Obama’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ in response to the resurgence of Chinese power has undergone significant developments since it was first announced in November 2011. Not least has been the emergence of Australia as a central part of Washington’s plans to strengthen American influence and military reach across the Asia-Pacific. While elite and popular support for the US alliance in Australia persists, public opinion polls indicate possible cleavages for challenging the status quo.

Developments in Obama’s ‘Pivot to Asia’

Addressing the Australian Parliament in Canberra on 17 November 2011, President Obama officially announced that after a decade of costly war in the Middle East the US was now turning its attention to the Asia-Pacific.2 A month prior to Obama’s address, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton dubbed the new focus a ‘pivot’ in an article for Foreign Policy,3 the term since persisting despite the best efforts of the Obama administration to replace it with the more innocuous term ‘rebalance’.

The central military components of the Pivot include a shift in US military assets to the region, the extension of US defence ties, an increase in US defence exports and foreign military training programs, more frequent US warship visits and the expansion of joint military exercises.4

Although the Pivot constitutes ‘a comprehensive plan to step up US engagement, influence and impact on economic, diplomatic, ideological and strategic affairs in the region’,5 it remains to be seen whether the Obama administration has the strategic vision or the resources to sustain the Pivot in the long-term. Recent events in the Middle East and Ukraine continue to preoccupy US planners and a number of observers have questioned the viability of the Pivot in an era of fiscal constraint.6

|

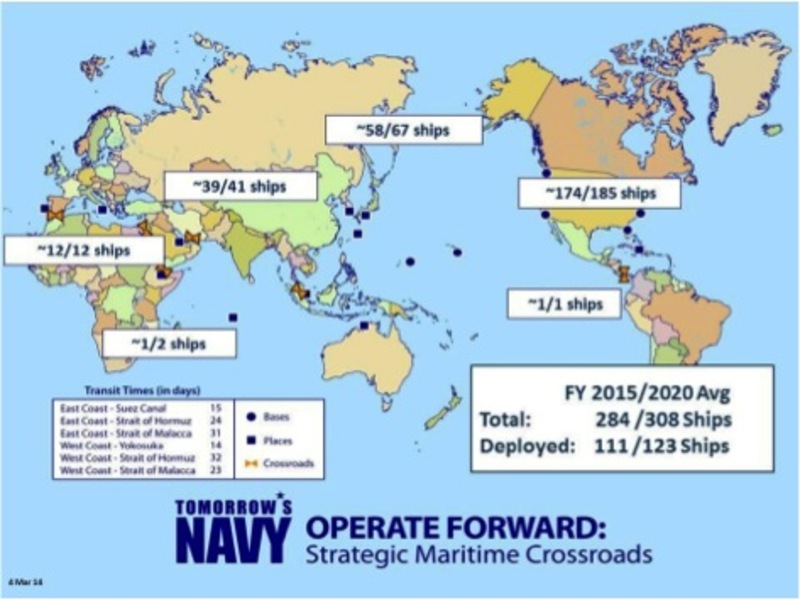

US Navy’s projected force in FY2015 and FY2020. Source: Admiral Jonathan Greenert, 2014 Report to the Senate Armed Services Committee |

At the centre of the Pivot is the decision to increase the presence of the US Navy’s fleet in the Asia-Pacific from 50 to 60 per cent by 2020. Today, 104 of the US Navy’s 290 ships are deployed around the world, 50 of them in the Asia-Pacific. The Pivot will see the number of ships deployed in the region in 2020 increase to approximately 67, notably including a majority of US aircraft carriers, but also its cruisers, destroyers, submarines and Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs) designed specifically for operations close to shore.7 Plans to forward station up to four LCSs in Singapore on rotation in 2017 were announced in June 2012. The first LCS was deployed to Singapore’s Changi naval base for 10 months in 2013 and the second will deploy for 16 months later this year.

The Pivot includes plans to forward-deploy a United States Marine Air‐Ground Task Force (MAGTF) in Darwin. Beginning in April 2012 with 200 Marines, the US Marine Rotational Force – Darwin (MRTF-D) is being implemented in four incremental phases until fully deployed in 2016. As of March 2014 1150 Marines, or a battalion-sized unit, had been deployed. The full MAGTF is to consist of 2,500 Marines including command, ground combat and air combat elements available for rapid deployment for expeditionary combat.

The preliminary estimated cost of the MAGTF is $1.6 billion.8 A recent defence agreement struck between Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott and US President Obama is reported to see Australia pay for most of the cost of the Marine rotations through Darwin and paves the way for the arrival of more US military assets.9

Like the US Navy, the US Air Force has announced plans to allocate 60 per cent of its overseas based forces to the Asia-Pacific region including those in the cyber and space domains. In June 2013, US Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel announced that:

In addition to our decision to forward base 60 per cent of our naval assets in the Pacific by 2020, the US Air Force has allocated 60 per cent of its overseas-based forces to the Asia-Pacific – including tactical aircraft and bomber forces from the continental United States. The Air Force is focusing a similar percentage of its space and cyber capabilities on the region. 10

A month later, Chief of US Air Force Operations in the Pacific, General Herbert ‘Hawk’ Carlisle, revealed that along with the announced 2,500 Marines to be deployed to Australia by 2016, the US Air Force would dispatch ‘fighters, tankers, and at some point in the future, maybe bombers on a rotational basis’. US jets are also to be sent to Changi East air base in Singapore, Korat air base in Thailand, Trivandrum in India, and possibly bases at Kubi Point and Puerto Princesa in the Philippines and airfields in Indonesia and Malaysia.11

During Obama’s four-country Asian tour in April 2014, a 10 year ‘pact’ with the Philippines was signed providing for the rotation of an unspecified number of US forces at selected military camps and the prepositioning of US fighter jets and ships. The deal, coming in the wake of Philippines-China clashes over the Scarborough Shoals and sparking anti-US protests, represents ‘the most significant defence agreement signed with the Philippines in decades’, according to the US National Security Council’s senior director for Asian affairs. As part of the agreement, US forces may return to the Subic Bay naval base where they were forced to leave in 1992, ending a vast American military presence that began with the capture of the Islands from Spain in 1898.12

|

Geographical location of Jeju Island, South Korea. Source: Bruce gagnon, Global research.ca |

The Pivot is being undertaken amidst the establishment and upgrade of major bases in the region. Of particular significance is the new naval base being built on Jeju Island in South Korea, less than 500 kilometres from the Chinese mainland, with the anticipation that it will be utilised for both South Korean and American naval forces. It will host up to 20 warships, including three Aegis destroyers and an aircraft carrier, and will provide a long-range ballistic missile capability for targeting southeast China.13

Meanwhile, the US strategic naval and marine base on the Pacific island of Guam is being upgraded. A new Marine Corps base is being established at an officially estimated cost of $US8.6 billion, although the final cost is likely to involve billions more, with Japan picking up a significant portion of the cost. 5,000 US Marines and their dependents will relocate to the new base from Okinawa.14

Obama’s Pivot to Asia is taking place in the context of increasing militarisation in the Asia-Pacific at a time when regional tensions have risen to levels unseen for decades.

Arms imports in East Asia surged nearly 25 per cent last year, from $9.8 billion in 2012 to $12.2 billion in 2013. Leading the way is China, having overtaken South Korea as the region’s largest arms importer despite its burgeoning domestic arms industry.15 Steadily increasing its military spending since the mid-1990s, China has recently clashed with a number of its neighbours including Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam, as well as with the pre-eminent power in the region, the United States.

Japan has also stepped up its military engagement in the region under the leadership of Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, sending patrol boats to Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia, significantly increasing its military spending, easing restrictions on arms exports, and deepening its strategic partnership with Australia, India and others. In the most dramatic policy shift away from its post-war pacifism, Abe successfully circumnavigated Japan’s constitutional ban on exercising ‘collective self-defence’, paving the way to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with its principal ally, the United States.16

Official pretexts and imaginary threats

Officially, the Pivot is about countering threats to security and stability in the Asia-Pacific. According to former US defence secretary Leon Panetta, the Pivot is about dealing with the challenges of ‘humanitarian assistance’, ‘weapons of mass destruction’, ‘narco-trafficking’ and ‘piracy’. Such claims, however, do not stand up to basic scrutiny. As the director of foreign policy studies at the right-wing CATO institute, Justin Logan, points out:

Dealing with humanitarian assistance and needs, stifling nuclear proliferation, suppressing narco-traffickers, and dispatching pirates do not require more than half the US Navy. If China made this sort of argument to defend deploying more than half its naval assets to the Western hemisphere, American leaders would not give the argument a moment’s consideration.17

Australian officials also stress that a key focus of the US military build-up is to have the necessary resources ready to provide humanitarian aid for natural disasters. Yet as The Australian’s defence editor wryly notes, ‘it is not clear what roles aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered submarines would play in humanitarian missions’, the deployment of which has been canvassed by top US defence officials.19

|

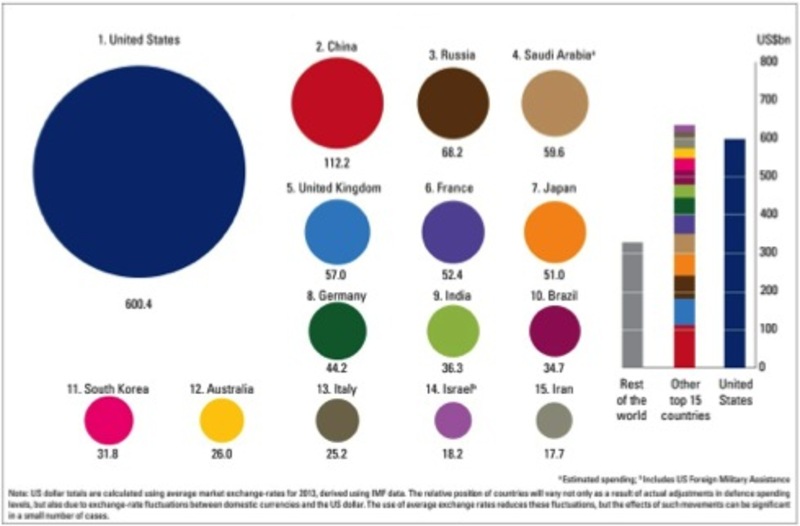

Top 15 Defence Budgets 2013 $USbn. Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies |

The most important, albeit officially unacknowledged, justification for the Pivot is to hedge against a potentially hostile and rising China. Although signifying a significant regional shift in geopolitical power, the rise of China poses little threat to US national security. This fundamental strategic reality is underpinned by the vast military gap between China and the US. In 2013, the US officially spent $600 billion on defence, almost as much as the next 14 countries combined and over five times as much as China.20 Moreover, US strength is complemented by allies who surround China—Japan, South Korea and Taiwan—and a global network of military bases.

A crucial part of the military gap is America’s far superior nuclear war-fighting capacity. A report coproduced by the Federation of American Scientists concludes:

Our principal finding is that the Chinese-US nuclear relationship is dramatically disproportionate in favour of the United States and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Although the United States has maintained extensive nuclear strike plans against Chinese targets for more than half a century, China has never responded by building large nuclear forces of its own and is unlikely to do so in the future. As a result, Chinese nuclear weapons are quantitatively and qualitatively much inferior to their US counterparts.21

While China is currently modernising its nuclear forces, the US spends more on its nuclear arsenal than the rest of the world combined and, according to one recent conservative estimate, is on course to spend approximately US$1 trillion over the next 30 years maintaining its existing nuclear arsenal and procuring a new generation of nuclear weapons and delivery systems.22

It is also pertinent that China requires substantial military resources to be employed for internal security and to protect against bordering rival powers. The US, on the other hand, with weak neighbours and vast ocean barriers, is able to focus outwards, possessing and exercising overwhelming force projection capabilities. America maintains over 1000 foreign military facilities (China has none), has elite forces deployed to 134 countries, and annually conducts 170 military exercises and 250 port visits in the Asia-Pacific region alone.23

|

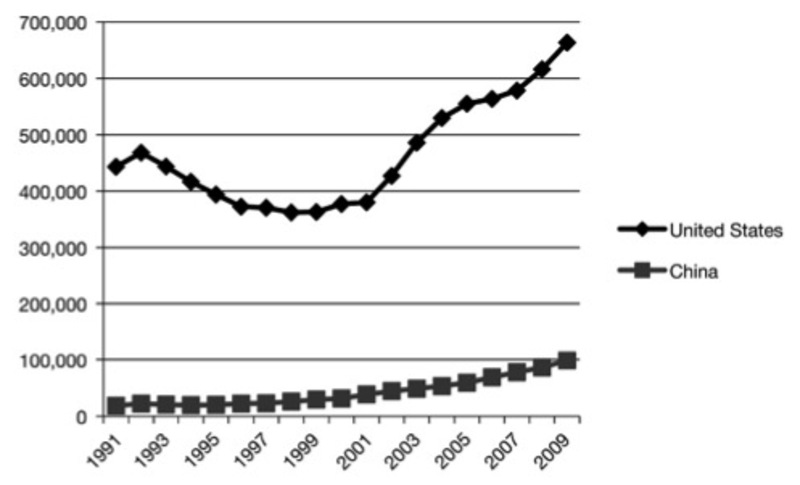

US and China military spending, 1998-2009 (current $, millions). Source: Michael Beckley (2001/12), ‘China’s Century?’ p. 74. |

The fact that China’s GDP is on track to overtake the US in the next few decades is frequently offered as evidence of American decline. Yet the geopolitical implications of China’s growing economic power should not be exaggerated. Even if China were to surmount the serious economic, demographic, environmental, political and international challenges it now faces and continue high-speed growth, economic size does not inevitably correlate with military or geopolitical power.

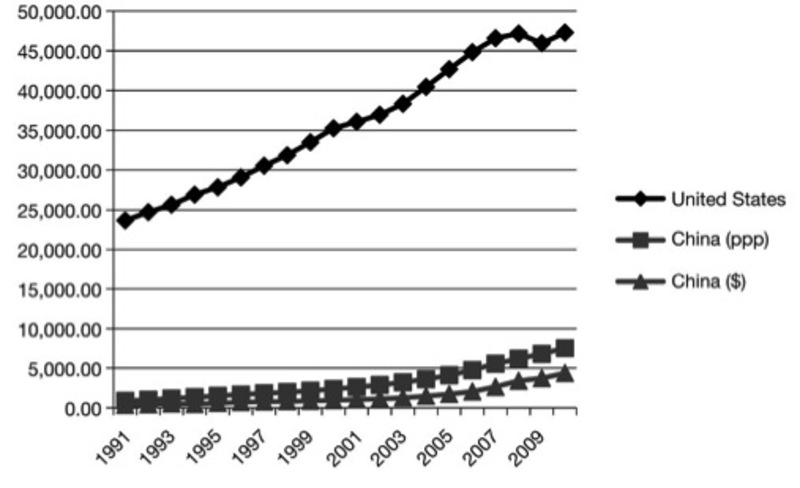

As international security expert Michael Beckley points out, it is not the absolute size but the superior level of economic development and ‘surplus wealth’, reflected in wealth per capita, that is most significant for assessing national power.24 By this and other measures, despite China’s spectacular growth, the US has actually increased its lead over China in the last two decades by amounts that exceed China’s total capabilities. As the data show:

From 1991 to 2010, the gap in defence spending (excluding US spending in Iraq and Afghanistan) increased by $147 billion, which is $26 billion more than China’s entire 2010 military budget; the gap in per capita incomes in real terms widened by $19,000, which is 4.5 times the average Chinese income; the gap in high-technology output grew by $2.8 trillion, roughly double China’s total high-tech output; and the gap in gross domestic product in real terms expanded by $3.1 trillion, equivalent to half of China’s total GDP.25

Of course economic trends can change. Yet the most significant factor in future economic growth is innovation or intellectual power and, on this count, the US far outstrips China, including the quality (not quantity) of scientists and engineers, the number of leading universities, corporate investment in R&D and patents in new and emerging technologies.26 It is worth noting, too, that prior to the global financial crisis that began in 2007, ‘China was still catching up technologically to Korea and Taiwan, let alone the US’.27

What state-centric perspectives mistake for the global shift in power to China derived from the rapid growth of the Chinese national economy must be understood in no small part as a transnational phenomenon reflecting the rising power of the multinational corporation (MNC) in a global system in which American firms retain predominance.

China’s deepening integration into this US-led global economy is reflected in the massive inflows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) – growing from $1 billion to $72 billion annually between 1985 and 2005 or more than $600 billion in total – and its place as the preferred destination for outsourcing and contracting by MNCs. Indeed, much of the wealth generated by China’s productive capacity is captured by foreign corporations. For example, about two-thirds of China’s growth in exports between 1994 and mid-2003 is attributable to Chinese subsidiaries of MNCs or joint ventures with businesses from the industrialised world.28

|

US and China per capita income, 1991-2010 ($ in current prices). Source: Michael Beckley (2011/12), ‘China’s Century?’, p. 59. |

Integrated into global production networks, the Chinese export economy effectively serves as East Asia’s workshop where capital goods and components, predominantly from the US, Japan, and South Korea, are sent for final assembly and export, often after a process of sub-assembly in Southeast Asia. By penetrating and dominating China’s advanced industrial sectors and maintaining control over technology, services, branding and marketing, US, Japanese and European MNCs realise most of the value-added in the process.

Even as America’s manufacturing base has moved abroad and China has grown spectacularly to emerge as a manufacturing powerhouse, whose cities, highways, and railroads have all grown explosively, the US continues to dominate the strategic sectors of the global economy such that, as of 2007:

the top three or four global firms in such diverse sectors as technological hardware and equipment, software and computers, aerospace/military, and oil equipment and services were American, as were fourteen of the sixteen top global firms in healthcare equipment and services. In global media, four of the top five corporations were American, as were two of the top three in each of the pharmaceuticals, industrial transportation, industrial equipment, and fixed-line telecommunications sectors. And five of the top six corporations in the general retail sector were American… To top it all off, nine of the top ten corporations in global financial services were American…29

American dominance versus Chinese survival

The China threat thesis obscures ‘the dirty little secret of US defence politics [which] is that the United States is safe – probably the most secure great power in modern history.’30 Beijing, on the other hand, has a serious weakness along its maritime approaches. ‘Chinese strategists are acutely aware’, writes Brigadier General John Frewen of the Australian Army, ‘that they could do little in response if the United States chose tomorrow to constrict China’s maritime access to oil, minerals, and markets.’31

As China’s economy has grown over recent decades it has begun to attempt to redress its historic vulnerability to military intervention from the sea by developing a high-tech ‘Anti Access-Area Denial’ (A2/AD) capacity – or ‘counter-intervention’ as Chinese strategists prefer to call it – in order to keep the military forces of the United States and other potentially hostile powers at bay.

|

Shipping routes to China that would be subject to a US-led blockade as part of AirSea Battle. Source: Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA). |

In response, America’s new military strategy developed to accompany the Pivot to Asia – dubbed ‘AirSea Battle’ – is designed to prevent China from developing the capacity to defend itself against an attack from its air and maritime approaches. The strategy ‘relies on credibly threatening to strike critical military targets deep within Chinese territory from afar and on defeating PLA [People’s Liberation Army] air and sea forces in a sustained conventional campaign’. It also proposes the US and its allies, particularly Japan and Australia, ‘impose a distant blockade on China in the event of war.’32

Washington’s objective is to maintain its sphere of influence in the West Pacific, while for Beijing, continued US dominance ‘presents an existential threat’. Ultimately, writes Justin Kelly in the Australian Army Journal, ‘China is playing for higher stakes’.33

Evidence that the Pentagon is taking the potential ‘threat’ from China seriously can be found in both the 2014 Quadrennial Defence Review (QDR), which expressed deep concern about China’s rising A2/AD capability, and the FY2015 budget, where significant additional funds have been requested for countering such capabilities.34

Incidentally, in certain ways, China’s defence strategy mimics Australia’s own. The latest Defence White Paper (2013) reiterates this long-held defence priority for Australia: ‘Controlling the sea and air approaches to our continent is the key to defending Australia, in order to deny them to an adversary and provide the maximum freedom of action for our forces.’35 Recognising the similarities, Andrew Davies and Mark Thompson of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute write that China’s strategy to protect its air and maritime approaches is ‘as fundamental to China’s self-defence as it is to ours…’. ‘In contrast’, they add, ‘US interests in the region are neither immutable nor fundamental to US security.’36

‘Internationalising’ the East and South China Sea disputes

Granted that US hegemony rather than US security is at stake, Obama’s Pivot to Asia may still arguably be justified as necessary to resolve the ongoing disputes in the East and South China Seas where Beijing is depicted as the principal antagonist requiring a US response to restore balance and stability. The reality is more complex, and American claims are unpersuasive.

Since 2010, territorial disputes in the South China Sea have seen increased tensions between China and its Southeast Asian neighbours. Nationalism, potentially vast oil and gas resources and fish stocks, the strategic importance of major sea lines of communication, and the territorial implications of the 1982 UNCLOS agreement combine to drive the disagreements.

China’s military assertiveness is particularly worrisome for the prospects of a just and peaceful resolution to the conflicts in the East China and South China Seas. There are, however, no innocent parties in the disputes. All claimant states in the multiple disputes (China, Japan, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines and Brunei) have been provocative at one time or another while territorial claims by the Philippines (pre-2009) and Malaysia are as spurious and weak as China’s.37

The common refrain is that US military domination over these waters is necessary to maintain peace, uphold international law and protect freedom of navigation in the event that a hostile China disrupts or blocks regional and international trade.38 The unstated flipside of this equation is that America’s foot remains on China’s throat, able at any time to choke off the resources and products necessary for Chinese industry and ultimately the PRC’s (People’s Republic of China) survival. Although there is a mutually beneficial economic relationship between the two countries, should conflict develop US war plans involve contingencies for blockading China.

It is highly unlikely that in the absence of US protection China would attempt to shut down the free flow of trade in the South China Sea, an act that would irreparably damage Beijing’s interests. It is military, not commercial freedom, that’s at stake. As Ralf Emmers explains:

…in the context of the South China Sea the freedom of navigation principle is mostly associated with the freedoms of navigation and flight of military ships and aircraft, as no restriction to commercial shipping is feared in the disputed waters. Due to its economic interests the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is not expected to interrupt the shipping lanes that cross the South China Sea.39

In other words, as former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans makes clear, America’s primary motivation is not to protect freedom of navigation which it regularly ‘talks up’, but rather ‘its overwhelming preoccupation… with the right to engage in military surveillance unhindered, as close inshore as it can’ to China.40 It is this ‘overwhelming preoccupation’ that has led to a number of clashes between the US and Chinese aircraft and naval vessels in the South China Sea since 2001.41

According to South China Sea specialist Leszek Buszynski, if the disputes between China and its neighbours were simply about competing claims to energy resources and fisheries, a peaceful resolution that satisfied all of the parties might have been possible. However, in the context of strategic rivalry with the United States, the prospect of a more conciliatory China is now far less likely. China’s desire to counter US regional dominance and US insistence on retaining that dominance has transformed the disputes in the South China Sea into a competition between major powers.42

Much the same is true in the East China Sea where China and Japan are embroiled in territorial disputes over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands.

|

China, Korea and Western Pacific EEZs. Source: The Asia Pacific Journal |

As in the South China Sea, nationalism and energy reserves are powerful factors in the disputes, as are wider strategic concerns. Gavan McCormack has pointed out that the core territorial issue is a product of the inequities inherent in UNCLOS.43 Responsible for apportioning much of the ‘high seas’ in the form of EEZs, UNCLOS especially privileged the former European and American colonial powers who possess far flung islands, as well as Japan, with control over vast sea areas leaving China a minor player in its claims on the world’s oceans. Although its coastline is slightly longer than Japan’s, China’s maritime reach, as determined by its EEZ, is less than one fifth the size of Japan’s.

Thus, from the Chinese point of view, the appropriation of much of the maritime space across the Pacific from hostile or potentially hostile forces threatens its access to the Pacific. As Japan attempts to extend its already generous maritime claims, especially given its position as a client state of the US, Beijing’s claims to the Senkaku/Diaoyu take on exceptional importance.

While the US insists that it takes no position on who has rightful sovereignty over the islands, it has repeatedly declared its commitment to enforce Japan’s claims to possession in the event of a Chinese military challenge. In his most recent tour of Asia in April 2014, President Obama became the first sitting US president to declare the islands to be part of the defence alliance between Washington and Tokyo.44

Keeping Asia divided and dependent

Although the rise of China has added new impetus to calls for the United States to sustain its military engagement in the region, US regional hegemony has long been justified as necessary to keep the peace in Asia. The conventional wisdom amongst strategic studies experts is that US geopolitical primacy serves to maintain the ‘balance’ in East Asia by capping Japanese militarism, balancing Chinese power and deterring North Korea. It’s a particular favourite in realist international relations and strategic studies accounts of Asia-Pacific regional affairs to equate stability and the ‘balance of power’ with the prevailing distribution of power or the status quo; an interpretation that conveniently translates into support for US hegemony.45

In reality, there are strategic reasons why US hegemony is incompatible with the emergence of a peaceful and stable Asia. As Mark Beeson explains, American strategic involvement in the region ‘is expressly designed to keep East Asia divided and its security orientation firmly oriented towards Washington.’ Quoting international relations expert, Michal Mastanduno, Beeson elaborates on the reasons why keeping the region divided has been a key element of America’s overall grand strategy:

since the United States does not want to encourage a balancing coalition against its dominant position, it is not clear that it has a strategic interest in the full resolution of differences between, say, Japan and China or Russia and China. Some level of tension among these states reinforces their individual need for a special relationship with the United States’.46

America’s asymmetric, bi-lateral hub-and-spokes system of alliances in Asia was established precisely to prevent regional integration and independence. This geostrategy was perhaps best summed up by former US national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski who articulated it as the need ‘to prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and to keep the barbarians from coming together.’47

Obama’s Pivot to Asia extends this strategy. By reasserting its military presence and strengthening its alliance relationships in Asia, the US aims to not only to constrain the rise of China but also thwart any accommodation with Beijing that could lead to the emergence of a regional grouping independent of US leadership.48

A most special relationship for the 21st century

|

US President Obama addresses the Australian Parliament in Canberra, Australia, 17 November 2011. Source: The Washington Post. |

Speaking on Australian soil to Parliament House, Obama’s official announcement of the Pivot to Asia was widely considered to be confirmation of an Australian commitment to firmly attach itself to America’s quest to contain China’s rise.

Andrew Davies and Benjamin Schreer from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a government-funded security think-tank with close ties to defence policy makers, wrote at the time that ‘the presence of US forces is about much more than just their physical presence. It is about declaring our strategic intent in the burgeoning Sino-US competition in the Asia-Pacific.’49 Then Australian Defence Minister Stephen Smith proclaimed that Australia had become a geopolitical anchor for US defence policy in the Asia-Pacific and the ‘southern-tier’ of US strategy in the region.50

In truth, Australia’s commitment to participate in supporting US regional strategic objectives had already been affirmed one year earlier on the 25th anniversary of the Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) in November 2010. The US and Australia then announced a major expansion of military cooperation including more military exercises, more visits by American ships and aircraft, greater US access to Australian defence facilities and the pre-positioning of combat equipment and supplies.51

Crucially, it was also announced that Australia was extending its participation in the US global Space Surveillance Network by agreeing to station a powerful space surveillance sensor in Western Australia. Apart from detecting space debris, the network’s most important function is for US offensive and defensive space combat. The announcement was a clear indication of Australia’s support for America’s quest for military dominance in space.52

Since AUSMIN 2010 and Obama’s announcement of US troop deployments to Darwin in 2011, a number of developments demonstrated Australia’s increasingly important role in America’s strategy for projecting power and maintaining regional hegemony.

|

A typical Amphibious Readiness Group (ARG) of the sought the US plans to station near Australia. Source: The Australian. |

In August 2012, a report commissioned by the US Department of Defence (DOD) to review the current US military force posture and deployment plans explored the possibility of basing a US Carrier Strike Group (CSG) to HMAS Stirling in Perth and Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft in the Cocos Islands.53 Although then Defence Minister Stephen Smith denied there were any plans for home-porting US forces in Perth, the proposal represented a ‘change in gear’ in the Washington policy debate about deployments to Australia.54 Smith later confirmed that a jointly run military air base on the Cocos Islands, including for unmanned drone flights, was a long-term option under discussion,55 a plan also endorsed by the then Liberal Party opposition.56

In a move to deepen the strategic dimension of the MAGTF in Darwin, the US revealed plans in August 2013 to establish a fifth new Amphibious Readiness Group (ARG) in the Pacific by 2018. While unlikely to be based in Darwin, the new naval group would probably be forward stationed there in order to provide the US MAGTF with ‘amphibious lift’ or the capacity to rapidly deploy and project power around the maritime crossroads of the Malacca Straits, Southeast Asia and the eastern Indian Ocean. The US may deploy LCSs as part of the ARG.57

A major insight into how the US envisioned the future of the Australia-US alliance was provided in November 2013 with the publication of Gateway to the Indo-Pacific: Australian Defence Strategy and the Future of the Australia-US Alliance, prepared by a US think-tank and provided to US national security officials to inform and debate how best to carry out America’s Pivot to the region.58

Much of the report is dedicated to gauging Australia’s capacity to assist the US in a war with China and the capabilities and upgrades required to meet this demand. Australian air and naval bases, beyond Chinese missile range, are identified as geographic ‘sweet spots’ ideal for basing US forces. Recognising the recent shift in global power to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ region, the report identifies Australia as having ‘moved from “down under” to “top centre” in terms of geopolitical import.’ Like the UK during the 20th century, ‘America’s strong ties with Australia provide it with the means to preserve US influence and military reach across the Indo-Pacific’. In short, Australia is ‘increasingly viewed by policy-makers in Washington as a vital “bridging power” power in Asia’. Perhaps indulging in hyperbole, the report predicts, ‘the US Australia relationship may well prove to be the most special relationship of the 21st century.’59

Places are bases

Australian and US government officials continue to insist that the 2,500-strong MAGTF in Darwin is not a new US basing arrangement but rather a ‘rotation’ of forces consistent with the Pentagon’s strategy of seeking ‘places not bases’. However, the difference between rotational and non-rotational forces is in the eye of the beholder. As US Admiral Jonathan Greenert, US Navy Chief of Operations, explains:

Rotational forces deploy to overseas theatres from homeports in the United States for finite periods, while non-rotational forces are sustained in theatre continuously. Non-rotational forces can be forward based, as in Spain and Japan, where ships are permanently based overseas and their crews and their families reside in the host country. Forward stationed ships operate continuously from overseas ports but are manned by crews that deploy rotationally from the United States, as is the case with the LCS deployed to Singapore, with four ships in place by 2017. Forward operating ships, by contrast, operate continuously in forward theatres from multiple ports and are manned by civilian mariners and small detachments of military personnel who rotate on and off the ships.60

While logistical, financial and political factors distinguish these options, in practice, there is little strategic difference between permanently rotating forces and a traditional base. The Darwin MAGTF is just as much part of US force projection capabilities as are other foreign-based forces. As Admiral Samuel J. Locklear, Commander of US Pacific Command, explains:

USPACOM [US Pacific Command] joint forces are like an ‘arrow’. Our forward stationed and consistently rotational forces – the point of the ‘arrow’ – represent our credible deterrence and the ‘fight tonight’ force necessary for immediate crisis and contingency response. Follow-on-forces from the continental US required for sustained operations form the ‘shaft of the arrow’. Underpinning these forces are critical platform investments and the research and development needed to ensure our continued dominance.61

The utilisation of relatively smaller and more flexible ‘forward operating bases’ or ‘lily pads’—in conjunction with the global deployment of drones — is now the Pentagon’s preferred strategy for projecting power across the globe. The US Department of Defence January 2012 strategic guidance noted that the United States seeks to ‘develop innovative, low-cost and small-footprint approaches to achieve our security objectives, relying on exercises, rotational presence, and advisory capabilities.’62

According to the foremost independent expert on the lily-pad strategy, David Vine, Obama’s Asia Pivot ‘signals that East Asia will be at the centre of the explosion of lily-pad bases and related developments’. Vine provides insight into the breathtaking scope of this strategy to which Australia has acquiesced:

[US] military planners see a future of endless small-scale interventions in which a large, geographically dispersed collection of bases will always be primed for instant operational access… In other words, Pentagon officials dream of nearly limitless flexibility, the ability to react with remarkable rapidity to developments anywhere on Earth, and thus, something approaching total military control over the planet.63

|

Map of main Australia-US ‘joint facilities’ and ADF bases. Source: Richard Tanter (2012), ‘The “Joint Facilities” Revisited’, p.15. |

The MAGTF in Darwin is one addition to an existing network of US bases across Australia that have existed for decades. Although successive Australian governments have continually insisted that Australia hosts no US bases, only ‘joint-facilities’, the level of cooperation is in fact ‘fundamentally and inherently asymmetrical’, according to one of Australia’s foremost experts on the bases, Richard Tanter. While there are varying degrees of ‘jointness’ involved in the US military and intelligence presence across Australia, certainly the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap outside Alice Springs and the Naval Communication Station Harold E Holt (North West Cape) are primarily US bases with a limited Australian role.64

The significance of specific bases is perhaps less important than the overall increase in military and intelligence cooperation over the last decade, including the announcement of new ‘joint facilities’ or increased US access to existing facilities in Australia. Along with the deepening integration of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) with US armed forces and policy changes undertaken at the strategic level, the result, according to Tanter, ‘may well be, from a Chinese perspective, that Australia is not so much hosting US military bases, but is becoming a virtual American base in its own right.’65

Australia risks martyrdom

The disclosures by National Security Agency (NSA) whistle blower Edward Snowden cast new light on Australia’s deep integration with US global and regional military strategy. In addition to revelations about Australia’s vast intelligence gathering responsibilities to intercept phone calls and data across Asia as part of the US-led global spying network,66 also revealed was the extent of Australia’s direct participation in US global military operations through the Pine Gap defence facility, run by the NSA and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) along with the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD).

The facility has played a major role in illegal US drone strike assassinations in Afghanistan and Iraq by tracking the precise geo-location of suspects to be targeted and passing on that intelligence to the US military. The facility has become so important to the American military over the last ten years, and especially the last three years, that according to one Australian intelligence official the ‘US will never fight another war in the eastern hemisphere without the direct involvement of Pine Gap’.67

|

Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap. Source: Wikipedia |

The joint Australian-American facilities have long been integral to any potential American operations in the Asia-Pacific and have therefore presented themselves as targets to an adversary of the US for quite some time.68 Morever, as Davies and Schreer of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute make clear, an enhanced American naval presence in Australia as part of Obama’s Pivot strategy raises the distinct possibility of directly implicating Australia in a US blockade of China:

[US] Naval assets based in Australia, especially in the north of the continent, would be proximate to shipping lanes through the Indonesian archipelago and in the Southwest Pacific, which is particularly attractive should the US choose to impose a distant blockade against China in the Malacca or the Lombok straits…69

Gateway to the Indo-Pacific provides further details on how Australia might participate in a US-led blockade of China. In the event of a contest for control over the Indonesia straits, the report raises the possibility of the ADF exerting ‘chokepoint control’ by maintaining constant surveillance of aircraft and ships; intercepting Chinese surface ships and submarines threatening allied blockading efforts with the Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN) own submarines or long-range aircraft; escorting friendly ships through maritime chokepoints and, if Indonesia acquiesced, deploy ground forces equipped with anti-ship and anti-air missiles up and down the continental edges of the Indonesia archipelago to add mobile and rapidly deployable coastal firepower.70

In another scenario envisioned by the report, a ‘division of labour’ would exist between the US and Australia whereby US forces would deploy in the heart of the Western Pacific while Australia would ‘backfill US forces in the Southwest Pacific and coordinate a distant blockade in concert with regional allies and partners, using its air and naval forces to restrict commercial shipping bound for China’.71

If the likelihood of a major power conflict materialising presently seems small, it remains a distinct possibility, and the reality is that Canberra appears to be contemplating and even preparing for such a scenario. An allegedly secret chapter in the Rudd government’s 2009 defence white paper detailed plans to fight China by using the Australian Navy’s submarines to help blockade key trade routes, raising the prospect of China firing missiles at targets in Australia in retaliation.72

Even in the absence of a secret chapter, the 2009 white paper was extremely aggressive regarding the rise of China. While the language of the 2013 white paper was more conciliatory in tone and approach, numerous strategic commentators pointed out that very little had in fact changed in substance from the strategic assessment of the previous white paper, with China’s growing military power implicitly identified as a major concern.73

Unsurprisingly, both the 2009 white paper and the US troop deployment to Darwin evoked a furious response from China. Sending a message to Australia through the People’s Daily, China warned that the basing of US forces in Darwin was an ‘unfriendly move’ and that in any conflict between the two superpowers ‘Australia itself will be caught in the crossfire’.74 A scholar with China’s People’s Liberation Army also slammed Australia for being used as a ‘pawn’ by the US government to contain China.75 One of Australia’s most senior military officers had already warned that Australia runs the risk of ‘martyrdom’ in the event of a China-US conflict.76

Challenging the Australian-American alliance

In Australia the Pivot to Asia has evoked a number of critical responses from leading national figures. Most radical have been the proposals from former Australian Deputy Secretary in the Department of Defence, Hugh White, and former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. Over the past decade, White has repeatedly warned about the risks of continuing the regional status quo, arguing that it is in Australia’s best interests for the US to relinquish geopolitical primacy in the region and for Canberra to encourage Washington to do so.77

Fraser went further. He is the first current or former government leader to suggest Australia break its alliance with the United States. In a recently released book, Dangerous Allies, he urges Canberra to demand that the US MAGTF in Darwin leave within a year and the Pine Gap defence facility be closed down within four to five years amongst other measures designed to disentangle Australia from US strategic dependence.78

Despite the critiques of a few prominent figures, the political, media and academic elite has overwhelmingly supported increased Australia-US ties and either ignored or denounced any challenge to the status quo. Fraser’s proposal for ending the US alliance has provoked remarkably little attention79 while White’s thesis has been firmly rejected by Australia’s current political leaders,83 a number of key business leaders have publicly aired concerns with the growing US-Australia strategic relationship.

|

Obama speaking at a parliamentary dinner at Parliament House in Canberra. The Australian business community was notably absent. Source: Washington Post. |

Eccentric and blunt-talking Australian mining magnate, Clive Palmer, publicly condemned the decision to base US forces in Darwin as a ‘poke in the eye’ to China.84 More telling, the heads of mining giant BHP Billiton, the big four banks and the airlines all failed to attend President Obama’s 2011 parliamentary speech in Canberra and later a state dinner held in his honour. Their absence, reported the Australian Financial Review, ‘was a stark demonstration of where the priorities of Australian business leaders lie’, particularly when contrasted with a visit by the Chinese Vice-President the year before ‘who brought the business community out in force’. While most corporate heads justified their absence due to busy schedules, managing director of BC Iron, Mike Young, made explicit the reason why: ‘Corporate Australia recognises our economy is fundamentally tied to China, not America’.85

The split between the state and some parts of the corporate sector were made abundantly clear a year later when the soon to be head of the Australian Defence Department, Dennis Richardson, sternly rebuffed comments by two of Australia’s most powerful businessmen, Kerry Stokes and James Packer. The two billionaires with large Chinese business interests had each criticised the government’s China policy and security arrangements with the US. Stokes in particular, it was reported, ‘was physically repulsed by the presence of US troops on Australian soil not under Australian command’. Richardson bluntly accused the two businessmen of putting their commercial interests ahead of Australia as a whole.86

Although some parts of corporate Australia are clearly alarmed that the strategic relationship with the United States might place their business interests at risk, China’s economic leverage over Australia should not be exaggerated. While China is Australia’s largest two-way trading partner in goods and services, the economic relationship is rather one-dimensional. Exports to China consist mostly of commodities and imports of cheaply manufactured consumer goods. This fact, together with the dynamic nature of the international commodities market, means that China’s capacity to punish Australia economically is in practice ‘almost non-existent’.87 The economic relationship with the United States, on the other hand, is both strong and diverse. The United States remains Australia’s biggest two-way investment partner and third-ranked two-way trade partner, which includes sophisticated manufactures.

On a popular level, national surveys indicate strong and sustained support for the Australia-US alliance and presumably the various ‘joint-facilities’.88 Despite this support, there is good reason to question the common assumption that, in the words of former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, the Australia-US alliance is too ‘deeply ingrained in the minds and hearts of the Australian people’ to be challenged.90 It is also highly likely many Australians are ignorant of the fact that the treaty does not constitute a guarantee the US will come to Australia’s aid in the event of an attack but merely the obligation for each state to ‘consult’ and act ‘in accordance with its constitutional processes’.91

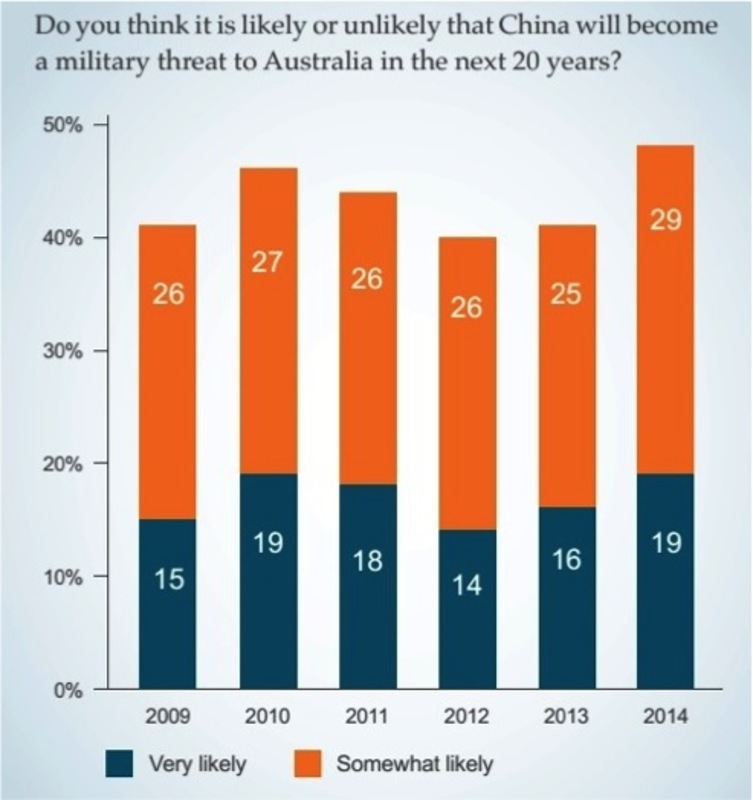

|

Australian perceptions of China as a military threat. Source: Lowy Institute Poll, 2014 |

Notwithstanding widespread ignorance about what is arguably the core of the Australia-US alliance, there is much room for interpretation in national surveys which ostensibly indicate strong support for it. Although Australian officials cite consistently high-levels of public support for the alliance, they invariably neglect to mention that the same surveys also frequently demonstrate that a majority of Australians desire a more independent foreign policy from the United States. Key foreign policy decisions made in accordance with Australia’s alliance obligations or to strengthen the alliance, as in recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the 2004 Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA), have all been deeply unpopular.

Despite its alliance obligations, 76 per cent of the public believe Australia should only support US military action if it is authorised by the UN and less than half (48 per cent) believe Australia should join the US in a new war in the Middle East. While the majority (61 per cent) of Australians are in favour of basing US forces in Australia,92 only 38 per cent believe Australia should support US military action in Asia in a conflict, for example, between China and Japan.93 Were the full implications of the bases widely understood, including the fact that they could implicate Australia in any US war with China, a considerable reduction in support is conceivable.

High-levels of popular support for the alliance – which is frequently characterised in polls as a ‘security’ or ‘defence’ relationship that helps ‘guarantee’ Australia’s security – likely derives in large part from the profound and persistent sense of national insecurity present in the public at large. Whether it be the rise of China, Indonesia or an irrational fear of being inundated by ‘boat people’, Australians as a whole remain insecure.

In reality Australia, along with New Zealand, faces ‘the least strategic challenge from the rise of China’ compared with any other East Asian country, according to Chinese defence and foreign policy specialist Robert S. Ross. Despite its military modernisation, ‘China’s naval surface fleet, including its aircraft carrier, cannot contend with many regional air forces… much less carry out advanced naval operations in Australian waters’. Moreover, ‘China’s most advanced aircraft and conventional missiles cannot reach Australia.’94

Australia’s most distinguished strategic and defence studies expert, Paul Dibb, broadly agrees with this assessment. Although a strong believer in the US alliance, Dibb has dismissed alarmist interpretations of China’s growing military power, describing the Chinese navy as a ‘paper tiger’ and warning Australians not to ‘frighten ourselves to death by drumming up the next military threat to Australia and basing our defence policy on the likelihood that we are going to be attacked by China’.95

Military capabilities aside, China has no conceivable interest in becoming embroiled in a military conflict with Australia. Lying far from its sea lines of communication, Australia is not strategically important to China. Thus, concludes former Australian ambassador James Ingram, ‘there is no reason why China would want to attack Australia unless it is allied with a United States itself in military conflict with China.’96

Despite this reality, 48 per cent of Australians in 2014 persisted in believing that China would likely become a military threat to Australia in the next 20 years.97 Australia as a whole also has an exaggerated view of China’s economic power and is one of very few countries in the Asia-Pacific where a majority believe that China will eventually replace the United States as the world’s leading superpower, with 67 per cent holding this view in 2013.98

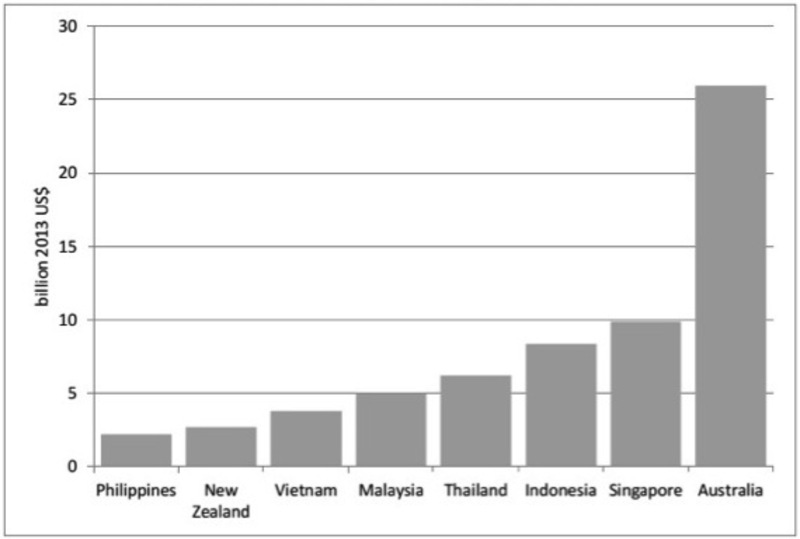

|

Defence Spending in Maritime Southeast Asia. Source: IISS, The Military Balance 2014 |

Similarly unfounded fears exist about the rise of Indonesia with 54 per cent of Australians concerned that it will emerge as a military threat.99 In reality, Australia’s defence spending is three times greater than Indonesia’s and the ADF now, and in the foreseeable future, is likely to retain its air and naval superiority over the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) which continues to lack significant power projection capabilities.100

There is clearly a gap between how the Australian public and officialdom envisage the alliance. As noted Australian strategic and defence studies expert Desmond Ball has pointed out, ‘there are significant differences between the positions articulated in official policy statements and public opinion’. In elite circles, ‘Since the 1980s, the important aspects of the alliance have been the preferential access to US defence technology… the intelligence cooperation and exchange arrangements; and the access to the most senior strategic councils in Washington’ derived from the hosting of important US bases or joint facilities. ‘On the other hand, the media and general public tend to view the importance of the alliance very much in traditional terms – that is, whether or not it provides a US security guarantee in the event of attack on Australia.’101

In other words, whereas the wider public conceive of the alliance as a means to secure Australia’s security, in elite circles it is primarily about securing Australia’s status as a ‘middle power’ and an ‘Asia-Pacific power’ by bolstering domestic defence and intelligence assets and providing access and influence over Washington.102

Ostensibly, this ‘force-multiplier’ effect of the alliance helps undergird Australia’s ability to independently defend itself. Yet security threats cannot constitute an adequate explanation for elite support of the alliance given that Australia has one of the most benign strategic environments in the world. ‘Since the 1970s’, Ball writes, ‘official assessments have reiterated that Australia faces no foreseeable threats, and threat scenarios have played no part in the development of Australia’s defence capabilities.’ Thus, Ball concludes, ‘the vitality of the alliance has been “threat insensitive”.’103

Australian’s security fears are a reflection of historically and culturally embedded fears of Asia and an accompanying belief that dependence on a ‘great and powerful friend’ is fundamental for the defence of the nation.104 Addressing these irrational fears which keep Australians dependent on the United States and bridging the divide between how the alliance is conceived of by the public and how it is interpreted and carried out by Australia’s political leaders is fundamental to challenging at a grassroots level Australia’s participation in the Pivot to Asia and the worst aspects that embody the Australia-US alliance more generally.

Vince Scappatura is researching Australia-US relations as a PhD candidate at Deakin University, Melbourne. He can be reached by email.

Recommended citation: Vince Scappatura, “The US ‘Pivot to Asia,’ the China Spectre and the Australian-American Alliance,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 36, No. 3, September 8, 2014.

Notes

1 The author gratefully acknowledges the many helpful comments and suggestions on draft versions of this article by Mark Selden. Of course, all errors are my own.

2 (2012), ‘Remarks by President Obama to the Australian Parliament’, Parliament House, Canberra, Australia, 17 November.

3 Hillary Clinton (2011), ‘America’s Pacific Century’, Foreign Policy, 11 October.

4 For the latest developments on the Pivot see S.D. Muni and Vivek Chadha, eds, Asian Strategic Review 2014: US Pivot and Asian Security, New Delhi: Pentagon Press.

5 Arvind Gupta (2014), ‘Forward’, in Muni and Chadha, eds, p. vii.

6 Zachary Keck (2014), ‘Can the US Afford the Asia Pivot?’, The Diplomat, 5 March.

7 (2014), Statement of Admiral Jonathan Greenert, US Navy Chief of Operations, 2014 Report to the Senate Armed Services Committee, 27 March, pp. 1-3, 20.

8 United States Senate (2013), ‘Inquiry Into US Costs and Allied Contributions to Support the US Military Presence Overseas’, Report of the Committee on Armed Services, 15 April, p. 58.

9 Wyatt Olson (2014), ‘Deal likely to bring more US military assets to Australia’, Stars and Stripes, 20 June 2014.

10 Chuck Hagel (2013), ‘The US Approach to Regional Security’, speech to the Shangri-La Dialogue, 1 June.

11 John Reed (2013), ‘US Deploying Jets Around Asia to Keep China Surrounded’, Foreign Policy, 29 July.

12 (2014), ‘US, Philippines Sign Military Deal to Counter Chinese Aggression’, The Australian, 28 April.

13 Andrew Yeo (2013), ‘A Base for (In)Security? The Jeju Naval Base and Competing Visions of Peace on the Korean Peninsula’, in Daniel Broudy, Peter Simpson and Makoto Arakaki, eds, Under Occupation: Resistance and Struggle in a Militarised Asia-Pacific, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 228.

14 Leevin T. Camacho (2013), ‘Poison In Our Waters: A Brief Overview of the Proposed Militarisation of Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands’, The Asia Pacific Journal, vol. 11, Issue 51, No. 1, 23 December.

15 Zachary Keck (2014), ‘East Asia Imports Surged by 25% in 2013’, The Diplomat, 21 March.

16 Linda Sieg and Kiyoshi Takenaka (2014), ‘Japan Takes Historic Step From Post-War Pacifism, Oks Fighting for Allies’, Reuters, 1 July.

17 Justin Logan (2013), ‘China, America and the Pivot to Asia’, CATO Institute, Policy Analysis No. 717, p. 10.

18 Brendan Nicholsan (2012), ‘US Seeks Deeper Military Ties’, 28 March The Australian.

19 Gordon Arthur (2012), ‘US Marine Deployment in Darwin – “Bordering on the Remarkable!”’, Asia Pacific Defence Reporter, 31 October

20 (2014), Chapter Two: Comparative Defence Statistics, The Military Balance, International Institute for Strategic Studies.

21 Hans M Kristensen, Robert S Norris, Matthew G McKinzie (2006), ‘Chinese Nuclear Forces and US Nuclear War Planning’, produced by the Federation of American Scientists and the Natural Resources Defence Council, November, p. 2.

22 Jon B Wolfsthal, Jeffrey Lewis, Marc Quint (2014), ‘The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad: US Strategic Nuclear Modernisation Over the Next Thirty Years’, James Martin Centre for Nonproliferation Studies.

23 David Vine (2012), ‘The Lily-Pad Strategy: How the Pentagon is Quietly Transforming its Overseas Base Empire and Creating a Dangerous New Way of War’, Tom Dispatch, 15 July; Nick Turse (2014), ‘The Special Ops Surge: America’s Secret War in 134 Countries’ Tom Dispatch, 16 January.

24 Michael Beckley (2011/12), ‘China’s Century? Why America’s Edge will Endure’, International Security, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 41-78.

25 Joshua R Itzkowitz Shifrinson and Michael Beckley (2012/13), ‘Correspondence; Debating China’s Rise and US Decline’, International Security, vol. 77, no. 3, p. 178.

26 Beckley, pp. 63-73.

27 Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin (2012), ‘The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire’, London: Verso, p. 298.

28 Chengxin Pan (2009), ‘What is Chinese About Chinese Business? Locating the ‘Rise of China’ in Global Production Networks’, Journal of Contemporary Asia, vol. 18, no. 58, pp. 15-20.

29 Panitch and Gindin, p. 289.

30 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan (2012), ‘Why the US Military Budget is “Foolish and Sustainable”’, Orbis, vol. 56, no. 2, p. 179.

31 John Frewen (2010), ‘Harmonious Ocean? Chinese Aircraft Carriers and the Australia-US Alliance’, Joint Force Quarterly, Issue 59, 4th quarter, p. 69.

32 Andrew Davies and Benjamin Schreer (2011), ‘Whither US forces? US Military Presence in the Asia-Pacific and the Implications for Australia’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 8 September, p. 4.

33 Justin Kelly (2012), ‘Fighting China: AirSea battle and Australia’, Australian Army Journal, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 157.

34 Sugio Takahashi (2014), ‘New QDR, New NDPG, and New Defence Guidelines’, The Association of Japanese Institutes of Strategic Studies (AJISS) Commentary, no. 198, 15 May.

35 Defence White Paper (2013), Commonwealth of Australia, p. 29.

36 Andrew Davies and Mark Thompson (2010), ‘Known Unknowns: Uncertainty About the Future of the Asia-Pacific’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, issue 35, p. 10.

37 Craig A Snyder (2012), ‘Security in the South China Sea’, Corbett Paper No. 3, Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies, London; Mark J Valencia (2010), ‘The South China Sea: Back to the Future?’ Global Asia, vol. 5, no. 4, p. 10.

38 Every joint communique issued at the Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) since 2010 has reiterated the ‘importance of peace and stability, respect for international law, unimpeded lawful commerce, and freedom of navigation in the East and South China Sea’. Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

39 Ralf Emmers (2013), ‘The US Rebalancing Strategy: Impact on the South China Sea’ in Leszek Buszynski and Christopher Roberts, eds, The South China Sea and Australia’s Regional Security Environment, National Security College Occasional Paper, no. 5, September, p. 41-2.

40 Gareth Evans (2013), ‘The South China Sea and Australia’s Regional Security Environment’, speech to the launch of the Australian National University’s National Security College Occasional Paper No 5, 2 October, p. 2.

41 Mark J Valencia (2010), ‘The South China Sea: Back to the Future?’; (2011), ‘Foreign Military in Asian EEZs: Conflict Ahead?’, The National Bureau of Asian Research, Special Report No. 27.

42 Leszek Buszynski (2012), ‘The South China Sea: Oil, Maritime Claims, and US-China Strategic Rivalry“, The Washington Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 2, p. 144; (2012), ‘Chinese Naval Strategy, the United States, ASEAN and the South China Sea’, Security Challenges, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 19-32. Ross makes a similar point when he argues that the threat posed to Chinese security by an aggressive US interventionist policy on China’s periphery has provoked a hawkish response from Beijing. Robert S Ross (2012), ‘The Problem With the Pivot: Obama’s New Asia Policy Is Unnecessary and Counterproductive’, Foreign Affairs, November/December.

43 Gavan McCormack (2012), ‘Troubled Seas: Japan’s Pacific and East China Sea Domains (and Claims)’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 10, issue 36, no. 4.

44 Geoff Dyer (2014), ‘Barack Obama Says Disputed Islands Covered by Japan Pact’, Financial Times, 23 April.

45 Robert Ayson (2005), ‘Regional Stability in the Asia-Pacific: Towards a Conceptual Understanding’ Asian Security, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 196-198.

46 Mark Beeson (2009), ‘The United States and East Asia: The decline of long-distance leadership?’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 43-1-09. McCormack makes a similar point with respect to the normalisation of differences between Japan and South Korea and North and South Korea. If ‘peace broke out in East Asia’, McCormack writes, ‘the justification for the sprawling US military base presence in South Korea and Japan would disappear’. Gavan McCormack (2004), Target North Korea: Pushing North Korea to the Brink of Nuclear Catastrophe, Sydney: Random House Australia, pp. 144-5.

47 Quoted in Chengxin Pan (2014), ‘The “Indo-Pacific” and Geopolitical Anxieties About China’s Rise in the Asian Regional Order’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, vol. 68, no. 4, p. 458.

48 Pan. Also see Jae Jeok Park (2011), ‘The US-led Alliances in the Asia-Pacific: Hedge Against Potential Threats or an Undesirable Multilateral Security Order?’, The Pacific Review, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 137-158.

49 Davies and Schreer, p. 1.

50 Eddie Walsh (2011), ‘America’s Southern Anchor?’ The Diplomat, 25 August.

51 Brendan Nicholsan (2010), ‘US Forces Get Nod To Share Our Bases’, The Australian, 6 November.

52 Richard Tanter (2012), ‘After Obama – The New Joint Facilities’, Nautilis Institute for Security and Sustainability, 18 April, pp. 12-15.

53 (2012) ‘US Force Posture Strategy in the Asia Pacific Region: An Independent Assessment’, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, August, pp. 74-5.

54 Richard Tanter (2012), ‘Memo Stephen Smith: there are US bases in Australia and they are expanding’, The Conversation.

55 Gemma Daley and Marcus Priest (2012), ‘Smith Confirms Cocos As US Base Option’, Australian Financial Review, 28 March.

56 (2012), ‘Coalition Backs US Drone Base On Cocos Islands’, ABC, 29 March.

57 Cameron Stewart (2013), ‘US Boosts Regional Military Footprint’, The Australian, 23 August; James Brown (2013), ‘US Reveals New Darwin Marines Move’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute for International Policy, 23 August.

58 Jim Thomas, Zack Cooper, Iskander Rehman (2013), ‘Gateway to the Indo-Pacific: Australian Defence Strategy and the Future of the Australia-US Alliance’, Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, November.

59 Thomas et. al, pp. 1 and 6.

60 2014 Report to the Senate Armed Services Committee, p. 21.

61 (2014), Statement of Admiral Samuel J Locklear, US Commander of Pacific Command, 2014 Report to the Senate Armed Services Committee, 25 March, pp. 17-18.

62 Ely Ratner (2013), ‘Resident Power: Building a Politically Sustainable US Military Presence in Southeast Asia and Australia’, Centre for a New American Security, October, p. 15.

63 Vine. Also see Jonathan Bogais (2014), ‘Asia-Pacific Focus Will Revitalise US Hegemony, But At What Price?’, The Conversation, 4 March.

64 Richard Tanter (2012), ‘The “Joint Facilities” Revisited – Desmond Ball, Democratic Debate on Security, and the Human Interest’, Nautilis Institute for Security and Sustainability, 11 December, p. 32-37.

65 Tanter, ‘After Obama’, p. 6.

66 Phillip Dorling (2013), ‘Snowden Reveals Australia’s links to US spy web’, The Age, 8 July; (2013), ‘US spying on our neighbours through embassies’, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 October; (2013), ‘Exposed: Australia’s Asia spy network’, The Age, 31 October; (2014), “Edward Snowden documents show Malaysia is an Australia, US intelligence target’, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 March.

67 Philip Dorling (2013), ‘Pine Gap Drives US Drone Kills’, The Age, 21 July; Richard Tanter (2013), ‘The US Military Presence in Australia: Asymmetrical Alliance Cooperation and its Alternatives’, The Asia Pacific Journal, vol. 11, issue 45, no. 1, November 11.

68 The American defence facilities at North West Cape, Pine Gap and Nurrungar were all considered to be highly likely nuclear targets of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and not ‘only’ during a general nuclear war. Moreover, their presence invited a nuclear attack on other Australian military bases and facilities and even Australian cities. Desmond Ball (1980), A Suitable Piece of Real Estate: American Installations in Australia, Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, pp. 130-138.

69 Davies and Schreer, pp. 5-6.

70 Thomas et. al, pp. 24-26.

71 Thomas et. al, p. 27.

72 Brendan Nicholson (2012), ‘Secret “war” with China uncovered’, The Australian, 2 June 2012.

73 Brendan Taylor (2013), ‘The Defence White Paper 2013 and Australia’s Strategic Environment’, Security Challenges, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 15-22; Benjamin Schreer (2013), ‘Business as Usual? The 2013 Defence White Paper and the US Alliance’, Security Challenges, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 35-42.

74 (2011), ‘Australia could be caught in Sino-US crossfire’, People’s Daily, 16 November.

75 John Kerry and Robert Guy (2011), ‘New base for Indian Ocean’, Australian Financial Review, 19 November.

76 Michael Sainsbury (2010), ‘Australia could be a martyr, says Brigadier General John Frewen’, The Australian, 16 November.

77 Hugh White (2005), ‘The Limits to Optimism: Australia and the Rise of China’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, vol. 59, no. 4, December, pp. 469-80; Hugh White (2010), ‘Power Shift: Australia’s future between Washington and Beijing’ Quarterly Essay, vol. 39, pp. 1-74; Hugh White (2012), The China Choice: Why America Should Share Power, Collingwood, VIC: Black Inc.

78 Malcolm Fraser and Cain Roberts (2014), Dangerous Allies, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp. 276-77.

79 The Sydney Morning Herald’s political and international editor, Peter Hartcher, describes the response to Fraser’s call to break the Australia-US alliance as ‘the great silence’. Peter Hartcher (2014), ‘Does Australia Really Need the US alliance’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 May.

80 Paul Kelly (2012), ‘China Divides Labor Across its Generations’, The Australian, 11 August.

81 Paul Dibb (2012), ‘Why I Disagree with Hugh White on China’s Rise’, The Australian, 13 August; Brad Glosserman (2011), ‘The Australian Canary’, The Diplomat, 23 November.

82 Greg Sheridan (2010), ‘Distorted Vision of Future US-China relations’, The Australian, 11 September.

83 Geoff Wade (2014), ‘Australia, the United States and China: The Debate Continues’, Flagpost, Australian Parliamentary Library, 16 June.

84 Peter Ker (2011), ‘Palmer Blasts Obama’s Marines Plan For NT’, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 November.

85 Angus Grigg, Perry Williams and Jamie Freed (2011), ‘Guess Hu’s Not Coming To Dinner’, Australian Financial Review, 18 November; Tony Walker (2011), ‘All The Way With Obama’, Australian Financial Review, 19 November.

86 Greg Earl, Ben Holgate and Jacob Greber (2012), ‘Stokes And Packer: We Need To Bow To China’, Australian Financial Review, 14 September; Tony Walker (2012), ‘China Can’t Buy Australia, Says Defence Secretary’, Australian Financial Review, 20 September.

87 Nick Bisley ‘“An Ally For All The Years to Come”: Why Australia Is Not A Conflicted US Ally’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, vol. 67, no. 4, p. 12.

88 The US Alliance 2005-2014, Lowy Institute for International Policy Interactive Poll, available from .

89 (2012), Michael J. Green interview with former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, ‘Discussing Global Trends with Former Australian P.M. Kevin Rudd’, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2 April, available from,

.

90 The United States Studies Centre (2007), ‘Australian Attitudes Towards the United States: Foreign Policy, Security, Economics and Trade’, presentation by Professor Murray Goot, 3 October, p. 17, available from .

91 1951 Security Treaty Between Australia, New Zealand and the United States (ANZUS), full text available from .

92 Support for US bases in Australia was 55 per cent in 2011, 74 per cent in 2012 and 61 per cent in 2013 according to the 2011-2013 Lowy Institute Poll, available from .

93 Lowy Institute for International Policy (2013), ‘Australia and the World: Public Opinion and Foreign Policy’, p. 8, available from

94 Robert S Ross (2013), ‘The US Pivot to Asia and Implications for Australia’, Centre of Gravity Series, ANU Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, available from .

95 Paul Dibb (2014), ‘Manoeuvres Make Waves but in Truth Chinese Navy is a Paper Tiger’, The Australian, 7 March, available from, ; (2011), ‘Knocking on Nobody’s Door’, The Australian, 18 July, available from .

96 James Ingram (2011), ‘A Time for Change – The Alliance and Australian Foreign Policy’, address to the Australian Institute of International Affairs, 9 June.

97 Lowy Institute for International Policy (2014), ‘Australia and the World: Public Opinion and Foreign Policy’, p. 5, available from .

98 (2013), ‘America’s Global Image Remains More Positive than China’s’, July 18, Pew Research Centre, available from .

99 Lowy Institute for International Policy (2013), p. 13.

100 Benjamin Schreer (2013), ‘Moving Beyond Ambitions? Indonesia’s Military Modernisation’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November, available from .

101 Desmond Ball (2001), ‘The Strategic Essence’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 245-246.

102 Paul Dibb (2007), ‘Australia-United States’ in Brendan Taylor (ed), Australia as an Asia Pacific Regional Power: Friendship in Flux, Oxon: Routledge, pp. 33-49.

103 Ball, p. 245.

104 Anthony Burke (2008), Fear of Security: Australia’s Invasion Anxiety, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds (2009), Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the International Challenge of Racial Equality, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; David Walker (1999), Anxious Nation: Australia and the Rise of Asia 1850-1939, St Lucia, QLD: University of Queensland Press; Alan Renouf (1979), The Frightened Country, South Melbourne: MacMillan.