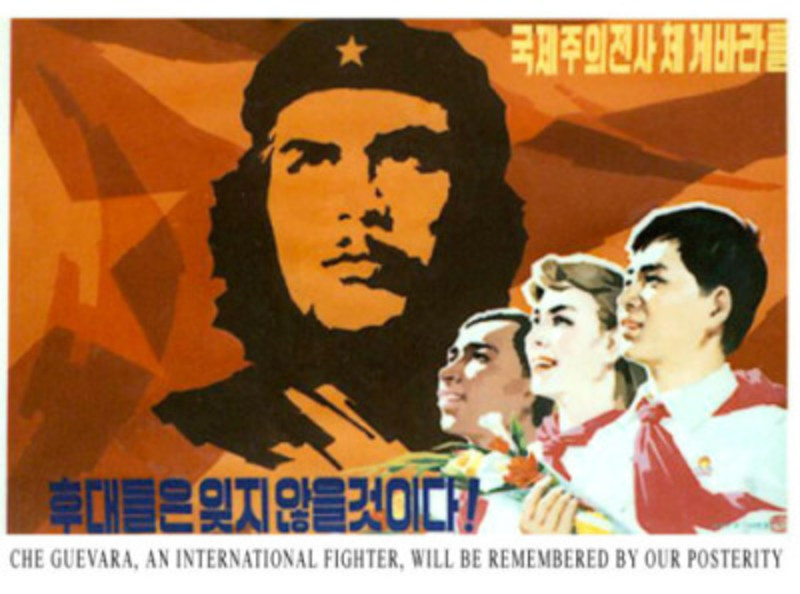

While the Cold War is commonly defined as an ideological war between the forces of capitalism and communism, frequently ignored within this Manichean view of the conflict are agents from the Third World.1 As historian Vijay Prashad asserts, the Third World was not a place but a project that called for economic development, nonalignment, and an end to colonialism.2 In the late 1960s, political radicalism inside the United States had a distinctive Third World dimension. Anti-colonial revolutions in Asia, Africa, and Latin America captivated U.S. radicals while the American role in the Vietnam War enraged them. The iconic image of the Argentine Marxist-Leninist revolutionary Che Guevara adorned the shirts of young radicals while the chant, “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, Viet Cong is going to win,” could be heard across many college campuses. The late 1960s to early 1970s represented the peak of Third World solidarity inside the United States and some radicals looked to Asia, Africa, and Latin America as an alternative to U.S. and Soviet world dominance.

|

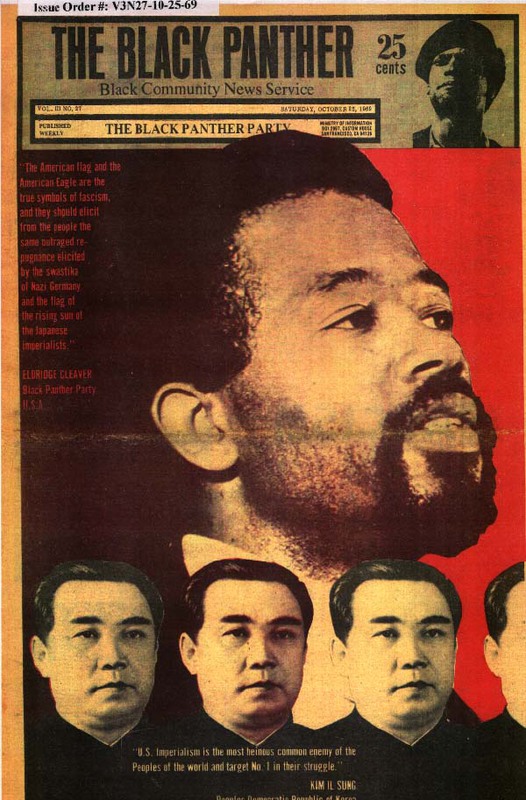

Eldridge Cleaver and Kim Il Sung on the cover of The Black Panther. |

The Black Panther Party was an important player in the ranks of this newly formed Third World-oriented American left and depicted the struggle for black self-determination as part of this global project. BPP member Kathleen Cleaver explains, “From its inception, the BPP saw the conditions of blacks within an international context, for it was the same racist imperialism that people in Africa, Asia, and Latin America were fighting against that was victimizing blacks in the United States.”3 The Panthers considered urban Black America a part of the Third World as many of these communities struggled for the same basic freedoms and resources as people in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.4 The Panthers also looked to prominent Third World figures such as Frantz Fanon, Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, and North Korean leader Kim Il Sung for revolutionary guidance. In 1969, the BPP established its international sector and reached out to many Third World nations for support. In particular, the BPP identified revolutionary Asia as a powerful antithesis to the racist and capitalist West.

During the Vietnam War era, many American radicals deemed the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong the primary force of resistance to U.S. imperialism. They were the anti-colonial freedom fighters with which they identified.5 Cuba, with its geographic proximity to the U.S and reputation as a fierce critic of the U.S. and a revolutionary bastion in the Western hemisphere, also attracted many American radicals. Above all, the People’s Republic of China and Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution captivated American radicals in the late 1960s and early 1970s. As a nation that offered an alternative brand of revolution, China’s radical take on Marxist-Leninist theory and solidarity with the black freedom struggle reverberated in the American radical community. Mao’s writings, including The Little Red Book, became the preferred revolutionary doctrine for many radicals.6 In contrast to Vietnam, China, and Cuba, North Korea received relatively little attention in U.S. radical circles in the late 1960s. The Panthers uniquely forged a close alliance with North Korea, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The BPP’s Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver “discovered” Kim Il Sung and North Korean communism after a 1969 trip to Pyongyang for an anti-imperialist journalist conference.7 Cleaver claimed that the “Motherland of Marxism-Leninism in our era” was the DPRK.8

|

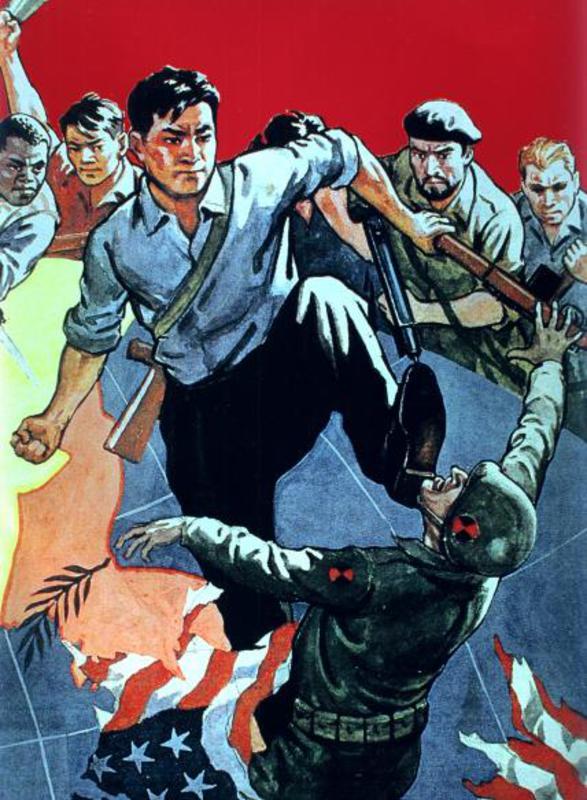

North Korean poster championing Juche as an ideology for revolutionaries of all races and nationalities. |

Eldridge Cleaver was particularly drawn to the North Korean leadership’s adaptation of Marxism-Leninism in the form of the Juche ideology (generally defined as self-reliance), the country’s economic success in the 1960s, and its opposition to U.S. imperialism around the world, a position honed in the Korean War.9 Although Huey Newton was arguably the most important leader of the BPP, Black Power scholar Peniel Joseph argues that the Panthers “would reflect Cleaver’s vision as much as, if not more than Newton’s.”10 After his return from North Korea, Cleaver spread the news of his “discovery” within the BPP chapter in Oakland, California and its international section, based in Algiers, Algeria. Cleaver was the editor of the BPP’s official organ, The Black Panther, which featured numerous articles on “the People’s Korea” and Kim Il Sung after his 1969 trip.11 With Cleaver as the driving force of this alliance, the BPP depicted the DPRK as a Third World model of modernity and autonomy as well as a “socialist paradise” that America could one day aspire to become after revolution.12 Eldridge Cleaver would often use the Chinese proverb – “the enemy of your enemy is your friend” – to describe the BPP’s alliance with the North Korean leadership and their mutual criticisms of U.S. imperialism.13

Cleaver and the Panthers who supported his vision were not pawns of the North Korean regime but calculating revolutionaries who viewed the alliance with North Korea as a means to protest against the U.S. government and strengthen their own position both within the BPP and on the international scene.14 Throughout the Cold War, American leaders presented themselves as agents of freedom and democracy abroad. However, the BPP and other black radicals attacked the U.S. government for violating the basic human rights of African Americans. Thus, North Korea’s connection to the BPP, an organization fighting racial discrimination within the United States, exposed the hypocrisy of American democracy and challenged the notion of the United States as the leader of the “Free World.”

The BPP-North Korean relationship that Cleaver forged was predicated on strategic self-interest and a common ideological commitment to autonomy, self-reliance, and adjusting Marxism-Leninism to one’s own conditions.15 By illegally traveling to North Korea and forming an alliance with its leadership, the Panthers laid claim to being revolutionary diplomats who represented the “black colony” of the United States and directly challenged the U.S. state’s authority by usurping its exclusive right to conduct foreign affairs.16 As historian Nikhil Pal Singh argues, the BPP mimicked the policies of state power (such as policing and setting up welfare programs in poor urban black communities, and pursuing diplomatic relations with foreign governments) as a way to challenge the state’s presumed exclusive control of these activities and “the state’s own reality principle.”17 While the U.S. government has never diplomatically recognized the DPRK, the Panthers regarded and openly spoke of Pyongyang as the legitimate Korean government and South Korea as a “Yankee Colony.”

|

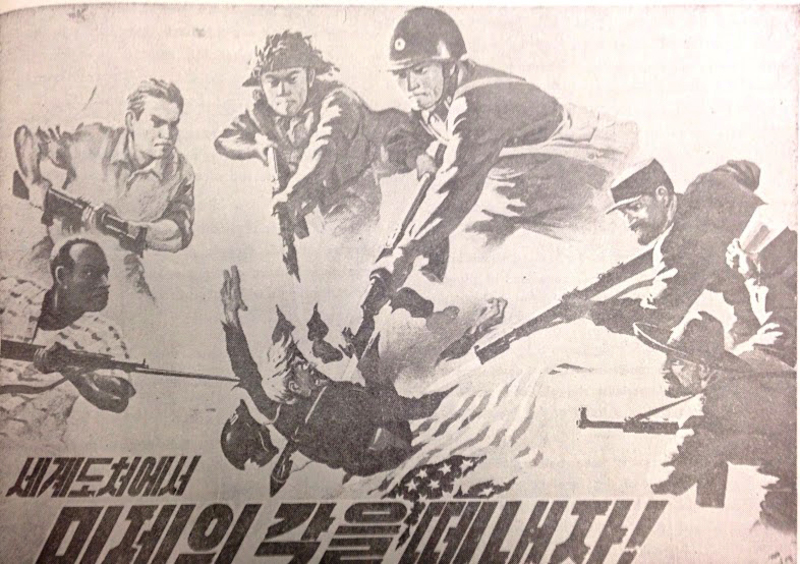

The writings of Kim Il Sung were regularly reprinted in The Black Panther newspaper. |

This is the first comprehensive account of the alliance formed between the BPP and North Korea and contributes to recent scholarship on the Third World dimensions of the BPP and the international approach of the organization.18 Scholars of the Black Power movement, such as Yohuru Williams, Peniel Joseph, Nikhil Singh, Sean Malloy, Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin, have done important work on the BPP’s efforts to become an international organization that connected issues affecting black Americans with those affecting other non-white people around the world.19 As Peniel Joseph illustrates in his book, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America, liberation struggles in the Third World captivated black radicals and obscured the national boundaries of the global struggle against white supremacy. Temporally, the war in Vietnam and anticolonial independence movements in Africa coincided with the civil rights era in America. As revolutionaries from the streets of Oakland to the jungles of Southeast Asia came face-to-face with American imperialism, the local, national, and international forces of anticolonialism and antiracism created a globalized discourse and critique of American power. Sean Malloy argues that Eldridge Cleaver was the main architect of this new discourse for the BPP, which “blended Third World symbols and rhetoric, a loosely Marxist economic analysis, and a distinctive verbal and visual style influenced by the urban argot of the ‘brothers on the block.'”20 As Yohuru Williams explains, the African American freedom struggle’s identification with Third World liberation movements, particularly the war in Vietnam, forced American military officials to take the Black Power movement seriously, as they worried about growing militancy amongst black soldiers.21 The BPP’s influence went beyond the inner cities of America as the organization inspired similar groups to emerge in Israel, New Zealand, and India.22

The Panthers also looked across the globe for revolutionary literature and ideologies. BPP members read Mao’s Little Red Book and sold copies of it on the Berkeley campus.23 After Cleaver’s enthusiasm for Maoism waned, he looked to the North Korean ideology of Juche and sought to apply it to the unique situation of African Americans in the United States. Peniel Joseph explains, “Influenced by what he viewed as the successful application of Marxist theory to indigenous movements in China and Korea, Cleaver proposed adopting a vision of class struggle that intimately considered African American experiences and the long history of racial subordination that confounded conventional Marxist rhetoric and practice.”24 Yohuru Williams would claim that the BPP “stood at the forefront of the worldwide freedom struggle against imperialism” on the basis of their reinterpretation of criminal activities in the United States as revolutionary acts and the establishment of friendly relations with revolutionary governments in the Third World, such as China and North Korea.25

This article draws upon sources such as North Korean newspapers, The Black Panther newspaper, the personal papers of Eldridge Cleaver, and his wife Kathleen Cleaver’s unpublished memoir that details her time living in the DPRK in 1970. The Black Panther newspaper is one of the primary outlets to detail the BPP-North Korean relationship. From October 1969 to January 1971, fifty-seven out of sixty-nine issues of The Black Panther featured some aspect of the BPP’s alliance with North Korea.26 Kathleen Cleaver’s memoir and Eldridge Cleaver’s diaries, letters, and handwritten and typed notes from his two trips to North Korea in 1969 and 1970 make it possible to explore the BPP-North Korean relationship in much greater depth and contextualize the BPP-North Korean alliance.27 To capture the North Korean perspective on this relationship, I primarily look to articles from The Pyongyang Times, since it contains an abundant amount of material on North Korea’s support of Third World movements and the BPP in the late 1960s to early 1970s. I also utilize materials from the Woodrow Wilson Center’s North Korea International Documentation Project (NKIDP), a digital archivethat gathers newly declassified documents onNorth Korea from its former communist allies.

North Korea and the Third World

The North Korean leadership and its propagandists, from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, represented the DPRK as “the vanguard of the Third World, anti-American rejectionist front” in addition to claiming sole governance of the entire Korean peninsula.28 The DPRK presented its struggle for reunification as “identical with the struggle of Third World peoples for independence and completely compatible with ‘proletarian internationalism.'”29 The North Korean leaders and propagandists’ portrayal of their country as a model of self-sufficiency and postcolonial development gained significant followers throughout the Third World. North Korea directly aided some of its Third World allies by providing military training and assistance. The BPP’s attraction to North Korea grew out of the DPRK leadership’s efforts to project the nation as a Third World model.

Given the present day reality of North Korea as an isolated and impoverished nation, it may seem absurd that the nation could ever have been perceived as a Third World model worthy of emulation. However, from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s, North Korea was more prosperous than South Korea and became an industrial power in the communist bloc.30 In 1965, Joan Robinson, the notable British economist, described the North’s economic success as a “Korean Miracle” and argued that South Koreans should be able to choose which part of Korea- the prosperous North or the impoverished South- they wanted to live in.31 Political scientist Victor Cha explains that, “For the first thirty years after the establishment of two Koreas, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency estimated that North Korean GNP per capita outstripped that of the South.”32

In addition to North Korea’s economic development, Third World revolutionaries were also attracted to the DPRK because the nation successfully fought off two imperialisms defeating the Japanese colonialists and then fighting the United States to a standstill in the Korean War, albeit with the critical support of China and the Soviet Union. As Eldridge Cleaver saw it, the North Koreans defeated Japan, “the monstrous, imperialist force of Asia,” and were “the first to bring the U.S. imperialists trembling to their knees.”33 Core leaders of North Korea were guerilla fighters in the 1930s who participated in the anti-Japanese resistance movement in Manchuria. The revolutionary credentials of these guerilla fighters, united around the leadership of Kim Il Sung, eventually earned them high ranking positions in North Korea alongside Soviet advisors. Two years after the official founding of North Korea in 1948, the Korean War began and the North Korean leadership experienced firsthand the power of the U.S. war machine as the United States dropped 635,000 tons of bombs and 32,557 tons of napalm in Korea during the war. In comparison, the United States dropped 503,000 tons of bombs in the whole Pacific Theater during World War II. According to Bruce Cumings, “at least 50 percent of eighteen out of the North’s twenty-two major cities were obliterated.”34 The North Korean state appealed to many Third World revolutionaries as the nation had literally risen from a guerilla struggle in the mountains of Manchuria and the ashes of the Korean War. Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary credentials and experiences confirmed his commitment to anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism, and anti-Americanism.

The North Korean leaders supported the Third World movement in symbolic and material ways in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1969, January 3-10 was proclaimed in the DPRK as “the week of international solidarity for supporting the national-liberation struggle of the Asian, African, and Latin American peoples.”35 In 1976, Kim Il Sung explained his theory of a unified Third World movement. He stated, “The newly emerging forces in Asia, Africa, and Latin America must confront the imperialists’ strategy of destruction one by one with the strategy of unity; they must not only solidly unite politically but closely cooperate economically and technologically as well.”36 The North Korean government went a step further by training two thousand guerilla fighters from twenty-five countries from the mid-1960s to the late 1980s.37 Most notably, members of the Japanese Red Army, Palestinian Liberation Organization, and the Official Irish Republican Army received training in North Korea.38 However, members of the BPP most likely did not partake in guerilla training during their visits to the DPRK.39

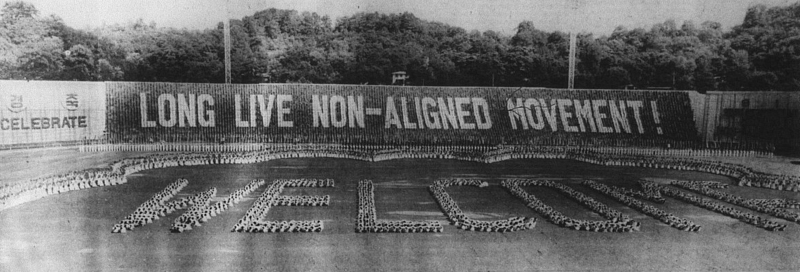

|

North Korean mass gymnastics event promoting Chajusong (political independence) and Nonalignment. |

One of the major reasons why the North Korean government supported foreign revolutionaries is “national solipsism” or the belief that the Korean peninsula is the center of the world.40 As Bruce Cumings suggests, North Korea’s “national solipsism” is similar to the Middle Kingdom worldview of ancient China.41 In funding and training Third World revolutionaries, the North Korean leadership sought to position itself as a major force for world revolution. As the North Korean state news agency stated in 1978, “The fame of the Korean Revolution is widely known to the world across the borderline of Korea; it is a beacon of hope, an example of heroism and a great inspiration for all the peoples who want liberation and political independence.”42 Thus, the North Korean leadership’s support of foreign revolutionaries helped on the domestic front as the image of peoples of all races and nationalities visiting North Korea reinforced the portrayal of the DPRK as a paradise and Kim Il Sung as a world leader. The Korea-centered worldview of the DPRK leadership was rooted in the expectation that foreigners who enjoyed its support would revere Kim Il Sung and extol the brilliance of the DPRK’s socialist system. Thus, it was a two-way street. As part of the DPRK’s “national solipsism,” its leaders believed that revolutionaries throughout the world looked to Kim Il Sung for guidance and saw the Korean Revolution as a guide to follow. During the Cultural Revolution, specifically the period 1966-1969, North Korean leaders “refuted Chinese premier Zhou Enlai’s claim that China had become the center of world revolution.”43 In 1967, Kim Il Sung ordered the Chinese government to take down propaganda at the North Korean embassy that proclaimed Mao Zedong as “the leader of the peoples of the entire world.” The Chinese government refused, explaining “that they would observe the laws of the DPRK which they like and would not observe those which they did not like.”44 While criticizing their Chinese counterparts as “dogmatists” during the Cultural Revolution, North Korean leaders branded Soviet leaders as “revisionists” due to their de-Stalinization campaign in the mid-1950s. As a 1963 article from the Rodong Sinmun, the official organ of the Korean Worker’s Party, states, “Some people [referring to the Soviet leadership] are deviating farther from the principles of Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism and being bogged deep in the mire of revisionism.”45 North Korea’s ideological independence from China and the Soviet Union attracted the Panthers and other Third World revolutionaries.

Despite championing national independence and radical self-reliance, North Korea’s postwar reconstruction and rapid industrialization rested in part on massive Soviet, Chinese and East European aid. According to Victor Cha, North Korea received over $1.65 billion in aid from the Soviet Union and China in the 1950s.46 The North Koreans welcomed this assistance from their socialist allies but were reluctant to admit that their rapid postwar reconstruction was due in part to foreign aid.47 A 1960 report from the Hungarian Embassy in North Korea to the Hungarian Foreign Ministry in Budapest explains, “Comrade Puzanov (Soviet ambassador) said that the Soviet Union does not need constant expressions of gratitude for its help but the Korean comrades are displaying too ‘modest’ behavior concerning their assistance, and they try to hush it up.”48 The Czechoslovakian ambassador to the DPRK was baffled by North Korea’s refusal to properly thank its socialist allies for their assistance in rebuilding the country. The ambassador “remarked that any bourgeois economist can easily calculate that the DPRK was unable to reach its achievements on its own, and it is similarly unable to provide the economic aid it recently offered to South Korea from its own resources.”49 In 1958, a Hungarian diplomat stated, “The Korean leaders do not appreciate sufficiently the help China gave to them during the Korean War and after the war.”50 North Korea’s supposed independence was attractive to Third World revolutionaries who appear to have been unaware of the role of Soviet-bloc aid in North Korea’s recovery and development.

|

North Korean poster showing that peoples of all races and nationalities, Third World and First World, regard Kim Il Sung and Juche ideology as a beacon of hope. |

Hoping to spur a new international order based on mutual assistance amongst small postcolonial nations, the North Korean leadership championed Third Worldism as a revolutionary path to socialist modernity in the 1970s and 1980s. During a Korean Workers’ Party meeting in 1986, Kim Il Sung emphasized Third World economic cooperation, stating that, faced with “the threat of ever-worsening hunger and disease, the developing countries ought to pool their efforts and support and cooperate with each other.” Kim later added, “If the non-aligned countries and developing countries wage a vigorous struggle together to establish a new fair international economic order, the developed countries will have to comply, in the long run, with the demands of the developing countries whether they like it or not.”51 In order to assist anti-colonial struggles, the DPRK allocated significant foreign aid and diplomatic resources to Third World countries. This placed a significant burden on North Korea’s economy. A former member of the North Korean elite, Kang Myong-do stated “that excessive aid to Third World countries had caused an actual worsening of North Korea’s already serious economic problems” in the 1980s.52

|

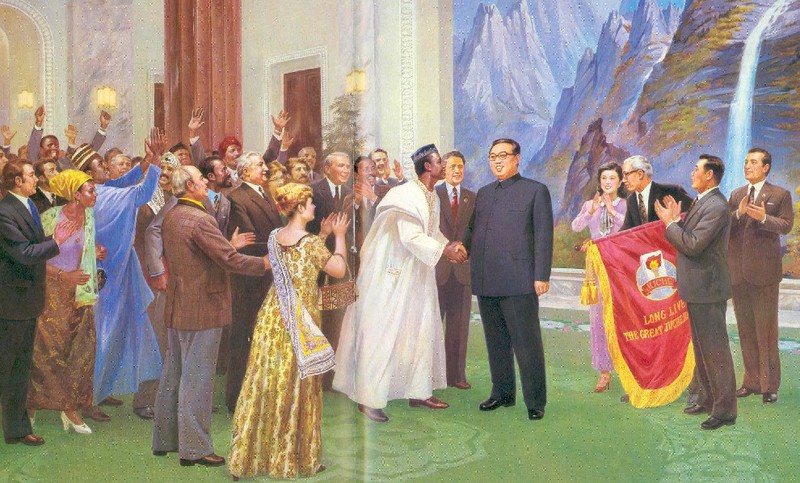

Kim Il Sung shaking hands with Third World revolutionary Che Guevara, who visited North Korea twice in the early 1960s. |

To a certain degree, the North Korean branding of their nation as a Third World model appears to have worked. Numerous Asian, African, and Latin American nations established close relations with the North and found its flexible use of Marxism-Leninism and the Juche ideology enticing. In particular, the Cuban leadership formed a close relationship with North Korea based on Third World internationalism and a commitment to supporting anti-colonial guerilla struggles around the world. Che Guevara, a leading proponent of Third Worldism, visited North Korea and met with Kim Il Sung twice in the early 1960s.53 In the fall of 1960, Guevara visited the DPRK both to see an example of “Asian socialism” and sell Cuban sugar to his Korean comrades.54 On January 6, 1961, Guevara appeared on Cuban state television and discussed his trip. He praised North Korea for its achievements in heavy industry.55 Just weeks before the Bay of Pigs invasion on April 17, 1961, Guevara spoke with the independent journalist I.F. Stone. Stone commented, “Che spoke with enthusiasm of what he had seen in his grand tour of the Soviet bloc. What impressed him most was the reconstruction of North Korea and the quality of its industrial output, here was a tiny country resurrected from the ashes of American bombardment and invasion.”56 Eighteen years later, Eldridge Cleaver’s comments on North Korea’s rapid postwar reconstruction would echo what Guevara had said. Cuban leader Fidel Castro was also enthusiastic about North Korean socialism and called Kim Il Sung “one of the most eminent, outstanding, heroic leaders of socialism.” According to a Russian archival document, Raul Castro, Fidel’s brother and second secretary of the Cuban Politburo, visited the DPRK in 1966 and emphasized the close friendship of the Cuban Communist Party and Korean Workers’ Party at a mass rally in Pyongyang. Raul Castro announced to the North Korean crowd, “If anyone wants to find out the opinion of Comrade Fidel Castro about the fundamental issues of modern times then he can ask Comrade Kim Il Sung about this.”57 North Korea’s Third World diplomacy was most noticeable in Africa. Kim Il Sung hoped to sway many newly independent countries to support the North Korean cause of reunification and its position in the United Nations.58 In October 1958, Guinea became the first sub-Saharan African nation to establish diplomatic ties with Pyongyang, and Algeria established diplomatic relations with the DPRK earlier that year.59 Other sub-Saharan African nations waited until the early 1970s to develop diplomatic relations with the DPRK, when it was possible to recognize both South Korea and North Korea.60 In the 1960s and 1970s, many African government officials and leaders who visited the DPRK praised North Korea’s postcolonial and postwar reconstruction and sought to model their nations on Kim Il Sung’s brand of socialism. An Ethiopian diplomat who visited North Korea in 1976 remarked, “The political independence and economic self-reliance, which is resolutely defended by the Korean people, is an excellent model for the socialist Ethiopian people.”61 Other delegations from Africa also hoped to learn from North Korea’s socialist development. A Mozambican delegation visited North Korea in 1978 “to take note of the Korean experience regarding the methods and paths used by the DPRK to build the socialist society.”62 In addition, Malian head of state Moussa Traore “called the achievements and experiences of the DPRK a model for the developing countries.”63 In the 1960s and 1970s many Third World leaders, particularly Africans, looked to the DPK and sought a political system that was distinct from Western and Soviet styles of rule. North Korea, a small postcolonial Third World country, with its strong leadership, a disciplined populace, rapid postwar reconstruction, and an ideology centered on self-reliance was an alluring model to many African authorities.

|

A North Korean poster championing Che Guevara. |

The North Korean leaders welcomed support from Third World peoples (which included the BPP) who denounced U.S. imperialism and proclaimed the DPRK the proper government of the “40 million Heroic Korean People.” From North Korea’s perspective, due to its competition with South Korea for votes in the United Nations and recognition as the true Korean state, the BPP was a useful ally. In the 1960s and 1970s the leaders of the DPRK and the BPP viewed themselves as vital members of a global project highlighting self-reliance and development.

Globalizing the Struggle

The BPP’s international section, led by Cleaver, embarked on a global mission to find a revolutionary ideology, that the Panthers could adapt to “the black colony” inside the United States, and reliable allies for their struggle in the United States. In so doing, the BPP’s international section directly challenged the U.S. state and the diplomatic powers that it possessed. The North Koreans treated the BPP representatives as foreign diplomats and this appealed to the Party’s sense of itself as an international organization that represented the interests of urban Black America.

Following Eldridge Cleaver’s abortive efforts to build an alliance with Fidel Castro in 1968-69, Algiers became the most important site of the BPP’s internationalist efforts, where they developed a relationship with North Korean officials.64 In her memoir, Kathleen Cleaver explains that Algiers had become a haven for revolutionaries who were forced underground.65 Algiers had also been the home of Frantz Fanon, the famous anti-colonialist revolutionary, whose work Wretched of the Earth was required reading for BPP members. Eldridge Cleaver admitted that beyond Fanon, he knew very little about Algeria before going there.66 In Algiers, Eldridge Cleaver, his wife Kathleen, and some two dozen members of the BPP established a base for BPP internationalism where they met officials from a wide range of revolutionary movements and socialist nations.67 The BPP’s international platform had caught the attention of North Korean officials. As Kathleen Cleaver explains, “Back in Algiers, the North Korean representatives became the closest associates of the Black Panther Party, for they were anxious to have a vehicle for disseminating the ideology of Kim Il Sung within the United States.”68 The Panthers reprinted many of Kim Il Sung’s speeches in their newspaper and his books became required reading in their political education classes. The BPP from the fall of 1969 through the winter of 1971 identified the teachings of Kim Il Sung, not Mao’s writings or The Little Red Book, as the revolutionary doctrine most applicable to the BPP’s situation. 69 Eldridge Cleaver explained, “After careful investigation on the international scene, it is our considered opinion that it is none other than Comrade Kim Il Sung who is brilliantly providing the most profound Marxist-Leninist analysis, strategy, and tactical method for the total destruction of imperialism and the liberation of the oppressed peoples in our time.”70 The DPRK leadership viewed the alliance with the BPP as a means to promote the works of Kim Il Sung in the United States, while the BPP gained a sense of international support for its revolutionary line.

Algiers served as a pseudo-foreign embassy of the BPP. The Panthers passed their publications to fellow revolutionaries and embassies of socialist-aligned nations. The Panthers were invited to festivals, embassy dinners, and conferences much like diplomatic officials from nations. For example, at the Pan-African Cultural Festival held in Algiers in July 1969, the Panthers met North Korea’s ambassador to Algeria who invited Eldridge Cleaver and the BPP’s Deputy Minister of Defense Byron Booth to Pyongyang for an anti-imperialist journalist conference. Cleaver and Booth agreed to come to the DPRK because they sensed “the Korean people were serious in supporting us because they wanted the Americans out.”71

The BPP-North Korean relationship revolved around the anti-imperialist journalist conferences of 1969 and 1970. On September 11, 1969, Eldridge Cleaver and Byron Booth traveled to Pyongyang for the eight-day “International Conference on Tasks of Journalism of the Whole World in their Fight against U.S. Imperialist Aggression.”72 The two Panthers were to represent “the progressive journalists of the United States of America.” The presence of two radical African Americans representing the United States surely drew the attention of the conference.73

|

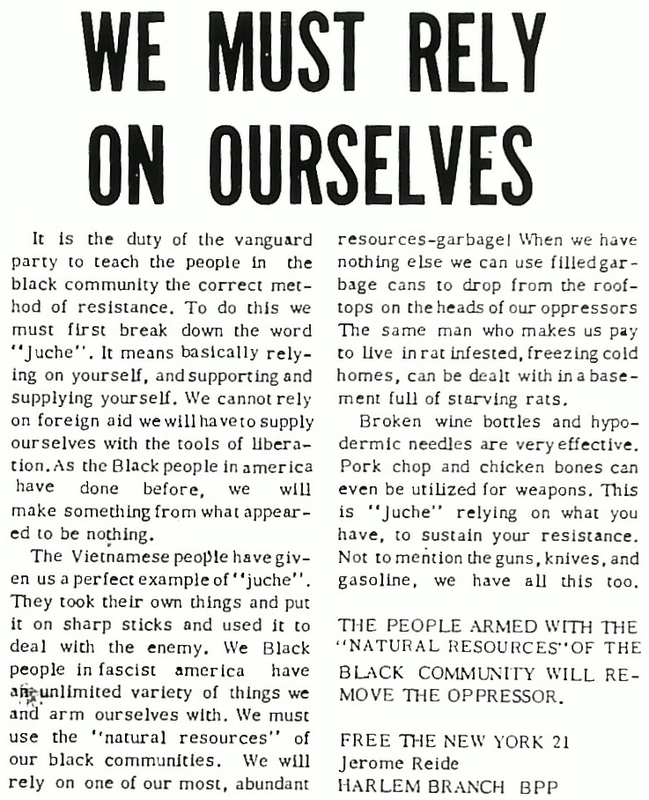

North Korean inflected paean to Juche in The Black Panther. |

Although the North Korean ambassador to China courted Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver was the BPP leader who was most disposed to the North Korean relationship.74 Cleaver was enamored with North Korea’s blending of nationalism, communism, and self-reliance into the Juche ideology, which captivated him during his 1969 trip to the DPRK. Cleaver explained that the BPP were Marxist-Leninists who adapted scientific socialism to their situation.75 North Korea took the same approach with Marxism-Leninism, which reinforced Cleaver’s idea that the Panthers should not adopt a foreign ideology indiscriminately. According to Cleaver, “Juche is carrying out the Korean Revolution. Juche for us means… to carry out our revolution.”76 Cleaver was so enthralled by the North Korean brand of communism that he and Li Yuk-Sa, who may have been a member of Chongryon (an organization of pro-DPRK ethnic Koreans living in Japan), published their own book of Kim Il Sung’s speeches and writings in 1972. Cleaver claimed that the book “must be read and understood by the American people” and much of its contents focused on explaining the Juche ideology.77 However, the meaning of Juche and its role in shaping DPRK international policy, remains contentious.

Juche, in Bruce Cumings’ view, “is really untranslatable; the closer one gets to its meaning, the more the meaning slips away.” In Cumings’ view, Juche is “closer to Neo-Confucianism than to Marxism.” 78 B.R. Myers finds Juche a “stodgy jumble of banalities” that is a smokescreen for North Korea’s real ideology: paranoid race-based nationalism.79 Bradley K. Martin explains that the broader meaning of Juche is “putting Korea first.”80 Korean studies scholar, Alzo David-West contends that “Juche is not a philosophy, but an ideology of political justification for the dictatorship of Kim Il Sung.”81 Historian Charles Armstrong observes, “Juche has been the most extreme and uncompromising expression of national political and economic sovereignty in the world.”82 Despite such differences, these scholars agree that the ideology was designed to undergird North Korean autonomy.

However, for our purposes, searching for a deeper meaning of Juche is unnecessary as the BPP was specifically attracted to the Juche ideology’s focus on self-reliance and the North Korean leadership’s adaptation of Marxism-Leninism to its unique situation as a divided post-colonial nation.83 A Black Panther article from February 1970 instructs that, “Broken wine bottles and hypodermic needles are very effective. Pork chop and chicken bones can even be utilized as weapons. This is ‘Juche‘ relying on what you have, to sustain your resistance.”84 In other words, the Panthers defined Juche as follows: “Use what you got to get what you need.”85 To the Panthers, Juche meant achieving a goal through one’s own efforts.

North Korea’s Juche ideology allowed the BPP to criticize the CPUSA for being too devoted to the Soviet line of Marxism-Leninism (peaceful coexistence) and perceived the organization as being dominated by whites, despite the presence of African Americans in key leadership positions.86 According to Eldridge Cleaver, the CPUSA challenged the BPP’s “right to adopt Marxism-Leninism – we could only do it under their good offices. So this principle of Juche, bolstered our own self assurances.” Thus, Cleaver argued that, “When a cat [referring to a revolutionary] begins to utilize Marxism-Leninism, if he’s not careful he could be made to feel that he’s stealing something or that he doesn’t really have the right to do that, and this sort of takes away the dynamic approach that you need.”87 For the BPP, even if the Juche ideology lacked any real weight on its own, it had a purpose in creating space between the organization and its domestic rivals.

Following Cleaver and Booth’s trip to the DPRK in 1969, the North Korean state-run media took a keen interest in the BPP’s activities in the United States, because they reinforced the North’s portrayal of American Imperialism as a global evil.88 On January 26, 1970, an article in The Pyongyang Times explained that the “U.S. imperialist human butchers” and “their reptile propaganda organs” were “hatching an unpardonable criminal plot to murder Bobby Seale, by making a new ‘charge’ against him.”89 According to North Korean propaganda, the U.S. government’s suppression of the BPP represented the general plight of African Americans living in a supposedly free society. On July 6, 1970, North Korean propagandists explained that the imprisonment of “hundreds” of BPP members “represents a shameless fascist barbarity against the thirty million American Negroes and an unbearable, nefarious challenge to the progressive forces of the United States and the revolutionary people the world over.”90 Later, on September 23, 1970, a North Korean international broadcast in English condemned police raids on local Panther chapters in the United States and declared that the “Korean people” will continue to support the BPP’s struggle for equality.91 Kim Il Sung even sent the BPP a telegram wishing them success in their “just struggle to abolish the cursed system of racial discrimination of the U.S. imperialists and win liberty and emancipation.”92 By covering the repression of the Panthers, which the North Korean press called “the most militant vanguard for the class and racial emancipation of the Negroes,” the North Korean state-run media was able to challenge the U.S. government’s duplicitous commitment to equality and civil rights for its citizens.

By 1970, it was clear that the BPP had won North Korean support. In late April 1970, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver, along with BPP Field Marshal Don Cox, who had recently arrived in Algiers, were invited to a formal dinner at the North Korean embassy. During the dinner, Eldridge discussed with the North Korean ambassador the details of the July 1970 anti-imperialist journalist conference. Eldridge Cleaver would be taking a delegation of U.S. radical leftists to the conference while his pregnant wife, Kathleen Cleaver, would stay in Pyongyang.

The hosting of Kathleen Cleaver indicates a shift in the North Korean leadership’s perception of the BPP. North Korean leaders regarded the BPP as a legitimate political body that represented the interests of African Americans and thus treated Kathleen Cleaver as a dignitary of an allied nation. On June 2, 1970, Kathleen and her son, Maceo, arrived in Pyongyang. Eldridge Cleaver would later join her when he arrived with the U.S. delegation for the 1970 anti-imperialist journalist conference.93 The Korean Women’s Democratic Union hosted Kathleen Cleaver and sent her to a countryside home on the outskirts of Pyongyang. The home was located at Lake Changsuwon, “where summer houses were maintained for special government guests.”94 By caring for Kathleen Cleaver, the North Korean leaders also sent a message to U.S. officials: the victims of U.S. imperialism care for each other and stand together in their common fight. This paralleled Eldridge Cleaver’s philosophy in the late 1960s that those who directly resisted U.S. imperialism were the most valuable allies. In December 1970, Cleaver pronounced, “We find our most efficacious and useful alliances are with those people who are directly confronted with the aggression by the U.S. imperialist government.”95

During the anti-imperialist journalist conferences of 1969 and 1970, the Black Panthers and their fellow travelers, led by Eldridge Cleaver, visited farms and factories exemplifying the “workers’ paradise,” that supposedly characterized the DPRK. Despite feuding with Eldridge Cleaver during the trip, Elaine Brown appreciated what she “saw was the genuine development of socialism” in North Korea.96 In 1970, the delegation “discovered a clean, efficient, industrialized state whose population was highly disciplined.”97 After a month-long stay, they left North Korea in mid-August. Members of the delegation were impressed with what they had seen.98 Demonstrating a continued interest in exposing American racial violence, the North Korean leadership offered political asylum to inmates involved in the 1971 Attica prison riots. During negotiations between prisoners and the police, the BPP told the inmates that they could live freely in four countries: North Korea, North Vietnam, Algeria, or Congo-Brazzaville.99 This reinforced North Korea’s “national solipsism.” If citizens of its most hated enemy were praising Kim Il Sung, it proved to the North Korean leadership that they were building a better type of socialism.

Nonetheless, at least some of the Panthers who traveled to the DPRK resented “the subtle brainwashing and unsubtle racism” of their North Korean hosts.100 Kim Il Sung’s personality cult made the North Koreans seem like automatons. As Kathleen Cleaver describes, “The courageous leader of ’40 million Korean people’ was given credit for every achievement in the country, making every discussion with the Korean hosts seem to American delegates like preprogrammed statements.”101 So why did the Panthers champion the DPRK as a paradise? In doing so, they depicted the DPRK as the antithesis to America, which the Party sought to expose as a racist and imperialist nation that failed to provide for its people, carried out racial discrimination across the country and abroad, and engaged in imperialistic wars.

North Korean Communism as an Alternative to American Capitalism

In the late 1960s, Oakland, California (the home of the BPP) and Pyongyang, North Korea appeared to be polar opposites. As BPP visitors to Pyongyang perceived it, poverty, crime, and gun violence plagued the streets of Oakland while free education, health care, and a stable economy and infrastructure characterized Pyongyang. The boulevards of Pyongyang were clean and appeared to be violence-free, while the streets of Oakland resembled a racially-charged war zone, a quality that had become commonplace in many American inner cities during this period. Consequently, the North Korean model, with the additional appeal that the nation confronted the American war machine, looked attractive to BPP leaders. After his 1969 trip to North Korea, Byron Booth wrote in The Black Panther that, “Being here in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is like catching glimpses of the future. It’s seeing what unity and the correct revolutionary program can create for those intent upon putting an end to oppression and the exploitation of man by man.”102 In extolling the virtues of the DPRK’s socialist system, the Panthers were not just protesting the U.S. government’s oppression of urban Black America; they were also envisioning what they hoped would occur in their own communities. The Panthers produced calculated images of North Korea and its socialist system. While integral to the examination of this relationship, the BPP’s images of life in the DPRK did not convey the reality of life for the majority of North Koreans. While many BPP members depicted the DPRK as a socialist model, they were taken on strict government approved routes that maintained the façade of a workers’ paradise.

The Panthers emphasized education and they believed they found in the North Korean educational system with its emphasis on Juche and national pride, ideas that might be applied in urban Black America. The BPP held that through education, African Americans could finally cut off the chains from their white oppressors. In their ten-point program, the BPP stated, “We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in present-day society.”103 The Panthers started literacy campaigns in inner cities in order to overcome the trend of illiterate high school graduates. North Korea’s educational revolution allured the Panthers. North Korean leaders expounded that they were the first Asian country to have eliminated illiteracy.104 When BPP member Elaine Brown visited North Korea in 1970, she reported that each child is provided with a free education “up through what we would call high school and even college education.”105 Eldridge Cleaver wrote that due to “the correct educational policy of Comrade Kim Il Sung,” one hundred universities were created and more than four million students go to school every day until the “age of labor.”106 North Korea’s educational system emphasized Korean pride, loyalty to the Kim family, and an anti-colonial worldview, aspects that most likely did not go unnoticed when Panther members visited North Korean schools. In extolling the North Korean educational system, the Panthers were not only protesting the dysfunctional educational policies in urban Black America but also imagining an alternative model of schooling that they hoped to adopt after completing the “incomplete” American revolution.

Many African Americans, who lived in inner cities in the late 1960s and 1970s, were stuck in a vicious cycle of poverty, family breakdown, and disease. Living in unhygienic, cramped conditions and eating an inadequate diet, poor African Americans were susceptible to illness. Those who became sick could not go to work. Many could not afford the medical care in the few health care facilities located in the black community. This deplorable situation inspired the BPP’s creation of programs focused on treating the nutritional and medical needs of urban Black America. The Panthers established breakfast programs for schoolchildren and clinics for treating colds and diagnosing tuberculosis, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and high blood pressure.107 The Panthers depicted health care as a universal right and stated in their ten-point platform that health care should be “completely free for all black and oppressed people.”108

Subsequently, BPP members who traveled to North Korea lauded its universal health care system, as emblematic of the benefits of socialism. According to Brown, every North Korean citizen was provided with health care in proper medical care facilities.109 In his notes from his 1970 trip to North Korea, Eldridge Cleaver explained that after Japanese colonialism, the child mortality rate had been reduced by half and the average life span increased by twenty years. He was told that a large part of North Korea’s state budget goes to health and hygiene.110 In a letter printed in The Black Panther, Kathleen Cleaver testified to the tremendous medical and childcare that she received during her pregnancy in North Korea.111 On the surface, North Korea’s health care system appeared exemplary. However, as North Korea scholar Andrei Lankov suggests, even at the best of times, the North’s health care facilities were plagued with outdated equipment, limited amounts of medicine, and over crowdedness. Contrary to what Cleaver said in 1970, the North’s health care system was also seriously underfunded.112 The BPP’s lionization of the North’s health care successes was a weapon to be used in critiquing the health disasters experienced in American ghetto communities. By portraying the DPRK’s heath care system as benevolent and successful, they were pointing out the warped priorities and failures of capitalism experienced in their communities.

The Panthers who visited the DPRK in 1969 and 1970 portrayed the North Korean countryside as vibrant and productive. A stable economy with jobs for all and an infrastructure with safe housing and electricity were portrayed as the benefits of a socialist society that placed the living standards of its people as its top priority. Following her 1970 trip to North Korea, BPP member Elaine Brown wrote that the “the entire (North Korean) countryside has electricity in all houses” and that “most of the people even in the countryside have television.” Brown contended that, “The people who live on cooperative farms actually live at a much higher living standard than the average person in the United States who would be involved in farming work, or even a worker.”113 The group of American radicals who visited Pyongyang in 1970 saw no homeless beggars, no prostitutes, and no hustlers on its streets. Gambling houses, cheap bars, rundown houses or apartment buildings were also noticeably absent.114 The Panthers represented North Korean cities as sites of socialist success. The stable but basic infrastructure of North Korean cities appealed to Eldridge Cleaver. During his 1969 trip to North Korea, Cleaver visited the industrial city of Hamhung and pronounced that it was “built for the needs of the people” while in American cities, “technology is highly advanced but serves only to exploit and murder people, to demean and destroy their humanity.”115 To Cleaver, American inner cities were symbols of the excesses of capitalism. If Cleaver and his BPP fellow travelers idealized North Korean urban and rural life, they understood well the plight of African Americans in their communities who struggled to find jobs and decent food, and who lived in rat-infested, dilapidated housing projects. In their ten-point platform, the Panthers called for decent housing and the full employment of African Americans.116 The general impoverishment that plagued urban Black America made North Korean cities seem to the visitors’ attractive models for building socialism.

The Panthers did not truly believe North Korea was “paradise,” but the rhetoric served an important purpose: it highlighted the racial discrimination and socioeconomic inequalities within the United States. At a time when inner cities of America were overwhelmed with drugs, crime, and violence, North Korea, at least on the surface, appeared to be free of these problems. Thus, North Korean communism appeared to suggest a powerful critique of American capitalism.

Conclusion

By 1971, the BPP-North Korean relationship was noticeably weakening as no Panthers traveled to North Korea.117 The primary reason for the weakening of its relations with the North Korean leadership was the growing isolation of the international section of the BPP even before the notable Cleaver-Newton “split” of 1971.118 During his time abroad, Eldridge Cleaver became estranged from the “on the ground” struggle of the BPP in the United States. As historian Sean Malloy explains, “By mid-1970, he appears to have been better versed in the nuances of Juche, Korean reunification, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict than he was with the evolving struggles on the streets of Oakland, Chicago, or Harlem.”119 While Cleaver was leading the international section of the BPP, the Panthers based in the United States were emphasizing change at the grassroots level in the black community, with programs ranging from community control of the local police force to food and health programs for the poor and dispossessed. Privately, Cleaver criticized the new emphasis on local changes on the grounds that the Panthers were working within the white man’s exploitative system.120 Meanwhile, Huey Newton questioned the direction that Cleaver was taking The Black Panther newspaper, as it began to focus more on the world communist movement than the struggle at home.121

The BPP’s radical stance, and its ability to garner support from socialist nations, above all China and North Korea, and throughout urban Black America, alarmed the FBI. J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI, branded the Panthers the country’s “most dangerous and violence-prone of all extremist groups” and focused the actions of the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) on subverting the BPP.122 Hoover’s goal was “to disrupt, discredit and destroy” the BPP.123 COINTELPRO had disastrous effects for the Panthers by fueling the growing distrust between its international section and those based in the United States when the FBI produced a series of forged letters between the two. The FBI’s infiltration program worked and Newton expelled Cleaver and the entire international section from the BPP in February 1971.124

The BPP was committed to overthrowing the American capitalist system and ending racial discrimination but the opposing personalities within the organization coupled with COINTELPRO destroyed the organization from within. In addition, as Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin argue, black radicalism lost much of its momentum in the early 1970s as the United States normalized relations with revolutionary governments, African Americans achieved greater electoral representation, better access to government employment, more employment opportunities due to affirmative action, as well as entrance to elite colleges and universities. The military draft had also been cut as Nixon wound down the war in Vietnam.125 Like other black revolutionary organizations, the Panthers lost much of its popular support in the black community due to the new socioeconomic opportunities being offered to young African Americans. In the winter of 1971, Newton informed the governments of Cuba, North Korea, and North Vietnam of Cleaver’s expulsion from the BPP. This act, together with Mao Zedong’s welcoming of “Pig Nixon” to Beijing in 1972, deepened Cleaver’s increasing resentment of the communist world.126 But by this time, the romance of China and North Korea with the BPP had cooled.

The ending of the BPP-North Korean relationship coincided not only with the internal rift within the BPP but also with the easing of tensions between the United States and China. This suggests that the North Koreans may have also been engaging in a mini-détente of their own. Richard Nixon’s visit to China ended twenty-five years of noncontact between the two sides. Perhaps the North Korean leadership sensed that the world communist movement was changing and that an alliance with the BPP hurt its ability to gain American support for ending the Korean War and moving toward Korean reunification. According to an East German diplomatic wire, the DPRK leadership supported China’s hosting of Nixon because he “would not arrive in Beijing as a victor but as a defeated.” In addition, the Chinese leadership agreed to bring up the “Korean question” in talks with the U.S. president.127 Todor Zhivkov, leader of the Bulgarian Communist Party, visited North Korea in 1973 and explained to Kim Il Sung that peaceful coexistence with the United States was a “class, internationalist policy.” After official talks, Kim Il Sung told Zhivkov that he supported peaceful coexistence with the West.128 Thus, it may not have been a one-sided breakup as Cleaver’s notes suggest. The North Korean leaders may have also sought to part ways with the BPP and the Newton-Cleaver split provided the perfect opportunity for doing so. The changing dynamics of the Cold War may have hastened the dissolution of the BPP-North Korean relationship. By 1972, the international section, based in Algiers, had practically dissolved with many members having returned to the United States and some having fled to other African nations. Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver moved to France in January 1973 and returned to the United States in 1975.129 Upon his return from exile, Eldridge Cleaver transformed from staunch Marxist-Leninist to an evangelical Christian and later created his own religion called Christlam, which had a military branch called Guardians of the Sperm. Kathleen Cleaver divorced her husband in 1987. Struggling with crack cocaine addiction in his later years, Eldridge Cleaver died in 1998. Kathleen Cleaver went back to school and eventually became a law professor at Yale University.130

The BPP and the North Korean leadership were drawn to one another in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Panthers were fighting to overthrow the capitalist system on their own terms. Likewise, North Korean leaders faced the continued legacy of an unfinished war, American hostility and blockade as they sought to reunify Korea under the leadership of the DPRK. The Panthers saw urban Black America as a colony that was oppressed by the racist American government while the North Korean leadership and its propagandists depicted South Korea as a U.S. colony and puppet state. The Panthers wanted the “pigs” (police) out of the inner cities of America so that black Americans could live freely, and the North Korean leadership wanted the Americans out of South Korea so that they could reunify the Korean peninsula. While the alliance was short-lived, the BPP-North Korean relationship sheds light on both the international politics of the DPRK and the internationalization of the BPP.

Benjamin R. Young is a PhD student in East Asian history, George Washington University. First and foremost, the author would like to thank his master’s thesis advisors at The College at Brockport, Meredith Roman and Takashi Nishiyama, for helping him develop this paper. The author also thanks Gregg Brazinsky, Adam Cathcart, Bruce Cumings, Christine Hong, Chuck Kraus, B.R Myers, James Person, Janet Poole, Mark Selden, Balazs Szalontai, Peter Ward, and Robert Winstanley-Chesters for reading earlier versions of this paper and offering helpful advice and constructive feedback. The author can be contacted at [email protected]and his webpage can be accessed at https://gwu.academia.edu/BenjaminRYoung

Recommended citation: Benjamin R. Young, “Juche in the United States: The Black Panther Party’s Relations with North Korea, 1969-1971”, The Asia-Pacifc Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 12, No. 2, March 30, 2015.

Related Articles

• Christine Hong, Stranger than Fiction: The Interview and U.S. Regime-Change Policy Toward North Korea

• Moe Taylor, “Only a disciplined people can build a nation:” North Korean Mass Games and Third Worldism in Guyana, 1980-1992

Notes

1 The concept of the “Third World” developed in the early 1950s and gained prominence after the Afro-Asian Conference (better known as the Bandung Conference) that took place in 1955. The two Koreas were left out of the Bandung Conference. These talks gave rise to what became known as the Third World movement. See Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: New Press, 2008), 41.

2 Prashad, The Darker Nations, xv-xvii.

3 Kathleen Cleaver, “Back to Africa: The Evolution of the International Section of the Black Panther Party (1969-1972) in The Black Panther Party (Reconsidered), ed. Charles E. Jones (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998), 216.

4 BPP leader Eldridge Cleaver considered African Americans “colonial subjects in a decentralized country, dispersed throughout the white mother country in enclaves called black communities, black ghettos.” See Eldridge Cleaver, Eldridge Cleaver: Post-Prison Writings and Speeches (New York: Random House, 1969), 140.

5 See Mary Hershberger, Traveling to Vietnam: American Peace Activists and the War (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998).

6 For works on the Chinese and Cuban allure to U.S. radicals during the 1960s, see Robin D.G. Kelley and Betsy Esch, “Black Like Mao” in Afro Asia: Revolutionary Political and Cultural Connections between African Americans and Asian Americans, eds. Fred Ho and Bill Mullen (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2008); and Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao, and Che (London: Verso, 2002).

7 Although the Panthers were not the only American radical leftists who forged ties with the DPRK, they established the strongest connection. Other American radical leftist organizations whose members traveled to North Korea during the 1960s and 1970s include the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), the Youth International Party (Yippies), the Movement for a Democratic Military, the Peace & Freedom Party, the women’s liberation movement, the San Francisco-based Red Guards, the radical magazine Ramparts, and the film collective, New York NEWSREEL. Prominent radical leftist organizations such as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the Weather Underground neither sent members to North Korea nor showed any interest in establishing relations with the North Korean government. For a fascinating look at a short-lived Pyongyang-funded leftist organization in New York City, see Brandon Gauthier, “The American-Korean Friendship and Information Center and North Korean Public Diplomacy, 1971-1976,” Yonsei Journal of International Studies vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2014), 151-162.

8 Eldridge Cleaver’s Typed Notes on Korea,” September 28 1969, Texas A&M University, Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, The Eldridge Cleaver Collection, 1959-1981.

9 The Korean War entered a period of armistice in 1953, but no peace treaty was signed. For recent scholarship on North Korean ideology, see Charles Armstrong, “The Role and Influence of Ideology,” in North Korea in Transition: Politics, Economy, and Society, eds. Kyung-Ae Park and Scott Snyder (Plymouth, UK: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2013); Rudiger Frank, “Socialist Neoconservatism and North Korean Foreign Policy” in New Challenges of North Korean Foreign Policy, ed. Kyung-Ae Park (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010); B.R. Myers, The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing, 2010); and Jae-Jung Suh, ed., Origins of North Korea’s Juche: Colonialism, War, and Development (Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2013).

10 Peniel Joseph, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2006), 178.

11 Cleaver gained fame as a writer due to his controversial book, Soul on Ice. The book, published in 1968, was comprised of writings from his time at Folsom State Prison. In the book, Cleaver admits to raping black women as a “practice run” before moving on to raping white women. He also launches homophobic remarks at James Baldwin, a prominent African-American novelist and poet. However, Soul on Ice also tells of Cleaver’s transformation from petty marijuana dealer in his youth to a devoted Marxist-Leninist who believed that communism was the only way to eradicate racism around the world. See Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (New York: Random House, Inc., 1968).

12 In the 1960s and 1970s, North Korea supported many Third World revolutionaries fighting for independence. For a complete analysis, see Joseph Bermudez, Terrorism: The North Korean Connection (New York: Taylor & Francis, 1990).

13 Kathleen Cleaver, “Memories of Love and War” (Unpublished Memoir, 2011), 559. I am grateful to the author for sharing her memoir with me.

14 By 1971, the Panthers were effectively split into two different camps. The Huey Newton-led camp emphasized local changes and social welfare programs, such as the free breakfast for children program, in American inner cities. Cleaver’s faction focused on ties with socialist-oriented Third World nations and advocated guerilla warfare on the streets of white America, or as Cleaver called it “Babylon,” in order to defeat the white bourgeois power structure. See Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), 218-239; and Sean Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon: Eldridge Cleaver’s Cold War,” Diplomatic History 37, no. 3 (2013): 538-571.

15 I adopt Martin Seliger’s arguments that politics and ideology are inseparable and that ideology is “a set of ideas by which men posit, explain, and justify the ends and means of organized social action, irrespective of whether such action aims to preserve, amend, uproot, or rebuild a given social order.” See Martin Seliger, Ideology and Politics (London: Allen and Unwin, 1976), 14.

16 Nihil Pal Singh, “The Black Panthers and the ‘Undeveloped Country’ of the Left,” in The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, ed. Charles E. Jones (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1998), 57-108. In the BPP’s ten-point platform, it refers to Black America as a “black colony” and to African Americans as “black colonial subjects” who will determine “the will of black people as to their national destiny.” See Huey Newton, Revolutionary Suicide (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1973), 122-123. BPP co-founders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale also claimed “that the black community in America constituted an internal colony that suffered from cultural destruction, white economic exploitation and racial oppression by an occupying white police force.” See Michael L. Clemons and Charles E. Jones, “Global Solidarity: The Black Panther Party in the International Arena,” New Political Science 21, no. 2 (1999), 189.

17 Singh, “The Black Panthers and the ‘Undeveloped Country’ of the Left,” 88.

18 For scholarly works that have briefly noted the BPP’s connection to North Korea in the late 1960s and early 1970s, see Charles K. Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak: North Korea and the Modern World (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013), 177; Curtis Austin, “The Black Panthers and the Vietnam War,” in America and the Vietnam War: Re-Examining the Culture and History of a Generation, ed. Andrew Wiest, Mary Kathryn Barbier, and Glenn Robins (New York: Routledge, 2010); Floyd W. Hayes, III, and Francis A. Kiene, III, “‘All Power to the People’: The Political Thought of Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party,” in The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, 157-176; G. Louis Heath, Off The Pigs: The History and Literature of the Black Panther Party, (Matuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press, 1976); Sean Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon: Eldridge Cleaver’s Cold War,” Diplomatic History 37, no. 3 (2013): 538-571; Frank J. Rafalko, MH/CHAOS: The CIA’s Campaign Against the Radical New Left and the Black Panthers(Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011); and Jennifer B. Smith, An International History of the Black Panther Party (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc.,1999).

19 For important, recent scholarship on the global approach of the BPP, see Yohuru Williams, “‘They’ve lynched our savior, Lumumba in the old fashion Southern style’: The Conscious Internationalism of American Black Nationalism,” in Black Beyond Borders, ed. Nico Slate (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 147-167; Yohuru Williams, “American Exported Black Nationalism: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, and the Worldwide Freedom Struggle, 1967-1972,” Negro History Bulletin 60, no. 3 (July-September 1997), 13-20; Joseph, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour; Singh, “The Black Panthers and the ‘Undeveloped Country’ of the Left,” 57-108; Sean Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon: Eldridge Cleaver’s Cold War,” Diplomatic History 37, no. 3 (2013): 538-571; Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013).

20 Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon,” 552.

21 Yohuru Williams, “‘They’ve lynched our savior, Lumumba in the old fashion Southern style’: The Conscious Internationalism of American Black Nationalism,” in Black Beyond Borders, 165.

22 Oz Frankel, “The Black Panthers of Israel and the Politics of the Radical Analogy,” in Black Beyond Borders, 81-106; Robbie Shilliam, “The Polynesian Panthers and the Black Power Gang: Surviving Racism and Colonialism in Aotearoa New Zealand,” in Black Beyond Borders, 107-126; Nico Slate, “The Dalit Panthers: Race, Caste, and Black Power in India,” in Black Beyond Borders, 127- 143.

23 Joseph, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour, 176.

24 Joseph, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour, 211.

25 Williams, “American Exported Black Nationalism,” Negro History Bulletin, 19.

26 The Black Panther was first published in April 1967. Early on, “the newspaper’s circulation was still quite limited” but by 1970, “the paper’s circulation grew to an estimated 139,000 copies per week.” See Ward Churchill, “‘To Disrupt, Discredit, and Destroy’: The FBI’s Secret War against the Black Panther Party,” in Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Panthers and Their Legacy, ed. Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficas (New York: Routledge, 2001), 85-86.

27 An online digital archive of Eldridge Cleaver’s personal papers regarding his travels to the DPRK and an e-dossier, written by the author of this piece, introducing these documents can be found at the Woodrow Wilson Center’s North Korean International Documentation Project (NKIDP) website. See Benjamin R. Young, “‘Our Common Struggle against Our Common Enemy’: North Korea and the American Radical Left,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars-North Korea International Documentation Project (NKIDP) e-Dossier no. 14, February 11, 2013.

28 Bruce Cumings, “The American Century and the Third World,” Diplomatic History 23, no. 2 (Spring 1999) , 357.

29 Charles K. Armstrong, “Socialism, Sovereignty, and the North Korean Exception,” in North Korea: Toward a Better Understanding, ed. Sonia Ryang (Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books, 2009), 45.

30 Bruce Cumings, North Korea: Another Country (New York: The New Press, 2004), viii-ix, 134-135.

31 Joan Robinson, “Korean Miracle,” Monthly Review 16, no. 8 (January 1965), 541-549.

32 Victor Cha, An Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future (New York: Harpers Collins Publishers, 2012), 24-25.

33 “1969 Statement from the U.S. People’s Anti-Imperialist Delegation to Korea,” University of California, Berkeley, The Bancroft Library, BANC MSS 91/213c, The Eldridge Cleaver Papers, 1963-1988, Carton 5, Folder 4.

34 Bruce Cumings, The Korean War: A History (New York: Random House, 2011), 159-160.

35 “Militant Solidarity with Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America,” The Pyongyang Times (January 6, 1969), 14.

36 Quote from Kim Il Sung cited in Pak In-kun, “U.S. Imperialism is the Outrageous Strangler of National Independence and Sovereign Rights,” Kulloja (December 1976), 60.

37 The training in these camps lasted from six to eighteen months, and during that time, the North Korean military taught foreign revolutionaries Korean martial arts. The foreign revolutionaries were also put through “vigorous training” such as running through the North Korean mountains at night while carrying one hundred pound sandbags. “Running, running, running” became the training slogan of these camps. See “The Trade in Troublemaking,” Time 97, no. 19 (May 10, 1971), 38.

38 On March 31, 1970, nine members of the Japanese Red Army (JRA) hijacked a Japan Air Lines plane and landed it in Pyongyang. These nine members eventually settled in a housing complex on the outskirts of Pyongyang and the North Korean government used the JRA connection to send money and arms to various Third World-oriented organizations, such as the PLO, the Baader-Meinhof group, and the Italian Red Brigades. For information on the training of PLO and JRA members, see Bermudez, Terrorism: The North Korean Connection, 102-104. For information on the training of Official Irish Republican Army members in the DPRK in the 1980s, see John Sweeney, North Korea Undercover: Inside the World’s Most Secret State (London: Transworld Publishers, 2013), 201-226.

39 Rafalko, MH/CHAOS, 175-177.

40 Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997), 414.

41 Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 414.

42 “DPRK Meeting Welcomes African Delegations,” Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) (September 14, 1978).

43 Liu Ming, “Changes and Continuities in Pyongyang’s China Policy,” in North Korea in Transition: Politics, Economy, and Society, eds. Kyung-Ae Park and Scott Snyder (Plymouth, UK: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2013), 216.

44 “Document 14: Memo of the Soviet Embassy in the DPRK,” (August 5, 1967) in Limits of the ‘Teeth and Lips’ Alliance: New Evidence on Sino-DPRK Relations, 1955-1984, Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars- NKIDP digital archive (accessed March 18, 2013).

45 “Let Us Defend the Socialist Camp,” Rodong Sinmun (October 28, 1963), 1-2.

46 Cha, An Impossible State, 112-113.

47 For more on this topic, see Balazs Szalontai, Kim Il Sung in the Khrushchev Era: Soviet-DPRK Relations and the Roots of North Korean Despotism, 1953-1964 (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2004).

48 “Report, Embassy of Hungary in North Korea in North Korea to the Hungarian Foreign Ministry,” NKIDP digital archive, December 8, 1960. (accessed April 6, 2013).

49 “Report, Embassy of Hungary in North Korea in North Korea to the Hungarian Foreign Ministry,” NKIDP Digital Archive.(accessed April 6, 2013).

50 Szalontai, Kim Il Sung in the Khrushchev Era, 131.

51 Kim Il Sung, “For the Development of the Non-Aligned Movement,” Kim Il Sung Selected Works, vol. 40 (Pyongyang, DPRK: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1995), 117-144.

52 Bradley K. Martin, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004), 137.

53 [53] Charles K. Armstrong, “Juche and North Korea’s Global Aspirations,” North Korea International Documentation Project Working Paper No. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, April 2009), 33.

54 Jon Lee Anderson, Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (New York: Grove Press, 1997), 467.

55 Anderson, Che Guevara, 473.

56 I.F. Stone, “The Legacy of Che Guevara,” Ramparts (December 1967), 21.

57 “From a June 2, 1967 Memo of the Soviet Embassy in the DPRK (1st Secretary V. Nemchinov) About Some New Factors in Korean-Cuban Relations,” (June 2, 1967) NKIDP digital archive (accessed March 9, 2015).

58 See Benjamin R. Young, “The Struggle for Legitimacy: North Korea’s Relations with Africa, 1965-1992,” British Association for Korean Studies Papers no. 16 (forthcoming, 2015).

59 Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak, 144.

60 The Sub-Saharan African nations to which I refer are Angola, Benin, Botswana, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritius, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Togo, Uganda, Upper Volta, and Zaire. See Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak, 179.

61 “Hungarian Embassy in the DPRK, Report: Visit of an Ethiopian Government Delegation in the DPRK,” (April 28, 1976) NKIDP digital archive (accessed May 10, 2013).

62 “Telegram 066.712 From the Romanian Embassy in Pyongyang to the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” (June 3, 1978), NKIDP digital archive (accessed March 9, 2015).

63 “Hungarian Embassy in the DPRK, Telegram, June 2 1976: Subject: Visit of the President of Mali in the DPRK,” (June 2, 1976), NKIDP digital archive (accessed March 9, 2015).

64 Cleaver would subsequently criticize Cuba’s adherence to the Soviet line of peaceful coexistence and denounce Cuban racism. Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon,” 558; Ray F. Herndon, “Ex-Black Panther Scores Racism in Cuba,” Chicago Defender (December 1, 1969), 2.

65 Kathleen Cleaver, Unpublished Memoir, 540.

66 Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon,” 559.

67 Malloy, “Uptight in Babylon,” 559-560.

68 Kathleen Cleaver, “Back to Africa,” in The Black Panther Party Reconsidered, 226.

69 In April 1970, the Panthers began selling a book composed of Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary thoughts. The book was titled, Let Us Embody More Thoroughly the Revolutionary Spirit of Independence, Self-Sustenance, and Self-Defense in All Fields of State Activity. In July 1970, the Panthers began selling two other books composed of Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary thoughts. One of the books was titled, Each of You Should Be Prepared to be a Match for One Hundred. The other book was a September 7, 1968 report from the anniversary celebration of the founding of the DPRK, titled, The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is the banner of freedom and independence for our people and the powerful weapon of building socialism and communism. The BPP sold these three books until January 1971. Each of these books were published by The New World Liberation Front, a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist group based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

70 Eldridge Cleaver, “Manifesto from The Land of Blood & Fire,” The Black Panther 4, no. 15 (March 15, 1970).

71 Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Fire (Waco, TX: Word Books Publisher, 1978), 147.

72 On the eve of the conference, “several North Korean organizations had sent a cablegram to the Panthers’ imprisoned chairman [Bobby Seale], condemning the ‘illegal’ imprisonment of Panther officers.” See Committee on Internal Security, House of Representatives, Gun-Barrel Politics: The Black Panther Party, 1966-1971 (Washington, D.C.: Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1971), 105.

73 Cleaver also gave a poignant speech where he insisted that revolutionaries inside America “need words [from journalists] that will make the soldiers, sailors, marines, and special forces of the U.S. imperialists turn their guns against their commanding officers; words that will persuade them to evacuate South Korea, Vietnam, and all the bases of U.S. imperialist aggression around the world.” G. Louis Heath, Off the Pigs: The History and Literature of the Black Panther Party, (Matuchen, New Jersey: The Scarecrow Press, 1976), 163.

74 In 1971, Huey Newton traveled from Oakland to China and engaged in his own solidarity campaign with socialist Asian nations. During his tour of China, he met with North Korean officials. The North Korean ambassador to China gave Newton “a sumptuous dinner and showed films of his country.” On Chinese National Day (October 1st), Newton attended a large reception in the Great Hall of the People and shared a table “with the head of Peking University, the head of the North Korean army and Comrade Chiang Ch’ing, Mao’s wife.” See Newton, Revolutionary Suicide, 325.

75 Eldridge Cleaver, “On the Ideology of the Black Panther Party,” vol. 1 A Black Panther Party Pamphlet (1969) (accessed August 15, 2013).

76 “Eldridge Cleaver’s Typed Notes on Korea,” September 28 1969, Texas A&M University, Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, The Eldridge Cleaver Collection, 1959-1981.

77 Eldridge Cleaver foreword to JUCHE!: The Speeches and Writings of Kim Il Sung, Li Yuk-Sa ed. (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1972), XII.

78 Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun, 414.

79 Myers, The Cleanest Race, 46.

80 Martin, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader, 363.

81 Alzo David-West, “Between Confucianism and Marxism-Leninism: Juche and the Case of Chong Tasan,” Korean Studies 35 (2011), 107.

82 Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak, 53.

83 North Korea’s Juche ideology was a model that the Panthers could appropriate into the Party’s discourse as the organization emphasized self-defense of the black community. In 1968, the Panthers changed their name from the BPP for Self-Defense to the BPP due to the organization’s philosophical shift from focusing primarily on gun violence to other forms of violence (unemployment, poor housing, improper education, lack of public facilities, and the inequity of the draft) that affected impoverished communities in the United States. Despite the name change, the organization maintained an emphasis on the self-defense and self-reliance of the black community. See Bridgette Baldwin, “In the Shadow of the Gun,” in In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement, eds. Jama Lazerow and Yohuru Williams (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2006), 83.

84 “We Must Rely on Ourselves,” The Black Panther 4, no. 13 (February 28, 1970).

85 Committee on Internal Security, Gun-Barrel Politics, 105.