This article reflects on the predominance of classical music from Europe and the marginalization of Japan’s traditional music, which motivated the author to write her book Not by Love Alone: The Violin in Japan, 1850 – 2010.

The triple disaster which hit Japan in March 2011 sparked off what may well be a record number of charity concerts held worldwide in support of the victims – an eloquent manifestation of Japan’s position as a global musical power.1 The concerts included all kinds of music of Western and Japanese origins, and the musicians came from many countries. A significant proportion of them included Japanese musicians at home and abroad playing Western classical music, thus demonstrating, once again, the well-known fact that Western classical music is also the music of Japan. Western observers have long marvelled at Japan’s success in assimilating Western music, usually without being able to explain it. Nor do Western observers who are unfamiliar with Japan always realize to what extent Japan’s traditional music has been marginalized in the process. Perhaps the most remarkable result of the introduction of Western music into Japan is the fact that to most Japanese today their own indigenous music sounds as exotic as it does to non-Japanese, indicating that within the space of a few decades Japanese musical sensibilities have changed beyond recognition.2

When I first came to Japan in the mid-1980s I soon discovered that it was much easier to hear the music I was familiar with than any music that could be called “traditional,” and that performers of Western music and of Japan’s traditional music largely moved in separate worlds. My first encounter with “Japanese music” in summer 1980 was actually with a piece that defied easy categorization as “Japanese” or “Western”: a youth orchestra from Toyama performing in the Swiss town of Neuchâtel included in its otherwise conventional programme Miyagi Michio’s celebrated piece Haru no umi (Sea in Springtime) arranged for koto and orchestra. Later, in Japan I was twice introduced to koto players who, when they heard that I play the violin, invited me to play Haru no umi with them. From the brief introduction to the published score of the piece3 I learnt that Haru no umi, originally composed for shakuhachi and koto in 1929, was performed in 1932 by the composer himself on the koto with the French violinist Renée Chemet playing her own arrangement of the shakuhachi part. However, when I subsequently searched for other “traditional” music scored for the violin, I discovered that Haru no umi stood in a class of its own. No other well-known piece commonly labelled “traditional” has a tradition, sanctioned by the composer himself, of being performed on the violin. Why, I wondered, were there not more pieces like Haru no umi? In other words, why did the Japanese, with their much-touted propensity for assimilating cultural influences from abroad, not integrate the violin, “the world’s most versatile instrument,” and the “instrument of four continents,” into their indigenous music?4 Years later, having embarked on writing the history of the violin in Japan, I came to the conclusion that I had been asking the wrong question. Instead of wondering about what had not happened to the violin, I began to investigate and reflect upon what did happen. I concluded that the question of the violin and Japanese “traditions” was relevant, but in a way I had not previously considered.

|

Ueno Park, 1999 (photographed by author) |

Meanwhile, intriguing though my experience with Haru no umi was, it was another encounter that eventually led me to turn my favourite hobby into a research topic. In early summer 1999, I was walking with a Japanese friend in Ueno Park in Tokyo, where a festival happened to be in full swing. We wandered into the open air theatre, and on the stage we saw what was to me an astonishing performance. A Japanese man in a kimono, hakama, and high wooden geta sandals was playing the violin and singing at the same time. In between pieces he talked.5 As music goes, the performance did not impress me and the words I did not catch, so when my friend said she thought it was vulgar and wanted to leave, I agreed. The performance, however, stayed with me. What was this man doing in his Japanese attire but with a Western musical instrument? The scene suggested some kind of performance I would label as “folk.” But to my knowledge Western musical instruments had never made it into what we could call the folk traditions of Japan.

Subsequently I came across a passage in Edward Seidensticker, Low City, High City about street musicians known as enkashi.6 Enkashi are usually treated (if at all) in the context of the modern popular song, although most writers agree that there is no direct connection between them and the modern sentimental enka ballad. The enka of the Meiji period were political protest songs, often topical and satirical. From around the time of the Russo-Japanese War it became fashionable for enkashi to accompany themselves on the violin. Musically untrained as they were, their playing style was hardly refined, but it did develop from unison accompaniment of the singing to a more elaborate playing style with prelude, interlude and postlude, as can be heard in recorded examples from the 1920s.7 The heyday of vaiorin enkashi did not last long, although a few are active today. Nevertheless, they represent a significant moment in the history of Western music in Japan: an example of the reception of Western music “from below” as opposed to the systematic introduction “from above.”

Both encounters suggested to me that there were good reasons for making the violin the focus of a cultural history of music in modern Japan and I quickly concluded that my hunch was right. First and most obviously there was the high profile of Japanese violinists on international stages since the 1960s. The most famous is probably Midori (b. 1971), who as a child prodigy was compared to icons like Jascha Heifetz and Yehudi Menuhin and as an adult has become known for her initiatives to bring music to the underprivileged as well as continuing her formidable career as a performer. Although Midori has spent most of her life in the United States, and studied with Dorothy DeLay at Juilliard for several years, her career would never have taken off in the way it did were it not for her early years in Japan and particularly the role played by her mother Gotō Setsu, an “education mum” if ever there was one.8 She now fittingly occupies the Jascha Heifetz chair in music at the Thornton School of Music, University of Southern California. Moreover, the so-called “Suzuki Method,” or Talent Education (Sainō Kyōiku), perhaps the most significant innovation in string pedagogy in the twentieth century, was pioneered by a Japanese violinist, Shin’ichi Suzuki.9 It took North America by storm in the 1960s and today the violin and other instruments are taught with the Suzuki method in many countries of the world. A recent article in The New York Times described the Suzuki Method as “Japan’s Best Overlooked Cultural Export.”10

Second, at the time the Japanese began their systematic importation of Western music, the violin was the most widely disseminated Western musical instrument.11 It represented both the highest and the lowest of Western music and it was widely used to teach singing in schools. Luther Whiting Mason himself, invited in 1881 to teach, train teachers and develop teaching materials at the Music Investigation Committee (Ongaku Torishirabe Gakari), played the violin when he taught singing classes.12

Third, Japanese makers were able to produce serviceable violins as early as the 1880s. The most successful manufacturer was Suzuki Masakichi, the father of Suzuki Shin’ichi, who became famous for his method of string pedagogy. By 1890 he was selling his mass-produced instruments nationwide. Perhaps nothing paved the way for the violin’s popularity as much as Suzuki’s affordable violins, which made it possible for individuals of modest means to buy their own.

Fourth, despite the obvious importance of the violin in the history of Western music in Japan, most research into the history of Western music has prioritized singing. There are good reasons for this. Much of Japan’s indigenous music is vocal or has a vocal component. Singing was taught systematically in elementary schools from the 1880s and popular songs were a field where traditional preferences and new (Western) elements blended in a way that did not happen so easily with instrumental music.

The story of the introduction of Western music in modern Japan has been told before, so a brief summary will suffice here.13 It begins with the creation of the first military bands in the 1850s and 1860s. The Meiji government from the 1870s onward systematically introduced Western music. The main channels were the military, the gagaku musicians of the imperial court and the public education system. In private education, particularly for females, missionaries played a major role, despite the government’s ambivalent attitude towards Christianity. The musical instrument of choice for teaching in schools was the keyboard, most commonly in the form of the reed organ (the piano remained unaffordable until well into the twentieth century), but failing that the violin was used and became one of the most widely disseminated (if not the most widely disseminated) Western instruments in Japan.

Indeed, affordable, small and portable, “the king of musical instruments” as authors of violin tutors and articles in music magazines informed their public in the early twentieth century, the violin became so popular that observers spoke of a violin craze (vaiorin ryūkō): the craze represents an intriguing example of how the foreign music was also appropriated “from below” and not just forced upon the population by government policies.14 Young dandies took up the violin to appear haikara (fashionably Westernized). Geisha threw away their shamisen and took up the violin instead – although apparently mostly in order to pose for picture postcards.

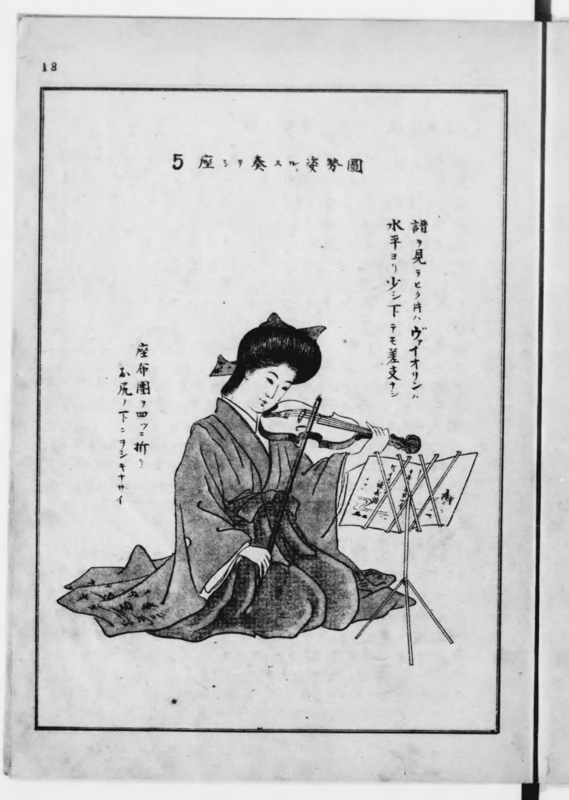

|

Enterprising individuals published scores of Japanese traditional melodies in Western notation or taught them, one by one, for a fee. The violin, played in a kimono and kneeling in the traditional way, became part of ensembles together with the koto (Japanese zither) and shamisen (three-stringed plucked lute).

Graduates from the Tokyo Academy of Music had nothing but contempt for this practice. They perceived it as desecration or an aberration by the merchant classes in Osaka – although contemporary programmes of concerts show that the practice was popular nationwide. Intellectuals, however, writers, professors and their students, took up the violin as an instrument of Western music. Examples include Ishikawa Takuboku, Shimazaki Tōson and Terada Torahiko, immortalized as Mitsushima Kangetsu in Natsume Sōseki’s famous novel I am a Cat. By playing the violin they could physically practise Western civilization as it were and indeed even re-create a piece of it. Whether or not they were conscious of this (notions of karada de oboeru, learning and remembering with the body are an integral part of training in the traditional arts15), remains speculation, but the physicist Terada Torahiko (1878-1935), perhaps Japan’s most famous amateur violinist, seems to show a certain awareness of the issue when he writes in his diary on 6 January 1925: “Before listening to the Ninth Symphony at the Tokyo Academy of Music at the end of the year, I started looking at the score and listening to the record with my conductor’s baton which is much more interesting [than listening passively]. Certainly, part of Western music needs to be savoured not only with the ear but with the body.”16

Terada was writing at the time when professional symphony orchestras began to form in earnest, and one may well ask whether the prospect of creating a part of Western civilization through the physical experience of “keeping together in time,” in this case with synchronized bowing, might not have been part of the attraction.17 The rise of the symphony orchestra and the development of new musical professions in the context of urban consumer culture are among the most significant developments in the history of music and the violin between the world wars. The 1920s and early 1930s saw a major leap forward in the dissemination of Western music, partly as a result of increasing wealth and the expansion of the education system.

Equally important was the fact that Japan was increasingly part of a global community. In the realm of music, this is evinced in the success of Suzuki Violins and Yamaha pianos (Yamaha Torakusu started his business at around the same time as Suzuki, producing and distributing reed organs chiefly for the education market: from 1900 he also manufactured pianos) in exporting to markets formerly in German hands and in the fact that the Japanese became major consumers of imported gramophone recordings of Western classical music. Other indications are the increasing number of foreign artists performing in Japan as well as Japanese musicians taking an active part in international exchanges. To be sure, once Germany had recovered from the First World War, many instrument producers won back their share of the global market and the international successes of Japanese musicians between the two world wars are largely forgotten. Nevertheless, the fact remains, that many developments in this period prefigured those of the late 1950s and the 1960s.

Many of the visiting artists were European refugees, first from the Russian revolution and then from the Nazis, and quite a few of them ended up staying for several years, providing Japanese music enthusiasts with world class live performances and teaching them just when they had reached the stage where they could benefit from it most.

|

Ono Anna (née Anna Dmitrievna Bubnova, 1890-1979), who studied the violin in St Petersburg with the famous Leopold Auer, although not exactly a refugee, would hardly have come to Japan had she not hastily and secretly married the zoologist Ono Shun’ichi (1892-1958) who was stranded in Russia when the First World War broke out. Ono Anna was one of the first to insist on teaching young children. She taught in Japan for 40 years and her influence as a teacher can still be felt today. Courtesy of Ono Anna Memorial Society: www.onoanna.jp/ |

Ever since Japanese violinists began to attract attention abroad in the 1960s observers have remarked that they were about to take the place of Jewish violinists, many of whom came from Eastern Europe, and exercised such a profound influence on violin playing in nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe and the United States. Looking at Japan between the world wars reveals that Japanese violinists often were the heirs of Jewish violinists in a direct way as their pupils. In this way, developments in Japan parallel the history of classical music in North America, which likewise owed much to the influx of European refugees (another parallel is the veneration of Germany and Austria as the heartlands of classical music).18

The interwar period was also a time when some musicians strove to express a “Japanese” identity through the medium of music. Back in the 1880s Isawa Shūji, the man who was instrumental in setting up the Music Investigation Committee and inviting Mason to Japan, envisaged a “national music” which combined the best of Western and traditional Japanese music. Graduates of the Tokyo Academy of Music, including Shikama Totsuji (1853-1928) and Iwamoto Shōji (1885-1954), attempted to promote what came to be known as wayō chōwa or “harmonization of Japanese and Western music”, but this usually amounted to little more than playing Japanese koto and shamisen music, transcribed in staff notation with varying skill, on Western instruments.19 In the 1920s and the 1930s composers’ music, whether in indigenous genres (by then known as hōgaku), like Miyagi Michio, or Western, strove for renewal, and Western-style composers debated the question of “Japanese-style Music.” It is wrong to see such endeavours as nothing more than a symptom of the ultranationalism that dominated politics in the 1930s. In nations everywhere in the world composers sought to create national music. The results are often similar – another illustration of the close relationship between nationalism and globalization.20 One of the composers who joined the debate was the violinist Kishi Kōichi (1909-37), whose compositions for violin and for symphony orchestra were performed in Germany to significant acclaim in the 1930s. Kishi wanted to express “Japaneseness” in his stylistically eclectic compositions, but what made them so accessible to Western ears was their familiarity, including his Western-style musical Orientalism. Kishi eventually became critical of his own efforts.21

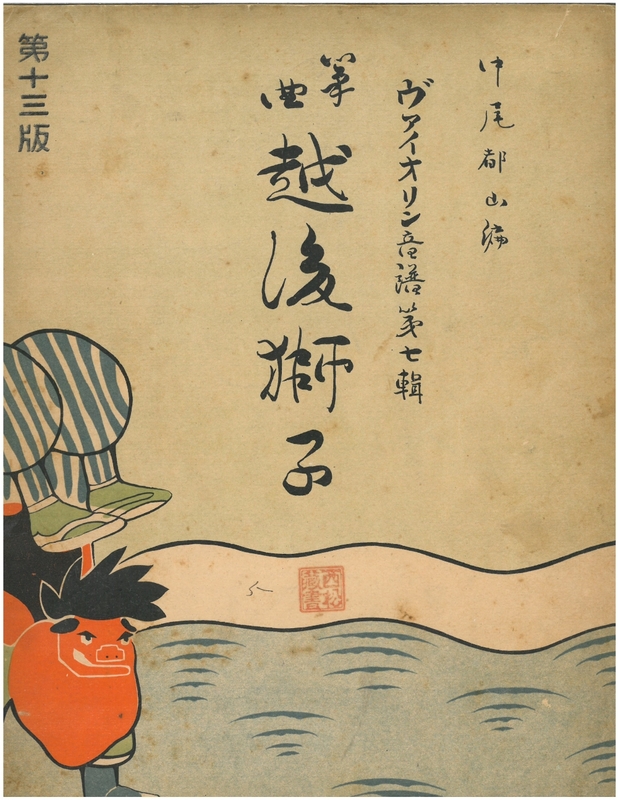

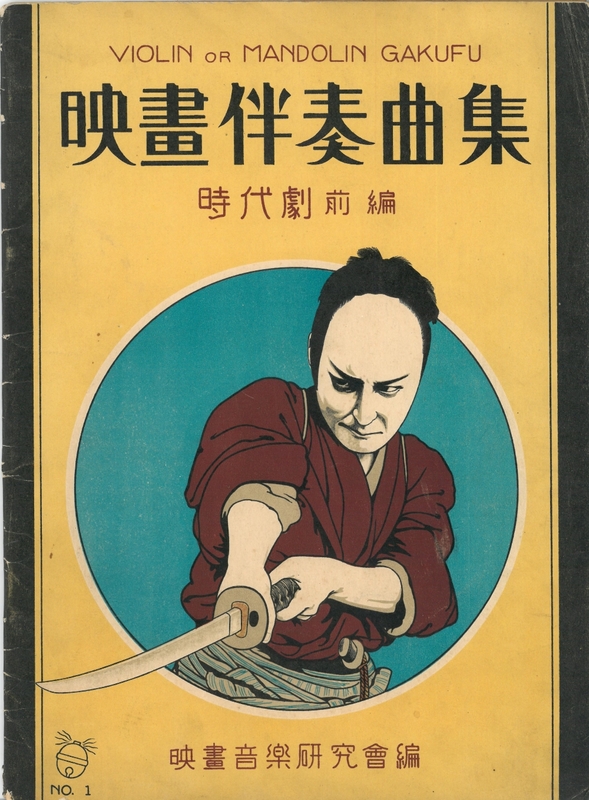

For a more successful “harmonization” of Japanese and Western musical sensibilities, we might do well to look beyond classical music, at genres usually labelled “popular.” There are of course popular songs, but if we are interested in instrumental music, films offer an area worth investigating.

|

Sheet music for the accompaniment of period films (Tokyo, 1927, author’s collection). |

Film became a global medium almost from its inception with local styles developing in various countries. Films became (among other things) a vehicle for expressing and celebrating Japaneseness, most obviously in period films.22 Yet the music did not necessarily exhibit obvious Japanese characteristics and might well sound “Western” to a non-Japanese audience. A good example is Mizoguchi Kenji’s film Genroku Chūshingura (The 47 Rōnin) produced in 1941–42, in the war years when nationalism was at its height, and still popular today. In a moving scene, complete with falling cherry blossoms, Lord Asano, sentenced to death by seppuku, walks to the place of execution; on the way he meets his most loyal retainer, who has taken great pains to see his lord one last time. Yet the music (composed by Fukai Shirō, 1907–59) features the lamenting strings we might expect in a Hollywood movie, where it was especially notable when someone was “dying or making love that the violin came on.”23

To me this and other examples suggest that the violin has in fact found a place in what we might call Japanese traditions. But they are the newly invented traditions of a modern nation finding its place in a global society.

Moreover, the example of Genroku Chūshingura shows the extent to which the Japanese had made the classical music that originated in Europe their own. By the time the film was produced, wartime austerities and, to a lesser extent, anti-Western attitudes were placing restrictions on musical performances. Foreign touring artists stopped visiting, Suzuki Violins had to switch from producing instruments to delivering aeroplane parts, commercial film and record production came to a standstill, musicians had to join the army, and concert venues were destroyed by air raids. However, this did not change the fact that the music we still like to describe as “Western” had become “Japanese” in the sense that it was widely practised and enjoyed at a standard that approached that of European countries. For the celebrations of the 2600th anniversary of the founding of the empire in 1940 the Japanese government even commissioned symphonic works from acclaimed European composers – a clear indication of how much the symphonic music of the West had become part of the state’s modern traditions.24

Seen in this light it is hardly surprising that Japan enjoyed a kind of “musical miracle” after 1945 that paralleled the economic one. In both cases many of the reasons are to be found in the fact that Japan could build on pre-war foundations. The appearance of outstanding Japanese musicians, especially violinists, on the international scene owed much to the high standards of musical education and performance before 1945. The companies Yamaha and Kawai, whose mass-produced pianos took over foreign markets, had a history of producing keyboard instruments that went back to the nineteenth century. Suzuki Shin’ichi, whose pedagogy revolutionized the teaching of stringed instruments, had grown up among Japan’s first mass-produced violins, studied the instrument to the highest level in Germany, and begun to develop his ideas about teaching children even before the war. The post-war economic recovery, together with the widespread yearning for cultural pursuits provided the ideal environment for Suzuki to put his ideas into practice and develop them further.25

By the 1980s, as the economy soared to new heights, Japan’s status as a musical power could hardly be doubted. Classical music still held high prestige as a symbol of Western civilization at its best. At the same time it was a commodity that could be bought with a strong yen. In Tokyo, new concert halls opened which unabashedly combined culture and consumerism: Suntory Hall in 1986, where concert-goers could enjoy alcoholic drinks during the interval (by Suntory of course) in lush surroundings, and Bunkamura in 1989, where they could shop and dine before making their way to the 2,150-seat Orchard Hall on the third floor. An unprecedented stream of foreign artists flocked to Japan. And, the number of Stradivarius violins, a less known but striking indicator of a nation’s wealth, rose from 18 in 1983 to 70 in 1985.26

Nevertheless, many Japanese observers apparently harboured doubts about their country’s successful appropriation of classical music. This became evident in the wake of the “Geidai Master Violin Affair” or “Geidai Affair” in 1981,27 when numerous articles and panel discussions were published in magazines debating the dubious practices surrounding the buying and selling of master violins, the organization and cost of musical education, and the state of classical music in Japan in general. A salient, and to the Western observer somewhat puzzling, aspect of the discussions among musical experts was the view expressed by several of them that, where classical music was concerned, Japan was in some way in a state of transition, backward and immature (mijuku).28 In fact, only some problems may be peculiar to Japan, such as the obsession with and excessive reliance on brand names or the overwhelming dominance of Geidai and of famous teachers located in Tokyo, resulting in starkly unequal access to high-level training for aspiring professionals. Other problems, such as violin fraud and music teachers receiving commissions from instrument dealers without their students (or the students’ parents) knowing, were not. Even a supposedly quintessentially Japanese institution like the maligned iemoto system with its strict hierarchy dominated by a master teacher who expects absolute devotion from his disciples, and its emphasis on preserving the artistic lineage had its Western counterpart; few Western artists are as lineage-conscious as violinists.29

Indeed, as Japan entered the new millennium, many of the developments affecting music in general and violin playing in particular seemed to be the same as elsewhere, including the aging and declining audience for classical music, the diminishing funding for the arts and the over-production of music graduates. The music critic Watanabe Kazuhiko in a book about violinists published in 2002 laments the absence of really outstanding and universally known violinists in Japan. But a similar sentiment concerning a global phenomenon is expressed by the music publicist Norman Lebrecht, writing in The Strad in 2011: “there is no string player today who commands the global reach of past masters.”30

Some continuities do remain, such as the tendency to value Western performers and instrument makers more highly than indigenous talent. Stereotypes about “Asian” performers of classical music not have disappeared entirely in the West,31 but are probably less pervasive there than prejudice and sheer snobbery in Japan.32

Meanwhile, one of the most striking things about violinists from Japan since the end of the Second World War is one they have in common with violinists from other parts of the world: the extent to which they cross borders. Japanese violinists are not limited to Japan: many are equally at home in other countries, often moving between countries. While they may still be labelled “Asian” in the West, they are not that different from their counterparts from other parts of the world. We might even ask how meaningful it is to speak of a violinist as “Japanese.”33

As yet, violinists from Japan who become famous abroad tend to do so through faithful reproduction of the European classical tradition. In this they have been joined, or even overtaken, on the international stage by musicians from Korea, Taiwan and (more recently) mainland China. Classical music from the West continues to enjoy high prestige because of its association with Western civilization. This, however, is not exclusively a European art.

34 But placing it on a lone pedestal in a world where we all have access to an unprecedented amount and variety of musics makes less and less sense; any more than it makes sense to keep traditional Japanese music on a pedestal as a precious tradition which must be preserved in its pure form (a development which in any case is a product of the post-war period35).

For Japanese violinists, as for violinists elsewhere, the artificial divide between origins, genres and styles becomes increasingly insignificant in their quest for individual expression and for a wider audience. A growing number are exploring different kinds of music. Distinguishing between classical and popular or even the distinction between Japanese and foreign is losing its meaning. Violinists from Japan may seek a Japanese identity, and some may do so by introducing perceived traditional Japanese characteristics into their music. Even so, however, their Japanese identity will be inseparable from an identity as participants in a global culture and their musical language will be accessible to a global audience. The Japanese have made the violin their own, but not in the sense of adapting it to pre-modern traditions. Instead, almost from its introduction, it has also been and continues to be a vehicle for the Japanese as they engage in the global community.

In other words, while the violin was not assimilated into the traditional music of Japan, it has undoubtedly played a leading role in the formation of Japan’s modern traditions. This is first, because the art music that originated in Europe has itself become the music of Japan, a music to which Japanese performers, conductors and composers have contributed. Second, it is because the violin features prominently in modern and popular musical expressions of Japanese identity that are simultaneously local expressions of a global musical culture.

Margaret Mehl is an Associate Professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Copenhagen. and the author of History and the State in Nineteenth-Century Japan (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998) and Private Academies of Chinese Learning in Meiji Japan: the Decline and Transformation of the kangaku juku (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2003, Pbk ed. 2005).

Margaret Mehl’s book, Not by Love Alone: The Violin in Japan, 1850-2010 (Copenhagen: The Sound Book Press, 2014) is now available from Amazon and should soon be available from other major retailers.

ISBN 978-87-997283-0-5 (hardback)

ISBN 978-87-997283-1-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-87-997283-2-9 (epub)

ISBN 978-87-997283-3-6 (mobi)

For details about the book see http://notbylovealone.com

Recommended citation: Margaret Mehl, “Going Native, Going Global: The Violin in Modern Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 48, No. 3, December 1, 2014.

Notes

1 For a few examples see Mehl, Margaret, “Music after the Tōhoku Disaster (1-5)”. For Japan, see Oshio, Satomi, “Higashi Nihon daishinsai no ongaku katsudō ni kansuru chōsa: ‘Kahoku shinpō’ no kiji (2011.3.12 – 2011.12.9) kara miru 9 ka getsu kan no dōkō,” in Heisei 23 nendo Miyagi Kyōiku Daigakuin Ongaku Kyōiku Senshū “Ongakugaku tokuron” hōkokusho (Sendai: Miyagi Kyōiku Daigaku Oshio Kenkyūshitsu, 2013), ———, “Higashi Nihon daishinsai no ongaku katsudō ni kansuru chōsa (sono 2): Shinsai kara 1 nen 5 ka getsu kan no katsudō o kangaete,” in Heisei 24 nendo Miyagi Kyōiku Daigakuin Ongaku Kyōiku Senshū “Ongakugaku enshū” hōkokusho (Sendai: Miyagi Kyōiku Daigaku Oshio Kenkyūshitsu, 2013), ———, “Higashi Nihon daishinsai no ongaku katsudō ni kansuru chōsa (sono 3): Intabyū chōsa o chūshin ni,” in Heisei 24 nendo Miyagi Kyōiku Daigakuin Ongaku Kyōiku Senshū “Ongakugaku tokuron” hōkokusho (Sendai: Miyagi Kyōiku Daigaku Oshio Kenkyūshitsu, 2013). Also Kudō, Ichirō, Tsunagare kokoro, tsunagare chikara: 3.11. Higashi Nihon daishinsai ni tachimukatta ongakukatachi, (Tokyo: Geijutsu Gendaisha, 2013).

2 Since the subject of my book and this article is Japan, I will not discuss comparable developments in other Asian countries, although today winners of international competitions (to give one example) are just as likely to be from South Korea, Taiwan and mainland China as from Japan. In Korea, colonized by the Japanese, many school children may well have seen and heard the violin in the hands of a Japanese school teacher, as did the Korean-born Japanese luthier Chin Shōgen (1929-2012). See Chin, Shôgen, Kaikyô o wataru baiorin, (Tokyo: Kawade Shobô, 2007). I should also

mention that my study does not deal with Okinawa, where, compared to Japan, indigenous music was not displaced to the same extent.

3 Miyagi, Michio, Sōkyoku gakufu Miyagi Michio sakkyoku shū: Haru no umi, (Fukuoka: Dai Nihon Katei Ongaku Kai, 1931). On the reception of the performance in 1932, see Watanabe, Hiroshi, Nihon bunka modan rapusodi, (Tokyo: Shunjūsha, 2002): 39-43, Chiba, Yūko, Doremi o eranda Nihonjin, (Ongaku no Tomosha, 2007): 6.

4 Schoenbaum, David, The Violin: A Social History of the World’s Most Versatile Instrument, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2012), Cooke, Peter, “The violin – instrument of four continents,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Violin, ed. Stowell, Robin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

5 I have not yet been able to confirm the identity of the performer. It may be Fukuoka Utaji福岡詩二. If so, he is still going strong. The following links to Youtube videos show (1) A short explanation and demonstration of what he calls “Taishō enka”, including remarks about his garb and 2) A comic performance where he pokes fun at iconic names in the world of classical music: Stradivari violins and Carnegie Hall (both accessed 22 August 2014).

6 Seidensticker, Edward, Low City, High City: Tokyo from Edo to the Earthquake: How the Shogun’s Ancient Capital Became a Great Modern City, 1867-1923, (Tokyo: Tuttle, 1983): 163-64. See also Mitsui, Toru, “Interaction of Imported and Indigenous Music in Japan: A Historical Overview of the Music Industry,” in Whose Master’s Voice: The Development of Popular Music in Thirteen Cultures, ed. Ewbank, Alison J. and Papageorgiu, Fouli T. (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1997).

7 Lewis, Michael, ed. A Life Adrift: Soeda Azembō, Popular Song, and Modern Mass Culture in Japan (London: Routledge,2009), xxi, 136-37. Gondō, Atsuko, “Meiji, Taishō no enka ni okeru Yōgaku juyō,” Tōyō ongaku kenkyū. 53 (1988): 15-17. A search for ヴァイオリン演歌on Youtube will produce several examples.

8 Mehl, Margaret, Not by Love Alone: The Violin in Japan, 1850-2010, (Copenhagen: The Sound Book Press, 2014): 305-16. Similarly, the original members of the Tokyo Quartet were formed at least as much by their early training in Japan under Saitō Hideo as by their years at Juilliard: Not by Love Alone: The Violin in Japan, 1850-2010, (Copenhagen: The Sound Book Press, 2014): 373-74.

9 See Mehl, Margaret, “Cultural Translation in Two Directions: The Suzuki Method in Japan and Germany,” Research and Issues in Music Education 7. 1 (2009).

10 Hotta, Eri, “Tokyo’s Soft Power Problem. The Suzuki Method: Japan’s Best Overlooked Cultural Export,” The New York Times (Online version), 24 October 2014. For details about the organization of the Suzuki Method worldwide, see the International Suzuki Association’s website with links to regional associations.

11 Cooke, “The violin – instrument of four continents.”

12 For descriptions of Mason’s work and the beginnings of music teaching in schools, see Howe, Sondra Wieland, Luther Whiting Mason: International Music Educator, (Warren, Michigan: Harmonie Park Press, 1997), Eppstein, Ury, The Beginnings of Western Music in Meiji Era Japan, (New York: Edwin Mellen, 1994).

13 Even so, the number of accessible studies in English is hardly excessive. Useful, if brief, older overviews are Nomura, Kōichi, “Occidental Music,” in Japanese Music and Drama in the Meiji Era, ed. Komiya, Toyotaka (Tokyo: Ōbunsha, 1956), Malm, William P., “The Modern Music of Meiji Japan,” in Tradition and Modernization in Japanese Culture, ed. Shively, Donald (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971). The most comprehensive treatment of the significant contributions by German and Austrian musicians in Japan is still Suchy, Irene, “Deutschsprachige Musiker in Japan vor 1945. Eine Fallstudie eines Kulturtransfers am Beispiel der Rezeption abendländischer Musik” (doctoral thesis, University of Vienna, 1992). For the education system, see Eppstein, Beginnings of Western Music. Recent overviews include Wade, Bonnie C., Music in Japan, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), Herd, Judith Ann, “Western-influenced ‘classical’ music in Japan ” in The Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music, ed. Hughes, David W. and Tokita, Alison McQueen (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2008). Mehl, Margaret, “Introduction: Western Music in Japan: A Success Story?,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 10. 2 (2013).

14 ———, “Japan’s Early Twentieth-Century Violin Boom,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 7. 1 (2010). Kajino, Ena. “A Lost Opportunity for Tradition: The Violin in Early Twentieth-Century Japanese Traditional Music.” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 10, no. 2 (2013): 293-321. In fact by the nineteenth-century the violin had undergone a sex-change in European perception.

15 Yuasa, Yasuo, The Body: Toward an Eastern Mind-Body Theory, trans. Kasulis, Thomas P. and Nagatomo, Shigenori (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), Hahn, Tomie, Sensational Knowledge: Embodying Culture through Japanese Dance, (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2007).

16 Quoted in Suenobu, Yoshiharu, Terada Torahiko: Baiorin o hiku butsurigakusha, (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2009): 217.

17 McNeill, William, Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History, (Cambridge, Massachusets: Harvard University Press, 1997). The significance and meanings of the symphony-orchestra concert and its relationship with the Western–style scientific-industrial culture and the rising middle classes worldwide are discussed in Small, Christopher, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening, (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1998). About the military connotations of violin playing: Kawabata, Maiko, “Virtuoso Codes of Violin Performance: Power, Military Heroism and Gender (1789-1830),” 19th-Century Music 28 (2004).

18 An example of an early report: Henahan, Donal, “Young Violinists From Asia Gain Major Place on American Musical Scene,” The New York Times, 2 August 1968. More recently, David Schoenbaum has commented on the phenomenon: Schoenbaum, The Violin: A Social History of the World’s Most Versatile Instrument: 450 and “Sunrise, Sunset,” (2014).

For North America: Horowitz, Joseph, Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall, (New York: Norton, 2005): 328 ff. For America and Germany see also Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E., Sound Diplomacy: Music and Emotions in Transatlantic Relations, 1850-1920, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

19 Shikama Totsuji 四竈訥治(訥堂、1853-1928), one of the early pioneers of Western music, was the editor of Ongaku zasshi, the first journal dedicated to music. Iwamoto Shōji (巌本捷治,1885-1954) was the brother of Iwamoto Yoshiharu (1863-1942), educator and founder of the women’s magazine Jogaku zasshi. About playing Japanese music on the violin see Kajino, Ena, “A Lost Opportunity for Tradition: The Violin in Early Twentieth-Century Japanese Traditional Music,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 10. 2 (2013).

20 Indeed, it has been argued that one of the main characteristics of modern globalization is the increasing uniformity: Bayly, Christopher Alan, The Birth of the Modern World 1780-1914: Global Connections and Comparisons, (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004).

21 On Kishi, see Kajino, Ena, Seiji Chōki, and Heruman Gochefusuki, eds., Kishi Kōichi to ongaku no kindai: Berurin firu o shiki shita Nihonjin (Tokyo: Seikyūsha,2011). Kishi’s life and career is treated in detail in Not by Love Alone.

22 Japanese period films search for the essence of Japaneseness: Mellon, Joan, The Waves at Genji’s Door: Japan Through Its Cinema, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976).

23 Studio concertmaster Israel Baker, quoted in Heiles, Anne Mischakoff, “The Golden Fiddlers of the Silver Screen,” The Strad. November (2009).

24 Furukawa, Takahisa, Kōki, Banpaku, Orinpikku: Kōshitsu burando to keizai hatten, (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1998).

25 Mehl, Margaret. “Cultural Translation in Two Directions: The Suzuki Method in Japan and Germany.” Research and Issues in Music Education 7, no. 1 (2009).

26 Yokoyama, Shin’ichi, Sutoradivariusu, (Tokyo: Ascii Media Works, 2008): 156.

27 Details in Not by Love Alone, Part 2 Chapter 12. In late 1981 the violinist and Geidai Professor Unno Yoshio and the violin dealer Kanda Yūk were arrested and charged with corruption in connection with the sale of master violins to Tokyo University of Fine Arts (Geidai). Both were subsequently sentenced, and Unno, in many ways a scapegoat in the whole affair, lost his post at Geidai.

28 Ongaku no Tomosha, “Tokubetsu zadankai: Vaiorin mondai ni hata o hasshita Nihon kurashikku ongakukai no genjō o tou,” Ongaku no tomo. February (1982): 125.

29 See, for example, the ”family tree” in Campbell, Margaret, The Great Violinists, (London: Granada, 1980): xx-xi. or at violinist.com: V.com weekend vote: Who is in your violin family tree? August 16, 2008 at 12:12 AM

30 Watanabe, Kazuhiko, Vaiorinisuto 33: Mei-ensōka o kiku, (Tokyo: Kawade Shobô, 2002): 276-77, Lebrecht, Norman, “Comment (lack of globally famous string players),” The Strad. October (2011).

31 See Yoshihara, Mari, Musicians from a Different Shore: Asians and Asian Americans in Classical Music, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007).

32 As was the case with the Suzuki Method, gaining fame in the West can pave the way to fame in Japan. Midori would be another case in point. In the early days of her career, however, the Japanese did not quite know what to make of her: she seemed too “American” to be truly Japanese. More recently this preoccupation seems to have faded into the background: Not by Love Alone, 316.

33 Not by Love Alone, Part 3.

34 Parakilas, James, “Classical Music as Popular Music,” The Journal of Musicology 3. 1 (1984): 1, 18-19, Ross, Alex, The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, (New York: Picador, 2007): 562-67.

35 Watanabe, Nihon bunka modan rapusodi.