“What is important, I think, is to feel that something is real. I feel that “sloppy” things are real. If I were asked “Why?,” though, I could only reply, “Because that’s who I am.” I suppose I could puff myself up and say “Because the world is a sloppy place, that’s why.” This world is half-baked, half-assed, all Buddhist “impermanence” – such that when you say this, it is really that, and when you think you have it here, it is over there. So yes, all that we know for sure is that we are always in the process of change. So what happens when the world changes? Well, the world is going to end, of course. So there you have it, that’s why I want to continue to be half-baked and half-assed. People are born sloppily, are treated sloppily, go on to die sloppily – we are the king of sloppy. What about human life, “a person’s life is worth the weight of the world,” you think, but a stupid-ass war comes along and life is easily lost and its worth re-calculated irresponsibly there on the spot. If you try to attain perfection, you’ll just be fooled. Deceived by others, by yourself, by your body, by time, by the world, you’ll just be fooled. If you see a joyous person saying “Perfect…!” you can go ahead, kick his knee in from behind…”

Shiriagari Kotobuki, “Conversation about ‘Expressive Sloppiness’”1

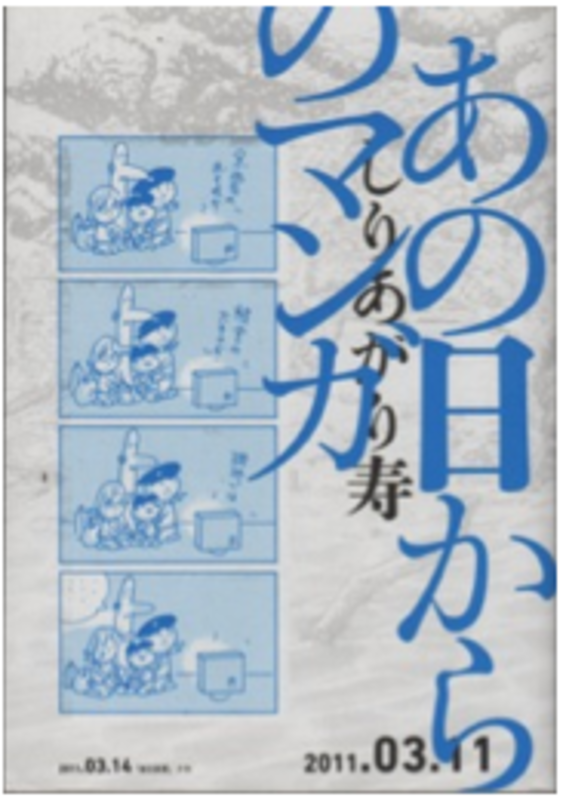

The 2011 disasters of first earthquake and tsunami, followed by the reactor meltdowns and weeks of aftershocks, continue today due to the lingering crisis at Fukushima Daiichi. These events, known as “3.11,” compounded the precarity in recessionary Japan – literally displacing the ibasho (home, and sense of belonging) of hundreds of thousands in Tohoku – and deepened a quotidian experience of malaise at a crisis constantly in the news, with no end in sight. Emerging at a time of national crisis when many hesitated to speak up was the manga artist, Shiriagari Kotobuki. Although published three years ago, Shiriagari’s Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Ano hi kara no manga: 2011.3.11, 2011), received recognition just this past May with the 2014 Medal of Honor for Culture (Purple Ribbon) from the Emperor.2 Manga Ever Since collects manga that, beginning mere days after March 11, 2011, steadily folded the experience of the disaster into readers’ everyday lives. Although the title of Shiriagari’s collection, Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11, suggests that Shiriagari’s work changed after that fateful day, what really changed was the serious attention his manga garnered when he dared to take the crisis as subject matter for humor and commentary so soon after 3.11.3 He has continued to do so “ever since.”

Shiriagari Kotobuki’s artistic response at a time of national trauma was commemorated on the second-year anniversary of 3.11 when NHK aired a special feature about Manga Ever Since, and again in this third year, with the Imperial Medal of Honor. Why did Shiriagari’s manga gain, and sustain, such attention? I will show that Shiriagari’s manga captured the panoply of emotions that rocked the nation in the days, weeks, and months after 3.11, notably refusing to tiptoe around touchy issues even while presenting itself as “just manga.” Shiriagari continues to take the pulse of everyday Japan as the nuclear problems at Fukushima Daiichi persist, asking his readers to “wake up” from the enervating disaster malaise even as he refuses to trivialize that response.

|

Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Ano hi kara no manga: 2011.3.11, Enterbrain, 2011). |

Despite his recent acclaim, though, Shiriagari is hardly a household name, much less a candidate for “Cool Japan.”4 From Godzilla and Akira to Murakami Takashi and Naruto, Cool Japan has long found inspiration in what Freda Freiberg once called Japan’s imagination of the “postnuclear sublime,”5 not to mention its fascination with kawaii or retro-fitted cultural traditions. If Cool Japan artists can be said to package their Japan-themed goods in both savvy and formulaic ways, often for overseas consumption, Shiriagari’s style of manga has somehow failed to attract a similar audience, and his gags and surreal stories apparently defy translation across cultural contexts.6 Cool Japan has so far found no poster boy in “the King of Sloppy,” as Shiriagari describes himself (and us) in the epigraph above. Even if Disaster Japan were to become the next avatar of Cool Japan, Shiriagari’s work might not fit the bill.7

Pervasive scenes of phallic mushroom spectacles all but define the postnuclear sublime, yet before 3.11, few cultural works had taken up the more mundane dangers in our back yards, of nuclear power plants. Works by Mizuki Shigeru and shōjo manga artist Yamagishi Ryōko are exceptions. These mangaka educate and dramatize the precarious working conditions of “nuclear gypsies” and the invisible realities of radioactive contamination from nuclear power plants at Chernobyl and Fukushima.8 Less didactically and often less representational in style than either Mizuki or Yamagishi, Shiriagari’s Manga Ever Since depicts the daily shocks and absurdities following in the wake of 3.11, and links them to the working lives, domestic spaces, and collective psyche of his readers. At that volatile time, though, Shiriagari also risked alienating the public with “unseemly” gag humor and social criticism.

Two key terms, “gag” and “stuplimity,” shape the argument here on Shiriagari’s 3.11 manga. The “gag” refers of course to Shiriagari’s humor, from his corny oyaji gags to black humor and parody, but also to the manga medium itself, a graphic and often experimental mode of serial storytelling uneasily sited between high and low-brow, high art and low-tech graffiti.9 Shiriagari’s Manga Ever Since is comprised of story manga episodes as well as gag manga. “Story manga” develop fictions in chapters or serialized episodes, much as a novel might, while gyaggu manga as a genre are usually in four panels (yonkoma), and have no “story” beyond episodic scenes with recurring characters and places serially over time. Even more broadly, the idea of “gag” ranges in meaning from comic relief in a longer dramatic piece to what might best be compared to physical humor or slapstick (Akatsuka Fujio’s Tensai Bakabon, for instance). At their cheapest, gags are sophomoric. Delivered at someone else’s expense, gags seize any opening to poke fun (ageashitori) at their target. At their worst, gag jokes’ nitpicking may look like bullying. Most importantly for my purposes here, gag humor need not be funny at all, whether staging an obvious joke that falls flat or providing an ochi (punchline) that fails to meet its target. Yoshida Sensha’s 4-koma works or Igarashi Mikio’s Bonobono notoriously leave readers scratching their heads as often as laughing. It is this deflated, diverted, or suspended quality itself, as humor settles for a modest object or gives up the punchline altogether, that can make gag manga unexpectedly flat or serious, extend its humor beyond the episodic easy laugh, or divert it into our everyday beyond the fourth wall.10 We might also mention here the risks of humor amidst enforced or unspoken “gag rules” on what can or should be the subject of humor.

Secondly, Sianne Ngai’s term “stuplimity” was coined in the context of the burgeoning, and wide-ranging, field of affect studies, and I adapt it here from Ngai’s application of it to modernist and contemporary literature and art.11 In her book, Ugly Feelings (2005), Ngai discusses “emotions” as the feelings a character might have, or feelings that belong to a 1st-person subject, be it character, writer, or reader. She notes that such emotions are usually distinguished from “affect,” which evokes something rather more like “mood” or “atmosphere,” enveloped in ambiguous 3rd-person modalities. Although affect suggests at times a Benjamin-like “aura,” it is often less sacred and lofty than that; rather, affect connotes an aesthetic “environment,” a hybrid sensorial and emotional medium of sorts, in which readers, context, and text meet. Ngai’s study focuses on affect as it interacts with emotions, confusing 1st and 3rd-person perspectives and stirring up “ugly feelings,” those minor affects such as irritation, anxiety, envy, and paranoia that are dysphoric and hum alongside the everyday in persistent, and rather annoying, ways. Unlike major, less hybrid, affects with their more disruptive force and power, such as joy, anger, or the sublime, our “ugly feelings” resist Aristotelian cathartic release and capture in beautiful forms.12 Instead, they are characterized by a kind of blockage, an inability to express or move into clear channels. In the end, it is this blockage, in all its muddiness, nagging repetition, and irritation, that best describes the tenor of the everyday in Shiriagari’s work, and thus the aptness of “nuclear stuplimity” for representing politics and aesthetics in post-3.11 Japan.13

Through the lens of Shiriagari’s manga, we see how nuclear stuplimity as disaster fatigue in Japan’s affective environment today indexes a widespread sense of neoliberal suspended action: citizen attempts to get accurate and reliable information to act on are regularly frustrated amidst a surfeit of complicated and contradictory data.14 Chronic cynicism and hopelessness abound regarding Japan’s future direction. Even before the triple disaster in 2011, Anne Allison had begun to document the strains on the social and civic fabric in post-Fordist and post-Bubble recessionary Japan that she would diagnose as a new kind of “precarity.”15 Allison paints a bleak vision of destabilizing rates of unemployment, suicide, and disaffection, as citizens young and old struggle to find their place (ibasho) in a shifting social and economic landscape. Stupefaction describes the intelligent citizen’s response to the Orwellian mendacities behind the incompetent actions of TEPCO and the inadequate measures taken by Japan’s government in the face of such instabilities, for which Fukushima Daiichi acts as a metyonym. With Manga Ever Since, Shiriagari picks up this reception amidst the crackle of background radiation, to resonate less as the sublime and rather more as “nuclear stuplimity.”16

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki) |

Shiriagari’s Manga Before, and Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11

Largely untranslated and unknown in North America, Shiriagari’s work has a solid following in Japan and some recognition in Europe.17 He was born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1958 as Mochizuki Toshiki (望月寿城) and graduated from Tama Art University in 1981.18 Afterwards, he worked in public relations and brand advertising as a salaried worker at a major beer company. By 1985, he was already trying his hand as a professional mangaka and quit his day job once he began to meet some success. Based on recent television commercials that use his Yurumation characters and the long-running success of his 4-koma strip serialized in the Asahi Shimbun evening edition, “Defenders of the Planet” (Chikyuu boueike no hitobito), it is hard not to label him mainstream. Manga devotees, though, know another side to Shiriagari: his adult-themed surreal and alternative gekiga for AX, his hallucinatory serials in Comic Beam next to the controversial manga of Suehiro Maruo, and the irreverent antics of the manzai-like pair of naked “twin old geezers” (futago no oyaji).19 He has won numerous prestigious manga awards, including the Tezuka Osamu Manga Prize for Yaji Kita in DEEP (2001). Adapted with English subtitles for Kudō Kankurō’s hilarious film, Yaji and Kita: Midnight Pilgrims (2005), his parodic work riffs off of Jippensha Ikku’s Tokaido road classic. The story features two gay lovers on a psychedelic pilgrimage to find the nature of reality and cure Kita of his addiction to heroin. They travel from the Tokugawa era in and out of our contemporary times to that most loaded of sacred sites, Ise Shrine.20

|

Yaji and Kita: Midnight Pilgrims (Dir. Kudō Kankurō, Mayonaka no Yajisan Kitasan, 2005), based on Shiriagari Kotobuki’s manga |

As pointed out in the NHK documentary on Manga Ever Since that aired on the second anniversary of 3.11 in 2013, Shiriagari’s earlier manga did not neglect apocalyptic themes of nature’s power. For instance, Hakobune (The Ark, 2000) depicts an Old Testament-like rain that starts one day and just as simply does not stop until everyone is drowned, while Jacaranda (2005) depicts the literal upheaval of Tokyo by a giant tree whose roots and branches rip open the city’s infrastructure and cause fires and explosions that kill off the population. Most startling, perhaps, in its relation to 3.11, is the recent re-issue of Gerogero Puusuka: Kodomo Miraishi (Gerogero Puuska: Death of the Children’s Future, 2006-7), originally conceived in response to Chernobyl. In this manga’s world of radiation contamination, only old people with slow metabolism and children under fourteen can survive, and the former try to exploit the latter to prolong their “civilization.” The circular narrative of disjointed and surreal episodes begins and ends with a single child left to wander in a nuclear winter.

The volume Manga Ever Since suggests that Shiriagari’s already apocalyptic work had entered a new phase. Appearing in it are disaster-related original pieces, as well as longer episodes of the twin old geezers (futago no oyaji) and 4-koma “Defenders of the Planet,” which came out in the Asahi Shimbun soon after March 11th. Not unlike collected volumes of “Defenders of the Planet,” which are organized chronologically by publication date and with detailed timelines of the current events from Japan’s history, politics, and popular culture that shaped the comics, Manga Ever Since: 3.11 too is arranged as a historical chronicle of the impact of 3.11’s unfolding, both on Japan and the artist. When their stories ventriloquize his trip to the disaster-hit area a month after 3.11, Shiriagari temporarily merges with his comical Defenders out to save the world in their spare time.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, Asahi Shimbun newspaper article, “The “We” Who Made a Huge Bet, and Lost” [Ookina kake ni maketa bokutachi wa], from 2011 May 24, included in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain Publishers) |

Traveling to Iwate for Asahi Shimbun and as a private citizen, Shiriagari’s role expanded despite himself into a kind of “public mangaka” and journalist. Consequently, his work became bound up in thorny questions of whose disaster it is and just what kind of disaster it constitutes; in the end, as he invariably notes in interviews, it was only after going to Tohoku in the weeks following the disaster and seeing it firsthand that he felt not only more free to write about it, but also the imperative to do so. Reinforcing the relationship between current events and the Tokyo-based artist’s experiences of them, Manga Ever Since interpolates among the manga an Asahi Shimbun newspaper account of Shiriagari’s trip to Tohoku’s Morioka City. In the article he claims that we made what we thought was a sure bet on the safety of nuclear power, only to lose that bet; now we have to reckon with our blind spots in ever having gambled with such arrogant certainty. His work expresses the affective impact of 3.11 reverberating outside and beyond the epicenter of the disaster as a burden to be shared by all, not just the people of Tohoku. In so doing, his manga thwarts readers’ desires for normalcy or forgetting that can cordon off the disaster zone both psychically and geographically as disaster fatigue sets in.21

|

World manga artists contributed to the original French (and subsequent Japanese) collection, Magnitude Zero (Mind Creators LLC, 2012), including Shiriagari Kotobuki (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Mind Creators, LLC) |

As part of a French exhibition and book project called “Magnitude Zero” that collected international manga artists’ responses to 3.11 in 2012, Shiriagari contributed a color version of a panel from near the end of what was originally a black-and-white story manga in Manga Ever Since.22 In it, cherubic winged children fly over a now verdant landscape dotted with windmills around Fukushima’s reactors on the coast. Entitled “The Village by the Sea” (Umibe no mura), the story is set fifty years in the future after 3.11 when everything has a solar panel slapped on it. Watching the TV news on the momentous day when the last drop of oil is sucked from the earth, the older generations lament the good old days of comfort and ease with electricity, warmth, and lights at night, while the children have no memory of this, having only known the world since 3.11 of sporadic electricity, solar panels, and travel by air balloons and bicycles. The manga tells us that just as the dinosaurs avoided complete extinction by adapting into birds, children after 3.11 have evolved, too, born with wings to cope with a new world. This leads to the panel depicting the naked children flying over a wind farm around the old Fukushima reactors. Taken out of context for Magnitude Zero, this appears to be a hopeful image, one that borrows Cool Japan iconography; at the very least, we see that Shiriagari actually can draw, and that his mode is not necessarily “sloppy” or expressionistic. But Shiriagari’s drawings are often more detailed and representational when in the service of satire or a surreal storyline, and this manga too actually concludes more ambivalently, in the way of dysphoric affects. When it is announced that the village now has the means to build a new power plant and go back to the good ol’ days of electricity, however much and whenever desired, an old bedridden jijii able to gauge both worlds and on the verge of dying, agonistically cries out to the night sky that, before, he had never been able to see so many stars.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki’s manga in Magnitude Zero is a colorized panel excerpted from Manga Ever Since (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Mind Creators, LLC) |

The Stuplime Disenchantment of the Everyday

Before and after 3.11, Shiriagari’s work has flown under the radar of most overseas fans drawn to Cool Japan consumer culture. His gag humor, surreal or nonsensical (kudaranai) stories, and his “sloppy” (zonzai) aesthetics challenge linguistic and cultural translation. His hetauma style of drawing mocks graphic high art and at times mimetic representation itself by insisting on scribbled figures that all look alike, as big-headed childish oyaji (old men). Even his more realistically drawn manga reveal a guerrilla artist’s commitment to graffiti-like expressionism. This “sloppy” aesthetic appears to be diametrically opposed to the slick, postnuclear sublime of Japan Cool, and yet, we should not forget that the sublime too was once a challenge to the conventional category of the beautiful.

The sublime is even more apt for 3.11’s natural catastrophe than it has been for the Bomb.23 After all, as an aesthetic mode, the sublime describes the subjective state of awe and terror in the face of omnipotent Nature. Philosophers from Longinus to Kant merge with political thinkers such as Edmund Burke, and Romantic poets and Gothic writers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in theorizing a transcendental natural force that the mind, in the end, subdues in order to harness Nature’s power for the purposes of art. Thoroughly mediated, first by artistic subjectivity and then by the intellect and art’s form, the sublime begun in unspeakable awe at Nature ends up articulated in the viewer’s experience of an aesthetic product (even if, strictly speaking, unable to reside in any object per se).24 The aesthetic language of the sublime also establishes a rhetoric of brute power in nature that rivals beauty, with both competing as experiential qualities evoked by the work of art. The jaw-dropping video footage and photography of 3.11’s earthquake and tsunami certainly inspire the unspeakable terror of nature’s destructive force. Where this sublime falters is in capturing the unresolved crisis simmering into its fourth year, an ongoing man-made disaster in Fukushima of corporate and governmental ineptitude at either meeting the needs of displaced populations in Tohoku or allaying safety concerns of citizens throughout Japan.

Shiriagari’s “sloppy” aesthetics thwarts the sublime’s Romantic idealism by working from within the paralysis and enervation of the endless everyday. Manga Ever Since connects this new daily life to the prolonged disaster of 3.11. In his essays and blogs, Shiriagari makes clear that he chooses laughter and the quotidian because he distrusts idealism and the arrogance of authority figures.25 Certainly, his gag humor finds itself at home in the trite habits and details of everyday life, but humor in any medium may come across as “inappropriate” with tragic subject matter. Treating 3.11 in manga was more than a little risky so soon after the crisis began. Long before 3.11, though, Shiriagari had had to come to terms with humor as a dynamics of power, and nothing less than a tightrope of public acceptance or rejection. Moreover, he recognizes that the quotidian has its own dangers, which include its relentless temporal unfolding and the dictatorial ease with which it covers up or incorporates difference and dissent under repetitive normalcy. Without constant vigilance, he writes, the downside of being hitonami (just your average person) is losing one’s messy individualism in bourgeois comforts or desires for group belonging. Laughter and sloppy art are Shiriagari’s strategies to negotiate with the “real” and avoid either the awe-struck enchantments of the sublime or the soporific complacencies of the everyday (as the above epigraph makes clear).

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, Being Just Your Average Person (Hitonami to iu koto [Daiwa Shobō, 2008]) |

Predictably deprecating any suggestion that his art has serious social or political relevance, Shiriagari inevitably repeats that he is merely a gyaggu mangaka and getting laughs is his single-minded goal. Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Amahisa Masakazu’s Baka Drill, diverse works by Yoshida Sensha, and the gekiga-influenced Gakideka of Yamagami Tatsuhiko shaped Shiriagari’s own manga sensibility. And yet, despite his protestations, Shiriagari is not content to just give readers a ready laugh: in his essays and interviews, he says he wants his manga to wake readers up (jibun wa hito o kakusei saseru warai o yaru, 覚醒させる) from within the homeostatic illusions of everyday life. Since the 1980s, his surreal stories and gags have strived for this effect.26

We can see Shiriagari’s attention to the power dynamics in comedy when he divides his gag humor into two kinds, “stimulating” (kakusei) and “paralyzing” (mahi). The former generates laughter as readers “get” the joke, while the latter results in rejection, or the weaker “ha ha” of readers not “taking” it as very funny. Two other factors need to come into play as well: readers being made to laugh (warawaseru) or being reduced to laughter (warawareru). In making readers forget themselves, both types of laughter have an involuntary quality to them and remind us of the power tactics of manipulation and seduction. One would expect the former, being made to laugh, to match up with Shiriagari’s more active target, kakusei, but he actually aims for combinations of kakusei and warawareru. Aligned with his sloppy aesthetics, this combination worms its way into a reader’s consciousness to offer a new way of seeing or thinking until laughter marks the reader’s surrender. To laugh despite oneself strikes Shiriagari as more honest and fragile than warawaseru, which is literally forced; for him, warawaseru conjures up comedians’ canned professional techniques and preset scripts in a performance while the obedient laughter of its audience looks disturbingly akin to brainwashing.27

|

One of several volumes collecting “Defenders of the Planet,” Shiriagari Kotobuki’s 4-koma manga serialized in the Asahi Shimbun (Chikyū bōeike no hitobito [Asahi Shimbunsha, 2004) |

Deeply intertwined with Japan’s current affairs, Shiriagari’s 4-koma manga, in particular, emphasize the absurdities and banalities of everyday life from within which the nuclear contamination has emerged. The 3.11 crisis, prolonged by Fukushima Daiichi, comes to the average family of four that makes up Shiriagari’s “Defenders of the Planet” (Chikyū no bōeike no hitobito) the same way it reaches us: by television. Like Hasegawa Machiko’s long-running newspaper manga, Shiriagari’s family too lives a recognizable domestic life in Japan, but unlike Sazae-san (first appearing in 1946), Shiriagari’s manga collections are glossed by current event timelines and his Defenders’ idealism is exaggerated to the point of satire. Wearing their superhero bandanas, they are comically poised to fight injustice – if only they can figure out how, and only after first hanging up the laundry. Like the rest of the family, the father’s heart is in the right place, it is just that, like us, he is not really a superhero with special powers. This oyaji figure is deluded by his ideals, and it is his failures that resonate for us most. Shiriagari’s family of Defenders records in daily installments the difficulties of resuming normalcy three years after 3.11, and the widespread disbelief that everything is yet safe or under control.

The semantic slippage between Shiriagari’s characteristic oyaji characters – as jiji that stand for a range of male father figures but also current events (jiji, or 時事) – reinforces this manga’s mediation of real events of the day. We might even see Shiriagari’s jiji manga in a lineage with early twentieth-century satirical newspaper cartoonists for Tokyo Puck or to 4-koma manga artists such as Kitazawa Rakuten (1876-1955), writing for the newspaper Jiji Shimpō’s Jiji Manga section.28 Serialized for daily or weekly access in the domesticated reading venues of newspaper and comic magazines, Shiriagari’s childishly appealing if eccentric character types respond in regularly published episodes to Japan’s ongoing social, cultural, and political times. Embedded within detarame stories and silly puns, one finds controversial political topics such as the Yasukuni Shrine debates or the Iraq War. His manga treat equally human foibles, eschatological and scatological obsessions, and in a sustained fashion – precisely because it has dominated Japan’s psyche as thoroughly as its news conduits “ever since” – 3.11.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, Twin Old Geezers (Futago no oyaji [Seirinkogeisha, 2010]), originally appearing in the alternative manga magazine, AX, from as early as 1998 |

Shiriagari’s Futago no Oyaji

Manga Ever Since contains several episodes of “The Twin Old Geezers Go Downriver” (Kawakudari futago no oyaji), in which the two naked futago no oyaji encounter scenes downstream that can only be the effects of the catastrophe upstream. In the first episode, the twin old geezers run across an injured nuclear reactor, depicted as female, sitting by the banks of the river. She gives her name as “Genpatsu” (Watashi wa genpatsu; 私はゲンパツ) and proceeds to tell them her story. Although she had once believed herself loved, after the earthquake, she began to see that she had just been used, then casually dumped the minute a problem arose. Not the sort of woman to be easily tamed by her lovers, she acknowledges that perhaps she should not cast so much blame elsewhere. She concludes by telling the twin geezers to take a different stream, another course so to speak, and should they meet others like her along the way, to tell them that her fate is also theirs.

Before we examine gender, we might wonder at the very naming of the reactor as Genpatsu (ゲンパツ). Before 3.11, genpatsu denoted meanings that, “ever since,” have not been the same. Of course, “genpatsu” is simply an abbreviated form for genshiryoku hatsudensho (nuclear power plant) but post-3.11, its meaning oscillates anxiously between genbaku, as nuclear bomb, and bakuhatsu, explosion, precisely because now Fukushima reactors have exploded and imploded in meltdown; in other words, the line usually drawn between unsafe nuclear weapons fallout associated with the specter of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and safe nuclear reactors, has become as unstable as the homophonous syllables of the word genpatsu itself. In news reports on TV or headlines in Japanese newspapers, genpatsu is used to refer specifically to the Fukushima event despite the fact that a neologism to single out Fukushima could have been created at any time; in effect, then, all nuclear power plants have now been colored by Fukushima in the deluge of news (with almost all of Japan’s power plants shut down “ever since” as well). “Genpatsu” has erupted from within the everyday, where nuclear power is taken for granted, to alter that same flow of everyday news in uncanny ways. Near the conclusion of this episode of the futago no oyaji manga, we are put in the position of the clueless twin geezers who hear from the devastated genpatsu that it will be our responsibility to pass on her story to others we meet, as a cautionary tale of not just her, but every reactor’s, inevitable end.

Shiriagari talks about this manga episode briefly in the interview with youth culture critic and psychoanalyst Saito Tamaki on NHK.29 Shiriagari confirms that Genpatsu is a most unlucky woman, long fêted as the source of Green Energy and a solution to Global Warming; now, though, she is suddenly vilified as a demon even though what Genpatsu really is has fundamentally never changed — it is we who have changed. In this part of the interview, Shiriagari goes on to tap into our desires for someone to blame and someone, like the Defenders or a true leader, who will take down the bad guys who made this awful event happen. But what we are faced with years into this crisis is far from such a clear good guy/bad guy situation. It is much messier than that, more about negligence and incompetence and a kind of arifureta (banal everyday) corruption that arouses less sustainable outrage than hopelessness or cynical disgust. Most striking is his use of the term kitokuken (既得権), which refers to the privileges and rights we already hold. With this, Shiriagari leaves open the possibility that not the government and TEPCO alone but we too are the bad guys (warui yatsu), with our kitokuken, the retrenched privileges whose connections to the energy crisis we disavow.30 Like the bedridden oyaji in “The Village by the Sea,” we know the costs: we will lose our grasp on our human scale in the cosmos while also losing the stars to light pollution; moreover, we will continue to contaminate the planet for future generations. And yet, slaves to convenience (便奴, bendo), we are too caught up in our everyday lives and work to imagine restraints on our standards of living that would compel us to seek other ways to live more sanely.31 Enter nuclear stuplimity, as the homeostatic everyday with its small comforts and regular rhythms, its daily work and endless tasks that overwhelm us already, normalizes a crisis that might have awakened us to a more sustained political action.

In gendering Genpatsu female, Shiriagari tells the story of Japan’s peculiar love affair with nuclear power. Genpatsu as a woman (onna) leaking toxic pollution into the river resonates with the expression “poison woman” (dokufu no onna), associating her with female criminals and femme fatales; she stands for a dangerous love affair blind and greedy with desire, one that we knew all along could only end badly.32 Which takes us to this manga’s final panels, where our twin geezers learn that downstream are a cluster of healthy female genpatsu, who gossip precociously with their girlfriends about their love affairs. With this final panel, it is as if Shiriagari asks, Who is “flirting with disaster” here? Is it these girlish power plants ignoring warnings about the disaster upstream, reveling instead in newfound attention to their beauty and power? or us as their lovers, in short, “mankind” – as deluded as these coquettish power plants that a “breakup” could ever happen, on either side.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, final panels from Kawakudari futago no oyaji (“The Twin Old Geezers Go Downriver,” Episode 1 in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain Publishers) |

Shiriagari Kotobuki, from Kawakudari futago no oyaji (“The Twin Old Geezers Go Downriver,” Episode 1 in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain Publishers) |

Shiriagari Kotobuki, from Kawakudari futago no oyaji (“The Twin Old Geezers Go Downriver,” Episode 3 in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain Publishers) |

In another episode of the twin old geezers’ manga (dated 22 June 2011) our heroes take a trip into an impenetrable maze of jungle and streams that represents the lack of consensus on Japan’s present and future. Lost in the jungle, the futago no oyaji encounter a riot of chattering birds who comprise two stark oppositions, those who proclaim the sky is falling and those who pooh pooh such

alarmism and argue that everything is just fine. The twin geezers are caught between the two sides, as if between “hawks and doves,” screaming the same arguments for and against nuclear power’s safety, both before and after the explosion. The oyaji do not know where to go, standing in for the people not only in Tohoku but everywhere in Japan seeking transparency and truthful information from amidst the polarized and contradictory claims of politicians, TEPCO spokesmen, and “experts.”

As recurs in both his TV interview and in his 4-koma gag comics, Shiriagari here too has his twin old geezers ask where the leadership is that Japan so desperately needs. When a leader does emerge in the manga, a giant bird, it is only briefly in order to prevaricate and repeat that now infamous expression of politicians and TEPCO spokesmen during those first weeks and months after 3.11 that tadachini (“immediately” or “directly”) radioactive pollution will cause no harm to anyone. The implication, of course, is that the nature of the harm will be in accumulated effects that reveal themselves over time, differently in each body based on age and other factors, and in ways unknown or that may not always be “directly” traceable back to Fukushima. Recent Japan Communist Party posters make hay with the ironic resonance of this term, using it to advocate for a party platform of no more nuclear power.

|

“Right NOW, ‘Genpatsu Zero’: Let’s Protect Our Children from Radiation.” Japan Communist Party poster in Kyoto, Japan (February 2014) |

The experts and the scientists are represented by the two camps of birds who argue their chosen data sets and what they mean in terms of cause and effect, while everyday people in Japan find their representation in the twin old geezers who just want to get out of this dangerous morass safely.33 The twin oyaji experience the event affectively, overwhelmed intellectually and physiologically by confusing displays of scientific knowledge and reason that do not add up amidst environmental stimulation that screams invisible and impending danger. These affective intensities, more than concrete data and reasoning, guide the twin geezers to choices that help them to evade the worst of the danger in the final panel, if not quite get “out of the woods,” so to speak. Reaching forking paths in the river, they choose their course of action based on the direction in which one naked oyaji’s penis appears to point – as good a method as any on offer, this social satire suggests.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, final panels from Kawakudari futago no oyaji (“The Twin Old Geezers Go Downriver,” Episode 3 in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain Publishers) |

Defenders of the Planet

The opening panels of “Water and Sky” echo drawings of Tohoku rubble that appeared in the Asahi Shimbun on 6 May 2011 in lieu of the usual Defenders strip as the artist’s stupefied response to his April volunteer work there.

“Water and Sky” re-presents the shattered lives in the debris of Tohoku in almost Buddhist terms. Here, the debris is invisible underwater, while the future generation is born enfolded within the flowers of lotus plants rising above it all. The lotus, as a pristine flower that emerges victoriously and almost magically, spontaneously generated out of the swampy mud, is a phoenix-like symbol of rebirth. For Buddhism, the lotus symbolizes enlightenment precisely because it speaks to rising above, but also out from, the morass of this world with all its contaminations and evils in which we as human beings are rooted. In Shiriagari’s final silent manga we see the drowned parents and family members of Tohoku finally able to reunite with family and ascend in some peace to some heaven, thanks to their lotus children who are safe from continuing tsunami and earthquakes, swaying atop the longer slender stems of their plant homes.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, the wordless “Water and Sky,” in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain) |

The wordless panels of the Defenders 4-koma strip before it became “Water and Sky” suggests not so much the terror and awe-struck sublime as another kind of silence in the immediate wake of 3.11: the pressures of jishuku, or self-censorship.34 While experienced by all citizens in the wake of 3.11 as broadly an atmosphere of solemnity and an injunction to exercise self-censorship with regard to 3.11 out of respect for Tohoku’s dead and its displaced populations, it was experienced, and resisted, by journalists, academics, and artists in the public eye as an explicit and implicit “gag order.” Critics felt pressures to avoid political pontification, fictionalizing the tragedy, or even commenting on complicated science matters best left to “experts.”

A month after 3.11, on 12 April 2011, Shiriagari has his Defenders evoke the “jishuku mood” that has apparently lifted in time for hanami, the annual spring festivities. Although this manga relates what begins as an optimistic day – with the Defenders voting at the polls, seeing hanami going on despite the “jishuku mood,” and observing favorably a nearby “No Nukes” rally – in its wake, the final panel relays the maintenance of the political status quo in that day’s election results. Shiriagari here shows how apathy reasserts itself with the undercutting of democratic voices for change, connecting the disappointing election results and the silencing of protester’s “No Nukes” voices to jishuku’s continuing, invisible presence.

Within days of 3.11 (his first manga, which appears on the cover of Manga Ever Since, was on March 14th), and even as the jishuku mood deepened, Shiriagari continued to make 3.11 the subject in his art and stories, and the object of fundraising and volunteer events in Tohoku. The latter bleeds into the former via the medium of his Defenders who go to Tohoku like their creator and act somewhat as his mouthpiece. In this way, Shiriagari caricatures himself along with his Defenders, deflating his own importance as merely a rather stubborn oyaji comically ineffective against much larger forces.35

One of Shiriagari’s most powerful Defenders’ manga appeared in 2012, after Manga Ever Since was collected: it depicts Mom and Pops Defenders pondering what it means that hundreds of thousand-ton tanks of contaminated water are accumulating around Fukushima. The oyaji character compares it to not being able to flush his toilet at home, and instead having to put all his “shit” in tanks in his home until flushing becomes possible again. Just as in one’s home, Japan’s space for storage of such nasty materials is limited even as the supply has no apparent end. The gag here turns away from separating the two scenarios of Fukushima’s problem and ours at home in Tokyo (or elsewhere), and instead makes them into one daily and nagging domestic problem for us all.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, single-koma manga in Manga Ever Since: 2011.3.11 depicting a “New Famous Tourist Spot”: the statue of a naked cherubic boy urinating into a fountain, such as one finds all over Japan; here, however, he is pissing radioactive water (37). (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain) |

Nuclear Stuplimity

One of Shiriagari’s more cryptic manga from Manga Ever Since is entitled “Hope” (dated 22 May 2011). In his NHK interview, Shiriagari mostly sidesteps opportunities to interpret this particular manga beyond what is already on the page; however, he does admit that radioactive materials are in themselves neither good nor bad – they are just chemical elements. He was struck by the simple fact that, like it or not, they are out, and now that they have gotten out, there is no getting them back in. Rather than demonize, he decided to personify them (gijinka suru), imagining them as an anthropomorphized extended family (plutonium elders [長老], cesium big sisters [oneechan], strontium big brothers [anchan], and little iodine chibi children [ヨウ素]).

We are not allowed to learn their true identities for most of the manga; instead, we endure the pointless, silly gag humor of little iodines playing games to stave off their boredom. By the end, we realize these cartoony isotopes and radioactive elements are curious to get out of their world to meet us in ours. To what we may call tutelary effect, Shiriagari expresses their names and half-lives and “relative” relationships. As “family” in relation to one another, their names and half-lives become more easily remembered by Japanese everywhere who, in a post-3.11 world, can no longer avoid learning the chemistry and biology of radioactive elements, be they born in nature or only from a nuclear reactor or explosion. With this manga, Shiriagari makes visible and legible the invisible radioactive elements that, once identified and recognizable, provide strange comfort; made visible, they turn anxiety and paranoia into something “real.” The “nuclear neurotic,” suffering from affects as invisible and elusive as the radioactive particles themselves, finds relief in their measurable form and confirmed existence.36

The title’s kanji characters for “Hope” (希望), crossed out, speaks to the manga’s closing full-page panel of a realistically rendered

exploded genpatsu. With this conclusion, Shiriagari appears to refuse the “hope” of Fukushima as an isolated event; the “hope” that nuclear power may still be safe in earthquake-prone Japan or possible with aging power plants too expensive to decommission and rebuild with new technology; and the “hope” of unmitigated optimism for recovery when the suffering of so many continues three years later and an effective science of radioactive cleanup is revealed to be as “unanticipated” (soteigai) as the disaster itself. “Hope” registers the force with which the comic imagination plunges to earth in stark realism in the final panel’s rendering of the exploded genpatsu.

Here, of course, this final ruined “box” of a nuclear power plant acts as an explicit allusion not only to Fukushima but also to Pandora’s box.37 In bringing the latter mythical story to bear on Japan’s new reality, Shiriagari deliberately revises an origin story about the release into the world of all the evils, a catastrophe mitigated by at least “hope” remaining. The striking ambivalence of Shiriagari’s “Hope” crossed out with a giant batsu mark is that it both keeps the allusion and refuses its outcome; his revision leaves us with no “hope” left behind in the empty reactor “box,” and only very real radioactive particles and chemicals out of it that we must confront. Resorting to a “realistic” conclusion may even self-reflexively mock his own medium and tutelary aims, considering the now widespread appropriation of manga by government, corporate, and news media to calm the fears of, and educate, anxious viewers about complicated political and nuclear matters.38

Apparently, Shiriagari’s missing hope makes no room for a silver lining to disaster, either via the entertainment contents industry’s sublime mushroom clouds or by means of a “No Nukes” movement analogous to the “No More Hiroshimas” peace movement (itself frequently supportive of the nuclear power industry despite condemning nuclear weapons).39 Indeed, “Hope” appears to satirize equally aesthetic and political movements with its adventurous family of radioactive materials who promise to take their message of hope to the world, as if Atoms for Peace ambassadors.

For Shiriagari, in this manga, the disaster is out of the box; there is nothing to do but both cope with a new everyday reality where we all have to do the math of compound pollution with internal and external exposure as well as calculate new risks and learn chemistry. What choice do we have but to get to know our new radioactive “friends”?

Rather than Freda Freiberg’s “postnuclear sublime” in the Japan context (which builds on Frances Ferguson’s “nuclear sublime”) or Gennifer Weisenfeld’s “sublime of ruins,”40 regarding art’s response to the 1923 Kanto earthquake, Shiriagari presents us, I think, with what Ngai calls “stuplimity”: comical stupefaction at the sheer scale of the human-wrought crisis and our own passive impotence in the face of it.

While Kant’s sublime involves a confrontation with the natural and infinite, the unusual synthesis of excitation and fatigue I call “stuplimity” is a response to encounters with vast but bounded artificial systems, resulting in repetitive and often mechanical acts of enumeration, permutation and combination, and taxonomic classification. Though both encounters give rise to negative affect, “stuplimity” involves comic exhaustion rather than terror. The affective dimensions of the small subject’s encounter with a “total system”…. 41

Promulgated by government mouthpieces and “experts,” local activists, and such valuable NGO organizations as SafeCast, the numbers and data sets regularly available for our review ceaselessly list the kinds of radiation detected, where, how much, and when, asking us to piece together the sporadic facts and figures available that do not yet add up to any larger picture. Meanwhile, daily life continues, lived by rote amidst accumulating data that must be measured but whose significance is both deferred and opaque, at best.

Is it any wonder that Shiriagari’s “Hope” begins in sloppy drawings of radioactive characters’ kudaranai jokes and bored play and ends in their shocking inevitable escape into our present everyday? Breaking through the fourth wall, they effectively parody cathartic “release” and intellectual capture of the sublime’s terrible power. In the end, the sublime escapes us, leaving us more than three years later with an ongoing disaster and a swirling affective environment of stupefaction, confusion, and impotence. In our nuclear stuplimity, we are left holding the empty box, unable to grasp what it really means.

With decades of cleanup and decommissioning ahead at the Fukushima Daiichi site, the full dimensions of the dangers remain unclear as the catastrophe lingers, developing new complications. Few believe Prime Minister Abe Shinzō or trust the bureaucratic corporate and political systems that claim all is under control. Disaster fatigue continues to grind the citizenry down into irritable apathy and contempt with each day’s reports of ever more grim news. Any hope of political efficacy is mired in the larger machinery of neoliberal global capitalist production and political economy that are not easily changed and within which consumers and workers are complicit and mutually mired.42

Dysphoric feelings and blocked agency mark our nuclear stuplimity in response to 3.11’s massive natural disasters, overtaken as they have been by man-made mistakes of incompetence, mendacity, and revelations of ongoing corruption. Uneasy at appearing to advocate citizen quiescence and cynicism about change, Ngai counters with the need to preserve the ambiguity of disaffection in concepts such as stuplimity for whatever critical functionality they may yet yield. And yet, she admits that such “sentiments of disenchantment” necessarily retain their negative and minor valence.43 It would appear that, at best, their political usefulness lies in their vague descriptive appeal in diagnosing “blockage” and suspended agency, indexing by proximity some “historical truth” without prescribing any clear path forward. A sloppy reality, indeed.

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki, Sloppy Existence (Zonzaina Sonzai [Enterbrain, 2010]) |

Who Knew? Our “Sloppy Existence” Has Art in It

Shirigari favors the oyaji figure across so much of his corpus, perhaps because it is a character who can move across a wide swathe of experience: a clueless country bumpkin; a self-serving and childish paternal figure; a father trying, but failing, to be superman to his family; a straight-faced sidekick (tsukkomi) in a manzai comedy duo who may be funnier than the partner with the punch line (boke). As we have already noted, oyaji resonate with the daily news as jiji. In the nuclear context, we might even recall Azuma Zensaku, known as Uran Jiji (Old Man Uranium), who went “uranium hunting” around Japan with a Geiger counter in the more nuclear optimistic 1950s.44 Again and again, we see oyaji in Shiriagari’s twin old geezers, his Yurumation oyaji, his art installation projects, and in the scribbly drawings of personified radioactive particles.

To wake us up from our everydayness, Shiriagari juxtaposes corny oyaji puns and gags with content leads (neta) derived from real current events, or with a dark, surreal atmosphere that surrounds unwitting characters going about their lives. He calls the everydayness within which we are sunken, where such worlds mix, our “sloppy existence” (zonzaina sonzai) – the very subject of his art.45 Unlike art’s revolutionaries, Shiriagari turns away from political idealism or aesthetic absolutes; instead, he lends his manga art and limited celebrity to fundraising events for Tohoku and works the limits of both mainstream and alternative venues for his sloppy “comics.” In doing so, he tests the terrain of a dark imagination at the borders of our impotent, suspended agency, mired in the exigencies and threatened by the precarity of survival at life and work.

We might contrast the contemporary “relevance” and intent behind Shiriagari’s works in Manga Ever Since with other artists, such as ChimPom, for instance. This youthful group of guerilla artists staged several “happenings” in response to 3.11, and were featured in Emily Taguchi’s documentary “Atomic Artists” for PBS/Frontline.46 One of ChimPom’s most striking nuclear protests consisted of supplementing the “missing piece” in the famous mural in Shibuya station, “Myth of Tomorrow,” an act which appeared to those not angered by its “vandalism” as an original parody and even an homage to its artist, Okamoto Tarō (1911-1996). Writer Kanai Mieko, in her 2011 collected essays Chiisai mono, Okii koto [Little Things, Big Ideas], saw their action differently.47

|

Kanai Mieko, Small Things, Large Matters (Chiisai mono, Ookii koto (Asahi Shimbun Shuppan, 2013) |

Kanai notes that during the 2011 centennial celebrations of Okamoto’s life, it was impossible not to recall the role of his famous artist parents (the mangaka Okamoto Ippei and poet/writer Okamoto Kanoko) in his life, much less the sort of artistic activities he was popularly known for in the end. But it happened to fall in 2011, so she turns to Akasegawa Genpei’s parody of Okamoto in a nuclear context in the 1980s. In an essay from his collection Science and Poetry (Kagaku to jojou, 1989),

Akasegawa observes that power companies have recently had difficulty getting politicians on either the Right or the Left to appear in their PR campaigns. Soon Akasegawa is imagining Okamoto Tarō doing an ad for nuclear power companies since, it turns out, Okamoto was already a hit in a massively popular television commercial. The commercial that Akasegawa alludes to here is for Maxell videotapes, where the white piano Okamoto is playing explodes into the vibrant colors and strokes of a “Myth of Tomorrow”-like painting. Okamoto cries out the ochi-like slogan that would become an addictive catchphrase: “Geijutsu wa bakuhatsu da!” (Art is explosion!).48 Akasegawa tweaks Okamoto’s famous ad slogan to fit his own imaginary commercial: “Genpatsu wa bakuhatsu da!” (Genpatsu is explosion!). In her essays tracing the year of 3.11, Kanai steals the thunder of Akasegawa’s forgotten joke from the 1980s and adapts it for the contemporary context of ChimPom, suggesting thereby that not only had Okamoto sold out his art for commercial profit but that, for her, it was impossible to see ChimPom’s action except through the lens of Okamoto’s television commercial and Akasegawa’s parody of it. Her cynical view of the political power of either Okamoto’s or ChimPom’s art comes through loud and clear.49

|

Akasegawa Genpei, Science and Poetics (Kagaku to Jojō, 1989) |

If Okamoto falls from some transcendental height reserved for true artists in the eyes of both Kanai Mieko and Akasegawa Genpei (albeit in different ways, at different moments), and ChimPom’s art action consequently appears both moving and ridiculously sincere in attempting similar heights, we might well ask what artists like Shiriagari risk by beginning with the everyday and challenging us to do nothing more than wake up to our dysphoric affective reality at ground level. Shiriagari often appears to be as skeptical as Kanai about the “use” of art for political or propagandistic ends; cause and effect are too sloppy for that, and audience reception fickle. Not unlike Okamoto, his works now appear in television commercials, too, leaving him open to similar accusations of crass commercialism, and at the very least, of blurring the lines between advertising and manga. The difference may be more a matter of genre than of art: while Shiriagari’s graffiti expressionism or sloppy line drawings of loopy oyaji characters nakedly satirize themselves as consumable popular culture goods (from which the artist must make a living, we might add), Okamoto’s reputation and modernist fine arts background carve out a more sublime expectation (not tied to any wage labor on Okamoto’s part) necessary for ChimPom’s actions to make their point.

|

Okamoto Tarō’s “Myth of Tomorrow” mural in Shibuya Station, Tokyo |

If not “Hope”…?

We might think that in the Defenders and in “Water and Sky” we find depicted at last some measure of the hope out of 3.11’s disasters that we were denied in Shiriagari’s other manga, perhaps in some Pure Land religious vision. But in his NHK interview with Saito Tamaki, Shiriagari firmly disabuses us of his belief in heaven, however nice it would be if there were one. As with his post-3.11 children born with wings as an adaptation and evolution to a new energy world, in “Water and Sky” too we see what Shiriagari thinks might be the best we can do: strive to reach some sort of “reconciliation” (wakai) between humans and the natural world.50 Most striking, he repeats again and again in interviews how we have to find, then make, our own sacrifices from our daily lives to appease and meet the sacrifices of those who died and who have been displaced in Tohoku. The wordless panels of “Water and Sky,” not to mention the seeming artlessness of his sloppy manga aesthetics, belie the complexity of Shiriagari’s vision overall. His vision of nuclear stuplimity amidst 3.11’s ongoing disaster serves as the muddy and corrupt grounds out of which laughter at the absurd is requisite, well, pretty much every day.

|

|

|

Shiriagari Kotobuki’s final panels from “Water and Sky,” which concludes Manga Ever Since and continues onto the back cover of the volume (Courtesy of Shiriagari Kotobuki and Enterbrain) |

Mary Knighton is an ACLS/SSRC/NEH Fellow at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Her publications include “’Becoming Insect Woman’: Tezuka’s Feminist Species,” MechademiaVol. 8, Special Issue on Tezuka Osamu, “Tezuka’s Manga Life” (2013): 3-24, and “Down the Rabbit Hole: In Pursuit of Shōjo; Alices, From Lewis Carroll to Kanai Mieko.” U.S-Japan Women’s Journal40 (2011): 49-89.

Recommended citation: Mary A. Knighton, “The Sloppy Realities of 3.11 in Shiriagari Kotobuki’s Manga”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 26, No. 1, June 30, 2014.

Notes

I gratefully acknowledge the opportunity to present this essay in its various stages at the following conferences: Elizabethtown College’s “Between Cool and 3:11: Implications for Teaching Japan Today,” in spring 2013, organized by Mahua Bhattacharya; and UC Berkeley’s “Reframing 3.11: Cinema, Literature, and Media After Fukushima,” in April 2014, organized by Dan O’Neill. My thanks go to Suzanne Keen of Washington & Lee University for first recommending Ngai’s book to me. I could not do without the invaluable feedback of Suzuki Ichiro. My thanks go also to Eriko Honda of MindCreators LLC for access to Shiriagari’s work from Magnitude Zero and to Asahi Shimbun for providing a Defenders manga not included in Manga Ever Since. Above all, I express my gratitude to Iwai Yoshinori and Shiriagari Kotobuki himself for generously allowing use of the artwork herein.

1 The translation here is my own, as are any errors. It is excerpted from the concluding 2009 essay to Zonzaina sonzai [Our Sloppy Existence]. Tokyo: Enterbrain, 2010.

2 Shiriagari received the shijuhōshō in May 2014. Most of the story manga in this August 2011 collection first appeared in Enterbrain’s Comic Beam in April 12, 2011. Shiriagari Kotobuki, Ano hi kara no manga 「あの日からのまんが:2011.03.11」[Manga Ever Since: 2011.03.11] Tokyo: Enterbrain, 2011. Shiriagari Kotobuki’s official website can be found here, where visitors can also see the squiggly short animations that he calls “yurumations” (literally, “shaky animations”).

3 Jaqueline Berndt also notes that with Shiriagari’s work, and following its reception for the Defenders strips that appeared as early as March 14, 2011 in the Asahi Shimbun, Comic Beam was the first manga serial to take up 3.11 as subject matter (72).

4 In May 2011, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry officially adopted a policy of “Cool Japan” to promote overseas its contents industry (see here). Kukhee Choo has written persuasively and informatively on industry and governmental policy shifts in this direction since the 2004 Contents Industry Promotion Law: “Nationalizing ‘Cool’: Japan’s Government Global Policy toward the Content Industry,” in Popular Culture and the State in East and Southeast Asia. Eds. Nissim Otmazgin and Eyal Ben-Ari. Guilford Press/Routledge, 2012. 85-105.

5 We might compare this kind of imagination to Susan Sontag’s “imagination of disaster” in her essay of the same name (38-53), collected in the same volume with Freda Freiberg, “Akira and the Postnuclear Sublime,” Hibakusha Cinema: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Nuclear Image in Japanese Film. Ed. Mick Broderick. New York: Kegan Paul International, 1996. pp. 91-102. Near the end of her essay, Sontag writes:

The [fantasy in science fiction] films reflect world-wide anxieties, and they serve to allay them. They inculcate a strange apathy concerning the processes of radiation, contamination, and destruction which I for one find haunting and depressing. The naïve level of the films neatly tempers the sense of otherness, of alienness, with the grossly familiar. In particular, the dialogue of most science fiction films, which is of a monumental but touching banality, makes them wonderfully, unintentionally funny. Lines like ‘Come quickly, there’s a monster in my bathtub,’ ‘We must do something about this,’ ‘Wait, Professor, there’s someone on the telephone,’ ‘But that’s incredible,’ and the old American standby, ‘I hope it works!’ are hilarious in the context of picturesque and deafening holocaust.

Sontag here stresses both the “uplifting” as well as “normalizing” functions of science fiction fantasy but I am most interested in rethinking this “negative imagination” (48) as part and parcel of an affective atmosphere of the everyday, replete with “banality” and absurdity, characteristic of Shiriagari’s work.

6 “Cool Japan” is both exploited and resisted by some artists. I would include in this number Aida Makoto, Takamine Tadasu, and Satoshi Kon. Aida Makoto in his controversial 2012-13 retrospective at the Mori Art Museum (“Monument to Nothing: Sorry to be a Genius”) questioned terrorism and the nature of Japan’s popular culture internationalization; Takamine Tadasu’s 2013 exhibit at Art Tower Mito in Ibaraki parodied Cool Japan as a fiction and a government propaganda tool; and Satoshi Kon’s Paranoia Agent (Mōsō Dairinin, 2004) anime is, in my view, one of the most brilliant explorations of Cool Japan’s rewards and costs within Japan’s contemporary consumer society.

7 See the insightful essay by Jonathan Abel, “Can Cool Japan Save Post-Disaster Japan? On the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Cool Japanology.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 20 (November 2011): 59-72.

8 Mizuki Shigeru’s work has been rediscovered since 3.11, and I thank Matthew Penney for bringing this to my attention. It features illustrations for the real-life story of a Fukushima “nuclear gypsy,” Horie Kunio, first published in Asahi Graph in 1979: Mizuki Shigeru, Fukushima genpatsu no yami ([The dark side of Fukushima] Asahi Shimbunsha, 2011. Manga and anime scholar Jaqueline Berndt refers to the works of Hagio Moto and Yamagishi as “educational” (72), a term more apt, perhaps, for Yamagishi than for Hagio. See Berndt, “The Intercultural Challenge of the ‘Mangaesque’: Reorienting Manga Studies After 3/11,” in Manga’s Cultural Crossroads. Ed. Jaqueline Berndt and Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, New York/London: Routledge, 2013. pp. 65-84. Yamagishi Ryōko’s “Phaeton” (1988) takes up nuclear weapons and nuclear power in the wake of Chernobyl. Her manga opens with the Greek myth of the half-mortal son of Apollo, Phaeton, who wished to prove his divinity by driving his father’s chariot of the Sun, only to be inadequate to the task, compelling Zeus to destroy him before the out-of-control chariot caused even greater destruction. Yamagishi would go on for many pages to relate this myth to present-day hubris in thinking we can control nuclear power. Her manga lays out the science and the evidence in rather didactic detail. After 3.11, she made this manga available for free online: http://vt.usio.co.jp/paetone/index.html. (I thank Yuki Miyamoto for bringing this site to my attention.) Hagio Moto is arguably Japan’s most famous shōjo mangaka, and she adapts Miyazawa Kenji’s beloved children’s story Ginga Tetsudo no Yoru (Night on the Galactic Railway) to the main episodes of Nanohana (Canola Flowers, 2011). This manga repeats a common trope in nuclear arts and literature of plant life that purifies the earth of radioactive contamination and, by extension, of human mistakes. (Sunflowers planted in Fukushima Prefecture in order to take up cesium from the soil come to mind in this context.) Other manga pieces in Hagio’s collection personify Uranium and Plutonium as male and female sadistic or decadent figures, such as Salome.

9 Indeed, it is worth noting that gag humor in particular proclaims an intent to be universally funny, or broadly accessible at every class level; often, however, it ends being either inscrutable or funny only to some, as a matter of particular “taste” (one thinks of The New Yorker cartoons, for instance).

10 Itō Gō discusses this in his essay on Azuma Kiyohiko and Igarashi Mikio in Yuriika/Eureka (37.2 [2005]), pp. 75-87. In his book on 4-koma manga, Shimizu Isao notes (as does Itō above) that the traditional essay structure of kishōtenketsu (起承転結) has shaped the four-frame manga format since the Edo period (Yonkoma manga, Hokusai kara “moe” made [Four Frame Manga, From Hokusai to “Moe”], Tokyo: Iwanami Shinsho, 2009). Comprised of Introduction, Development, Turn, and Conclusion, it is the “turn” or diversion, to which I refer here as a provocative characteristic of 4-koma manga, and one that may not lead to a final punchline at all, even as popular expectations of the genre are for just that. Needless to say, while the genre is called “yonkoma manga” and four panels are both very common and fits the kishōtenketsu model, actual manga length has varied since Edo times among ten to eight or three panels, for instance.

11 A good selection from the field can be found in Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, eds. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2010. This volume is dedicated to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick but does not include her groundbreaking work influenced by psychologist Silvan Tomkins (whose reader she edited), Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

12 Ngai differentiates her project from that of others’ in the fields of ethics, affects, emotions or philosophy:

More specifically, this book turns to ugly feelings to expand and transform the category of ‘aesthetic emotions,’ or feelings unique to our encounters with artworks – a concept whose oldest and best-known example is Aristotle’s discussion of catharsis in Poetics. Yet this particular aesthetic emotion, the arousal and eventual purgation of pity and fear made possible by the genre of tragic drama, actually serves as a useful foil for the studies that follow. For in keeping with the spirit of a book in which minor and generally unprestigious feelings are deliberately favored over grander passions like anger and fear (cornerstones of the philosophical discourse of emotions, from Aristotle to the present), as well as over potentially ennobling or morally beatific states like sympathy, melancholia, and shame (the emotions given the most attention in literary criticism’s recent turn to ethics), the feelings I examine here are explicitly amoral and noncathartic, offering no satisfaction of virtue, however oblique, nor any therapeutic or purifying release. In fact, most of these feelings tend to interfere with the outpouring of other emotions. Moods like irritation and anxiety, for instance, are defined by a flatness or ongoingness entirely opposed ot the ‘suddenness’ on which Aristotle’s aesthetics of fear depends. And unlike rage, which cannot be sustained indefinitely, less dramatic feelings like envy and paranoia have a remarkable capacity for duration. Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings. Harvard University Press, 2005, pp. 6-7.

13 Activism and citizen resistance movements after 3.11 deserve mention here. To start, much useful information can be found right here at Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. See particularly the NGO and Citizen Activism section in the Guide to 3.11 Sources. I also recommend the website of David H. Slater with links to informative essays: “3.11 Politics in Disaster Japan: Fear and Anger, Possibility and Hope.” Fieldsights – Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology Online, July 26, 2011.

14 Citizens have taken dosimeters in their own hands in their efforts to understand better what is happening in the environment around them, both ecologically and politically. Also see Christine Marran’s excellent article, “Contamination: From Minamata to Fukushima.”The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 19 No 1, May 9, 2011.

15 Anne Allison, Precarious Japan. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013. Also see her article “Ordinary Refugees: Social Precarity and Soul in 21st Century Japan. Anthropological Quarterly 85.2 (Spring 2012): 345-370. The epigraph from Alan Wolfe gives this term a longer history in its application to Japan, albeit with a different disciplinary focus.

16 “Stuplimity” derives from “sublime” and “stupefaction.” Particularly apt in the wake of 3.11, “nuclear stuplimity” describes the blockage of clear and effective action and response to, in particular, the reams and streams of data, scientific “facts,” and information presented to average citizens with ceaseless numbing repetition for their immediate processing in our information society. Needless to say, this processing cannot get done, and the stakes of such processing in the first place is never clear despite the anxiety it generates.

17 Shiriagari Kotobuki’s twin old geezers appeared in AX, the successor to the classic gekiga journal GARO, and two short episodes were translated and included in an English-language collection: AX: Alternative Manga, Vol. 1. Ed. Sean Michael Wilson, compiled by Mitsuhiro Asakawa of Seirin-Kogeisha, Marrietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions, 2010, pp. 213-224. Shiriagari’s works have been staged as gallery installations and he has presented his work in various places overseas, particularly Europe (see Zonzaina sonzai [Our Sloppy Existence].

18 Just as Shiriagari was graduating from college, his sempai Yumura Teruhiko (“King Terry”) was drawing covers for GARO and developing the hetauma theory that would exert great influence on Shiriagari and others. Frederick L. Schodt discusses Yumura and his hetauma concept in Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 1996: “At first glance Terry’s cartoons and illustrations appear to be bad art, but on closer inspection, they are also good. Hence, they are heta-uma, or bad-good. Terry believes that everyone starts as a “bad” artist and tries to become good. But simply becoming “good” is not enough. Artists who try too hard to become “good” begin to emphasize technique over soul, and then the life goes out of their drawings; their spirit fails to keep up with their technique. Terry’s philosophy in art, therefore, has been to avoid becoming too good, and to preserve a graffiti-like soul” (141-2).

19 See note 3 above. Shiriagari’s futago no oyaji fall within the AX gekiga genre but also, at times, have much in common with the Defenders or the serialized “Current Events Geezer” (Jiji Oyaji, 「時事おやじ」Tokyo: Asupekuto, 2000) whose oyaji protagonist looks a lot like the father in the “Defenders” strip.

20 Hizakurige, or Shank’s Mare, translated by Thomas Satchell (Tuttle Books, 1960). Shiriagari’s most recent Yurumation commercial is for Black chocolate, and appears also on his professional website.

21 While appropriation of the disaster for commercial or public relations, even tourist, purposes lurks in the details and context of each case, disengaging from the ongoing crisis in Tohoku remains, arguably, the bigger threat as disaster fatigue becomes palpable.

22 Exhibited at the Kyoto International Manga Museum and now published by MindCreators LLC. Details, including Shiriagari’s color version of this panel, can be seen here.

23 Frances Ferguson first frees the sublime from inspiration in Nature in her essay on this aesthetic category’s appropriateness for our times in the nuclear age, not the Age of Enlightenment or Romanticism. Although Freiberg builds on Ferguson’s ideas, this brief essay does not deal with Japan at all.

24 Frances Ferguson stresses that the sublime is an experience of subjectivity, not a quality of objects; nonetheless, as an aesthetic category, the “sublime” is regularly invoked in response to subject matter or viewer/reader responses of awe and fear to art objects. Gothic writers in the 18th-19th centuries such as Ann Radcliffe, not to mention Mary Shelley’s father William Godwin whose writings acknowledged Edmund Burke’s influence, made important distinctions between crass “horror” and the “terror” of the sublime to which their fictions aspired. Ferguson reminds us that Longinus’s ancient essay “On the Sublime” had been rediscovered in the eighteenth century with Peri Hupsous (On Great Writing) (Ferguson, 5). This occurs just in time for the boom in Gothic formula fictions. Apparently the first to separate the sublime from the beautiful, Edmund Burke explores the concept in his 1757 A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Immanuel Kant takes up the subject several times, in Observations on the Feelings of the Beautiful and the Sublime (1764) and Critique of Judgment (1790).

25 See his collection of essays, Hitonami to iu koto [Being just like everyone else] Tokyo: Daiwa Shobō, 2008.

26 Shiriagari, “’Warai’ niwa nishurui aru to omou” [I think there are two types of laughs], in Hitonami to iu koto [Being just like everyone else], 64-68. A special issue of Yuriika/Eureka (37.2 [2005]) on gag manga features Shiriagari’s artwork on the cover. There, in the context of a taidan discussion between Shiriagari and psychologist Kasuga Takehiko, Shiriagari at one point claims, “I want to do the kind of humor that makes people wake up” (“Jibun wa hito o kakusei saseru warai o yaru,” 40). At the end of this volume, the editors include a “map” of gag and contemporary manga artists that places Shiriagari on the extreme end of a spectrum towards the “avant garde,” opposite from “conservative” artists such as the Yomiuri Shimbun’s Ueda Masashi or Gomanism’s Kobayashi Yoshinori (192-3). This map of manga artists creates an x-y axis that places Ishii Hisaichi in the middle between Shiriagari and Ueda. Forming four quadrants, below Ishii is Nishihara Rieko in the category of “Realism/Explosive Laughter” (Bakushō), while above Ishii is the category of “Moe” eroticism, denoted by Azuma Kiyohiko.

27 Shiriagari, “’Warai’ niwa nishurui aru to omou” 67-68.

28 Kitazawa Rakuten (1876-1955) contributed to Tokyo Puck and Jiji Shimpō, a newspaper founded by Fukuzawa Yukichi that had a Jiji Manga page that Rakuten drew for regularly. See the illuminating essay on Rakuten by Ronald Stewart, “Manga as Schism: Kitazawa Rakuten’s Resistance to ‘Old-Fashioned’ Japan,” in Manga’s Cultural Crossroads. Ed. Jaqueline Berndt and Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, New York/London: Routledge, 2013. pp. 27-49.

29 Two of Saito Tamaki’s books have recently appeared in English: Beautiful Fighting Girl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011, translated by J. Keith Vincent, Azuma Hiroki, and Dawn Lawson, and Hikikomori: Adolescence Without End. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013, translated by Jeffrey Angles.

30 Others have expressed similar ideas. The woodblock artist Kazama Sachiko, for instance, uses the salient term kimin (棄民; lit. “throwaway people”) to describe those historical moments when the government abandons its own people in order to preserve the unity of the nation state. Takahashi Tetsuya has described the “sacrificial system” whereby nuclear villages are created in poorer rural areas to be the “invisible,” and expendable, source of larger metropolitan areas’ energy supplyKazama appears in Linda Hoaglund’s documentary, ANPO: Art x War (2011) and uses this term in the context of post-Occupation US-Japan politics. Hoaglund discusses her film in “ANPO: Art x War – In Havoc’s Wake.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 9, Issue 41, No.5, October 10, 2011. See Takahashi Tetsuya, “What March 11 Means to Me: Nuclear Power and the Sacrificial System (私にとっての3.11 原子力発電と犠牲のシステム). The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol.12, Issue 19, No.1, May 12, 2014.

31 This is a term coined by Morimoto Seiichi in the PEN Club essay, Bendo no kiro [A Crossroads at Convenience], which he wrote for the collection Ima koso watashi wa Genpatsu ni hantai shimasu [Especially Now, I Stand Against Nuclear Power]. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2012, pp. 480-483.

32 See Christine Marran’s Poison Woman: Figuring Female Transgression in Modern Japanese Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

33 Matthew Penney has reported on public opinion polls in Japan. His research shows that a majority of citizens’ feel “unease” about nuclear contamination and have a desire to eliminate nuclear power plants altogether since 2011, even though some polls also suggest that people see no other way to provide the amount of power needed to sustain the economy: see Matthew Penney, “Nuclear Power and Shifts in Japanese Public Opinion,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, February 13, 2012. In such 3.11 films as Sono Sion’s Kibō no kuni (Land of Hope, 2012) and Uchida Terunobu’s Odayakana nichijō [The Serene Everyday, Wa Entertainment, 2012], the experts, doctors, power company spokesmen, and politicians are frankly depicted as liars, deliberately obfuscating via their terminology and presentation of science and safety measures the complexity of the contamination. Besides Shiriagari’s Manga Ever Since, Uchida’s film captures particularly well this gap between those trying to cope with the information and risks after a nuclear accident the best way they know how and those disavowing danger. The majority of the people in the film fall into the latter camp, strangely insisting on ignoring the news in order to go on with their daily lives without change. Those who raise alarms are labeled neurotic and are ostracized for unsettling the smooth odayakana surface of the everyday with “dangerous rumor mongering” (fuhyō higai). Representation itself is at issue for artists and documentarians of all stripes in the wake of Japan’s Designated State Secrets Law and the protests against “dangerous rumor mongering” in manga artist Tetsu Kariya’s “Fukushima the Truth” arc in the enormously popular series, Oishinbō [The Gourmet] in May 2014 (this time from the affected disaster regions themselves).

34 I follow Jaqueline Berndt’s lead in not using the more common translation of “self-restraint” here (72).

35 Shiriagari is invariably asked by interviewers (including me) whether or not he was concerned about the jishuku mood or about being indiscreet or improper (fukinshin, 不謹慎), and he invariably denies feeling any such pressure. And yet, he often adds that probably no one cares about his work anyway in such a context as it is “just” gag manga. But Shiriagari clearly touched a nerve in early on – the earliest of any mangaka – taking on 3.11 for representation. That Shiriagari himself slyly dissembles regarding any political or social protest while making an ironic commentary about the lack of seriousness with which manga is taken in Japanese society, anyway – until it is seen as immoral, that is – reveals less Shiriagari’s true experience than a common-sense stance artists at risk of censorship have adopted in both the prewar and postwar periods (see footnote 2 regarding a recent furor over a mangaka’s 3.11 work).