Introduction

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11th, 2011, on my first visit that fall to the Rikuchū Coast of Iwate Prefecture, Japan, one of the first questions local residents asked me was, “Are you coming to the matsuri?”1 Three years and many subsequent visits later, this cheery inquiry, typically delivered upon my arrival – usually by friends but sometimes by strangers – has not changed. Initially, I was quite taken aback (even a little offended) by this seemingly trivial query, as enjoying a matsuri seemed contrary to my “more serious” purpose for being there – to clear tsunami debris, identify local residents’ needs, and to help clean up or rebuild their houses and schools as requested. But quickly, I came to realize the sincere intent of this question as I experienced how matsuri, often described in English as “folk festivals,” are taking on a special new meaning and significance for the residents of local communities on the tsunami ravaged Iwate coast. The study of matsuri in general has been a mainstay of Japanese ethnology and folklore studies during the pre and postwar periods, a literature and topic with which I am quite familiar (Yanagida 1946; Minakata 1951, and Miyamoto 1960). But never did I imagine that my own presence at a local matsuri in a coastal Iwate town post 3.11 would become such an important way to build mutual trust with coastal residents, delineate their most important priorities, or to learn about the powerful historical ties that bind these communities together. This experience contrasts sharply with the historical literature on matsuri such as is cited above, which has often focused on its inherent ritual and belief systems, and considered folk festivities to be a fairly static repository of the nation’s (and that particular region’s) historical beliefs and customs. While this monograph is informed by this heritage, my ethnographic experience in Iwate coastal communities post 3.11 reveals the more dynamic role of local folk festivities as espoused by contemporary Japanese ethnologists such as Shinno (1993), Iijima (2001), and Naito (2007), who conceive local matsuri to be fluid, malleable, reactive, and adaptive constructions – the products of historical precedents but also of contemporary social and cultural values that reveal and reflect the many ongoing sociocultural processes in that locale.

The following narrative draws from my personal experiences in Iwate Prefecture as a cultural anthropologist since 1988. This background, augmented by participation in tsunami relief efforts via ties with colleagues at Iwate Prefectural University (IPU) and contacts in the cities of Ōtsuchi, Yamada, and Miyako since 3.11, has given me insights into the cultural underpinnings of Rikuchū communities vital to consider as recovery efforts move forward. Portions of this account were logged during my second and third trips here as a tsunami fukkō shien (recovery support) volunteer in 2012 and 2013 (following a first outing in September of 2011)2 as part of a joint group of faculty, students, and staff from Ohio University (OHIO), where I am a faculty member, and IPU (Thompson 2012). Neither the tsunami relief trips nor access to the coastal matsuri described herein would have been possible without this institutional partnership (Ogawa, Kumamoto, and Thompson 2012). Ultimately, the purpose of this article is to focus a spotlight on tsunami survival on the Rikuchū Coast (see note 1) from a local point of view, using the unexpected insights regarding Rikuchū culture and matsuri there gleaned on these trips. For local residents here, matsuri are a highly valued and surprisingly dynamic medium of local expression that has historically proven sociocultural benefits and potential socioeconomic capabilities they don’t want to face the future without.

On The Way To Miyako

On the morning of Friday, September 21st, 2012, almost exactly one-year to the day of the 2011 OHIO-IPU Tsunami Recovery Support Volunteer tour, I sat with a new group of faculty and staff, again in the same 50-passenger bus filled to capacity, headed from Morioka – the prefectural capital – to Iwate’s Pacific coast.

|

A map showing the larger towns on the Rikuchū Coast of the Iwate Prefecture. |

The year before, we spent time in Ōtsuchi, near the city of Kamaishi in the south central quadrant of the Rikuchū region, at a kindergarten where we read kamishibai (picture panel stories) to 3-5 year-old tsunami survivors and cleared debris from an important local salmon stream. We had partnered on site with a nature preservation group from Nagano for the cleanup. At the farewell ceremony concluding the workday, both our parties were invited to a local matsuri (slated to begin that night) by members of the neighborhood association in Sakuragi-chō, the district in which we had worked. The invitation was sincere, and as leader I wanted to accept, but our group, pressed for time, was just not able to attend due to a commitment in another town two hours away. I will never forget the disappointed look on the chōnaikaichō-san’s (neighborhood association chairperson’s) face as we boarded our bus. I wasn’t quite sure why she looked this way, until moments later when we watched from the bus windows as our friends from Nagano became enthusiastically engaged in watching a fascinating folk performance (it was a shishi mai [lion dance]) by a troupe from Sakuragi-chō in the obviously enjoyable company of the local men and women (including the neighborhood association chairperson) we too had worked with there. It appeared that some of our Sakuragi-chō cohorts were actually dancers in the troupe! What fun! Everyone was joking and laughing as only those who spent the day working together could, and we were missing out! How meaningful the matsuri would have been! As we drove past the festival on our way out of town, it was now the occupants of my bus who looked disappointed.

In retrospect, not making time for the matsuri in Ōtsuchi had clearly been a mistake. The next day, when I shared this realization with Iwate folklorist Matsumoto Hiroaki, an IPU colleague, he smiled sympathetically and agreed that it would definitely have been an enjoyable experience.3 But more than that, he emphasized, this could have also been a good opportunity to build mutual trust with local leaders in preparation for future visits, as that was probably what they wanted most. “They’ll want you to come back,” he said. “This is the Rikuchū way.” Matsumoto sensei surmised that we could have also learned a lot more about local priorities for restoring Sakuragi-chō and the coastal community of Ōtsuchi as well, because the leaders would have been present. “The community leadership is always involved in the matsuri, especially on the Rikuchū Coast” he reminded me, “and some are even performers in the troupe, if you don’t see them helping with equipment or watching. And when leaders gather, they talk,” he added (Matsumoto 2013). My suspicion had been confirmed. At a time in the tsunami reconstruction process when well-meaning 3.11 relief volunteers from outside the Tōhoku region (northeastern Honshū) were being criticized for not being sensitive enough to local priorities (Okada 2012), this had been a missed opportunity.

These and other thoughts from conversations with Matsumoto sensei and others who know Rikuchū culture well echoed inside my head as our bus motored past the dense forest that stretches eastward on National Route 106 from Morioka to the Pacific coast. This year, we were headed first to the port city of Miyako (north of Ōtsuchi), for what was dubbed by IPU student leader Tanaka Kazuaki, as a series of “kokoro no kea~” (psychological and emotional care)4 opportunities. As Kazuaki, a social work major, explained, most of the rubble disposal was now at a stage best left to the specialists.5 In Miyako, the local disaster volunteer office had requested our services this time to meet with 3.11 survivors, especially the children and elderly, who continue to live in hundreds of temporary housing units distributed throughout the city. Our job would be to entertain them on Saturday, as on weekends the children have no school and need more excitement to keep their spirits up. Many seniors would also be interested in meeting with us, Kazuaki was told, as most didn’t have enough to keep them busy, even during the week. And we would be staying at Greenpia Sanriku Miyako, a resort hotel complex in the suburb of Tarō, that desperately needed the business from groups like ours to keep its bathing and laundry facilities open for use by tsunami victims living in a temporary housing village on the premises.

|

The 2012 OHIO-IPU Tsunami Recovery Support Volunteer group posing for a photo at the front entrance of Greepia Sanriku Miyako on September 21st. |

Our assistance was also sought at the Nanohana (Canola) Project, a local volunteer gardening group unable to afford the necessary labor for maintaining several hectares of rapeseed, planted to beautify the barren landscape left behind by the tsunami that struck there on 3.11. And finally, Kazuaki reported, we had been invited “again” to the annual Ōtsuchi Aki Matsuri (Fall Festival) held in the Kamichō and Sakuragi-chō neighborhoods our group had worked in the year before. “Being invited is quite an honor, especially this year, because it will be the last time this festival will be celebrated in its present location. Due to tsunami damage, a new city center is being built on higher ground. Next year’s festival will take place there.” Kazuaki then added:

I’m glad we accepted this year. I understand our group last year couldn’t stay for the shishi mai performance. As you know, the shishi mai troupe in Ōtsuchi is a local cultural treasure outsiders (even Japanese outsiders) are not often invited to watch. Even though I’m from Iwate, I’ve never seen it either, so I’m glad to get a chance with all of you. (Tanaka 2012)

Matsumoto sensei’s instincts had been correct. We would have another opportunity to become acquainted with Sakuragi-chō residents and their minzoku geinō tradition. This time I wanted to maximize the chance.

Feeling the enthusiasm reflected in Kazuaki’s voice, I thought about the research I had conducted over the past year to better understand the matsuri tradition on the Rikuchū Coast. This long and narrow track of land, which alternates between beaches and cliffs interspersed with fishing towns, that stretches from Kuji (a town north of Miyako on the Iwate–Akita boarder), to Ōfunato and Rikuzentakata (close to Miyagi on Iwate’s southern prefectural line), is indeed isolated. The rugged mountainous terrain, deep ravines, and lack of roads here greatly hampered rescue efforts from inland cities and towns following 3.11. In this part of the prefecture, Route 106 is the only direct road to Miyako and points north or south on the coast. From Morioka, the trip to Miyako alone takes a good two hours by car on a road that is only a modernized two-laner. Once out to the seashore, the Sanriku (coastal) Railway (a private line) used to be a good transportation option. However, since 3.11, sections of track are still washed out, making travel by train, interrupted by bus rides to forge the un-navigable sections of rail by coastal highway, inconvenient and slow. Full restoration of the sections that existed prior to 3.11 is expected by mid-April 2014. However, the Sanriku Railway doesn’t run at all between Kamaishi and Miyako. The degree of physical isolation here is difficult to comprehend until seeing it first-hand. But once on site, it becomes easier to grasp why, as locals claim, the Rikuchū coastline has its own distinct culture. Some might even describe it as a Japanese coastal Brigadoon. It is this very isolation that has historically had a profound effect on Miyako, the coastal economy here and on the Rikuchū region’s illustrious matsuri tradition.

A Brief Introduction to Miyako

The city of Miyako (population 55,000) is the largest of four major ports on Iwate’s Pacific coast. Most residents either fish for a living or reside in households that count on the fisheries industry for their main source of income (Miyako 2014). Located approximately midway between Kuji and Ofunato in north central Iwate, the waters off the coast of Miyako in general are known as one of the best fishing grounds in the world – where mackerel, tuna, and sea bream are plentiful. The fishing industry here has become increasingly competitive domestically and internationally during the postwar years, so consistently good catches have become hard to yield on a regular basis, resulting in inconsistent profit margins from year to year. Thus, individual incomes in the region and the ratio of jobs to qualified applicants have historically been much lower in Miyako and its vicinity than the prefectural average. As the region has tried to diversify its fishing and seafood industries, Miyako and Iwate’s coastal region as a whole had been enjoying some success in developing an expanded manufacturing base prior to 2011. This effort had produced a number of competitive companies in the electrical connectors, steel, and concrete industries. But the tsunami on 3.11 destroyed much of the infrastructure that supported this progress. Even while small scale fisheries and seafood cultivation have resumed on a limited scale since October 18th, 2013 in all sectors of the Sanriku coast (which includes the coastlines of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures), the difficulty of rebuilding needed replacement infrastructure quickly, compromised existing facilities, and ongoing environmental concerns – radiation leakage from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that flows directly into the air overhead and into the sea close by (though over 160 kilometers south of Miyako) – has seriously limited the productivity of both local agriculture and fisheries (NHK 2013d). In a nutshell, on 3.11, Miyako’s economy was dealt a devastating blow from which it may never fully recover.

3.11 Tsunami Damage to Businesses and Industry on the Rikuchū Coast

|

The main docks at the Port of Miyako, just beginning to be rebuilt, in September 2012. |

The extent of the tsunami damage in each Rikuchū community varied greatly at the city, town, and village levels (Tasso 2011). Yet, the detailed damage reports of individual townships are still being worked out. In the aftermath of 3.11, the prefectural authorities in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima collectively focused their initial assessments on the overall losses within several key business and industry-related categories agreed upon jointly (as opposed to estimating the damage in each town separately) as calculations began. These categories include agriculture, fisheries, forestry, manufacturing, commercial enterprises, and tourism, all for which general damage statistics are available. But not even the Miyako Higashi Nihon Daishinsai Fukkō Keikaku (Miyako Great East Japan Earthquake Reconstruction Plan), first issued in October of 2011 (Miyako 2011) lists the specific losses incurred in its own municipality. As a Miyako Town Hall official I spoke with explained, “The destruction was so bad across the region that individual damage tallies would have been a waste of time and practically meaningless for purposes of assessing the enormity of the loss.” (Kimura 2013) According to Iwate Prefectural sources, industrial damage to the prefectural coastline including the fishing industry totals at least ¥608.7 billion (at ¥80 to the US$), and losses to public works is estimated at ¥257.3 billion. As many viewers saw on network television, cable stations and on the Internet from many parts of the world, the destruction to most of the Sanriku coastal region was cataclysmic (Tasso 2013). Iwate prefecture alone lost 14,000 fishing boats and the use of 108 of it’s 111 fishing port facilities, completely shutting down the entire fisheries industry in northeast Japan until more than a year after the disaster (Samuels 2013).

As indicated below, even small and medium-sized communities in the northern portion of the Iwate coastline from Tanohata to Kamaishi essentially lost all of their coastal business capacity located near fishing docks and commercial piers, which typically form the hub of these townships. Their municipal buildings and residential areas – all of which are usually located in or very near these hubs – were also devastated. Important to remember also is that, in addition, Iwate’s coastal residents experienced major losses to the auxiliary industries that have traditionally supplemented their fisheries income and/or provided additional or alternative employment for members of their households. For example, agriculture experienced losses of ¥54.4 billion in farmland and ¥2.8 billion in facilities. Other losses included ¥25.0 billion in forestry, 89.0 billion in industrial manufacturing, ¥44.5 billion in commercial manufacturing, and ¥32.6 billion in tourism (Tasso 2011). In effect, the entire economic capacity in each of these communities was totally lost. Fortunately, however, in some regions of the Sanriku Coast, backland urban districts removed far enough from the seaside, survived. This has enabled many Rikuchū communities like Miyako to regroup slowly over time.

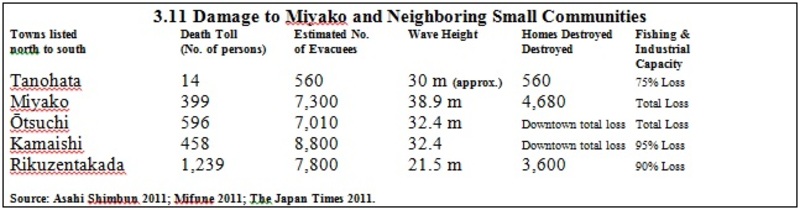

3.11 Damage to Miyako and Neighboring Small Communities on the Rikuchū Coast

The human toll caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake as of December, 2013 is now estimated at 15,833 dead, 2,364 missing, and 2,688 still unaccounted for. According to NHK, 3,825 of the dead, missing, and unaccounted for (or approximately 24%) were from the Iwate coastline alone (Asahi 2011; NHK 2013b). As the figures below demonstrate, Miyako did not have the highest death toll in Iwate’s mid-coastal region.

|

However, the earthquake (Magnitude 9.0)6 and resulting tsunami claimed thousands of residences and produced a large number of evacuees, seriously damaging the social stability and human resource capability of the town. The loss of Miyako’s industrial hardware and its displaced workforce following 3.11, coupled with its remote location, has hampered cleanup activities, even in the present, further slowing the recovery process. The coastal region’s net industrial production in 2008 was roughly 20% of Iwate Prefecture’s total output. At the end of 2013, it had only recovered to a mere 4% (IPBR 2011). It is important to note also, however, that the Rikuchū Coast was experiencing serious socioeconomic challenges even before 3.11. The tsunami devastation not only created new problems but exacerbated the historical factors contributing to the already delicate economy, lack of jobs, and population decline that has plagued the region well known and studied frequently during a majority of the postwar years (Bailey 1991).

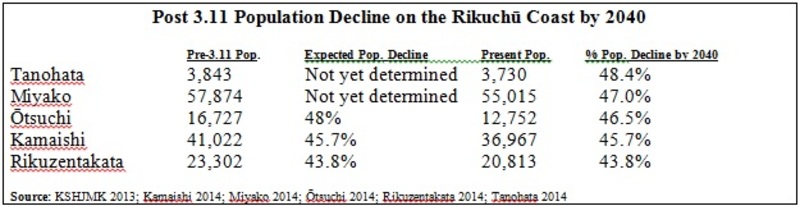

Post 3.11 Population Decline in the Rikuchū Region

To fully comprehend the post 3.11 Rikuchū socioeconomic predicament, it is also useful to consider Miyako’s post tsunami population losses in a broader national context. Japan’s population, which grew to almost 128 million in 2006, has now begun what a steady process of decline. With a population of just over 127 million in 2014, this figure is expected to fall to approximately 120 million by 2015, and dip under the 109 million mark by 2050 (Keizai Koho Center 2014). The aging of the general population (Japan has the world’s oldest population, currently with a median age of 46 and a life expectancy of 84) is one major contributing factor. By 2040, 36.1% of residents are expected to be over the age of 60 (as compared to 13.1% in 2010). The deaths that will increase as a result, the declining fertility rate (currently 1.4%)7 and a variety of societal factors such as more men and women choosing not to marry, and the lack of available marriage partners in some parts of the country, also contribute to the population’s downward spiral (Pearce 2014). In Japan’s six Tōhoku prefectures (from north to south: Aomori, Akita, Yamagata, Iwate, Miyagi, Fukushima, and Niigata), these factors become magnified, combining to account for 16.2% of the nation’s overall population decline in 2013 alone (Pearce 2014; NHK 2013a).

The magnification of the Tōhoku region’s population decline during Japan’s postwar period can be attributed to several endemic factors. These include postwar outflow of young people (ages 16-40) from the region in the 1960s and 1970s to the Tokyo-Osaka corridor for employment, and socioeconomic decline caused by the nation’s changing agricultural policies (gentan [hectare reduction] and tensaku [crop rotation] restrictions on rice) in the 1980s and 1990s which made farming less and less lucrative. (Bailey 1991). Furthermore, the State’s continual cuts to regional subsidy funding during the 1990s and 2000s never allowed Tōhoku’s local economy to recover, resulting ultimately in the Heisei Dai Gappei (the Heisei Era Great Consolidation) (Thompson 2008). Most recently, population in Rikuchū communities continues to decline due to post 3.11 deaths, movement out of the area associated with the shortage of sufficient long-term housing, untenable professions resulting from infrastructural impairment, and the lack of replacement jobs have reduced local populations even further (Pearce 2014; NHK 2013a), producing the figures shown in the graphic below. Due to the combined factors aforementioned, according to the Kokuritsu Shakai Hoshō Jinkō Mondai Kenkyūsho (the [Japan] National Social Security Population Problem Research Institute), by 2040, the Iwate municipalities in the tsunami zone listed below are among the Sanriku coastal towns expected to experience levels of population decline even more drastic than in other parts of the Tōhoku region. Miyako and several of its neighbors are in this group.

|

Japanese demographic specialists such as Professor Emeritus Matsutani Akihiro of the Seisaku Kenkyu Daigaku Daigakuin (the [Japan] National Graduate Institute For Policy Studies) emphasize that depopulation is not just a regional anomaly, and believes that municipalities across Japan (not just those on the Sanriku Coast directly affected by the 3.11 disaster), need to prepare now to meet the social and financial adjustments that will quickly become necessary at the local level as population decline accelerates. He warns that because of the nation’s changing demographic trends and the strong future likelihood of natural disasters in many parts of Japan, ALL municipalities nationwide (not just Sanriku coastal communities) need to speed up their planning for new, different, and innovative ways to utilize the untapped ideas and resources that will enable local areas to continue the income generation necessary for maintaining health care and public services at necessary levels – even if it means combining public and private sector capabilities or trying something completely new (NHK 2013a). On the Rikuchū Coast, the local matsuri culture may offer depopulated municipalities here just this kind of unique opportunity.

Matsuri On the Rikuchū Coast

Much has been written about pre- and postwar matsuri culture in mainstream Japan (Ya-nagida 1946; Miyamoto 1960; Robertson 1991; Ashkenazi 1993). In many modern Japanese cities and towns, a “matsuri” has come to mean a large-scale public festival or celebration, often, but not always, based on a traditional theme. Most rural and urban municipalities have some kind of matsuri during their annual event cycle, typically involving the activation of a deity at a local shrine or temple, a parade with dashi (floats), and/ or folk dancing – these varieties being the national default archetypes. The Tōhoku region itself boasts many well-known summer festivals of this variety, such as the Nebuta Matsuri in Aomori, the Kanto Matsuri in Akita, the Hanagasa Matsuri in Yamagata, and the Sansa Matsuri in Morioka (capital of Iwate), all of which take place in August. But these examples do not adequately represent what Rikuchū residents mean by the term. This kind of annual, regionally (and often even nationally) promoted variety of seasonal festival, sometimes referred to as shimin matsuri (citizens’ matsuri), the focus of much contemporary matsuri-related scholarship, tends to take place in urban or suburban areas around the country and be sponsored by local shrine and/or temple parishes in conjunction with city hall.

Shimin matsuri typically represent the unique aspects of their communities for the purpose of inducing positive associations to well-known regional history, culture and traditions. They are often used by their sponsors as a tool to construct meaningful memories for local residents that deepen their sense of belonging to that locale and promote the region’s customs and traditions. This emphasis attracts local and regional visitors and tourists from away to the area during festival time to watch and even partake in the festivities (Robertson, 1991; Kuraishi 1997). Unlike local folk festivals on the Rikuchū Coast, many of which are hundreds of years old, many shimin matsuri (not all) were created in the postwar period and don’t have histories of more than 50 or 60 years. Some are even more recent constructions. The performers are often a mixture of locals and visitors who sign up to participate, mostly for fun, and are not necessarily dedicated to or even regular practitioners of the folk arts they join in on for the festival during other seasons of the year. In this way, shimin matsuri are typically folk celebrations focusing on the mainstream culture of the city, prefecture, or region where it is being celebrated and designed for public consumption, not engaged in for religious fulfillment, family pride, out of respect for ancestors, or as a tribute to area precursors.

|

A Kuromori Kagura performance at Yokoyama Hachimangū (Shrine) in Miyako in September, 2013. The troupe performed to an audience of 6 members who can be seen sitting behind the performers to the right. |

However, off the beaten path, in most rural areas of Japan (especially in the nation’s periphery), local matsuri are not so public, are much more personal, and take on a variety of locally prescribed forms. They are usually associated closely with local folk traditions and beliefs at the village or hamlet level, and are often private events open only to locals or those to whom access is offered. Typically small in scale (there may be as few as 5 or 10 in the audience at an event), very little literature is available, particularly in English, on folk gatherings such as these that can still be found on the Rikuchū Coast and in other rural or isolated regions of Japan, which are often known about and documented only locally. This kind of matsuri, which sometimes, but not always, takes place at a shrine or temple compound, features a minzoku geinō (traditional folk art) performance as its main attraction, designed either to express respect for local history and tradition, to activate the local deities and spirits, to entertain them, or for all three purposes (Thornbury 1997).

The study of minzoku geinō has historically been the focus of rural sociologists and ethnographers in the Japanese minzokugaku (folklore studies) tradition, a genre that is associated closely with a community’s traditional livelihood, folk beliefs, values, and history. This kind of minzoku geinō is performed and perpetuated mainly for local consumption at local matsuri venues unless the troupe is invited to appear otherwise by special invitation at some other event. Minzoku geinō performers tend to be individuals who were born in or are closely associated with the community from which their performance genre originates. Many are parishioners by birth of their performance tradition’s home temple or shrine. They have committed their time and skills to the troupe by choice or family expectation, and devote themselves as amateurs to the perfection of the art form as a proud cultural expression of their local community, performing for as long as they are physically able. Some troupe members dance for personal religious reasons. Many enjoy the artistic and athletic challenge. (Some dances are physically strenuous.) But most performers are regarded as local heroes regardless of their skill level, just for their commitment to upholding the local tradition. Dancers are usually men, but due to population decline in Japan during recent times, women are now fairly common in all minzoku geinō nationwide.

|

A shishi mai (lion dance) performance at the Ōtsuchi Aki Matsuri (Fall Festival) in September, 2012. |

Troupe members in the most prestigious traditions are expected to perform at the regular observances all-year-around, plus make themselves available for any extra bookings throughout the year. Performers are never paid, but public performances of the well-known troupes elicit “ohana” – gift money, used to cover expenses related to the performance including equipment upkeep, plus a little extra. The most prestigious troupes have an uninterrupted performance history lasting (in some cases) hundreds of years (Yanagida 1946). Minzokugaku scholars suggest that studying the long-term social cohesion of troupes with the longest performance histories (the way in which troupes are integrated into their local communities, maintain their memberships, divide responsibilities, and recruit and train dancers) provides one of the few remaining windows, through which to observe the foundations of Japanese culture and society that form the essence of Japaneseness – basic elements of Japanese psychosocial behavior that have remained remarkably constant over time (Kuraishi 1997).8

When Iwate coastline locals ask, Omatsuri ni kimasuka? (“Are you coming to a/ the [depending on context] matsuri?”), MOST LIKELY, this question is actually an invitation to a minzoku geinō performance (possibly one taking place in the interlocutor’s very own hamlet), known to be occurring sometime while you’re in the area but not widely advertised; an event like the “matsuri” at the Sakuragi-chō shrine festival described earlier. “Matsuri” in this sense, means a folk performance – a music, dance, or drama presentation by practiced (and often highly skilled) amateurs that is held locally for local residents by local residents.9 On the Rikuchū Coast, folk performances of this type occur on a monthly (sometimes even a weekly) basis throughout the year at shrines, temples, and local kōminkan (citizens meeting halls), sometimes in conjunction with a local deity but even for commercial purposes in both public and secular performance spaces – often in private homes. Troupes perform individually, paired with other local multiple genre formats. But regardless of the venue or the purpose of a performance, for the performer and the local audience, each minzoku geinō exhibition is a demonstration and reaffirmation of locally shared cultural values, traditions, and a history of which only they are fully aware. One’s presence at a performance demonstrates publically not only support for a troupe, but ties that individual geographically to a coastal community and lifestyle, a local cultural and political leadership, and in some cases even a local deity (Thornbury 1997). In an age when 3.11 has accelerated depopulation, aging, and socioeconomic decline in the region, my observation has been that minzoku geinō troupes and their home communities have become more open than ever to outside guests and are an affiliation to local Rikuchū culture most locals have become happy and proud to share with outsiders. Historically speaking, this has usually NOT been the case (Yanagida 1946).

Iwate ethnologist Neko Hideo explains this newfound desire of locals on the Rikuchū Coast to share their local culture with people and institutions outside the region as a psycho-emotional response to the multiple disaster. He suggests that matsuri, and particularly the regionally and locally distinct minzoku geinō traditions that are a centerpiece of these events, give local residents something they can be proud of from their coastal lifestyle to show the rest of Japan and the world that has not been lost to the tsunami, the continuing earthquakes and aftershocks, or to the radiation levels which still sometimes register too high. The way in which folk traditions are transmitted here – mostly through experiential means learnable only by those who live or grow up in the area, makes this specialized knowledge and life experience particularly meaningful and valuable to them now – especially after all they have lost. And sharing this tradition with individuals and groups from outside the region who can enjoy it with them makes for a meaningful relationship-building experience, often culminating in the cultivation of a mutual trust, a better understanding of each other’s ways, and a bonding experience sometimes even resulting in long-term ties (Neko 2013). As many scholars have noted, the residents of Iwate’s periphery have needed these kinds of connections for economic reasons for a majority of the postwar period, not just since 3.11 (Thompson 2003). However, the 3.11 disaster has provided a new wave of opportunities (which until now have been few and far between) to broaden their sociocultural and socioeconomic networks by putting them in touch with people and organizations from other regions of Japan and around the world they might never have otherwise met.

Neko thinks this kind of bonding is particularly important in the post 3.11 context to counter what local residents on the Rikuchū Coast feel towards the disaster recovery process; that support personnel and organizations often don’t seem to think its important to understand (or even try to understand) their local culture, points of view, or needs, in order to help them (Neko 2013). This has been my observation as well. During my 2011, 2012, and 2013 Tsunami Volunteer visits, locals seemed to feel that plans developed elsewhere without their input to aid in their recovery, moved ahead on schedules they knew nothing about. Several locals I spoke with claimed that this made them feel as though they were thought of as ignorant, unsophisticated people unable to help themselves and gave them a sense that they didn’t have any control modesover the details of their own recovery (Ito 2012; Kanayama 2012; Kariya 2012).

Neko suggests that spending time together with tsunami relief personnel at a local folk performance event gives Rikuchū locals the ability to bridge this perceived gap in understanding on their own terms moving forward by giving them a chance to share their local knowledge with outsiders in ways that they can control. Neko argues that for these reasons, for both folk performers and the local audience, minzoku geinō has become the context in which, at least at present, many residents on the Rikuchū Coast feel most comfortable in representing themselves (Neko 2013). “I feel proudest of myself and my hometown when I am dancing,” said one minzoku geinō performer I spoke with in Miyako. “Very few people can do what I do!” (Onodera 2013).

Minzoku Geinō on the Rikuchū Coast

Aided by the region’s geographical isolation, even in the modern era, the Rikuchū Coast has maintained a particularly rich array of minzoku geinō traditions. Local performances of the tora mai (tiger dance), shishi mai (the lion dance as in Sakuragi-chō – but other communities have troupes as well), and oni kenbai (demon dance using swords) are common. Shishi odori (deer dance), teodori (local folk dance[s] with complex hand movements full of symbolism and meaning) and countless other named, hamlet specific agriculture and fisheries-lifestyle-related performance traditions are also prevalent. Interestingly, these local performance groups have a community maintenance function beyond machizukuri (town building – population maintenance) and quality of life issues that often goes unrecognized. Minzoku geinō helps to preserve local history, perpetuate the social and cultural ties between other neighboring communities with folk performance traditions from the same era, and captures within their repertoires the collective wisdom of the communities they have served. Even today, active troupes draft popular and professionally successful local residents and those with relevant special skills as leaders, they maintain support organizations that make the performances possible, and actively recruit performers from outside their towns using these connections, some of which were originally established hundreds of years eaarlier. These practices cut across shrine and temple parish boundaries, and family, neighborhood, and hamlet organization, solidifying local social, political and economic relationships in quite complex ways.

It is these local ties and this local culture, established, maintained, and supported historically through the Rikuchū folk performance community and the customs and lifestyle associated with them, that many local observers such as Matsumoto, Neko, Kariya (who will be discussed later) and Ueda (quoted below) – specialists of Iwate’s history and culture, all of whom are Iwate-based educators, two of whom are Miyako residents, and two who have Rikuchū business interests – feel could and should be used more effectively during this current post-tsunami recovery period for the good of the region. More specifically, the proponents of this perspective think that the Rikuchū folk heritage should be used more aggressively by town hall and the local board of education leaders to reinforce regional unity, solidarity, and even for modest economic development purposes while waiting on the large scale reconstruction measures being planned and implemented by the prefecture, the State and public and private agencies (some of which will not benefit residents for five more years)10 to take effect (Matsumoto 2013; Neko 2013; Kariya 2013; Ueda 2013).

Ueda Masahiro, Dean of IPU’s Miyako campus, a management professor, and director of this university’s Regional Manufacturing Research Center charged with finding ways to help Miyako’s devastated manufacturing and fisheries industries to recover, explains:

People in Miyako don’t have much hope right now. Jobs and housing are our two biggest problems. The city government says public housing is 3-5 years away. Those who want to build themselves on affordable high ground may have to wait 5 years or more for land to be cleared. The city doesn’t know how long creating new jobs will take. For both jobs and housing, this is much too long! Finding ways to maintain our fighting spirit is a third priority. Our infrastructure is still broken so there is very little employment. Without employment, without permanent places to live, and without ways to energize our spirit, young people and their families will continue to move away, leaving only the elderly. But the elderly know our history. Our city and our region have a rich folk tradition to draw on. The elderly can help us capitalize on that. We need our local matsuri and minzoku geinō traditions to return to full activity. For the vitality they bring, the youth they require, community organization they facilitate, for the local identity they preserve, and even for the commercial potential they have, our folk traditions are among our only remaining local assets that are immediately usable! (Ueda 2012)

Community Development In Iwate Using Local Cultural Assets

As scholars familiar with Japanese community development literature and the sociology of regional Japan know well, local residents in Iwate already have quite a history of utilizing local traditional social and cultural networks to attract outside interests for producing small-scale economic opportunities where they live. In many of these cases, economic development becomes possible, not necessarily by selling the local culture itself (though, for example, local folk matsuri do have the capacity to generate some revenue), but by local leaders using local cultural capital as a means by which to establish friendships with those outside the community that help them to bypass regional, prefectural, and even national bureaucratic structures that hold back local progress, enabling them to cultivate local economic opportunity directly with potential consumers there by themselves. This is the model and how it works. Outsiders from an economically prosperous city (such as Tokyo) are introduced to the local people and culture in a remote area of Japan, in the hopes that they will develop an interest in both. The outsiders arrange to visit the remote area. During the visit, locals use their hometown networks to give the outsiders a detailed inside view of their cultural capital – customs, traditions and local food or other products that are unique to the area and which may have marketing potential. The outsiders, impressed with the quality of the experience and sincerity of the people, reciprocate the inside view by providing access to their own networks and contacts in the city, that would not otherwise have been accessible from the remote locale to market the cultural capital introduced during the visit. Finally, the outsiders and locals develop regular long-term cultural and economic interaction in areas of mutual interest, resulting in the enrichment of both communities. At least this is the ideal outcome of this local economic development model (Thompson 2003).

Several Iwate communities already have experience with this approach. In inland Iwate, the ways in which townships such as Hiraizumi (which has emphasized its World Heritage sites such as Chūsonji and Mōtsūji temples)11 and Tōno (of Yanagida Kunio fame)12 have capitalized on their local cultural heritage to promote local economic development on a large-scale by attracting cultural and business ties using personal networks from Japan’s largest cities and many countries around the world are well known. On Iwate’s Pacific coast, the late Jackson Bailey’s work in the village of Tanohata (just north of Miyako), for example, shows how during Japan’s postwar period, local Mayor Hayano Sempei was able to fund local infrastructural development, international education, and local business development opportunities through state and private sector ties he established in person directly in Tokyo (bypassing the Iwate Prefectural government) through friendships at Waseda University and with Bailey himself. These contacts gave the Mayor access to individuals and institutions in his nation’s capital and in the United States interested in involving themselves with Rikuchū culture and life, which led ultimately to Tanohata’s economic advancement (Bailey 1991).

Combining regional municipal resources to attract business from the city to the periphery is another variation of the local economic development model. The case of local economic development in Tōwa-chō, another small inland Iwate town, during the 1980s and 1990s, is also instructive in this regard. Inspired by Hayano, local mayor Obara Hideo utilized state funding from the furusato sōsei undō (Movement to create hometown identity) and chihō kōfu zei (provincial support funds which paid regional towns subsidies based on local population figures) to join forces with three other towns in Japan with the same name to open a Tōwa Tokyo Office.13 Through this office, each municipal partner marketed its own local agricultural products directly to consumers in the Tokyo metropolitan area (Thompson 2003; 2004). For Iwate Tōwa, this eventually resulted in an “Antenna Shop” in Kawasaki (a suburb of Tokyo) which housed a grocery store that sold Tōwa’s local products, a restaurant that served Tōwa’s local dishes, meeting space where art classes promoting Tōwa crafts were taught, and where periodic tours to Tōwa were promoted, organized and launched in coordination with the Tōwa Town Hall and the folk culture based social and cultural networks back home (Thompson 2004).

Kamaishi (a coastal town south of Miyako referred to earlier in the population decline data) also has a history of approaching local development in similar ways, most recently detailed in a four-volume book series about the study of hope in Kamaishi by Genda Yuji and Nakamura Naofumi of Tokyo University, published in 2009. These volumes highlight Kamaishi’s various self-initiated economic development projects. Similarly, the city of Miyako itself has experience with this approach on a smaller scale as demonstrated by its manju (sweet cake) production and sales collaboration with Miyakojima City in Okinawa (Miyakojima-shi in Miyakojima) that dates back to a friendship between residents in these two cities that began in the early 1980s. Also, the use of the Sanriku Railway in the recent NHK asa-dora (morning [15 minute] drama) ‘Amachan’ to promote its reconstruction coastal tourism is well-known (NHK 2014). With no other realistic short-term economic options to rely on for income generation, a growing number of Rikuchū residents I’ve spoken with think it’s time to bring this kind of creative thinking back using some of Rikuchū Iwate’s folk culture assets, for which Miyako is the hub (Ito 2013; Kariya 2013; Neko 2013; Ueda 2013).

As an 80 year-old male owner of a ryokan (traditional Japanese inn) in Miyako that has been in operation for over 150 years suggested:

Our local cultural history and in particular, our minzoku geinō tradition and associated lifestyle, is one of our greatest hidden treasures. It’s a wonder we haven’t utilized it seriously for economic development before! Not many outsiders know about our Kuromori Kagura tradition. We need to bring in some young people with some PR savvy to help us market our local traditions like this to the mass market. The manufacturing and fishing industries may come back slowly over time, but will take a lot of financial support. But tourism development focusing on our local folk traditions and even our tsunami story could happen fairly quickly and inexpensively. Its already all here. I could even offer my inn (which survived 3.11 because of its location on a hill) as a historical place to stay, as it dates back to the end of the Meiji Period (the early 1900s)!14 This would certainly help fill my rooms. This would enable us to establish a more stable economic base in Miyako quickly! (Matsuda 2013)

When asked what approach she would like to see used to help the Rikuchū coastal communities recover socially, culturally, and economically from the 3.11 disaster, a 60 year-old veteran employee of a canning operation in Otsuchi destroyed by the tsunami volunteered:

Building back what we had won’t do much good. The fisheries didn’t really work that well before. We need to try something different… Something we haven’t attempted before. Besides the beauty of our coastline and our delicious seafood, our local assets include our ability to adopt ideas from the past and apply them to the present, our creativity, our perseverance, and our minzoku geinō tradition, which embodies all of these qualities. Maybe it’s time to ask our relatives who relocated to Tokyo and Osaka in the 1970s and 1980s – and since the tsunami this time – to help us bring in customers from central Japan to eat seafood and watch our Kuromori Kagura performances and events. (Kumagai 2013).

However, a male 73 year-old shrine association administrator in Miyako felt more protective of his local traditions. “I don’t think we should sell our local culture to tourists,” he said. “I’m sure that there are others in this town that value the privacy and integrity of not using our religious and folk traditions for commercial purposes.” (Kuwahara 2012).

These comments were interesting, particularly in light of the festival banners I noticed lining the edge of the hundreds of steps that lead up from the main road in Miyako to Yokoyama Hachimangū (Shrine), constructed on top of a hill. During a matsuri procession I observed in early September of 2013, clearly marked on each festival banner was the name of a local corporate sponsor, which was probably also a corporate patron of the shrine association promoting the event. Ties between the local shrine and the business community were clearly already in existence.

From the perspective of scholars familiar with public sector local development in Japan, the study of how residents in the remote outposts like the Rikuchū Coast might utilize local cultural assets and existing networks of social relations for economic development has long been a domestic field of study. Harnessing local cultural and economic assets using approaches such as Jimotogaku (hometown studies), and chiiki gaku (local region studies), first began to garner national attention in the 1980s and 1990s in the social education (shakai kyōiku) and lifelong learning (shōgai gakushū) divisions of town halls in peripheral areas all across the nation and have continued to remain popular (Okamoto 1989; Yoshimoto 2001; Yuki 2001). But these approaches, which advocate using local public institutional resources to activate private sector ties, have yet to be utilized to full potential where they may be needed most. However, where these hometown development ideas have been implemented, examples of success stories abound, not just in northeast Japan.

The way in which the village of Asuke in the mountains of Aichi Prefecture (in central Japan near Nagoya) achieved successful local economic development through its creation of Asuke Yashiki (Asuke Homestead), a working historical mountain farm using local expertise and connections in Nagoya is a famous example of “jisaku shuen” ([an economic development plan] “created and starred in by one’s self”). This is a technique in which a locally identified asset is defined as being valuable and becomes the focus of an economic development plan that features it as its centerpiece. The media is then mobilized to cover the event, providing the advertising and public exposure that makes it popular. (Thompson 2009). This approach, which requires only public sector support at the outset, is well suited to Miyako’s current predicament, but requires the cooperation of the local town hall.

As a town hall employee in Ōtsuchi mused: “Remember that former mayor of Asuke named Ozawa Shōichi in Aichi Prefecture who became chairman of the local tourism board after he retired? He was in the papers quite a lot back in the 1980s.” (Kino 2013) Kino continued:

Chairman Ozawa recreated, in Asuke, a working mountain homestead typical in the area during the Edo period (1603-1867) using traditional materials and building methods, through which to market local agricultural products directly to customers in Nagoya without middlemen. Customers were willing to travel from Nagoya all the way to Asuke, which has no train service, because they were able to purchase high quality specially made tofu, bamboo delicacies, and soba (buckwheat noodles) and actually get to know the farmers whose rice and mountain vegetables they regularly purchased at the homestead store. Ozawa even introduced Asuke‘s historical local craft and folk traditions to visitors in venues he created within the homestead compound during their stay. Visitors could even take lessons, spend the night, and learn more about traditional approaches to living a healthy lifestyle at special rates in the local inns that served traditional local dishes using the same ingredients. He regularly invited the regional and national media to cover and report on it all, putting the town on the map! Ozawa prolonged Asuke‘s economic independence for a good five years before the inevitable consolidation into Toyota City, but his ideas worked and Asuke Yashiki is still going strong! It all started when a friend of Ozawa’s from Toyota City expressed interest in Asuke culture. We need to try something ingenious like this in Miyako right now! Maybe Kuromori Kagura could be the focus of some kind of similar jisaku shuen approach! (Kino 2013).

Miyako and Kuromori Kagura

The OHIO-IPU bus arrived in Miyako in the early afternoon. Our first stop was at Miyako Tanki Daigaku (Miyako Junior College), or Miyatan, as locals call it, part of the IPU branch campus system, where we received a brief update on Miyako’s post tsunami prognosis from Dean Ueda (cited previously), our official host. It is no surprise to Matsumoto sensei that Dean Ueda and others in the region consider local minzoku geinō to be an important local asset that can help Rikuchū residents through the tsunami recovery process culturally and economically (Matsumoto 2013). After all, Rikuchū residents have a long history of drawing on their folk traditions for mourning, inspiration, guidance, and protection whenever a natural disaster has devastated the area (Kanda 2008; Hayashi 2012). There have been three tsunami here just in the last one hundred years (Dengler and Smits 2011).15 Historically, the minzoku geinō network that binds the folk traditions together on the Rikuchū Coast has a system of sharing the region’s resources with the communities that needed it most. The hub of this system is the Kuromori Kagura tradition headquartered in Miyako.

Takeda Junichi, a 45 year-old Miyako small business (liquor store) owner and Rikuchū minzoku geinō supporter, was very clear why Kuromori Kagura is a cultural asset with great jusaku shuen potential. “I believe,” said Takeda, “Kuromori Kagura has great potential for tourism both culturally from a minzoku geinō perspective, and from an economic standpoint. Rikuchū food culture, folk traditions, and the Kuromori Kagura style integration of coastal customs and matsuri would probably interest a lot of people in Morioka, Sendai (Miyagi prefecture) and Tokyo!” (Takeda 2013)

Arihara Hiroshi, a member of the Miyako-shi Seikatsu Fukkō Shien Senta ([the] Miyako [Daily] Life Revitalization Support Center) agreed. “Kuromori Kagura is definitely an underutilized resource for cultural outreach and economic development on the Rikuchū Coast.” (Arihara 2013) Arihara thinks the Miyako Town Hall should utilize their Tokyo connections and media ties to bring tourists in.

Similarly, “There are many aspects of the Kuromori tradition that would be impressive not just to folk religion scholars,” says Neko, “but also to the general public.

Fans of folk culture, or people just interested in the history and lifestyle associated with agriculture and the fishing industry anywhere would be fascinated with Kuromori Kagura, its rituals, it’s practices and how it is connected to the folk performance traditions on the Rikuchū Coast. But many Japanese outside the region and even inside the region didn’t even know of its existence until 3.11, and still don’t know much about it. Kuromori Kagura should be used at this point in time more deliberately for economic development as the ultimate purpose of any folk tradition is to help its constituents! (Neko 2003)

Kuromori Kagura, a major Shinto shamanic dance tradition based in Miyako, has indeed played a major role over the centuries in facilitating the welfare of local residents on the Rikuchū Coast socially, culturally, and economically, though not yet commercially. Technically it is a folk religion that evolved out of the shugendō tradition (mountain aestheticism derived from esoteric Shingon and Tendai Buddhism) and has served as the overall organizational catalyst of Rikuchū folk culture and has been a highly respected symbol of the Rikuchū lifestyle for over six hundred years (since the 3rd year Ōan [1370]) (MBA 2008). It is a folk religion that is part of the shishi kagura tradition, in which a specialized shishi mask (thought of as a mountain beast [not as a lion as the term seems to imply]), known as gongen-sama, said to be a manifestation of Yamanokami – the great kami (a Shinto god-like spirit) of Mt. Hayachine in central Iwate, is taken in this format house-to-house by performers within its established territory to offer prayers and blessing to local residents during annual visits.16 Visually, Kuromori Kagura costumes, rituals, and performances are quite striking. “The performers look and act like powerful spiritual leaders – one of the reasons this tradition commands so much local respect.” (Kumagai 2013)

|

A display of Kuromori Kagura artifacts including two sets of twin shishi kagura (double “beast heads” – a trademark of this historic folk tradition) at the Yamaguchi Kōminkan (Public Citizens’ Hall) in northwest Miyako near Kuromori Shrine, the headquarters of the Kuromori Kagura Preservation Association. |

There is no literature on Kuromori Kagura in English. Besides two publications on the history and practices of Kuromori Kagura by Kariya Yūichirō (2008; MBA 2008) and a third by Kanda Yoriko on its jungyō(touring) tradition (2008) – all in Japanese – there is no detailed scholarly analysis of Kuromori rituals, symbols or its annual observances in any other language at the present time. However, in 1995, Irit Averbuch (an Israeli scholar) produced a detailed analysis in English of Hayachine Kagura (based at Mt. Hayachine) a related Yamabushi (mountain priest) Kagura tradition, which is quite useful for understanding the generic meanings within the mountain kagura traditions in Iwate of which the Kuromori variety is a significant example. Other writings on Kuromori Kagura in Japanese can be found in Miyako at the Yamaguchi Kōminkan (Public Citizens’ Hall) at the foot of Mt. Kuromori, but are locally published, quite colloquial and unpolished, intended only to preserve the historical record for a local audience. A full account of Kuromori Kagura is not possible here, but a few of its characteristics thought to be important to the residents of the Rikuchū Coast – and which make it such a good potential jisaku shuen tool, introduced to me by Iwate residents knowledgeable about Rikuchū culture and post 3.11 life here – will be discussed (Kumagai 2013; Matsuda 2013; Matsumoto 2013).

First, Kuromori Kagura has historically served not only inland agriculturalists, but the coastal fishing communities on the Rikuchū as well. Service to two distinct demographics is unusual among similar kagura traditions and the respect this garners from the tradition’s constituents gives Kuromori Kagura a sociopolitical and folk religious influence in its territory greater than any other folk tradition in the region. Second, Kuromori Kagura has always been inclusive, encouraging its constituents both inland and on the coast to continue to practice their local folk traditions, incorporating them into its larger all-encompassing folk religious theology. This is unusual in a shugendō-related folk tradition (Kanda 2008). A third distinguishing characteristic is the annual jungyō(touring) tradition in Kuromori Kagura, which has continued uninterrupted for the last 345 years – since at least the 6th year of Genroku (1668). This is unprecedented in the Tōhoku region. Furthermore, this jungyō tradition has been perpetuated in an unusually large territory for a shugendō faith that reaches north of Miyako to present day Kuji, and south of Miyako to a district close to the city of Kamaishi (approximately the same geographical range as what today comprises the Rikuchū Coast). Kuromori Kagura is still relatively unknown outside of its home region. However, it is a worthy representative of the Rikuchū minzoku geinō culture, and has many unique attributes such as those described that make it marketable in a variety of ways. Kuromori Kagura would plug in nicely to a jisaku shuen model (Kumagai 2013; Matsuda 2013; Matsumoto 2013).

Particularly interesting to those from outside the Rikuchū Coast may be a Kuromori Kagura’s jungyō-influenced regional resource distribution system associated with it’s jungyō. Even today, the jungyō operates on a yado (lodge) system in which particularly wealthy households in the Kuromori Kagura territory invite the troupe to perform in their hamlet on a systematic annual basis. The troupe then travels to the village where these yado are located according to a historically prescribed route, staying overnight at each residence along the way. The established route loops north of Miyako inland first, returning to Miyako on the coast, then proceeds south along an inland course to yado there, then loops back to Miyako by way of yado along the shoreline. During the day, at each stop, a variety of rituals are performed with the gongen-sama at the yado and in the surrounding hamlet to protect constituents from illness, to wish for good fortune, and to secure a bountiful harvest. At night, performances of kagura which incorporate local folk performance traditions continue late into the night. According to a document from 1758, troupes typically began their jungyō in November, making about twenty stops on the Kita Mawari (northern loop) tour. This tour was followed by a Minami Mawari (southern loop) jungyō that had about the same number of stops. Two hundred years ago it wasn’t unusual for the jungyō to last until March. At a yado stay, everyone in the local community is invited to observe and participate in performances, eat, drink and be merry. At the same time, information, goods, and gifts (often rice, but financial as well) were shared, hamlet business between the practitioners and local residents was conducted, and local talent was recruited for the Kuromori performance and for its leadership. These practices continue with only slight modifications even today – though the jungyō season is much shorter.

It is this jungyō, which continued over such a long period of time in such a wide territory intertwined so intimately with local practices within the territory that has created the social networks, economic connections, and cultural ties that local residents have relied on in good times and bad that make the linkages within Rikuchū folk performance communities truly unique. During prosperous times, yado and their communities gave material goods, rice, and even money to the Kuromori Kagura contingent for its coffers. When hardship struck, the jungyō brought both spiritual and material relief. Validating the quality and significance of this historic tradition, based at Kuromori Shrine located in Yamaguchi, a western district of Miyako, Kuromori Kagura was designated as a Kuni shitei Mukei Bunkazai (a National Intangible Cultural Asset) in 2006 (MBA 2008) – prestigious in its own right but another characteristic making this troupe a worthy jisaku shuen tool.

A shared local folk history is the reason it meant so much to residents of the Rikuchū Coast when on June 25th, 2011, only three-and-a-half months after 3.11, Kuromori Kagura performed a public kuyō (memorial ceremony for the dead) at Greenpia Sanriku Miyako in Tarō, the site of the tallest tsunami wave, for the lives lost there and the spirits of all victims along the Sanriku Coast (Kariya 2012).17 This performance was regarded as a heroic act by locals because it took place at a time when the coastal area including the Port of Miyako was still a pile of rubble. Though no troupe members died as a result of 3.11, many of them lost loved ones, livelihoods, and homes, yet they performed, taking on a cultural leadership role that will not be forgotten anytime soon (Kariya 2012). Kuromori Kagura then exceeded public expectations when, that December, the troupe resumed its normal jungyō route – first traveling to its northern yado, then in the new year going south to yado there. This speaks not only to the commitment of Kuromori Kagura to its constituents, but to the dedication of the yado owners to this tradition and their willingness to host the troupe and serve its constituents even during this time of great devastation, certainly a venerable quality that any kind of visitor traveling to the Rikuchū Coast to experience Kuromori Kagura could easily respect (Kariya 2011; Yagi 2011).

These are some of the reasons why Iwate culture specialists such as Neko, Matsumoto, and Kariya (see the end of the Ōtsuchi Aki Matsuri section below) and those familiar with the Rikuchū culture and continuing tsunami revitalization efforts here such as Kino, Kuma-gai, Matsuda, Takeda, and Ueda think that there is more that can be done to harness Kuromori Kagura through it’s support organization (called the Kuromori Kagura Hozonkai [Preservation Association]) to enhance the region’s revival and development. Kuromori Kagura’s cultural role as folk religious support mechanism on the Rikuchū Coast is clear. But how exactly Kuromori Kagura and its Preservation Association can develop local opportunities to benefit Rikuchū communities commercially is yet to be seen – but is under study. The annual fall matsuri in Miyako (in which Kuromori Kagura is a major participant) planned for early September of 2014 may include some jisaku shuen-style entrepreneurship (Arihara 2013: Takeda 2013). But regardless of the Preservation Society’s decision about an economic development agenda, the troupe will continue its normal local seasonal performance activities uninterrupted. According to members of the Preservation Association, the troupe’s most important activity – no matter what – is to continue encouraging Rikuchū folk practitioners and their troupes recovering from 3.11 to reorganize, reconfigure, and practice their performance traditions at the local level so coastal residents can continue the recovery process energized by full folk-religion inspired emotional and psychological support (Kariya 2013; Neko 2013). According to many Rikuchū residents I spoke with, this is Kuromori Kagura’s greatest appeal “Its not a resurrected tradition but a real folk practice that has continued uninterrupted since 1669.” (Matsuda 2013)

Something Good out of Something Bad

|

The 2012 OHIO-IPU Tsunami Recovery Support Volunteer group with Kanayama Bunzō-san after several hours of weeding canola. |

Over the course of our three days on the Rikuchū Coast, the OHIO-IPU Tsunami Recovery Volunteer personnel listened to locals’ horrifying tsunami experiences, toured temporary housing villages built on tennis courts, in school yards, and on numerous hillsides just high enough above sea level or sufficiently distant from the ocean to be safe. We made crafts and sang karaoke with seniors, helped elementary school-aged boys and girls with their homework, and played soccer with them for hours. Wherever we went, we could count on eventually being asked two questions – 1) if we would be coming back for another visit, and 2) whether we had plans to see one of their matsuri. Thankfully, to both questions, our group could answer, yes – due mostly to our IPU advisors who had prepared us well. Prior to our 2011 trip, we had learned that the lack of return visits and matsuri participation were two areas in which 3.11 volunteers often disappointed locals. Therefore, even before our first visit, we had planned our project as a multi-year endeavor so we could return regularly to the tsunami zone. Following the missed experience during the 2011 visit, matsuri participation also became a mandatory commitment.

The more residents we met on the Rikuchū Coast, the more we began to understand how much locals valued our commitment to return on subsequent visits. For locals, a return meant we valued the contact with them beyond just the tsunami disaster and were serious about getting to know them better for mutual benefit over the long haul. Our commitment to attend a matsuri showed coastal residents that we cared enough to participate in a local cultural activity that residents felt proud of through which they could show us a bit about themselves. I had never realized how much these coastal residents relied on their local folk practices for psychological and emotional support. In this regard, it was very instructive to observe that in almost every tsunami-related emergency venue our OHIO-IPU Tsunami Recovery Volunteer group visited during this September weekend in 2012, a variety of charms, amulets, talismans, and prayer stickers from Kuromori Shrine (home of Kuromori Kagura) were displayed.18 Not too surprisingly, we felt the strong presence of Kuromori Kagura throughout the remainder of the visit.

On Sunday morning, we helped Kanayama Bunzō and his wife weed their expansive nanohana gardens, planted on several hectares of former rice paddies located next to the river in central Ōtsuchi. These fields had been flooded by seawater from the tsunami, rendering them useless for growing rice. I couldn’t help but notice the Yamaguchi Chiku (district) towel one of their helpers was wearing on her head. She later told me she was a Kuromori Kagura Preservation Association member and that some of the canola seeds planted here had been provided by the troupe. We learned that the nanohana, planted here by Bunzō-san and his wife, not only produce beautiful yellow flowers when they bloom, but help to desalinate the soil and can be converted into biodiesel. “From the flowers, we’ll be fueling local school buses in the future,” commented Bunzō-san, a former truck driver, “and maybe even grow rice again. We’ll be making something good out of something bad.” (Kanayama 2012)

|

The view of Ōtsuchi from Mt. Shiroyama. The Ōtsuchi Town Hall can be seen just above the green fencing built to contain some toxic rubble in the area in the middle of the photo. |

As a final activity on Sunday morning, we were led up the hill behind the riverbed, known as Mt. Shiroyama, Ito Tatsuya, a young man representing the Ōtsuchi Volunteer Center, acted as our guide. He took us to a small park next to Shiroyama Chūō Kominkan (Shiroyama Central Citizens Hall), which overlooks the city, where many Ōtsuchi residents from Sakuragi-chō fled to escape the tsunami on 3.11. Ironically, the lookout was situated on a section of the hill that looked out over a cemetery. It was an eerie contrast to look past the grave markers below to sections of the city in the distance that had been washed way. Huge piles of rubble could still be seen here and there. Ito-san pointed out the remnants of the Ōtsuchi Town Hall where Mayor Ikarigawa Yutaka perished, warning his employees to flee. Forty residents in this neighborhood lost their lives because the seawall blocked their view of the rising ocean, he told us. The seawall, we could see now, was completely washed away. (I learned later that Kuromori Kagura had performed a kuyō here on their southern jungyō during the winter of 2011.) “The lesson here,” Ito-san reminded us, “is to evacuate as soon as you hear there is danger. When you think of Ōtsuchi, please take this lesson to heart and apply it to your lives.” (Ito 2012) With these words, Ito-san – a local resident – demonstrated what was clearly an important key to recovery in the minds of locals here. “We can’t change the past, but we can use this tragedy in Ōtsuchi as a lesson to teach others how NOT to suffer the same fate.” Coming from Ito-san, this was a lesson we were likely NEVER to forget.

The Ōtsuchi Aki Matsuri

It was now about 1pm. Following a dramatic pause as we looked out over the destruction that was Ōtsuchi, Ito-san continued. “This year’s Ōtsuchi Aki Matsuri, he said, “will be celebrated down there. This is the last time we will be celebrating our fall matsuri at the location of our present downtown area,” he added. “A new main street is being cleared on higher ground. And after today, all future fall matsuri will be celebrated there,” (Ito 2012).

We were several hundred meters above the city in elevation, but sure enough, if you looked carefully down to the streets below, groups of local residents, dressed in various kinds of matsuri wear – some in flashy looking happi (happy coats), others in yukata (thin summer cotton kimono), and some in their folk performance attire, while others wore festive summer street clothes – could be seen lining up for a folk parade. It different than the typical shimin matsuri. Instead of dozens of participants dressed in the same performance attire, there were many, many individual troupes from each of the oceanfront neighborhoods close by, lining up in formation, headed to a central performance area, each sporting different festival clothing, colors, and accessories. Unfortunately, it then began to rain. It was a gentle misty rain. But nobody seemed disheartened. Participants just took out the rain gear they had brought along, put it on, covered their equipment with plastic sheets they had also prepared for this purpose, and continued toward the old city center, never considering that they wouldn’t perform.

|

Men from the Matsushita district of Ōtsuchi (as indicated on their happi), waiting with their dashi (festival cart) to enter the fall festival performance space with their dance troupe standing just ahead (out of sight) in September, 2012. |

From close up, the array of minzoku geinō troupes gathered together in full costume were even more impressive than when seen from afar. The fast-paced performance music and dancing was invigorating. The way in which the audience responded to the performers, persevering with their festival despite the great tragedy, despite the rain (which was now more than a mist), was highly inspiring. Ito-san led us down from Mt. Shiroyama to what had once been the central thoroughfare in Ōtsuchi. The street was still there, but now, only the foundations of the buildings remained. Most of the rubble here had been cleared away. In some of the empty lots, little folk altars memorializing the dead could be observed, made from groupings of empty beverage cans configured tastefully as offerings, some bottles and cans held wild flowers picked from the hillside nearby. These seemed to be impromptu memorials, erected probably by matsuri participants who knew those who resided and perished in the buildings that previously stood there. Ito-san confirmed this theory by quickly erecting his own makeshift memorial, before our eyes. “My high school classmate lived here,” Ito-san said. “We think he and his family died, but we aren’t completely sure. Their bodies were never found.” (Ito 2013)

Every neighborhood association (it seemed) was represented by some kind of dashi (festival cart), mikoshi (portable shrine), or folk performance troupe that performed one after the other in a designated “presentation area.” I counted eighteen distinct groups, each led by individuals who looked to be neighborhood leaders guiding their members, dressed in colorful design-coordinated happi and mompe (matching baggy traditional Japanese-style cotton shorts), to the middle of the performance space, and when their turn came, signaled their troupes to begin. As the lion dancers, deer dancers, and demon dancers performed their numbers, local residents crowded around them to watch and cheer in rhythm to the music. Ohhh… oh, oh, oh, went one refrain. The performances included drumming, chanting, flute playing, and in many cases elaborate dance choreography, depending on the genre. It was quite an expression of the Ōtsuchi diehard spirit.

|

An impromptu memorial at the Ōtsuchi Aki Matsuri in September, 2012 similar to the one created by Ito-san for his classmate and family. |

The crowd and the matsuri participants both seemed really glad we were there, but what was most noticeable, was that many of the troupes sported brand-new-looking equipment, and many included very, very young dancers (boys and girls not more than 7 or 8 years-old), coached from the sidelines by senior citizens who stood (some seated in wheelchairs) on the perimeter of the performance space. I only saw one “seasoned” looking mikoshi. The rest were made from recently culled wood and were much smaller in scale than the older looking ones, which looked to be twice or three times the size. Ito-san explained that the newer and smaller-looking mikoshi replaced the originals that had been nagasareta (washed away) (Ito 2013). It seemed that as the rain came down harder, the dancing and chanting became more intense. At the conclusion of each performance, each troupe would march off, replaced by the next group which would assemble, gather themselves, and begin. The troupes that had finished would process along a designated parade route that I later learned led to the location where the new downtown would be built. The mood was festive, but also reverent. Ito-san sensed I was reflecting, so he volunteered. “Sometime before our fall matsuri next year, we’re going to have to get Kuromori Kagura to come and bless our new festival space.” (Ito 2013)

During the hour-and-a-half of performances we watched in Ōtsuchi’s old downtown, I don’t know how many times I was asked (by locals, I presume) whether I was enjoying the afternoon, and what I thought of the local performances. I repeatedly said, “Mochiron tanoshindemasu. Taihen kandō saseraremasu,” (Of course I am enjoying myself. [The folk performances] move me deeply). In most cases, I received a beaming smile in return. But as I reflect back on this experience now, I really WAS moved and felt strongly myself (along with the audience), the powerful emotional charge that reverberated through the crowd that afternoon! I was most surprised, however, when looking out over at the cracked concrete docks lining the shoreline of Ōtsuchi harbor during a performance, I asked Ito-san if he thought he could ever enjoy the sea again after all of the pain it has caused. “I don’t blame the sea at all for what happened,” he replied (Ito 2012).

Why? I asked.

Megumi no umi dammono! (Because the sea is benevolent!) The sea didn’t cause the tsunami, the earthquake did. The sea is the source of our livelihood and our inspiration. The sea didn’t cause our suffering, the earthquake did. The matsuri helps us remember this. The sea is our life! (Ito 2013)

|

Ōtsuchi folk performance troupes proceeding toward their new city center on higher ground in September, 2012. The tsunami on 3.11 washed completely over the top of the home on the right, located approximately 800 meters from Ōtsuchi Harbor to the left. |

I had never thought about it this way before. Now I understood much better the reason for the spirited festivities here today. The tsunami had caused major destruction and loss in local resident’s lives. However, local residents’ didn’t hate the sea. The matsuri was helping all who experienced it to get back on track with their lives by reminding them that the lifestyle and the customs they were so proud of were possible BECAUSE of the sea and were not lost. The local spirit lived on through the matsuri! As I watched the local residents bid farewell to their festival space and prepare to embrace a new location, many with new dancers and new equipment, many groups still missing members of their troupe, I had a new appreciation for the purpose of this event. But this new understanding didn’t make any of the deaths easier to fathom. I later learned that because Ōtsuchi is largely a community of fisheries, many of the most experienced folk performers were at the docks with their fishing boats when the tsunami hit. Many fisherman lost their lives only a few hundred meters away from the performance space.