After a short introduction contextualizing revisionist history in Japan and controversies over the representation of imperial and wartime violence in Japanese textbooks, this piece presents translations of a wide variety of student writing projects and classroom resources from progressive educators. Focusing exclusively on textbooks results in a limited view of what actually goes on in Japanese classrooms. This collection highlights some of the ways that critical educators have resisted revisionism and brought vivid discussion of controversial issues to the classroom.

Introduction

The economic setbacks suffered by Japan in the early 1990s brought with them a sense of social malaise that has lingered to the present. In recent years, only a small minority of Japanese believe that their country is on the right track and while “Abenomics” has public confidence on a slight upswing, it is far too early to tell if this will hold.1 A variety of reasons for this malaise are offered – ineffectual government, debt and fears about pensions and healthcare, a revolving door at the Prime Minister’s Office, “out-of-control” bureaucracy, the rise of China and China-Japan clashes, are a few of the most common. The far right, however, has pinpointed a different problem – an education system they deem “masochistic”.

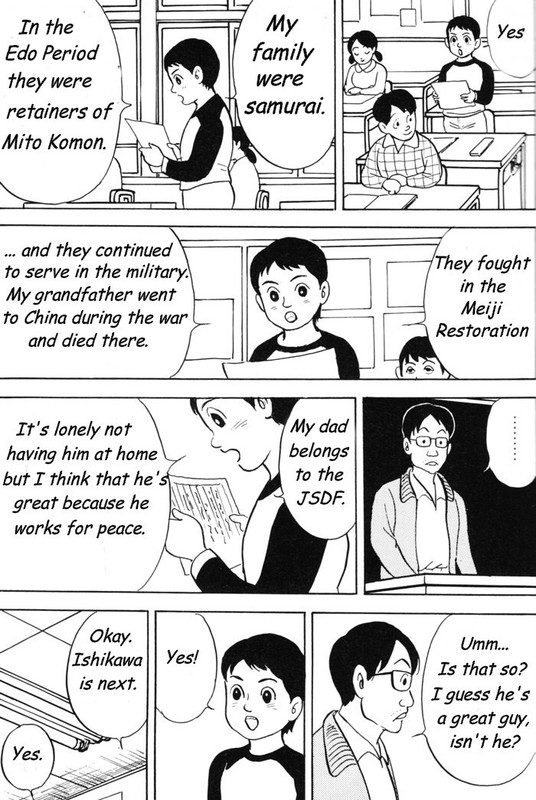

In the 2007 book Nihonjin no Hinkaku (The Dignity of the Japanese), Watanabe Shoichi, one of Japan’s most prolific neo-nationalists and a close advisor to Abe’s Minister of State for Regulatory Reform, Inada Tomomi, sums up rightist fears of what education is doing to Japan’s youth, “Just how are these children who have been told over and over again that “Japan is no good, Japan is no good” going to turn out? There is simply no way that children who are taught things like “Your fathers were aggressors, your grandfathers were aggressors, they committed massacres” can live with their heads held high…. It is because of things like this that Japanese have lost their identity and their pride. When human beings lose their pride, they lose with it the ability to accomplish anything. They lose their energy and they lose their morals. When it gets to this state, society has nowhere to go but down.”2

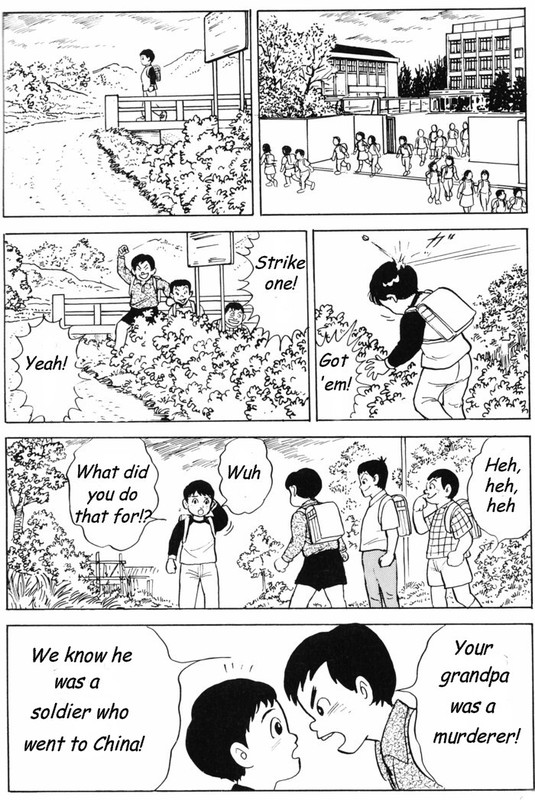

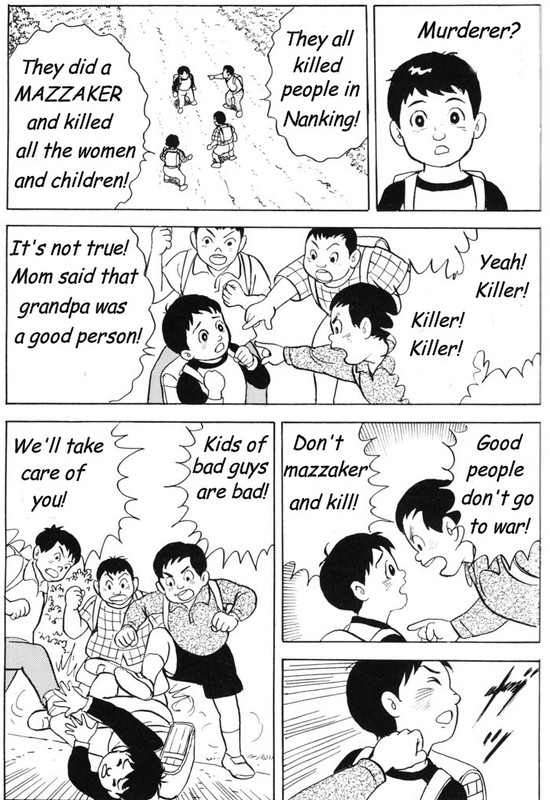

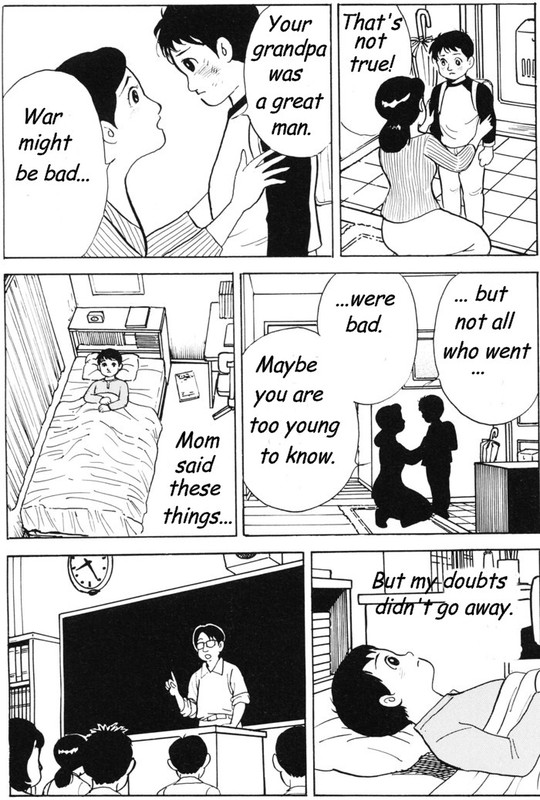

Watanabe’s attempt to connect social ills with education about the past is entirely abstract, but Manga Nihon no Mondai (Manga – Japan’s Problems), one of a number of titles that attempted to cash in on the success of rightwing manga by Kobayashi Yoshinori and Yamano Sharin only to fail and disappear quickly from store shelves, provides valuable insight into how some rightwingers envision critical history education warping young minds, [Manga images should be read in Japanese manner from RIGHT to LEFT.]3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Critical history leading to schoolyard bullying? It is simply unbelievable that the behavior depicted in this manga is widespread. On the other hand, we know of numerous examples of the bullying, harassment and violent tactics of adult rightists. One incident, recorded and put on the web in 2009 as an example of “defending Japanese sovereignty”, took place at a schoolyard where extremist thugs threatened and berated pupils at a North Korean affiliated school in Kyoto (video right).4

This manga is not part of a critical or reflective dialogue, but rather a form of fantasizing the collapse of Japanese pride. While many Japanese educators and scholars lament the apathy of young Japanese toward the country’s war legacy, the right chooses to imagine “masochistic” knowledge of the past as a pervasive, creeping pollution of young minds.5 This idea seems impossible to square with quantitative measures of popular attitudes. A December 2008 internet poll of 1030 men and women over age 20 revealed that 86% were “happy to have been born in Japan”.6 Only in the rightwing imagination, it seems, are Japanese robbed of positive feelings about their country through history education.

It has been pointed out in a variety of contexts that Japanese rightists and many mainstream conservatives see education as a potential means of supporting policy goals such as constitutional revision and either increased overseas military participation alongside the US or a break from the Japanese-American alliance that would pave the way for the country to go its own way militarily.7 These options have limited public support as a solid majority of Japanese favor the status quo and place military issues far down on lists of policy priorities with recent public opinion polls showing that pensions, healthcare, employment, and responses to the recent economic downturn dominate voter attention.8 A variety of visions of Japan’s future deserve public discussion, but rightwing pundits and ideologues have frequently supported their positions with fantasies that make reasoned debate impossible. For example, Sugiyama Katsumi in the 2000 tract Gunji Teikoku Chugoku no Saishu Mokuteki (The Final Goal of the Chinese Military Empire) supported calls for more nationalist education and robust armament with the following historical vision:

I think that it is likely that no matter where you look, among the 7000 ethnicities on this earth and from the dawn of recorded history, there is none that has built a unique civilization based in peace, that has had so little connection to cruelty, as have the Japanese.9

There is certainly no reason to argue that Japanese have been uniquely cruel or that there is some essential taint in Japanese culture. But the viciousness with which some ultra-rightists have attacked critical, reflective history is deeply linked with this type of neo-nationalist mythology.

This ultranationalist view of Japan’s past, while not without its supporters, is far from dominant among the “silent majority”. A 2007 poll carried out by the Asahi Shimbun revealed that nearly 90% of Japanese believe that continued hansei (apology and reflection) concerning the nation’s wars and imperialism is necessary.10 Only 2% supported the denialist position that it is absolutely unnecessary. This is entirely coherent with the view that national pride can and should be expressed in myriad ways. This mainstream sense of contrition has influenced public culture and debates. Especially notable is the fact that only 0.4% of Japanese middle schools were exposed to the Atarashii Rekishi Kyokasho (New History Textbook) that caused such furor in East Asia when approved by government monitors in 2005.

Conservatives have attempted to spin resistance to neo-nationalist directions in education as some sort of insidious conspiracy on the left. Current rightist Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, in a 2004 interview about the failure of the earlier 2000 version of the New History Textbook opined:

… there was serious pressure put on the people in charge of selecting which book [to use]. There were threats made against committee members. One such member, a Shinto priest, got a phone call to his house saying, “There’s an old grandma living in your house, right? Stairs are very dangerous so I hope that you are taking care.” This is basically an example of him getting a threat making him think that they’ll push the old lady down the stairs of the shrine…. Lately, whenever something like this happens there are certain newspapers that will instantly start in on “human rights violations” and “contemptible behavior”, but I wonder why they were silent this time?11

Here, what was overwhelmingly a genuine outcry by concerned progressives is described in terms that would be better applied to the far right, whose record of threats and violence is well documented.

Abe’s comments illustrate just how contentious Japanese history education has become. In early 2009, the third edition of the New History Textbook was approved as one of a number of options for use in middle schools. It was more successful than its predecessors as it was selected by a city panel for use by over 10,000 students in Yokohama.12 In addition, mainstream textbook publishers have dropped references to the “Comfort Women”, common in 1990s texts, partly to avoid rightwing protests and criticism. While there is a legitimate debate about whether or not to teach about sexual violence to students who are 12 or 13 years old, at present, no officially approved middle school texts include the history of the “Comfort Women”. By introducing revisionism and rightist historical visions into textbook discussions, the New History Textbook authors have had an impact greater than their book’s meager acceptance rate would suggest. There is, however, evidence of some compromise by the right as well. The goal of the New History Textbook is to present a nationalist narrative of the past. The latest version of the book, however, is vastly different than the often vicious denialist polemics produced by ultranationalist pundits.

From the beginning, the 2009 book plays up an ethnocentric form of nationalism, telling children, “The history that you will learn from now is the history of Japan… this is the history of ancestors who are connected to you by blood.”13 It makes no secret of framing Japanese history as a positive tale, “…this is also a history of tension and friction with various foreign countries. However, today’s Japan which is prosperous and the safest country in the world was built atop the unwavering efforts of our ancestors.”14 Room should be made for positives, but the tone here seems overblown.

The actual historical narrative of the book has ups and downs. A great deal of the telling of modern history is oriented with current territorial disputes in mind. For example, there is nearly a full page of text on the “Northern Territories” in the 19th century. The history is told so as to foreshadow Japan’s current conflict with Russia over the contested islands.15 The book is also peppered with the heroic. After details of the battleship Yamato‘s vital statistics and the power of its guns, the authors lament that, in a war that Japan was gradually losing, Yamato never had a chance to demonstrate its power in combat.16 The book dramatizes the Yamato‘s hopeless suicide mission as a heroic last stand and revels in tech-fetishism typical of “military fan” pop culture products.

Some of the most striking characteristics of the 2009 edition, however, are its concessions. For example, efforts have been made to make the current edition more coherent with international understandings of Japan’s colonial rule of Korea. The private writings of revisionists characteristically depict Japanese colonial rule as a combination of self-defense against a brutal, imperialist “West” and a selfless attempt to rescue backward neighbors from Western colonial predators. In the textbook version, however, critical concessions, perhaps at the behest of government textbook screeners, are to be seen throughout the narrative:

In 1910, Japan, with military power in the background, suppressed dissent in Korea and went through with amalgamation. In Korea, there was fierce resistance to the loss of ethnic self-determination, and a deeply-rooted movement to restore independence continued from that time. After the annexation, the colonial government in Korea, as one part of its colonial policy, built roads, irrigation networks, fostered development, and also began a land survey. However, through this modernization program, more than a few farmers were driven from the land that they had been cultivating up to that time and various policies of homogenization which ignored Korean cultural traditions were pushed forward, further strengthening the negative feelings of the Korean people toward Japan.17

This is a considerable compromise when compared with the mandate expressed by leaders of the new history textbook movement in the 1990s, which stressed a uniformly positive vision of Japanese empire. If anything, it bears a similarity to the August 10, 2010 apology offered by Prime Minister Kan Naoto to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the annexation of Korea.18

One of the most frequent rhetorical abuses perpetrated by Japanese revisionists involves presenting the views of past elites as fact. In the New History Textbook, the idea that Korea was a “lifeline” necessary to protect Japan is clearly presented as subjective opinion, “After the Russo-Japanese War, Japan thought that it was necessary to amalgamate with Korea in order to protect the country and interests in Manchuria and went through with it with military power in the background. There was resistance within Korea to this loss of ethnic self-determination.”19 Here “Japan” thinks and acts like a sort of anthropomorphized character, but at least the decisions of this character are not uniformly put forward as objective good.

In the end, however, the book remains riddled with problems. The Nanking Massacre is limited to a footnote description.20 It is presented more as a continuing controversy than a contextualized example of wartime violence, that is, the reader never learns significant details about what happened at Nanking, the wartime Chinese capital, only that there were deaths and that the number is disputed. On the whole, Japanese war crimes are not ignored; they are instead bound in by a careful relativism and presented at a level of generalization that obscures the extent of the atrocities inflicted against civilians:

In the two World Wars, the [rules of war] were broken many times. In actual fact, there was no country that did not commit acts of murder and brutality against unarmed people. During the war, in areas under attack, the Japanese army also committed acts of murder and brutality against enemy soldiers who had become prisoners and unarmed civilians, leaving great devastation behind them.21

This is followed, however, by a description of the crimes of Nazism and Stalinism, described in greater detail than Japan’s own.

From the perspective of more complete, honest narratives of Japanese history, other textbook options available to Japanese schools convey a much better sense of the historical record than the New History Textbook. Teikoku Shoin’s Chugakusei no Rekishi (History for Middle Schoolers), for example, makes a number of choices that differ in essentials from the New History Textbook historical view. Rather than playing up the Japanese request for a racial equality clause during the Versailles Treaty negotiations, for example, the book details Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence, Chinese protests against Japan’s imperialistic “21 Demands”, and the March First Movement of 1919 in Korea, with references to the violent oppression and acts of torture used to put it down.22 The three images on this page are a relief depiction of Yu Gwan-sun, a Korean student who was arrested in 1919? for her role as a leader in the movement against Japanese colonialism and died in prison, a painting of a march by Chinese students protesting Japanese violation of Chinese sovereignty in 1932, and a photograph of Gandhi at his spinning wheel. While similar images are also present in the New History Textbook, other available books have a more consistent focus on the abuses and violence against noncombatants that were a part of Japan’s imperial wars.

2011 texts were released with considerably less international controversy than their predecessors. A split in the revisionist textbook movement has left the new Tsukurukai book with only a miniscule 0.05% market share while the other nationalist alternative from Ikuhosha, not substantially different from older revisionist texts, is set to see use at over 400 schools, a 3.7% acceptance rate which bespeaks intensifying neo-nationalist activism at the local level.23 It can also be argued, however, that the Ikuhosha book found marginally more success by shedding the controversial Tsukurukai brand, despite no significant content difference.

On the whole, none of the Japanese middle school textbooks short change modern history. The period between Perry’s arrival in 1853 and the present makes up approximately 40% of the various texts. However, the nature of the textbook genre assures that descriptions of critical issues such as colonialism and war, including hot button, issues such as the Nanking massacre and the comfort women are necessarily brief if they are mentioned at all. Among recent books, the New History Textbook stands out as most problematic, yet all the choices seem inadequate for shaping a nuanced historical understanding. The textbook is a constricting medium. Just what can be expected of an illustration-rich tome of a bit over 200 pages that chronicles all of Japanese history from earliest times to the present? So limited is the discussion of any historical event or topic that it is difficult to imagine that the strategic omission of the word “aggression” in a heading on Japan’s modern history in the New History Textbook or the use of a more or less clear verb when referring to the Nanking massacre will play that great a role in shaping the historical understandings and identities of students. It is nevertheless significant that whereas the New History Textbook description of the Nanking Massacre acknowledges that “there were many dead and wounded among the Chinese civilians and soldiers,”24 Chugakusei no Rekishi establishes agency far more clearly, recording, “The Japanese army… killed many Chinese people including women and children.”25 Do these gaps in representation, however, make a great difference in the classroom? In the end, all choices seem doomed to disappoint. Detail, from prehistory to the present, is sacrificed for brevity. While more should certainly be demanded of the New History Textbook and other books, the key to nuanced reflection on the past, it seems, is to go beyond textbooks altogether. Textbooks are still an effective measure of the political will to look honestly at the past and in this area, the Japanese government has sparked far more controversy than conciliation.26 For shaping the historical understandings of students, however, only so much can be expected of these books.

From the time of the American occupation, Japanese progressives have developed supplemental “educational materials” called kyozai to go beyond the limits of textbook-based learning as well as separate study guides for students. Progressive kyozai were first developed in large numbers from the 1950s to challenge the silences on wartime aggression and atrocities that permeated state rhetoric and shaped early postwar textbook accounts. Since the 1990s, despite some narrative holes and overall brevity, textbooks have been far more honest about Japan’s war record. It is now not so much counterpoints that are needed as effective complements. To meet this need, progressives have produced teaching supplements on numerous themes. The quotation in the title of this essay, “Why on earth is something as important as this not in the textbooks?”, is from a transcript of a high school classroom discussion of Comfort Women presented in a progressive educational supplement. Kyozai give us access to a side of Japanese education that seldom enters into textbook-centric debates.

Kyozai are also important as the ultra-right, with its one-track focus on a “New History Textbook”, has for the most part ignored other options.27 Major Japanese bookstores and public and school libraries have a range of progressive kyozai, but the right, focusing on their textbook crusade, have not produced any of note. The dominant figures in the movement to establish a more nationalist focus in education favor a rigid pedagogy which helps to explain the overwhelming focus on a “new” textbook vision. Nishio Kanji, one of the movement’s most important early leaders, for example, believes, “It is because [students] are forced that education has meaning… education is something that should be pushed on young people even if they don’t want it. School work is training, and that has to be forced.”28 In this view, Japanese young people are considered to be empty receptacles, effectively something to be shaped and molded to meet the demands of the state.

Many kyozai are rooted in a very different philosophy of education. Yamada Akira, a leading educator, has written in detail about the problems surrounding the contemporary history classroom. He posits that one of the major difficulties facing history teachers today is that neither the students nor the teachers themselves have a foundation in experience from which to imagine warfare.29 Yamada rejects what he calls “rote-learning-ism”, stressing that simply memorizing terms like “Nanking Massacre” is meaningless without giving students a chance to express empathy, engage in critical inquiry, debate, and the exploration of sources and sites to fill the gap left by the lack of personal war experience of students and their families. For Yamada, “one of the most important things for history education is inspiring [in students] a genuine feeling that history is the lived experience of actual human beings.”30 Personal stories and understandings – either those of the students or, in the case of education about war, of the perpetrators and victims on all sides of Japan’s 20th century conflicts – are something that the New History Textbook discourages with its dramatic national narrative but are an important part of many kyozai. Yamada also emphasizes place – the importance of local histories and experiences as a way of challenging narratives that are so sweeping that the lives of people are rendered insignificant – another dimension of historical understanding that kyozai cover well.

Below are translations of selected kyozai, including translations of sakubun (student essays) spanning the postwar period. These sakubun have in turn been compiled for classroom use as examples or reading assignments for students. They reveal a different side of Japanese education than that which is usually considered by scholarly literature and critical reportage that have too often focused exclusively on textbooks. Textbooks do, of course, play an important role in shaping history education and public discourse, but by no means do they determine all educational outcomes in Japan or elsewhere.

Kyozai and sakubun raise important questions. From what age are children mature enough for discussion of issues such as war responsibility and war crimes? What is the right balance between stories of the wartime suffering of Japanese and stories of the suffering inflicted by Japanese on others? Should the central purpose of “peace education” be furthering national projects of reconciliation, empathy with the points of view of others, or the inculcation of an anti-war ethos? How difficult is it to achieve all of these aims together? How should the postwar Japanese Self Defense Forces be introduced in classrooms? On these and other issues of pedagogical importance, the sources below raise as many questions as answers. They are indicative, however, of a level of engagement with the past in Japanese education beyond the level of textbooks and offer a glimpse into the diversity of personal, local, national, and international stories and images that some Japanese educators have used to attempt to come to terms with the past. These kyozai constitute the Japanese progressive response to a question posed by Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob in the influential Telling the Truth About History: “… which human needs should history serve, the yearning for a self-affirming past, even if distortive, or the liberation, however, painful, that comes from grappling with a more complex, accurate account?”31

Sakubun

The student essays and poems translated below are from the collection Doshite Senso suru no (Why Make War?) compiled by the Nihon Sakubun no Kai (Japanese Student Essay Society), a group formed in 1950 to promote essay writing. It was released by progressive publisher Otsuki Shoten to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of Japan’s wars in 1995. It contains a wide variety of accounts – from early postwar essays in which students attempt to come to terms with their own war experiences to later re-tellings of stories heard from parents and grandparents. The work is part of a series widely available at school and public libraries. In contrast to the spare and often didactic accounts of the textbooks, these texts, they offer teachers and students moving accounts of war and model essays at all grade levels to inspire reflection and writing.

My Sister who Vanished

Tsujii Akemi, Middle School Year 3

Yamaguchi

1952

It’s a horrifying memory.

12:01, August 14, 1945.

American bombers attacked in full strength and turned the area in front of Iwakuni Station to ruins in an instant.

At the time, I was in Grade One. Father was in the army and went away, my mother, sister, brother, who was only three, and I, were left behind. We were living near Iwakuni Station and when I think of it now, it was such a horrific thing.

I remember my cute little sister. My sister who had little dimples when she laughed.

I hid in the bathroom when it happened. Mother dashed in, carrying my brother on her back. Without thinking, I screamed ‘Mommy!’ Without saying a word, my mother grabbed my hand and we jumped into the ditch behind the house. The ditch had a concrete lining. Mother was calling “Yoko, Yoko”. Shouting desperately for my sister. I realized that Yoko wasn’t there, but I started to feel faint.

I wonder how much time passed? It was probably only a very short time. I realized that it was getting brighter. My mother, my brother, and I, all three of us were safe. Our house, however, had vanished and not a shadow or shape was left… The three of us, covered with mud, started to cry. Blood flowed from my brother’s head as he wailed. My mother cut her hand on the concrete and blood poured out. Only I was unhurt.

The three of us prayed together that Yoko was alright…. My mother kept calling her name. I can still see the way that my mother’s face looked at that time, I can still hear her voice. I can’t forget. That horrible thing one day before the war ended.32

In front of City Hall a nurse tended my brother’s injury and he cried himself to sleep. My mother left my brother and me in the evacuation area and went to look for my sister…

However, no matter where she searched, there was no sign of her. We lost our house and lost our possessions but that was fine, it was our most precious thing, my sister who had vanished. I called out to my father across the sea.

Five days passed and Grandpa came from Kobe. Our possessions had all been blasted into the earth and not a thing could be saved.

Two days later we found Yoko’s body in a nearby field. When my mother and I saw my sister, we cried and cried and cried. Grandfather and grandmother from Kobe cremated my sister’s body where it lay.

A horrifying memory, a painful memory. It has been seven years since then and we are trying to build a new, peaceful Japan. Father returned home safely and now we’re living happily as though it never happened. Now I have another sister, Ritsuko, who is like Yoko, my brother my sister and I are all well, and my brother and I go happily to school each day. But every year, on August 14, we say prayers for Yoko. My sister who vanished.

Standing Above the Bones

Ishihara Kana, Primary School Year 4

Hiroshima

1997

It is beautiful there now

But I went to see the other city sleeping beneath the Peace Park

The one left in ruins by the atomic bomb

If you dig at the Peace Park, Mr. Nishida said

You will find people’s bones

Right now, I wonder if I am standing above the bones

When I think about it, I feel frightened

Inside, the names of the dead are all there in a row

If my Grandfather and Grandmother had died in the bombing

Their names would be there too

When I think about it, I feel sadness

In the atomic bombing

Babies

Grandmothers

Mothers

Grandfathers

Many innocent people were killed

I hate atomic bombs

They bring suffering

Terrible

No more atomic bombs

My Grandpa who Went to War

Higuchi Takenobu, Primary School Year 6

Nagano

1987

Grandpa

His eyes filled with tears

He grasps a tissue

A middle aged man is

Saying something on TV

Crying

A program on the Chugoku zanryu koji (war orphans left in China)

Grandpa

Part of a heavy machinegun unit

Went to attack China

Fighting the ‘enemy’

He trampled fields

Burned houses, villages

He killed people

Sometimes he was surrounded

He says

With sweat running down his forehead

Sometimes he calls me

Shows me photographs from wartime

“I went there”

“This was our commander’

He says with pride

On Grandpa’s face

A smile

The same Grandpa

That sheds tears watching TV

And says ‘war is wrong’

When I hear his war stories

It sounds as though there were good things too

I just can’t understand this feeling

Because war is absolutely wrong

Manchuria Unit 731

Nakano Yusuke, Primary School Year 4

Tokyo

1986

I read the book called “Manchuria Unit 731”. This book is divided into four major parts called “Manchuria Unit 731”, “Air Raids”, “War is Wrong”, and “Children and War”. Among them, it was the Unit 731 chapter that made me feel most strongly that we must never start another war, and I am writing my reflections on it. The Manchuria Unit 731 was based in northeast China and used Russian, Chinese, and Korean people for poison gas experiments, infecting them with germs in order to observe the results.

The people in that unit called the people that they were using in their experiments maruta (logs). I thought, “Why are they calling people who are human beings just like them ‘logs’?” This helped me to understand just how Japanese at that time looked down on Chinese and Korean people. Even though 40 years have passed since the end of the war, I think that Chinese people are still probably really angry. If there are people who think that they aren’t angry any more, please imagine this – if lots of strange people barge into your house and do whatever they want, anyone would feel angry, right? … At times like this, I remember my mother’s saying, “People who do bad things soon forget but people who have bad things done to them never can.”

…

The worst thing was the vivisections. They just took things out until they died. They preserved people’s heads as specimens. There were lots of stories like that. When I read about this, I became very sad. It was just too cruel. Important people wanted to see which of their men were better at cutting down people and just made them cut down the Chinese people who were there. If their heads were not still attached by a piece of flesh, it was no good. They said things like that and cut down Chinese people themselves. They were laughing when they did it. We would feel sorry for the victims and couldn’t possibly cut them down. I showed my mother this part of the book and she said, “War tarnishes people’s hearts and souls”. I said, “Yes, yes that’s right.” It’s because the important people at that time didn’t feel sorry for the victims, didn’t feel that they were of any use, that they were able to cut them down. I thought, “Why wasn’t there anyone who opposed them? Why didn’t they realize that what they were doing was wrong? Important people are scary. But, if the people below them band together, they can put a stop to things.”

…

But it was for the Emperor. It was for Asia. It was a just war. They believed things like that. This was written down in the book and I couldn’t help but think, if you believe that you have justice on your side there is no stopping things.

…

There is more. Pest and flea bombs. They put many of the people that they called “logs” into small rooms, threw in pest and flea bombs, and exploded them. The fleas inside would come out and bite the people. After 30 minutes, they would let the people out and observe the onset of infection. When I think of the people who were murdered in this way, I can’t help but think that it was really great that Japan lost the war. The reason why is that I think that if Japan had won, it would have gotten even more arrogant and done more and more horrible things.

The Black Killing Machine – B-52

Yamakawa Kiko, Middle School Year 1

Okinawa

1968

On December 19, at 4:15 in the morning, my house suddenly began to shake and I woke up. At first, I thought that it as an earthquake, but then I heard an explosion and I thought that war had come. When I got out of bed, mom and dad were already preparing to leave. When mom opened the door and looked outside, the sky was as bright as noon, and I saw a pillar of fire burning in the sky to the east. The explosions didn’t stop. Shaking … I stuffed books and clothes into my bag. The explosions faded into small bangs.

My father and brother went outside to see what happened. My mother and I were left behind and couldn’t relax. I thought, “Is this war? Such a terrible thing.” Where will my family go? My mother packed a bag with dried bonito fish.

What would we do if an armory exploded? What would we do? Ah, I can’t stand it any more. Feeling like this every day, having to live like this, I felt so uneasy. That’s when father and brother came back to us.

“Americans and Okinawans are all running to the north or south.”

Father dialed the police. “Where should we evacuate to?” They replied, “We don’t know. We’re in trouble too.”

The explosions began to stop. Dad went up on the roof to see.

As long as there are bases on Okinawa, there is no guarantee that an accident like this won’t happen again. I want to live in a place with no bases, a quiet place, as soon as I can.

I can’t take it any more. I just want to live in a place with no explosions, a safe place, a peaceful place.

I don’t want to be anyone’s sacrifice. Why do we and the people of Kadena have to hear explosions? I don’t want to hear them for anyone else’s sake. I don’t want to suffer for anyone else’s sake.

The Willow Tree of Willow Town

Tsushima Mariko, Primary School Year 4

Morioka

1972

My house is right next door to Yanagi-machi (Willow Town) where there is a willow tree. That tree was planted by Korean people to celebrate going home.

When the country Japan made the country Korea part of its land, the Korean children, even though they were in Korea, were still forced to learn Japanese history and Japanese language.

Korean people saw posters in their town and came to Japan to work on roads. But when they came, they had to work in a coal mine. When the Korean people tried to protest, the Japanese manager came over with a wooden rod and beat the Korean people. I think that the Japanese side was bad for telling lies. They told lies and made them do the worst work so I don’t think that they had any right to beat them.

The house where the Korean people lived was only one room about 10 tatami mats in size, but there were about 30 people living there. I don’t think that there was any way that they could have stretched out their arms and legs when they were sleeping. Their futons were senbei futons and even on holidays they couldn’t go outside.33 If one of them got hurt and the others gathered around, they would be called lazy and the injured one would be beaten with a wooden rod. They say that some of them were beaten to death. If it was a Japanese person, they wouldn’t do anything like that, they would bring them right to the hospital. They treated Japanese people so differently compared to Korean people. I don’t think that there should be any difference between human beings.

Around the time that the war ended … the Korean people begged to be allowed to live like human beings but all they got was a bit more food. Around the time the war ended they were made to work many times harder than before.

When those people were finally able to go home, they planted the town’s willow tree to mark the occasion. I think that they planted it asking us to never do something like that again and to treat the people left behind with kindness.

I felt that there was no way that Japanese people could do horrible things like that, but now I think that Japanese people have a cruel part too.

We who don’t know War

Yamazaki Hiromi, Primary School Year 6

Niigata

1971

We children were born knowing nothing of war.

Before, there was a hit song called “The Children Who Don’t Know War”. I wonder what they were thinking when they wrote that song. I wonder if they thought deeply about war and wrote that song. Adults say things like, “Kids today don’t know nothing about war, they just do whatever they want and don’t feel any responsibility.” They don’t think that we’re very reliable.

…

I finished studying from the Meiji Period to the Showa Period in Social Studies class. What interested me most about that class was the political situation in Japan in the Meiji period, especially how ordinary people thought about politics.

Exactly why did the people dominating politics during the Meiji Period decide to make war? As I began to pay more attention to Social Studies, I started to become more interested in the way Japan went from starting one war after another.

Here, I will write what I learned in order.

From the beginning of the Meiji Period, the farmers who were made fools of during the Edo Period found happiness under the new ‘Equality of the Four Classes’ law. I learned, however, that the farmers didn’t have any say in politics.

When I look at the timeline in our Social Studies book, in 1894 there was internal strife in Korea, and both Japan and China tried to improve the political situation in Korea but they couldn’t agree and the Sino-Japanese War happened.

Because they couldn’t agree, war happened. Just because of that? If they can’t agree right away, they should talk until the two opinions come together. It is just crazy to start a war right away. Just because their opinions didn’t meet many tens of thousands or millions of innocent people were sacrificed…. Just what were the politicians on both sides thinking? When I investigated just what kinds of attitudes led to the beginning of the war, I found out that it wasn’t a war that considered the opinions of the majority of the people. Also, fighting in unrelated Korea, the poor Korean people…. My teacher said that wars break out because of the advantages and disadvantages in political relationships between countries. But just who was it that profited from that war?

The farmers who suffered didn’t benefit from the “Equality of the Four Classes” after all, didn’t they just end up suffering when the young people were grabbed and sent off to the battlefield?

…

I came to understand that horror after studying the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, Manchuria, and World War II. I want everybody to know about that horror.

In war, even if they win and the country gains, the ordinary people get nothing… From my teacher, I was shocked to hear about how dirty Japan’s way of waging war was… During the war with China, innocent Chinese people and even children were victimized. What was that? I thought that maybe it was just a little injury. I thought, “They couldn’t possibly have killed women and children!” But I was wrong and it looks like still more terrible things happened.

According to the Asahi Shimbun that my teacher read for us, the first way of killing, I don’t think that I can even explain it, was to tie their hands and legs to a post and to pour sulfuric acid on their face from above… With that way of killing, Japanese just treated them like toys. Isn’t that just too cruel? If Japanese soldiers just did things like that without feeling anything, they weren’t human beings at all, they were demons.34

My teacher read us another article. “In the war with China, when fighting ended, Japanese soldiers would go around killing the Chinese who were hiding. Chugoku no Tabi running in the Asahi Shimbun really serves well for Social Studies.”35

…

The more you study, the more you come to understand that war is a horrible thing. I feel embarrassed that I thought that war is cool. I think that we should treasure the spirit of defending peace in the Japanese constitution. I understand now that not knowing anything about war was a bad thing.

Kyozai and Study Guides

Gakushu Zukan Nihon no Rekishi

A typical illustration – draftees given a sendoff before heading for the front – fromGakushu Zukan Nihon no Rekishi |

In 1995, Kodansha, Japan’s largest publisher, released a hefty single volume hardcover history of Japan entitled Gakushu Zukan Nihon no Rekishi (Illustrated Study Guide – History of Japan) and edited by Kasahara Kazuo. At several times the length of middle school textbooks, the volume provides more detailed coverage of historical events including wartime atrocities. It is widely available in school and public libraries and the book is designed to provide teachers with material to supplement officially approved textbooks.

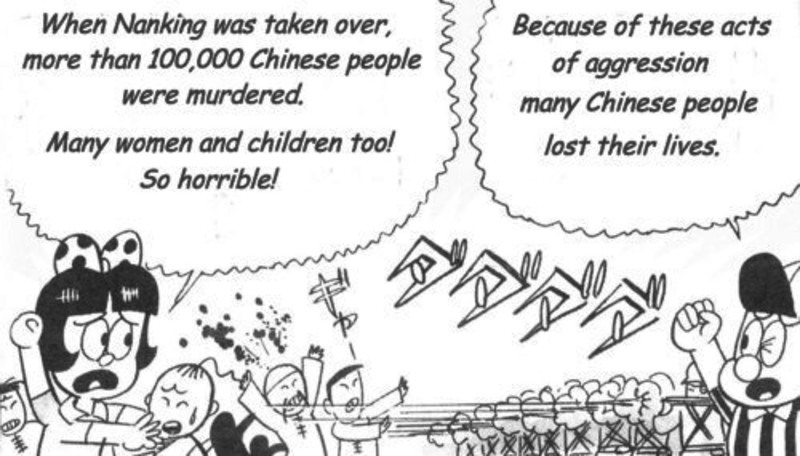

Study Section: The Japanese Army spread the fighting throughout China and carried out a “Great Massacre” at Nanking

Within a month of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident [July, 1937] the Japanese Army attacked into central China as far as Shanghai. However, they met with strong resistance from the Chinese and only captured the city after three months of fierce fighting. After this, the Japanese army aimed to capture the capital of Nanking in one stroke, pushing the troops forward. The assault on Nanking was fierce.

Unarmed women and children and other civilians were killed and the Japanese army caused a “Great Massacre” including looting and [all sorts of] violence…. We do not know exactly how many Chinese people were slaughtered by the Japanese army in this way but the Chinese side places the number as high as 300,000 including women, children, and other civilians. The “Nanking Massacre” was strongly condemned all over the world.

Japanese soldiers attacking Chinese civilians |

The same page features this photograph of Chinese wartime graffiti captioned “The Cruelty of the Japanese Devils” |

Manten Gakushu Manga Nihon no Rekishi

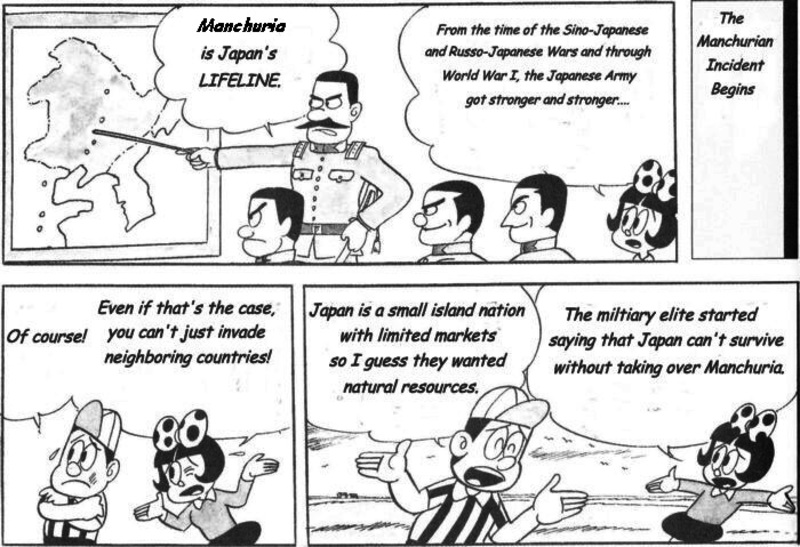

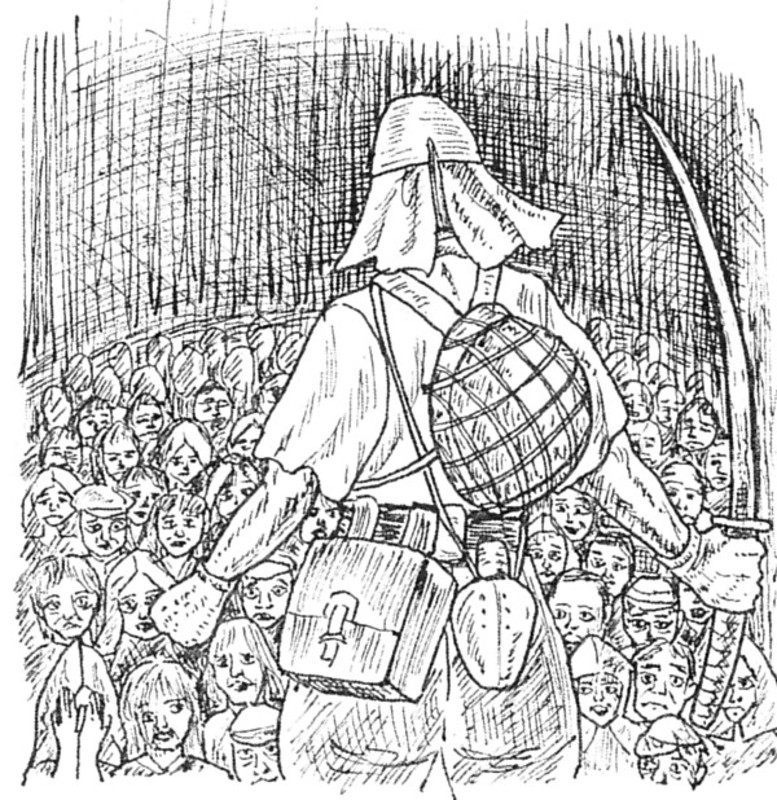

Publisher Gakken produces a wide variety of history books and is perhaps most famous for its offerings for military technology buffs. A different approach is evident in Manten Gakushu Manga Nihon no Rekishi (Full Marks Study-Guide Manga History of Japan) first released in 1993 and in a new edition in 2007. This large format single-volume manga history of Japan is commonly found in school and public libraries. Manga images should be read in Japanese manner from RIGHT to LEFT.

|

|

|

|

|

Tanoshii Shakaika no Jugyo Tsukuri (Roku nen)

The title of a 2009 collection of classroom resources designed to be photocopied by teachers and distributed to students translates as “Making Enjoyable Social Studies Classes”. The work, designed for students in the sixth year of primary school, does not, however, let “enjoyable” classes interfere with critical assessment of Japan’s wartime past.

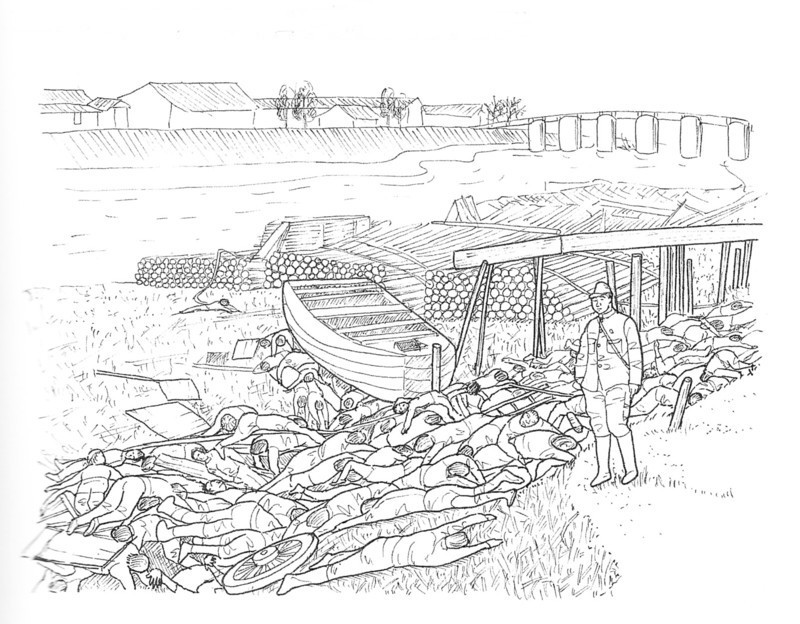

Japanese troops enter Nanking |

The aftermath of mass killing at Nanking |

A Japanese soldier forces Okinawan civilians from their hiding place |

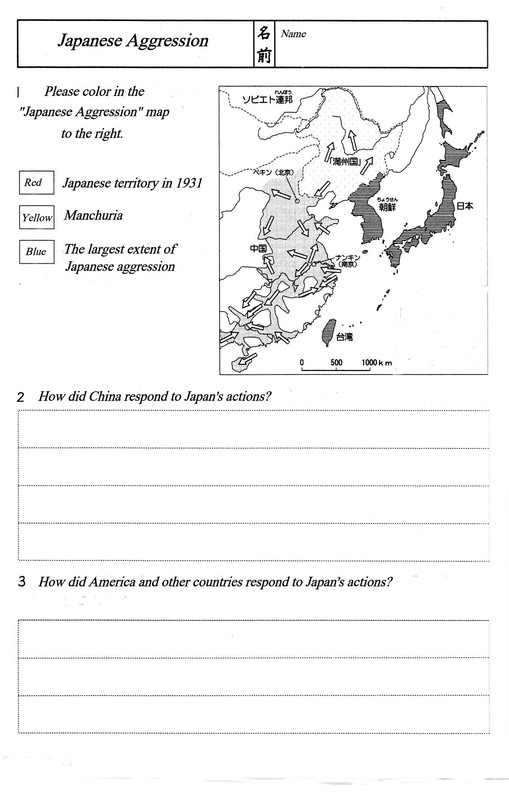

Marugoto Shakaika (Roku nen)

“Complete Social Studies” is another title that offers sample tests and handouts for students in primary school year six. The following is an English translation of a sample test on “Japanese Aggression”.

|

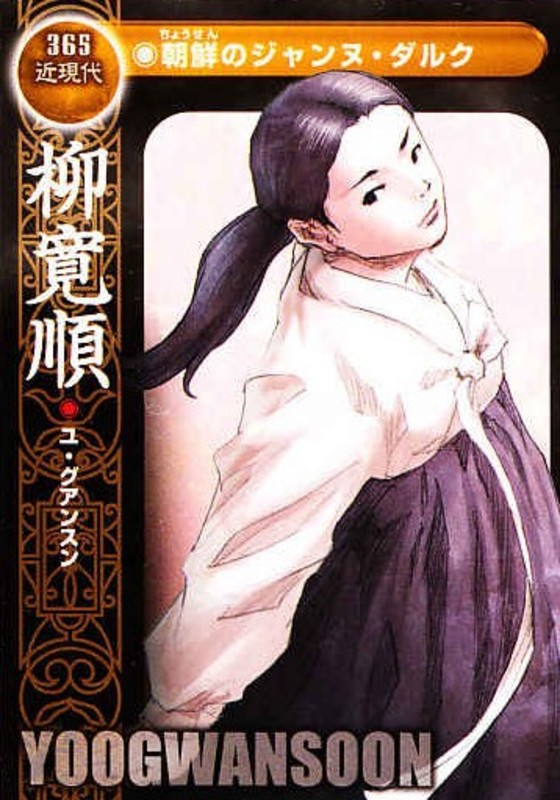

Manga Nihon-shi

The “Asahi Junior Series” consists of serialized thirty to forty page magazines on educational topics. The Manga Nihon-shi (Manga: History of Japan) component is a planned 50 volume set published weekly through 2009 and 2010. The individual issues combine manga vignettes of important scenes in Japanese history with photographs, excerpts from primary sources, and text by prominent historians and educators. Meant to serve as a study guide for young students, the issues contain a variety of educational supplements including “collector’s cards” of famous figures in Japanese history drawn by manga maestro Fujiwara Kamui, famous for adaptations of the hit videogame Dragon Quest (Dragon Warrior in English) . One card included in the forty-first volume profiles Korean student Yu Gwan-sun (1902-1920) described as “The Joan of Arc of Korea”. The card details how she was arrested at age sixteen for protesting against the Japanese occupation of Korea and died in prison. The series has been a huge hit, selling over 5,600,000 copies.

|

Nani wo do Yomaseru ka

There are a variety of “guidebooks” to assist teachers in choosing titles for student reading assignments. Among them, the Nani wo do Yomaseru ka (What to have them read, and how to have them read it) series from 1994-1995 emphasizes war works. The following is a translation of an entry on one of the most widely read accounts of the Battle of Okinawa.

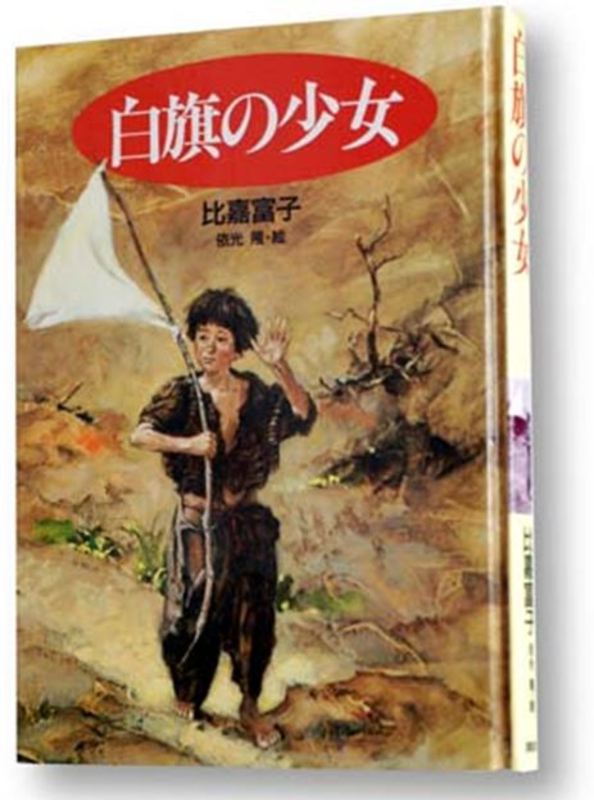

Shirahata no shojo (The Girl with the White Flag)36

Higa Tomiko

Kodansha, 1989

|

Summary

In the final stages of the Pacific War, American troops landed in Okinawa and launched an all out assault. The author, who was seven years old at the time, fled to the southern part of the island with her brother and two sisters, but along the way, her brother died and she became separated from the others. Alone on the battlefield, walking a thin line between survival and death, she met an elderly couple who had sought shelter in a cave. They implored her to survive no matter what and, grasping a white flag, she surrendered to the American troops and was reunited with her sisters.

Points for Instruction

The Battle of Okinawa was the largest scale fighting of the Pacific War and the only battle fought on Japanese soil. In the fighting, the casualties suffered by the army were dramatically outstripped by civilian deaths and it is said that the victims number more than 100,000.

Okinawans were blown away in the shelling, lost their lives to hunger and disease, were pushed to throw away their lives in mass suicides, and there were even those accused of spying for the enemy who became victims of the Japanese forces. Ordinary civilians were cast into the thick of the fighting and enduring unimaginable things, tasted the absurdity and savagery of war.

Students can] take from this experience-based narrative some of that absurdity and savagery. They will have an opportunity to consider anew what war means in a “peaceful society” where memories of war are becoming ever weaker.

War and Humanity

The suffering and violent deaths of soldiers is central to war, and at the same time, there are near limitless examples of civilians being pulled in as well. Children, women, and the elderly are the most common victims. This work portrays frankly the horrors of war from the point of view of ordinary civilians. It presents a strong opportunity for students to take away some understanding of this.We often hear that war drives people to madness. It is almost as though the extreme experience that we call “warfare” transforms people into something other than human. As is common in literature on the theme of war, this work sketches scenes of soldiers who have lost themselves. Soldiers push a child who has been crying loudly and its mother out of a cave, watching as they are cut down by machineguns. There are other scenes of soldiers, fearful that the moans of injured comrades will give away their position to the enemy, murder their fellows without mercy. Students can take away from this an awareness of the terrible weakness of human beings who will do anything, no matter how evil, to survive.

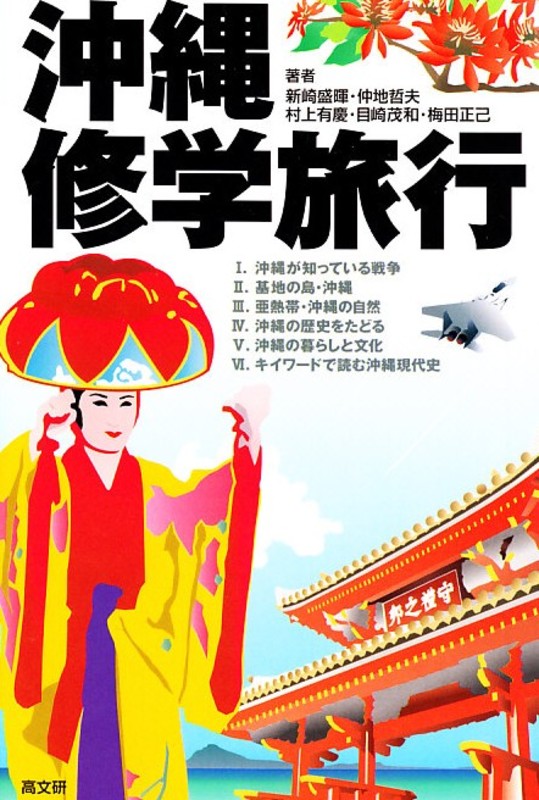

Okinawa Shugaku Ryoko

|

The following translation is from the educational supplement and travel guidebook Okinawa Shugaku Ryoko (Class Trips to Okinawa) published by Kobunken in 2005. Many Japanese high schools and junior high schools take an annual field trip. Okinawa is a popular destination for class trips and Okinawa Shugaku Ryoko is designed to give teachers a comprehensive background in Okinawan history and current affairs so they can better guide their students. The book is especially strong in its coverage of Okinawan war experience. The diversity of its description of the fighting in 1945 and the way that it contextualizes war and empire are evidenced by a detailed description of the involvement of Koreans in the Battle of Okinawa.

The Korean military laborers and “comfort women” who sleep in darkness

In the nine years since the “Heiwa no Ishiji” (Cornerstone of Peace) was unveiled [in the Okinawan Peace Park], it is the names of Korean war dead that have increased most noticeably. At the time of the unveiling, there were 51 names… but by 2004 that number had increased to 341. The total may not be high, but it increased by nearly 7 times. This is because of the efforts of [Korean scholars to provide the names of the war dead]….

… at the time of the Battle of Okinawa, the Korean Peninsula was a colony of Japan and many [Koreans] were forcibly brought to Okinawa against their will as military laborers and forced to labor in the construction of military bases and airfields and to carry weapons and ammunition…. [Scholars] estimate that they numbered between 10,000 and 15,000 people.

Of these, it is feared that at least several thousand lost their lives in that hellish battle. However, the Japanese government has done nothing to investigate. Okinawa Prefecture was given nothing but a list of a mere 420 names prepared by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. In addition, these names were all in Japanese style. During the colonial domination [of Korea] the Japanese government introduced policies of homogenization and apart from the enforcement of Japanese language education in schools, [many Koreans] were forced to discard their Korean names and take on Japanese ones.

At the request of the Okinawa Prefectural Government and with that list in hand, [Korean scholars] followed what threads they could, seeking out relatives of the deceased all over Korea and in the 8 years after 1996, saw to it that 290 names were added to the “Heiwa no Ishiji”.

However, despite strenuous efforts to locate them, there were some surviving families who said ‘no matter what the form, we simply cannot bring ourselves to cooperate with Japan”… even after more than half a century, the deep wounds left by colonial domination have not faded.37

Apart from the forced laborers, many young women were forcibly brought to Okinawa from the Korean Peninsula as ‘comfort women’. It is believed that their number exceeded 1000. The United Nations Commission on Human Rights has deemed them “sex slaves”.

From military documents and the testimony of local people, it is thought that there were around 130 prostitution facilities established by the Japanese forces throughout Okinawa. It is believed that Korean women were held at 64 of them.

These prostitution facilities were concentrated in the south-central part of the main Okinawan island. Naturally, they were caught up in the “Typhoon of Steel”… However, the number of dead is still shrouded in darkness.

In the same area that contains the “Heiwa no Ishiji” there is a monument to the Korean war dead… It was built in 1975. On it is carved, “In 1945, during the Pacific War, many young Koreans were forcibly drafted by Japan and sent to the front lines on the continent and the South Seas. On this Okinawan ground as well, over 10,000 draftees met with hardship, death, or were victims of massacre, tragically sacrificed.”

There are over 300 monuments to the war dead in Okinawa, but those two characters 虐殺 “gyaku satsu” (literally “cruelty” and “murder”, massacre) are carved on only two, this one and one on Kumejima. On Kumejima, Japanese civilians and an entire Korean family, 20 people, were slaughtered by Japanese soldiers on the orders of their commander, Shikayama.

‘Field Work’ Yasukuni-jinja, Yushukan

Kyozai publisher Heiwa Bunka has produced a line of guidebooks to war-related sites across the Asia-Pacific region. This volume ‘Field Work’ Yasukuni-jinja, Yushukan (Field Work – Yasukuni Shrine and Yushukan Museum), edited by the Tokyo no Senso Iseki wo Aruku Kai (Group for Touring Tokyo War Relics), was released in 2006. It is organized as a guidebook for teachers who wish to turn a class trip to the controversial shrine into an opportunity to reflect critically on Japan’s wars.

Introduction

The problems surrounding Yasukuni Shrine are now becoming a major issue. One of the most important problems is Prime Ministerial worship at the shrine. Former Prime Minister Koizumi made worshipping at Yasukuni into an official pledge and went to worship every year. In addition, Prime Minister Abe, who took office in September of 2006, has said that “I decline to say if I will go our not” and also “Nobody has ever been judged to be a war criminal by our laws.”38

The pattern by which Prime Ministerial worship causes our relationship with Asia to freeze over has still not been broken. The “Keizai Doyukai” (Japan Association of Corporate Executives) and “Nippon Keidanren” (Japan Business Federation) have both released statements critical of Prime Ministerial worship. Critical voices have also been raised in America. In the background of all of this are the strong criticisms of Asian people who take Prime Ministerial worship at Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines the spirits of the Class A war criminals who lead the war of aggression, to mean that there has been no sincere reflection on the war. Recently, Watanabe Tsuneo, the President of the Yomiuri Shimbun, has asserted that the problem rests not only in the controversy surrounding the enshrinement of the spirits of A class war criminals, but also the “affirmative view of the war” evident in the Yushukan museum exhibits, and puts it that all military action in Asia from the time of the Manchurian Incident should be viewed as a war of aggression.

During all of this, the Yushukan Museum has heeded American criticisms and is moving to alter the exhibits, but there is no indication that they have responded to criticisms from Asia. In the postwar period, which has gone on for well over 50 years, the questioning of Yasukuni Shrine’s war responsibility and postwar responsibility continues.

Through [the controversy] surrounding Yasukuni Shrine, the issue of religious freedom can also be considered. The constitution bars the support of any specific religion by the state. There has even been a court judgment that Prime Ministerial worship is unconstitutional. In addition, there have been suits from families of Christian believers and others to block enshrinement.

Walking the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine and viewing the exhibits of the Yushukan Museum, lets us consider the problems surrounding Yasukuni from the point of view of making Asia into a peaceful community that exists without war.

What are the Yushukan Museum exhibits saying?

The Yushukan was opened as a military museum in 1882. It was mostly destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake and moved to a temporary building before the new museum hall was completed in 1931. In the postwar period, by order of the occupation authorities it was changed to the Yasukuni Shrine Treasure Hall … but in 1986 it was renovated and restarted as the Yushukan. In July 2002, the entryway was expanded and the content of the exhibits was completely redone.

What is on display in the exhibits at the Yushukan, which run chronologically from the arrival of Perry and the Boshin War at the end of the Edo Period to the completion of the San Francisco Peace treaty, is the “Yasukuni view of history”, which is colored by the “Imperial view of history” which has it that the emperor is a god and also that “the Tokyo Trial was one-sided victor’s justice” showing no reflection on Japan’s aggression against Asia.

No mention of the damage caused by war

The exhibits of the Yushukan Museum paint Japan’s wars as for “self defense and survival”, and as a struggle for the liberation of the various peoples of Asia from the Western Powers. The word “aggression” does not appear. The names of the wars such as the “Manchurian Incident”, the “China Incident”, the “Greater East Asia War”, and others, are used just as the government and military elites did at the time so as to not acknowledge that they were in fact wars of aggression.

When it comes to the damage suffered by ordinary people, only the number who died because of the atomic bombs dropped by America, 200,000 in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki, are detailed, while the 3,100,000 Japanese and over 20,000,000 Asians who are thought to have died in the 15 Year Japan-China War and the Asia-Pacific War go unmentioned. The major feature of the Yushukan Museum exhibits is that there is no explanation of the reality of Japan’s colonial domination and aggression.

How should we respond to criticisms from the countries of Asia?

Prime Minister Koizumi’s worship at Yasukuni Shrine was the subject of strong protests from Korea, China, and other Asian countries. The contradictions in Japan’s relations with various Asian countries were only deepened and meetings with the leaders of Korea and China stopped taking place.

In China, there are survivors and families of victims of the Nanking Massacre, and other incidents of massacre of ordinary people, of Unit 731’s human experiments and biological warfare, of poison gas, of the bombing of Changde and other areas, and of forced labor in mines and factories, the victims of the war of aggression. In Singapore there are surviving families of those massacred by the Japanese army as spies or for other reasons. In Korea are those made into “Comfort Women” and forced laborers or their surviving families. Criticisms center around the idea that avoiding looking clearly at those burdens of war and worshipping at Yasukuni Shrine where the spirits of the Class A War Criminals responsible for that war are enshrined, is to avoid acknowledging the historical fact of aggression. We can call this the problem of “historical awareness”. Certainly, when you view the exhibits of the Yushukan museum that is run as a part of Yasukuni Shrine, you can see no reflection or apology for Japan’s wars against Asia, and the fact is that things are strongly colored by the Yasukuni Shrine view of history, which justifies the war. America is also expressing misgivings toward this.

To answer these criticisms, Prime Minister Koizumi says “my worship is done with anti-war sentiments” and that “the government reflects apologetically on the wars of the past”. He also says that the Yasukuni view of history and the historical awareness of the government are different. However, to worship at Yasukuni Shrine where the spirits of the Class A War Criminals are enshrined, and whose Yushukan Museum well articulates the war perspective of imperial era, also obscures the war responsibility of those who brought about the war of aggression.

Aruite Mita Taiheiyo Senso no Shimajima

Since the late-1970s, the Iwanami Junior Shinsho series has been Japan’s leading collection of non-fiction works for children. Reflecting the progressive orientation of publisher Iwanami Shoten, the series, a staple in school libraries and for student research and book reports, includes a number of volumes that deal critically with war legacies. Aruite Mita Taiheiyo Senso no Shimajima (Walking and Observing the Islands of the Pacific War) was released in March 2010 in time for assignment as summer reading on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of Japan’s 1945 surrender. The book was written by Yasujima Takayoshi a photographer and travel-writer who has walked the world’s battlefields, and overseen by Yoshida Yutaka, one of Japan’s most pre-eminent historians and a prolific author on Japan’s war history.

|

“The Island of Starvation”

Guadalcanal is often called “ga-to” (a play on the first syllable of the island’s name, combining the characters for “starvation” and “island”).

The reason is that most of the [Japanese] soldiers who died in the Battle of Guadalcanal were not killed in combat… but died from starvation, malnutrition, or from related diseases.

In the case of the army, soldiers went into battle with about a week’s worth of food. They could either finish the operation in that time or, if the fighting dragged on, could wait for resupply. If that did not come, they were left with just three choices – plunder, starve, or fight to the last.

…

Soldiers on Guadalcanal came up with a way of measuring how much life they had left:

If you can stand – 30 days

If you can sit up – 3 weeks

If you piss yourself in your sleep – 3 days

If you can’t talk – 2 days

If you can’t open your eyes – tomorrow

…

Those who were lucky enough to be evacuated from Guadalcanal finally got access to food. However, soldiers who were on the verge of starving to death often met with tragedy… Bodies long in a state of starvation could not take the shock [of a full stomach]. There were many soldiers who died and even now, not much is said about this.

The military elite were frightened of the prospect of ordinary Japanese finding out about the horrifying experiences of soldiers on Guadalcanal so they immediately sent the men who survived on to other battlefields.

They wanted people to think that the Emperor’s August Forces fought to the end with bravery and valor for the sake of the homeland, and wanted talk of starvation to simply disappear… In the end, the deaths of these men were reported as “honorable deaths in battle in Japan.”

The Bataan Death March

The Japanese forces attacked the Philippines at the start of the Pacific War. At that time … the “Bataan Death March” took place. American and Filipino prisoners were forced to march under the blazing sun for over 80 kilometers to a prisoner of war camp and thousands upon thousands died.

The spot is marked with monuments along the road carrying similar images of soldiers suffering, collapsing, and dying… The monuments, which look like gravestones, have been built to pass on knowledge of the suffering of the soldiers and the evil deeds of the Japanese forces.

What I learned upon visiting the Bataan Peninsula … is that most of the victims were Filipino.

Kangaeru Nihonshi Jugyo

Doshite Senso suru no, Kangaeru Nihonshi Jugyo (Why Make War? Thoughtful Japanese History Class) published by Chirekisha in 2007, is a teaching supplement made up overwhelmingly of student perspectives. Author Kato Kimiaki is a veteran high school teacher who strives to organize high school history classes around student discussions with an aim to “…break away from passive education.”(p. 12) The book is a guide for other teachers who wish to do the same. This is an important source for assessing contemporary Japanese education as the students not only discuss history, but also problems of history education. The student quotes that Kato presents offer a fascinating glimpse inside the classroom as students engage with difficult themes. It is also important to note that Kato allows all sorts of views to be aired. While the sources that he shares with students, including video testimony by Japanese perpetrators of war crimes, speak to a progressive approach, students differ considerably in their discussions of important themes such as the overseas dispatch of the Japanese Self Defense Forces and whether or not it is appropriate to introduce the stories of former Comfort Women at the middle school level. The right have accused progressives of enforcing a one-sided orthodoxy in their classrooms, but in Kato’s collection, this is not the case.

Understanding the Victimizers

In this section Kato encourages students to consider atrocities carried out against Chinese civilians from the point of view of the Japanese perpetrators.

Student Views

Let’s build mutual understanding as human beings

It is possible that we may have to strengthen the Self Defense Forces [so that they can play a more important global role]. There are things that we have to consider, however. I think that if Japanese soldiers [in the 1930s and 1940s] had known what type of people the Chinese villagers were, how many were in their families, and what they were striving for, there is no way that they could have killed them. From now on, more and more, and not just with Chinese, it is necessary for us to get to know people from outside Japan and build mutual understanding as human beings together.

Suzuki

The Japanese military viewed people’s lives as garbage

In the diary of division head Nakajima at the time of the Nanking Massacre, it doesn’t say “killed”, it says “disposed of”… With things like this and the “burn all, kill all, loot all” “three all” strategy it seems that the Japanese army had started to look at people’s lives as mere things or even as garbage.

Nagai

People were made to accept the beliefs of the Japanese military as absolutely just

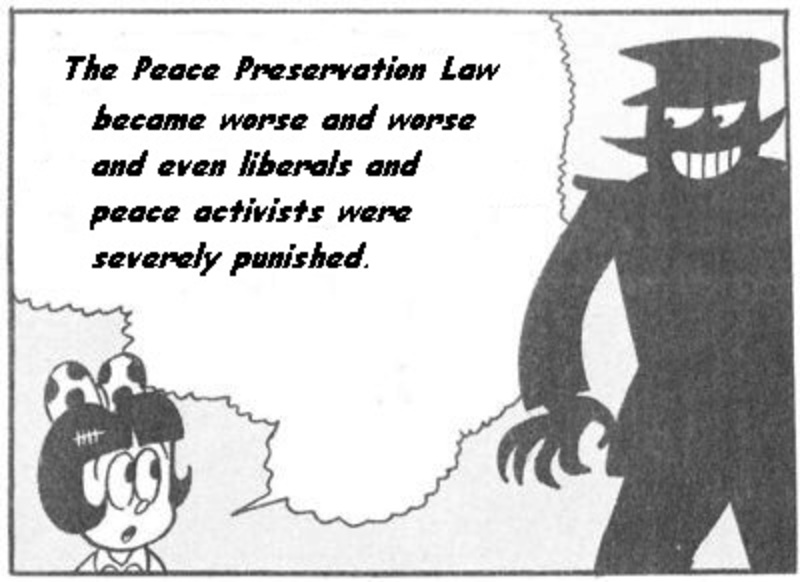

In the militarist era, the military leadership were given priority over everything else and anyone who opposed this was thoroughly crushed. The Peace Preservation Law was first used to crack down on socialists and communists, but eventually even university professors and novelists were targeted and criticism of the government and the military elite was silenced. In schools, it was taught that domination by the imperial system was justified by the imperial view of history. Because the emperor was the head of the military, people accepted that the beliefs of the Japanese military were absolutely just.

Kondo

For the sake of returning to one’s family

I think that they came to believe that they had to keep killing people in order to survive themselves. Their families were back in Japan. In order to see their families again they had to win the war and return to Japan. So in the end, they probably started to think that in order to win they just had to kill whoever was in front of them.

Tanaka

In order to avoid becoming victimizers, we have to reevaluate our relationship with America

So as to not produce any more people like Mr. Yamamoto, we basically have to make sure that there are no more wars, but as a realistic problem, this just isn’t plausible. Japan has abandoned war, but can we really say that sending troops to Iraq isn’t participating? At that time, if the troops were in danger… can we really say that they wouldn’t become involved in the fighting? Making war always equals producing victims and victimizers. We can limit the number of victimizers, but making that number zero is impossible, isn’t it?… In the near future, Japanese troops will probably be dispatched to a war zone again. If that happens, there will definitely be victimizers… if we really want to make sure that there are no victimizers, we have to stop sending troops…. Now, the Japanese government is putting a lot of weight on our relationship with America. Because of this, they are making efforts to do what America says. However, can we really call this a diplomatic relationship? Shouldn’t we be calling it subservience? Because of this it has become impossible [for us to say] that we won’t make any more people into victimizers. So as to not create more victimizers, we have to rethink our foreign relations. Isn’t this the only thing that will make zero victimizers possible?

Shirakawa

Even if the power of one is small, if many people combine their power, the political direction can be changed

In peacetime, everybody says the same thing so it is easy to say “down with war”. It is when war is about to begin and there aren’t many people on your side that saying “down with war” starts to get hard. “Down with war” gets really hard when you have to be prepared to stand alone. There are things that we can and cannot do. However, even if the power of one is small, if many people combine their power, the political direction can be changed… Every one of us has to take a fresh look at war [not as something abstract but] as a problem important to us all.

Umino

Educational Value, Teaching Methods, and the Comfort Women Issue

Kangaeru Nihonshi Jugyo also contains a discussion about the comfort women and the inclusion of their stories in Japanese education.

Student Views

Just what [Japanese] people are we talking about here?

Are Japanese really a perverse and stupid people? Why is it that scholars and critics say “this country is this way” or “this race is that way” and make distinctions that come pretty close to racism? If there are Japanese who are like that there are also Japanese who are not like that. We can say that about the people of any country. We can’t measure the personality or character of individual human beings based on culture, religion, or social systems. When we look at it a bit more broadly, people really aren’t all that different. Scholars who define “Japanese” as being like this or that are the ones who are off.

G

Wait until high school

I can’t really agree with including [comfort women] in textbooks for middle school students. Middle school is the height of adolescence when kids have their strongest interest in sex, start to become aware of it and struggle with it, they’re still too young to really deal with such an issue… However, on the other hand, I also feel that in this important period, it might be good to have them think about it when their minds are still flexible. In the end, however, I think that high school is the right time.

I

They can study it sincerely from the third year of middle school

Can middle school students really grasp something like that? … Compared to first year students, I feel that third year students have really become adults and can come to grips with problems relating to sex. When I was a third year, we had sex-separate sex education classes and had a serious discussion about prostitution. This is why I think that the third year of middle school, that time is the best period to study the [comfort women] issue seriously.

Kadokawa

I’m glad to have been taught

Some people still seem to think that [learning about the comfort women in middle school] has no educational meaning, but on that subject, I was taught about the comfort women by my teacher in middle school social studies class. At that time I felt “why on earth is something as important as this not in the textbooks?” Even more than Japan’s past behavior, it is the attitude of the current Japanese government that really makes me mad…. Right now, I think that Japan is a country that does not acknowledge its responsibilities in a lot of ways. Even if there is no clear [documentary] evidence (is [the government] hiding it?), people who used to be comfort women have come forward and are giving testimony so I think that Japan just can’t keep dodging it and has to find some way to settle this issue. Also, in order for us to face international society, we simply must have accurate knowledge of this…. I think that today’s middle school students are no longer children. They know about more things than we think. Even if people say that it is too early and middle school students should not be taught about [the comfort women], I am glad that I was taught and think that it should be taught.

F

It will become a big disadvantage for international exchange

… Just how teachers should approach [communicating this issue] to middle school students is a difficult problem. However, that problem and the reason why we teach historical truths are two completely different things… [We cannot simply] teach what is most convenient for us. One of the most important themes that follows from the comfort women controversy is the issue of the human rights of comfort women and without this we cannot hope to understand or study seriously issues like human dignity and human rights. Also, in this era of globalization, if we turn our eyes away from this problem which is already well known all over the world … it will inevitably become a big disadvantage for international exchange.

Inoue

Isn’t this just too difficult for middle school students?

We shouldn’t run from the truth. It is we who will inherit the future and with this in mind, it is absolutely necessary for us to know everything [about things like the comfort women], and when we consider the victims, I think that it is only natural that we have to know. However, we are now high school students, we see people the same age as us already out working and even married, so we are in a position to have a very different view of the world than middle school students. Middle school students are like kids, can they really take in the [issue of] the comfort women like we can? In the end, I think that it isn’t possible.

Hirano

Why did they use Korean women?

This problem took place because discrimination against women was added to discrimination against Koreans. When we consider why they used Korean women, at the time Japan had laws like “It is unacceptable for any reason to have females under the age of 21 perform acts of prostitution” and “Even with adult women, it is unacceptable to kidnap or force them.” But these laws didn’t apply to Korea… and other colonial areas. [From these laws] we can tell that, even if just a bit, the Japanese government acknowledged that prostitution wasn’t a good thing, but I think that it was because of discrimination against Koreans and other people that prostitution and forced labor were allowed in colonial areas.

Kadokawa

Bokura no Taiheiyo Senso

Bokura no Taiheiyo Senso (Our Pacific War), published in 1973 by Hata no Mori Shobo, was the culmination of a class project in which Tokyo middle school teacher Honda Koei had his students read translated descriptions of Japan’s wars of the 1930s and 1940s in the textbooks of other Asian countries. Students did research on particular aspects of Japanese war and imperialism, even writing to the embassies of various countries in search of accurate casualty figures. At the culmination of the project, Honda had students write letters to young people elsewhere in Asia. The letters, while reflecting different levels of maturity (and coherence), are important documents of a teacher’s attempt to utilize resources appearing in the early 1970s such as Honda Katsuichi’s Chugoku no Tabi (Journey to China) reportage on the legacy of the Nanking Massacre. They trace a path from reflection on history to deeper engagement between Japan and Asia on both personal and national levels.

Niki Rie

Greetings my Asian friends. I wonder if you hate Japan because of the Pacific War. As a Japanese, I feel ashamed because of the tragedy caused by Japan’s cruel ways. In the past, my fellow Japanese sacrificed many Asian people and then ended up meeting with destruction and finally defeat. I don’t think that this defeat is sad, instead I’m glad. If I had been around at the time and seen what Japanese people were doing to other people in Asia, what suffering they caused, I would have turned against Japan and tried to help Asian people I think… From now on we have to make sure that there are no more wars. Some people in Asia may still want to get back at Japan, but I think that this will only end up hurting all of us. All that will be left behind is hatred. Let’s try to get along and work to build a peaceful world together.

Even before Japan and America, the Philippines were dominated by Spain. [As colonial overlords changed] the Philippines became a battlefield again and again and many civilians lost their lives.

Kio Hirosada

To our friends in Asia. I feel I can’t say enough to apologize. Japan launched a war of aggression against Asia and did many things. Did many bad things to your fathers and mothers. Maybe they still hate Japan to this day. Please, if only just a little, forget the Japan of the past.

A long time ago, my father also went to Asia. He was a lieutenant. But he didn’t try to kill your fathers because he was evil. He was forced to do it against his will. Even if I say this, I don’t think that you will understand. However, I have been learning about Asia from my Social Studies teacher Mr. Honda and thinking about a lot of things. While starting a war of aggression against Asia, Japan was saying things like “we will free Asia from American domination and let Filipinos build their own country.” But the Japanese army killed one Asian person after another, killed thousands upon thousands… It was because Japan did this that we were abandoned by even the gods and defeated in the war.

From here on I want to get along with people in Asia and deepen our friendship. Let’s be friends.

Nakane Kazuhiko

I have bad feelings about Japan’s past. Why did they have to do things like that during the war? Murdering civilians, taking whatever they wanted, I thought ‘did they have any humanity?’

I think that it is only fair that people in Asian countries hate Japan. I’m not from there so I don’t understand their pain. However, just reading from [Asian] textbooks, I understand that the Japanese army did very terrible, inhuman things.

“No less than 300,000 people were killed in Southern China.” What were they thinking killing innocent people?

Next, in North China, they did cruel things called the sanko (Three All – Loot All, Burn All, Kill All) operation. I struggle to understand why they had to do something like that.

…

I really feel sorry for Asian countries. You will probably think that what I have written isn’t good enough but I just don’t know what I should write about Japan’s behavior and the suffering of people in Asia. I can just speak out about Japan’s stupidity.

…

Now, I think that a lot of Japanese reflect apologetically about the war and its really the government that hasn’t shown what we can go so far as to call any remorse. We have to be very critical of this… Even in this Japan, please don’t forget that there are people that reflect and show remorse.

Sakata Masahiro