Introduction by John W. Dower

The following article is a reformatted reprint of a unit developed by MIT Visualizing Cultures, a project focused on image-driven scholarship. Click here to view the essay in its original, visually-rich layout. This is part two of the second in a series of Visualizing Cultures reprints. In the coming months the Asia-Pacific Journal will reprint a number of articles on the theme of social protest in Japan originally posted at MIT VC, together with an introduction by John W. Dower to the series. These are the first in a continuing series of collaborations between APJ and VC designed to highlight the visual possibilities of the historical and contemporary Asia-Pacific, particularly for classroom applications.

Between 2002 and 2013, the Visualizing Cultures (VC) project at M.I.T. produced a number of “image-driven” online units addressing Japan and China in the modern world. Co-directed by John Dower and Shigeru Miyagawa, VC tapped a wide range of hitherto largely inaccessible visual resources of an historical nature. Each topical treatment—which can run from one to as many as four separate units—formats and analyzes these graphics in ways that, ideally, open new windows of understanding for scholars, teachers, and students. VC endorses the “creative commons” ideal, meaning that everything on the site, including all images, can be downloaded and reproduced for educational (but not commercial) uses.

Funding and staffing for VC formally ended in 2013, with around eight topical treatments still in the pipes. These will eventually go online. Overall, including the treatments to come, the project includes a total of fifty-five individual units covering twenty-six different subjects. The China-Japan division will be roughly equitable when everything is in place. (There will also be a two-part treatment of the U.S. and the Philippines between 1898 and 1912.) The full VC menu can be accessed at visualizingcultures.mit.edu.

VC is closing shop for the production of new units at a moment when it was just reaching a “critical mass” of subjects that invite crisscrossing among separate topical treatments. Western imperialist expansion beginning with the Canton trade system, first Opium War, and Commodore Matthew Perry’s “opening” of Japan is potentially one such subject; comparing and contrasting Japanese and Chinese engagements with “the West” is another. The VC units draw vivid attention to political, cultural, and technological transformation in East Asia between the mid-19th and mid-20th century. Many of them highlight graphic expressions of militarism, nationalism, racism, and anti-foreignism. Because the visual resources tapped for these units range from high art to popular culture, and are especially strong in the latter, it is now possible to tap the site to explore the emergence of consumer cultures and mass audiences in Japan and China. This, in turn, calls attention to popular cultures and grassroots activities in general.

One example of the insights to be gained by approaching the VC menu with this comparative perspective in mind is the subject of popular protest in Japan. That is the common thrust of the four separate VC units introduced here. This is, of course, a pertinent subject today, when the mass media in the Anglophone world tends to portray Japan as a fundamentally homogeneous, consensual, harmonious, conflict-averse and risk-averse “culture” (a familiar rendering, for example, in the venerable New York Times).

No serious historian of modern Japan would endorse these canards, which carry echoes of the “beautiful customs” nostrums of Japan’s own nationalistic ideologues. At the same time, however, it cannot be denied that the past four decades or so have seen nothing comparable in intensity or scale to the popular protests in prewar Japan, or the demonstrations and “citizens’ movements” (shimin undō) that took place in postwar Japan up to the early 1970s. How can we place all this in perspective?

The image-driven VC explorations of protest in Japan begin in 1905 and end with the massive “Ampō” demonstrations against revision of the U.S.-Japan mutual security treaty in 1960. The four treatments that will be reproduced in The Asia-Pacific Journal beginning in this issue are as follows:

1. Social Protest in Imperial Japan: The Hibiya Riot of 1905, by Andrew Gordon. We reprint this article with this introduction. Other articles will follow in the coming months.

2. Political Protest in Interwar Japan: Posters & Handbills from the Ohara Collection (1920s~1930s), by Christopher Gerteis (in two units). See Part I here. See Part II here.

3. Protest Art in 1950s Japan: The Forgotten Reportage Painters, by Linda Hoaglund.

4. Tokyo 1960: Days of Rage & Grief: Hamaya Hiroshi’s Photos of the Anti-Security-Treaty Protests, by Justin Jesty.

VC and the Asia-Pacific Journal are committed to bringing the highest quality visual images to the classroom. In establishing this partnership, we anticipate publishing the subsequent units on protest every two weeks. We hope to follow this up with new units in preparation and projected.

John W. Dower is emeritus professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His books include Empire and Aftermath: Yoshida Shigeru and the Japanese Experience, 1878-1954 (1979); War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986); Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999); Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor / Hiroshima / 9-11 / Iraq (2010); and two collections of essays: Japan in War and Peace: Selected Essays (1994), and Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering: Japan in the Modern World (2012).

|

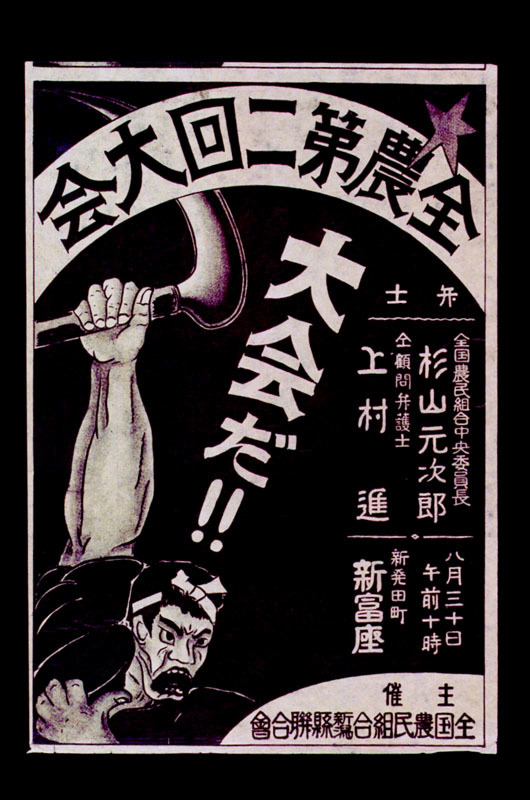

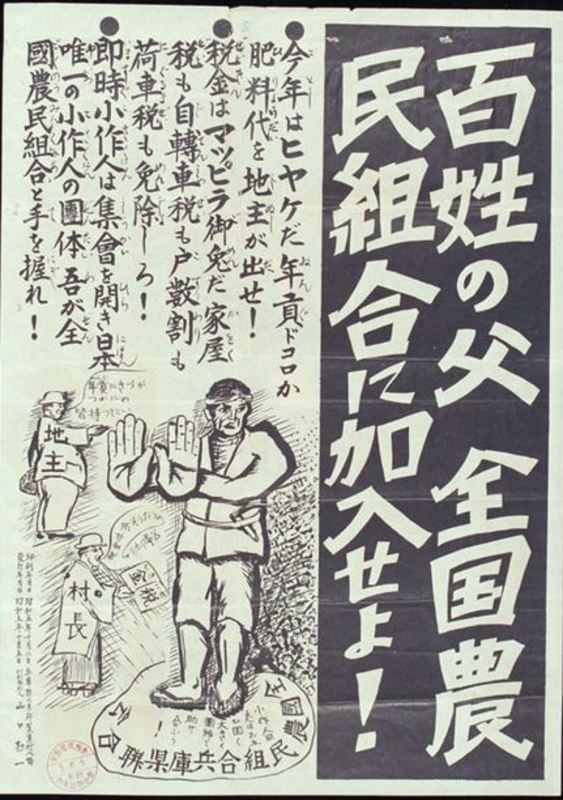

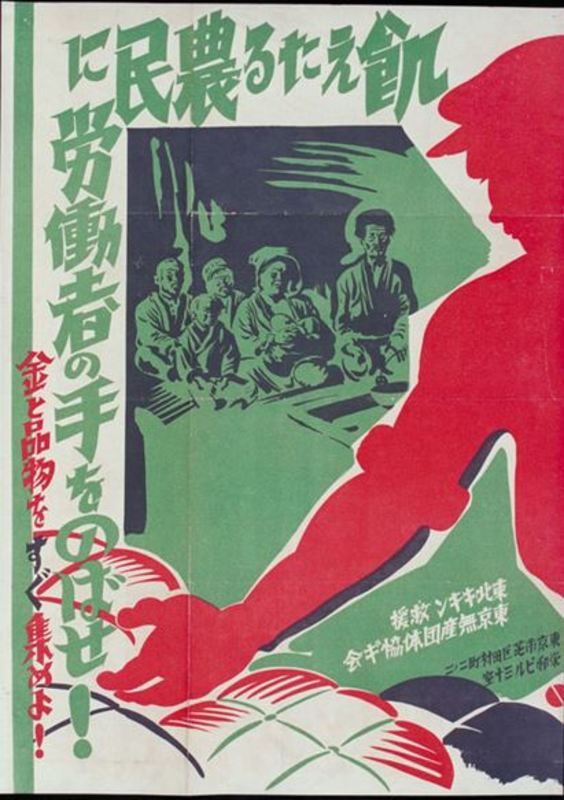

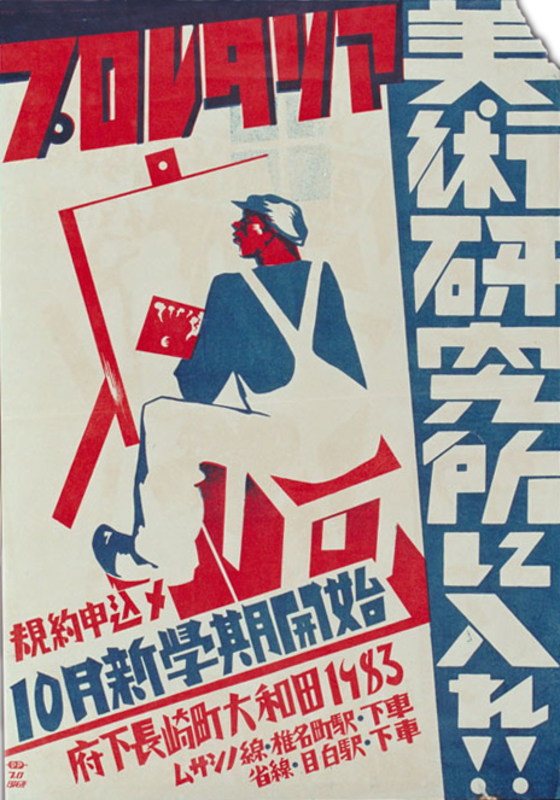

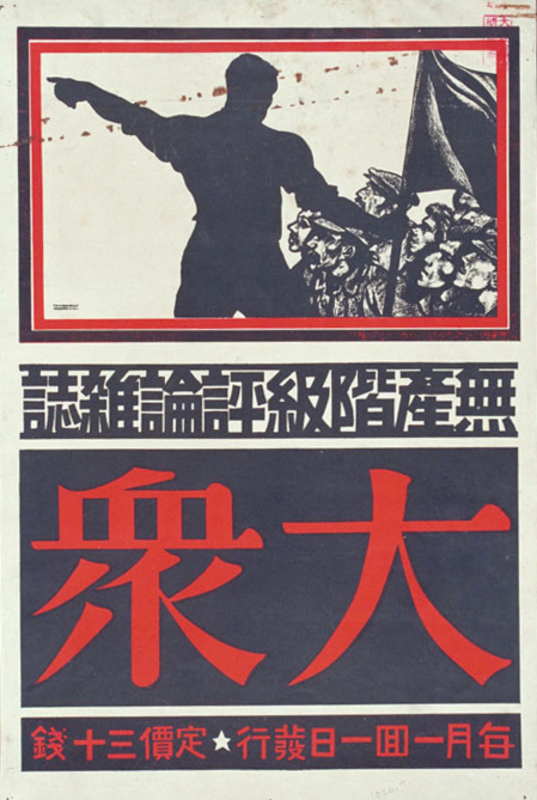

This unit introduces Japanese political graphics from the 1920s and 1930s selected from the remarkable collection of several thousand posters and handbills maintained by the Ohara Institute for Social Science Research at Hosei University in Tokyo. Focusing on leftwing political parties, labor-union and tenant-farmer organizations and protests, and proletarian social and cultural movements in general, the Ohara collection opens a window on the domestic conflict and turbulence that lay beneath the ultimate triumph of militarism and authoritarianism in Imperial Japan.

It is well known that this leftwing protest eventually was suppressed by the state. More than purely textual accounts alone can convey, however, the Ohara graphics help us literally visualize how substantial the contradictions and tensions of the interwar years were. These images and their pithy accompanying verbiage are bold and aggressive in the mode of proletarian art globally in this period. And the range of organizations and activities represented suggests how broad and diversified political and social protest was—while also hinting at the curse of factionalism that helped undermine the left.

The chronological span of this selection, extending from the mid 1920s to mid 1930s, also illuminates how tenaciously leftwing activists carried on in the face of the notorious “peace preservation” legislation of the 1920s, and even after the introduction of militarist governments following the Manchurian Incident and invasion of northern China in 1931. Although these opposition voices were thoroughly co-opted or repressed by the latter half of the 1930s, they were not extinguished. On the contrary, they were the baseline out of which assertive left-of-center movements emerged in the immediate wake of Japan’s defeat in 1945.

This leftwing and proletarian artwork presents a counterpoint to the celebrations of interwar consumer culture and bourgeois developments addressed in Visualizing Cultures units such as “Selling Shiseido” and “Tokyo Modern.” All of these graphics reflect Western influences. More suggestive yet, they all also reflect—from their contrasting perspectives—the complex “modernity” that culminated so tragically in militarism, ultra-nationalism, and authoritarianism.All images in this unit are from the Ohara Institute for Social Research, Hosei University

PARTIES & POLITICS

|

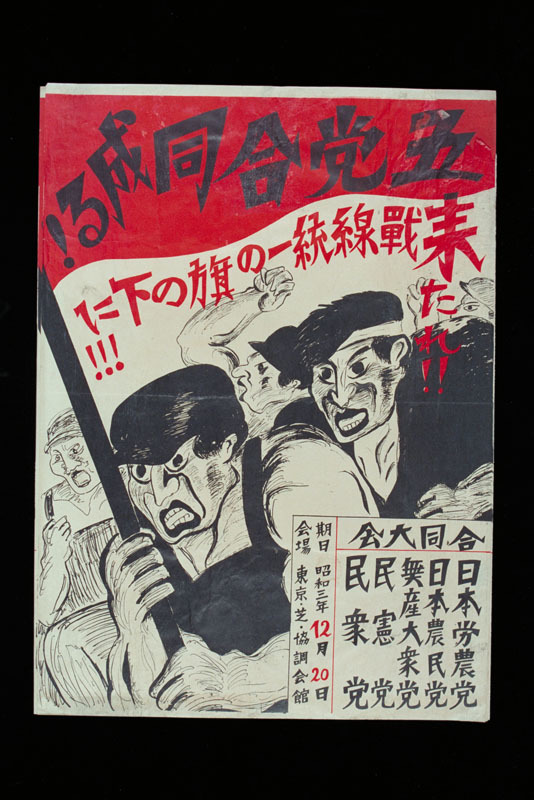

Masculine imagery was a common visual signifier of political strength. This 1928 poster portrays five male workers stridently expressing their support for five leftist parties running in prefectural assembly elections, and extols workers to “Come under the banner of the United Front.” |

Interwar Japan is not usually thought of as a bastion of participatory politics, but the 1920s and 1930s in fact were host to a surprising diversity of political parties. Passage of a General Election Law establishing universal manhood suffrage in 1925 seemed to harken the emergence of a representative democracy for men of all classes.

The turbulent campaign for manhood suffrage—led by coalitions of intellectuals, social reformers, labor unions, tenant-farmer movements, and political parties—compelled the national Diet (parliament) to take notice of the widespread desire for an expanded franchise. Enactment of the 1925 law invested millions of men with the ability to affect social change through electoral politics. On the one hand, this resulted in revitalization of the conservative mainstream parties, the Seiyūkai and Minseitō. At the same time, it also paved the way for formation of many progressive and leftist parties—ranging from the moderate Social Democratic Party (Shakai Minshūtō) to the centrist Japan Labor-Farmer Party (Nihon Rōnōtō) to the rurally based Japan Farmers’ Party (Nihon Nōmintō) to the decidedly communist Labor-Farmer Party (Rōdō Nōmintō).

Although women’s organizations also participated vigorously in the grassroots demands for universal suffrage, women were not given the right to vote until after Japan’s defeat in World War II. Their exclusion from the formal political process led to their being almost literally painted out of the leftwing political posters and handbills of the interwar period, but this was misleading. Women continued to remain significant actors in social movements that supported political parties on both the political left and right.

Despite the 1925 election law, and despite the support they received from labor and farmer organizations, the position of the leftist parties was always precarious. Various factors figured into this. Even as suffrage was being expanded, the Diet was losing power to the constitutionally independent state bureaucracy. More significant still, the 1925 law was enacted in tandem with a Peace Preservation Law that placed various legal constraints on public political activity. The latter law was specifically intended to mute the effect of extending the vote to workingclass men.

The leftist parties and their affiliated organizations also were plagued by internal schisms. The minutia of internal ideological differences often led to bitter fratricidal division. Solidarity also was undermined by mounting economic disparities between rural and urban areas—to the point that the urban-centric parties and labor unions often seemed blind to the plight of rural farmers plagued by low crop prices, high rents, disproportionate tax burdens, and desperate poverty.

Such fractional strife, coupled with government repression, caused the dissolution of many radical parties even before the first general election to be held under universal male suffrage took place in 1928. Still, several restructured parties on the left—notably, the Labor-Farmer Party, the Japan Labor-Farmer Party, the Socialist Party, and the Social Democratic Party (Shakai Minshūtō)—survived to take part in that widely heralded election.

In 1926 rural labor activist Asanuma Inejirō attempted to create a basis for a leftist intervention in rural Japan by founding the Rōnōtō (Japan Labor-Farmer Party), which he envisioned as a means to bridge the growing economic and cultural chasm between rural farmers and urban workers. His effort to create a formal alliance between the labor movement and leftist political parties backfired when the labor federation Sōdōmei ordered the Japan Labor-Farmer Party leadership to resign their membership in the federation and respect the federation’s status as a non-political organization. This further inflamed the fratricidal vitriol in the leftist press that characterized the lead-up to the 1928 general elections.

Despite a fresh field of new political parties in the nationwide 1928 election, the established parties lost little ground in the popular vote. Only eight of the 88 non-mainstream candidates fielded—from seven different parties (the four main leftist parties and three local independents)—won a seat in the House of Representatives, where the total number of seats was 466. Although leftist candidates did slightly better than they had done in the 1927 prefectural assembly elections (winning 5 percent as compared to 1927’s 3.9 percent of total votes cast), they lacked the name recognition and established local constituencies of the mainstream parties.

Unsurprisingly, the radical positions of the leftwing parties also cut them off from the largest source of campaign funding: the corporate conglomerates known as zaibatsu. The established conservative parties—the Seiyūkai backed by the Mitsui zaibatsu and the Minseitō backed by Mitsubishi—held a monopoly on campaign finance. These handicaps were compounded by repressive state interventions in the form of disruption of meetings and arbitrary arrests. Although the proletarian parties attempted to regroup in the wake of overwhelming defeat in 1928, the government banned the communist influenced Labor-Farmer Party before the end of the year, and the remaining leftist parties remained divided over ideological issues.

Another factor contributing to the poor showing of the political left in 1928 was the inability, or unwillingness, of the leftist parties to cooperate, which resulted in their often being unable to strategically place candidates in a national field. Many districts saw leftist candidates run against each other, which usually enabled an established candidate to win. As if to add insult to injury, it is also doubtful that the voters themselves were fully aware of the differences between the various parties, a problem the Minseitō in particular exploited by presenting itself as the only viable party to improve the lot of the common people.

Political weakness helped to precipitate even worse electoral results in the 1930 general election. The worldwide depression of the early 1930s prompted the labor federation Sōdōmei to withdraw official support for political parties and adopt a policy of “non-political unionism”. Sōdōmei retained informal ties with a few leftist parties, but also with the Minseitō, and thus leftist parties were not even assured of dependable backing from labor unions

The late 1920s and early 1930s thus saw a cacophony of leftist parties with bewilderingly similar names. Some newly named parties represented short-lived mergers, and almost none survived past 1932. Their campaign posters featured agendas and images ranging from stridently radical to moderate, although usually with a consistent critique of capitalism and explicit appeal to workers and tenant farmers. The only nominally leftist party that was allowed to continue operating through the 1930s was the Social Masses Party (Shakai Taishūtō), which emerged out of a 1932 merger and promoted an essentially centrist agenda calling for agrarian reform alongside close ties with the urban middle class, especially small shopkeepers who felt squeezed out by the economic dominance of the zaibatsu conglomerates. Although this party initially called for cuts in military spending to help pay for agrarian reform, it also cultivated ties with the so-called Control Faction (Tōseiha) in the imperial army and supported Japan’s expansion into Manchuria and eventually all of China—collusion that helps account for its survival when more radical parties on the left disappeared from the scene.

LABOR ACTIVISM

The spontaneity and decentered nature of the explosive 1905 Hibiya Park riots in Tokyo demonstrated the political diversity of public protest in modern Japan, as well as the impact of such protest upon policymakers and the popular media. While the state used the Hibiya riots as an excuse to further crack down on political activists, the founding of the Yūaikai (Friendly Society) by Christian convert Suzuki Bunji in 1912 helped to precipitate a period of union activism. Ostensibly apolitical, Suzuki’s organization was well timed: lower-class neighborhoods in Osaka and Tokyo were beginning to take on the characteristics of an industrial working class, and when World War I (1914 to 1918) opened new markets for Japanese industries the booming economy combined with a more liberal political moment to allow for an interlude of sustained union activism in the heavy industrial sectors.

Wealth from the war boom, however, did not spread evenly. Nationwide rice riots followed the end of the boom in 1918 and drew attention to the material concerns of the urban working class. This helped precipitate vigorous reform movements aimed at quelling what corporate managers and government officials increasingly feared to be a proletariat ripe to give birth to leftist movements.

Yūaikai organizers benefited from the development of new patterns of traditional forms of lower-class collective action (nonunion disputes), as well as from company initiatives to replace traditional labor bosses with systems of direct managerial control. The success of the Yūaikai between 1912 and 1918 was also due in part to the emergence of what historian Andrew Gordon has called an “ideology of imperial democracy,” which enabled male and female workers to conceive of themselves as possessing full political rights within a political system that still excluded them.

The Yūaikai also established the first union-affiliated women’s organization, which sought to encourage more women to support the labor movement by creating an organization dedicated to their interests. Although the 1916 Factory Law had established minimum employment standards protecting women and children, the law had limited provisions for enforcement. Managers seeking greater control over their workforce continued to have the most success in asserting authority over their female employees.

Women’s activists affiliated with the Yūaikai sought to help wage-earning women by advising on policy decisions, developing organizing literature, and participating in key strikes and walkouts throughout the 1920s. While the Yūaikai women’s department established important precedents for women’s union activism, they succeeded in persuading no more than a few thousand wage-earning women to join unions.

By the mid 1920s, the Yūaikai—renamed the Japan Federation of Labor (Nihon Rōdō Sōdōmei, or Sōdōmei for short) in 1921—had grown to represent nearly a half million industrial workers in the Osaka and Tokyo metropolitan areas. Organized strike actions spiked in 1921 when organizers coordinated a successful strike by 30,000 dockworkers at the Kawasaki-Mitsubishi shipyards in Kobe. In the mid and late 1920s, labor leaders staged a number of strikes in the heavy industrial and transportation sectors that drew national attention and led to a series of unprecedented coordinated campaigns for political change.

Despite conservative opposition to the emerging alliance between leftwing parties and organized labor, unions were a significant force behind the successful campaign for universal manhood suffrage that culminated in 1925 and extended the vote to every male over the age of 20. Whereas the Yūaikai advocated cooperation between labor and management and promoted a moderate policy of mutual assistance and worker education Sōdōmei soon adopted a more radical and militant agenda emphasizing class struggle. This radicalization reflected the dramatic industrial expansion that took place in Japan in the early 20th century, especially during and after the war boom stimulated by World War I. The factory labor force of male workers in heavy industry grew rapidly. Militant workers challenged the Yūaikai’s policy of conciliation. And the influence of Marxism, Leninism, and Communism following the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia contributed immeasurably to the enhanced attraction of leftwing ideologies (and imagery).

By the mid 1920s, the nationwide labor movement claimed nearly a half million members. In addition to organizing strikes and other protest activities, unions joined other leftists in promoting outreach activities such as youth organizations and cooperative schools. Partly in response to this agitation—and partly spurred by changing production technologies and new theories of labor-management practices—the state and private sector intensified their imposition of hierarchical systems of control. Combined with outright repression, especially after adoption of the Peace Preservation Law in 1925, this turned the late 1920s and early 1930s into a period of intense but increasingly futile labor protest. This confrontation was compounded, of course, by the inexorable march to all-out war that followed Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

Sōdōmei carried on until 1940, making it the longest surviving of Japan’s prewar unions. Its durability, however, was facilitated by the increasing takeover of leadership by rightwing elements. Beginning in the mid 1920s, the federation experienced splits and the hiving off of leftist and then moderate member unions. In the 1930s, it was again advocating collaboration with the state and managerial class, which now presided over an economy that was increasingly directed to production for war. In 1940, Sōdōmei and other still existing unions were dissolved and replaced by the ultranationalistic Industrial Association for Serving the Nation (Sangyō Hōkokukai, popularly known as Sampō), which stressed the importance of harmony in labor-capital relations, with particular emphasis on the “family” nature of every enterprise.

Even during the years of intensified government repression that took place after the passage of “peace preservation” legislation in the mid 1920s, however—and even after the invasion of Manchuria—the visual record of the proletarian movement that has been collected in the Ohara archives makes clear that the radical rhetoric and imagery of labor organization and agitation continued to find expression until it was finally snuffed out in the later half of the 1930s.

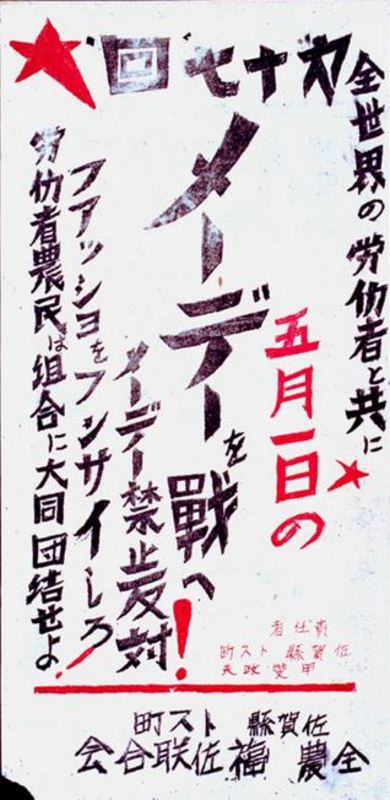

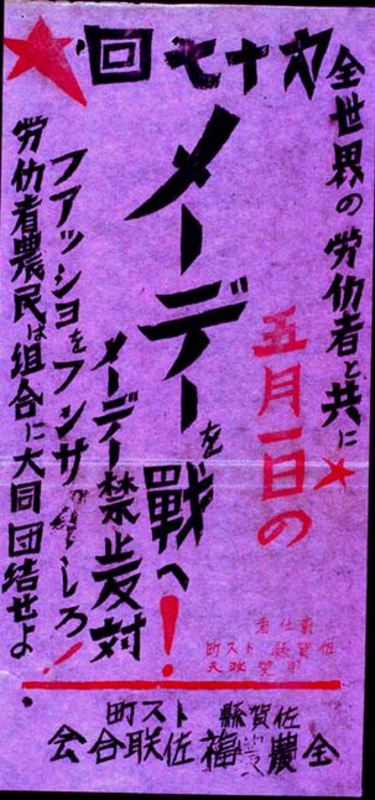

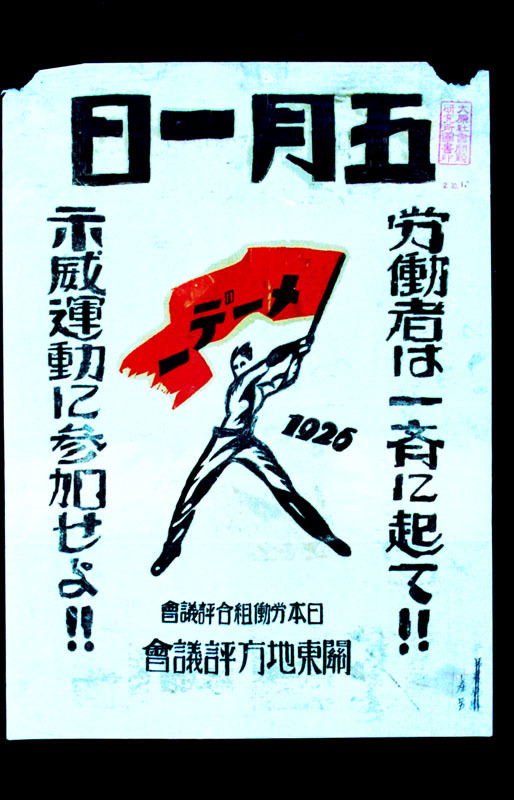

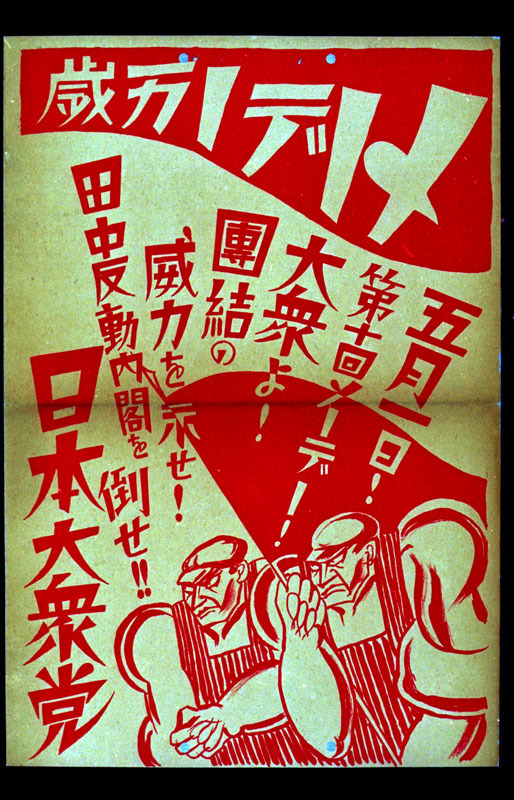

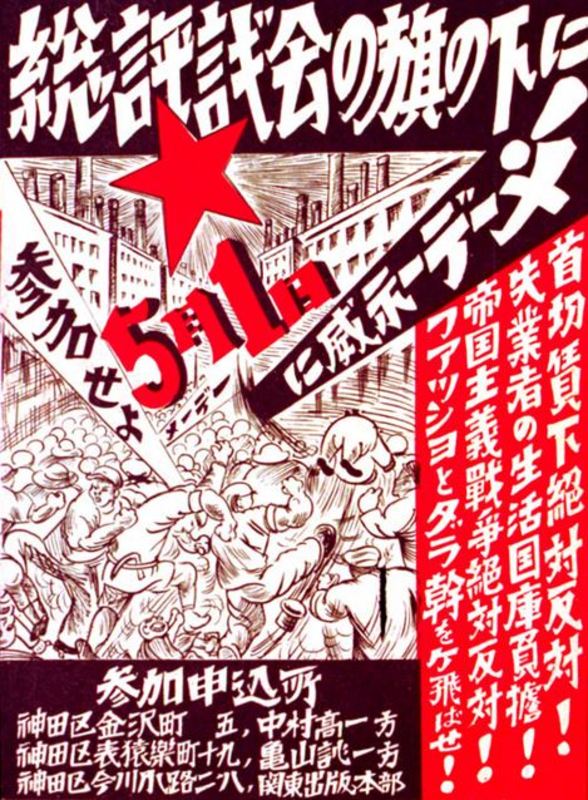

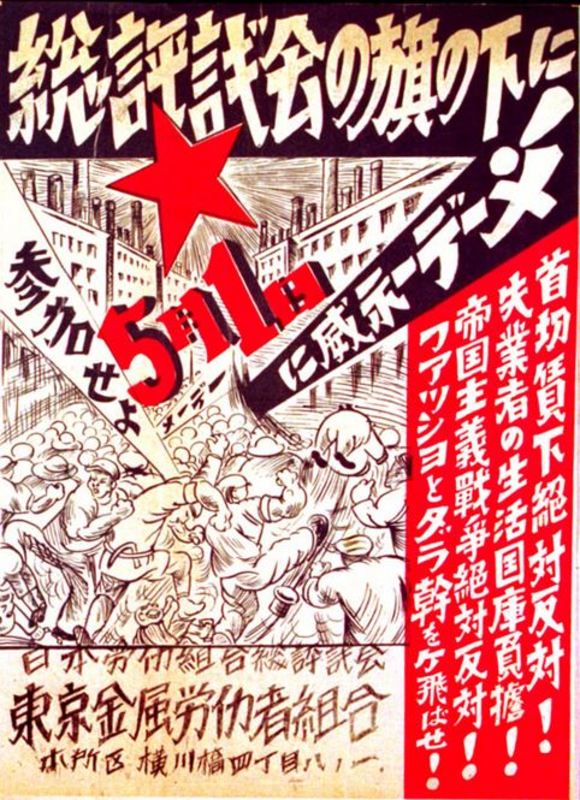

Other labor-related graphics from the 1920s and 1930s—both formal and informal in nature—also call attention to the tenacity of radical labor expression well into the 1930s. Japanese workers began celebrating May Day (also known as International Workers’ Day) on May 1, 1920, for example, and continued to do so annually until 1936, when the practice was prohibited.

|

|

|

|

| 1926 | 1927 | 1929 | 1930 |

|

|

|

|

| 1931 | 1931 | 1932 | 1937 |

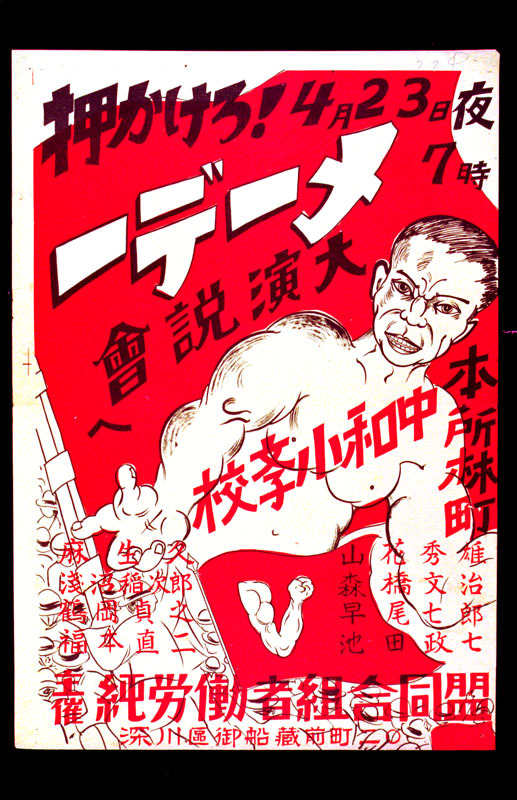

As the 1937 May Day leaflets indicate, the more formal poster-style graphics of the labor movement were complemented by a less polished category of exhortatory agitation disseminated in the form of handbills and flyers. Many of these called for participating in or supporting localized protests or disputes. Some were clarion calls for a general strike. These throwaway leaflets reflected handiwork by both fairly sophisticated artists and crude amateurs. The verbiage ranged from terse to wordy, and the visuals—where there were any—were usually harsh and sometimes vicious.

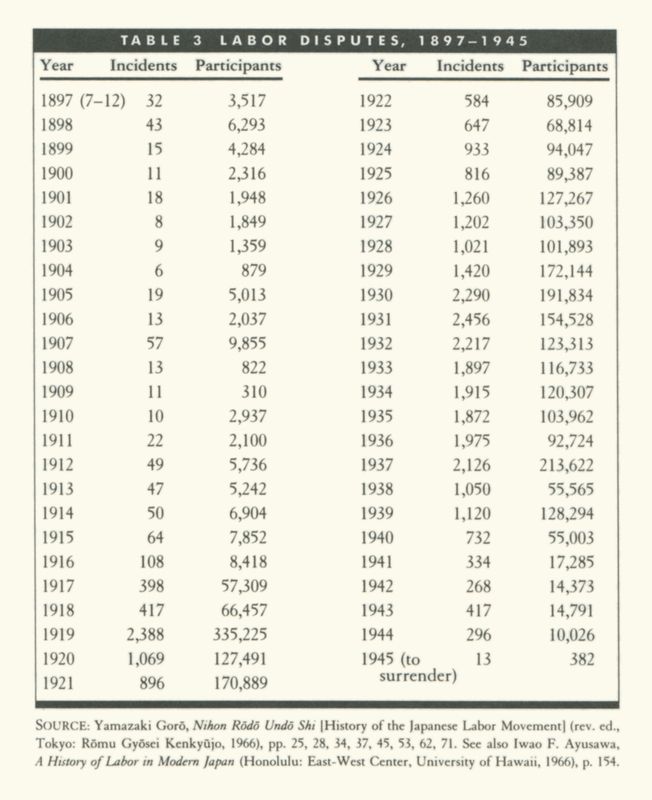

As with the proletarian posters, dissemination of these more informal graphics extended into the mid 1930s. In this respect, they too call attention to the tenacity and diversity of the labor movement even after the heavy hand of the state intruded and organizations like Sōdōmei moved in collaborationist directions. This is not, in fact, entirely surprising when one keeps in mind the persistence of poverty in Depression-era Japan and the considerable variety of labor protests that accompanied this misery. In 1937, for example—the year Japan launched all-out aggression against China—it is estimated that some 2,126 “incidents” of labor protest took place, involving over 213,000 participants.

This is the milieu in which, even as workers were being drafted for war, protest continued to be expressed. Labor unions may have been crumbling, or caving in to pressure, or being won over by patriotic appeals. More than a few protests may have been relatively restrained, or even brief and largely symbolic in nature. In the eyes of the watchdogs of the state, however, these numbers were still alarming. In the dossiers of the thought police, after all, 2,126 disputes in a single year averaged out to almost six a day. Indeed, it was domestic unrest such as this that led the militaristic ideologues to pump up the mythical rhetoric of “one hundred million hearts beating as one.”The economic dominance of the four largest zaibatsu (Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Yasuda) along with the rise of militarist governments in the 1930s closed Japan’s brief moment of “imperial democracy,” and pressed labor unions further to the periphery of the political landscape. This trend was compounded by militarist planning for economic self-sufficiency from the late 1920s, which renewed the state’s emphasis on development of heavy industry. By the late 1930s the government was well into the process of shutting down independent political parties, unions, farmer cooperatives, and even business associations, replacing them with state-controlled organizations created to mobilize the masses in support of military expansion into China. As one consequence, employment patterns began to shift toward an industrial workforce dominated by males. The militarist governments that took Japan into war in the late 1930s provided significant economic stimulus for crucial industrial sectors and created a large cadre of planners, managers, and skilled blue-collar workers that would contribute greatly to postwar reconstruction and recovery. Before that could happen, however, the war came home and destroyed far more industrial capacity than it created.Japan’s full-scale invasion of China in 1937 launched the nation onto a path that eventually led to its attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entrance into World War II. Japan’s long march to war seems in retrospect to have been inevitable; yet, the decade was nevertheless witness to union activism at odds with the interests of the emerging militarist state. While the aggregate percentage of workers who belonged to unions did not grow significantly after 1931, the number of workers willing to launch and maintain workplace disputes exploded between 1930 and 1932, and remained steady until 1938. While not a clear indicator of a strong labor movement per se, the number of workplace disputes indicates a persistence of collective action at the social base even in the face of an increasingly repressive state. While the number of long strike actions also indicates employer ability to resist worker activism, it is nonetheless evidence of stronger local unions able to hold out longer in the face of employers who, in law and material resources, held all the cards.

By 1938 political strife and worker unrest had reached the point that militarist factions led by the General Staff of the Imperial Army and Navy who had seized control of the government felt they could no longer tolerate. In 1940 the state outlawed labor unions and political parties, and replaced them with a network of state-sponsored patriotic service organizations. Independent political parties were abolished and all remaining labor unions were folded into the patriotic “sanpō” foundations. Although sanpō was little more than an excuse for the state to legitimize the dissolution of the labor movement while ameliorating very little of the dangerous working conditions, low wages, and managerial abuse faced by Japan’s wartime industrial workforce, some worker representatives nevertheless were able to use traditional styles of nonunion activism—intense negotiation tactics and even strikes—to temporarily buttress what otherwise were rapidly eroding wages and working conditions. The prewar political experiences of Japanese workers prepared them to take advantage of the legal protections granted to them by the Allied Occupation in 1946.

FARMERS’ MOVEMENTS

As indicated in the post-World War I proliferation of “labor-farmer” political parties, opposition movements by an emerging urban working class were complemented by leftwing protests aimed at mobilizing impoverished farmers in the countryside.

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which overthrew the samurai-dominated feudal system that had governed the country for eight centuries, Japan’s leaders embarked on a path of Westernization and industrialization that privileged the urban sector over the more backward agrarian economy. The new modernizing state was heavily dependent on taxes disproportionately extracted from the rural sector, and many farmers were hard pressed to make ends meet. As time passed, the plight of many of them became worse rather than better.

Whereas World War I stimulated a war boom in Japan’s industrial sector, it simultaneously brought greater setbacks to much of the rural political economy. Land rents as well as the costs of tools and fertilizer accelerated the descent of many small land holders into foreclosure and tenancy. Higher rents exacted in kind by an emerging cadre of new landlords forced the swelling class of tenant farmers into the position of having to buy rice to feed their families.

Hunger followed mounting poverty closely, and was among the major reasons behind the rural unrest that culminated in the nationwide rice riots of 1918. Although the government interceded by cutting the price of rice in half, price controls evaporated when economic recession hit Japan in the early 1920s. The recession exacerbated rural hardship, and one conspicuous result of this was a mounting exodus of poor farmers who migrated to the cities to seek factory work. With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, rural Japanese suffered a further blow from the collapse of the export market for silk, which was one of the major by-employments that farm families had relied on for supplemental income.

Many political activists devoted themselves to organizing grassroots associations of poor farmers; and more than a few espoused the necessity of forging strong labor-farmer alliances. Beginning in 1921 and continuing into the early 1940s, the number of outright tenancy disputes numbered over 1,500 annually—reaching an annual peak of around 6,000 in the mid 1930s. However one might break down these numbers, they were certainly sufficient to alarm the ruling elites—especially when paired with tandem incidents of protest by urban workers.

Beginning in the 1920s, activists and organizers spanning a broad ideological spectrum devoted attention to rural problems and the desirability of building bridges between poor farmers and blue-collar workers. By the early 1930s, their factionalism mirrored the fratricidal rifts that plagued the urban labor movement and precipitated the splintering of the movement into eleven “proletarian” parties, several of which included “farmer” in their names. Centrist and rightwing socialists vied with hard-line communists; parties changed their names with bewildering speed; and by the mid 1930s, as everywhere on the left, many erstwhile socialists found it expedient to change their colors to “national socialist” and throw their support behind the militarists and their expansionist agenda.

Still, the longer-term legacy of rural unrest was substantial. To a very considerable degree, sweeping land-reform legislation introduced by U.S. occupation reformers following Japan’s defeat in 1945 was motivated by fear that, absent such reform, the countryside might well erupt in “Red” revolution.

Posters in the Ohara collection that focus on interwar discontent in the countryside give a fair sense of why such fears arose.

CULTURAL MOVEMENTS

In retrospect, one of the striking features of 1920s and 1930s Japan is the extent to which the rise of militarism took place in the midst of developments we now associate with an efflorescence of “modernity” worldwide in the early decades of the twentieth century, especially following World War I. Much of Japan, especially the economically less developed countryside, was indeed relatively backward—even, as Marxists then and later put it, “semi-feudal.” The counterpoint to this, however, was the conspicuous emergence of a consumer culture and popular mass culture that in many instances reflected cosmopolitan influences.

Although Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s most vibrant metropolitan hubs, led the way in these developments, the allure of modernity penetrated provincial cities and seeped down to remote rural villages. One reason this happened so quickly was the revolution in mass communications. Public radio was introduced in the mid 1920s, and soon reached every corner of the country. The print media, stimulated by new production technologies, began addressing a mass audience through newspapers, magazines, and books aimed at carefully targeted readers. Cinema entered the scene, in the form of both imported foreign films and development of an indigenous industry. Popular theater flourished in the cities, including many adaptations of foreign playwrights.

Many of these developments moved in flashy and largely bourgeois directions—like the flourishing of “café culture” and the vogue of the “modern girl” and “modern boy,” all of which were transparently influenced by 1920s popular culture in the United States and Europe. From another direction, the devastating Kanto earthquake of 1923, which leveled most of Yokohama and a good part of Tokyo, had the ironically salutary effect of stimulating the reconstruction of a “new Tokyo” that was more Westernized and up-to-date than the ruined old city had been. Before the militarists took over, many observers regarded Japan as being embarked on a promising “modern” trajectory.

At the same time, this modernity obviously was riddled with contradictions. Inequalities in the distribution of wealth became more conspicuous, and large numbers of rural and working-class families could only look upon the material benefits of so-called progress with envy. Even here, however, the organizers of protest movements tapped into international trends for instruction and inspiration.

Unsurprisingly, they drew on ideas associated with the broad range of leftwing thought that had developed in the West—including Christian reformism; rightwing, moderate, and leftwing socialism; Marxism and hard-line Leninist communism; and eventually (and perversely) state-centered national socialism.

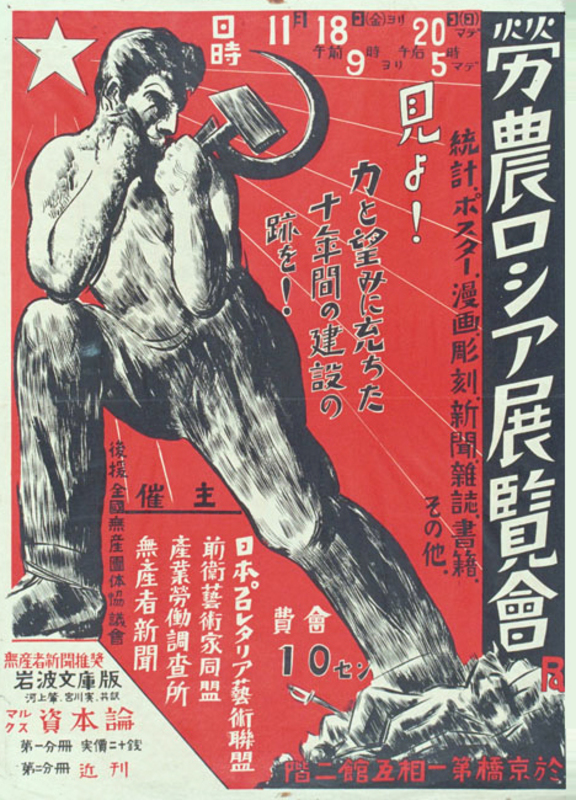

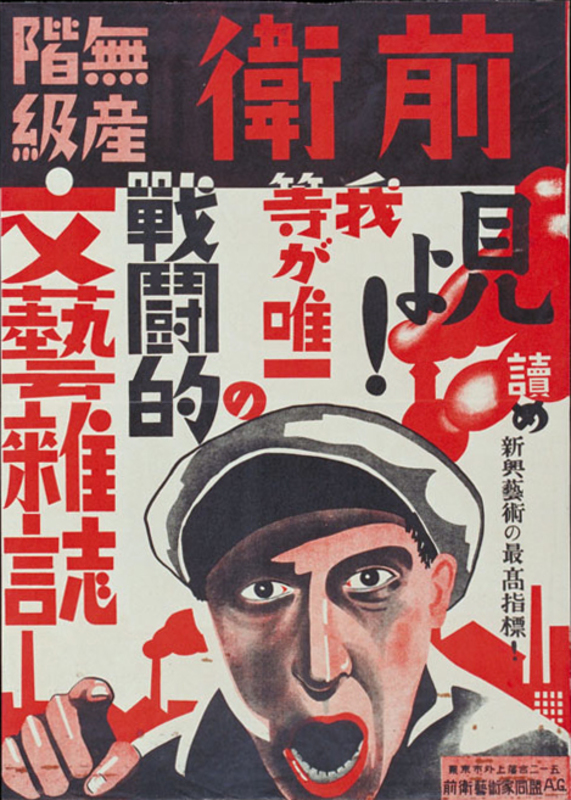

As the graphics in the Ohara collection remind us, these political and intellectual influences usually came wrapped in a distinctively cosmopolitan aesthetic sensibility that revealed, in this case, the influences of avant-garde and proletarian art.

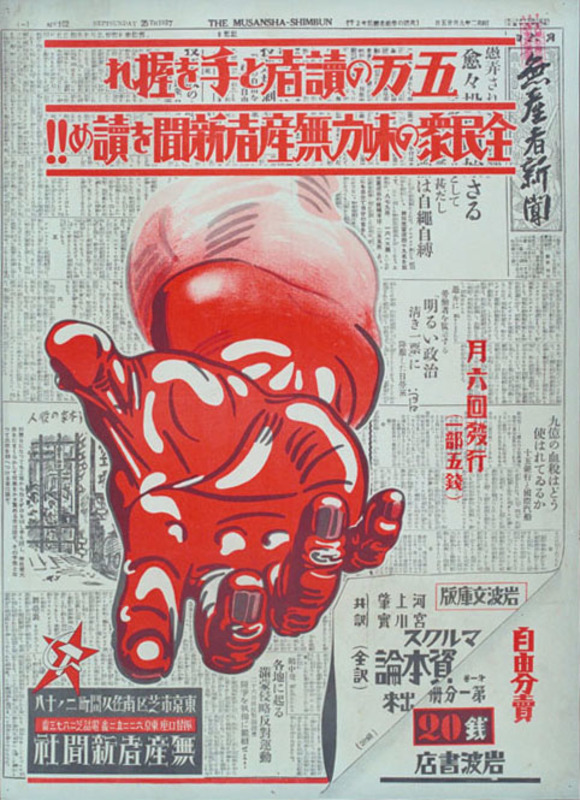

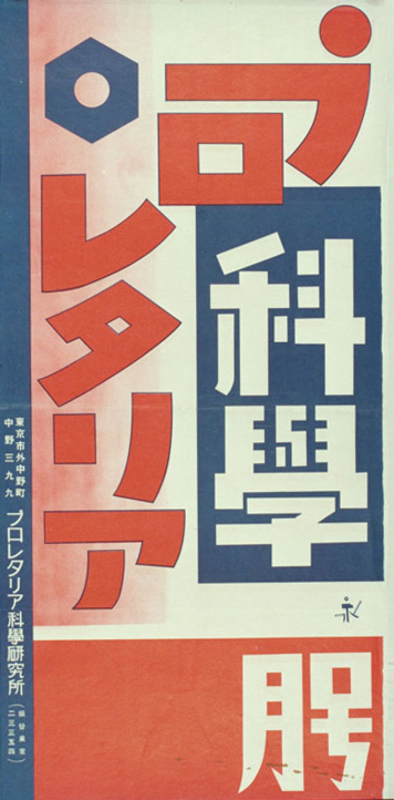

Leftwing Publications

The relatively sophisticated textual content on interwar political graphics is a reminder of the fact that by this date the Japanese populace as a whole was impressively literate. This literacy traced back to educational reforms introduced in the latter half of the 19th century, and it extended to both blue-collar workers and farmers. As a consequence, leftist parties and labor-farmer associations generally churned out a variety of newsletters, newspapers, and magazines to keep their supporters up-to-date.

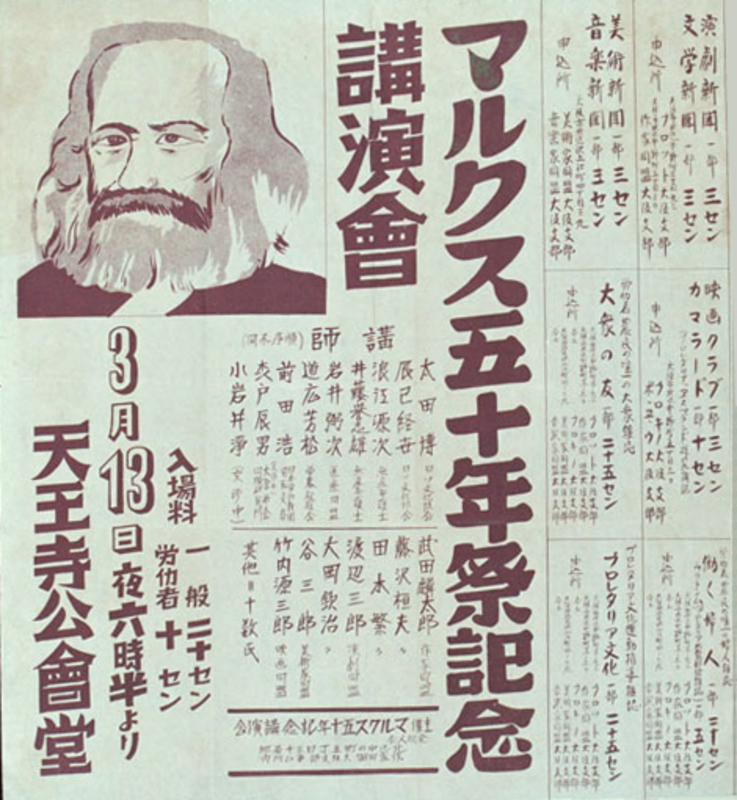

At the same time, the rise of a new urban intelligentsia was yet another familiar phenomenon of modernity. And a substantial portion of this intellectual production involved not only publishing original articles and books of a leftwing nature, but also translating many of the basic Marxist, socialist, and communist texts that defined radical thought in the Western tradition. Marx, Lenin, and a great many other radical theorists and polemicists all became accessible.

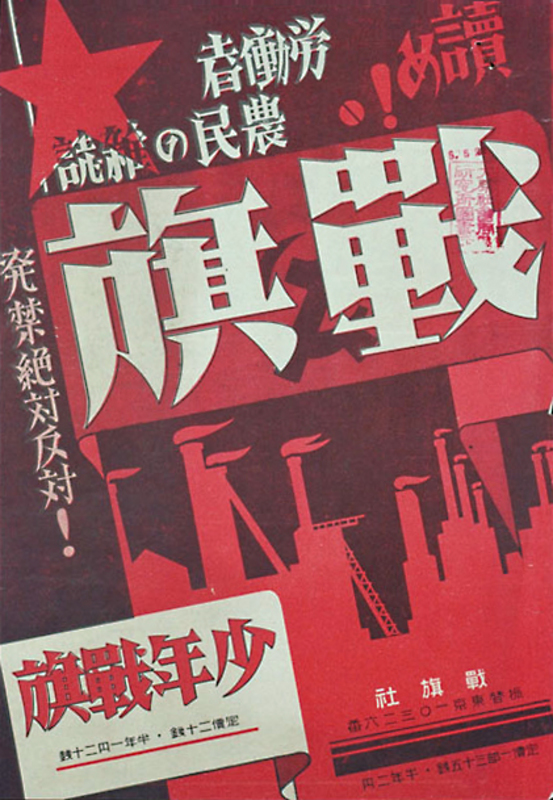

For the usual reasons, most periodicals associated with leftwing parties and unions were short-lived: government censorship and outright repression coupled with organizational infighting generally did them in. Nonetheless, some survived long enough to have an impact. Additionally, they were complemented and buttressed by another new genre of radical protest that emerged out of the social and economic turmoil of these years—namely, proletarian literature.

Proletarian literature made up almost half of the pages of the two largest magazines of the interwar period, Chūō Kōron (Central Review) and Kaizō (Reconstruction), while the two most successful leftist periodicals—Bungei Sensen (Literary Front) and Senki (Battleflag)—focused exclusively on proletarian literature and amassed a combined circulation of over 50,000 by 1930. Writers as diverse as Yumeno Kyūsaku, Umehara Hokumei, Hayashi Fumiko, and Ryūtanji Yū all published literary works that reflected concern for the “details of daily life under capitalism” and explored problems associated with industrialization, modernization, and urbanization.

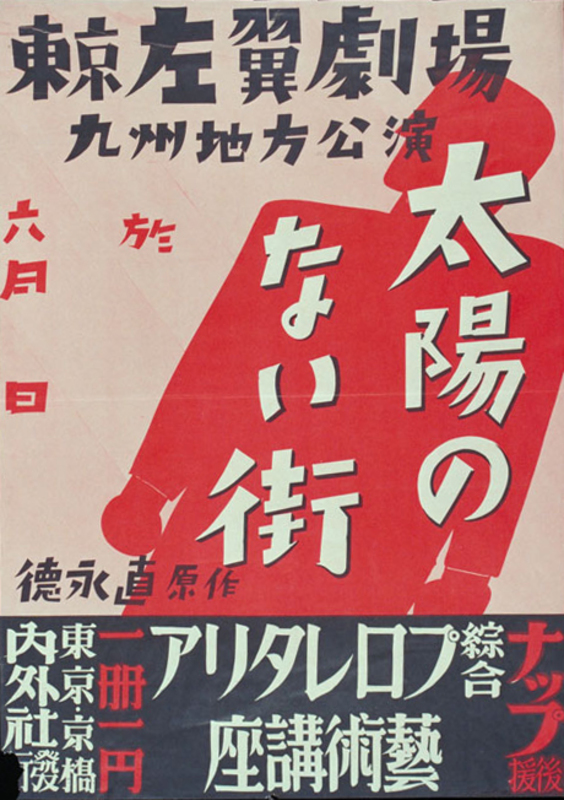

The consolidation of three affiliated organizations—the Japan Proletarian Artists Alliance (Nihon Proletaria Geijutsu Renmei), the Labor-Farmer Artists Alliance (Rōnō Geijutsuka Renmei), and the Vanguard Artists Union (Zenei Geijutsuka Dōmei)—into the All-Japan Proletarian Art Federation (Zen Nihon Musansha Geijutsu Renmei) in 1928 enhanced the publication success of the movement’s most famous writers, Kobayashi Takiji and Tokunaga Sunao. In 1928 and 1929, the new federation’s journal Senki serialized two of Kobayashi’s most famous works. The first, titled March 15, 1928 and published in the November and December issues of that year, dealt with police torture following a draconian roundup of socialists and communists by the Home Ministry’s Special Higher Police (Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu, commonly abbreviated as Tokkō and referred to as the thought police). In May and June of the following year, Senki published Kobayashi’s Crab-Cannery Ship (Kanikōsen), which focused on workers attempting to form a union in the fishing industry; this provocative novella was adapted as a theatrical performance that same year. In 1929, Senki also serialized Tokunaga’s most famous novel, Street Without Sun (Taiyō no nai Machi), which focused on workers struggling for their rights and was quickly adapted as a stage presentation.

Although Kobayashi himself escaped the notorious “March 15 Incident” he excoriated in his 1928 rendering, this was a great turning point for political activists. Faced with the prospect of imprisonment and torture, many leftists then or soon afterwards publicly announced the recantation (tenkō) of their beliefs—a largely collective act that has haunted the political left in Japan ever since. Tokunaga more or less recanted in 1933. Kobayashi did not, and in that same year, at the age of 29, he paid the price for commitment to his ideals. He was arrested for being affiliated with the outlawed Japan Communist Party and died after being tortured by the same “thought police” he had criticized five years earlier.

In perusing the Ohara collection of protest graphics, it is helpful to keep such intimate vignettes in mind. Political Theater

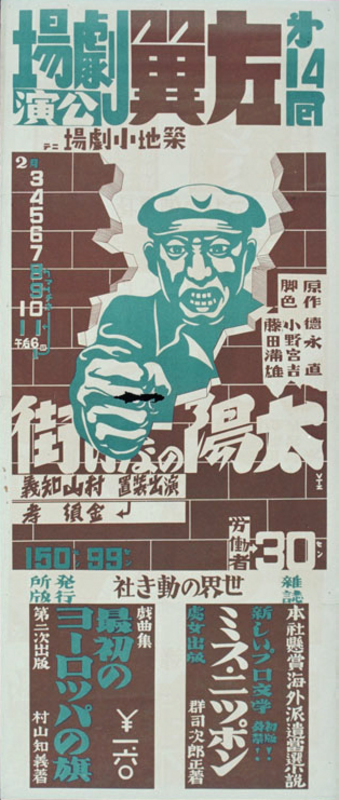

POLITICAL THEATER

The introduction of European-style theatrical modernism in Japan can be dated quite precisely to the immediate wake of the Russo-Japanese War in the early years of the 20th century. An Ibsen Society was founded in 1907, for example, and a 1911 production of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House galvanized formation of the Blue Stocking Society (Seitō), a pioneer voice in the Japanese woman’s movement, that same year.

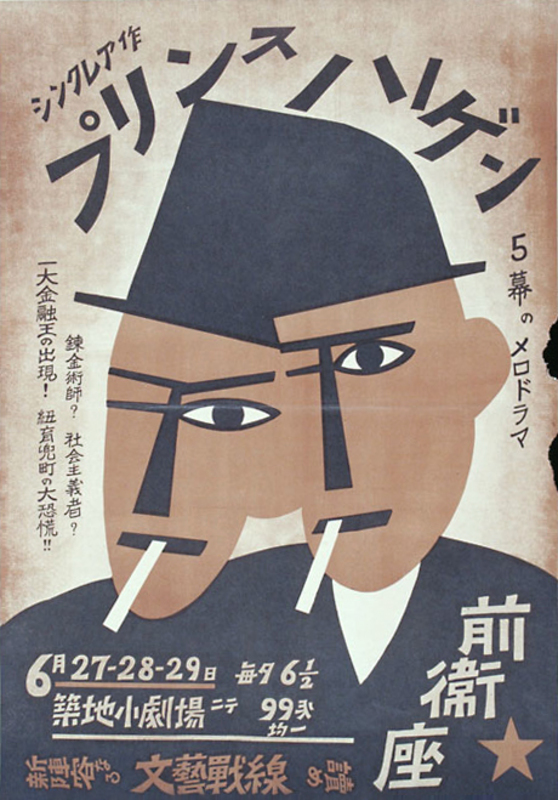

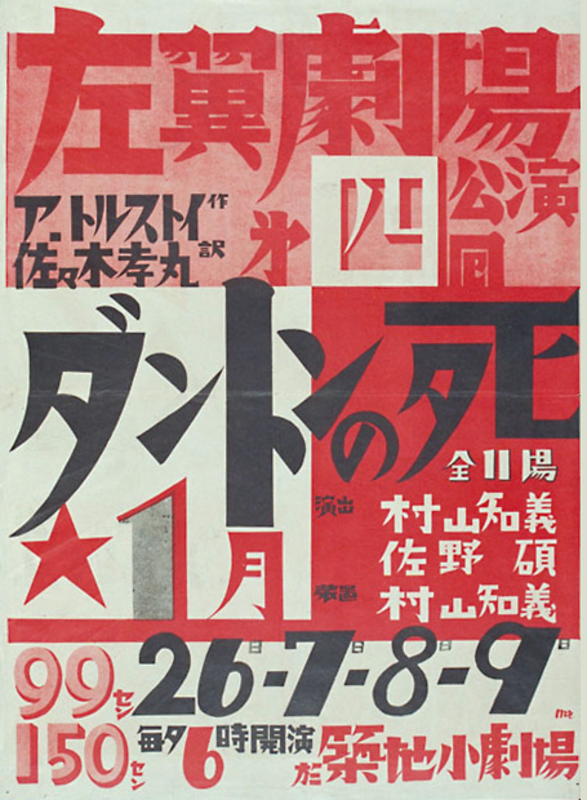

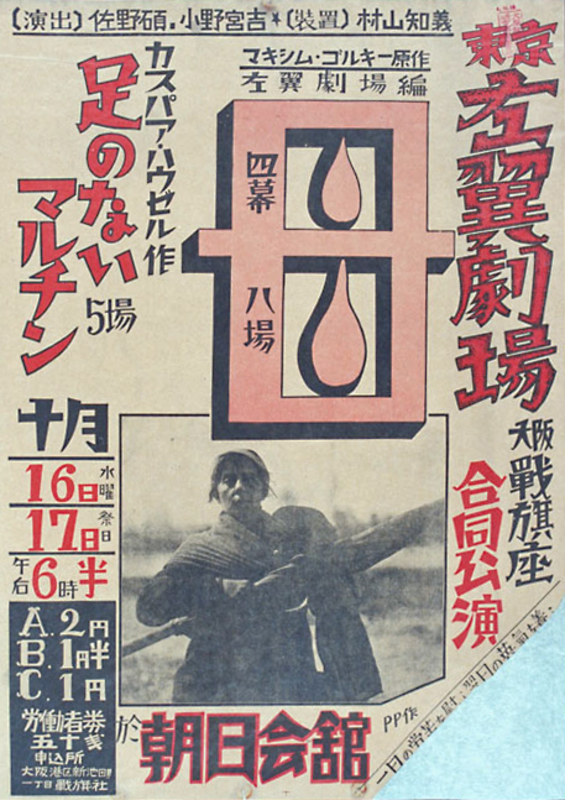

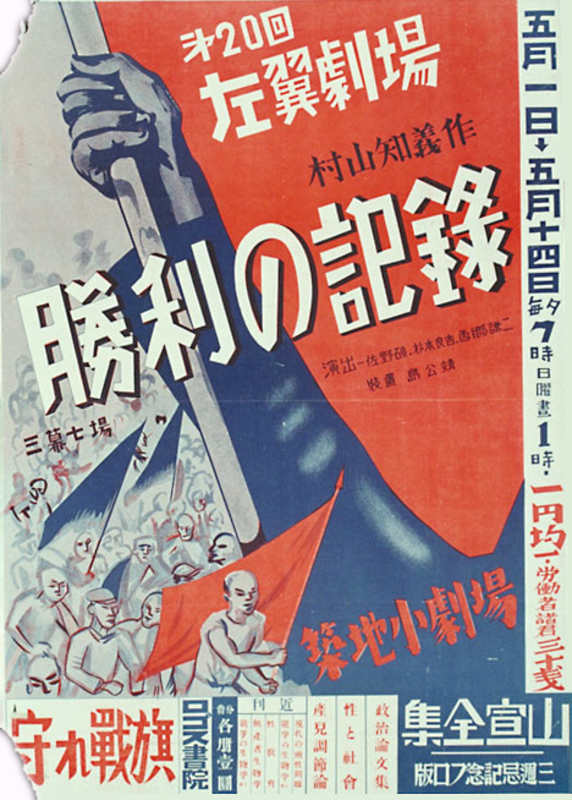

The modern theater movement took the generic name Shingeki (New Theater), and the infusion of Western influences increased exponentially following World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution. Expressionism, dadaism, and constructivism all impacted the Japanese theater world. So also, predictably, did proletarian literature and stagecraft. In 1924, the year following the Kanto earthquake, the Tsukiji Little Theater (Tsukiji Shōgekijō) was founded in Tokyo with an original commitment to produce only plays by foreign authors. Their impressive offerings included works by Anton Chekhov, Maurice Maeterlinck, Maxim Gorky, Upton Sinclair, George Bernard Shaw, August Strindberg, Roman Rolland, and Luigi Pirandello.

Typically, factionalism coupled with mounting repression fractured the modern theater movement and culminated in its dissolution by the end of the 1930s. In 1928, the Tsukiji Little Theater split into “political” and “literary” factions, for example, and in 1940 government oppression culminated in a mass arrest of around 100 individuals associated with leftwing theater. As elsewhere on the left, many beleaguered theatrical activists ultimately recanted and redirected their activities to support of the “holy war.” At the same time, however, and also typically, this brief but intense interwar engagement in critically addressing contemporary problems had a profound influence on the reemergence of politically and socially concerned theater in the years following Japan’s defeat in 1945.

The prewar career of Murayama Tomoyoshi provides a vivid impression of the complex and interactive dynamics of the proletarian art, literature, and theater movements. A Christian convert who studied art and drama in Berlin in the early 1920s, Murayama quickly made a name for himself as a leader of the avant-garde MAVO art movement while also extending his vision and energy to theater writing, directing, set design, and even occasional acting. His theatrical productions included Marxist renditions of “Robin Hood” and Don Quixote. In 1929, he acted in the Tokyo stage production of Tokunaga’s proletarian novella Street Without Sun and also designed the set for a Japanese adaptation of Danton’s Death, a 1835 play about the French Revolution by the precocious German playwright Georg Buchner. (Buchner was only 23 when he died of typhus in 1837.)

Murayama was arrested in May 1930 and charged with violating the Peace Preservation Law. Released in December, he immediately and provocatively joined the outlawed Japan Communist Party, which led to his rearrest and imprisonment in 1932. He was released from prison in 1934 after ostensibly recanting his leftist positions, but continued to produce dramatic work critical of the militarist state—leading to interludes of incarceration in 1940-42 and again in 1944-45. Unlike his contemporary Kobayashi Takiji, the proletarian writer who died in the hands of the police after being arrested, Murayama survived the war to participate actively in the turbulent—and, again, fractious—postwar scene. He died in 1977, at the age of 76. The following theater posters from the Ohara collection all involve Murayama in one way or another.

This article was produced in collaboration with Visualizing Cultures. It is part of a two-part presentation by Christopher Gerteis; the second part may be found here.

Recommended Citation: Christopher Gerteis, “Political Protest in Interwar Japan Part I” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 37, No. 1, September 15, 2014.

Christopher Gerteis is Senior Lecturer in the History of Contemporary Japan at SOAS, University of London. He is author of Gender Struggles: Wage-earning Women and Male-Dominated Unions in Postwar Japan, (2009); co-editor of Japan since 1945: from Postwar to Post-Bubble, (2013); and editor of the ‘SOAS Studies in Modern and Contemporary Japan‘, a peer-reviewed scholarly monograph series published in association with Bloomsbury (here).

SOURCES & CREDITS

Basic References

Those who wish to enlarge their knowledge of subjects mentioned in this unit will find the following two reference sources especially useful:

(1) The database of the Ohara Institute for Social Research at Hosei University. In addition to thousands of posters and other graphics, extending into the early postwar years, this excellent website includes English captions as well as considerable English-language commentary.

(2) Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, 8 volumes plus a separate index volume (Kodansha, 1983). This is far and away the best single English-language encyclopedia on Japan, containing over 10,000 entries including long essays on major subjects. Kodansha published a compressed and lavishly illustrated two-volume version of this reference work in 1993 under the title Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia.

Sources

Beckmann, George and Okubo Genji, The Japanese Communist Party, 1922-1945(Stanford University Press, 1969).

Colegrove, Kenneth, “The Japanese General Election of 1928,” Foreign Affairs 22.2(May 1928).

Colegrove, Kenneth, “Labor Parties in Japan,” American Political Science Review 23.2(May 1929)

Duus, Peter and Irwin Scheiner, “Socialism, Liberalism, and Marxism, 1901-1931,” inPeter Duus, ed., Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 6: The Twentieth Century (University of Cambridge Press, 1988).

Garon, Sheldon, The State and Labor in Modern Japan (University of California Press,1987)

Garon, Sheldon, The Evolution of Civil Society from Meiji to Heisei (Westherhead Center for International Studies, Harvard University, 2002).

Gordon, Andrew, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (University ofCalifornia Press, 1991)

Gordon, Andrew, The Evolution of Labor Relations in Japan: Heavy Industry, 1853-1955 (Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1985).

Hane, Mikiso, Peasants, Rebels, and Outcastes: The Underside of Modern Japan(Pantheon Books, 1982).

Hane, Mikiso, Reflections on the Way to the Gallows: Rebel Women in Prewar Japan(University of California Press, 1988).

Havens, Thomas, “Japan’s Enigmatic Election of 1928,” Modern Asian Studies 11.4(October 1977).

Keene, Donald, “Proletarian Literature of the 1920s,” in his Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1984).

Keene, Donald, “Japanese Literature and Politics in the 1930s,” Journal of JapaneseStudies 2.2 (Summer 1976), pp. 225-48.

Kinzley, W. Dean, Industrial Harmony in Modern Japan: The Invention of a Tradition(Routledge, 1991).

Kobayashi Takiji, “The Factory Ship” and “The Absentee Landlord,” translated byFrank Motofuji (University of Washington Press, 1973).

Large, Stephen, The Yūaikai, 1912-1919: The Rise of Labor in Japan (MonumentaNipponica Monographs, 1972).

Large, Stephen, Organized Workers and Socialist Politics in Interwar Japan(Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Large, Stephen, ed., Shōwa Japan: Political, Economic and Social History, vol. 1(Routledge, 1998).

Mackie, Vera, Creating Socialist Women in Japan: Gender, Labour and Activism 1900-1937 (University of Cambridge Press, 1997).

Mackie, Vera, Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality(Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Scalapino, Robert, The Early Japanese Labor Movement: Labor and Politics in aDeveloping Society (University of California Press, 1984).

Shea, G. T., Leftwing Literature in Japan (University of Tokyo Press, 1964).

Steinhoff, Patricia, Tenko: Ideology and Social Integration in Prewar Japan (Garland,1991).

Totten, George. The Social Democratic Movement in Prewar Japan (Yale UniversityPress, 1966).

Totten, George, “Labor and Agrarian Disputes in Japan Following World War I,”Economic Development and Cultural Change 9.1, part 2 (1960), pp. 187-212.

Tsurumi, Kazuko, “Six Types of Change in Personality: Case Studies of IdeologicalConversion in the 1930s,” in her Social Change and the Individual (Princeton University Press, 1966).

Waswo, Ann, “The Origins of Tenant Unrest,” in B. Silberman and H. D. Harootubnian,Japan in Crisis (Princeton University Press, 1974).

CREDITS

“Political Protest in Interwar Japan l” was developed byVisualizing Cultures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technologyand presented on MIT OpenCourseWare.

MIT Visualizing Cultures:John W. DowerProject Director Emeritus Professor of History

Shigeru MiyagawaProject Director Professor of LinguisticsKochi Prefecture-John Manjiro Professor of Japanese Language and Culture

Ellen SebringCreative Director

Scott ShunkProgram Director

Andrew BursteinMedia Designer

In collaboration with:Christopher Gerteis Author, essayLecturer in the History of Contemporary Japan School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

Floris van Swet Research and translation, essay