“It is in maternity that woman fulfills her physiological destiny; it is her natural ‘calling,’ since her whole organic structure is adapted for the perpetuation of the species. But […] human society is never abandoned wholly to nature.”

-Simone de Beauvoir1

On July 1, 2013, TV Asahi’s evening news show, “Hodo Station,” aired an interview with two-time world champion figure skater Ando Miki that broke the news that she had given birth to a baby girl (out of wedlock) in April.

The media buzz over Ando’s revelation was captivating – newspapers, variety shows, and weekly magazines speculated on who the father was, since Ando chose not to publicly disclose that information. An immediate and intense focus on her professional career as a figure skater raised more questions about her future: Was she going to retire from skating? Was she going to train for the 2014 Sochi Olympics, the trials for which were set to take place in just a few months? Gossip over the circumstances of her baby’s conception quickly faded behind news stories about Ando being out on the ice, training devotedly for the Olympics and taking part in international competitions, just months after her baby was born.2

Although Ando would not go on to make the 2014 Olympic team, many so-called mama-san senshu, or “mother-athletes” in Japan have had phenomenal post-child(ren) careers, and have garnered similar, largely positive, press in the process. Such media attention can both reflect and influence larger trends in contemporary Japanese society, and this paper seeks to delve into the social issues surrounding sports and motherhood in modern and contemporary Japan. In doing so, I highlight one channel through which the Japanese government and the media have been sending subtle yet powerful messages to the public about the “right” role for mothers in contemporary Japan.

|

Ando Miki with her daughter, Himawari. The headline from her July 1, 2013 TV Asahi interview reads “Exclusive Interview: Ando Miki acknowledges giving birth – aiming towards Sochi.” |

In order to understand the role and status of women in a socio-historical context, the dynamic relationship of women with their bodies must be taken into consideration. As suggested by the epigraph by Simone de Beauvoir, women’s position in patriarchal societies has long been rationalized biologically. That is to say, the fact that women can bear and nurture children – that their bodies have organs that are adapted to the functions of motherhood – has served as a major obstacle to the full participation of women in many arenas of society. The notion of female biological inferiority is perhaps nowhere in sharper focus than in the world of sports. I thus look critically at the relationship between sports and the female body, specifically at how motherhood has been used to either limit or promote the role of women in sports. In contemporary Japan, where demographic crises and economic woes are at the forefront of the national discourse, it is particularly important to have a nuanced understanding of women’s role in society with respect to the family and the workplace. To this end, I will first examine how motherhood has historically fit into the discourse on sports (globally). I will then look at how motherhood has played into discourse on Japanese women’s role in society. Finally, I will consider the implications for Japanese society of elite “mama-san senshu,” a category of sportswomen whose presence has grown in the Japanese media in recent years.

Traditional Western and Japanese Conceptions of Sports and the Female Body

Arguments both for and against women’s participation in modern sports around the world have been based on ideas of “natural” female roles as supportive wives and nurturing mothers. That is to say, the connection between sports and motherhood is not a tenuous one – the reproductive capacity of the female body has long been the key limiting factor in women’s involvement in sports.3 There is a fine line between fit motherhood and “masculine” athleticism that has been negotiated and renegotiated when considering women’s place in the sporting world, and this line has shifted significantly depending on time and place. Yet across the globe, from early modern times to the present, fertility and the potential risk that physical activity might pose to women’s ability to reproduce have been front and center in almost all narratives and theories regarding women in sports. I will briefly touch on some influential theories on sports and the reproductive body, particularly as they relate to their influence on women’s sports in modern Japan.

Since the concept of what a “fit mother” might look like has shifted over time, so too has the relationship between sports and fertility. I will only be looking at modern sports, whose rise coincided with the maturation of industrial capitalism in 19th-century Europe and shortly thereafter in Japan.4 As the division between labor and leisure became increasingly distinct, people in industrializing lands began to fill their free time with both exercise regimens and organized sports. Dramatic transformations in the global economy and class relations contributed to new forms of athletic culture that were aimed at cultivating self-discipline and a strictly regulated body among the middle-class. Two distinctive traditions developed during this time: “manly sport” for boys, and “female exercise” for girls.5

While schoolboys in the late-19th century were learning the ethos of “good sportsmanship” and leadership through sports (both in the West and in Japan), girls and women were not encouraged to take part in physical exercise or organized sports. Sports were seen as helping to breed self-control and to strengthen men’s moral fiber though muscular development. Since women had no leadership roles to play in the public sphere, sports were not seen as serving any function in their lives. Moreover, an influential Victorian aesthetic persisted in many industrializing societies – upper-class women preferred to be seen as pale and weak, and therefore unfit for physical exertion (especially as compared to their suntanned, robust working class counterparts). This aesthetic was pronounced in Meiji Japan (mid-19th to early-20th century), as can be seen in numerous woodblock prints and photographs of the time showing European styles in vogue among upper-class Japanese women.

|

Woodblock print of the imperial family, depicting the Meiji empress in Victorian garb. “A Mirror of Japanese Nobility,” by Toyohara Chikanobu, 1887 (from John Dower’s essay, “Throwing Off Asia I: Woodblock Prints of Domestic ‘Westernization,’ (1868-1912)” on the MIT Visualizing Cultures website) |

Aesthetic ideals aside, the biggest concerns among scientists and social commentators on women’s sports were the potential damages that vigorous physical activity might pose to the reproductive system. For example, in the mid-19th century, British doctor Henry Maudsley postulated that bodies were born with a fixed amount of energy, and that if women wasted energy on muscular development or intellectual pursuits, then this would deplete the reserves necessary for pregnancy and childbirth.6 Sports were long seen as both spoiling a girl’s looks and limiting her options for marriage partners, even causing infertility for those athletic girls who did manage to find a partner. By the early 1900s, there was a growing literature on the relationship between exercise, menstruation, and reproduction. Strong assertions were made on both sides, with some declaring that all sorts of female dysfunction (including sterility) would result from exercise, and others countering that physical activity, especially during menstruation, was healthy and therapeutic for young women. With such contradictory scientific theories, educators in the expanding fields of female physical education and sports tended towards policies of prudence, advising young women to avoid unnecessary strenuous activity.7

While we may look back on these archaic theories and laugh, myths about women athletes and reproduction persisted through much of the 20th century. For example, until recently, it was thought that a woman’s reproductive organs were more prone to damage through sports, or that childbirth adversely affects athletic performance, even though studies (beginning in the 1960s) show otherwise.8 Complications of pregnancy appear to be fewer, and the duration of labor is on average shorter among athletes.9 A number of notable mother-athletes have performed significantly better after childbirth than before.10 Moreover, although males are as essential to females in the process of reproduction, the potential risks to men’s reproductive organs (which are arguably at greater risk than women’s in many sports) have rarely, if ever, been discussed in the history of men’s involvement in sports. This is just one of many examples that illustrate the arbitrary inequality of the sexes (in sports as in society). As sociologist Judith Lorber has pointed out, “The overall status of women and men athletes is an economic, political, and ideological issue that has less to do with individual physiological capabilities than with their cultural and social meaning and who defines and profits from them.”11

Against the obsession over protecting the reproductive capacity of women, the calisthenics and games that were introduced for girls in the 19th century were low-impact and ultimately aimed to benefit the health of young women. Women who were in “perfect health and high spirits” came to be seen as more attractive by the end of the 19th century, and the Victorian ideal of the weak and idle woman had all but faded away.12 That said, the early 20th-century instrumentalization of sports for the sake of women’s health has been criticized by some feminist scholars, who contend that women were being encouraged by male medical professionals to “hone their bodies to a machine-like efficiency through modest and sociable sport and exercise in order that they might better secure the biological future of the race.”13 This language derives from the eugenics movements that swept the globe at the turn of the 20th century, 14 which emphasized high birth rates and improving motherhood for the further advancement of a particular group of people.15 While today social Darwinism and other theories that reduce women merely to their reproductive organs are widely considered to be long-outdated modes of thought, some recent rhetoric still has echoes of this mindset. In 2007, Japan’s health minister Yanagisawa Hakuo addressed Japan’s plummeting birthrate by publicly (and infamously) stating, “because the number of birth-giving machines (umu kikai) is fixed, all we can ask for is them to do their best per head.”16 This statement resonates with tropes of women as biological reproducers of the Japanese people that have persisted since the Meiji era. Below I will briefly outline the discourse of motherhood in modern Japanese society.

Motherhood in Modern Japanese Society

Education (including physical education) for girls in Meiji-era Japan was largely motivated by the ideology of ryōsai kenbo (良妻賢母), or “good wives and wise mothers.” Meiji Minister of Education Mori Arinori outlined the government’s stance towards women, stating in 1887, “If I summarize the point regarding the chief aim of female education, it is that the person will become a good wife (ryōsai) and a wise mother (kenbo); it is to nurture a disposition and train talents adequate for the task of rearing children and of managing a household.”17 Also during the Meiji era, new labor laws were passed that limited the hours that women could work in factories out of concern that female factory workers were not producing healthy offspring.18 During Japan’s imperial era, the idea that women’s main role was to reproduce Japanese subjects was strengthened, as slogans like umeyo fuyaseyo (生めよ増やせよ), meaning “bear children and multiply” became popular in the 1930s and 40s. An image of women as those who reproduce and raise the soldiers fighting for the Japanese empire took root.

Indeed, fervent nationalism contributed to the spread of maternalist ideas in Japan in the early-20th century.19 Men who were interested in strengthening the Japanese nation imported new ideas about womanhood from the West, in large part to resist Western imperialism. The well-known ryōsai kenbo ideal was indeed a blend of old Confucian ideas of patriarchy (the “good wife” part) with more progressive, Western notions of women as competent contributors to the nation (the “wise mother” part). The degree to which women were expected to contribute to productive labor (in addition to reproductive labor) varied over time, with more women entering the workforce as more young men served in the military. While women had been performing jobs that required significant physical labor (most notably farming) well before the 20th century, demands for female labor in all sectors were heightened amidst male labor shortages as Japan’s military machine grew ever larger in the 1920s and 30s. One of these sectors was the female-dominated textile industry, the history of which is deeply entwined with this history of Japanese women’s sports, particularly corporate-sponsored women’s volleyball.20

|

|

|

David Earhart’s Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2008) highlights a number of striking images of Japanese women during WWII in Chapter 5, “Warrior Wives.” The two images below, both 1944 covers of the photodigest Photographic Weekly Report (the most authoritative of Japan’s wartime news journals, according to Earhart), reflect the importance of women’s role in both reproduction and production during the War. The image on the left shows a woman nursing her child and sewing soldiers’ gloves simultaneously (striking a perfect balance between childrearing and work), and the image on the right shows female mechanics building an airplane, a traditionally male job. (Earhart, p. 158, 172) |

As needs for both manual labor and reproductive labor grew, state protections for mothers were introduced beginning in the 1930s, with acts like the 1938 Mother and Child Protection Act (boshi hogo hō) providing financial assistance for mothers whose husbands had died, were injured, or had abandoned their families.21 Although the division of labor fell quickly back into the male-breadwinner, female-homemaker paradigm following Japan’s loss in the War, the Japanese government has remained (at times myopically) focused on figuring out ways to enable women to contribute to the workforce and continue to bear and raise more children. Keywords such as “parental leave,” “childcare,” and “family-friendly workplaces” popped up with great regularity in the late-20th and early-21st century Japanese media, particularly as the fertility rate dropped below 1.5 children per women.22

Of course, changing legislation and resource allocation is one thing, but changing social attitudes towards motherhood is another. In spite of a number of recent government initiatives aimed at improving gender equity in the workplace, one could easily argue that motherhood is still seen as a woman’s highest calling in Japan.23 In this respect, the Meiji-era ryōsai kenbo ideal is still very much alive in contemporary Japan even though the options available to Japanese women and the society in which they live have changed tremendously in the past century and a half. That said, the mother-athletes to whom I will now turn shed light on surreptitious change that is taking place in contemporary Japan with respect to attitudes towards motherhood, employment, and sports. These highly visible women are both reflective of institutional changes occurring in the face of a demographic crisis, as well as potential catalysts for further change.

Mama-san senshu: Exceptions to the rule or a new normal?

As discussed earlier, reproduction and the potential risks that physical activity may pose to it have played a major role in shaping the way women participate in sports. In Japan this has certainly been the case since the late-19th century, when Western sports took root and began to grow in popularity among girls and women. While there were changes to the education system that involved more physical education and eventually competitive sports (in the 1920s) for girls, there was also an understanding that childhood was the appropriate time for such activity. Much like women in the workforce, there was an expectation that athletes would retire upon marriage (one of the points at which females move from girlhood to adulthood). In Japan in the 1920s and 30s, female athletes who competed into their 20s and eschewed marriage and motherhood were publicly rumored to be lesbians or transgender.24 If it wasn’t speculation over one’s sexual orientation, it was media scrutiny over when a female athlete was going to retire from her sport to begin her life as a housewife and mother.25

|

After 22-year old swimmer Maehata Hideko’s gold medal win in the 200m breaststroke event at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin (the first Olympic gold medal won by a Japanese woman), the Asahi Shinbun ran this article with the headline “Banzai! Queen of the Water” (Banzai! Mizu no joō sama) A large subheading in the article reads “Next comes marriage” (Tsugi ha kekkon da), which was likely included because Maehata was publicly criticized for her decision to compete in a second Olympic Games at the marriageable age of 22 (she had won a silver medal in the 1932 Games in Los Angeles, but was determined to go for the gold. (Asahi Shinbun, Aug. 12, 1936) |

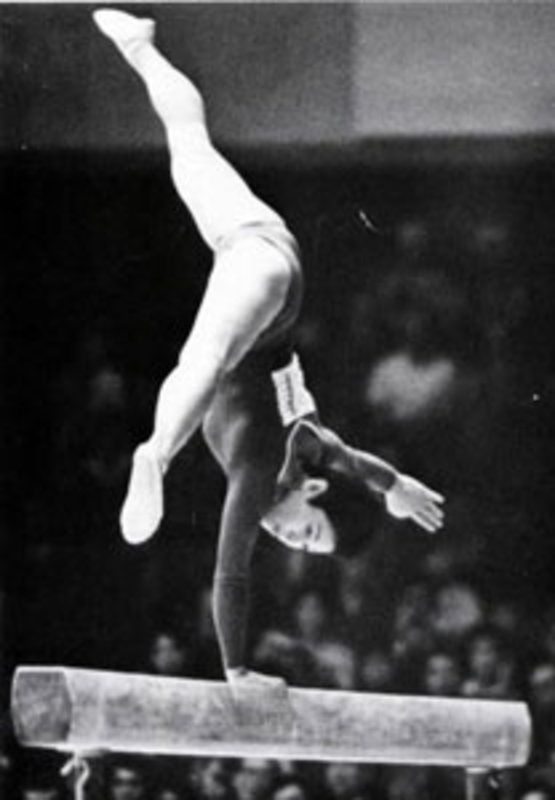

A number of factors contributed to changes in popular attitudes toward female athletes in subsequent decades. Sportswomen from other countries began to unambiguously disprove theories that competitive sports led to infertility, and growing numbers of married women and mothers from Western countries shone at heavily publicized events like the Olympic Games.26 By the 1960s, successful married athletes and mother-athletes were appearing with increasing frequency in Japan. Among Japanese athletes in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics were a few mothers, and this event had an impact on a great number of Japanese people.27 Household incomes had begun to rise after the war, which led to many families being able to watch the event on their personal television sets – this made the media impact of these particular Games especially profound. Two of the most publicized were gymnasts Ikeda Keiko (mother to two boys, ages 3 and 1),

|

3-time Olympic gymnast, Ikeda Keiko. The first photo is with her second son, Takahiko (born in 1963). Ikeda took part in the 1956, 1960, and 1964 Summer Games, and won a bronze medal in 1964. The second photo is from the 1964 Olympics (from the Chugoku Shinbun, March 8, 2011, “体操五輪メダリスト池田敬子さん” |

|

and Ono Kiyoko (mother to a 3-year old girl and 1-year old boy. Ono was also married to her coach, another famous gymnast. This combination of two Olympians with two children garnered a lot of attention). Ikeda and Ono were both part of the bronze-winning women’s gymnastics team in Tokyo.28

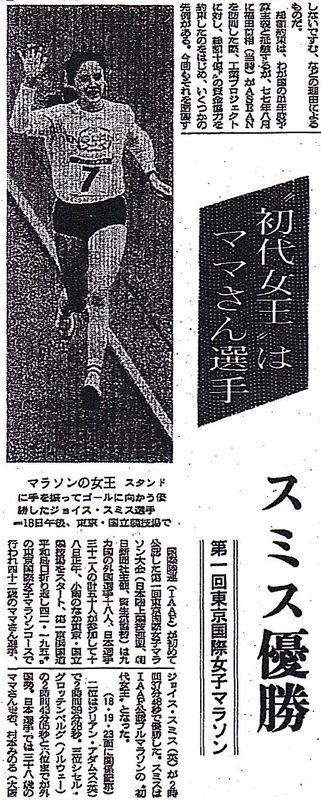

The idea that marriage and childbirth need not end an athletic career continued to grow from the 1970s onward. In 1979, the first-ever women’s marathon officially sanctioned by the International Association of Athletic Federations (IAAF) took place in Tokyo. The marathon, which was a distance long considered inappropriate and dangerous for women, was won by British runner and mother Joyce Smith.

A number of Japanese women were dubbed “housewife” athletes in the 1980s and 90s. For example, marathon runner Hiroyama Harumi (who competed in the Atlanta, Sydney, and Athens Olympics) was known as “Mrs. Runner” (misesu rannā) since she was married to her coach.29 Judo wrestler Narasaki Noriko was also a bronze-medal winning (Sydney Games) “housewife athlete” (shufu senshu). The most publicized female athlete in Japan in recent decades has been judo wrestler Tani Ryōko (née Tamura), who has been in the media spotlight since she won the International Women’s Judo Championships as a 15-year old in 1990.30 She married professional baseball player Tani Yoshitomo in 2003, and immediately the media commented that she would continue to win, even as a wife (the slogan was “Tani demo kin,” meaning “gold even as a Tani,” since she had changed her surname upon marriage). She did indeed continue her winning streak, going on to win a gold medal at the 2004 Olympics. After giving birth to her first son in 2005, her media catchphrase changed to “mama demo kin,” or “gold even as a mother,” and again she delivered on the media hype, bringing home a gold medal from the World Championships in 2007. Now a mother of two young boys, Tani has retired from judo but remains very much in the public eye as a member of the Japanese parliament.31

Today, mother-athletes appear frequently in the Japanese media, highlighted as both celebrated sportswomen and as working mothers. Some who have been in the media spotlight in the past five years include: figure skater Ando Miki, high-jumper Fukumoto Miyuki,

curlers Funayama Yumie and Ogasawara Ayumi (Japan’s flag bearer at the 2014 Sochi Olympics), freestyle skier Mitsuboshi Manami, soccer player Miyamoto Tomomi, beach volleyball player Saiki Mika, snowboarder Imai Mero, clay-pigeon shooter Nakayama Yukie (a single mother), volleyball player Ōtomo Ai (also a single mother), speed-skater Okazaki Tomomi, and distance runner Akaba Yukiko.32 The final three (Ōtomo, Okazaki, and Akaba) have each been awarded a “Best Mother Award” (in 2011, 2012, and 2013 respectively) by the non-profit organization Japan Mother’s Society (Nihon mazāzu kyōkai), which was based on public votes for mothers considered to be inspirational. The award was initiated in 2008 to show support for both mothers and for companies and organizations supportive of childbirth and childrearing.33

|

Olympic gymnast Ono Kiyoko holding her eldest daughter and standing next to her husband/coach. Asahi Shinbun (Sept. 17, 2013), 「2020東京五輪ズポーツ半世紀:4」女性アスリート母の挑戦、支援に本腰」 |

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these mother-athletes tend to have their personal lives highlighted in a way that their male counterparts do not – a recent in-depth analysis of media attention received by male and female parent-athletes in the Japanese media found that family life was rarely discussed in articles about the father-athletes (less than 8% of the articles), but often brought up (about 30% of the time) in the articles about mother-athletes.34 Indeed, the media has played an important role in disseminating images and stories of mother-athletes in contemporary Japan, which has contributed to normalizing the phenomenon – not only of women returning to their jobs following childbirth, but also of husbands showing support towards their working wives. That said, it also exposes still-present stereotypes and assumptions about mothers, namely that women remain deeply connected to the domestic realm. The fact that both progressive and more traditional constructions of motherhood are contemporaneously brought to light by these women suggests that Japan is in a period of transition, and that attitudes towards motherhood are changing, albeit somewhat haltingly.

The media focus on mama-san senshu as both athletes and mothers speaks to an important socio-cultural shift occurring in Japan today. With a rapidly aging population and declining birthrate, the Japanese public is well aware that a demographic crisis threatens Japan’s already-faltering economy and already-strained safety net. Mama-san senshu fit neatly into a larger narrative about the changing role of Japanese women. Images of strong and healthy women returning to the “workplace” after marriage and childbirth send a powerful message to a society where women are opting to marry later and have fewer children (around 1.4 children per women).35 After all, Tani Ryoko’s catchphrases, “Tani demo kin” and ”mama demo kin” are essentially just different ways of saying, “keep working after marriage” and “keep working after childbirth.” If Japan is to economically rebound, the government is acutely aware that women need to remain part of the workforce after marriage and childbirth – efforts are being made in both explicit and more subtle ways to encourage the growth of the labor pool of working mothers.36

|

The Asahi Shinbun (Nov. 19, 1979) reported on the first women’s marathon officially sanctioned by the IAAF, held in Tokyo on November 18, 1979. The headline reads, “First queen [of the marathon], is a mama-san senshu.” The 42-year old British winner, Joyce Smith, won with a time of 2 hours and 37 minutes. |

The growing prominence of mother-athletes is, in my view, one of the subtle ways that the government and the media have worked in tandem to promote women’s re-entering the workforce after having children. While these sporting mothers have faced an uphill battle when it comes to continuing their athletic careers after childbirth, it appears that there are signs of institutional change that are being made to meet the needs of these athletes. For example, in 2012 Kono Ichiro, the chairman of the Ajinomoto National Training Center in Tokyo (where Japanese athletes competing at the Olympics and world championships go to live and train) announced that the Center would be opening a daycare facility to be utilized by the children of elite athletes in training.37 This facility opened its doors in June of 2013, and the major media outlets reported on its opening with headlines such as, “Support for mama-san athletes: No-fee National Training Center daycare facility.”38

|

Two-time Olympic gold-winning judo wrestler and mother of two, Tani Ryoko, after winning her seat in the Upper House election for Japanese parliament in 2010 (from “DPJ Winded, Judo Champ Wins,” The Wall Street Journal, July 11, 2010) |

I visited this facility shortly after it opened, and learned that although a few children of athletes-in-training were already utilizing the center, there were still discussions over who exactly was eligible to make use of it. For example, administrators at the Japan Institute of Sports Sciences (JISS, a facility on the grounds of the National Training Center that provides “support for the enhancement of international competitiveness of Japanese athletes in cooperation with the Japanese Olympic Committee”) told me that the daycare was originally conceived as a place for the children of mother-athletes, but that they may also allow female coaches, administrators, and/or single-father athletes to use the facility in the near future. A high-level administrator at the JISS informed me that the daycare was part of a much larger effort, funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Monbukagaku shō), to explicitly increase the number and quality of female athletes, coaches, trainers, and administrators.39

This targeted government funding and the public discourse surrounding access to childcare for women in sports are merely two examples of the myriad ways that mama-san athletes are highlighting in a very visible way the issues regarding women and work in contemporary Japan. Prime Minister Abe has publicly “reversed course” on his prior position that women ought to stay home and raise their children, now stating explicitly that women in the paid labor force are essential to recharging Japan’s economy. By 2020 (not coincidentally the next time the global spotlight will be on Japan for the Summer Olympics), the Prime Minister would like to see women occupying 30% of all “leadership” positions, including in the government and in corporations.40 Although his motives are questionable and the actual number of women entering the workforce has not increased significantly in recent years, the public dialogue on the topic has increased, and this includes positive media exposure of mama-san senshu.

|

|

|

| Three photos of high-jumper Fukumoto Miyuki’s family from the summer of 2013 – the first is an Asahi Shinbun article (July 22, 2013) about her getting strength from her family to jump well, the next, from nikkansports.com (Aug. 15, 2013) is from an article about her husband and three-year old daughter supporting her from the stands (accessed Jan. 27, 2014), and the third is from rikujouweb.com, a website that follows the performance of Japanese track and field athletes (accessed Jan. 28, 2014) |

Mama-san senshu put a (healthy and friendly) face to the phenomenon that the government knows must occur in order to boost Japan’s labor force and raise the fertility rate – women returning to work with seeming ease and support shortly after giving birth.41 However, the efforts made thus far to expand subsidized childcare facilities (which are currently notoriously insufficient and have extensive waitlists) have not kept pace with the number of women wishing to re-enter the workforce.42 Moreover, history has shown that pro-natalist government intervention, in Japan as elsewhere, tends not to be immediately (or at all) effective.43 While social attitudes towards motherhood are certain to be slow to change, the positive light in which mama-san senshu today are portrayed hints at some kind of social acceptance towards Japanese women remaining “active” after childbirth, whether on the playing field or in a more traditional work environment. While women’s bodies will indeed always be “adapted for the perpetuation of the species,” the growing acceptance and promotion of mother-athletes offers hope that Japanese men and women are stepping away from the idea that one’s physiology must dictate one’s decisions in life.

|

Distance runner and mama-san senshu, Akaba Yukiko (far right) accepting her 2013 “Best Mother Award.” (From the Yomiuri Shinbun, May 10, 2013 “1児の母、赤羽有紀子選手に「ベストマザー賞」” (accessed Jan. 28, 2014) |

Robin Kietlinski is Assistant Professor of History at LaGuardia Community College of the City University of New York. She is the author of Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011), and has contributed chapters to Sport, Memory and Nationhood in Japan: Remembering the Glory Days (London: Routledge, 2012) and The East Asian Olympiads, 1934-2008: Building Bodies and Nations in Japan, Korea, and China (Boston: Brill, 2011). Her research focuses on the intersections between sports and society in modern and contemporary Japan.

|

Daycare facility that opened in the summer of 2013 at the Ajinomoto National Training Center in Tokyo (photo by author, July 2013) |

Recommended citation: Robin Kietlinski, “Sports, Motherhood, and the Female Body in Contemporary Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 27, No. 3, July 7, 2014.

Notes

1 Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (translation by H.M. Parshley of Le deuxième sexe) New York: Knopf, 1953, p.484

2 The headline from the show that broke her story on July 1st in fact mentioned Ando’s goal of training for Sochi, but the media focused on her skating career over her status as a single mother. One of many examples of such follow-up material includes this Mainichi Shinbun article from Sept. 18, 2013, which focuses on her participation in a German skating tournament on Sept. 26th as a “first step towards a comeback for Sochi”. The Asahi Shinbun compiled news stories related to Ando and the birth of her daughter, and as the headlines (in Japanese) indicate the focus is almost exclusively on her come-back (fukkatsu) and her return (fukki) to figure skating (accessed Jan. 13, 2014).

3 There are many complex biological and ideological explanations for women’s status in sports relative to their male counterparts. These explanations vary greatly depending on where and when you look at the history of women in sports, and there remains great disparity across the globe with respect to how (acceptably) involved women are in sports. The powerful ideologies that have led competitive sports to (still) be seen as a “man’s world” are, in my opinion, informed by deeply entrenched social attitudes towards the female body and its capacity to bear children. For a comprehensive discussion of the role that biological differences have played in the development of women’s sports, see Jennifer Hargreaves, Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of Women’s Sport (New York: Routledge, 1994). Chapter 5 (“Recreative and Competitive Sports: Expansion and Containment”) discusses “the constant focus on biology” and the enduring effect that many (scientifically-proven incorrect) theories have had on the legitimation of female sports (pp. 105-107).

4 As Allen Guttmann has delineated in several books, processes of secularization and rationalization mark the transition from “traditional” to “modern” sports. Modern sports are also highly specialized, bureaucratically organized, and require quantification and/or records (see Guttmann (1991), p. 67).

5 See Cahn, Susan K. Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Women’s Sport. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994, p. 9.

6 “The energy of a human body being a definite and not inexhaustible quantity, can it bear, without injury, an excessive mental drain as well as the natural physical drain which is so great at that time? […] Nor does it matter greatly by what channel the energy be expended; if it be used in one way it is not available for use in another. When Nature spends in one direction, she must economise in another direction.” Maudsley, Henry. “Sex in Mind and Education,” The Fortnightly Review, vol. 15, 1874, p. 467

7 Verbrugge, Martha H. “Recreating the Body: Women’s Physical Education and the Science of Sex Differences in America, 1900-1940.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 71.2 (1997), p. 286

8 A recent public debate over the impact of sports on women’s reproductive organs concerned the inclusion of women’s ski jumping in the Olympic Games (a sport that was not included until the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi). The president of the International Ski Federation (FIS), Gian Franco Kasper (who is also a member of the International Olympic Committee) said in 2005 that he opposed women’s ski jumping because it “seems not to be appropriate for ladies from a medical point of view.” (“Sochi 2014: Women’s ski jumpers ready to prove their Olympic mettle.” The Washington Post, Feb. 3, 2014, accessed Feb. 26, 2014).

9 Prakash, Padma. “Women and Sports: Extending Limits to Physical Expression.” Economic and Political Weekly. Vol. 25, No. 17 (April 28, 1990), p. WS-25. It should be noted that the number of scientific studies on pregnant athletes are few, but that anecdotal evidence supporting the notion that physical activity does not hinder pregnancy and/or childbirth is abundant.

10 The most famous was Francina “Fanny” Blankers-Koen, a Dutch track and field star dubbed “the Flying Housewife,” who won four gold medals at the 1948 Summer Olympics. She had also competed at the Olympics in 1936, prior to the birth of her two children, but had not won any medals.

11 Lorber, Judith. “Believing is Seeing: Biology as Ideology.” Gender and Society, Vol. 7, No. 4, Dec. 1993 (p. 572)

12 Prakash, p. WS-20

13 King, Helen. “The Sexual Politics of Sport: An Australian Perspective.” Sport in History, ed. Richard Cashman and Michael McKernan (Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1979), p. 72

14 The term eugenics comes from the Greek roots “good” and “generation,” and was first used to refer to the “science” of good breeding around 1883. “Eugenics movement reaches its height: 1923” PBS People and Discoveries: A Science Odyssey

15 Interestingly, women’s sports in ancient Greece were also promoted for eugenic reasons. Writing in the 1st century AD (about the ancient Greeks five centuries prior), Plutarch noted, “He ordered the maidens to exercise themselves with wrestling, running, throwing the discus, and casting the javelin, to the end that the fruit they conceived might, in strong and healthy bodies, take firmer root and find better growth, and withal that they, with this greater vigor, might be the more able to undergo the pains of child-bearing.” In Guttmann (1991), p. 24

16「「女性は子供産む機械」柳沢厚労相、少子化巡り発言」Asahi shinbun, Jan. 28, 2007. Yanagisawa later apologized by rephrasing his statement to say that women were “people whose role it is to give birth.”

17 Quoted in Mackie, Vera. Feminism in Modern Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003., p. 25.

18 Ibid, p. 112.

19 “Maternalism,” as defined by Kathleen Uno is “belief in motherhood as an idea validating policies or public actions.” (Uno, Kathleen. “Maternalism in Modern Japan.” Journal of Women’s History. Fall 1993, Vol. 5, Issue 2, p.126

20 For a detailed history od the development of women’s corporate volleyball teams and their relationship to the textile industry, see Helen Macnaughtan’s “The Oriental Witches: Women, Volleyball, and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics” (Sport in History, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2014, pp. 134-156).

21 Mackie, 105

22 According to World Bank data, Japan’s fertility rate dropped below 1.5 children per woman in 1994, and has not topped 1.5 since.

23 A number of anthropological and sociological studies of motherhood in contemporary Japanese society confirm this observation. Mariko Fujita’s article, “’It’s All Mother’s Fault’: Childcare and the Socialization of Working Mothers in Japan” (Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1, Winter 1989, 67-91), considers historical and institutional explanations for the exalted position of motherhood in contemporary Japan. For example, popular proverbs such as 三つ子の魂百まで (mitsugo no tamashii hyaku made; “whatever children receive in their first three years will last until they are a hundred years old”) have influenced social perceptions of early childhood and a mother’s important role during that period. The idea that no one can substitute for what a mother does for her own family was promoted as official, national policy in the 1960s and 70s, with a government committee comprised of LDP Diet Members adopting a Family Charter (katei kenshō) that said “A woman should recognize herself as the best educator of her child […] It is also a fundamental right of children to be raised by their own mothers.” In other words, the Japanese government’s official recommendation during Japan’s high-growth era was that working women should and would stop working while their women are young (Fujita, 72-73). While current Prime Minister Abe Shinzō has vowed to increase daycare facilities and extend maternity leave for working mothers, many are doubtful that these institutional changes will do much to change the male-dominated corporate culture that values long working hours.

24 Most famously, track and field star Hitomi Kinue.

25 For a detailed history on the prejudices faced by Japan’s early elite sportswomen, see Chapter 4, “From Calisthenics to Competition: Early Participation in International Sport,” in Kietlinski, Robin. Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo. London: Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2011.

26 Perhaps most influential was the Dutch “Flying Housewife,” Blankers-Koen (see footnote 9)

27 Otomo Rio, who was a student in Tokyo at the time of the 1964 Games, draws a connection between the Olympics, physical bodies, and the Japanese nation when she writes, “by watching the smaller figures of Japanese athletes competing well against the much larger physiques of Europeans, Americans and Russians, Japanese audiences could re-imagine Japan as a unified nation-state. The momentum of this, which was imagined as the birth of a renewed nation, was produced through a particular discourse of the body which […] harks back to Japan’s’ modernization project from the Meiji period.” (Otomo, Rio. “Narratives, the Body and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.” Asian Studies Review, June 2007, Vo. 31, p. 118)

28 One of the most enduring memories of the Tokyo Olympics for many Japanese is that of the women’s volleyball team, which defeated the Soviet Union to win the gold medal. While none of the women known as the “Witches of the Orient” (tōyō no majo) were mothers yet, media coverage still focused incessantly on their potential roles as wives and mothers. As Otomo Rio recounts, “A popular narrative that repeatedly appeared in the media was that Coach Daimatsu would never allow the girls to take a day off from their training, even when they were experiencing period pain. He himself writes: ‘As they keep practicing a year or two even with their periods, they will have bodies that can endure the same practice even with cramps. […] [W]henever they face games, their period no longer hampers their performance.’” (Otomo, 121-2). Helen MacNaughtan has also explored the history of Japanese women’s volleyball and the public focus on the personal lives of the athletes in her recent article, “The Oriental Witches: Women, Volleyball, and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics” (Sport in History, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2014, pp. 134-156).

29 Hiroyama continued competing until the age of 40, at which point she “retired” from running and gave birth to a daughter at the age of 41. In February 2012, she returned postpartum to run the Tokyo Marathon at the age of 43. Her advanced maternal age and return to running following birth were widely reported in the media. The common trend in Japan of female distance runners marrying their male coaches is a topic worthy of further research.

30 She also took part in the first-ever Olympic judo events for women in Barcelona in 1992, from which she brought home a silver medal.

31 Tani was elected to the Upper House of the Diet as a member of the Democratic Party in 2010. She announced in July 2012 that she was leaving the Democratic Party to join the People’s Life First Party (seikatsu no tō).

32 As this list of athletes attests, elite Japanese “mother athletes” compete in diverse sports, from the more traditionally “feminine” sports such as gymnastics and figure skating, to sports that have traditionally been considered less appropriate for women such as distance running and judo (which were excluded for women from the Olympics until the 1980s and 90s, respectively). While a detailed discussion of how exactly motherhood intersects with these very different sports is beyond the scope of this paper, more detail on this topic can be found in Chapter 8 (“Theoretical Concerns Surrounding Japanese Women in Sport”) under the subheading “Spectacle/Performance” of Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo.

33 It is noteworthy that, while “sportswoman” was not initially a category for the “best mother award” (awards were given in the music, entertainment and cultural categories), it was added as a category in 2010 and has been awarded annually since. (See here.)

34 Kimura Kaori and Raita Kyoko「子どもをもつ男女両性の選手の新聞報道の分析:ジェンダーイメージの観点から」Unpublished conference paper (20th annual meeting of the Japan Society of Sport Sociology, June 25, 2011) cited with permission from author. As Raita herself asked me after I mentioned my interest in “mama-san senshu” at a recent conference presentation I was giving in Tokyo, “Why do we never hear about “papa-san senshu?”

35 Official population trends and future projections made by the National Institute of Population and Social security Research can be seen here.

36 Explicitly, Prime Minister Abe has publicly proposed creating “an environment in which women find it comfortable to work and […] be active in society.” As Ayako Kano and Vera Mackie point out in their article, “Is Shinzo Abe really a feminist?” (East Asia Forum, Nov. 9, 2013) there is reason to be skeptical of Abe’s feminist posture, given past statements and actions he has made. They posit that Abe’s use of the term “womenomics” is fundamentally aimed at “recharging the economy and refortifying the nation, not […] improving the situation of women.” (retrieved March 18, 2014)

37 Sanspo.com article, 「ママさん選手要望、NTC内に託児所設置は」 Dec. 20, 2012 (retrieved Feb. 4, 2013)

38 Asahi Shinbun article, 「ママさん選手を支援、トレセンに託児室予約制無料」 June 9, 2013 (retrieved Jan. 6, 2014)

39 The exact amount dedicated to this project by the Monbukagaku shō was 467,314,000 Japanese yen, or approximately US$4.5 million (JISS internal document, available upon request).

40 “Japanese Women and Work: Holding Back Half the Nation.” The Economist, March 29th 2014 (here, accessed June 13, 2014).

41 Newly-elected Tokyo Governor Masuzoe Yoichi ran on a campaign that directly addressed the need to increase daycare facilities, an issue he also tackled while serving as health minister from 2007-2009 (here, accessed Feb. 10, 2014).

42 Prime Minister Abe has promised to put another 800 billion yen (US$8 billion) into government-funded subsidized daycare. However, given that parents are only expected to contribute 20% of the overall cost of subsidized daycare, the Journal predicts that the influx of yen will merely expand subsidies “without tackling the underlying challenges facing the market.” (“Japan Cries Out for Daycare,” Wall Street Journal, Aug. 7, 2013, accessed March 23, 2014)

43 For a comprehensive review of Japan’s pro-natalist policies, including an analysis of their effect on fertility trends in contemporary Japan, see demographer Li Ma’s “ Social Policy and Childbearing Behavior in Japan since the 1960s – An Individual Level Perspective” (here, accessed Feb. 14, 2014). The author concludes that, “the pro-natalist policies since the early 1990s had no visible effects on the second and third birth rates in Japan, but that a possible positive impact of the policies on the first birth is discerned” (p. 39).