“I do this job for the opportunity to kill the enemies of my country and also to get that boat I always wanted. . . . [W]hen engaged I will lay waste to everything around me.” – Contractor slogan.

“It’s the perfect war… everybody is making money.” – US intelligence officer in Afghanistan.

His bulging left bicep featuring a tattoo of a Panther and his right one of the Grim Reaper, Wolf Weiss was a heavy metal guitarist from Los Angeles with fifteen years’ military experience who embodied the new type of warrior for the 21st century. Styled “the Heavy Metal Mercenary” by Rolling Stone Magazine, Weiss was hired by a private contractor, Crescent Security, to drive truck convoys in Iraq and admitted to killing several Iraqis in four separate firefights. His team, the Wolverines, was known for provocative displays of force, going by the motto: “strike down thine enemies and vanquish all evil by the right hand of god, strength and honor to all who live by the code of the warrior.” In November 2004, en route to Baghdad international airport, Weiss’s vehicle was ambushed by U.S. soldiers who mistook him for an insurgent. He was shot in the head and killed. He had told Rolling Stone that “war was one of the few things in the world I can do really well…..A lot of people are calling us private armies – and that’s basically what we are. This is not a security company. This is a paramilitary force.”1

|

At the time, Weiss was one of at least 48,000 corporate soldiers working in Iraq for more than 170 private military companies (PMCs), with another 30,000 to 100,000 serving in Afghanistan at any given point during the war along with thousands more who performed menial tasks like cooking and cleaning for marginal pay.2 Though the Pentagon claims not to keep records on mercenary fatalities, over 1,000 mercenaries are estimated to have been killed in Iraq and another 2,500 in Afghanistan, including eight who worked for the CIA, with thousands more wounded.3 A 1989 UN treaty, which the U.S. did not sign, prohibits the recruitment, training, use and financing of mercenaries, or combatants motivated to take part in hostilities by private gain, with PMCs claiming exclusion on the grounds that they play a combat support role.4 This essay details the role of PMCs in America’s long Iraq War in light of a century-long history of U.S. use of mercenary and clandestine forces throughout the world. It shows the multiple ways of mercenary war as a means of concealing military intervention from public view. The Bush administration carried these practices to extreme levels, particularly in financing organizations which profit from war and hence are dedicated to its perpetuation.

Naomi Klein has commented that Iraq was more than a failed occupation, it was a “radical experiment in corporate rule.”5 Led by radical free-market ideologists, the Bush administration placed a primacy on deregulation, corporate tax cuts and privatizing state-run industry in Iraq, which was to be a shining model for the virtues of neoliberal capitalism. After Saddam’s government fell, Booz-Allen Hamilton, one of the Beltway’s biggest consulting firms, organized a conference which called for the rewriting of Iraq’s business, property and trade laws in ways conducive to foreign investment. The Bush administration ultimately tore down Iraq’s centralized, state-run economy without building anything to replace it while provoking civil war and putting in place a political system ensuring fierce regional and ethnic divisions.6

The war’s key architects believed with Erik Prince, founding CEO of Blackwater, that the privatization of war could ensure greater military efficiency while cutting out wasteful spending. Prince told a reporter that “we’re trying to do for the national security apparatus what fed-ex did for the postal service. They did many of the same services, better, faster and cheaper.”7 Upon his appointment as defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld had set about reducing the wasteful Pentagon bureaucracy and revolutionizing the U.S. armed forces by moving towards a lighter, more flexible fighting machine and harnessing private sector power on multiple fronts. He wrote in Foreign Affairs that “we must promote a more entrepreneurial approach: one that encourages people to be proactive, not reactive, and to behave less like bureaucrats and more like venture capitalists.”8 These remarks were in-line with the philosophy initially honed in Rumsfeld’s days outsourcing government functions as head of the Office of Economic Opportunity under Richard M. Nixon. They were welcomed by defense contractors and PMCs ready to cash in on the new opportunities made available by the Global War on Terror (GWOT).

The Bush administration prioritized a war economy in which defense contractors and other corporate interests finance elections to ensure the proliferation of permanent war mobilization.9 In spite of well-developed propaganda techniques in selling military interventions, antiwar attitudes crystallize, particularly when wars drag on and official claims prove hollow.10 The 1960s anti-war movements engendered a deep culture of skepticism towards militarism, known as the “Vietnam syndrome,” which made revival of the draft a risky political option even amidst the jingoistic climate that followed the 9/11 attacks. The Bush administration’s support for mercenaries was one crucial weapon in an arsenal designed to distance the war from the public that included reliance on air power and eventually drones, Special Forces operations and the training of proxy units, and media censorship epitomized by the phenomenon of embedded reporters.11

After authorizing the attack on Afghanistan, George W. Bush told Americans to carry on business as usual and to “go shopping.” The insinuation was that the same public sacrifice would not be demanded as in previous wars.12 Michael Ignatieff in Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond wrote that, “the American public and its military came away from Vietnam unwilling to shed blood in wars unconnected with essential national interests. The debacle in Vietnam brought the draft to an end and the result widened the gulf between civilian and military culture. Masculinity has slowly emancipated itself from the warrior ideal…. In a society increasingly distant from the culture of war, the rhetoric politicians use to mobilize their populations in support of the military becomes unreal and insincere. The language of patriotism is losing its appeal.”13

Much like Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush attempted to revive the triumphalist attitude towards war characteristic of the post-World War II era (what historian Tom Engelhardt has called the “victory culture”) but largely in vain. His efforts crashed and burned after he gave a speech on the USS Abraham Lincoln with a “Mission Accomplished” banner behind him weeks before an insurgency developed against the U.S. occupation and Iraq descended into bloody sectarian war.14

A blueprint for American strategy in the War on Terror was the 1959-1975 secret war in Laos, where the CIA worked with hundreds of civilian contractors who flew spotter aircraft, ran ground bases and operated radar stations in civilian clothes while raising its own private army among the Hmong to fight the pro-communist Pathet Lao.15 Another prototype was Nixon’s Vietnamization program, which transferred the fighting burden to Vietnamese soldiers trained by Green Berets and third country nationals’ recruited from among tribal minorities and U.S. allies in South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand.16 Vinnell, an L.A.-based construction company brought over by the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm with heavy investments in the defense sector, was contracted to run black operations against the “Vietcong,” as part of Operation Phoenix. A Pentagon official described Vinnell, which later won a $48 million contract to train the armed forces in Iraq, as “our own little mercenary army.”17

Civilian contractors generally played a crucial though unrecognized role in the Vietnam War, including in building and running military bases and national communication and transportation networks and training local military forces.18 After the 1968 Tet offensive, the United States could no longer rely on its own soldiers to fight. Colonel Robert Heinl reported in The Armed Forces Journal in 1971 that the military had disintegrated to a “state approaching collapse,” with “individual units drug ridden and dispirited when not near-mutinous,” avoiding or having refused combat and “murdering their officers and non-commissioned officer” through fragging, or detonating a grenade in their barracks. Following a fruitless offensive on the Dong Ap Bia Hill in the A Shau Valley, a group of veterans placed a $10,000 bounty on the head of Lieutenant Colonel Weldon Honeycutt, who had ordered the attack.19 This act testified to the breakdown in military morale which coinciding with the growth of large-scale antiwar protest forced the Nixon administration to wind down the war and necessitated the abolishing of the draft and a reliance on covert strategies that included the use of private contractors.20

After the Vietnam War ended, American strategic planners set out to keep a “light footprint” in overseas interventions, with private interests connected to the national security establishment making up for the manpower gap. When Jimmy Carter cut the CIA budget in half, ex-agency operatives formed what journalist Joseph Trento has called a “shadow CIA,” setting up private intelligence networks and procuring independent contracts with foreign governments to carry on espionage and covert operations in the service of U.S. hegemony worldwide.21 Hundreds of British and American mercenaries along with a few South Vietnamese recruited and trained by the CIA fought against liberationist forces in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and against the Cuban-backed MPLA in Angola where they were accused of torturing prisoners and massacring civilians.22 After leaving a booby trapped grenade at the site of a burned land rover with ten unidentified bodies in Mozambique, Bob Mackenzie, CIA Deputy Director Ray Cline’s son-in-law, quipped in his diary: “it’s easy to be a terrorist.”23

If the use of mercenaries reached a peak during the George W. Bush administration, they have long been part of American war making, employed particularly to carry out covert operations. Nineteenth century filibusters such as Confederate General Henry MacIver and William Walker established independent slave republics in Haiti and Nicaragua and laid the groundwork for the United States invasion of Cuba by fighting alongside Cuban rebels against Spain.24 In the Philippines, the U.S. built a native constabulary commanded by some soldiers of fortune, including Jesse Garwood, a Western gunfighter who placed bounties on the heads of nationalist insurgents.25 In 1911, the Department of State backed a coup led by Lee Christmas an African American mercenary hired by Samuel Zemurray, owner of the Cuyamel Fruit Company (later United Fruit), against Honduran president Miguel Dávila who had forced Zemurray to pay taxes and campaigned to limit the amount of land foreigners could own. Christmas was also head of the secret service of Guatemalan dictator Estrada Cabrera, a State Department favorite who “smiled benevolently on U.S. enterprise in the tropics,” and partook in efforts to overthrow Nicaraguan ruler José Santos Zelaya who worked for Central American federation and refused building of the Panama Canal.26 Mercenaries were crucial generally to the consolidation of an American informal empire in the Caribbean and the advancement of U.S. business interests there.

Throughout the Cold War, the U.S. relied on private corporations such as Civil Air Transport (CAT – later Air America) founded by General Clare Chennault and CIA-front companies to assist in clandestine operations. Following the murder of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, the CIA financed South African and Rhodesians likened by Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah to “thugs employed by the Klu Klux Klan,” to shore up the pro-western regime of Joseph Mobutu.27 After disbanding USAID’s Office of Public Safety (OPS), which trained foreign police forces, Vinnell won a $77 million contract for training and equipping the Saudi National Guard to defend oil fields. In 1979, when a rebellion rocked the kingdom, the company provided the tactical support needed by the Saudi princes to recapture the Grand Mosque at Mecca.28 Vinnell and a parent company, BDM, chaired by Frank Carlucci III, Reagan’s Defense Secretary, continued to oversee the kingdom’s internal security forces into the 21st century, with Booz Allen-Hamilton, a key government contractor in Iraq, taking control over the Saudi Marine Corps and Army Staff College and Science Application International Corporation (SAIC) developing a sophisticated intelligence and communications system for the Saudi Royal navy.29

|

Under the 1893 anti-Pinkerton law, the hiring of private quasi-military organizations by the U.S. government was outlawed, though there is ambiguity as to whether this law applied only to domestic strike breaking. In 1981, Executive Order 12333 gave U.S. intelligence agencies the right to enter into contracts with private companies for authorized intelligence purposes which need not be disclosed. This provided a basis for some of the arms smuggling operations using private airlines in the Contra war in Nicaragua.30 Backed by popular cultural portrayals like the film Rambo, Ronald Reagan was generally successful in reviving a vengeful cult of the warrior among white males who latched onto a betrayal narrative blaming liberal bureaucrats and peace activists for the American defeat in Vietnam.31 Soldier of Fortune Magazine, which ran full-page ads for mercenaries and promoted the cause of anticommunist “freedom fighters,” gained wide circulation at this time. Its editor Robert K. Brown, a Captain in Vietnam who had a banner in his office that read “kill ‘em all, let God sort ‘em out,” wrote about his exploits fighting alongside death squad operators in El Salvador. Contributor James “Bo” Gritz raised a private army to rescue alleged POWs in Laos (none were ever found) while reviving contacts with remnants of the CIAs clandestine army.32 As journalist James W. Gibson observed, Soldier of Fortune magazine and the right-wing militia movement that it inspired embodied a violent strain in American culture and a yearning for heroes and male bonding rites amidst the decline in respect for public authority after Vietnam.33 The young men who gravitated to its ideals would fight as corporate warriors in the GWOT.

|

Air America Bell 205 helicopter leaving a Hmong fire support base in the Laotian Plain of Jars, c. 1969 |

From 1994 to 2002, the Pentagon signed more than 3,000 contracts with U.S. based firms valued at $300 billion.34 Military Professional Resources Inc. (MPRI) one of the largest companies operating in Iraq was given the contract for ROTC training in almost 200 universities. The company’s Virginia headquarters displayed a plaque which read: “War is an ugly thing but not the ugliest of things. The decayed and degraded state of moral and patriotic feeling which thinks that nothing is worth war is much worse.”35 Harry E. Soyster, head of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) when it used private arms dealers to equip the Afghan mujahidin and Nicaraguan Contras, bragged, “we’ve got more Generals per square foot here than in the Pentagon.”36 MPRI trained the security forces of numerous authoritarian regimes, including Equatorial Guinea in a contract that was approved by the State Department after dictator Teodoro Obiang granted concessions for off-shore drilling to Exxon-Mobil. It also trained Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and Ugandan fighters linked to major human rights abuses in Congo. A senior embassy staffer described the program there as “killers training killers.”37

In Bosnia, MPRI won a contract to train and modernize the Croatian army, overseeing the rooting out of “communist dead wood”, which set the groundwork for ethnic cleansing by helping to create an ethnically pure army (many of those purged had served in the Yugoslavian integrated force). The State Department used MPRI to provide a secret conduit of heavy weapons, included artillery batteries used for shelling Serb towns, in violation of a UN arms embargo. An important conduit for these clandestine purchases was Cypress International Inc., a war-material supply firm of which MPRI president Vernon Lewis was an Executive.38 In July 1995, MPRI director Carl Vuono, former army chief of staff, met with General Zvonimir Cervenko at an island retreat to plot strategy for Operation Storm (named after Desert Storm), in which Croat soldiers killed several thousand Serbs in Krajina and expelled over 150,000 in the war’s largest act of ethnic cleansing.39 MPRI helped the Croat army to implement an “air land and battle doctrine” and provided real time coded and pictorial information from U.S. reconnaissance satellites over Krajina, training units directly implicated in war crimes. Serb victims sued MPRI for complicity in genocide, stating that the company was aware of the pro-Nazi sentiments of Croat leader Franjo Tudjman and his henchmen and that “there could be no doubt of what the training and armaments that MPRI was going to provide. During the contract negotiations, [Defense] Minister [Gojko] Susak told the MPRI representative: ‘I want to drive the Serbs out of my country.’”40

DynCorp International was another company that contributed to the defeat of Serb forces in the Balkans, though it brought embarrassment when two of its employees were accused of participating in the child-sex slave trade and illegal arms trade.41 First getting into the war business airlifting supplies to U.S. troops during the Korean War, DynCorp had worked to upgrade the FBI’s security network, trained police forces on the U.S.-Mexican border and assisted in counterinsurgency operations in Indonesia, Sudan, Kuwait and Haiti and drug war operations in the Andes.42 The chairman of DynCorp from 1988-1997, Herbert S. “Pug” Winokur, headed the finance committee of the energy giant Enron, where he allegedly approved the creation of offshore subsidiaries to hide losses from bogus transactions and money laundering.43 James Woolsey, DynCorp director from 1988-1989, was affiliated with the neoconservative Committee on the Present Danger and later Project for the New American Century and became CIA director under Clinton. Another board member, Michael P. C. Carns, was nominated to be CIA director after serving as a top aide to the Joint Chiefs during the Persian Gulf War.44 DynCorp’s importance to clandestine operations was revealed when the plane of an employee with links to the CIA, Robert Hitchman, was shot down by Sendero Luminoso guerrillas in Peru. Secretary of State James Baker asked Hitchman’s son to keep quiet, stating: “[The government] didn’t want the public to know the full extent of American involvement in drug wars in Latin America.”45

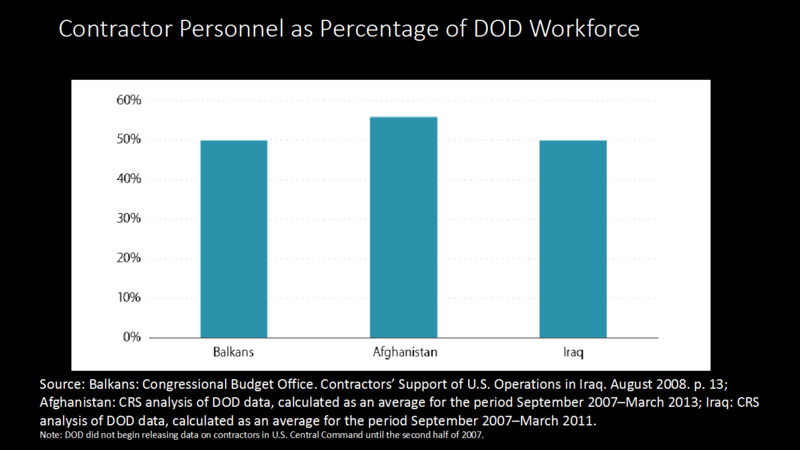

The GWOT was considered the “super bowl” for PMC’s who had made over $100 billion in Iraq alone by 2008. A senior officer in Afghanistan commented that “the Department of Defense is no longer a war fighting organization, it’s a business enterprise. Afghanistan is a great example of it. There’s so much money being made of this place…Would you ever think of cutting back?”46 As resistance to U.S. occupations intensified, the military become overstretched and began lowering its recruitment standards to include ex-criminals and even neo-Nazis in the absence of a draft.47 A number of soldiers refused redeployment for second and third tours.48 Private contractors filled an important void, performing key military functions such as protecting diplomats, transporting supplies, training police and army personnel, guarding checkpoints and other strategic facilities including oil installations, providing intelligence, helping to rescue wounded personnel, carrying out interrogation and even loading bombs onto CIA drones.49 A British mercenary pointed out that military commanders “do not like us, [but] tolerate us as a necessary evil because they know that if it wasn’t for us, they would need another twenty-five thousand to fifty thousand troops on the ground here.”50 And politically after Vietnam this was impossible to arrange.

|

A Congressional study found that private contractors made up 65 percent of the Pentagon’s military force in Afghanistan and 29 percent of the workforce in the intelligence agencies, taking up 50-60 percent of the CIA’s budget. The National Security Agency (NSA) employed 480 separate companies who came up with most of its technological innovations. Private contractors helped to revolutionize warfare by building unmanned Global Hawk surveillance drones equipped with light censors capable of seeing two hundred miles away, backpack surveillance kits, and a computer program making it easier to find makers of roadside bombs.51 They also contributed to the rise of a domestic surveillance state, with the Pentagon hiring Iran-Contra felon John Poindexter, convicted of lying to and obstructing Congress, to develop an IT system to counter asymmetric threats by “achieving total information awareness.” Poindexter proposed a national betting parlor that would harness the forces of market capitalism to predict the likelihood of acts of terrorism, much as commodity traders speculate on the future price of pork or electric power.52 This was the ultimate attempt by elements of the national security bureaucracy to profit from the climate of fear they themselves did much to help create by hyping the possibility of terrorist attack, as with the WMDs and Iraq.53

The Bush administration hired companies with known links to human rights abuses such as Wackenhut Services Inc., whose stock soared after it won contracts for protecting power-plants and convoys and taking on firefighting duties in Iraq. Founded by an ex-FBI agent, the company had compiled a database of over 2.5 million alleged communists, agitators, union militants and other dissidents during the cold war in collaboration with Christian far right organizations and was employed by Exxon-Mobil to spy on and harass environmentalists. After training death squad outfits in Central America during the 1980s, Wackenhut got into the private prison industry, running a facility in Jena Louisiana that according to the Justice department, “failed to provide reasonable safety or adequate medical care,” and one in Santa Fé where guards abused and raped female inmates.54

Aegis Defense Ltd., a British company awarded the so-called Matrix contract to protect the US Army Corps of engineers and to assist in intelligence gathering, boasted of the presence of Iran-Contra felon Robert McFarlane on its board. It was headed by Tim Spicer, a former Scots Guard with ties to large mining conglomerates who was involved in illicit arms deals and coup plotting in Africa, suppression of a rebellion in Papua New Guinea, and commanded a unit in Northern Ireland that shot a Catholic teenager in the back. In October 2005, Aegis employees put up an online video of colleagues firing on civilian cars in Iraq to the backdrop of Elvis Presley’s Mystery Train.55 Erinys, recipient of a $40 million contract to protect Iraqi oil pipelines and refineries, was founded by an intelligence officer in the apartheid-era South African military who later served as a political adviser to Angolan warlord Jonas Savimbi. It employed members of death squad units who had firebombed the homes of anti-apartheid activists. Its staff in Iraq included Ahmad Chalabi’s private militiamen.56

In October, 2005, after the Pentagon granted the legal immunity from prosecution, it authorized “the use of deadly force when necessary [by private military contractors] to execute their security mission.” Herbert Fenster, a lawyer representing several contractors, aptly described this measure as a “sea change that enabled civilians to assume combat roles with only vague limitations that they not perform preemptive attacks.”57 Mercenary units were called on several occasions as military reinforcements with some of them even winning Purple Hearts and other battlefield commendations. Many were deployed with M-4s, the same weapons as U.S. troops.58 Journalist Steve Fainaru saw this as a recipe for disaster as “they give them weapons . . . and turn them loose on an arid battlefield the size of California, without rules. . . . None of the prevailing laws — Iraqi law, U.S. law, the [Uniform Code of Military Justice], Islamic law, the Geneva Conventions — applied to them.”59

Again and again PMCs shot up civilians, sometimes just because they “felt like killing today,” as one Triple Canopy employee put it. Bronze Star recipient Bill Craun told NBC about how Kurds hired by Custer Battles, which was given the contract to guard the Baghdad airport (and was later accused of defrauding the US government of tens of millions of dollars), randomly shot unarmed Iraqi teenagers in the back and rolled over cars loaded with children.60 United States Investigative Services (USIS), a Carlyle Group company that trained police commando units, was accused of torturing and killing Iraqis in Fallujah and also defrauding the government. After reporting the abuses, Colonel Theodore Westhusing committed suicide, leaving a note which stated that he did not “volunteer to support corrupt, money grubbing contractors, nor work for commanders only interested in themselves [referring to David Petraeus who oversaw USIS operations].61

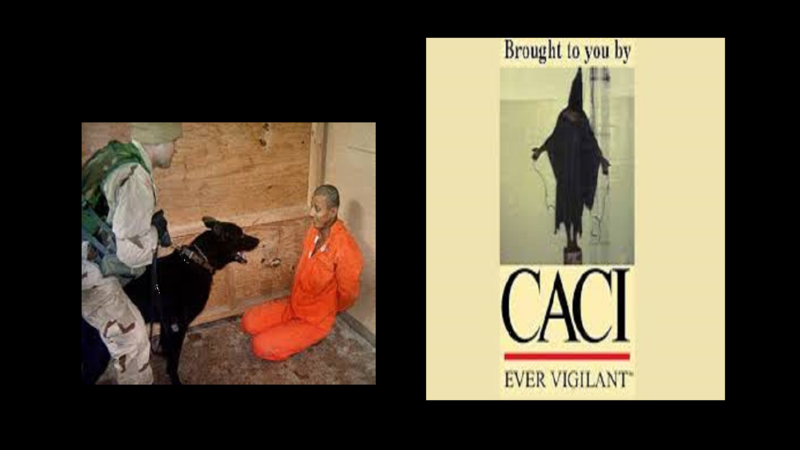

SAIC, an innovator in weapons systems whose board included three ex-CIA directors and three former defense secretaries, was given a contract to overhaul Iraq’s prison system, hiring prison executives implicated in domestic human rights violations such as Gary Deland who wrote a manual for conducting executions by firing squad and lethal injection while head of Utah’s Correction Agency. According to General Janis Karpinski, head of the Abu Ghraib prison, Deland went about his job in Iraq “like some kind of cowboy commando with a knife strapped to his leg, a side arm on his belt and an automatic rifle slung on his back.”62 Employees of California Analysis Center Incorporated (CACI), “the grandfather of defense technology firms” headed for a time by Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage (2001-2005), allegedly introduced some of the most brutal interrogation techniques at Abu Ghraib including sleep deprivation, stress positions and sexual humiliation. It also let loose German shepherd attack dogs which they had had been trained to handle. An army investigation found two CACI employees culpable in “inhumane and sadistic misconduct.” Nevertheless, CEO Jack London praised them for doing a “damned fine job,” and the Pentagon rewarded CACI with a fresh $156 million contract to train instructors at an army intelligence school in Arizona.63 (CACI’s profits totaled $350 million in 2005 and $3.7 billion by 2012).64

The abuses by PMCs in the GWOT are far from an aberration, as atrocities have been endemic to American war making since the Indian Wars. During the Korean and Vietnam Wars, U.S. troops tortured and killed tens of thousands of civilians as a product of an “atrocity producing environment,” in which nationalist insurgents easily blended into the civilian population.65 At No Gun Ri, up to three hundred refugees, including women and children, were strafed and killed by U.S. planes and shot by members of the Seventh Cavalry, George Custer’s old outfit, after being forced into an eighty foot long underpass.66 Journalist Keyes Beech noted that, “it is not a good time to be a Korean, for Yankees are shooting them all.”67 In Vietnam’s Operation Speedy Express, the Ninth Infantry Division under the command of Julian Ewell and Ira Hunt claimed an enemy body count of 10,899 at a cost of 267 American lives, with only 748 weapons seized. General David Hackworth acknowledged that “a lot of innocent Vietnamese civilians got slaughtered because of the Ewell-Hunt drive to have the highest count in the land.”68

The lives of “hadjis” in the GWOT have often been considered as cheap as “the gooks” of yesteryear. American forces have bombed wedding parties, gone on shooting rampages and urinated on the corpses of enemy fighters.69 A Senate Intelligence Committee report revealed a systematic pattern of torture by the CIA, with one prisoner dying from hypothermia after he was forced to sit naked on a cold concrete floor for 48 hours.70 The problem of atrocities and impunity ultimately goes far beyond the use of PMCs but relates to the institutional culture of the U.S. military. What is new is the financial reward being amassed by those responsible for carrying out some of the crimes.

Mercenary units throughout history have been known for their lack ofdiscipline in part because their main motivation is financial gain and because they attract a certain type of person.71 Contractors in Iraq had legal immunity and did not follow rigorous recruitment standards; people in some companies could get a job by simply sending an email. There was also a culture of militarized masculinity. Security guards working for Wackenhut engaged in nude homoerotic hazing rituals and sex trafficking and smuggled hookers into the American embassy in Kabul.72 Many contractors took steroids and sat around drinking beer during their off-hours bragging about the numbers they had killed. One Triple Canopy employee stated: “It was like romanticizing the idea of killing to the point where dudes want to do it…Does that mean you’re not a real man unless you’ve dropped a guy?” He added: “There was a certain group of guys who were always trying to measure their wieners based on how many times they fired.”73

While often touting their patriotism, money was indeed a key motivating factor for most of the men. At a pep talk, a KBR speaker forced a group of truckers to chant “FOR THE MONEY” after he asked them why they were going to Iraq.74 Chris Jackson was $20,000 in debt, and so took a job with Crescent Security shipping supplies in from Kuwait. “When I got to that point, I would have sold myself to the devil.” he said. “All you’re thinking about is the money. You have $50,000 in the bank and all you’re thinking is, another month and I’ll have $57,000….I’m in love with the money.” A week before being kidnapped and killed, another Crescent employee stated that “he’s always liked this kind of work” having been in the Marine Corps, and was also getting “caught up on some bills…And I heard they’re coming out with that new Dodge Challenger in 2008. I want that.”75

Jon Coté, a University of Florida student and army veteran who went to work for Crescent told a reporter: “This place [Iraq] is a money making machine…There’s just so much of it. It really amazes me: a war how it creates money, generates it; how a war can be profited off. All you have to do is look around: the amount of food, fuel and oil and shit that we use over here. All the companies that work over here are getting rich over here.”76 Coté was subsequently kidnapped by insurgents and killed one week before he was slated to return to college. His comments reveal a kind of political awakening as to his place in the system and the economic forces that had a stake in perpetuating the war long after its original purpose had receded.

The ascendancy of neoliberal economic philosophy since the 1970s has coincided with the growth of hyper-consumerist and individualistic philosophies in the United States embodied under the mantra promoted by Ronald Reagan that “greed is good.” Private contractors like Coté and their bosses were the ultimate embodiment of this value system. Like the gold-rushers and filibusters of yesteryear, they thrust morality aside in seeking to cash in on the war economy and thought little about the consequences for the Iraqi or Afghan people. And some paid the ultimate price. The war in Iraq and the way it was fought, however, exposed for the world the dark consequences of running a society guided by selfish principles. Mercenaries and the bad publicity that they generated led many people to recognize that “greed is not good” and will in fact lead us into a new dark age.

As in earlier interventions in Vietnam and Laos, cronyism in the rewarding of contracts helped to taint the U.S. occupations and fueled corruption throughout society. Bribery charges took down a sitting U.S. Congressman on the intelligence committee and the CIA’s number three executive. The rising tide of contractors became so overwhelming that the Pentagon was unable to account for billions of dollars, with Oxfam International reporting that vast sums of aid had been “lost in corporate profits of contractors and subcontractors which can be as high as 50 percent on a single contract.”77

Like its South Vietnamese counterpart under Nguyen Van Thieu and Nguyen Cao Ky, Hamid Karzai’s regime in Afghanistan evolved into a full-blown narco-kleptocracy, its banking and justice system operating as giant extortion rackets. Government officials accepted bribes from Taliban commanders and secured their release from prison to ensure the perpetuation of the war so they could continue to grow rich off of foreign aid money and the war economy. The son of the Defense Minister received a major contract for shipping fuel and military supplies to Western troops and aid organizations. Another leading contractor was a warlord known to Kandahar villagers as “the butcher.”78 PMC’s were forced to pay protection bribes to local police chiefs and also insurgent groups who kept offices to facilitate payment. The U.S. government was thus in effect financing its own assassins.79

Congressional investigations uncovered numerous cases of fraud and dangerously poor construction by PMCs, resulting in the deaths of at least eighteen troops including a Green Beret who was electrocuted in a shower installed by Kellogg, Brown and Root (KBR) whose war contracts totaled $39.5 billion. Over 25,000 soldiers got sick after KBR did not properly chlorinate the water at Camp Ramadi owing to cost-cutting measures and because they burned waste in environmentally unsound ways with little oversight. A police training academy built by DynCorp was so poorly constructed, urine and feces fell on its students.80 These occurrences show the delusions of neoconservatives in their belief in the inviolability of private business.

Many PMCs reinforced a colonial relationship by employing Third World peoples to do menial tasks sometimes under slave-like conditions, paying natives less than one tenth the salaries of Westerners.81 Crescent Security, for example, paid Iraqis only $600 a month compared to $8,000 for Westerners. Their Iraqi staff performed the most dangerous work, manning PX machine guns in the back of Avalanche trucks transporting equipment for U.S. troops and businesses, rolling down the highway for hours fully exposed, their faces covered to mask their identities while ex-pats sat in air-conditioned cabs listening to their MP-3 players. “Internally I can’t justify it,” owner Franco Pico, a former South African military police officer in Angola who was pulling in $10 million per month said, “but the market dictates it.”82

Staffed and run by ex-CIA operatives, PMC’s have been integral to the mounting of covert operations, including assassinations and possible black flag operations in which they planted terrorist bombs that they blamed on insurgents.83 In one curious case, a former Green Beret and con man Jonathan Keith Idema, ran a vigilante antiterrorism campaign and secret prison in which he tortured innocent Afghan suspects. Passing intelligence to Lt. Gen Jerry Boykin’s staff and foiling an assassination plot against the Afghan Education Minister, Idema went too far when he kidnapped a Supreme Court Justice. He was sentenced to ten years in prison, though given an apartment sized cell with satellite TV, Persian carpets and specially prepared meals, and was pardoned by Afghan President Hamid Karzai after three years.84

Michael D. Furlong, a former army psychological warfare expert, was another contractor to run his own private army to hunt Islamic extremists.85 Accused by the Pentagon of leading unauthorized intelligence operations and misleading senior government officials, Furlong helped to arrange a contract between ex-CIA operative Duane “Dewey” Clarridge, convicted of lying to Congress about Iran Contra, and American International Security Corps, a Boston company that financed private intelligence gathering efforts. A war-hawk who planned the mining of Nicaraguan harbors in violation of international law, Clarridge investigated Hamid Karzai’s alleged addiction to heroin and the-drug related corruption of his brother Ahmed Wali for the purpose of keeping them more pliable or to plot a coup. Clarridge also fed intelligence reports that were in some cases dubious to Fox News commentators, including his old comrade Oliver North, with the goal of supporting a more aggressive military policy.86 His actions epitomize the danger of privatizing intelligence in that private citizens can take advantage of the chaos of the war zone to advance their own agendas or feed misinformation to the military command and public.

Journalist Jeremy Scahill exposed how Blackwater helped develop plans for drone strikes and assassination as part of the secret Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). The company, whose board included many ex-CIA operatives, oversaw black operations in Iraq and was at times hired directly by foreign governments, most notably Pakistan for counter-terrorism work, allowing the U.S. to deny that it had a military presence in the country.87 The façade was exposed when Raymond Davis, a Blackwater operative and CIA agent who ran a firm that sold surveillance equipment, was imprisoned after killing two Pakistanis whom he suspected were shadowing him, along with an innocent motorcyclist. Davis was likely part of a mission to uncover links between Pakistan’s intelligence service (ISI) and the jihadist organization, Lashkar-E-Taiba.88

Built in the image of Executive Outcomes, a PMC founded by veterans of South Africa’s Buffalo brigade, which financed death squad operations through illicit ivory and diamond smuggling, Blackwater’s name first became known after four of its employees were killed and their bodies mutilated by mob-backed insurgents in Fallujah, prompting a military siege of the city that left it in ruins. Company spokesmen claimed that the four men were providing security for army food suppliers though no food trucks were described as being even close to the scene. Considered at the time the “Cadillac” of the mercenary industry, Blackwater joined in the hunt for Osama bin Laden after 9/11 and received a $27 million no-bid contract to protect Ambassador L. Paul Bremer, head of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in May 2003.89 The company also received a $5.4 million contract for security in Kabul and later trained the militia of a ruthless Afghan warlord, Abdul Raziq, who tortured and murdered tribal enemies.90

|

Bremer escorted by Blackwater Security Guards |

CEO Erik Prince, was a former Navy Seal and proponent of Christian values and free-market economics who donated heavily to the GOP. He invested his family fortune in the creation of Blackwater in the late 1990s in order to “fulfill the anticipated demand for government outsourcing of firearms and related security training,” building up an airstrip, naval armada, fleet of helicopters and mock battlefields at its headquarters in Moyock, North Carolina. The front doors there featured barrels from .50 caliber machine guns and a glass case displayed replicas of guns used to assassinate presidents.91

Publicly, Prince took pains to present Blackwater as a “patriotic extension of the US military whose men “play defense in a dangerous war zone where they bleed red, white and blue as they heroically protect reconstruction officials trying to weave the fabric of Iraq, and other shattered nations, back together.”92 The company took greatest pride in its record of keeping alive all the people they were charged with protecting. “Those guys guard my back,” said Ambassador Ryan Crocker, “And I have to say they do it extremely well.”93 However, they shot scores of civilians, adopting the motto “we shoot to kill and don’t stop to check a pulse.” Brig. Gen. Karl Horst of the Third Infantry Division told The Washington Post that he had tracked at least a dozen civilian shootings in Baghdad just between May and June of that year, with six Iraqis killed.94 An Iraqi official commented that, “Blackwater has no respect for the Iraqi people. They consider Iraqis like animals, although actually I think they may have more respect for animals. We have seen what they do in the streets. When they’re not shooting, they’re throwing water bottles at people and calling them names. If you are terrifying a child or an elderly woman or you are killing an innocent civilian who is riding in his car, isn’t that terrorism?”95

|

On Christmas Eve 2006, Andrew Moonen, a firearms technician in Baghdad working for Blackwater got drunk in the Green Zone and then shot and killed a Guard for Iraq’s Vice-President. The State Department kept the whole case quiet, and within two months Moonen was back to work as a Pentagon contractor in Kuwait.96 There was a similar cover-up of water-boarding and torture by Blackwater contractors employed by the CIA and the murder of Afghan civilians, with the Pentagon’s Inspector General going on to work for Blackwater as a lead counsel.97 On September 16, 2007, four Blackwater contractors killed 17 unarmed civilians, including women and children, and wounded at least 24 in a shooting rampage in Baghdad’s Nisour square. One of the culprits, Paul Slatten, an ex-army Sergeant from Sparta, Tennessee, stated that he wanted to “kill as many Iraqis as he could as payback for 9/11.” Blackwater executives reportedly paid $1 million in secret bribes to Iraqi officials to keep the incident under wraps and the State Department gathered shell casings at the scene of the shooting to protect the firm, renewing Blackwater’s contract seven months later.98The victims eventually reached a settlement on a lawsuit by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and, in a rare instance of judicial retribution, Slatten was convicted of murder and three others of manslaughter in a federal district court in November 2014.99 The Department of Justice in this case showed a willingness to hold PMCs accountable for war crimes, though not the top-level officials who hired them and started the war.100 Blackwater retained its primacy as an agent for U.S. power on the ground in Iraq and elsewhere, including in the United States.

True to Mark Twain’s maxim that one cannot have an empire and a functioning democracy, Blackwater delivered training to domestic police SWAT units in the arts of sniping, hand-to-hand combat, and tactics appropriate to counterinsurgency warfare. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, FEMA contracted Blackwater at a rate of $240,000 per day to secure petrochemical and other government/corporate facilities in and around New Orleans. Showing stark continuity with Iraq, company employees were responsible for the shooting deaths of undetermined but potentially large numbers of civilians.101

In 2010, Blackwater was forced to pay $42 million in fines to the State Department for illegal weapons exports to Afghanistan, making unauthorized proposals to train troops in South Sudan and providing sniper training for Taiwanese police officers.102 In the same year, however, the company (renamed Xe then Reflex Response) was given a $220 million contract to guard the giant U.S. embassy in Baghdad, and after merging with Triple Canopy, a $529 million contract by the Abu Dhabi Sheikh to train the security forces of the United Arab Emirates, a key U.S. government ally.103 Blackwater veterans also went on to train rebel forces bent on toppling the Qaddafi and Assad governments in Libya and Syria. According to emails hacked by Wikileaks, James F. Smith, a former Blackwater director connected to the CIA, assisted in Muammar Qaddafi’s assassination while working for SCG International, a firm which also provided air cover for CIA agents engaging with Syrian opposition forces in Turkey.104

Blackwater’s main rival through the first decade of the War on Terror, DynCorp, also earned notoriety for shooting incidents and for its link to human rights violations after receiving contracts to Guard Afghan President Hamid Karzai and to train internal security forces in Afghanistan and Iraq.105 Bought by a Wall Street private equity firm in 2005, and sold five years later at a $300 million profit, DynCorp had a checkered history, having been sued by Ecuadorian peasants for spraying herbicides that drifted across the border, with its employees caught smuggling drugs while supposedly fighting a “War on Drugs” in Colombia.106 Its ill repute was only enhanced in Afghanistan where it helped to run counter-narcotic operations which special envoy Richard Holbrooke characterized as the “most wasteful program” he had seen in a forty-year career. CNN anchor Tucker Carlson reported that contractors with whom he was embedded in Iraq cut through long gasoline lines and beat a suspected kidnapper “into a bloody mound” before turning what was left of him “over to the police.”107

With such men in charge, Iraqi and Afghan police forces became infamous for their corruption and brutality and were a primary target of insurgent attacks.108 As in previous interventions, American advisers harbored racial stereotypes and had a paternalistic and colonial mindset. In a memoir of his year in Iraq, Robert Cole, a police officer from East Palo Alto, California, and a DynCorp employee, explains that these attitudes were ingrained in a mini–boot camp training session, where he was “brainwashed, reprogrammed, and desensitized” and “morphed” into a “trained professional killer.” One of the major lessons taught was that Iraqis understand only force. Cole was told to shoot first and think later and to instruct police to do the same. “If you see a suspicious Iraqi civilian, pull your weapon and gun him down,” he was instructed. “You don’t fire one . . . or two shots. . . . You riddle his sorry ass with bullets until you’re sure he’s dead as a doorknob.”109

This is an inversion not just of democratic police methods but even of Western counterinsurgency doctrine, which, at least in theory, advocates moderation in the use of force in order to avoid antagonizing the population and creating martyrs.110 No wonder the scope of violence has been so vast. Building on Clinton precedents, Bush privatized war as part of the attempt to distance the public from the GWOT. Martial values had declined considerably since the Vietnam era, especially outside the South, and the public had become more skeptical towards war, though also comfortable with its material living standards, and easily distracted by America’s media-entertainment complex.111 Bush administration planners thus knew that they could pursue their ambitions for regime change and the prying open of Iraq’s oil market while fighting in Afghanistan too, so long as they did not have to restore the draft. Private military contractors were crucial to the strategy. Though millions did protest on the eve of the Iraq War, once the war was under way no large-scale rebellion developed comparable to the 1960s despite the proliferation of war crimes comparable to those carried out in Vietnam. The campuses were quiet as students did not have a personal stake as they had facing the draft during the Vietnam War. Bush ultimately established a blueprint for the Obama administration, which has sustained an aggressive foreign policy by continuously subcontracting counterinsurgency operations, while expanding the use of air power and drones so that American combat fatalities are limited.112

The growth of the corporate war economy represents the logical outgrowth of a capitalist system which values “profits over people,” and has contributed to the erosion of democracy.113 The project on government oversight identified 224 high ranking government officials who moved through the revolving door to become lobbyists or high level executives of government contractors, and disclosed that at least two-thirds of the former members of Congress who lobbied for top 20 government contractors “served on authorization or appropriations committees that approved programs or funds for their future employer or client while they served in Congress.”114 The Center for Public Integrity reported that 14 companies that were awarded government contracts in both Iraq and Afghanistan donated almost $23 million in political contributions since 19990, with George W. Bush receiving more money from these companies than any other candidate.115 Blackwater gave $80,000 to President Bush a month before the 2000 election, and $66,000 to the Green Party in Pennsylvania during the 2006 cycle in the hope of siphoning votes from the Democrats and reelecting Republican Senator Rick Santorum.116

Under the 2010 Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling, corporations now have few restrictions on campaign financing. According to Open Secrets, a watchdog website, individuals and political action committees associated with the defense sector contributed more than $27 million to political candidates during the 2012 campaign cycle, with far more going to Republicans than Democrats: $16.4 million versus $11 million. In that year, DynCorp gave over $300,000 to Super PACs, 52 percent to Republicans, and CACI $137,000 to Republicans compared to $21,000 for Democrats. SAIC, which helped press the case that WMDs existed in Iraq and was the lead contractor on a $1.2 billion government surveillance program, gave over $200,000 and another $344,000 in 2014, 66% to Republicans. This was at a time when the San Diego based company known as NSA-West was taking control over the domestic drone market and developing biometric technologies adopted for social control purposes.117

|

Anticipating the fight against terrorism as the next big source of government revenue, SAIC in the late 1990s had established a Center for Counterterrorism Technology and Analysis that assessed and often inflated terrorist “threats,” exemplifying how the privatization of intelligence leaves opportunity for the manipulation of public opinion to ensure a permanent war mobilization. Founded in 1969 by J. Robert Beyster, a nuclear physicist who had worked on the Manhattan Project, SAIC ran a program that fed disinformation to the foreign press and set up a media service in Iraq which served as a mouthpiece of the Pentagon. SAIC’s chief operations officer from 1993-2006, Duane Andrews, was a protégé of Dick Cheney who provided fake satellite photos showing a build-up of Iraqi troops on the Saudi Arabian border as a staff member on the House Intelligence Committee in 1991. Another board member, General Wayne Downing, was a close associate of Ahmad Chalabi who proselytized hard on television for an invasion of Iraq. The FBI at one point even suspected an SAIC employee for the 2001 anthrax mailings, which did so much to create a climate of fear enabling support for the War on Terror and passage of the USA Patriot Act, a bonanza for SAIC which recorded net profits of over $8 billion per year by 2006.118

The ability of companies like SAIC who profit massively from war to finance elections, lobby the government and manipulate public opinion represents a dangerous evolution of the military-industrial complex from Dwight Eisenhower’s day.119 Beholden to its donors, the Bush administration budgeted $647.2 billion on “defense” in 2008, higher than at least the next ten countries combined.120 Obama has retained record military spending.121 One of his top contributors, Lester Crown, was a leading arms manufacturer, and his top intelligence official, James Clapper Jr., was an executive with Booz Hamilton (the same company that employed Edward Snowden) who lied to Congress about NSA surveillance. During Obama’s presidency, PMC’s have helped sustain and promote an array of conflicts including Libya, Afghanistan, Syria and again Iraq. They have taken over many CIA-functions such as efforts to infiltrate and co-opt social movements as in the Arab Spring.122 They have also been crucial to the War on Drugs and are invariably found at the forefront in lobbying to increase drone use including on the U.S.-Mexican border and for domestic policing as dystopian science fiction narratives of mass surveillance and killer robotic machines become a reality.123

Edward Gibbon in his monumental The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire attributed Rome’s collapse in good measure to the “abandonment of military service” and “dependence on the rude valor of barbarian mercenaries.”124 While it is difficult to tell if the United States is headed the way of Rome, what is clear is that the use of mercenaries failed to turn the tide in the protracted U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and has paved the way for blowback. Warped spending priorities accentuated by PMCs and their lobbyists, together with political gridlock in U.S. politics have resulted in fiscal insolvency, decaying public services, declining educational standards and inability to confront environmental, immigration and social problems.125 Before it is too late, progressive forces should mobilize under the goal of reorienting American foreign policy in a more peaceful direction.126 Congressional investigations along the lines of the 1930s Nye commission on corporate war profiteers (“merchants of death” as they were then called) and 1970s Church committee hearings on CIA abuses would be a good start in raising public awareness about the threat to democracy bred by the privatization of military and intelligence functions. They could in turn lead to legislation that properly regulates or even outlaws PMCs along with the signing of the existing UN treaty. Journalist Tim Shorrock wrote in The Nation that, “in-sourcing national security functions [already] has wide political support and would go a long way towards restoring public trust in the military. And it might keep us from engaging in foolish wars that only create more enemies and make us less safe.”127 No doubt this is true but the interests that have a stake in keeping the world less safe will be difficult to dislodge, absent the emergence of a social movement capable of swaying public opinion.

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Jay P. Walker Assistant Professor of History at the University of Tulsa. He is the author of Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation-Building in the American Century and The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs.

Recommended Citation: Jeremy Kuzmarov,””Distancing Acts”: Private Mercenaries and the War on Terror in American Foreign Policy”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 52, No. 1, December 22, 2014.

Related articles

•Peter Dale Scott, The Fates of American Presidents Who Challenged the Deep State

•Peter Dale Scott, The State, the Deep State, and the Wall Street Overworld

•Peter Dale Scott, America’s Unchecked Security State: Part II: The Continuity of COG Detention Planning, 1948-2001.

•Jeremy Kuzmarov, Bomb After Bomb: US Air Power and Crimes of War From World War II to the Present.

•Jeremy Kuzmarov, American Police Training and Political Violence: From the Philippines Conquest to the Killing Fields of Afghanistan and Iraq.

The author was influenced by the writings of Peter Dale Scott in putting together this piece, and would like to thank Mark Selden and an anonymous reviewer for their excellent advice.

1Col. Gerald Schumacher, A Bloody Business: America’s War Zone Contractors and the Occupation of Iraq (New York: Zenith Press, 2006), 175-187; “Heavy Metal Mercenary,” Rolling Stone, November 9, 2004. Weiss comes from a family with a long history of criminal activity. His father was a bookie murdered after skimming the top off of laundered money he delivered to gangsters. His sister was indicted for stabbing his mother, Rose Weiss, 69. Adam Foxman and John Scheibe, “Daughter Held in Fatal Stabbing of Simi Woman,” Ventura County Star, February 7, 2008.

2Steve Fainaru, Bad Boy Rules: America’s Mercenaries Fighting in Iraq (Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2009), 22; Moshe Schwartz and Jennifer Church, “Department of Defense’s Use of Contractors to Support Military Operations,” Congressional Research Service, May 17, 2013; Peter Van Buren, We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2012). PMCs can be defined as profit-driven organizations that trade in professional services linked to warfare.

3Suzanne Simons, Master of War: Blackwater USA’s Erik Prince and the Business of War (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 158; Rod Nordland, “Risks of Afghan War Shift from Soldiers to Contractors,” New York Times, February 11, 2012; Dana Priest and William Arkin, Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State (Boston: Little & Brown, 2011), 184.

4A list of 33 countries that ratified the treaty is available here. Notably absent are supposedly “civilized countries like Canada, Britain, France and Japan. See also José L. Gomez del Prado, Chairperson, UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries “Mercenaries, Private Military and Security Companies and International Law,” University of Wisconsin Law School.

5See Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007).

6Michael Schwartz, War Without End: The Iraq War in Context (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2007); Greg Muttit, Fuel on the Fire: Oil Politics in Occupied Iraq (New York: New Press, 2012); Juan Cole, “The Fall of Mosul and the False Promise of Modern History,” History News Network, June 12, 2014; Timothy Shorrock, Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 52.

7Simons, Master of War, 143; Jeremy Scahill, Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army (New York: The Nation Books, 2007), 55. Blackwater was renamed Xe Services in 2009 and Academi in 2011.

8 Donald H. Rumsfeld, “Transforming the Military,” Foreign Affairs (May-June 2002); Stephen Armstrong, War PLC: The Rise of the New Corporate Mercenary (London: Faber & Faber, 2008), 80; Allison Stanger, One Nation Under Contract: The Outsourcing of American Power and the Future of Foreign Policy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 86.

9See Carl Boggs, “The Corporate War Economy” in The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination, ed. Steven Best et al. (Boston: Lexington Books, 2011); Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man (Boston: Beacon Press, 1956); C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: 1956).

10 On U.S. public opinion and war, see Adam J. Berinsky, In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion From World War II to Iraq (University of Chicago Press, 2009). A recent poll showed that 58 percent supported significant reductions in military spending. On the growing democracy deficit, see Noam Chomsky, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and Assault on Democracy (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006).

11Nick Turse, The Changing Face of Empire: Special Ops, Drones, Spies, Proxy Fighters, Secret Bases, and Cyberwarfare (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012).

12See Andrew Bacevich, Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country (New York: McMillan, 2013).

13Michael Ignatieff, Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond (New York: Viking Press, 2000), 189.

14See Tom Engelhardt, The End of Victory Culture: Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation, rev ed. (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007).

15 See Fred Branfman, Voices from the Plain of Jars: Life Under an Air War, with new preface by Alfred W. McCoy (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013); Peter Dale Scott, The War Conspiracy (Indianapolis: Bobbs Merrill, 1972). In the PBS history of the Vietnam War, CIA Director William Colby bragged that the Hmong army kept the North Vietnamese at bay for over 10 years in a cost effective policy that aroused very little opposition because few knew about it.

16On the importance of Korean units, known for their brutality, to U.S. military operations in Vietnam see Frank Baldwin, Diane Jones and Michael Jones, America’s Rented Troops: South Koreans in Vietnam (American Friends Service Committee, 1971).

17The Carlyle Group’s board has included George H. W Bush and former British Prime Minister John Major. Tony Geraghty, Soldiers of Fortune: A History of the Mercenary in Modern Warfare (New York: Pegasus Books, 2009), 30. Douglas Valentine, The Phoenix Program (New York: 1991).

18 See James Carter, Inventing Vietnam: The United States and State Building, 1954-1968 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

19See David Cortright, Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War, rev ed. (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005); Jeremy Kuzmarov, The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009).

20 On the strength of the antiwar movement and its impact, see Marilyn B. Young, “Resisting State Terror: the Anti-Vietnam War Movement” in War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century, ed. Mark Selden and Alvin Y. So (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 235-251.

21Joseph Trento, Prelude to Terror: the Rogue CIA, The Legacy of America’s Private Intelligence Network and the Compromising of American Intelligence (London: Carroll & Graf, 2005). For the case of Mike Echanis, a martial arts master who trained Nicaraguan commandos under Dictator Anastasio Somoza, see Jay Mallin and Robert K. Brown, Merc: American Soldiers of Fortune (New York: McMillan, 1979), 164.

22Wilfred Burchett and Derek Roebuck, The Whores of War: Mercenaries Today (London: Penguin Books, 1977); John Stockwell, In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story (New York: Norton, 1978), 220, 225; Mallin and Brown, Merc, 179; Carey Winfrey, “Texan in the Rhodesian Army Says He Fights for Love, Not Money,” New York Times, September 2, 1979. Daniel Gerheart, 34, was executed by the Angolan government who called him and his comrades “dogs of war with bloodstained muzzles who left a trail of rape, murder and pillage across the face of our nation.”

23Kathi Austin, with William Minter, Invisible Crimes: U.S. Private Intervention in the War in Mozambique (Washington, D.C.: Africa Policy Information Center, 1994), 16; Ken Silverstein, Private Warriors (London: Verso, 2000), 148. A cross-border raid by mercenaries affiliated with the Rhodesian Selous Scouts killed 1,184 “terrorists” in Manika Province, Mozambique compared to only four friendly casualties. A captain in the South African army, Mackenzie went on to work with death squad regimes in El Salvador and Sierra Leone, where his liver was eaten by RUF rebels after his capture. The Vietnam vet was part of a plan to assassinate Zimbabwe’s first president Robert Mugabe.

24 See Richard Harding Davis, Real Soldiers of Fortune (New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1912). MacIver’s storied career included time in India as an ensign in the Sepoy mutiny, in Italy as a lieutenant under Garibaldi, in Spain as a Captain under Don Carlos, in Mexico as a Lieutenant Colonel under Emperor Maximilian, a Colonel under Napoleon III, inspector of Cavalry for the Khedive of Egypt and chief of Cavalry under the King of Serbia.

25 Thomas A. Reppetto, The Blue Parade (New York: Free Press, 1978); Howard H. Elarth, The Story of the Philippine Constabulary (Los Angeles: Globe Print Co., 1949). On the history of the constabulary, see Alfred W. McCoy’s masterpiece, Policing America’s Empire: The U.S., the Philippines and the Rise of the Surveillance State (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009).

26 See Lester D. Langley and Thomas Schoonover, The Banana Men: American Mercenaries and Entrepreneurs in Central America, 1880-1930 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997), 59, 72, 156. Davila’s replacement, Manuel Bonilla awarded Zemurray 10,000 acres of banana land, allowing Zemurray to become the “uncrowned king” of Central America. Cabrera donated $10,000 to Theodore Roosevelt’s presidential campaign. Christmas’ counterparts Guy Molony was a political fixer in New Orleans who provided information on Nicaraguan nationalist Augusto Cesar Sandino.

27 See Burchett and Roebuck, The Whores of War; and Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions: Havana and Washington in Africa, 1961-1975 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); “Kwame Nkrumah Letter to British Prime-Minister,” November 19, 1964, PREM 13, 042, British National Archives, Kew Gardens, London.

28 William D. Hartung, “Mercenaries Inc.: How a U.S. Company Props Up the House of Saud,” The Progressive, April, 1996; Deborah D. Avant, The Market of Force: The Consequences of Privatizing Security (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 148; Tony Geraghty, Soldiers of Fortune: A History of the Mercenary in Modern Warfare (New York: Pegasus Books, 2009), 30. Vinnell served as a cover for CIA agents such as Wilbur Crane Eveland. On the special U.S.-Saudi relationship, see Robert Vitalis, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2007).

29Silverstein, Private Warriors, 181; Dr. J. Robert Beyster, The SAIC Solution: How We Built an $8 Billion Employee-Owned Technology Company (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 49. On Booz Hamilton, which assisted CIA counterinsurgency operations in Philippines under Edward Lansdale, see Peter Dale Scott, American War Machine: Deep Politics, the CIA Global Drug Connection, and the Road to Afghanistan (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 182, 186. Carlucci was Deputy Director of the CIA under Jimmy Carter and a consul in the US embassy in Congo during the early 1960s where he allegedly had a role in Lumumba’s murder. He was subsequently thrown out of Tanzania for plotting against the socialist government. See Francis Schor, “The Strange Career of Frank Carlucci”.

30Ward Churchill, “The Security Industrial Complex” in The Global Industrial Complex, ed. Best et al, 53 discusses the limitations of the anti-Pinkerton bill; Peter Dale Scott, Jonathan Marshall and Jane Hunter, The Iran Contra Connection: Secret Teams and Covert Operations in the Reagan Era (Boston: South End Press, 1987); Leslie Cockburn, Out of Control: The Story of the Reagan Administration’s Secret War in Nicaragua, The Illegal Arms Pipeline, and the Contra Drug Connection (New York: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987). British and American mercenaries like Jack Terrell were sent into Nicaragua to perform sabotage operations. American mercenary pilots like Adler Barriman Seal trafficked in narcotics to finance the operations as they had done in the secret war in Laos.

31See H. Bruce Franklin, Vietnam and Other American Fantasies (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000) and Susan Jeffords, The Remasculanization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989).

32David Holthouse, “The Dark Side of Soldier of Fortune Magazine: Contract Killers and Mercenaries for Hire,” Alternet, September 15, 2011; James “Bo” Gritz, Called to Serve (New York: Lazarus, 1991). Mitchell Werbel III, a veteran of Cuban exile missions and representative of the Nugan Hand bank which was involved in intelligence financing and drug smuggling, with Frank Camper, a Vietnam Special Forces and undercover FBI officer set up a paramilitary training camp in Georgia where mercenaries were schooled in the art of assassination. See Frank Camper, Live to Spend it: A Mercenary Guide for the 1990s (El Dorado, Az: Desert Publications, 1993). Graduates went on to fight in the Philippines, Nicaragua, Lebanon, South Africa and Afghanistan. Two Sikh terrorists who had been at the school also bombed an Air India flight after Camper sold them explosives in a botched sting operation.

33See James W. Gibson, Warrior Dreams: Paramilitary Culture in Post-Vietnam America (New York: Hill & Wang, 1994). One subscriber was Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber and a Gulf War veteran. He was found with a copy of a white supremacist magazine after the attacks distributed by Brown, a former member of the Rhodesian Selous Scouts. For insights on the right-wing paramilitary culture, see also Jerry L. Lembcke, Hanoi Jane: War, Sex & Fantasies of Betrayal (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010).

34 Peter Singer, Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), 15. Halliburton, contractor of Brown, Kellogg and Root (KBR), which built 85 percent of military infrastructure in Vietnam and hired former Defense Secretary Dick Cheney as its CEO, was awarded a deal for base construction and maintenance around the world. See Pratap Chatterjee, Halliburton’s Army: How a Well Connected Texas Oil Company Revolutionized the Way America Makes War (New York: The Nation Books, 2010).

35 Leslie Wayne, “America’s For Profit Secret Army: Military Contractors Are Hired to Do the Pentagon’s Bidding Far From Washington’s View,” New York Times, October 13, 2002, B1.

36Singer, Corporate Warriors, 50.

37 Lynne Duke, “US Military Role in Rwanda Greater Than Disclosed,” Washington Post, August 16, 1997, A1; Wayne Madsen, Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa, 1993-1999 (New York: Edwin Mellen, 1999), 197, 200, 439; Avant, The Market for Force, 154; Steve Coll, Private Empire: Exxon-Mobil and American Power (New York: Penguin, 2012), 147-148; Boggs, “The Corporate War Economy” in The Global Industrial Complex, ed. Best, 32. Initially, the State Department rejected the MPRI contract in Equatorial Guinea, but subsequently approved it after significant petroleum reserves were discovered which it was feared would be taken over by French oil interests.

38Avant, The Market for Force, 110;Genocide Victims of Krajina v. L-3 Communications Corp. and MPRI Inc., in the United States District Court Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division.

39 Wayne, “America’s For Profit Secret Army,” B1; Singer, Corporate Warriors, 126; Silverstein, Private Warriors, 172; Armstrong, War PLC, 73, 74. For a critical view of “humanitarian intervention,” see David Gibbs, First Do No Harm: Humanitarian Intervention and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2009).

40Genocide Victims of Krajina v. L-3 Communications Corp. and MPRI Inc., in the United States District Court Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. The judge said that he was not qualified to preside over the case because the crimes occurred in Bosnia. Croat army units trained by MPRI killed 185 Serb civilians in Mrkonjic in southwestern Bosnia. See also Geraghty, Soldiers of Fortune, 175.

41Singer, Corporate Warriors, 126; Robert Capps, “Outside the Law,” Salon, June 25, 2002; “Sex Slave Whistle-Blowers Vindicated,” Salon, August 6, 2002. DynCorp also played a role in training Kosovo’s police service following the NATO bombing.

42Singer, Corporate Warriors, 13.

43Uri Dowbenko, Bush Whacked: Inside Stories of True Conspiracy (National Liberty Press, 2003); Gretchen Morgenson, “Sticky Scandals, Teflon Directors,” New York Times, January 29, 2006, B1.

44Tim Weiner, “Clinton Chooses Retired General to be CIA Head,” New York Times, February 8, 1995, A1. A decorated Vietnam Air Force veteran, Carns was appointed to the Board of Thickol Corporation, a leading missile manufacturer, two weeks after his retirement. His nomination was blocked because he had violated labor laws in hiring a Filipino maid. Other DynCorp Board members included Russel E. Dougherty, a former chief of staff of the allied command of Europe and Dudley Mecum, former managing director of Citigroup. For a profile of Woolsey, see Laura Rozen, “James Woolsey, Hybrid Hawk” Mother Jones, May/June 2008.

45 Wayne Madsen, Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa, 1993-1996 (New York: Edwin Mellen, 1999), 339; Silverstein, Private Warriors, 184; Ted Galen Carpenter, Bad Neighbor Policy: America’s Futile War on Drugs in Latin America (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2003), 54.

46Priest andArkin, Top Secret America, 188; Stanger, One Nation Under Contract, 2.

47See Matt Kennard, Irregular Army: How the How the US Military Recruited Neo-Nazis, Gang Members, and Criminals to Fight the War on Terror (London: Verso, 2012).

48 Cortright, Soldiers in Revolt, 278; Camillo Mejia, The Road from Ar Ramadi: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Mejía: An Iraq War Memoir (New York: The New Press, 2007).

49John M. Broder and David Rhode, “State Department Use of Contractors Leaps in 4 Years,” New York Times, October 24, 2007;Mark Mazetti, “Blackwater Loses a Job for the CIA,” New York Times, December 12, 2009; Robert Y. Pelton, Licensed to Kill: Hired Guns in the War on Terror (New York: Crown Publishers, 2006).

50Faniaru, Bad Boy Rules, 140.

51Priest and Arkin, Top Secret America, 182, 186; Shorrock, Spies for Hire; Anne Hagedorn, The Invisible Soldiers: How America Outsourced Our Security (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014); James Glanz, “Contractors Outnumber U.S. Troops in Afghanistan,” New York Times, September 2, 2009; Moshe Schwartz and Jennifer Church, “Department of Defense’s Use of Contractors to Support Military Operations,” Congressional Research Service, May 17, 2013.

52Shorrock, Spies for Hire, 52, 53; Shane Harris, The Watchers: The Rise of America’s Surveillance State (New York: The Penguin Press, 2010). In 1995, in a second act of his career, Admiral Poindexter, a nuclear physicist by training, went to work in the private sector developing computer surveillance and data mining technology and was hired by the Pentagon after 9/11. Though pushed out of government by 2003 because his views were considered too extreme, his system became the basis for NSA warrantless surveillance programs. Poindexter continued to advise government leaders and sat on the board of Saffron, a Pentagon contractor which developed memory technology used to track the insurgency in Iraq and predict where IEDs would be located, and which Poindexter believes will help revolutionize intelligence analysis.

53For a historical perspective, see Jerry Sanders. Peddlers of Crisis: The Committee on the Present Danger and the Politics of Containment(Boston: South End Press, 1999) and Edward S. Herman and Gerry O’Sullivan, The ‘Terrorism’ Industry: The Experts and Institutions That Shape Our View of Terror (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989).

54Solomon Hughes, War on Terror, Inc: Corporate Profiteering From the Politics of Fear (London: Verso, 2007), 14-19; Herman and O’Sullivan, The ‘Terrorism’ Industry, 129, 130, 131. Wackenhut consisted of many John Birchers and had on its board Frank Carlucci III, William Raborn, former CIA director, and Clarence Kelley a former director of the FBI. Several members of the company engaged in a scheme to kidnap the US ambassador to El Salvador, Edwin Corr, and blame it on the leftist FMLN in a classic black flag operation. Jefferson Morley, “The Vanishing Kidnap Plot,” The Nation, July 30-August 6, 1988.

55See Steve Fainaru and Alec Klein, “In Iraq, a Private Realm of Intelligence Gathering,”Washington Post, July 1, 2007; Armstrong, War PLC, 43, 54, 160; Hughes, War on Terror, Inc., 103-105; Adam Roberts, The Wonga Coup: Guns, Thugs, and a Ruthless Determination to Create Mayhem in an oil Rich Corner of Africa (New York: Public Affairs, 2006). Aegis also won a major contract to protect the Green Zone. Winston Churchill’s grandson, the conservative MP Nicholas Soames, was on its board. McFarlane admitted to obtaining millions from Saudi Prince Bandar to illegally finance Contra operations.

56Armstrong, War PLC, 151, 152; Hughes, War on Terror Inc, 149, 163; David Isenberg, Shadow Force: Private Security Contractors in Iraq (New York: Praeger, 2008), 96.

57Fainaru, Bad Boy Rules.

58Fainaru, Bad Boy Rules, 19; Geraghty, Soldiers of Fortune, 199.

59Fainaru, Bad Boy Rules, 19.

60Dina Rasor and Robert Bauman, Betraying Our Troops: The Destructive Results of Privatizing War (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2008), 127; Isenberg, Shadow Force, 87.

61Bacevich, Breach of Trust, 132, 133. Some believe that Westhusing, a military ethicist was murdered as a means of keeping the allegations which the army denied secret much as they believe Pat Tillman, who had turned against the war in Afghanistan, was “fragged” by members of his unit to prevent him from becoming a whistleblower.

62Hughes, War on Terror, Inc., 24; Janis Karpinski, One Woman’s Army: The Commanding General of Abu Ghraib Tells Her Story (Miramax Books, 2006). According to Karpinski, Deland and his colleagues photographed themselves sitting on “piles of cash” about the size of a “barbecue” and holding a “fistful of dollars,” with more bills sticking out of their pockets. The money came partly from Iraqi oil receipts allegedly. On SAIC see Beyster, The SAIC Solution. One of the defense secretary’s on its board was Robert Gates.

63Shorrock, Spies for Hire, 15, 281; Isenberg, Shadow Force, 115; Mark Benjamin and Michael Scherer, “The Abu Ghraib Files,” Salon, March 14, 2006; “Big Steve and Abu Ghraib,” Salon, March 16, 2006. CACI employee Daniel Johnson allegedly directed a subordinate to abuse detainees and “put his hand over the month of [an uncooperative prisoner] to stop his breathing.” The other main culprit “Big Steve” Stefanowicz allegedly gave orders to Charles Granger which led ultimately to Granger’s prosecution though he himself was never fired from CACI, or prosecuted by the DOJ. Armitage was a former CIA agent linked to covert operations in drugs in Indochina and Central Asia and illegal weapons transfers to the Contras while serving as Reagan’s assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security affairs. In 1984, he was investigated by the national commission on organized crime for links to gambling and prostitution.