THIS TIME REALLY IS DIFFERENT

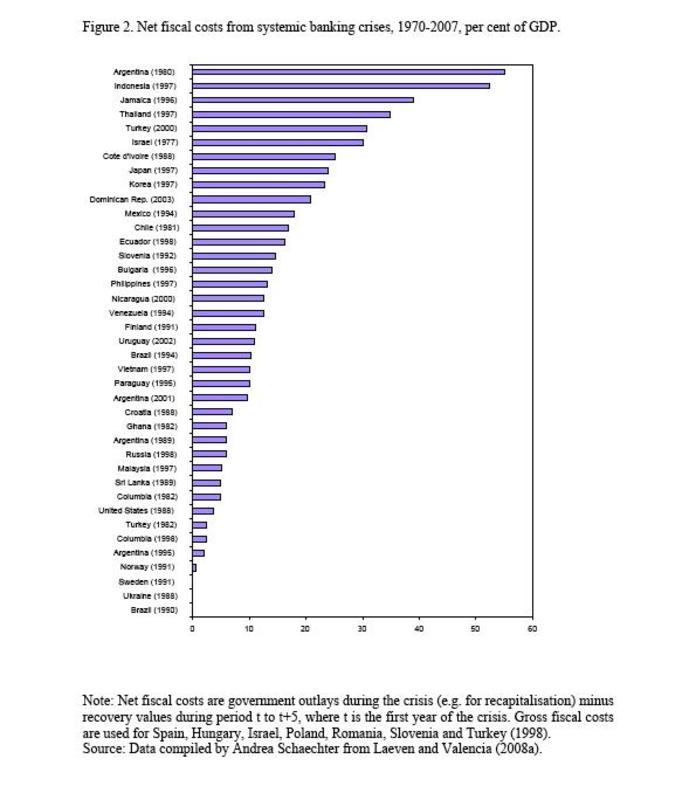

Reinhart and Rogoff’s influential book, This Time is Different (2009), argues that financial crises over the past eight centuries have had similar causes and consequences across diverse societies. The authors make an important empirical contribution to our knowledge of financial crises by showing that excessive borrowing, debt-fuelled asset values, and exuberance about ever-increasing prices are central elements in all of them. They also remind us that we tend to forget past crises, and hence dismantle regulatory and other safeguards implemented in their wake, leaving ourselves ripe for the next bubble. But they do not discuss the diverse ways in which governments have intervened in financial markets to deal with financial crises. Since these crises seem inevitable, and financial sectors are becoming increasingly large shares of national economies (Capelle-Blanchard and Tadjeddine 2010), it is important for social scientists to examine the politics of how they are managed.

The basic causes of financial crises may be similar, but there is a great diversity in responses to them in different national, historical and political contexts (Gourevitch 1986). Much of the global economy remains embroiled in the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, so it is still too early to attempt a full accounting of how various governments have intervened and the politics of their decisions. But the early 1990s financial crises in Sweden and Japan illustrate how and why interventions vary across advanced economies. The two crises had similar causes, including financial deregulation, credit expansion and massive asset bubbles. They also had similar fallout, with sharp declines in asset prices and massive increases in non-performing loans leading to a full-blown solvency crisis. The hallmark of a solvency crisis is that the burst bubble has left too great a burden of bad loans for the financial system to cope with on its own. Public-sector intervention is thus essential. But as we see in our two cases (as well as in the US and elsewhere at present), intervention must aim at the core of the crisis rather than just its symptoms, or risk a vast waste of public funds and economic opportunity through an impaired banking system.1

It is especially in the realm of effective intervention, that the Japanese and the Swedes diverged sharply in their crisis management. The Swedes quickly realized they were confronting a solvency crisis in major financial institutions. They organized a coalition in support of prompt, massive and equitable intervention. Their strategy stabilized the banking system and the larger economy and imposed comparatively low costs on the government budget. The intervention was very broad-based, and included the political opposition in decision-making and supervisory processes. The intervention was also transparent, reassuring domestic constituencies and foreign investors. And it was also deliberately structured to minimize moral hazards, by imposing objective rules and moving promptly to save the banking system rather than the bankers and shareholders. Where necessary, the bankers’ jobs and investors’ capital were made forfeit. Moreover, new and robust regulatory measures were swiftly adopted and a renovated institutional structure managed the aftermath.

In contrast, Japan’s policymakers chose to deal with their crisis as one of liquidity. They therefore extended a raft of fiscal, monetary and regulatory supports without fundamental restructuring of the financial sector, treating the problem as serious but temporary. The Japanese authorities’ policies of forbearance and “wait-and-see” largely denied or dissembled the very existence of a solvency crisis until the second half of the 1990s. Japan essentially gambled that hiding the bad-loan problem would prevent a panic and then be resolved by a return to growth and a recovery of asset values. The Japanese lost the gamble, as well as an enormous amount of wealth and economic opportunity.

The experience of the two countries thus affords a kind of natural experiment. Our central concern is not the technical intricacies of their two different strategies and their effects on the respective countries’ economic health. Our puzzle instead is precisely why these two countries responded so differently when faced with what appear to be quite similar financial crises.

In the next section, we take up approaches that might explain these two cases. We then follow that section with historical narratives of the Swedish and Japanese cases, showing both what was similar and what was different in each. In the final section, we summarize the empirical findings and suggest that the key variables are: a) the varying constraints and incentives facing policy makers given the different institutional frameworks, b) differences in elites’ “cognitive frameworks” or overall perspective on the prospect of their national political economies, and c) the degree of fiscal autonomy offered to elites given very different levels of public trust in national political institutions.

EXPLAINING VARIATION

Three distinct, but inter-related features of the Swedish and Japanese government’s responses to their respective crises require explanation: A) the quite different levels of transparency revealed by each government as the crisis developed; B) the different timing and aggressiveness of action; and C) the different willingness to directly invest public money. Our aim is to explain why the governments in Sweden and Japan responded so differently to their respective financial crises. Certainly, these dependent variables are inter-related, but in our view each feature can best be understood as a product of somewhat different causes. First, we follow many others in the comparative political economy literature and argue that institutional variation helps explain the different policy choices (Hall and Soskice, 2001; Thelen and Steinmo, 1992). At first glance, the two countries appear to be in close proximity among the “Varieties of Capitalism,” with strongly centralized political economies and longstanding traditions of cooperation among business, finance and government. Closer analysis, however, reveals important variations in the structure of political institutions. These variations are central for explaining why Swedish leaders were able to act across political boundaries and quickly reach a political consensus that allowed a newly elected minority government to decisively and transparently respond to crisis while Japanese leaders shied from responsibility and avoided tough choices. Second, we argue that recent historical experiences in the two countries shaped elite perceptions about the durability of the country’s politico-economic model and thus profoundly shaped the specific choices made – particularly whether to intervene immediately or wait. Finally, Swedish authorities operated with substantially greater autonomy from political and interest group influence than did Japanese authorities. Swedish elites were beneficiaries of what one might call a fund of political trust which they could call upon when asking citizens as well as interest groups to make short-term sacrifices in favor of the larger community’s long-term good. Japanese leaders, by contrast, lacked a foundation of public trust for dealing comprehensively with the financial crisis. In the following sections, we elaborate these arguments to sketch the analytical framework.

Institutions

Why was Swedish crisis management transparent whereas Japanese policymakers chose to hide the facts? We argue that a major explanatory factor is found in the institutionalized relationship among key policy actors involved in the decision making process. In both Sweden and Japan, the central actors in policymaking and regulation have close-knit relations (Bergh, 2010; Katz, 2008; Lindvert, 2008; Swenson, 2002; Vogel, 2006). In both countries the political, economic and bureaucratic elite is relatively small and generally have very similar social and educational backgrounds. These elites know each other and have ample accumulated experience of cooperatively solving policy puzzles. In each case, a kind of cooperative neo-corporatism evolved. However, the institutions in which they cooperated evolved in different directions. We will show that the regulatory environment in Japan developed what might be described as an “Iron Triangle” that eventually became a collusive structure with non-transparent interaction among the Ministry of Finance, the Bank of Japan and individual financial institutions. Sweden too has a long history of elite central authority with a relatively small group of men who know each other and rely on each other’s confidence (Lindquist, 1980). Yet Sweden developed a prudent, objective policymaking system that facilitated cooperation without regulators becoming captive of the industry.

Sweden has long been known for its “Politics of Compromise” (Rustow, 1955), in which it built mechanisms for including diverse interests in the decision making process – even interests or parties which were not formally connected to the ruling coalition. One of the key consequences of this inclusion was the development of a tradition of openness, or transparency. In contrast, while Japanese regulators and bankers also had long-standing relationships, there was almost no tradition of bringing outside interests into the decision-making process. Pempel and Tsunewaka aptly described the Japanese case in this regard as Corporatism without Labor (Pempel and Tsunewaka, 1979). For many years this system was admired for its decisiveness and ability to make difficult policy choices (Pempel, 1982; Thurow, 1992; Wolferen, 1990). We show that in the case of banking regulation, at least, the system had developed into a collusive structure in which policy makers opted to conceal the scope of their insolvency problem with policy measures that lacked transparency and protected vested interests.

Perceptions

The second major divergence in these countries’ crisis management was the timing of action. Whereas, Swedish policymakers intervened immediately and stringently, Japanese policymakers opted for a wait and see approach. Our analysis shows that the central explanation for this variance is found in the cognitive framework of elites with respect to the health and viability of their national economic models. We suggest that “history matters” (Pierson, 2004) because it shaped in different ways the perceptions of key policymakers in the two countries. Japanese policymakers met the financial turbulence with undue optimism and perceived it as a temporary shock. To be fair, they had good reason to be optimistic. At the end of the 1980s, the Japanese economy was prosperous and was widely deemed a reference model in global political economy (Vogel 1979, Zysman 1983). The successful management of the oil shocks and other crises in the 1970s furthered strengthened Japanese policymakers’ confidence in their political economy model, especially when most of the European welfare states seemed hopelessly sclerotic (Kato and Rothstein 2006). Furthermore, no Japanese financial institutions went bankrupt in the postwar period. The view of Swedish elites differed markedly. The days when Sweden had been held up as a model for the world seemed long gone by the early 1990s. Moreover, Swedish elites across the political spectrum had come to doubt the efficiency and even efficacy of the system. Instead, a consensus appeared to be emerging that Sweden had suffered deep structural problems for well over a decade: The symbiotic relations between Sweden’s labor and business had begun to erode; productivity was lagging; and wage push inflation forced Swedish authorities to repeatedly devalue the Swedish Krona, which in the end could only temporarily strengthen Swedish export competitiveness.

We find a purely structural approach that focuses exclusively on the ways in which formal political institutions shape the strategic behavior of actors and interests to be insufficient. We show in the following analysis that the particular choices made in Sweden and Japan simply cannot be ‘read off’ institutional incentives. Actors’ choices were instead framed by their perceptions and, indeed, their particular histories. The considerable literature that has sought to explain Japanese forbearance in institutionalized principal-agent terms has certainly elucidated many useful points (Muramatsu and Scheiner 2007, Rosenbluth and Thies 2001). But the comparative analysis we offer demonstrates that actors’ interpretations of past events and expectations about the future in the context of uncertainty (Knight and Sened, 1995) had profound consequences for the actual choices taken.

In sum, confronted by crises in their financial markets, policymakers’ responses in these two countries were conditioned by their divergent perceptions of their national economies. We are not arguing that these perceptions were accurate. Instead, our point is that the ways in which policymakers viewed recent history cognitively framed the choices available in each case. Japanese policymakers were confident of their growth model and banking system. They generally expected a prompt recovery and took a wait-and-see approach, coping with bank failures via ad hoc solutions that conformed to and reproduced the institutional status quo. It took them seven years to collectively recognize the scope of the problem and begin adopting comprehensive measures adequate to a solvency crisis. In contrast, Swedish policymakers believed their economy was in trouble before the crisis hit and were quick to grasp the scale of their financial meltdown. In short, perceptions about the recent evolution of their political economy models shaped the actions taken by the policymakers in Sweden and Japan.

Trust

Lastly, differential political constraints on the use of public money were important in shaping crisis management. Policymakers in Sweden and Japan did not have the same liberty in using public money to solve the problems in the financial system. Even when Japanese policymakers realized they needed to rescue insolvent banks, they were constrained by public opposition to using public money. In contrast, the Swedish public supported the use of public funds to resolve the insolvency in the financial system. The key difference here was the degree of trust in public institutions. Thoroughly analyzing the underlying causes of this divergence in trust is beyond the scope of this paper. But we believe that Sweden’s transparent and cooperative institutions – and of course the political and economic outcomes associated with these institutions – encouraged public trust in government. In contrast, Japan’s collusive institutions and lack of transparency led the public to believe that decisions are usually taken for the elite. In this regard, Kato and Rothstein (2006) suggest that the universal character of the welfare state in Sweden, with its equitable distribution of resources that are independent of particular interests, provides strong support to political institutions and government spending. But in Japan, where government funds have often been used to placate specific interests, the public is generally skeptical about the use of public funds. We believe that this background helps explain why the Swedish public supported the use of public money while the Japanese public opposed it. Lack of trust limited the capacity of policy makers to use public funds and resolve the financial crisis.

The contrast is indeed ironic: in Sweden the center-right Moderate Party – which was forced to form a minority government because no one could pull together a majority coalition – was able to impose costs and allocate public monies with great authority and precision. Yet in Japan, the LDP continued to rule the system after roughly 40 years of continuous hold on the reigns of power, yet was in part inhibited from using public funds to address the financial sector’s grave crisis by fear of public backlash.

Students of partisanship commonly believe that major differences in policy outcomes can be explained by the presence of left-wing and right-wing parties in office. The political party/partisanship argument thus resembles the interest-group argument in those business associations, labor unions, and other groups that are generally allied with specific political parties.2 But this approach, too, is not especially relevant to the comparative politics of Swedish and Japanese financial crisis management because both countries were largely governed from the centre-right at the time.3 Sweden’s center-right coalition responded quickly and effectively to the solvency crisis, whereas the similarly center-right Liberal Democratic Party in Japan was hesitant to disclose its scope and use public money to resolve it. And in the wake of that, social democratic governments in Sweden were able to reduce the budget deficit. But Japan’s LDP governments continued with forbearance and ratcheted up the budget deficit (Kato and Rothstein 2006). This is not a story of party labels determining policy outcomes.

In sum, the following analysis clearly fits into the institutionalist tradition within political science. Certainly the structure of the extant political institutions shaped actors’ incentives and constraints. But in our analysis a purely structural account is inadequate. In order to more fully understand why specific policy choices are made, one also needs to investigate policymakers’ perceptions and the cognitive frames that shape choices and preferences. This is one important way in which history matters. Additionally, we submit that the history of government action in the past frames citizen’s perceptions of government’s legitimacy today. The consequence is that some states may have more autonomy to act in difficult times than do others. The narratives that follow will demonstrate two examples.

SWEDISH FINANCIAL CRISIS AND ITS MANAGEMENT

Background

By the mid 1980s Sweden had the largest and most extensive welfare state as well as the heaviest tax burden in the world. By 1987, public spending had grown to nearly 60 percent of GDP and taxes had reached 54% of GDP. In the context of an increasingly competitive and open world economy, these facts presented Swedish policy makers with acute dilemmas. The Ministry of Finance was dominated by what must be called “liberals” in the Social Democratic Party context. These officials were acutely attentive to the Swedish economy’s vulnerability to competitive pressures, and pressed for a series of deregulatory reforms designed to improve the position of Swedish enterprises in international competition. Led by Minister of Finance, Kjell Olof Feldt, ministry elites concluded that the pattern of inflationary policies followed by currency adjustments could not be sustained in an increasingly fluid and open financial world.

Under Feldt and his team’s stewardship, Sweden began to introduce a series of regulatory reforms in the early 1980s. These deregulatory moves were intended to increase competitiveness within the Swedish financial system which was seen as insufficiently dynamic to meet the needs of an increasingly flexible and dynamic world economy (Feldt, 1991). But as in many countries, Swedish policymakers and the financial community did not fully appreciate the extent to which financial deregulation brought new systemic risks until the banking and currency crises hit the Swedish economy in the early 1990s.

Prior to the 1980s, Sweden’s financial system had been strongly regulated with interest rate ceilings, reserve requirements, taxation on bank issues of certificates, as well as strict controls on international capital movements. Given the very strict regulations before the 1980s, banking was more like administration than business. Virtually everything was prescribed, including whom you could lend to, what interest rates could be charged, and capital requirements. Most large loans had to be approved by government regulators. Beginning in the mid-1980s, however, restrictions were gradually eliminated to accord with international financial markets and domestic concerns such as financing large budget deficits (Englund 1999; Jonung 2009). The changes in the financial system included eliminating the ceilings on interest rates as well as the removal of taxation on issuance of bank certificates and turnover at the stock exchange. The removal of interest rate ceilings allowed financial institutions to operate liberally and encouraged risk-taking. Furthermore, the tax system with full deductibility of interest payments encouraged excessive borrowing by effectively reducing interest rates to zero or even into negative territory. Finally, restrictions on international transactions were gradually abolished and foreigners were allowed to buy Swedish shares, and the subsidiaries of foreign banks were permitted to operate in Swedish financial markets (Drees and Pazarbasioglu 1998).

Along with these regulatory changes came a gradual evolution in the structure of the banking industry itself. Historically, the Swedish financial industry was divided between two main large private commercial banks, HandelsBank, and Stockholms Enkilda Bank (SEB). There was also Nordbank, which was a quasi-public bank which had been essentially knit together from a variety of different institutions over the years including the Postal Savings Bank (PK). Also, a large number of smaller local savings institutions were found in almost all of the smaller towns and villages across Sweden. These institutions traditionally focused on local loans.

Swedish banks, like most banks around the world, had once been largely conservative institutions with close and detailed knowledge of the individuals and enterprises in which they invested or lent money. Each of these different institutions tended to focus on different segments in the Swedish market: Nordbanken dominated public investment and projects, Wallenberg’s SEB dominated large investments in traditional industries, while Handelsbank focused on high profit investments often of smaller volume. As the market was deregulated in the 1980s, opportunities for risk-taking increased. Competition within the traditionally rather staid industry increased dramatically and new entrants to the financial markets pushed the industry to compete for borrowers as well as investment products in ways quite new for Swedish capital. One of the new entrants to the market, GotaBank, (which grew out of successive mergers of smaller banks) became especially active in commercial real estate and also began selling sophisticated investment instruments. The management style of Swedish banks also changed. Some of the changes came from new managers; others from the fact that formerly conservative bankers could now invest outside their local communities. Several economists and industrialists had criticized the traditional financial institutions for not taking enough risk, thereby helping stifling Swedish economic performance. Banking was quickly changing from being something like a service industry to much more of a center for generating profits. “I remember one time in particular when I was asked by the director of a local savings and loan from a small town in rural Sweden to buy three apartment buildings in Hamburg, Germany.” Enrique Rodriquez, a director of the Swedish Savings and Loan Association recalled. “Hamburg was gaining the reputation as a booming market, and the bank director didn’t want to be left out.” (Rodriquez, interview, February 25, 2011).

These regulatory changes regarding the quantities, interest rates, and domestic and international transactions led to fundamental change in the incentive structure within the industry. First, new institutions with little traditional banking experience began to enter the finance marketplace. Whereas banking had traditionally been a quite stable, if not conservative industry, new players prioritized generating short-term profits. Second, and partially in response, deregulation encouraged even established lenders and borrowers to take financial risks. The financial institutions began to take greater risks in distributing loans to extend their market share. Indeed, at first at least, deregulation was a boon to the Swedish economy. Combined with fiscal and tax policy incentives favoring real estate, the last years of the years of the decade witnessed an enormous expansion in lending, investment and asset values.

On the consumer side, negative after-tax real interest rates encouraged borrowers to consume or invest in real estate markets with the help of loans distributed by these financial institutions. As such, the deregulation of the financial markets stimulated credit expansion, rise in private sector borrowing rates, rise in asset prices and rising consumption. Englund reports, for example, that lending by private actors increased by 136 per cent between 1986 and 1990 (1999: 84). In the same period, private sector debt rose from 85 to 135 per cent of GDP and real estate prices increased by 125 per cent (Backstrom 1997: 131). These trends were accompanied by increasing household consumption of 4 per cent each year (Englund 1999: 84-5). Regulatory changes in the second half of the 1980s favored the expansion of financial markets, private sector borrowing, rising asset prices and consumption. Combined, these conditions formed the dynamics of a massive asset bubble in the second half of the 1980s in Sweden.

Figure 1. Real Estate Bubble in Sweden. Source: Statistics Sweden. *Real estate price index for one- or two-dwelling buildings for permanent living (1981=1) |

In the late 1980s, it became increasingly evident that the economy was over-heated. In 1989, the unemployment rate declined to 1.4 per cent associated with doubled stock market and real estate prices. As the figure above shows, when the price bubble finally burst asset prices declined enormously, placing Swedish banks under intense pressure. The construction and real estate stock price index declined by 25 per cent in 1989 (Englund 1989: 89). The decline was partly due to a rise in international interest rates after German unification. Also, changes in tax policy in 1990-91, which reduced the previous tax deductibility option and the possibility to borrow with zero effective rates, negatively impacted asset prices as borrowing became less attractive for Swedish households (Jonung 2009: 4). As expected, the decline in real asset prices was reflected in the increasing frequency of non-performing loans. In 1990, Nyckelin, one of the non-bank finance companies that had recently entered the market offering increasingly risky real-estate loans, found itself in trouble, unable to roll-over its maturing debt. The problems in non-bank finance institutions quickly spread throughout the banking system. In autumn 1991, two of Sweden’s large and more traditional financial institutions, Första Sparbanken and Nordbanken, faced solvency problems and in spring 1992 Götabanken faced bankruptcy.4

Sweden’s banking crisis coincided with the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM) crisis in the summer of 1992. In what proved to be a rather bad choice, Swedish authorities decided to protect the pegged exchange rate mechanism and the value of the kroner (SEK) instead of moving to a floating exchange regime.5 On 16 and 17 September, Britain and Italy left the ERM. On the same day, in order defend the SEK, the Riksbank raised over-night interest rates up to 500 per cent and provided liquidity to the financial markets. However, the choice to protect SEK inevitably increased interest rates and the vulnerability of the Swedish financial system against speculative shocks. Insistence on retaining a pegged rate deteriorated international borrowing requirements of Swedish banks forcing higher interest rates, which put even further pressure on the financial system. On November 19, Swedish authorities let the SEK float, whereupon it depreciated 20 per cent by the end of the year. The depreciation adversely affected balance sheets of the financial institutions, which were heavily borrowed in foreign currencies but distributed funds in SEK. In short, both the defense and depreciation of the SEK increased the damage of banking crisis in Sweden.

The damage of the combined banking and currency crises to the macroeconomic fundamentals resulted in a contraction in GDP, as well as a rise in aggregate unemployment and public sector deficit. Between 1990 and 1993, GDP dropped by 6 per cent, aggregate unemployment increased from 3 to 10 per cent and public sector deficit rose to 12 per cent (Backstrom 1997, Englund 1999).

Figure 2. Macroeconomic Fundamentals in Sweden (in percentages). Source: IMF |

In sum, if one strips away the details of the story narrated above, we can see that the Swedish financial crisis followed a pattern highly analogous to other similar crises seen around the world and over time – just as Reinhard and Rogoff have suggested. What these authors do not examine, however, is the ways in which different countries respond to these crises and the differential consequences of the responses. We submit that what is most important about the Swedish case was not the origins of financial crisis itself, but its management. The Swedish case is particularly interesting given the country’s remarkable success in efficiently managing the crisis after being hit.

Sweden’s Response to Crisis

On September 15, 1991 the Swedish electorate moved to the right. For only the second time since the 1930s, the Social Democratic Party (SAP) was unable to form a government. There have been multiple explanations for the decline in the SAP’s vote share, including the widespread perception that the Socialists were unable to decide amongst themselves what direction the country should take, as well as growing unease about the increasing numbers of immigrants in the country. For the first time in Swedish modern history, a new ‘right wing’ party, New Democracy, received enough votes to enter the parliament. This unusual turn of events put the Swedes in a position in which no one could form a majority government without inclusion of this new, ostensibly racist, party. Eventually, the Moderate Party, led by Carl Bildt formed a minority government despite the fact it had only received 80 mandates and was only the third largest party in the Riksdag. Needless to say, this was hardly an auspicious beginning for a government that was about to face one of the most dramatic economic crises in modern history.

Almost immediately, the new government faced its first major crisis. In late 1991, the burst of the asset bubble had already started to affect balance sheets of major financial institutions. In autumn 1991, Första Sparbanken and Nordbanken had serious solvency problems. The situation deteriorated for most financial institutions throughout 1992. But the new government quickly diagnosed the problems. In Spring 1992, the Swedish government injected capital in Första Sparbanken, but let insolvent Götabanken go bankrupt. As will be explained in detail, this selective intervention at this stage played a key role in the success of the Swedish crisis resolution. However, problems in the property markets and financial institutions became more severe with the ERM crisis and international financial instability in the summer of 1992. In order to provide stability, the government announced blanket guarantees in September with the support of the political opposition. In short, the newly elected government encountered a severe crisis but successfully identified the underlying problems and took the necessary step to overcome the crises.

The new government’s first response was to bring together financial experts from across the financial and political spectrum. It may well have been reasonable to expect these political leaders to try to run from the impending crisis, or to blame the economies problems on the past government. Remarkably, in our view, they instead sought the political support of the main opposition parties. After securing this support the government was able to decisively intervene in financial markets, inject liquidity, provide guarantees for doubtful loans and ultimately steer the recovery process in a transparent way. In the end, the recovery in the banking system and macro economy was quick and the costs to the state were relatively minimal.

Soon after the problems in the financial system became apparent, the government swiftly seized control over several of the most troubled institutions, injecting capital and providing blanket guarantees to those holding debt. Importantly, however, they did not attempt to bail out the investors or the financial institutions stockholders. Bo Lundgren, Minister for Economic and Fiscal Affairs at the time put the issue simply: “I’d rather get equity so that there is some upside for the taxpayer.” “For every krona we put into the bank, we wanted the same influence,” Mr. Lundgren said. “That ensured that we did not have to go into certain banks at all.” Urban Backstrom, another senior official in the Ministry of Finance at the time, recalled similarly that the thinking in the government was that it would be a political and economic mistake to “[Put] taxpayers on the hook without [giving them] anything in return… The public will not support a plan if you leave the former shareholders with anything” (Dougherty, 2008).

The still new government injected equity capital directly into Nordbanken and provided blanket guarantees to Första Sparbanken. When the situation in the Första worsened in the spring of 1992, the government injected 1.3 billion SEK in the equity capital of Första (Englund 1999: 91). At the same time, they decided not to inject new equity into banks such as Gota that had virtually no prospect to recover and become profitable in the medium term. Gota had been by the most aggressive new player in the market and Lundgren and his team felt that this bank was essentially beyond redemption. Gotabank eventually fell into the hands of SEB as it collapsed financially since SEB had secured many of Gota’s loans. Bo Lundgren, who had been charged by Prime Minister Bildt as the central person to handle the crisis, gathered his key advisors as well as the leader of the Social Democratic Party and, in his words, “put together a package.” When asked whether he felt much pressure from some of the interests who were to lose, he stated bluntly. “No one, nobody in government, even approached me like that.” His response is worth quoting at length:

I remember we had a meeting with Kurt G. Olssen, who was the chairman of SEB at the time. We found out that when Gota was going bust in September, before this package, the shares of Gota Bank were put in collateral by their parent company, Gota AB. So SEB was holding the shares of Gota AB. And Gota AB was going bust. We wanted to handle the situation and avoid further losses. When I talked to SEB they said, “Well, if you want this so quickly, it must be worth something.” So, I called Olssen to come up, together with the CEO, and I said, “I’m not paying anything. Well, perhaps 1 kronor.” Then he started to say that his shareholders would take a great loss. So, I told him, “That’s not my problem.”

Later Olssen approached Lundgren and asked whether something “couldn’t be worked out.” Lundgren again denied his request. In Lundgren’s view, to comply would be to violate the public trust and undermine his goal of managing the crisis in a transparent way and protecting the value of public funds.

On 24 September 1992, just two weeks after the currency crash, government – with the support of members of the political opposition – issued a press release declaring that it would provide blanket guarantees for the entire financial system to protect the security of households, enterprises and other claim holders. The blanket guarantee for the financial system prevented a major bank run and restored the confidence of international investors (Jonung 2009: 8). In December 1992, the Riksdag (Swedish parliament) approved the decisions taken in the press declaration and decided to establish a new institution with open-ended funding to manage the crisis. In May 1993, the Bank Support Authority (Bankstödnamnen) was formally established by parliamentary decision. This new unit had considerable autonomy from the Riksbank and the Financial Supervisory Authority, but had these institutions’ organizational support.

In addition to investing nearly 4% of GDP in saving the banks, the government also chose to set up a new institutional structure to help manage the crisis. Two quasi-public holding companies were established, Securum and Retriva, as asset management companies (AMCs) to manage bad loans of Göta and Nordbanken (Ergungor 2007).

The Ministry of Economic Affairs noted that extant Swedish law gave failing financial institutions six months to consolidate before the government could take them over. They quickly understood that a protracted crisis precluded the kind of decisive government action that was essential. Their solution was to go to Johan Munck, then President of the Swedish High Court, and ask him to draft a new law that would give the government authority to seize a bank without a waiting period. Munck did so, and with the support of the Social Democrats they pushed the new law through parliament under rules that speeded up the legislative procedure. The bill became law with the support of all the main political parties and was passed in just three weeks. From that point forward, financial institutions understood that the government had both the tools and the intent to take whatever measures were necessary to defend the economy, and not just the banks.

By virtually all accounts, management of the financial crisis in Sweden was successful in terms of its quick solution to the problems of the banking sector, with low cost and successful recovery of macroeconomic fundamentals. Why did Sweden’s crisis management succeed?.

First, the government incorporated the political opposition in the decision making process and in supervisory bodies and boards of newly overtaken financial institutions. Sweden had had little experience with minority governments, but it had a long tradition of coalition governments and of neo-corporatist decision making in which opposition parties and interests were brought together for discussions as new policy initiatives were being considered. In this case, the Social Democrats were out of office but the Conservative government chose to follow tradition and provide for an inclusive process. For instance, the September 1992 press release was co-prepared and presented by the government and the Social Democratic opposition. Thus the Swedish authorities made it clear that there is no political uncertainty concerning the commitments (Ergungor 2007). Similarly, political opposition was represented in the boards of Bank Supervisory Authority.

Second, from the beginning, management of the crisis was handled in a transparent way to enhance confidence among domestic and international investors. Transparency involved disclosing information about the extent and nature of the problems. From the outset, the Swedish government disclosed expected loan losses and assigned realistic values for asset-related losses instead of deferring reports of losses as long as long as legally possible (Ingves & Lind 1996). All banks under the control of the Bank Support Authority that had accepted any government help were required to disclose all their books to the Authority. In parallel, cabinet ministers and officials put strong emphasis on relating the central aspects of the management program to international investors by constantly visiting financial centers. These efforts enhanced confidence in the system and prevented a possible financial outflow when Swedish firms were heavily dependent on foreign funds to roll over their short-term debt.

It is important to understand that the perception that Sweden was in trouble economically – and that the current crisis was but the tip of an iceberg – was widely held by elites in all the main political parties. Even key Social Democratic party leaders were increasingly persuaded that the traditional model of very high marginal taxes (over 80% on top earners) and public spending in excess of 60% of GDP was no longer sustainable in a globalizing economy. Though Finance Minister Kjell Olof Feldt had lost his position even before the election, his influence on ideas in the party can scarcely be over-estimated. He and his advisors argued vociferously that in order to maintain an egalitarian welfare state in the 21st century, significant policy changes were needed (Feldt, 1991; Steinmo, 1989, 2010). Thus, in short, part of the explanation for Sweden’s remarkable political success has to do with the moderate government’s willingness to compromise and include opposition leaders. But an equally important part of the story is the fact that the opposition Social Democrats, in particular, were willing to cooperate. Virtually all relevant actors understood that this crisis had both deep roots and a long tail.

The government was also acutely aware of the dangers of “moral hazard.” Consequentially, the government made clear to all participants that its rationale was to save banking system and not the bankers or the shareholders. The BSA’s financial support meant equal reduction in the share capital of the bank owners. In order to set objective criteria for capital injection, a common framework for government intervention was built. According to this framework, the financial institutions were divided into three groups based on their level of capital equity and their prospects of recovery in the short and medium term. Lundgren stated the government’s attitude thus: “A market economy means that you have to accept risk. If you as shareholder can’t manage a company through the management you accept or choose, then you have to take the loss. That is a market economy. Otherwise a market economy won’t work” (Interview, Feb 24, 2011). Based on this rationale, the financial institutions with reasonable recovery prospects received injections of equity capital from the central government. But others deemed doomed to fail were allowed to go bankrupt and their properties were transferred to asset-management companies. This objective framework further contributed to the legitimacy and transparency of the crisis management process in Sweden. In short, policy elites both depended on and sought to reinforce citizens’ trust in their political institutions and public authorities.

Fourth, the Swedes were adept at establishing new institutions to overcome the crisis. The establishment of the BSA was crucial in an environment in which the Ministry of Finance did not have the necessary expertise and direct involvement of the Riksbank and the Financial Supervisory Authority. With strong legal backing and the support of the aforementioned institutions, the BSA was quick to prevent the adverse effects of the crisis and establish the new rules of crisis management. Also, it was important that the December 1992 Riksdag decision granted BSA financial support without any legal limitations. Similarly, the introduction of Securum and Retriva as asset management companies for Götabanken and Nordbanken was a practical solution for non-performing loans backed by real estate properties. Swedish policy makers recognized the necessity of particular expertise for the legal and technical complications of real estate market and transferred the properties of these financial institutions to Securum and Retriva (Jonung 2009: 11, Ergungor 2007). It should also be noted that Swedish authorities were aware of their dual job of repairing the banking system and providing stability for the macro-economy. The depreciation of the SEK constituted the main driving force behind the export-oriented recovery. Similarly, fiscal expansion acted as an automatic stabilizer for the Swedish economy, where government had large budget deficits between 1991 and 1997 (Jonung 2009: 12). Considering all of these elements, there can be no gainsaying the factthat the Swedish authorities were remarkably successful in managing the financial crisis in the early 1990s.

JAPANESE FINANCIAL CRISIS AND ITS (MIS)MANAGEMENT

Background

Japan’s economic crisis in the early 1990s had similar roots and followed a remarkably similar pattern to that of Sweden:A sustained period of financial deregulation and loose monetary policy contributed to a steep rise in Japanese asset prices, especially real estate.The asset bubble burst, leaving Japanese banks and other financial institutions sitting on a swelling mountain of non-performing loans. This was the core of the financial crisis, and rectifying it required fast, large-scale government action to separate the banks from their bad loans and return the financial sector to health. Quite unlike the Swedish authorities, however, the majority of Japanese authorities were initially slow to recognize the scale of the unfolding crisis and then found themselves unable to muster a consensus on comprehensive action. The inherent defects of collusive governance then took an increasing toll. Policy turned instead to covering up unpleasantrealities for the time being, to avoid the risk of a run on the banks, while hoping that rapid economic recovery would lift asset prices and thereby bail out the banking industry.As asset prices dropped further and banks’ liabilities swelled, however, the government found itself compelled to increase its fiscal and monetary-policy supports. In sharp contrast to the Swedish pattern discussed above, the Japanese government repeatedly opted for non-transparent and non-systemic measures. The use of ad hoc measures designed to perpetuate the status quo, rather than biting the bullet of comprehensive reform, failed to bolster confidence in the financial system and reinvigorate the real economy (Kaneko, 2002).

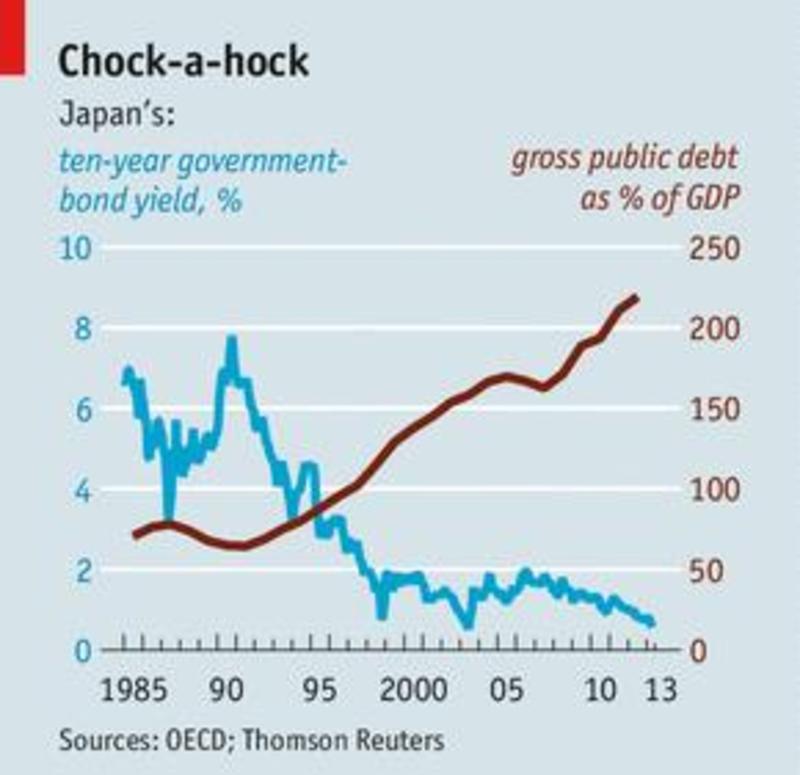

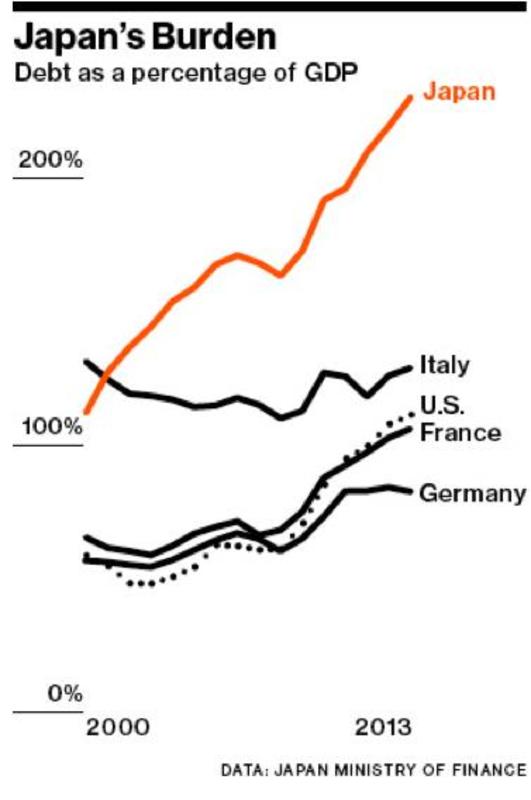

Where Swedish authorities deliberately dealt with the moral hazard problem, and contained their crisis, Japanese post-bubble financial policy has become the advanced countries’ textbook study in the enormous costs of dithering in defense of vested interests. Two “lost” decades have seen subpar economic growth while Japan’s gross public-sector debt, propelled by the financial chaos and its fallout, has ballooned from 60% of GDP in 1991 to over 200% of GDP in 2014. The latter level of gross debt has hitherto been seen only in wartime. And it has clearly not yet peaked, as Japan in FY 2014 is funding over 40% of its general budget from red ink.

Industrial, not Social Policy

Japan’s postwar financial system was a tightly regulated structure deployed to direct the flow of investment capital. Its core comprised strict controls on interest rates, cross-border financial transactions, the location of bank branches, non-price competition among the banks, separated categories of banking, and a variety of other mechanisms. Distinct from even its largely unregulated prewar predecessor, the Japanese financial sector became a conduit focused on financing rapid economic growth.6And in sharp contrast to Sweden and other European welfare states, the postwar Japanese state saw its mission as constructing a heavy-industry centered export machine. The state was not there to lay the foundations of a comprehensive welfare state to defend the citizens against the vagaries of market capitalism (Amyx, 2004; Estevez-Abe, 2008).

A keystone of the so-called “Japanese Model” was the stability in the financial system tuned to ensure a healthy flow of bank loans for corporate investment (Zysman 1983, Schaede 1996). Rather than constructing a public welfare state to insure individuals against economic risk, this system relied on firms to provide benefits and jobs – even during economic downturns (Steinmo 2010). Thus financial stability, was in many ways part of Japan’s unusual “welfare state.” (Estevez-Abe, 2008) One of the tools used to maintain stability was powerful administrative guidance over financial firms. This was not a top-down, command style of supervision. Postwar Japanese financial regulation centered on cooperation between government officials, such as the bureaus of the Ministry of Finance as well as the Bank of Japan, and the financial community. These actors routinely exchanged personnel as well as consulted within an array of committees.

The regulatory structure maintained a hierarchy between larger and smaller banks as well as among the various sectors of financial activity, such as financing of large versus small and medium-sized firms. A “convoy system” was developed, wherein each sector of the financial industry proceeded at the pace of its least-competitive firm (Seabrook, 2006). It was a dense network of trust-based relations among the regulators and their respective clients in the various sectors of industry (Suzuki 2010). The convoy systemalso afforded informal protection of bank deposits coordinated by the regulatory authorities’ administrative guidance. This meant that there was largely an implicit rather than explicit safety net for the financial sector. The state stood in the background as the guarantor of last resort with the public sector extending emergency liquidity to troubled banks and then generally arranging a merger of the failed institution with larger, healthy banks in the face of financial crisis.7Interest rate ceilings were also used to ensure that financial firms did not compete on price while enjoying predictable and quite substantial profit margins.8Another characteristic feature of Japanese finance was the “main bank” system wherein business conglomerates (keiretsu) were centered on large banks. These banks were the primary (but not exclusive) conduit to funnel capital into the firms within the conglomerate. The main banks also held shares in keiretsu firms, shares that were part of the banks’ regulatory capital base.This key strategic position gave main banks powerful incentives to discipline themselves as well as oversee the credit conditions of their major borrowers (Aoki, 1994, Kaji 2010).

In practice, much of the oversight of the financial sectorwas ad hoc and handled through special relationships between the Ministry of Finance and Bank of Japan bureaucrats and the personnel of financial institutions. In return for special treatment and implicit guarantees, financial institutions were expected to finance investment in accordance with national developmental strategy. Over time, this interaction evolved into a collusive type of regulation, with ample opportunities for rent-seeking at the expense of the larger public interest (Kaji 2010).

The initial moves toward deregulation of theJapanese financial system began inthe late 1970s, but it was not until the 1980s that they accelerated appreciably. Much as in Sweden, capital controls, were progressively lifted, as the 1980s saw the gradual removal of interest rate ceilings and restrictions on foreign and other financial transactions. The banks were increasingly able to compete among themselves and lend to an increasingly diverse customer base. One measure of the banks’ growing base of customers outside of traditional corporate networks is thatin 1984, loans to real-estate were only 27% of the volume to the manufacturing sector, but had swollen to 74% at the end of 1991(Noguchi and Yamamura, 1996: 59).

The 1980s thus saw increasing divergence between theory and practice, so to speak, in Japan’s financial markets. The postwar convoy system’s opaque and informal, negotiated mechanisms of banking supervision and crisis management remained very much the spine of the Japanese financial economy. Yet the real role of finance was swiftly expanding and evolving around it, and the regulatory sinews that kept the system coherent were being cut. The financial system was entering a new realm of risk without explicit rules and robust institutions to avert systemic failure or intervene effectively should it erupt.

In the 1980s, the Japanese banks’ increasingly powerful incentives to extend credit to realtors, households and small businesses for often speculative investment saw credit pour, in particular, into real estate markets.9This was similar to and almost contemporaneous with what went on in Sweden. Richard Katz (2008) reports that from 1981 to 1991, commercial land prices in Japan’s six biggest cities rose by 500 per cent. This bubble was further encouraged by inheritance and corporate income taxes favoring investment in land (Fukao 2009). And driving it all forward was an exuberant confidence that real estate prices would continue to increase. All these factors encouraged new investors to join in and further amplified Japanese banks’ appetite to make yet more such loans.

But the speculative bubble and overheated economy flamed out in 1990. The Nikkei stock exchange index reached its peak on December 29, 1989, at an astounding level of YEN 38,915. The Nikkei’s asset value was approximately 44% of the world’s equity market capitalization at the time (Stone and Ziemba, 1993, 149). In the spring of 1989, the Bank of Japan began trying to deflate the enormous bubble through increasing the discount rate, which they raised from its May, 1989 level of 2.5% to 6% by the end of August 1990. These and other policies were effective, driving the Nikkei down to YEN 26,000 by Aug 30, 1990.10 It was, however, too little too late.

The burst of the bubble put an end to the “miracle economy” of the preceding decades. The 1990s became a decade of business bankruptcies, almost zero growth, imbalances in the banking sector and rising fiscal deficits (Hart-Landsberg and Burkett 2003: 339). Annual average real GDP growth of 3.8 percent in the 1980s fell to 1.6 percent in the 1990s and fiscal deficits increased. Increases in unemployment were, however, gradual rather than abrupt. And they appeared in the second half of the 1990s rather than as an immediate consequence of the bubble’s collapse and the shocks that the collapse delivered to the real economy. All the indices contrast with Japan’s previous decade, as well as with the latter 1990s outcomes in Sweden. Japan’s expansion of public-sector debt is, of course, a classic feature seen in the wake of financial crises, as the private sector deleverages and the public sector takes up the slack.But Japan’s flood of fiscal red ink seems endless. Indeed, it continues into the present, two decades after the fact, the protracted financial crisis having compounded other problems and weakened the economy’s capacity to renew itself and return to self-sustaining growth.

The Japanese and Swedish bubbles’ roots of course differed in myriad particulars, and so did the fallout. But the two cases can fairly be compared as enormous speculative bubbles that brought on a systemically threatening crisis. The key difference between the two cases lies in the ways in which the authorities managed the crisis.

The Initial Stage: 1990 to 1994

We can periodize the initial stage of Japan’s crisis management as roughly 1990 to 1994. These four years opened with an initial optimism that the bubble had been successfully lanced, but that hope soon gave way to dismay as the financial authorities realized the asset crash was pushing up a mountain of bad loans. No major financial institutions failed during this period in spite of the sharp declines in real estate and other asset prices and the banks’ heavy exposure to these markets through their loans. The convoy system contained several minor failures, but the lack of systemically threatening bankruptcies did not mean that the banks and other financial institutions were solvent. Instead, fiscal and monetary means were used to cushion and conceal the shock, with help from creative accounting and other administrative evasions.

Among the financial authorities, many understood early on that the sharp decline in asset prices was likely to wreak havoc on the banks’ capital bases. Much of the late 1980s lending was driven by the anticipation of asset price increases rather than reasonable expectations of adequate revenue streams from the investment. The greater the decline in asset prices, the greater the damage to the banks’ balance sheets.

Bill Clinton with Miyazawa Kiichi |

Matters came to a head in the summer of 1992. Stock market values plunged to the YEN 14,000 range, threatening to put financial institutions clearly into the red for the September 30 financial reporting deadline. Given the background of increasing uncertainty and sharply declining asset values, this exposure of the banks as insolvent would almost certainly have led to a very sharp credit crunch. And because Japan had become the world’s biggest banker, the crisis would have had global ramifications. Then-Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi, a former career MOF official, Finance Minister from July 1986 to December 1988, and one of the country’s most astute experts on finance, readily understood that sliding asset values were demolishing the banks’ balance sheets. And he knew that the damage would increase as more borrowers became unable to pay back loans on steadily devaluing assets. He knew this would lead to yet more damage to bank balance sheets, thus restricting the financial system’s capacity and willingness to finance new business, and hence further eroding the economy’s strength. He understood that Japan was confronting a solvency crisis, wherein the longer one waited the greater the cost to fix it. Like the Swedish authorities, Miyazawa determined that the only way to resolve the crisis was to intervene with public funds and relieve the financial sector of its toxic assets. In mid-August, Miyazawa discussed using public funds with BOJ governor Mieno Yasushi, securing the latter’s agreement. While the Nikkei stock exchange continued to dive, Miyazawa prepared to return from his summer retreat in Karuizawa to Tokyo, shut down the exchange and engineer a capital injection (Kume 2001, 110).

Miyazawa was moving towards the Swedish approach of dealing with the solvency crisis in a comprehensive way. As we have seen, this approach entailed organizing a coalition of interests from within and without the financial system, to support the short-term pain of resolving the morass of bad loans. The sum of money was a few tens of trillions of yen, not an inconsiderable amount. But the only alternative was to risk the virtual certainty of much higher costs down the road, through even more devalued assets, squandered fiscal stimulus, lost growth, and other direct and indirect costs (Tahara 2010: 70-73).

But Miyazawa was not the only high-level actor who had been working on a plan. On the evening of August the 17th at his summer retreat, Miyazawa was presented with MOF’s “Urgent Management Plan for Financial Administration.” This program for massively increased forbearance proposed to flood the markets with liquidity, rather than intervene directly in the bad banks. MOF’s plan also included fiscal, monetary and regulatory changes aimed at getting a floor under stock prices and otherwise stabilizing the markets. Among the highlights were administrative guidance that would suppress sell-offs, accounting changes that would allow firms to avoid booking the real value of soured assets, and the use of at least YEN 2.82 trillion in pension, postal and other funds to prop up market prices. Miyazawa does not explain why he assented to the plan even though he regarded it as a “strange document.”

Opposition from the big banks’ doyenne class, especiallythe so-called “Napoleon” Matsuzawa Takuji, head of Fuji Bank and chairman ofKeidanren’s Board of Councilors, wasespecially influential at this critical moment. It apparently was enough to define big business’ stance against capital injections. From Keidanren, the opposition spread, as the talk shifted from fear of a systemic crisis to the prospect that transparency would shift the public spotlight onto pay and perks across a range of sectors. The combined opposition carried the day, bothinside the ruling party as well as in the larger public arena(Kume 2001: 110-113).

The rejection of the comprehensive approach to the solvency crisis then tipped the scales even more to the policy of maintaining the system via forbearance and fiscal and monetary supports. The idea that the public would not accept capital injections became fixed and a self-fulfilling prophecy. Public trust was further alienated by reams of media reports about collusive banks and bureaucrats. There is indeed a rich literature on how Japanese banks were able to exclude loans to subsidiaries from the calculation of their own “bad” loans. The MOF also helped financial institutions hide their bad assets, such as by showing them how to transfer losses from one account to another. The assistance included such collusion as the authorities’ advance warnings of inspections, allowing the banks to move their problem loan files into the basement for the duration. The myriad, ingenious means of concealing the mounting losses belies the tired stereotype of the Japanese as not being innovators (Amyx 2004, Kaneko 2002).

Many observers of this period suggest that the Japanese authorities optedfor this blatant degree of forbearance because they honestly believed the economy would recover in short order. For example, former Assistant Director of the Bank of Japan, Nakaso Hiroshi (2001: 2), observes that the Japanese authorities and financial community were confident prices would return to more sustainable levels and markets would recover on their own. We should probably bear in mind that back in the early 1990s, Japan appeared to have won the ideological competition between its growth model and the Anglo-Saxon alternative. And in addition, there was the plain fact that no Japanese financial institutions had gone bankrupt in the postwar period.The MOF had always managed to coordinate an effective response. In short, the collective cognitive frame was that the institutions of the convoy system had clearly worked well for decades, financing a spectacular postwar recovery, and plenty of actors were confident the momentum would continue in the 1990s.

In retrospect, it seems obvious that the Japanese should have followed Prime Minister Miyazawa’s original proposals to use public money to backstop the shift to a new, rules-based order while recapitalizing the banks and penalizing past excesses. However, as alluded to above, there was opposition to this strategy on several fronts. First, the financial authorities were hoping for a return to growth. And even as the prospect for a quick rebound receded, they resisted going beyond the institutions of the convoy system in seeking to resolve the swelling mountain of bad loans.

It is important to understand that the opposition to Miyazawa’s suggestion drew heavily on concern about adverse public reaction to using taxpayers’ money to recapitalize the banks (Nishimura 1999: 83). Japanese voters were increasingly skeptical of their state and given the paucity of direct social or welfare benefits they received, it was perhaps not surprising that they would be hostile to giving some of the largest financial institutions in the world their tax dollars. Public trust in political institutions and leadership was falling dramatically in this period (Ide and Steinmo 2009) and there was a great deal of publicly unvoiced concern about what serious reform might mean for the clubby sectors of the overall financial system. Exposing and unwinding the rat’s nest of non-performing loans would mean driving a lot of highly leveraged financial, real estate and manufacturing sector firms to the wall. It would also likely mean haircuts, perhaps severe, for shareholders in a swath of sectors. And it would almost certainly lead to vast restructuring of the financial system’s structure of bureaucratic authority and political representation, as it eventually did.

Japan’s convoy system may have had an especially Byzantine set of political-bureaucratic and other vested interests standing in defense of the status quo, but it was hardly sui generis, as recent crises in the US and elsewhere suggest. What appears to have tipped the balance, away from Swedish-style reform, in the Japanese case was MOF’s 1992 liquidity crisis countermeasures. This policy package spiked an outright credit freeze and precipitous plunge in economic growth, a sobering shock that the Swedish authorities faced at the outset of their crisis. The Japanese authorities’ various stratagems managed to delay a credit crunch and clear threat of systemic collapse until 1997.

The Crisis Deepens

The next phase of Japan’s drawn-out crisis began in the mid-1990s and lasted until about 1999, when capital injections truly began. In the mid-1990s, it was becoming clear that the policy of forbearance towards non-performing loans was unsustainable. It was also obvious that the previous years of hoping for a recovery had wasted precious time. Now even big Japanese financial institutions were drifting, in convoy, towards the precipice of default, while the Japanese government was running into the limits of the convoy’s informal resolution mechanisms. In the mid-1990s, the MOF began moving from mere forbearance to unwinding the weakest institutions and encouraging write-offs of non-performing loans. The total unrecoverable losses of financial institutions were estimated in late 1995 as YEN 27 trillion (Cargill, Hutchison, Ito: 1997, 119-120). In July of 1995, the MOF was compelled to put a real deposit guarantee in place to limit the risk of a run on the banks. In June of 1996, it announced that the Deposit Insurance Corporation would protect all deposits (rather than the existing limit of YEN 10 million per person) and other liabilities of banks until March 2001.

The MOF was being forced by circumstance to expand the public sector’s role in insuring deposits and other means to prevent a run on the banks. Yet the lack of public trust continued to hobble progress towards a comprehensive solution. In the summer of 1995, the seven housing loan corporations (Jusen) ran into serious solvency problems. But the issue became a political football, and public resentment strengthened enough for Japanese authorities to refrain from turning to public funds until 1997, when the solvency crisis re-erupted. The bailout of the Nippon Credit Bank in the spring of 1997 triggered an even deeper systemic crisis that autumn. By the time the authorities intervened to protect troubled banks, Sanyo Securities, Hokkaido Takushoku Bank and Yamaichi Securities had already failed. Similarly, the Long Term Credit Bank (LTCB) of Japan failed after attempts to have it merge with Sumitomo Trust Company failed. The LTCB was nationalized by an act of the Diet on October 23, 1998. At YEN 3.2 trillion, it was the largest failure in the Japanese financial system thus far.

Progress had been made: the authorities largely recognized that it was essential to treat the solvency problems in a systematic way rather than seek to resolve them case-by-case. In February of 1998, the “Financial Crisis Management Committee” was put in place to identify banks in need of injections (Takinami 2010). In telling contrast to Sweden, whose Bank Support Authority was set up early with significant powers, Japan’s previous “Financial Crisis Management Committee” (aka the Sasanami Committee) had lacked supervisory powers as well as information about individual banks. The new Committee did have the proper power to do inspections. And as of June 1998, the MOF had lost control over bank regulation and supervision to the Financial Services Agency, a new agency, in cooperation with Deposit Insurance Corporation. The MOF-guided convoy system, with its reliance on informal protection of deposits and case-by-case bailouts organized via MOF and the industry, was no more. There was a formal and comprehensive financial safety net in place. But incredibly, getting this far had taken nearly a decade.11

Even after they had departed from the institutional confines of the convoy system, the authorities continued to hold back from taking fast, large-scale and comprehensive action comparable to Sweden’s. Wishful thinking seemed still to play a role in Japan. The world saw it on display on February 2 of 1999, at an international symposium in Davos, Switzerland. There, MOF Vice Minister Sakakibara Eisuke declared that bank chiefs and the financial authorities were meeting and that the “financial crisis is over or ending. I think it will be over in one or two weeks” (in Sprague, 1999).

Sakakibara’s timing was way off, of course. Years of forbearance, coupled with ultra-low interest rates and the liberal use of public finance, had helped keep the regime in power atop a mountain of toxic debts. But these policies had also sucked much of the life out of the economy as, among other problems, “zombie” firms were coddled rather than new firms created and financed (Nishimura 2011). The 2000s opened with Japan’s financial crisis deepening and its economic challenges worsening. In the early 2000s, there were repeated crises as the markets tested the banking structure and Japan’s weak domestic consumption left it vulnerable to the vicissitudes of global demand. It was not until March of 2005 that writing off bad loans was completed at the major banks. All told, the disposal of non-performing loans (NPLs) was YEN 77 trillion. The total cost of the banking crisis itself has been estimated as YEN 100 trillion in the early 2000s (Hoshi and Kashyap, 2004), but that figure obviously does not include lost opportunities, eroded social capital, and a greatly diminished global role.

Japanese public debt as % of GDP |

In sum, Japanese management of the crisis was virtually the complete opposite of the Swedish success story. Initially, the Japanese authorities opted for a wait-and-see approach and sought to conceal the scope and depth of the financial crisis. It should be evident from the narrative offered here, that the simplest explanation for the policy mistakes made in this period of Japanese history stemmed from the general expectation of quick recovery. Policymakers, the financial community and households proved to be overly optimistic about the country’s economic and financial situation. Committed to the convoy system, Japanese authorities were slow to identify the changing risks in an internationally integrated financial world. They could not, as it were, come together to implement systemic change. Instead, they kept trying to extend the convoy system via one-off interventions. Their interventions were not transparent and did not use uniform and objective criteria as in Sweden. The legal and institutional framework for capital injections and NPL assessments also had to wait until the late 1990s for systemic reform. Virtually all observers of the case find it puzzling that it took eight years for Japan to introduceeffective legal and institutional changes (Katz 2008).

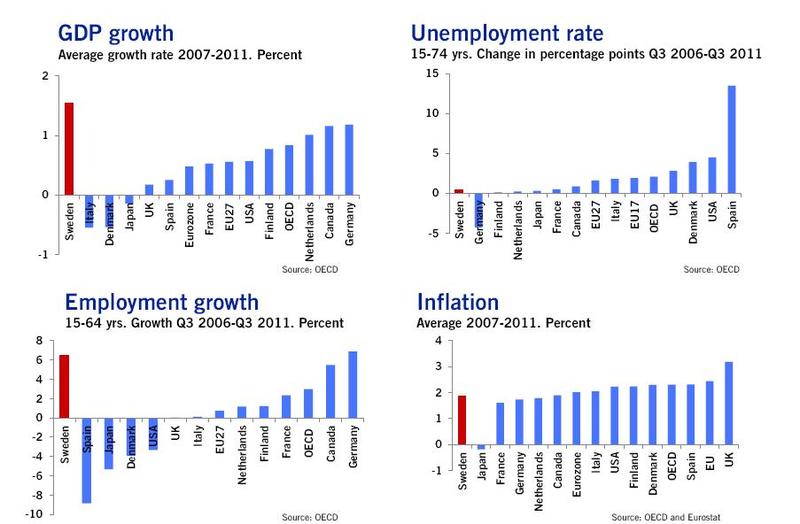

Japanese and Swedish Economic Performance 2006-2011 |

CONCLUSION

It is one thing to look back on a set of policy choices and admire the apparent efficiency and logic of the decisions taken in one case and the inefficiency, if not down right incompetence, of the decisions made in another case. Of course, it is only after the fact that it is possible to truly determine whether good or bad decisions were made. The more challenging question remains: Why were Swedish authorities able to make these apparently good choices? Why, in contrast, were Japan’s choices so sub-optimal.

Our analysis does not permit us to offer a single answer to this question. Instead, we argue that three major factors explain why Swedish and Japanese authorities responded differently to a similar set of problems. First, institutions matter: While at first glance there appeared to be considerable similarities between the Swedish and the Japanese models of decision making in that both had developed cooperative relationships between regulators and the regulated and both had been supported by a single-party dominated political regime for several decades (Pempel, 1990), our analysis reveals significant differences in how these institutions actually functioned. Most importantly differences in the relationship between the government, bureaucracy and political interests that are not already inside the governing coalition explains the degree of transparency in crisis management in the two cases. The Swedish model of social corporatism led the government to manage the crisis in a transparent way, which in turn encouraged it to focus attention on protecting the interests of the broader public. From the very beginning, the government brought opposition political leaders into the center of the decision-making system, disclosed information about the scope of the problem, and jointly explained to the public the reasoning behind their decisions – including why they bailed out some financial institutions while letting others go bankrupt. The contrast to the Japanese case could scarcely be more stark. In Japan, the government and the bureaucrats concealed the scope of the crisis from both the public and the opposition political parties, and instead focused on protecting the interests of Japanese financial institutions. They trusted the capacity of their convoy system to solve the problems, and distrusted parties and interests who were not already insiders. Consequently they acted in a non-transparent way by encouraging and supporting their major financial institutions to bail out the smaller ones with mergers and acquisitions. This strategy appeared to save the day – until the major financial institutions started to go bankrupt.

Our analysis shows that perceptions or cognitive framing of elites played an equally important role in the management of crises in Sweden and Japan. Most of the Japanese elite did not perceive the severity of the crisis and expected a quick market-driven recovery. This was largely due to the success of the Japanese economy in the post-war era, including its ability to overcome a range of crises such as the oil crisis of the early 1980s. Not only had no financial institution ever gone bankrupt in post-war Japan, but more importantly, the Japanese convoy system was widely credited with being the cornerstone of Japan’s impressive post-war economic development. Their economy had proven resilient against the oil shocks in the 1970s and there was a growing consensus that Japan offered a new political economy model. In contrast to their Japanese counterparts, Swedish elites were critical of their political economy model since the early 1980s having suffered consecutive devaluations, problems in industrial relations, and a decade of comparatively low growth. With that in mind, Swedes were quick to respond to the crisis and take the necessary measures to prevent the adverse effects. We do not suggest that these perceptions or cognitive frames were accurate. Instead, we believe that to understand why elites in these two countries acted as they did it is not enough to simply focus on the structural or institutional variations and show how they provided different incentives to policy makers. Clearly, as we have shown, institutions and incentives matter. But to understand real choices by real people one needs to bring in the different cognitive models they bring with them when facing choice situations.

|

Finally, not only did elite perceptions shape the outcomes, but public opinion also limited the options available to authorities. In particular, policy makers in Sweden and Japan did not have the same liberty in using public money to inject capital into the financial system when they were confronted with insolvency and illiquidity problems. The key explanatory factor was public trust towards political institutions and specifically public opinion concerning the use of public money. The structure of the Japanese welfare state and political institutions encouraged the use of public funds to placate specific interests in a collusive way. Such a set up leads Japanese people to strongly oppose the use of money even in cases such as financial crises. In contrast, the Swedish welfare state and political institutions with their universal character and equitable distribution managed to create a broad support base and trust towards public spending. In this respect, the Swedish authorities had a wider opportunity space compared to their Japanese counterparts.

Having discussed these three features of crisis management and three explanatory factors, we also point out that some evidence suggests that multiple streams came together in different ways (Kingdon, 2004). In other words, we do not provide a simplistic account with three dependent and independent variables. Instead, the existence of three features of crisis management and three explanatory factors can interact in a particular way. The case of Japanese Prime Minister Miyazawa is a case in point. One of the few Japanese authorities who recognized the full extent of the severity of the problem at the beginning of the crisis, he was moving towards a comprehensive approach to address it. However, his ideas were crushed by a coalition of bureaucrats and big banks who opposed capital injections and otherwise handling the crisis in a transparent way. This view was reinforced by the idea that the public would not accept major capital infusions, and that it would be politically less risky to handle the situation in a non-transparent way with minor monetary and fiscal support. Furthermore, most of the elite sincerely believed in the quick recovery of the Japanese economy, and Miyazawa could not convince his colleagues that they confronted a serious solvency problem. In other words, the three explanations previously discussed as separate factors interacted in a particular way – even in this specific case.

So What?

At the end of the first decade of the 21st century the entire world faced yet another financial crisis similar to Swedish and Japanese crises discussed in this paper: Deregulation of financial markets led to changes in the behavior of formerly conservative financial institutions, resulting in an asset price boom, and eventually a collapse of housing and stock markets. In the most recent case it was America in 1908, the world’s largest economy, leading the wave; consequently the effects were far more significant throughout the world economy. Reinhart and Rogoff appear correct in arguing that there are common sources for such crises, but we have seen that governments respond differently and with varying implications for the financial and economic health of the countries affected. In this context it is worth inquiring how both Sweden and Japan have been affected by and responded to the financial collapse of 2008.