Introduction by John W. Dower

The following article is a reprint of a unit developed by MIT Visualizing Cultures, a project focused on image-driven scholarship. Click here to view the essay in its original, visually-rich layout. And see the complete image galleries here. In the coming months the Asia-Pacific Journal will reprint a number of articles on the theme of social protest in Japan originally posted at MIT VC, together with an introduction by John W. Dower to the series. These are the first in a continuing series of collaborations between APJ and VC designed to highlight the visual possibilities of the historical and contemporary Asia-Pacific, particularly for classroom applications.

Between 2002 and 2013, the Visualizing Cultures (VC) project at M.I.T. produced a number of “image-driven” online units addressing Japan and China in the modern world. Co-directed by John Dower and Shigeru Miyagawa, VC tapped a wide range of hitherto largely inaccessible visual resources of an historical nature. Each topical treatment—which can run from one to as many as four separate units—formats and analyzes these graphics in ways that, ideally, open new windows of understanding for scholars, teachers, and students. VC endorses the “creative commons” ideal, meaning that everything on the site, including all images, can be downloaded and reproduced for educational (but not commercial) uses.

Funding and staffing for VC formally ended in 2013, with around eight topical treatments still in the pipes. These will eventually go online. Overall, including the treatments to come, the project includes a total of fifty-five individual units covering twenty-six different subjects. The China-Japan division will be roughly equitable when everything is in place. (There will also be a two-part treatment of the U.S. and the Philippines between 1898 and 1912.) The full VC menu can be accessed at visualizingcultures.mit.edu.

VC is closing shop for the production of new units at a moment when it was just reaching a “critical mass” of subjects that invite crisscrossing among separate topical treatments. Western imperialist expansion beginning with the Canton trade system, first Opium War, and Commodore Matthew Perry’s “opening” of Japan is potentially one such subject; comparing and contrasting Japanese and Chinese engagements with “the West” is another. The VC units draw vivid attention to political, cultural, and technological transformation in East Asia between the mid-19th and mid-20th century. Many of them highlight graphic expressions of militarism, nationalism, racism, and anti-foreignism. Because the visual resources tapped for these units range from high art to popular culture, and are especially strong in the latter, it is now possible to tap the site to explore the emergence of consumer cultures and mass audiences in Japan and China. This, in turn, calls attention to popular cultures and grassroots activities in general.

One example of the insights to be gained by approaching the VC menu with this comparative perspective in mind is the subject of popular protest in Japan. That is the common thrust of the four separate VC units introduced here. This is, of course, a pertinent subject today, when the mass media in the Anglophone world tends to portray Japan as a fundamentally homogeneous, consensual, harmonious, conflict-averse and risk-averse “culture” (a familiar rendering, for example, in the venerable New York Times).

No serious historian of modern Japan would endorse these canards, which carry echoes of the “beautiful customs” nostrums of Japan’s own nationalistic ideologues. At the same time, however, it cannot be denied that the past four decades or so have seen nothing comparable in intensity or scale to the popular protests in prewar Japan, or the demonstrations and “citizens’ movements” (shimin undō) that took place in postwar Japan up to the early 1970s. How can we place all this in perspective?

The image-driven VC explorations of protest in Japan begin in 1905 and end with the massive “Ampō” demonstrations against revision of the U.S.-Japan mutual security treaty in 1960. The four treatments that will be reproduced in The Asia-Pacific Journal beginning in this issue are as follows:

1. Social Protest in Imperial Japan: The Hibiya Riot of 1905, by Andrew Gordon. We reprint this article with this introduction. Other articles will follow in the coming months.

2. Political Protest in Interwar Japan: Posters & Handbills from the Ohara Collection (1920s~1930s), by Christopher Gerteis (in two units).

3. Protest Art in 1950s Japan: The Forgotten Reportage Painters, by Linda Hoaglund.

4. Tokyo 1960: Days of Rage & Grief: Hamaya Hiroshi’s Photos of the Anti-Security-Treaty Protests, by Justin Jesty.

VC and the Asia-Pacific Journal are committed to bringing the highest quality visual images to the classroom. In establishing this partnership, we anticipate publishing the subsequent units on protest every two weeks. We hope to follow this up with new units in preparation and projected.

Producer/Director Linda Hoaglund was born and raised in Japan. Her previous film, Wings of Defeat, told the story of Kamikaze pilots who survived WWII. She directed and produced ANPO, a film about Japanese resistance to U.S. bases seen through the eyes and works of celebrated Japanese artists whose work is included here. See the trailer here. Her latest film, The Wound and the Gift, narrated by Vanessa Redgrave, premiers at the New York Film Festival on November 15. She worked as a bilingual news producer for Japanese TV. She has subtitled Japanese films, represents Japanese directors and artists, and serves as an international liaison for film producers. An Asia-Pacific Journal Associate, she can be contacted here.

John W. Dower is emeritus professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His books include Empire and Aftermath: Yoshida Shigeru and the Japanese Experience, 1878-1954 (1979); War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986); Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999); Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor / Hiroshima / 9-11 / Iraq (2010); and two collections of essays: Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays (1994), and Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering: Japan in the Modern World (2012).

|

The 1950s have become something of a lost decade in historical recollections of postwar Japan. It is not difficult to understand why. The “‘50s” were overshadowed by the dramatic U.S. occupation that followed the country’s defeat in World War II, lasting until 1952. And they were eclipsed by what followed: the “income doubling” policies initiated in 1960 that, for the first time, drew international attention to Japan’s economic reconstruction.

In fact, this was a tortured and tumultuous decade. Bitter memories of the recent war that ended in Hiroshima and Nagasaki folded into the spectacle of a cold-war nuclear arms race and a hot war next door in Korea (extending from 1950 to 1953). The continued post-occupation presence of a massive network of U.S. military bases provoked enormous controversy, as did the conservative government’s commitment to rearm Japan under the U.S. military aegis. Former leaders of Japan’s recent aggression returned to the political helm—symbolized most dramatically by the 1957 elevation to the premiership of Kishi Nobusuke, an accused (but never indicted) war criminal.

If the Japan of the 1950s in general has fallen into a black hole of memory, all the more so is this true of the vigorous grassroots protests that opposed Japan’s incorporation into U.S. cold-war policy. As one artist introduced here observed, to many Japanese the 1950s seemed like an era of “civil war”—if not literally in a military sense, then certainly politically and ideologically. This was a far cry from the consensual and harmonious place mythologized by later exponents of a monolithic “Japan Inc.”

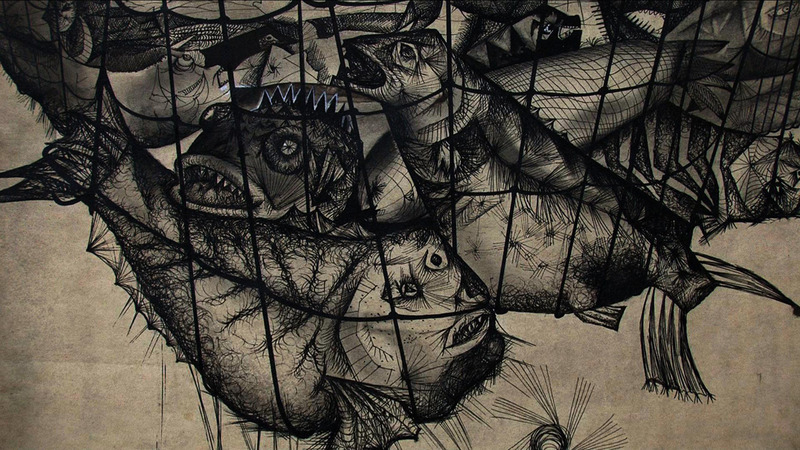

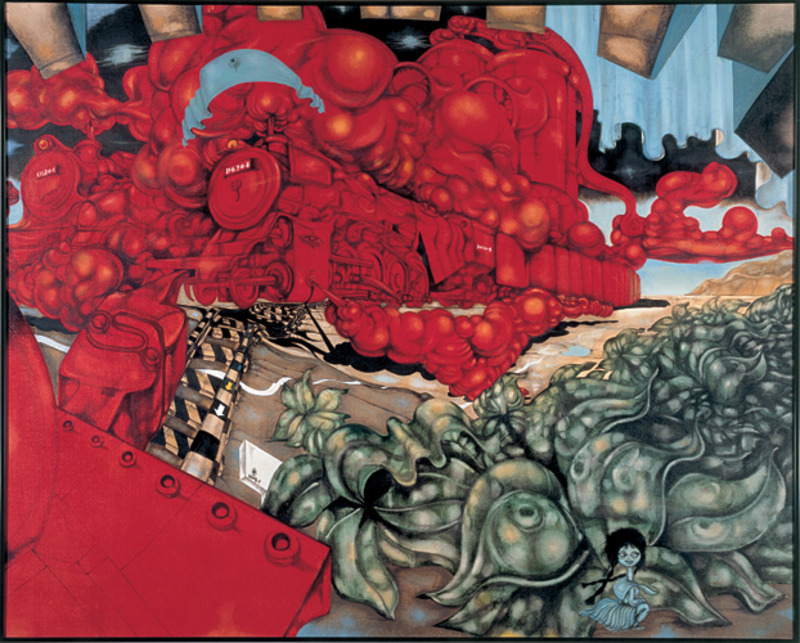

“Reportage painters” was a loose label attached to left-wing artists of the time who rejected conventional aesthetics, while bearing witness to unfolding military and political events. The artwork they produced in the 1950s and early 1960s is now largely buried in museums, and even in their own time they had few opportunities to exhibit their work, and found few patrons willing to buy it. Yet their vigor, vision, integrity, and originality are extraordinary. In their distinctive ways, the four reportage artists introduced here open a stunning window onto these turbulent, neglected years.

This Visualizing Cultures unit complements Linda Hoaglund’s prize-winning 2010 documentary film “ANPO: Art X War.” The acronym ANPO, familiar to all Japanese of a certain age, derives from the Japanese name of the bilateral U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, under which Japan committed itself to rearm and host U.S. military bases. In Japanese parlance, reference to the “ANPO struggle” usually focuses on the protests against renewal of the security treaty that convulsed the nation in 1960, culminating in riots in Tokyo. The “forgotten reportage painters”—this unit’s subtitle—convey the deeper history of this passionate anti-base, anti-rearmament, anti-corruption protest movement.

“ANPO: Art X War” was screened in numerous international forums in 2010 and 2011. The documentary was honored in Japan with a nomination by the Agency for Cultural Affairs for the 2011 Best Cultural Documentary Prize, and in the United States by the 2012 Erik Barnouw Award of the Organization of American Historians (for “significant visual contribution to the history of American international relations”).

JAPAN IN THE 1950s

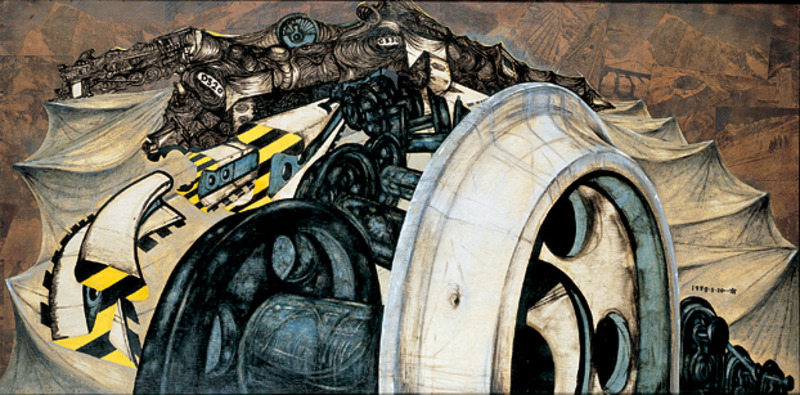

In 1958, Nakamura Hiroshi, one of the artists featured in this essay, produced a surreal painting titled “The Civil War Era,” referring to the situation in Japan. His original title had been “Postwar Revolution,” but Nakamura decided this exaggerated the situation. “Civil war,” on the other hand, suggested a kind of purgatory between war and peace, in which the struggle involved nothing less than whether Japan could become a truly peaceful and democratic nation if it remained locked in the military embrace of the United States.

Like many of his compatriots, Nakamura was severely critical of the conservative governments that had dominated Japanese politics since 1948 and negotiated the terms under which Japan regained sovereignty in 1952, after six years and eight months of being occupied by the U.S.-led victors in World War II. As the political left saw it, the price paid for nominal sovereignty was bogus independence. Under the bilateral U.S.-Japan security treaty that was Washington’s quid pro quo for ending the Occupation, Japan agreed (1) to rearm under the American aegis; (2) to allow U.S. military bases throughout the country; (3) to surrender de-facto sovereignty over Okinawa, which had become America’s major “forward” projection of military power in Asia; (4) to rely on the U.S. “nuclear umbrella” for security; and (5) to acquiesce in the economic and political “containment” of China, where the Communists had emerged victorious in 1949.

Most of the conservatives who endorsed these conditions agreed that the security treaty and its supplementary bilateral agreements (extending into 1954) were inequitable. It was widely acknowledged that the United States obtained more extensive military rights and privileges in sovereign Japan than it had demanded from any of its other cold-war partners. Given the global situation, however, the conservatives saw no alternative to paying a high price to escape the humiliation of protracted occupation. The Soviet Union had tested its first nuclear weapon in 1949, the same year that the People’s Republic of China was established. The Korean War had erupted in June 1950—drawing in both the U.S. and subsequently China, and dragging on into 1953. A mere five years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of World War II in Asia, American strategic planners had come to regard Japan not merely as an indispensable military base, but also as the projected “workshop” of the non-Communist Asian world.

Even the staunch anti-Communist and pro-American political leader Yoshida Shigeru, who served uninterruptedly as prime minister from late 1948 to the end of 1954, regarded Washington’s cold-war demands as excessive. He was willing to trade Okinawa for American guarantees of protection, but did not welcome extensive U.S. bases in the main islands of Japan, did not support the isolation of China, and regarded Washington’s demands for rapid rearmament as particularly foolhardy while harsh memories of Japan’s recent militarism were still vivid, domestically and among the nation’s neighbors. In a reflection on the state of the country written shortly after he left the premiership, Yoshida employed language analogous to Nakamura’s evocation of “civil war.” An ideological “38th parallel” had split Japanese society in two, he observed, taking his bleak metaphor from the post-World War II division of Korea.

It was the hope and expectation of Yoshida and his fellow conservatives that the most grating and blatantly inequitable aspects of the U.S.-Japan security relationship would be corrected within a short time. The target date was 1960, when the bilateral treaty would come up for revision—and the path to that date turned out to be more tortuous and contentious than anyone anticipated, as a succession of particularly provocative military-related incidents inflamed domestic hostility to the militarized U.S.-Japan relationship. This is the milieu in which the artists introduced here produced their protest paintings.

The genesis of the so-called peace movement in postwar Japan actually dates to late 1949, when U.S. plans to turn Japan into a bulwark against Communism first became clear. Protest intensified when the terms of the secretly-negotiated security treaty were disclosed in 1951 and 1952, and grew even more intense in the several years that followed, as the concrete presence of an unexpectedly extensive web of post-occupation U.S. bases and facilities materialized.

When the Americans finally relinquished direct control of Japan in the final days of April 1952, they left a mixed legacy of genuine friendship and goodwill on the one hand, and disillusion and hostility on the other. The latter erupted openly within days—on May 1, known ever since as “Bloody May Day”—when union-led demonstrators clashed with police in Tokyo in a day-long confrontation that left several protestors dead. One of the major issues that fired up the protestors was the militarized nature of the peace settlement.

“Bloody May Day” marked the beginning of a near-decade of continuous, volatile anti-base and anti-remilitarization protests that culminated in massive demonstrations that convulsed Tokyo in May and June 1960, when the security treaty came up for renewal. Communists and non-communist leftists played major roles in many of these protests. What truly alarmed the Japanese government and its handlers in Washington, however, was the extent to which this movement fed on grassroots support—often stimulated by sensational events.

One of the most galvanizing of these events occurred in March 1954, when a Japanese tuna-fishing boat named Lucky Dragon #5 was irradiated by fallout from an American thermonuclear (hydrogen-bomb) test at Bikini Atoll, located between Hawaii and Japan. The ship’s catch was contaminated, and it was widely feared that such contamination extended to other catches in the vast ocean area where U.S. nuclear testing took place. More shocking, all 23 of the Lucky Dragon’s crewmen developed symptoms of radiation poisoning, and the ship’s radio operator died of acute radiation sickness six months later. (“I pray,” he said famously near the end, “that I am the last victim of an atomic or hydrogen bomb.”) While the U.S. government tried mightily to cover-up the enormity of this tragedy, the response in Japan was a groundswell of anti-nuclear activism that included a petition calling for abolition of nuclear weapons that was reported to have been signed by an astonishing 30-million individuals, amounting to over half of Japan’s adult population.

The mid 1950s saw a nationwide surge in anti-base activity. One of the most dramatic and highly publicized of these protests, known as the Sunagawa struggle, arose in opposition to government plans to confiscate privately owned farmland in order to expand the runways at the already huge Tachikawa air field, on the outskirts of Tokyo. Beginning in 1955, student and labor-union activists joined local residents at Sunagawa, a town on the edge of the base, in a series of confrontations with police who had been dispatched to protect the government’s land surveyors. In 1955 and 1956, the well-known leftist film maker Kamei Fumio produced three documentary treatments of the Sunagawa struggle; and on July 8, 1957, this confrontation culminated in a riot that led to seven individuals being arrested and accused of trespassing on the U.S. base, which was a felony under the terms of the bilateral security arrangements.

In a sensational decision on the “Sunagawa case” (this is sometimes romanized as “Sunakawa”) delivered on March 30, 1959, the Tokyo District Court found the trespassers not guilty on grounds that maintaining “war potential” on Japanese soil was prohibited by article nine of the nation’s postwar constitution—which meant that the maintenance of U.S. bases under the bilateral security treaty was itself unconstitutional. Prodded by a frantic Washington, the Japanese government intervened to rush the case directly to the supreme court, which overturned the district-court decision with unprecedented speed and—in a decision of great consequence delivered in December 1959, on the very eve of the government’s 1960 timetable for renewing the security treaty—declared that article nine did not prohibit Japan from engaging in self-defense, including security agreements with other countries. (Years later it was learned that the U.S. ambassador to Tokyo had met directly with the chief justice of Japan’s supreme court before the lower-court decision was overturned.)

Six months before the Sunagawa confrontation peaked in the arrests of July 1957 and ensuing court case, a shocking base-related incident of a different sort galvanized anti-base sentiment nationwide. On January 30, an American soldier guarding a U.S. Army shooting range in Gunma prefecture shot and killed a 46-year-old mother of six who had trespassed on the firing range to collect spent shell casings, which she sold as scrap metal. This wanton act became known as the “Girard incident,” after the name of the shooter, and led to controversial legal proceedings as well as acute and often acrimonious tensions with the U.S., where public opinion was mobilized against the Japanese having any legal role in the disposition of the case.

When Nakamura Hiroshi described the 1950s as a “civil-war era,” he obviously had these confrontations over the militarization of Japan in mind. He himself took both the Girard and Sunagawa incidents as subjects of his artwork, in two equally powerful but stylistically very different protest paintings. Militarization, however, was only one aspect of what Nakamura and his like-minded compatriots found disturbing and grotesque in post-occupation Japan.

Commonly known as the “reportage painters” for their distinctive left-wing combination of realism and surrealism, these artists also called attention to social oppression and grievous poverty; to corruption, and the return of former militarists to high political positions; and to the “inhumane mechanism” of postwar society in general.

NAKAMURA HIROSHI

Nakamura Hiroshi (1932– ) was trained as a reportage painter by the Japan Art Alliance, a postwar art group that advocated politically-themed realist painting. As he recalled:

In the early 1950s, socialist realism was spreading throughout the world as an art movement and many art students were influenced by it. The Alliance’s basic premise was that our paintings had to be readily understood by anyone who saw them. We were encouraged to persuade the viewer.

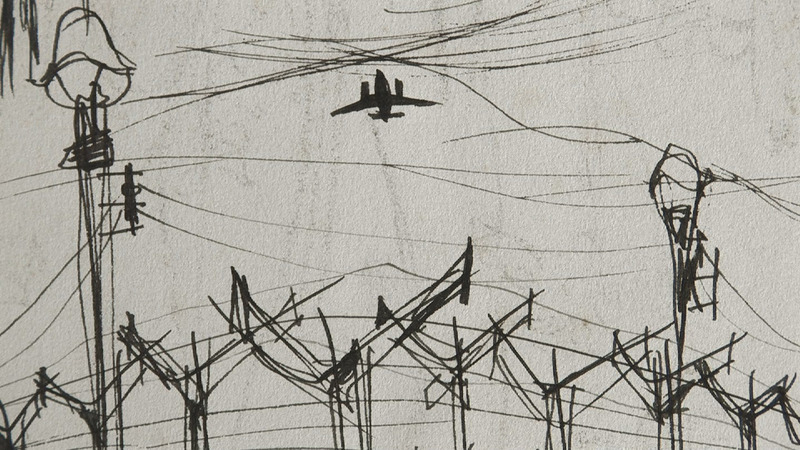

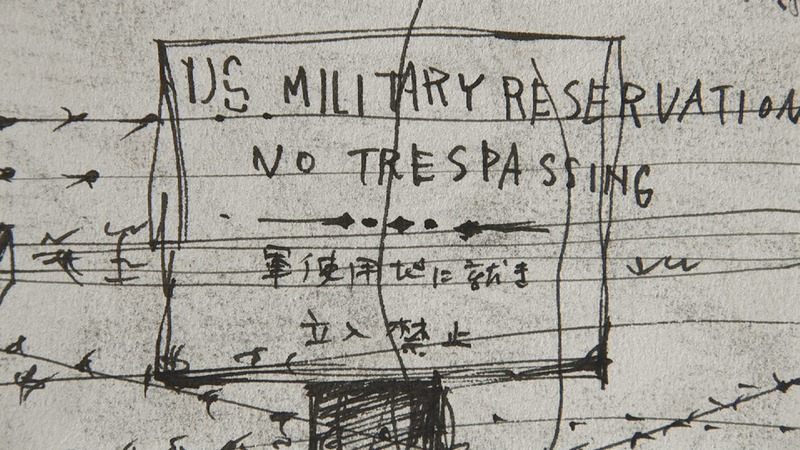

| 1955 sketches of the U.S. military base at Tachikawa, near Tokyo (details) |

|

Sunagawa #5 Nakamura depicted a 1955 confrontation in the protracted military-base protests at Sunagawa in a graphic, realistic manner that he did not always adhere to in his later political paintings. Even here, however, he introduces imaginative detail like the tiny figure of a priest standing in solidarity with local residents who were protesting the confiscation of their land to enlarge the runways at a major U.S. airfield. |

I couldn’t deliver the message and impact I wanted through conventional composition, so I applied the ‘camera eye,’ from both still photographs and movies, to express my outrage.

12 years after the war, we were just starting to recover. There were still shortages of food to eat every day. Otherwise, this kind of incident [meaning the Girard incident] would never have happened.

|

| The Base, 1957 Full painting (left) and detail showing the woman who was killed (right) |

| Nakamura Hiroshi discusses his painting “The Base.” Excerpt from Linda Hoaglund’s 2010 film, “ANPO: Art X War”. |

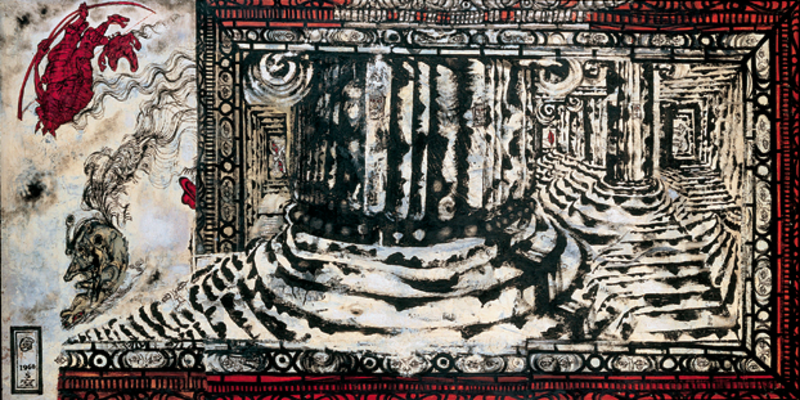

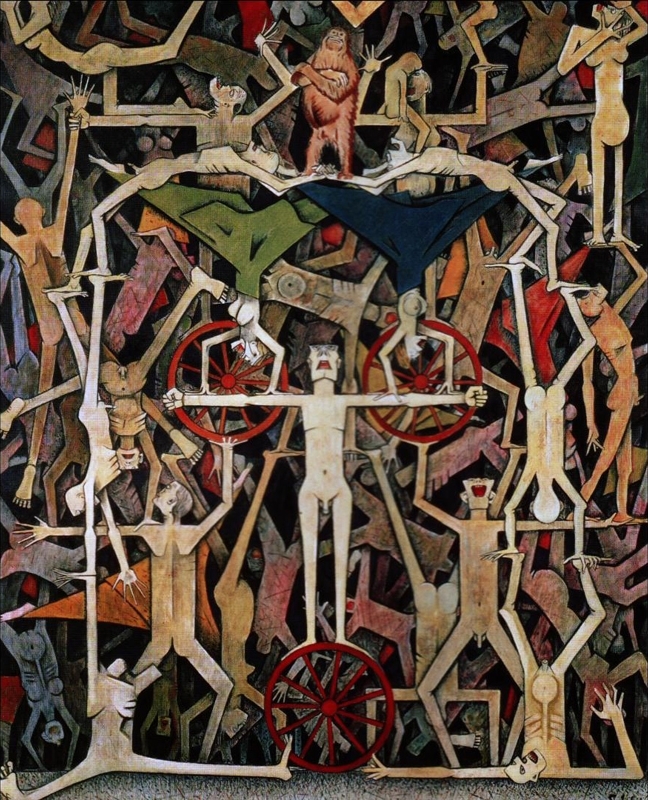

They say after war you have postwar peace, but it’s not just war and peace, like in Tolstoy. You have to add a civil war era in between. So the ANPO protests were a kind of civil war. [“ANPO” is an acronym derived from the Japanese name of the U.S.-Japan mutual treaty.] They used to call these protests a revolution, like the French or Russian revolutions. But in Japan the people never rose up that spectacularly. So you can’t really call it a revolution, but it was certainly a civil war. And you could say that the ANPO struggle was the zenith of that. I painted that as a theme, and titled it “Civil War Era.”

|

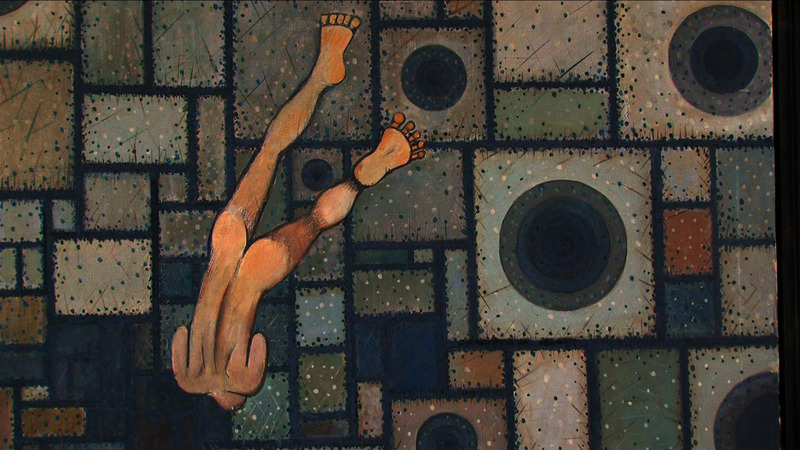

Civil War Era, 1958 |

|

Nakamura Hiroshi (center) is photographed at one of the 1960 demonstrations against renewal of the security treaty. He is standing next to Yoshimoto Ryūmei, a philosopher whose writings and speeches encouraged many artists and intellectuals to join the protests. |

I doubt I would have made paintings with bright red clouds if I hadn’t lived through the firebombing. I remember the firebombing extremely well.

leaving the whole city burned to the ground. There was nothing left. You know those photographs of the ruins of Hiroshima? It actually looked a lot like that. I really can’t believe I’m still alive today.

| Nakamura Hiroshi describes the trauma of firebombing in World War II. Excerpt from Linda Hoaglund’s 2010 film, “ANPO: Art X War”. |

We could transform a black-and-white photo into a color painting. They could display it on the wall. It was very Japanese and must have been exotic.

| Ikeda Tatsuo talks about painting portraits for soldiers. Excerpt from Linda Hoaglund’s 2010 film, “ANPO: Art X War”. |

|

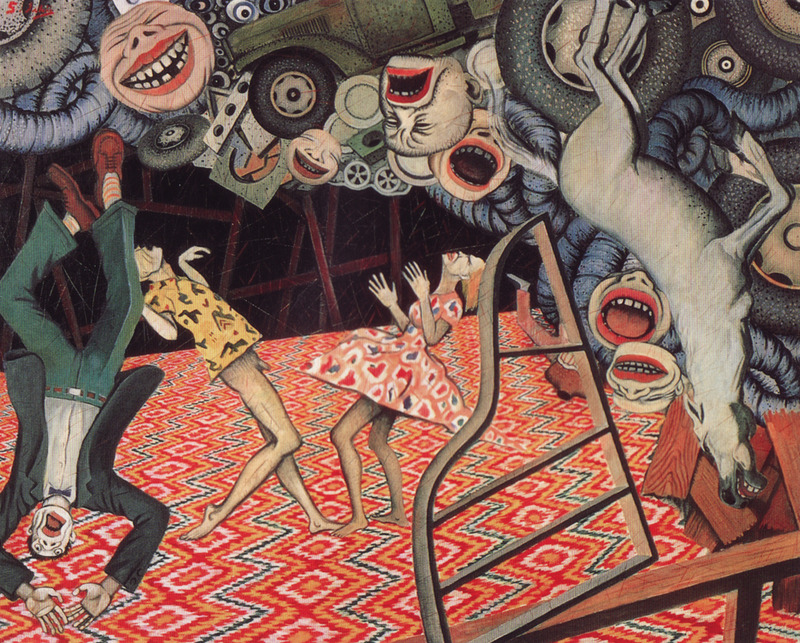

The Tale of Akeboo Village, 1953 |

|

The Tale of New Japan, 1954. Yamashita’s preliminary sketch for The Tale of New Japan (below) was even more salacious than the final painting in its savage indictment of Japan’s obsequious behavior vis-à-vis the Americans. Inclusion of English signs and phrases in the finished work taps into the decadent atmosphere of communities that serviced the U.S. military bases, highlighting the overall corruption of “new Japan.” |

|

|

|

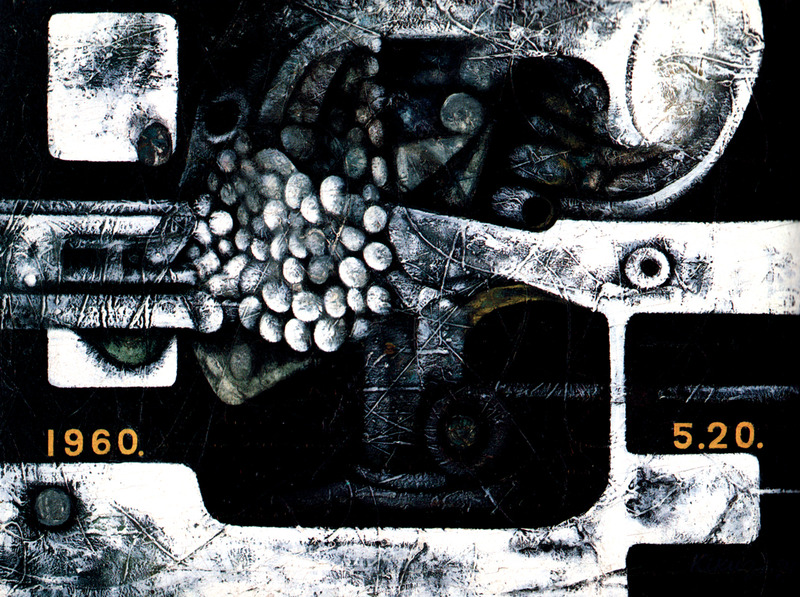

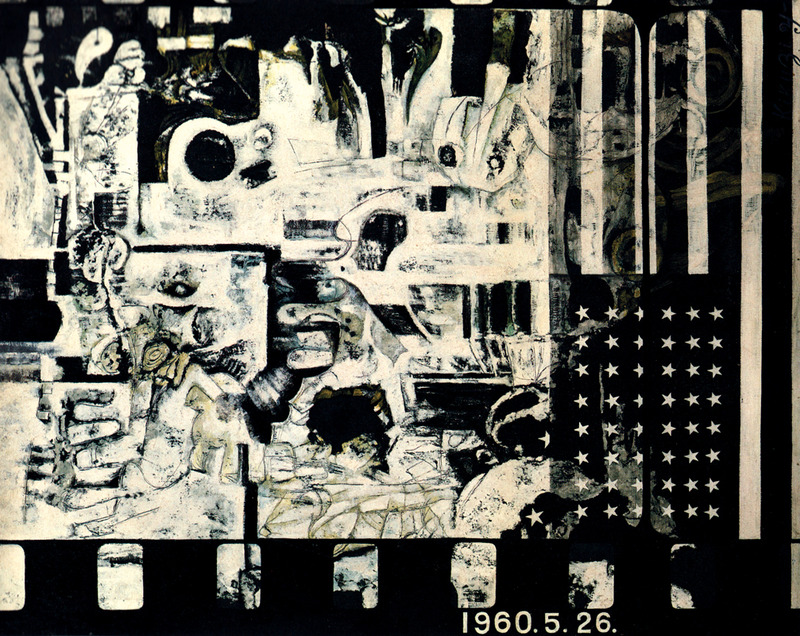

| Firing Angle Campaign May 20 1960, 1960 | Firing Angle Campaign May 26 1960, 1960 | Descent into Darkness, 1960 |

He didn’t talk about it much, but he would cry out from his nightmares at night. He sounded like he was in such pain that I used to wake him. He didn’t tell me directly, but in 1970 he published an article, “A Peephole onto Discrimination.” In it, he wrote about how he had executed a prisoner of war in a very brutal fashion.

I can never forget the day that we buried alive and tortured to death a Chinese prisoner. I had become an animal masquerading as a human being, capable of committing savage acts, but unable to see my own savagery.

He deeply regretted the fact that he couldn’t give his own life by refusing that order. He wanted to take responsibility for what he had done. That became the driving force behind his paintings.

| Yamashita Kikuji’s experience as a soldier is discussed. Excerpt from Linda Hoaglund’s 2010 film, “ANPO: Art X War”. |

|

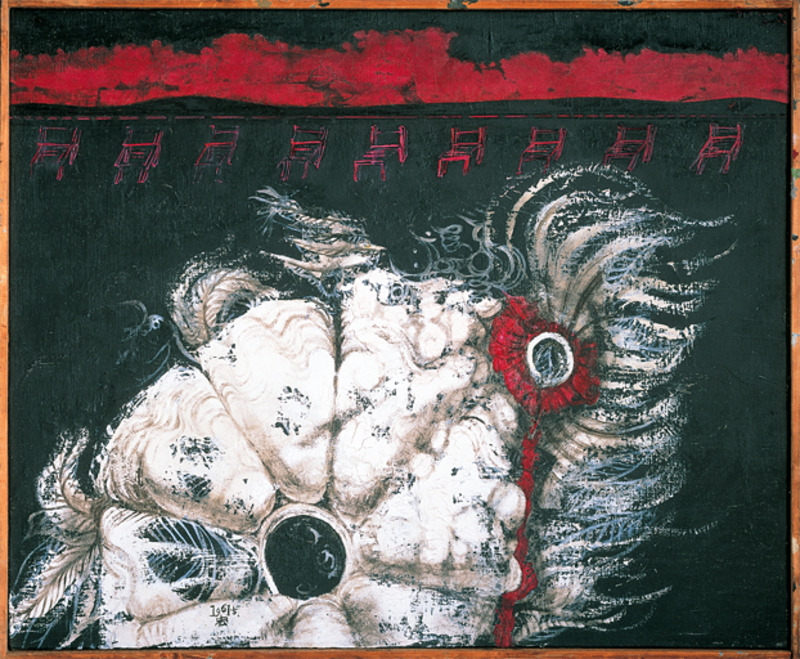

Deification of a Soldier, 1967. To the end of his life, Yamashita was haunted by atrocities he had participated in as a soldier in the war against China—torment that emerges strongly in Deification of a Soldier, painted in 1967 when he was in his late 40s. |

|

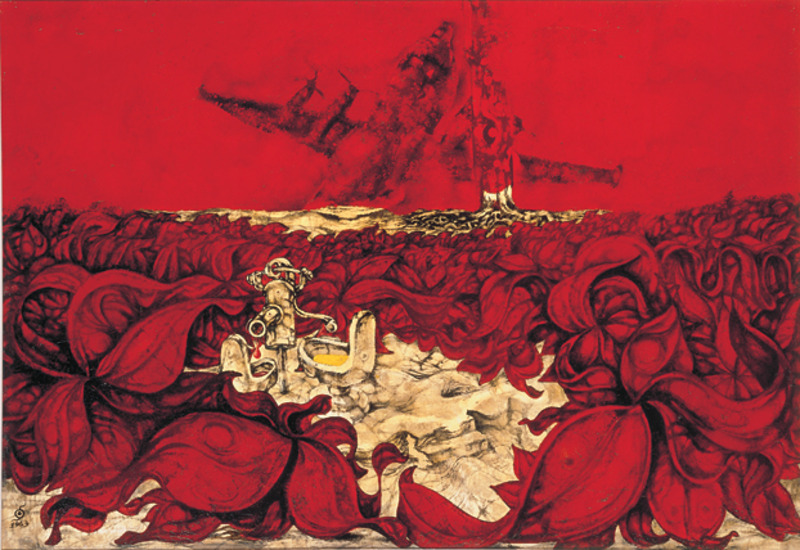

Changing Seasons, 1968. Yamashita’s 1968 painting Changing Seasons offered a surreal and at the same time almost obscenely explicit commentary on Japan’s supine relationship with the United States even after the security treaty had been revised. |

Long after the anti-base movement was deflated by its failure to prevent renewal of the treaty in 1960, Yamashita continued to skewer Japan’s lopsided relationship with the United States. This was the subject of “Changing Seasons,” for example, a surreal yet piercing painting he produced in 1968, one year after “Deification of a Soldier,” at the age of 48.

When I got to know him, he had a nihilistic way of talking and an ironic smile. But he was always making remarks that were right on target. He was only 20 years old, but he’d already read Jean Genet and used to quote him.

| Ishii Shigeo’s sister talks about her brother’s painting and poor health. Excerpt from Linda Hoaglund’s 2010 film, “ANPO: Art X War”. |

The force driving any individual attempting to create a work of art in our modern world must be his desire to revolt against the inhumane mechanism of his society in order to transform it. Without that craving it is impossible to create art.

|

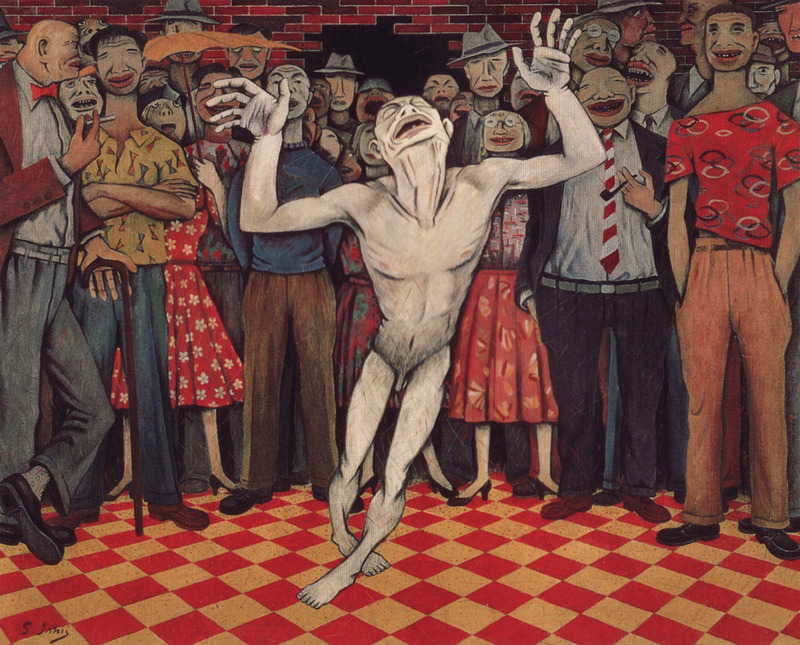

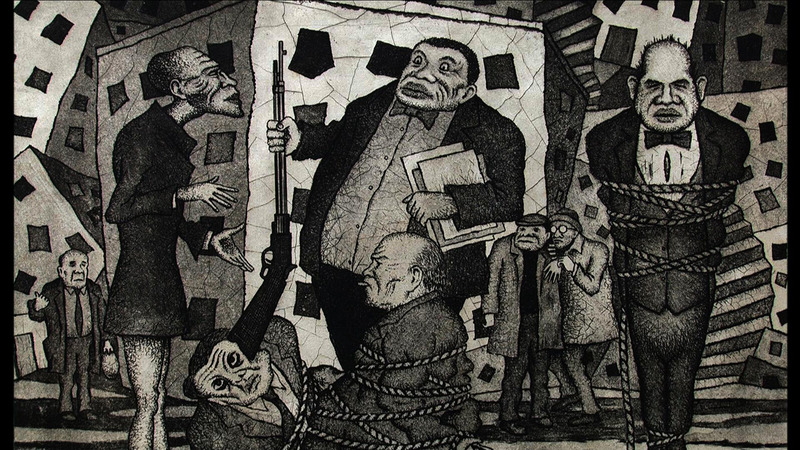

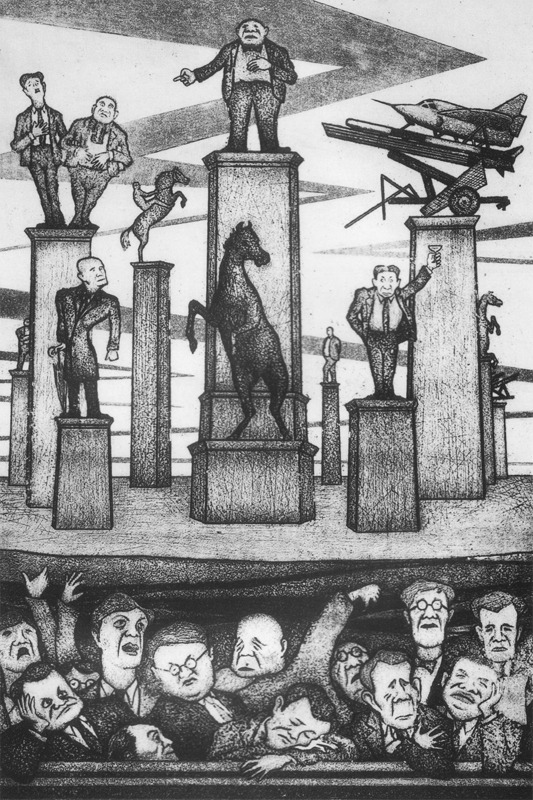

Judgment |

Floating Skulls |

Under Martial Law III |

|

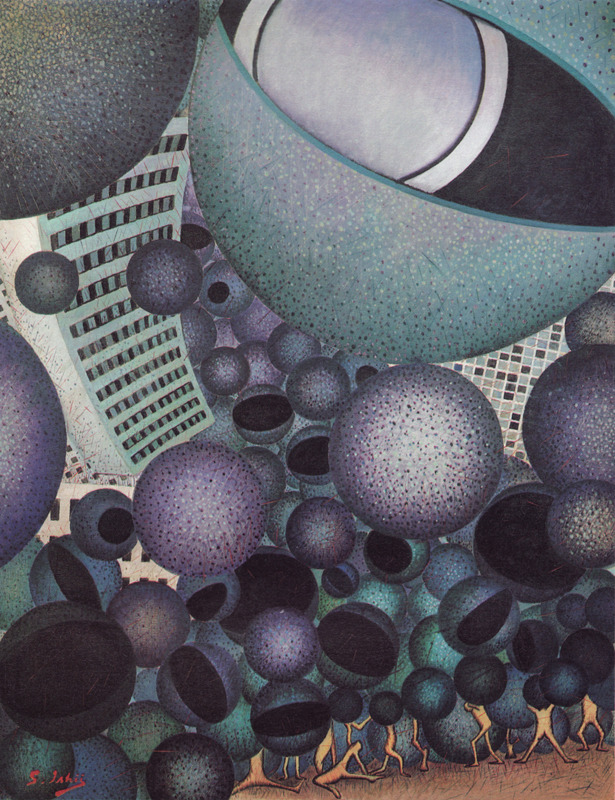

Under Martial Law IV |

The Room |

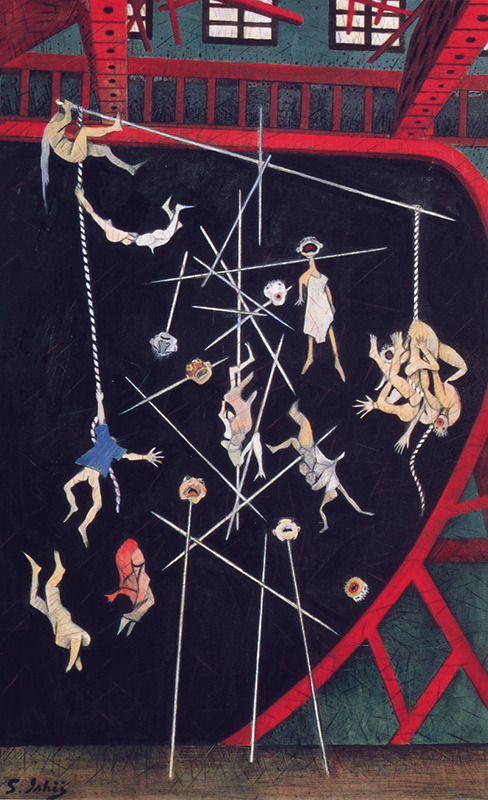

Acrobatics |

The Trap |

|

The Wall |

Fissure (detail) |

Pleasure |

Recommended citation: Linda Hoaglund, “Protest Art in 1950s Japan: The Forgotten Reportage Painters”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 43, No. 1, October 27, 2014.

The author is deeply grateful to the artists and their families for permission to reproduce their artworks in MIT Visualizing Cultures.

Bibliography

Dower, John W. Empire and Aftermath: Yoshida Shigeru and the Japanese Experience, 1878-1954 (Cambridge: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard, 1979), pp. 305-492.

Dower, John W. “Occupied Japan and the Cold War in Asia,” in Dower, Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays (New York: The New Press, 1994), pp. 155-207.

Dower, John W. “Peace and Democracy in Two Systems: External Policy and Internal Conflict,” in Postwar Japan as History, edited by Andrew Gordon (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), pp. 3-33.

Dower, John W. “The Superdomino In and Out of the Pentagon Papers,” in The Pentagon Papers: The Senator Gravel Edition, vol. 5, edited by Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn (Boston: Beacon Press, 1972), pp. 101-42.

Dower, John W. “Contested Ground: Shomei Tomatsu and the Search for Identity in Postwar Japan,” in Shomei Tomatsu: Skin of the Nation, edited by Leo Rubinfien and Sandra Phillips (New Haven: Yale University Press, in association with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2004), pp. 58-77 (touches on anti-U.S.-military-base photography in 1950s and 1960s Japan).

Havens, Thomas R. H. Radicals and Realists in the Japanese Nonverbal Arts: The Avant-Garde Rejection of Modernism (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006).

Packard, George R. Protest in Tokyo: The Security Crisis of 1960 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966).

Schaller, Michael. Altered States: The United States and Japan since the Occupation (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Schaller, Michael. The American Occupation of Japan: The Origins of the Cold War in Asia (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Links

“ANPO: Art X War” official website

“ANPO: Art X War” in Wikipedia

“Art in America” website: Ryan Holmberg, “Know Your Enemy: Anpo,” January 1, 2011

CREDITS

“Protest Art in 1950s Japan” was developed by Visualizing Cultures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and presented on MIT OpenCourseWare.

MIT Visualizing Cultures:

John W. Dower

Project Director

Emeritus Professor of History

Shigeru Miyagawa

Project Director

Professor of Linguistics

Kochi Prefecture-John Manjiro Professor of Japanese Language and Culture

Ellen Sebring

Creative Director

Scott Shunk

Program Director

Andrew Burstein

Media Designer

In collaboration with:

Linda Hoaglund

Author, essay