Introduction by Caroline Norma

Translation by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen

Denigrating women who survived comfort station internment is critical to protecting the historical record of the Japanese military and the contemporary reputation of the Japanese government, as Nishino Rumiko and Nogawa Motokazu make clear in these two articles. They describe recent efforts from a range of quarters to ‘injure the victims all over again, rubbing salt in their wounds and violating their human rights’. Recent attacks on survivors include Japanese newspaper companies retracting and publicly disavowing reportage that uses the term ‘sexual slavery’, Japanese politicians equating the fabricated writings of a man (Yoshida Seiji) with the actual historical experience of female victims and the documentary record, and the prime minister tacitly suggesting that claims lodged by survivors in the international sphere hurt the feelings of the Japanese populous and damage its pride.

|

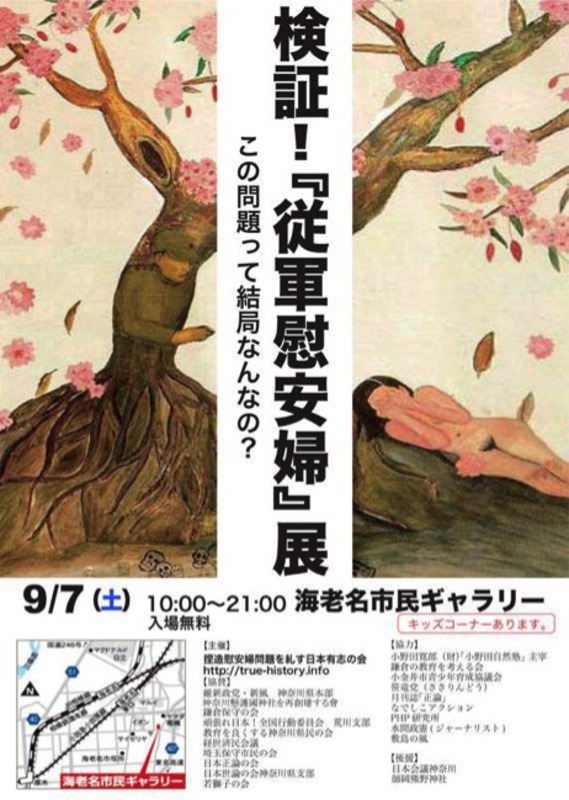

Advertisement for public information session denying the wartime history of military sexual slavery that uses the artwork of a Korean comfort station survivor |

A further strategy to discredit and disparage survivors was launched by Chief Cabinet Secretary SugaYoshihide; he defines the terms of historical violation so narrowly (i.e., as ‘kidnapping’) so as to preclude recognition of any individual’s actual experience of military sexual enslavement. Nishino sees this strategy as targeting survivors in that ‘it is the victims who were made into “comfort women” by the Japanese military who are being ignored in the campaigns that deny “coercion”‘. It is a strategy that historian Yoshimi Yoshiaki critiqued in 2013 in the following terms:

The comfort women system of the Japanese military has been defined as problematic only to the extent that any individual woman might have been forced into a comfort station. But regardless of the means by which women entered; for example, whether they sailed on a luxury liner and then boarded a limousine to arrive at a comfort station, and all the while fully consenting to this travel, the military cannot evade culpability if it forced a woman to enter into sexual relations with military men in a comfort station…and if we say that the comfort women system was a system of sexual slavery then we cannot concurrently say that women could have been exercising any choice in entering into sexual relations with the military men.1

|

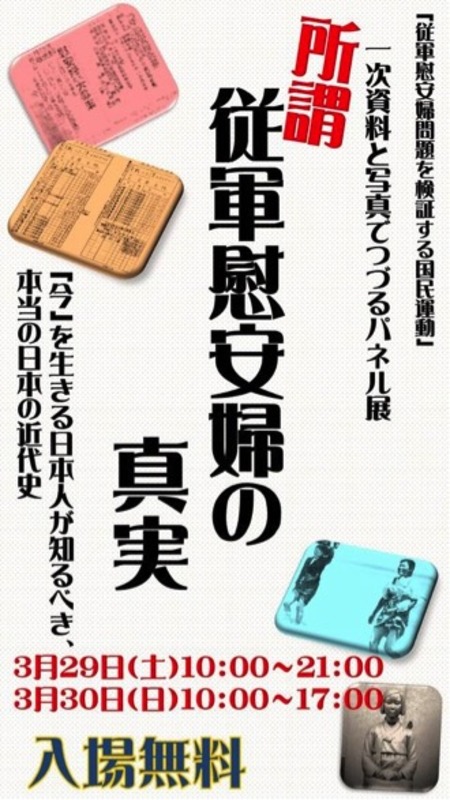

“Facts about the so-called comfort women: The facts about modern history that every Japanese person living in the here and now needs to know” |

Comfort station survivors and their public testimony documenting historical crimes of military sexual slavery pose an enduring problem for Japanese men. These women represent the sex crimes of men in the past, and serve as a reminder of what Japanese men continue to be capable of today. As Nishino writes of these men: ‘they want to fight another war’. They apparently can’t wait: even in these final years before we see the remaining survivors pass away, they are eager to discredit victim testimony as ‘unfounded defamation’, Nogawa notes. Not only survivors and their testimony; any trace of their existence is being erased. As Nogawa writes, a Ministry of Foreign Affairs website appeal for donations for survivors has been deleted, and the prime minister and his diplomats criticise the building of public monuments to the commemoration of victims anywhere in the world they arise. There are other examples of erasure efforts: moves are currently afoot to bring a petition to the Kyoto prefectural assembly that will overturn a resolution passed in 2013 that supports the ‘urgent redress of the history of the comfort women’. Notably, the original resolution was passed as a result of efforts by a cross-party group of women. Their joint achievement in advocating for survivors, too, is now under attack.

The stage is not well set for Prime Minster Abe’s upcoming obligations in 2015 to make public statements commemorating fifty years since the normalisation of Japan-South Korea relations and seventy years since the end of the Pacific War. He is unlikely to allow his statements to dwell on the past. This past features the pain and suffering of women and girls at the hands of the Japanese military, but also includes the achievements of feminists and other advocates in bringing international scrutiny and opprobrium to these men. Today, Prime Minister Abe and his supporters are banding together to erase not just the historical record of wrongdoing but the survivors and their supporters who continue to insist upon this record.

The current situation prompts Nishino to make the appeal that, ‘more than anything else we need to listen to the voices of the women victims, to find out what happened, to face their evidence’.The evidence we must face from survivors is damning of Japanese men who dominate the state and the military, both in the past and the present. With women pushed aside and victims done away with, a major obstacle to war-making is removed, and militarized activities of male bonding can proceed apace. If this masculinist-militarist agenda is to be derailed, the voices of survivors need to be amplified and elevated to the international sphere where Japanese efforts to silence their voices might be challenged by those without a shared interest in the contemporary project. The English translation of Nishino and Nogawa’s critiques provides a timely contribution to awareness raising among those outside Japan who might draw attention to continuing injustices perpetrated against comfort station victims and the responsibilities of the Japanese state toward them.

|

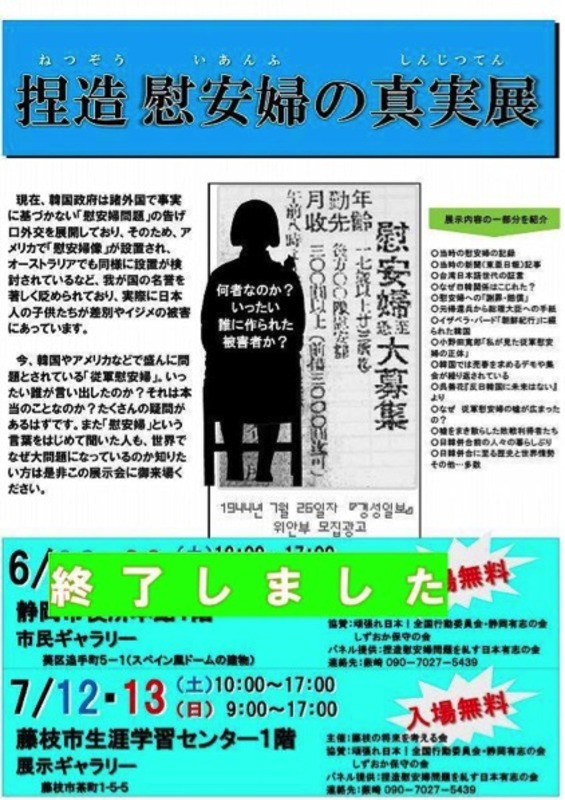

“Public information session on the facts of the fabricated comfort women” |

Caroline Norma is a lecturer in the School of Global, Urban and Social Studies at RMIT University, Australia. Her book, The Japanese comfort women and sexual slavery during the China and Pacific wars is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in 2015.

“Public information session on the facts of the fabricated comfort women”

“Facts about the so-called comfort women: The facts about modern history that every Japanese person living in the here and now needs to know”

Advertisement for public information session denying the wartime history of military sexual slavery that uses the artwork of a Korean comfort station survivor.

Notes

1 Yoshimi, 2013, p. 3「慰安婦」バッシングを越えて : 「河野談話」と日本の責任「戦争と女性への暴力」リサーチ・アクションセンター編,西野瑠美子, 金富子, 小野沢あかね責任編集「河野談話」をどう考えるか / 吉見義明

The Forgotten Victims in the “Asahi Bashing” Case

Nishino Rumiko

Translated by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen

A sense of crisis makes me dizzy as I witness the extreme critique of the Asahi Shimbun, which began with Asahi’s ‘correction’ of an article that examined the Japanese military ‘comfort women,’ and has seen the media’s inability to criticise the circumstances that have followed.

What has come under fire is Asahi’s retraction of its articles on Yoshida Seiji’s ‘testimony.’ Even though earlier examination of the process of the Kono Statement has made clear that Yoshida’s ‘testimony’ has nothing to do with the Kono Statement, perceptions still abound that falsely assume Yoshida’s ‘testimony’ to be the basis of ‘coercion’ in the Kono statement. In addition, [conservative] media such as Yomiuri, Sankei and some weekly magazines have launched huge media campaigns creating an impression that because Yoshida’s ‘testimony’ was a ‘lie’ there was no ‘forced removal’ of the ‘comfort women,’ some going as far as to say that the issue of Japanese military ‘comfort women’ itself does not exist. Such a situation cannot be overlooked.

There has been only limited opportunity for both older and younger generations to learn the facts of the ‘comfort women’ issue and see it from the perspective of human rights. This was apparent, for example, in the [Japanese media’s] reporting of the United Nations’ recommendations and the watering down of descriptions of ‘comfort women’ in school textbooks. In such an environment people are being exposed to advertisements for weekly magazines on trains and in newspaper that feed them with wrong-headed ideas, and public opinion that ‘after all, the ‘comfort women’ was a lie, and the Asahi Shimbun is ludicrous’ is taking form. What I find frustrating is the lack of media critique of this current situation.

Now is the Time to Recover Respect

In January 2001, when a TV programme ‘The Question of War-time Violence’ (the second episode of NHK’s ETV Series ‘How is War to be Judged?’) aired, the current Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who was then the Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary, and others intervened politically to alter its content. I remember vividly what happened then. At that time,the media were unable to challenge the injustice of the infringement on the freedom of the press. It seems that what we are witnessing now is an extension of what happened then.

This is something that applies to the Asahi bashing too, but it is the victims who were made into ‘comfort women’ by the Japanese military who are being ignored in the campaigns that deny ‘coercion’. What we should not forget in the ‘comfort women’ issue are the victims, and the recovery of respect for them. For that to happen, more than anything else we need to listen to the voices of the women victims, to find out what happened, to face their evidence. It is a mistake to consider documentary evidence as the only evidence.

But some Japanese media, far from facing the victims, continue to pour out articles that injure the victims all over again, rubbing salt in their wounds and violating their human rights. This is nothing but hate speech. What is important for the women who had been made into ‘comfort women’ is to recover ‘respect’ – not ‘honour.’ Prejudice based on the ideology of chastity under patriarchy forced upon them a long silence and even made them see themselves as ‘shameful women.’ The fear of social prejudice forced them to remain silent. Therefore their experience is not ‘dishonourable’. Rather, they are the victims of serious human rights violation.

The appearance and testimony of the victimised women were an attempt to recover ‘justice.’ Their demands for apology and compensation from the Japanese government, finding out the truth, receiving public recognition of the facts and seeing the public educated on such matters are all part of the process of the victimised women’s recovery from the damage. But the Japanese government has not tried to engage directly with the victims’ thoughts and feelings; this is expressed in its ignoring of an international organisation’s recommendations.

As recently as July this year, the UN Human Rights Committee published its ‘concluding observations’ in response to the Japanese government’s ‘periodic report.’ In the section ‘Sexual Slavery Against “Comfort Women”’ it sternly pointed out: ‘The Committee is concerned by the State’s contradictory position that the “comfort women” were not “forcibly relocated” by the Japanese military during wartime but at the same time that the “recruitment, transportation and management” of these women in comfort stations was done in many cases generally against their will through coercion and intimidation by the military or entities acting on behalf of the military.’

|

Radhika Coomaraswamy, former UN special rapporteur on violence against women and author of the first UN report dealing with the issue of the comfort women |

The UN Human Rights Commission has also made the following recommendations:

(i) that all allegations of sexual slavery or other human rights violations perpetrated by the Japanese military during wartime against the “comfort women”, are effectively, independently and impartially investigated and that perpetrators are prosecuted and, if found guilty, punished;

(ii) there should be access to justice and full reparation to victims and their families;

(iii) there should be the disclosure of all evidence available;

(iv) that education of students and the general public about the issue be conducted, including adequate references in textbooks;

(v) there should be a public apology and official recognition of the responsibility by the State;

(vi) there should be condemnation of any attempts to defame victims or to deny the events.

But even with these recommendations, the Japanese side at the UN Human Rights Commission still insisted that it would not accept the expression ‘sexual slavery.’ In an NHK programme aired on the 14th, Prime Minister Abe even stated that because of the Asahi Shimbun’s reporting ‘the whole world thinks that it is true that Japanese soldiers, like kidnappers, made women into comfort women; it is also a fact that monuments that criticise [Japan] have been made.’ However this is an extreme misunderstanding. It reveals the wide gap between human rights consciousness in Japan and in the international community.

The ‘coercion’ the international community refers to is not due to the ‘kidnapping’ that Abe talks of. Such ‘forced relocation’ was only a part of the coercion used in recruitment; and from the perspective of international treaties and criminal law of the time, both abduction and deception constituted criminal acts. If we were to limit our discussion to kidnapping and threats, the existence of such ‘forced recruitment’ has been confirmed in areas under Japanese military occupation in China, the Philippines, East Timor, Malaysia and Indonesia by testimonies of victims and witnesses, as well as in documents on BC war criminals. We should not reduce the ‘comfort women’ issue to simply a bilateral issue involving the ‘Korean comfort women.’ The ignoring of victims from different parts of Asia is clearly intentional.

Prime Minister Abe has not budged from his position that ‘in Japanese government documents there is no description that directly shows so-called ‘forced recruitment’ by the military or officials.’ But such evidence had been found in 1993 at the time of the Kono statement; since then more than 500 items on the ‘comfort women’ have been discovered. Yet the Japanese government refuses to recognise this, instead repeating the misunderstanding of 20 years ago – clearly to evade responsibility.

In the process of writing the Kono Statement, only 16 Korean women were interviewed; but the victims come from many regions, such as the Philippines, Taiwan, North Korea, Indonesia, East Timor, and Malaysia. As they are getting older we need to conduct interviews as soon as possible.

Why does the Abe government resist recognising the ‘forced recruitment’ of the ‘comfort women’ issue so much? With its hard-line stance on the reckless interpretation of collective self-defence, too, I cannot but think that they want to fight another war. Is that why they glorify war and reinterpret history to suit their purpose?

The victims have raised their voices also because they want to prevent another war, thinking there ‘should be no more victims like us’ and ‘war should never be repeated.’ That is why they demand truth, a clear apology, compensation and education.

We cannot let the ‘comfort women’ issue end while excluding the human rights perspective. To solve the issue without involving the victimised women themselves is not a true ‘solution.’

In this sense too, the distorted ‘Asahi bashing’ should not continue. How are we going to face this situation? Now, more than any other time, the quality of Japan’s democracy is being questioned.

Nishino Rumiko is a leading historian of the wartime comfort station system, and a core member of the Women’s Active Museum On War And Peace, the Violence Against Women in War Research Action Center (VAWW-RAC), and the Center for Research and Documentation on Japan’s War Responsibility (JWRC). Nishino also led efforts to organise the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slaveryin Tokyo in 2000. She travels all over Asia and the Pacific to speak with survivors and their representatives, and has published more than two decades’ of scholarship on the basis of detailed historical research and in-country fieldwork. This article was translated from Shukan Kin’yobi.

Translated by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen. Rumi Sakamoto is Senior Lecturer in the School of Asian Studies, the University of Auckland, New Zealand. She is the coeditor with Matthew Allen of Popular Culture, Globalization and Japan. They are both Asia-Pacific Journal contributing editors.

Recommended citation: Nishino Rumiko, “The Forgotten Victims in the “Asahi Bashing” Case,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 49, No. 2, December 22, 2014.

‘Scandalous Conduct of LDP and Rightists’: New Attack on the ‘Comfort Women’

Nogawa Motokazu

Translated by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen

The Abe Cabinet continues its attempts to distort the ‘comfort women’ issue, making the most of Asahi Shimbun’s 5th August retraction of its past articles that employed the late Yoshida Seiji’s ‘testimonies.’

On the day that the retraction took place, Ishiba Shigeru, the then secretary-general of the LDP, reacted quickly, commenting that ‘examination [of Asashi reporting] in the Diet may be necessary,’ which in turn suggested the possible summoning of Asahi Shimbun executives before the Diet.

Later in October, when the Sankei Shimbun Bureau Chief in Seoul was indicted for defaming President Park Geun-hye, there was much criticism of the Korean government’s attempt to use its authority to intervene in the media. However, we need to remember that the LDP’s former secretary-general had also made the above statement that could be taken as intimidation directed at news media.

I would also like to point out that the Ishiba statement set up an entirely different, politically motivated issue, namely, ‘How do we resolve the nation’s suffering and sadness?’ This has also become a pet phrase of Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. In an exclusive interview with the Yukan Fuji newspaper, Abe said that ‘[the ‘erroneous report’] made many people feel sad and suffer; it harmed Japan’s pride in the international community.’

|

Tadakazu Kimura, center, president of The Asahi Shimbun, and Nobuyuki Sugiura, executive editor, right, and Hisashi Yoshizono, director in charge of public affairs, left, apologize at a Sept. 11 news conference. (Shinichi Iizuka) |

On October 3rd, in the Budget Committee of the House of Representatives, Inada Tomomi, Chair of the LDP’s Policy Research Council said, ‘because of the Yoshida testimonies Japan’s honour has hit rock bottom’ and explained that she would set up a special committee to examine the influence of the Yoshida ‘testimonies.’ To this the prime minster responded: ‘many people are hurt and saddened, and Japan’s image has been seriously damaged.’ He went on to say, ‘unwarranted defamations are taking place throughout the world, and they are the products of erroneous reporting.’

However, as Shukan Kin’yobi has pointed out on many occasions, Asahi’s ‘erroneous report’ has had only marginal relevance to the understanding of the overall picture of the Japanese military ‘comfort women,’ and its influence on the international community is negligible.

‘Forced Relocation’ (Kyosei renko1) Did Take Place

From the Opposition parties, one of the first responses to the Asashi article came from Hashimoto Toru, the mayor of Osaka city. This is not surprising, considering that as the head of the former ‘Nippon ishin no kai (Japan Restoration Party)’ he had made a statement that Japanese military ‘comfort women’ were ‘necessary,’ sending his party into political decline.

In a press conference held in his office on August 8th he boasted that ‘if, in any small way, my previous comments had prompted (Asashi’s correction), then personally that’s more than I can hope for as a politician.’ Further, Mayor Hashimoto harshly criticised Asashi’s response that other newspapers also confused the ‘comfort women’ with teishintai (volunteer corps) or used the Yoshida ‘testimony’ in their reports, saying that ‘reading it [the Asahi response] I felt uncomfortable. They are justifying themselves.’

But didn’t mayor Hashimoto himself justify the Japanese military, by saying that women like the ‘comfort women’ also existed in other countries?

Yamada Hiroshi, a member of the House of Representatives and the secretary-general of Jisedai no to (The Party for Future Generations), a split-off party from Nippon ishin no kai, has for some time been demanding the retraction of the Kono Statement; but this time round he began to insist that it was problematic that Kono Yohei (the then Chief Cabinet Secretary) refered to ‘forced relocation’ in a press conference at the time of the Kono Statement (for example, Sankei October 20th).

On this point, the current Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide has also expressed his agreement in the House of Councillors Committee on Cabinet on the 21st October: ‘We reject that point [the reference to ‘forced relocation’ made by Mr. Kono, the former Chief Cabinet Secretary], and as the government, we have been making a strong appeal to restore honour and trust in Japan.’ This means that the denial of ‘forced relocation’ has become the government’s official position. The next morning, Chosun Online (the online site of the South Korean Chosun Daily) reported, ‘this is the first time that Mr Suga, the Chief Cabinet Secretary, clearly rejected the statement of the former Chief Cabinet Secretary, Mr. Kono.’ It is highly likely that this will stir up further concern outside Japan from now on.

However, the understanding of ‘forced relocation’ – not only among Japanese researchers and the advocacy organisations for the victims but from international perspectives too – does not rely on Yoshida’s ‘testimony,’ as ‘forced relocation’ refers to the sending of women to the ‘comfort stations’ against their will, either by deceiving them about the nature of their employment, coaxing them into cooperating, or simply through human trafficking. It is also clear that in areas under Japanese occupation there were cases of ‘forced relocation’ in the sense that Abe has used the term ‘kidnapping,’ where direct violence and threat were used.

The more the prime minister and the rightists insist on denying the ‘forced relocation,’ the more isolated they will become in the international community because of their distorted understanding of the ‘comfort women’ issue.

Prime Minister Abe, when he appeared on an NHK programme on September 14th, stated that because of the ‘erroneous report’ of Asashi Shimbun, the international community perceived it as a ‘fact’ that ‘Japanese soldiers went in people’s homes as if they were kidnappers, abducted children and made them into ‘comfort women,’ and that because of this, many monuments of the ‘comfort women’ have been erected in various places.’

Double Victimisation

However, it was not until October 2010, that is much later than the reporting of the Yoshida ‘testimonies,’ that the first ‘comfort women’ monument was erected in Palisades Park in the US. Ironically, this was prompted by the criticisms in the US of Mr. Abe’s 2007 statement during his first term as prime minister that ‘no document was found that confirms coercion in a narrow sense.’ Indeed, the word ‘abduct,’ which is used in the inscription on the monument is a verb that includes kidnapping victims by deception.

Also in 2007, while visiting the US, Mr. Abe was pressed on the issue of the ‘comfort women’ in a joint press conference with the then president George W. Bush, and responded: ‘I do have heartfelt sympathies that the people who had to serve as comfort women were placed in extreme hardships and had to suffer that sacrifice, and that I, as prime minister of Japan, express my apologies, and also express my apologies for the fact that they were placed in that sort of circumstance.’ But Mr. Abe now says that the ‘comfort women’ issue is ‘unfounded defamation.’ Is he still able to say today what he said seven years ago?

On the other hand, the government has already taken the first concrete step towards the denial of ‘forced removal.’ It was revealed that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had removed the ‘Appeal for Donations for the Asian Women’s Fund’ from the MOFA homepage. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga explained in a press conference on October 15th that the homepage was reorganised because it contained a mixture of government and non-government documents. But the removal was prompted by a question in the House of Representatives Budget Committee by the aforementioned Mr Yamada, a member of the House of Representatives, on the following phrase in the Appeal: ‘the act of forcing women, including teenagers, to serve the Japanese armed forces as ‘comfort women.’ The government’s intention is obvious.

In fact, the Press Secretary of the Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs has criticised the deletion in the Appeal, saying that it undermines the credibility of the Kono Statement.

The LDP’s move is even more blatant. The LDP Committee on Reevaluation of Global Information Strategy Headquarters for Regional Diplomatic and Economic Partnership (chair: Harada Yoshiaki) on September 19th adopted a resolution on the ‘comfort women.’ This resolution, which reads ‘the “forced relocation” of the so-called “comfort women” is rejected as a fact, and so is sexual abuse [italics by the author],’ not only denies the responsibility of the Japanese military but also rejects the violation of human rights at the ‘comfort stations’ itself. This is an extreme example of the type of absurd argument that reduces everything to having a basis in the ‘erroneous report’ of the Yoshida ‘testimonies.

In addition, the LDP’s Special Advisor to the President, Hagiugo Koichi, appeared on a TV programme on October 6th and said of the Kono Statement that, ‘while it will not be reviewed, announcing a new statement will make it irrelevant.’ But if the government produces a new statement with regressive content, such a statement will surely be regarded as a de facto rejection of the ‘Kono Statement’. There is no way they can avoid domestic and international criticisms if they act in such a dishonest manner.

These moves of the government and the ruling party not only prevent any improvement of Japan-Korea relations but also inflict a second victimisation on the victims of Japanese military’s wartime sexual slavery, who are still living in many parts of the world. We should never forget this.

Nogawa Motokazu is a lecturer in philosophy based at Kobe Gakuin University. His analyses of the history of Japanese war crimes and military sexual slavery are cited in the Japanese media and internationally. This article was translated from Shuka Kin’yobi. His twitter.

Translated by Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen. Rumi Sakamoto is Senior Lecturer in the School of Asian Studies, the University of Auckland, New Zealand. She is the coeditor with Matthew Allen of Popular Culture, Globalization and Japan. They are both Asia-Pacific Journal contributing editors.

Recommended citation: Nishino Rumiko and Nogawa Motokazu with an introduction by Caroline Norma, The Japanese State’s New Assault on the Victims of Wartime Sexual Slavery. The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 51, No. 2, December 22, 2014

1 Translators’ note: We have chosen to use ‘forced relocation’ as the English translation of the original term ‘kyosei renko’ in this article. For a detailed description of this phrase, see Yoshiko Nozaki’s ‘The “Comfort Women” Controversy: History and Testimony.’