With its economy devastated by war, its national glory sullied by ignominious defeats at the hands of Germany and Japan, and its colonial legacy morally undercut by the Atlantic Charter, France in 1945 faced immense challenges. Especially daunting was the job of restoring its empire, particularly in distant Indochina.

For French political leaders and imperialists who equated empire with national greatness, simply granting Indochina its independence was out of the question. But reoccupying the lost colony would be no easy matter. Certainly the tremendous task of rebuilding at home left few resources to spare for a tropical war against native rebels thousands of miles away. Mobilizing the needed resources would require generating political enthusiasm, not mere public acquiescence, for a costly foreign adventure. Yet the once powerful colonial lobby,1 composed of overseas traders, investors, bankers, soldiers and civil servants, had seen its economic base largely wiped out by the war.

Supporters of France’s imperial mission hit upon a novel way to restore the economic fortunes and thus the political clout of the colonial lobby: issuing a decree to overvalue the Indochinese piaster. That obscure and apparently technical financial decision gave soldiers, bureaucrats and businessmen a powerful profit motive to serve in Indochina. Above all, it greatly inflated their buying power. By giving them more francs for every piaster they earned in Indochina, a high exchange rate allowed them to stretch their money. They could import goods from France on the cheap, including luxuries they could otherwise never afford. Any piasters they chose to save rather than spend could be repatriated at a premium in francs to family members or others in France.

Of course, this huge subsidy to colonial interests was not free: It had to be paid for either by French taxpayers or through the “printing” of francs by government monetary authorities, creating inflation that taxed the purchasing power of French consumers.

As long as the cost was modest, it could be easily disguised, minimizing any political consequences. Over time, however, the cost soared and this financial policy blew up in the face of French leaders who instituted it as a tool for promoting colonialism. Beneficiaries, including not only French citizens in Indochina but their privileged Indochinese allies, figured out how to reap huge profits from currency exchange rackets between Indochina and France. The resulting piaster traffic ballooned the cost of war and corrupted the French polity. The profiteering unleashed by the currency racket eventually triggered one of the Fourth Republic’s worst political scandals and fed the public’s darkest suspicions about their leaders. The epithet “dirty war” stuck inexorably to the Indochina campaign, setting the stage for popular acceptance of France’s withdrawal from the colony.

In taking over from France in 1954 as the dominant foreign power, the United States inherited all the challenges that made Paris capitulate after immense loss of lives and treasure. Washington had a chance to learn from France’s mistakes. Instead, among the many lessons that American policy makers failed to learn from the French defeat was the cost—political as well as economic—of trying to buy support for an unpopular war. In Vietnam, and to a lesser extent Laos, hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. aid went to support over-valued exchange rates, in turn spawning profiteering and corruption. As in the French era, these rackets tainted the war effort. Spreading corruption sapped the moral underpinnings of the anti-Communist cause, casting a mercenary pall over the righteous claims of war supporters.

Piaster profits did not cause the two Indochina wars, but they did initially sustain—and then powerfully undermine—both the French and American operations. This account is the first to explore the remarkable continuity and disastrous impact over more than two decades of the French and American experiences with currency corruption. It taps long-forgotten published accounts, including the findings of several parliamentary and congressional investigations, as well as unpublished State Department files, FBI records and other government and private archives that shed new light on the intersection of war, politics and crime.2

Origins: 1945

World War II had barely ended before attempts to profit from Indochina’s currency began guiding struggles over the territory’s political and economic future. Those struggles resulted from France’s prostrate condition. The July 1945 Potsdam Accord acknowledged France’s rights as a colonial authority in Indochina, but also its inability to exercise power there in the immediate future. The Allies gave China the green light to accept Japan’s surrender and occupy Indochina north of the 16th parallel. In the south, thousands of British and Indian troops landed in September, quickly supplementing their forces with former French prisoners of war and cooperating Japanese troops. By the time General Philippe Leclerc managed to lead a French contingent to Saigon in October 1945, the nationalist Viet Minh resistance had formed a provisional government in Hanoi and was regularly attacking the British-led military coalition in the south.

Under cover of the British military campaign to suppress the Viet Minh, the French began reasserting administrative control. As one of his first moves, the new French High Commissioner in Saigon, Admiral Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, proposed setting a high value on Indochina’s currency, the piaster, to demonstrate France’s resolute commitment to the colony. In December 1945, the French government pegged the rate at 17 francs to the piaster—far above its prewar value of 10 francs.3

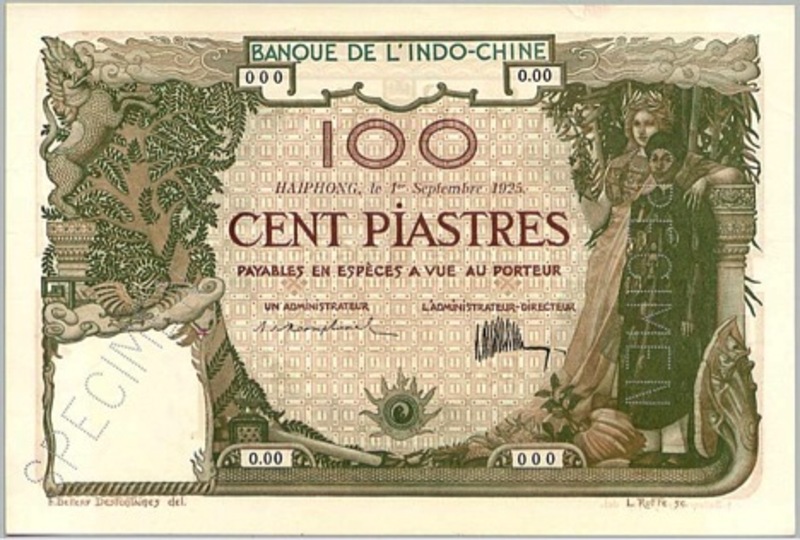

|

100 Piaster note, circa 1925. Source: Wikipedia |

Two key decision makers were the High Commissioner’s chief financial adviser, François Bloch-Lainé, and Finance Minister René Pleven. Both were allies of the Bank of Indochina, one of the leaders of the colonial lobby in France.4 The private but government-sanctioned bank enjoyed the sole privilege of issuing currency in the colony, giving it a powerful financial interest in a strong piaster. But the bank and its political allies faced two major obstacles to the strong-piaster policy: Guomindang China’s rapacious occupation in the north, and Japan’s decision in March 1945 to print thousands of 500 piaster notes, triggering widespread inflation. If holders of those notes could convert them into francs at the new exchange rate, the cost to the French Treasury and the franc would be enormous.

The 500-Piaster Note Crisis

China’s theater commander, General Lu Han, lost no time plundering northern Vietnam, using the piaster as one of his weapons. In the fall of 1945, he issued a decree increasing the exchange value of the Customs Gold Unit (a currency issued by the Central Bank of China) by 50 percent, from one to 1.5 piasters. This fiat devaluation of the piaster made goods in Indochina look cheap to holders of Chinese currency, while making imports dear to Indochinese farmers and workers. The new rate allowed Chinese occupiers to buy up food, real estate and entire businesses at bargain basement prices, squeezing out resentful native buyers.5

Americans in the theater enjoyed a good deal, too. They could buy Chinese gold units cheaply in Hong Kong, taking advantage of the wartime depreciation of China’s currency against the U.S. dollar,6 and then exchange them for piasters, earning up to six times the official dollar rate of exchange for piasters. No wonder one U.S. diplomat in Hanoi commented in 1946, “Commerce in the past year has been chiefly a matter of gambling with exchange .”7

Equally threatening to the French—and to the value of the piastre—was Lu Han’s insistence that the Bank of Indochina redeem any and all 500-piaster notes issued by the Japanese earlier in the year. In November 1945, seeking to reassert their economic and political authority and prevent runaway inflation, French authorities announced they would no longer redeem the big notes. Thousands of Chinese merchants and Vietnamese families who held those notes faced significant losses and even bankruptcy. The Viet Minh, which had also amassed the notes, organized a mass demonstration outside the bank’s Hanoi office. When guards fired on the crowd, killing several demonstrators, merchants and workers then went on strike and refused to sell food to the French. Lu Han’s troops arrested the bank’s general manager and Hanoi branch manager.8

After mediation from a senior American officer, the French allowed the 500-piaster notes to circulate north of the 16th parallel, at full par value for those held by the Chinese army, but at a discount for Vietnamese holders.9 The bitterness created by the incident took longer to address. A month after the settlement, the Bank of Indochina’s Hanoi branch manager was murdered. Pinned to his chest was a note: “Thus will die those who put themselves in the way of the Vietnamese economy.”10

The Viet Minh’s efforts to create an independent Vietnamese economy as a step toward full national sovereignty advanced with the signing on March 6, 1946 of a landmark Franco-Vietnamese accord, which granted Vietnam rights as a free state within the French union. The accord, signed by the same French diplomat who negotiated a resolution to the 500-piaster note controversy, represented the high point of efforts by French realists to negotiate a peaceful future for Indochina. But it ran afoul of opposition from die-hard colonialists—who manipulated concerns over the piaster to frustrate implementation of the agreement and plunge the territory into war.

The immediate concern raised by French officials was the flooding of Vietnam with consumer goods imported by Chinese merchants. Excessive imports put pressure on the value of the piaster, which the French were trying to boost. To curb imports and protect the piaster, French authorities in October 1946 established a customs house in Haiphong, the main northern port. Not by accident, this unilateral assertion of French authority also had the effect of denying customs revenues to Ho’s government. The Viet Minh cried foul, claiming that the French had violated terms of the March 6 accord. The customs dispute, which now raised fundamental questions of political sovereignty and nationalism, triggered street fighting in Haiphong on November 20. Commissioner d’Argenlieu, who never accepted the premise of a peaceful devolution of power to the Vietnamese, had been looking for just such an opportunity to strike back against Ho Chi Minh and his supporters in the North. The French military launched a savage naval bombardment of the port, killing several thousand civilians. Military officials in Indochina suppressed news of the massacre. They also held up transmission of a telegram by Ho Chi Minh to French Premier Léon Blum proposing a peaceful compromise. Hearing nothing back from Paris, Viet Minh forces attacked the French, killing about 40 soldiers and capturing about 200. When French military forces counterattacked throughout Tonkin, there was no turning back from war.11

|

As France’s High Commissioner in Indochina, Admiral d’Argenlieu supported the overvaluation of the piaster to strengthen France’s ties to Indochina. Source |

The Piaster Traffic

Defenders of the official overvaluation of the piaster justified it, without embarrassment, as a financial reward to those who supported France’s colonial mission: the soldiers who endured hardship and danger to fight the Viet Minh, and native supporters of France in the Associated States of Indochina. Expeditionary Corps soldiers were able to stretch their paychecks every time they remitted piasters home to France at the official exchange rate. And France’s local clients, who gave the colonial mission its thin veneer of legitimacy, enjoyed great buying power at 17 francs to the piaster. The strong piaster also made Indochina a profitable market for French exporters, thus building political support for colonialism in metropolitan France.12 But the yawning gap between the official rate and the black market rate of 7 or 8 francs to the piaster also created an irresistible lure to profiteers who gamed the system.13

Official exchanges of piasters to francs went through the Bank of Indochina. Any resident of Indochina could make bank transfers of up to 50,000 francs a month or remit up to 5,000 francs a month via postal orders. Soldiers and public officials had some special transfer rights. Other transfers required special authorization from the Office Indochinois des Changes—the official gatekeeper to the piaster traffic.14

A trafficker would typically start by buying dollars or gold outside of Indochina. A U.S. dollar purchased for 350 francs in France, then smuggled into the colony, might buy 52 piasters from a local black marketeer. Delivered to the Bank of Indochina for legal remittance to France, those piasters in turn would buy 884 francs—well over double the initial investment. The profits on this “round trip” were limited only by how much currency one could carry, and how many piasters were approved for exchange at the official rate.15

A simple, and nearly undetectable, means of exploiting the artificial exchange rate was to under-invoice imports.16 Either using a foreign subsidiary or secret agreement with another company in France, an importer in Indochina would overpay for goods received. The importer would receive authorization from the exchange office to remit the inflated sum at the high official exchange rate. The partner or affiliate in France would then bank the extra francs on behalf of the importer.

Under-invoicing was a common practice. French investigators found examples of a shipment of watches, worth 21 million francs, that was valued at 149 million; bolts of cloth worth 10 million francs that were valued at 28 million; and worthless old boat motors valued at nearly 39 million francs. In some cases parties made requests for piaster transfers for entirely fictitious imports.17

The exchange office had neither the staff nor the expertise to check the bona fides of such transactions. Nor did it have much motivation to crack down, given the climate of official corruption fostered by the French administration, which earned millions of dollars from gambling revenue and the sale of opium. As Life magazine’s David Duncan reported in 1953, “In the background of this war is a society that has become corrupt. As far as I could determine everything is for sale, from little favors in police courts to the highest offices.”18

The Generals’ Affair

Rampant corruption played into the hands of the French Communist Party, the one reliably anti-colonialist political faction. In 1948 it introduced the epithet, the “dirty war.” Two years later, a huge scandal with links to the piaster traffic helped make that term a household phrase. As historian Jacques Dalloz described it,

The affair of the generals was in the headlines for the whole of 1950. To top it all, the press devoted passage upon passage to the Indo-China war, but only to mention obscure plots, dubious people, stories about cheques, secret ambitions and the secret services, and even secret societies. . . .The public could only be worried by these revelations which threw a harsh light on the relationships between military chiefs and political circles . . . on the rivalries between special services, and on the corruption which had increased in the shadow of the war.19

The Generals’ Affair involved factional struggles between the Socialist Party and the Catholic, pro-colonialist Mouvement Républicain Populaire (MRP); between the foreign intelligence service, Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage (SDECE), and the domestic Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST); and even between Catholics and Masons.20 It began with the embarrassing leak of a top-secret report on the Indochina campaign by Army Chief of Staff General Georges Revers, who was sent on a study mission to the territory in mid-1949 by the Socialist defense minister, Paul Ramadier. Revers’s critical report recommended pulling back French forces to shorten their supply lines, turning the fighting over to native soldiers, and unifying civil and military authority under one leader. His pessimistic conclusions reflected badly on the MRP’s hard-line colonial policies, including those of High Commissioner Léon Pignon. 21

After the Viet Minh began airing embarrassing excerpts on its radio broadcasts, French authorities traced the leak to a man close to Emperor Bao Dai’s delegation in Paris, Roger Peyré. This thoroughly unscrupulous character—a convicted embezzler, Nazi collaborator, postwar SDECE agent and influence peddler—managed to use his masonic connections to win Revers’s confidence. Revers sent Peyré to Indochina to influence the appointment of a trusted friend as civil-military leader in the territory.

Investigation revealed that one of Peyré’s aims in getting close to Revers and other senior officials was to gain “control of the Indochina Exchange Office” in order to profit from the piaster traffic.22 He allegedly told a senior officer in SDECE, “There’s certainly quite a lot of money to be made from the piaster. It’s interesting with the exchange, one can do quite a lot of things.”23 Meanwhile, one of Peyré’s other defenders in SDECE campaigned behind the scenes against key Socialist ministers, accusing them of trying to hide their party’s financial reliance on the piaster traffic.24

These associations brought the piaster traffic to widespread public attention for the first time. Questioned by one Communist member of a parliament commission that investigated the affair in 1950, Revers confirmed the existence of the traffic and named major banks and trading companies as likely profiteers from overvaluation of the piaster.25 “For six months all of France read the accounts every day for new revelations,” the acting head of SDECE recalled years later. “Politicians had received graft money . . . An ugly traffic in monetary exchange existed between Vietnam and France while French soldiers were being killed. . . . It was like a sewer suddenly opened. The public was nauseated by the dishonesty of their politicians and the administration.”26

Doubts about the Piaster

But further efforts by members of parliament to investigate the piaster scandal went nowhere.27 One inhibiting factor was the untimely death of two key individuals in back-to-back crashes of decrepit Saigon-to-Paris airliners in the summer of 1950. Among the dead was the head of the exchange office in Saigon, who disapproved of the special treatment granted to politically connected Indochinese, allowing them “to profit from the disparity of prices between Indochina and France to effect massive transfers of their fortunes to France.” Another victim was a leading French reporter who was investigating leading officials in the Saigon administration and Bao Dai’s entourage for currency profiteering.28

Behind the scenes, Finance Minister Pleven in 1950 was having serious doubts about the wisdom of maintaining the piaster’s severely overvalued rate, given the growing burden of financing the war in Indochina.29 The volume of official piaster exchanges—and thus arguably the burden on the French Treasury—was roughly doubling every two years, from 61 billion francs in 1948, to 135 billion francs in 1950, to 224 billion in 1952.30 (The latter sum was equal to about $5.7 billion in 2014 dollars.31)

Pleven dispatched a senior Finance official to Indochina in early 1950 to study the viability of devaluing the piaster. He reported back that the official exchange office represented at best only a “fragile barrier” against currency fraud. It had woefully inadequate staff, little funding for investigations, and virtually no legal authority to block dubious transfer requests. His report recommended devaluing the piaster as the “most effective” way to curb the growing traffic.32

But Pleven got cold feet when other advisers warned that devaluing the piaster could demoralize hard-pressed French expeditionary troops. The Minister of the Associated States, Jean Letourneau, threatened to resign if the piaster were devalued. Pleven ended up doing nothing, save asking the new high commissioner for Indochina to put an end to the traffic. “It was a situation that disquieted us, that preoccupied us, for which I truly had the feeling that, from Paris, we had done all we could do,” Pleven later testified.33

Despuech’s Exposé

Finally, in late 1952, a former employee of the exchange office blew the whistle on the piaster traffic in a long article in Le Monde, which he followed the next year with a book-length exposé.34 Jacques Despuech claimed that fraudulent transfers were costing the French Treasury a staggering 100 billion francs each year (more than $2.5 billion in 2014 dollars).35

Prominent among the profiteers, according to Despuech, was the Vietnamese figurehead Bao Dai, who was permitted to transfer piasters worth 176.5 million francs in 1949 alone, as the price of his support. The total volume of “political” transfers on behalf of France’s local clients came to 426.7 million francs that year, Despuech claimed.36

|

Jacques Despuech’s 1953 blockbuster exposed what one French newspaper called “the scandal of the century.” |

Also implicated were members of the powerful Corsican community in Indochina. Chief among them was Mathieu Franchini, owner of two of Saigon’s largest hotels, and reputed to be one of the country’s leading opium traffickers. He was suspected of corrupting employees in the exchange office to facilitate his trafficking, possibly with help from a French military intelligence officer.37

Perhaps the most prominent target of Despuech’s expose was André Diethelm, the senior Gaullist parliamentarian, Vice President of the National Assembly, former Finance Director of Indochina, and a close ally of the Bank of Indochina.38 Diethelm initially denied everything, but eventually colleagues confirmed that he had remitted 17 million francs in 1949 on behalf of the Gaullist party to rescue its perilous finances. If Diethelm needed any help with this transaction, he could have turned to many of the experienced Corsican gangsters in Saigon who were Gaullist activists.39

Despuech also condemned various financial trusts, led by the Bank of Indochina, for engaging in capital flight at the expense of the former colony.40 A Communist member of the National Assembly accused the Bank of Indochina of using secret accounts with false names to swindle France out of vast sums through the exchange racket. Such charges struck many French observers as entirely plausible, but the bank’s leading historian, Marc Meuleau, concluded that it “did not seek to make an illegal profit from the disparity between the official market and the black market.”

On the other hand, Meuleau readily conceded that the Bank of Indochina made out exceptionally well, quite legally, by systematically selling its assets in Indochina and repatriating the profits at a premium. From 1946 to1953, he estimated, the bank transferred the equivalent of 6.9 billion francs. Given the artificial value of the piaster, the bank’s profit on those transfers amounted to about 2.9 billion francs.41

Many in France were scandalized most by Despuech’s claim that the Viet Minh were profiting from the same racket. His claim was supported by a 1951 story by Associated Press reporter Seymour Topping, which French authorities tried to suppress. Topping reported that French racketeers were “helping to finance large scale purchases of war material by the Communist-led Viet Minh” by turning over a million dollars a month or more in hard currencies in exchange for piasters “at the expense of the French taxpayer.” A key player in this corrupt network was said to be “a senior Chinese employee of the Bank of Indochina.”42 Topping concluded that the French government took no action because it “feared a scandal that would damage it politically.”43

Unknown to the French public, members of the U.S. embassy and aid mission in Indochina, and even American evangelical missionaries, were also playing the black market to avoid paying inflated official prices for piasters.44 A senior official of the U.S. Mutual Security Agency explained, “Living conditions in the Associated States are notoriously difficult—humidity, insecurity, insects and disease are only part of the troubles encountered—so that the Americans in charge in the area felt themselves in no position to insist on strict adherence to the letter of the law.”45 The State Department warned the Saigon embassy in a top secret dispatch that this practice “leaves us open to allegation that US [dollars] emanating official personnel Indochina [are] finding way into CHI COMMIE, Vietminh and other enemy hands and facilitating illegal transfer of capital from Vietnam.” The embassy replied that exchanging at the official rate would impose an “intolerable hardship” on financially strapped foreign service and aid mission personnel and “make it impossible for us to operate.”46 Washington eventually backed down, accepting the embassy’s assurances that French officials “tacitly approve our proposed method obtaining piasters.”47

Public Outrage

Publication of Despuech’s first article in November 1952—in a political climate already poisoned by the Generals’ Affair—caused an instant stir. The chair of the parliamentary committee overseeing pensions for veterans demanded an accounting. “The Government cannot be ignorant of this scandal,” he charged. “The piaster traffic continues to the detriment of our currency, of our reserves, and of our budget, and to the profit not only of notorious traffickers but also of the Viet-Minh. ”48

The Minister of the Associated States, Letourneau, said he was making “every effort” to quash currency rackets but insisted that “the famous piaster scandal . . . is enormously exaggerated.” Any move to devalue the piaster, he claimed, would simply force Paris to increase pay for soldiers, thus canceling any budgetary savings.49

Critics had their eye on profiteers other than ordinary soldiers, however. Claude Cheysson, Socialist counselor to the president of the government of Indochina in 1952, complained privately that the French business community in Indochina “will never hesitate to turn a dishonest piaster into an even more dishonest franc and while engaged in these lucrative pursuits, will continue to operate with serene disregard for major permanent interests of France, as well as those of her soldiers and taxpayers.”50

American officials privately griped as well about the corrosive effect of the piaster traffic, and particularly its effect on the French budget, which Washington increasingly subsidized. The Saigon embassy noted that “the politically powerful French business community, the French bureaucracy, and military are opposed to devaluation because it would reduce the high profits and salaries they now enjoy.” It argued in early 1953 that the time had come

to begin to condition public and official opinion in the [Associated States], and in France, towards advantage of an early devaluation of piaster. It is almost certain that we will be asked to increase our arms aid program in 1954 and will be faced with a request for financial assistance to pay for enlargement of Vietnamese army, which must be increased if we are going to have an early victory over communism in this area. . . . We will expect to get value received for any additional contribution we make, which we cannot (repeat not) get at present rate of piaster.51

The embassy was painfully aware, however, of the French argument that premature devaluation could “evoke social unrest and political disturbances and add considerably to the burden and problems of war of the Governments of the Associated States.”52 As a senior official of the U.S. Mutual Security Agency cautioned, “this is a matter of extreme delicacy. The fate of all Southeast Asia may be at stake in this active battlefield” and “the cost of the loss of the area to the free world would be incalculably large.” For that reason, “We would be wiser to let the present situation continue, even at very large cost to the French government and to the United States taxpayer, than to proceed until we were fully convinced that we knew exactly where we stood.”53 The administration did gently broach the issue of devaluing the piaster in talks with French Prime Minister René Mayer in Washington in March 1953, without getting any commitments.54

Meanwhile, criticism within France continued to mount against piaster profiteering, peaking in early May, 1953. In the pages of Le Monde, journalist Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber condemned “certain French political groups” who “found in the Indochina war one of the principal sources of their revenue.” A senior Gaullist deputy acknowledged in the same pages that the traffic had created a deplorable climate of corruption in Indochina. The independent left Franc-Tireur ran three successive front-page editorials in early May 1953 denouncing the traffic as “the greatest scandal of the Fourth Republic.” Even the conservative political scientist and journalist Raymond Aron called for an official investigation, lest “war profiteers” be blamed for the continuation of the conflict.55

Devaluation

As this criticism reached a crescendo, the French Treasury announced on May 8 that it was slashing the official exchange rate for the piaster to 10 francs.56 A French adviser in Saigon described the reaction of powerful financial interests, and particularly the Bank of Indochina, as “violent and almost hateful.”57 Vietnam’s President Nguyen Van Tam sharply protested France’s failure to consult with the Associated States and warned that it could provoke “strong social agitation.”59 Even the Viet Minh condemned the devaluation in their propaganda.60

On the other hand, the Saigon embassy reported that the decision was “applauded in general by French political circles as means to end illicit financial transfers” and predicted “a savings to French military budget of approximately 50 to 70 billion francs per year.”61 Indeed, all evidence suggests that the devaluation dramatically curbed the currency traffic, as intended.62

On May 30, Franc-Tireur announced publication of Despuech’s book, saying it would expose the “scandal of the century” and “have the effect of a bomb.” Little more than a month later, the National Assembly voted unanimously for a special committee to investigate the piaster traffic. It did not issue its report until June 1954, after the fall of Dien Bien Phu. Long before then, however, highly publicized revelations from the commission’s hearings had dragged France’s moral claims into the sewer. As historian Alain Ruscio put it, “The scandals of the Indochina war added to an already detestable political climate a note of stink.”63 After hearing stories of piaster profiteering by public officials and business leaders from Saigon to Paris, few in France could any longer defend the “dirty war” and those with “dirty hands” who ran it.

|

100 Piaster note, circa 1954. Source: Wikipedia |

The Americans take over

For Washington, the French failure in Indochina was not an object lesson but a challenge: Surely with enough resources, and the right choice of local allies, the United States could succeed in preventing the further spread of communism in Indochina. Surely no peasant insurgency could defeat the strongest superpower on the globe.

Ironically, the primary U.S. weapon—money—became a two-edged sword that eventually cut deep into the legitimacy of the American intervention and of local regimes sustained by the dollar. As in French Indochina, American financial support to win the loyalty of local elites fostered immense corruption, sullying the mission that Washington strived so hard to sell as noble and selfless.

The French had overvalued the piaster, in part, in order to create artificial economic prosperity in Indochina, while dampening the risk of inflation. Through the magic of the exchange mechanism, money printed in the territory simply financed more imports at France’s expense, mitigating disruptive local price increases.

The same logic underpinned the chief U.S. aid program to the area after the French defeat. Called the Commercial Import Program, or CIP, it provided U.S. dollars to pay for hard-money imports. Licensed importers received dollars from their government, generally at a highly favorable exchange rate, in return for local currency. Those payments in turn financed the government’s military and civil functions. And cheap imports helped the emerging middle class to afford the trappings of Western affluence. Arthur Gardiner, director of the U.S. Operations Mission in Vietnam in 1959, called CIP “the greatest invention since the wheel.”64

Getting Rich Quick in Laos

But by supporting overvalued exchange rates, the program unintentionally became a magnet for corruption. In Laos, for example, the government set the official value of the kip, for licensed importers, at 35 to the dollar—three times its actual value. From 1955 to 1957, the United States contributed $40 million annually to finance Laos’ import program—a sum equal to about 40 percent of the country’s gross national product.65

“It did not take long for opportunists to amass fortunes by buying America’s aid dollars from the Lao government at the legal rate and then selling them on the open market, or by importing goods solely for transshipment to other countries,” writes historian Seth Jacobs.66 These opportunists included corrupt American contractors, who were allowed to convert payments from the Laotian government into dollars at three times the free-market rate.67

A 1958 expose by the Wall Street Journal, which prompted two congressional investigations, described imports of fancy cars, musical instruments, French perfume and other goods that were far beyond the means of all but a handful of Laotians. “Much of this is unsalable,” the story noted, “but it doesn’t matter; the importers have already made their profits from foreign exchange manipulations.” The drastic overvaluation of the kip, it noted, “sets the stage for fantastic profits. . . . A Laotian trader can buy 100,000 kip on the free money market for $1,000. He then applies for an import license for, say $1,000 worth of building cement, but puts up only 35,000 kip to get the $1,000 from the government at the official rate. This leaves him with 65,000 kip before he has even moved the goods.”68

One prominent critic of the program was King Savang Vatthana, who believed the American-financed tide of imports threatened to wipe out traditional handicraft industries. “Worst of all,” he said, “by promoting a desire to get rich quickly,” the program “destroyed the traditional concept of service which the Laotians expected from those in positions of trust and responsibility.”69

The growth of corruption within Laos fed support for the Communist Pathet Lao while undercutting support for aid in Congress. No less than Vice President Richard Nixon warned Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma in January 1958 that abuses were jeopardizing the future of the U.S. aid program. A senior State Department official told the prime minister that Laos must correct its unrealistic exchange rate and eliminate import licensing. But Souvanna Phouma and his finance minister insisted—as had French and Indochinese officials before them—that devaluing the kip “would have serious political, social, and economic consequences just before the upcoming Lao elections.”70

Washington backed off—but as it feared, public disgust with rampant corruption handed leftist parties a resounding victory in the May elections. Alarmed by the outcome, the U.S. embassy in Vientiane declared that to ensure a conservative victory in the next elections and prevent Communist domination, Vientiane must “promptly carry through monetary reform to eliminate source of corruption . . . Such a measure now more essential than ever to ‘purify’ morals of governing class.”71 To enforce its will, the Eisenhower administration briefly cut off aid, forcing the neutralist Souvanna Phouma from office and bringing Vientiane quickly to heel. By October 1958, the regime agreed to a new exchange rate of 80 kip to the dollar.72

However, history in Laos had a way of repeating itself, both as tragedy and as farce. In 1973, a congressional hearing would cite a report that a recent overvaluation of the kip had once again “proved convenient means whereby the Lao elite and Vietnamese and Chinese merchants have been able to convert their kip profits to dollars and put the money in Swiss and other banks, to import luxury goods for themselves and keep thriving Thai and Lao smuggling rackets in merchandise going full blast.”73

Vietnam: Licensed to Steal

In Vietnam, the Commercial Import Program provided more than $1 billion from 1955-60 alone to pay for imports and raise piaster “counterpart” funds for pay for the Saigon regime’s military and security programs. Peaking at just under $400 million a year in 1966, CIP enabled some genuine economic improvements, including the importation of thousands of sewing machines to revive the country’s clothing industry.74

Mostly, however, it propped up successive Saigon regimes by creating economic prosperity for some members of the urban middle class. According to the head of the U.S. aid mission in Vietnam, CIP “served the political value of supplying the Vietnamese middle-class with goods they wanted and could afford to buy,” thus creating “a source of loyalty to [Ngo Dinh] Diem from the army, the civil servants and small professional people, who were able to obtain better clothes, better household furnishings and equipment, than they had before.” Turning that benefit on its head, the regime critic Dr. Phan Quang Dan countered that the program “brings in on a massive scale luxury goods of all kinds, which give us an artificial society—enhanced material conditions that don’t amount to anything, and no sacrifice; it brings luxury to our ruing group and middle class, and luxury means corruption.”75

The biggest winners were cronies of the regime who were given licenses to import goods at the official exchange rate, which typically valued piasters at double or more the free market rate. With such an advantage, they “were assured a windfall profit whether or not they had entrepreneurial acumen,” notes historian George McT. Kahin. “Those who did not simply sold their licenses to experienced Chinese and still gained a large profit immediately.” A 1966 Pentagon analysis concluded that the overvalued exchange rate handed profits ranging from $200 million to $600 million a year to favored license holders. “So long as import profiteering is permitted to continue,” it concluded, “every $1 spent . . . on CIP can result in a 100% piaster domestic profit at least for some favored importer and about 50¢ ‘banked’ safely in the US through the black market by such political friends of the present regime in Saigon.”76

The rampant fraud offended Americans of all political stripes. Said Clement Johnston, chairman of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “The $20 million a month loss entailed by our maintenance of the fantastic artificial piastre rate is not going into public treasuries, it is going into private pockets.” Public support for the government in Vietnam, he warned, was “being shaken by the spectacle of the underserved enrichment of a favored group.”77

But corruption was not a Vietnamese monopoly. At a summit meeting of senior American and Vietnamese officials in 1965, the Minister of Economy and Finance, Truong Tai Ton, complained that, “The rush of US military men and their expenditures in US dollars have seriously disturbed our economy. The black market flourishes. Dollars introduced in the black market then feed illegal transactions (illicit trading of foreign exchange, smuggling, flight of assets, and, undoubtedly, even [Viet Cong] financial operations). The value and sovereignty of our currency are at stake.”78

This concern went largely unheeded by governments on both sides of the Pacific. One American who tried to blow the whistle was a civilian contract employee, Cornelius Hawkridge. Early on he learned of a huge black market in Saigon for Military Payment Certificates (MPCs), non-negotiable scrip usable only by accredited personnel in military establishments such as Post Exchanges (PXs), which sold a cornucopia of duty-free consumer and luxury goods. Hawkridge was able to trade dollars for MPCs at a 1:1.5 rate, convert them by various means back into dollars, and continue until he tired of the process.79 Similar profits were available from dollar-piaster exchanges. Civilian contractors could engage in such crimes with relative impunity, since they were not subject to military justice, and Vietnamese courts were reluctant to prosecute Americans.80

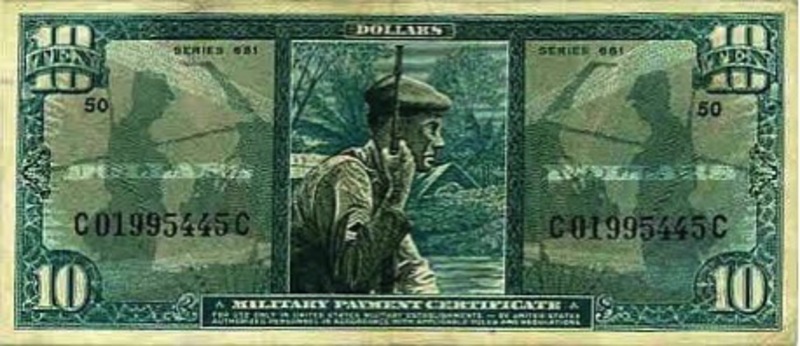

|

Military Payment Certificates were traded in Vietnam’s currency black market. Source |

Senior American investigators determined that the currency black market was led by a tight-knit syndicate of money changers from the Madras area of South India, with banking connections throughout the world. They worked closely with Chinese bankers in particular.81

The Indians had no shortage of clients. “Nearly everyone in Vietnam appeared to be engaged in currency manipulations,” Hawkridge recalled. “There was little point in exchanging money at the legal rate if one could get twice that amount from the Indian dealers.” When the U.S. military issued new MPCs to foil black marketers in 1969, “their business never faltered. The next day they had apparently unlimited stocks of the new issue.”82

Hawkridge also witnessed wholesale theft or diversion of U.S. military supplies and PX goods onto the vast Saigon black market—everything from cement and antibiotics to cases of weapons and ammunition. As Hawkridge noted, the underground commerce in stolen U.S. supplies fueled the black market in currency. In his jaundiced view, “Fighting the war was always a secondary issue; making money was the overwhelming consideration.”83

His complaints to U.S. officials, like those of other whistleblowers, mostly went unheeded.84 Eventually, however, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations exposed one of the more unseemly frauds of the era: the looting of the military clubs and PXs by a ring of sergeants that was led by the Army’s highest-ranking non-commissioned officer, Sergeant-Major William O. Woolridge. At least two generals were implicated as well. The investigation went all the way up to General William Westmoreland, with predictably inconclusive results.85

Bankers and Currency Racketeers

Some of the corrupt sergeants made more money through black-market currency deals than through kickbacks from military club suppliers.86 One of them told a subcommittee investigator, “every man I dealt with . . . during my entire tour in Vietnam was involved in currency manipulation. I don’t recall one company or one outfit that was not involved in it. This includes entertainers that only came over there . . . on a two-week tour.”87

Subcommittee investigators traced the black market exchange profits deposited into 13 accounts at several American and foreign banks. About $75 million a year flowed through those accounts from 1965 to 1968. Subcommittee investigator Carmine Bellino estimated the total size of Vietnam’s currency black market at a quarter of a billion dollars annually.88 Republican Senator Karl Mundt of South Dakota called it “absolutely incredible” that major U.S. banks lent themselves to such an obviously criminal enterprise. He rightly observed that “Without a laissez-faire or ‘see no evil’ policy on the part of the American banks which carried the code-named accounts . . . those accounts could not have been used so flagrantly as conduits for black market money.”89

One of the accounts, at Irving Trust, was first opened by a group of ethnic Chinese in 1949, most likely in order to profit from the piaster traffic under the French.90 Another big account at Manufacturers Hanover Trust, called Prysumeen, handled tens of millions of dollars in profits for clients of several Indian currency traders.91

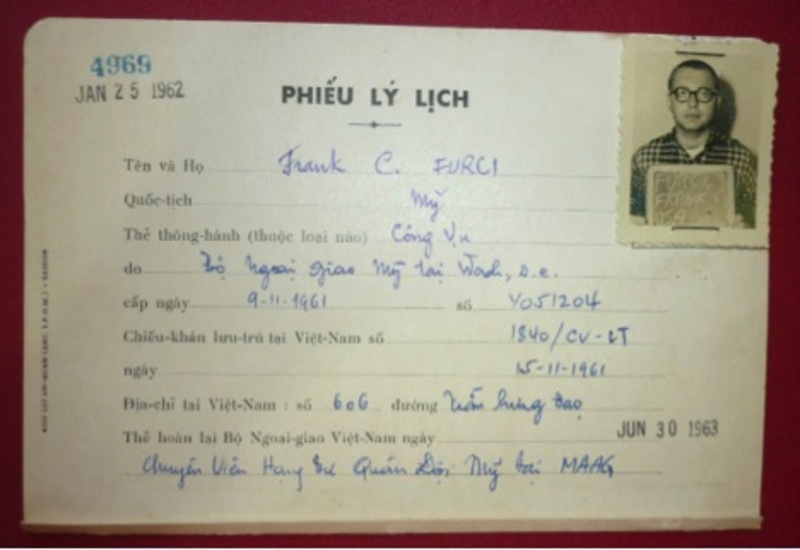

One modest but notable user of the Prysumeen currency trading account was Frank Furci, son of a South Florida gambler and mobster.92 Furci joined the Army in 1960 and went to Vietnam as part of the U.S. military mission in 1962. There, according to an FBI report, he was “alleged to be involved [in] black market activities.” He stayed on in country with a friend after his military discharge to run a business that imported restaurant equipment and supplies, doing about $2.5 million worth of business with military clubs and messes.93 Furci became a silent partner in a company used by the corrupt sergeants to profit from the clubs in Vietnam. He paid kickbacks into their account at the International Credit Bank of Geneva, a notorious money laundromat for sophisticated mafia leaders, founded by Mossad agent Tibor Rosenbaum.94

|

Frank Furci entered Vietnam in 1962 as a member of the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group |

Furci bought piasters at black market rates from the Hong Kong branch of Deak & Co., one of the world’s largest currency trading firms. Deak used Indian traders in Saigon to move money illegally in and out of the country. Clients like Furci would call Hong Kong to place an order. Six to eight hours later, a courier would deliver a heavy box filled with piasters, to their door.95 Eventually Furci and his partner were ratted out to Vietnamese police by a competitor with high-level military connections. Furci resigned himself to running a restaurant in Hong Kong.96

Faced with evidence of the enormity of the currency traffic, one senator remarked, “There obviously has been a great deal of laxness on the part of our intelligence community, our Treasury department, and also various banks.”97 The committee did not explore, at least in public, the most likely reason for that negligence: Like the ring of sergeants, the banks had friends in high places. Nicholas Deak, for example, had served as an intelligence officer in the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, ending up as head of operations in Indochina, where he helped the French regain their foothold. With covert government help, he founded Deak and Co. in 1947. In 1964, Time magazine called him “the James Bond of the world of money.” For more than three decades, his company “functioned as an unofficial arm of the intelligence agency and was a key asset in the execution of U.S. Cold War foreign policy,” according to Mark Ames and Alexander Zaitchik:

Because it carried out the foreign-currency transactions of private entities, Deak and Co. could keep track of who was spiriting money into and out of which countries.

In 1962, for example, Deak warned the CIA that China was planning to invade India after his company’s Hong Kong branch was swamped with Chinese orders for Indian rupees intended for advance soldiers. Deak’s offices were more than observation posts. His company played a crucial role in executing some of the United States’ most infamous covert ops. In 1953, CIA director Alan Dulles tasked Deak with smuggling $1 million into Iran through his offices in Lebanon and Switzerland. The cash went to the street thugs and opposition groups that helped overthrow Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, in favor of the U.S.-approved shah. Deak’s network also financed the CIA-assisted coups in Guatemala and the Congo. . . .

Sen. Frank Church inflicted the first hit on Deak’s public image in 1975. During the Idaho senator’s famous hearings into CIA black ops, it was revealed that Deak’s Hong Kong branch helped the agency funnel millions in Lockheed bribe money to a Japanese yakuza don, political power broker, and former “Class A” war criminal named Yoshio Kodama. . . . The House of Deak began its rapid collapse in 1983 when a federal informant accused the firm of laundering hundreds of millions of dollars in Colombian cartel cash.98

In 1976, the Washington Post reported that the CIA’s station in Saigon acquired nearly all of its local currency—millions of dollars worth—through black market transactions “while other U.S. agencies worked to stamp out corruption.” The Agency was able to double its money by evading the official exchange rate, stretching its budget. No doubt Deak and Co. was one of its principal agents for such transactions.99

|

In 1964, Time magazine called Nicholas Deak—featured on this gold coin—“the James Bond of the world of money.” Image source |

Hearings into currency and PX fraud, which began in 1969, riveted Washington and prompted President Nixon to establish a high-level inter-agency committee to address the problem. Authorities took steps to dramatically tighten access to PXs and to punish American soldiers or civilians caught violating currency regulations. But they could do little to discourage organized smuggling rings protected by senior Vietnamese officials. Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker complained to President Thieu in January 1970 that the cost to South Vietnam of black market currency transactions was “spectacular,” depriving the Saigon regime of “billions in revenue” while “weakening the piaster.” He warned that “unless there is some real progress in the attack on corruption I see serious trouble ahead—politically, economically, and . . . with the US.”100

Thieu promised to act, but nothing changed, and Washington did not force the issue with its difficult but well-entrenched client. A year and a half later, Time magazine blamed Thieu for surrounding himself with cronies “who are deeply involved in profiteering.” Organized theft was nearly as rampant as ever—with “as much as 50% of the oil, PX-bound appliances and other nonmilitary freight arriving at local ports . . . being ‘diverted.’” But, the story admitted, “it is probably fair to say that much of the high-level corruption in Viet Nam today can be traced directly to the complicity of Americans.”101

Conclusion

The French Socialist leader Léon Blum once expressed disappointment in “the exasperating individualism of the French people, their weakness for rackets–in a word, their display of ‘Balkan’ traits, . . . a corrupt state of mind spreading throughout every class of society, and despair because of it.”102 The American experience in Vietnam suggests there was nothing especially unique about the moral failings of the French people. On the contrary, one is struck by the similarities and continuity of their experiences. Like France, America had imperial aspirations, attempted in vain to win the “hearts and minds” of the people of Indochina, and failed to defeat an economically and technologically inferior—but more passionately committed—enemy. And like France, the United States allowed its war effort to descend into crime and profiteering, making the enteprise ever more costly, unpopular and ultimately unsustainable.

The pervasive corruption that characterized both the French and the American wars has been blamed by some on the Vietnamese. Historian William Allison called America’s failed attempts to resist these criminal currents “symbolic of the fundamental challenges the United States faced in a land peopled with a truly foreign set of cultural mores that matched poorly with American liberal democratic values.”103 Yet the desire to make a quick profit was hardly a poor match with America’s capitalist values. And in the case of currency profiteering, Vietnamese were rarely the criminal masterminds. Robert Parker, who chaired the Irregular Practices Committee set up by U.S. Ambassador Bunker to investigate black market activities, observed, “The Indian money changers are making huge profits, to be sure, but there would be no such profits without Americans or other free world civilians to write the checks or effect the bank transfers.”104

In both the French and American eras, corruption inevitably followed attempts to buy local allies in the face of rising nationalism and anti-colonialism. Whether for Bao Dai, Diem or Thieu, currency support and over-valued official exchange rates served to enrich local clients and augment the buying power of French and American nationals serving thousands of miles from home. Loyalty purchased at such a price, however, was fickle. The beneficiaries engaged in rampant capital flight, enriching themselves while exchanging funds for safekeeping abroad. The financial burden fell increasingly on taxpayers in France and later the United States. The electorate’s resentment burst after widespread disclosures of criminal profiteering put the lie to official denials and coverups. Public support for the war, already weakened by the specter of endless human sacrifices, eroded further as revelations of racketeering called into question the ultimate point of those sacrifices.

Within Indochina, the impact of corruption contributed to the toxic political environment. As Ambassador Bunker lectured President Thieu to no avail, corruption not only ruined the economy and sapped the country’s political strength, but also undercut the morale “of the military, of the government servants, of the people generally.” A corrupt society, he said, “is a weak society. It is a society in which everyone is for himself, no one is for the common good.” In short, it threatened everything Washington hoped to achieve.105

Bunker’s warning was prophetic. An official post-mortem on Vietnam by USAID concluded “there is little question that corruption . . . was a critical factor in the deterioration of national morale which led ultimately to defeat.”106 Certainly many other factors contributed as much or more to the defeat, but a postwar survey of Vietnamese military and civilian leaders supported the view that corruption had been “a fundamental ill that was largely responsible for the ultimate collapse of South Vietnam.” Significantly, they also observed that, “with Thieu involved in the corruption, there was no way of curbing it as long as the Americans supported him in office.”107 And, they might have added, there was no way of curbing it as long as the Americans, like the French before them, tolerated, enabled and profited from currency rackets and piaster profiteering.

Jonathan V. Marshall is an independent scholar living in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has published five books, including The Lebanese Connection: Corruption, Civil War and the International Drug Traffic (Stanford University Press, 2012) and To Have and Have Not: Southeast Asian Raw Materials and the Origins of the Pacific War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). His scholarly articles have appeared in Asia-Pacific Journal, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, Crime, Law and Social Change, Journal of American History, Journal of Intelligence History, Journal of Policy History, and Middle East Report. He thanks Eric Wilson, Mark Selden, and an anonymous reader for helpful comments on this article.

Recommended citation: Jonathan V. Marshall, “Dirty Wars: French and American Piaster Profiteering in Indochina, 1945-75,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 32, No. 2, August 11, 2014.

Notes

1 A. Schweitzer, “The French Colonialist Lobby in the 1930s: The Economic Foundations of Imperialism” (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1971); Stuart M. Persell, The French Colonial Lobby, 1889-1938 (Stanford: Hoover Press, 1983).

2 I was inspired to investigate this topic by Peter Dale Scott’s brief observation many years ago that “political corruption by the trafics became a major factor underlying France’s inability to disengage from Indochina” and “the apparatus and personnel of the trafic de piastres have continued with little abatement from the French through the American phases of the Vietnam War.” See Peter Dale Scott, “Opium and Empire: McCoy on Heroin in Southeast Asia,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 5 (September 1973), 52.

3 C.-J. Gignoux, “L’Affaire de la Piastre,” La Revue des deux mondes, August 1, 1953, 555.

4 Jonathan Marshall, “Jean Laurent and the Bank of Indochina Circle: Business Networks, Intelligence Operations and Political Intrigues in Wartime France,” Journal of Intelligence History 8 (Winter 2008), 43-74. One U.S. diplomat called the bank “all powerful,” while the Viet Minh denounced it as “the epitome of colonialism.” See Reed (Saigon) to Department of State, April 9, 1946, 800-Indochina file, Record Group (RG) 84, National Archives (NA); James O’Sullivan (Hanoi) to Department of State, September 14, 1946, Hanoi consulate files, RG 84, NA.

5 King Chen, Vietnam and China, 1938-1954 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 134-135, 138-139; Jean Sainteny, Histoire d’une paix manquée (Paris: Amiot-Dumont, 1953), 162-163; intelligence memorandum R-3190-CH-45 from Col. Harold Price and Lt. Richard Poole, JICA/China at Hanoi, October 30, 1945, re “French Indo-China: Economic-Financial Situation,” XL 26111, Records of the Office of Strategic Services, RG 226, NA.

6 Richard Ebelling, “The Great Chinese Inflation,” The Freeman, 54 (December 2004) at http://www.fee.org/the_freeman/detail/the-great-chinese-inflation.

7 James O’Sullivan (Hanoi) to Department of State, October 18, 1946, in Miscellaneous Confidential File, Records of the Consulate (Hanoi), RG 84, NA.

8 Ironically, the bank’s general manager, Jean Laurent, had warned against an even more extreme plan to retire 100 piaster notes, saying it could “set fire to the smallest Annamite village and turn against us the last of the undecided.” See Hugues Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil: Le Coût de la guerre d’Indochine, 1945-1954 (Paris: Comité Pour l’Histoire Économique et Financière de la France, 2002), 37.

9 Brig. Gen. P. E. Gallagher, “The 500$ Note Incident, French Indochina, November 1945,” Gallagher mss., Hoover Institution; Reginald Ungern to Gallagher, January 19, 1946, Gallagher mss.; O’Sullivan dispatch October 18, 1946, see note 7; Sainteny, Histoire d’une paix manquée, 161-162.

10 Chen, China and Vietnam, 135-138; Philippe Devillers, Histoire du Vietnam de 1940 à 1952, 3rd edition (Paris: Seuil, 1952), 213. Eventually the bank mended relations with the Nationalist Chinese, opening a branch in Kunming (Central Daily News [Kunming], April 22, 1947).

11 Stein Tonnesson, Vietnam 1946: How the War Began (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 106-145; George Armstrong Kelly, Lost Soldiers: The French Army and Empire in Crisis, 1947-1962 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1965), 44-45; Alexander Werth, France, 1940-1955 (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1956), 338.

12 Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 330.

13 Jacques Despuech, Le Traffic des piastres (Paris: La Table Ronde, 1974), 81.

14 Journalist Lucien Bodard noted, “The importance of the Exchange Office was not economic but political. It was an instrument of government. All the great secrets of Indochina at war, the Indochina of the palaces and the army staffs, led to these dusty, moth-eaten offices in the Rue Guynemer where sanction for the transfers was given or refused.” The Quicksand War (Boston: Little Brown, 1967), 86.

15 Gignoux, “L’Affaire de la Piastre,” 558-559; Despuech (1974), 214.

16 The same technique also serves to evade taxes, launder money, conceal illegal commissions, and engage in capital flight. John Zdanowicz, a finance professor at Florida International University, states that, “The use of international trade to move money, undetected, from one country to another is one of the oldest techniques used to circumvent government scrutiny.” See ”Trade-Based Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing,” Review of Law and Economics 5:2 (2009), 855-878. For a more general and theoretical discussion, see Pierre-Richard Agénor, “Parallel Currency Markets in Developing Countries: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications,” Essays in International Finance no. 188, Department of Economics, Princeton University, November 1992. Only in recent years have government agencies seriously come to grips with invoice fraud as a means of money laundering. For a notable report on this channel, see Financial Action Task Force [OECD], “Trade Based Money Laundering,” June 23, 2006.

17 Final Report of the National Assembly’s Commission to Investigate the Traffic in Indochinese Piasters, June 17, 1954 (hereafter Final Report), reprinted in Despuech (1974), 203-208.

18 David D. Duncan, “Indochina, All But Lost,” Life, August 3, 1953, 73-91. Although France officially abolished its colonial opium monopoly in 1946, the local administration continued selling opium through official “detoxification” clinics. By the late 1940s, opium sales accounted for anywhere from a fifth to a third of government revenues. See Consul Charles Reed II to Department of State, June 13, 1947, 851g14 Narcotics/6-1347, RG 59, NA; State Department to Paris embassy, June 7, 1948, 851g.114 Narcotics/6-748, RG 59, NA; George M. Abbott, Consul General Saigon, to Department of State, October 1, 1948, 851g.00/10-148, RG 59, NA; Acting Treasury Secretary William Sanders to Secretary of State, October 21, 1948, 851g.114 Narcotics/10-2148, RG 59, NA; “Indo-China,” Life, March 7, 1949, 99; “In French Indo-China it’s ‘Disintoxication,’” U.S. News and World Report, October 15, 1948, 69-70; William O. Walker III, Opium and Foreign Policy: The Anglo-American Search for Order in Asia, 1912-1954 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 177. For the memoirs of one opium buyer for the French administration, see André Roland, L’Action dans l’ombre (Paris: Editions du Dauphin, 1971). In 1945, François Bloch-Lainé, financial adviser to High Commissioner d’Argenlieu, said, “it would be absurd to dismantle the monopoly immediately to obey some puritanical injunctions that no one in the Far East actually follows.” Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 251.

19 Jacques Dalloz, The War in Indochina, 1945-54 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1990), 117.

20 In addition to those cited elsewhere, sources for this section include Col. Pierre Fourcaud, “L’Affaire des Généraux,” Historia, hors série 24, 1972, 140-152; Jacques Fauvet, Le IVe République (Paris: Fayard, 1959), 160-162; Kelly, Lost Soldiers, 65-69; Philip Williams, Wars, Plots and Scandals in Postwar France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970); P. L. Thyraud de Vosjoli, Lamia (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1970); Werth, France:1940-1955, 458-466; and Claude Guillaumin, “L’affaire des généraux,” in Les grandes énigmes de la IVe république, II, ed. Bernard Michal (Paris: Editions de Saint-Clair, 1967), 79-117.

21 Werth notes that under Pignon, there was “a spectacular development of corruption and of some of the more grandiose rackets: the racket in import and export licenses, the opium racket and, above all, the piastre racket—on which immense fortunes were made at the expense of the French Treasury, and which was alleged to provide a constant flow of money into certain Party funds in France itself.” Werth, France: 1940-1953, 459. Pignon was a fierce opponent of devaluing the piaster. Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 83.

22 Edward Francis Rice-Maximin, Accommodation and Resistance: the French Left, Indochina, and the Cold War (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1986), 87.

23 Paul Marcus, La République trahie: De l’affaire des généraux à l’affaire des fuites (Paris: le cherche midi, 2009), 33.

24 Georgette Elgey, La Republique des illusions, 1945-1951 (Paris: Fayard, 1965), 482-3.

25 Dalloz, The War in Indochina, 118-119.

26 de Vosjoli, Lamia, 203.

27 Final Report, 239.

28 Werth, France: 1940-1953, 468; Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 312; Rice-Maximin, Accommodation and Resistance, 89.

29 Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 86, 245-6, 308-311. U.S. officials were concerned that the cost of the colonial war was gravely weakening France while Western Europe was in peril: “Indochinese expenditures impose such a burden on the French public finances as to constitute an important obstacle to the success of the whole French recovery and stabilization effort. The 167 billion francs spent in Indochina in 1949 is not only equivalent to over two-thirds of the total direct American aid to France for 1949-50, but some ten billion francs greater than the estimated French budgetary deficit for the year. . . . It is clear that the struggle to create conditions necessary for the continued growth of a non-Communist Viet Government in Indochina, to which the French are apparently irrevocably committed, constitutes for the moment a major obstacle in the path of French financial stabilization and economic progress, with all that that implies for the European Recovery Program as a whole.” See Paris embassy to Department of State, December 22, 1949, 851g.00/12-2249, RG 59, NA.

30 Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 180.

31 Based on an exchange rate of 350 francs to the dollar. 2014 dollars calculated from http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm (accessed April 16, 2014).

32 Final Report, 176, 188. On the remarkable lack of legal sanctions against fraudulent transfers, see Saigon embassy to Department of State, July 28, 1953, Confidential Security Information, 851G,131/7-2853, RG 59, NA.

33 Quoted in Marcus, La République trahie, 81-83.

34 Le Monde, November 20, 1952; Jacques Despuech, Le Traffic des piastres (Paris: Deux Rives, 1953).

35 More conservatively, Tertrais estimates the total sum of fraudulent transfers at between 130 billion and 200 billion francs, “around a year of Treasury disbursements to Indochina in the last years of the war.” Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 321.

36 Despuech (1953), 62-64; Despuech (1974), 73.

37 Despuech (1953), 83; Final Report, 200, 245; c.f. Mag Bodard, L’Indochine, c’est aussi comme ça (Paris: Gallimard, 1954), 142-143; Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade (Brooklyn: Lawrence Hill Books, 1991), 157. The director of SDECE in Saigon, Col. Belleux, told an American diplomat in 1951 that although it was “exceptionally difficult to get proof regarding illegal piaster transactions,” he “expected within several months to be able to bring about the expulsion from Indochina of several of the leading traffickers, among whom he included Mr. Franchini and Mr. Adriani, Director of the Croix du Sud night club but also the director of a large gambling, narcotics, and white slavery organization.” Evidently the Corsican mafia proved more resilient than he expected. See Saigon embassy to Department of State, April 6, 1951, 851G.131/4-651, RG 59, NA.

38 Despuech (1953), 104-6. American diplomats regarded Diethelm’s administration of Indochina’s finances in the early 1930s as highly corrupt, noting that his officials regularly allowed illegal smuggling of opium from Yunnan into Indochina, undercutting the official opium monopoly. See W. Evertt Scotten report, January 12, 1933, 8516.114 Narcotics/53, RG 59, NA.

39 Frédéric Turpin, De Gaulle, les gaullistes et l’Indochine, 1940-1956 (Paris: Les Indes Savantes, 2005), 484, 389-90; Frédéric Turpin, André Diethem (1896-1854): De Georges Mandel à Charles de Gaulle (Paris: Les Indes Savantes, 2004), 236-242.

40 Despuech (1953) 35-37. Another leading if much less credible critic of the Bank of Indochina at the time was Arthur Laurent, author of La Banque de l’Indochine et la piastre (Paris: Deux Rives, 1954). Laurent was convicted of using fraudulent documentation to obtain financing from the bank for his rum importation business.

41 Marc Meuleau, Des Pionniers en Extrême-Orient: Histoire de la Banque de l’Indochine, 1875-1975 (Paris: Fayard, 1990), 488-500. The parliamentary commission noted that the Bank of Indochina “always opposed devaluation” and added, “It is undeniable that the Banque de l’Indochine sought to take out of Indochina the maximum capital and thus it could not but benefit from the disparity in value of the piaster and franc.” The commission concluded that the bank deserved “a very severe inquiry” into its affairs and “very serious oversight.” Final Report, 228-233.

42 Saigon embassy to Department of State, April 6, 1951, 851G.131/4-651, RG 59, NA. The ambassador noted the view of the embassy, however, that the piaster traffic contributed only a small percentage of funds available to the Viet Minh. See also his dispatch to the Department of State, August 30, 1952, 851G.131/8-3052 (Secret Security Information), RG 59, NA. For a more alarmist view of how the Viet Minh and Communist China allegedly profited from the traffic, see Despuech (1974), 119-154; Frederik Logevall, Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam (New York: Random House, 2012), 348; and Victoria Pohle and William J. Mazzocco, Office of Vietnam Affairs, U.S. Agency for International Development, “Viet-Minh Economic Warfare and the Traffic of Piasters” (no date, probably 1960s).

43 Seymour Topping, Journey Between Two Chinas (Harper & Row, 1972), 128. The head of the French Sûreté admitted paying agents and “prominent personalities in Saigon” with profits from the piaster traffic, and accused his rivals in SDECE of funding its operations through the illegal sale of import licenses. At least one SDECE agent who later became notorious as a heroin trafficker, André Labay, was said to have engaged in piaster trafficking. See Pierre Galante and Louis Sapin, The Marseilles Connection (London: W.H. Allen & Co., 1979), 224.

44 With regard to the missionaries, an American diplomat in Saigon observed that “whereas the Lord once drove the money changers from the temple, it now seemed that in order to do the Lord’s work it was necessary to bring them back again.” Robert McClintock, Chargé d’Affaires, to Department of State, April 27, 1954, 861G.131/4-2754 (Secret file), RG 59, NA.

45 Report of C. Tyler Wood, Associate Deputy Director, Mutual Security Agency, “Relative to the Exchange Rate in the Associated States of Indochina,” January 7, 1953, 851G.131/1-753 (Top Secret), RG 59, NA. See also Bonsal memorandum to Allison, “Possibility of Securing a Diplomatic Exchange Rate in Indochina,” March 25, 1953, 851G.131/3-2553 (Secret Security Information), RG 59, NA.

46 State Department to Saigon embassy, August 15, 1952, 851G.131/8-1552, RG 59, NA; Saigon embassy to Department of State, August 20, 1952, 851G.131/8-2052 (Secret Security Information, Personal and Eyes Only Allison and Bonsal), RG 59, NA.

47 Department of State to Saigon embassy, September 12, 1952, 851G.131/9-1252, RG 59, NA.

48 Debate of December 4, 1952, in Journal Officiel de la République Française, Debats Parlementaires Assemblée Nationale, December 5, 1952.

49 Quoted in Donald J. McGrew, assistant Treasury representative, dispatch 1726 for State, Treasury and Mutual Security Agency, February 16, 1953, 851G.13/2-1653, RG 59, NA.

50 Saigon embassy to Department of State, March 12, 1953, in U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States [FRUS], 1952-1954, Indochina, XIII, 407.

51 Saigon embassy to Department of State, March 8, 1953, 851G.131/3-853, RG 59, NA.

52 Memorandum by E. Donegan, March 2, in Saigon embassy to Department of State, March 17, 1953 851G.131/3-1753, RG 59, NA.

53 Report of C. Tyler Wood, Associate Deputy Director, Mutual Security Agency, Relative to the Exchange Rate in the Associated States of Indochina, January 7, 1953, 851G.131/1-753 (Top Secret), RG 59, NA.

54 Department of State circular airgram 523, June 4, 1953, 851.131/6-453 (secret), RG 59, NA.

55 Ambassador Douglas Dillon, Paris embassy, to Department of State, May 15, 1953, 851G.131/5-1553, RG 59, NA.

56 Evidently the devaluation did not surprise everyone. As the Saigon embassy reported, “there seem to have been a few individuals who had enough advance notice so that they had made the necessary transfers before devaluation. Most of these individuals seemed to have excellent trading or political connections in Paris. . . . One local French observer considered that leaks in the announcement did occur, because it is his understanding that Dreyfus and Company, a large French export-import firm, made considerable commodity purchases both locally and externally on Friday and Saturday before devaluation.” Saigon embassy to Department of State, June 4, 1953, 851G.131/6-453, RG 59 NA.

57 André Valls, quoted in Tertrais, La piastre et le fusil, 302.

58 Saigon embassy to Department of State, May 11, 1953, 851G.131/5-1153, RG 59, NA. Another report claimed, however, that Tam was “secretly elated” by the devaluation since it gave him license to act more independently of France. See Charge at Saigon (McClintock) to Department of State, May 21, 1953, #2273, in FRUS, 1952-1954. Indochina, XIII, 577.

59 Chargé (McClintock) to Department of State, May 13, 1953, #2190. FRUS, 1952-1954. Indochina, XIII, 562.

60 Saigon embassy to Department of State, June 4, 1953, 851G.131/6-453, RG 59 NA.

61 Saigon embassy to Department of State, May 12, 1953, 851G.131/5-1253, RG 59 NA.

62 Paris embassy to Department of State, September 16, 1953, 851G.131/9-1653, RG 59 NA.

63 Alain Ruscio, Les communistes français et la guerre d’Indochine, 1944-1954 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1985), 382.

65 Testimony of George Staples, General Accounting Office, in U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Government Operations, United States Aid Operations in Laos: Hearings, 86th Congress, 1st Session (Washington: USGPO, 1959), 259.

66 Seth Jacobs, The Universe Unraveling: American Foreign Policy in Cold War Laos (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2012), 65-66; cf. Martin Goldstein, American Policy Toward Laos (Cranbury, N.J.: Associated University Presses, 1973), 179-200; Denis Warner, The Last Confucian (New York: Macmillan Company, 1963), 203; William Conrad Gibbons, The US Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships, Part 1: 1945-1960 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 316-317.

67 See terms of the Laotian government’s contract with Universal Construction Co. Ltd., whose performance was deemed fraudulent by an auditor for the International Cooperation Administration, in United States Aid Operations in Laos, 365. One of the two main principals of Universal Construction was Willis Bird, whose connections to the CIA and drug trafficking are discussed in Jonathan Marshall, “Cooking the Books: The Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the China Lobby and Cold War Propaganda, 1950-1962,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 37, No. 1, September 14, 2013.

68 Quoted in Jacobs, The Universe Unraveling, 114.

69 Warner, The Last Confucian, 203-4.

70 Memorandum of a Conversation, Department of State, January 15, 1958, in FRUS, 1958-1960. XVI: East Asia-Pacific Region; Cambodia; Laos, 420-422.

71 Vientiane embassy to Department of State, May 19, 1958, FRUS, 1958-1960. XVI: East Asia-Pacific Region; Cambodia; Laos, 443.

72 Ibid., 455n7; United States Aid Operations in Laos, 8, 48.

73 United States, Congress, Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee to Investigate Problems Connected with Refugees and Escapees, North Vietnam and Laos, Relief and Rehabilitation of War Victims in Indochina, hearings, 93rd Congress, 1st session (Washington: USGPO 1973), 119.

75 Quoted in George McT. Kahin, Intervention: How America Became Involved in Vietnam (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986), 86-87. Rutherford Poats, assistant administrator for the Far East, USAID, called the CIP “our primary weapon in the battle to prevent runaway inflation which could cause a breakdown in Vietnamese support of the war effort.” See United States, Congress, Senate, Committee on Government Operations, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Improper Practices, Commodity Import Program, U.S. Foreign Aid, Vietnam: Hearings. Ninetieth Congress, First Session (Washington: USGPO, 1967), 6.

76 Kahin, Intervention, 87. See also Douglas C. Dacy, Foreign Aid, War, and Economic Development: South Vietnam, 1955-1975 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986, 33, 153.

77 Hillaire du Berrier, Background to Betrayal: The Tragedy of Vietnam (Belmont, Mass.: Western Island, 1965), 197.

78 Memorandum of Conversation, July 16, 1965; and Saigon embassy to Department of State, July 17, 1965, in FRUS, 1964–1968 Volume III, Vietnam, June–December 1965 (http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v03/d60 accessed April 15, 2014).

79 James Hamilton-Patterson, The Greedy War: How Profiteers Made Billions Out of Your Blood, Sweat and Taxes in Vietnam (New York: David McKay Co., 1971), 68-70, 123-124.

80 William Allison, “War for Sale: The Black Market, Currency Manipulation and Corruption in the American War in Vietnam,” War & Society, 21 (October 2003), 148-9.

81 Robert Parker testimony, in United States Senate, Committee on Government Operations, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Fraud and Corruption in Management of Military Club Systems: Illegal Currency Manipulations Affecting South Vietnam. Hearings. 9/1. (Washington: USGPO, 1970) [hereafter SPSI hearings], 536, 545; Hamilton-Patterson, The Greedy War, 89-90. These Indian money changers were Muslim, unlike the traditional Hindu Indian money lenders often known collectively as “Chettys” or “Chettiars.”

82 Hamilton-Patterson, The Greedy War, 89-90, 122-124.

83 Ibid, 188-90.

84 Rufus Phillips, who ran the Office of Rural Affairs for the U.S. aid mission in Vietnam in the mid-1960s, exposed the blatant diversion of goods from American PXs to the Saigon black market in a memo to Edwin Lansdale, who said he forwarded it to Ambassador Lodge and General Westmoreland. Phillips recalls that when he got back to Washington, “I asked Lansdale by phone about any action resulting from my corruption memo. ‘Nothing significant,’ he said. When I checked about a year later, during my next visit, I heard the black market depot had been moved but was still in operation and that corruption in general had gotten worse. . . . I found it amazing that the issue was never directly addressed by General Westmoreland or Lodge. How could this be allowed to continue, when Americans and Vietnamese were dying in combat? How did we expect the Vietnamese to be honest when Americans were either fomenting or allowing such corruption and our highest officials appeared unconcerned? It was hard to take and hard to blame on the Vietnamese.” Why Vietnam Matters: An Eyewitness Account of Lessons Not Learned (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2008), 273-4.