Introductory Note: This is the final article in a three part series on the relationship of D.T. Suzuki and other Zen figures in wartime Japan to Count Karlfried Dürckheim and other Nazis. Part I of this series, “D.T. Suzuki, Zen and the Nazis” is available here. Part II, “The Formation and Principles of Count Dürckheim’s Nazi Worldview and his interpretation of Japanese Spirit and Zen” is available here. Readers who have not yet done so are urged to read at least Part II of this series that provides crucial background information for understanding Part III.

Introduction

By the late 1930s Japan was well on the way to becoming a totalitarian society. True, in Japan there was no charismatic dictator like Hitler or Mussolini, but there was nevertheless a powerful “divine presence,” i.e., Emperor Hirohito. Although seldom seen and never heard, he occasionally issued imperial edicts, serving to validate the actions of those political and military figures claiming to act on his behalf. At least in theory, such validation was absolute and leftwing challenges to government policies, whether on the part of Communists, socialists or merely liberals, were mercilessly suppressed. For example, between 1928 and 1937 some 60,000 people were arrested under suspicion of harboring “dangerous thoughts,” i.e., anything that could conceivably undermine Japan’s colonial expansion abroad and repressive domestic policies at home. Added to this was the fact that Japan had begun its full-scale invasion of China on July 7, 1937.

Japan’s relationship with Germany was in flux according to the changing political interests of both countries.1 Because of negative international reactions to the Anti-Comintern pact of November 1936, resistance against it increased in Japan soon after it was made, and the Japanese froze their policy of closer ties. However, in 1938 it became clear to Japan that the war against China would last longer than expected. Thus, Japanese interest in a military alliance with Germany and Italy reemerged. On the German side, Joachim von Ribbentrop had become Foreign Minister in February 1938, and as he had long been a proponent of closer ties with Japan, negotiations between the two countries resumed in the summer of 1938.

|

Joachim von Ribbentrop |

Count Karlfried Dürckheim´s first Japan trip was probably connected with the beginning of this thaw in German-Japanese relations. The birth of “total war” in the wake of World War I and even earlier had demonstrated that victory could not be achieved without the strong support and engagement of civilian populations, one aspect of which was not simply knowledge of potential adversaries but of one’s allies as well. This meant enhanced cultural relations and mutual understanding between the citizens of allied nations.

It was under these circumstances that Dürckheim undertook what was portrayed as an education-related mission to Japan, a mission that would impact on him profoundly for the remainder of his life. This was not the first such mission Dürckheim had undertaken on behalf of Foreign Minister Von Ribbentrop and Education Minister Bernhard Rust, for he had previously made somewhat similar trips to other countries, including South Africa and Britain. Dürckheim’s trip to South Africa took place from May thru October 1934 on behalf of Rust. He conducted research on the cultural, political and educational situation of Germans in South Africa while at the same time promoting the new regime.

During his work in Ribbentrop’s office from 1935 to 1937, Dürckheim was a frequent visitor to Britain, around 20 times altogether. His task was to gather information about the image of National Socialism in Britain while at the same time promoting the “new Germany.” Toward this end, he met such notables as King Edward VII and Winston Churchill and arranged a meeting between Hitler and Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Evening Standard. This was part of Hitler’s ultimately unsuccessful plan to form a military alliance with Britain directed against the Soviet Union. Dürckheim’s work officially ended on December 31, 1937.

Dürckheim‘s First Visit to Japan

Dürckheim began his journey to Japan on June 7, 1938 and did not return to Germany until early 1939. According to his biographer, Gerhard Wehr, Dürckheim initially received a research assignment from the German Ministry of Education that consisted of two tasks: first, to describe the development of Japanese national education including the so-called social question,2 and second, to investigate the possibility of using cultural activities to promote Germany’s political aims both within Japan and those areas of Asia under Japanese influence.3 Dürckheim arrived by boat and travelled extensively within Japan as well as undertaking trips to Korea, Manchukuo (Japan’s puppet state in Manchuria) and northern China. During his travels Dürckheim remained in close contact with the local NSDAP (Nazi) offices and the Japan-based division of the National Socialist Teachers Association.

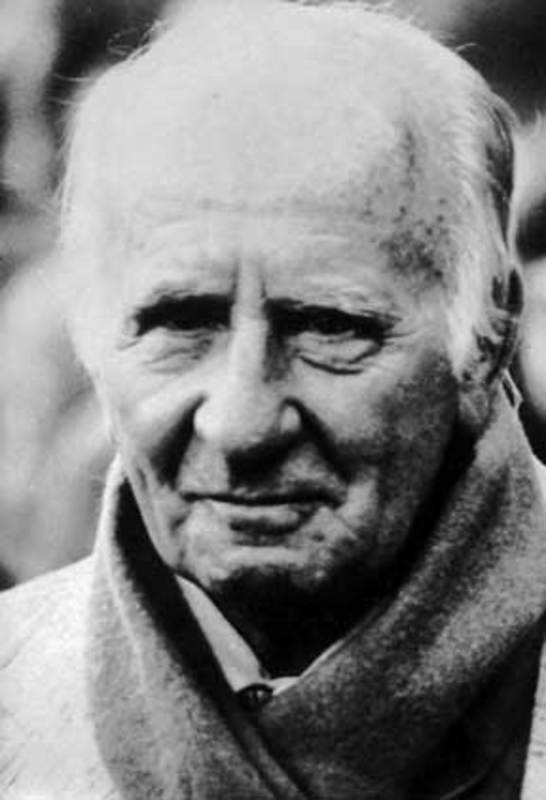

|

Count Karlfried Dürckheim |

Dürckheim Meets D.T. Suzuki

Dürckheim described his arrival in Japan as follows:

I was sent there in 1938 with a particular mission that I had chosen: to study the spiritual background of Japanese education. As soon as I arrived at the embassy, an old man came to greet me. I did not know him. “Suzuki,” he stated. He was the famous Suzuki who was here to meet a certain Mister Dürckheim arriving from Germany to undertake certain studies.

Suzuki is one of the greatest contemporary Zen Masters. I questioned him immediately on the different stages of Zen. He named the first two, and I added the next three. Then he exclaimed: “Where did you learn this?” “In the teaching of Meister Eckhart!” “I must read him again…” (though he knew him well already). . . . It is under these circumstances that I discovered Zen. I would see Suzuki from time to time.4

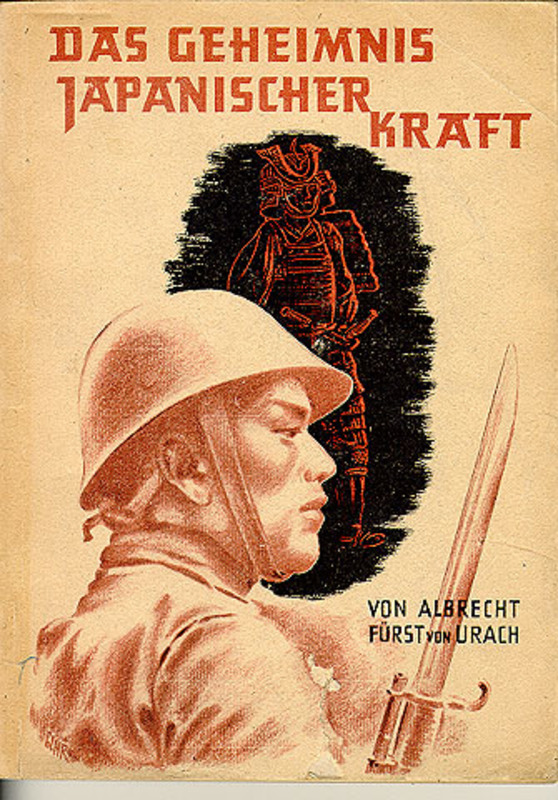

Although the exact sequence of events leading up to their meeting is unknown, a few points can be surmised. First, while Dürckheim states he had been sent to Japan on an educational mission, specifically to study “the spiritual foundations of Japanese education,”5 it should be understood that within the context of Nazi ideology, education referred not only to formal academic, classroom learning but, more importantly, to any form of “spiritual training/discipline” that produced loyal citizens ready to sacrifice themselves for the fatherland. Given this, it is unsurprising that following Dürckheim’s return to Germany in 1939 the key article he wrote was entitled “The Secret of Japanese Power” (Geheimnis der Japanisher Kraft).

Additionally, it should come as no surprise to read that Dürckheim was clearly aware of, and interested in, Suzuki’s new book. Wehr states: “In records from his first visit [to Japan] Dürckheim occasionally mentions Zen including, among others, D. T. Suzuki’s recently published book, Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. In this connection, Dürckheim comments: ‘Zen is above all a religion of will and willpower; it is profoundly averse to intellectual philosophy and discursive thought, relying, instead, on intuition as the direct and immediate path to truth.'”6

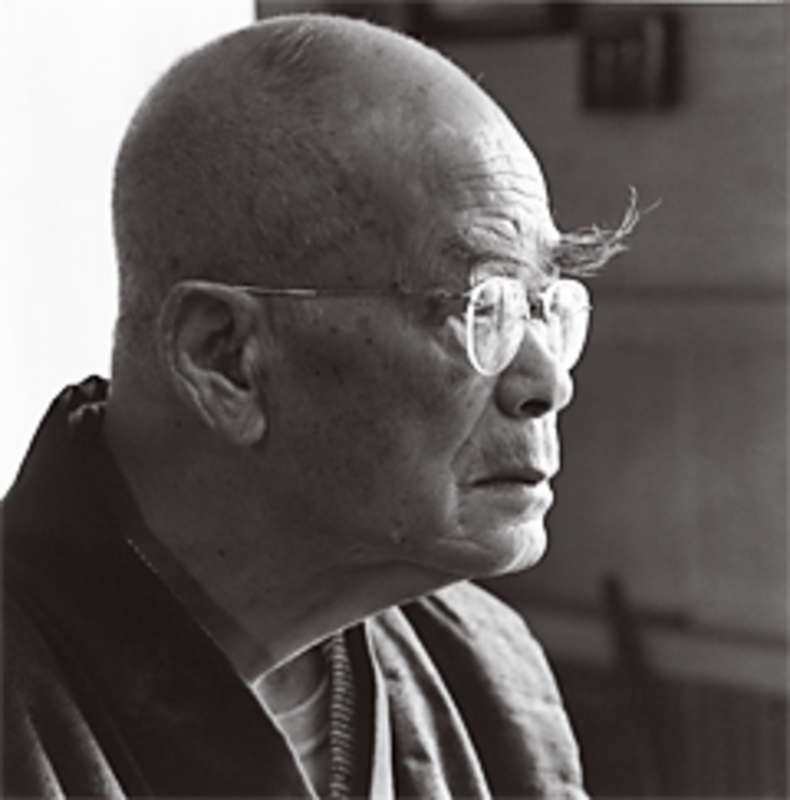

|

D.T. Suzuki |

In claiming this is it possible that Dürckheim had misunderstood the import of Suzuki’s writings? That is to say, had he in fact begun what might be called the ‘Nazification’ of Zen, i.e., twisting it to fit the ideology of National Socialism. In fact he had not, for in his 1938 book, Suzuki wrote: “Good fighters are generally ascetics or stoics, which means to have an iron will. When needed Zen supplies them with this.”7 Suzuki futher explained: “From the philosophical point of view, Zen upholds intuition against intellection, for intuition is the more direct way of reaching the Truth…Besides its direct menthod of reaching final faith, Zen is a religion of will-power, and will-power is what is urgently needed by the warriors, though it ought to be enlightened by intuition.”8

In light of these quotes, and many others like them, whatever other faults the wartime Dürckheim may have had, misunderstanding Suzuki’s explication of Zen was not one of them.

And, significantly, Suzuki was not content in his book to simply link Zen as a religion of will to Japanese medieval warriors. He was equally intent to show that the same self-sacrificial, death-embracing spirit of the samurai had become the modern martial spirit of the Japanese people as a whole:

The Japanese may not have any specific philosophy of life, but they have decidedly one of death which may sometimes appear to be that of recklessness. The spirit of the samurai deeply breathing Zen into itself propagated its philosophy even among the masses. The latter, even when they are not particularly trained in the way of the warrior, have imbibed his spirit and are ready to sacrifice their lives for any cause they think worthy. This has repeatedly been proved in the wars Japan has so far had to go through for one reason or another. A foreign writer on Japanese Buddhism aptly remarks that Zen is the Japanese character.9

Given these words, Dürckheim could not fail to have been interested in learning more about a Zen tradition that had allegedly instilled death-embracing values into the entire Japanese people. Hitler himself is recorded as having lamented, “You see, it’s been our misfortune to have the wrong religion. Why didn’t we have the religion of the Japanese, who regard sacrifice for the Fatherland as the highest good?”10 Thus Dürckheim’s mission may best be understood as unlocking the secret of the Japanese people’s power as manifested in the Zen-Bushidō ideology Suzuki promoted. No doubt, his superiors were deeply interested in duplicating, within the context of a German völkisch faith, this same spirit of unquestioning sacrifice for the Fatherland.

It is unlikely that Dürckheim had read Suzuki’s book prior to his arrival. Written in English, the Eastern Buddhist Society of Ōtani College didn’t publish it in Japan until May 1938. Suzuki reports that he first received copies of his book on May 20, 1938.11 This suggests that it was Embassy personnel, knowing of Dürckheim’s interests and Suzuki’s reputation, who requested Suzuki’s presence. Yet another possibility is that Dürckheim had heard about Suzuki during his frequent trips to Britain, since much of the material in Suzuki’s 1938 book consisted of lectures first delivered in Britain in 1936.

It is noteworthy that the first conversation between the two men centered on Meister Eckhart, the thirteenth century German theologian and mystic. On the surface this exchange seems totally innocuous, the very antithesis of Nazism. Yet, as discussed in Part II, Meister Eckhart was the embodiment of one major current in Nazi spirituality. That is to say, within German völkisch religious thought Eckhart represented the very essence of a truly Germanic faith.

|

Meister Eckhart |

Meister Eckhart’s reception in Germany had undergone many changes over time, with Eckhart becoming linked to German nationalism by the early 19th century as a result of Napoleon’s occupation of large parts of Germany. Many romanticists and adherents of German idealism regarded Eckhart as a uniquely German mystic and admired him for having written in German instead of Latin and daring to oppose the Latin speaking world of scholasticism and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

In the 20th century, National Socialism – or at least some leading National Socialists – appropriated Eckhart as an early exponent of a specific Germanic Weltanschauung. In particular, Alfred Rosenberg regarded Eckhart as the German mystic who had anticipated his own ideology and thus represented a key figure in Germanic cultural history. As a result, Rosenberg included a long chapter on Eckhart, entitled “Mysticism and Action,” in his book The Myth of the Twentieth Century.

|

Alfred Rosenberg |

Rosenberg was one of the Nazi’s chief ideologists and The Myth of the Twentieth Century was second in importance only to Hitler’s Mein Kampf. By 1944 more than a million copies had been sold. Rosenberg was attracted to Eckhart as one of the earliest exponents of the idea of “will” as supreme:

Reason perceives all things, but it is the will, Eckhart comments, which can do all things. Thus where reason can go no further, the superior will flies upward into the light and into the power of faith. Then the will wishes to be above all perception. That is its highest achievement.12

Suzuki would no doubt have readily agreed with these sentiments, for, as we have already seen, he, too, placed great emphasis on will, identifying it as the very essence of Zen.

Rosenberg also included this almost Zen-like description of “Nordic Germanic man”:

Nordic Germanic man is the antipode of both directions, grasping for both poles of our existence, combining mysticism and a life of action, being borne up by a dynamic vital feeling, being uplifted by the belief in the free creative will and the noble soul. Meister Eckhart wished to become one with himself. This is certainly our own ultimate desire.13

This said, the fact that there were similarities between Rosenberg’s description of Eckhart and Suzuki’s descriptions of Zen by no means demonstrates that Suzuki’s interest in Eckhart was identical with Rosenberg’s racist or fascist interpretation. In fact, Suzuki’s interest in Eckhart can be traced back to his interest in Theosophy in the 1920s.

Nevertheless, there is a clear and compelling parallel in the totalitarian nature of völkisch Nazi thought as represented by Rosenberg, as well as Dürckheim, and Suzuki’s own thinking. As pointed out in Part II, one of the key components of Nazi thought was that “individualism” was an enemy that had to be overcome in order for the “parts” (i.e., a country’s citizens) to be ever willing to sacrifice themselves for the Volk, i.e., the “whole,” as ordered by the state. Rudolph Hess, Hitler’s Deputy Führer, not only recognized the importance of this struggle but also admitted that the Japanese were ahead of the Nazis in this respect. Hess wrote:

We, too, [like the Japanese] are battling to destroy individualism. We are struggling for a new Germany based on the new idea of totalitarianism. In Japan this way of thinking comes naturally to the people.14

Just how “naturally” (or even whether) the Japanese people rejected individualism and embraced totalitarianism is open to debate. Yet, we find Suzuki adopting an analogous position beginning with the publication of his very first book in 1896, i.e., Shin Shūkyō-ron (A Treatise on the New [Meaning of] Religion). Suzuki wrote:

At the time of the commencement of hostilities with a foreign country, then marines fight on the sea and soldiers fight in the fields, swords flashing and cannon-smoke belching, moving this way and that. In so doing, our soldiers regard their own lives as being as light as goose feathers while their devotion to duty is as heavy as Mt. Tai in China. Should they fall on the battlefield they have no regrets. This is what is called “religion in a national emergency.”15

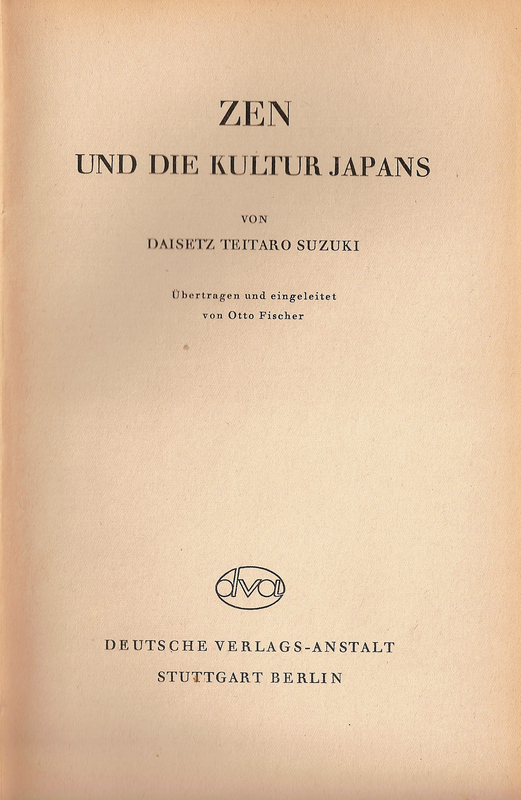

|

|

Suzuki was only twenty-six years old when he wrote these lines, i.e., long before the emergence of the Nazis. Yet, he anticipated the Nazi’s demand that in wartime all citizens must discard attachment to their individual well-being and be ever ready to sacrifice themselves for the state, regarding their own lives “as light as goose feathers.” During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, Suzuki exhorted Japanese soldiers as follows: “Let us then shuffle off this mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates. . . . Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.”16 Given these sentiments there clearly was no need for the Nazis to inculcate völkisch values, emphasizing self-sacrifice for the state, into Suzuki’s thought, for they had long been present.

In any event, the content of the initial conversation between Suzuki and Dürckheim does suggest why, from the outset, these two men found they shared so much in common. For his part, like “Nordic man” in the preceding quotation, Suzuki frequently equated Zen with the Japanese character.17 In other words, within one of the two major strands of Nazi religiosity, Dürckheim would perhaps have understood, and welcomed, Suzuki as a völkisch proponent of a religion, i.e., Zen, dedicated to, and shaped by, the Japanese Volk. This may well explain what initially drew the two men together and led to their ongoing relationship.

It should also be noted that Suzuki was not the first to recognize affinities between Eckhart and Buddhism. In the 19th century the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer had postulated this connection. He wrote:

If we turn from the forms, produced by external circumstances, and go to the root of things, we shall find that [Buddha] Shākyamuni and Meister Eckhart teach the same thing; only that the former dared to express his ideas plainly and positively, whereas Eckhart is obliged to clothe them in the garment of the Christian myth, and to adapt his expressions thereto.18

As for Dürckheim, his interest in Eckhart, as noted in Part II, can be traced back to the 1920s when he began to practice meditation together with his friend Ferdinand Weinhandl, the Austrian philosopher who later became a professor in Kiel and another strong proponent of National Socialism. Additionally, the Swiss psychologist C. G. Jung identified Eckhart as the most important thinker of his time.

Suzuki’s View of Nazi Germany

There is one vital question that warrants our attention, i.e., why had Suzuki accepted an invitation to come to a German Embassy so firmly under Nazi control? In the context of the times, this may not seem so surprising, but it is in fact a very surprising turn of events. Very surprising, that is, if one believes the testimony of Satō Gemmyō Taira, a Shin (True Pure Land) Buddhist priest who, readers of Part I of this article will recall, identifies himself as one of Suzuki’s disciples in the postwar period.

Satō claims:

Although Suzuki recognized that the Nazis had, in 1936, brought stability to Germany and although he was impressed by their youth activities (though not by the militaristic tone of these activities), he clearly had little regard for the Nazi leader, disapproved of their violent attitudes, and opposed the policies espoused by the party. His distaste for totalitarianism of any kind is unmistakable.19

If, as Satō asserts, Suzuki “opposed the policies espoused by the [Nazi] party,” etc. why would he have agreed to meet a Nazi researcher like Dürckheim on his arrival in Japan? And why would he subsequently have continued to meet him “from time to time”? Still further, why would the German Embassy have invited a known critic of the Nazis, someone whom Satō claims had publicly expressed his anti-Nazi views in October 1936, to meet a visiting Nazi researcher less than two years later? While these questions may seem unrelated to Dürckheim’s wartime activities in Japan, they do point to a striking parallel between the two men in the postwar period, a parallel that will become apparent below.

First, however, it should be noted that there is an alternate narrative that readily explains Suzuki’s willingness to assist a Nazi-affiliated researcher like Dürckheim. This narrative begins by noting that in his 1938 book, Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture, Suzuki wrote:

Zen has no special doctrine or philosophy with a set of concepts and intellectual formulas, except that it tries to release one from the bondage of birth and death and this by means of certain intuitive modes of understanding peculiar to itself. It is, therefore, extremely flexible to adapt itself almost to any philosophy and moral doctrine as long as its intuitive teaching is not interfered with.

It may be found wedded to anarchism or fascism, communism or democracy, atheism or idealism, or any political and economical dogmatism. It is, however, generally animated with a certain revolutionary spirit, and when things come to a deadlock which is the case when we are overloaded with conventionalisms, formalism, and other cognate isms, Zen asserts itself and proves to be a destructive force.20

Given that Suzuki, at least in 1938, claimed that Zen could be wedded to almost any political ideology, fascism included, he would have had no reason for refusing to meet Dürckheim at the German Embassy. As Part I of this article revealed, Suzuki’s staunch defender, Satō Gemmyō Taira, was willing to go so far as to fabricate part of his translation of Suzuki’s October 1936 newspaper description of the Nazis in order to make it appear his master was critical of this movement. This bears repeating because a similar phenomenon occurred on the part of those who were close to Dürckheim, including his family members.

If in Dürckheim’s case it was impossible to deny outright his Nazi connection, then the least his admirers could do was minimize the significance of that connection, for example, by describing his role in wartime Japan as that of a “Kulturdiplomat” (cultural diplomat). This title suggests that Dürckheim did nothing more than engage in “cultural activities” during his nearly eight-year residence in Japan. However, as this article makes clear, Dürckheim was in fact an indefatigable propagandist for the Nazis, anything but a mere cultural envoy. This point will be touched upon again below.

In part, this attempt to disguise Dürckheim’s actions as being cultural in nature can be explained by the fact that for the Nazis “culture,” like “education,” was an all-embracing concept subsumed into the overall struggle for a totalitarian society and state. Thus, the primary focus of Dürckheim’s “cultural activities,” including his interest in Zen, was his mission to promote the cultural, educational and political policies of the Third Reich in Japan as a part of the overall struggle to ensure the triumph of National Socialism.

As for the frequency of Suzuki’s meetings with Dürckheim during his first visit to Japan we know relatively little. However, Suzuki did include the following entries in his English language diary: (January 16, 1939), “Special delivery to Durkheim (sic), at German Embassy”;21 (January 17, 1939), Telegram from Dürkheim”;22 (January 18, 1939), “Went to Tokyo soon after breakfast. Called on Graf. [Count] Durkheim at German Embassy, met Ambassador [Eugen] Otto [Ott], and Dr. [space left blank] of German-Japanese Institute. Lunch with them at New Grand [Hotel].”23 It is likely that this flurry of activity in early 1939 was connected to Dürkheim’s impending return to Germany. If so, Dürkheim’s luncheon invitation may well have been by way of thanking Suzuki for the latter’s assistance during his stay.

Suzuki’s assistance appears to have extended to aiding Dürckheim indirectly during a sightseeing visit he made to Kyoto on November 20-24, 1938. Wehr informs us that while in Kyoto Dürckheim met ikebana master Adashi and participated in a tea ceremony. In describing his visit Dürckheim wrote in his diary: “My loyal companion, Mr. Yanasigawa, was – what a happy coincidence! – Suzuki’s secretary.”24

Dürckheim’s Second Visit to Japan

Dürckheim returned to Japan in January 1940 and remained there throughout the war. It was during this time that his most important work for the Nazis was undertaken. This time Dürckheim travelled to Japan by train through Russia, taking advantage of the new, and once unthinkable, non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. It was, however, this very treaty that had produced a crisis in Germany’s relationship with Japan. That is to say, the promising negotiations of 1938 between the two countries had led to nothing, mostly because of Japan’s hesitant attitude. As a result, Germany changed its plans and on August 23, 1939 Foreign Minister Ribbentrop signed a “Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” thereby allying itself with Japan’s archenemy. This ruptured the Anti-Comintern pact, and the relationship between the two countries hit rock bottom.

|

Signing of the Nazi-Soviet Non-aggression Pact |

Interestingly, Dürckheim appears to have had advance knowledge of this development. That is to say, in his 1992 book, Der Weg ist das Ziel (The Way is the Goal), Dürckheim recalls:

As soon as I had returned to Germany [from Japan in 1939], Ribbentrop summoned me. In the meanwhile he had become foreign minister, yet he never abandoned people he had worked with. He said to me: “I would like to conclude a treaty with Russia. Here is the draft. You are the first one I’m showing it to. What will the Japanese say?” “Well,” I replied, “of course they will not be very happy about it, Mr. von Ribbentrop.”25

This incident suggests just how important Dürckheim had already become, at least concerning Japanese affairs.

By the spring of 1940 Germany had achieved an impressive list of military victories leading to the occupation of Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, and, most important, France. The defeat of England seemed to be only a matter of time. This led Japan to approach Germany with the goal of ensuring protection of its own sphere of influence in East Asia. As for Germany, as it became clear that the defeat of England would take longer than expected, especially in the face of possible US intervention in Europe as well as East Asia. Thus, Germany, too, once again became interested in a military alliance with Japan. This time renewed negotiations bore fruit in the form of the Tripartite Pact between Germany, Japan and Italy, signed on September 27, 1940.

|

Signing of the Tripartite Pact |

Dürckheim continued to work for Ribbentrop during his second stay in Japan. This time his work included collecting information about Japanese opinion concerning Germany and its policies as well as organizing propaganda for the Nazis, especially at the academic level. About this, Dürckheim recalls:

Then the war started. The day after [Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939] Ribbentrop summoned me and said: “We need somebody to maintain contact with scientists in Japan.” I answered: “Mr. Von Ribbentrop, I can’t wait to return to Japan.” “OK,” he answered, “then come back tomorrow and tell me what you want to have [to carry out this task].” The next day I said to him: “I want eighty libraries consisting of one hundred volumes each.” “What do you mean?” “Eighty libraries with one hundred volumes in each is a library for every teacher at German schools [in Japan].” He said “OK, approved. I think this is reasonable.”26

In addition, Dürckheim sought to place pro-Nazi articles in important Japanese journals while supplying the German Foreign Office’s propaganda magazine, Berlin-Rom-Tokyo, with articles about Japan. He also claims to have played a role in the preparation of the Tripartite Pact signed on September 27, 1940.27 Despite his lack of official status in Germany’s Foreign Ministry, Dürckheim was clearly an important, even key, figure in promoting the wartime relationship between the two countries.

Gerhard Wehr’s View of Dürckheim in Japan

A major divergence in viewpoints is evident in the available descriptions of Dürckheim’s activities during his second residence in Japan. This divergence might best be characterized as a divergence between those in Europe who described Dürckheim’s residence in Japan from outside Japan, and without knowledge of Japanese, and those who described him from within Japan, primarily from Japanese sources.

Among those in the first category is Gerhard Wehr, Dürckheim’s biographer and admirer. Wehr acknowledges that his subject eagerly embraced his new duties as a Nazi emissary: “In the wave of enthusiastic nationalism, Dürckheim saw himself as a useful representative of the ‘new Germany’ for his people and his employers in Berlin, for the Minister of Foreign Affairs Von Ribbentrop, and for the Minister of Education, Bernhard Rust.”28

Wehr further states: “And as his biography shows, it was not hard for him to obey the orders of his superiors.” Yet, Wehr immediately adds: “But in the background, there was always this other tendency toward the spirituality of the East, and especially toward Zen Buddhism; later it will be for Zen as a trans-religious attitude in universal man, the practice of spiritual exercise and disciplines.”29

Wehr also informs us: “From the outside, in the years 1930 to 1940, Professor Karlfried Graf [Count] Dürckheim seemed to be a cultural envoy of the Third Reich. At the same time, a subterranean process of transformation of which he was hardly conscious was taking place.”30

Thus, on the one hand, Wehr admits that, at the very least, Dürckheim was in the employment of the Nazis, but on the other hand he claims that from the very outset of his residence in Japan, Dürckheim was drawn toward the spirituality of the East, most especially Zen.

Yet, what exactly was this transformational “subterranean process” Dürckheim was undergoing? Wehr introduces a quote from Dürckheim describing how his spiritual journey after arriving in Japan led him to practice not only Zen but also traditional Japanese archery and painting as well:

Out of personal preference, I came to know many Zen exercises. I even worked outside of meditation (zazen), especially in archery and painting. It is surprising to notice that from the point of view of Zen, the most varied arts have the same purpose, whether it be archery or dance, song or karate, floral decoration or aikido, the tea ceremony or spear throwing. . . . Done in the spirit of Zen, they are merely different ways aiming toward the same thing: the breakthrough toward the nature of Buddha, toward “Being.”31

Wehr goes on to inform his readers that “the thought at the foundation of this special exercise [i.e., archery] . . . is Zen. Further, through his practice of Zen and Zen-influenced arts Dürckheim feels that he is able to approach “the Japanese character,” the ultimate expression of which is that “a person realizes himself completely, discovering in his way the Divine. And that is of course what man feels most directly.”32 Yet, throughout the entire period Dürckheim pursues his spiritual interests he remains in the service of the Nazis.

The preceding comments raise two interesting questions. First, is Zen practice, especially as it is allegedly found in Japanese arts like archery, really in conflict with the ideology of National Socialism? And second, are all of these arts, particularly archery, really connected to Zen in the first place?

Dürckheim and Eugen Herrigel

|

Eugen Herrigel |

Dürckheim tells us that he was drawn to the practice of archery thanks to Eugen Herrigel, the well-known author of the short classic, Zen in the Art of Archery. According to Wehr:

Dürckheim remembers having read an article by his colleague Eugen Herrigel dealing with the martial arts. He is therefore already familiar with the thought at the foundation of this special exercise that is Zen. And as this master of archery follows the same tradition as Herrigel, it is an added incentive to become initiated in this discipline. “That is what led me to begin this activity. I knew that I would learn things about Japan which would be useful to me and which cannot be found in books or in any other way.”33

The first problem with Wehr’s description is that subsequent research has shown that Dürckheim did not study archery with a teacher in the lineage of Awa Kenzō, i.e., someone who “follows the same tradition as Herrigel.” However, Dürckheim may not have been aware of this. Dürckheim provides a more detailed description in his book Der Weg ist das Ziel (The Way is the Goal): “One day in 1941 a Japanese friend invited me, ‘Come with me, my master is here. What master? The master of archery.’ This is how I got to know master Kenran Umechi [Umeji].”34

The Japanese scholar Yamada Shoji emphasizes that Umeji was not in Awa’s lineage. Instead, he was simply another archery instructor of that era. The only known connection between the two men was that Awa once visited Umeji to query him about a fine point of archery technique. In the aftermath of his visit Umeji’s disciples claimed that their master was the greater of the two, going so far as to suggest that Awa was one of Umeji’s students. Unsurprisingly, Awa’s students adamantly rejected this claim.35

Be that as it may, there nevertheless appears to be a genuine connection between Dürckheim and the martial art of archery. Additionally, Zen is identified as the “foundation of this special exercise.” There is, however, yet another problem with this scenario, for as Yamada Shoji has demonstrated, the connection of Zen to archery is, historically speaking, little more than a modern myth, primarily created even in Japan itself by Herrigel:

Looking back over the history of kyūdō [archery], one can say that it was only after World War II that kyūdō became strongly associated with Zen. To be even more specific, this is a unique phenomenon that occurred after 1956 when Zen in the Art of Archery was translated and published in Japanese. . . . This suggests that the emphasis on the relationship between the bow and Zen is due to the influence of Zen in the Art of Archery.36

Yamada reveals moreover that Herrigel himself never underwent any formal Zen training during his five-year stay in Japan from 1924-29. Yamada also informs us that Awa “never spent any time at a Zen temple or received proper instruction from a Zen master.”37 Awa did, however, teach something he called Daishadōkyō (Great Doctrine of the Way of Shooting) that included a religious dimension he expressed using elements of Zen terminology. Awa’s Japanese students noted this Great Doctrine consisted of “archery as a religion” in which “the founder of this religion is Master Awa Kenzō.”38 Herrigel also refers to the “Great Doctrine” but, as Yamada notes: “Herrigel offered no explanation of what the “Great Doctrine” might be, so readers of Zen in the Art of Archery had no way of knowing that this was simply Awa’s personal philosophy.”39

Yet another key component of Herrigel’s archery training was the mystical spiritual experience he claimed to have had, expressed verbally as “‘It’ shoots” rather than the familiar “I shoot (an arrow).” The spiritual connection came from Herrigel’s identification of “It” with “something which transcends the self.”40 Inasmuch as this expression appears to resonate with Zen teaching the question must be asked, what’s the problem?

The problem is, as Yamada explains: “There is no record of Awa ever having taught: “‘It’ shoots” to any of his disciples other than Herrigel.”41 How is this possible? Yamada’s painstaking research led him to the following conclusion:

When Herrigel made a good shot, Awa cried, “That’s it!”. . . . “That’s it” was mistakenly translated to Herrigel [in German] as “‘It’ shoots,” and Herrigel understood “It” to mean “something which transcends the self.” If that is what happened, then the teaching of “‘It’ shoots” was born when an incorrect meaning filled the void created by a single instance of misunderstanding.42

The relevance of this alleged “misunderstanding” to Dürckheim is that the latter shared the same misunderstanding, albeit under a different master with only a tenuous connection to Awa. During an interview with German television at the age of eighty-seven Dürckheim said:

I still remember the day, in the presence of the master, when I shot an arrow and it left on its own. “I” had not shot it. “It” had shot. The master saw this and took the bow in his hands, then took me in his arms (which is very rare in Japan!) and said: “That’s it!” He then invited me to tea. That is how archery taught me so much, for the mastery of a traditional Japanese technique does not have as goal a performance, but on the contrary requires the achievement of a step forward on the inner path.43

Dürckheim thus used nearly the same words as Herrigel to describe his mystical experience, i.e., “‘It’ had shot.” Yet, unlike Herrigel, Dürckheim did not claim that his archery master had used these words. Instead, he states that, upon seeing Dürckheim’s accomplishment, his archery master said, “That’s it!” Not only does this episode provide strong evidence that Yamada’s conclusion is correct, but it also suggests that, since neither Herrigel nor Dürckheim were fluent in Japanese, Dürckheim, at least, had the superior interpreter.

That said, where had Dürckheim first learned the expression, “‘It’ shoots” if not from Herrigel’s writings? As noted above, Awa did not employ this expression in his teaching which, in any case, was not based on any Zen training but rather on his own personal philosophy that included Zen expressions. This forces us to recognize that there was no “Zen” in the “art of archery” other than that first created in Herrigel’s mind based on a mistaken translation of Awa’s words.

For his part, Dürckheim subsequently accepted this mistaken translation at face value. Further, as we have seen, Dürckheim mistakenly believed his archery master “follow[ed] the same tradition as Herrigel.”44 Thus, it can be said that while Dürckheim had the superior interpreter, there was nothing “superior” or even “accurate” in either man’s understanding of their practice of archery or its non-existent historical relationship to Zen.45

Be that as it may, the importance of this discussion is that the connection of archery to Zen was not an ancient tradition that Herrigel encountered while in Japan, nor was the practice of archery understood as an alternate form or expression of Zen practice. As Yamada, himself an accomplished student of archery, states, Zen’s connection to archery is primarily a postwar “myth” that Herrigel himself promoted.46

Finally, it is not surprising that Dürckheim would have also embraced this myth in light of the fact that Herrigel, in his writings from 1936, promoted a völkisch religious understanding very similar to that of Dürckheim. Further, Dürckheim was aware of these 1936 writings before he started his own practice of archery. This völkisch understanding was, however, not the only thing the two men shared in common.

A Shared Nazi Past

In a political context, the most important feature Herrigel and Dürckheim shared was their active allegiance to National Socialism, an allegiance that was of great benefit to both of their careers. Herrigel joined the Nazi party on May 1, 1937. The following year he became the vice rector of the University of Erlangen and in 1944 was promoted to rector, a post he held to the end of the war. As Yamada notes: “In a climate where right-minded scholars were leaving the universities in droves, only a person who had ingratiated himself with the Nazis could hope to climb as high as rector.”47

During the Nazi era Herrigel wrote such essays as “Die Aufgabe der Philosophie im neuen Reich” (The Task of Philosophy in the New [Third] Reich) in 1934 and “Nationalsozialismus und Philosophie” (National Socialism and Philosophy) in 1935. In 1944, as an expert on Japan, he wrote, “Das Ethos des Samurai” (The Ethos of the Samurai). Herrigel’s wartime writings reveal him to have been an enthusiastic Nazi.48 For example, in 1935 Herrigel described Hitler as follows:

The miracle happened. With a tremendous drive that made all resistance meaningless, the German Volk was carried away. With unanimous determination it endorsed the leader. . . . The fight for the soul of the German Volk reached its goal. It is ruled by one will and one attitude and commits itself to its leader with a kind of unity and loyalty that is unique within the checkered history of the German Volk.49

Given this it is not surprising to learn that following Germany’s defeat Herrigel was brought before the denazification court at Erlangen. Although he strenuously denied any wrongdoing, he was nevertheless found guilty of having been a Mitläufer (lit. a “runner with”) of the Nazis. In terms of guilt, this was one rank below that of a committed Nazi, but it nevertheless resulted in his dismissal from the university. Thereafter he retired, dying of lung cancer in 1955.

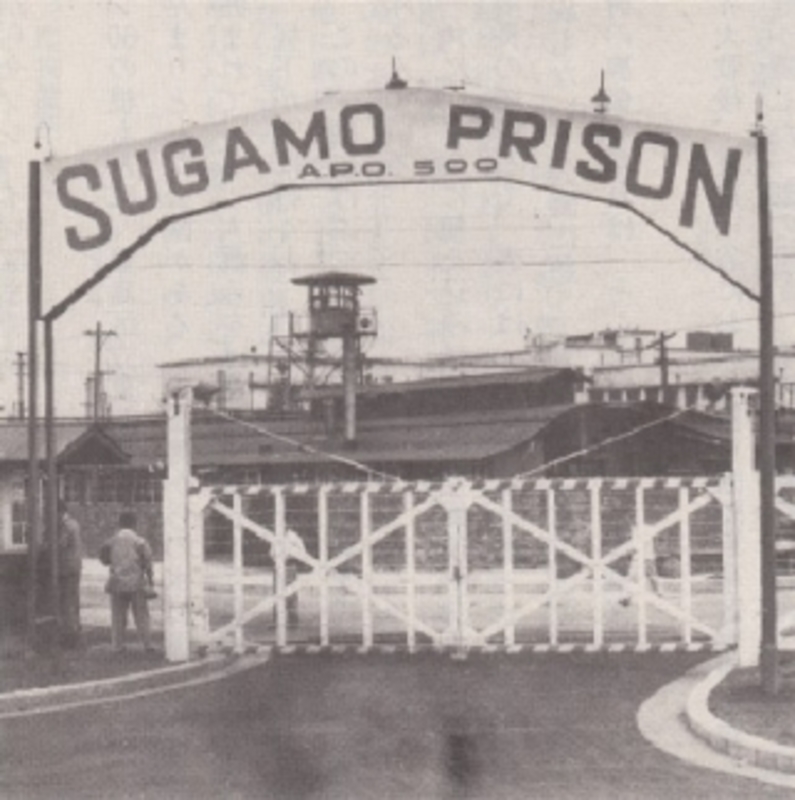

Thus, it can be said that, unlike Dürckheim who successfully hid his Nazi past in postwar Germany, Herrigel did pay a price for his wartime collaboration. Had Dürckheim been in Germany at war’s end, he, too, might have faced a reckoning. Given his role as a tireless propagandist for the Nazi cause, he might very well have been convicted of having been a Belasteter (Offender), i.e., an activist, militant, profiteer, or incriminated person. The punishment for those convicted of this status was imprisonment for up to 10 years. Thus Dürckheim was fortunate to spend only eighteen months in Tokyo’s Sugamo prison.

Dürckheim, Herrigel and Suzuki’s Postwar Relationship

There was one additional thing Dürckheim and Herrigel shared in common, i.e., their longstanding relationship with D.T. Suzuki, a relationship that continued into the postwar era. Dürckheim recalls:

[Suzuki] later came to see me at Todtmoos. It was in 1954, and I had just received a telegram of the Protestant Academy of Munich asking me to do a conference on oriental wisdom. I took advantage of his presence to ask him: “Master, could you tell me in a few words what oriental wisdom is?” He smiled and said: “Western knowledge looks outside, Eastern knowledge looks within.” I said to myself: “That is not such a great answer. . .” Then he continued: “But if you look within the way you look without, you make of the within a without.” That is an extraordinary statement! It reveals the whole drama of western psychology which looks within the way we look without, making of the within a without, that is, an object. And life disappears.50

Dürckheim noted that during his visit Suzuki expressed his interest in meeting Martin Heidegger who lived nearby:

I met Heidegger again twenty years later, when Suzuki, the eighty-year old prophet of Zen visited me and wanted to see him. It was an encounter of a man of the word with a man, who, as a Zen Master, is certain that in opening our mouth we are already lying! For only silence contains truth.51

|

Martin Heidegger |

It should be noted that Heidegger’s own Nazi past was also the subject of ongoing controversy in the postwar period inasmuch as he had joined the NSDAP on May 1, 1933, ten days after being elected Rector of the University of Freiburg. However, in April 1934 he resigned the Rectorship and stopped attending Nazi Party meetings. Nevertheless, Heidegger remained a member of the Party until its dismantling at the end of World War II. More recently, scholars in both Germany and America have demonstrated the profound affinities between Heidegger’s thought and his reactionary milieu. In the postwar period, Heidegger commented: “If I understand this man [Suzuki] correctly, this is what I have been trying to say in all my writings.”52

As for Herrigel, his relationship to the Nazis is, as noted above, far clearer. Herrigel’s significant postwar connection to Suzuki is well illustrated in Suzuki’s preface to the 1953 English edition of Herrigel’s classic. Suzuki wrote:

In this wonderful little book, Mr. Herrigel, a German philosopher who came to Japan and took up the practice of archery toward an understanding of Zen, gives an illuminating account of his own experience. Through his expression, the Western reader will find a more familiar manner of dealing with what very often must seem to be a strange and somewhat unapproachable Eastern experience.53

Suzuki’s appreciation of Herrigel’s “wonderful little book” is high praise indeed for a man who stated in a 1959 conversation with the Zen scholar Hisamatsu Shin’ichi that no Westerner had yet understood Zen despite the many books that Westerners had written on this topic. Was Herrigel then the single exception? In fact, he was not, for when Hisamatsu asked Suzuki’s assessment of Herrigel, Suzuki replied: “Herrigel is trying to get to Zen, but he hasn’t grasped Zen itself. Have you ever seen a book written by a Westerner that has?”54 Suzuki was then asked why he had agreed to write the introduction to Herrigel’s book? “I was asked to write it, so I wrote it, that’s all,” he replied.55

There is no reason to believe that Suzuki would have had a higher regard for Dürckheim’s understanding of Zen. Dürckheim was, after all, just another “Westerner” and definitely not Japanese. In an article written in June 1941 Suzuki claimed: “The character of the Japanese people is to come straight to the point and pour their entire body and mind into the attack. This is the character of the Japanese people and, at the same time, the essence of Zen.”56 Given this, how could any Westerner aspire to understanding “the essence of Zen” while lacking “the character of the Japanese people”?

At the same time, given the historical non-relationship of Zen to archery, the question must be asked as to what this tells us about Suzuki’s own understanding of Zen? That is to say, did he knowingly participate in what Yamada described as a postwar “myth”? If so, what was his purpose? Interesting as these questions may be, they lie beyond the scope of this article to explore.

Wehr’s Defense of Dürckheim

Unsurprisingly, Wehr provides us with none of this information about Herrigel let alone about any personal relationship Dürckheim may have had to him. Nor, for that matter, does Wehr inform us much about Dürckheim’s relationship with Suzuki either during or after the war. His focus is on one thing, weakening Dürckheim’s connection to National Socialism while simultaneously strengthening his relationship to Zen:

Reflections such as these still do not reveal the distance which Dürckheim is taking vis-à-vis National Socialism and his own concept of nationalist culture. These two worlds still co-exist for him. He is attempting to harmonize his nationalist ideals and his spiritual interests. He does not yet realize that he will have to make a decision if he continues his inner path. He believes that what Zen Buddhism offers him is a gain to his exterior status.57

Thus, Wehr would have us believe that as Dürckheim’s understanding of Zen deepened he was slowly drawn away, if only unconsciously, from the Nazis’ worldview to that of Zen. In fact, he would “have to make a decision,” i.e., choosing either Zen or National Socialism. But did Dürckheim ever make such a choice? On this crucial point Wehr is silent. The best Wehr could do was to admit: “The quoted biographical documents suggest that it was a very slow process of change.”58

Nevertheless, Wehr goes on to claim that Dürckheim became such an accomplished Zen practitioner that he had an initial enlightenment experience known as satori. Not even Herrigel had explicitly claimed this for himself. Wehr wrote:

Toward the end of his stay in Japan, Dürckheim experienced satori, the aim of Zen: a degree of illumination of reality. Through this he achieved the “spiritual break-through toward ultimate reality.” In this way a greater Self is uncovered, beyond the ordinary self. This greater Self, and the destiny linked to it, does not spare a person on the inner way from trials. In the following stages of his life, Dürckheim experienced an imprisonment of a year and a half in the prison of Sugamo in Tokyo under the control of the American Occupation.59

Once again the reader is presented with the incongruous relationship between a confirmed Nazi, a suspected war criminal in postwar Japan, and an enlightened Zen practitioner. Yet, when did Dürckheim have his enlightenment experience? Was it before, or after, he was imprisoned at war’s end? And who was the Zen master who authenticated Dürckheim’s enlightenment experience as is required in the Zen school? Did Dürckheim even train under a recognized Zen master? Wehr once again remains silent.

Wehr does, however, quote Dürckheim in describing his incarceration in the Sugamo prison:

In spite of everything, it was a very fertile period for me. The first weeks I had a dream almost every night, some of which anticipated my future work. In my cell, I was surrounded by a profound silence. I could work on myself and that is when I began to write a novel. My neighbors simply waited for each day to pass. That time of captivity was precious to me because I could exercise zazen meditation and remain in immobility for hours.60

The fact that Wehr tells us Dürckheim experienced satori “toward the end of his stay in Japan” suggests that Dürckheim had what he believed to be satori while in prison, for, as noted, he was incarcerated for some eighteen months under suspicion of being a Class A war criminal before finally being released without trial and repatriated to Germany. If Dürckheim did experience satori in prison, it would have been impossible for a Zen master to verify his experience. Thus, within the norms of the Zen tradition, and without additional clarifying evidence, the authenticity of Dürckheim’s claim must remain suspect if not denied outright. Nevertheless, Wehr ends his description of Dürckheim’s experience in Japan as follows: “The years in Japan represent a special formation for Dürckheim’s later work as teacher of meditation and guide on the inner path.”61

In fairness to Dürckheim, it should be noted that upon his return to Germany he did not claim to be a “Zen master” although it appears there were those around him who regarded him as such. About this, Dürckheim said: “What I am doing is not the transmission of Zen Buddhism; on the contrary, that which I seek after is something universally human which comes from our origins and happens to be more emphasized in eastern practices than in the western. What interests us is not something uniquely oriental, but something universally human which the Orient has cultivated over the centuries and has never fully lost sight of.”62

In a conference held in Frankfort, Dürckheim went further:

I find it especially shameful that people say: the experiences of Being which Dürckheim brings us are imported from the East. No, the experience of Being is everywhere in the world, even if it is given different names according to the religious life which has developed there, if we understand by the word “Being” the Divine Being. All reflection on Being begins with this experience. . . .This experience can truly help man feel and assist him in living something contradictory to his usual self and his ordinary view of life, and make him suddenly experience another force, another order and another unity. It is obviously greater, more powerful, more profound, richer and vaster than anything else he can live through.63

Yet, in another sense, it can be said that Dürckheim claimed to be far more than a mere Zen master. That is to say, over the years Dürckheim came to express his Zen-induced experience of a “breakthrough of Being” as a breakthrough of Being in Christ.64 Thus, he conceived of himself as having incorporated the essence of Eastern spirituality as encapsulated in Zen into an esoteric understanding of Christianity. Dürckheim states: “Man is in his center when he is one with Christ and lives through Christ in the world without ever leaving the voice of the inner master which is Christ and continually calls him toward the center. Here Christ is not only the ‘Being of all things,’ nor the intrinsic Path in each one of us, but also Transcendence itself.”65

In claiming this, Dürckheim placed himself at the apex of a new, or at least revitalized, religious movement that, on the one hand, enjoyed deep roots within the Christian mystical tradition even while incorporating the “enlightenment experience” of ancient Eastern wisdom. Whereas by the modern era Christian mysticism lacked (or had lost) a clear-cut methodology for achieving Transcendence, the Zen school had maintained a meditative practice based on zazen and allegedly associated arts. Dürckheim could claim to have combined the best of both worlds, placing him in a unique position among religious teachers. In a postwar Germany still struggling to free itself from the bitter legacy of the Nazi era, it is not surprising that Dürckheim would have been an attractive figure.

Nevertheless, to the detached observer it can only be a source of amazement that a once dedicated and tireless propagandist for an utterly ruthless totalitarian ideology could, with a metaphorical flip of the hand, transform himself in the postwar era into someone who embodied the elements of a universal spirituality. That is to say, he became someone who, claiming to have experienced satori, proceeded to incorporate his understanding of Eastern spirituality into a transcendent, mystical form of Christianity, all without having acknowledged, let alone expressed the least regret for, his Nazi past.

As for Wehr, it can be said that, at least by comparison with Satō who falsified Suzuki’s opposition to the Nazis, he honestly admitted Dürckheim’s Nazi past. Yet, having made this admission, Wehr immediately set about attempting to downplay Dürckheim’s Nazi affiliation as much as possible. He did this by replacing his political affiliation to fascism with a Zen-based narrative of spiritual growth that gradually removed Dürckheim from the world of National Socialism even though the latter is described as having been largely unaware of his transformation.

But is this description correct?

The Search for Evidence

In searching for evidence to assess Wehr’s description of Dürckheim in Japan, the author could but regret how little space Wehr devoted to such things as his relationship to National Socialism, Zen and Zen figures like Suzuki. It was just at this time, i.e., June 2011, when Hans-Joachim Bieber, Prof. Emeritus of Kassel University, sent me an e-mail that ended as follows:

There is one source which could probably give more information about Dürckheim’s encounter with Zen Buddhism and perhaps with D.T. Suzuki personally during his years in Japan: Dürckheim’s diaries. They are unpublished and belong to the Dürckheim family in Germany. They have been used by Dürckheim’s first biographer (Gerhard Wehr, Karlfried Graf Dürckheim, Freiburg 1996). Wehr found out that Dürckheim had been a fervent Nazi. For the Dürckheim family and Dürckheim’s students his book was a shock (despite the fact that Wehr basically was an adherent of Dürckheim). And my impression is that since then the family doesn’t allow anyone to use Dürckheim’s diaries. At least they refused my request.66

In reading this I could not help but empathize with Wehr and the shock he must have felt upon learning of Dürckheim’s Nazi past. This author, too, underwent a similar experience when first becoming aware of Suzuki’s wartime writings, having originally believed and been inspired by Suzuki when he claimed: “Whatever form Buddhism takes in different countries where it flourishes, it is a religion of compassion, and in its varied history it has never been found engaged in warlike activities.”67

At the same time the author could not help but admire Wehr, at least to some degree, for having included Dürckheim’s Nazi affiliation in his biography of a figure he clearly deeply admired. The phrase “at least to some degree” is used because Wehr continually tried to show Dürckheim distancing himself from National Socialism in tandem with his growing interest in Zen.

Further, it was impossible not to empathize with Bieber as well. Just as Bieber had attempted to research Dürckheim’s wartime record in Germany, the author sought to explore Suzuki’s relationship to Dürckheim in Japan. In Bieber’s case, the Dürckheim family turned him away, refusing to permit access to Dürckheim’s diaries. In the author’s case, I met with a stony silence when repeatedly seeking permission to access Suzuki’s extensive personal library, known as the Matsugaoka Bunko, located in Kita-kamakura not far from Tokyo.

D.T. Suzuki’s Diaries

Nevertheless, there is one significant difference as far as Suzuki’s wartime diaries (1936-45) are concerned. That is to say, Matsugaoka Bunko published Suzuki’s wartime diaries over a period of six years, from 2007 thru 2012, in their yearly research organ, The Annual Report of the Researches of the Matsugaoka Bunko. Surprisingly, Suzuki kept these diaries in English so there can be no doubt about their meaning.

The diaries show that Suzuki maintained an ongoing relationship with Dürckheim throughout the war years, beginning with a flurry of activity involving Dürckheim in January 1939. There is, further, nothing in these 1939 entries to suggest that this was the first time the two men had met. Thus, it is likely they had met earlier. In addition, following Dürkheim’s return to Japan, i.e., on July 14, 1942, Suzuki writes: “Telegram to Graf [Count] Dürckheim re his invitation to lunch tomorrow,”68 and on February 15, 1943: “Went to Tokyo to take lunch with Graf von Dürckheim and stayed some time with him.”69

It is noteworthy that Suzuki’s contact with leading Nazis in Japan was not limited to Dürckheim. As we have already seen, Suzuki lunched with Ambassador (and Major General) Ott as early as January 18, 1939. Further, on February 4, 1943 Suzuki took part in a dinner party to honor the ambassador: “Went to Imperial Hotel to attend dinner party given to Amb. Ott and his staff,”70 and on February 16, 1943 Suzuki received “a box of fruits in recognition of my presence at a dinner party in honor of Amb. Ott of Germany.”71

Suzuki’s diaries also contain frequent references to lectures at German-related venues beginning as early as May 28, 1938: “Lecture at German research institute for K.B.S. in the evening”72 followed on June 26, 1938 by: “Kurokawa and Kato brought money for my lecture at German Institute.”73 Additional references to lectures include: the German Society on September 13, 1943; German residents in Tokyo on October 4, 1943; the German Club on December 10, 1943; and the German Society, once again, on December 15, 1943.74

One reason these lectures are important is because Dürckheim states:

When I came to Japan, I did not know anything about Zen. Very soon I met the Zen-master Suzuki, the greatest Zen-scholar of our time. I heard many of his lectures, and through him I discovered Zen.75

Dürckheim’s Zen study with Suzuki appears to have consisted of a number of personal meetings punctuated with attendance at Suzuki’s lectures on Zen at German venues. Needless to say, simply listening to lectures about Zen does not constitute Zen practice. In fact, an academic understanding of Zen sans practice is often castigated as the very epitome of a mistaken approach to Zen, relying, as it does, on conceptual thought.

In the postwar period Dürckheim was specifically asked about this: “With which Zen exercise did you start your Zen practice? Zen is a kind of practice which one has to learn, isn’t it?” To which Dürckheim responded: “My access was through archery.”76

Suzuki’s luncheon with Dürckheim and Ambassador Ott on January 18, 1939 took place just two months after the massive, coordinated attack on Jews throughout the German Reich on the night of November 9, 1938. This anti-Jewish violence, known as Kristallnacht, or “Night of Broken Glass,” was accompanied by the torching of hundreds of synagogues together with their Torah scrolls. Although Kristallnacht was widely condemned by governments, newspapers and radio commentators throughout the world, and despite his many contacts in the English-speaking world, Suzuki was undeterred from maintaining his contacts with Dürckheim and the German embassy either then or for the remainder of the war.

Thanks to the publication of Suzuki’s diaries, it can be argued that we have a more detailed picture of Suzuki’s wartime actions than we do those of Dürckheim. For example, we now know that between 1938 and 1944 Suzuki met with five Imperial Navy Admirals (Mori, Yamaji, Yamanashi, Nomura and Sato) on eight occasions.77 Moreover, Suzuki was in contact or dined with Count Makino Nobuaki on forty-four occasions between 1930 and 1945 (thirty-one times between 1936-45). The extremely rightwing Makino was one of Emperor Hirohito’s closest advisors, having served him as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal from 1925 to 1935. As late as February 1945 Makino met Hirohito together with six former prime ministers and, despite Germany’s impending defeat, urged him to continue the war, saying “the ultimate priority is to develop an advantageous war situation.”78

Suzuki’s connection to someone as close to the emperor as Makino is indicative of Suzuki’s access to Imperial Court circles.79 Additionally, it raises the question of Suzuki’s own attitude to the emperor, especially as references to the emperor, either positive or negative, are all but absent from his published writings in either English or Japanese. Some Suzuki supporters have interpreted this absence as a sign that he was either opposed, or at least critical, of the Imperial system and the ultra-nationalism associated with it.

Fortunately, there is one wartime report on Suzuki’s view of the emperor supplied, interestingly enough, by yet further wartime German visitors to Japan. The visitors in question were not themselves Nazis but, despite having once come under suspicion by the Gestapo, were nevertheless given permission to travel on Christian mission-related business in both China and Japan. These missionary visitors were Gerhard Rosenkrantz and his wife who visited Japan in 1939. They requested a meeting with Suzuki and met him in the library of what was then Otani College where he was teaching:

“We Buddhists,” Suzuki told them, “bow in front of the emperor’s image, but for us this is not a religious act. The emperor is not a god because for Buddhists a [Shinto] god can be something very low. We see the emperor in an area high above all religions. Trying to make him a god today means a reduction in the status of the emperor. This brings confusion to Buddhism, Shinto and Christianity.”80

Thus, even while denying the emperor’s status as a Shinto deity, Suzuki nevertheless justified bowing to the emperor’s image as a Buddhist because he was a personage “high above all religions.” Suzuki, of course, never publicly denied the emperor’s divinity in his wartime Japanese writings.

Regrettably, we cannot be sure what Suzuki told his German audiences because even though nearly seventy years have elapsed since the end of WWII, the attempt to preserve his reputation, similar to that of Dürckheim himself, continues to be an important task for those who were close to both men and now seek to preserve their respective legacies.

The View of Dürckheim from within Japan

As for Dürckheim, we do have one observer who had first-hand knowledge of his activities within Japan. He was a German academic by the name of Dr. Dietrich Seckel. Seckel taught in Japan from 1937 to 1947 and later at Heidelberg University from 1965 to 1976. He described Dürckheim’s wartime activities in Japan as follows:

Dürckheim also went to Zen temple[s] where he meditated. However, his study and practice of Zen Buddhism has been extremely exaggerated. In particular, I felt this way because, at the same time, he was propagating Nazism. There was something incongruous about this. I recall seeing him at a reception at the German Embassy. At that time he was poking his finger into the breast of one of the most famous Japanese professors of economics who was wearing a brown silk kimono. While explaining the ideology of the German Reich to him, Dürckheim kept pushing the poor professor back until the latter reached the wall and could go no further. I could not help but feel pity for this professor who was the subject of Dürckheim’s indoctrination.

Dürckheim thought of himself as a friend and supporter of German teachers [in Japan]. He provided us with everything he could think of. He lectured everywhere ceaselessly with his lectures first being translated into Japanese and then, later on, distributed to all German residents in the original German. His speeches arrived in the mail on an almost daily basis. It was extremely unpleasant. He was what might be called an excellent propagandist who, possessed of a high intellectual level, traveled throughout Japan teaching Nazism and the ideology of the Third Reich.”81

The above account is instructive in a number of ways, first of all because it reveals that Dürckheim viewed himself as a friend and supporter of German teachers in Japan. In fact, as we have seen, even during his first visit to Japan in August 1938 he had visited the Japanese faction of the National Socialist Teachers Association (NS-Lehrerbund). There he talked about the principles and forms of national socialist education and the difference between the national socialist understanding of freedom and a liberal conception of it.

Further, Seckel describes Dürckheim as “an excellent propagandist who, possessed of a high intellectual level, traveled throughout Japan teaching Nazism and the ideology of the Third Reich.” Neither Dürckheim’s intelligence nor his dedication to propagating Nazi ideology can be in doubt. In fact, he was so dedicated in his work that he was awarded the War Merit Cross, Second Class on Hitler’s birthday, April 20, 1944. Dürckheim shared this honor with such prominent Nazis as Adolf Eichmann and Dr. Josef Mengele. Yet, what of his interest in Zen? “. . . his study and practice of Zen Buddhism has been extremely exaggerated,” Seckel informs us.

We have already learned that early in Dürckheim’s first sojourn in Japan he claimed to have met D.T. Suzuki, someone whom Dürckheim describes as “one of the greatest contemporary Zen Masters.” Suzuki, of course, was not a Zen master, and he never claimed this title for himself. He was, instead, a lay practitioner and regarded as such by the Rinzai Zen sect with which he was closely affiliated. That said, Suzuki did have an initial enlightenment experience, i.e., satori, as a young man and, unlike Dürckheim, had his enlightenment experience verified by a noted Rinzai Zen master, Shaku Sōen. Additionally, Suzuki also possessed significant academic accomplishments as a Buddhist scholar, especially as a translator of Buddhist texts.

Does this mean, then, that Dürckheim never practiced with a recognized Zen master in Japan? No, for the record is clear that Dürckheim did indeed train, albeit for only a few days, with Yasutani Haku’un, then a Sōtō Zen priest, who, in the postwar era, became a well-known Zen master in West, particularly the U.S. We know about Dürckheim’s training with Yasutani thanks to Hashimoto Fumio, a former higher school teacher of German, who served as Dürckheim’s interpreter and translator at the German embassy in Tokyo.

Hashimoto described his relationship to Dürckheim as follows:

When Dürckheim first arrived in Japan, he was surrounded by Shintoists, Buddhist scholars, military men and right-wing thinkers, each of whom sought to impress him with their importance. The Count found it difficult to determine who of them was the real thing, and I stepped in to serve as his advisor. In addition, a great number of written materials were sent to him, and my job was to review them to determine their suitability. . . .

In the end, what most interested the Count was traditional Japanese archery and Zen. He set up an archery range in his garden and zealously practiced every day. In addition, he went to Shinkōji temple on the outskirts of Ogawa township in Saitama Prefecture where he stayed to practice Zen for a number of days. His instructor in zazen was the temple abbot, Master Yasutani [Haku’un]. I accompanied the Count and gladly practiced with him.82

|

Yatsutani Haku’un |

Hashimoto relates that it was he who first took an interest in Yasutani because of the latter’s strong emphasis on both the practice of zazen and the realization of enlightenment. This emphasis on practice was a revelation for him, for until then his only knowledge of Buddhism had come from scholars who “had never properly done zazen or realized enlightenment.”83 In particular, Hashimoto was impressed by Yasutani’s 1943 book on Zen Master Dōgen and a modern-day compilation of Dōgen’s teachings for the laity known as the Shūshōgi. Hashimoto claimed that Yasutani’s book revealed “the greatness of this master [i.e. Yasutani] and the profundity of Buddhism.”84 So impressed was Hashimoto that not only did he provide Dürckheim with a detailed description of the book’s contents but went on to translate the entire book into German for him.

Thus, Yasutani’s book, coupled with Hashimoto’s recommendation, was the catalyst for Dürckheim’s training at Shinkōji albeit for only “a number of days.” Dürckheim could not help but have been aware of Yasutani’s extremely right-wing, if not fanatical, political views as clearly expressed in his book. Given this, the author asks for the reader’s understanding in quoting extensively from his book. It is done in the belief that if we are to understand Dürckheim’s view of Zen we need to become acquainted with the teachings of the only authentic Zen master he appears to have trained under, albeit briefly.

Yasutani described the purpose of his book as follows:

Asia is one. Annihilating the treachery of the United States and Britain and establishing the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere is the only way to save the one billion people of Asia so that they can, with peace of mind, proceed on their respective paths. Furthermore, it is only natural that this will contribute to the construction of a new world order, exorcising evil spirits from the world and leading to the realization of eternal peace and happiness for all humanity. I believe this is truly the critically important mission to be accomplished by our great Japanese Empire.

In order to fulfill this mission it is absolutely necessary to have a powerful military force as well as plentiful material resources. Furthermore, it is necessary to employ the power of culture, for it is most especially the power of spiritual culture that determines the final outcome. In fact, it must be said that in accomplishing this very important national mission the most important and fundamental factor is the power of spiritual culture. . . .

It is impossible to discuss Japanese culture while ignoring Buddhism. Those who would exclude Buddhism while seeking to exalt the Spirit of Japan are recklessly ignoring the history of our imperial land and engaging in a mistaken movement that distorts the reality of our nation. In so doing, it must be said, such persons hinder the proper development of our nation’s destiny. For this reason we must promulgate and exalt the true Buddha Dharma, making certain that the people’s thought is resolute and immovable. Beyond this, we must train and send forth a great number of capable men who will be able to develop and exalt the culture of our imperial land, thereby reverently assisting in the holy enterprise of bringing the eight corners of the world under one roof.85

For Dürckheim, the words “it is most especially the power of spiritual culture that determines the final outcome” must have been particularly attractive inasmuch as they paralleled his own völkisch understanding of religion. However, without knowledge of modern Japanese Buddhist history, it is unlikely that he would have understood the reference to “those who would exclude Buddhism while seeking to exalt the Spirit of Japan…” Here Yasutani refers to Shinto and Neo-Confucian-inspired criticism dating back to the late Edo period (1600-1867) that condemned Buddhism as a foreign, degenerate religion defiling a divine Japan properly headed by a “living (Shinto) god” (arahito-gami). The reference, of course, is to the emperor. As late as the 1930s Shinto and Neo-Confucian advocates maintained that Buddhism, an outdated foreign import, had nothing to offer modern Japanese society, a position Yasutani vehemently rejected.

Note, too, that the basis of the martial spirit of the Japanese people was described as the “Spirit of Japan” (Yamato-damashii). Yasutani clearly concurred with this belief though he asserted that it was Japanese Buddhism that made the cultivation of this ultranationalist and xenophobic spirit possible. Yasutani even turns Zen Master Dōgen, the 13th century founder of the Sōtō Zen sect in Japan, into the model of an Imperial subject:

The Spirit of Japan is, of course, unique to our country. It does not exist in either China or India. Neither is it to be found in Italy or Germany, let alone in the U.S., England and other countries….We all deeply believe, without the slightest doubt, that this spirit will be increasingly cultivated, trained, and enlarged until its brilliance fills the entire world. The most remarkable feature of the Spirit of Japan is the power derived from the great unity [of our people]. . . .

In the event one wishes to exalt the Spirit of Japan, it is imperative to utilize Japanese Buddhism. The reason for this is that as far as a nutrient for cultivation of the Spirit of Japan is concerned, I believe there is absolutely nothing superior to Japanese Buddhism. . . .That is to say, all the particulars [of the Spirit of Japan] are taught by Japanese Buddhism, including the great way of ‘no-self’ (muga) that consists of the fundamental duty of ‘extinguishing the self in order to serve the public [good]’ (messhi hōkō); the determination to transcend life and death in order to reverently sacrifice oneself for one’s sovereign; the belief in unlimited life as represented in the oath to die seven times over to repay [the debt of gratitude owed] one’s country; reverently assisting in the holy enterprise of bringing the eight corners of the world under one roof; and the valiant and devoted power required for the construction of the Pure Land on this earth.

Within Japanese Buddhism it is the Buddha Dharma of Zen Master Dōgen, having been directly inherited from Shākyamuni, that has emphasized the cultivation of the people’s spirit, for its central focus is on religious practice, especially the great duty of reverence for the emperor.86

Interestingly, among other nations, Yasutani excludes even wartime allies, Germany and Italy, from sharing in the uniquely Japanese “Spirit of Japan.” Given this, the reader might suspect Dürckheim would have been somewhat alienated by Yasutani’s words. In fact, as we have seen, the Nazis readily recognized that every Volk had their own unique spirit and culture. Thus, it was self-evident that the equally unique “German Spirit” (G. Deutscher Geist) propagated by the Nazis would have excluded the Spirit of Japan. Nevertheless, there was nothing to prevent the unique spirits of the three peoples from working closely together, not least of all against common enemies, while simultaneously learning and sharing with one another. Dürckheim mirrored this close collaboration.

By this point readers may be asking, “I thought Buddhism was a religion that forbids killing. Don’t both Buddhist laity and clerics undertake to abstain from taking life?” Yasutani did, in fact, recognize this as a problem but asserted nonetheless:

At this point the following question arises: What should the attitude of disciples of the Buddha, as Mahāyāna Bodhisattvas, be toward the first precept that forbids the taking of life? For example, what should be done in the case in which, in order to remove various evil influences and benefit society, it becomes necessary to deprive birds, insects, fish, etc. of their lives, or, on a larger scale, to sentence extremely evil and brutal persons to death, or for the nation to engage in total war?

Those who understand the spirit of the Mahāyāna precepts should be able to answer this question immediately. That is to say, of course one should kill, killing as many as possible. One should, fighting hard, kill everyone in the enemy army. The reason for this is that in order to carry [Buddhist] compassion and filial obedience through to perfection it is necessary to assist good and punish evil. However, in killing [the enemy] one should swallow one’s tears, bearing in mind the truth of killing yet not killing.

Failing to kill an evil man who ought to be killed, or destroying an enemy army that ought to be destroyed, would be to betray compassion and filial obedience, to break the precept forbidding the taking of life. This is a special characteristic of the Mahāyāna precepts.87

The assertion that failing to kill an “evil man” is to betray compassion is one of the more extraordinary of Yasutani’s claims. Yet, innumerable wartime Zen leaders echoed much of what Yasutani wrote above. There was, however, one area where he had less company. Yasutani was one of only a few Zen masters to integrate virulent anti-Semitism into his pro-war stance. The following are a few representative quotes, the first of which manages to combine Confucian social values, including its sexism, and anti-Semitism:

1. Everyone should act according to his position in society. Those who are in a superior position should take pity on those below, while those who are below should revere those who are above. Men should fulfill the Way of Men while women observe the Way of Women, making absolutely sure that there is not the slightest confusion between their respective roles. It is therefore necessary to thoroughly defeat the propaganda and strategy of the Jews. That is to say, we must clearly point out the fallacy of their evil ideas advocating liberty and equality, ideas that have dominated the world up to the present time.

2. Beginning in the Meiji period [1868-1912], perhaps because Japan was so busy importing Western material civilization, our precious Japanese Buddhism was discarded without a second thought. For this reason, Japanese Buddhism fell into a situation in which it was half dead and half alive, leaving Japanese education without a soul. The result was the almost total loss of the Spirit of Japan, for the general citizenry became fascinated with the ideas of liberty and equality as advocated by the scheming Jews, not to mention such things as individualism, money as almighty, and pleasure seeking. This in turn caused men of intelligence in recent years to strongly call for the promotion of the Spirit of Japan.