Translation and introduction by Caroline Norma

Translator’s introduction

Morita Seiya wrote this book chapter in May 2013 during a campaign by People Against Pornography and Sexual Violence (PAPS) against an exhibition of works by Aida Makoto at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.2 As described in two earlier articles published by Japan Focus in 2013,3 the Museum attracted criticism for promoting art with misogynistic, paedophilic and anti-disability values. PAPS members met with Museum directors to discuss their concerns, but the meeting achieved no resolution to the issue.4

The campaign did, however, provoke sustained activity among feminist groups concerning recognition of misogynistic cultural products as a form of ‘hate speech’, which is a framework used increasingly by the broad left in Japan since the Zaitokukai hate campaigns directed against Zainichi Koreans and others during the last few years. PAPS published a book on issues arising in the Mori Art Museum campaign in late 2013, and in March 2014 the long-running Osaka-based feminist group Sei bōryoku o yurusanai onna no kai (Women against sexual violence) collaborated with PAPS members to hold a panel workshop on the issue of sexist hate speech at the Dawn Center,5 which was attended by around 50 people (see Diagram 1).6

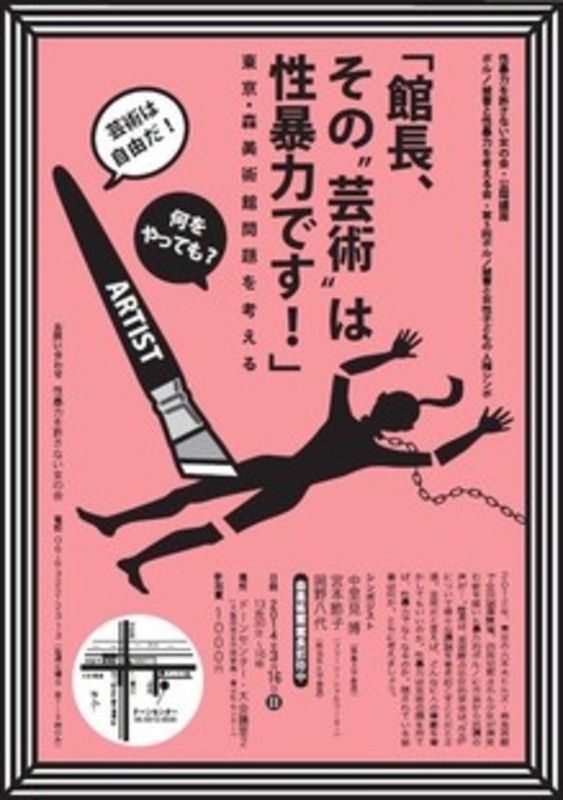

|

Poster advertising the March 2013 panel workshop refers to the recently published feminist book by Muta Kazue titled ‘Buchou, sono ren’ai ha sekuhara desu!’. |

Following this, a third group, the Women’s Action Network (WAN), supported by prominent feminist theorists Muta Kazue and Okano Yayo, announced they would hold a symposium in Niigata city in June 2014 to protest Aida Makoto’s receipt of the Niigata Ango Art award worth one million yen.7

WAN’s promotional material for this symposium is critical of taxpayer money being used to reward a man who has produced art hostile to women, as well as reproducing a novel that boasts of personal involvement in ‘spying on women using public toilets’.8

Morita’s campaigning and writing on the issue of hate speech is a driver of these early efforts toward a sustained feminist critique of misogynistic cultural products among women’s groups in Japan. His work on the issue stems from extensive experience in socialist and radical feminist organising: Morita lectures in political economy at Komazawa University, has written a book that reconciles the different bases of Marxist and radical feminist thought, works with both PAPS and the Anti-pornography and Prostitution Research Group (APP), and is the lead translator of both David Harvey and Catharine MacKinnon’s works in Japanese. CN

Public reaction to the Zaitokukai street marches

In February 2013 in the Shin-Okubo railway station area where there are many Korean-resident (Zainichi) shops, there was an anti-Korean street march held by the Zainichi Tokken o Yurusanai Shimin no Kai group (Citizens against the Special Privileges of the Zainichi, hereafter Zaitokukai) involving hundreds of people. Marchers held aloft discriminatory placards with messages like ‘Kill the good Koreans, kill the bad Koreans, kill them all!’ and ‘Koreans hang yourselves! Poison yourselves! Jump to your deaths!’. Footage and photos of the march disseminated on the internet subsequently sent shockwaves through Japanese society.

|

Aida Makoto is the 2014 winner of the million-yen Ango art award presented by Niigata city. |

Many progressives, including human rights activists and liberals, expressed outrage on Twitter, Facebook and other forms of social media, making the argument that the placard messages were unacceptable even in a society permitting free speech, and incontrovertibly constituted a form of hate speech. Some even suggested laws banning hate speech should be enacted in Japan.

The anti-Korean marches continued on a near-weekly basis, not just in Shin-Okubo but also in Osaka and other areas. The placards and chants became more racist and threat-invoking in their message. There was even one participant in an Osaka march who actually called for genocide against Koreans.

On 30 March, twelve lawyers, including the former head of the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, Utsunomiya Kenji, published a signed letter protesting the ‘anti-foreigner exclusionary marches of the Shinjuku and Shin-Okubo areas’, which includes the following criticism of the absolutist free speech position:

We are mindful of the view that we should never appeal to public authority to intervene in matters of public speech, even in the case of the anti-foreign, exclusionary speech that we have seen recently. However, we believe that the recent words and actions of people marching in the streets goes beyond what any bystander should tolerate.

The anger and abhorrence expressed by Japanese progressives, including by human rights activists and liberals, at the Zaitokukai marches is entirely warranted, given the history of violence and discrimination that the marches build on against Zainichi Koreans, a group long targeted for discrimination and hate-mongering. I, too, feel exactly the same anger and abhorrence. And I fully agree with the lawyers that these kinds of hate protests should not be defended under the rubric of ‘free speech’.

Public reaction to the sexually violent Mori Art Museum exhibition

|

Railway station advertisement for the Aida Makoto exhibition at the Mori Art Museum. |

How did these same people respond, however, to the letter of protest issued by my organisation just days before the release of their own public statement, which protested the Aida Makoto exhibition at Japan’s top-ranking contemporary art institution, the Mori Art Museum, displaying works of sexual violence? What was the reaction of these people who had expressed anger and disgust at the Zaitokukai marches? Taking Twitter feeds as a rough gauge of their reaction, I observed responses ranging from indifference to hostility, as well as oppositional arguments about the need for ‘free speech’. It goes without saying that Utsunomiya and his colleagues released no statement of their own criticizing the exhibition, and assumed the stance of mere ‘bystanders’. (It should be noted that information of my organisation’s campaign against the exhibition was distributed far and wide, and is likely to have reached their attention.)

The magazine Shūkan Kinyōbi ran a feature article on our campaign, but, far from supporting it, their coverage took a ‘balanced’ stance through offering comment on ‘both sides of the debate’. The article also included an ‘editor’s footnote’ from a male editor who was previously the editor-in-chief of the magazine offering a sympathetic view of the exhibition on the grounds that he ‘couldn’t help having been born a man’. He hedged this footnote with the defence that he nonetheless thought the ‘dog series’ was disgusting. In actual fact, the only reason the article was carried in the magazine was because a female reporter on the editing team expressed anger on hearing about the exhibition.

Do we imagine that Shūkan Kinyōbi would run a similarly ‘balanced’ article on the Zaitokukai marches? Would it really be the case that an editor’s footnote expressing sympathy for the views of Zaitokukai would be printed on the grounds that the author ‘couldn’t help having been born a Japanese person’? Surely this would be unlikely. How are we to explain the different reaction—if not the outright contrasting reaction—seen in these two examples?

The one-hour protest of hundreds of people under banners with slogans like ‘Kill the good Koreans, kill the bad Koreans, kill them all!’ was an intolerable act of hate speech that should not be defended in the name of ‘free speech’. By the same token, can we say that the display of a number of extremely large panels depicting a naked girl with four severed limbs wearing a dog collar smiling faintly in an exhibition held over many months and viewed by tens of thousands of people that was organised and promoted with a financial budget likely to have been very large, and held on the top floor of a building in the most expensive location of Roppongi Hills, is merely a form of expression? A form of expression that must be protected in the name of free speech?

|

Police stand between Zaitokukai and anti-racist marchers in Tokyo, 2013 |

How are the two examples at all different?

What fundamental difference separates the two examples described? The objection is raised that Aida Makoto’s paintings are merely paintings, and no real-life girl had her limbs amputated in order to make them. But in the case of the Zaitokukai placards, too, the words were merely words, and no real-life Korean was actually murdered in order to prepare them. If we justify the Mori Art Museum exhibition on the basis that no live girl was used in its production, then surely we can justify the conduct of the Zaitokukai marches on the same basis. Alternatively, there is the objection that Aida Makoto is an internationally renowned artist, and produces works of art.

By this logic, we would have to say that the placards produced by the Zaitokukai marchers are not art, and are merely words scrawled in anger. In that case, is hate speech conveyed artistically to be tolerated? If an artist of the stature of Aida Makoto were to compose placards for Zaitokukai marches calling for genocide against Koreans, would we accept them? On the contrary, might we not think the scenario more perverse and harmful in the case of an internationally renowned artist holding an exhibition of sexually discriminative hate in the Mori Art Museum, one of Japan’s most internationally renowned institutions?

So, what fundamentally differentiates the two examples? Why did one example become the object of contempt and criticism while the other attracted indifference, if not support? The difference is as follows. One case involved the targeting of an ethnic minority that includes men, but the other case involved only women, and in fact targeted mostly underage girls. One case had no association with sex, and the other was highly sexualised. One case was wholly political, and the other was shrouded in the cloak of entertainment, art and culture. In sum, the two examples diverge fundamentally along the political lines of gender and sexuality. The ‘politics of pornography’ (as we’ll call it) comes into play when traditional politics are subject to the forces of gender and sexuality. These traditional politics become unrecognisable.

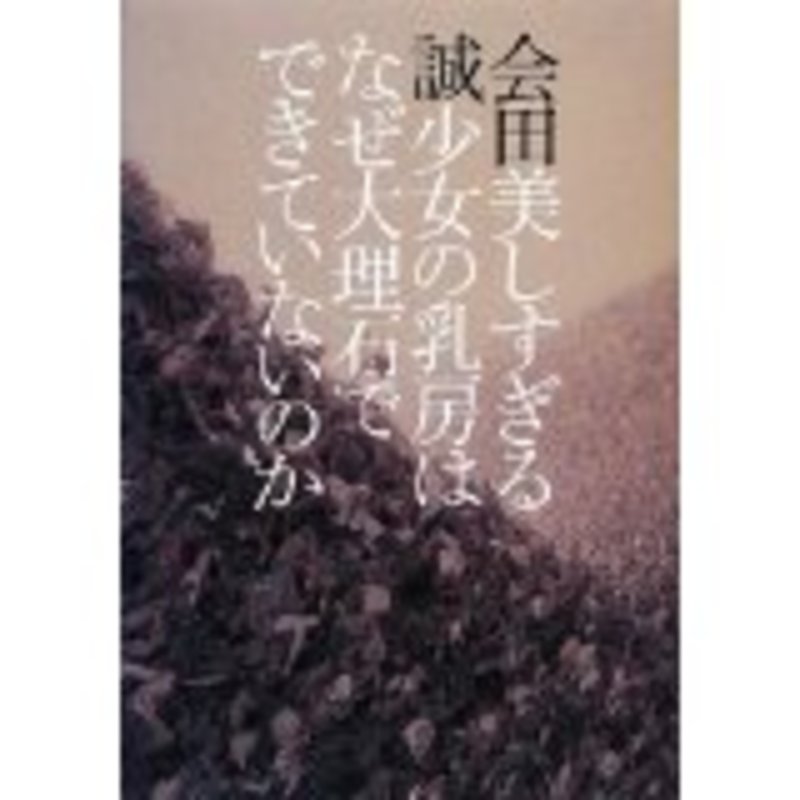

|

Aida Makoto’s 2012 novel ‘Why are girls’ exquisitely beautiful breasts not made of marble?’ |

In contexts where women are exclusively targeted victims, and where the environment is sexualised in some way, and where the context is made out to be one of entertainment, art or culture, most of Japan’s progressive left, including human rights activists and liberals, do not identify any human rights violation, or at least do not see anything serious enough to warrant raising voices in protest.

Feminist legal theorist Catharine MacKinnon on the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights posed the question, ‘Are women human?’ Are women included in the definition of ‘human’ that is set down in the Declaration? If women truly are considered to be human beings, then why are women still being trafficked internationally as sex slaves in an era when the African slave trade has long been abolished? Why are rape victims blamed for their victimisation and treated like criminals? Why is acid thrown in women’s faces and their noses cut off?9

I would like to take the kernel of MacKinnon’s question and extend it to further ask: ‘Why is a painting that depicts a young girl enjoying the fact of being naked with amputated limbs and wearing a collar exhibited openly for months in the prestigious Mori Art Museum, and acclaimed by outlets like NHK and the Bijitsu Techō magazine? Why is pornography showing human rights violations like rape, enslavement and brutalization produced at a rate of thousands and tens of thousands of films a year, sold and leased, and then called ‘freedom of expression’?

The message underlying Hashimoto’s statements

The extent to which women in Japan are not treated as human beings is shown clearly in statements made by Osaka mayor Hashimoto Toru on 13 May as a representative of the Japan Restoration Party. In a newspaper interview, Hashimoto expressed the view that, as a respite for soldiers having to dodge bullets in battle, ‘the comfort women system was necessary’. Before this, Hashimoto had repeatedly insisted there was no evidence the Japanese military had forcibly interned women in military comfort stations, but his May comments were an escalation of this stance. They endorsed the very necessity of the system. After making the statements, Hashimoto offered various excuses in his own defence, but he stopped short of revising his view that the stations were necessary, and offered no withdrawal of his statements, nor any apology. Another Japan Restoration Party member Ishihara Shintarō endorsed his comments by adding the view that war and prostitution inevitably go together, and many male intellectuals and notables expressed views of support via blogs and on Twitter.

Unsurprisingly in the Hashimoto example, which was clearly an instance of public expression carried out in a wholly political context, many people raised their voices in protest, and even the Japan Restoration Party was forced to respond. Japan Communist Party secretary general Ichida Tadayoshi held a press conference on the same day to strongly condemn the statements as ‘injuring human dignity’, and to declare Hashimoto unfit for the mayoralty. Social Democratic Party head Fukushima Mizuho told reporters that his statements infringed the human rights of all women, and must not be tolerated.10 Was it not a sufficiently political act deserving of comment by public representatives for a nationally representative, public museum to host and endorse an exhibition over many months of sexually violent works to be seen by tens of thousands of people?

A matter of mere words?

The abovementioned protest letter published by Utsunomiya and his lawyer colleagues includes the following statement: ‘If we allow this situation to continue, we run the risk of escalation towards real attacks against the life and person of foreigners, as the lessons of European history since the 1980s teach us’.

This statement is exactly right. Words are not mere words, the lawyers are correct in warning of the ease with which words can transition into actual acts when they are targeted at an oppressed group. However, we needn’t reach as far back as ‘European history’ to see evidence of this process occurring in the case of ‘attacks against the life and person’ of women. We might say this has already long been occurring on Japanese soil. We might cite the example of the man who attempted, but failed, to enslave a woman in his neighbourhood after having watched pornographic films featuring this scenario, or we might cite the thousands or tens of thousands of rapes, sexual assaults and sexual harassment incidents that are perpetrated against women each year in Japan, in addition to the violence from husbands and boyfriends, and the occasional murder by stalkers.

We take this violence as evidence of sexually violent expression already having transitioned into actual harmful acts against women and girls as occurring in Japan. But when we express this view, it is met with derision, and we are asked to produce hard evidence of this occurrence. (In the same way that advocates for ‘comfort women’ survivors are asked to produce hard evidence of the history of military sexual slavery.) And when we say that a picture of a naked girl with amputated limbs smiling at being treated like a dog infringes the human rights of all women and injures the dignity of all human beings, we are told it’s just a painting. But the Shin-Okubo placards are just words, aren’t they? Why is the causal outcome of the painting not seen in equally clear and obvious terms as the causal outcome of the placards?

When will the human rights of women become real human rights?

The abovementioned protest letter published by Utsunomiya and his lawyer colleagues ends with the following sentence: ‘On this basis, we resolve to act urgently to address the impending danger of the situation, and we call on the media and all people concerned about the future of human rights, freedom and democracy in Japan to join with us’.

I support this call wholeheartedly. Hate speech and hate protests violate not only the human rights of the groups immediately targeted, they also threaten the human rights of everyone.

When will we see the day women attract public statements like that of the lawyers, including the ex-head of the national lawyers’ association, declaring an ‘urgent call to action’ in relation to the daily instances of sexual hate speech they endure. When will we see the heads of the JCP and the SDP hold press conferences to condemn the sexually violent pornography currently being produced en masse as ‘violating the human rights of all women’? These are the types of questions posed by MacKinnon when she challenges us to consider, ‘Are women human?’ and ‘When will women be human? When?’

Caroline Norma lectures in the School of Global, Urban and Social Studies at RMIT University and is an editorial board member of Women’s Studies International Forum. Her book, Japanese comfort women and sexual slavery during the China and Pacific wars is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in 2015.

Recommended Citation: Morita Seiya, “On Racial Discrimination and Gender Discrimination in Japan: the Gap Separating the Zaitokukai March and the Aida Makoto exhibition”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 22, No. 3, June 2, 2014.

Notes

1 Morita Seiya, ‘Zaitokukai demo to Aida Makoto ten to no aida,’ pp. 64-70 in Poruno higai to sei bōryoku o kangaeru kai (eds), Mori Bijutsukan mondai to sei bōryoku hyōgen (Tokyo: Fumashobō, 2013).

2 The translator commends to readers the PAPS twitter feed for expert analysis of gender-related issues arising in Japan in real time here.

9 The translator refers readers to MacKinnon’s text found here.

10 Fukushima no longer leads the party.