Translation and introduction by Zeljko Cipris

Yamamoto Yuzo (1887 – 1974) was a playwright and novelist from Tochigi Prefecture who graduated from Tokyo University. He made his debut as a dramatist with Seimei no kanmuri (1920; tr. The Crown of Life, 1935). An admirer of such playwrights as Henrik Ibsen and Gerhart Hauptmann, Yamamoto also translated August Strindberg’s plays, wrote popular and critically acclaimed novels and children’s literature, and helped found the Japanese Writers’ Association with Kikuchi Kan and Akutagawa Ryunosuke. During World War II he spoke out against the government’s censorship policies, and after the war served in the Diet on Japanese language reform, advocating limited use of complex ideograms (kanji). He was awarded the Order of Cultural Merit in 1965. After his death, his European-style home in Mitaka, Tokyo, was converted into a museum. His drama Infanticide (Eijigoroshi) was published in 1920.

|

Yamamoto Yuzo, 1938 |

Yamamoto’s literary work comprises a critical examination of the human condition based on the author’s humanistic philosophy. Though he is not considered to be one of Japan’s proletarian writers, whose politically radical literature was most prominent in Japan during the 1920s and early ‘30s, Yamamoto was highly sympathetic to the revolutionary movement.

|

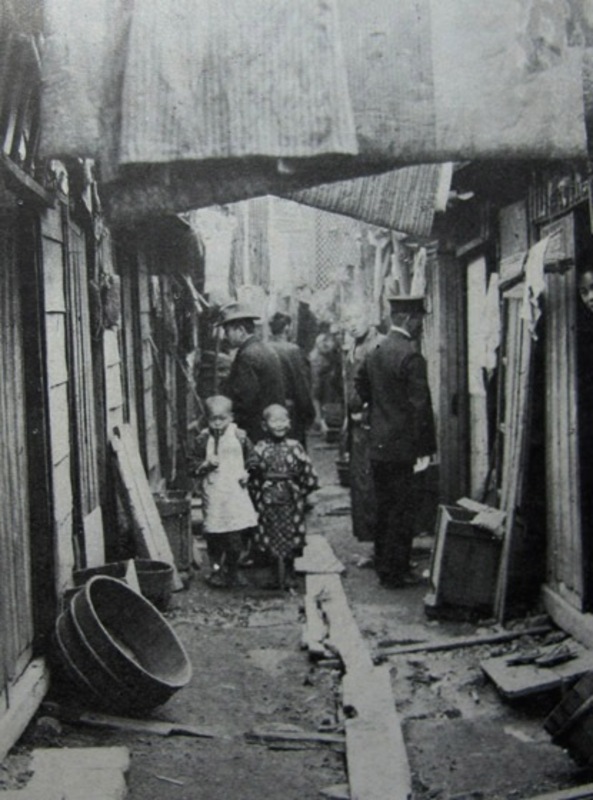

Tokyo street scene 1920 |

As is evident from the play presented here, the eponymous murderer is ultimately not the destitute day laborer – nor for that matter the impoverished policeman – but rather a criminally structured, polarizing socioeconomic system that inexorably continues to produce countless harrowing tragedies among the dispossessed. Yamamoto’s play constitutes a poignant cri de coeur, yet leaves the solution to the underlying problem up to its audience. Roughly a century after the play’s original production, the search for a solution of international proportions remains as vitally important as ever.

A One-Act Play

POLICEMAN KOYAMA KEISUKE, about forty-three

TSUGI, his daughter, about seventeen

A RAG DEALER

A PEASANT

A NEIGHBOR’S WIFE

A FISH-STORE APPRENTICE

DAY LABORER UJIHARA ASA, about twenty-nine

Spring, circa 1913, a rural district adjacent to a city

A police substation doubling as a residence. Living room and kitchen directly adjoin the police office. A closed kitchen door of latticed paper-screen forms the rear entrance. Cherry blossoms peer through a latticed kitchen window. It is twilight.

TSUGI is sitting vacantly in the living room. POLICEMAN KOYAMA opens the glass door to the substation and enters.

TSUGI: Welcome back.

KOYAMA: Hullo. Such terrible dust!

Takes off his shoes and steps up

TSUGI: Better change your clothes right away.

TSUGI rises and holds out to her father a kimono to change into.

KOYAMA: Yes, I’ll do that.

Taking off his uniform and changing into the kimono

Huge crowds out there, coming to look at the cherry blossoms.

TSUGI: Yes, it seems very lively. Many people have been passing this way to view the blossoms.

KOYAMA: Well, I’m off-duty tomorrow so I’ll stay at home. Why don’t you go out to see the blossoms?

TSUGI: Me?

KOYAMA: You are so exhausted from nursing the sick, you’re looking very thin. You should go look at the blossoms and cheer up a little.

TSUGI: I don’t want to look at the blossoms. Somehow, my strength’s all gone and no matter what I do, nothing interests me at all.

A RAG-DEALER passes in front, shouting: “Rags, rags!”

KOYAMA: I know what you mean.

TSUGI: When I see people who feel all cheerful over the cherry blossoms, I hate them.

RAG-DEALER’s voice again: “Rags, rags! Any rags for sale?”

KOYAMA: It’s a rag-dealer. Won’t you call him in for a minute?

TSUGI: Yes.

Quietly calls to the RAG-DEALER from the kitchen window

Mr. Rag-dealer, Mr. Rag-dealer!

RAG-DEALER (opening the rear door): Did someone call from here?

KOYAMA: Mr. Rag-dealer, won’t you come in?

RAG-DEALER: Ah, thank you for your business, Sir. What fine weather we’re having, aren’t we. (Enters the house)

KOYAMA slides open a closet door, takes out six or seven items of clothing from an old trunk, and shows them to the rag-dealer

KOYAMA: Mr. Rag-dealer, would you be interested in things like these?

RAG-DEALER: Ah, kimono. That’s excellent. I’ll give you a good price for it.

KOYAMA: All of it’s old though.

RAG-DEALER: Well, sir, there are all kinds of rag-dealers, and I happen to specialize in old clothing so I’ll give you a much better price than other dealers would.

|

Tokyo tenement 1920 |

Looking through the clothes

All women’s clothing, I see.

KOYAMA: My wife died.

RAG-DEALER: I’m terribly sorry to hear that. It must be very hard for you.

Still looking through the clothes

There’s children’s clothing mixed in, too.

KOYAMA: Right after her my son also died, so all these clothes are of no use any more.

RAG-DEALER: Your son. That must be awful for you. With that in mind, I’ll go all out to give you an especially good price.

KOYAMA: How much can you buy it for?

RAG-DEALER: Let’s see. (Calculates) For all of this, I’ll give you seven yen and fifty sen. An absolutely terrific price! Yes, indeed.

TSUGI: Father, that’s worth a lot more.

RAG-DEALER (picking up a woman’s spun-silk jacket): Do you mean this, young lady? But this is too quiet for you.

TSUGI: No, I don’t mean I want to wear it.

RAG-DEALER: If the collar on this were not half-width it would be fine, but unfortunately it’s been tailored to half-width, you see. Otherwise, I’d be able to pay you a little more.

KOYAMA: How about it? Can you make it a little more?

RAG-DALER: Hmm, well, let’s add three kan. I’d like to say eight yen even, but then there’d be no profit for me at all.

KOYAMA: Well then, let’s settle on that.

RAG-DEALER: Would that be all right? Thank you very much. (Extracting money from a wallet) Here we have seven yen, and here are eighty sen. Please count it to make sure.

KOYAMA (puts away the money): So how are things? Are you making out all right?

RAG-DEALER: I hesitate to tell you this, sir, but making a living has gotten terribly tough. Just getting enough to eat day after day is not easy.

KOYAMA: That’s so, isn’t it.

RAG-DEALER: Truth is, the world’s gotten very hard to live in. Why, lately there’s been women going out to work disguised as men, right?

KOYAMA: Newspapers have written about such things, yes. With women’s wages, they can’t get enough food to stay alive.

RAG-DEALER: What they’re doing makes perfect sense, since they can’t get enough food to live on. Being human is terrible; we must do all kinds of things to keep on eating. I’m sorry to have troubled you with such talk. Thank you very much!

(He leaves. As soon as he is outside, he resumes shouting as he walks)

Rags–anything to sell?

TSUGI: I feel such regret somehow, when we sell those clothes.

KOYAMA: That’s true, but when they’re here they make us remember and that isn’t good, so I made up my mind to sell them. Besides, I need to pay for medicines.

TSUGI: Ah, they’re not paid up yet, are they.

KOYAMA: And yet, you know, I really wish I’d been able to pay for more medicines.

TSUGI: But it was hard enough as it was; if you’d paid for even more it would’ve been impossible.

KOYAMA: But if I’d done it, they just might have lived.

TSUGI: Yes, it would’ve been good if we’d been able to get all the medicine we needed.

KOYAMA: When I think of it, I feel like I just left them both to die, and I can’t bear it.

TSUGI: Oh, that isn’t so. It wasn’t your fault, father.

KOYAMA: No, my fault is that I was powerless.

TSUGI: But the world is full of people who are short of money and so can’t do enough for the sick. It certainly isn’t only you, father. You shouldn’t blame yourself so much.

KOYAMA: That’s what makes it even worse, you see. How good it would be if all such things vanished from the world.

TSUGI: That’s true but, ah, if only we’d had a little more money…

KOYAMA: No use complaining. (Pause) Well, let’s eat. I’m famished.

TSUGI: Yes, let’s. Only we have nothing to go with the rice. Shall I go buy some tofu?

KOYAMA: I don’t need anything. Didn’t we have some beans?

TSUGI: We do.

KOYAMA: That’ll do, that’ll do.

TSUGI brings out a low table and sets out the supper. Meanwhile, KOYAMA switches on the light, and offers lighted incense at the Buddhist altar. Outside, the sun sets and it grows dark. Presently, the two sit at the table.

KOYAMA: Even sitting at the table like this, something is missing somehow.

TSUGI: If little Ken were here at least…

KOYAMA: Mm, how lively it would be if Ken were here… No, don’t think about it, don’t think about it.

The two begin to eat in silence. Suddenly, the glass door in front opens, and a PEASANT rushes into the police substation.

PEASANT: Is the master here?

TSUGI: Who is it?

PEASANT: A terrible thing’s happened; I’d like the master to come.

KOYAMA: Is something wrong?

PEASANT: Yes sir.

KOYAMA: Another theft?

PEASANT: No, nothing like that; it’s much worse.

KOYAMA: What is it?

PEASANT: There’s a baby in the bamboo grove.

KOYAMA: A baby?

PEASANT: Early this morning I wanted to take some bamboo shoots to the market so I climbed the hill back of the house and was digging for bamboo shoots when the tip of the hoe hit a dead baby. I knew I had to let you know so I came running here right away.

KOYAMA: I see. All right, I’ll be with you in a minute.

PEASANT: Thank you very much, sir.

TSUGI: Going out again, father?

KOYAMA: Mm, would you bring out the uniform for me.

TSUGI: Yes. (Takes out the uniform)

KOYAMA (putting on the uniform): Did you let the public office know already?

PEASANT: I sent a man just now. With this kind of thing, we couldn’t do anything without the authorities coming right away.

KOYAMA: Good thinking.

TSUGI: Father, your supper.

KOYAMA: I’ll eat it after I get back. But you go ahead and eat now.

TSUGI: All right.

KOYAMA: Well, see you in a while. (Leaves with the PEASANT)

(As TSUGI eats by herself, A NEIGHBOR’S WIFE enters through the rear door)

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Good evening.

TSUGI: Ah, madam! (She lays down her chopsticks)

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Oh, you’re having supper. Go right ahead and finish it.

TSUGI: Pardon me while I finish.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Tsugi, after you’re done eating, do you want to go to the bathhouse?

TSUGI: I’d like to go with you, but…

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Your father’s out?

TSUGI: Yes, he’d just gotten back but suddenly something came up so he went out again.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: He’s so busy, isn’t he. Did something happen?

TSUGI: It seems that a baby’s body was found in a bamboo grove.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Ah, how awful. You know, it must be some wretch didn’t know what to do with a child and so threw it away in such a place.

TSUGI: Yes, that must be it.

NEIGBOR’S WIFE: They’re such a nuisance, don’t you think, those who cause your father all the extra work? It isn’t easy for your father to have to go out there each time they do something.

TSUGI: But that’s his duty, so it can’t be helped.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: It may be his duty, but other people couldn’t do it. Yet why is it that there’s been so much misfortune in an honest family like yours. The wife and the son dying one right after the other…

TSUGI: It’s fate. That’s how I resign myself to it.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: You say it’s fate, Tsugi, but you’re having a hard time resigning yourself to it.

TSUGI: But there isn’t any other way to think about it. (She finishes supper).

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: The world is really mean, isn’t it. It makes me so angry I can’t stand it.

TSUGI (goes into the kitchen, and starts washing up bowls and chopsticks): What do you mean by that?

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Today too I thought hard about it while I was pasting matchboxes at the factory: As things are now, I don’t feel like a human being at all.

TSUGI: You shouldn’t feel that way.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: But I do, you know. It may be fate and all, but with things being like this, I think I’d be much better off if I were a match.

TSUGI: Ho-ho-ho-ho!

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: It’s nothing to laugh at, believe me. First of all, matches don’t get hungry. So they don’t have to work, and they don’t have to worry about getting bawled out by a supervisor–it’s a really carefree existence, isn’t it.

TSUGI: You don’t mean that.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Yes I absolutely do. Why, if you want to know with how much care the matches are treated, just come to my factory for a look. Mustn’t put them down, mustn’t get them wet, mustn’t get them too dry–I tell you, an only child of a noble family doesn’t get handled with so much care. But on the other hand, we women workers, we’re miserable. All year long we’re yelled at and threatened: Hey you, quit napping, quit talking, your efficiency is low–Oh, you get so sick of it. The fact is, once you enter that place, a human being is thought of as less than a matchstick.

TSUGI: Is that so?

NEIGBOR’S WIFE: If I only had enough to eat, I wouldn’t go to such a place. But unfortunately, you know, human beings get hungry. And that, you see, puts us in a really tough spot.

TSUGI: True, nothing is as bitter as needing to eat.

A FISH-STORE APPRENTICE enters through the back door

APPRENTICE: Sorry to be late. (Puts the goods in the kitchen)

TSUGI: Did you bring bean paste?

APPRENTICE: Yes I did, and also matches and kindling. (While saying it, looks intently under the verandah)

TSUGI: What is it, why are you looking under the verandah? Did you drop something?

APPRENTICE: No, I’m looking for a dog.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Dog? No dog there. All that’s under the verandah are moles and mice.

APPRENTICE: Well, maybe one wandered in.

TSUGI: If you’re wasting time on a dog, I’ll tell your master.

APPRENTICE: Go ahead and tell him, I don’t care.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: This boy’s got a fresh mouth, doesn’t he.

APPRENTICE: Well, but it’s five hundred yen.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: What’s five hundred yen?

APPRENTICE: See the big house over there with the brick wall, the new money? A dog ran away from there. And they say they’ll give five hundred yen to whoever finds it.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: That’s ridiculous. Spending a pile of money on a single runaway dog! And here, there are so many people who don’t have enough to eat and don’t know what to do. I really wish they’d spend a little on people.

APPRENTICE: I hear that over there they feed the dog beef every day.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: And they probably feed their servants the cheapest rice.

TSUGI: What a waste to spend five hundred yen on finding a dog.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: In some places, there’s a lot of unneeded money, you know.

TSUGI: And yet in places where it’s needed, there’s none at all. Ah, if we’d had that kind of money, we could have kept them from dying.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: But you know, Tsugi, people with lots of money also die young.

TSUGI: Why is that?

APPRENTICE: Probably from overeating. Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha! (Laughing, vigorously shoulders his pail and heads for the door) Goodbye, thank you very much! (Leaves)

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Ah, sorry to have been talking so long. Well, I’ll go ahead of you, so when your father returns, come and join me.

TSUGI: I will, thank you.

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: Goodbye, then. (Steps outside, looks at the sky) Oh, what unpleasant weather.

TSUGI: Has it started raining again?

NEIGHBOR’S WIFE: It hasn’t, but the whole sky’s gotten cloudy. Cherry blossom weather is really unpredictable. Goodbye. (Leaves)

TSUGI: Goodbye. Take your time.

(After a while, POLICEMAN KOYAMA returns, entering through the front door)

TSUGI: Welcome back.

(TSUGI is about to take down his kimono hanging from a pillar)

KOYAMA: No, don’t bother, I’ll stay as I am. I’m hungry so I’ll finish eating first.

TSUGI: All right. That man came in just when you were about to eat. I thought you’d return hungry so I’ve left the tray out. (Moves the table closer to KOYAMA)

KOYAMA eats

TSUGI: Father, has the person who threw away the baby been arrested already?

KOYAMA: No, it hasn’t gotten that far yet. The body’s only just been found. But the culprit will soon turn up. Heaven never pardons such heartless criminals.

TSUGI: I think so too. If there’s a child’s life that someone would think nothing of taking, I wish that little Ken could’ve received it.

KOYAMA: Exactly. And, you know, it’s a plump and healthy-looking baby. It seems to have been strangled with something like a hand towel. Its throat was all purple.

TSUGI: Oh, how terrible. There are some vicious people, aren’t there.

KOYAMA: Those who have never had someone taken away from them don’t understand how precious life is. It really takes someone fiendish to kill a child in cold blood. But thinking about arresting that brazen criminal has given me my energy back. Give me some tea, would you.

TSUGI: Are you not eating any more?

KOYAMA: This pickled radish is very salty, isn’t it.

TSUGI: Yes, for some reason it seems heavily salted this time. Father, you must be tired. Won’t you go to the bathhouse?

KOYAMA: No, I’m all right. You’re the one who should go. I think you skipped bath for four days already.

TSUGI: True.

KOYAMA: This area is dangerous when it gets late, so you’d better go early.

TSUGI: I’ll go now then, and be back soon.

KOYAMA: Good idea. (Takes a notebook from his pocket, and starts busily writing in it)

TSUGI: To be on the safe side, I’ll lock up the back before I go.

KOYAMA (still writing): Ah, good, thank you.

TSUGI: (stepping down onto the earth floor, she opens the rear paper-screen door and is about to close the shutters) Ah! (A cry of alarm)

KOYAMA (startled): What is it?

TSUGI: Something’s out there. A black thing!

KOYAMA: A black thing. (Rushes into the kitchen)

TSUGI: It’s moving back and forth. I’m scared.

KOYAMA (looking outside): There’s nothing there.

TSUGI: Yes there is. Look, there it is.

KOYAMA: Hmm. Someone seems to be standing there. (To the PERSON OUTSIDE) Who is it? (Unable to make out the reply) What is it? Are you lost?

PERSON OUTSIDE: No, I have a small favor to ask.

KOYAMA: To ask me?

PERSON OUTSIDE: Yes.

KOYAMA: Then what are you doing standing around the back door?

PERSON OUTSIDE: I’m sorry. It’s just that it was hard to come in.

KOYAMA: If you have some business, come around the front. (To his daughter) I’ll close up the back; you hurry on to the bath.

TSUGI: All right.

KOYAMA: Be careful. Also, it looks like rain so take an umbrella.

TSUGI: I will.

As TSUGI opens the glass door to go out the front, DAY LABORER UJIHARA ASA is timidly standing outside.

ASA: I’m sorry to have startled you back there.

TSUGI: That’s all right. Please come in this way.

ASA: Thank you. (Nervously enters the police substation. Judging by the clothes, is returning from work)

TSUGI: I’ll be back soon. (Leaves)

KOYAMA: You want to talk to me.

ASA: Yes.

KOYAMA: Well, what is it?

ASA (holds out a box of cakes toward KOYAMA) It’s just a small thing, but…

KOYAMA: I cannot take that.

ASA: Please, maybe for your little boy.

KOYAMA: No, I don’t have him any more. My boy died recently.

ASA (disconcerted, timorously): Ah, I see, well…

KOYAMA: But that doesn’t concern you. So, what is the matter?

ASA: Sir, please take it. I have a big favor to ask you.

KOYAMA: I’ll listen to any request, but I cannot possibly accept that.

ASA: Is that so?

KOYAMA: You’re a woman, so you seem to know nothing about such things, but public officials are forbidden to accept presents from people. So you don’t need to worry about it. Whether or not I get a present, I will never discriminate. Don’t worry about it, tell me quickly what is the matter.

ASA (nervously): All right.

KOYAMA: Come, put away that box of sweets. (Pause) Now then, what is the matter?

ASA (after bowing her head awhile): Sir, when a child is born, does that have to be reported?

KOYAMA: Yes, of course, it has to be reported.

ASA: But if that baby soon died, then it doesn’t have to be reported, right?

KOYAMA: No, even if it died, one has to go through the formality of reporting it.

ASA: But it died so soon after birth, it’s the same as if it hadn’t been born.

KOYAMA: No, that won’t do.

ASA: So it does have to be reported after all?

KOYAMA: Did you have a baby?

ASA (after a moment of silence): Yes.

KOYAMA: Why didn’t you report it until now?

ASA: There was no one to help me.

KOYAMA: Couldn’t your husband have reported it?

ASA: I don’t have one.

KOYAMA: He died?

ASA: Yes.

KOYAMA: In that case, I’ll report it for you. It’s late, but that can’t be helped.

ASA: Must it really be reported?

KOYAMA: Yes, it must. Not making a notification is a criminal offence.

ASA (her head bowed): I don’t know what to do. Sir… (Nervously, pushing the box of sweets again toward KOYAMA) Please. Could you keep it to yourself, sir? Please.

KOYAMA: That’s impossible.

ASA: Sir, please make it so it isn’t a crime. Please keep it a secret. Sir… Have mercy.

KOYAMA (suddenly grabs her arm): Hey. You killed your child, didn’t you!

ASA: No, no, I, no, no…

KOYAMA: Don’t lie. Then why are you so scared to report it?

ASA: No, I d-don’t remember killing…

KOYAMA: Then why did the baby die?

ASA: It died. It just died.

KOYAMA: How could it just die?

ASA: It was s-s-sick…

KOYAMA: It was sick. When did it die?

ASA: D-d-day before yesterday.

KOYAMA: Day before yesterday. (Solemnly) And what did you do with the body?

Without a word, the woman suddenly shakes off the policeman’s hand and tries to flee.

KOYAMA: You brazen wretch.

The policeman springs after her, wrestles her to the floor, and starts tying her with a rope.

ASA: Sir, what are you doing! (She resists)

KOYAMA: Resisting won’t do you any good.

ASA: I don’t want to be tied up! I don’t want to be tied! (With a heartrending scream, she resists)

KOYAMA: Quit yelling, and stay still.

ASA (limply) I don’t want to be tied up… (Throws herself down in tears)

KOYAMA (finishes tying ASA): Impudent wretch. Brings a box of sweets and tries to sweet-talk me. Hey, lift up your face.

ASA (remains prostrate)

KOYAMA: I’m telling you to lift up your face. (Grabs the back of ASA’s collar, draws her face upward)

ASA (Wordlessly raises her face. Her eyes are flashing with a fierce light)

KOYAMA: You, why did you kill the baby?

ASA (remains silent)

KOYAMA: Why did you do such a heartless thing? Tell me.

ASA (remains silent)

KOYAMA: I’m telling you to tell me why! (He shakes the woman, then shoves her forward)

ASA (Pitches forward, devoid of strength. But doesn’t reply)

KOYAMA: You’re stubborn, aren’t you! Why aren’t you talking? Answer me!

ASA (remains silent)

KOYAMA: You were fooling around with someone, weren’t you! Telling me just a while ago you had no husband. So you gave birth to a fatherless child.

ASA (wordlessly shakes her head)

KOYAMA: Don’t lie. Must be you didn’t know what to do with the child, so you did such an outrageous thing. Who’s your lover? Tell me your lover’s name.

ASA (says something inaudible)

KOYAMA: What? Not a fatherless child? It’s your husband’s child? But didn’t you tell me your husband died?

ASA (in a barely audible voice) He died, but just three months ago.

KOYAMA: He died three months ago. Then you’re sure it’s your husband’s child?

ASA (her voice choked with tears): Yes.

KOYAMA: Well, if that’s so, you’re worse than a demon. Even a fiend wouldn’t kill her own child. Don’t you love your child?

ASA (is wordlessly crying)

KOYAMA: I just lost my son a while ago. I lost him to illness, but I just can’t resign myself to it. Yet you, how can you do such a heartless thing.

ASA: Children are so precious. Sir, I understand how you feel.

KOYAMA: Don’t you dare talk like decent people! You don’t understand what it means to love a child! With a monstrous heart like yours!

ASA: Sir, no matter how poor one is, there’s no difference in a parent’s love for a child.

KOYAMA: Then why did you kill it? You won’t get my sympathy with some sentimental sob story. Why did you kill it? Tell me the reason. Why?

ASA (crying): The child, I killed the child because I felt sorry for it.

KOYAMA: What? You killed the child because you felt sorry for it. Look, don’t say stupid things. When you love a child, it stands to reason that you bring it up with care. What the hell kind of logic is it to love a child and kill it?

ASA: That, that’s right, sir.

KOYAMA: Well then, why did you do it?

ASA: Right. (Wiping her tears) It’s the parents’ duty to cherish their children. That’s the parents’ way everywhere in the world. But we can’t do it like the rest of the world.

KOYAMA: Why can’t you?

ASA: Why, sir?

KOYAMA: I want you to tell me everything about it.

ASA: Telling you about it wouldn’t do any good. It isn’t something one can talk about.

KOYAMA: All right. Then I will question you. You said your husband died three months ago, but how did he die?

ASA: He died from sickness.

KOYAMA: He died from what sickness?

ASA: From lung sickness. He vomited a whole lot of blood, and died.

KOYAMA: Hmm, and so you became a construction worker after that?

ASA: No, about a year and a half ago.

KOYAMA: So your husband became sick around that time?

ASA: He was sick before then, but that’s when it got so bad he couldn’t work any more.

KOYAMA: So you started to work in place of your husband.

ASA: Yes.

KOYAMA: Well, it must have been very hard for your family.

ASA: So many times there was no food to eat for three or four days. That by itself we could’ve put up with, but during that time two of our children died.

KOYAMA: From the same sickness?

ASA: Yes. Throwing up so much blood… When it stuck in their throats they couldn’t breathe, and so many times I put my fingers down their throats and pulled out lumps of blood.

KOYAMA: So within a year and a half, you lost your husband and two children.

ASA: Yes.

KOYAMA: Wasn’t that all the more reason to give this baby a healthy upbringing?

ASA: That’s right, sir.

KOYAMA: Well then why did you kill it?

ASA (bursts out into loud sobbing)

KOYAMA: Hey, what is it?

ASA (throws herself down in tears): Sir, you can never understand.

KOYAMA: Why not?

ASA: For our children, it’s more merciful to make them die than to make them live. It’s kinder to have them die knowing nothing than to show them this sad, painful world.

KOYAMA: Are you insane?!

ASA: No, I’m not. Don’t you see, sir? It’s cruel to leave someone sick to lie alone when you can’t take any care of them at all. It’s downright cruel.

KOYAMA: But to kill a healthy baby is a greater crime, isn’t it?

ASA: That’s true, but that child was going to end up the same way. The last one born before the baby is lying in bed at home right now.

KOYAMA: But you didn’t have to kill it.

ASA: I know. I don’t know how many times I thought about it. I thought about it and stopped, thought about it and stopped, and so it went on till just the other day. While I was pregnant, I actually thought of having an abortion but I didn’t think my body could stand it … No, it isn’t at all that I wanted to live. It’d be such a relief for me to die, but there’s just no way I can die. If I died, my sick child and my old father would starve to death.

KOYAMA: So in addition to the child, you have an old man at home.

ASA: That’s right, sir.

KOYAMA: Is the old man too weak to work any more?

ASA: That’s right, and that’s why I have to go out and work. So I worked. I worked as hard as I could till the day before the child was born. I shouldn’t say such things to you, sir, but when a baby is born, no matter how poor you are, you love it. When it smiles sweetly looking at my face even though I can’t give it enough milk, I love it so much I never want to let it go even a moment.

KOYAMA: That’s true.

ASA: But if I spent time taking care of the child as other people do, we’d have nothing to live on. I wouldn’t mind if it were me alone, but the old man and the child that’s sick couldn’t get through it either.

KOYAMA: Hmm, so you’re saying you killed the baby because it got in the way of working?

ASA: It wasn’t that it got in the way, but having it kept me from earning a living.

KOYAMA: Hmm, I see. (Sighs)

ASA: Sir, I’m truly very sorry.

KOYAMA: But you didn’t think it through. You must have known that killing it would be a crime.

ASA: Yes.

KOYAMA: If so, then why did you do such a thing?

ASA: There was nothing else I could do.

KOYAMA: You could have given the child to someone.

ASA: You can’t give it for nothing, sir. Who will take a baby with no money? There’s no limit to poor people’s misery. Sir, I didn’t mean to do anything bad, please forgive me.

KOYAMA: Hearing the circumstances, I’m sorry for you but my duty makes it impossible for me to know about this and keep it secret.

ASA: Please, sir, I beg of you.

KOYAMA: It’s out of my hands. If the body hadn’t turned up an exception might have been made, but now that the baby’s body has been exhumed nothing can be done any more.

ASA: Eh, the baby?!

KOYAMA: That’s right. It seems you buried the baby in the bamboo grove.

ASA: A-ah, it’s all over. (Seeming to have lost hope, falls prostrate and cries)

KOYAMA: So at this point, you’d better tell the truth without concealing anything. That is the only way to lighten the crime. What is your name? (Takes out his notebook, readies to write)

ASA (crying, does not answer)

KOYAMA: Come, not answering won’t do you any good. What’s your name?

ASA (crying): It’s Oasa.

KOYAMA (writing in the notebook, calmly continues the interrogation): Your husband?

ASA: Ujihara Sadajiro.

KOYAMA: He died three months ago, correct? His occupation?

ASA: Like me, construction worker.

KOYAMA: Address. Where do you live?

ASA: Shimo-Meguro.

KOYAMA: Fuka-Ebara District, Meguro Village, Shimo-Meguro. What number?

ASA: Two-thousand three-hundred fifty-seven.

KOYAMA: Two-thousand three-hundred fifty-seven. This is your own place, right?

ASA: Right.

KOYAMA: And when was the baby born?

ASA: On the tenth, the month before last.

KOYAMA: February tenth. A boy?

ASA: Yes.

KOYAMA: And you killed him when?

ASA (painfully): The night before last.

KOYAMA: How did you kill him?

ASA: I came back from work, like tonight. I was carrying the baby on my back and when I got near the Gyonin Slope, the baby was crying like he was on fire. I wanted to give him milk but I didn’t have any, so I didn’t know what to do.

KOYAMA: Why didn’t you have milk?

ASA: Maybe because I didn’t have enough food, but five or six days earlier my milk had suddenly stopped coming.

KOYAMA: And so?

ASA: And so because I couldn’t do anything else, I put my breast in his mouth, though no milk was coming.

KOYAMA: And then?

ASA: And then he cried for a while, but at some point he let go of my breast, and fell asleep.

KOYAMA: Is that when you did it?

ASA (her head droops forward mutely and her shoulders sag)

KOYAMA: And how did you kill him, with a hand towel?

ASA (silent)

Suddenly, stricken with cerebral anemia, she falls backwards. As KOYAMA, startled, tries to attend to her, the glass door in front opens and TSUGI enters.

KOYAMA: Ah, you’ve come at just the right time. Give me a hand for a moment, would you.

TSUGI: Yes.

KOYAMA: Listen, let’s carry her up to the living room. (With TSUGI’s help, lays ASA down in the living room) We don’t need a pillow. Let’s keep her head low and elevate her legs.

Props up ASA’s legs with a stool. TSUGI removes her straw sandals. KOYAMA fills a glass with water and splashes it over the woman’s face and chest.

TSUGI: Father, you must untie the rope. It’s cruel.

KOYAMA: That’s right. I must untie the rope. (Hurriedly unties it)

TSUGI (massaging the woman’s feet): Poor woman.

KOYAMA: Were you listening?

TSUGI: Yes, it was hard to walk into the house. I was standing outside.

KOYAMA: I see. The world is full of pitiable people, isn’t it.

TSUGI: Ah, she seems to be coming to.

KOYAMA: Leave her alone for now. It’s cerebral anemia, from doing strenuous work soon after delivery, from worrying and all the rest.

TSUGI: Father, will you take this woman in after all?

KOYAMA: Yes. I have no other choice. But in fact I’m guilty of the same crime myself.

TSUGI: That isn’t true, father!

KOYAMA: No, this woman killed her child, and I too killed my child and my wife. The only difference is whether or not we did it directly with our own hands.

ASA (suddenly coming to): Yes. I’m to blame. I killed him. I have no excuse.

KOYAMA: Ah, you’ve come around.

ASA: Yes. I committed a crime. I committed a terrible crime. But, sir, from now on I’m sure to be a different person. Please, please forgive me. (Sees TSUGI) Ah, the young lady. I’m sorry for what happened a while ago. How I must’ve startled you. I’m very sorry. I was feeling guilty. And so I couldn’t help being nervous. I guess people really can’t get away with doing bad things. I tried to act as though nothing had happened, but I can’t do it after all. The baby’s face sticks in my mind night and day, and it won’t leave. When I work leveling the ground with a cable, I feel like I’m pushing against my buried baby’s head, and I can’t keep calm. Even so, if I’m arrested now it would be terrible and so I came to you, sir, to ask you a favor. (Suddenly looks at her hands, notices they are not tied. To KOYAMA) Sir, you untied the rope? Thank you so much. Thank you so much. (Clearly delighted, she bows to KOYAMA)

KOYAMA (silent)

ASA (turns to TSUGI): Young lady. I’m so grateful. I’m so grateful. (Thanks her from the heart. TSUGI, at a loss, remains silent, her head bowed) I get only one yen and fifty sen per day, but just so long as I work I can make it through the day somehow. Sir, I’m so grateful. That’s everything I’d hoped for. Thank you very much.

TSUGI: Father, you hear what she’s saying, can’t you do something?

KOYAMA (his mouth stays firmly closed, his head bowed)

ASA: Ah. Then, after all, I… A-ah… (She collapses in tears)

(A prolonged heavy silence)

ASA (shortly, not rising, in a tearful voice) Sir. Please tie me.

TSUGI: Didn’t you say you don’t want to be tied?

ASA: I give up. There’s nothing I can do but give up.

TSUGI: But even so.

ASA: A person like me is tied all her life. It makes no difference to me.

TSUGI: But what will your sick child do, and the old man?

ASA: When I think of that… (She breaks into sobs)

KOYAMA: Look, go stop by your house and see your child for a few minutes. I can look the other way that long.

ASA (crying) I will not see him. If I see him, I will miss him even more.

KOYAMA: That’s true too.

ASA: Sir.

KOYAMA: What is it?

ASA: I have a favor to ask you.

KOYAMA: What kind?

ASA: Here’s what’s left of my daily wage; can you take it to my house?

KOYAMA: That’s easy. I’ll take it for you.

ASA: Thank you very much. Here you are.

(Hands her wallet to the policeman)

KOYAMA: Right. I’ll take care of it for you. I’ll be sure to take it.

ASA: Thank you very much.

Pause

ASA: Sir.

KOYAMA: Hmm?

ASA: About how many years will I spend in prison?

KOYAMA: Well, one can’t know for sure, but you may get two or three years. But, depending on the circumstances, you may be let off with a suspended sentence. You’d best honestly tell the whole truth.

ASA: Thank you very much. (Pause) Sir…

KOYAMA: Yes?

ASA: May I ask one more question?

KOYAMA: Ask anything.

ASA: You said that the baby has been dug up; where is he now?

KOYAMA: They transferred him to the village office.

ASA: Could I see him one more time?

KOYAMA: No, you’d better not do that.

ASA: Do you think so?

KOYAMA: If you see him, it will stay in your mind, and it’ll be worse for you.

ASA: That’s true, isn’t it … And yet, when I buried him he kept looking at me from the hole with such reproachful eyes. A-ah, when I think of it!

Pause

ASA: Sir, the rope.

KOYAMA: No, it’s all right as it is.

ASA (inwardly thanks KOYAMA deeply)

KOYAMA: Well, I’m off to the headquarters for a short while.

TSUGI: Yes.

KOYAMA leaves, escorting ASA. TSUGI follows them steadily with her eyes.

Suddenly, with a lonely sound, it starts to rain.

–Curtain–

Zeljko Cipris teaches Asian Studies and Japanese at the University of the Pacific in California and is a Japan Focus contributing editor. He is translator of Inoue Hisashi’s play Living with Father (The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Drama, ed. J. Thomas Rimer et al., 2014); Ishikawa Tatsuzo’s novel Soldiers Alive; and A Flock of Swirling Crows and Other Proletarian Writings, a collection of works by Kuroshima Denji. His translation of The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle by Kobayashi Takiji was listed among the best translations of 2013 by World Literature Today. This translation is dedicated to Ljubomir Ryu and Shane Satori, and to Masha.

Recommended citation: Yamamoto Yuzo, “Infanticide”, translated and introduced by Zeljko Cipris, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 34, No. 3, August 25, 2014.